Abstract

Objectives

One potential concern of once-daily protease inhibitor administration is low trough concentrations and ultimately the ‘forgiveness’ or robustness in comparison with the originally licensed twice-daily dose. To give an estimation of ‘forgiveness’, we determined the length of time plasma drug concentrations were below target in HIV-infected patients receiving saquinavir/ritonavir regimens.

Methods

Seventy-seven pharmacokinetic profiles (saquinavir/ritonavir 1000/100 mg twice daily, n = 34; 1600/100 mg once daily, n = 26; 2000/100 mg once daily, n = 17) from five studies were combined, presented as twice- and once-daily percentiles (P10–P90) and compared. At percentiles where trough concentrations fell below the alleged minimum effective concentration (MEC; 100 ng/mL), the length of time below MEC was determined.

Results

Saquinavir concentrations were below MEC at P10 for 0.7 h for twice-daily saquinavir/ritonavir when compared with 8.6 and 6.6 h for 1600/100 and 2000/100 mg once daily, respectively. At P25, 1600/100 mg once daily produced suboptimal concentrations for 5.5 h in contrast to 0.5 h for 2000/100 mg once daily.

Conclusions

Here, we provide substantive data that indicate once-daily saquinavir, in particular 1600/100 mg, is not as robust as the twice-daily regimen based on a population of UK patients; this raises concern over late or missed doses. However, pharmacokinetic data can only ever be a guide to the impact on long-term efficacy.

Keywords: HIV, pharmacokinetics, once daily, robustness

Introduction

The need for high levels of adherence in order to prevent resistance in protease inhibitor (PI) treatment failure attests to the unforgiving nature of antiretroviral therapy.1 In an effort to improve adherence, many patients are receiving once-daily boosted PI regimens (i.e. co-administered with low-dose ritonavir) with saquinavir, lopinavir and fosamprenavir (all originally being licensed for twice-daily use) and atazanavir. Any advantages gained by once-daily dosing must be offset against potential risks, chiefly that of achieving subtherapeutic trough concentrations towards the end of the dosing interval.

Given the large population variability of PI exposure seen with standard dosing, in clinical practice, a minority of patients are likely to have subtherapeutic concentrations or concentrations approximating to the minimum effective concentration (MEC) for virological suppression with twice-daily dosing. Consequently, there is little or no forgiveness for late doses. The inherent forgiveness of a boosted PI-containing regimen is dependent upon the intrinsic pharmacokinetic characteristics of the drug and the effectiveness of ritonavir boosting. Therefore, ‘stretching’ a drug normally given twice-daily to once-daily dosing may adversely impact upon its forgiveness for missed or late dosing. However, this relationship has not been adequately or quantitatively characterized.

The optimal once-daily dose of saquinavir/ritonavir has not yet been clearly defined, with most studies using 1600/100 or 2000/100 mg once-daily regimens.2 – 8 Moreover, limited efficacy data are available evaluating saquinavir/ritonavir once daily. In a cohort of 200 treatment-naive HIV patients, hard-gel saquinavir/ritonavir (1600/100 mg once daily) demonstrated a strong antiretroviral effect at 24 weeks with 96% and 89% of the individuals achieving a viral load of <400 and 50 copies/mL, respectively.9

In order to gain maximum therapeutic benefit from a regimen, plasma drug concentrations above the recommended MEC should be maintained throughout the dosing interval and thus limit the risk of developing drug resistance. There has been considerable debate about defining the in vivo MEC for individual antiretrovirals. A recent consensus document recommended that the cut-off for saquinavir minimum concentration (i.e. MEC) should be 100 ng/mL,10 which has been clinically validated in treatment-experienced patients based on twice-daily boosted saquinavir therapy.11 – 13 In a study by Boffito et al.,3 more patients were below the saquinavir MEC at trough (100 ng/mL) when administered saquinavir/ritonavir once daily (1600/100 and 2000/100 mg) compared with the standard twice-daily dose (100% patients above MEC at trough). Furthermore, fewer patients achieved trough concentrations above the MEC for the 1600/100 mg dose (50%) when compared with 2000/100 mg once daily (72%).3

The aim of this analysis was to determine how long saquinavir concentrations remained below the MEC during a dosing interval in a cohort of HIV-infected individuals and thereby to compare the ‘pharmacokinetic forgiveness’ of once-daily saquinavir/ritonavir (1600/100 and 2000/100 mg) with the standard twice-daily regimen (1000/100 mg).

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

Data were pooled from a total of five clinical pharmacokinetic studies designed to evaluate hard-gel saquinavir/ritonavir alone and in combination with other antiretroviral agents at various doses in HIV-1 antibody-seropositive males and females. The majority of the studies investigated the standard twice-daily dose of 1000/100 mg;3,14 – 16 however, 1600/1003,17 and 2000/100 mg once daily3 were also explored. All patients were recruited and assessed at one single UK site (PK Research Ltd, St Stephen’s Centre, Chelsea and Westminster Foundation Trust, London, UK). The design, inclusion/exclusion criteria and pharmacokinetic findings of each study have been reported previously.3,14 – 17 If an individual took part in more than one study receiving identical saquinavir/ritonavir doses, then only pharmacokinetic data generated from the first study participation were included. However, data from the same patient could be included at more than one saquinavir/ritonavir dose. Moreover, saquinavir data were only included at doses of 1000/100 mg twice daily, 1600/100 mg once daily and 2000/100 mg once daily, and not in combination with any other therapeutic agents (i.e. control phases of drug–drug interaction studies). Ethics Committee approval for all studies was granted by the Riverside Research Ethics Committee, and all individuals provided written informed consent.

Pharmacokinetic assessments and construction of percentile curves

All patients were stable on a saquinavir/ritonavir-containing regimen at least 2 weeks prior to the start of each study and were administered saquinavir/ritonavir as part of combination antiretroviral therapy. In brief, on the day of pharmacokinetic sampling, drug intake was directly observed, and timed and administered under fed conditions with either a standard 403 or 20 g14 – 17 fat-containing meal. Venous blood samples (7 mL) were drawn and collected into heparinized tubes pre-dose (0 h) and 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 h post-dose, and a 24 h post-dose sample if a once-daily regimen was administered. Saquinavir and ritonavir pharmacokinetics were assessed at steady state. Plasma was isolated (1000 g; 10 min; 4°C) within 2 h of sampling and stored (−70°C) until analysed.

Quantification of saquinavir and ritonavir in plasma was performed by fully validated high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS) methods as illustrated previously18 at the same laboratory with the exception of one study,17 which also used a fully validated HPLC–MS/MS method.19 Both laboratories participate in the same external quality assurance programme (International Interlaboratory Quality Control Programme for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in HIV Infection, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). Details of each assay’s performance have been described previously.3,14 – 17

To investigate whether there could be reduced pharmacokinetic forgiveness for late or missed dosing with saquinavir/ritonavir once daily (1600/100 and 2000/100 mg), percentile curves were constructed from full patient pharmacokinetic profiles of the 1000/100 mg twice-daily (n = 34), 1600/100 mg once-daily (n = 26) and 2000/100 mg once-daily (n = 17) regimens. Data for 1000/100 mg twice daily were obtained from four studies,3,14 – 16 whereas 1600/100 and 2000/100 mg once-daily data were combined from two studies3,17 and one study,3 respectively. The population percentile approach has been adapted from methods described by Acosta and King,20 and the use of concentration ratios as described by van der Leur et al.21 Percentile curves are a common tool used by our research group to aid interpretation of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) results.

Data analysis

Percentile curves were generated using the descriptive statistics tool of WinNonlin® (Version 5.0; Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). A comparison of the twice- and once-daily regimens was made by the examination of percentile curves and concentrations below the saquinavir MEC at trough (MEC, 100 ng/mL) noted for each regimen.

For the percentile data where saquinavir concentrations fell below the MEC (100 ng/mL) at trough (i.e. 12 or 24 h post-dose), the time at which concentrations reached 100 ng/mL (tMEC) was interpolated for each regimen based on first-order elimination between the last two concentration measurements (10 and 12 h for twice daily and 12 and 24 h for once daily). The equation

can be rearranged to determine time, t:

where t is the time when concentrations reached 100 ng/mL (tMEC), C0 is the next available time point with concentration data above the MEC (concentrations achieved at 10 or 12 h post-dose if administered a twice-daily or once-daily regimen, respectively), C is the saquinavir MEC of 100 ng/mL and k is the elimination rate constant calculated by k = 0.693/half-life. The half-lives of each percentile curve where concentrations fell below the MEC were calculated by WinNonlin®.

Once this time (tMEC) was calculated, estimations were made as to how long patients would experience below target concentrations before the next dose if their profile fell within these percentiles; given by tlast—tMEC (where tlast is 12 or 24 h for a twice-daily and once-daily regimen, respectively).

Results

Patients

A total of 77 saquinavir pharmacokinetic profiles were used to generate the percentile curves (1000/100 mg twice daily, n = 34; 1600/100 mg once daily, n = 26; and 2000/100 mg once daily, n = 17). The majority of the 34 patients were male (6 female; 3 of whom had data for all three saquinavir/ritonavir doses) and Caucasian (3 Black Africans; 2 of whom had data for all three doses) with a median (range) age and weight of 43 years (22–61) and 73 kg (49–105), respectively. Body weight did not differ significantly for the three dosing regimens (P ≥ 0.293 for all comparisons; ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). Median (range) CD4 count at screening was 353 cells/mm3 (76–970), and 20 patients had an undetectable viral load at baseline (<50 copies/mL). Detectable viral load measurements ranged between 91 and 14 580 copies/mL.

Percentile curves and estimation of tMEC

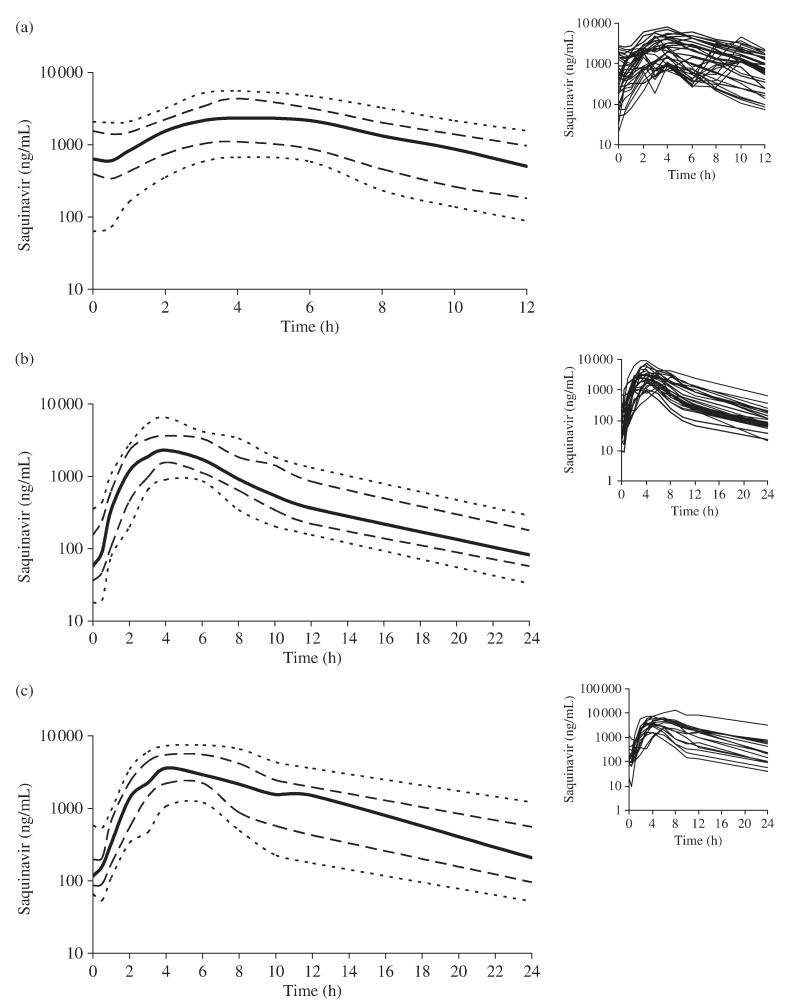

Saquinavir percentile curves (10th–90th percentile: P10–P90) are illustrated for each of the three saquinavir/ritonavir regimens studied (Figure 1). For the standard twice-daily regimen (1000/100 mg), saquinavir concentrations were below the recommended MEC at trough (12 h) in the 10th percentile (P10) when compared with the 50th percentile (P50) at trough (24 h) for 1600/100 mg once daily and the 25th percentile (P25) for 2000/100 mg once daily with values of 89, 82 and 96 ng/mL, respectively (Figure 1). It should also be noted that there is an absorption lag in the range 0–1 h and concentrations were below the recommended MEC for 18%, 65% and 41% of the patients at 0 h, 9%, 54% and 35% of the patients at 0.5 h post-dose and 3%, 23% and 0% of the patients at 1 h post-dose, for saquinavir/ritonavir 1000/100 mg twice daily, 1600/100 mg once daily and 2000/100 mg once daily, respectively.

Figure 1.

Saquinavir percentile curves (P10 and P90, dotted lines; P25 and P75, dashed lines; P50, solid bold line) presented on a log scale generated from pharmacokinetic profiles of patients receiving saquinavir/ritonavir. Saquinavir/ritonavir was dosed at (a) 1000/100 mg twice daily (n = 34), (b) 1600/100 mg once daily (n = 26) and (c) 2000/100 mg once daily (n = 17). Inset graphs show the raw data from which percentile curves were derived.

An example of how the length of time below MEC was calculated is illustrated (Figure 2). At P10, saquinavir concentrations were below the MEC for ~0.7 h when administered twice daily (1000/100 mg) compared with 8.6 and 6.6 h if receiving a dose of 1600/100 and 2000/100 mg once daily, respectively (Table 1). Comparing the once-daily regimens at P25, concentrations were below MEC for 5.5 versus 0.5 h for 1600/100 and 2000/100 mg once daily, respectively. Moreover, at P50, suboptimal concentrations were observed for 2.1 h prior to the next dosing interval for saquinavir/ritonavir 1600/100 mg once daily (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Saquinavir percentile curves (P10, P25 and P50) from 12 to 24 h post-dose (shown for 1600/100 mg once daily only). The graph represents the exponential decline described by C = C0×e−kt used to calculate t < MEC, i.e. the length of time patients were below the MEC (<100 ng/mL) before the next dosing interval. C0 represents the time at 12 h post-dose, C the saquinavir MEC of 100 ng/mL and tMEC (or t) the time when concentrations reached 100 ng/mL (data shown for P25 only).

Table 1.

Interpolated time of reaching the recommended minimum effective concentration (MEC, 100 ng/mL) for saquinavir (tMEC) in the percentiles where concentrations dropped below this threshold, and the length of time that concentrations were likely to be subtherapeutic before the next dosing interval (t < MEC) for the three evaluated saquinavir/ritonavir regimens

| 1000/100 mg twice daily |

1600/100 mg once daily |

2000/100 mg once daily |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | tMEC (h) | t < MEC (h) | tMEC (h) | t < MEC (h) | tMEC (h) | t < MEC (h) |

| P10 | 11.3 | 0.7 | 15.4 | 8.6 | 17.4 | 6.6 |

| P25 | — | — | 18.5 | 5.5 | 23.5 | 0.5 |

| P50 | — | — | 21.9 | 2.1 | — | — |

tMEC determined by rearrangement of standard pharmacokinetic formula: C = C0 × e−kt.

t < MEC is determined by subtracting tMEC from the last time point (i.e. 12 or 24 h for twice- and once-daily regimens, respectively): tlast — tMEC.

Discussion

In randomized controlled trials, once-daily saquinavir regimens have shown comparable short-term efficacy to the standard twice-daily dose in patients from Thailand with well-controlled HIV infection.22 It has long been suspected that some once-daily PI-based regimens are more fragile than twice-daily regimens. We have therefore proposed a means of quantitatively assessing this for saquinavir/ritonavir, which can be applied to other PIs (for example, lopinavir/ritonavir and fosamprenavir/ritonavir). We have used a simple pharmacokinetic analysis to compare populations of patients with trough concentrations below target (saquinavir MEC: 100 ng/mL10) for once-daily versus twice-daily regimens and to estimate, at fixed population percentiles, the duration that concentrations remain below the MEC prior to the next dose. The latter is important because it provides a quantitative measure of the window of opportunity for viral escape and the subsequent development of resistance.

We observed trough concentrations below the recommended saquinavir MEC (100 ng/mL) at P10 for all three regimens, at P25 for the two once-daily treatments (1600/100 mg and 2000/100 mg) and at P50 for saquinavir/ritonavir 1600/100 mg once daily. At P10 for 1600/100 mg once daily, concentrations were potentially subtherapeutic for ~8.6 h, in comparison with 6.6 and 0.7 h for 2000/100 mg once daily and 1000/100 mg twice daily, respectively. The scenario was slightly improved at P25, with saquinavir concentrations below target for 5.5 and 0.5 h for 1600/100 and 2000/100 mg once daily, respectively. Patients experienced suboptimal concentrations for a longer period of time during the dosing interval when administered once-daily saquinavir/ritonavir treatment, particularly 1600/100 mg, which also gave concentrations below the MEC for 2.1 h at P50. Thus, in some patients, a missed or late dose at this time would permit plasma saquinavir concentrations to fall further below target, therefore applying selective drug pressure and the potential to drive resistance. Clearly saquinavir/ritonavir 1000/100 mg twice daily is the most pharmacokinetically forgiving regimen of the three evaluated. However, it must also be noted that concentrations may fall below target following the second twice-daily dose. As drug kinetics are different in the evening, we were not able to estimate time below target following an evening dose due to the analysis being based on actual data and evening concentrations were not available. Furthermore, we realize that pooling of data may potentially bias interpretation of the results; to address this, an additional analysis was performed to determine the length of time individual patients were below target based on their own elimination rates. Of the 34 patients receiving 1000/100 mg twice daily, 4 (12%) were below target 12 h post-dose corresponding to a median (range) time below MEC of 0.6 h (0.2–1.9). For 1600/100 and 2000/100 mg once daily, 54% (14/26) and 24% (4/17) of the patients were below the saquinavir MEC at trough (24 h post-dose) for a median (range) of 5.0 h (1.6–11.0) and 3.5 h (0.6–8.8), respectively. Thus, irrespective of the method of analysis, similar conclusions can be drawn.

If concentrations were extrapolated for the median population (P50) for 1000/100 mg twice daily and 2000/100 mg once daily, patients do not reach the saquinavir MEC until ~18.7 and 29.2 h post-dose, respectively (data not shown). In other words, a patient on the 50th percentile receiving saquinavir 1000/100 mg twice daily would remain above target for up to 6.7 h beyond the next due dose, compared with 0 h for 1600/100 mg once daily and 5.2 h for 2000/100 mg once daily. The general consensus has been that high levels of adherence (>95%) are necessary in order to provide virological control.23 However, a recent study aimed to explore the level of adherence required to achieve virological suppression in patients receiving twice-daily lopinavir/ritonavir therapy. Based on the defined adherence quartiles, the authors observed no difference in patients achieving a viral load <75 or <400 copies/mL.24 These data reinforce that boosted PI-based regimens are more forgiving than earlier unboosted therapy, but as a cut-off for forgiveness has not been defined, we would not recommend flexibility in adherence based on the present saquinavir/ritonavir data as any length of time below target can clearly increase risk of treatment failure. Moreover, even though the threshold of adherence for successful outcome is debatable, the method described is still valid for comparing different groups of patients, for example, experienced versus naive MEC targets. Despite median (P50) twice-daily saquinavir concentrations persisting for ~7 h beyond the next due dose, in 10% of the patients receiving 1000/100 mg twice daily, saquinavir concentrations fell below target for a brief period (0.7 h) in the context of a clinical trial with close patient monitoring. It would appear that a subgroup of patients struggle to achieve target concentrations at the standard dose of 1000/100 mg twice daily and are therefore potentially at risk of failure. Many patients will remain virologically suppressed either because intracellular drug concentrations may remain adequate or the inhibitory quotient sufficiently high, or else residual activity of other drugs in the combination is sufficiently active. Nevertheless, the robustness of the entire regimen may still be compromised.

Even though concentrations are low in plasma, they may not accurately reflect concentrations within cells and at the site of drug action. Saquinavir has been shown to accumulate within lymphocytes and a study by Ford et al.25 evaluated the cellular concentrations achieved with a hard-gel saquinavir-boosted regimen administered to 12 HIV patients (1600/100 mg once daily). The median (range) ratio of cellular to plasma Ctrough was 7.64 (1.55–19.2), signifying that saquinavir enters the intracellular compartment and accumulates to approximately eight times that of plasma.25 Intracellular half-life was also significantly longer than plasma half-life [median (range) 5.9 h (4.0–17.7) versus 4.5 h (2.5–9.3)]25 and so, although the plasma concentrations may be below the recommended MEC, potentially saquinavir concentrations within cells are adequate and more forgiving for late doses. This could explain why twice- and once-daily saquinavir have shown comparable efficacy in Thai patients. Furthermore, Thai patients have been shown to experience three to four times higher saquinavir concentrations when compared with UK patients26 and are potentially more suited to receive saquinavir/ritonavir 1600/100 mg once daily. Indeed, 1600/100 or 1500/100 mg once daily (if 500 mg film-coated tablets are available) as well as 1000/100 mg twice daily are recommended in the National treatment guidelines in Thailand, whereas in the UK and USA, only twice-daily boosted saquinavir is recommended, although once-daily doses are used in clinical practice. It should also be recognized that the cut-off for saquinavir Cmin is based on clinical efficacy data available to date with the 1000/100 mg twice-daily dose. Therefore, different outcomes would be seen if, for example, we used an MEC of 50 ng/mL. Further data are required to support the definitive use of a particular MEC value for all regimens. Moreover, data have suggested that saquinavir AUC over a dosing interval may also be predictive of response with one study indicating that a higher saquinavir AUC corresponds to an increased likelihood of achieving an HIV viral load of ≤500 copies/mL.11 However, AUC is neither easily obtainable in a clinical setting or fully validated.

A longer elimination half-life can be considered a characteristic of drugs with the capacity for forgiveness. At steady state, concentrations remain relatively stable throughout the dosing interval and it is less likely that a late dose will substantially affect drug exposure or efficacy. In comparison with other PIs such as atazanavir or darunavir, or indeed the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, boosted saquinavir half-life is comparatively short (e.g. ~4 h for saquinavir versus 12 h for darunavir). A relatively short half-life and reduced ritonavir concentrations towards the end of a dosing interval are perhaps a contributing factor to the less forgiving pharmacokinetic properties of once-daily saquinavir.

Studies investigating once-daily dosing of lopinavir/ritonavir observed similar virological responses with once-daily therapy (800/200 mg) when compared with twice-daily therapy (400/100 mg) in treatment-naive patients.27 – 29 However, when patients were stratified into two groups based on screening HIV-RNA (<100 000 or ≥100 000 copies/mL), for those in the higher viral load strata, sustained virological response was significantly higher for the twice-daily regimen in comparison with once daily.29 In terms of pharmacokinetics and dosing history, another recent investigation showed that although cumulative execution of prescribed lopinavir regimens was higher for once-daily dosing when compared with twice-daily dosing, fewer patients never dropped below a target concentration of 1000 ng/mL for twice-daily dosing when compared with once-daily lopinavir (27% versus 16%).30 Furthermore, missing one once-daily dose equated to missing two to three consecutive twice-daily doses of lopinavir/ritonavir, the probability of which is almost half that of missing a single once-daily intake,30 implying superior pharmacokinetic forgiveness of twice-daily lopinavir regimens. However, forgiveness of an antiretroviral regimen is drug-specific, dependent on the pharmacokinetic profile and variability and genetic barrier to resistance as well as the pharmacodynamic effect.

In conclusion, according to the present analysis in a population of UK patients, as a result of shorter length of time below target, twice-daily saquinavir appears to be more robust than once-daily regimens, in particular 1600/100 mg once daily. It must be noted that these data imply the ‘best-case scenario’ as patients were part of carefully controlled clinical studies and, furthermore, may not relate directly to other patient populations (e.g. Thailand). Despite concerns over falling trough concentrations with once-daily therapy, saquinavir/ritonavir once-daily regimens are becoming a more attractive and convenient treatment option for patients. Nonetheless, caution must be exercised in order to strike a balance between improved adherence and risk of treatment failure. Potentially, once-daily therapy is better suited to the more adherent individuals and we suggest that once daily or unlicensed doses will benefit from TDM; however, pharmacokinetic data can only ever be a guide to the impact on long-term efficacy.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the staff of St Stephen’s Centre, London, and the patients for their participation in the clinical studies from which these data were derived.

Funding Clinical pharmacokinetic studies mentioned in this manuscript received financial support from Roche Products Ltd, Welwyn, UK. L. D.’s PhD was supported by Roche Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Transparency declarations L. D.’s PhD was supported by Roche Pharmaceuticals. D. J. B. and S. H. K. have acted as consultants for and received research grants from Roche Pharmaceuticals. M. S. is an employee of Roche Pharmaceuticals. M. B., A. L. P. and L. J. A.: none to declare.

References

- 1.Bangsberg DR, Acosta EP, Gupta R, et al. Adherence–resistance relationships for protease and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors explained by virological fitness. AIDS. 2006;20:223–31. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000199825.34241.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autar RS, Ananworanich J, Apateerapong W, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of saquinavir hard gel caps/ritonavir in HIV-1-infected patients: 1600/100 mg once-daily compared with 2000/100 mg once-daily and 1000/100 mg twice-daily. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:785–90. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boffito M, Dickinson L, Hill A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once-daily saquinavir/ritonavir in HIV-infected subjects: comparison with the standard twice-daily regimen. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:423–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardiello PG, Monhaphol T, Mahanontharit A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once-daily saquinavir hard-gelatin capsules and saquinavir soft-gelatin capsules boosted with ritonavir in HIV-1-infected subjects. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:375–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardiello PG, van Heeswijk RP, Hassink EA, et al. Simplifying protease inhibitor therapy with once-daily dosing of saquinavir soft-gelatin capsules/ritonavir (1600/100 mg): HIVNAT 001.3 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:464–70. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200204150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamotte C, Landman R, Peytavin G, et al. Once-daily dosing of saquinavir soft-gel capsules and ritonavir combination in HIV-1-infected patients (IMEA015 study) Antivir Ther. 2004;9:247–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montaner JS, Schutz M, Schwartz R, et al. Efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of once-daily saquinavir soft-gelatin capsule/ritonavir in antiretroviral-naive, HIV-infected patients. MedGenMed. 2006;8:36–40. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-8-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soria A, Gianotti N, Cernuschi M, et al. Once-daily saquinavir and ritonavir in treatment-experienced HIV-1-infected individuals. New Microbiol. 2004;27:11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ananworanich J, Hill A, Siangphoe U, et al. A prospective study of efficacy and safety of once-daily saquinavir/ritonavir plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in treatment-naive Thai patients. Antivir Ther. 2005;10:761–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.la Porte CJL, Back DJ, Blaschke T, et al. Updated guideline to perform therapeutic drug monitoring for antiretroviral agents. Rev Antivir Ther. 2006;3:4–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher CV, Jiang H, Brundage RC, et al. Sex-based differences in saquinavir pharmacology and virologic response in AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 359. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1176–84. doi: 10.1086/382754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valer L, De Mendoza C, De Requena DG, et al. Impact of HIV genotyping and drug levels on the response to salvage therapy with saquinavir/ritonavir. AIDS. 2002;16:1964–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valer L, de Mendoza C, Soriano V. Predictive value of drug levels, HIV genotyping, and the genotypic inhibitory quotient (GIQ) on response to saquinavir/ritonavir in antiretroviral-experienced HIV-infected patients. J Med Virol. 2005;77:460–4. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boffito M, Dickinson L, Hill A, et al. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of saquinavir hard-gel/ritonavir/fosamprenavir in HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1376–84. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000136060.65716.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boffito M, Back D, Stainsby-Tron M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of saquinavir hard gel/ritonavir (1000/100 mg twice daily) when administered with tenofovir diproxil fumarate in HIV-1-infected subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:38–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boffito M, Maitland D, Dickinson L, et al. Boosted saquinavir hard gel formulation exposure in HIV-infected subjects: ritonavir 100 mg once daily versus twice daily. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:542–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boffito M, Kurowski M, Kruse G, et al. Atazanavir enhances saquinavir hard-gel concentrations in a ritonavir-boosted once-daily regimen. AIDS. 2004;18:1291–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson L, Robinson L, Tjia J, et al. Simultaneous determination of HIV protease inhibitors amprenavir, atazanavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir and saquinavir in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;829:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurowski M, Sternfeld T, Sawyer A, et al. Pharmacokinetic and tolerability profile of twice-daily saquinavir hard gelatin capsules and saquinavir soft gelatin capsules boosted with ritonavir in healthy volunteers. HIV Med. 2003;4:94–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acosta EP, King JR. Methods for integration of pharmacokinetic and phenotypic information in the treatment of infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:373–7. doi: 10.1086/345993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Leur MR, Burger DM, la Porte CJ, et al. A retrospective TDM database analysis of interpatient variability in the pharmacokinetics of lopinavir in HIV-infected adults. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:650–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000245681.12092.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardiello P, Srasuebkul P, Hassink E, et al. The 48-week efficacy of once-daily saquinavir/ritonavir in patients with undetectable viral load after 3 years of antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2005;6:122–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shuter J, Sarlo JA, Kanmaz TJ, et al. HIV-infected patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy achieve high rates of virologic suppression despite adherence rates less than 95% J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:4–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d8c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford J, Boffito M, Wildfire A, et al. Intracellular and plasma pharmacokinetics of saquinavir-ritonavir, administered at 1,600/100 milligrams once daily in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2388–93. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2388-2393.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Autar RS, Boffito M, Hassink E, et al. Interindividual variability of once-daily ritonavir boosted saquinavir pharmacokinetics in Thai and UK patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:908–13. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eron JJ, Feinberg J, Kessler HA, et al. Once-daily versus twice-daily lopinavir/ritonavir in antiretroviral-naive HIV-positive patients: a 48-week randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:265–72. doi: 10.1086/380799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson MA, Gathe JC, Jr, Podzamczer D, et al. A once-daily lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimen provides noninferior antiviral activity compared with a twice-daily regimen. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:153–60. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242449.67155.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mildvan D, Tierney C, Gross R, et al. Randomised comparison in treatment-naive patients of once-daily vs twice daily lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART and comparison of once-daily self-administered vs directly observed therapy. Abstracts of the Fourteenth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Los Angeles, CA. Alexandria, VA, USA: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; [9 August 2007, date last accessed]. 2007. Abstract 138. http://www.retroconference.org/2007/Abstracts/28619.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comté L, Vrijens B, Tousset E, et al. Estimation of the comparative therapeutic superiority of QD and BID dosing regimens, based on integrated analysis of dosing history data and pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34:549–58. doi: 10.1007/s10928-007-9058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]