Abstract

Purpose of review

Formal Monod-Wyman-Changeux allosteric mechanisms have proven valuable in framing research on the mechanism of etomidate action on its major molecular targets, GABAA receptors. However, the mathematical formalism of these mechanisms makes them difficult to comprehend.

Recent findings

We illustrate how allosteric models represent shifting equilibria between various functional receptor states (closed versus open) and how co-agonism can be readily understood as simply addition of gating energy associated with occupation of distinct agonist sites. We use these models to illustrate how the functional effects of a point mutation, α1M236W, in GABAA receptors can be translated into an allosteric model phenotype.

Summary

Allosteric co-agonism provides a robust framework for design and interpretation of structure-function experiments aimed at understanding where and how etomidate affects its GABAA receptor target molecules.

Keywords: Allosteric model, Co-agonism, Equilibrium, General Anesthetic, Gibbs Free Energy, Mutation

Introduction

The modern era of research on general anesthetics began in the early 1980s with the paradigm-shifting work of Nicholas Franks and William Lieb, who critiqued the longstanding focus on unitary mechanisms and anesthetic-lipid interactions [1], and redirected the field toward proteins as anesthetic target molecules [2]. Research groups focused largely on neuronal ion channels and identified several dozen target candidates, based on the broad criteria of physiological plausibility plus sensitivity to clinically relevant anesthetic concentrations. From this work, it became apparent that the wide variety of clinical general anesthetics could be divided into several broad sub-classes based on their selectivity for various neuronal ion channels [3, 4]. Some anesthetic drugs, notably etomidate and alphaxalone, were recognized as remarkably selective for anesthetic targets, acting almost exclusively at γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors.

In the case of one drug, etomidate, we know the molecular targets; have identified the location of binding sites within those targets, and have developed quantitative functional models for anesthetic actions at the molecular level [5]. Etomidate has provided the best evidence for the presence of anesthetic binding sites within target protein molecules. Evidence includes enantioselectivity (stereospecificity) in animals and GABAA receptors [6–8], and single site mutations that dramatically alter etomidate sensitivity at both the molecular [9] and whole organism level [10, 11]. A photo-sensitive derivative of etomidate, azi-etomidate, covalently modifies two amino acids on separate GABAA receptor subunits [12]. Homology models of GABAA receptors, based on high-resolution structural data from homo-pentameric ligand-gated ion channels in both bacteria [13] and invertebrate flatworms [14], indicate that the photo-labeled residues reside on helical transmembrane domains that abut inter-subunit etomidate binding pockets. Typical synaptic GABAA receptors contain two such etomidate binding sites.

While the concepts of molecular drug-receptor interactions are widely familiar, the allosteric formalism used to describe how etomidate binding to its sites affects the function of GABAA receptors is difficult to comprehend. Understanding this mechanism is important, since it serves as the hypothetical framework for interpreting the effects of GABAA receptor mutations, other chemical modifications of the receptor, and structural modifications to the etomidate molecule. Thus, the major aim of this review is to review the basic concepts underlying two-state Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) Allosteric models as they apply to etomidate and GABAA receptors [15]. While these concepts have been reviewed in the past by others [16], I provide an illustrated model for understanding MWC agonism, based on the familiar ideas of chemical free energy and equilibria. This model is used to explain the functional interactions of GABA and etomidate in wild-type GABAA receptors and the “phenotype” of one receptor mutant.

Descriptive Analysis of Etomidate Actions on GABAA Receptors

In voltage-clamp electrophysiological studies of neuronal and heterologously expressed GABAA receptors, etomidate produces several functional effects [15]. Low concentrations of etomidate, including concentrations present in brain and blood during induction of general anesthesia (1–3 μM), enhance the activation of GABA-activated GABAA receptors. For example, when using a low concentration of GABA that elicits a sub-maximal response, addition of low concentrations of etomidate increases the amplitude of the receptor-mediated chloride current. Response to high maximally stimulating concentrations of GABA, similar to those at synapses (1–3 mM), is only enhanced about 15–20% by etomidate. If one studies receptor responses to a wide range of GABA concentration, addition of etomidate produces a large “leftward shift” in the concentration-response relationship. Thus, in the presence of etomidate, GABAA receptors become more sensitive to GABA (GABA EC50 is reduced).

In addition to enhancing GABA responses, high concentrations of etomidate (more than ten-fold higher than clinically relevant concentrations) directly activate GABAA receptors. Pharmacological and mutational studies have shown that this direct activation or agonism by etomidate is not mediated by the GABA binding sites of the receptors. However, etomidate’s direct agonism of GABAA receptors and its enhancement of GABA responses display remarkable parallels. The R(+) enantiomer of etomidate induces both of these actions 20-fold more potently than the S(−) enantiomer [7]. Both actions are produced in GABAA receptors containing β2 or β3 subunits, but not β1 [17], and mutations from asparagine (N) to methionine (M) at position 265 in β2 or β3 eliminates both etomidate actions [9]. These observations suggest that both etomidate modulation of GABA responses and its direct agonism of GABAA receptors are mediated by the same binding sites.

Based on these observations, we searched for mechanisms that account for both etomidate effects via a single class of sites. We found that MWC allosteric co-agonist models quantitatively account for the functional effects of GABA or etomidate alone and in combination with each other [15].

Monod-Wyman-Changeux Allosterism in a Simple Two-State Mechanism

Monod, Wyman, and Changeux introduced their allosteric model in 1965 [18], applying it to multi-subunit enzymes. MWC models assume that proteins exist in a limited number of functional states, and that all subunits shift between these states in a symmetrical and coordinated manner. The simplest MWC models have only two functional states (Fig. 1A): inactive and active, which in the case of ion channels can be translated as closed (C) and open (O) ion pore states. In the absence of ligands such as agonists, ion channels may spontaneously transition between closed and open states, although the probability of opening may be extremely small. The basal closed:open equilibrium parameter, L0 is related to spontaneous open probability by:

| Eq. 1 |

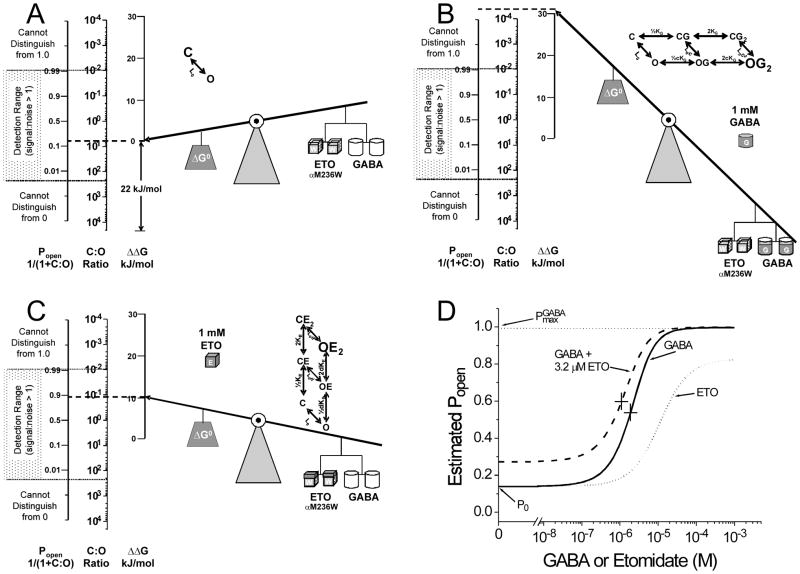

Figure 1. Two-state MWC allosteric gating models for GABAA receptors with zero, one, and two GABA sites.

Each panel depicts the free energy balance between opening and closing forces as a see-saw with closing forces on the left and opening (agonist) forces on the right. One scale shows the difference between basal gating energy (ΔG0) and that induced by addition of agonists (ΔΔG). Two other scales indicate the balance of closed:open (C:O) receptors and the corresponding open probability (Popen). Note that when opening vs. closing energy is equal (horizontal dashed line), C:O = 1 and open probability is 0.5. Insets show different states and equilibria, with dominant states identified with larger font size. Panel A depicts the basic two-state model, characterized by a single C:O equilibrium constant L0 = 20,000. The ΔΔG scale is set at zero for this C:O ratio. This low level of spontaneous activity cannot be detected using macrocurrent electrophysiology methods. Panel B depicts a MWC allosteric model with a single GABA (G) binding site. Using our estimated efficacy value for each GABA, corresponding to 16 kJ/mol of gating energy, binding of a single GABA molecule is expected to increase Popen to approximately 0.05. This prediction is remarkably consistent with results of experiments where one of the two GABA sites is altered with a βY205S mutation, dramatically reducing GABA affinity for that site [20]. Panel C depicts the MWC allosteric model of Chang & Weiss [19] with two equivalent GABA sites. At high GABA concentrations, occupation of both sites contributes 32 kJ/mol of gating energy, increasing Popen to about 0.85.

In the case of synaptic GABAA receptors consisting of α1, β2, and γ2 subunits, L0 is estimated to be about 20,000. That is, only about 1 in 20,000 channels is spontaneously open.

Agonists Shift the Two-State Equilibrium Toward Open States

MWC allosteric models explain agonism as a shift in the closed-open equilibrium oward open states. Moreover, this shift occurs because agonists bind more tightly to open receptors than to closed receptors. If we consider a model with only one GABA (G) binding site (Fig. 1B) a very high concentration of GABA will bind all receptors, so that only CG and OG states exist. Shifting the equilibrium more strongly toward OG occurs if GABA binds to O more tightly than to C. We define the dissociation constant for GABA binding to closed states as KG and to open receptors as KG* = cKG. Thus, if c < 1, GABA is an agonist. The factor c can be understood as a determinant of GABA efficacy, influencing the ratio of open versus closed receptors as GABA binds. As a thought experiment, consider that when c = 1, G binds with equal affinity to closed and open receptors, and its binding will not change the distribution of closed and open states. The cyclic constraints in the mechanism shown in Fig. 1B demand that the closed:open ratio for ligand-bound receptors (CG:OG) be cL0. Thus, at saturating high concentrations of GABA, the channel open probability in a one-site model becomes:

| Equation 2 |

Note that the maximum open probability depends on both c and L0 factors. If L0 is 20,000, then c must be smaller than 5 × 10−5 to result in Pmax > 0.5. However, when L0 is small, a model feature associated with spontaneous channel activity, then c can be only modestly less than 1 and still result in efficacious channel gating. The open probability as a function of [GABA] for a single site allosteric agonist model also includes the factor KG, which influences GABA binding to its site:

| Equation 3 |

Note that when [GABA] = 0, Eq. 3 becomes Eq. 1, and when [GABA] is very high, Eq. 3 becomes Eq. 2. GABAA receptors have two GABA binding sites. If we assume two equivalent agonist sites in the MWC model (Fig. 1C), then an equation similar to Eq. 3 describes open probability:

| Equation 4 |

At very high [GABA], equation 4 becomes Pmax = 1/(1+c2L0) and when L0 = 20,000, c < 7.1 × 10−3 will result in Pmax > 0.5. This MWC mechanism was experimentally demonstrated for GABA agonism by Chang & Weiss [19].

The MWC co-agonist model treats etomidate as an agonist that acts at sites distinct from those where GABA binds. Etomidate also acts at two equivalent sites. Thus, the action of etomidate alone is described by Eq. 5 using a binding factor KE and an efficacy factor, d:

| Equation 5 |

To describe activity as a function of both [etomidate] and [GABA], the full MWC co-agonist model treats them symmetrically, with five parameters (L0, KG, KE, c, and d):

| Equation 6 |

Co-agonism Explains Etomidate Actions as Energy Addition

Another way to understand MWC allosterism is to consider what the cyclic scheme means in terms of binding and gating energy. Essentially, ligand binding energy is equal to the energetic shift in the gating equilibrium. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG) associated with a chemical equilibrium, Keq, is:

| Equation 7 |

where R is the gas constant (8.314 J/K/mol), and T is absolute temperature (deg K). Figures 1 through 3 illustrate this concept as the balance of basal closed versus open forces (ΔG0) and the opening energy added when agonists occupy their sites. Figure 1A shows the basal gating energetics of wild-type α1β2γ2L GABAA receptors. The ΔΔG scale is “zeroed” to a closed:open ration (L0) of 20,000. The low detection limit in typical macrocurrent electrophysiology experiments is about 0.5% of channels activated, and for wild-type GABAA receptors, we estimate that additional activation energy of about 12 kJ/mol is required to detect macrocurrents. For α1β2γ2L receptors we estimated c, the efficacy factor for GABA, to be about 0.002 [15]. Using Eq. 7, we calculate that each GABA binding event provides about 16 kJ/mol of opening energy. When two GABA molecules bind, the addition of 32 kJ/mol of opening energy results in a shift to open probability of about 0.9 (Fig 1C). However, if we mutate one of the GABA sites to make its binding much weaker, an experiment performed by Baumann et al [20], then our model correctly predicts that, in comparison to normal receptors, mutant channels will activate only about 4–5% as efficiently (Fig. 1B).

Figure 3. Two-state MWC allosteric co-agonist model for α1M236Wβ2γ2L GABAA receptor gating by etomidate and GABA.

Panel A depicts the effect of the α1M236W mutations on basal gating activity. These receptors display about 15% spontaneous activity, corresponding to about 22 kJ/mol of gating energy in comparison to wild-type receptors. The ΔΔG scale has been zeroed to this open probability. Panel B depicts the high efficacy of GABA in α1M236Wβ2γ2L receptors. Assuming that the efficacy of GABA is unchanged from wild-type, maximal Popen is indistinguishable from 1.0. Panel C depicts why, despite etomidate’s low efficacy in α1M236Wβ2γ2L receptors, it appears to be a potent and efficacious agonist. Note that the gating energy associated with full etomidate occupancy of both mutated etomidate sites is only about 10 kJ/mol (compared with 24 kJ/mol in wild-type receptors; Fig. 2A). However, when added to the basal gating energy, this is sufficient to achieve a Popen near 0.9. Panel D depicts the α1M236Wβ2γ2L co-agonist model open probability as a function of varying GABA and etomidate (ETO). Data were generated using Equation 6 and the following parameters: L0 = 6.2; KG = 50 μM, KE = 24 μM, c = 0.02, d = 0.18. The solid line represents the GABA concentration response (Fig. 3B). The dashed line represents direct etomidate concentration-response (Fig. 3C). The dotted line represents GABA concentration-response in the presence of 3.2 μM etomidate. GABA EC50 is indicated by a “+” sign in each GABA response curve. Note the small leftward shift and the lack of increased maximal Popen in the presence of 3.2 μM etomidate.

Figure 2 depicts both etomidate and GABA as agonists, each with two equivalent sites. Etomidate’s efficacy factor, d, was estimated to equal 0.008, corresponding to about 12 kJ/mol of gating energy. This is a lower efficacy than GABA, and when high etomidate is present, the addition of 24 kJ/mol of gating energy results in an open probability of about 0.3 (Fig. 2A). The effect of a low concentration of etomidate alone (3 μM) is depicted in Figure 2B. This concentration of etomidate elicits barely detectable channel activity in macrocurrent experiments, indicating an open probability around 0.005, or about 12 kJ/mol of gating energy. However, addition of high GABA concentrations still results in 32 kJ/mol of additional binding energy, pushing the open probability of receptors close to 1.0 (Fig. 2C). The presence of a low concentration of etomidate also means that even low [GABA] will result in detectable channel activation--thus the leftward shift in GABA concentration responses (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Two-state MWC allosteric co-agonist model for α1β2γ2L GABAA receptor gating by etomidate and GABA.

Panel A: In comparison to Figure 1, two etomidate agonist sites have been added and ΔG0 is the same. The inset shows the model from Rusch et al [15] with the highlighted states involved in direct etomidate activation. Note that these states represent a model similar to that in Figure 1C. The low efficacy of etomidate (corresponding to 12 kJ/mol per site) results in Popen ≈ 0.35 with full etomidate occupancy. Panel B: In the presence of a clinical concentration of etomidate (3.2 μM) and no GABA, gating energy is just below the detection threshold for macrocurrent techniques (Popen ≈ 0.005). Panel C: In the presence of 3.2 μM etomidate, less GABA agonist energy is required to result in detectable current. As a result, receptors appear more sensitive to GABA and GABA also appears more efficacious, resulting in a maximal Popen indistinguishable from 1.0. Panel D depicts the co-agonist model open probability as a function of varying GABA and etomidate (ETO). Lines were generated using Equation 6 and the following parameters: L0 = 20,000; KG = 80 μM, KE = 20 μM, c = 0.002, d = 0.008. The solid line represents the GABA concentration response (Fig. 1C). The dashed line represents direct etomidate concentration-response (Fig. 2A). The dotted line represents GABA concentration-response in the presence of 3.2 μM etomidate (Fig. 2C). GABA EC50 is indicated by a “+” sign in each GABA response curve. Note the large leftward shift and the increase in maximal Popen in the presence of 3.2 μM etomidate.

Mutant Receptor Phenotypes Using an MWC Allosteric Framework

The MWC allosteric model enables quantitative analysis of the effects of GABAA receptor mutations within a consistent mechanistic framework. For example, a number of GABAA receptor mutations result in spontaneous channel activation in the absence of agonists [19, 21]. Traditional linear binding-gating mechanisms, which adequately describe the function of wild-type α1β2γ2L receptors, assume that agonist must bind before channels open. In essence, these mechanisms assume that an infinite energy barrier exists between closed and open states when agonist is absent. As a result, spontaneously gating mutant receptors such as α1L264Tβ2γ2L [15] cannot be described using this mechanism. In the framework of MWC allosteric mechanisms, spontaneous gating is associated with a low L0 value. In the case of α1L264Tβ2γ2L receptors, which display about 10% spontaneous activity, L0 ≈ 9.

The five parameters in Eq. 6 comprise the “phenotype” of a GABAA receptor as assessed by how GABA and etomidate affect its gating [22]. As noted above, the L0 parameter is intrinsic to the receptor and describes spontaneous gating. Experimentally, this is estimated using inhibitors like picrotoxin, which block spontaneously active channels [19, 23]. Once L0 is known, GABA concentration-response data can be used to estimate KG and c, using least squares regression to Eq. 4 [15]. Similarly, values for KE and d can be estimated by fitting concentration-response data for etomidate direct activation to Eq. 5 [15]. Data where combinations of etomidate and GABA are present together can be added and used in a global fit to Eq. 6 [24]. However, the data must first be normalized to an absolute open probability scale of 0 to 1.0. This is done by explicitly adding back spontaneous activity to baseline-adjusted data, and rescaling to estimated maximal GABA efficacy. Maximal GABA efficacy is estimated by adding strong positive modulators such as alphaxalone to maximal GABA [24]. Assuming that the maximal response to high GABA plus increasing [alphaxalone] results in an open probability near 1.0, one can back-calculate open probability in the presence of high GABA alone. We have recently described these methods in detail [25].

If all other parameters remain unchanged, a pure “binding” phenotype for an etomidate site mutation would alter KE without altering any other parameters in the model. Experimentally, this would appear as a change in the midpoint (EC50) of the etomidate direct activation response curve, without a change in its magnitude. A pure “efficacy” phenotype for an etomidate site mutation would alter the magnitude of etomidate direct activation. Both of these mutations would also alter the apparent interaction of etomidate with GABA.

Interpreting the Effects of an Etomidate Site Mutation: α1M236W

Most often, mutations do not affect only a single aspect of drug-receptor interactions. The case of the α1M236Wβ2γ2L receptor illustrates this point [24]. Experimentally, this mutant receptor displays many differences in comparison to wild-type α1β2γ2L receptors. The α1M236Wβ2γ2L receptors display spontaneous activation and increased sensitivity to GABA (Fig. 3). They also display sensitivity to etomidate as a direct agonist, but modulation by a low concentration (3 μM) of etomidate is much weaker than that observed in wild-type receptors. Thus, based on descriptive analysis alone, it is not clear whether the α1M236W mutation increases or decreases etomidate binding or efficacy.

Analysis within the MWC model framework readily explains these changes and enables us to conclude that the α1M236W mutation actually reduces etomidate efficacy. First, the spontaneous activity of α1M236Wβ2γ2L receptor is about 15%, indicating a very low L0 value near 6. This translates into about 22 kJ/mol of gating energy (Fig. 3A). Because these receptors have a high propensity to open, addition of very little GABA or etomidate gating energy is needed to activate more receptors. This explains the apparently increased sensitivity to either agonist (Figs. 3B and 3C). In addition, the small degree of GABA modulation by 3 μM etomidate indicates reduced binding or efficacy relative to wild-type. Quantitative analysis suggests that efficacy is in fact reduced--instead of high [etomidate] adding 24 kJ/mol of gating energy in wild-type receptors (Fig. 2A), etomidate only adds 10–11 kJ/mol of gating energy in the mutant receptors (Fig. 3C), yet this is sufficient to open nearly all channels. Thus the overall MWC phenotype readily explains the observations that etomidate is a potent and efficacious direct agonist, but produces only a small “left shift” in α1M236Wβ2γ2L receptors (Fig 3D).

Conclusion

The use of quantitative mechanistic models is an important advance over descriptive data analysis. We introduced an MWC allosteric co-agonist model for etomidate actions at its major molecular target [15], and are using this model as an interpretive framework to better understand how GABAA receptor mutations [24, 26] affect interactions with this anesthetic. To date, the MWC co-agonist model has proven robust-- we have not yet encountered a mutation that disobeys the underlying assumptions of the mechanism. The model also provides a framework for designing experiments to explore the etomidate binding sites in more detail. Furthermore, we have recently found that propofol actions at GABAA receptors are consistent with a similar MWC model, and the data indicate that more than two propofol sites may exist on each GABAA receptor [27].

While the underlying concepts and mathematical formalism of MWC allosteric models can take considerable time to understand, some of these ideas are readily understood and illustrated as elements that shift the energy balance between open and closed states, resulting in a measurable shift in channel open probability.

Key Points.

MWC models assume equilibration amongst more than one pre-existing states, without presuming infinite energy barriers between these states.

MWC models define agonists as ligands that bind more tightly to open vs. closed channel states. Selective binding results in an equilibrium shift toward the preferred states.

Ligand effects in MWC models can be readily understood as shifting the free energy balance between states.

MWC Co-agonist models can be readily understood as additive energy contributions of independent agonists binding to distinct sets of sites.

MWC co-agonist models have proven useful in understanding the functional effects of mutations in the etomidate sites of GABAA receptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants (P01GM58448 and R01GM089745).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The author has no conflicts of interest related to the content of this work. The author receives support from NIH grants (P01GM58448 and R01GM089745) for basic research, some of which is described in this work. The author is an inventor on patents for general anesthetic drugs that are not mentioned in this work. These patents are owned by the author’s employer, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the author has received no royalty payments.

References

- 1.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Is membrane expansion relevant to anaesthesia? Nature. 1981;292(5820):248–51. doi: 10.1038/292248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Do general anaesthetics act by competitive binding to specific receptors? Nature. 1984;310(5978):599–601. doi: 10.1038/310599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grasshoff C, Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Molecular and systemic mechanisms of general anaesthesia: the ‘multi-site and multiple mechanisms’ concept. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2005;18(4):386–91. doi: 10.1097/01.aco.0000174961.90135.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solt K, Forman SA. Correlating the clinical actions and molecular mechanisms of general anesthetics. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2007;20(4):300–6. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32816678a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5*.Forman SA. Clinical and molecular pharmacology of etomidate. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(3):695–707. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ff72b5. This paper reviews the unique clinical and molecular pharmacology of etomidate, illustrating why we know more about this drug than any other general anesthetic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Violet JM, Downie DL, Nakisa RC, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Differential sensitivities of mammalian neuronal and muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to general anesthetics [see comments] Anesthesiology. 1997;86(4):866–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husain SS, Ziebell MR, Ruesch D, Hong F, Arevalo E, Kosterlitz JA, et al. 2-(3-Methyl-3H-diaziren-3-yl)ethyl 1-(1-phenylethyl)-1H-imidazole-5-carboxylate: A derivative of the stereoselective general anesthetic etomidate for photolabeling ligand-gated ion channels. J Med Chem. 2003;46(7):1257–65. doi: 10.1021/jm020465v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belelli D, Muntoni AL, Merrywest SD, Gentet LJ, Casula A, Callachan H, et al. The in vitro and in vivo enantioselectivity of etomidate implicates the GABAA receptor in general anaesthesia. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belelli D, Lambert JJ, Peters JA, Wafford K, Whiting PJ. The interaction of the general anesthetic etomidate with the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor is influenced by a single amino acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11031–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.11031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, Drexler B, Siegwart R, Crestani F, et al. General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABA(A) receptor beta3 subunit. FASEB Journal. 2003;17(2):250–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds DS, Rosahl TW, Cirone J, O’Meara GF, Haythornthwaite A, Newman RJ, et al. Sedation and anesthesia mediated by distinct GABA(A) receptor isoforms. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(24):8608–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li GD, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J Neurosci. 2006;26(45):11599–605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bocquet N, Nury H, Baaden M, Le Poupon C, Changeux JP, Delarue M, et al. X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature. 2009;457:111–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Hibbs RE, Gouaux E. Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10139. This paper describes the first high-resolution crystal structure of a eukaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel with an allosteric agonist, ivermectin, bound at sites homologous to etomidate sites on GABAA receptors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rüsch D, Zhong H, Forman SA. Gating allosterism at a single class of etomidate sites on alpha1beta2gamma2L GABA-A receptors accounts for both direct activation and agonist modulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20982–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Changeux JP, Edelstein SJ. Allosteric mechanisms of signal transduction. Science. 2005;308(5727):1424–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1108595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill-Venning C, Belelli D, Peters JA, Lambert JJ. Subunit-dependent interaction of the general anaesthetic etomidate with the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;120:749–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux J. On the nature of allosteric transitions: A plausible model. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang Y, Weiss DS. Allosteric activation mechanism of the alpha1beta2gamma2 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor revealed by mutation of the conserved M2 leucine. Biophys J. 1999;77(5):2542–51. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77089-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumann A, Baur R, Sigel E. Individual properties of the two functional agonist sites in GABA(A) receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11158–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11158.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Findlay GS, Ueno S, Harrison NL, Harris RA. Allosteric modulation in spontaneously active mutant gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;305(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galzi JL, Edelstein SJ, Changeux J. The multiple phenotypes of allosteric receptor mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(5):1853–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheller M, Forman SA. Coupled and uncoupled gating and desensitization effects by pore domain mutations in GABA(A) receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(19):8411–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08411.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart DS, Desai R, Cheng Q, Liu A, Forman SA. Tryptophan mutations at azi-etomidate photo-incorporation sites on α1 or β2 subunits enhance GABAA receptor gating and reduce etomidate modulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1687–95. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Forman SA, Stewart D. Mutations in the GABA-A receptor that mimic the allosteric ligand etomidate. In: Fenton AW, editor. Allostery: Methods and Protocols. New York, N.Y: Humana Press; 2011. pp. 317–34. In this paper, we explain in detail the methods we use to measure and renormalize electrophysiological data and fit it to allosteric models. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai R, Ruesch D, Forman SA. Gamma-amino butyric acid type A receptor mutations at beta2N265 alter etomidate efficacy while preserving basal and agonist-dependent activity. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(4):774–84. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b55fae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Ruesch D, Neumann E, Wulf H, Forman SA. An Allosteric Coagonist Model for Propofol Effects on alpha1beta2gamma2L gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptors. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(1):47–55. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823d0c36. This paper reports that propofol, a widely used intravenous anesthetic that modulates GABAA receptors, acts via an allosteric co-agonist mechanism, just like etomidate. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]