Abstract

Intestinal Peyer’s patches are essential lymphoid organs for the generation of T cell-dependent immunoglobulin (Ig) A production for gut homeostasis. Using IL-17 fate reporter mice we show here that endogenous TH17 cells in lymphoid organs of naïve mice home preferentially to the intestine and are maintained independently of IL-23. In Peyer’s patches such TH17 cells acquire a T follicular helper (TFH) phenotype and induce the development of IgA-producing germinal center B cells. Mice deficient in TH17 cells fail to generate antigen specific IgA responses, providing evidence that TH17 cells are the crucial subset required for high affinity T cell-dependent IgA production.

Disruption of mucosal homeostasis can lead not only to infections, but also chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer. Intestinal homeostasis is maintained by the immune system and the barrier function of epithelial cells. A large number of innate and adaptive immune cells reside in mucosal tissues and establish an immunological network to maintain healthy conditions. Amongst the adaptive immune cells, B cells producing IgA are an important player in maintenance of homeostasis and mucosal host defense1 and the lamina propria (LP) of the small intestine (SI) is home to a substantial proportion of TH17 cells present in non-immune mice.

IgA in the dimeric form is the dominant immunoglobulin isotype secreted into the intestinal lumen. The differentiation of T cell-dependent IgA-secreting B cells occurs in the Peyer’s patches (PP) of the small intestine. Selective deficiency of IgA is the most common form of primary immunodeficiency, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 600 individuals in the western world. Although symptoms are rarely severe, individuals with symptomatic selective IgA deficiency can suffer from recurrent pulmonary and gastrointestinal infections2. TH17 cells play a crucial role in the mucosal host defence as well as in the development of autoimmune diseases3. Under steady-state conditions TH17 cells are preferentially found in the lamina propria of the small intestine where their development depends on the presence of commensal microbiota, in particular on segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB)4. Interestingly SFB also stimulate a large amount of total intestinal IgA5.

The primary function of immune cells in the PP is surveillance of the intestinal lumen, which involves the induction of IgA antibody responses. IgA is important for the neutralization of toxins and response to pathogens, but also critically involved in shaping the diversity of the commensal microbiota6-7. Upon activation of B cells in the context of cognate T cell help, germinal centres (GCs) are generated and the induction of the activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) in GC B cells promotes somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination of immunoglobulin genes. The majority of B cells in the PP differentiate into IgA-producing cells in the presence of T cell help, whereas T-independent IgA-producing B plasma cells, which are B220− can differentiate in the gut lamina propria without the generation of the germinal centers8-10. IgA-producing B cells in germinal centers undergo extensive somatic hypermutation10, resulting in higher antibody affinity.

Here we show that the majority of TH17 cells found in lymphoid organs of non-immune mice were dependent on gut microbiota and had a natural preference for the small intestine as upon adoptive transfer they selectively homed to this site. Intestinal TH17 cells underwent deviation towards a follicular helper T cell phenotype (TFH) in Peyer’s patches where they induced germinal centers (GC) and the development of host protective IgA responses. In marked contrast to pathogenic TH17 cells developing in the course of EAE, which are highly dependent on IL-2311-12, intestinal TH17 cells did not require IL-23 for their maintenance or for plasticity towards a TFH profile. Mice deficient in TH17 cells had a pronounced deficiency of antigen-specific intestinal IgA following immunization with cholera toxin, emphasising that TH17 cells are the helper T cell subset responsible for inducing the germinal center B cell switch towards high affinity, T cell-dependent IgA.

Results

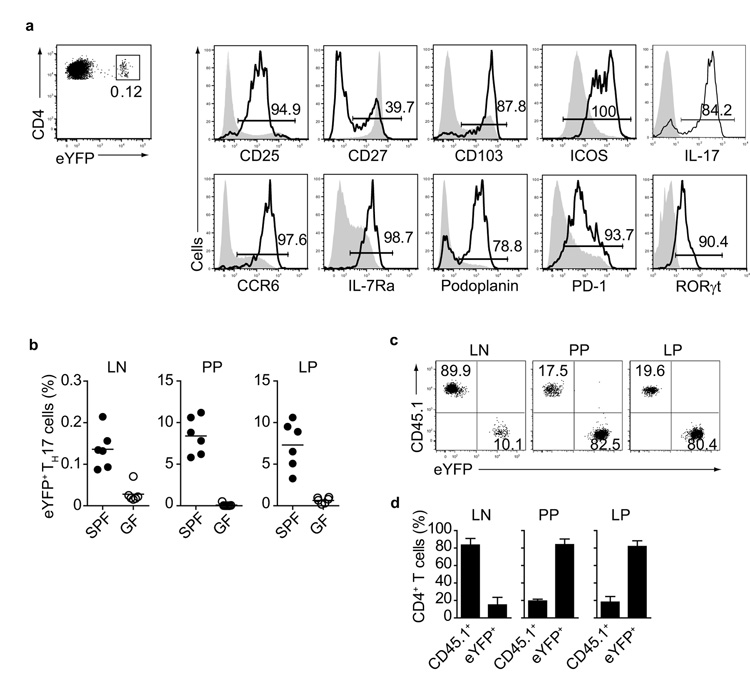

TH17 cells in non-immune mice have gut-homing properties

TH17 cells constitute approximately 0.1 % of CD4+ T helper cells in the peripheral lymph nodes (LN) and spleen in non-immune IL-17 fate reporter mice (Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice) in which IL-17-producing cells are permanently marked as eYFP+ cells12. This system is a powerful tool to track TH17 cells and investigate potential plasticity towards alternative effector functions, as detection of these cells does not depend on staining for intracellular IL-17. Flow cytometric analysis of eYFP+ TH17 cells from LN of Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice showed almost uniform surface expression of CCR6, IL-7Rα, CD25, CD103 and ICOS as well as expression of the signature cytokine IL-17 and the transcription factor RORγt (Fig.1a). Expression of CCR6 and CD103 suggested gut homing capacity, because the CCR6 ligand CCL20 is known to be expressed in the small intestine13. As intestinal TH17 cells are dependent on the gut microbiota and absent in germfree mice4, we compared the proportions of eYFP+ TH17 cells in LN, PP and LP of SPF or germfree Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice. eYFP+ TH17 cells were undetectable in PP and LP and also almost completely absent from LN of germfree Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice (Fig.1b). To test the homing properties of TH17 cells compared with other memory type T cells from non-immune mice, we sorted eYFP+ TH17 cells and eYFP− CD4+ T cells with an activated phenotype (CD44high) from LN of Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice (distinguished by expression of the allotypic marker CD45.1) and adoptively co-transferred them in a 1:1 ratio into Tcra-deficient hosts (CD45.2), which lack conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. eYFP+ TH17 cells preferentially reconstituted the gut-associated tissues, such as the LP and PP of the small intestine, but not the peripheral lymph nodes where the cells had originally resided (Fig.1c,d). In contrast, eYFP− CD44high CD45.1+ non-TH17 cells preferentially seeded peripheral LN (Fig.1c,d). Thus, the majority of TH17 cells found in lymphoid organs of non-immune mice have gut-homing properties.

Figure 1. Preferential migration of eYFP+ TH17 cells into gut-associated tissues.

a) Flow cytometry of CD4+ eYFP+ T cells (solid line) and CD4+ CD44high eYFP− T cells (shaded line) isolated from LN and spleen of Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice. The percentage of cells expressing the indicated marker is shown in the histogram. Isotype controls were used as negative controls indicated by placement of the bars. (b) Proportion of eYFP+ TH17 cells in LN, PP and LP of SPF and germfree (GF) Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice. (c,d) Flow cytometry of CD4+ T cells in LN, PP and LP cells of Tcra−/− mice reconstituted with CD4+ eYFP+ TH17 cells and CD45.1+ eYFP− CD44high CD4+ T cells, as assessed three months after transfer. Mean values +/− SD for three individual mice are shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

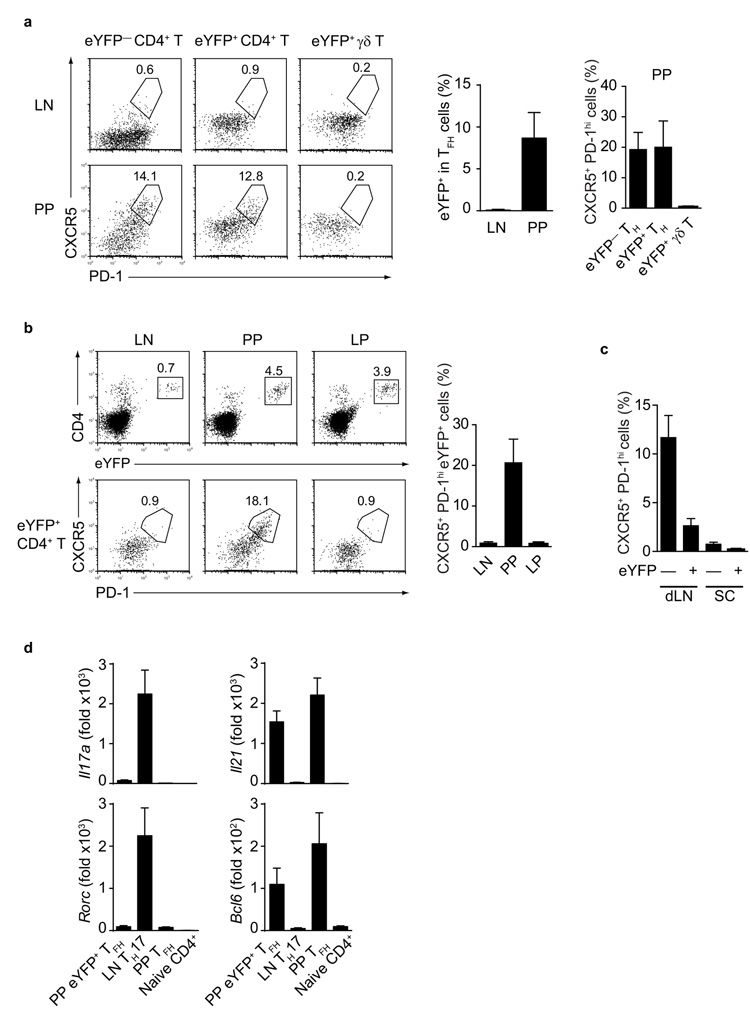

Intestinal TH17 cells deviate to TFH in Peyer’s patches

The preferential accumulation of TH17 cells in PP prompted us to examine the possibility that they might play a role in helping germinal center B cell differentiation. T follicular helper (TFH) cells reside in germinal centers and play an essential role in germinal center B cells differentiation and their distinguishing features are the expression of CXCR5, PD-1, IL-21, ICOS and the transcription factor Bcl614-16. We determined that about ~13-20% of eYFP+ TH17 cells as well as a similar proportion of eYFP− cells present in the PP of non-immune Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice expressed CXCR5 and PD-1, whereas PP eYFP+ γδ T cells did not express these TFH markers (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Reprogramming of TH17 profiles to TFH phenotype in the Peyer’s patches.

a) Flow cytometry of CD4+ CD44high eYFP− T cells (left panel), CD4+ eYFP+ cells (middle panel) and eYFP+ γδ T cells (right panel) showing expression of CXCR5 and PD-1 in LN (upper row) or PP (lower row) of Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice. Mean values +/− SD of CXCR5+ PD-1high cells are given in histograms. b) Flow cytometry of CD4+ eYFP+ T cells (upper panel) and CD4+ eYFP+ T cells expressing CXCR5 and PD-1 (lower panel) in LN, PP, and LP of Tcra−/− mice transferred with eYFP+ TH17 cells and analysed three months after transfer. Mean values of CXCR5+ PD-1high eYFP+ cells +/− SD are shown in histograms. c) Proportion of CXCR5+ PD-1high eYFP− CD44high CD4+ or eYFP+ CD4+ T cells in draining LN or spinal cord of Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice 20d after immunization with MOG+CFA. d) Quantitative PCR analysis for expression of indicated mRNA in FACS purified CXCR5+ eYFP+ (PP eYFP+ TFH), CXCR5− eYFP+ (LN TH17), CXCR5+ eYFP− (PP TFH) and naïve CD4+ T cells from Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice. mRNA expression is relative to Hprt. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

In order to verify the developmental origin of these cells, we sorted CXCR5− eYFP+ TH17 cells from LN of non-immune Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice, adoptively transferred them into Tcra-deficient hosts and subsequently determined expression of CXCR5 and PD-1 in different tissues of the adoptive hosts. Although eYFP+ TH17 cells homed to both PP and lamina propria of the adoptive hosts, conversion of eYFP+ cells to a TFH phenotype occurred exclusively in the PP environment (Fig. 2b). It should be noted that the small proportion of CD4+ eYFP− cells detected in the hosts after adoptive transfer are not donor derived T cells that lost eYFP expression, but CD4+ non-T cells present in the host.

In order to test to what extent plasticity of eYFP+ TH17 cells towards a TFH profile could occur in other tissues as a consequence of immunization, we induced EAE in Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice by immunizing with MOG+CFA. This induces an antibody response to MOG in addition to EAE and TH17 cells are thought to be involved in development of ectopic lymphoid follicles in the CNS17. Analysis of LN and spinal cord from Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice with EAE showed that about 4-7% of CD4+ T cells in the LN and 60% of CD4+ T cells in the spinal cord were eYFP+. However, about 2-4% of eYFP+ cells in LN, and none in the spinal cord, had a TFH signature (CXCR5+ PD-1high). In contrast, a substantial proportion (10-15%) of eYFP− CD4+ T cells had a TFH profile (Fig.2c). These observations suggest that TH17 plasticity towards TFH preferentially takes place in the PP environment.

We next analysed TH17 gene signatures in sorted CXCR5+ eYFP+ T cells isolated from PP (PP eYFP+ TFH), LN eYFP+ TH17 cells (LN TH17), non-TH17 PP eYFP− CXCR5+ TFH cells (PP TFH), as well as naïve CD4+ T cells, all isolated from non-immune Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice. eYFP+ CD4+ T cells with a TFH surface phenotype had down-regulated Rorc and Il17a mRNA and up-regulated the TFH signature genes Bcl6 and Il21, similar to non-TH17 related PP TFH cells (Fig.2d). Taken together, these data demonstrate that plasticity of TH17 towards a TFH-like phenotype takes place continuously in the PP environment under steady state conditions.

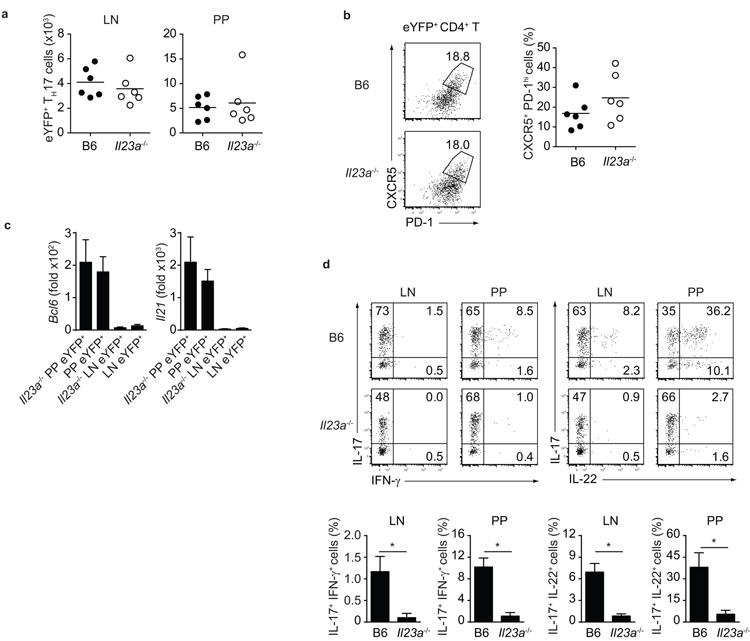

Maintenance of intestinal TH17 and deviation to TFH are IL-23-independent

TH17 cell plasticity in autoimmune settings is strongly dependent on IL-2312. In order to test whether IL-23 is similarly involved in plasticity of intestinal TH17 cells towards TFH, we analysed Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice crossed onto a p19 (Il23a)-deficient background. Firstly, and in contrast to the well-defined role of IL-23 in TH17 maintenance in autoimmune settings, IL-23 was dispensable for the survival of intestinal TH17 cells, as similar numbers of TH17 cells were present in LN and PP of Il23a-deficient and wild-type Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice (Fig.3a). Furthermore, phenotypic conversion to a TFH phenotype occurred to the same extent in IL-23-deficient and wild-type Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice (Fig.3b) and TH17 cells with the TFH phenotype in Il23a−/− reporter mice upregulated Bcl6 and Il21 expression similar to TH17 cells from wild-type reporter mice (Fig.3c). In contrast, in accordance with previous observations12, TH17 cells were unable to deviate towards IFN-γ expression and did not express IL-22 in Il23a-deficient mice (Fig.3d). These data indicate that the intestinal, steady-state population of TH17 cells has distinct features from the TH17 cells elicited by immunization in the periphery.

Figure 3. IL-23 is dispensable for homeostatic maintenance and plasticity of intestinal TH17.

a) Number of eYFP+ TH17 cells in LN and PP of Il17aCreR26ReYFP (B6, closed dots) and Il17aCreR26ReYFPIl23a-deficient (Il23a−/−, open dots) mice. b) Flow cytometry of eYFP+ CD4+ T cells showing expression of CXCR5 and PD-1 in PP of B6 and Il23a−/− mice. c) Quantitative PCR analysis for expression of indicated mRNA in FACS purified PP or LN eYFP+ CD4+ T cells from B6 and Il23a−/− mice. d) Flow cytometry of eYFP+ CD4+ T cells from LN or PP of B6 and Il23a−/− mice showing intracellular staining for IL-17, IFNγ and IL-22. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. *, p-value < 0.01.

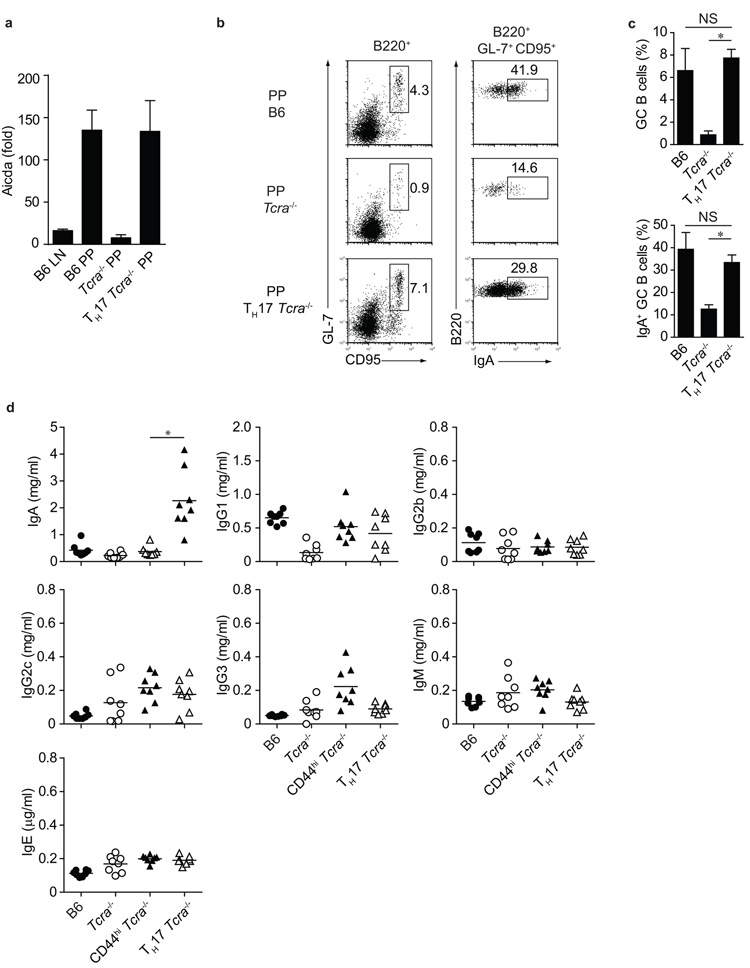

PP ex-TH17 cells induce IgA production by GC B cells

The dependency of intestinal TH17 cells on commensal bacteria raises the possibility that TFH cells developing from gut homing ex-TH17 cells may be specialized for helping B cell IgA responses in PP germinal centers. We therefore analysed B cell expression of Aicda, which is required for somatic hypermutation, gene conversion and class-switch recombination of immunoglobulin genes. There was little Aicda expression in LN B cells of B6 mice, in line with the absence of germinal centers in mice that are kept under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions. B cells in PP on the other hand are continuously stimulated by the commensal flora and expressed high levels of Aicda (Fig.4a). In absence of T cells in Tcra-deficient hosts, Aicda expression was very low (Fig.4a), as no germinal center B cells develop in the absence of T cell help. Transfer of eYFP+ TH17 cells, however, reconstituted Aicda expression to the level seen in B6 mice (Fig.4a).

Figure 4. Induction of B cell IgA by TH17 cells.

a) Quantitative PCR analysis for expression of Aicda in FACS purified B220+ cells from LN or PP of C57Bl/6 (B6), Tcra−/− or Tcra−/− mice transferred with eYFP+ TH17 cells (TH17 Tcra−/−). b) Flow cytometry of B220+ cells (left panel) and B220+ GL-7+ CD95+ cells (right panel) from PP of B6, Tcra−/− or Tcra−/− mice transferred with eYFP+ TH17 cells showing expression of germinal center markers CD95 and GL-7 (left) and IgA (right). c) Proportion of B220+ GL-7+ CD95+ and B220+ GL-7+ CD95+ IgA+ cells from B6, Tcra−/− and Tcra−/− mice transferred with eYFP+ TH17 cells. Mean values +/− SD for three individual mice are shown. Data in a, b and c are representative of three independent experiments. d) ELISA quantification of serum immunoglobulin isotypes from B6, Tcra−/− and Tcra−/− mice transferred with CD4+ CD44high eYFP− (CD44high Tcra−/−) or with eYFP+ TH17 cells (TH17 Tcra−/−). *, p-value < 0.01.

Furthermore, B cell expression of the germinal center markers GL-7 and CD95, as well as expression of IgA, which was detected on B cells from wild-type, but not Tcra-deficient mice, was induced in PP B cells of Tcra-deficient mice upon TH17 transfer (Fig.4b,c). As a result, the concentration of IgA, but not that of other Ig isotypes, was substantially increased in serum of Tcra-deficient mice that had received TH17 cells, whereas Tcra -deficient mice that had not received adoptively transferred TH17 cells, as well as those which had received non-TH17 effector cells (eYFP− CD44high) showed no change in their IgA expression (Fig. 4d). These data strongly suggest that intestinal TH17 cells deviating to a TFH profile in the PP may be responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses.

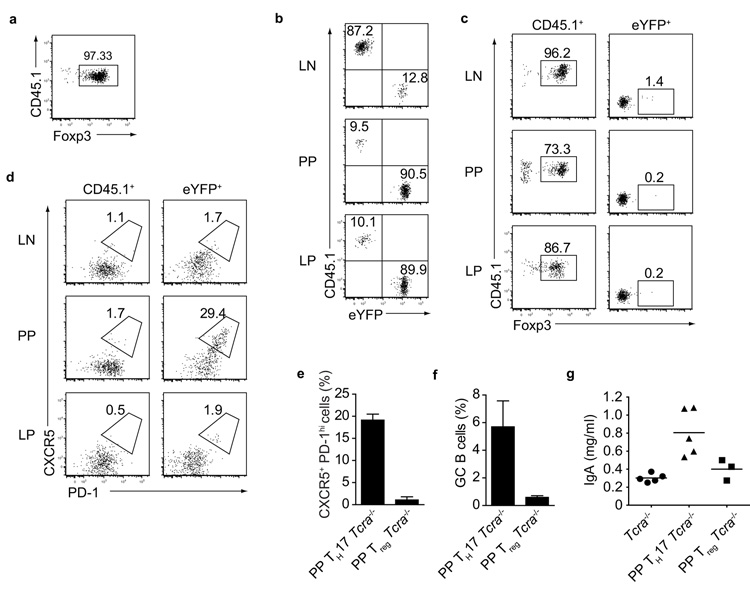

Ex-TH17 do not acquire Foxp3 and Treg do not induce IgA

Previous reports suggested that Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells might adopt a TFH phenotype in PP8, 18-20. Since these studies had focused on Treg isolated from lymphoid organs, we first compared the homing as well as the adoption of a TFH phenotype in Treg and TH17 cells isolated from LN and spleen. Treg from B6.CD45.1 mice were isolated on the basis of high CD25 expression, which correlated well with Foxp3 expression (Fig.5a), and co-transferred with equal numbers of eYFP+ TH17 cells into Tcra-deficient hosts. Three months later, transferred Treg were preferentially found in LN, whereas transferred eYFP+ cells homed to LP and PP of the small intestine (Fig.5b). CD45.1+ donor Treg retained their Foxp3 expression and there was no indication that donor eYFP+ TH17 cells acquired Foxp3 expression in any location within the adoptive host (Fig.5c). Furthermore, while 15-30% of TH17 cells deviated to a TFH profile in PP, Treg cells did not acquire a TFH profile in any of the tissues examined (Fig.5d). As the poor homing of LN derived Treg to intestinal tissues might have precluded acquisition of a TFH phenotype in PP, we isolated RFPhigh Treg from LP and PP of Foxp3RFP and transferred them into Tcra-deficient hosts. Although we observed efficient homing of donor RFPhigh Treg into PP, these cells did not acquire a TFH profile in the adoptive hosts (Fig.5e). Furthermore, adoptive Treg transfer did not induce germinal center B cells and IgA production (Fig.5f,g). Taken together these data strongly suggest that the promotion of IgA class switching in GC B cells in the PP is a function of ex-TH17 derived TFH cells, whereas Treg neither adopt a TFH profile nor support IgA production.

Figure 5. Co-transfer of eYFP+ TH17 with CD25high (Foxp3+) Treg cells.

a) Flow cytometry of FACS sorted CD45.1+ CD4+ CD25high T cells showing Foxp3 staining b) Flow cytometry of transferred CD45.1+ and eYFP+ cells in LN, PP, and LP of Tcra−/− mice three months after transfer. c) Flow cytometry of transferred CD45.1+ (left panel) and eYFP+ (right panel) cells in LN, PP, and LP of Tcra−/− mice three months after transfer showing Foxp3 staining. d) Flow cytometry of transferred CD45.1 (left panel) and eYFP+ (right panel) cells in LN, PP, and LP three months after transfer showing CXCR5 and PD-1 expression. Data in a, b, c and d are representative of three independent experiments. e) Proportion of CXCR5+ PD-1high cells and f) proportion of B220+ GL-7+ CD95+ (GC) B cells in PP of Tcra−/− mice three months after transfer with eYFP+ TH17 (PP TH17 Tcra−/−) or CD45.1+ CD4+ RFPhigh T cells (PP Treg Tcra−/−). Mean values +/− SD for three individual mice are shown. g) Serum IgA levels from Tcra−/−, PP TH17 Tcra−/− and PP Treg Tcra−/− mice 3 months after transfer.

IgA class switching in intact mice is dependent on TH17 cells

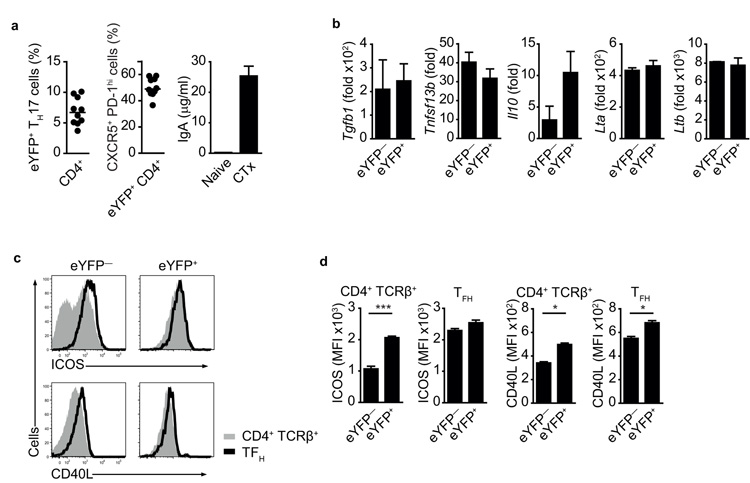

After transfer into Tcra-deficient host, transferred eYFP+ TH17 cells expanded substantially, resulting in IgA production that far exceeded that seen in wild-type mice in steady-state. In Tcra-deficient hosts, lymphopenia may have resulted in unimpeded expansion to the commensal flora by transferred TH17 cells. However, adoptive transfer into intact wild-type hosts, which contain full niches of intestinal TH17 and TFH cells, does not lead to efficient engraftment of the small number of donor cells that can be isolated for transfer from nonmanipulated mice. The minimal differences in serum IgA concentration between T cell-deficient Tcra−/− mice and non-immune wild-type mice (see Fig.4d) suggest that under steady-state conditions most IgA expression is T cell-independent. In order to investigate a T cell-dependent IgA immune response in intact mice we immunized Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice with cholera toxin and evaluated the proportion of total eYFP+ cells and eYFP+ TFH cells in the PP, as well as antigen-specific IgA responses in serum and feces. The proportion of eYPF+ cells (5-10%) among total CD4+ T cells in the PP of cholera toxin-immunized Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice was similar that observed in non-immunized Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice (Fig.6a). However, 40-60% of the eYPF+ cells in the PP had acquired a TFH phenotype, compared with 13% at steady-state (Fig.6a and Fig.2a). We also observed a strong cholera toxin specific IgA response in the serum of immunized Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice (Fig.6a).

Fig.6. Cholera toxin specific IgA response in Il17aCre R26ReYFP mice.

a) Proportion of eYFP+ cells in PP CD4+ T cells (left panel), proportion of CXCR5+ PD-1high cells in eYFP+ CD4+ T cells (middle panel) and ELISA quantification of cholera toxin-specific IgA (right panel) in cholera toxin-immunized Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice 7-10 days after challenge. b) Quantitative PCR analysis for expression of indicated mRNA in FACS purified eYFP+ and eYFP− CD4+ T cells from PP of cholera toxin-immunized Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice 10 days after challenge. mRNA expression is relative to Hprt. Data in a and b are representative of three independent experiments. c) Flow cytometry of eYFP+ or eYFP− CD4+ TCRβ+ T (shaded line) and TFH (solid line) cells from PP of cholera toxin-immunized Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice 10 days after challenge. d) MFI values of cell types as in c). Mean values +/− SEM are shown for three individual mice. *, p-value < 0.05; **, p-value < 0.005.

We used qPCR to assess markers associated with IgA switching in eYFP− and eYFP+ PP T cells from cholera toxin-immunized mice, but could not detect statistically significant differences in the two populations analyzed (Fig.6b). However, expression of ICOS and CD40L was consistently higher on eYFP+ cells than on eYFP− T cells, even before eYFP+ cells had acquired the CXCR5+ PD-1high TFH profile (Fig.6c,d).

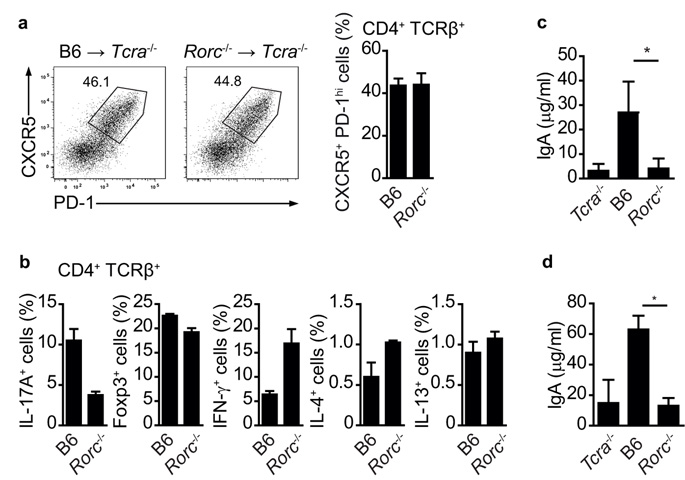

To address if T cell-dependent IgA induction requires TH17 cells in an otherwise intact mouse, we generated bone marrow chimeras in which Tcra−/− hosts were reconstituted with whole bone marrow from Rorc−/− mice21 (Rorc−/− Tcra−/− chimeras), which do not develop TH17 cells22. Although Rorc is required for the development of lymphoid architecture in the mucosal immune system21, 23-24, the mucosal environment of these chimeric mice is not disturbed, as Rorc-expressing innate lymphoid cell types are present in the Tcra−/− hosts. Control Tcra−/− chimeras were reconstituted with bone marrow from wild-type hosts. Flow cytometric analysis of PP showed similar proportions of TFH cells in Rorc−/− and control Tcra−/− chimeras (Fig.7a). Rorc−/− Tcra−/− chimeras had a reduction of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells compared to control Tcra−/− chimeras, whereas the proportion of Treg was comparable and IFNγ-, IL-4- and IL-13-producing CD4+ T cells were similar or even higher in Rorc−/− Tcra−/− chimeras compared to control Tcra−/− chimeras (Fig.7b). Serum isotype profiles in the two sets of chimeras prior to immunization were similar (Suppl.Fig.2). In order to test for T cell-dependent IgA production, we immunized Rorc−/− and control Tcra−/− chimeras with cholera toxin and analysed serum and fecal IgA amounts 10 days later. Control Tcra−/− chimeras mounted a strong cholera toxin-specific IgA response detectable in serum (Fig.7c) and faeces (Fig.7d). In contrast, Rorc−/− Tcra−/− chimeras had very low levels of cholera toxin-specific IgA, which were comparable to those observed in Tcra−/− mice (Fig.7c,d). Thus, these results show that TH17 cells are required for the germinal center switch to IgA production in PP.

Figure 7. Cholera toxin specific IgA response requires TH17 cells.

a) Flow cytometry of PP CD4+ T cells from Tcra−/− mice three months after reconstitution with C57Bl/6 (B6) or Rorc-deficient (Rorc−/−) bone marrow 10 days after cholera toxin challenge, showing expression of CXCR5 and PD-1. b) Proportion of PP CD4+ T cells expressing Foxp3 or producing indicated cytokines in Tcra−/− mice three months after reconstitution with C57Bl/6 or Rorc-deficient bone marrow 10 days after cholera toxin challenge. c, d) ELISA quantification of serum (c) and feces (d) cholera toxin-specific IgA in Tcra−/− and Tcra−/− mice three months after reconstitution with C57Bl/6 or Rorc-deficient bone marrow 10 days after cholera toxin challenge. Mean values +/− SEM for four individual mice are shown. *, p-value ≤ 0.01.

DISCUSSION

TH17 cells are known to diversify their effector profile in response to different environmental conditions25. Here we describe the consequences of TH17 cell plasticity towards a TFH program in the small intestine PP environment, a process that promoted T cell-dependent IgA responses. Although previous studies demonstrated that TH17 cells could be reprogrammed to obtain TFH characteristics in vitro26, an in vivo demonstration of this phenomenon would not have been possible without an IL-17 fate reporter mouse (Il17aCreR26ReYFP mouse), as this allows identification of a TH17 origin irrespective of the production of the signature cytokine IL-17. Here we used the fate reporter mouse to demonstrate the deviation of TH17 cells towards a TFH phenotype under the influence of the PP environment, which results in substantial phenotypic and functional changes.

Thus, IL-17 -as well as RORγt expression, was extinguished in ex-TH17 cell-derived TFH, whereas IL-21 and Bcl-6 were strongly upregulated. Although IL-21 has been associated with in vitro generated TH17 cells3, expression of this cytokine was not detectable in TH17 cells from the intestine or lymphoid organs of non-immune mice.

TH17 cells are naturally found in the small intestine of non-immune pathogen free mice. Under steady-state conditions they are thought to contribute to gut barrier function via the stimulation of tight junction formation and anti-microbial peptides27-28. Our analysis of the Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice indicated that the majority of the few TH17 cells found in peripheral lymphoid organs probably have their developmental origin in the gut, which is also supported by the fact that germfree Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice lack both intestinal and most of the TH17 cells from lymphoid organs. It was particularly interesting to observe that the cytokine IL-23, a key factor for the development of TH17 responses with pathogenic features11-12, 29, is dispensable for the maintenance of intestinal TH17 cells and their deviation towards a TFH program. This confirms earlier suggestions that TH17 cells might develop towards either protective or pathogenic functions30.

Our data expand the functional repertoire of intestinal TH17 cells to include the induction of the GC B cell IgA response. In Tcra-deficient mice transferred with eYFP+ TH17 cells serum IgA levels were highly increased irrespective of deliberate immunization. This was presumably due to the exaggerated expansion of the transferred cells in the lymphopenic hosts and recall responses to commensal microbiota that may be less well controlled in T cell-deficient hosts. In fact, immunization with cholera toxin did not result in an antigen-specific IgA response these mice (data not shown). In contrast, immunization of Il17aCreR26ReYFP mice with cholera toxin resulted in a pronounced cholera toxin specific IgA response and more pronounced switching of eYFP+ towards a TFH phenotype.

In Rorc−/− Tcra−/− chimeras, serum IgA levels prior to immunization with cholera toxin were comparable to those seen in Tcra−/− mice as well as wild-type B6 mice (data not shown), suggesting that basal IgA levels in SPF mice may be mostly T cell-independent. TH17 cells were shown to be involved in upregulating the expression of the polymeric Ig receptor that transports IgA across the intestinal epithelium31. However, it seems this role can be attributed to IL-17 rather than to TH17 cells. An interesting possibility that remains to be addressed is whether RORγt+ ILCs contribute to T cell-independent IgA induction and/or upregulation of the IgA transporter. Since ex-TH17 derived TFH switch off IL-17, it is unlikely that they participate in this process and we have not detected changes in expression of polymeric Ig receptor in our various models, none of which were devoid of IL-17. Nevertheless, IgA responses to challenge with cholera toxin strongly depended on the presence of TH17 cells.

Plasticity of TH17 cells towards a TFH fate was restricted to the PP environment and not evident in peripheral LN. As intestinal IgA fulfils important roles in maintaining equilibrium with the commensal flora and efficient mucosal host defence7, this novel TH17 function provides another example of their crucial role in mucosal immunity. It is interesting to note that segmented filamentous bacteria, which are important stimulators of TH17 cell development, also drive germinal center formation and IgA production in PP4-5. IgA deficiency causes aberrant expansion of SFB4, 32-33 and one might speculate that a deficiency in TH17 cells would result in the same features.

The developmental relationship between TFH cells and other CD4+ T cell subsets remains a matter of debate (reviewed in15). Our data are compatible with a non-exclusive CD4+ T cell program that obtains input from multiple T cell subsets. TH2 cells have been shown able to acquire CXCR5 expression, resulting in the induction or inhibition of B cell differentiation and class switching in GC18, 34-36. IL-12-mediated STAT4 activation transiently induces a TFH transcriptional profile, followed by repression of the TFH gene signature by the TH1-specific transcription factor T-bet37. Induction of Bcl-6 requires ICOS38, which is highly expressed on TH17 cells. Temporal and spatial regulation of CXCR5 and Bcl-6 expression in interaction with dendritic cells and B cells promote TFH development38-40, but it remains unclear whether the TFH state resembles a terminal effector status or whether such cells can be redirected towards other T cell programs. Thus, it remains to be determined whether the extinction of a previous effector profile is complete following the acquisition of a TFH phenotype or whether each effector T cell subset contributes a unique feature of its original signature to the functional helper response in the germinal center reaction. Elucidation of these possibilities would be facilitated by fate reporter mice for each T cells subset, which would allow analysis of functional profiles irrespective of the expression of signature cytokines that currently defines their subset allocation.

The role of Treg in PP germinal center reactions remains controversial. In some cases it was argued that Treg converted to TFH to promote intestinal IgA responses41,18, whereas other studies suggested that Treg, expressing markers of TFH cells are essential to control, rather than promote the germinal center reaction19-20. It should be noted that depletion of Treg via antibodies to CD25 as used in a previous study on the role of Treg in intestinal IgA induction41, would also have depleted TH17 cells, which are homogenously CD25+. Our data did not confirm plasticity of Treg towards a TFH profile, nor a role in promoting IgA responses either in the transfer model or in bone marrow chimeras. For transfers we isolated the Treg population based either on high CD25 expression, which was shown to mark stable Treg42 or based on high RFP-Foxp3 expression in the Foxp3RFP mouse43. The discrepancy regarding Treg plasticity might be explained by technical issues with the Foxp3 reporter model that was previously used18, where plasticity was particularly prominent in cells expressing lower levels of Foxp3 or in transfers of mixtures of Foxp3+ and Foxp3− cells. Given the reciprocal relationship between Foxp3 and RORγt in Treg and TH17 cell development44, it is conceivable that Foxp3low Treg cells may have deviated towards a TH17 fate, thus mimicking their unique function in the intestinal immune response.

Our data highlight another facet of the host protective function of TH17 cells in mucosal tissues. At present it remains unclear what particular features ex-TH17 cells contribute to their interaction with B cells to promote IgA responses. Currently known genes that affect IgA are widely expressed in the PP environment and we did not detect differential expression in eYFP+ and eYFP− PP T cells for these markers. Interestingly, eYFP+ T cells display substantially higher levels of ICOS and CD40L, which might facilitate preferential contact with B cells. B cells in the PP patch environment are characterized by expression of the transcription factor RORα45 and compete for T cell help before entry into germinal centres. eYFP+ T cells may have preferential access. This, however, does not explain why TFH in PP of the Rorc−/− Tcra−/− chimeras, which do not face competition by ex-TH17 cells are still not competent to induce an IgA switch.

Given the prominent role of TH17 cells in autoimmunity, these cells seem as obvious targets for therapeutic intervention. However, understanding their role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity is required in order to avoid disturbance of these beneficial functions.

Online METHODS

Mice

IL-17 fate reporter (Il17aCreR26ReYFP) mice12 and Foxp3RFP mice with a bicistronic red fluorescent protein (RFP) reporter knocked into the Foxp3 locus43, as well as TCRα-deficient on a B6 background46 and p19−/− (Il23a−/−) mice (obtained from Dan Cua,Merck Research laboratories USA) were bred in the NIMR animal facility under specified pathogen free conditions. All animal experiments were done according to the NIMR Ethical Review committee and Home Office regulations. Some IL-17 fate reporter mice were raised in germ free (GF) conditions using caesarean section rederivation, as described at The European Mouse Mutant Archive http://www.emmanet.org/protocols/GermFree_0902.pdf. Briefly, day 20 post coitum uteri from donor females were transferred through a reservoir containing 1% VirkonS to the isolator housing the germ-free surrogate mothers. The microbiological status of the isolator was monitored every 3 weeks. Bones from Rorc(γt)GFP/GFP mice which are knockout for Rorc (γt)21 were obtained from Oliver Steinmetz (Hamburg).

Antibodies

anti-CCR6 (140708), CXCR5 (2G8), CD95 (Jo2), and anti-IgA (C10-3) were purchased from BD Biosciences. Anti-GL-7 (GL7) and RORγt (AFKJS-9) were obtained from eBioscience. Anti-CD4 (GK1.5), CD25(PC61), CD27 (LG.3A10), CD44 (IM7), CD45.1 (A20), CD103 (2E7), ICOS (C398.4A), IL-7Ra (A7R34), Podoplanin (8.1.1), PD-1 (29F.1A12), B220 (RA3-6B2), IL-17 (TC11-18H10.1) , IL-22 (AM22.3), IFNγ (XMG1.2), and TCR-β (H57-597) were from Biolegend.

Preparation of lymphocytes in tissues

Briefly, lymphocytes in the lamina propria were prepared by cutting the small intestine into 1cm pieces after removing Peyer’s patches, shaking for 20min at 37°C in 10ml IEL buffer (PBS supplemented with 10% FCS, 1mM pyruvate, 20μM HEPES, 10mM EDTA and penicillin /streptomycin mix, 10ug/ml Polymyxin B) to remove epithelial and intraepithelial cells and then digesting the remaining tissue using 1mg/ml collagenase D (Roche) and 10U/ml DNase1 (Sigma) at 37°C for 1 hr followed by 36.5% Percoll separation.

Real time PCR

RNA was extracted from FACS sorted CD4 T cells using Trizol and reverse transcribed with Omniscript (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA served as template for the amplification of genes of interest and the housekeeping gene (Hprt) by real-time PCR, using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA); Hprt1 (Mm00446968_m1), Aicda (Mm00507774_m1), Bcl6 (Mm00477633_m1), Il17a (Mm00439619_m1), Il21 (Mm00517640_m1), Il22 (Mm00444241_m1), Prdm1 (Mm00476128_m1), Rorc (Mm01261019_g1), universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) and the ABI-PRISM 7900 Sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Target gene expression was calculated using the comparative method for relative quantification upon normalisation to Hprt gene expression.

Cholera toxin immunisation

TCRα−/− mice were sublethally irradiated (500 rad) and reconstituted with B6 or Rorc−/− bone morrow. Before immunization with cholera toxin mice were deprived of food for 2 h and then given 0.25 ml of a solution containing eight parts HBSS and two parts 7.5% sodium bicarbonate by oral gavage (o.g.) to neutralize stomach acidity. After 30 min, mice were o.g. immunized with 25μg cholera toxin (List Biological Laboratories, USA). Concentrations of antibodies specific for cholera toxin were determined by ELISA with cholera toxin (List Biological Laboratories) as the capture agent.

Statistics were performed using a two-tailed Student T test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council UK (Ref. U117512792). JET was supported by a Research Fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (TU 316/1-1) and MV is a recipient of a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds PhD fellowship. We would like to thank the flow facility for expert cell sorting and Biological Services for breeding and maintenance of our mouse strains. Axenization was supported by EMMA, EU FP7 Capacities Specific Program. We would also like to thank Drs A and T Zal (MD Anderson, Houston) for advice with PP microscopy, Drs D Cua (Merck Research Laboratories, USA) for the Il23a−/− strain and Adrian Hayday (King’s College London) for Tcra−/− mice.

Footnotes

Contributions K.H. and B.S. conceived of the project and designed the experiments. K.H. did most of the experiments. M.V., J-E.T., and J.H.D. did specific experiments. J.D. established the germfree colony of reporter mice and O.M.S. supplied bone marrow from Rorc−/− mice, respectively. K.H. and B.S. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Shulzhenko N, et al. Crosstalk between B lymphocytes, microbiota and the intestinal epithelium governs immunity versus metabolism in the gut. Nat Med. 2011;17:1585–1593. doi: 10.1038/nm.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castigli E, et al. TACI is mutant in common variable immunodeficiency and IgA deficiency. Nat Genet. 2005;37:829–834. doi: 10.1038/ng1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ivanov II, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talham GL, Jiang HQ, Bos NA, Cebra JJ. Segmented filamentous bacteria are potent stimuli of a physiologically normal state of the murine gut mucosal immune system. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1992-2000.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagarasan S, Kawamoto S, Kanagawa O, Suzuki K. Adaptive immune regulation in the gut: T cell-dependent and T cell-independent IgA synthesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:243–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macpherson AJ, McCoy KD, Johansen FE, Brandtzaeg P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:11–22. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritz JH, et al. Acquisition of a multifunctional IgA+ plasma cell phenotype in the gut. Nature. 2012;481:199–203. doi: 10.1038/nature10698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tezuka H, et al. Regulation of IgA production by naturally occurring TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells. Nature. 2007;448:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature06033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergqvist P, Stensson A, Lycke NY, Bemark M. T cell-independent IgA class switch recombination is restricted to the GALT and occurs prior to manifest germinal center formation. J Immunol. 2010;184:3545–3553. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGeachy MJ, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314–324. doi: 10.1038/ni.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirota K, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esplugues E, et al. Control of TH17 cells occurs in the small intestine. Nature. 2011;475:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinuesa CG, Cyster JG. How T cells earn the follicular rite of passage. Immunity. 2011;35:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamoto S, et al. The inhibitory receptor PD-1 regulates IgA selection and bacterial composition in the gut. Science. 2012;336:485–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1217718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters A, et al. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuji M, et al. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer’s patches. Science. 2009;323:1488–1492. doi: 10.1126/science.1169152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linterman MA, et al. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med. 2011;17:975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung Y, et al. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat Med. 2011;17:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eberl G, et al. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nature immunology. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanov II, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Z, et al. Requirement for RORgamma in thymocyte survival and lymphoid organ development. Science. 2000;288:2369–2373. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurebayashi S, et al. Retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma (RORgamma) is essential for lymphoid organogenesis and controls apoptosis during thymopoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:10132–10137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee YK, Mukasa R, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Developmental plasticity of Th17 and Treg cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu KT, et al. Functional and epigenetic studies reveal multistep differentiation and plasticity of in vitro-generated and in vivo-derived follicular T helper cells. Immunity. 2011;35:622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinugasa T, Sakaguchi T, Gu X, Reinecker HC. Claudins regulate the intestinal barrier in response to immune mediators. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishigame H, et al. Differential roles of interleukin-17A and −17F in host defense against mucoepithelial bacterial infection and allergic responses. Immunity. 2009;30:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Codarri L, et al. RORgammat drives production of the cytokine GM-CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nature immunology. 2011;12:560–567. doi: 10.1038/ni.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor W, Jr., Zenewicz LA, Flavell RA. The dual nature of T(H)17 cells: shifting the focus to function. Nature immunology. 2010;11:471–476. doi: 10.1038/ni.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao AT, Yao S, Gong B, Elson CO, Cong Y. Th17 cells upregulate polymeric Ig receptor and intestinal IgA and contribute to intestinal homeostasis. J Immunol. 2012;189:4666–4673. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki K, et al. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1981–1986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307317101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King IL, Mohrs M. IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells in reactive lymph nodes during helminth infection are T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1001–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinhardt RL, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaretsky AG, et al. T follicular helper cells differentiate from Th2 cells in response to helminth antigens. J Exp Med. 2009;206:991–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakayamada S, et al. Early Th1 cell differentiation is marked by a Tfh cell-like transition. Immunity. 2011;35:919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi YS, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 2011;34:932–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerfoot SM, et al. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity. 2011;34:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitano M, et al. Bcl6 protein expression shapes pre-germinal center B cell dynamics and follicular helper T cell heterogeneity. Immunity. 2011;34:961–972. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:19256–19261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komatsu N, et al. Heterogeneity of natural Foxp3+ T cells: a committed regulatory T-cell lineage and an uncommitted minor population retaining plasticity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:1903–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811556106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Identifying Foxp3-expressing suppressor T cells with a bicistronic reporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:5126–5131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501701102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou L, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang NS, et al. Divergent transcriptional programming of class-specific B cell memory by T-bet and RORalpha. Nature immunology. 2012;13:604–611. doi: 10.1038/ni.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Philpott KL, et al. Lymphoid development in mice congenitally lacking T cell receptor alpha beta-expressing cells. Science. 1992;256:1448–1452. doi: 10.1126/science.1604321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.