Abstract

Indonesian family systems do not conform to the prevailing image of Asian families, the predominant arrangements being nuclear and bilateral, with an important matrilineal minority. This paper considers the strength of family ties in two communities, focussing particularly on inter-generational flows of support to and from older members. Data are drawn from a longitudinal anthropological demography that combines ethnographic and panel survey methods. Several sources of variation in family ties are detailed, particularly the heterogeneity of support flows – balanced, upward, and downward – that co-exist in both communities. Different norms in each locale give sharply contrasting valuations of these flows. The ability of families to observe norms is influenced by the effectiveness of networks and by socio-economic status.

1. Introduction

The images evoked by the phrase ‘strong family ties’ are various, and will be treated in this paper as an open question needing more, and more nuanced, empirical study. As a starting point, we can take the seemingly unexceptionable proposition that the ‘strength’ of ties is defined by prevailing social norms: strong ties exist in societies in which positive intra-family relations are highly valued. What is this likely to entail? Most people will affirm as strong family values those that stress affective and moral bonds, flows of material support, proximity (which may or may not entail co-residence) and regularity of contact across the life course. The strength of ties, in other words, has a number of dimensions, both moral and behavioural. Some or all of these factors may be relevant in a given case. There are also structural sources of variation inhering in different family systems. Not only the changing demographics of birth, death, marriage and migration, but customary arrangements of joint, stem, nuclear and other family organisations, will mean that more or less extensive sets of kin are available to become potential loci of strong ties. Within these different systems, some kin roles are a greater locus of expectation and bonding than others.

Strong ties to some members may rest on mutual dependence. In other cases, ‘strength’ is one-sided – an asymmetry in the age, ability and wealth of family members willing to give support. Asymmetries often change during the life course, reflecting unavoidable physical dependence at the youngest and oldest ages, health or economic crises, or the impact of factors like migration. Reciprocity between generations is likely to be at best approximate, not only because kinds of support given and received are not strictly commensurable, but because they are distributed over differing intervals in a given elder’s life course in which economic and social conditions vary. Those in younger generations who are in receipt of the most support from their elders are not necessarily the ones who in due course return the favour. The sentiment of strong ties between generations need not be influenced by this. Or, younger family and kin may feel obliged to help errant elders who have in the past done little for them. The shared resentment and guilt that not uncommonly arise in such circumstances may tie people together powerfully, but can such arrangements be included in the ideal that strength of ties is a positive norm?

In sum, at least six sources of variation appear to shape the strength of ties: 1. the normative form and composition of families; 2. expectations attached to particular gender and family roles; 3. demographics (which limit or expand the family size); 4. time, or the relative life course position of available members; 5. different types and levels of support; and 6. the directionality of support flows between generations. Reality thus moves inexorably away from the cosy world of idealised family bonds to the variability and uncertainty of ties in practice. Family members’ capacities vary, and competing values beckon. The contributions of individual family members and the solidarity of whole families will also be shaped by occupational and status structures, customary property transmission and involvement in state and community institutions. Strong ties usually build up only in some sub-set of family networks and may depend on these wider circumstances more than on affect or ideals. As we shall see, differences in socio-economic strata and in effective network organisation are crucial to understanding why a range of less preferred practices co-exist with family ideals.

This paper begins by outlining several main features of contemporary Indonesian family networks that run counter to familiar Western stereotypes about family norms in Asia. We then turn to one aspect of these networks – flows of support to and from older members in their later lives – in order to examine the variability of ties and to ask whether current trends mark a change in patterns of family relationships. The diversity of inter-generational support flows over time, both within and between communities, suggests that family systems have much greater flexibility and adaptive capacity than is revealed in conventional approaches that tend to focus on aggregate net outcomes, i.e. whether the majority of support flows ‘up’ (i.e. from younger to older generations) or ‘down’ (older to younger) in a community or survey population taken as a whole. The data are drawn from Ageing in Indonesia, a longitudinal anthropological demography of communities in East and West Java, and West Sumatra.

2. Indonesia against the trend?

Indonesia is counterfactual to Western perceptions of Asian family systems in several important respects. First, the dominant tradition in Asian family and kinship systems is widely assumed to be joint/extended, in contrast to the prevalence of nuclear/bilateral systems in much of Europe (e.g. Hajnal 1982). This stereotype doubtless reflects the sheer demographic weight of China and South Asia, where patrilineal joint families are the historical norm. Yet there is another demographic heavyweight in Asia, the world’s fourth most populous state, Indonesia. In Java, more than 120 million Indonesians follow the nuclear/bilateral pattern, a larger population than live in any European country. There are other important surprises: Indonesia is home to some 4.8 million Minangkabau, the second largest matrilineal population in the world. Even where the joint/extended pattern prevails, therefore, we should not be too hasty in assuming uniformity of type. Second, changing marriage patterns also run counter to Western expectation. Divorce was not primarily a male prerogative, nor did it increase as Indonesia engaged more fully with Western economy and culture. To the contrary, recent trends show marked declines in divorce (Jones 1997). Women have traditionally had more autonomy in this predominantly Muslim society than conventional images of Asia and Islam allow (Hull and Hull 1987; Malhotra 1991; Wolf 1992).

A third and related point is that Indonesian family systems do not rely on a ‘rationality of high fertility’. Levels of total fertility leading up to demographic transition were not high by European standards. Javanese fertility, estimated at 5.2 (McNicoll and Singarimbun 1983: 44) and 4.27 (for Java and Bali, Hirschman and Guest 1990: 142-3), was comparable to modest levels experienced in parts of 18th century Europe, such as Sweden (4.21) or in pre-transitional England and Wales (5.28) (Livi-Bacci 1992). Even so, fertility above four children per woman might be taken to imply that shortages of children were not an issue. Yet in East Java, nearly one in five ever-married women over the age of 30 in 1971 experienced childlessness (Hull and Tukiran 1976). This figure is comparable to historical levels in early modern Europe (Kreager 2004), and is confirmed in more recent Indonesian research (Schröder-Butterfill and Kreager 2005).

Fourth, Indonesia fails to follow the stereotype of a rural Asian economy in which joint families rely on a pool of local children and grandchildren to meet labour needs. Historical accounts reveal major trade and migration flows before the colonial era, and census data collected by the Dutch in 1930 showed over half a million Indonesians moving within and between the main islands (Cribb 2000). Studies in the post-war era emphasize that widespread temporary migration is largely missing from census and other standard sources; net remittances from non-permanent migrants were of greater importance to villagers than those from the relatively smaller number of villagers who moved away permanently (Hugo 1983). The tremendous mobility of current younger populations is thus not something new, but a continuation and redevelopment of labour patterns involving demands for seasonal, circular, and periodic migration. The possible migration of family members of course carries important implications for fertility and inter-generational attitudes. On one hand, if children are prone to leave, then couples are unlikely to embark on childbearing with the idea that family size is decided simply by their fertility or that children can be counted on as an enduring source of labour and support. On the other, as the Indonesian case shows (Kreager 2006), children often continue to be valued in the family network irrespective of the fact that their material contributions to parents are small. The annual home visit of distant adult children who contribute minimally to material family exchanges is an important expression of family solidarity.

Finally, and in consequence of all of the above, the preferred living arrangement of most older Indonesians is not co-residence with children. In contrast to India and China, or to stem family traditions in Thailand or Japan, the nuclear/bilateral family systems as found in Indonesia entail no normative strategy of heirship that publicly designates a single child as responsible for parents’ property and maintenance in old age. Older and younger couples readily state their preference for independence. Recourse to co-residence, in contrast, is often seen as a regrettable necessity due to economic hardship, marital breakdown, or health difficulties (Schröder-Butterfill 2004b).3 Elders’ preference is to have a reliable child close by, together with positive relations with all children wherever they may be. Ageing in Indonesia data show upwards of 45 per cent of adult children away from their parental community at a given point in time (Kreager 2006). Most return on a regular basis, usually for brief visits, and some may return for extended periods. Household compositions and family roles consequently adjust as different members respond to each other in the context of changing labour demand, divorce, education and health issues. The prevalence of nuclear/bilateral family patterns encompasses a diversity of household compositions. Migration and competing demands on younger generations require fluid support arrangements for old and young alike, a shifting and sometimes fragile division of family labour in which support flows back and forth between family groups according to the varying presence, capacities and needs of children and parents (Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill 2007). Comparison to European patterns may, once again, prove suggestive, as recent surveys indicate that older people are dependent on family support coming from outside their own households (Grundy et al. 1999).

In sum, in Indonesia, as in Europe, the strength of ties that bind elders and adult children is often a matter of considerable uncertainty, notably where competing demands can take one generation away at the very moment that other generations are in need of them. If residence and fertility levels are inconstant guides to family dynamics, we cannot look to simple measures of them (e.g. dependency ratios, household sizes, percentages of co-residence) to provide reliable proxies for strong family ties. No one residence or fertility pattern coincides with relations of mutuality amongst independent households, nor with heavy dependence of some households, or certain members of them, on others. A much closer look at the structure and content of flows of support over time is needed, and the patterns of actual support require comparing to stated norms.

3. Wealth flows

Demographic research on wealth flows has been an object of contention for three decades. As noted earlier, Indonesia is one place where the hypothesized ‘rationality of high fertility’ is likely to have little applicability. Fortunately, a number of recent reviews (Caldwell 2005; Kaplan and Bock 2001; Lee 2000) help to sift the knowledge gained in this sub-field from the recurring arguments. Caldwell’s (1976) original and seminal article brought about a major shift in thinking about the fertility transition by providing an alternative to the untenable assumption, more or less explicit in mainstream post-war demography, that high fertility in the developing world is irrational. He sought to replace this approach with a logic that showed why high fertility often makes sense in rural societies, reasoning that because the net flow of family wealth passes “upwards” from children to parents over their life course, it is in fact rational to have many offspring. He imagined “a great divide” in demographic history: as the spread of Western family, educational and material values gradually makes children more expensive to maintain and less available in childhood as labour resources, the net flow of wealth reverses. The shift to “downward” wealth flows thence becomes a central mechanism pushing reproductive levels down.

An immediate consequence of Caldwell’s intervention was the growth of empirical studies addressed to what children contribute to the family, especially tasks that enhance the domestic economy either directly or by providing time and opportunities for other members. Children’s contributions, however, are of diverse kinds, and rarely part of the monetised economy. The several dimensions of family support noted earlier, and the fact that ties change across the life course, are a reminder of how difficult comprehensive measurement of child inputs is likely to be. Detailed and sustained observation is clearly required to define and monitor child contributions, and to help decide appropriate criteria of measurement, where possible. This has, in turn, encouraged some researchers to try to achieve a greater balance between qualitative and quantitative evidence than is usual in demography. As the three recent reviews indicate, however, research following on Caldwell’s pioneering African work failed to establish his notion of “reversal” as a central mechanism of fertility transition. Although Caldwell (2005) has reiterated his dissent on the matter, much of the research indicates that net flows of wealth have traditionally been downward, i.e. from parents to children, in a wide range of pre-transitional and transitional societies (Kaplan and Bock 2001; Lee and Kramer 2002).

The gain from this field of study remains, nonetheless, incontestable. We know a great deal more about the nature of ties between family members and what shapes them. Support flows, whether upward or downward, are part of complex patterns in which different forms of wealth or support proceed in both directions, as well as to siblings; reversals of flows may occur not once, but at different points in a family’s or individual’s life course, subject to relative poverty, changing health, and economic circumstances (Collard 2000; Kabeer 2000; Schröder-Butterfill 2006; Vera-Sanso 2004). While differences of opinion continue to surround strategies of measurement,4 there is little disagreement on one aspect: children are commonly viewed as important potential sources of social insurance in old age in most of Asia, Africa and Latin America. Of course, elderly informants’ accounts of their situation require careful interpretation; they may be less a reflection of actual material transfers than normative statements designed to secure family and individual reputation. The vulnerability of certain sub-groups – notably widows – is often known to everyone in a community, and has become an established theme in the literature, from Cain’s (1981; 1986) early study to more recent work (Marianti 2004). Other important variants that spread family costs across the generations, as Caldwell repeatedly remarked, include the support that older children give to siblings via provision of care in early years or financial support later on for education (Lee and Kramer 2002; Nag et al. 1978). The labour contributions of senior family members are another major part of this calculus, which commonly continue over nearly the whole life course (Dharmalingam 1994; Li 1989; Schröder-Butterfill 2004b). In short, contributions normally come from changing sets of members and are not distributed uniformly over time. Evidence of the diversity of inputs into the family economy, of different members’ changing capacity to provide support and of multiple flows involving different sets of family members thus suggest that the emphasis on net flows tends to oversimplify our picture of old age support. In addition, the tendency to focus on single villages taken as homogeneous communities, or to derive estimates from national household surveys that rely on reports of a single family member, inevitably disguises heterogeneity. Because Caldwell raised the question of wealth flows initially in an attempt to explain fertility transition, research has often been more occupied with whether a potentially deterministic relation can be established between upward flows and family size than with the structure of flows as a fundamental question of network demography. The reviews given by Lee (2000) and by Kaplan and Bock (2001) consider the results of the former approach unsuccessful. The general sociological and demographic interest of the latter surely deserves further exploration. As it seems likely that there are in fact multiple patterns of support involving older people, we need to ask how flows can be differentiated, and what this tells us about the differential strength of family ties.

These questions require a comparative approach and lead very quickly to further topics of interest. Are there significant differences in the pattern of support flows from community to community in a given country or society? Are there recurring differences characteristic of socio-economic strata, ethnicities or other distinctive sub-populations, and do they help to explain community differences? Given the importance of migration as a structural feature of many family networks, how can its influence on support flows be integrated into analysis? How do different patterns in support flows vary over time? These are questions that all need to be resolved before we can say what it means to maintain strong family ties in a given society.

4. The research setting

Since April 1999, three communities located in East Java, West Java and West Sumatra have been the subject of longitudinal ethnographic and demographic field study.5 Limitations of space restrict comparison here to only two of the sites, Kidul in East Java and Koto Kayo in West Sumatra. The former is characterised by the nuclear/bilateral family pattern, whilst the Minangkabau population of Koto Kayo is matrilineal. Proportions of adult children reported in 2000 as no longer resident in the community (46 and 75 per cent, respectively) give some idea of the active engagement of family networks in regional, national and international economies. Since most migrants are of younger ages, this level of migration tends to increase the proportion of the population aged 60 and over: nearly 11 and 18 per cent of the respective communities are over age 60, noticeably higher than the 7 per cent normal at provincial levels (Ananta et al. 1997). Both communities are characterised by a mixed family economy, drawing on employment in local government, services and small-scale manufacturing, whilst also retaining the traditional economic base in agriculture and local markets. Both are predominantly Muslim. Languages spoken in the home are Javanese and Minangkabau, with most speakers at least competent in the national language, Bahasa Indonesia. Interviewing thus needed to remain sensitive to differences of expression in more than one language in each site.

In order to capture the effects of disparate patterns of support involving older people, we combined data on flows within and between households that shared in a common intergenerational family network. For the purpose of this analysis, the primary focus will be on material (money, food, medication) and practical (physical care, childcare, domestic work) support flowing between older parents, their children, grandchildren and, where significant, nephews and nieces. We analysed household survey data on work, income and ownership of productive assets; older people’s health status; the division of labour and distribution of income in households; and the exchanges between network members of routine material and practical support, and less frequent recent occurrences of substantial assistance (e.g. payment of a hospital bill or major life-cycle ritual, providing business capital). For many elderly respondents we additionally have data from semi-structured and in-depth interviews with elders and their family members which give rise to a rich corpus of case study material, drawn on selectively below.

On the basis of these data, older people were ascribed to one of four net intergenerational support flow categories. Elders in downward flow arrangements were providing more support to children or grandchildren than they were receiving; those in upward flow arrangements were dependent on support from the younger generations; those in balanced arrangements were either engaged in even exchanges between the generations or in situations of widespread independence of the generations; finally, a small minority were neither receiving nor providing any intergenerational support.

5. The structure of intergenerational support in 2000

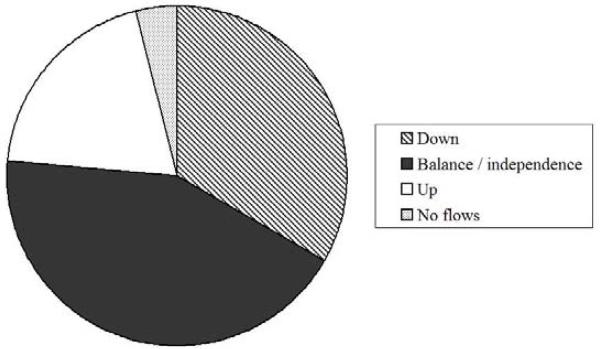

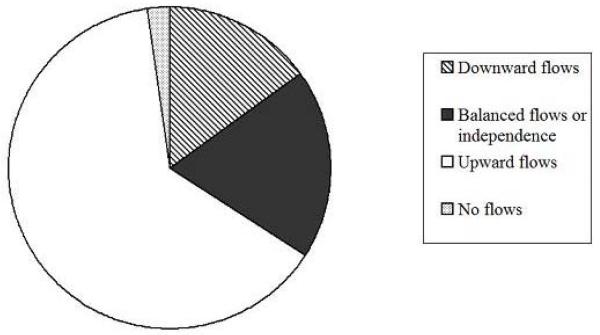

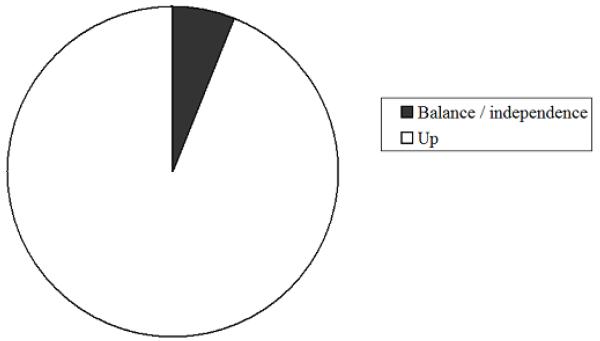

Figure 1 and Figure 3 illustrate the quantitative importance of flow types in our East Javanese and West Sumatran study communities. As a quick glance shows, there are striking differences. We shall examine Kidul first, before contrasting its pattern with that of Koto Kayo.

Figure 1. Distribution of net intergenerational support flow types among elderly people in Kidul, East Java, in 2000.

Source: Household survey 2000; N=51 elders.

Figure 3. Distribution of net intergenerational support flow types among elderly people in Koto Kayo, West Sumatra, in 2000.

Source: Household survey 2000, N=47 elders.

5.1 Kidul 2000

In Kidul, all three main support flow types are well represented. More than one third (35.6 percent) of elders in 2000 were net providers of intergenerational support within their family networks. Almost half of these involve support flows to adult children or grandchildren, i.e. to individuals whom one might expect to be independent or even providing support to elderly parents or grandparents. The largest group (44.4 percent) was made up of arrangements in which the generations are mutually dependent or independent of each other. Only 16 percent of elders were net recipients of support from children or grandchildren. This embraces older people who are physically dependent, as well as those who have no income and are unable to offset their material dependence by offering services in exchange. Finally, a small group of older parents, making up 4 per cent, were neither giving nor receiving any inter-generational support: they were the most vulnerable older people in Kidul.6 The different flow types may briefly be characterised in turn.

Net downward flows of wealth are to be expected in the life cycle of intergenerational relations, as some parents enter old age before all their children reach independence. Slightly more than half of elders in downward flow arrangements in Kidul in 2000 were responsible for school- or university-age children or grandchildren. Informal adoption, relatively late in life, contributes to the size of this group of elders, as does the common practice of grandparents raising grandchildren, either because the children’s parents have died, or because divorce or labour migration necessitate it (cf. Hermalin et al. 1998; Schröder-Butterfill 2004a). Almost ten percent of elders in Kidul live in a skipped generation household containing a young grandchild but not its parents. Remittances from adult children rarely covered grandchildren’s costs, let alone paid towards the upkeep of the elderly generation.

More surprising is the existence of a significant minority of elders engaged in net downward flows of support to mature children or grandchildren (cf. Beard and Kunharibowo 2001). In some cases children simply fail to achieve independence, a few of which are due to handicaps or mental illness. More important is divorce, as many adult children return to their parents’ home following marital break-up, especially if they have children. The economic crisis, which had not abated when the first survey round was conducted in 2000, led several adult children to return to the parental fold; others left their children to be cared for by grandparents while hoping to find work elsewhere. Javanese villagers emphasise the life-long responsibility that parents have towards their children, often stating that ‘parents can never be heartless’ towards their children in need. Parents are expected to assist their children to the limits of their ability, and those failing to bail out children in a crisis are harshly criticised.

The large category of balanced support flow arrangements hides considerable variation ranging from intense inter-dependence of the generations to very limited exchanges and far-reaching independence of old and young. In the Javanese nuclear family system, the ideal is for all children to leave the parental home some time after marriage and for generations to maintain close but self-sufficient existences (Geertz 1961; Jay 1969). Parents and children then engage in regular but small-scale exchanges of food, visits and occasional gifts of money. In some cases significant flows of support co-exist with an overall balance of flows. For example, in some family networks older parents provide far-reaching support to some children, while receiving assistance from others. Older women sometimes have responsibility for childcare and domestic tasks in exchange for material support from the younger generation, and multi-generational living arrangements are often characterised by the different generations contributing resources and labour more or less equally.

In contrast to joint family systems that prevail in much of mainland Asia, only a minority of older people were net recipients of intergenerational support in 2000. Visible dependence undermines status and damages social relations, which should ideally be based on reciprocity and balance. Elders therefore avoid becoming dependent for as long as possible, and flows shift upward only when ill health and inability to work become unavoidable. Even then, older family members try to make some contribution, however small. Elders suspected of being an unnecessary ‘burden’ are criticised.

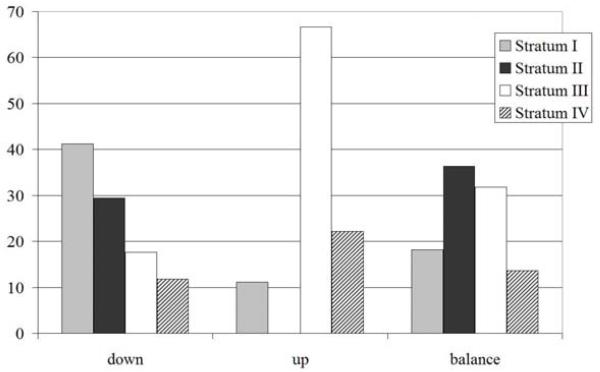

The economic correlates of the three main support flow types in Kidul are portrayed in Figure 2. This reveals that the diversity in support arrangements is in part shaped by elders’ differential economic capacities. Many older people who are net providers of material support to children or grandchildren are wealthy.7 Elders who receive a monthly pension or regular income from agricultural land are particularly likely to have dependants: 13 of the 18 elders in this situation were in downward flow arrangements, compared with only 4 out of 31 without such income. Yet downward flows of support are also found among elders who are merely getting by or even poor. Their ongoing responsibility to younger family members is an important source of vulnerability. Elders who are comfortably off or getting by predominate in arrangements where flows of support are balanced: these parents have sufficient resources to be independent, but are not rich enough to attract dependants. Where they live with children, their households are likely to benefit from multiple incomes or co-operation between the generations. The number of elders dependent on children or grandchildren is small (N=10) and clustered in the lower two strata (six and two individuals, respectively). Children of dependent elders in poorer strata are also likely to be poor, compounding their vulnerability.

Figure 2. Intergenerational support flow types by older people’s economic status, Kidul 2000.

Source: Household survey 2000.

5.2 Koto Kayo 2000

Turning now to the West Sumatran community, we find a strikingly different pattern of net support flows in older people’s networks. The Minangkabau come closest to Caldwell’s hypothesis that older generations are able to depend on support from their children. The picture is dominated by one kind of wealth flow type, namely arrangements where net flows of intergenerational support are upwards. In 2000, almost two-thirds of all elders surveyed received more support than they gave. This was despite the fact that the vast majority (92 percent) of elderly households also had control over agricultural land, and were therefore able to meet at least some of their daily needs independently. (The comparative figure for Kidul was 20 percent.) Only a small minority – 15 percent – were net providers of support, and one in five engaged in balanced exchanges or maintained intergenerational independence. Since it is unlikely that older people in West Sumatra are in fact in greater need of support, we need to consider the cultural and structural contexts producing this pattern.

As noted earlier, the Minangkabau of West Sumatra have a matrilineal extended family system (Sanday 2002; van Reenen 1996). Houses have traditionally been large and accommodated married sisters and their children. Men, when in the village, divide their time between their sisters’ and their spouse’s home, but spend most of the year away on labour migration (rantau). Minangkabau men are famed for being successful sojourners across the Indonesian archipelago and beyond. In the case of Koto Kayo, the majority of working-age men are engaged in cloth trade, which takes them to distant parts of Sumatra, major cities on Java (especially Jakarta and Bandung), and further afield to Malaysia (Indrizal 2004). In recent decades more and more women have also become engaged in labour migration. The net effect is that more than 60 percent of elderly respondents’ children are living away from the community, and among the wealthy the figure is as high as 90 percent (Kreager 2006: 46). Economic status of villagers depends on their network’s success at active participation in rantau, and thus it is primarily those without children or other relatives away who are poor. Given the high levels of outmigration of the young, one might expect a prevalence of financial and residential independence in the older generation. While almost forty percent of elders do live alone or just with a spouse, they nonetheless benefit from far-reaching support from younger generations. Unlike East Java, where migrants tend to send remittances only infrequently and of relatively low value (Frankenberg and Kuhn 2004), among the Minangkabau remittances are a major and integral component of labour migration. Indeed, migration networks are so well established that most major cities contain associations of migrants from a given community, via which material support to family networks and community institutions (notably the Mosque) are channelled.

The Minangkabau take considerable pride not only in their entrepreneurial success, but also in the strength of their family ties, which are not confined to members of the immediate family, but embrace members of the wider matrilineal kin network (Indrizal 2004). A key manifestation of a network’s success and solidarity is elderly parents’ ability to rely on a combination of remittances and local practical support, rather than having to continue to work. Quite unlike in rural East Java, dependence in old age is a source of satisfaction and respect. Where Javanese elders will emphasise their ongoing contributions (even when in fact they receive far-reaching practical or material support), Minangkabau elders will stress their reliance on the younger generation, even if their agricultural income means they could survive self-sufficiently. The ideal and statistical norm, as Figure 3 attests, is not independence, but reliance on children, grandchildren, nephews and nieces. This view is shared by the younger generation. As soon as they are earning, children in Koto Kayo feel compelled to provide their parents with monetary support, even if their parents don’t strictly speaking need it. Not to do so would be considered shameful. By providing generous support for the older generation, younger network members regard themselves as repaying the support they received as children and young adults, when support from parents and older kin facilitated the establishment of successful migration careers.

Downward flows of intergenerational support in Koto Kayo are associated with having immature children and children first embarking on labour migration. Unlike in East Java, we encountered no case of young grandchildren being left in the care of elderly grandparents, although sometimes older women were found to be living with an adult granddaughter. Balanced flows of intergenerational support tend to arise where elders are still working and have some children who are still dependent and some who already contribute. While it happens that children’s labour migration fails to produce a successful outcome, in most families this is compensated for by the remittances and support of other network members.

The socio-economic stratification of wealth flow types in the Sumatran community also differs strikingly from that in East Java. Because the numbers of elders in the survey in Strata I and IV are small, we combined Strata I and II, and III and IV, to compare wealthier and poorer households, respectively. As Table 1 shows, among the Minangkabau it is predominantly poorer elders who engage in downward or balanced flows of support, while it is well-off elders who additionally benefit from supportive networks. Poorer families are less likely to have children engaged in successful labour migration. A subgroup among the poorer families are those who moved into the village from impoverished communities elsewhere in West Sumatra. Such ‘newcomers’ – many of whom have lived in Koto Kayo since the 1940s – lack title to agricultural land and work as sharecroppers for other villagers. Their children, without the resources to leave, tend to follow their parents into agricultural work, which is poorly remunerated. Families characterised by relative intergenerational poverty are more likely, once all children are grown-up, to rely on mutual exchange between generations, rather than parental ‘retirement’ on the efforts of the young. Among poorer families engaged in agricultural work, parents and children often assist each other at harvest time and exchange seasonal produce, rather than money.

Table 1. Distribution of elders in Koto Kayo by support flow type and economic position (absolute numbers).

| Downward | Balanced | Upward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richer elders (Strata I & II) | 3 | 2 | 23 |

| Poorer elders (Strata III & IV) | 4 | 7 | 6 |

|

| |||

| Total | 7 | 9 | 29 |

Source: Household survey 2000.

6. Change over time

The patterns presented thus far provide only a snapshot of intergenerational support flows. These are not only anchored in a particular period – Indonesia during the economic crisis – but reflect circumstances at particular points in older people’s lifecourse. We would expect support flows and the nature of intergenerational ties to shift over time, as the capacities and needs of older people and their network members change. To capture the dynamic nature of support flows it is necessary to follow elders over time. In doing so the reliability or ‘strength’ of ties may better be assessed.

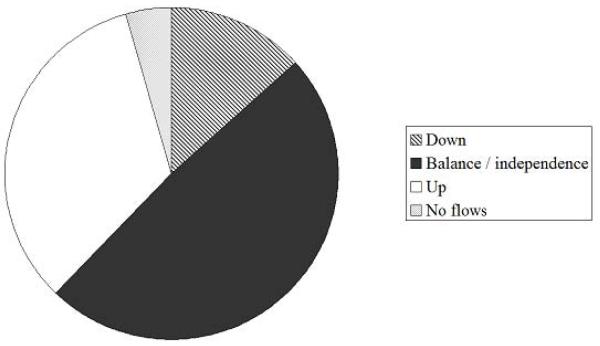

Figure 4 and Figure 5 provide updated summaries of older people’s support flow types in Kidul and Koto Kayo in 2005. A minority (13 percent) of households could not be re-surveyed due to death or migration, and additional respondents were therefore randomly recruited into the sample to make up for attrition. The diagrams capture only those elders who were reinterviewed five years after the initial surveys, since this provides a genuine longitudinal account.8

Figure 4. Distribution of net intergenerational support flow types among elderly people followed up in 2005, Kidul, East Java.

Source: Household survey 2005, N=45.

Figure 5. Distribution of net intergenerational support flow types among elderly people followed up in 2005, Koto Kayo, Sumatra.

Source: Household survey 2005, N=48.

6.1 Kidul 2005

As Figure 4 shows, over time the pattern prevalent in Kidul in 2000 is reinforced: balanced support flows are confirmed as the ideal and the statistical norm which is being achieved more often by 2005. There is a reduction in downward flows of intergenerational support in elders’ networks reflecting, as we shall see, life-cycle related reductions in the younger generations’ need for support, as well as the effects of economic recovery. One third of elders are now reliant on support from children, grandchildren or other younger generation network members. This increase in dependency is due to older people’s declining health and economic participation, but in some cases also reflects children’s growing capacity to provide for elderly parents. Examination of individual elders’ changes over time reveals that slightly more than half (25 out of 45) experienced no change in their net support flow state. The most significant source of change lies in the shift from being net providers of support to being in balanced or independent arrangements: nearly one quarter (11/45) of cases underwent this shift. Almost as many cases (9/45) went from situations of balance to upward flows of support. Both these types of shift are compatible with what one would expect concerning intergenerational support flows in old age over time, namely the declining need for parental supportive involvement in children’s lives and children’s strengthening capacity for support provision as children mature, and the growing need of support on the part of elders as they advance in age. Of concern are those elders who continue to engage in no support whatsoever (2/45) with younger network members. These elders are, as we note elsewhere, de facto childless and highly vulnerable in old age (Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill 2004; Schröder-Butterfill and Kreager 2005). Also potentially vulnerable are elders who continue to be net providers of intergenerational support in 2005 (5/45), as these are clearly providing far-reaching support not only over long periods of time, but also in advanced old age.

The following brief cases, grouped according to changes in flow types over time, exemplify some of the transitions and continuities.

6.1.1 From downward to balanced flows

In 2000, Nari, aged 70, and his wife, Tumi, in her early 60s, were caring for two young grandchildren while the grandchildren’s mother, a divorcée, scraped a living as scullery maid in a restaurant in the nearby district capital. Her contribution to her children’s upkeep, let alone her elderly parents’ cost of living, was sorely inadequate, and thus Tumi continued selling traditional herbal medicine (jamu). Nari, despite suffering from rheumatism, worked as odd-job man whenever there was work. None of the couple’s other four children were making significant contributions, as they were poor like their parents. The elderly couple occasionally received charitable support from a well-off nephew, sibling and the local Hindu temple. By 2005, the grandchildren’s mother had established herself as a fairly successful Javanese food trader in a Sumatran city. Although the elderly couple lamented not seeing their daughter for two years and often feeling tired from looking after their grandchildren permanently, they were now receiving three-monthly monetary transfers which covered the grandchildren’s and some of their own costs. Two of their other children were also doing better economically and providing small but regular monetary and food support. All in all, Nari and Tumi feel less vulnerable now than they did five years ago.

6.1.2 Downward flows in both periods

By contrast, there is no real sign of respite for Abdul and Ani, who in 1999 took on parenting responsibilities for their grandson after the tragic death of their daughter. While they gain satisfaction from watching their grandson thrive, his dependence on them is exacerbated by their youngest son’s continuing failure to achieve material and residential independence. Aged now in his mid-20s, he shows no sign of settling down in a job. He lost out by coming onto the job market as a high school graduate at the height of the economic crisis and failed to find work. From a fairly prosperous family he had ambitions of becoming a policeman. Unfortunately, his father, Abdul, suffered a severe stroke in 2001 and was not only unable to continue working as a farmer and village official, but also saw himself forced to sell the family’s remaining agricultural land to cover his medical bills. As a result that asset was no longer available to finance the son’s further education. To support her ailing husband, grandson and unemployed son, Abdul’s wife, Ani, who in 2000 was ‘merely’ a housewife, has developed a small business making cakes and catering for weddings in the village. The elderly couple receive considerable support from Abdul’s wealthy brother, who now pays for Abdul’s medication, but neither of their two married sons provide much assistance; indeed, one son moved away just as Abdul’s stroke raised the need for greater involvement from the younger generation.

6.1.3 From balanced to upward flows

In 2000, Yeni and Samad, aged circa 60 and 70, respectively, were at the heart of complex support flows within their multigenerational family network. They were living with an unmarried daughter, a son-in-law, whose wife (their daughter) was on international labour migration, and the grandson from that union. The son-in-law was often away with work, leaving them in charge of the grandson. Five other married children were providing them with financial and material support, as the elderly couple’s only income derived from selling the eggs their chickens laid. By 2005 Yeni and Samad’s involvement in support provision had considerably reduced. The coresident daughter had married and moved out, the migrant daughter returned, and the son-in-law and grandson moved out. Pre-existing health complaints had worsened to the point that Yeni was no longer able to shop and cook. Their only local daughter therefore now delivers cooked food every day, and the other children visit and provide money.

The transition to dependency has been less smooth for Sumiatun, a widow in her late 60s in 2000. Her only adopted daughter has quite a bad handicap and has therefore never married, nor held a regular job. She helps in the household of a wealthy neighbour and receives food, medication and pocket money in exchange. In 2000 Sumiatun was still able to work as agricultural labourer, and she pooled her income with whatever her daughter made. Domestic tasks were also shared between them. By 2005, Sumiatun’s health had deteriorated, preventing her from working. Having no income at all makes her dependent on others, but her intergenerational network is insufficiently resilient to afford her much security and comfort in old age. Her daughter’s material contributions remain minimal, although she continues to help with domestic tasks. Financially Sumiatun depends on gifts of money and food from nearby nephews and nieces, religious charity and on the generosity of a wealthy former boss for whom she worked as a domestic servant. This dependence on support from individuals outside her immediate family results in a loss of status and respect for Sumiatun and in very limited security.

6.1.4 Flows upward in both periods

In many ways Asemi’s situation in 2000 captured the typical image of the ‘dependent granny’ embedded in a large network of supportive kin. A widow in her seventies, she was frail but not actually in ill health. She had long ceased working and for many years helped the daughter she was living with look after the grandchildren. Three married sons lived close by, a further daughter a few kilometres away. While no longer contributing much to the family network, Asemi’s needs were minimal, with daily food provided by the coresident daughter, and a little spending money and clothing by the other children. By 2005 her dependency had intensified dramatically, as she had suffered strokes which left her partially paralysed. She required intense personal care, like feeding, bathing and carrying to the toilet. These tasks fell almost exclusively on her coresident daughter’s and granddaughter’s shoulders: her other children, children-in-law and grandchildren quickly faded into the background. The way Asemi was treated in the family had also worsened: she was no longer the indulged granny, but a burden. Her daughter talked disparagingly about her incontinence and admitted locking her mother in her room whenever she had to be left on her own.

These five cases underline the variability of support flows within a single community and over time. Yeni and Samad represent the paradigm or ideal case of strong family ties in East Java: different members of the family network variously give or receive assistance, depending on their needs and capacities. Elders maintain strong involvement in support provision to younger family members well into old age, but all or most children step in to secure their parents’ wellbeing once support is needed. Alignment of ideal and practice is, however, often prevented by poverty or incapacity in the younger generation, as the examples of Nari and Tumi, and of Sumiatun show. The strength of moral and felt ties between the generations cannot be denied in these cases, but their translation into old-age security is contingent on the younger generation’s economic success, which in turn is shaped by wider economic conditions. Increases in elders’ need for assistance in old age, moreover, are not necessarily met by increased willingness to help on the part of younger network members. As noted earlier, the strength of intergenerational ties is uncertain and subject to children’s competing demands and priorities. In the case of Abdul, it is primarily intra-generational support from his wife and brother which secures his welfare following his stroke, while his sons, who are not poor, do very little. Similarly, in Asemi’s case, it is only a small subset of her supportive network which responds to her care needs, indicating that what had appeared as a strong network turned out to be less committed than expected. In a cultural context in which independence is valued, outright dependence is never a positive outcome for the elderly person. While the existence of charitable support in the wider kindred and community attests to the continuing importance of community solidarity, for elders dependent on such diffuse support it spells loss of status and only minimal security.

6.2 Koto Kayo 2005

Koto Kayo has also seen a shift in support flow types that intensifies the existing pattern. As Figure 5 shows, there are now no longer any elders engaged in net provision of support, and only a handful who are independent or participating in even exchanges. The vast majority (94 percent) are net recipients of support. This suggests a family system and individual family networks unusually capable of sustaining elderly members once children have gained maturity. In reality, as the following cases illustrate, even in this community the meaning and effect of strong ties varies between economic strata.

6.2.1 From downward to upward flows

Zahid and his wife have three sons. In 2000 they lived on the income from Zahid’s wife’s rice fields and on his savings from rantau days. One son was at university, another son had just gone bankrupt and therefore needed his parents’ support. The third son was in the process of establishing himself economically. By 2005, the situation of the elderly couple had hardly changed: they still enjoyed good agricultural income. However, the son at university had graduated and become a trader, the bankrupted son was back on his feet and the third son had become successful on rantau. All three sons were therefore now sending remittances to their parents. The flow of support had firmly reversed.

In 2000, Amin and his wife were getting by on his income from sharecropping someone else’s land in Koto Kayo. One daughter, living close by, often visited and provided occasional money and food. Her parents had recently given her a plot of land and help with building a house. The other daughter never provided any money, as she was very poor. Instead it was Amin who was helping her, chiefly by providing money for the grandchildren. The elderly couple’s son, away on rantau, was only able to provide token support once a year. Five years on, Amin had ceased working due to ill health, and his wife had died. He was living alone, but his nearby daughter provided him with daily food and cleaned his house. The son, away on rantau, had settled down as a reasonably successful trader, and was able to send a considerable sum of money [Rp. 70-100,000, £4-6] every couple of weeks. Various grandchildren were also now giving generous monetary gifts. Only the one daughter was still unable to help: she had recently moved to a different part of Sumatra and was not yet successful.

6.2.2 From balanced to upward flows

Fatimah is a comfortably-off widow with two sons. She owns extensive rice fields, the income from which covers her daily needs. In 2000 she was additionally receiving a little financial support from her sons, but in exchange she was giving money to a granddaughter and a matrilineal relative living in her house. In 2005 she complained that the harvests from the land had deteriorated, making her more dependent on support. More significantly, one of her sons had become very successful as village official and owner of a rice hulling enterprise. He was now providing her with regular money and rice. Sadly, the support from her other son had evaporated, as relations between mother and son had soured following the son’s marriage to a woman his mother didn’t approve of. Except for sharing her house with a relative, Fatimah was no longer providing any support to others.

In the case of Yaris, loss of independence is not associated with material security. Yaris is a poor elderly man with seven children. In 2000 he was still working as a sharecropper. Three of his children were on rantau, the other four were living with his wife or in a neighbouring village. Yaris chose to live on his own in a hut near the land he was working, returning to his wife’s house once or twice a week. At the time his children were not well off, so mostly they provided help in the form of labour or rice, rather than money. In exchange Yaris would help his children at harvest time, would give occasional money to his grandchildren, and rice to his matrilineal nephews and nieces. Five years on his situation has changed dramatically. His health having declined, Yaris is no longer able to work, and his wife has died. He has moved in with his daughter, Nurhayati, and now depends heavily on the support of his children, and especially on Nurhayati’s. One son sends money every month, the others only when they can spare some. None of the children are well off. His nephews and nieces now sometimes provide him with rice at harvest time. Despite his health problems, Yaris often restrains himself from seeking medication, as money is scarce.

The cases in our Sumatran community illustrate very clearly the contrast with East Java. Here downward flows of intergenerational support are a clearly circumscribed phase of the family lifecourse: as soon as children are independent, flows are from the younger to the older generation. Indeed, support from the younger generation may arise quite independently of parents’ need for assistance. As in Java, not all children who have previously benefited from parental assistance provide support, but overall family networks appear more reliable and able to compensate for unsuccessful or uncommitted members. Larger family sizes and the inclusion of matrilineal kin within circles of obligation contribute to the greater security of elders. However, even in a setting in which family commitment is a source of pride and ethnic identification, norms alone do not necessarily result in elders’ security. Poverty in the different generations of elders’ networks may prevent the provision of meaningful support.

7. Conclusion

Javanese and Minangkabau communities reveal strikingly different patterns of adjustment to older people’s changing roles and capacities. The main difference lies in attitudes to receiving major support from other family members. In the East Javanese community, positive relationships are supposed to enable generations to act independently, albeit in ways consistent with the overall family solidarity. People do not wish to be dependent on other family members without being able to make significant continuing return contributions. Inability to participate in exchanges impacts on a person’s and family’s reputation and social status. Prevailing inter-generational support accordingly shows a balance of flows, often extending very late in life, even amongst poorer strata where elders’ economic opportunities are severely limited. This ‘balance’ is not strict material reciprocity, but varies according to different forms of participation (child care, simple agricultural tasks, shop minding etc.) that give members of different generations a valued role. For the Minangkabau, in contrast, the immense importance for the whole family of the younger generation proving itself successful on rantau inevitably means that elders accept major upward flows of support from children as a positive value – even where the elders are themselves wealthy. Comparison, in short, shows that both balanced and upward flows can express the continuity of strong family ties, and as we have seen, with the increasingly advanced age of an elderly cohort these values tend to be reinforced.

Interpreting the co-existence of several flow patterns in both communities requires attention to differences of status and associated demographic factors. In this analysis we have not examined network structure and function directly, focussing rather on the outcome of network processes.9 Diverse support flow arrangements characterise both communities. In East Java, despite the preference for balance between the generations, downward flows continue to be provided by more than one third of all elders. Some of these flows reflect the advantages of elders enjoying greater wealth, but even in poorer strata older people commonly support their divorced or out-of-work children and grandchildren for extended periods. Older people are more likely to adopt kin in advance of difficulties if close family are likely to be otherwise committed (Schröder-Butterfill 2004a). Upward flows to the poorest elderly, which usually become necessary because of physical incapacity, tend to be motivated by charity and pity, rather than strong family links, and are often minimal and bring unavoidable loss of status.

Upward flows in the East Javanese case are thus not unequivocal signs of traditional family values, nor are downward flows an index of modernisation. Both may refer to families in which normative maintenance of balanced exchanges has proven impossible, or to families in which more or less temporary adjustments are in process. In the Minangkabau case, the presence of downward and balanced flows in 2000 (involving 15 and 27 per cent of elders, respectively), refer to poorer strata unable to participate in lucrative rantau activities; such flows may be crucial to survival, but again reinforce the separation of these families from primary Minangkabau values of entrepreneurial success and upward flows of remittances. The prevalence of upward flows, contrary to the expectations of wealth flow theory, characterises a culture that has long taken an active role in the national and international economy.

What lessons can be drawn from this comparison of Indonesian communities for a general understanding of the strength of ties that link older and younger generations? The emphasis in this paper is on the importance of including several kinds of variation in any answer we give to this question. First, constituent national groups like the Minangkabau and Javanese may have contrasting normative valuations of what they consider positive family relationships. Second, these differences can be tracked, up to a point, in prevailing flows of inter-generational support. There is, however, no necessary relation between strong family norms and particular support arrangements. Preferred flow types – balanced (Java), up (Minangkabau), down (many parts of Europe) – may each be indicative of strong ties. Each co-exists with other flow types. To the extent that preferences and practices agree, we arrive at a reasonably unambiguous definition of ‘strong ties’ as the concordance of normative values and practices. There is a danger, however, in adopting this definition since, as researchers, we are effectively taking sides with the better-off sectors of the population who are in a better position to achieve cultural preferences.

Data on a third form of variation are therefore necessary: the support flow patterns characteristic of the different socio-economic strata and networks to which older people belong. These data help us to see why in many cases norms are not observed, even though they continue to be valued in principle. Put another way, by adjusting flow patterns, families arrive at more or less acceptable ways of coping with older members’ declining capacities, amongst the several potential health, economic, marital, and other problems with which they deal. Looking at the continuity of preferred flow types in the two communities over the relatively short period 2000-2005 suggests that flows have enabled families to accommodate the economic crisis of 1997-2000, as well as the growing frailty and other problems of the elder generation – albeit at a cost to some older people in poorer strata. Norms emphasizing the fundamental importance of family ties do not appear to be in retreat in either community, but not everyone is able to observe them with equal success.

Earlier in the paper we remarked that Indonesia fails to conform in several respects to prevailing images of Asian family systems. Is the diversity of its support arrangements and accompanying norms also against the trend? We think not, but until variation in support flows and related family ties are explored within as well as between mainland Asian communities, it will remain difficult to be sure.

8. Acknowledgements

Indonesian village data presented in this paper were collected in Ageing in Indonesia, 1999 – 2007, with the generous support of the Wellcome Trust and the British Academy. We are grateful to Edi Indrizal and Tengku Syawila Fithry, our colleagues at Andalas University, Padang, who conducted the field research at the West Sumatran field site.

Footnotes

Minangkabau preference is, however, for coresidence with a daughter, and forms an exception to the majority Indonesian pattern.

From the beginning, Caldwell (1977) expressed profound reservations over whether strictly mensurational approaches to topics like family income and child labour inputs were even possible, and the conflicting interpretations of findings that remain in the literature have indeed tended to revolve around differences in methodology. His discussion of the issues remains worth reading. Perhaps the nub of the problem can be stated as follows. Because families frequently rely on several sources of income from several members, and these members do not necessarily reside together, informants, even when making a sustained effort to provide accurate information, can in general provide only estimates of income and expenditure for all members. There are many readily appreciable reasons why they may not give complete or entirely accurate information on their own income and expenditure. Without additional checks, provided by interviews with other family members, observation of family relationships etc., the reliability of such estimates is simply unknown. Yet, particularly in the compilation and analysis of household survey ‘data’, the estimated character of much (how much?) of the information passes without comment. A notable exception is Deaton (1997).

Extended fieldwork of more than a year’s duration, together with return visits of shorter duration, have enabled the development of comparable quantitative and qualitative data bases. Semi-structured interviewing achieved substantial coverage of the elderly, between 80 and 97 percent in the respective communities; repeated in-depth interviews were conducted with between 20 and 60 elderly in each site, complemented by in-depth interviews with one or more other adult family members in most cases. Collection of life histories enabled mapping of kin networks which could be checked by observation of exchanges. Fieldwork also made possible observation of local events, and enabled familiarity with problems and adjustments to changing circumstances that make up much of people’s daily lives. Randomised surveys of household economy and inter-household exchanges with 50 ‘young’ households and 50 ‘elderly’ households in each of the three communities then served two important functions: they substantiated differences in social and economic status within and between networks which shape family and community responses to older people’s needs; and they enabled quantitative analysis of the role of support from absent network members. Two survey rounds, in 2000 and 2005, were accompanied by in-depth follow-up interviews. The timing of the first round coincided with the impact of Indonesia’s economic crisis (Ananta 2003).

An earlier publication gives slightly different figures for the different flow types (Schröder-Butterfill 2004b). This is partly because childless elders were treated as a separate category, partly because results then were based on all elders in the community. Here we rely on the sub-sample of elders captured in the household survey to ensure comparability between the two communities.

Socio-economic strata are defined by aligning economic differences as revealed in the surveys with local terms of reference that people used in the course of in-depth interviews to describe their own and others’ relative social position. Interpretation of survey data and in-depth interviews is enhanced by observation of local events and processes in the course of ethnographic fieldwork. No explicit scheme of social classification is normative in the communities, but four distinctions recur in everyday speech: a. wealthy; b. comfortable; c. getting by; and d. dependent on charity. A more detailed account of the strata is given in Kreager (2006: 8-9).

Including new respondents in the 2005 measurement of wealth flows gives the following results: In Kidul, 19.6 percent of cases (N=56) then involve downward flows, 46.4 percent balanced flows, 30.4 percent upward flows and 3.6 percent no flows. In Koto Kayo, 10.4 percent of cases (N=48) are then balanced, 87.5 percent upward flows and 2.1 percent no flows.

See Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill (2007) for a network analysis of the 2000 round of survey and ethnographic data.

References

- Ananta A, Anwar EN, Suzenti D. Some Economic Demographic Aspects of ‘Ageing’ in Indonesia. In: Jones G, Hull T, editors. Indonesia Assessment: Population and Human Resources. Australian National University and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; Canberra and Singapore: 1997. pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ananta A. The Indonesian Crisis: A Human Development Perspective. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; Singapore: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Beard VA, Kunharibowo Y. Living Arrangements and Support Relationships among Elderly Indonesians: Case Studies from Java and Sumatra. International Journal of Population Geography. 2001;7(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cain M. Risk and Insurance: Perspectives on Fertility and Agrarian Change in India and Bangladesh. Population and Development Review. 1981;7(3):435–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cain M. The Consequences of Reproductive Failure: Dependence, Mobility, and Mortality among the Elderly of Rural South Asia. Population Studies. 1986;40(3):375–88. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC. Toward a Restatement of Demographic Transition Theory. Population and Development Review. 1976;2:321–66. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC. On Net Intergenerational Wealth Flows: An Update. Population and Development Review. 2005;31(4):721–40. [Google Scholar]

- Collard D. Generational Transfers and the Generational Bargain. Journal of International Development. 2000;12:453–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cribb R. Historical Atlas of Indonesia. Curzon; Richmond, Surrey: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmalingam A. Old Age Support: Expectations and Experiences in a South Indian Village. Population Studies. 1994;48(1):5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg E, Kuhn R. The Implications of Family Systems and Economic Context for Intergenerational Transfers in Indonesia and Bangladesh. California Center for Population Research; Las Angeles: 2004. Online Working Paper Series CCPR-027-04. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz H. The Javanese Family: A Study of Kinship and Socialization. Free Press of Glencoe; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy E, Murphy M, Shelton N. Looking beyond the household: Intergenerational perspectives on living kin and contacts with kin in Great Britain. Population Trends. 1999;97:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnal J. Two kinds of preindustrial household formation system. Population and Development Review. 1982;8(3):449–494. [Google Scholar]

- Hermalin A, Roan C, Perez A. The Emerging Role of Grandparents in Asia. Population Studies Center, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, Michigan: 1998. Comparative Study of the Elderly in Asia Research Reports 98-52. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman C, Guest P. The Emerging Demographic Transitions of Southeast Asia. Population and Development Review. 1990;16(1):121–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo G. Population Mobility and Wealth Transfers in Indonesia and Other Third World Societies. East-West Population Institute; Honolulu: 1983. Working Paper No. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Hull T, Hull V. Changing Marriage Behavior in Java: The Role of Timing of Consummation. Southeast Asian Journal of Social Sciences. 1987;15(1):104–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hull T, Tukiran Regional Variations in the Prevalence of Childlessness in Indonesia. Indonesian Journal of Geography. 1976;6(32):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indrizal E. Problems of Elderly without Children: A Case Study of the Matrilineal Minangkabau, West Sumatra. In: Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Berghahn; Oxford: 2004. pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jay R. Javanese Villagers: Social Relations in Rural Modjokuto. M.I.T. Press; Cambridge MA: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GW. Modernization and Divorce: Contrasting Trends in Islamic Southeast Asia and the West. Population and Development Review. 1997;23(1):95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Inter-generational contracts, demographic transitions and the ‘quantity-quality’ tradeoff: parents, children and investing in the future. Journal of International Development. 2000;12:463–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H, Bock J. Fertility Theory: Caldwell’s theory of intergenerational wealth flows. In: Hoem JM, editor. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier Science; New York: 2001. pp. 5557–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kreager P. Where are the Children? In: Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Berghahn; Oxford: 2004. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kreager P. Migration, social structure and old-age support networks: A comparison of three Indonesian communities. Ageing and Society. 2006;26(1):37–60. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X05004411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Berghahn; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E. Gaps in the Family Networks of Older People in Three Rural Indonesian Communities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2007;22(1):1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10823-006-9013-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. Intergenerational Transfers and the Economic Life Cycle: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. In: Mason A, Tapinos G, editors. Sharing the Wealth: Demographic Change and Economic Transfers between the Generations. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2000. pp. 17–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, Kramer K. Children’s Economic Roles in the Maya Family Life Cycle: Cain, Caldwell, and Chayanov Revisited. Population and Development Review. 2002;28(3):475–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li T. Malays in Singapore: Culture, Economy and Ideology. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Livi-Bacci M. A Concise History of World Population. Blackwell; Oxford: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A. Gender and Changing Generational Relations: Spouse Choice in Indonesia. Demography. 1991;28(4):549–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marianti R. In the Absence of Family Support: Cases of Childless Widows in Urban Neighbourhoods of East Java. In: Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Berghahn; Oxford: 2004. pp. 147–71. [Google Scholar]

- McNicoll G, Singarimbun M. Fertility Decline in Indonesia: Analysis and Interpretation. National Academy Press; Washington D.C.: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Nag M, White B, Peet RC. An Anthropological Approach to the Study of the Economic Value of Children in Java and Nepal. Current Anthropology. 1978;19(2):293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Sanday PR. Women at the Center: Life in a Modern Matriarchy. Cornell University Press; Ithaca: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill E. Adoption, Patronage, and Charity: Arrangements for the Elderly Without Children in East Java. In: Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Berghahn; Oxford: 2004a. pp. 106–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill E. Inter-generational Family Support Provided by Older People in Indonesi. Ageing and Society. 2004b;24(4):497–530. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X0400234X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill E. The impact of kinship networks on old-age vulnerability in Indonesia. Annales de Démographie Historique. 2006;2005(2):139–63. doi: 10.3917/adh.110.0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill E, Kreager P. Actual and De Facto Childlessness in Old Age: Evidence and Implications from East Java, Indonesia. Population and Development Review. 2005;31(1):19–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Reenen J. Central Pillars of the House: Sisters, Wives and Mothers in a Rural Community in Minangkabau, West Sumatra. Research School CNWS; Leiden: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Sanso P. ‘They don’t need it, and I can’t give it’: Filial Support in South India. In: Kreager P, Schröder-Butterfill E, editors. Ageing Without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Berghahn; Oxford: 2004. pp. 77–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DL. Factory Daughters: Gender, Household Dynamics, and Rural Industrialization in Java. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1992. [Google Scholar]