Abstract

Noninvasive brain stimulation provides a potential tool for affecting brain functions in the typical and atypical brain and offers in several cases an alternative to pharmaceutical intervention. Some studies have suggested that transcranial electrical stimulation (TES), a form of noninvasive brain stimulation, can also be used to enhance cognitive performance. Critically, research so far has primarily focused on optimizing protocols for effective stimulation, or assessing potential physical side effects of TES while neglecting the possibility of cognitive side effects. We assessed this possibility by targeting the high-level cognitive abilities of learning and automaticity in the mathematical domain. Notably, learning and automaticity represent critical abilities for potential cognitive enhancement in typical and atypical populations. Over 6 d, healthy human adults underwent cognitive training on a new numerical notation while receiving TES to the posterior parietal cortex or the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Stimulation to the the posterior parietal cortex facilitated numerical learning, whereas automaticity for the learned material was impaired. In contrast, stimulation to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex impaired the learning process, whereas automaticity for the learned material was enhanced. The observed double dissociation indicates that cognitive enhancement through TES can occur at the expense of other cognitive functions. These findings have important implications for the future use of enhancement technologies for neurointervention and performance improvement in healthy populations.

Introduction

Finding novel ways to apply our expanding understanding of the brain to the enhancement of brain functions and human abilities is of perennial interest to the medical and neuroscience communities (Hyman, 2011; Cohen Kadosh et al., 2012). In recent years, a new wave of research has started to explore whether noninvasive brain stimulation (NIBS), and in particular transcranial electrical stimulation (TES), might be beneficial for cognitive enhancement for restorative purposes (Flöel et al., 2011; Holland and Crinion, 2011; Brunoni et al., 2012), as well as for taking individuals beyond their norms (Cohen Kadosh et al., 2010; Kuo and Nitsche, 2012). Promisingly, a recent meta-analysis shows that enhancement effects in the treated cognitive domain are regularly obtained after TES (Jacobson et al., 2012). Critically, studies so far have primarily focused on issues, such as safety and physical side effects (Poreisz et al., 2007), while neglecting the potential influence of TES on untreated cognitive abilities. The present study represents the first attempt to uncover the potential cost of cognitive enhancement after TES. Toward this end, we applied a learning model to simulate the cognitive process through which people acquire new information in the domain of numerical learning and mathematical cognition. Using a cross-sectional design, we asked young adults to learn the magnitude of new arbitrary symbols (Cohen Kadosh et al., 2010; Tzelgov et al., 2000) (see Fig. 1) while they received TES to either the posterior parietal cortex (PPC), a key brain area for numerical understanding (Butterworth et al., 2011), or the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), an area widely implicated in learning (Pasupathy and Miller, 2005). A control (sham) group received stimulation for 30 s, which leads to indistinguishable sensations from those produced by real stimulation (Gandiga et al., 2006).

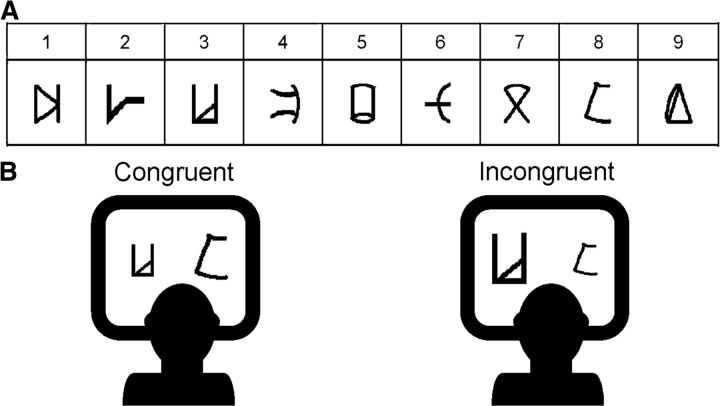

Figure 1.

Example of stimuli and the numerical Stroop task. A, Everyday digits and their corresponding artificial digits that were used to create the new numerical system. Each everyday digit appears above its corresponding artificial digit. Over 6 d of training, participants were instructed to refer to the artificial digits as representing various magnitudes and to decide on each learning trial which one of the two stimuli has a larger magnitude, while receiving visual feedback for their decision. Only adjacent pairs have been presented during this phase. B, An example for congruent and incongruent trials with artificial digits from the numerical Stroop task. In the current example, the symbols corresponding to the Arabic digits 3 and 8 appear on the left and right sides of a congruent and an incongruent trial, respectively. Participants were asked to compare the stimuli according to their physical size while ignoring their numerical meaning. On congruent trials, the larger number appeared in larger font, whereas on incongruent trials the larger number appeared in smaller font. The numerical Stroop effect (incongruent vs congruent) indicates the slowing in the decision time when numbers are irrelevant to the task and are therefore processed automatically (Henik and Tzelgov, 1982). Nonadjacent pairs have been presented in this task to examine transitive inference from the learned material (Tzelgov et al., 2000).

This approach allowed us to examine the following: (1) whether the acquisition of numerical understanding, a fundamental learning process that serves as a building block for mathematical abilities (Menon, 2010; Butterworth et al., 2011), could be enhanced by TES; and (2) whether there is a mental cost for such enhancement. Furthermore, our design allowed us to specifically assess the effects of TES to the aforementioned brain structures (PPC and DLPFC) on two essential abilities of human expertise: (1) skill acquisition, the ability to perform a task with increased facility (Logan, 1988); and (2) automaticity, the quick and effortless performance of a task, with minimal cognitive effort or conscious intention (LaBerge and Samuels, 1974; Tzelgov et al., 2000).

Both learning and automaticity are crucial skills in everyday life, particularly in domains of cognitive achievement, such as reading and mathematics (LaBerge and Samuels, 1974; Butterworth, 1999; Tzelgov et al., 2000). Thus, these abilities represent the ideal grounds for assessing potential benefits and risks of cognitive enhancement after TES.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Nineteen participants (10 males) were randomly assigned to the PPC group, Sham group, and the DLPFC group. The participants' age range was 20–31 years, with no significant differences between the groups in age or gender (all p > 0.2). None of the participants reported a history of psychiatric or neurological problems, including learning disabilities.

Procedure

The study consisted of six sessions. The sessions lasted ∼120 min each and were distributed over a week. The experiments took place between 9 A.M. and 6 P.M. for all participants.

Tasks: learning

Participants were instructed to refer to meaningless symbols (i.e., the artificial digits) as though they represented various magnitudes (Fig. 1A). On each trial, two symbols, one in each visual field, appeared on a computer monitor for 500 ms. Participants chose the side of the display with the symbol they thought had a larger magnitude by pressing the keys P or Q on a keyboard. They were asked to respond as quickly as possible but to avoid mistakes. Each trial began with a fixation point (in white ink) for 300 ms at the center of a black computer monitor, followed by a blank screen for 300 ms. Subsequently, two symbols (vertical visual angle of 2.63°) appeared on the computer monitor: one symbol in the left visual field and another in the right visual field. The center-to-center distance between the two digits subtended a horizontal visual angle of 9.7°. The stimulus pair remained on the monitor until the participant pressed a key (but not for >5 s). After each response, feedback was presented (“Correct Answer”/”Mistake”/”No Response”). A new trial began 200 ms after the feedback. Each learning session was divided into 11 blocks of trials, each block consisting of 144 symbol pair comparisons (trials) that included 18 comparisons for each adjacent pair. The presentation in each block appeared in a random order. A training block with 48 trials was performed at the beginning of the task. Participants were instructed to select the symbol they thought had a larger magnitude in each pair. The correct answer appeared an equal number of times on the right and left sides, and all pairs appeared equally often. Participants were provided with the average reaction time of the correct answers and the percentage of errors after one-third, two-thirds, and at end of each block.

The learning task was the first task to be administered in all six sessions. To examine skill acquisition, we fitted each participant's performance using the following power law function (Newell and Rosenbloom, 1981): RT = B*(N)−C, where RT represents the mean reaction time in a given block, B is the performance in time on the first block (N = 1), N the number of the block, and C is the slope of the line (i.e., the learning rate).

Numerical Stroop tasks

Artificial digits.

In the first numerical Stroop task, artificial digits appeared on the screen in the same manner as in the learning task, but the symbols differed in physical size (Fig. 1B). The vertical visual angles of the symbols were 2.2° or 2.75°. Although all of the possible adjacent pairs were used in the learning phase, here only nonadjacent pairs were used and congruent, incongruent, and neutral conditions were included to examine the development of numerical representations (Tzelgov et al., 2000). In a congruent pair, the numerically larger digit was also physically larger. In a neutral pair, the digits differed only in the relevant dimension. In an incongruent pair, the numerically larger digit was physically smaller. The three conditions appeared the same number of times, with the correct answer appearing equally often on the right and left sides of the monitor and all pairs appearing equally often. No feedback was given on participants' performance. Participants were instructed to choose the physically larger symbol by pressing either the P or Q button and to try and respond as quickly and as accurately as possible.

Everyday digits.

The same numerical Stroop task was also administered to all participants using everyday digits. This allowed us to examine whether performance modulation was specific to the learned material (i.e., artificial digits) and not related to more general abilities, such as cognitive control.

TES protocol

We chose to use transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS), the most frequently used application of TES. This technique delivers low electric current to the scalp to modulate the resting membrane potentials of underlying neurons by hyperpolarizing them (cathodal stimulation) or partially depolarizing them (anodal stimulation). TDCS induces neurochemical changes that are involved in learning, memory, and cortical plasticity (Fritsch et al., 2010; Stagg et al., 2011).

Direct current of 1 mA was generated using a NeuroConn Eldith DC-Stimulator Plus and delivered via a pair of identical, square scalp electrodes (3 cm2) covered with conductive rubber and saline-soaked synthetic sponges for 20 min everyday as training started. The location of the electrodes was based on the International 10–20 system for EEG electrode placement: P3-P4 for the PPC group and F3-F4 for the DLPFC group. The PPC group received cathodal and anodal stimulation for 20 min to the right PPC and the left PPC, respectively. The DLPFC group received the same stimulation but to the left and right DLPFC. Finally, the sham group received stimulation to the PPC or the DLPFC for 30 s. The latter stimulation produces a tingling sensation that is indistinguishable from nonsham stimulation conditions (Gandiga et al., 2006) but has no modulatory effect on the neuronal populations (Fritsch et al., 2010).

Although stimulation ended during the learning task, electrodes were kept in place until task completion to avoid participant bias. The same setup was applied for all groups, and participants were unaware of the type of stimulation. All participants reported a slight tingling sensation at the onset of the stimulation, which diminished rapidly because of habituation. No other discomforts or adverse effects were reported.

Results

Learning task

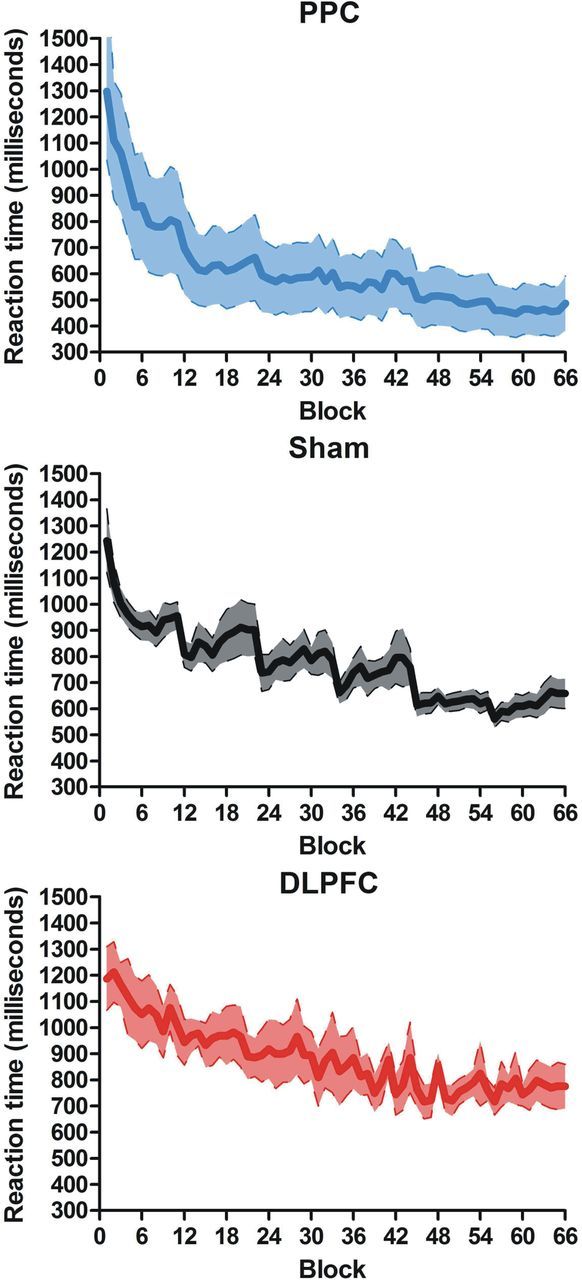

This analysis showed that TDCS affected the speed of skill acquisition as indicated by the overall learning rate (main effect of TDCS group, F(2,16) = 5.3, p < 0.02, η2partial = 0.4; Figure 2). The PPC group exhibited the highest learning rate, whereas the DLPFC group exhibited the lowest learning rate: a linear trend analysis (PPC > sham > DLPFC, F(1,16) = 9.73, p < 0.006) explained 92% of the variance. Notably, performance differences between groups were not evident at the beginning of the training (main effect of group, F(2,16) = 1.71, p > 0.21, η2partial = 0.17; Figure 2). This allowed us to exclude any motivational or attentional factors as the source of the reported effects.

Figure 2.

Learning functions for the three groups. Top, PPC group. Middle, Sham group. Bottom, DLPFC group. The slope for the PPC group (top) is steeper than the other two (middle, bottom), indicating faster learning. Analysis of the learning rate gave statistical support to this result by showing a significant difference between the learning rate for each group that was best explained by a linear trend: PPC > sham > DLPFC (p < 0.006); 92% of the variance explained.

Numerical Stroop tasks

In the numerical Stroop task with artificial digits, the numerical Stroop effect at the end of the training interacted with TDCS group (F(4,32) = 2.75, p < 0.04, η2partial = 0.26; Table 1). In contrast to the pattern observed during learning, the DLPFC group showed the best performance by exhibiting the greatest automaticity as indicated by a larger numerical Stroop effect (RTincongruent − RTcongruent), whereas the PPC group showed the smallest degree of automaticity: a linear trend analysis explained 67% of the variance (F(1,16) = 4.8, p < 0.04). Although one might suggest that the smaller numerical Stroop effect could indicate better performance, an additional inspection of the results revealed that this was not the case. Namely, in the case of the PPC group, a Stroop-like effect in a perceptual, but not in a semantic, sense was observed. Specifically, in the PPC group, the numerical Stroop effect with artificial digits was characterized by a faster neutral condition, compared with incongruent and congruent conditions. It is worth noting that the same pattern has been observed for novice users of numbers, such as children at the beginning of schooling (6.5 years old) when asked to perform the same task with everyday digits as stimuli. This result is likely to reflect a perceptual effect, such that stimuli that have higher perceptual variance (i.e., incongruent and congruent stimuli) are processed slower than stimuli that are more alike in the irrelevant dimension (i.e., neutral condition) (Girelli et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Reaction time in the numerical Stroop task with artificial digits and everyday digits, as a function of TDCS group for congruent, neutral, and incongruent conditions

| TDCS group | Congruity | Artificial digits (ms) |

Everyday digits (ms) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | ||

| PPC | Congruent | 462 | 45 | 383 | 17 |

| Neutral | 429 | 41 | 400 | 15 | |

| Incongruent | 470 | 56 | 436 | 23 | |

| Sham | Congruent | 456 | 39 | 393 | 15 |

| Neutral | 457 | 35 | 400 | 13 | |

| Incongruent | 474 | 48 | 428 | 20 | |

| DLPFC | Congruent | 476 | 49 | 406 | 19 |

| Neutral | 484 | 45 | 414 | 17 | |

| Incongruent | 568 | 61 | 444 | 25 | |

SEM refers to the standard error of the mean.

Performance with everyday digits was not modulated by group (F(4,32) = 0.44, p = 0.77; Table 1), thus supporting the idea that TDCS affected automaticity of the learned material specifically. Moreover, the lack of a differential numerical Stroop effect with everyday digits indicates that the groups did not differ in their general mental abilities, such as cognitive control.

Furthermore, when we subjected these data to a three-way ANOVA with the factors TDCS group (PPC, sham, DLPFC), stimulus material (everyday digits, learned artificial digits), and congruity (congruent, neutral, incongruent), the three-way interaction was significant (F(4,32) = 3.04, p < 0.03, η2partial = 0.27), and was the result of a main effect of congruity regardless of TDCS group for everyday digits, whereas the TDCS group interacted with the congruity factor for the learned artificial digits only. This result confirms our previous analyses and indicates that performance modulation (i.e., impairment or enhancement) elicited by TDCS was specific to the learned material (i.e., artificial digits) and did not affect the nonlearned material (i.e., everyday digits).

Learning and automaticity

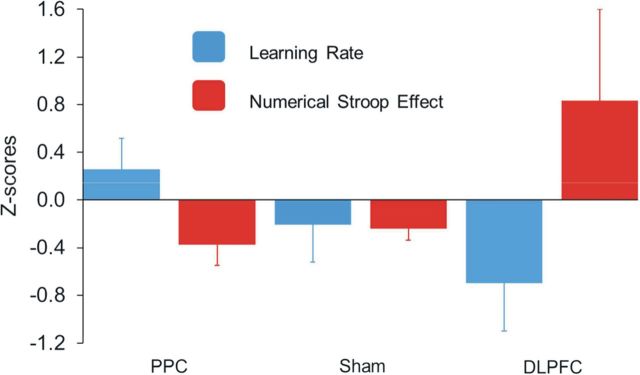

To directly compare learning and automaticity effects, we transformed the data into Z-scores and conducted an ANOVA with the factors TDCS group (PPC, DLPFC, sham) and performance (learning rate, numerical Stroop effect). The significant interaction between TDCS group and performance confirmed a double dissociation (F(2,16) = 5.2, p < 0.02, η2partial = 0.38; Figure 3). Namely, the DLPFC group exhibited a poor learning rate but greater automaticity for the artificial digits, whereas the PPC showed the opposite effect. Moreover, a linear trend analysis: group (PPC < sham < DLPFC) and task (learning rate ≠ numerical Stroop effect) explained 99% of the variance (p < 0.006).

Figure 3.

Double dissociation between learning rate and automaticity as a function of brain stimulation. Although the speed of learning has been the fastest for PPC stimulation and slowest for the DLPFC stimulation, the automatic processing of the learned material showed exactly the opposite pattern. A linear trend analysis (group [PPC < sham < DLPFC], and task [learning rate ≠ numerical Stroop effect, RTincongruent − RTcongruent]) explained 99% of the variance (p < 0.006). Data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

The possibility of enhancing skill acquisition and automaticity in a given cognitive domain (i.e., mathematics) can have significant benefits to an individual and their functioning. For instance, during the process of gaining numerical understanding (e.g., understanding the meaning of the number 2), the learner progresses through a series of hierarchical stages that rely on key cognitive components, including skills learning and automaticity. This process begins with learning to identify the digit 2, first perceptually and subsequently semantically, and it ultimately leads to a stage where the digit's sematic meaning is processed fluently and unintentionally (i.e., automatically) (Tzelgov et al., 2000). These steps are crucial for an intact numerical understanding and constitute the building blocks of many aspects of mathematics (Menon, 2010; Butterworth et al., 2011). Moreover, its malfunction, as indicated by lower automaticity, is associated with mathematical learning disabilities (Rubinsten and Henik, 2009).

In the present study, we developed a new numerical system and asked healthy university students to learn the magnitude of arbitrary symbols without knowing the quantity that had been assigned to them (Tzelgov et al., 2000; Cohen Kadosh et al., 2010). This approach simulates the cognitive mechanisms associated with skills acquisition in the early school years. For 6 d, at the beginning of each learning day, a weak current (1 mA) was applied to the participants' heads. Upon the completion of the learning phase, we administered the numerical Stroop task (Henik and Tzelgov, 1982) to assess the automaticity of the newly learned digits (Tzelgov et al., 2000; Cohen Kadosh et al., 2010). We examined acquisition and automaticity of the new numerical system as a function of three TDCS groups.

Our results show that TES to different brain areas applied during symbolic learning can lead to differential effects, which involve simultaneous cognitive enhancement and cognitive impairment, compared with sham stimulation. Namely, stimulation of the DLPFC led to impaired learning, as indicated by the effect on the overall learning rate but greater automaticity for the learned material. The results after TES to the PPC were exactly the reverse; while the learning rate was the highest, indicating fast learning, the automatic processing of the learned material showed impairment. These effects were specific to the learned material and did not occur for the nonlearned material, as indicated by intact performance with everyday digits in all groups. To the best of our knowledge, this double dissociation (Fig. 3) is the first to be reported in the field of NIBS. Most of the studies to date primarily used a single task and assessed the modulation of task performance as a function of stimulation to a target brain area, sham stimulation, and in some cases control regions. However, the current study suggests that the inclusion of additional tasks, and additional targeted brain areas, might be vital to unravel the potential cost(s) and therefore potential limitations of NIBS on human cognition. We would like to stress that this might not be a generalized pattern. Namely, it might not be the case for every type of NIBS—transcranial random noise stimulation (Terney et al., 2008) might affect brain function via different mechanisms than TDCS—or for every type of cognitive training. Moreover, it is important to note that the cognitive cost might depend on other factors, such as the stimulated brain region, and/or the duration and intensity of the stimulation. However, based on the current results, it is important that future NIBS studies not only focus on the issue of potential cognitive enhancement as has done so far. Rather, researchers should concentrate on devising the optimal stimulation parameters that will allow consistent cognitive enhancement, with or without a tolerable mental cost. Moreover, from a theoretical point of view, it will be important to explore the brain mechanisms associated with cognitive enhancement and its concurrent cognitive cost. Particularly, it would be informative to investigate the neurobiological factors that might lead to these corticocortical interactions, such as balance shifting in cerebral hemodynamic response, or modulation in neuronal metabolism, just to name a few (Fritsch et al., 2010).

The present work has also important implications for theories in the cognitive sciences. As currently formulated, the cognitive models that aim to explain the relationship between skill acquisition and automaticity cannot fully account for the present findings. For example, the instance theory proposed by Logan (1988) cannot explain the observed results on automaticity as the material presented during the learning phase was not the same as the one presented in the test phase (i.e., during the test phase stimuli consisted of nonadjacent pairs that were never presented during the learning processes, which was based on adjacent pairs only). Thereby, symbol pairs could not have been strictly memorized to solve the task. In opposition, the self-organizing consciousness theory of Perruchet and Vinter (2002) could potentially explain our results on automaticity, but it is not sufficient to account for the double dissociation between speed of learning and automaticity. According to the self-organizing consciousness theory, automaticity is gained by transitive inference. For example, when participants have to learn, for example, that A7 is smaller than A8 (e.g., A indicates the artificial digit linked to the number 7, and so on) just after having learned that A7 is larger than A6, it is quite possible that participants use a strategy that consists of forming a conscious representation of the linear order A6 < A7 < A8. Generalizing this strategy to a longer list of items could provide a unified representation of the series of the artificial figures, even if they have not been trained on nonadjacent pairs. The current results suggest that better learning might be associated with improved item-based retrieval as indicated by Logan's theory (Logan, 1988). However, such learning might have a cost when it comes to the ability to use transitive inference as suggested by the self-organizing consciousness theory (Perruchet and Vinter, 2002).

With respect to numerical cognition, the current study indicates that improved symbolic numerical learning might not necessarily relate to more proficient numerical processing. This is in contrast with current models of mathematical learning disabilities that attribute impaired numerical processing (i.e., as measured by Stroop-like paradigms) to difficulties in the acquisition of symbolic numerical understanding (e.g., von Aster and Shalev, 2007). Instead, the current results might be better explained by theories that attribute the observed deficits in mathematical learning disabilities to a disconnection between number semantics and their respective symbols (Rousselle and Noel, 2007; Iuculano et al., 2008).

In conclusion, the current results clearly demonstrate that enhancement of a specific cognitive ability can happen at the expense of another ability. This mental cost might be the result of a shift of metabolic consumption and neurochemical modulation caused by TES (Fritsch et al., 2010), which changes the respective involvement of different brain areas. The field of cognitive enhancement using TES is still in its infancy, especially compared with other fields (Hyman, 2011), and further research is needed to properly address the merits and generalizability of this technique. Progress in the understanding of the relationship between enhancement and its potential mental costs, and a better knowledge of how to avoid the latter, might open exciting possibilities for cognitive enhancement in typical and atypical populations in the future.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (WT88378). We thank K. Cohen Kadosh, A. Coway, C.-H. Juan, R. Kanai, S. Soskic, D.B. Terhune, J. Tzelgov, and V. Walsh for their contributions at different stages of the project.

R.C.K. has filed a patent entitled “Apparatus for Improving and/or Maintaining Numerical Ability” (International Application PCT/GB2011/050211). The current results, however, are highly unlikely to lead to any financial gain, as they reveal a potential problem of using the apparatus (noninvasive brain stimulation) for numerical enhancement. T.I. declares no competing financial interests.

References

- Brunoni AR, Nitsche MA, Bolognini N, Bikson M, Wagner T, Merabet L, Edwards DJ, Valero-Cabre A, Rotenberg A, Pascual-Leone A, Ferrucci R, Priori A, Boggio PS, Fregni F. Clinical research with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): challenges and future directions. Brain Stim. 2012;5:175–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth B. The mathematical brain. London: Macmillan; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth B, Varma S, Laurillard D. Dyscalculia: from brain to education. Science. 2011;332:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.1201536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Kadosh R, Soskic S, Iuculano T, Kanai R, Walsh V. Modulating neuronal activity produces specific and long lasting changes in numerical competence. Curr Biol. 2010;20:2016–2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Kadosh R, Levy N, O'Shea J, Shea N, Savulescu J. The neuroethics of noninvasive brain stimulation. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R108–R111. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flöel A, Meinzer M, Kirstein R, Nijhof S, Deppe M, Knecht S, Breitenstein C. Short-term anomia training and electrical brain stimulation. Stroke. 2011;42:2065–2067. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.609032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch B, Reis J, Martinowich K, Schambra HM, Ji Y, Cohen LG, Lu B. Direct current stimulation promotes BDNF-dependent synaptic plasticity: potential implications for motor learning. Neuron. 2010;66:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandiga PC, Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Transcranial DC stimulation (tDCS): a tool for double-blind sham-controlled clinical studies in brain stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:845–850. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girelli L, Lucangeli D, Butterworth B. The development of automaticity in accessing number magnitude. J Exp Child Psychol. 2000;76:104–122. doi: 10.1006/jecp.2000.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henik A, Tzelgov J. Is three greater than five: the relation between physical and semantic size in comparison tasks. Mem Cogn. 1982;10:389–395. doi: 10.3758/bf03202431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland R, Crinion J. Can tDCS enhance treatment of aphasia after stroke? Aphasiology. 2012;26:1169–1191. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2011.616925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE. Cognitive enhancement: promises and perils. Neuron. 2011;69:595–598. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuculano T, Tang J, Hall CW, Butterworth B. Core information processing deficits in developmental dyscalculia and low numeracy. Dev Sci. 2008;11:669–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L, Koslowsky M, Lavidor M. tDCS polarity effects in motor and cognitive domains: a meta-analytical review. Exp Brain Res. 2012;216:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2891-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. Effects of transcranial electrical stimulation on cognition. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2012;43:192–199. doi: 10.1177/1550059412444975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBerge D, Samuels SJ. Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cogn Psychol. 1974;6:293–323. [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD. Toward an instance theory of automatization. Psychol Rev. 1988;95:492–527. [Google Scholar]

- Menon V. Developmental cognitive neuroscience of arithmetic: implications for learning and education. ZDM. 2010;42:515–525. doi: 10.1007/s11858-010-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell A, Rosenbloom P. Mechanisms of skill acqusition and the law of practice. In: Anderson JR, editor. Cognitive skills and their acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathy A, Miller EK. Different time courses of learning-related activity in the prefrontal cortex and striatum. Nature. 2005;433:873–876. doi: 10.1038/nature03287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perruchet P, Vinter A. The self-organizing consciousness. Behav Brain Sci. 2002;25:297–330. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poreisz C, Boros K, Antal A, Paulus W. Safety aspects of transcranial direct current stimulation concerning healthy subjects and patients. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle L, Noël MP. Basic numerical skills in children with mathematics learning disabilities: a comparison of symbolic vs nonsymbolic number magnitude processing. Cognition. 2007;102:361–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsten O, Henik A. Developmental dyscalculia: heterogeneity may not mean different mechanisms. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg CJ, Bachtiar V, Johansen-Berg H. The role of GABA in human motor learning. Curr Biol. 2011;21:480–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terney D, Chaieb L, Moliadze V, Antal A, Paulus W. Increasing human brain excitability by transcranial high-frequency random noise stimulation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14147–14155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4248-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzelgov J, Yehene V, Kotler L, Alon A. Automatic comparisons of artificial digits never compared: learning linear ordering relations. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2000;26:103–120. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Aster MG, Shalev RS. Number development and developmental dyscalculia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:868–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]