Abstract

Endothelial surface microstructures have been described previously under inflammatory conditions however they remain ill-characterised. In this study CXCL8, an inflammatory chemokine, was shown to induce the formation of filopodia-like protrusions on endothelial cells; the same effects were observed with CXCL10 and CCL5. Chemokines stimulated filopodia formation by both microvascular (from bone marrow and skin) and macrovascular (from human umbilical vein) endothelial cells. Use of blocking antibodies and degradative enzymes demonstrated that CXCL8-stimulated filopodia formation was mediated by CXCR1 and 2, Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines (DARC), heparan sulphate and syndecans. Heparan sulphate was present on filopodial protrusions appearing as a meshwork on the cell surface, which colocalised with CXCL8, and this glycosaminoglycan was 2,6-O and 3-O-sulphated. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that CXCL8 stimulated filopodial and microvilli-like protrusions that interacted with leukocytes prior to transendothelial migration and removal of heparan sulphate reduced this migration. ITRAQ mass spectrometry showed that changes in the levels of cytoskeletal, signalling and extracellular matrix proteins were associated with CXCL8-stimulated filopodia/microvilli formation; these included tropomyosin, fascin and Rab7. This study suggests that chemokines stimulate endothelial filopodia and microvilli formation, leading to their presentation to leukocytes and leukocyte transendothelial migration.

Introduction

Endothelial cells (ECs) are major cells involved in the immune response and inflammation. They play a role in the regulation of leukocyte extravasation, angiogenesis, cytokine production, protease and extracellular matrix synthesis, vasodilation and blood vessel permeability, and antigen presentation (1). In inflammatory conditions, such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ECs have a predominant role undergoing activation, expressing adhesion molecules and presenting chemokines, which leads to leukocytes migrating from the blood into the tissue.

Although the method of leukocyte extravasation has been widely studied little is known about the function of EC surface microstructures in leukocyte migration. There have been several reports on the formation of filopodial and microvillous structures by ECs under inflammatory conditions. EC filopodia form during angiogenesis and in response to the inflammatory mediators TNFα and bradykinin (2-4). Endothelial projections have been shown to be prominent in the inflamed synovium of arthritic patients (5) and microvillous structures are associated with ECs in atherosclerotic plaques (6) and in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE)(7) suggesting their relevance in inflammatory disease. When human skin was injected with the chemokine CXCL8 after 30 minutes numerous protrusions of the EC luminal membrane were visible and leukocyte extravasation occurred (8). Similarly, when CXCL8 was injected into human and rabbit skin, immuno-electron microscopy showed that the chemokine localised on the luminal EC surface where it was particularly concentrated on projections and microvillous processes (9). The concentration of chemokine on these structures suggested that the chemokine binding sites, such as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and potentially Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines (DARC), may also be concentrated on these microstructures (9,10). Such data imply that chemokines are presented to blood leukocytes on EC microstructures leading to leukocyte transendothelial migration. In addition, Feng et al (11) injected the chemoattractant N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (FMLP) intradermally into guinea pigs and found that the vascular endothelium developed increased surface wrinkling and neutrophil recruitment occurred. Therefore EC protrusive microstructures appear to be involved in leukocyte extravasation but little is known concerning their composition, the receptors involved in their formation and the associated intracellular changes.

Leukocyte diapedesis is a critical component for immune system function and inflammatory responses. This occurs by the migration of leukocytes either directly through individual ECs (transcellular) or between them (paracellular) (12). The endothelial cytoskeleton plays an essential role in transcellular migration, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 enriched endothelial projections termed ‘transmigratory cups’ or ‘docking structures’ have been shown to partially embrace transmigrating leukocytes both in vivo and in vitro, these structures may serve as guidance structures to facilitate the initiation of both trans and paracellular diapedesis (12-14).

The current study examined the formation of EC surface protrusions by micro- and macrovascular ECs in response to various chemokines. The composition of their chemokine binding molecules, the receptors involved in their formation and their association with transmigrating leukocytes have been investigated. Furthermore mass spectrometry and western blot analysis was performed on chemokine-stimulated ECs to determine the intracellular changes that occurred related to EC microstructure formation. The results suggest that by chemokines stimulating formation of filopodial and microvillous protrusions they may enhance their own presentation.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

For comparisons of endothelial microstructure formation between cells, various ECs were used: immortalised human bone marrow endothelial cells (HBMECs), donated by Prof BB Weksler (15), maintained in DMEM-F12 (Lonza, Wokingham, UK), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) extracted from umbilical cords following informed consent, maintained in 0.1% gelatin-coated tissue culture flasks in EGM-2 (Lonza), and human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs)(Lonza) maintained in EGM-2-MV (Lonza), all containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and 50U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza). All ECs were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator with the addition of 5% CO2 and grown to around 70% confluence before being used in the following experiments.

Endothelial cell activation

ECs were activated by incubating monolayers with recombinant human CXCL8 (IL-8), CXCL10 (IP-10) or CCL5 (RANTES) (Peprotech EC, London, UK) at concentrations ranging from 0-500ng/ml in serum free medium for 30 minutes at 37°C. They were also activated with cytokines recombinant human TNFα and IFNaγ (both at 100ng/ml; Peprotech) for 16 hours 37°C. Negative controls contained no chemokines or cytokines.

The effect of chemokine on filopodial protrusion formation was determined by counting the total number of cells per random field of view (n=10 fields of view) at ×200 magnification and the number of those cells that had formed the microstructures. The percentages of cells with filopodial protrusions were then calculated and mean values ± SE determined.

Blocking and degrading CXCL8 binding sites

Prior to stimulation with CXCL8, the cells were treated with heparanases and antibodies using titrations; concentrations ranged from 5-20U/ml for heparinase I (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK); 0.5-2U/ml for heparinase III (Sigma-Aldrich); 0.5-2μg/ml for anti-CXCR1 (R&D Systems, Oxfordshire, UK); 2.5-10μg/ml for anti-CXCR2 (R&D Systems); 50-400ng/ml for anti-DARC (donated by Professor D Blanchard, University of Nantes, France); 2.5-10μg/ml for both anti-syndecan-3 and -4 (donated by Professor G David, University of Leuven, Belgium). The cells were then treated with the optimum concentrations of heparinase I (10U/ml) or heparinase III (2U/ml) for 1.5 hours at 37°C to remove the HS. To block CXCL8 binding sites ECs were treated with: mouse monoclonal blocking antibodies (IgG2A) to human CXCR1 (optimum concentration 2μg/ml) or human CXCR2 (2.5μg/ml) for 30 minutes at 37°C, mouse IgG2A (Dako, Cambridgeshire, UK) was used as an isotype control; a mouse monoclonal antibody (IgG1) to human DARC Fy6 (2C3, 50ng/ml) for 30 min at 37°C, mouse IgG1 (Dako) was used as an isotype control. To examine syndecan-3 and -4 internalisation the cell monolayers were treated with cell culture medium at 4°C or 37°C in the presence of mouse monoclonal antibodies to syndecan-3 and -4 (1C7 and 8G3; both at 5μg/ml) or mouse IgG1 (isotype control) and maintained at this temperature for 30 min (in an atmosphere without 5% CO2). In addition, control cells were not treated with blocking antibodies or enzymes and were without chemokine-stimulation; in addition, cells were left untreated yet with CXCL8 (100ng/ml) stimulation for 30 minutes. Following the treatments, the cells were fixed with ice cold 1:1 acetone-methanol in the absence of permeabilisation before being analysed with phase-contrast microscopy. The percentage of ECs with filopodial protrusions was determined as described previously.

Immunofluorescence

1×105 HBMECs in 500μl serum free DMEM-F12 were seeded into 8-well chamber slides (Cole-Parmer Instrument Company, London, UK) and incubated at 37°C for 48-72 hours until the levels of confluence achieved as above. Immunofluorescence of heparan sulphate (HS) was performed using phage display derived single chain antibodies with a VSV-G tag (donated by Professor T Kuppevelt, University of Nijmegen, Netherlands). CXCL8-stimulated (100ng/ml for 30 minutes) or unstimulated ECs were incubated with AO4BO8, which recognises the GlcNS6S-IdoUA2S-GlcNS6S epitope (16) or HS4C3, which recognises the 3-O-sulphation epitope (17) (both at 0.5μg/ml in 2% BSA/PBS), at room temperature for 1.5 hours. Cells were washed three times for five minutes in PBS. Primary antibodies were detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody (IgG1) to the VSV-G tag (clone PD54; 1:100 in 2% BSA/PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG1 (1:400 in 2% BSA/PBS; Invitrogen) and washed before being counterstained with DAPI for three minutes. The cells were mounted with Hydromount (Fisher Scientific) or Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen) and visualised with a light microscope (Olympus IX51) and analysed with Cell^F software; or a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5) and analysed with a Leica Application Suite. PBS was used in place of the phage display antibodies as a negative control and mouse IgG1 (0.5μg/ml) as an isotype control.

For double labelling, the experiment was repeated except that goat anti-human CXCL8 (5μg/ml in 2% BSA/PBS; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) was added with anti-HS, and Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat IgG (1:400 in 2% BSA/PBS; Invitrogen) added with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG1 (as above). Goat IgG (5μg/ml in 2% BSA/PBS; Dako) was used instead of primary anti-CXCL8 antibody as control.

CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs were pre-treated with heparinase I or III (as described previously) prior to staining as above. The expression of the AO4BO8 and HS4C3 epitopes (+/− heparinase treatment) was quantified by counting the total number of cells per field of view (from 10 fields of view) and the number of those cells that had positively stained filopodia An EC was scored positive when the HS-positive filopodia/meshwork was associated with it. The percentage of cells expressing the epitopes on the filopodia was calculated and means ± SE were determined.

Transendothelial Migration

Leukocyte isolation

4ml of blood was obtained, after informed consent, from normal healthy volunteers in EDTA containing tubes. To remove erythrocytes blood was added to 16ml ice cold ammonium chloride and incubated on ice for 15 minutes after mixing. The blood solution was centrifuged at 1000RPM for 10 minutes at 4°C, the supernatant was removed and the solution resuspended in 15ml sterile HBSS. After further centrifugation the supernatant was removed and the leukocytes resuspended in HBSS to a final concentration of 1×106 cells/ml.

Neutrophil migration through an endothelial layer

2×105 ECs in 500μl medium were cultured on 3μm pore transwell filters (Millipore UK Ltd, Watford, UK) in 24-well flat bottom micro-plates (SLS, Nottingham, UK), with 800μl medium in the basal chambers, until a monolayer was formed (24-48 hours at 37°C). The solution in the apical chamber was replaced with 500μl fresh serum free DMEM-F12 and the solution in the basal chamber was replaced with a solution of serum-free medium containing 100ng/ml CXCL8, for controls serum-free medium containing no CXCL8 was used. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes for filopodia/microvilli formation to occur. 5×105 leukocytes were then added to the apical chambers, followed by incubation at 37°C for another 30 minutes in continued presence of CXCL8. Initial experiments compared 30 and 60 minute migration times and 30 minutes was found to be optimal and sufficient for 30% of neutrophils to migrate across microvascular HBMECs. These time points are in general agreement with those reported for CXCL8 stimulated neutrophil migration across human umbilical vein endothelial cells (18). Neutrophil migration was quantified using flow cytometry, as described below.

Inhibition of neutrophil migration

Endothelial monolayers were pre-treated with 500μl serum free medium in the apical chambers, containing either 10U/ml heparinase I or 2U/ml heparinase III for 1.5 hours at 37°C, the enzymes were removed prior to CXCL8 stimulation (as above). As a control, neutrophils were added to a CXCL8-stimulated endothelial monolayer that had not been treated with any enzymes. Neutrophil migration was quantified by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Following leukocyte transendothelial migration the solutions from the basal chambers were centrifuged at 1400RPM for 4 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the pellets resuspended in 150μl HBSS, the solutions were analysed on a flow cytometer (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Oxfordshire, UK). A solution of the original leukocyte preparation was analysed primarily so gates could be applied on the neutrophil population, following this the migrated samples were analysed and the numbers of neutrophils in each well determined. The percentage of neutrophils that had migrated was calculated and means ± SE were determined.

After the medium containing migrated neutrophils was removed from the transwells, the basal chamber was stained by haematoxylin and eosin to detect neutrophils that may have adhered to the plastic surfaces of the basal chambers, thereby artificially reducing the numbers collected for flow cytometry. Microscopy revealed no such adherence to the plastic surfaces of the lower chamber.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy analysis was performed on HBMEC monolayers grown on 3μm pore transwell filters, in the presence and absence of leukocytes, as described above. HBMECs were stimulated with 100ng/ml CXCL8, or left unstimulated, prior to the addition of the leukocytes. The leukocytes were left to migrate for 15 or 30 minutes at 37°C before the filters were washed with PBS and fixed for 2 hours at room temperature in 0.1M sodium cacodylate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2mM CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich) (buffer A) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich); the filters were removed from the inserts and stored in buffer A containing 0.1% glutaraldehyde. The samples were washed three times for five minutes in buffer A, before post-fixation using 0.1% osmium tetroxide in buffer A for 1 hour. The samples were then washed again and stored overnight in 70% ethanol. Samples were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (80% and 100%) for 15 minutes followed by 15 minutes in 100% dry ethanol prior to embedding with Spurr’s resin and dry ethanol. 100nm thick sections were cut using a Leica Ultracut microtome and stained with 2% lead citrate and 2% uranyl acetate prior to visualisation with a JEOL electron microscope.

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry was performed as described in Fuller et al (19) with some modifications.

Cell extraction

15 × 106 HBMECs (P24) were activated with 100ng/ml CXCL8 for 0.5 hours, 6 hours, or 16 hours at 37°C, unstimulated cells were used as a control. The cells were detached, centrifuged, washed with PBS and incubated in four volumes of 6M urea, 2M thiourea, 2% CHAPS and 0.5% SDS, in water, then sonicated before being stored at −80°C overnight.

Protein precipitation

Four volumes of ice-cold acetone were added to each extract then stored overnight at −20°C. The precipitated protein was then isolated by centrifugation of the extracts at 13,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C, insoluble cell debris was removed and discarded and the pellets were air-dried and resuspended in 6M urea in 50mM TEAB. The protein concentration for each sample was determined using a Bradford assay.

Labelling and digestion of cell extracts

The cysteines were reduced and blocked using reagents provided with the iTRAQ® kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). The samples were diluted to less than 1M urea with dissolution buffer, followed by incubation overnight at 37°C with trypsin (2μg per 100μg sample). The samples were then dried down in a vacuum centrifuge and labelled with iTRAQ reagents according to the protocol in the iTRAQ kit; the 114 tag represented the control, and 115,116 and 117 tags were the 0.5, 6 and 16 hour CXCL8-treated samples respectively.

Ion exchange of iTRAQ-labelled peptides

iTRAQ peptides from the 4 samples were pooled and re-dissolved in 2.4ml of 10mM phosphate in 20% acetonitrile (buffer A). The whole sample was loaded onto an SCX column (5μm particles; 300-Angstrom pores; Fisher Scientific) at 400μl/minute. The column was washed at 800μl/minute with buffer A until the baseline returned to zero. A gradient was run at 400μl/minute from 0-50% 10mM phosphate and 1M NaCl in 20% acetonitrile (buffer B) over 25 minutes followed by a ramp up from 50% to 100% buffer B over 5 minutes. 100% buffer B was held for 5 minutes (400μl/minute) before equilibrating the column for 10 minutes with buffer A (400μl/minute).

Protein identification by mass spectrometry

Fractions were re-dissolved in 25μl 2% acetonitrile, 98% water, and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (buffer C) prior to being loaded onto an Acclaim® Pepmap™ C18 trapping column (Dionex Ltd, Surrey, UK); the fractions were then eluted onto an Acclaim® Pepmap™ C18 analytical column (Dionex Ltd). The column was then washed in buffer A for 15 minutes before the peptides were eluted using a gradient from 0-30% of buffer B over 90 minutes, then 30-60% of buffer B over 35 minutes, followed by a final elution at 90% of buffer B for 10 minutes. The column was then washed and equilibrated in buffer A for 10 minutes (UltiMate 3000; Dionex Ltd). A blank sample (buffer A) was run in between each fraction to minimize any carry over and the loading of samples was randomised. Fractions were collected at 10s intervals using a Probot microfraction collector (Dionex Ltd) with 3mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) consisting of 70% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at a flow rate of 1.2μl/minute. The fractionated peptides were then analysed using a Bruker Ultraflex II MALDI TOF/TOF.

Mass spectrometry iTRAQ analysis

The peptide count is defined as the number of peptides with unique sequences matching the selected protein. The iTRAQ ratio is the level of protein in that sample (numbered 115,116 and 117) when compared to the level of protein in the control sample (numbered 114). The score is based on the total ion score which is a score calculated by weighting ion scores for all individuals matched to a given protein, and is a measure of signal strength. The confidence interval (C.I.%) is the confidence that the peptides found are part of the protein identified.

SDS Page and Western Blotting

Electrophoresis was performed using the BioRad Mini Protean III gel system. Slab 6-12% acrylamide gels (0.75mm thick) were prepared from stock solutions. Protein samples from mass spectrometry cell extracts were used, protein concentrations determined and 0.0001% (w/v) bromophenol blue added. 10-20μl samples were loaded onto gels and electrophoresis was performed in electrophoresis buffer at 160 volts for 1-2 hours.

Following electrophoresis, gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a wet-blot system with transfer buffer. Proteins were transferred for 1 hour at 90 volts. After blotting, membranes were incubated in TBST containing 10% non-fat milk (dilution buffer) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were incubated, for 1 hour at room temperature, in dilution buffer containing the following primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal IgG1 to human tropomyosin (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit polyclonal to human Rab7 (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse monoclonal IgG1 to human fascin (1:200; Abcam) or rabbit polyclonal to human GAPDH (1:2000; 2B Scientific, Upper Heyford, UK). Positive antibody bands were visualised by development with either peroxidase-labelled goat anti-mouse Ig or peroxidase-labelled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000 in dilution buffer) and detected using a chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare Ltd, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Intradermal Injection of CXCL8 in Rabbits

Human recombinant CXCL8 was injected intradermally, 1μg/site, in Chinchilla rabbits (n=3; Charles River, Wilmington, USA); duplicate biopsies of the sites were taken 4 hr, 2 hr, 1 hr, 1/2 hr, and immediately after the injection (0 hr). Vehicle-injected sites sampled at the same time points and non-injected skin served as controls. Biopsies were processed for transmission electron microscopy as described above.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Graph-pad Prism 5. To determine statistical significance, since all the data showed a normal variation, one-way ANOVAs were performed followed by Tukey post-test comparisons to establish significant variations between individual sample groups; a p value of <0.05 was deemed as significant. For mass spectrometry the iTRAQ data of CXCL8 treated and untreated HBMECs were compared by ANOVA using data for each peptide for a given protein.

Results

Chemokine binding and the microstructure of endothelial cells

ECs were grown on plastic in the presence of serum until approximately 70% confluence and this enabled the visualisation of the cell periphery. They were then incubated with or without chemokines in serum-free media. In the presence of chemokines using phase contrast filopodial protrusions (also named ‘filopodia’) were seen at the cell periphery, occurring within 30 minutes (figure 1A-B). Time lapse video imaging showed that these were dynamic remodelling structures, extending and retracting rapidly following addition of the chemokine (data not shown). The inclusion criteria for these microstructures were: one or more finger-like process that extended from the cell, measuring up to 10μm in length and 0.2-1μm in width and were not lamellipodia. These filopodial protrusions frequently contacted adjacent cells even extending over their surfaces. Cells were excluded that had a normal rounded or spindle-like morphology and had no extending cell processes. When the ECs were treated with chemokines for 6 and 16 hours filopodia were still present. The cell lines used in this model were HBMECs, HMVECs and HUVECs. The ECs were treated with CXCL8, CXCL10 and CCL5 at concentrations varying from 0-500ng/ml. For each chemokine treatment in all three cell lines, there were significant changes in the percentage of cells that formed filopodia with increasing concentrations of chemokine (p=<0.0001) (figure 1C).

Figure 1. Chemokine-stimulated formation of filopodial protrusions.

Human bone marrow (HBMEC), human dermal microvascular (HMVEC) and human umbilical vein (HUVEC) endothelial cells were stimulated with varying concentrations of chemokine (or no chemokine for the negative controls). After 30 minutes at 37°C, the percentage of cells with filopodial protrusions was determined using phase contrast microscopy at a magnification of ×200.

(A) is an example of a control HBMEC in the absence of CXCL8 showing lack of filopodia.

(B) is in the presence of CXCL8 (100ng/ml) showing cells with filopodial protrusions at the cell periphery (examples are arrowed). Bar = 25μm in A and B.

(C) Endothelial cells were treated with varying concentrations of CXCL8, CXCL10, CCL5, or no chemokine (control) and the percentage of cells with filopodial protrusions was calculated. Data show the percentage mean ± standard error (SE) from n=10 fields of view and are representative of three independent experiments, *p=<0.05 ***p=<0.0001 compared to untreated controls.

HBMECs

The percentage of HBMECs that formed filopodial protrusions in the absence of chemokines ranged from 3.8±2.8% to 11.2±0.8%. All concentrations of CXCL8, CXCL10 and 1-200ng/ml CCL5 caused a significant increase in the percentage of cells with filopodia compared to the control (p=<0.0001) (figure 1C). The percentage of cells that formed these microstructures ranged from 24.7±1.8% with 1ng/ml CXCL8 up to 51.6±1.6% with 200ng/ml CXCL8. With CXCL10 the percentage of cells with filopodia increased from 21.1±1.3% (1ng/ml) up to 46.5±2.7% (200ng/ml). In the presence of CCL5 the percentage of cells with filopodia ranged from 23.6±1.8% (1ng/ml) to 28.0±3.6% (100ng/ml). At higher chemokine concentrations the amount of these microstructures reduced such that at 500ng/ml, CCL5 had no significant effect (figure 1C). There were significant reductions in the percentage of filopodia at higher chemokine concentrations. CXCL10 caused the percentage to decrease from 46.5±2.7% (200ng/ml) to 37.3±1.26% with 500ng/ml (p=<0.0001). In the presence of CCL5 there were significant reductions in filopodia formation from 28.0±3.6% (100ng/ml) and 23.6±1.7% (200ng/ml) to 12.8±0.8% with 500ng/ml (p=<0.0001). With CXCL8 stimulation there was no significant reduction in the percentage of these structures formed at higher chemokine concentrations although at 500ng/ml the percentage was slightly lower (51.5±1.6% with 200ng/ml to 43.6±2.1% with 500ng/ml).

Cells were also treated with inflammatory cytokines to activate them in order to examine their effects on filopodial protrusion formation. HBMECs treated with TNFα and IFNγ (both at 100ng/ml) for 16 hours promoted filopodia formation compared to no cytokine control (p<0.0001), amounting to 45±3.3% of HBMECs forming these structures. Addition of CXCL8 (100ng/ml) for 30 minutes after TNFα/IFNγ activation further enhanced filopodia formation to 53±3.5%, although not significantly. Overall TNFα/IFNγ activation of HBMECs did not significantly stimulate filopodia formation compared to use of CXCL8 alone (100ng/ml for 30 minutes) which amounted to 49±2.6% (figure 1C).

The effects of the presence of serum on microvilli formation was examined. Control cells that were incubated in the presence of serum (10% FBS) and no chemokine had low levels of filopodia (9 ±1.8%) being similar to those obtained in the absence of serum and no chemokine (ranging 3.8-11.2% Figure 1C). Addition of 100ng/ml CXCL8 for 30 minutes in the presence of serum stimulated filopodia formation to 30±3.3% (p=0.0003). Therefore filopodia formation does not appear to occur due to exposure of ECs to a serum-free environment in combination with chemokine.

HMVEC

The percentage of HMVECs that formed filopodia in the absence of chemokines ranged from 4.2±0.2% to 4.5±0.3%. All concentrations of CXCL10 and 10-500ng/ml CXCL8 and CCL5 caused a statistically significant increase in the percentage of cells with filopodia (p=<0.0001-<0.01); 1ng/ml CXCL8 and CCL5 had no significant effect (figure 1C). The percentage of cells that formed filopodia increased from 6.3±10.3% with 1ng/ml CXCL8 up to 18.1±1.0% with 200ng/ml. With CXCL10 the percentage of cells with these microstructures ranged from 9.9±0.5% (1ng/ml) up to 16.3±0.5% (10ng/ml). In the presence of CCL5 the percentage of cells with filopodia increased slightly from 5.5±0.3% (1ng/ml) up to 13.1±0.7% (200ng/ml). The percentage of filopodia formed showed changes at higher chemokine concentrations. In the presence of 500ng/ml CXCL8 the filopodia percentage was significantly reduced from 18.1±1.0% (200ng/ml) to 13.0±0.7% (p=<0.0001). Similarly with 500ng/ml CCL5, the percentage of filopodia reduced significantly from 13.1±0.7% (200ng/ml) to 7.4±0.5% (p=<0.0001), almost a 2-fold reduction in these structures. CXCL10 showed significant reductions in filopodia when the chemokine concentrations went above 10ng/ml. There were significant differences between 10 and 200ng/ml (16.3±0.5% to 10.6±0.4%), 10 and 500ng/ml (16.3±0.5% to 11.5±0.7%), 100 and 200ng/ml (14.5±0.6% to 10.6±0.4%) and 100 to 500ng/ml (14.5±0.6% to 11.5±0.7%) (all <0.0001).

HUVECs

The percentage of HUVECs that formed filopodia in the absence of chemokines ranged from 3.5±0.6% to 4.1±0.7%. All concentrations of CXCL10 and 10-500ng/ml of CXCL8 and CCL5 caused a significant increase in the percentage of cells with these structures (p=<0.0001); 1ng/ml CXCL8 and CCL5 had no significant effect (figure 1C). The percentage of cells that formed filopodia ranged from 4.9±0.4% with 1ng/ml CXCL8 up to 18.9±0.8% with 500ng/ml CXCL8. With CXCL10 the percentage of cells with filopodia increased from 14.7±0.6% (1ng/ml) to 21.9±1.1% (200ng/ml). In the presence of CCL5 the percentage of cells with the structures changed from 5.1±0.3% (1ng/ml) to 19.9±1.0% (200ng/ml).

There were significant differences in filopodia formation at higher concentrations of CXCL10 and CCL5; CXCL8 caused no significant reduction at higher concentrations. In the presence of CCL5 there was a reduction in filopodia formation, from 19.8±1.6% with 100ng/ml and 19.8±1.0% with 200ng/ml to 12.5±0.8% with 500ng/ml (p=<0.0001). CXCL10 showed a similar pattern, reducing from 21.4±0.9% with 100ng/ml and 21.9±1.1% with 200ng/ml to 15.6±0.7% with 500ng/ml (p=<0.0001).

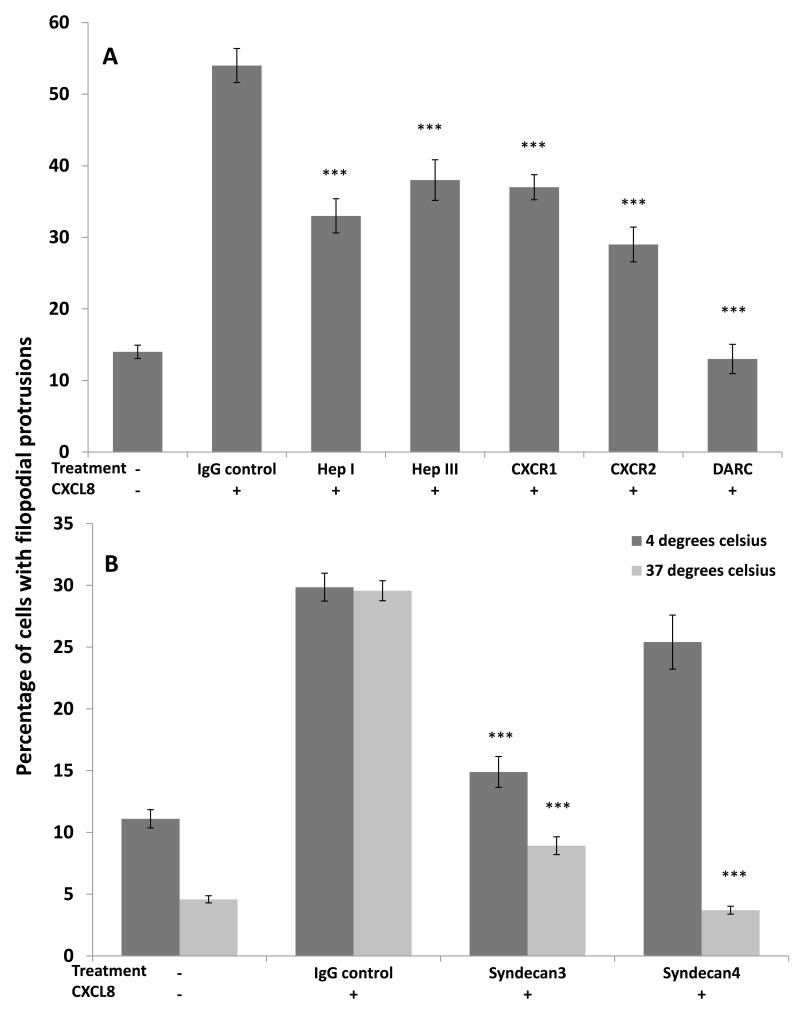

Receptors involved in filopodial protrusion formation

In order to determine which receptors were involved in the formation of filopodial protrusions, CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs were pre-treated with blocking antibodies to chemokine receptors or enzymes that cleave the GAG heparan sulphate (HS) (figure 2A). With no blocking treatment and no chemokine stimulation, the percentage of cells that formed filopodia was 14±0.9%. Treating the cells with CXCL8, in the presence of IgG control, caused an increase in the percentage of ECs with these structures up to 54± 2.4%. When the cells were treated with heparinase I the percentage of cells with filopodia was significantly reduced to 33±2.4% (p=<0.0001) when compared to the CXCL8-treated control; with heparinase III the percentage of cells with filopodia was 38±2.8%, again significantly different to the control (p=<0.0001); with anti-CXCR1 the percentage was 37±1.8% (p=<0.0001); with anti-CXCR2 the percentage decreased to 29±2.4% (p=<0.0001). When heparanase I and anti-CXCR2 were used together the percentage of cells with filopodia reduced further to 9±0.9% (p=<0.0001). Following treatment with anti-DARC the proportion of cells that formed filopodia was decreased to 13±2.1% (p=<0.0001) which was not significantly different to that of the negative control (no blocking treatment and no chemokine stimulation). All the other single treatments were significantly higher than the negative control (p=<0.0001). Similarly, there were differences between the percentages of filopodia formed after blocking with anti-DARC compared to the other treatments used (Hep I, Hep III, anti-CXCR1 or anti-CXCR2)(p=<0.0001).

Figure 2. HBMEC filopodial protrusion formation after blocking or degrading CXCL8 binding sites.

(A) CXCL8-stimulated cells (100ng/ml) were pre-treated with anti-CXCR1 (2μg/ml), anti-CXCR2 (2.5 μg/ml), anti-DARC (50ng/ml), heparinase I (10U/ml) or heparinase III (2U/ml). As a positive control endothelial cells were treated with CXCL8 in the presence of mouse IgG, as a negative control endothelial cells were left unstimulated. ***p=<0.0001 compared to CXCL8-treated IgG control. Data show the percentage mean ± standard error (SE) of n=10 fields of view and are representative of three independent experiments.

(B) CXCL8-stimulated endothelial cells were treated with anti-syndecan-3 or anti-syndecan-4 (both 5μg/ml) and mouse IgG as a control; unstimulated cells were also used to determine background filopodia formation. The assay was performed at both +4°C and +37°C prior to endothelial cells being fixed and the percentage of cells with filopodia determined using phase contrast microscopy. ***p=<0.0001 compared to CXCL8-treated IgG control. Data show the means ± standard errors (SE) of the percentage of cells with filopodia in 10 fields of view (at ×200 magnification) from one experiment representative of two independent experiments.

Major HS proteoglycans (HSPGs) found to be expressed by HBMECs were syndecan-3 and -4 (data not shown). HBMECs were incubated with blocking antibodies to syndecan-3 and -4 at temperatures of either 4°C or 37°C prior to incubation with CXCL8, to determine if these HSPGs were being internalised or not upon binding (figure 2B). When incubated at 4°C the percentage of ECs that formed filopodia with no CXCL8 or blocking treatment was 11.1±0.7%, in the presence of CXCL8 and the IgG control the percentage was 29.8±1.1%. When the cells were treated with anti-syndecan-3 at 4°C the percentage (compared to the isotype control) decreased significantly to 15.0±1.3% (p=<0.0001), with anti-syndecan-4 the percentage decreased but not significantly (25.4±2.2%). At 37°C the number of HBMECs that showed filopodia formation with no CXCL8 or blocking treatment was 4.6±0.3%; with the isotype control (in the presence of CXCL8) the percentage was 30.0±0.8%. There was a decrease in filopodia formation following treatment with both anti-syndecan-3 (8.9±0.7%; p=<0.0001) and anti-syndecan-4 (3.7±0.3%; p=<0.0001) when compared to the isotype control. In control ECs in the absence of CXCL8 cold exposure at 4°C increased filopodia formation compared to 37°C, although these values did not significantly differ, suggesting that physical stress such as cold temperatures may up-regulate filopodia abundance although the effect was less than that seen with chemokines.

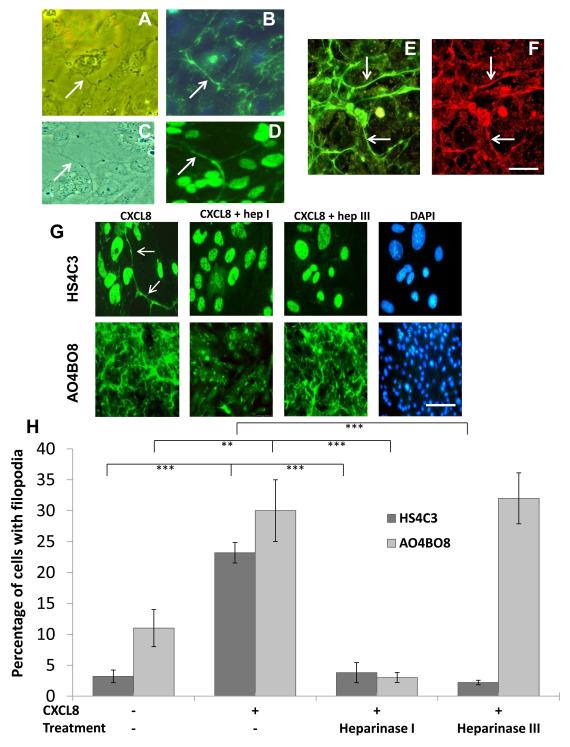

HS epitope expression

HBMECs were activated with CXCL8 as described above then labelled with antibodies AO4BO8 and HS4C3 specific for 2,6-O and 3-O sulphated epitopes of HS respectively (20,21), in order to determine whether HS with these sulphation patterns was expressed on filopodial protrusions seen in figure 1 and 2 by phase contrast imaging. Analysis of AO4BO8 immunofluorescence after treatment with CXCL8 revealed an abundance of 2,6-O-sulphated HS expression on filopodial protrusions that extended between cells and over the cell surface, appearing as a meshwork (figure 3A, B, E and G) (see Supplemental Material figure 1). The width of this meshwork was approximately 200-500nm. HS on the filopodial meshwork colocalised with CXCL8 (figure 3E and F). With antibody HS4C3, HS was also present on filopodial protrusions (figure 3C and D) which were often less extensive than with AO4BO8 and needed higher magnifications to image them (figure 3G left hand panels). There was no fluorescence when isotype control Ig or PBS was used instead of primary HS or CXCL8 antibodies.

Figure 3. Localisation of heparan sulphate 2,6-O and 3-O sulphated motifs on endothelial filopodia.

(A) CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs analysed by phase contrast showing a filopodial protrusion.

(B) same image as (A) using immunofluorescence with an antibody against the 2,6-O-sulphated heparan sulphate epitope (AO4BO8). Arrows show the localisation of heparan sulphate to the filopodium.

(C) CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs analysed by phase contrast showing a filopodial extension.

(D) same image as (B) using immunofluorescence with an antibody against the 3-O sulphated heparan sulphate epitope (HS4C3). Arrows show the localisation of heparan sulphate to the filopodium.

Double labelling using antibodies to heparan sulphate (E) and CXCL8 (F) showing colocalisation (arrows). Bar =5μm in (A-F).

(G) CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs pre-treated with and without heparinase I (10U/ml) and heparinase III (2U/ml) and analysed by immunofluorescence with antibodies against 3-O-sulphated epitopes (HS4C3) and 2,6-O sulphated epitopes (AO4BO8)(both green) with DAPI showing nuclear staining (blue). With HS4C3 antibody arrows show the filopodia. Bar = 5μm for HS4C3 and 20μm for AO4BO8.

(H) Analysis of immunofluorescence shown in (G) with the antibodies described, the percentage of cells with positive staining on the filopodia was quantified. Data show the means ± standard errors (SE) of the percentage of cells with filopodia in 10 fields of view (at ×200 magnification) from one experiment representative of two independent experiments. **p=<0.001 and ***p=<0.0001.

In order to verify that HS was present on the filopodial meshwork HBMECs were pre-treated with heparanase I and III to degrade this GAG (figure 3G) and the effects quantitated (figure 3H). An EC was scored positive when the HS-positive filopodia/meshwork was associated with it. Under normal conditions (no CXCL8 or enzymatic treatment) 10.8±2.8% of the ECs showed expression of AO4BO8 on these structures and 3.2±1.0% with expression of HS4C3 (figure 3H). When the cells were treated with 100ng/ml CXCL8 there was a significant increase in AO4BO8 expression (29.0±4.7%; p=<0.001) and HS4C3 expression (23.2±1.7%; p=<0.0001). When CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs were pre-treated with heparinase I, the percentage of cells expressing either 2,6-O-sulphated HS (2.6±0.8%; p=<0.0001) or 3-O-sulphated HS (3.8±1.6%; p=<0.0001) on the microstructures was significantly decreased. No difference on the expression of the AO4BO8 epitope (31.8±0.4%) was observed when the cells were pre-treated with heparinase III (figure 3G and H). However, there was a significant reduction in the proportion of cells with positive for the HS4C3 epitope (2.2±0.4%; p=<0.0001) following heparanase III treatment. With HS4C3 cell nuclei were also positive (figure 3D and G) in the presence or absence of CXCL8 and in the presence of heparanases; the significance of these results is as yet unknown.

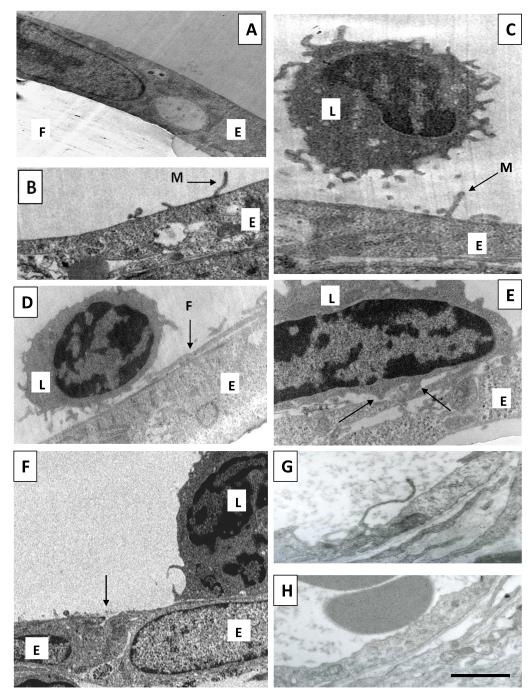

Leukocyte interaction with HBMEC microstructures and transendothelial migration

The effect of chemokine stimulation on ECs was analysed using transmission electron microscopy in order to examine filopodia/microvilli formation and their interaction with leukocytes. In these experiments HBMECs were grown to confluence on the filters of transwells and 100ng/ml CXCL8 was added to the lower well, adding the chemokine to the basal EC surface. When the ECs were unstimulated, the membranes were relatively smooth and featureless (figure 4A). When stimulated with CXCL8 for 30 minutes microvillous protrusions had formed that extended upwards from the apical cell surface (figure 4B and 4C). These measured approximately 200 nm in width and were up to 1μm in length. In addition, there were longer filopodia-like protrusions, measuring around 200-500nm in width. These extended laterally over the surface of the cell (figure 4D) and even over the adjacent cell, measuring microns in length (Supplemental Material figure 2). These filopodial and microvillous protrusions were associated with leukocytes (figure 4C and D). Quantitation of filopodial protrusions revealed that in the absence of CXCL8, 8±8% (mean ± SE) of cells (n=12) formed filopodial protrusions and this increased significantly to 50 ±14% (n=14 cells) in the presence of the chemokine (p=0.02). For the microvilli-like structures values were 15 ±10% (n=13 cells) without CXCL8 rising to 57 ±14% (n=14 cells) with the chemokine (p=0.02). Leukocytes also formed podosomes which were interacting with the endothelial layer (figure 4E).

Figure 4. Endothelial filopodial and microvillous protrusions and leukocyte interaction.

For A-F endothelial cells (HBMECs) were cultured on 3μm pore transwell filters and treated with 100ng/ml CXCL8 for 60 minutes in the basal compartment of transwells. Leukocytes were added to the apical compartment for the final 30 minutes before fixation and analysis using transmission electron microscopy.

(A) An unstimulated HBMEC monolayer (E) grown on a transwell filter (F).

(B) Microvillous protrusion (M) formed by the endothelial cell (E) in response to CXCL8 stimulation.

(C) A CXCL8-stimulated endothelial cell layer (E) with a leukocyte (L) in close proximity to endothelial microvilli (M).

(D) A leukocyte (L) interacting with a filopodial protrusion (F) of HBMECs (E) stimulated with CXCL8. This microstructure is extending laterally over the endothelial cell surface whereas in (B) and (C) microvilli extend more vertically.

(E) A leukocyte (L) interacting with CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs (E). Arrows indicate leukocyte podosomes.

(F) A CXCL8 treated layer of HBMECs (E) in the presence of leukocytes (L), there is an absence of large intercellular gaps between endothelial cells (arrow).

(G) Rabbit skin was injected with CXCL8 in vivo and after 30 minutes biopsies were taken and processed for electron microscopy. Note the presence of a protrusion similar to those seen in vitro (B-D). (H) is the same as (G) except that skin was vehicle-injected instead of CXCL8. Bar = 2μm in (A-H).

The integrity of the EC layer was examined since CXCL8 may have induced the formation of inter-endothelial gaps and leukocytes may have migrated through them. Transmission electron microscopy of the EC layer 15 and 30 minutes after the addition of CXCL8 did not reveal the formation of large inter-endothelial gaps or openings in the presence or absence of leukocytes (Figure 4F)(22). This suggests that CXCL8 did not cause EC disruption leading to impairment of the EC barrier in relation to leukocyte migration.

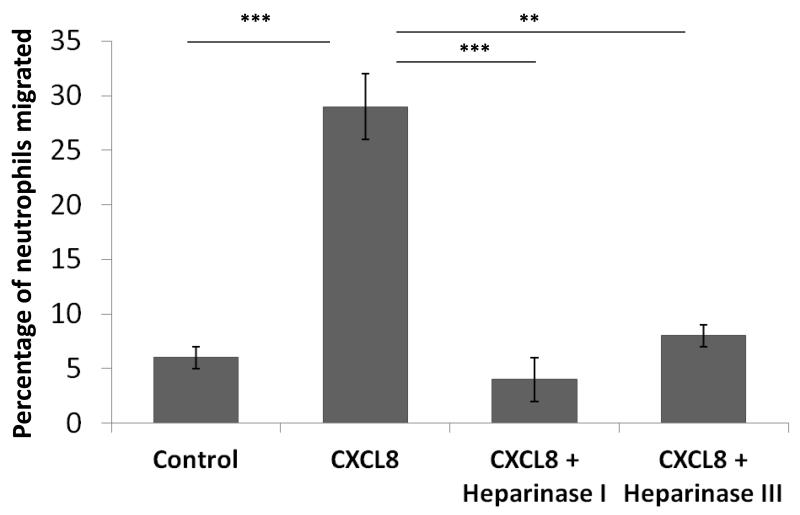

In the same experiments leukocyte transendothelial migration was examined. Under control conditions, in the absence of CXCL8 and minimal filopodia/microvilli formation, only 6% of neutrophils migrated (figure 5). With the addition of CXCL8 (100ng/ml for 30 minutes) and increase in filopodia/microvilli formation there was elevated neutrophil migration (5-fold, p=<0.0001). Since HS was shown to be present on filopodial structures (figure 3), the involvement of this GAG was examined. The percentage of neutrophils that migrated through the CXCL8-stimulated endothelial monolayer, after EC pre-treatment with heparinase I was significantly decreased (4.0±2.0%; p=<0.0001) and with heparinase III (8.0±1.2%; p=<0.001).

Figure 5. Neutrophil transendothelial migration.

In the same in vitro experiments as in Figure 4 endothelial cells (HBMECs) were cultured on 3μm pore transwell filters and treated with 100ng/ml CXCL8 for 60 minutes in the basal compartment of transwells. Leukocytes were added to the apical compartment for the final 30 minutes to allow for transendothelial migration. The percentage of neutrophils that migrated was determined by flow cytometry. HBMECs were also pre-treated with heparinase I (10U/ml) or heparinase III (2U/ml) prior to leukocyte migration. The percentage of neutrophils that migrated through an unstimulated endothelial monolayer (control), or a CXCL8-stimulated endothelial monolayer is shown. The graph indicates significant reductions when heparan sulphate was cleaved with heparinase I or III. The data represent percentage means ± SE (n=3 endothelial monolayers) and are representative of two individual experiments, ***p=<0.0001 and **p=<0.01 comparing treatments indicated.

Since a mixture of neutrophils and mononuclear cells were added in transendothelial migration assays, the migration of monocytes and lymphocytes across the ECs was also analysed. Gating on monocytes and lymphocytes it was found that there was insignificant migration in response to CXCL8 (100ng/ml for 30 minutes), amounting to <0.5% of these cells that migrated, whereas neutrophil migration amounted to ~30% (Figure 5).

Endothelial filopodia/microvilli formation in vivo

In order to examine if the microstructures described above in vitro also occur in vivo CXCL8 was injected into the skin of rabbits and biopsies taken at time points up to 4 hours and processed for transmission electron microscopy. Filopodial and microvillous protrusions occurred on the ECs of venules in the dermis from 30 minutes after injection, these were variable in length and were variously orientated, horizontally and more vertically (Figure 4G). They were not present in vehicle-injected sites and non injected skin (Figure 4H).

Effect of CXCL8 stimulation on differential endothelial protein expression

Since a functional role for CXCL8 had been determined in the formation of EC surface protrusions, the changes that were occurring within the cell after CXCL8 stimulation were examined by mass spectrometry.

iTRAQ analysis was performed on untreated HBMECs and those treated with 100ng/ml CXCL8 for 0.5, 6, and 16 hours. Comparing CXCL8 treated and untreated cells significant changes were seen in the levels of various proteins (p<0.05)(table 1A). These included cytoskeletal proteins: tropomyosin 1, which decreased with increasing time (iTRAQ ratio 0.81±0.10 at 0.5 hours, 0.79±0.12 at 6 hours and 0.63±0.14 at 16 hours); fascin, which decreased at 0.5 hours before returning back to the control level at 6 hours (0.88±0.09 at 0.5 hours, 0.99±0.05 at 6 hours and 1.00±0.16 at 16 hours); myotrophin that increased (1.50±0.17 at 0.5 hours, 1.05±0.20 at 6 hours and 1.18±0.09 at 16 hours); myosin isoform 2 that decreased over time (there was no standard deviation since there was only 1 peptide count; 0.86 at 0.5 hours, 0.65 at 6 and 16 hours); and myosin IE which decreased (0.74 at 0.5 hours, 0.82 at 6 hours and 0.76 at 16 hours). Extracellular matrix proteins changed including perlecan, which increased from 6 hours onwards (1.01±0.21 at 0.5 hours, 1.27±0.32 at 6 hours and 1.28±0.3 at 16 hours), type XVIII collagen (endostatin), which decreased at 0.5 and 6 hours before returning to the control level at 16 hours (0.75±0.11 at 0.5 hours, 0.54±0.38 at 6 hours and 0.97±0.23 at 16 hours), and type XII collagen which decreased (0.82±0.11 at 0.5 hours, 0.75±0.07 at 6 hours and 0.84±0.13 at 16 hours). Caveolin decreased initially then increased slightly with time (0.78 at 0.5 hours, 0.86 at 6 hours and 0.88 at 16 hours). Signalling proteins were altered such as Rab7, which increased compared to the control (1.13±0.05 at 0.5 hours, 1.08±0.12 at 6 hours and 1.15±0.27 at 16 hours), and Rac1, which also increased (1.58 at 0.5 hours, 1.64 at 6 hours and 1.53 at 16 hours).

Table 1. Differential endothelial protein expression following CXCL8 stimulation.

| A 5Most changed proteins | 0.5 hours | 6 hours | 16 hours | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Name | 1C.I (%) |

2Peptide count |

3Score | 4115/114 | 41167114 | 4117/114 |

| Tropomyosin-1 | 100 | 6 | 271 | 0.81±0.10 | 0.79±0.12 | 0.63±0.14 |

| Fascin | 100 | 7 | 521 | 0.88±0.09 | 0.99±0.05 | 1.00±0.16 |

| Myotrophin | 100 | 3 | 214 | 1.50±0.17 | 1.05±0.20 | 1.18±0.09 |

| Myosin isoform 2 | 94 | 1 | 36 | 0.86±0 | 0.65±0 | 0.65±0 |

| Myosin IE | 100 | 1 | 71 | 0.74±0 | 0.82±0 | 0.76±0 |

| Perlecan (HSPG2) | 100 | 12 | 644 | 1.01±0.21 | 1.27±0.32 | 1.28±0.30 |

| Type XVIII collagen (endostatin) | 100 | 3 | 171 | 0.75±0.11 | 0.54±0.38 | 0.97±0.23 |

| Type XII collagen | 100 | 7 | 514 | 0.82±0.11 | 0.75±0.07 | 0.84±0.13 |

| Caveolin | 99 | 1 | 43 | 0.78±0 | 0.86±0 | 0.88±0 |

| Rab7 | 100 | 3 | 96 | 1.13±0.05 | 1.08±0.12 | 1.15±0.27 |

| Rac1 | 99.92 | 1 | 50 | 1.58±0 | 1.64±0 | 1.53±0 |

| B 6Cytoskeletal and adhesion | 0.5 hours | 6 hours | 16 hours | |||

| Myosin 9 | 100 | 95 | 7635 | 0.88±0.2 | 0.92±0.24 | 0.94±0.23 |

| Cadherin-13 | 99.9 | 1 | 56 | 0.64±0 | 0.70±0 | 1.05±0 |

| Myosin VI | 100 | 5 | 297 | 0.88±0.22 | 0.97±0.33 | 1.1±0.14 |

| Tropomyosin-2 | 100 | 8 | 75 | 0.84±0.12 | 0.80±0.12 | 0.62±0.15 |

| C 7Signalling | 0.5 hours | 6 hours | 16 hours | |||

| Rab1 B | 100 | 2 | 130 | 0.98±0.03 | 0.97±0.1 | 0.96±0.04 |

| Rab2A | 97 | 3 | 35 | 0.90±0.57 | 1.00±0.5 | 0.97±0.5 |

| Rab4A | 100 | 2 | 84 | 1.01±0.01 | 1.10±0.02 | 1.13±0.14 |

| Rab4B | 100 | 2 | 110 | 0.96±0.04 | 0.96±0.12 | 1.03±0.02 |

| Rab11A | 100 | 2 | 83 | 1.10±0.09 | 1.02±0.02 | 1.03±0.001 |

| Rab35 | 100 | 2 | 84 | 0.92±0.08 | 0.95±0.12 | 0.95±0.05 |

| Rab37 | 100 | 2 | 90 | 0.89±0.01 | 1.04±0.03 | 0.97±0.03 |

| Rab33B | 100 | 1 | 77 | 1.01±0 | 1.08±0 | 1.01±0 |

| Rab6A | 100 | 1 | 77 | 1.01±0 | 1.08±0 | 1.01±0 |

| Rab6B | 100 | 2 | 79 | 0.99±0.01 | 0.97±0.10 | 0.98±0.02 |

| Rab39 | 100 | 2 | 77 | 1.00±0.004 | 1.00±0.05 | 1.02±0.004 |

The total ion score confidence interval (CI%) for the protein identification

the number of unique peptides with MS/MS ion scores used for identification

the total ion score

the average iTRAQ ratios of CXCL8 treated (115, 116 and 117) and untreated (114) HBMEC samples (± standard deviation from mean).

signficanlty changed proteins comparing CXCL8 treated and untreated HBMECs (p<0.05)(apart from where SD=0 with 1 peptide count)

cytoskeletal, adhesion and signalling proteins that changed but not significantly.

cytoskeletal, adhesion and signalling proteins that changed but not significantly.

Data are representative of 3 individual experiments.

There were other cytoskeletal and adhesion proteins of interest that showed changes compared to the control at various time points, although they were not significant (table 1B). These included myosin 9, cadherin-13, myosin VI and tropomyosin-2. In terms of signalling, numerous additional Rab GTPases showed changes after CXCL8 stimulation, although changes were not significant; these included Rab1B, Rab2A, Rab4A, Rab4B, Rab11A, Rab35, Rab37, Rab33B, Rab6A, Rab6B and Rab39.

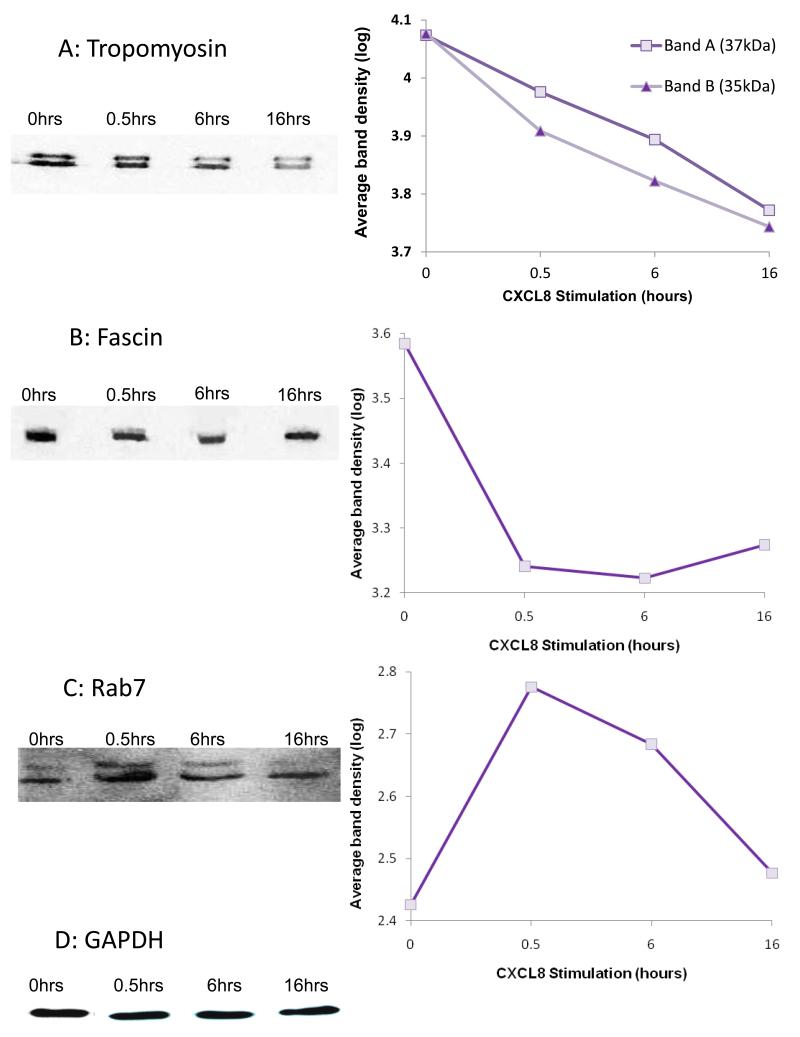

Western blot analysis, using the same cell digests, was performed using antibodies against tropomyosin, fascin and Rab7 to confirm the changes observed in the mass spectrometry; band densities at each time point were measured and the log data presented in graphical format (figure 6). The band densities for tropomyosin decreased with increasing time when compared to the no chemokine control (figure 6A); fascin decreased at 0.5-6 hours followed by a slight increase at 16 hours (figure 6B); the Rab7 showed an increase at 0.5 hours with a gradual decrease from 6-16 hours (figure 6C). These data are in general agreement with the iTRAQ ratios.

Figure 6. Western blot analysis of unstimulated and CXCL8-stimulated HBMECs.

Western blot analysis of HBMEC cell extracts in the absence or after addition of CXCL8 for the indicated time; total cell extracts were analysed using the indicated antibodies. Graphical data represent the log average band intensities from the western blots (Y-axis) for each of the time-points (X-axis) normalised for equal loading:

(A) Tropomyosin (band A 37kDa, band B 35kDa isoforms), representative blot of three individual experiments,

(B) Fascin, representative of two individual experiments,

(C) Rab7, the lower of the two bands was quantitated which corresponded to the expected molecular weight of the protein. Data are representative of two individual experiments.

(D) Representative blot probed for GAPDH which was used a loading control.

Discussion

There have been some reports on the formation of filopodial and microvillous processes by ECs under inflammatory conditions and in response to chemokine and chemoattractant (2-11). The present study extended these previous reports, examining formation of these structures in more detail, their composition, the receptors involved in their formation and intracellular changes. Chemokine-stimulated filopodia formation was not specific to CXCL8; the same effects were observed when the cells were incubated with CXCL10 and CCL5. However, the magnitude of response was different between the chemokines and cell types. The greatest response was for CXCL8 on HBMECs (13 fold increase) and the lowest was CCL5 on HMVECs (3 fold increase). In addition, chemokines stimulated filopodia formation by both microvascular (HBMEC and HMVEC) and macrovascular endothelial cells (HUVEC).

Several chemokine binding molecules were shown to be involved in the formation of endothelial filopodial protrusions following CXCL8 treatment. These were CXCR1 and CXCR2, DARC, HS and its proteoglycans syndecan-3 and syndecan-4. All the receptors and binding molecules caused a significant reduction in the percentage of cells that formed filopodia. The involvement of CXCR1 and CXCR2 suggests that signalling via these receptors is involved in creating these EC microstructures. DARC particularly played a role in their formation. Although high endothelial venule ECs from lymphoid tissue do not appear to express DARC in culture (23), HBMECs in the current study did express this receptor, indicating heterogeneity between ECs from different tissues. Interestingly DARC has been found to particularly localise to microvillous structures on MDCK cells where it colocalises with CCL2 (10). Since DARC is a silent chemokine receptor without a known signalling mechanism it may be involved in concentrating CXCL8 on filopodial protrusions possibly in conjunction with HS and syndecans.

The current study has shown that the effect of CXCL8 binding on filopodia formation through syndecan-3 is not dependent on internalisation as a reduction in the percentage of cells with these structures was seen at both 37°C and 4°C. The involvement of syndecan-3 in filopodia formation is in agreement with Berndt et al (24) who showed that syndecan-3 was required for the formation of long filopodia-like and microspike structures by Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Syndecan-3 has been found at high levels in the ECs of synovium in chronic arthritis (25). The finding that syndecan-3 is involved in filopodia formation suggests that this HSPG may be involved in the generation of EC protrusions seen in inflammatory disease (5).

An effect on filopodial protrusion formation through syndecan-4 may be dependent on internalisation since a significant reduction of cells with these structures was only seen at 37°C, at 4°C there was no effect. Zimmerman et al (26) showed syndecan-4 and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-FGF receptor (FGFR) internalisation and their colocalisation in recycling endosomes, their study provides evidence that syndecan-4 can internalise ligands and recycle them. Therefore in the present study, it is possible that syndecan-4 is internalising upon binding to CXCL8 and is recycling the chemokine via the endocytic pathway.

Using antibodies to specific HS epitopes, 2,6-O and 3-O-sulphated HS were found to be present on filopodial protrusions, occurring as a mesh-like structure. Confirmation of their expression was achieved with the use of heparanases; when the cells were incubated with heparanase I the expression of both HS epitopes on the meshwork was reduced to background. In contrast, heparansase III degraded the 3-O but not the 2,6-O epitope. Heparanase III cleaves 1-4 linkages between hexosamine and glucuronic acid, however it has weak activity with disaccharides containing iduronic acid and its action is blocked if iduronic acid is sulphated at C2 (IdoA-2SO3). Therefore since the 2,6-O HS epitope contains sulphated iduronate at C2 this may explain the lack action of heparanase III. Spillmann et al (27) reported that HS binding to CXCL8 correlates with the occurrence of 2,6-O-sulphated disaccharides and CXCL8 has been shown to bind to 6-O-sulphated glucosamine (28). Therefore the presence of 2,6-O-sulphated HS on the filopodial mesh may be involved in CXCL8 binding and sequestration and presentation of the chemokine to leukocytes. In this respect HS on ECs has been widely reported to bind, concentrate and present chemokines to leukocytes during extravasation (9,29-32). These chemokine binding sites on HS may be located on syndecan-3 and -4 since these are major HSPGs expressed on HBMECs in the present study. Such sites may be relevant in inflammatory diseases since in RA there is induction of a CXCL8 binding site on the HS chains of syndecan-3 by synovial ECs (25).

Transmission electron microscopy showed that leukocytes interacted with EC protrusions in transwell experiments, suggesting a role for them in leukocyte transmigration. Two types of structure were observed: microvillous protrusions that extended vertically and were short, and filopodial protrusions that were longer extending laterally over the cell surface, and leukocytes interacted with both types. Carman et al (13) showed that ECs formed ICAM-1 enriched microvilli-like projections that embraced leukocytes and extended up their sides to form cup-like structures. It is possible that the microvilli observed in the current study are similar to those described by Carman et al since the observed microvilli showed a positive expression of ICAM-1 (data not shown) however, it is currently unknown if this is the case since cup-like structures were not seen. Previous studies (12,33) suggest a role for podosomes in leukocyte extravasation. Podosomes have been shown to form on highly migratory cells and in leukocytes adhering to endothelium. The podosomes cause local displacement of cytoplasm, cytoskeleton and other organelles by forcing podo-prints into the surface of the EC. The work presented here showed that the leukocytes formed podosomes and they interacted with EC protrusions, possibly prior to leukocyte transendothelial migration through that area of the EC.

Heparanases were used to degrade HS and these reduced neutrophil transendothelial migration. This could have been due to the removal of HS from filopodia/microvilli and thus altered the ability of the ECs to bind and present CXCL8 to the neutrophils. This agrees with an earlier study (9) reporting that when CXCL8 was injected in the skin it localised to EC microvillous processes and longer projections, however a modified version of CXCL8 with impaired binding to HS showed reduced localisation to these structures and reduced neutrophil recruitment. In addition, heparanase reduces the formation of filopodial protrusions (figure 2A) therefore the inhibited neutrophil migration may have also been due to this factor. Therefore the heparanase effect may have been due to a combination of reduced chemokine presentation and filopodia formation.

In transwell experiments it is conceivable that CXCL8 may have induced the formation of large gaps or openings in the EC layer creating a chemotactic gradient without an EC barrier, thereby allowing neutrophils to migrate through them. However, electron microscopy did not reveal the existence of such gaps which have been seen by this technique in the presence of mediators such as histamine (22). In the present study CXCL8 was added to the basal EC surfaces in transwell chemotaxis experiments in Figures 4 and 5 and to the apical surfaces in Figures 1-3 and Table 1. Both approaches involved an identical time point (30 minutes) and chemokine concentration (100ng/ml) to generate filopodial protrusions. These microstructures were generated whether the chemokine was applied apically or basally, although it is as yet unknown whether the mechanism of their formation is identical depending on where the EC encounters the chemokine first.

ITRAQ mass spectrometry showed that upon CXCL8 binding to ECs there were changes in cytoskeletal, extracellular matrix and signalling proteins at all the time points examined. The changes in the cytoskeletal proteins, such as tropomyosin, suggest a reorganisation of the EC cytoskeleton upon CXCL8 binding; no changes were detected in the levels of actin. Tropomyosin provides structural stability and modulates actin filament function (34), therefore this protein may be associated with changes in the stability of the cytoskeleton that may occur during chemokine-stimulated filopodia/microvilli formation. Fascins are actin-binding proteins that cross-link filamentous actin (35), they have been shown to be involved in filopodial protrusion formation in several cell types. Alteration in the levels of myosin was apparent and this molecule is also known to interact with actin filaments (36). Therefore fascin and myosin may both be involved in EC microstructure formation seen in the current study through their cytoskeletal roles. Changes in extracellular matrix proteins, such as perlecan and endostatin (type XVIII collagen) which are associated with the basement membrane, suggest that the CXCL8-stimulated formation of filopodia/microvilli may be associated with changes in basement membrane-EC interactions. There were differences between the basement membrane proteins, perlecan expression increased after 6 hours, whereas endostatin decreased at 0.5 and 6 hours before increasing again after 16 hours. Changes in signalling molecules such as the small GTPases Rab7 and Rac1 are associated with chemokine-stimulated filopodia formation. In this connection chemokine receptors are associated with Rab and Rac signalling leading to changes in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and intracellular vesicular trafficking (37,38). Since CXCR1 and CXCR2 were found to be involved in filopodia formation in response to CXCL8 it is possible that these receptors may be acting via Rab and Rac leading to changes to the cytoskeleton and intracellular trafficking. Indeed both CXCR1 and CXCR2 have been shown to be involved in the reorganisation of the cytoskeleton when microvascular ECs are stimulated with CXCL8 (39) and enhanced vesicle formation occurs in ECs when stimulated with this chemokine (8). Concerning the formation of the filopodial and microvillous structures in response to chemokines, these happened rapidly, being already formed at 30 minutes. Therefore their formation is unlikely to be protein synthesis-dependent but reflects rapid changes in the levels of cytoskeletal, signaling and extracellular matrix proteins. However, at later time poins of 6 and 16 hours altered protein synthesis is more likely to occur.

The present study used an in vitro assay of endothelial protrusion formation using phase contrast microscopy to determine dose responses of endothelial cell types to different chemokines. The assay detected filopodia-like structures extending horizontally from the periphery of cells grown on plastic. These structures were also positive for HS by immunofluoresence microscopy which showed a filopodial meshwork that bound CXCL8. Similar long filopodial structures that extended horizontally were also visible on the endothelial surface using electron microscopy which probably represents the meshwork in thin section. The size of the filopodial structures were in general agreement considering the various experimental approaches and processing methods. By electron microscopy they measured around 200-500 nm in width. The meshwork by immunofluorescence also measured around 200-500 nm in width. These were within the range of filopodial protrusions seen by phase contrast, being 200-1000 nm in width. The formation of these filopodial structures seen by all three techniques was stimulated by chemokines. In addition, vertically extending microvilli-like structures were apparent on the apical EC surface using electron microscopy and were less obvious using the other imaging techniques. Furthermore endothelial filopodial/microvilli-like structures were observed on ECs in vivo, following CXCL8 injection into rabbit skin. These structures extended laterally as well as more vertically and measured up to microns in length at the luminal endothelial surface. These have also been seen in earlier studies in human and rabbit skin (8,9). Therefore our in vitro assay appears to reflect similar structures formed in vivo. In the present study we have used the terms filopodia and microvilli to describe various endothelial structures observed by different techniques. These have also been described in the literature and similar structures have also been termed membrane wrinkles, projections or simply protrusions.

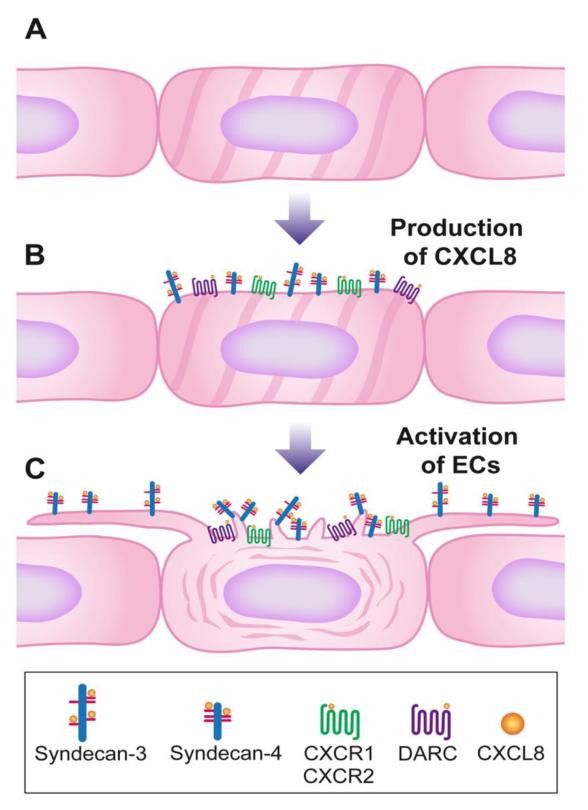

The findings of this study led to the development of a model of EC filopodial and microvillous protrusion formation by CXCL8 (figure 7). When ECs encounter CXCL8 generated under inflammatory conditions, the chemokine binds to the CXCR1/2 receptors and to the chemokine binding molecules HS, syndecan-3, syndecan-4, and DARC, each of which may be involved in the formation of filopodia. Upon CXCL8 binding (figure 7B) there is an alteration in signalling pathways involving small GTPases. The actin filaments of the cytoskeleton begin to reorganise, via changes in molecules such as tropomyosin and fascin which reduce in levels, and this leads to one of two possible events, either the actin filaments begin to move outwards causing the filopodia to form, or the action of the filopodia forming pulls the actin filaments towards them. Similarly changes in the cytoskeleton are associated with microvillous protrusion formation. In addition, a disruption of the basement membrane allows the cells to adapt to their surroundings via changes in endostatin and perlecan. On the filopodia and microvilli (9), CXCL8 binds to HS motifs, which may be located on syndecan-3/4 proteoglycans, and is presented to blood leukocytes (figure 7C). Sequestration and clustering of the chemokine on the HSPGs located on the EC microstructures increases the surface concentration of chemokine to activate blood leukocytes leading to firm adhesion, crawling and leukocyte transendothelial migration. This study provides evidence for a novel mechanism by which chemokines may stimulate their own presentation at sites of inflammation by creating EC filopodial and microvillous protrusions.

Figure 7. Schematic model of chemokine-stimulated endothelial filopodial and microvillous protrusion formation.

(A) Smooth endothelium in non-inflamed tissue.

(B) In inflammation CXCL8 production leads to binding of the chemokine to heparan sulphate chains on syndecan-3/syndecan-4, CXCR1, CXCR2 and DARC.

(C) Upon CXCL8 binding to the receptors, there are changes in signalling pathways, reorganisation of the cytoskeleton and the formation of filopodial and microvillous protrusions. Filopodial protrusions are long laterally extending structures that can mere to form a mesh. On these structures the chemokine is presented to leukocytes in the blood by heparan sulphate on syndecan-3 and -4. Microvillous protrusions are shorter and more vertically orientated. They also present chemokines probably in association with heparan sulphate (9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks goes to Dr Ian Holt for his assistance with the confocal microscopy; Dr Heidi Fuller and Dr Emma Wilson, CIND, for the mass-spectrometry work; Professor Guido David (University of Nantes) and Professor Toin Van Kuppevelt (University of Leuven) for donating the syndecan and HS phage display antibodies, including helpful discussions; and Karen Walker from the transmission electron microscopy unit at Keele University.

Footnotes

This research was funded by Keele University, UK, the Medical Research Council, UK and the Institute of Orthopaedics, RJAH Orthopaedic Hospital, Oswestry, UK.

References

- 1.Middleton J, Americh L, Gayon R, Julien D, Aguilar L, Amalric F, Girard JP. Endothelial cell phenotypes in the rheumatoid synovium: activated, angiogenic, apoptotic and leaky. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:60–72. doi: 10.1186/ar1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Smet F, Segura I, De Bock K, Hohensinner PJ, Carmeliet P, P Mechanisms of vessel branching: filopodia on endothelial tip cells lead the way. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:639–649. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrovic N, Schacke W, Gahagan JR, O’Conor CA, Winnicka B, Conway RE, Mina-Osorio P, Shapiro LH. CD13/APN regulates endothelial invasion and filopodia formation. Blood. 2007;110:142–150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sainson RC, Johnston DA, Chu HC, Holderfield MT, Nakatsu MN, Crampton SP, Davis J, Conn E, Hughes CC. TNF primes endothelial cells for angiogenic sprouting by inducing a tip cell phenotype. Blood. 2008;111:4997–5007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sattar A, umar KP, Kumar S. Rheumatoid- and osteo-arthritis: quantitation of ultrastructural features of capillary endothelial cells. J. Pathol. 1986;148:45–53. doi: 10.1002/path.1711480108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walski M, Chlopicki S, Celary-Walska R, Frontczak-Baniewicz M. Ultrastructural alterations of endothelium covering advanced atherosclerotic plaque in human carotid artery visualised by scanning electron microscope. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;53:713–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lossinsky AS, Pluta R, Song MJ, Badmajew V, Moretz RC, Wisniewski HM. Mechanisms of inflammatory cell attachment in chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: a scanning and high-voltage electron microscopic study of the injured mouse blood-brain barrier. Microvasc Res. 1991;41:299–310. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(91)90030-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swensson O, Schubert C, Christophers E, Schroder JM. Inflammatory properties of neutrophil-activating protein-1/interleukin 8 (NAP-1/IL-8) in human skin: a light- and electronmicroscopic study. J. Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:682–689. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middleton J, Neil S, Wintle J, Clark-Lewis I, Moore H, Lam C, Auer M, Hub E, Rot A. Transcytosis and surface presentation of IL-8 by venular endothelial cells. Cell. 1997;91:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pruenster M, Mudde L, Bombosi P, Dimitrova S, Zsak M, Middleton J, Richmond A, Graham GJ, Segerer S, Nibbs RJ, Rot A. The Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines transports chemokines and supports their promigratory activity. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ni.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng D, Nagy JA, Pyne K, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM. Neutrophils emigrate from venules by a transendothelial cell pathway in response to FMLP. J Exp Med. 1998;187:903–915. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carman CV, Sage PT, Sciuto TE, de la Fuente MA, Geha RS, Ochs HD, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM, Springe TA. Transcellular diapedesis is initiated by invasive podosomes. Immunity. 2007;26:784–797. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carman CV, Jun CD, Salas A, Springer TA. Endothelial cells proactively form microvilli-like membrane projections upon intercellular adhesion molecule 1 engagement of leukocyte LFA-1. J. Immunol. 2003;171:6135–6144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carman CV, Springer TA. A transmigratory cup in leukocyte diapedesis both through individual vascular endothelial cells and between them. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:377–388. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schweitzer KM, Vicart P, Delouis C, Paulin D, Drager AM, Langenhuijsen MM, Weksler BB. Characterization of a newly established human bone marrow endothelial cell line: distinct adhesive properties for hematopoietic progenitors compared with human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 1997;76:25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dennissen MA, Jenniskens GJ, Pieffers M, Versteeg EM, Petitou M, Veerkamp JH, van Kuppevelt TH. Large, tissue-regulated domain diversity of heparan sulfates demonstrated by phage display antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:10982–10986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Kuppevelt TH, Dennissen MA, van Venrooij WJ, Hoet RM, Veerkamp JH. Generation and application of type-specific anti-heparan sulfate antibodies using phage display technology. Further evidence for heparan sulfate heterogeneity in the kidney. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12960–12966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith WB, Gamble JR, Clark-Lewis I, Vadas MA. Interleukin-8 induces neutrophil transendothelial migration. Immunology. 1991;72:65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller HR, Man NT, le Lam T, Shamanin VA, Androphy EJ, Morris GE. Valproate and Bone Loss: iTRAQ proteomics show that valproate reduces collagens and osteonectin in SMA cells. J. Proteome Res. 2010;9:4228–4233. doi: 10.1021/pr1005263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurup S, Wijnhoven TJ, Jenniskens GJ, Kimata K, Habuchi H, Li JP, Lindahl U, van Kuppevelt TH, Spillmann D. Characterization of anti-heparan sulfate phage display antibodies AO4B08 and HS4E4. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21032–21042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ten Dam GB, Kurup S, van de Westerlo EM, Versteeg EM, Lindahl U, Spillmann D, van Kuppevelt TH. 3-O-sulfated oligosaccharide structures are recognized by anti-heparan sulfate antibody HS4C3. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4654–4662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu NZ, Baldwin AL. Transient venular permeability increase and endothelial gap formation induced by histamine. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1238–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.4.H1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacorre DA, Baekkevold ES, Garrido I, Brandtzaeg P, Haraldsen G, Amalric F, Girard JP. Plasticity of endothelial cells: rapid dedifferentiation of freshly isolated high endothelial venule endothelial cells outside the lymphoid tissue microenvironment. Blood. 2004;103:4164–4172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berndt C, Casaroli-Marano RP, Vilaro S, Reina M. Cloning and characterization of human syndecan-3. J Cell Biochem. 2001;82:246–259. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson AM, Gardner L, Shaw J, David G, Loreau E, Aguilar L, Ashton BA, Middleton J. Induction of a CXCL8 binding site on endothelial syndecan-3 in rheumatoid synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2331–2342. doi: 10.1002/art.21222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann P, Zhang Z, Degeest G, Mortier E, Leenaerts I, Coomans C, Schulz J, N’Kuli F, Courtoy PJ, David G. Syndecan recycling [corrected] is controlled by syntenin-PIP2 interaction and Arf6. Dev. Cell. 2005;2005:9–377. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spillmann D, Witt D, Lindahl U. Defining the interleukin-8-binding domain of heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15487–15493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchimura K, Morimoto-Tomita M, Bistrup A, Li J, Lyon M, Gallagher J, Werb Z, Rosen SD. HSulf-2, an extracellular endoglucosamine-6-sulfatase, selectively mobilizes heparin-bound growth factors and chemokines: effects on VEGF, FGF-1, and SDF-1 BMC. Biochem. 2006;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proudfoot AE, Handel TM, Johnson Z, Lau EK, LiWang P, Clark-Lewis I, Borlat F, Wells TN, Kosco-Vilbois MH. Glycosaminoglycan binding and oligomerization are essential for the in vivo activity of certain chemokines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:1885–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334864100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoogewerf AJ, Kuschert GS, Proudfoot AE, Borlat F, Clark-Lewis I, Power CA, Wells TN. Glycosaminoglycans mediate cell surface oligomerization of chemokines. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13570–13578. doi: 10.1021/bi971125s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali S, Robertson H, Wain JH, Isaacs JD, Malik G, Kirby JA. A non-glycosaminoglycan-binding variant of CC chemokine ligand 7 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-3) antagonizes chemokine-mediated inflammation. J. Immunol. 2005;175:1257–1266. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salanga CL, Handel TM. Chemokine oligomerization and interactions with receptors and glycosaminoglycans: the role of structural dynamics in function. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carman CV. Mechanisms for transcellular diapedesis: probing and pathfinding by invadosome-like protrusions. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3025–3035. doi: 10.1242/jcs.047522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang CL, Coluccio LM. New insights into the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton by tropomyosin. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2010;281:91–128. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)81003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hashimoto Y, Kim DJ, Adams JC. The roles of fascins in health and disease. J Pathol. 2011;224:289–300. doi: 10.1002/path.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coluucio LM. Myosins: a superfamiliy of molecular motors. Springer; Dorrecht, The Netherlands: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan GH, Lapierre LA, Goldenring JR, Richmond A. Differential regulation of CXCR2 trafficking by Rab GTPases. Blood. 2003;101:2115–2124. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cancelas JA, Jansen M, Williams DA. The role of chemokine activation of Rac GTPases in hematopoietic stem cell marrow homing, retention, and peripheral mobilization. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:976–985. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schraufstatter IU, Chung J, Burger M. IL-8 activates endothelial cell CXCR1 and CXCR2 through Rho and Rac signaling pathways. Am. J. Physiol Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2001;280:L1094–L1103. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.