Abstract

Contemporary trends in population ageing and urbanisation in the developing world imply that the extensive out-migration of young people from rural areas coincides with, and is likely to exacerbate, a rise in the older share of the rural population. This paper examines the impact of migration on vulnerability at older ages by drawing on the results of anthropological and demographic field studies in three Indonesian communities. The methodology for identifying vulnerable older people has a progressively sharper focus, beginning first with important differences between the communities, then examining variations by socio-economic strata, and finally the variability of older people's family networks. Comparative analysis indicates considerable heterogeneity in past and present migration patterns, both within and between villages. The migrants' contributions are a normal and important component of older people's support, often in combination with those of local family members. Higher status families are commonly able to reinforce their position by making better use of migration opportunities than the less advantaged. Although family networks in the poorer strata may effect some redistribution of the children's incomes, their social networks are smaller and insufficient to overcome their marked disadvantages. Vulnerability thus arises where several factors, including migration histories, result in unusually small networks, and when the migrations are within rural areas.

Keywords: vulnerability, migration, social stratification, networks, Indonesia, anthropology, demography

Introduction

Population ageing and urbanisation are two of the most formidable structural transformations of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Labour migration, predominantly of younger people, exacerbates age-structure imbalances in rural areas of the developing world by removing young adults at the very time that the older population is increasing. Should there be alarm at this conjunction? At present the answer is unclear, since the impact of migration on older people's family support networks has not been studied systematically. This paper begins by reviewing the implications of the conjunction of ‘population ageing’ and ‘urbanisation’, notes the limitations of aggregate data as a guide to the vulnerability of older people, and introduces the survey and ethnographic data from a longitudinal study of three Indonesian communities that will enable an examination of the variable levels and patterns of migration and their impacts on older people's support.1 The paper focuses on the flows of support from younger to older kin, although a complete account would show that the flows of support are rarely unidirectional, and that intra-generational and community transfers and ties are also important. The narrow focus on exchanges with children is adopted for reasons of space and because it is apt: in the situations that lead to older people becoming vulnerable and unable to cope on their own, the role of younger relations comes to the fore.

Assessing the role of migration in shaping the situation of rural older people requires two significant departures from the research paradigms that prevail in the study of the impacts of population ageing in Southeast Asia. The first is to distinguish the socio-economic strata in local communities, as these influence both the propensity to migrate and the sustainability of contacts between young migrants and their elders. The second is to consider the wider family network as the reference unit of support, since migration influences the sub-set of family members that take on responsibilities. The composition of this sub-set is likely to change over time, with the availability of various supporters and what they are prepared to do varying accordingly. For this reason, children are defined here in an extended sense, to include adoptees, grandchildren, nieces and nephews who undertake children's support roles.2 The paper defines ‘vulnerability’ in terms of the size and composition of the networks on which older people rely, and the discussion focuses on two aspects of network dynamics: the extent to which the migration of young family members becomes a constraint, and the selectivity of its effects among older people.

Social strata and networks are obviously critical where, in the absence of state provision, they have a strong influence on who is available to help and on the material resources that are to hand. The changeability of support networks, just noted, makes unreliable a definition of vulnerability solely in terms of demographic and economic attributes, as is the common practice of household surveys that collect data only on contacts and support at a given point (or points) in time. An elder's social position and network size and membership are outcomes of past lifecourse events (Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill 2005). The process by which people interpret past events shapes the meaning of current events and relationships with family members and others in the community; these, in turn, condition the kinds and levels of support that are available. The continuity of support needs to be demonstrated, not assumed. Evidence from ethnographic and lifecourse approaches is clearly needed to complement and correct cross-sectional survey data. From this point of view, vulnerability is the incremental and indirect outcome of those factors that have either kept strong network links from being forged or made them unsustainable. In rural Indonesia, vulnerability is associated in people's perceptions with the need, or likely need, to rely on charity, coupled with the entailed loss of social reputation.

Variations at the level of the community are examined through variations in the prevalence of migration by socio-economic strata and their implications on the dispersal of adult children from their communities of origin and the kinds of support that the children provide. The focus is on the consequences of children's mobility for older people, rather than on the determinants and patterns of migration per se, although the principal cultural and economic forces that encourage population movement are considered. Most attention is given to the relatively disadvantaged strata, in which the great majority of vulnerable or potentially vulnerable older people are found. Among the poorer strata, a distinction can be made between those who are able to retain the wider respect of their communities, and those whose lives end sadly.

Ageing and urbanisation: a crisis in the making?

The stories that macro-representations tell of converging and diverging population trends can readily appear alarming – a legacy from Malthus. Images of vulnerability can now be constructed more or less at will from statistical compendia, and Indonesia provides a case in point; the growth of the absolute and relative population of older people appears to be compounded in rural areas by the exodus of the young. Indonesia has the fourth largest population in the world and the seventh largest elderly population, so clearly possesses the massive demographic weight that makes alarmist scenarios compelling. Can we say that migration is a cause of vulnerability in old age (or, at least, a factor that independently worsens older people's circumstances)?

An alarmist scenario as built by macro-reasoning can be sketched. The United Nations (2002) estimated that Indonesia's urban population has increased almost fourfold since 1950. One-half of its people will live in urban areas by 2010, making it an exemplar of a worldwide trend, and the pace of urbanisation has recently increased. Some 30 million people will be added to the urban population during the current decade, an increase of one-third. The Total Fertility Rate meanwhile has declined to just above the replacement level (2.25 births per woman of reproductive age), which underscores the predominant role of migration in the rapid urban population increase (Firman 1997: 106). Over the longer term, from 1990 to 2025, the accelerating flight to the cities is expected to decrease slightly, but will nonetheless double the percentage of urbanites from 30 to 60 per cent. Younger age groups, of course, predominate in internal and international migration flows. In Indonesia, as elsewhere, migration is greatest among those aged 20–24 years, and the majority of moves are made by those aged 15–29 years. In recent years, the likelihood of a regional migration at these ages has been three to four times greater than at all older ages (Muhidin 2000, cited in Ananta, Anwar and Miranti 2001: 18).

It has also been estimated that during 1990–2025, the percentage of the population aged 65 or more years in Indonesia will increase by a staggering 414 per cent (Kinsella and Taeuber 1993). The elderly percentages in the three provinces with which this paper is concerned are expected to rise from between 7.3 and eight per cent to between 12 to 16 per cent (Ananta, Anwar and Suzenti 1997). These figures, of course, mix urban and rural populations. As rural areas lose more of their young adults, the increase of the older population outside the cities is likely to exceed the national and provincial averages. As we shall see, this is already the case in two of the featured communities. What, then, will happen to older people who remain in the towns and villages?

The answer to this question is critical if effective use is to be made of the limited public funds available for pensions and welfare. At present, self-reliance coupled with support by children is the norm, and there is good reason to believe that this will remain the mainstay of older people. Recent estimates indicate that in Indonesia, nearly one-quarter of women and almost one-half of men aged 65 or more years remain in the labour force (United Nations 2002). Such estimates inevitably under-report part-time and informal-sector labour, particularly among women. Much of this supposedly commendable independence is, however, involuntary. No general state pension exists, and mandatory formal sector schemes cover perhaps 15 per cent of the labour force (Asian Development Bank 2000). Even currently proposed reforms have been described as impracticable (International Labour Organisation 2003; Arifianto 2004). In short, reliance on self- and family support continues to be the norm, even as the decline of fertility and the exodus of young people remove children from the rural communities.

Redefining the problem

Like most crisis scenarios, the sketched bleak picture presumes patterns of behaviour and predicts problems from aggregate trends, but there are good reasons to question the projections of crude inter-generational imbalances and a deepening rural-urban dichotomy. Let us briefly examine these two simplifications. First, chronological age does not exactly equate to family generations, and being aged more than 60 or 65 years is no index of incapacity or need. The onset of physical frailty, even amongst those who experience a lifetime of manual labour, may begin earlier or later. Very different lifecourse trajectories are the foundation of the immense variability among older people. Semi-skilled workers, for example, tend to find their options in later life reduced by a low level of accumulated social and economic capital (Vera-Sanso 2004). Even the poorest in this group may find that adult children make major economic demands long after their own earning capacity has declined in old age (Schröder-Butterfill 2004). In contrast, the property and status of better-off older people may provide more opportunities to assist their children, which in turn conditions the younger generation's responses to their parents when their care and support needs rise.

The implications of the large-scale migration from rural areas of young adults for the size and functioning of family support networks must be examined with reference to socio-economic differences. Put another way, understanding the significance of migration requires attention to the various sub-groups of the older population and how they are affected. Whether it is especially the absent children of the lower strata of older people that do not provide assistance, compounding the group's economic vulnerability, is an interesting question. In short, the ‘crisis scenario’ that sees a rising proportion of older people bereft of support through their children's migration can be neither sustained nor refuted without first disentangling the inter-play of status and social network. Children who move away from their home communities are not necessarily ‘lost to the system’ of local support networks, whilst those close-at-hand are not necessarily esteemed or trustworthy. As we shall see, the children's location, whether nearby or a short or long distance away, is a proxy for neither support nor neglect.

The second reason why the aggregate trends in ageing and urbanisation do not translate directly into increasing elderly vulnerability also lies in the moderating effects of social networks. As Hugo, Champion and Lattes (2003) have remarked, censuses and government surveys persist in using a simple rural-urban dichotomy in data collection, even as increased mobility has diversified people's locations and living arrangements or ‘time-space use’. In Indonesia, most residential change involves temporary and circular migrations, commuting and other shifts that censuses and surveys find difficult to capture. Local studies are needed to describe the adaptive strategies, networks and support arrangements which are the usual motor of population movements (Ananta, Anwar and Miranti 2001; Hugo 1982). They show that temporary and circular movements encompass ever greater distances; and that with increased information flows, movements become more diverse, individualised and locally distinct (e.g. Guest 1989; Firman 1997; Spaan 1995). An understanding of the network processes that keep movers connected to communities of origin is critical to understanding the relationships between aggregate trends and personal support strategies.

In Indonesia and elsewhere, migration and gerontological research address similar questions: to what extent are status differences associated with and sustained by migration patterns? Does the role of family networks in migration reinforce or mitigate such differences? Can specific sub-groups of older people be identified whose vulnerability is a function of similar conjunctions of migration, status and network attributes? What aspects of support are most at issue where vulnerability is concerned? Is, for example, the absence of children associated with absolute material poverty and a lack of the most basic resources? In a sudden health crisis, do problems arise chiefly because there is no local family help? What impact does an absence of children's support have on an older person's social standing? To what extent are siblings able to co-ordinate their support to compensate for the effects of distance from their parents?

Comparing rural communities

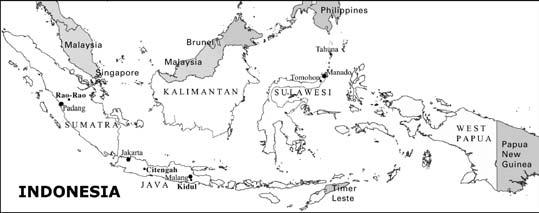

To elucidate these issues, this paper examines data from the Ageing in Indonesia study of three rural Indonesian communities: Kidul, in East Java; Citengah, in West Java; and Rao-Rao, in West Sumatra (see Note 1). The three locations, which are shown on Figure 1, were selected because on several dimensions they are characteristic of rural settlements and populations in their respective islands. Each retains a traditional agricultural base that, for some time, has been subsumed in a mixed economy that is reliant on the employment opportunities and commercial markets of regional urban centres. Population mobility is central to this symbiotic adaptation and, as we shall see, is crucial to understanding how the differential levels and patterns of integration between the rural areas and the regional and national economies affects older people.

Figure 1.

Locations of the study communities in Indonesia.

The age structures of the three villages have been conditioned by migration. Kidul and Rao-Rao have been most affected by migration and have the largest shares or the population aged 60 or more years, 10.6 and 18 per cent respectively, higher shares than in their provinces. Citengah is most reliant on its agricultural base, and 7.3 per cent of its population is aged 60 or more years, close to the provincial level. The two Javanese communities evince the most prevalent family pattern in Indonesia, nuclear families with bilateral kin. Rao-Rao's population is Minangkabau, the fourth largest ethnic group in Indonesia (with four million people). They trace descent through the matriline, and extended family arrangements are the norm. Islam predominates in all three villages, but there is a significant Hindu minority in the East Javanese community.

Methodology

The data on migration, family networks and social status were collected using qualitative and quantitative methods. Ethnographic studies and the analysis of life histories of older people have enabled the mapping of family networks and their exchanges over time. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with between 80 and 97 per cent of the older people in each village. Repeated, in-depth interviews were conducted with between 20 and 60 of the informants, and in most cases complemented by in-depth interviews with one or more other adult family members. In addition, a survey of the household economy and inter-household exchanges was conducted in each village. It comprised a random sample of 50 households with elderly members and 50 households without, and had two important functions: to reveal the role of social and economic status variations within and between family networks in shaping responses to older people's needs; and to enable quantitative analysis of the role of support from the members of the social network that had moved away.

Rural Indonesians are very sensitive to dfferences of status and wealth, without recourse to an explicit vocabulary of class or caste. Anthropologists' and historians' attempts to characterise these dfferences have generally relied on both economic and social indicators since, over the long term, some socially pre-eminent families have acquired the capital that enables them to sustain control over prime agricultural land (sawah), to dominate local patronage and trade, and to accumulate social and political influence. Earlier studies tended to treat social dfferences as, in effect, asset-classes based largely on landholding (e.g. Penny and Singarimbun 1973; Hart 1986; Hüsken and White 1989). More recent studies have argued that this framework remains useful for understanding the contemporary society, because the established elites have been instrumental in expanding rural industry, construction and transport (e.g. Breman and Wiradi 2002; Sumartono 1995; Wolf 1992). The resulting broad picture is of a society with three or four strata:

Established landed families, now buttressed by ownership of enterprises and jobs in the civil service.

Smaller property owners, including shopkeepers and local businesses.

The rural proletariat.

The very poor, the most vulnerable among the proletariat, including older people no longer able to work, widows and unmarried divorcees (a subgroup of III).

Although something of an anachronism, the typology is still a useful categorisation of the villagers' family support systems. The long-established, landed families continue to be prominent among the rich, and the possession of substantial sawah remains a mark of higher status, but the majority of family income and influence now comes from other sources. The typology may reify appearances and reputations, however, since status is not determined solely by economic position. The anthropological literature is replete with cases of downward mobility, where a member's misconduct (family conflict, promiscuity, irreligion, profligacy or brutality) has undermined the social respect that is required for a network to function cohesively. Other families rise in society as their economic achievement and moral behaviour earn respect (e.g. Jay 1969; Schröder-Butterfill 2002).

The richest families (Stratum I), described variously as orang kaya, wong sugih or benghar pisan in East and West Java, and urang baharto in Sumatra, are distinguished by deference and respect in daily social life. Poor villagers, for example, avoid contact with rich kin, lest people see them as pandering for favours. The survey data on assets, income and expenditure, patterns of education and religious observance (notably pilgrimage) confirm local opinion. Stereotypically, the rich own agricultural land, modern consumer goods like televisions, telephones and quality furniture, and live in brick-built houses with tiled floors and modern amenities. In the Javanese villages, the rich include not only large landowners but successful business people and high-ranking civil servants (see Schröder-Butterfill 2002: 129 ff.); in the Sumatran village, the rich typically combine agricultural wealth with profits from the successful cloth trade. The villagers were also able to agree readily on the identity of the poorest families (Stratum IV), that they referred to as kurang mampu, wong susah or urang bangsek, and whose income depended significantly on charity. These families own neither productive assets nor consumer goods, typically live in houses made of wood or bamboo with earthen floors and without basic amenities, and are unable to enjoy quality food or medical care. In the Sumatran village, most were also newcomers.

In the intermediate groups, households belonging to Stratum II typically benefit from reasonably secure and multiple incomes, either because several household members work, or because wages are supplemented by support from parents or agricultural profits, while those in Stratum III depend on their labour for day-to-day subsistence and lack the safety net of reliable multiple sources of support. For the latter, the threat of descent into outright destitution is ever present, and some households occasionally receive charitable support. The survey data showed that Strata II and III were distinguished by considerable dfferences of wealth and material assets, the former having double the average income of the latter. All this said, no explicit social boundaries dfferentiate the groups. A common phrase used in all three communities to denote people lower down but not at the bottom of the social scale is cukup-cukupan, which may be translated as 'just suffcient' or 'ticking-over'. This phrase aptly captures those at the margins of subsistence in Stratum III. Interestingly, several dfferent phrases are used when referring to people between the 'rich' and those who are 'ticking over' in Stratum II: lumayan [comfortable], jararaneng [suffcient], manangah [middling] and sadang [tempered].

Older people are not equally present in every strata, and this paper is chiefly concerned with the lower groups. In the two Javanese communities, the lower two strata contained just over one-half (55%) of the older people, whereas in Rao-Rao, which benefits from highly developed streams of labour migration, they comprise only 40 per cent. Most older people in the lower two strata are 'ticking over' rather than reliant mainly on charity: the percentages in Stratum III were 66 in Kidul, 75 in Rao-Rao, and 85 in Citengah.

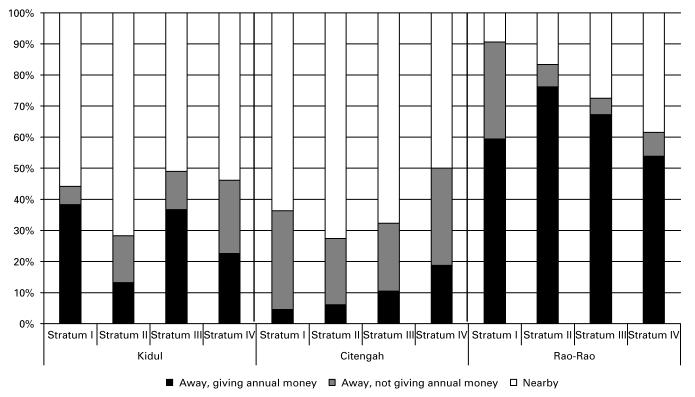

Patterns of migration

Figure 2 summarises the migration differentials by strata in Kidul, Citengah and Rao-Rao. Given that the overall percentages of out-migrants in the younger generation were 46, 45 and 75 per cent in Kidul, Citengah and Rao-Rao respectively, the scale and importance of migration are manifest. The variation by strata in the percentage of migrants among the adult children was considerable (between 28 and 91%). Two categories of migrant children were identified: those ‘nearby’, who had left the parental home but lived in an adjacent village or community, from which visits were easy on foot or by a short bus journey and contacts in most cases were frequent; and those ‘away’, at least 10 kilometres distant. In only four columns of Figure 2 is the percentage of children ‘away’ less than 40 per cent, and even in these cases it is around one-in-three. For Kidul, most ‘away’ children (43%) lived between 10 and 100 kilometres from their parents (i.e. a distance at which visits could be accomplished readily), but more than one-third lived on different islands or abroad, and the remaining 20 per cent lived on Java but over 100 kilometres away. For Citengah, two-thirds of the children who were ‘away’ were within 100 kilometres, and 28 per cent were on a different island or abroad. Adult children from Rao-Rao were more dispersed, typically in other parts of Sumatra (46% of the ‘away’), Java or another island (44%), or abroad (8%).

Figure 2.

Location of adult children by economic status of parents and patterns of monetary support by children away. Source : Author's household survey, 2000.

The prevalence of migrant children by strata and the importance of their monetary gifts varied among the villages. Migrants were particularly numerous in Rao-Rao, Sumatra, and a progressively lower percentage of the young people in the successively lower strata lived away, from 91 per cent among the rich to 62 per cent among the poor (by contrast, the highest percentage in any stratum in the Javanese communities was less than 50 per cent). The predominance reflects the cultural position of labour migration (rantau) in Minangkabau culture and history. From the late 19th century, the Minangkabau established a reputation as traders, and many lived at considerable distances from their natal villages, with large communities in Jakarta and elsewhere in the archipelago. Young men are, without exception, expected to leave the community for extended periods, and their identity and status depend on success in their rantau employment (Kato 1982; Indrizal 2004). One-quarter of Rao-Rao's young migrants in Stratum III, and around 40 per cent in the two upper strata, lived outside Sumatra.

Young women were only slightly less involved in this movement, although there is a strong expectation that at least one daughter remains in, or returns to, the home village, to maintain the ancestral property and manage its revenue. The long-standing role of rantau in establishing individual and family identity has resulted in large and effective extended family networks; these facilitate employment away and the sending of remittances, the latter often organised through religious organisations or through special migrants' associations. Many men and women come to reside away permanently, but continue to contribute to their home communities through kin and religious networks. The gradient from rich to poor is a direct reflection of the major role that migration plays in establishing reputation and extended family income. Migration, coupled with better access to education for the higher strata children and better-connected networks in distant sites, helps to sustain the social position of older people in the upper strata. In contrast, nearly 40 per cent of Rao-Rao's Stratum IV households have migrated into the community to take up the low-paid agricultural jobs that are shunned by members in the higher strata (they engage in the rantau). Both older people and their children in these households are locked into the subsistence sector.

The patterns of migration in the two Javanese communities differ markedly from each other yet both in some respects are the opposite of Rao-Rao's. The highest percentages of children ‘away’ were in the poorest stratum in Citengah and the two poorest strata in Kidul, while the families in Stratum II were the least likely to have children away. Such differences, once again, may be traced to historical patterns of adaptations to the Indonesian economy and society. Citengah (West Java) presents the classic image of a Javanese village sustained by rich rice lands (sawah) that remain almost entirely in family hands. Over one-half (55%) of its families possess at least some sawah (including tiny plots owned by Stratum III households). The continuing importance of traditional agricultural employment keeps substantial percentages of Strata III (68%) and IV (50%) children in the community as tenants and labourers on the wealthier families' lands.

An analysis of those ‘away’ by distance reveals other contrasts with Rao-Rao, for the great majority of Citengah's migrants had moved relatively short distances (less than 100 km) to regional centres like Bandung. The concave relationship between out-migration and strata reflects several factors. In Strata III and IV, there is not enough work in local agriculture to support all children, and between one-third and one-half leave. Few of these families have the established kin networks of earlier migrants; in consequence, between 11 and 17 per cent of the children who migrate away have relied on transmigration schemes to other islands, an option which in most cases removes them permanently as a source of elderly assistance. In the better-off families, more education has given access to jobs in local government and business, and more children lived nearby and commuted to towns within 30 km.

The East Javanese community of Kidul lacks both the advantages of extensive sawah and a history of systematic kin-network migration. Only 16 per cent of the households possessed quality rice land, and although many had non-irrigated farmland (tegal), agricultural holdings provided a living to only a small minority. Patterns of employment have, in consequence, long been diverse. The largest occupational group, around one-quarter of the population, is engaged in local trading; the remainder have diverse occupations in small manufacturing, food production, construction and transport. As in Citengah, a large minority of the children of Strata III (15%) and IV (23%) families had left for other islands. Commuting to the regional urban centre of Malang was common. Older people in this community, including those with few resources, commonly assist their children not only in marriage, in building a house, and where possible by giving small plots of land, but also support their children's households through payments and their direct labour. These practices help to keep almost one-half of the younger generation in Strata III and IV resident locally, and over two-thirds of those in Strata II.

The logic of network support

The presented evidence has revealed a complex pattern of migration differences between the three communities and that these reflect historical factors, environmental constraints (e.g. fewer land resources in Kidul than in Citengah), and cultural systems (e.g. the role of rantau in Minangkabau identity). Variations in the level of migration by strata are partly responses to such factors. In Rao-Rao, the many long-distance migrations are the major source of wealth and prestige for the matriline, and elders are identified with, and receive the benefits of, successful family migration networks. Matrilines in the lowest strata are at a considerable disadvantage because they do not benefit to the same extent from such networks and the social and economic capital that they accumulate. In the Javanese communities, some members of the upper strata have assisted their children's movement away from the community while maintaining material ties; their position is analogous to the better-off elders in Rao-Rao. In the Javanese settlements, by contrast, much greater out-migration prevails among the poorer strata, for they have few local resources and need to look elsewhere for subsistence.

Having clarified these differences, we can now examine the contributions that younger migrants make to their parents, whether these vary by strata, and the extent to which the lack of support by migrants is an important factor in the elderly parent(s)' vulnerability. In Figure 2, the darkest bars represent the percentage of all children who are ‘away’ and give annual monetary support to their parents. The surveys asked the older people whether specific children had brought or sent any money at least once during the previous year, and collected data on various other types of support, including health care, companionship, gifts of food and visits. Figure 2 may give the impression of a lower level of annual gifts from those ‘away’ than is the case, since giving is expressed as a percentage of all children. Table 1 therefore calculates the percentage of children ‘away’ who provided annual monetary support. This shows considerable levels of annual giving by those away in all strata in Kidul and Rao-Rao, and that support went to better-off elders as well as the poor.

Table 1.

Percentage of children who are ‘away’ who make annual monetary gifts to their elderly parents, three Indonesian village communities in 2000

| Kidul | Citengah | Rao-Rao | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stratum I | 86.7 | 12.5 | 65.5 |

| Stratum II | 46.7 | 22.2 | 91.4 |

| Stratum III | 75.0 | 32.4 | 92.8 |

| Stratum IV | 49.0 | 37.5 | 87.5 |

Source: Author's household survey, 2000.

The level of annual monetary support is a useful starting point for understanding the logic of family networks. For migrants at greater distances from the village, to remit money is obviously simpler than providing food or care-giving, and can be delivered by other family or community members. The sums involved in annual gifts are in general very modest. Individual gifts normally do not exceed Rupiah 200,000 (about £15 Sterling), and are often given during a migrant's annual home visit, usually at Idul Fitri (the end of the Muslim month of fasting). The function of these small sums is clearly not to provide mainstay support, but rather to affirm membership in a family circle and its continuity. In some cases, gifts are in effect promissory notes of more substantial help in the future. It is important, however, not to interpret exchanges in exclusively utilitarian terms, for infrequent and quotidian exchanges of all kinds manifest the solidarity and respective roles of the family members. Meeting uncertain future needs is not the crux of family life, but exchanges build up a web of mutual ties which the members hope will have this function.

In monetary accounting terms, elders may spend as much when a child visits as they receive as a gift. Put another way, the small sums that migrant children give are intricately bound into a pattern of exchanges; elders' real ability to participate in such exchanges (disguised, perhaps, by the fact that their contributions rely in part on money they have previously received) is crucial to maintaining the parental role. The sums they receive may be used, for example, to pay for the schooling of younger children still at home or of grandchildren for whom they have taken responsibility. Networks, by their very nature, are redistributive.

As Figure 2 shows, the pattern of children's annual monetary gifts by strata moves in tandem with the overall proportion that is ‘away’, but with two exceptions: among Stratum I in Rao-Rao (nearly two-thirds of young people ‘away’ give monetary support), and among Stratum I in Citengah (where the level is 12.5 per cent) (see Table 1). In other words, although only a proportion of those ‘away’ send money, the pattern of annual monetary support varies among the strata with the level of migration. Evidently, many children ‘away’ remain members of their parents’ support networks, with nearly one-half or more making contributions in all strata in Kidul and Rao-Rao. The levels of monetary support are significantly less in all strata in Citengah, reflecting the greater agriculture-based self-sufficiency, and reinforcing its lesser involvement in the wider market economy. Out-migration is not then a general proxy for vulnerability.

Given that older people's support networks do not function exclusively in response to their needs and vulnerabilities, three widespread assumptions about inter-generational transfers require critical examination. The first is that support, because it is monetary, serves a primarily economic function; the second is that the need for ‘transfers’ is chiefly among those who receive them; and the third is that older people keep the material support that they are given. Research on inter-generational transfers has been driven primarily by hypotheses developed in western economies (where material acquisitiveness or consumerism has a strong influence). As the review by Lillard and Willis (1997) confirmed, this approach has been unable to establish any of the competing hypotheses about what motivates ‘transfers’ in Southeast Asia, and is accordingly unable to establish the main causes and strategies that underlie the heterogeneity of exchanges.

The striking fact is that support is not simply a response to elders’ overt material needs, because the sums involved are so small that they cannot be the primary resource on which older people depend. Regular giving is, in any case, not only practised in the two lower strata, where needs are more apparent, but in higher strata as well, where elders' own income and assets are sufficient. Migrants' support persists, moreover, even though other sources of elderly assistance are to hand. As Figure 2 shows, significant numbers of young family members live in the communities or nearby, and many provide assistance. These facts suggest that to understand the motivations and roles behind the transfers, a different approach is needed.3

Linking networks to vulnerability

The 102 elders who were interviewed in Strata III and IV are grouped in Table 2 according to the way that migration has shaped their family networks. Some elders have all their children living in the community or less than 10 km distant (labelled ‘all near’), and some have all of their children living further away at variable distances (labelled ‘all away’). Among the 25 in Rao-Rao, only one had a network confined to nearby children; for 10, all their children were away on rantau, and 14 had children both away and nearby (51% were away). The corresponding figures for elders with ‘some each’ in Kidul and Citengah were 21 and 20; of these children, 40 and 30 per cent respectively resided away. Both the migrant children and those who are co-resident or reside nearby contribute to parental support. In Kidul and Rao-Rao, a majority of elders in the lower two strata receive support in this ‘some from each’ pattern, and in Citengah, the same applies to slightly less than one-half (Table 2).4

Table 2.

Elderly people in Strata III and IV: types of support by location of children

| Kidul |

Citengah |

Rao-Rao |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | All near | Some each | All away | Total | All near | Some each | All away | Total | All near | Some each | All away | |

| 1. Number of elders | 35 | 9 | 21 | 5 | 42 | 19 | 20 | 3 | 25 | 1 | 14 | 10 |

| 2. Weekly/monthly money | 19 | 6 | 13 | – | 21 | 11 | 7 | – | 16 | – | 9 | 7 |

| 3. Annual money only | 7 | – | 5 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 5 | – | 2 | 3 |

| 4. Weekly/monthly food | 4 | 2 | 2 | – | 15 | 6 | 11 | – | 3 | – | 3 | – |

| 5. No support | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| 6. Not vulnerable | 11 | 4 | 7 | – | 23 | 14 | 16 | – | 6 | – | 1 | 5 |

| 7. Currently vulnerable | 13 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | – |

| 8. Prospectively vulnerable | 11 | 2 | 9 | – | 13 | 4 | 3 | – | 14 | – | 9 | 5 |

| 9. Total vulnerable | 24 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 19 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 19 | 1 | 13 | 5 |

Source: Author's household survey, 2000.

The second row in Table 2 records the elders in receipt of constant and regular monetary support. There were 16 in Rao-Rao, and 12 of them relied on weekly or monthly sums from children ‘away’ (including five in the ‘some each’ category, and seven whose children were all absent). In other words, three-in-four cases of regular and consistent support were migration-based, as might be expected in a rantau-oriented culture. The arrangements in the two Javanese communities were very different, as no elders received frequent support entirely from children ‘away’. Among the elders whose children were in the ‘some each’ category, four of the seven in Citengah and six of the 13 in Kidul received regular support from ‘away’ children. Overall, three-in-four Rao-Rao elders had regular support from migrant children, and approximately one-in-five in Citengah and one-in-three in Kidul.

These averages indicate the significant scale of migration from all three communities and the considerable variation in the sources of support for their older people. Children whose monetary gifts were less regular should not be discounted, for money gifts are but one aspect of the wider support and affirmational roles that kin and migration networks play. Annual gifts, as summarised in the second row of Table 2, were usually made during visits at major religious festivals; most of those who received regular monetary support from some children usually also received annual gifts from others. From an elder's point of view, even infrequent contacts and instrumental support from distant children affirmed their familial bonds and reputations in the community. The collected life histories have revealed cases in which health or financial crises prompted major discontinuities in apparently established patterns of support. Some ‘away’ children who previously contributed modestly then assume more important roles, for example, in paying for hospitalisation or returning to provide care. Nearby children's roles, which tend to predominate in local contributions of food in the ‘some each’ category, are also adjusted. Even so, a ‘snapshot’ assessment inevitably understates the importance of migrant children; no cross-sectional survey, even assisted by ethnography, can provide a longitudinal picture of network processes (see Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill 2005).

The lower half of Table 2 presents the levels of vulnerability of the studied elders. Those recorded as ‘not vulnerable’ belong to Stratum III and have several children who regularly contribute resources to their wellbeing. Several were relatively young or had a young spouse, and their labour sustained a capital base sufficient to withstand one health or economic crisis. ‘Currently vulnerable’ elders, in contrast, belonged in almost all cases to the lowest stratum, in which day-to-day living depended on charity. Triangulating the data from the survey, in-depth interviews and the observations of daily life, confirms that these elders were characterised locally by the term kasihan [pity]. Put bluntly, their situation in old age typified a bad ending to the life-course, which any ‘respectable’ person would wish to avoid.

The ‘prospectively vulnerable’ elders in Stratum III are those who, although poor, retained respect in the community by contributing regularly to the frequent social and material exchanges that mark the life-course, for example the slametan (neighbourhood ritual meals) associated with births, circumcisions and marriages (see row 8 in Table 2). They had a slender support network and most were dependent on a combination of their own labour and modest contributions from one or more children. A serious health or economic crisis in either generation – typically, an inability to continue working – is likely to move these elders from Stratum III into obvious dependence on charity and the associated stigma of kasihan.

This distinction between ‘current’ and ‘prospective’ vulnerability needs qualification in two respects. First, it is subject to the time limitations of the first round of research. The contributions of some ‘away’ children may have been little or nil in the last year only because they were establishing themselves in their new locations. Second, vulnerability is a matter of social perception, and some elders are in marginal and transitional situations, as with the ‘currently vulnerable’ in Stratum III who were still able to participate in social exchanges, but whose labour and incomes had all but ended, and for whom reliance on charity had begun and could not be disguised for long. Who can say what degree of crisis will make their growing dependency evident to the prying eyes of the community? In short, the distinction between current and prospective vulnerability reflects contingent estimations of status and kasihan. The role of social evaluation is a reminder that what creates vulnerability is not crises as such, but the incremental influence of status and network differences over the life-course, which leaves particular elders and their families susceptible to the crises.

Overall, the elders whose networks contributed nothing to their material wellbeing comprised only four to 14 per cent of those in the lower strata (Table 2, row 5). ‘Currently vulnerable’ older people, as a proportion of all elders in the lower strata (the ratio of row 1 to row 7) were, however, not limited to those without any inter-generational support: the percentage varied from 12 in Citengah, through 20 in Rao-Rao, to 37 in Kidul. Where successive generations shared poverty, the regular support that some children provided did not secure elders against the loss of reputation and the need for charity that constitute kasihan. Clearly, there are limits to the support that poor family networks can give.

Adding together the elders classified as ‘currently’ and ‘prospectively’ vulnerable provides a basis for enumerating all the older people whose basic means of subsistence is imperilled (lowest row of Table 2). Not surprisingly, the prevalence was markedly higher, approaching one-in-three (29%) in Citengah, and more than twice that level in Kidul (69%) and Rao-Rao (76%). The figures, by combining people's present and pending difficulties, without doubt exaggerate current local needs and require confirmation through a longitudinal study: the observation of events that would establish whether ‘prospectively’ vulnerable elders have been identified correctly. This work is proceeding. Estimating total vulnerability by combining ‘current’ and ‘prospective’ categories, provides, at least, a first estimate of the potential demand for income support in rural Indonesian communities.

Linking migration to vulnerability

Table 3 presents the numbers of children in the networks of elderly people. Row 5 indicates the numbers who gave weekly, monthly or annually to their elders; and rows 4 and 3 respectively show the numbers of migrant children who did and did not give support. The picture, like that of the migration patterns, is one of considerable heterogeneity. Comparing the averages in the ‘vulnerable’ columns in the last two rows of Table 3, however, provides a simple index of the impact of migration. Row 7 gives the average number of children providing support after the combined effects of migration and non-support are subtracted from the average number of children available per older household. Comparison of rows 6 and 7 shows that networks were depleted by on average 0.4 children in Kidul, 1.0 child in Citengah, and 1.5 children in Rao-Rao. However, the average number of children that contributed to vulnerable elders' households was higher in Rao-Rao (3.7) than in Kidul (2.4) or Citengah (1.6). The same comparisons, for the ‘non-vulnerable’ column, show that very few children failed to provide support in Kidul and Rao-Rao; whereas in Citengah, the non-vulnerable households' networks were larger, which more than compensated for the larger number of non-contributing children.

Table 3.

Network depletion : non-contributing migrant children in Strata III and IV

| Kidul |

Citengah |

Rao-Rao |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerable | Not vulnerable | Vulnerable | Not vulnerable | Vulnerable | Not vulnerable | |

| Totals | ||||||

| 1. Elderly households | 18 | 7 | 9 | 20 | 12 | 5 |

| 2. Number of children | 51 | 25 | 23 | 105 | 62 | 17 |

| 3. Non-contributing migrant children | 7 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 1 |

| 4. Contributing migrant children | 17 | 5 | 3 | 19 | 32 | 14 |

| 5. Contributing children | 43 | 23 | 14 | 81 | 44 | 16 |

| Averages | ||||||

| 6. Children per elderly household | 2.8 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 3.4 |

| 7. Contributing children per elderly household | 2.4 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 |

Source: Author's household survey, 2000.

Interestingly, the larger network size (5.3) of non-vulnerable households in Citengah resembled that of vulnerable households in Rao-Rao (5.2), whilst the number of children contributing to vulnerable households (1.6) in Citengah was very low. These variations reflect the differing impact of migration and social stratification in the two communities: in Citengah, the elders who possessed good rice land and were of higher status were able to keep more children in or near the community, whilst those of lower status were more likely to have seen the permanent departure of, and few contacts with, children. In Rao-Rao, stratification and landholding worked the opposite way: those with more substantial holdings had more migrant children and more support from them, whilst the children of poorer elders were more likely to be employed locally in the less remunerative agricultural sector.

What role, then, has migration played as a factor that disposes to vulnerability late in life? A direct estimate is the average number of non-contributing migrant children per elderly household (the ratio of row 3 to row 1), which can be compared to the overall loss of contributing children. Taking first the vulnerable households in Kidul, this ratio (0.39) was almost identical to the average depletion through non-contributing migrant children. In Rao-Rao, on average only 0.58 of the 1.5 non-contributing children were away; but in Citengah, 0.78 of the one non-contributing child was away. In contrast, the non-vulnerable households lost few contributing children through migration: none in Kidul, 0.2 in Rao-Rao, and in Citengah less than one-half of the loss (0.4 of 1.2 non-contributing children). Of course, children who lived locally may have contributed little or nothing, and be a net drain on the elders' resources (a pattern in Kidul described by Schröder-Butterfill 2004).

Conclusions: sub-populations of migrants and elders

The conjunction of population ageing and rural-urban migration is normally represented as a cause of concern for the welfare of the older population in rural and provincial areas, but close inspection reveals intricate and varied welfare implications. The prevalence of migration among young adults from the three communities has been amply demonstrated, but contrary to the stark picture of a recent and growing exodus of young rural migrants who leave their elders bereft of support, it has been shown that many poor older people have both adjacent and ‘away’ children who provide support. The younger network members take on complementary responsibilities, and cases in which all children have migrated and provide no support at all are a small minority. Even small contributions can play a significant role in maintaining family solidarity and the elders' social status. Despite this encouraging pattern of support, between 12 and 37 per cent of elders in the lower strata were currently vulnerable, that is, subject to low levels of support that left them publicly and disreputably reliant on charity.

Migration is one of several factors that reduce the networks of contributing children. It acts in conjunction with long-term status differentials, and with the tendency of networks to reinforce status differences. In Rao-Rao, migration is associated with greater opportunities, the benefits of which flow back to the community and disproportionately favour the rich over the poor. In Kidul, and to a lesser extent in Citengah, migration is a regular feature of most family networks, in which ‘away’ children as well as those nearby are likely to make contributions. In all three communities, vulnerability is most likely where there is an inter-generational transmission of poverty; this either pushes poor children out of family networks and the community or, if they stay, prevents them from providing effective support.

That said, three village studies cannot provide a comprehensive answer to the potentially worrying aggregate picture posed at the beginning of this paper. Studies of older people in poorer hamlets, such as those left behind by immigrants to Kidul and Rao-Rao, or those in communities in which commercial agriculture has removed most livelihoods (Breman and Wiradi 2002), may tell a different story. It is nonetheless clear that the impacts of migration, as they affect the outcomes of older people's lives, cannot be understood in terms of discrete unidirectional movements as reported in standard statistical sources. Older people need to be broken down into sub-groups defined by the socio-economic strata and family networks to which they belong. The differential impact of migration on local experience and perceptions of vulnerability can then be examined in terms of the dynamics of network size and characteristics which enable supportive relationships to continue between some younger migrants and their elders, whilst breaking down network continuity amongst others.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Elisabeth Schröder-Butterfill and Peter van Eeuwijk for comments on earlier versions of this paper. Responsibility for the interpretation rests with the author.

Footnotes

Ageing in Indonesia is an anthropological and demographic field study that is being conducted by Elisabeth Schröder-Butterfill (in Kidul, East Java), Edi Indrizal and Tengku Syawilafithry (in Rao-Rao, West Sumatra), and Vita Priantina Dewi and Haryono (in Citengah, West Java) under the direction of the author. The paper draws on our collective discussion of the findings from the three sites, and has been much improved by my colleagues' insights. The study began in 1999, and further field observations and surveys are being carried out in 2005–6. We are grateful to The Wellcome Trust for its generous support of the project. An earlier version of the paper was presented at Old-Age Vulnerabilities: Asian and European Perspectives, a workshop held at Brawijaya University, Malang, East Java, 8–10 July, 2004.

Older people who have never had children, or whose children have all died, may nonetheless be able to build networks that include ‘children’ in the extended sense used here, and are therefore included in this analysis. The vulnerability of childless older people who have not been able to build networks is discussed elsewhere (Schröder-Butterfill and Kreager 2005). Attention is drawn to the large contrast between the network approach taken here, and analyses based on household residence. Vulnerability and poverty are often associated in western societies with older couples or individuals living alone. Residence, of course, is not adequate as a proxy for vulnerability, precisely because of the differential affects of networks. An approach to vulnerability based on, say, widows and couples living alone in the communities described in this paper, would inevitably confound those with and without good support networks.

Mauss's (1925) classic observations on the structure of exchange, and on what might be called hidden agendas of reciprocity, are pertinent here. The fact of exchange, in his view, is of much greater importance than the objective value of the material items or services exchanged, since the prime value at issue is a continuing relationship, not an event. Gifts, in other words, are never disinterested; the relationships they sustain are premised in continuing moral and economic obligations. Gifts serve at once as signs of appropriate parental, filial or other familial membership, and they commit participants not only to an ongoing set of exchanges, but to maintaining status and position in a network of relationships. The term ‘transfer’ is unfortunate when applied to such relationships, as are approaches attempting to treat parent-child exchanges without reference to the wider web of relations of which they are but part. An excellent development of Mauss's perspective in Southeast Asia was by Li (1989).

The prevalence of the ‘some from each’ pattern indicates a need for caution, at least in Indonesia, regarding conventional household survey methodologies. Inquiries confined to household-based income or dyadic exchanges between households capture only a small fraction of the support networks relevant to the elderly. Life history and in-depth interview data, used here in conjunction with surveys, make clear that, in addition to the redistributive aspects of networks, there is fluctuation over time in the amounts and kinds of support that children provide, and that it is often as responsive to their changing resources and other commitments as to elders' needs.

References

- Ananta A, Anwar EN, Suzenti D. Some economic-demographic aspects of ‘ageing’ in Indonesia. In: Jones G, Hull T, editors. Indonesia Assessment: Population and Human Resources. Canberra: Australian National University; 1997. pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ananta A, Anwar EN, Miranti R. Age-Sex Pattern of Migrants and Movers: A Multilevel Analysis on an Indonesian Dataset. Singapore: National University of Singapore; 2001. (Asian MetaCentre Research Paper 1). [Google Scholar]

- Arifianto A. Public Pension Reform in Indonesia: Issues and the Way Forward. Jakarta: SMERU Research Institute; 2004. Unpublished Report. Available online at http://www.smeru.or.id. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank . Assessment of Poverty in Indonesia. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Biro Pusat Statistik . Penduduk Indonesia: Hasil Sensus Penduduk 1990 [The Indonesian Population: Results of the 1990 Population Census] Jakarta: Biro Pusat Statistik; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Breman J, Wiradi G. Good Times and Bad Times in Rural Java. Leiden, The Netherlands: KITLV Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Firman T. Patterns and trends of urbanisation: a reflection of regional disparities. In: Jones G, Hull T, editors. Indonesia Assessment. Canberra: Australian National University; 1997. pp. 101–17. [Google Scholar]

- Guest P. Labor Allocation and Rural Development. Boulder, Colorado: Westview; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hart G. Power, Labour and Livelihood: Processes of Change in Rural Java. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo G. Circular migration in Indonesia. Population and Development Review. 1982;8(1):59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo G, Champion A, Lattes A. Toward a new conceptualisation of settlements for demography. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(2):277–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hüsken F, White B. Java: social differentiation, food production, and agrarian control. In: Hart G, Turton A, White B, editors. Agrarian Transformations: Local Processes and the State in Southeast Asia. Berkeley, California: University of California Press; 1989. pp. 235–65. [Google Scholar]

- Indrizal E. Problems of elderly without children: a case study of the matrilineal Minangkabau, West Sumatra. In: Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Oxford: Berghahn; 2004. pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organisation (ILO) Social Security and Coverage for All: Restructuring the Social Security Scheme in Indonesia. Issues and Options. Jakarta: ILO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jay R. Javanese Villagers: Social Relations in Rural Modjokuto. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. Marriage and Divorce in Islamic Southeast Asia. Singapore: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kato T. Matriliny and Migration: Evolving Minangkabau Traditions in Indonesia. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella K, Taueber CM. An Aging World II. Washington DC: Bureau of the Census, United States Government Printing Office; 1993. (International Population Report P25/92-3). [Google Scholar]

- Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E. Gaps in the family networks of older people in three rural Indonesian communities. Oxford: Oxford Institute of Ageing; 2005. (Working Paper 305). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. Malays in Singapore: Culture, Economy and Ideology. Singapore: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Willis RJ. Motives for intergenerational transfers: evidence from Malaysia. Demography. 1997;34(1):115–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss M. Essai sur le don, forme archaique de l'échange [The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies] New York: Norton; 1925. translation 1967. Translator, I. Cunnison. [Google Scholar]

- Muhidin SS. Regional dimension of migration by education and employment: the case of Indonesia; Immigration, Societies and Modern Education; 31 August–3 September; Singapore: Centre for Advanced Studies, National University of Singapore; 2000. Paper presented at the international conference. [Google Scholar]

- Penny D, Singarimbun M. Population and Poverty in Rural Java: Some Economic Arithmetic from Sriharjo. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 1973. Cornell International Agricultural Development Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill E. Ageing in Indonesia: A Socio-Demographic Approach. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2002. Unpublished D.Phil. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill E. Intergenerational family support provided by older people in Indonesia. Ageing & Society. 2004;24(4):1–34. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X0400234X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill E, Kreager P. Actual and de facto childlessness in old age: evidence and implications from East Java, Indonesia. Population and Development Review. 2005;31(1):19–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaan E. Labour Circulation and Socio-Economic Transformation: The Case of East Java, Indonesia. Groningen, The Netherlands: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sumartono . Social stratification and the election of a village head. In: Holzner BM, editor. Steps Towards Growth: Rural Industrialization and Socioeconomic Change in East Java. Leiden, The Netherlands: DSWO Press; 1995. pp. 267–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tambunan TTH, Purwoko B. Social protection in Indonesia. In: Adam EM, von Hauff M, John M, editors. Social Protection in Southeast and East Asia. Singapore: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; 2002. pp. 21–73. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force for Social Security Reform . Rancangan Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Tentang Sistem Jaminan Sosial [Draft Bill for a Social Security System] Jakarta: Republic of Indonesia; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division . World Population Ageing, 1950-2050. New York: United Nations Organisation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sterren A. A history of sexually transmitted diseases in the Indonesian archipelago since 1811. In: Lewis M, editor. Sex, Disease and Society: A Comparative History of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV/AIDS in Asia and the Pacific. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood; 1997. pp. 203–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Sanso P. They don't need it, and I can't give it: filial support in South India. In: Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: Asian and European Perspectives. Oxford: Berghahn; 2004. pp. 77–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DL. Factory Daughters: Gender, Household Dynamics and Rural Industrialization in Java. Berkeley, California: University of California Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]