Abstract

Most social research on ageing in Asia has focused on the support provided by adult children to their parents, and thereby suggests that as a matter of course older people are in need of support. This paper offers a different perspective. Drawing on ethnographic and quantitative data from a village in East Java, it examines the extent of older people’s dependence on others and highlights the material and practical contributions that they make to their families. It is shown that only a minority of older people are reliant on children or grandchildren for their daily survival. In the majority of cases, the net flow of inter-generational support is either downwards – from old to young – or balanced. Far from merely assisting with childcare and domestic tasks, older people are often the economic pillars of multi-generational families. Pension and agricultural incomes serve to secure the livelihoods of whole family networks, and the accumulated wealth of older parents is crucial for launching children into economic independence and underwriting their risks. Parental generosity does not generally elicit commensurate reciprocal support when it is needed, leaving many people vulnerable towards the end of their lives.

Keywords: family support, inter-generational relations, Asia, dependency, pensions, grandparents, reciprocity, ethnography

Introduction

Although occasionally hailed as a sign of human progress, population ageing is predominantly portrayed as a challenge, if not an outright problem, to families and societies. This view is reflected in the use of dependency ratios as a measure of ‘elderly burden’ on the productive population (Anwar 1997), and rests on generalisations about older people as not working, as disproportionately consuming health and social care, and therefore as a net drain on younger generations (Treas and Logue 1986: 658 ff.; World Bank 1994). The study of population ageing thus often becomes the study of how societies deal with a growing proportion of old-age ‘dependants’. In developing countries, research has tended to focus on support provided by adult children. Given the absence or insufficiency of state support in most of these countries, assistance from children is presumed crucial to the welfare of older people. Rural areas of Asia, for example, are characterised by an ‘absence of alternative systems of old-age support, by well-developed social norms that underpin family-based support systems, and by the dominance of the family among institutions and the ability of families to inculcate altruism and to enforce social norms’ (Bhaumik and Nugent 2000: 256).

In the face of widespread and rapid social and economic change in Asia, interest in the role of children for old-age support has intensified. As one analyst has remarked, ‘a considerable impetus to the growth of aging research in East and Southeast Asia ... stems from concerns that the rapid social changes occurring on many fronts may place in jeopardy existing social welfare and familial arrangements for the elderly’ (Hermalin 2003: 123). Concern about the reliability and resilience of family support systems sparked numerous studies in the late 1980s and 1990s which anxiously monitored living arrangements and family sizes as potential indicators of older people’s growing imperilment (e.g. Chen and Jones 1989; Hashimoto 1991; Knodel and Debavalya 1997; Martin 1989). In the process, arguably the questions of whether, to what extent, or under what circumstances older people need support, have often been ignored.

More recently, leading demographers of ageing in Asia have started to voice doubts about some of the dominant assumptions and approaches in the field. For example, it has been noted that living arrangements are inadequate indicators of the welfare of, or support for, older people, and that it is necessary to investigate actual exchanges within and beyond households (e.g. Hermalin 2003; Knodel and Saengtienchai 1999; Kreager 2001; Natividad and Cruz 1997). In addition, there has been a growing appreciation of the role of older people as providers of support in their families and communities (e.g. Andrews and Hennink 1992; Biddlecom, Chayovan and Ofstedal 2003; Chan 1996; Hermalin, Roan and Perez 1998).

The aim of this paper is to add to the growing evidence for the contributions older people in Asia make to their families by addressing the following questions. Are older people dependent? How common is old-age dependency when compared with the size of the actively supportive or independent older population? What kinds of support do older parents provide? In the first part of the paper, the question of old-age dependence is dealt with, and an estimate made of the relative importance of being dependent versus having dependants. Then three scenarios in which older people provide far-reaching support to following-generation family members are examined. Although older people are embedded in kinship networks with siblings, nephews, nieces and other relatives, the focus will be on exchanges with children and grandchildren. Older people in rural Java often maintain full parenting responsibilities for young children and grandchildren; some are the main breadwinners in multi-generational families even after children have grown up; and they provide crucial practical and financial support for younger relatives at times of crisis.

Research location and methodology

Indonesia is a suitable setting for a study of the role of older people in family support systems. On the one hand, the population is ageing rapidly, and there are as yet few formal provisions for older people in terms of financial support, health care or institutional care (Asher 1998; Hugo 2000; Ramesh 2000; Tambunan and Purwoko 2002). This implies a dominant role for families in old-age support provision. On the other hand, many family systems in Indonesia are not traditionally extended, but rather nuclear with bilateral kinship reckoning (Geertz 1961; Niehof 1995). Migration and divorce are common (Hetler 1990; Jones 1994; Tirtosudarmo and Meyer 1993). As a result, most older people do not live in multi-generational households. Nor do families generally operate as larger economic units of production from which older parents can benefit after ‘retirement’ (Jay 1969; Saptari 2000; Wolf 1992). In addition, the recent economic crisis in Indonesia has put severe strains on labour markets and household economies (Hill 1999). Many migrants have lost their jobs in the urban economy and have returned to the villages where the rural labour markets, which were under strain before the crisis, have been unable to absorb them. As a result, many young people depend on their families (Breman 2001).

The research reported in this paper is part of a continuing project on ageing in Indonesia that has focused on three rural communities in East Java, West Java and West Sumatra (Kreager 2001; Schröder-Butterfill 2002). The findings presented here are from a East Javanese village, pseudonymously Kidul, where the author conducted fieldwork over 12 months during two visits in 1999-2000 (subsequently there have been two brief returns). Although individual village studies are never ‘representative’, they illustrate general trends in comparable communities. The village was selected to reflect an increasingly common Indonesian situation: the villagers are involved in modern and traditional, and in formal and informal economic sectors (see also Breman and Wiradi 2002; Koning 1997; White and Wiradi 1989). Because Kidul is near regional urban centres, its economy is highly diversified, and agriculture is no longer dominant. Trade, factory, construction, transport and civil service employment all play important roles. Approximately 10 per cent of the population are aged 60 or more years, slightly more than the national average of eight per cent (Ananta, Anwar and Suzenti 1997).

The field research combined ethnographic and demographic methods. Initially all 212 villagers aged 60 or more years were identified, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with 206 (a few were unavailable or refused). These first interviews gathered information on life and marital history, the availability of children and other kin, health, work and daily activities, and the support given and received. Factual data from these and subsequent interviews were entered into a database, and the qualitative comments were sorted by topics and analysed. Most respondents (74%) were revisited at least once, and more than a quarter were interviewed four or more times. The criteria for re-interviewing were not formal, but the aim was to obtain detailed information for subgroups of the older population differentiated by economic strata, the availability of children, and their living and support arrangements. The follow-up interviews produced in-depth data on these topics and pursued such themes as normative inter-generational relations, changes in village life, and the rise and fall of particular families. For a core of 30 respondents, bilateral kinship diagrams were assembled and used to ask in-depth questions about the family history and support flows over the lifecourse. These form the basis for detailed case studies. By living in the village, the author was able to observe older people’s activities and interactions and thereby to gain additional perspectives on what she was being told.

Although older people were the primary target population, interviews were also conducted with younger adults. For more than half of all older people at least one other family member – usually a child or adult grandchild – was interviewed and sometimes all the local members of an extended kin network were spoken to.1 These interviews pursued themes such as support given and received; the motivations for or constraints against providing assistance; and expectations and preferences in inter-generational relations. Their aim was to obtain both additional data and alternative viewpoints, and to cross-check the information given by the older people. In most cases there was good agreement. For example, there were 12 cases in which survey information on inter-household exchanges was available from both the parent and an adult child. In three cases, there was perfect agreement on the existence and frequency of monetary support, in six there was good agreement (both parties agreed on the direction of flows, but gave differing accounts of intensity), and in only three cases was there outright disagreement (one party reported the existence of flows that the other party denied). Moreover, respondents from both generations were as likely to exaggerate the support they gave (or received) as they were to under-estimate.

Towards the end of the fieldwork, two randomised surveys were conducted in the village. One examined 67 older people’s health, health-care utilisation and care in illness; the other asked 55 households with and 51 households without an older person questions about household economy (assets, income, consumption, the distribution of economic and practical responsibilities) and inter-household support exchanges (both routine and large one-off transfers). This paper draws primarily on the qualitative and quantitative data from the semi-structured and in-depth interviews, and uses survey data as an additional source.

The population of older people in Kidul may briefly be characterised. Of the 206 people aged 60 or more years, just over one-third (36%) were men, one-half were aged less than 70 years of age, and one-fifth were 75 or more years. The villagers could be divided into four broad socio-economic strata on the basis of their assets, housing quality, work, income and consumption (for details on the categorisation, see Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill 2003). The majority of households with an older person fell into the middle two groups: 28 per cent were ‘comfortably off’ and 30 per cent ‘getting by’. The remainder were divided equally among the ‘rich’ (20%) and the ‘poor’ (22%).

Are older Indonesians dependent?

Older people’s need for material or practical support and the degree of their dependence on their families can be investigated in several ways. If most older people work and are in good health, their dependency is likely to be low and their potential for making contributions correspondingly high. In addition, if younger family members are non-existent or distant, then older people may have no other choices but to remain self-sufficient or suffer declining welfare. Once information on older people’s needs and abilities, their family context and actual support arrangements is combined, an assessment can be made of whether older people are on balance a drain upon or an asset to their families.

Older people’s need for support

The need for physical or instrumental care arguably represents the most extreme form of dependence in old age, but only arises if an older person is ill, frail or handicapped. The demand for occasional practical assistance is likely to be more widespread and is normally compatible with residential and economic independence. The data on current health problems and impairments are summarised in Table 1. More than half of the older people were in good health: among those aged less than 70 years, the fraction was two-thirds. These people were able to carry out even strenuous activities of daily living, like walking five kilometres, carrying a heavy load, or gardening. One-third were in fair health, which means that their daily routines were affected by ailments but their independence was insignificantly circumscribed. This group included people with diabetes, asthma or long-term blindness (where coping strategies had been developed). Only 21 (10%) were classed as being in poor health and with significantly impeded functional independence. Four older people in Kidul were bedridden, 14 had medium to severe mobility impairments, and three were blind. It is these older people who required practical assistance with the activities of daily living, like procuring food or washing clothes, and some needed physical care of varying intensities. Other studies of older people in Indonesia have found comparatively low levels of poor health (Adlakha and Rudolph 1994; Chen and Jones 1989; Keasberry 2001; Rudkin 1994).

Table 1.

Health status of older people by age group

| 60-69 | 70 and over | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good | 66.3 | 48.5 | 57.6 |

| Fair | 26.9 | 37.4 | 32.0 |

| Poor | 6.7 | 14.1 | 10.3 |

| Total (N) | 104 | 99 | 203 |

Source: Interview data 1999-2000.

Notes: ‘Fair’ comprises older people who have health problems that do not significantly impede their independence or activities of daily living (e.g. long-term blindness, slight rheumatism, asthma). ‘Poor’ refers to those who are seriously affected in their ability to live independently (e.g. people who are bed- or wheelchair-bound).

Where physical care was needed, it was not necessarily provided by children. The vast majority (88%) of older men were married, compared with one-quarter of older women. This differential was reflected in care patterns: of the nine frail men, six were entirely cared for by their wives and two by their wives and daughters (cf. Chen and Jones 1989: 87). By contrast, six of the 12 women in poor health were looked after by children, two by husbands and children or grandchildren, two by relatives other than children, and two by neighbours. Care by a spouse was considered most acceptable by the older person, followed by care by a daughter. It is also important to bear in mind that many older people experience no period of physical dependence before they die. Of the 27 older respondents who have died since the research began, 11 died suddenly or after a few days of illness, another seven were ill for a few weeks or months, and nine were seriously ill for more than a year.

The extent to which older people in rural East Java have to rely economically on their families depends on their work status and income. Table 2 summarises the work of the villagers in three broad age groups. People were classed as in regular paid work if they engaged on most days in activities that either generated money income (e.g. an agricultural wage, profit from trade) or sufficient income in kind (usually rice) to allow a surplus to be sold to cover non-food consumption needs.

Table 2.

Work status among adults by age group

| 20-59 | 60-69 | 70 and over | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular paid work | 73.0 | 56.6 | 24.0 |

| Not working, but income from land or pensions[a] | 1.3 | 16.0 | 19.0 |

| Occasional or unpaid productive work[b] | — | 7.5 | 12.0 |

| Unpaid domestic work[c] | 18.0 | 9.4 | 18.0 |

| Not working | 6.5 | 5.7 | 6.0 |

| Unable to work | 1.3 | 4.7 | 21.0 |

| Total (N) | 233 | 106 | 100 |

Sources: Household survey 2000 and interview data 1999-2000.

Notes:

Some individuals in this category undertake paid or domestic work in addition; similarly, a few in paid work also receive a pension.

Refers to people who occasionally work or who grow produce for own consumption.

Refers to women who have major housekeeping responsibilities, either keeping house for their families, or, if living alone, for themselves.

As expected, the proportion engaged in regular paid work declined from almost three-quarters among those aged 20-59 years, through 57 per cent among those aged 60-69 years, to a quarter of those aged 70 and more years (41% for all older people).2 Data on income were collected as part of the household survey. Inevitably, these provide only an approximation, not only because information on income is sensitive, but also because it was difficult for many respondents to ascertain exactly how much they earned, because traders often immediately reinvest profits in stock, because agricultural work is seasonal and sometimes remunerated in kind rather than money, and because farmers with their own land only receive a harvest every few months, the value of which depends on season and climate. On average, the income of older people in regular paid work was Rp 6,730 [£0.56] a day. When comparing incomes with an older person’s average daily consumption need of approximately Rp 2,300 [£0.19], it is found that fewer than 20 per cent of older workers earn less than the minimum needed to satisfy daily needs in the absence of major health crises.3

The majority of those earning less had a spouse who also worked; the remainder were forced to supplement their meagre incomes with charitable donations. In other words, almost all older people who still engaged in regular paid work earned enough to live independently. If we add to this group the older people who had no need to work because they had income from pensions (average income of Rp. 13,000 [£1.08] per day) or agricultural land (average income of Rp. 12,000 [£1] per day), the proportion of older people with independent means was much higher, namely 73 per cent among 60-69 year-olds, just under half (43%) among those aged 70 and more years, and 58 per cent for older people as a whole. Clearly, then, economic dependence is not the statistical norm among older people in rural East Java. This is not to say that many do not also receive some material support from their children, merely that they do not rely on this assistance for their daily survival.

Older people who lived with an adult child or grandchild were less likely to work than those living alone or only with dependants (Table 3). Among the former, 31 per cent were engaged in paid work, compared with 50 per cent among the latter. These differences are not enormous, and the pattern certainly does not indicate that older parents automatically ‘retire’ on their children’s support if they can (for similar evidence, see Cameron and Cobb-Clark 2001). Moreover, once we take into account older people who have incomes from pensions or land, the difference between the two groups diminishes. Then, 64 per cent of older people not living with an adult descendant had adequate independent income, compared with 52 per cent among those living with a grown-up descendant. This raises the important question of what these incomes are for: Why do many older people living with an adult child or grandchild continue to work? How do they use their work or pension incomes? We shall return to these questions when examining the contributions from older people.

Table 3.

Work status of older people by co-residence with an adult descendant

| Not with adult descendant | With adult descendant | |

|---|---|---|

| Regular paid work | 49.5 | 30.9 |

| Not working, but income from land or pensions | 14.7 | 20.6 |

| Occasional or unpaid productive work | 10.1 | 9.3 |

| Unpaid domestic work | 12.8 | 14.4 |

| Not working | 2.8 | 9.3 |

| Unable to work | 10.1 | 15.5 |

| Total | 109 | 97 |

Source: Interview data 1999-2000.

Notes: As in Table 2. An ‘adult descendant’ is defined as a child or grandchild aged 19 and over, or aged 25 and over if still in education. The vast majority of adult descendants were married, widowed or divorced.

Availability of support

The functional and economic independence of most older people in Kidul has been established. What can be said about the availability of support from children, should it be needed? High fertility in developing countries means that an abundance of children has commonly been assumed and indeed has sometimes been seen as explicitly motivated by a concern for support in old age (Cain 1986; Datta and Nugent 1984; Nag, White and Peet 1980). The assumption of the presence of children is problematic for two reasons. The generally high level of fertility hides temporary oscillations as a consequence of economic crises, epidemics and the like, with the implication that certain cohorts may face unfavourable parent-child ratios (Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill 2003). The second problem is that high aggregate fertility hides considerable individual variation in reproductive outcomes (Knodel, Chayovan and Siriboon 1992). The proportion of older people who are childless is therefore an important indicator of the extent to which children can be depended upon for old-age security. The local availability of children is also relevant for sources of practical support and physical care.

Table 4 shows the availability of children to older people in Kidul. Levels of childlessness were remarkably high, for one-quarter had no surviving children and 41 per cent had no or only one child. A third of older people had no child living locally, and more than half had no more than one child in the village. Clearly, not all older people can be classified as dependent, or at least as dependent on offspring. A single village may of course not be representative, but the findings from Kidul are consistent with a wider pattern of sub-optimal fertility in Indonesia. On the basis of the 1971 census, Hull and Tukiran (1976) showed that East Java was particularly affected by childlessness: 17-23 per cent of women aged 30 or more years were childless. The level in Indonesia generally was also high (14-16%). On the basis of World Fertility Survey data, Vaessen (1984) found Indonesia to have the fifth highest national levels of infecundity and childlessness among 28 developing countries. Indonesian Family Life Survey data from 1993 gave lower levels of childlessness, e.g. 7.3 per cent for rural Indonesians aged 60-69 years and 10.6 per cent for those aged 70 and over, but again confirm Hull and Tukiran’s observations of above-average childlessness in East Java. The results of all of these censuses and surveys should in any case be questioned for a likely bias that under-estimates childlessness. The sustained contact that ethnography provides revealed that older people not only failed during first interviews to mention children with whom contact had ceased, but more importantly identified adopted children as own children.4

Table 4.

Percentage of older people by number of children surviving and children in the village

| Number of children | Children surviving | Children in the village |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25.6 | 34.0 |

| 1 | 15.3 | 23.2 |

| 2 | 10.3 | 25.1 |

| 3 | 10.8 | 9.4 |

| 4 | 9.9 | 3.9 |

| 5 | 11.3 | 2.5 |

| 6 or more | 16.8 | 2.0 |

| Total (N) | 203 | 203 |

Source: Interview data 1999-2000.

Unlike the many parts of Asia where extended family systems prevail, in Java there has been a cultural preference for nuclear families since at least the 19th century (Boomgaard 1989; Geertz 1961; Koentjaraningrat 1985; for the Philippines see also Lopez 1991). Adult children are expected to move into an independent household soon after marriage, eventually leaving older parents in an ‘empty nest’. In Kidul this was explained through notions of independence and avoidance. (For fellow Indonesianists, the local terms in Bahasa Indonesia are given, as these best render people’s sentiments.) Parents stated that it was important for young couples to learn to manage their own household. Parents should ideally not interfere (campur tangan), beyond helping children attain residential independence, although the parents’ readiness to help children in need was stressed. Children-in-law explained that they did not feel free (bebas) in their parents-in-law’s presence and that they feared causing offence (tersinggung) or embarrassment (malu) by making them party to marital tiffs. Conversely, older parents were acutely aware of the possibility of becoming a burden (menjadi beban) or troubling their children (merepotkan anak), and many said that they felt awkward (sungkan) about having to ask a child or child-in-law for anything. As one elderly woman agricultural labourer said, ‘parents should work for as long as possible. By working, they need not feel ashamed (malu) towards their children whenever they wish to buy snacks for themselves or their grandchildren’. Most respondents, old and young, agreed that it was best for married family members to live separately, and many of the older respondents confirmed that their own grandparents had not lived with them in the past. Of course there are variations in both stated preferences and actual practice. Especially when there is only one surviving parent or if the parental home is very spacious, it may be deemed preferable for one married child to remain. Poor parents may be unable to help children with setting up an independent home and may transfer formal ownership of the home to a married child who wishes to stay in the village. Overall, childlessness combined with the tendency for nuclear families give rise to comparatively low rates of parent-child co-residence in old age, as may be seen from Table 5.

Table 5.

Living arrangements of older people by age and sex

| Men 60-69 | Men 70 and over | Women 60-69 | Women 70 and over | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living alone | 5.3 | 0 | 5.9 | 21.9 | 9.7 |

| Husband and wife only | 15.8 | 22.2 | 10.3 | 4.7 | 11.7 |

| With young descendant | 39.4 | 19.4 | 23.5 | 4.7 | 19.9 |

| - Child | 36.8 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 0 | 11.2 |

| - Grandchild (skipped) | 2.6 | 11.1 | 14.7 | 4.7 | 8.7 |

| With adult descendant | 31.6 | 52.7 | 53.0 | 57.8 | 50.5 |

| - Child | 26.3 | 44.4 | 51.5 | 48.4 | 44.7 |

| - Grandchild (skipped) | 5.3 | 8.3 | 1.5 | 9.4 | 5.8 |

| Other arrangements | 7.9 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 10.9 | 8.3 |

| Total (N) | 38 | 36 | 68 | 64 | 206 |

Source: Interview data 1999-2000.

Notes: As in Table 3. In skipped generation households the middle generation is missing.

One-in-ten older people live on their own. For older women the proportion increases steeply with age (22% among women aged 70 and more years), and for men there is a decline to zero in the older age group. Another 12 per cent live just with a spouse and eight per cent with non-relatives or relatives other than children or grandchildren. In other words, almost one-in-three older people do not live with a child or grandchild. Although material and functional independence is not necessarily implied, it is unlikely that most of these older people are reliant on offspring for day-to-day survival. Almost 30 per cent of older people who do reside with a descendant live with an unmarried child or young grandchild, and only one-in-two older people live with an adult descendant (Table 5).5 The conventional interpretation in Asian ageing research is that they are the most secure older people, because they benefit from the support of co-resident working-age family members (Cameron 2000: 20; Domingo and Casterline 1992; Keasberry 2001; Knodel and Debavalya 1997; Ofstedal, Knodel and Chayovan 1999). Whether this is true in rural Java is investigated below.

Dependent or depended upon?

I began by asking whether older people in East Java were dependent on their families. Evidence of older people’s health, income status, the availability of children and their living arrangements all points to considerable heterogeneity in their situations and support, but certainly allows us to reject the notion of general or even widespread dependence. Only half of all older people live with a mature descendant, a mere 10 per cent are physically in need of care, and the majority have enough income to live respectably without support from children or other sources, although additional help may of course be forthcoming.

These data do not reveal the overall dependency status of individual older people or the positive support they provide to their families, but information about each older person can be aggregated into a summary measure which captures the inter-generational support flows. Each individual may be associated with a ‘downward’ – from older people to the young, an ‘upward’ – from young to old, or a ‘balanced’ exchange. Ascribing an older person to one of these outcomes requires examination of the flow of family support within and beyond the household. Here we are only interested in material (money, food, medication) and practical (physical care, childcare, domestic work) support flowing between older parents, their children and grandchildren. The ascription was based on older people’s work, income and ownership of productive assets; their daily activities and responsibilities; the division of labour and distribution of income in households; and the exchanges among co-resident and non-co-resident family members of routine material and practical support and the less frequent recent occurrences of substantial assistance (e.g. payment of a hospital bill, providing business capital). The data derive from the semi-structured and in-depth interviews and where possible have been cross-referenced with information from the interviews with family members and survey returns.

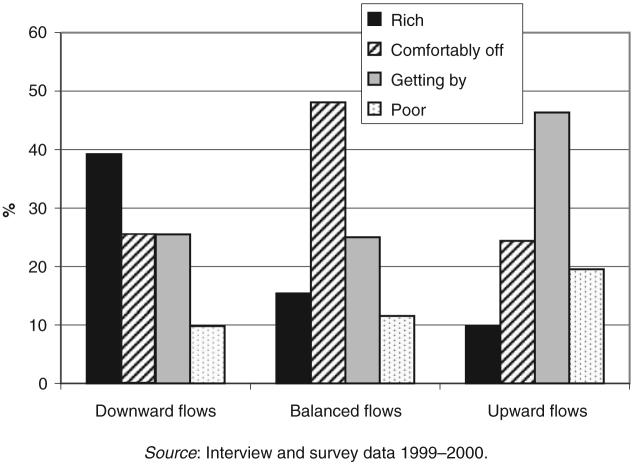

Figure 1 summarises the quantitative importance of the various inter-generational support flow types in East Java. Older people without children are set aside: their support arrangements have been detailed elsewhere (Schröder-Butterfill 2004). Among older parents five outcomes are distinguished, two being variations of older people as net givers of inter-generational support, one to unmarried children or young grandchildren, the other to adult children or grandchildren. In these categories, the support was above all material, although practical assistance was also involved, e.g. caring for a young grandchild. Some return flows of support occurred, but were far short of offsetting the older generation’s contributions.

Figure 1.

Frequency of intergenerational support flow types involving older people.

The third group consisted of arrangements in which the generations were mutually inter-dependent or largely independent of each other. They were exceptionally heterogeneous and included cases where the generations engaged merely in occasional exchanges of gifts or services and others of intense but roughly balanced exchanges (see Schröder-Butterfill 2002: 202 ff.). The fourth category comprised all cases of upward net flows, from children or grandchildren to parents or grandparents. It included older people who were physically dependent as well as those who had no income and were unable to offset their material dependence by offering services in exchange. Finally, there was a small group of older parents who neither gave nor received any inter-generational support: they arguably were the most vulnerable older people in Kidul.6

Some provisos should be noted. First, although efforts were made to corroborate the information from the older respondents by interviewing children or grandchildren and by gathering observational data, in some cases the assessment was solely on the basis of the older respondent’s account. There may be some cases of exaggerated independence or downward support, although equally some interviewees may have been reluctant to admit to their children’s neglect. Secondly, the data refer to support arrangements at a certain time, when of course old age is full of transitions, and the needs for, and families’ ability to provide, inter-generational support changes over time. Thirdly, the typology has unrealistic neatness. Older people may routinely provide for dependent offspring but receive infrequent support in return; or they may anticipate the delegation of responsibility in the near future. Despite these limitations, the utility of the typology is that it provides a rough summary measure which reveals the variety of old-age living and inter-generational support arrangements and flows.

One-quarter of older people in Kidul were childless, and only one-in-five were largely or entirely dependent on their families (Figure 1 and Table 4). One-in-four were independent or in arrangements of mutual benefit to the generations. Finally, one-quarter – or one-third of older parents – were net providers of inter-generational support, and of these almost half (44%) were supporting adult as opposed to young dependants.

The different support flow types can be characterised briefly (Table 6). Older people who were net recipients of support from their children or grandchildren tended to be aged 70 or more years, female and widowed. Only one-third had good health, and very few had income from work, land or pensions. Reliance on the family came at the price of relinquishing control over assets. This pattern reflected the villagers’ views that dependence in old age should be avoided until inevitable: those parents suspected of unnecessarily or unreasonably relying on support from adult children or grandchildren were the subject of critical gossip. Older people in arrangements that reflected independence or generational inter-dependence of generations were harder to characterise. Half worked, half did not; and most were women in good health, widowed and still in control of bequeathable wealth. As would be expected, many lived separately from their children and grandchildren. Finally, the older people who were net providers tended to be healthy, aged less than 75 years, married, with income and still held the reins of economic control.

Table 6.

Older people’s characteristics by intergenerational support flow types

| Downward flows | Balanced flows | Upward flows | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: 70 and over | 29.4 | 46.2 | 70.7 |

| Gender: female | 39.2 | 67.3 | 85.4 |

| Marital status: married | 74.4 | 31.9 | 20.5 |

| Health status: good | 78.4 | 63.5 | 35.0 |

| Health status: poor | 3.9 | 3.8 | 17.5 |

| Work: in paid work | 56.9 | 46.2 | 12.2 |

| Income from land or pension | 60.8 | 42.3 | 7.3 |

| Inheritance: all handed over | 15.2 | 33.3 | 69.0 |

| Live alone or just with spouse | 0 | 30.8 | 9.7 |

| Total (N) | 51 | 52 | 41 |

Source: Interview and survey data 1999-2000.

Note: Childless older people are excluded, as are those engaged in no flows of inter-generational support at all.

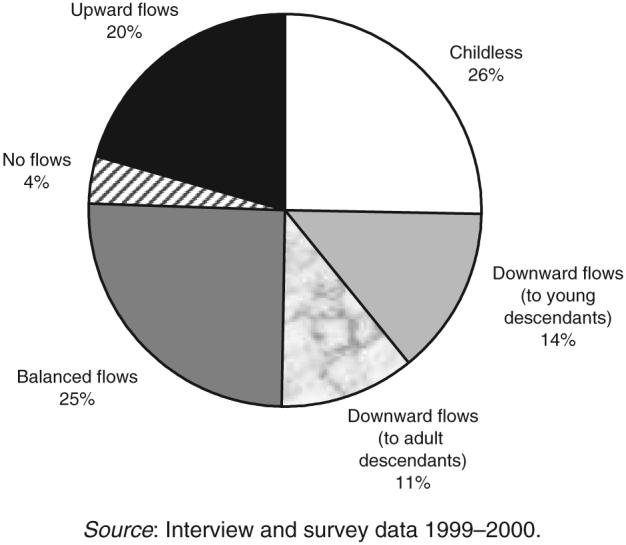

The economic underpinnings of the three main support flow types are portrayed in Figure 2. The different inter-generational outcomes map remarkably well onto the four economic strata in the village. Arrangements where net flows of support are downward are dominated by well-off older people: being rich (kaya) entailed responsibilities for children and grandchildren. That said, 10 per cent of the ‘downward’ arrangements involved poor (kurang mampu) households and 26 per cent were merely getting by (cukup-cukupan); there are obvious deleterious welfare consequences for the older people in these households. Older parents who depended on upward flows of inter-generational support tended to be in households that were getting by (although one-third were rich or comfortably off). These parents’ inability to make material contributions may have reinforced their families’ relative poverty, and this in turn may have meant that support was limited. The predominance of comfortably off (lumayan) older people in arrangements where flows of support were balanced is not surprising: these parents were wealthy enough to be independent, but not so rich as to attract many dependants. Where they lived with children, their households were likely to benefit from multiple incomes or co-operation between the generations.

Figure 2.

Inter-generational support flow types by older people’s economic status.

Family support provided by older people

As just seen, many older people in rural East Java are net providers of support. Yet how are we to imagine the assistance they give to their families? Research into the supportive role of older people in Asia is still sparse and has focused on their indirect contributions, namely, assistance with childcare or housework which enables younger adults to devote themselves to other productive or reproductive tasks (Andrews et al. 1986; Chan 1997; DaVanzo and Chan 1994; Domingo et al. 1995; Hermalin, Roan and Perez 1998). In rural Java, many older parents’ and grandparents’ contributions were far-reaching: they maintained full parenting responsibilities well into old age; they represented the economic backbone of multi-generational families; they stepped in during crises among the younger generation and supplemented meagre household incomes by continuing to work. The diversity of the assistance they provided will be illustrated further through case studies.

Parenting in old age

As seen, one-in-ten older people lived with children who were not yet married and mostly aged in the late teens or early twenties. It is therefore reasonable to presume that they would be making contributions to the households they lived in, rather than requiring support from their parents. Previous reports have noted the important economic contributions made by Javanese children. For example, Nag, White and Peet (1980) found that among 12-14 year-olds during the early 1970s, boys contributed 4.7 and girls 7.3 hours of work to their households, which represented 42 and 59 per cent, respectively, of the average adult’s input (see also Geertz 1961; Hart 1980). In Kidul at the end of the 1990s, the reality was different. Some 61 per cent of 15-19 year-olds were still in education, and only nine per cent of 15-19 year-olds were in paid work. Beyond primary school, parents have to pay fees for their children, and in secondary school these can be considerable. Except in very poor households, parents did not expect unmarried working children to contribute to the household income. Instead, it was deemed normal that youngsters spend their money on clothes, entertainment or consumer durables, or that they should save for marriage. All of the surveyed 15-19 year-olds who were working kept their income to themselves, and among the 48 per cent of 20-24 year-olds who worked, 83 per cent did so. Children do, however, occasionally buy generous gifts for their parents or siblings, or contribute money in a crisis (cf. Koning 1997; Wolf 1992). No evidence was found that teenage children were expected to make significant practical contributions to the household. In short, in all the households in which older parents lived with young or single children, the dominant flow of inter-generational support was from parents to children (see also Knodel, Chayovan and Siriboon 1995: 442). Far from being a source of support, unmarried children generally represented a net economic drain on the older parents’ resources.

Older people not only supported their own unmarried children but also assumed parenting responsibilities for grandchildren. In East Java, co-residence with a young grandchild whose parents are absent is almost as common as co-residence with an unmarried child (Table 5). Nine per cent of older people in Kidul found themselves in such ‘skipped-generation’ households. In about one-third of these households, the older generation had permanently taken on the parental role because the grandchild’s parents had died or relinquished parental responsibilities for other reasons (such as divorce and remarriage). In the second arrangement, the grandparents were temporarily caring for the grandchildren to allow the middle generation to be labour migrants. Other aspects of the domestic economy of a skipped-generation household are revealed in the following case example.

Case Study 1: Pak Abdul and Bu Rohana7

Pak Abdul is a comfortably-off village official and farmer aged in the sixties. His wife, Bu Rohana, made and sold cakes. When they were first interviewed, they were living with an unmarried son, a married daughter, the daughter’s husband and their nine-year-old son, Alfi. A week later, the daughter tragically died in an accident, thrusting the parents into despair. They had hoped that their only daughter would be close-by as they grew older. What eventually made the grieving parents take charge of their lives again was the new-found responsibility for Alfi, their grandson. Rohana took on the mother’s role, and Abdul started to pay his grandson’s school fees and pocket money. Over several months, the son-in-law who still lived with them became increasingly detached, often spending the night in the nearby town where he worked. His contributions to the upkeep of his son became irregular. When I tentatively asked Rohana what would happen should he remarry, her response was unequivocal: ‘He may do as he pleases, stay or leave, but under no circumstances may he take Alfi with him! Alfi will now remain with us and will inherit his dead mother’s share’.

Most grandparents gladly assume the role of surrogate parent in the event of a family crisis; indeed, having a grandchild to look after may provide some consolation in the face of a loss. In these cases, it is common for grandparents to refer to their grandchild as anak angkat (adopted child) and to include him or her in the inheritance. Of course, unlike dependent children who have grown up by the time their parents reach their seventies, grandchildren may continue to depend on the grandparents’ economic and practical support well into the latter’s old age. Abdul, for example, will be in his seventies by the time Alfi reaches secondary school: he may then have to sell agricultural land to cover the costs of his grandson’s education. In many parts of Southeast Asia, the role of grandparents as surrogate parents is likely to grow in the coming decades, not least because the spread of HIV-AIDS (still largely denied in Indonesia) will create an increasing number of orphaned children (cf. Knodel et al. 2001; World Health Organisation 2002).

A different logic underlies the second skipped-generation arrangement in which grandparents are temporarily, though often indefinitely, responsible for a grandchild. Some authors have described such arrangements as ‘family strategies’ or ‘corporate group models’, in which the members co-operate to maximise economic or other opportunities (see Bledsoe and Isiugo-Abanihe 1989; Lee 2000; Peterson 1993; Richter 1996). The middle generation raises income and living standards, and the older generation benefits from companionship and remittances. In Java, however, the notion of a family strategy is problematic, as older parents do not perceive the option to refuse, nor do they usually benefit materially from the arrangement. Indeed, it is wholly inappropriate to model Javanese multi-generational families as ‘firms’ pursuing a common economic enterprise, as might apply to the Chinese chia or the Japanese ie family. Javanese villagers are economically individualistic: property is owned individually, family members rarely co-operate economically, and not even all spouses pool incomes.

There was little evidence that skipped-generation households stimulated remittances from absent parents (contrast Rudkin 1998). Fewer than two-thirds of older people with co-resident dependent grandchildren reported receiving any form of financial support. In all but two cases, the sums remitted were insufficient to cover the expenditure on the child and had to be supplemented, if not entirely paid for, by the grandparents. Insofar as fostering by grandparents is a strategy, it is one for the middle generation who benefits from free childcare and greater mobility. Many grandparents are significantly worse off as a result of the service they provide, as Mbah Juminah’s case shows.

Case Study 2. Mbah Juminah

Mbah Juminah is a widow aged in her seventies. From an upper-class central Javanese family, she was married to a member of the Indonesian army. Since her husband’s death, Juminah has received a modest pension (Rp. 356,000 [£30] per month). A few years ago she tried unsuccessfully to set up a business but was left with debts and was forced to sell her nice house. At the time of her interview, Juminah lived in a run-down rented house which she shared with her divorced son and three grandchildren aged between four and 17 years. One granddaughter is the daughter of the co-resident son whose wife left him soon after the child’s birth. The younger two are children of another son who worked and lived in the nearby district capital; his wife worked in Malaysia. Juminah not only cared for her three grandchildren, she was also largely financially responsible for them. Her co-resident son did not contribute his income and left his mother to pay for his daughter’s food and school fees. He provided only pocket and bus money. Similarly, the non-resident son, who visited his mother and children once a week, contributed a sum which did not cover one daughter’s schooling. Not surprisingly, life was hard for Juminah. To generate a little extra income, she grew mushrooms in the kitchen of her crowded and damp house. Help from other family members was not forthcoming. Indeed, she awaited repayment of a large loan to another of her children several years before. Without her dependants, Juminah would have been comfortably-off, but as it was, she was struggling to make ends meet. In such an arrangement, the imbalance in the family members’ exchanges created feelings of exploitation and resentment. Not only did Juminah have to make material and practical sacrifices, she had no guarantee that her grandchildren would remain loyal towards her once their mother had returned from Malaysia. Unlike Pak Abdul’s case, it was not a long-term arrangement.

To summarise, it was found that one-in-five people aged 60 and more years in Kidul lived with a dependent descendant. In the vast majority of cases, their responsibility involved not just practical care but also economic support. Whilst the dependency burden from unmarried children decreased with parental age, surrogate parenthood of grandchildren showed no appreciable decline with age. Parenting thus represented an important type of support that was provided by older people of all ages.

Pensions and land: the older generation as economic backbone

What is the role of older parents once their children are fully adult? Far from their assistance being confined to practical tasks, like child care or housework, many older parents continued to provide material help. Although many offspring who lived nearby received routine support from their older parents, the following account focuses on support to co-resident adult children or grandchildren. It has been mentioned that older people’s support to adult family members has been largely neglected in previous research and, in particular, that few studies have examined the flows of support within households (for exceptions see Beard and Kunharibowo 2001; Chan 1997; Chye 2000; Hermalin, Roan and Perez 1998; Li 1989). One reason is that most surveys have taken households as the unit of analysis (for reviews see Andrews 1992; Andrews and Hermalin 2000; for a critique see Knodel and Saengtienchai 1999). Information on the exchanges within households is sensitive and difficult to collect (Natividad and Cruz 1997: 29). There has also been a tradition of treating families as guided by an altruistic head who maximises the collective welfare, and this has led researchers to assume income-pooling and equitable access to resources among the members (e.g. Becker 1981; but contrast Folbre 1997; Pezzin and Schone 1997; Sen 1989). This assumption, when combined with notions of older people’s dependence, has tempted researchers on ageing to equate co-residence with support for the older generation (e.g. Cameron 2000; Martin 1989). In other words, co-residence is widely taken to imply net upward flows of inter-generational support, while certain reciprocal downward flows are acknowledged. In reality, however, co-residence tells us little about the actual flows of support within a household. As Hermalin (2003: 121) observed,

a formal structural definition of living arrangements fails to provide vital information about the content of the relationships and interactions. For example, older parents living with married children may be recipients of considerable financial and emotional support, or they may be mainly aiding their children and grandchildren with child care, shopping, and meal preparation. ... [C]urrent and future research should devote greater attention to distinguishing the forms of living arrangements from the actual functions they serve, and not try to infer the content from the structure.

To understand the impact on older people’s circumstances of various living arrangements, the following questions need to be answered: Who are the main and secondary sources of economic support? To what extent are goods shared? What entitlements do various family members have to material and practical resources? How are responsibilities for housekeeping tasks distributed? It has been shown that in one-quarter of two- or three-generation households, the senior generation represents the economic backbone. The following case study exemplifies the dynamics of the exchanges.

Case Study 3. Mbah Winar and Mbah Jin

Mbah Winar and Mbah Jin are a couple aged in the seventies. As a former member of the Indonesian army, Winar received a regular monthly pension (Rp. 470,000 [£39]). The couple had not had children together, but Jin had a daughter from a previous marriage whom Winar considered as his own. One of the daughter’s children, Tommy, had been raised and educated by his grandparents. Some years before the interview, the couple moved to Kidul, leaving behind their daughter with whom relations were not particularly warm. Their decision depended on Tommy’s willingness to move with them, and the house they had built in Kidul was subsequently put into the grandson’s name. When Tommy married, his wife joined the household and they had a child. Tommy’s wife did most of the housework and was expected to care for the older couple should they fall ill. Economic responsibility rested with the senior generation. All the money for daily shopping, utilities and treats for the great-grandchild came from Winar’s pension. Tommy only worked irregularly, and when he did, he contributed a little money for the shopping but spent most on modern consumer goods.

In this example, the older couple were the main source of income for a family of five. The arrangement was long-term. Despite the economic imbalance, the situation was harmonious as the grandparents had companionship and practical support: it exemplifies the ‘independence or inter-dependence of generations’ household type. Indeed, the arrangement was contrived by Winar and his wife as a response to their perceived vulnerability in old age if they relied on an unco-operative daughter. Thanks to the large pension, their financial security was not at issue: the concern was about the source of reliable support should it be needed.

Close examination of older people who are net providers of material support to children or grandchildren, like Winar, reveals that most belonged to the wealthier strata in the village (Figure 2). Unsurprisingly, those older people who received a monthly pension or regular income from agricultural land were the most likely to have dependants. Of those who were net providers of inter-generational support, 39 per cent were pensioners, and 61 per cent were pensioners or landowners. By contrast, the comparable figures for older parents who were dependent on the young were five and seven per cent.8

Research in other developing countries has investigated the role of pension incomes in wider family networks. Francie Lund (2002), for example, found that non-contributory pensions to poor older people in South Africa raised the standard of living and provided security for entire households (see also Barrientos and Lloyd-Sherlock 2002; Case and Deaton 1998; HelpAge International 2003). The reliability of pensions means that the income can be used strategically and allows households to obtain credit for which they would otherwise be ineligible. Rather than pensions ‘crowding out’ familial support, as Cox and Jimenez (1990) and Treas and Logue (1986) described, Lund (2002: 682) found diverse and positive subsidiary effects: ‘Some worry about the potential of this public spending [i.e. pensions] to “crowd out” individual savings, and to reduce transfers between generations. A growing body of research shows, on the contrary, that it “crowds in” care, the status of the elderly, the health status of children, the creation of local markets, and micro-enterprise formation’ (1986: 657).

The data from rural Java support the view that pension incomes represent important vehicles for economic redistribution in family networks. Among older people in receipt of a pension, only 30 per cent used the income predominantly for their own needs. In all other cases, larger family units were being shored up, as the household sizes show. Whereas the average household with an older person had 3.75 members, those with a pensioner had 4.4 members; and in the pensioner households where the pensions were shared, there were 4.8 members. Of course there are positive and negative aspects to the dispersal of pension incomes. Younger-generation members enjoy an improvement in living standards and financial security, and for the older person a pension increases the likelihood of living with a child or grandchild (84% versus 72%), which points to greater companionship and potential support. In the case of Winar, at least, the arrangement was seen as mutually beneficial. On the other hand, the dilution of a pension income by a large number of dependants may leave the pensioner with little or no advantage over a non-pensioner peer. To use a crude approximation, at the time of the fieldwork average monthly pensions in Kidul were Rp. 380,000 [£32], which translates into a daily income of Rp. 12,700 [£1.06] for sole beneficiaries. Once divided by the average household size of 4.4 or 4.8, the per capita income is Rp. 2,600-2,900 [£0.22-0.24], little more than the average daily per head expenditure of Rp. 2,300 [£0.19]. Moreover, not all older net providers of support were wealthy, for roughly one-third were merely getting by or even poor. Nor does older people’s far-reaching economic support for adult offspring necessarily reflect a positive choice. Some parents saw themselves as forced to provide indefinitely for handicapped or incompetent offspring; others had to step in periodically to provide assistance in a crisis. It is to such support that we shall now turn.

Case Study 4: Mbah Hari and Bu Ratna

At the time of the fieldwork, Mbah Hari was aged in the seventies and his wife, Ratna, was a few years younger. Hari used to work as a school clerk and drew a small government pension (Rp. 350,000 [£29] per month). The couple had no productive assets, and their house was modestly furnished. Hari and Ratna had seven surviving children, but four had moved away. One never-married son aged in the forties and a married daughter, Lany, with her three small children lived with Hari. Lany had moved out when she married but had returned when the marriage failed. Later she had moved to Jakarta with her second husband, where he worked in a hotel. Seeing living costs spiral in the capital, the young family had moved back to East Java in 1998. Because of the bad economic conditions following the collapse of the ‘New Order’ regime, they didn’t find work and moved in with Lany’s parents. Consequently, Hari’s pension, which would have comfortably covered the older couple’s needs, had to support a family of eight. As Hari put it, his pension was the pillar (tumpuan) of the family. Ratna, although in her late sixties, took on occasional work as a domestic help for neighbours – a decision that harmed her reputation. As she explained, ‘When the grandchildren ask for treats or need medicine, how can I disappoint them?’ By the time of the second field visit, Lany had left for Malaysia to find work, and the son-in-law had returned to his village. The three small grandchildren were being looked after fully by Hari and Ratna. The strains of this responsibility were etched on their faces. This, they complained, was not how they had imagined ‘retirement’.

Hari and Ratna’s situation illustrates the key role that some older people play in underwriting the risks that young people face in an uncertain economy. Lifecourse transitions are not necessarily linear and irreversible, and parent-child livelihoods may remain critically inter-dependent even after children marry and leave home. Thus, although Lany twice gained residential and economic independence, crises forced her to return to her parents’ home. In Java, where divorce and adult mortality have traditionally been high, temporary and permanent crisis reincorporation of adult children into parental households has long been an element of the inter-generational support system. One-in-ten older people in Kidul, for example, lived with a divorced or widowed child. We encountered examples of older people returning to work to help pay debts in the younger generation; of family homes being sold by older parents to pay for offspring’s hospitalisation; and of grandchildren being incorporated into grandparental households to reduce the burden on parents who had lost jobs. In smaller ways, even where adult children were economically active, older parents’ incomes provided a financial cushion, as for health care or expensive life-cycle rituals (slametan).

Crisis assistance, like routine economic support, may put pressure on the older generation. In Hari’s case, the elderly couple were economically and physically significantly worse off as a result of their daughter and son-in-law’s failure to maintain their independence. Far from deriving satisfaction from playing an important role in their grandchildren’s lives, the couple felt over-burdened by the responsibilities and also had to bear the stigma of being pitied by their neighbours for their daughter’s misfortune. The final case study is a particularly tragic example of a widow’s economicand social decline as a result of her efforts over two decades to bail her relatives out of crises.

Case Study 5: Mbah Sum

When Mbah Sum was first interviewed, she was a widow aged in the eighties. She lived in a nice brick-built house with her widowed daughter (aged in the sixties), her married granddaughter Diana, a great-granddaughter and two small great-great-grandchildren. Three younger sisters lived close-by. Sum no longer worked but helped with housework and child-minding. Yet by the time we left 10 months later, Sum was living just with her daughter in a tiny windowless bamboo shack. What had caused this dramatic decline?

Sum came from a respectable village foundation family and had made three good marriages. She had only one surviving daughter. With her third husband, a village official, she had acquired considerable wealth in the form of land, but after his death in the late 1970s, Sum came under constant pressure to pass her wealth to the younger generations. Little by little, she sold the land to cover family needs: a great-grandchild was hospitalised, there were costly circumcision and wedding ceremonies, and capital was required to enable the granddaughter to leave for Saudi Arabia and to shore up her daughter’s trade in second-hand clothes. Most unfortunately, she agreed to sell her house cheaply to her granddaughter, Diana, when she returned as a rich woman from the Middle East. Diana improved the house and lived in it with her mother, grandmother and daughter. She also invested in various business schemes, none of which proved viable. By the time Sum was first interviewed, Diana was already in debt, and soon after she was forced to sell the house in which her mother and grandmother lived. With a surplus from the sale, she migrated once again. Sum now spends her dying days in poverty and relies on charity, help from her relatives (mainly her grandson and elderly sisters) and what little her daughter makes. None of these sources is enough to pay for health care.

As this case study shows, the line between crisis and long-term support may be blurred, as repeated crisis interventions for different family members add up to sustained pressure on the parent or grandparent. As is often the case, accumulated wealth is dissipated through the family network, both as ‘seed capital’ and ‘insurance payments’. As a result, despite her comfortable material circumstances when she entered old age, Sum ended up destitute. It is tempting to regard Sum, Hari and Juminah as exceptional – instances of older people who are too generous for their own good. The view that parents’ responsibility towards children is paramount and indefinite was, however, pervasive among villagers of all ages (see also Biddlecom, Chayovan and Ofstedal 2003: 195). It is captured in the saying that parents should never be heartless (nggak tega) towards their children. Parents who cease to bail out adult children in need are criticised by fellow villagers. One man went as far as saying that it was a sin (dosa) for parents to be well-off and not to help their children, and a sin also to hang on to assets in old age rather than pass them on to the younger generation.

Given the social expectations that parents support their descendants in need and the wealth of evidence that such support is widespread, it seems natural to assume that reciprocal ‘upward’ flows of support are also common and expected. This reasoning is at the heart of conventional models of inter-generational reciprocity, exchange and bargaining (e.g. Bernheim, Shleifer and Summers 1985; Caffrey 1992; Dowd 1975; Lillard and Willis 1997; Pezzin and Schone 1997). In some Asian cultures, the rhetoric is that parents give children the ‘gift of life’, and children later care for elderly parents ‘as a means of repaying the tremendous debts ... owed for producing and caring for them in infancy and childhood’ (Lamb 2000: 46). Inter-generational reciprocity is perceived as a central element of the ‘life-span relationship’ between parents and children (Vatuk 1990: 66), with the investments made at one point in time being repaid at a much later stage (see also Harper 1992: 170; Knodel, Ofstedal and Hermalin 2003: 37 ff.; Lopez 1991). In Kidul, however, we found little evidence of a real or even normatively prescribed reciprocal link between provided and received support.

One reason for the lack of reciprocity in rural Java may be the manner of inter-generational wealth distribution, which militates against its strategic use to secure old-age support. Inheritance is usually passed on during the parents’ lifetime to avoid conflicts among heirs (see Geertz 1961: 51 ff.). Only spouses and children normally stand to inherit, and it is considered ideal to give each child an equal share of the estate. (In some families and areas of Java, the Islamic rule of benefiting sons over daughters is invoked.) The system thus differs fundamentally from a stem-family system in which one child receives the bulk of the inheritance in exchange for becoming the designated carer for older parents (e.g. Caffrey 1992). The equal division of property, especially land, results in what are often small, unprofitable shares that are then quickly sold, leaving little lasting benefit. In practice, wealth is frequently distributed piece-meal in response to family needs, making it inappropriate to attach any conditions to its receipt. Thus, although Mbah Sum had been extremely generous to a wide network of relatives over a long period, not one beneficiary felt obliged or able to care for her when she became dependent.

A more fundamental reason for the lack of significant reciprocal flows of upward support must be sought in the logic of parent-child relations in Java. We found widespread agreement that the issues of giving support to children and receiving support in old age are – and should be – separate. Even parents who had shown tremendous generosity towards their children did not draw on notions of reciprocity to legitimise a claim for support: they, too, talked of their reluctance (sungkan) to receive support and their fear of being a burden (beban) (cf. Djamour 1959: 166). Neither high nor lower status villagers talked in terms of a debt (hutang) that children have towards their parents, nor was there mention of parents having the right to (berhak), or deserving (berjasa), support in old age from children or grandchildren. At best, people would express hope that support would be forthcoming should they need it. Adult children who provided assistance to their parents did not refer to previously received gifts and support as the reason for the help that they were giving. In Java, to use the language of exchange or to treat parental support as a debt that is to be repaid, is considered to be inappropriate. Instead, parents’ love (sayang) is unconditional (cf. Finch and Mason 1993). Explicit expectations may only legitimately be attached to older people’s generosity towards other relatives such as grandchildren, nephews and nieces. The difference is that these relatives do not normally benefit from the individual’s wealth or inheritance: if valuable gifts take place, they are voluntary and may legitimately have obligations attached to them. Hence Mbah Winar, in Case Study 3, was able to voice the expectation that in return for the house and financial support, his grandson and granddaughter-in-law would care for him and his wife should it be needed. Similarly, Sum had been promised care by her granddaughter Diana in exchange for the discounted sale of her house.

Summary and implications

This paper has assessed the dependency status of older people in rural East Java and examined the role that they play in their families. Contrary to the widespread perception that population ageing creates burdens on families, most older people are not dependent. Only one-in-ten older people in Kidul were in poor health, and the majority continued to work or had income from pensions or land. This was true also of older people who lived with an adult child or grandchild. As well as their low support needs, not all older people had descendants on which they could depend. Childlessness and population mobility were high, more than a quarter of older people did not live with a child, and only one-in-two lived with a mature child or grandchild. All in all, only a minority (20%) of older people were dependent on descendants for material or physical assistance. This minority deserves closer examination in future research. How are their needs met? Is the support they receive adequate? Is their dependence a threat to the prosperity of their families, especially vis-à-vis the grandchildren’s need for education and health care?

Many older people far from being a ‘burden’ were vital to the survival and welfare of their families. It is conventionally assumed that co-residence with a child indicates a net flow of support up the generations, from young to old, but close study of the older people who lived with a descendant reveals that in almost half the cases, the older generation provided the economic backbone. In these households support flowed unequivocally downward, and in many other cases, older people were independent or managing to balance the provision and receipt of material and practical support. The importance of older people was clear in various situations: caring for young or unmarried children, taking on parenting responsibilities for grandchildren and shoring up adult offspring who had failed to establish or sustain their independence. Older people with regular sources of income like pensions were particularly likely to acquire dependants, whilst older people of all economic strata stepped in to protect family members in crisis. In Java, unlike many other parts of Southeast Asia, there is no preference for extended family households, and where co-residence occurs it is more often a response to vulnerability in the younger, not the older, generation.

What are the implications of these findings for older Javanese people, for ageing research and for policy? The expectation that older parents are ‘never heartless’ towards their children, combined with economic conditions that make it difficult for young villagers to establish themselves, mean that many older people continue to provide inter-generational support even at advanced ages. Older people’s own material welfare and security can then be compromised, either because the income is shared among many, or because key assets are sold or passed on, undermining the older person’s ability to maintain their independence. Moreover, the parents’ generosity is not tied to claims to, or even expectations of, reciprocal support by children. As a result, they may find themselves in a double-bind: having provided support to their limits, older people may end up dependent on descendants who are incompetent or negligent.

Several implications for ageing research in developing countries are apparent. First, the findings add to the growing evidence that older people are far from homogeneous, much less a population that as a matter of course is dependent. Analysis and interpretation need to recognise subgroups of the older population differentiated by their health, economic status and kin availability. Further research is needed to investigate the contributions made by active older people in various settings and situations. Second, it is abundantly clear that the direction of flow of inter-generational support cannot be inferred from co-residence and that more attention must be paid to actual exchanges and practices. For example, to increase the understanding of inter-generational support flows in households, data are needed on the ownership of assets, all sources of income, the extent to which resources are shared, the identity of members with financial or practical responsibility for various tasks or outlays and non-working members’ entitlements to household wealth. In addition, to understand the ways in which support arrangements unfold over the family lifecourse, retrospective and longitudinal data on relations and exchanges are necessary. These kinds of information are not readily disclosed by respondents in a single survey or panel interview: rather, it is necessary to establish familiarity through repeated visits. Third, ethnographic research clearly has a role to play in uncovering the logic of familial and inter-generational relations, and its findings suggest that some of the standard household survey assumptions about agents, motivations and exchanges require revision. In Kidul, for example, it is clear that notions of bargaining and exchange did not motivate parental generosity.

Only tentative policy suggestions can be made from the findings. The finding that older people are far from universally dependent, indeed that many support dependants, should reassure policy makers and encourage the development of targeted approaches. Rural older people do not as a rule expect to retire at 60 years of age. Providing employment opportunities or extending credit to allow older people to continue working, especially in the traditional sectors increasingly eschewed by the young, may represent a way of ensuring continued independence in old age. Moreover, the evidence on the uses of pension incomes demonstrates clearly their dual functions of protecting older people and shoring up wider family networks. If Indonesia is to develop broader social protection measures for vulnerable groups, to place regular, reliable income into the hands of more older people than is currently the case may be an effective strategy. On the other hand, the fact that family support for older people cannot be taken for granted should guard against complacency: children are neither necessarily available to provide support, nor does the rhetoric of filial obligation and reciprocity have much valence on the ground. Even in rural Southeast Asia, it would seem, there is a role for market and state in the provision of old-age security.

Acknowledgements

The material in this article was first presented at the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP) Regional Population Conference on Southeast Asia’s Population in a Changing Asian Context, Bangkok, Thailand, 10-13 June 2002. I thank The Wellcome Trust and the UK Economic and Social Research Council for generous funding of the research on which this paper is based. Suggestions by Philip Kreager and two anonymous referees have been extremely helpful in revising this article. All remaining shortcomings are entirely mine.

Footnotes

For the semi-structured interviews with family members, respondents were not chosen at random, but ‘opportunistically’ on the basis of availability in Kidul and willingness to be interviewed. By contrast, participants in the household survey were randomly selected, giving rise to a sample of 51 ‘young’ households.

Figures from the Indonesian Bureau of Statistics (BPS) show that for Indonesia as a whole, 73 per cent of men and 33 per cent of women aged 60 and more years work (although work is not defined) (Wirakartakusumah, Nurdin and Wongkaren 1997). According to the 1993 Indonesian Family Life Survey, 70 per cent of older men work for a salary, income or profit, and more than half of these state that they work more than 34 hours a week. Among women, 36 per cent worked.

The consumption figure is a rough estimate from the household survey based on the average per head expenditure in nine households – all with an older person and in the middle two economic strata. Only households for which the consumption data were deemed complete and reliable were included.

For comparative data and a discussion of the likely causes of childlessness in Indonesia, see Schröder-Butterfill and Kreager (2003); Kreager (2004); Indrizal (2004); Marianti (2004).

Table 5 refers to all older people. Among those with at least one surviving child, one-in-five lived alone or just with a spouse, and only 55 per cent lived with a child or grandchild. Of the latter, 28 per cent lived with a young child or grandchild.

Using a case study approach of 20 older people in two sites in Indonesia, Beard and Kunharibowo (2001) distinguished six support relationships between older parents and their adult children. These similarly comprise varying degrees of downward, upward and balanced flows of support, as well as a category of no flows. Their analysis was confined to older people living with an adult child, and they found an even higher proportion of older people to be net providers of inter-generational support.

All personal names in the case studies are pseudonyms.

In Kidul, 16 per cent of older people received a pension, and 15 per cent owned rice-land.

References

- Adlakha A, Rudolph DJ. Aging trends: Indonesia. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1994;9(1):99–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00972068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananta A, Anwar EN, Suzenti D. Some economic demographic aspects of ‘ageing’ in Indonesia. In: Jones G, Hull T, editors. Indonesia Assessment: Population and Human Resources. Canberra and Singapore: Australian National University and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; 1997. pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. Research directions in the region: past, present and future. In: Phillips DR, editor. Ageing in East and South-East Asia. London: Arnold; 1992. pp. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Esterman A, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Rungie CM. Aging in the Western Pacific: A Four Country Study. Manila: World Health Organisation; 1986. (Research Report 1, World Health Organisation (Western Pacific Region)). [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Hennink M. The circumstances and contributions of older persons in three Asian countries: preliminary results of a cross-national study. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 1992;7(3):127–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Hermalin A. Research directions in ageing the Asia-Pacific Region: past, present and future. In: Phillips DR, editor. Ageing in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Policies and Future Trends. London: Routledge; 2000. pp. 51–81. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar EN. Demographic Characteristics of Aging in Indonesia. Jakarta: Ministry for Population and National Family Planning Coordinating Board; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Asher MG. The future of retirement protection in southeast Asia. International Social Security Review. 1998;51(1):3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos A, Lloyd-Sherlock P. Non-Contributory Pensions and Social Protection. Geneva: International Financial and Actuarial Service, International Labour Office; 2002. (Issues in Social Protection Discussion Paper 12). [Google Scholar]

- Beard VA, Kunharibowo Y. Living arrangements and support relationships among elderly Indonesians: case studies from Java and Sumatra. International Journal of Population Geography. 2001;7(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim BD, Shleifer A, Summers LH. The strategic bequest motive. Journal of Political Economy. 1985;93:1045–76. [Google Scholar]