Abstract

RATIONALE

Mass spectrometry based comparative glycomics is essential for disease biomarker discovery. However, developing a reliable quantification method is still a challenging task.

METHODS

We here report an isotopic labeling strategy employing stable isotopic iodomethane for comparative glycomic profiling by LC-ESI-MS. N-Glycans released from model glycoproteins and blood serum samples were permethylated with iodomethane (“light”) and iodomethane-d1 or -d3 (“heavy”) reagents. Permethylated samples were then mixed at equal volumes prior to LC-ESI-MS analysis.

RESULTS

Peak intensity ratios of N-glycans isotopically permethylated (Heavy/Light, H/L) were almost equal to the theoretical values. Observed differences were mainly related to the purity of “heavy” iodomethane reagents (iodomethane-d1 or -d3). The data suggested the efficacy of this strategy to simultaneously quantify N-glycans derived from biological samples representing different cohorts. Accordingly, this strategy is effective in comparing multiple samples in a single LC-ESI-MS analysis. The potential of this strategy for defining glycomic differences in blood serum samples representing different esophageal diseases was explored.

CONCLUSIONS

LC-ESI-MS comparative glycomic profiling of isotopically permethylated N-glycans derived from biological samples and glycoproteins reliably defined glycan changes associated with biological conditions or glycoproteins expression. As a biological application, this strategy permitted the reliable quantification of glycomic changes associated with different esophageal diseases, including high grade dysplasia, Barrett’s disease and esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Permethylated N-Glycans, Stable Isotopic permethylation, Comparative glycan quantification, Multiplex quantification, LC-ESI-MS

Introduction

Glycosylation is one of the most common and structurally diverse post-translation modifications of proteins and lipids. More than 50% of proteins are N- and O-glycosylated [1]. This does not include O-GlcNAc modification or sulfation and acetylation of glycans attached to polypeptides [2]. Glycosylation of proteins plays essential roles in many integral biological functions [3]. Moreover, the functions of many glycoconjugates are modulated by glycosylation. Additionally, aberrant glycosylation of proteins has been implicated in many diseases [4, 5], including cancer [6–11]. Therefore, reliable quantification of glycans is currently considered to be of considerable importance for biomarker discovery and early stage disease diagnosis.

Recently, several studies have demonstrated the utility of glycomic profiling to assess cancer development and progression [12–25]. Developing a robust quantification method is essential for investigating the changes in glycosylation in biological systems. Typically, there are two types of quantification strategies: one is label-free and the other involves the use of stable isotopic reagents. Label-free quantification is limited by the need for normalization to account for the different ionization efficiencies of analytes and instrument response instabilities. Using relative quantification strategies with stable isotopic reagents can reduce the influence of instrument response and ionization variation prompted by experimental variation. Meanwhile, stable isotope labeling could be employed to simultaneously analyze samples representing different biological conditions such as disease states. The most widely applied isotopic quantification methods involve metabolic (in vivo) stable isotopic labeling [26] or incorporating an isotopic label in common glycan derivatization strategies such as reductive amination [27–30] and permethylation [31, 32].

Metabolic labeling of glycans with an isotopic amino acid or sugar are examples of isotopic labeling strategies. Orlando and co-workers [26] have introduced isotopic labeling in cell culture. This strategy involves the incorporation of 15N into N-linked glycans by using amide-15N-Gln media. This strategy minimizes variations associated with sample preparation. However, incorporating the isotopic reagent is limited to living organisms.

Reductive amination reagents suitable for stable-isotopic labeling have been developed to modify the reduced end of N-glycans and allow for relative quantification. Several reductive amination reagents for the quantification of glycans have been developed, including 2-aminopyridine (d0-PA, d4-PA) [33], 2-aminobenzoic acid (d0-AA, d4-AA) [34] and aniline ([12C6], [13C6]) [30]. Zaia and coworker [27] synthesized a stable isotope-labeled tag in four forms (+0,+4,+8,+12) and labeled the reduced end of glycans. Direct comparison of four samples was achieved through this method. However, one disadvantage of this method is a need for theoretical simulations to extract ion abundance to account for the overlap of isotopic distributions.

Stable isotopic labeling of N-glycans through permethylation is an alternative to reductive amination and offers many advantages, including enhanced ionization efficiency, enhanced hydrophobicity, and simplified tandem MS interpretation. The enhanced hydrophobicity as a result of permethylation allows separation on a C18 column. Also, permethylation permits the simultaneous detection of both neutral and acidic glycans in positive ion mode mass spectrometry. Orlando and coworkers [31] utilized 13CH3I and 12CH2DI to generate a pair of isobaric derivatives with a mass difference of 0.002922 Da for each methylation site. High resolution mass spectrometry (m/Δm > 30000) is required to distinguish such minute m/z differences. Another isotopic reagent pair for permethylation is CH3I and CD3I, which was recently reported by Mechref and Novotny [32]. This differential permethylation permits relative quantification of different samples to be achieved in a single MALDI-MS analysis.

We here used different permethylation reagents (iodomethane and iodomethane-d1 or -d3) to permethylate N-glycans derived from model glycoproteins (RNase B, fetuin) prior to their LC-ESI-MS analyses using reversed-phase chromatographic media as we have recently described [35, 36]. Also, blood serum was permethylated with “heavy” (CH2DI or CD3I) and “light” (CH3I) reagents and mixed at 1:1 ratio to evaluate the quantification aspects of N-glycan pairs. The method was then applied to determine glycomic differences among different esophageal diseases. High grade dysplasia (HGD), Barrett’s disease and esophageal adenocarcinoma samples were derivatized with CD3I reagent while samples collected from disease-free (DF) subjects were labeled with CH3I reagent. Disease samples and DF sample were then mixed at 1:1 volume ratios and subjected to LC-ESI-MS analysis. This comparative glycomic profiling by LC-ESI-MS is effective in depicting the N-glycan differences among esophageal disease samples and DF samples.

Experimental

Materials

Borane-ammonia complex (97%), sodium hydroxide beads, dimethyl sulfoxide, iodomethane, iodomethane-d1, iodomethane-d3, trifluoroacetic acid, MS-grade formic acid, ribonuclease B (RNase B), fetuin, and pooled human blood serum (HBS) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Empty microspin columns and graphitized carbon and C18 microspin columns were purchased from Harvard Apparatus (Holliston, MA). Acetic acid, HPLC-grade methanol and HPLC-grade isopropanol were procured from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) while HPLC-grade acetonitrile was obtained from JT Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ). HPLC-grade water was acquired from Mallinckrodt Chemicals (Phillipsburg, NJ). N-Glycosidase purified from Flavobacterium meningosepticum (PNGase F) was obtained from New England Biolabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA).

Release of N-Glycans from Model Glycoproteins

PNGase F was used for enzymatic release of N-glycans from RNase B, fetuin. The process was performed according to a previously published procedure [32, 37, 38]. Briefly, a 9-μL aliquot of 10x diluted G7 solution (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5) was added into a 1-μL aliquot of glycoproteins (1μg/ μL). The samples were then mixed prior to the addition of a 1.2-μL aliquot of PNGase F. Next, samples were incubated at 37°C in a water bath for 18h.

Release of N-Glycans from Esophageal Disease and DF Pooled Blood Serum Samples

Human blood serum samples were provided by Dr. Zane Hammoud of Henry Ford Medical Systems, Detroit, MI. Samples were collected under Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocols with the consent of donors. Barrett’s esophagus serum samples (N=7), high-grade dysplasia (HGD, N=11) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (N=59) serum samples were individually pooled. Serum samples from 61 DF volunteers were also pooled and used as control. A 1-μL aliquot of each disease and DF samples were pipetted into four separate vials. 90-μL Aliquots of PBS were added into each disease and DF vials containing 10 μL of pooled blood serum. Then, a 1.2-μL aliquot of PNGase F was added, and reaction mixtures were placed in a 37°C water bath overnight.

Purification of N-Glycans Derived from Blood Serum

Graphitized carbon microspin columns were used for the purification of released N-glycans from pooled blood serum, disease and DF samples as previously described [39–41]. Briefly, the graphitized carbon spin column was washed with a 400-μL aliquot 100% ACN and two 400-μL aliquots of 85% ACN aqueous solution (0.1 % TFA) were applied twice. The column was then conditioned with a 400-μL aliquot of 5% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). This step was repeated twice. A 690-μL aliquot of 5% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) was added to the enzymatically released glycans and centrifuged at 10k rpm for 30 min prior to loading on the conditioned activated charcoal microspin columns. Then, 5% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) was used to wash nonspecifically bound material. This step was repeated five times. Finally, glycans were eluted using a 200-μl aliquot of 40% aqueous ACN (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). This elution step was repeated one more time, prior to drying the eluants under vacuum.

Reduction of N-glycans

Fresh ammonium-borane complex solution (10 μg/μL) was prepared in 29% ammonium hydroxide solution. A 10-μL aliquot of this solution was added to the purified N-glycans enzymatically released from model glycoproteins and HBS samples to reduce all glycans. The samples were then placed at 65°C in a water bath for 1h before adding a 100-μL aliquot of acetic acid (10%). Then, the reaction mixtures were dried under vacuum. Next, methanol was added to evaporate borate salt. 100 μL of methanol was added to each sample and dried. This step was repeated several times to remove all borate salt.

Permethylation of N-glycans

Iodomethane (CH3I), iodomethane-d1 (CH2DI) and iodomethane-d3 (CD3I) were used to permethylate N-glycans enzymatically released from model glycoproteins and pooled blood serum. N-glycans enzymatically released from DF HBS were permethylated with iodomethane while those released from Barrett’s disease, HGD and esophageal adenocarcinoma BS samples were methylated with iodomethane-d3. Permethylation was performed following the previously reported procedure [37, 38, 42]. First, empty microspin columns were filled to a 3-cm depth with sodium hydroxide beads and washed twice with a 50-μL aliquot of DMSO. Samples were prepared in 30 μL DMSO and 1.2 μL water. A 20-μL aliquot of iodomethane or iodomethane-d3 (CH3I or CD3I) was applied to purified and reduced N-glycans from RNase B, fetuin and pooled blood serum. 20 μL of iodomethane (CH3I) was added to the DF HBS samples while 20 μL of iodomethane-d3 (CD3I) was added to the disease samples. The reaction mixtures were then applied to microspin columns packed with sodium hydroxide beads and allowed to sit for 25 min. Another 20-μL aliquot of iodomethane or or iodomethane-d3 (CH3I CD3I) was added into each sample. The reaction was allowed to proceed for another 15 min. Next, a 50-μL aliquot of ACN was added to the column and centrifuged at low speed (1000 rpm). This step was repeated twice to ensure quantitative elution of all permethylated N-glycans.

Solid-phase purification of N-glycans

C18 microspin columns were used for the purification of permethylated N-glycans. C18 columns were washed with 100% ACN and 85% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). The columns were then conditioned with 5% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). A 690-μL aliquot of 5% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) was added to the sample prior to loading on the column. Next, the column was washed with 5% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) three times and then 80% ACN aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) was applied to elute the N-glycans from the column. The samples were dried under vacuum and resuspended in 20% ACN for LC-ESI-MS analysis.

LC-ESI-MS

Reduced and isotopically permethylated N-glycans were separated by nano-LC (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) on reverse phase Acclaim® PepMap capillary column (150 mm x 75 μm i.d) packed with 100 Å C18 bounded phase (Dionex). Separation was attained using a two solvent system; solvent A consisted of 2% acetonitrile and 98% water with 0.1% formic acid while solvent B consisted of acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid. Separation was attained using gradient conditions (38%–45% solvent B over 32 min, followed by 10 min wash with 80% B, and conditioned for 10 min with 20%B). The LC system was operated at a flow rate of 350 nL/min. The Nano-LC system was interfaced to a Velos LTQ Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). The mass spectrometer was operated in an automated data-dependent acquisition mode in which the scan mode switched between MS full scan (m/z from 500–2000) and CID MS/MS scan which was conducted on the 8 most abundant ions with a 0.250 Q-value, 20 ms activation time, and 35% normalized collision energy.

Data Evaluation

LC-ESI-MS data acquired were processed using Xcarlibur Qual Browser (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The isotopic masses of glycans were used to generate extracted ion chromatograms with 10 ppm mass tolerance. A seven-point boxcar smoothing was enabled to improve peak quality. The integrated peak areas of ion adducts representing the same glycan structure were summed. This value is used to represent the abundance of a glycan structure. MS spectra of glycans were obtained by averaging over the LC profile. Tandem mass spectra of glycans were within the elution profile representative of each glycan structure. B-, C-, X-, Y-ion series were the common fragment ions observed in tandem MS. Examples of such tandem mass spectra of “light” and “heavy” permethylated glycans are included in supplementary data.

Results and Discussion

Comparative glycomic mapping (C-GlycoMAP) was introduced by Mechref and Novotny [32] for MALDI-MS analysis of N-glycans, which were permethylated using iodomethane and iodomethane-d3. This strategy was effective in comparing the glycomic profiles derived from blood serum for samples representing different stages of breast cancer. We here extend C-GlycoMAP to LC-ESI-MS analysis of N-glycans which were permethylated using multiple stable isotopic iodomethane reagents. This should enable simultaneous multiplex comparative glycomic mapping (MC-GlycoMAP) of glycans derived from different biological samples.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow for LC-ESI-MS MC-GlycoMAP. N-Glycans were enzymatically released from equal amounts of proteins, or equal volumes of human blood serum samples using PNGase F. Released N-glycans were then reduced and isotopically permethylated using iodomethane, iodomethane-d1 or iodomethane-d3. Equal amounts of differentially permethylated N-glycans (using iodomethane, iodomethane-d1 or iodomethane-d3) were subsequently mixed prior to LC-ESI-MS analyses. Chromatographic separation on reversed-phase columns prompts the efficient separation of “light” and “heavy” permethylated glycans.

Figure 1.

Schematic of sample preparation process for MC-GlycoMap.

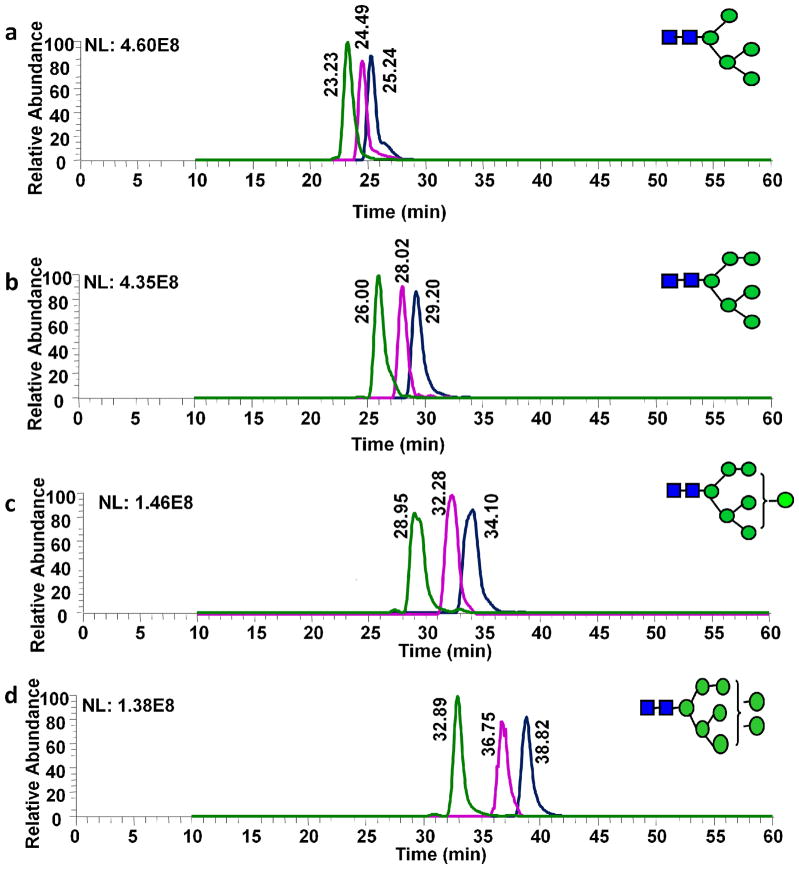

Comparative quantification of permethylated N-glycans derived from model glycoproteins

N-Glycans derived from RNase B and fetuin were employed to explore the potential of isotopic permethylation for comparative glycan quantification. The same glycans were also employed to assess the repeatability and permethylation efficiency of the three stable isotopic iodomethane reagents. Equal aliquots of RNase B N-glycans were simultaneously released and differentially labeled with stable isotopic iodomethane reagents (“light” CH3I, and “heavy” CH2DI or CD3I). The chromatographic retention times of isotopically permethylated N-glycans derived from RNase B were different, thus prompting the efficient separation of all species (Figure 2). Equal amounts of iodomethane, iodomethane-d1 and iodomethane-d3 permethylated RNase B N-glycans were mixed and subjected to LC-ESI-MS. The peaks areas of all isotopically permethylated N-glycans were representative of their natural distribution. Each permethylated N-glycan structure formed multiple adducts in the ESI source. The most intense ions were representative of protonated and ammoniated ([M+H+NH4]2+) ions. Moreover, the intensities of singly protonated and ammoniated ions were representative of the intensities of all adducts. The retention times of CH2DI or CD3I permethylated glycans are lower than that of CH3I permethylated counterparts. Moreover, the retention times of CD3I permethylated glycans are less than that of CH2DI permethylated counterparts. The retention time difference between Man 5 pair was 3.19 min while there was 6.52 min difference between “heavy” and “light” permethylated Man 8 counterparts. This is due to the higher number of permethylation sites. The retention time difference decreased for Man 9 counterparts, which is due to solvent B being increased to 80% at 43 min to 48 min. The hydrophobic differences among all pairs prevented the isotopic peak overlap while the isotopic mass difference provides sufficient m/z value dispersion. Therefore, each isotopically labeled species was distinguished and quantified without interference from the isotopic distribution of its counterparts. The peak area ratios (CD3:CH2D:CH3) were 1.10:0.87:1, 1.11:0.86:1, 0.89:1.02:1, 1.01:0.90:1, and 1.12:1.27:1 for Man 5 (Figure 2a), Man 6 (Figure 2b), Man 7 (Figure 2c), Man 8 (Figure 2d), and Man 9(Figure 2e), respectively. Peak area differences were attributed to ionization efficiencies dictated by the mobile phase composition as well as to the isotopic purity of iodomethane reagents.

Figure 2.

Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) and MS spectra of Man 5 (a), Man 6 (b), Man 7 (c), Man 8 (d), and Man 9 (e) glycans derived from RNase B. Equal amounts of N-glycans released from RNase B were permethylated with iodomethane (CH3I), iodomethane-d1 (CH2DI) and iodomethane-d3 (CD3I) reagents and mixed prior to LC-ESI-MS analysis. The peak area ratios were 1.10:0.87:1 (a), 1.11:0.86:1 (b), 0.89:1.02:1(c), 1.01:0.90:1(d), and 1.12:1.27:1(e). Symbols: as in Table 1.

The comparative glycomic quantification strategy was also evaluated using the six sialylated N-glycans derived from fetuin. N-glycans were released from fetuin and “light” and “heavy” permethylated using CH3I and CD3I reagents, respectively. The samples were mixed together after purification using C18 cartridges (see Experimental section). The purified and mixed samples were then subjected to LC-ESI MS analysis. Extracted ion chromatograms of the four most abundant fetuin N-glycans are depicted in Figure 3. The most intense ions of these glycan structures were [M+3H]3+ or [M+2H+NH4]3+. The extracted ion chromatograms and mass spectra of H4N5S1 glycan with 809.0916 m/z values (“light” permethylated) and 844.3113 (“heavy” permethylated) are depicted in Figure 3a. The peak heights of the “heavy” permethylated glycans relative to that of “light” permethylated ones (H/L) for H4N5S1 (Figure 3a), N4H5S2 (Figure 3b), N5H6S3 (Figure 3c), and N5H6S4 (Figure 3d) were 1.07, 1.11, 0.99, and 1.10, respectively. The peak area ratios (H/L) for the same structures were 1.05, 1.14, 0.99, and 1.12, respectively. Similar to N-glycans derived from RNase B, the intensities of “heavy” permethylated N-glycans and “light” N glycans are not identical. However, the intensity varies within ±11.4 % of the theoretical values. Again this difference is lower than the variation routinely observed in label-free ESI-based quantification methods and can be partially attributed to the purity of isotopic iodomethane reagents.

Figure 3.

EIC and MS spectra of biantennary monosialylated (a) biantennary disialylated (b), triantennary trisialylated (c), and triantennary tetrasiaylated (d) N-glycans derived from fetuin. Equal amounts of N-glycans released from fetuin were “heavy” and “light” permethylated using CH3I and CD3I reagents, respectively. The H/L peak area ratios were 1.07 (a), 1.11(b), 0.99(c), and 1.10(d). Symbols: as in Table 1.

Comparative quantification of isotopically permethylated N-glycans derived from blood serum

Serum glycomics profiling is important for the discovery of human disease biomarkers, as has been demonstrated by several studies [13, 14, 19–22, 25]. To explore the potential of employing the comparative quantification of glycans for complex biological samples, two equal volumes of blood serum samples were subjected to PNGase F treatment prior to “heavy” and “light” permethylation and LC-ESI-MS analysis. This analysis permitted the detection of 73 glycan structures. The ratios of their peak heights or areas were also within ±11.4 % of the theoretical values (data not shown).

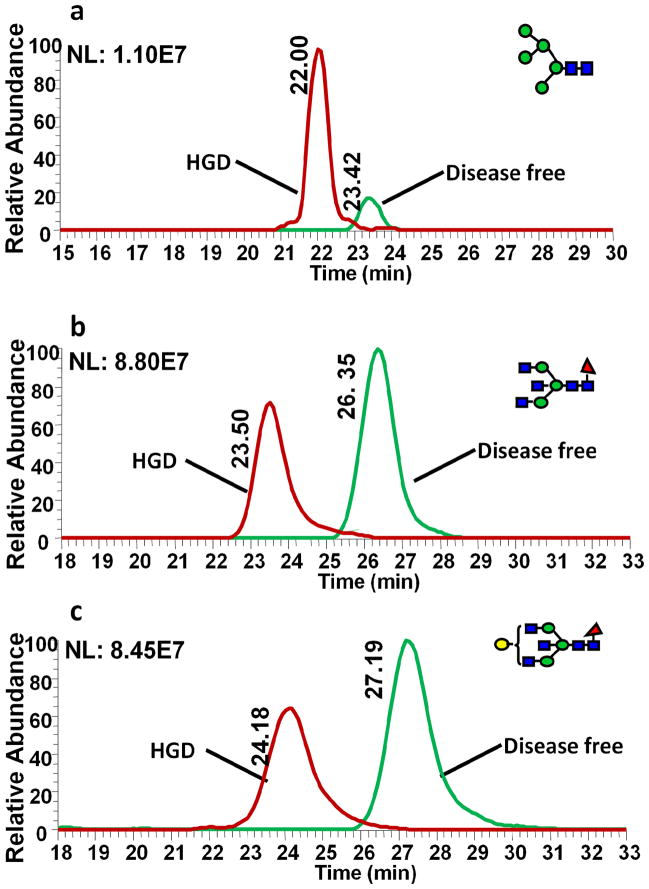

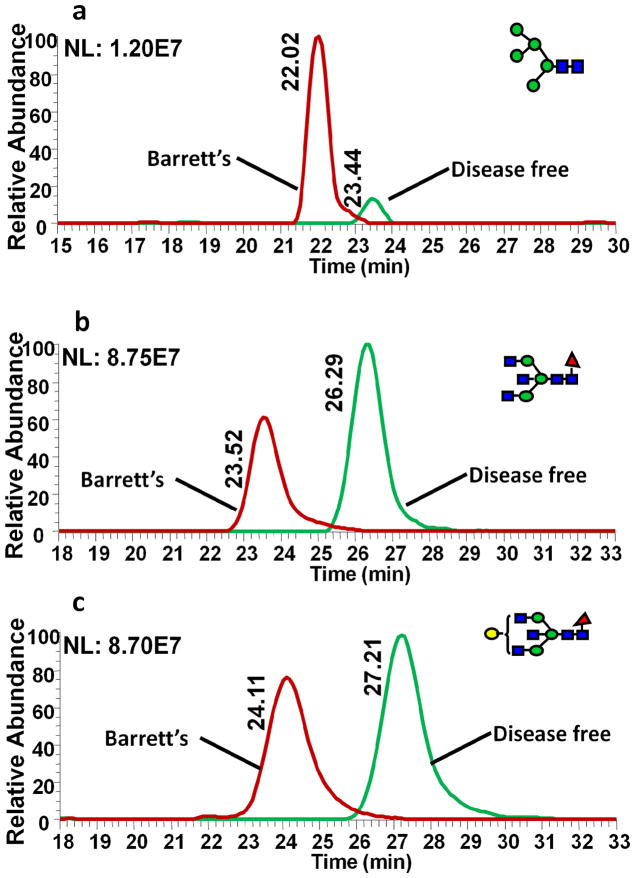

The comparative glycomic quantification strategy was employed to investigate differences in glycosylation patterns between esophageal disease samples and DF sample. Serum samples collected from different patients diagnosed with different esophageal diseases, (Barrett’s disease, HGD and esophageal adenocarcinoma) and sex- and age-matching DF samples were separately pooled. N-Glycans derived from the pooled esophageal disease samples were permethylated with “heavy” reagent while those from DF sample were “light” permethylated. Comparative glycomic LC-ESI-MS profiling was acquired with equal volume mixtures of disease sample and DF sample. The extracted ion chromatograms of three representative human blood serum N-glycans are depicted in Figures 4–6. The H/L ratios of N-glycan pairs for the same blood serum samples, but “light” and “heavy” permethylated were 1.05, 0.858 and 1.11 for H5N2 (Figure 4a), F1H3N5 (Figure 4b) and F1H4N5 (Figure 4c), respectively. These glycans should have depicted ratios of 1. The slight variation from the theoretical ratios may be due to the same above discussed reasons. Despite this fact, all pairs had an H/L ratio almost equal 1, indicating that a complex biological system does not influencecomparative LC-ESI-MS glycomic analysis. Meanwhile, the same structures derived from esophageal adenocarcinoma and DF samples depicted different peak ratios. The peak area ratios of H/L for the same glycans derived from cancer samples (“heavy” permethylated) and DF samples (“light” permethylated) were 1.52, 0.85, and 0.70 for H5N2 (Figure 4d), F1H3N5 (Figure 4e), and F1H4N5 (Figure 4f), respectively. In cancer samples, the intensity of Man 5 is significantly higher than that in DF HBS while that of bisecting fucosylated N-glycan is lower than that in DF HBS. The same N-glycans derived from Barrett’s samples were also compared to DF samples (Figure 5). The extracted ion chromatograms of the same glycans derived from Barrett’s disease and DF samples are shown in Figures 5a–c. The ratios were 4.14 for H5N2 (Figure 5a), 0.63 for F1H3N5 (Figure 5b) and 0.80 for F1H4N5 (Figure 5c). The H/L peak area ratios of the same glycans derived from HGD and DF were 3.25 for H5N2 (Figure 6a), 0.63 for F1H3N5 (Figure 6b) and 0.69 for F1H4N5 (Figure 6c). These results were in agreement with recently reported results [41]. Table 1 summarizes the changes of N-glycans in the cancer samples as well as other esophageal disease samples. Only the peaks with significant changes (0.8>H/L ratio>1.2) were listed in the table. For cancer samples, there were 40 compositions that were significantly different from the DF sample. 8 N-glycan compositions were over expressed. As for the Barrett’s sample, there were 31 compositions that were largely increased and 14 compositions that were decreased. In the case of HGD, 38 compositions were increased while 10 others were decreased. Accordingly, it appears that C-GlycoMAP of HBS by LC-ESI-MS is adequate to distinguish esophageal diseases from each other and from DF control.

Figure 4.

EIC of equal amounts of “heavy” and “light” permethylated (a) H5N2, (b) F1H3N5, and (c) F1H4N5 N-glycans derived from DF samples. The H/L peak area ratios were 1.05(a), 0.858(b), and 1.11(c). EIC of equal amounts of “heavy” and “light” permethylated (d) H5N2, (e) F1H3N5, and (f) F1H4N5 N-glycans derived from cancer and DF samples, respectively. N-glycans derived from cancer samples were permethylated with CH3I while N-glycans derived from DF samples were permethylated with CD3I. The H/L peak area ratio were 1.52 (d), 0.85 (e), and 0.70 (f). Symbols: as in Table 1.

Figure 6.

EIC of equal amounts of “heavy” and “light” permethylated (a) H5N2, (b) F1H3N5, and (c) F1H4N5 N-glycans derived from HGD and DF samples, respectively. N-glycans derived from HGD samples were permethylated with CH3I while N-glycans derived from DF samples were permethylated with CD3I. The H/L peak area ratio were 3.25 (a), 0.63 (b), and 0.69 (c). Symbols: as in Table 1.

Figure 5.

EIC of equal amounts of “heavy” and “light” permethylated (a) H5N2, (b) F1H3N5, and (c) F1H4N5 N-glycans derived from Barrett’s disease and DF samples, respectively. N-glycans derived from Barrett’s disease samples were permethylated with CH3I while N-glycans derived from DF samples were permethylated with CD3I. The H/L peak area ratio were 4.14 (a), 0.63 (b), and 0.8 (c). Symbols: as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intensities and Ratios of N-glycans derived from cancer, Barrett’s, HGD and DF HBS samples that have demonstrated significant changes in abundances (0.8>H/L>1.2).

| Structures | Disease free(L) | Cancer (H) | Ratio (H/L) | Disease free(L) | Barrett’s (H) | Ratio (H/L) | Disease free(L) | HGD (H) | Ratio (H/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4.57E+08 | 6.94E+08 | 1.52 | 1.25E+09 | 5.18E+09 | 4.14 | 1.33E+09 | 4.33E+09 | 3.25 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 1.01E+08 | 6.91E+07 | 0.68 | 1.26E+08 | 6.63E+07 | 0.53 |

|

4.78E+08 | 3.78E+08 | 0.79 | 5.25E+08 | 2.84E+08 | 0.54 | 5.61E+08 | 7.99E+08 | 1.42 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 3.56E+08 | 2.28E+09 | 0.64 | 3.63E+08 | 1.91E+09 | 5.26 |

|

1.81E+08 | 4.79E+07 | 0.26 | ------- | ------- | ------- | 4.93E+08 | 6.30E+08 | 1.28 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 1.14E+10 | 1.49E+10 | 1.30 | 2.20E+10 | 3.13E+10 | 1.42 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 6.32E+08 | 7.91E+08 | 1.25 | 9.38E+08 | 1.15E+09 | 1.23 |

|

1.18E+08 | 1.57E+08 | 1.33 | 6.77E+07 | 1.05E+09 | 15.5 | 7.72E+07 | 1.46E+09 | 18.9 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 2.75E+08 | 8.35E+08 | 3.03 | 2.22E+08 | 8.23E+08 | 3.70 |

|

9.79E+08 | 1.88E+08 | 0.19 | 6.22E+08 | 4.68E+08 | 0.75 | 8.23E+08 | 5.56E+08 | 0.68 |

|

1.72E+08 | 2.89E+07 | 1.68 | 2.12E+08 | 2.82E+08 | 1.33 | ------- | ------- | ------- |

|

4.92E+08 | 3.43E+08 | 0.69 | 4.21E+08 | 8.95E+08 | 2.12 | 4.35E+08 | 8.81E+08 | 2.02 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 5.75E+09 | 3.64E+09 | 0.63 | 5.92E+09 | 4.14E+09 | 0.69 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 3.42E+08 | 1.51E+09 | 4.44 | 3.23E+08 | 1.43E+09 | 4.43 |

|

7.14E+08 | 3.71E+08 | 0.52 | 5.95E+08 | 1.44E+09 | 2.42 | 5.32E+08 | 9.81E+08 | 1.84 |

|

4.26E+09 | 6.80E+08 | 1.60 | 4.14E+09 | 1.50E+09 | 0.36 | 4.12E+09 | 5.87E+09 | 1.42 |

|

5.35E+08 | 2.22E+09 | 0.41 | 3.58E+08 | 3.36E+09 | 9.39 | 3.35E+08 | 3.39E+09 | 0.10 |

|

9.44E+09 | 7.13E+09 | 0.76 | 6.77E+09 | 9.88E+09 | 1.46 | 7.04E+09 | 7.43E+09 | 1.06 |

|

|

8.99E+09 | 6.25E+09 | 0.70 | ------- | ------- | ------- | 7.87E+09 | 5.44E+09 | 0.69 |

|

1.77E+08 | 5.38E+07 | 0.30 | 1.31E+08 | 6.60E+08 | 5.03 | 1.55E+08 | 5.16E+08 | 3.32 |

|

1.31E+10 | 7.39E+09 | 0.56 | 1.21E+10 | 1.53E+10 | 1.26 | ------- | ------- | ------- |

|

1.81E+10 | 1.43E+10 | 0.79 | 1.35E+10 | 3.39E+10 | 2.51 | 1.40E+10 | 2.95E+10 | 2.10 |

|

4.82E+09 | 3.44E+09 | 0.71 | 3.17E+09 | 8.20E+09 | 2.59 | 3.21E+09 | 8.01E+09 | 2.50 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | 5.92E+07 | 4.28E+08 | 7.23 |

|

2.07E+09 | 1.24E+09 | 0.60 | 1.89E+09 | 3.48E+09 | 1.84 | 1.89E+09 | 2.34E+09 | 1.23 |

|

|

1.52E+10 | 8.88E+09 | 0.58 | ------- | ------- | ------- | 1.29E+09 | 4.96E+09 | 3.84 |

|

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 1.26E+09 | 3.48E+09 | 2.76 | 1.24E+09 | 3.67E+09 | 2.96 |

|

9.38E+08 | 3.64E+08 | 0.39 | 7.84E+08 | 4.69E+09 | 0.60 | 7.93E+08 | 3.18E+09 | 4.01 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | 9.79E+07 | 4.07E+08 | 4.16 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 1.28E+11 | 1.62E+11 | 1.27 | 1.40E+11 | 1.98E+11 | 1.41 |

|

3.15E+10 | 2.12E+10 | 0.67 | ------- | ------- | ------- | 2.99E+10 | 3.69E+10 | 1.23 |

|

|

1.27E+10 | 5.23E+09 | 0.41 | 1.20E+10 | 2.06E+10 | 1.72 | 1.30E+10 | 1.53E+10 | 1.18 |

|

4.77E+09 | 1.29E+09 | 0.27 | 4.52E+09 | 1.95E+09 | 0.43 | 5.21E+09 | 2.51E+09 | 0.48 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 1.03E+09 | 2.30E+09 | 2.23 | 8.33E+08 | 2.32E+09 | 2.79 |

|

4.72E+10 | 2.48E+10 | 0.53 | 3.51E+10 | 4.30E+10 | 1.23 | ------- | ------- | ------- |

|

9.09E+08 | 4.60E+08 | 0.51 | 7.07E+08 | 9.78E+08 | 1.38 | 8.27E+08 | 1.15E+09 | 1.39 |

|

1.12E+09 | 1.56E+08 | 0.14 | 8.72E+08 | 3.97E+08 | 0.46 | ------- | ------- | ------- |

|

|

2.97E+10 | 2.36E+10 | 0.79 | 2.39E+10 | 4.13E+10 | 1.73 | 3.04E+10 | 3.93E+10 | 1.29 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 8.10E+09 | 1.17E+10 | 1.44 | 1.01E+10 | 1.32E+10 | 1.31 |

|

5.86E+09 | 4.30E+09 | 0.73 | 4.26E+10 | 4.65E+09 | 0.10 | ------- | ------- | ------- |

|

1.81E+09 | 8.55E+07 | 0.05 | 1.34E+09 | 6.48E+08 | 0.48 | 1.67E+09 | 4.24E+08 | 0.25 |

|

6.32E+10 | 1.84E+10 | 0.29 | 3.39E+10 | 4.58E+10 | 1.35 | ------- | ------- | ------- |

|

2.12E+09 | 1.05E+08 | 0.05 | 1.78E+09 | 5.27E+08 | 0.30 | 1.65E+09 | 1.68E+09 | 1.01 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | 4.51E+08 | 2.77E+08 | 0.61 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 3.39E+10 | 4.58E+10 | 1.35 | 2.31E+10 | 5.64E+10 | 2.44 |

|

3.03E+09 | 3.88E+09 | 1.28 | 2.33E+09 | 7.19E+09 | 3.09 | 2.68E+09 | 8.08E+09 | 3.01 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 1.73E+09 | 8.17E+08 | 0.47 | 4.47E+08 | 9.41E+08 | 2.10 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | 1.39E+09 | 4.00E+09 | 2.88 | 1.71E+09 | 4.34E+09 | 2.53 |

|

5.64E+09 | 2.91E+09 | 0.51 | 4.53E+09 | 2.92E+09 | 0.64 | 5.58E+09 | 7.23E+09 | 1.29 |

|

2.20E+10 | 2.30E+09 | 0.10 | ------- | ------- | ------- | 1.16E+10 | 5.93E+09 | 0.51 |

|

2.02E+09 | 1.54E+09 | 0.76 | 1.05E+09 | 2.32E+09 | 2.20 | 2.73E+08 | 5.80E+09 | 21.2 |

|

1.07E+10 | 6.47E+09 | 0.60 | ------- | ------- | ------- | 6.44E+09 | 2.31E+10 | 3.58 |

|

8.55E+08 | 6.89E+07 | 0.81 | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- |

|

5.40E+09 | 7.17E+09 | 1.32 | 4.56E+09 | 2.18E+10 | 4.78 | 5.13E+09 | 2.14E+10 | 4.17 |

|

------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- | 4.62E+08 | 1.87E+08 | 0.40 |

|

9.33E+08 | 2.96E+09 | 3.17 | 1.30E+09 | 4.16E+09 | 3.20 | 9.26E+08 | 3.09E+09 | 3.34 |

|

1.10E+08 | 5.71E+08 | 5.42 | 1.66E+08 | 3.07E+09 | 18.49 | 1.94E+08 | 1.79E+09 | 9.22 |

|

4.95E+07 | 1.14E+07 | 0.23 | 5.37E+07 | 7.90E+08 | 14.70 | 9.02E+07 | 8.44E+08 | 9.35 |

Symbols:Fucose

; N-acetyl glucosamine

; N-acetyl glucosamine

; mannose

; mannose

; galactose

; galactose

; sialic acid

; sialic acid

Glycans structures designated with asterisks were identified through tandemMS and mass accuracy (<1).

Glycan structures without asterisks were only identified through mass accuracy (<1)

Conclusion

Combining permethylation and isotopic labeling allows the simultaneous quantification of N-glycans in comparative glycomic studies. N-Glycans derived from model glycoproteins and human blood serum demonstrated effective glycan quantification using “heavy” and “light” permethylation of glycans. LC-ESI-MS results indicated that this strategy is reliable for quantitative glycomic analysis of glycans derived from different samples. Comparative glycomic profiling of N-glycans derived from esophageal disease and DF samples illustrated the potential of using this strategy to detect disease states. The comparative glycomic profiling strategy described here may be utilized to monitor glycomic changes associated with the development and progression of diseases. The strategy could be also employed to monitor any glycomic changes resulting from drug treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Texas Tech University, and partially by the National Institute of Health (NIH-5R01GM93322-2). Human blood serum samples collected from patients with esophageal diseases, and their matching controls were kindly provided by Dr. Zane Hammoud of Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI.

References

- 1.Apweiler R, Hermjakob H, Sharon N. On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochim Biophys Acta: Gen Subjects. 1999;1473:4–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart GW, Copeland RJ. Glycomics Hits the Big Time. Cell. 2010;143:672–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dube DHCR. Bertozzi, Glycans in cancer and inflammation — potential for therapeutics and diagnostics. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2005;4:477–488. doi: 10.1038/nrd1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudd PM, Elliott T, Cresswell P, Wilson IA, Dwek RA. Glycosylation and the Immune System. Science. 2001;291:2370–2376. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennis JW, Granovsky M, Warren CE. Protein glycosylation in development and disease. Bioassays. 1999;21:412–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199905)21:5<412::AID-BIES8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis JW, Laferte S, Waghorne C, Breitman ML, Kerbel RS. β1–6 branching of Asn-linked oligosaccharides is directly associated with metastasis. Science. 1987;236:582–585. doi: 10.1126/science.2953071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakomori S. Tumor malignancy defined by aberrant glycosylation and sphingo(glyco)-lipid metabolism. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5309–5318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakomori S. Glycosylation defining cancer malignancy: New wine in an old bottle. Proc Nat Acad Sci US A. 2002;16:10232–10233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172380699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dwek MV, Lacey HA, Leathem AJC. Breast cancer progression is associated with a reduction in the diversity of sialylated and neutral oligosaccharides. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;271:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(97)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwek RA. Glycobiology: Toward Understanding the Function of Sugars. Chem Rev. 1996;96:683–720. doi: 10.1021/cr940283b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alley WR, Novotny MV. Glycomic Analysis of Sialic Acid Linkages in Glycans Derived from Blood Serum Glycoproteins. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:3062–3072. doi: 10.1021/pr901210r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An HJ, Kronewitter SR, de Leoz MLA, Lebrilla CB. Glycomics and Disease Markers. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An HJ, Miyamoto S, Lancaster KS, Kirmiz C, Li B, Lam KS, Leiserowitz GS, Lebrilla CB. Profiling of Glycans in Serum for the Discovery of Potential Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancer. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1626–1635. doi: 10.1021/pr060010k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brockhausen I, Yang JM, Burchell J, Whitehouse C, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Mechanism underlying aberrant glycosylation of MUC1 mucin in breast cancer cells. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:607–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.607_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson B, Gotlieb WH, Ben-Baruch G, Kopolovic J, Goldberg I, Nesland JM, Berner A, Bjamer A, Bryne M. Expression of carbohydrate antigens in advanced-stage ovarian carcinomas and their metastases-A clinicopathologic study. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77:35–43. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Leoz MLA, An HJ, Kronewitter S, Kim J, Beecroft S, Vinall R, Miyamoto S, De Vere White R, Lam KS, Lebrilla CB. Glycomic approach for potential biomarkers on prostate cancer: Profiling of N-linked glycans in human sera and pRNS cell lines. Disease Markers. 2008;25:243–258. doi: 10.1155/2008/515318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goetz JA, Mechref Y, Kang P, Jeng MH, Novotny MV. Glycomic profiling of invasive and non-invasive breast cancer cells. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:117–131. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman R, Ressom HW, Varghese RS, Goldman L, Bascug G, Loffredo CA, Abdel-Hamid M, Gouda I, Ezzat S, Kyselova Z, Mechref Y, Novotny MV. Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Glycomic Analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1808–1813. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isailovic D, Kurulugama RT, Plasencia MD, Stokes ST, Kyselova Z, Goldman R, Mechref Y, Novotny MV, Clemmer DE. Profiling of Human Serum Glycans Associated with Liver Cancer and Cirrhosis by IMS-MS. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1100–1117. doi: 10.1021/pr700702r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyselova Z, Mechref Y, Al Bataineh MM, Dobrolecki LE, Hickey RJ, Vinson J, Sweeney CJ, Novotny MV. Alterations in the Serum Glycome Due to Metastatic Prostate Cancer. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1822–1832. doi: 10.1021/pr060664t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyselova Z, Mechref Y, Kang P, Goetz JA, Dobrolecki LE, Sledge G, Schnaper L, Hickey RJ, Malkas LH, Novotny MV. Breast cancer diagnosis/prognosis through quantitative measurements of serum glycan profiles. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1166–1175. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.087148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mechref Y, Hussein A, Bekesova S, Pungpapong V, Zhang M, Dobrolecki LE, Hickey RJ, Hammoud ZT, Novotny MV. Quantitative Serum Glycomics of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Other Esophageal Disease Onsets. Journal of Proteome Research. 2009;8:2656–2666. doi: 10.1021/pr8008385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao J, Patwa TH, Qiu W, Shedden K, Hinderer R, Misek DE, Anderson MA, Simeone DM, Lubman DM. Glycoprotein Microarrays with Multi-Lectin Detection: Unique Lectin Binding Patterns as a Tool for Classifying Normal, Chronic Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer Sera. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1864–1874. doi: 10.1021/pr070062p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mechref Y, Hu Y, Garcia A, Hussien A. Disease Biomarkers through Mass Spectrometry Based Glycomics. Electrophoresis. 2012;33:1755–1767. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlando R, Lim JM, Atwood JA, Angel PM, Fang M, Aoki K, Alvarez-Manilla G, Moremen KW, York WS, Tiemeyer M, Pierce M, Dalton S, Wells L. IDAWG: Metabolic incorporation of stable isotope labels for quantitative glycomics of cultured cells. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3816–3823. doi: 10.1021/pr8010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowman MJ, Zaia J. Tags for the stable isotopic labeling of carbohydrates and quantitative analysis by mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2007;79:5777–5784. doi: 10.1021/ac070581b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prien JM, Prater BD, Qin Q, Cockrill SL. Mass spectrometric-based stable isotopic 2-aminobenzoic acid glycan mapping for rapid glycan screening of biotherapeutics. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1498–1508. doi: 10.1021/ac902617t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker SH, Budhathoki-Uprety J, Novak BM, Muddiman DC. Glycoprotein analysis using mass spectrometry: unraveling the layers of complexity. Anal Chem. 2011;83:6738–6745. doi: 10.1021/ac201376q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia B, Feasley CL, Sachdev GP, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Glycan reductive isotope labeling for quantitative glycomics. 2009;387:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orlando R, Lim J, Atwood JA, Angel PM, Fang M, Kazuhiro A, Alvarez-Manilla G, Moreman KW, York WS, Tiemeyer M, Pierce M, Dalton S, Wells L. IDAWG: Metabolic incorporation of stable isotope labels for quantitative glycomics of cultured cells. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3816–3823. doi: 10.1021/pr8010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang P, Mechref Y, Kyselova Z, Goetz JA, Novotny MV. Comparative glycomic mapping through quantitative permethylation and stable-isotope labeling. Anal Chem. 2007;79:6064–6073. doi: 10.1021/ac062098r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan J, Hashii N, Kawasaki N, Itoh S, Kawanishi T, Hayakawa T. Isotope tag method for quantitative analysis of carbohydrates by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1067:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hitchcock AM, Costello CE, Zaia J. Glycoform quantification of chondroitin/dermatan sulfate using a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry platform. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2350–2361. doi: 10.1021/bi052100t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desantos-Garcia JL, Khalil SI, Hussein A, Hu Y, Mechref Y. Enhanced sensitivity of LC-MS analysis of permethylated N-glycans through online purification. Electrophoresis. 2011;32:3516–3525. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu Y, Mechref Y. Comparing MALDI-MS, RP-LC-MALDI-MS and RP-LC-ESI-MS glycomic profiles of permethylated N-glycans derived from model glycoproteins and human blood serum. Electrophoresis. 2012;33:1768–1777. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang P, Mechref Y, Novotny MV. High-throughput solid-phase permethylation of glycans prior to mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:721–734. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mechref Y, Kang P, Novotny MV. Solid-phase permethylation for glycomic analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;534:53–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-022-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isailovic D, Kurulugama RT, Plasencia MD, Stokes ST, Kyselova Z, Goldman R, Mechref Y, Novotny MV, Clemmer DE. Profiling of Human Serum Glycans Associated with Liver Cancer and Cirrhosis by IMS MS. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1109–1117. doi: 10.1021/pr700702r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kyselova Z, Mechref Y, Al Bataineh MM, Dobrolecki LE, Hickey RJ, Vinson J, Sweeney CJ, Novotny MV. Alterations in the Serum Glycome Due to Metastatic Prostate Cancer. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1822–1832. doi: 10.1021/pr060664t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mechref Y, Hussein A, Bekesova S, Pungpapong V, Zhang M, Dobrolecki LE, Hickey RJ, Hammoud ZT, Novotny MV. Quantitative serum glycomics of esophageal adenocarcinoma and other esophageal disease onsets. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:2656–2666. doi: 10.1021/pr8008385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang P, Mechref Y, Klouckova I, Novotny MV. Solid-phase permethylation of glycans for mass spectrometric analysis. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:3421–3428. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.