Abstract

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) may be an early marker of acute kidney injury (AKI), but elevated NGAL occurs in a wide range of systemic diseases. Because intensive care patients have high levels of comorbidity, our objective was to conduct a systematic review of the literature to evaluate the value of plasma and urinary NGAL to predict AKI in these patients. We conducted a systematic electronic literature search of MEDLINE through PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library for all English language research publications evaluating the predictive value of plasma or urinary NGAL (or both) for AKI in adult intensive care patients. Two authors independently extracted data by using a standardized extraction sheet including study characteristics, type of NGAL measurements, and type of outcome measures. The primary summary measure was area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AuROC) for NGAL to predict study outcomes. Eleven studies with a total of 2,875 (range of 20 to 632) participants were included: seven studies assessed urinary NGAL and six assessed plasma NGAL. The included studies varied in design, including observation period from NGAL sampling to AKI follow-up (range of 12 hours to 7 days), definition of baseline creatinine value, and urinary NGAL quantification method (normalizing to urinary creatinine or absolute concentration). AuROC values for the prediction of AKI ranged from 0.54 to 0.98. Five studies reported AuROC for use of renal replacement therapy ranging from 0.73 to 0.89, and four studies reported AuROC for mortality ranging from 0.58 to 0.83. There were no differences in the predictive values of urinary and plasma NGAL. The heterogeneity in study design and results made it difficult to evaluate the value of NGAL to predict AKI in intensive care patients. NGAL seems to have reasonable value in predicting use of renal replacement therapy but not mortality.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is frequent in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) and is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality [1]. For many years, serum creatinine (sCr) has been the principal marker of AKI even though it is widely acknowledged that sCr is not reliable during acute changes in kidney function and varies with gender, age, muscle mass, dietary intake, and hydration status. sCr does not reflect real-time decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), because creatinine has to accumulate as a result of a decrease in GFR before increased concentrations are detectable. A real-time marker of AKI may allow the institution of earlier, and therefore more effective, renoprotective therapies; one such marker is neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL).

NGAL, also known as lipocalin-2 (lcn2), is a 25-kDa protein and member of the lipocalin superfamily [2]. It was named after its expression in neutrophils and found to have bacteriostatic effects by interfering with bacterial siderophore-mediated iron uptake [3]. NGAL expression has been shown to increase in response to inflammation in epithelial cells regularly exposed to microorganisms [2] and in response to cellular oxidative stress [4]. Increases in plasma NGAL have been reported in a wide range of systemic diseases, including acute infections, pancreatitis, heart failure, and cancer [5-8], but in recent years the potential role of plasma and urinary NGAL as early markers of AKI has been studied. A study in mice showed marked urinary NGAL increase within 2 hours of renal injury, by far preceding conventional markers of AKI [9]. In children undergoing elective cardiac surgery, plasma and urinary NGAL measurements at 2 hours after surgery were highly predictive of the development of AKI within 72 hours; area under receiver operating characteristic curves (AuROCs) were 0.91 and 0.99, respectively [10]. Differences between plasma and urinary NGAL kinetics are likely because of local synthesis and excretion of NGAL in the distal tubules of the nephron, further supported by a calculated fractional NGAL excretion of more than 100% [11].

Patients admitted to the ICU have higher levels of comorbidity than other patient categories, possibly confounding the value of NGAL as a marker of AKI. This is supported by a study showing higher plasma and urinary NGAL levels in septic AKI versus non-septic AKI patients [12]. Also, the exact onset of a renal insult in intensive care patients is often less clear, and this further hampers the interpretation of elevated NGAL in these patients.

Therefore, the aim of this review was to systematically evaluate the predictive value of plasma and urinary NGAL measurement for AKI in ICU patients. Given the presumed confounding increase in measured NGAL during acute infections, we aimed to do a subgroup analysis in patients with sepsis.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [13]. The following inclusion criteria were defined a priori: studies of adults in an ICU setting evaluating the value of urinary or plasma NGAL measurements (or both) as an early marker of AKI. Studies not performed primarily in an ICU setting (for example, surgery) and articles not in English were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

We conducted an electronic search in MEDLINE through PUBMED database, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library in February 2012. The search was conducted with the following search string: (NGAL OR 'neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin' OR lipocalin-2 OR lcn2) AND ('acute kidney injury' OR AKI OR 'acute renal injury' OR ARI OR 'acute renal failure' OR ARF OR 'acute kidney failure' OR AKF). Two authors (PH and MW) independently screened all articles for inclusion. Differences were discussed and resolved with a third party (AP). A supplemental search was conducted by screening citations of review articles and research papers to identify potential studies not included in the search string.

Study selection and data extraction

For studies that fulfilled inclusion criteria, two authors (PH and MW) independently extracted data by using a standardized extraction sheet (Supplemental Digital Content 1). When differences in opinion occurred, they were resolved by discussion involving a third party (AP). Data were extracted from each included trial on (a) study characteristics (including setting, inclusion and exclusion criteria, year of publication, and population size), (b) type of NGAL measurements (including plasma or urine or both, assay used, and timing and frequency of sampling), and (c) type of outcome measure (including AKI definition, observation period for AKI, use of renal replacement therapy (RRT), and mortality).

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias in individual studies

There are, to our knowledge, no specific guidelines on how to assess the methodological quality of individual studies of diagnostic markers. We used the following criteria to assess the risk of bias: (a) prospective study design and analysis, (b) a validated diagnostic scale defining AKI: Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) or Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease (RIFLE), (c) clearly described selection criteria for study participants, (d) sufficient description of NGAL measurements permitting replication of the study, and (e) any potential conflict of interests described.

Both the RIFLE [14] criteria and the AKIN [15] criteria were accepted as validated diagnostic scales as they have shown comparable predictive values for mortality and ICU length of stay in a large cohort of ICU patients [16]. For studies using sCr criteria only, AKI definition was determined by modified RIFLE/AKIN and still accepted as valid. Studies fulfilling four or five criteria were classified as studies having low risk of bias, and if three criteria were fulfilled, the studies were classified as having medium risk of bias. Otherwise, they were classified as studies having high risk of bias.

Summary measures

AuROC was the primary measure for the value of NGAL to predict AKI, RRT, and mortality. Furthermore, the AuROC of AKI stratified for severity was extracted if reported. If NGAL thresholds were reported, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were extracted. If the study conducted a sensitivity analysis to exclude patients with reduced kidney function on entry, AuROC and method were extracted.

Meta-analysis and subgroup analysis

We planned to conduct a meta-analysis of the predictive value of plasma and urinary NGAL for AKI and a subgroup analysis of patients with sepsis.

Results

Study trial flow

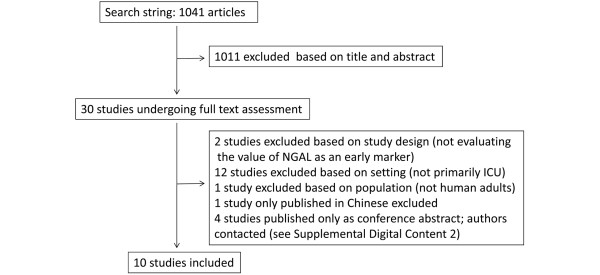

The search string produced a total of 1,041 potentially relevant articles. No additional studies were found in the supplemental hand search, but one unpublished study was identified through personal contact. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of study selection.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection. ICU, intensive care unit; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Study characteristics

We included 11 studies (Table 1); for further study characteristics, see Supplemental Digital Content. The studies were published between 2009 and 2011; one study was only in abstract form, and one was unpublished at the time of analysis. Nine studies were in general ICU patients, one was in ICU patients with multiple trauma, and one study was in patients with septic shock. The 11 studies included a total number of 2,875 patients (range of 20 to 632).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Year | Population size | Patients | NGAL sample | Assay | AKI definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Geus et al. [21] | 2011 | 632 | General ICU | Plasma and urine | FIA | RIFLE (sCr) |

| Endre et al. [22,23] | 2011 | 528 | General ICU | Urine | ELISA | AKIN or RIFLE (sCr) |

| Doi et al. [24] | 2011 | 339 | General ICU | Urine | ELISA | RIFLE (sCr) |

| Cruz et al. [25] | 2010 | 301 | General ICU | Plasma | FIA | RIFLE (sCr + UO) |

| Constantin et al. [26] | 2010 | 88 | General ICU | Plasma | FIA | RIFLE (sCr) |

| Mårtensson et al. [27] | 2010 | 25 | ICU patients with septic shock | Plasma and urine | RIA | RIFLE and AKIN (sCr + UO) |

| Metzger et al. [28] | 2010 | 20 | General ICU | Urine | ELISA | AKIN (sCr + UO) |

| Siew et al. [29] | 2009 | 451 | General ICU | Urine | ELISA | AKIN (sCr) |

| Makris et al. [30] | 2009 | 31 | ICU patients with multiple trauma | Urine | ELISA | RIFLE (sCr + UO) |

| Kokkoris et al.a [31] | 2011 | 91 | General ICU | Plasma | FIA | RIFLE (sCr + UO) |

| Linko et al.b | 2012 | 369 | General ICU | Plasma | FIA | - |

aStudy published as abstract only; author contacted to obtain extracted data; bstudy unpublished. AKI, acute kidney injury; AKIN, Acute Kidney Injury Network; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FIA, fluorescence immunoassay; RIA, radioimmunoassay; RIFLE, Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease; sCr, serum creatinine; UO, urine output.

Five studies measured urinary NGAL only, four measured plasma NGAL only, and two studies measured both plasma and urine; that is a total of seven studies of urinary NGAL and six of plasma NGAL. All studies of plasma NGAL reported absolute concentration, whereas urinary NGAL studies varied: three reported NGAL in absolute concentration, and four reported NGAL normalized to urinary creatinine.

The included studies varied in kidney-specific exclusion criteria: some excluded patients with history of chronic kidney disease, and others excluded patients based on admission sCr. AKI definition varied among studies: four used either RIFLE or AKIN creatinine and urine output criteria, four used modified either RIFLE or AKIN with creatinine criteria only, one used both AKIN and RIFLE criteria, and one reported two AuROC values using modified AKIN and modified RIFLE criteria, respectively. In one study AKI was not reported, but the use of RRT was. The included studies used different definitions of baseline creatinine: some used admission sCr, and others used sCr obtained prior to admission. When creatinine obtained prior to admission was used, 28% to 51% of patients had missing values when reported. The handling of missing baseline values varied: some used admission creatinine, some used back calculating with the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula, and one study used multiple imputation. Seven studies used NGAL samples at or close to admission to evaluate AuROC for AKI, whereas two studies reported that AuROC values were retrospectively based on NGAL samples taken on a fixed time point prior to AKI (12 hours and 2 to 3 days, respectively).

According to our predefined risk-of-bias assessment, nine studies had low and two studies medium risk of bias (Table 2). In all studies having use of RRT as an outcome measure, clinicians were blinded to NGAL concentrations, reducing the risk of NGAL values affecting the decision to use RRT.

Table 2.

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias in the included studies

| Study | Prospective observational study design | Clearly described selection criteria | Validated diagnostic scale for AKI used | Clearly described NGAL measurements | Conflict of interests | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Geus et al. [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Endre et al. [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Doi et al. [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Low |

| Cruz et al. [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Low |

| Constantin et al. [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Low |

| Mårtensson et al. [27] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Medium |

| Metzger et al. [28] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Siew et al. [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Low |

| Makris et al. [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Low |

| Kokkoris et al.a [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Low |

| Linko et al.b | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | No | Low |

aStudy published as abstract only; author contacted to obtain extracted data; bstudy unpublished. AKI, acute kidney injury; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Value of NGAL to predict study outcomes

Table 3 shows the results of the included studies' primary analyses of the value of NGAL to predict AKI, RRT, and mortality. The incidence of AKI across the studies ranged from 14% to 72% of patients included in the primary analyses. The follow-up time from the assessment of NGAL to AKI ranged from 12 hours to 1 week. The AuROC values for prediction of AKI ranged from 0.54 to 0.98 in all included studies and from 0.54 to 0.92 in the studies of general ICU patients. In five studies, AuROC for prediction of use of RRT was performed and these ranged from 0.73 to 0.89. The four studies reporting prediction of both RRT and AKI had AuROCs of 0.79 to 0.89 for use of RRT and 0.55 to 0.92 for AKI. In five studies, prediction of mortality was assessed and AuROCs ranged from 0.58 to 0.83. In four studies, author-defined cutoff values of NGAL for AKI were reported (Table 3). In four studies, sensitivity analyses were conducted to exclude patients with pre-existing reduced kidney function (Table 4). In the remaining studies in which sensitivity analyses were not performed, kidney-specific characteristics of patients included in the primary analyses were presented.

Table 3.

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and prediction of study outcome measures

| Study | AKI events, percentage (number) | 12 hours | 24 hours | AuROC 48 hours | 72 hours | 5 days | 7 days | RRT events, percentage (number) | RRT AuROC | Mortality events, percentage (number) | Mortality AuROC | NGAL cutoff value for AKI | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Geus et al. [21] (plasma) | 27% (171) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 4% (28) | 0.88 ± 0.06 | Hospital 22% (137) | 0.63 ± 0.06 | - | - | - | - | - |

| de Geus [12]et al. (urine) | 27% (171) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 4% (28) | 0.89 ± 0.04 | Hospital 22% (137) | 0.64 ± 0.06 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Endre et al.a [22] (urine) | 22% (82) | - | - | 0.55(0.48-0.67) | - | - | 0.68(0.56-0.80) | 4% (19) | 0.79(0.65-0.94) | 7 days 10% (53) | 0.66(0.57-0.74) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Doi et al. [24] (urine) | 39% (131) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.70(0.63-0.75) | - | - | 14 days 4% (14) | 0.83(0.69-0.91) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cruz et al.b [25] (plasma) | 14% (43) | - | - | 0.78(0.65-0.90) | - | 0.67(0.55-0.79) | - | 5% (15) | 0.82(0.70-0.95) | in ICU 17% (52) | 0.67(0.58-0.77) | 150 ng/mL 48 hours | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 0.97 |

| 5 days | 0.46 | 0.80 | 0.26 | 0.91 | ||||||||||||

| Constantin et al. [26] (plasma) | 59% (52) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.92(0.85-0.97) | 8% (7) | 0.79(0.69-0.87) | in ICU 19% (17) | - | 155 ng/mL | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.80 |

| Mårtensson et al. [27] (plasma) | 72% (18) | 0.67(0.39-0.94) | - | - | - | - | - | 4% (1) | - | 30 days 24% (6) | - | 120 ng/mL | 0.83 | 0.50 | - | - |

| Mårtensson et al. [27] (urine) | 72% (18) | 0.86(0.68-1.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 4% (1) | - | 30 days 24% (6) | - | 68 ng/mgCr | 0.71 | 1.0 | - | - |

| Metzger et al. [28] (urine) | 45% (9) | - | - | 0.54c | - | - | - | 20% (4) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Siew et al. [29] (urine) | 19% (86) | - | 0.71(0.63-0.78) | 0.64(0.57-71) | - | - | - | 3% (17) | - | 28 days 17% (83) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Makris et al. [30] (urine) | 35% (11) | - | - | - | - | 0.98(0.82-0.98) | - | - | - | in ICU 23% (7) | - | 25 ng/mL | 0.91 | 0.95 | - | - |

| Kokkoris et al. [31] (plasma) | 26% (24) | - | - | - | 0.78 | - | - | 8% (7) | - | in ICU 33% (30) | - | 110 ng/mL | 0.71 | 0.82 | - | - |

| Linko et al. d (plasma) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13% (47) | 0.73(0.66-0.81) | 90 days 30% (111) | 0.58(0.52-0.65) | - | - | - | - | - |

Area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AuROC): (95% confidence interval) or ± 2 × standard error. aOf 528 included patients, 147 had acute kidney injury (AKI) on entry and were not included in primary analysis of AKI but were included in analysis of renal replacement therapy (RRT) and mortality. Study reported AuROC at 48 hours with Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria, whereas AuROC at 7 days was with RIFLE criteria sustained for a minimum of 24 hours; bof 301 included patients, 90 had AKI on entry and were not included in calculation of AuROC values; cauthor reported AuROC based on sample 2 to 3 days prior to AKI. dstudy unpublished. ADQI, Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ICU, intensive care unit; lcn2, lipocalin-2; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; RIFLE, Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; sCr, serum creatinine.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses for prediction of acute kidney injury excluding patients with author-defined reduced kidney function on entry

| Study | Patients excluded | Number of patients included in analysis | AuROC sensitivity analysis | AuROC primary analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Geus et al. [21] (plasma) | eGFR <60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 at admission | 498, of whom 7% (37) developed AKI | AKI within 7 days 0.75 ± 0.10 | AKI within 7 days 0.77 ± 0.05 |

| de Geus et al. [21] (urine) | eGFR <60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 at admission | 498, of whom 7% (37) developed AKI | AKI within 7 days 0.79 ± 0.10 | AKI within 7 days 0.80 ± 0.04 |

| Doi et al. [24] (urine) | AKI at admission | 274, of whom 24% (66) developed AKI | AKI within 7 days 0.60 (0.52-0.67) | AKI within 7 days 0.70 (0.63-0.75) |

| Constantin et al. [26] (plasma) | AKI at admission | 56, of whom 36% (20) developed AKI | AKI within 7 days 0.96 (0.86-0.99) | AKI within 7 days 0.92 (0.85-0.97) |

| Siew et al. [29] (urine) | eGFR <75 mL/minute/1.73 m2 at admission | 275, of whom 7% (18) developed AKI | AKI within 24 hours 0.77 (0.64-0.90) | AKI within 24 hours 0.71 (0.63-0.78) |

| Cruz et al. [25] (plasma) | Only patients without AKI at enrollment were included in primary analyses. | |||

| Makris et al. [30] (urine) | Only patients with sCr <1.5 mg/dL (133 μmol/L) on entry were included in primary analysis. | |||

| Endre et al. [22] (urine) | Only patients without AKI on entry were included in primary analysis. | |||

| Metzger et al. [28] (urine) | Only patients without AKI within 48 hours of admission were included in primary analysis. | |||

| Mårtensson et al. [27] (plasma) | Only patients with eGFR >60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 on entry were included in primary analysis. | |||

| Mårtensson et al. [27] (urine) | Only patients with eGFR >60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 on entry were included in primary analysis. | |||

| Kokkoris et al. [31] (plasma) | Only patients with known baseline sCr <1.6 mg/dL (141 μmol/L) were included in primary analysis. | |||

Area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AuROC) presented as ± 2 × standard error or (95% confidence interval). AKI, acute kidney injury; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; sCR, serum creatinine.

Two studies conducted analyses stratifying for AKI severity. The results are presented in Table 5, showing increase in AuROC values with increasing degree of AKI. Our plans of conducting a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis of patients with sepsis were aborted because of heterogeneity and lack of data, respectively; see the Discussion for further argumentation.

Table 5.

Values of area under receiver operating characteristic curve stratified for severity of acute kidney injury

| Study | RIFLE R or above | RIFLE I or above | RIFLE F | AKIN I | AKIN II, III combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Geus et al. [21] (plasma) | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | - | - |

| de Geus et al. [21] (urine) | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | - | - |

| Siew et al. [29] (urine) | - | - | - | 0.62 (0.54-0.70) | 0.71 (0.59-0.83) |

Area under receiver operating characteristic curve presented as ± 2 × standard errors or (95% confidence intervals). AKIN, Acute Kidney Injury Network; RIFLE, Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to systematically evaluate articles investigating the value of plasma or urinary NGAL (or both) to predict AKI in adult ICU patients. The results of the included studies varied greatly, as did those of studies in general ICU patients only. Put another way, the results ranged from a predictive value equivalent to flipping a coin to NGAL being an excellent early marker of AKI. A reason for these results may be the marked differences in study design. The observation period for AKI varied greatly between studies, but there was no clear association between length of observation period and AuROC as studies with observation periods of 5 days or more appeared to have higher AuROC values. However, the two studies reporting AuROC values for more than one observational period using same AKI definition showed a decline in AuROC with longer observation period. Also, kidney-specific characteristics of patients included in the calculation of AuROC varied, making direct comparison between studies less reliable; this probably contributed to the marked range in AKI incidence even among studies performed in general ICU populations.

When RIFLE or AKIN criteria are used to define AKI, a baseline creatinine value for each included patient is required. The included studies used different definitions of baseline creatinine (see Supplemental Digital Content), and this may have caused one patient to be classified as having AKI in one study but not in another, even though the studies appeared to use the same criteria for AKI. Some studies excluded patients with reduced kidney function at inclusion, whereas others conducted a sensitivity analysis based on author-defined kidney impairment. We believe the latter approach to be more appropriate because it provides more information to clinicians and researchers. Moreover, the varying methods in the individual studies make it difficult to compare the results.

For the studies reporting the secondary outcomes, use of RRT and mortality NGAL performed more homogenously than for AKI. Studies reporting AuROC for both use of RRT and AKI showed that NGAL performed more homogenously well in predicting use of RRT than in predicting AKI. This finding, combined with the finding that NGAL performed better with increasing severity of AKI, indicates that NGAL has greater potential as an early marker of severe AKI in the ICU. A possible explanation is that ICU populations have higher levels of comorbidity and thereby other sources of NGAL, but further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. For the five studies reporting the value of NGAL to predict mortality, NGAL performed homogenously poorly with the exception of one study with low mortality rate.

Two studies evaluated both plasma and urinary NGAL. The largest study of this review with 632 participants found no significant difference between AuROC for plasma and urinary NGAL; this is interesting given the presumed differences in metabolism of plasma and urinary NGAL.

As noted, some studies used urinary NGAL-creatinine ratios as opposed to absolute NGAL concentrations. A recent study showed significant increase in intra-individual variations in urinary NGAL when using absolute concentrations compared with concentrations normalized to creatinine [17]. Using NGAL concentrations normalized to creatinine, however, has also been criticized, especially during non-steady state as in AKI, in which urinary creatinine excretion rate changes over time and there is active tubular secretion of creatinine [18]. The recommendation given in the latter article was to use timed collections providing biomarker excretion rates. A comparison of the three methods of measuring NGAL was conducted by Endre and colleagues [19], who showed comparable AuROC values for NGAL to predict outcomes, though favoring normalizing to urinary creatinine.

We aimed to conduct a meta-analysis, but given the variations in study design, we do not believe that meta-analyses would contribute useful data on the value of NGAL to predict AKI. As only one study was conducted exclusively in patients with sepsis and none of the other studies reported AuROC for this subgroup, the planned subgroup analysis was also aborted.

There are general limitations and challenges when conducting studies evaluating the value of NGAL to predict AKI. Firstly, the use of creatinine-based AKI definition as reference standard is challenging. Creatinine is not an ideal marker of AKI and this poses a challenge when conducting studies evaluating potential early markers of AKI. A recent meta-analysis of cardiac surgical and ICU patients proposed that an NGAL increase in patients not fulfilling conventional AKI criteria may be a sign of subclinical AKI with significantly increased risk of need of RRT and not a false-positive test result as often reported [20]. Whether or not this theory applies when exclusively examining ICU patients with presumably more abundant sources of confounding NGAL is not known, but further studies are called for. Secondly, the handling of missing baseline creatinine values may confound results. The Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) recommends back-calculating from the MDRD formula from an estimated GFR of 75 mL/minute per 1.73 m2 [14], but controversy exists, resulting in great variations in the handling of missing baseline values. Thirdly, the observation period from NGAL sampling to AKI by conventional criteria poses a challenge. The longer the observation period, the higher the risk of including renal insults acquired after NGAL sampling. Conversely, if the time period is short, there is a risk of excluding late AKI.

More studies are needed to further clarify the role of NGAL as an early marker of AKI in intensive care patients. Some form of consensus of study design is paramount in order to make comparison of results more meaningful. Studies on selected patient groups in the ICU would be desirable as general ICU patients constitute a heterogenic population. We recommend calculating AuROC for AKI based on patients not fulfilling AKI criteria on entry and applying ADQI recommendations when missing baseline creatinine value obtained prior to admission. The proportion of patients with missing baseline creatinine should be stated, and a sensitivity analysis excluding these patients would be desirable. Given the characteristics of NGAL, an AKI observation period of approximately 3 to 5 days seems to be appropriate. The optimal quantification method of urinary NGAL has not yet been established, and we recommend reporting both absolute concentration and concentration normalized to creatinine and, if possible, the NGAL excretion rate.

Conclusions

This systematic review has shown that studies evaluating plasma and urinary NGAL as early markers of AKI in ICU patients showed great heterogeneity in design and results. The results varied from NGAL being virtually useless to NGAL being an excellent early marker of AKI. The results for the secondary outcome measures use of RRT and mortality were more homogenous, with NGAL being a reasonable predictor of use of RRT. In contrast, NGAL appeared to be a poor predictor of mortality.

Key messages

• The results of the value of plasma and urinary NGAL in predicting AKI in intensive care patients varied, and so NGAL cannot at present be recommended as a marker of AKI in the ICU.

• Differences in study design, including observation period for AKI, NGAL quantification method, and kidney-specific patient characteristics, made comparison across studies less reliable and led to the aborting of a planned meta-analysis.

• Studies investigating the value of NGAL in predicting the use of renal replacement therapy showed homogenously reasonable predictive value of NGAL.

Abbreviations

ADQI: Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative; AKI: acute kidney injury; AKIN: Acute Kidney Injury Network; AuROC: area under receiver operating characteristic curve; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; ICU: intensive care unit; lcn2: lipocalin-2; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; NGAL: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; RIFLE: Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease; RRT: renal replacement therapy; sCr: serum creatinine.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The Department of Intensive Care, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet has received support for research from Bioporto (Gentofte, Denmark), B Braun Medical (Melsungen, Germany), and Fresenius Kabi (Bad Homburg, Germany).

Authors' contributions

PBH contributed to study design, helped to screen all potential manuscripts for inclusion and collect the data, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. NH and AP contributed to study design. MW helped to screen all potential manuscripts for inclusion and collect the data. All authors contributed to revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Study Selection, Quality Assessment & Data Extraction Form.

Contributor Information

Peter B Hjortrup, Email: pbhjortrup@gmail.com.

Nicolai Haase, Email: nicolai.haase@rh.regionh.dk.

Mik Wetterslev, Email: m.r.wetterslev@gmail.com.

Anders Perner, Email: Anders.Perner@regionh.dk.

Acknowledgements

We thank John Pickering for providing supplemental data for our intended meta-analysis, Johan Mårtensson and Alp Ikizler for declaring an intention of providing data before the meta-analysis was aborted, Stelios Kokkoris for providing data equivalent to data extracted from published articles, and Ville Pettilä for providing data from the currently unpublished study.

References

- Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Ronco C. Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2005;294:813–818. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen L, Cowland JB, Borregaard N. Human neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and homologous proteins in rat and mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482:272–283. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(00)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, Strong RK. The Neutrophil Lipocalin NGAL Is a Bacteriostatic Agent that Interferes with Siderophore-Mediated Iron Acquisition. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudkenar MH, Kuwahara Y, Baba T, Roushandeh AM, Ebishima S, Abe S, Ohkubo Y, Fukumoto M. Oxidative stress induced lipocalin 2 gene expression: addressing its expression under the harmful conditions. J Radiat Res. 2007;48:39–44. doi: 10.1269/jrr.06057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjaertoft G, Foucard T, Xu S, Venge P. Human neutrophil lipocalin (HNL) as a diagnostic tool in children with acute infections: A study of the kinetics. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:661–666. doi: 10.1080/08035250510031610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Kaur S, Muddana V, Sharma N, Wittel UA, Papachristou GI, Whitcomb D, Brand RE, Batra SK. Elevated Serum Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Is an Early Predictor of Severity and Outcome in Acute Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2050–2059. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yndestad A, Landrø L, Ueland T, Dahl CP, Flo TH, Vinge LE, Espevik T, Frøland SS, Husberg C, Christensen G, Dickstein K, Kjekshus J, Øie E, Gullestad L, Aukrust P. Increased systemic and myocardial expression of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in clinical and experimental heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1229–1236. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du ZP, Lv Z, Wu BL, Wu ZY, Shen JH, Wu JY, Xu XE, Huang Q, Shen J, Chen HB, Li EM, Xu LY. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and its receptor: independent prognostic factors of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:69–74. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.083907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra J, Ma Q, Prada A, Mitsnefes M, Zahedi K, Yang J, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a novel early urinary biomarker for ischemic renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2534–2543. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000088027.54400.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, Mitsnefes MM, Ma Q, Kelly C, Ruff SM, Zahedi K, Shao M, Bean J, Mori K, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Ott KM, Mori K, Li JY, Kalandadze A, Cohen DJ, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Dual action of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:407–413. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshaw SM, Bennett M, Haase M, Haase-Fielitz A, Egi M, Morimatsu H, D'amico G, Goldsmith D, Devarajan P, Bellomo R. Plasma and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in septic versus non-septic acute kidney injury in critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:452–461. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–R212. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshaw SM, George C, Bellomo R. for the ANZICS Database Management Committee. A comparison of the RIFLE and AKIN criteria for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1569–1574. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanaye P, Rozet E, Krzesinski JM, Cavalier E. Urinary NGAL measurement: biological variation and ratio to creatinine. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:390. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waikar SS, Sabbisetti VS, Bonventre JV. Normalization of urinary biomarkers to creatinine during changes in glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int. 2010;78:486–494. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralib AM, Pickering JW, Shaw GM, Devarajan P, Edelstein CL, Bonventre JV, Endre ZH. Test characteristics of urinary biomarkers depend on quantitation method in acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:322–333. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase M, Devarajan P, Haase-Fielitz A, Bellomo R, Cruz DN, Wagener G, Krawczeski CD, Koyner JL, Murray P, Zappitelli M, Goldstein SL, Makris K, Ronco C, Martensson J, Martling CR, Venge P, Siew E, Ware LB, Ikizler TA, Mertens PR. The outcome of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin-positive subclinical acute kidney injury: a multicenter pooled analysis of prospective studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1752–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Geus HR, Bakker J, Lesaffre EM, le Noble JL. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin at ICU admission predicts for acute kidney injury in adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:907–914. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1214OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre ZH, Pickering JW, Walker RJ, Devarajan P, Edelstein CL, Bonventre JV, Frampton CM, Bennett MR, Ma Q, Sabbisetti VS, Vaidya VS, Walcher AM, Shaw GM, Henderson SJ, Nejat M, Schollum JB, George PM. Improved performance of urinary biomarkers of acute kidney injury in the critically ill by stratification for injury duration and baseline renal function. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1119–1130. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre ZH, Walker RJ, Pickering JW, Shaw GM, Frampton CM, Henderson SJ, Hutchison R, Mehrtens JE, Robinson JM, Schollum JB, Westhuyzen J, Celi LA, McGinley RJ, Campbell IJ, George PM. Early intervention with erythropoietin does not affect the outcome of acute kidney injury (the EARLYARF trial) Kidney Int. 2010;77:1020–1030. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi K, Negishi K, Ishizu T, Katagiri D, Fujita T, Matsubara T, Yahagi N, Sugaya T, Noiri E. Evaluation of new acute kidney injury biomarkers in a mixed intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2464–2469. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318225761a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz DN, de Cal M, Garzotto F, Perazella MA, Lentini P, Corradi V, Piccinni P, Ronco C. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is an early biomarker for acute kidney injury in an adult ICU population. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:444–451. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1711-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantin JM, Futier E, Perbet S, Roszyk L, Lautrette A, Gillart T, Guerin R, Jabaudon M, Souweine B, Bazin JE, Sapin V. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is an early marker of acute kidney injury in adult critically ill patients: a prospective study. J Crit Care. 2010;25:176. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martensson J, Bell M, Oldner A, Xu S, Venge P, Martling CR. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in adult septic patients with and without acute kidney injury. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1333–1340. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger J, Kirsch T, Schiffer E, Ulger P, Mentes E, Brand K, Weissinger EM, Haubitz M, Mischak H, Herget-Rosenthal S. Urinary excretion of twenty peptides forms an early and accurate diagnostic pattern of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2010;78:1252–1262. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siew ED, Ware LB, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Moons KG, Wickersham N, Bossert F, Ikizler TA. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin moderately predicts acute kidney injury in critically ill adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1823–1832. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris K, Markou N, Evodia E, Dimopoulou E, Drakopoulos I, Ntetsika K, Rizos D, Baltopoulos G, Haliassos A. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as an early marker of acute kidney injury in critically ill multiple trauma patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2009;47:79–82. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2009.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkoris S, Ioannidou S, Parisi M, Avrami K, Tripodaki E, Douka E, Pipili C, Kitsou M, Zervakis D, Nanas S. Early detection of acute kidney injury by novel biomarkers in ICU patients. A prospective follow up study. Intensive Care Med. 2011;ESICM Annual Congress supplement 1:S238. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Selection, Quality Assessment & Data Extraction Form.