Abstract

Purpose

Puberty, obesity, endocrine and chronic systemic diseases are known to be associated with slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). The mechanical insufficiency of the physis in SCFE is thought to be the result of an abnormal weakening of the physis. However, the mechanism at the cellular level has not been unravelled up to now.

Methods

To understand the pathophysiology of endocrine and metabolic factors acting on the physis, we performed a systematic review focussing on published studies reporting on hormonal, morphological and cellular abnormalities of the physis in children with SCFE. In addition, we looked for studies of the effects of endocrinopathies on the human physis which can lead to cause SCFE and focussed in detail on hormonal signalling, hormone receptor expression and extracellular matrix (ECM) composition of the physis. We searched in the PubMed, EMBASE.com and The Cochrane Library (via Wiley) databases from inception to 11th September 2012. The search generated a total of 689 references: 382 in PubMed, 232 in EMBASE.com and 75 in The Cochrane Library. After removing duplicate papers, 525 papers remained. Of these, 119 were selected based on titles and abstracts. After excluding 63 papers not related to the human physis, 56 papers were included in this review.

Results

Activation of the gonadal axis and the subsequent augmentation of the activity of the growth hormone–insulin-like growth factor 1 (GH-IGF-1) axis are important for the pubertal growth spurt, as well as for cessation of the physis at the end of puberty. The effects of leptin, thyroid hormone and corticosteroids on linear growth and on the physis are also discussed. Children with chronic diseases suffer from inflammation, acidosis and malnutrition. These consequences of chronic diseases affect the GH-IGF-1 axis, thereby, increasing the risk of the development of SCFE. The risk of SCFE and avascular necrosis in children with chronic renal insufficiency, growth hormone treatment and renal osteodystrophy remains equivocal.

Conclusions

SCFE is most likely the result of a multi-factorial event during adolescence when height and weight increase dramatically and the delicate balance between the various hormonal equilibria can be disturbed. Up to now, there are no screening or diagnostic tests available to predict patients at risk.

Keywords: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis; Systematic review; Endocrine, metabolic and chronic diseases

Introduction

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is a disorder of the proximal femur in adolescents. SCFE is defined as the displacement of the femoral head relative to the femoral neck and shaft in the physis. The proximal femoral neck and shaft move anteriorly and rotate externally relative to the femoral head, leaving the femoral head stabilised in the acetabulum. SCFE is most often diagnosed in obese adolescents and in children with endocrinopathies or chronic systemic diseases. The pathogenesis of SCFE has not been unravelled fully so far. A precise insight into the pathogenesis of SCFE is important for understanding the disease and possible development of rational therapy.

It is thought that SCFE is the result of mechanical insufficiency of the proximal femoral physis. The slip is a result of either an abnormally high load across a normal physis or a physiological load across an abnormally weak physis, or a combination of these two. Mechanical factors for an abnormally high load include obesity, femoral retroversion and increased physeal obliquity [1]. The majority of adolescents with SCFE might not have hormonal metabolic or chronic diseases, but they are obese and fast growing. However, it seems unlikely that mechanical overload of the proximal femur epiphysis, by, for example, high body weight only, can lead to SCFE. Many children in their growing age are exposed to high mechanical loads of their hip joints during normal activities and sports activities for example.

Conditions that weaken the physis include endocrine or systemic diseases, for example, hypothyroidism, growth hormone suppletion and hypogonadal abnormalities [1]. The underlying mechanisms that are involved in the development of abnormal weakening of the physis may originate from the cellular level and include dysregulation of chondrocytes in the hypertrophic layer of the physis, as well as disturbances in the extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover. In addition, these phenomena may result from improper or dysregulated signalling through the several pathways involved, for instance, hormonal receptors or its second messengers.

However, how metabolic and endocrine factors can cause a weak physis is unclear. In order to obtain insight into the available data on the role of metabolic and endocrine factors in physis weakening and the pathogenesis of SCFE, we performed a systematic review with emphasis on the pathogenetic mechanisms. In this review, we will only discuss the association of endocrine, metabolic and chronic diseases and SCFE. The role of anatomical factors related to SCFE are not the subject of this review.

Methods

Literature search

We performed systematic searches in the databases PubMed, EMBASE.com and The Cochrane Library (via Wiley) from inception to 11th September 2012. Search terms included controlled terms from MeSH in PubMed and EMtree in EMBASE.com, as well as free-text terms. We used free-text terms only in The Cochrane Library. Search terms expressing ‘epiphysiolysis’ were used, in combination with search terms comprising ‘endocrine diseases’ or ‘biopsy’. The search was then combined with terms for ‘extracellular matrix proteins, hormones’ and filtered for ‘children’ (Table 1). The references of the identified articles were searched for relevant publications.

Table 1.

Search strategy in PubMed up to 11th September 2012 (to be read from the bottom up)

| Set | Search terms | No. of results |

|---|---|---|

| #6 | #1 AND (#2 OR #3) AND #4 AND #5 NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]) | 382 |

| #5 | child*[tw] OR schoolchild*[tw] OR adolescen*[tw] OR pediatri*[tw] OR paediatr*[tw] OR boy[tw] OR boys[tw] OR boyhood[tw] OR girl[tw] OR girls[tw] OR girlhood[tw] OR youth[tw] OR youths[tw] OR teen[tw] OR teens[tw] OR teenager*[tw] OR puberty[tw] | 2,601,373 |

| #4 | “Extracellular Matrix Proteins”[Mesh] OR “Collagen Type II”[Mesh] OR “Collagen Type IX”[Mesh] OR “Collagen Type X”[Mesh] OR collagen[tiab] OR “Aggrecans”[Mesh] OR aggrecan[tiab] OR “Aggrecans”[tiab] OR “Proteoglycan Core Proteins”[tiab] OR “SOX9 Transcription Factor”[Mesh] OR “SOX9”[tiab] OR “SOX 9”[tiab] OR “Matrix Metalloproteinase 9”[Mesh] OR “Matrix Metalloproteinase 9”[tiab] OR MMP9[tiab] OR “92 kDa Gelatinase”[tiab] OR “92 kDa Type IV”[tiab] OR “Matrix Metalloproteinase 13”[Mesh] OR “metalloproteinase 13”[tiab] OR “Metalloproteinase-13”[tiab] OR “matrixmetalloproteinase 13”[tiab] OR “matrix metalloproteinase thirteen”[tiab] OR “matrixmetalloproteinase thirteen”[tiab] OR mmp13[tiab] OR “mmp 13”[tiab] OR “MMP-13”[tiab] OR “Collagenase-3”[tiab] OR “Collagenase 3”[tiab] OR “Insulin-Like Growth Factor I”[Mesh] OR “Insulin-Like Growth Factor I”[tiab] OR “IGF I”[tiab] OR “IGF-I”[tiab] OR “Bone Morphogenetic Proteins”[Mesh] OR “Bone Morphogenetic Proteins”[tiab] OR “Bone Morphogenetic Protein”[tiab] OR BMP*[tiab] OR “physeal architecture”[tiab] OR “Estrogens”[Mesh] OR Estrogen*[tiab] OR oestrogen*[tiab] OR “Testosterone”[Mesh] OR Testosteron*[tiab] OR “Leptin”[Mesh] OR Leptin[tiab] OR “Ghrelin”[Mesh] OR Ghrelin[tiab] OR “Triiodothyronine”[Mesh] OR “T3 TRα1”[tiab] OR β1[tiab] OR “beta-1”[tiab] OR “T3 Thyroid Hormone”[tiab] OR “Thyroxine”[Mesh] OR “T4 Thyroid Hormone”[tiab] OR IGFI[tiab] OR IGF1[tiab] OR “IGF 1”[tiab] OR “Receptor, IGF Type 1”[Mesh] OR IGF1R[tiab] OR “Insulin-Like Growth Factor II”[Mesh] OR “Insulin-Like Growth Factor II”[tiab] OR “IGF II”[tiab] OR “IGF-II”[tiab] OR IGFII[tiab] OR IGF2[tiab] OR “IGF 2”[tiab] OR “Receptor, IGF Type 2”[Mesh] OR IGF2R[tiab] OR “Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Proteins”[Mesh] OR IGFBP[tiab] OR sox[tiab] OR immunoglobin[tiab] OR “C3 protein, human”[Supplementary Concept] OR C3[tiab] | 603,352 |

| #3 | “Biopsy”[Mesh] OR “Microscopy, Electron”[Mesh] OR “Microdissection”[Mesh] OR ((microdissection[tiab] OR micro-dissection[tiab] OR Biopsy[tiab] OR biopsies[tiab] OR “electron microscopy”[tiab] OR “TEM”[tiab]) NOT medline[sb]) | 537,806 |

| #2 | “Growth Disorders”[Mesh] OR “growth disorder”[tiab] OR “growth disorders”[tiab] OR “Hypothyroidism”[Mesh] OR “Hypothyroidism”[tiab] OR “Hypothyroidisms”[tiab] OR “Hypoparathyroidism”[Mesh] OR “Hypoparathyroidism”[tiab] OR “Hypoparathyroidisms”[tiab OR “Hyperparathyroidism”[Mesh] OR “Hyperparathyroidism”[tiab] OR “Hyperparathyroidisms”[tiab] OR “Renal Osteodystrophy”[Mesh] OR “Renal Osteodystrophy”[tiab] OR “Renal Osteodystrophies”[tiab] OR “Renal Insufficiency”[Mesh] OR “Renal Insufficiency”[tiab] OR “Renal Insufficiencies”[tiab] OR “Renal failure”[tiab] OR “Renal failures”[tiab] OR “kidney failure”[tiab] OR “kidney failures”[tiab] OR “Growth Hormone”[Mesh] OR “Growth Hormone”[tiab] OR GH[tiab] OR somatotropin*[tiab] | 295,106 |

| #1 | “Epiphyses, Slipped”[Mesh] OR epiphysiolysis[tiab] OR epiphysiolyses[tiab] OR SCFE[tiab] OR “Growth Plate”[Mesh] OR “Epiphyses”[Mesh] OR epiphyses[tiab] OR epiphysis[tiab] OR “Growth Plate”[tiab] OR “Epiphyseal plate”[tiab] OR “Epiphyseal plates”[tiab] OR “Epiphyseal cartilage”[tiab] OR “Epiphyseal cartilages”[tiab] OR “Extracellular Matrix”[Mesh] OR “Extracellular Matrix”[tiab] OR “Extra cellular Matrix”[tiab] OR “ECM”[tiab] | 87,886 |

Selection phase

Two reviewers (M.M.W. and E.P.J.) independently screened all potentially relevant titles and abstracts for eligibility. If necessary, the full-text article was checked for the eligibility criteria. Differences in judgment were resolved through a consensus procedure. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: studies discussing the histology of biopsies in SCFE physis, evaluation of hormonal factors influencing the human physis, SCFE and the ECM in the human physis. Exclusion criteria were articles not related to the human physis, animal-related research on the physis and drugs-related studies. The full text of articles was obtained for further review.

Results

The literature search generated a total of 689 references: 382 in PubMed, 232 in EMBASE.com and 75 in The Cochrane Library. Another eight additional studies identified through other sources were included.

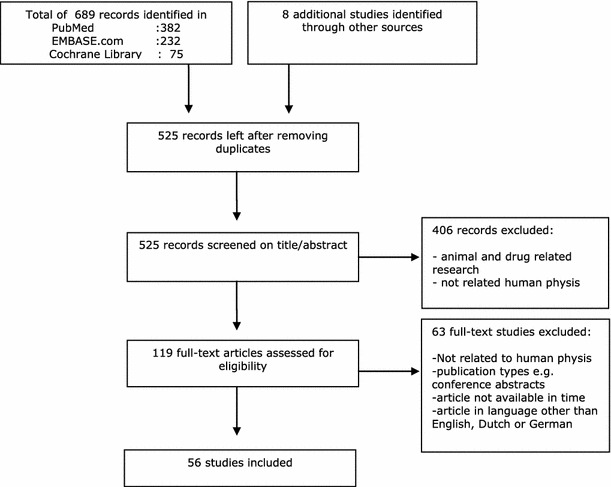

After removing duplicates of references that were selected from more than one database, 525 papers remained. Of these, 119 papers were selected based on titles and abstracts. Sixty-three papers were excluded after judgment if not related to human biology, publication types, e.g. conference abstracts, article not available in time or article written in a language other than English, Dutch or German. Fifty-six papers were included in this review. The flow chart of the search and selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search and selection procedure of studies

For this review, we present the results under five headings:

The physis in SCFE: reviews studies specifically dealing with SCFE

- Endocrinology of growth and puberty: reviews the major endocrine effects on the physis throughout puberty

- Obesity and SCFE

- GH-IGF-1 axis and SCFE

- Sex steroids in puberty and SCFE

- Leptin and SCFE

- Thyroid hormones and SCFE

- Glucocorticoids and SCFE

Vitamin D: reviews the effects of vitamin D at the growth plate

Chronic disease: reviews the effects of chronic disorders on the physis

Diagnostic endocrine measurements in SCFE: reviews the studies that specifically investigated SCFE

The physis in SCFE

Histological changes in SCFE

Histological studies of tissue obtained from biopsies during surgery for SCFE show some characteristic features of the physis.

Changes in the longitudinal orientation of the cartilage cells of the physis, which are normally parallel to the axis of the bone, are seen in tissues taken from biopsies in SCFE. In SCFE, pathologic tangential forces damage the hypertrophic cartilage. As a result of the longitudinal orientation of these fibres, this zone is the least protected from these shearing forces [2]. However, it is not always clear as to whether the observed changes in cell orientation are found before or after the SCFE occurred. Obviously, the actual time of biopsies was taken after the slip occurred.

The resting zones of the epiphysis appeared to be relatively normal in SCFE [3–6], although some tissue samples showed clusters of numerous chondrocytes cells [5].

The proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the epiphysis in SCFE were widened compared with normal physis, and showed irregular columnar organisation with gradual loss of longitudinal septa and diminished number of chondrocytes in each column [3–7]. Interestingly, Adamczyk et al. showed that apoptosis was increased throughout the physis in SCFE, in contrast with controls, where apoptosis was found only in the hypertrophic zone [8]. The chondrocytes showed intracellular abnormalities [5, 7, 9]. An increase in the nuclear and cytoplasmic density was seen in the proliferative and hypertrophic chondrocytes with SCFE and an increase in cytoplasmic glycogen [7, 9]. Other investigators, however, could not confirm these findings [3, 6].

The ECM of the physis had abnormal longitudinal septa with deficiency in collagen [3, 5, 7, 9]. The amount of proteoglycans in the ECM was moderately decreased in the matrix of the physis in SCFE compared to normal [3, 7, 9]. Also, abnormal proteoglycans were found [5]. Matrix vesicles, secreted by hypertrophic chondrocytes, were more abundant than in the controls [5, 7, 9]. Matrix vesicles contain calcium phosphates, hydroxyapatite and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). The contents of these vesicles changes the structure of the ECM and begins the process of calcification of the matrix [10]. Lacunar spaces in the hypertrophic zones were seen, with reactive changes showing callus formation [3, 4, 6].

Scharschmidt et al. performed laser capture microdissection followed by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of mRNA on the physis tissue of SCFE obtained by biopsies. They observed down-regulation of both type 2 collagen and aggrecan in physes of patients with SCFE [11].

In conclusion, the physis in SCFE shows many histological differences compared to the normal physis in columnar organisation, on the cellular level and in the ECM. The fundamental problem is that the role of the described changes is unknown. It is unclear as to whether they are causal or adaptive. Some of these changes can occur also in endocrine or metabolic abnormalities, as will be discussed further in this review (see Figs. 2 and 3).

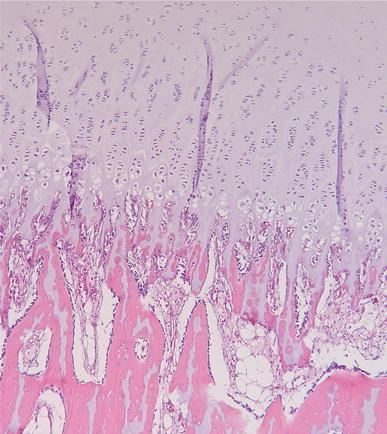

Fig. 2.

Normal physis of a 2-year-old boy after amputation for tibial aplasia. At the top is the regularly organised cartilage of the growth plate, with the different zones leading at the bottom to the ossification zone

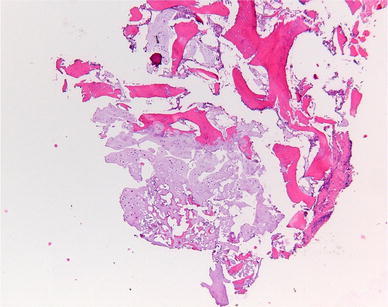

Fig. 3.

Abnormal physis taken of a 10-year-old boy with slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) on both sides. At the top-right of the image, the ossification is visible, and at the bottom, the disorganised cartilage from the growth plate is visible. The normal regular organisation is lacking

Endocrinology of growth and puberty

During the pubertal growth spurt, endocrine changes are enormous. Disturbances of the endocrine mechanisms may lead to weakening of the physis of the proximal femur. Before puberty, the major endocrine factors involved in linear growth and skeletal development are the growth hormone–insulin-like growth factor 1 (GH-IGF-1) axis and triiodothyronine (T3).

With the onset of puberty, the gonadal axis is reactivated after years of quiescence. Increasing levels of sex hormones are responsible for an augmentation of the GH-IGF-1 axis activity.

Sex hormones, growth hormone, IGF-1 as well as other endocrine, paracrine and autocrine factors exert a direct and indirect effect on the physis [12–14].

Since obesity and pubertal growth spurt seem to be the main risk factors for SCFE, we will start by explaining the influence of the (1) the GH-IGF-1 axis, (2) sex steroids and (3) leptin. Their influence on the physis is complex.

Subsequently, we will discuss thyroid hormone, glucocorticoids, vitamin D, chronic disease and diagnostic endocrine measurements in SCFE.

Obesity and SCFE

GH-IGF-1 axis and SCFE

Growth hormone (GH) is a peptide hormone that stimulates growth, cell reproduction and regeneration in humans and other animals. GH is normally produced in an abundant quantity by the pituitary somatotroph cells. It is secreted in a pulsatile manner stimulated by hypothalamic GH-releasing hormone (GHrH), inhibited by somatostatin (growth hormone-inhibiting hormone) and under negative feedback of the peripheral effectors GH, IGF-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP) [15–18]. During pubertal development, the basal secretion and pulse amplitude of GH increases two-fold to three-fold as a result of increasing levels of sex hormones [12].

According to the dual effector theory, GH can act directly as well as indirectly, via IGF-1, on the physis. Directly, GH acts on the resting zone and is responsible for local IGF-1 production, which stimulates clonal expansion of proliferative chondrocytes in an autocrine/paracrine manner. Indirectly, GH stimulates IGF-1 synthesis in the liver, which, in turn, activates chondrocyte proliferation in the physis [12, 18–23].

IGF-1 is a peptide hormone and a major metabolic regulator in the body. Most circulating IGF-1 is synthesised by the liver. It has anabolic effects on muscle and bone and catabolic effects on fat [16]. Recent studies indicate that locally acting IGF-1 is a key determinant of endochondral ossification and that GH, glucocorticoids (GC) and T3 regulate the expression of IGF-1 and its receptor in the physis directly [14, 22]. Insulin like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) gives thanks to its name from the similarity of insulin. It also explains the ability of IGF-1 to bind to insulin receptors and insulin’s ability to bind to the IGF-1 receptor [17, 18].

Hepatic IGF-1 is almost entirely bound to IGFBPs. There is a family of six, of which IGFBP3 is the most important. Acid labile subunit (ALS), also synthesised by the liver, acts as a stabiliser for the ternary complex with IGF-1 and IGFBP3. Only 1 % of plasma IGF-1 occurs in free bioactive form [13, 15, 17, 24]. Circulatory IGF is detected by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to inhibit GH secretion, completing the feedback loop [16].

In the largest US registry, the National Cooperative Growth Study (NCGS), the use of recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) treatment in children with short stature did not appear to measurably increase the risk for SCFE [25]. There are hardly any data to determine the role of abnormalities in this axis in SCFE.

In conclusion, the GH-IGF-1 axis is a major growth regulator throughout childhood and adolescence, has direct and indirect influence on the physis and is regulated by different hormones and growth factors itself.

Sex steroids in puberty and SCFE

The androgen testosterone and the oestrogen estradiol are the main steroid hormones that are produced by the testes and ovaries, respectively. Androgens can be converted to oestrogens in other tissues such as liver, fat or muscle, which is especially important in overweight boys and men. In addition to the gonads, the adrenal glands produce androgens that have a low androgen activity compared to testosterone.

Androgens and oestrogens are responsible for the pubertal growth spurt. The subsequent closure of physis is dependent on oestrogens in females as well as in males [14, 20]. The onset of the adolescent growth spurt is 2 years earlier in girls than in boys. A longer period of prepubertal growth as well as a higher growth spurt account for the greater adult height of males compared to females [17]. Not surprisingly, SCFE also occurs in an earlier phase in girls, with an average age of 12.0 years, than in boys, with an average age of 13.5 years [1].

Androgens and oestrogens have a direct growth-stimulating effect on the physis, as well as an indirect effect through the enhancement of GH secretion from the pituitary gland mediated by estrogen receptor (ER-α). Thus, androgens can only influence the GH-IGF-1 axis after aromatisation into oestrogens [12, 13, 18, 26, 27]. Boys have aromatase activity in numerous tissues, including adipose tissue and muscle. Boys with idiopathic gynaecomastia are generally characterised by relative obesity, resulting in increased conversion of androgens to oestrogens [20]. Boys with the rare condition of aromatase excess syndrome have increased conversion of testosterone to estradiol and, typically, develop gynaecomastia as well as increased longitudinal growth. In contrast, delayed skeletal maturation and low bone mineral density are observed in patients with aromatase deficiency and oestrogen receptor resistance [28], underlining the importance of oestrogen action in skeletal maturation, epiphyseal closure and bone mass accrual.

Oestrogens are, thus, important in the regulation of linear growth of both sexes. In addition, oestrogens have a direct and an indirect role on the physis. Directly, oestrogens stimulate the local production of IGF-1 and other growth factors. Indirectly, low concentrations of oestrogens stimulate GH secretion, thereby, increasing circulating IGF-1 levels that, in turn, stimulate chondrocyte growth in the proliferation zone and may also potentiate clonal expansion. Oestrogens also seem to have a biphasic effect on the physis. Low concentrations of oestrogen augment skeletal growth, whereas continued high levels of oestrogens lead to epiphyseal fusion. High doses of oestrogen inhibit clonal expansion and cell proliferation in the hypertrophic zone. Furthermore, high concentrations of oestrogen induce apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes and stimulate osteoblast invasion in the physis [12, 18, 20, 26].

The current understanding of how oestrogens affect growth may suggest separate roles for the different estrogen receptors (ERs). Two ERs exist: ER-α and ER-β. Juul et al. [20] found that ER-α is localised in all zones of the physis and ER-β is expressed in hypertrophic chondrocytes exclusively. Nilsson et al. [29] demonstrated that both receptors are present in all zones of the physis, but in a greater frequency in the resting and proliferative zones. The androgen receptor (AR) was found to be more abundant in the resting and hypertrophic zones.

Also, a new membrane-bound ER G-protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) was discovered. The highest level of this receptor was found in hypertrophic chondrocytes. The receptor revealed a weak immunostaining in the resting zone. During puberty, a decline was found in the expression of this receptor in both boys and girls. This new receptor could play an important role for the cessation of growth in puberty [30].

Testosterone has, not only after aromatisation, an effect on growth but also directly on the physis by the stimulation of proliferation and differentiation in chondrocytes. This direct effect on the human physis is not necessary for the pubertal growth acceleration or for the cessation of growth. ARs have been found in hypertrophic chondrocytes in the human physis and cartilage. Some organs are capable of synthesising sex steroids from sulphated precursors which are present in high amounts in the circulation. The term ‘intracrinology’ was introduced, suggesting that sex steroids can be synthesised locally and act in the same cell without being released, indicating that a more complicated mechanism may be available in the physis [12, 13, 18, 29].

Delayed sexual maturation is often present in patients with SCFE, which might suggest a delay in closure of the physis. This creates a prolonged phase of weakness that makes the physis vulnerable for the effects of increasing load, mainly in the pre-existence of obesity. This delay can, thus, be involved in the slip of the epiphysis in SCFE and most children with this condition are, indeed, obese [1, 31].

Leptin and SCFE

Leptin is a protein hormone that plays a key role in regulating energy intake and energy expenditure. It is secreted mostly in the adipocytes of white adipose tissue. The level of circulating leptin is proportional to the total amount of fat in the body [13, 32]. In obese children, leptin levels are in direct proportion to the increase in body mass index (BMI) [13].

Leptin plays a permissive role in the onset of puberty and in pubertal growth. Leptin has a direct effect on the physis through leptin receptors and induces an increase in the width of the proliferative zone in a dose-dependent manner. This leads to the enhancement of proliferation and differentiation of the chondrocytes in the physis [12, 32]. Interestingly, in many patients with SCFE, an increase in the width of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones has been found [3–7]. Leptin has synergistic effects with the GH-IGF axis [12, 13] as a skeletal growth factor that, independent of the presence of GH, stimulates IGF-1 and IGF-1 receptor gene expression, indicating that a relation exists between mechanisms regulating weight and mechanisms regulating linear growth. Most likely, there are many links between leptin, adipocytes, GH, thyroxine, IGF-1 and chondrocytes, but the precise nature of these interactions is incompletely understood [32].

In obese children, serum GH levels are usually low. Indirect growth effects in obese children may not be induced by leptin but mediated by insulin. Obesity leads to insulin resistance and, thereby, to an increase of insulin blood levels. Insulin, an anabolic hormone, can, to a certain extent, promote growth as a result of the resemblance of the insulin and IGF-1 receptors. Insulin in high levels may bind to and activate the IGF-1 receptor. Furthermore, insulin may also stimulate accelerated growth by decreasing IGFBP-1, which leads to an increase of free IGF-1 and, consequently, in its biological activity [13].

In conclusion, SCFE is found more often in overweight children [31]. In obese children, leptin levels are increased. Leptin can cause an increase in the width of the proliferative zone, as has been found in SCFE.

Thyroid hormones and SCFE

Triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxin (T4) are tyrosine-based hormones, produced by the thyroid gland, that are primarily responsible for regulation of the metabolism. Thyroid hormones are regulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) by the anterior pituitary gland and thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH) by the hypothalamus.

Thyroid hormones are essential for longitudinal growth and normal skeletal maturation [12].

Circulating active thyroid hormone, T3, is formed by deionisation of T4 in the liver and kidney. T4 is derived from the thyroid gland [33].

T3 is essential for resting zone cells differentiation and hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation during bone formation. T3 has an indirect role on growth by influencing GH secretion and a direct role which has been shown by the presence of thyroid receptor α1 (TRα1) and thyroid receptor β (TRβ) presence in proliferating chondrocytes in the physis. T3 also regulates osteoblast activity, bone turnover and vascular invasion [14, 17, 18, 32, 33].

Tightly controlled concentrations are essential [14, 33]: childhood hypothyroidism causes growth failure, whereas thyrotoxicosis causes accelerated growth and slightly advanced bone age, which may lead to a moderately decreased final height.

The negative feedback loop of an important regulator of chondrocyte differentiation, Indian hedgehog–parathyroid hormone-related hormone (IHH–PTHrH), can be altered by the thyroid status. IHH belongs to a family of hedgehog proteins which plays a crucial role in embryonic development. IHH is secreted by pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes and is mainly a regulator of the pace of chondrocyte differentiation. It stimulates the local production of PTHrP. PTHrP acts on PTHrP receptor expressing pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes to maintain cell proliferation, reduce IHH production and complete a feedback loop in which PTHrP exerts a negative signal that inhibits hypertrophic differentiation [18, 33, 34]. The levels of expression in early hypertrophic chondrocytes of IHH and PTHrP are higher during early puberty than at later stages. It has been suggested that these proteins might be involved in the regulation of pubertal growth because a reduced expression of IHH–PTHrH is found during the progress of pubertal development [35]. The IHH–PTHrH feedback loop does not only regulate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation but also osteoblast differentiation, thereby, coupling chondrogenesis to osteogenesis [18, 36].

In conclusion, thyroid hormone exerts direct and indirect effects on the physis and facilitates physis closure at the end of puberty via signalling of the IHH–PTHrH pathway. As SCFE occurs at the end of puberty, where the closure of the physis is delayed, it could be possible that changes in thyroid hormones disturb the closure of the physis. Although there are hardly data available to determine the exact role of abnormalities in this axis in SCFE, Wells et al. [37] found that this was the most frequent abnormality in SCFE (see section “Diagnostic endocrine measurements in SCFE”).

Glucocorticoids and SCFE

Glucocorticoids (GC) are steroid hormones that are produced in the adrenal cortex. This production is regulated by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) by the anterior pituitary gland and corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) by the hypothalamus. Synthetic analogues of these hormones are widely used in the treatment of a variety of diseases. Mineralocorticoids are also produced by the adrenal gland but are not discussed in this review.

GC in physiological concentration facilitate normal growth, whilst in excess, GC suppress physis chondrocyte proliferation, induces prolonged resting period and reduces matrix synthesis with increased apoptosis. These effects are induced indirectly by alterations of the GH-IGH-1 axis and directly by local effects through GC receptors that are expressed in the physis [14, 18, 38–40]. Furthermore, GC inhibit the sulphation of cartilage matrix, mineralisation of new bone, osteoblast activity and stimulate bone resorption [22, 38, 40].

Long-term high GC concentrations cause growth retardation and osteoporosis. GC alters pulsatility and diminishes the secretion of GH from the pituitary through an elevation of hypothalamic somatostatin release. In addition, GC causes end-organ-insensitivity to the GH-IGF-1 axis by reducing expression of the GH and IGF-1 receptor in the physis. Furthermore, GC have direct effects on the growth plate mediated by the GC receptor, for example, increased apoptosis in the physis [14, 38–40]. The effects depend on the GC concentration used and the duration of exposure. GC growth-depressing effects may be partially counterbalanced by GH treatment [18, 40].

In conclusion, GC, mainly in long-term high concentrations, have negative effects on growth by direct and indirect mechanisms. The relation between SCFE and GC has not been yet demonstrated.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a group of fat-soluble steroids responsible for the intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphate. Vitamin D can be ingested as cholecalciferol or ergocalciferol and it can also be synthesised (from cholesterol) by sun exposure. In the liver, vitamin D is converted to calcidiol. Part of the calcidiol is converted in the kidneys to calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol), the biologically active form of vitamin D. Calcitriol circulates as a hormone in the blood, regulating the concentration of calcium and phosphate in the bloodstream and promoting growth, mineralisation and remodelling of bone.

Calcitriol has a direct action on epiphyseal chondrocytes. They stimulate cell growth in a dose-dependent, biphasic manner: proliferation is stimulated at low concentrations and inhibited by high concentrations. Also, it has synergetic effects with PTH on chondrocyte proliferation. A possible link between IGF and calcitriol has been described by showing an increased expression of IGF-1 receptor and/or local IGF-1 synthesis [21, 41]. Accelerated growth after the treatment of nutritional vitamin D, in vitamin-D-deficient patients, is mediated through activation of the GH-IGF1 system and suggests an important role of vitamin D as a link between the proliferating cartilage cells of the growth plate and GH-IGF1 secretion [41].

In the literature, an association has been described between seasonal variation and SCFE. This might be related to a decrease of vitamin D [42].

Chronic disease

Growth failure is a distinctive feature in children with chronic diseases. Some children with chronic diseases can suffer from inflammation, malnutrition and metabolic acidosis, which may result in abnormal GH-IGF-1 axis activity [43].

Chronic disease caused by inflammatory processes may, in some patients, lead to elevated titres of proinflammatory cytokines in serum. For effects on growth, the duration of exposure to these proinflammatory cytokines is important. The inflammatory cytokines interleukin 1β (Il1β), interleukin 6 (Il6) and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) may inhibit growth either directly at the physis or indirectly by reducing IGF-1 [43].

In addition, malnutrition in children with chronic diseases also plays an important role in growth impairment and, typically, circulating IGF-1 and GHBP levels are decreased [43, 44].

Metabolic acidosis in children with chronic renal failure (CRF) down-regulates cartilage matrix proteoglycans, collagen type 2 synthesis and expression of IGF-1 and IGF-1R in the physis, thereby, inducing GH resistance. Acidosis also changes the pulse amplitude of GH secretion, suppresses serum IGF-1 and decreases the expression of hepatic IGF-1 mRNA, hepatic growth hormone receptor (GHR) mRNA and epiphyseal IGF-1 mRNA [44–46].

There are few reports on the abnormalities of the physis in children with CRF. One case report [47] described an 8-year old girl who died of long-standing uraemia where an absent columnar cartilage and an irregular zone of calcification was found in the physis. Several authors claim that the columnar cartilage of the physis is irregularly formed in children with CRF [43–45, 47, 48], resembling the abnormalities of the physis that are observed in SCFE [3–7].

The development of renal osteodystrophy (ROD) is one of the most severe clinical problems complicating CRF. ROD represents a range of disorders, ranging from high-turnover bone disease as a result of hyperparathyroidism to low-turnover osteomalacia and adynamic bone. Secondary hyperparathyroidism may cause growth failure by modulating genes involved in enchondral bone formation and alternating the architecture of the physis [15, 44, 49].

The risk of SCFE and/or avascular necrosis in children with CRF as a result of rhGH treatment and ROD remains equivocal. However, it is advisable to obtain radiographs of the osseous structures before GH therapy in children with CRF and growth retardation has commenced [49].

In conclusion, chronic diseases in children cause growth impairment via different mechanisms acting on the GH-IGF-1 axis. Mainly in children with CRF, where ROD can become a severe complication, physis abnormalities can look like the same abnormalities that are observed in SCFE.

Diagnostic endocrine measurements in SCFE

Endocrine evaluation of patients with SCFE is often inconclusive. Many studies have reported on hormonal measurements in patients with SCFE, including measurements of triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), testosterone, 17B-oestradiol, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFB3), growth hormone (GH), PTH, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D and cortisol levels. All plasma and urinary hormone levels in patients with SCFE were similar to controls. Also, pubertal development was normal and comparable to the controls [50–53].

One retrospective study, published in 1988, reported decreased T3, testosterone and GH levels [51]. Papavasiliou et al. [54] investigated seven boys and seven girls suffering with SCFE [54] and found that the levels of FSH, LH and testosterone were lower than expected. The investigators claimed a possible temporary hormonal disorder, which may play a role in the development in SCFE. The results of these studies have to be interpreted with care. Hormone assays have changed dramatically since 1988 and the number of patients in the second study was very small.

Burrow et al. [55] investigated whether clinical characteristics (gender, height, age and bilateral involvement) were useful as a screening test for patients with underlying endocrinopathy. They found that 8 % of 166 patients had an endocrinopathy. Only short stature (below the tenth percentile for height) had a high sensitivity for detecting an underlying endocrinopathy. Wells et al. [37] documented, in 7 % of 131 patients with SCFE underlying endocrinopathies, mainly hypothyroidism. Interestingly, all of the patients developed bilateral SCFE.

Jingushi et al. [56] examined the serum of 13 children with SCFE, 22 healthy children and five children with cerebral palsy. In this study, significantly lower serum levels of M-PTH (mid-portion PTH) and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D was found, but this was only transient.

In conclusion, there is insufficient evidence to justify extensive hormonal screening in patients with SCFE. Temporary hormonal changes preceding SCFE have been suggested, but large prospective studies are needed in order to obtain sufficient evidence for such a hypothesis.

As a recommendation, one could test for endocrine and metabolic changes in young children (<10 years of age for girls and <12 years of age for boys) and if there is short stature below the tenth percentile for height. The most commonly affected hormones in endocrinopathies are thyroid hormones and growth hormone.

Conclusion

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is the result of high load across an abnormally weak physis. Children suffering from endocrinopathies, obesity and chronic diseases have an increased risk for the development of SCFE. However, the precise pathogenesis and aetiology of SCFE is still unknown. Many endocrine factors and hormones have been described that interact on the physis in several ways. Although studies which tested blood and urine samples in children with SCFE for hormonal abnormalities were inconclusive, the transient hormonal fluctuations during puberty might be the underlying factors.

Children with overt endocrinopathies like hyper- and hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadal states and hypopituitarism seem to have a higher chance of developing SCFE. This review shows that the growth hormone–insulin-like growth factor 1 (GH-IGF-1) axis, sex hormones, leptin, thyroid hormone with Indian hedgehog–parathyroid hormone-related hormone (IHH–PTrH) feedback loop and glucocorticoids are inter-related and have direct as well as indirect effects on the human physis.

In children with chronic diseases, the use of glucocorticoids and the presence of inflammation, malnutrition and metabolic acidosis influence the extracellular matrix (ECM), the quality of the chondrocytes, as well as the activity of the GH-IGF-1 axis.

SCFE is most likely the result of a multi-factorial event during adolescence when height and weight increase dramatically and the delicate balance in the various hormonal equilibria can be disturbed. Up to now, there are no screening or diagnostic tests available to predict patients at risk for SCFE.

Conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- AR

Androgen receptor

- CRF

Chronic renal failure

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- GC

Glucocorticoids

- GH

Growth hormone

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- IGF-1R

Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

- IGFBP3

Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3

- IHH

Indian hedgehog

- IHH–PTHrH

Indian hedgehog–parathyroid hormone-related hormone

- LH

Luteinising hormone

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MMP13

Matrix metalloproteinase 13

- MMP9

Matrix metalloproteinase 9

- PTH

Parathyroid hormone

- rhGH

Recombinant human growth hormone

- ROD

Renal osteodystrophy

- SCFE

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

- T3

Triiodothyronine

- T4

Thyroxine

References

- 1.Loder RT, Aronsson DD, Weinstein SL, Breur GJ, Ganz R, Leunig M. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Instr Course Lect. 2008;57:473–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dallek M, Jungbluth KH, Holstein AF. Studies on the arrangement of the collagenous fibers in infant epiphyseal plates using polarized light and the scanning electron microscope. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1983;101(4):239–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00379937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agamanolis DP, Weiner DS, Lloyd JK. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a pathological study. I. A light microscopic and histochemical study of 21 cases. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(1):40–46. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzzanti V, Falciglia F, Stanitski CL, Stanitski DF. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: physeal histologic features before and after fixation. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(5):571–577. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ippolito E, Bellocci M, Farsetti P, Tudisco C, Perugia D. An ultrastructural study of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: pathogenetic considerations. J Orthop Res. 1989;7(2):252–259. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mickelson MR, Ponseti IV, Cooper RR, Maynard JA. The ultrastructure of the growth plate in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(8):1076–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agamanolis DP, Weiner DS, Lloyd JK. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a pathological study. II. An ultrastructural study of 23 cases. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(1):47–58. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamczyk MJ, Weiner DS, Nugent A, McBurney D, Horton WE., Jr Increased chondrocyte apoptosis in growth plates from children with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(4):440–444. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000165138.60991.mL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falciglia F, Aulisa AG, Giordano M, Boldrini R, Guzzanti V. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: an ultrastructural study before and after osteosynthesis. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(3):331–336. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.483987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gat-Yablonski G, Yackobovitch-Gavan M, Phillip M. Nutrition and bone growth in pediatrics. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(5):1117–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scharschmidt T, Jacquet R, Weiner D, Lowder E, Schrickel T, Landis WJ. Gene expression in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Evaluation with laser capture microdissection and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(2):366–377. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillip M, Lazar L. The regulatory effect of hormones and growth factors on the pubertal growth spurt. Endocrinologist. 2003;13(6):465–469. doi: 10.1097/01.ten.0000098609.68863.ab. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillip M, Moran O, Lazar L. Growth without growth hormone. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2002;15(Suppl 5):1267–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siebler T, Robson H, Shalet SM, Williams GR. Glucocorticoids, thyroid hormone and growth hormone interactions: implications for the growth plate. Horm Res. 2001;56(Suppl 1):7–12. doi: 10.1159/000048127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenbaum LA, Del Rio M, Bamgbola F, Kaskel F. Rationale for growth hormone therapy in children with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2004;11(4):377–386. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olney RC. Regulation of bone mass by growth hormone. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41(3):228–234. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenbloom AL. Physiology of growth. Ann Nestlé. 2007;65(3):97–108. doi: 10.1159/000112232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Eerden BCJ, Karperien M, Wit JM. Systemic and local regulation of the growth plate. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(6):782–801. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green H, Morikawa M, Nixon T. A dual effector theory of growth-hormone action. Differentiation. 1985;29(3):195–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1985.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juul A, Meyer H, Muller J, Sippell W, Sharpe R, Grumbach M, Martin Ritzén E. The effects of oestrogens on linear bone growth. APMIS Suppl. 2001;109(103):S124–S134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2001.tb05758.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klaus G, Jux C, Leiber K, Hügel U, Mehls O. Interaction between insulin-like growth factor I, growth hormone, parathyroid hormone, 1(alpha),25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and steroids on epiphyseal chondrocytes. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1996;417:69–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pass C, Macrae VE, Ahmed SF, Farquharson C. Inflammatory cytokines and the GH/IGF-I axis: novel actions on bone growth. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27(3):119–127. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz HP, Bechtold S, Schmidt H. Hormonal regulation of growth. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2004;152(5):501–507. doi: 10.1007/s00112-004-0947-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell DR, Liu F, Baker BK, Lee PD, Hintz RL. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins as growth inhibitors in children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol. 1996;10(3):343–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00866778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen DB. Safety of growth hormone treatment of children with idiopathic short stature: the US experience. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76(Suppl 3):45–47. doi: 10.1159/000330159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eastell R. Role of oestrogen in the regulation of bone turnover at the menarche. J Endocrinol. 2005;185(2):223–234. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry RJ, Farquharson C, Ahmed SF. The role of sex steroids in controlling pubertal growth. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68(1):4–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bachrach BE, Smith EP. The role of sex steroids in bone growth and development: evolving new concepts. Endocrinologist. 1996;6(5):362–368. doi: 10.1097/00019616-199609000-00003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson O, Chrysis D, Pajulo O, Boman A, Holst M, Rubinstein J, Martin Ritzén E, Sävendahl L. Localization of estrogen receptors-(alpha) and -(beta) and androgen receptor in the human growth plate at different pubertal stages. J Endocrinol. 2003;177(2):319–326. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1770319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chagin AS, Sävendahl L. Brief report: GPR30 estrogen receptor expression in the growth plate declines as puberty progresses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(12):4873–4877. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilcox PG, Weiner DS, Leighley B. Maturation factors in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8(2):196–200. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198803000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kay’s SK, Hindmarsh PC. Catch-up growth: an overview. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2006;3(4):365–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robson H, Siebler T, Shalet SM, Williams GR. Interactions between GH, IGF-I, glucocorticoids, and thyroid hormones during skeletal growth. Pediatr Res. 2002;52(2):137–147. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sävendahl L. Hormonal regulation of growth plate cartilage. Horm Res. 2005;64(Suppl 2):94–97. doi: 10.1159/000087764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kindblom JM, Nilsson O, Hurme T, Ohlsson C, Sävendahl L. Expression and localization of Indian hedgehog (Ihh) and parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrP) in the human growth plate during pubertal development. J Endocrinol. 2002;174(2):R1–R6. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.174R001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emons J, Chagin AS, Sävendahl L, Karperien M, Wit JM. Mechanisms of growth plate maturation and epiphyseal fusion. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;75(6):383–391. doi: 10.1159/000327788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells D, King JD, Roe TF, Kaufman FR. Review of slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with endocrine disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13(5):610–614. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199313050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed SF, Sävendahl L. Promoting growth in chronic inflammatory disease: lessons from studies of the growth plate. Horm Res. 2009;72(Suppl 1):42–47. doi: 10.1159/000229763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klaus G, Jux C, Fernandez P, Rodriguez J, Himmele R, Mehls O. Suppression of growth plate chondrocyte proliferation by corticosteroids. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(7):612–615. doi: 10.1007/s004670000344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehls O, Himmele R, Hömme M, Kiepe D, Klaus G. The interaction of glucocorticoids with the growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor axis and its effects on growth plate chondrocytes and bone cells. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14(Suppl 6):1475–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soliman AT, Al Khalaf F, AlHemaidi N, Al Ali M, Al Zyoud M, Yakoot K. Linear growth in relation to the circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor I, parathyroid hormone, and 25-hydroxy vitamin D in children with nutritional rickets before and after treatment: endocrine adaptation to vitamin D deficiency. Metab Clin Exp. 2008;57(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skelley NW, Papp DF, Lee RJ, Sargent MC. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis with severe vitamin D deficiency. Orthopedics. 2010;33(12):921. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20101021-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Luca F. Impaired growth plate chondrogenesis in children with chronic illnesses. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(5):625–629. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000214966.60416.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahan JD, Warady BA, Fielder P, Gipson DS, Greenbaum L, Juarez-Congelosi MD, Kaskel FJ, Langman CB, Long LD, Macdonald D, Miller DH, Mitsnefes MM, Panzarino VM, Rosenfeld RG, Seikaly MG, Stabler B, Watkins SL. Assessment and treatment of short stature in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease: a consensus statement. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(7):917–930. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saborio P, Krieg RJ, Jr, Chan W, Hahn S, Chan JC. Pathophysiology of growth retardation in chronic renal failure. Zhonghua Min Guo Xiao Er Ke Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi. 1998;39(1):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tönshoff B, Kiepe D, Ciarmatori S. Growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor system in children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(3):279–289. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritz E, Krempien B, Mehls O, Mallushe H, Strobel Z, Zimmermann H. Skeletal complications of renal insufficiency and maintenance haemodialysis. Nephron. 1973;10(2):195–207. doi: 10.1159/000180187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santos F, Carbajo-Pérez E, Rodríguez J, Fernández-Fuente M, Molinos I, Amil B, García E. Alterations of the growth plate in chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(3):330–334. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fine RN. Growth hormone in children with chronic renal insufficiency and end-stage renal disease. Endocrinologist. 1998;8(3):160–169. doi: 10.1097/00019616-199805000-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brenkel IJ, Dias JJ, Davies TG, Iqbal SJ, Gregg PJ. Hormone status in patients with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(1):33–38. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2521639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mann DC, Weddington J, Richton S. Hormonal studies in patients with slipped capital femoral epiphysis without evidence of endocrinopathy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8(5):543–545. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicolai RD, Grasemann H, Oberste-Berghaus C, Hövel M, Hauffa BP. Serum insulin-like growth factors IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in children with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8(2):103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Razzano CD, Nelson C, Eversman J. Growth hormone levels in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(6):1224–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papavasiliou KA, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA, Pournaras J. Potential influence of hormones in the development of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a preliminary study. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2007;16(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e328010b73d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burrow SR, Alman B, Wright JG. Short stature as a screening test for endocrinopathy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(2):263–268. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.10554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jingushi S, Hara T, Sugioka Y. Deficiency of a parathyroid hormone fragment containing the midportion and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in serum of patients with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17(2):216–219. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199703000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]