Abstract

Experimental control over progenitor cell lineage specification can be achieved by modulating properties of the cell's microenvironment. These include physical properties of the cell adhesion substrate, such as rigidity, topography and deformation owing to dynamic mechanical forces. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) generate contractile forces to sense and remodel their extracellular microenvironments and thereby obtain information that directs broad aspects of MSC function, including lineage specification. Various physical factors are important regulators of MSC function, but improved understanding of MSC mechanobiology requires novel experimental platforms. Engineers are bridging this gap by developing tools to control mechanical factors with improved precision and throughput, thereby enabling biological investigation of mechanics-driven MSC function. In this review, we introduce MSC mechanobiology and review emerging cell culture platforms that enable new insights into mechanobiological control of MSCs. Our main goals are to provide engineers and microtechnology developers with an up-to-date description of MSC mechanobiology that is relevant to the design of experimental platforms and to introduce biologists to these emerging platforms.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cell, mechanobiology, microtechnology, microfluidics, niche, high-throughput screening

1. Introduction

Biological tissues contain populations of variously specialized cells with phenotypes that are tightly regulated according to their roles in tissue homeostasis. These include progenitor cells that have potential for self-renewal and multilineage differentiation and play important roles during tissue formation and repair. Balance between quiescence and activation/specialization of these cells is maintained by signalling that occurs in the cellular microenvironment, the collective properties of which are referred to as the cell niche [1]. Several recent reviews describe particular cell niches, for example in bone [2], bone marrow [3] and muscle [4]. Current understanding is that multiple microenvironmental cues within and between in vivo niches combine to govern progenitor cell proliferation, migration and differentiation (i.e. cell ‘fate’), but the mechanisms are not fully understood [5]. Systematic study of these mechanisms has been hampered by the combinatorial nature of multiple non-additive cues and by limited accessibility of in vivo niches.

Among the microenvironmental stimuli that govern cell fate and function, mechanical factors have emerged as key determinants. Mechanical factors that affect cell fate include rigidity and topology of the extracellular matrix (ECM) or adhesion substrate, deformation of cells and tissues that results from mechanical loading, and shear stresses associated with fluid flow. In load-bearing connective and cardiovascular tissues, in particular, the beneficial effects of mechanical loading on the maintenance of healthy tissues are generally accepted [6]. Connective tissues contain multipotent mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) that have at minimum osteogenic, chondrogenic and adipogenic lineage potential [7] and play important roles in homeostasis. Similarly, MSC-like cells are present in blood vessels [8] and heart valves [9] where they probably participate in tissue renewal, but also can differentiate to ectopic phenotypes that contribute to disease [10]. Lineage specification of MSCs from multiple sources depends on substrate rigidity [11,12], cell–substrate adhesion geometry [13–15] and dynamic mechanical forces that, for example, promote osteogenesis at the expense of adipogenesis to mirror tissue-level bone strengthening and fat suppression with exercise [16,17]. An integrated multiscale approach is required to describe the mechanisms by which mechanics regulate MSCs and contribute to tissue-level remodelling and repair.

As with other progenitors, MSC populations are heterogeneous, they vary between donors [18], and extended monolayer culture results in heterogeneous morphologies associated with various subpopulations [19]. MSC-like cells are found in increasing numbers of differing tissue sources, compounding difficulties associated with classification schemes [20]. The rarity and sensitivity of MSCs to various stimulants (e.g. mechanical), combined with the minimal accessibility of in vivo niches motivates the development of ex vivo experimental platforms that recapitulate key properties of in vivo niches, screen the effects of multiple factors that regulate cell fate and address MSC heterogeneity by analysing sufficient numbers of cells on an individual basis.

In this review, we describe MSC mechanobiology in the context of lineage specification through mechanical interactions with substrates and ECM materials, and we highlight emerging ex vivo experimental mechanobiology platforms. We begin with an introductory-level description of MSC mechanobiology with a focus on cell-based contractility and substrate rigidity sensing. We then summarize key experimental demonstrations of mechanically regulated MSC lineage specification in two- and three-dimensional culture platforms. We conclude by describing platforms that mimic in vivo niches and address MSC heterogeneity.

2. Mechanobiology of mesenchymal stem cells

Cell behaviour results from a delicate interplay of inhibitory and stimulatory molecular signalling pathways, and the relationships between interacting molecules must be carefully delineated to understand their collective influence on cell fate. Here, we focus on observed MSC fate regulation that occurs through ECM, integrin and cell cytoskeleton (CSK) interactions. Cells sense the rigidity of their supporting substrates by exerting contractile forces through adhesion complexes that link intracellular structures to the extracellular environment. Adhesion proteins such as integrins link the ECM to the force-generating CSK and associated molecular transduction events/cascades are variously activated based on binding affinities and stresses that are generated during contraction [21].

2.1. Focal adhesions and force generation by the actin cytoskeleton

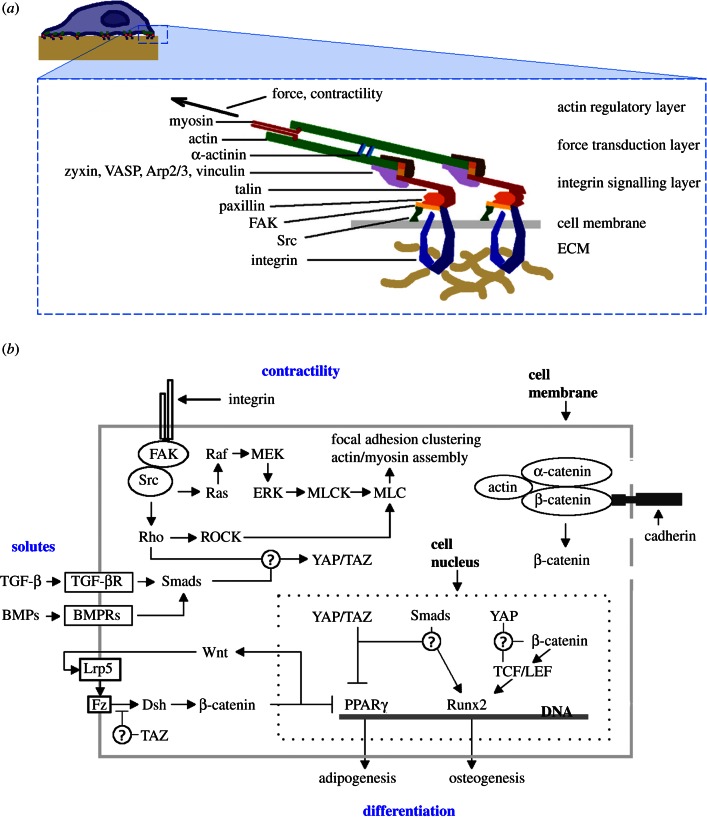

The integrin adhesome consists of approximately 160 distinct components that interact with approximately 500 additional molecules, roughly half of which are binding interactions [22]. Approximately 20 integrin homologues have been identified in human cells, each having specific binding affinities for various types of collagen, fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin and other ECM proteins [23]. A schematic of the integrin complex and several related signalling pathways that feature prominently in MSC mechanobiology is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the integrin focal adhesion complex and contractile signalling. (a) Molecules that link the extracellular matrix (ECM) with the cell's internal cytoskeleton, adapted from [24] with permission from Elsevier and [25] with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd (Copyright 2010); (b) a simplified model of signalling pathways that are implicated in contractility-based mechanosensing and MSC differentiation, after [26] and [27]. TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; TGF-βR, transforming growth factor β receptor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; BMPR, bone morphogenetic protein receptor; Smad, small mothers against decapentaplegic proteins; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; Src, Rous sarcoma oncogene cellular homolog; Rho, Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors; ROCK, Rho-associated kinase; Ras, Ras small GTPases; Raf, Raf serine/threonine-protein kinase; MEK, MAPK/Erk kinase; MAPK/ERK, mitogen-activated protein kinases/extracellular signal-regulated kinases; MLCK, myosin light-chain kinase; MLC, myosin light chain; Lrp5, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5; Fz, frizzled G protein-coupled receptor protein; Dsh, dishevelled protein; YAP, Yes-associated protein; TAZ, transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif; Runx2, Runt-related transcription factor 2; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

Although greatly simplified, this schematic provides a context in which the molecules described below are shown to influence MSC fate through contractility-based mechanisms. As with other transmembrane molecules, integrins can move laterally in the plane of the membrane and often cluster into specialized complexes known as focal adhesion sites that assure cell–substrate adhesion and are important mechanical signalling centres. Focal adhesions are dynamic structures that bind the ECM, providing physical links to the cell's contractile architecture (i.e. the CSK), and assemble in response to substrate properties such as rigidity and topography. Components of typical integrins that are shown in figure 1a are described in detail in [24,25,28], and a list of integrin subunits detected in human MSCs is summarized in Docheva et al. [23]. The mammalian cell CSK contains several distinct interacting molecular networks that include intermediate filaments, microtubules and actin-based microfilaments; the biomechanical roles of each have recently been reviewed in [29–31], respectively. Actin is a primary component of contractile structures that include striated muscle tissue in skeletal muscles, non-striated muscle tissue in smooth muscles and non-muscle contractile structures called stress fibres that are found in diverse cell types. Stress fibres are composed of filamentous F-actin bundles held together by actin-cross-linking proteins such as α-actinin that are interspersed with non-muscle myosin and tropomyosin [32]. Each actin bundle typically contains 10–30 filaments and can generate contractile forces on the order of 100 pN; their rupture force is approximately 370 nN, approximately 100-fold larger than the typical force exerted at a cellular adhesion site [31]. Stress fibres terminate on focal adhesions forming a mechanoresponsive network that transfers forces generated by actin polymerization and myosin II-dependent contractility to focal adhesion receptor proteins (e.g. integrins; [22]). Stress fibre contraction is dually regulated by a Ca2+-dependent calmodulin/myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) system and a Ca2+-independent Ras homology (Rho)-kinase system through MLC phosphorylation [33]. Stress fibre and focal adhesion synthesis and organization are regulated to balance cell-generated forces with ECM mechanical properties and external forces.

2.2. Molecules linking mesenchymal stem cell contractility with lineage specification

Drugs that disrupt CSK structures demonstrate that CSK tension and contractile forces are essential for mechanical regulation of MSC fate in a variety of contexts. For example, cytochalasin D is a small molecule that inhibits F-actin polymerization, blebbistatin inhibits myosin II and Y-27632 inhibits the Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK). These drugs reduce CSK contractility and thereby reduce substrate geometry-directed MSC osteogenesis in favour of adipogenesis [15]. Inhibition of non-muscle myosin II with blebbistatin blocked substrate elasticity-directed lineage specification [11], and an intact actin CSK under tension appears to be necessary for oscillatory fluid-flow-induced MSC differentiation [34]. These studies suggest that MSC lineage specification by substrate geometry and elasticity, and fluid-flow-based mechanical stimulation share a common dependence on MSC focal adhesion assembly and CSK contractility.

MSC maturation through specific lineages requires time-dependent modulation of proliferation, matrix maturation and in some cases (e.g. during osteogenesis) mineralization [35], all of which are regulated by MSC–ECM interactions that involve signalling molecules such as those shown in figure 1. For example, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a cytoplasmic protein–tyrosine kinase involved in CSK remodelling, formation and disassembly of cell adhesion structures, and regulation of Rho-family GTPases [36]. When MSCs were cultured in osteogenic medium on multiple substrates with differing rigidities, increased ROCK, FAK and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) activities were observed on stiffer matrices (Young's modulus, E approx. 40 kPa, mimicking pre-calcified bone, compared with E ∼ 7 kPa mimicking fat) and inhibition of FAK or ROCK decreased the expression of osteogenic markers [37]. Matrix proteins such as collagen I and vitronectin support MSC osteogenesis by a process thought to involve ERKs [38], and the ability to reorganize collagen in three dimensions is an important step in ERK-mediated osteogenic differentiation [39]. Using blocking antibodies to integrin β1- and ανβ3-subunits, ECM-induced ERK activation was inhibited and addition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor PD98059 blocked ERK activation, serine phosphorylation of the osteogenic transcription factor Runx2, osteogenic gene expression and calcium deposition, suggesting that ERK plays an important role in driving ECM-induced osteogenic differentiation of MSCs [38]. The ability of MSCs to form a mineralized matrix was also diminished in the presence of antibodies that blocked the integrin subunit β1 [40], and integrin-β1 was localized to the cell surface when MSCs were cultured on stiff substrates (Young's modulus, E ∼ 50–100 kPa) in contrast to cytoplasmic distributions observed on soft substrates (E ∼ 0.1–1 kPa) [41]. Park et al. [42] showed that soft matrices (E ∼ 1 kPa) favouring MSC chondrogenesis in low-serum medium did not significantly affect Rho activity but inhibited Rho-induced stress fibre formation and α-actin assembly. They found that MSC spreading, stress fibre density and α-actin assembly into stress fibres depended on substrate stiffness. Addition of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) increased chondrogenic marker expression and suppressed adipogenic marker expression on soft substrates. Similarly, Kwon [43] observed high mRNA levels of chondrogenic markers such as Col2a1, Agc and Sox9 in MSCs cultured on soft matrices (E ∼ 1 kPa) in the absence of differentiation supplements, concomitant with reduced stress fibres compared with MSCs cultured on stiffer gels (E ∼ 150 kPa).

The results summarized earlier clearly demonstrate that MSC lineage specification is regulated by focal adhesion clustering, integrin–ECM interactions and actin/myosin contractility. Further studies are required to assess the relative importance and potential synergy of Rho and ERK pathways and their interactions with developmental pathways and transcriptional regulation. Growing evidence that we discuss below is beginning to reveal interactions between the focal adhesion and contractile systems, cell–cell adhesion proteins (e.g. catenins), soluble factors that control proliferation and differentiation (e.g. TGF-β class of regulatory proteins), and transcription factors associated with cell and tissue development (e.g. the Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ)).

Cells convert mechanical forces into molecular signals, and mechanobiology must account for a growing number of interacting signalling pathways. In figure 1, we included circled question marks that connect multiple signalling pathways where further studies of potential interactions are particularly relevant to MSC mechanobiology. Here, we briefly summarize the roles of several key signalling systems: TGF-β/small mothers against decapentaplegic (smad), YAP/TAZ and Wnt. The TGF-β class of regulatory proteins act through the canonical smad signalling pathway and play key roles in cell and tissue development [44]. TGF-β is variously activated by different integrins [45], and soluble TGF-β increases integrin expression in MSCs, thereby enhancing attachment to type I collagen, which is part of the ECM in bone, skin and connective tissues [46]. Chondroinductive effects of the TGF-β superfamily members are well established in MSCs [47], and recent work is beginning to establish a global role of TGF-β signalling in the regulation of stem cell fate [48]. Upon activation, several molecules associated with MSC lineage specification undergo nuclear translocation where they influence gene transcription. These include smads, YAP/TAZ and β-catenin of the canonical Wnt signalling pathway. YAP and TAZ interact with TGF-β/smad signalling [49–52] and influence MSC differentiation through BMP2 and Runx2 osteogenic paths [53]. Runx2 is an essential transcription factor for osteoblast differentiation and chondrocyte maturation [54]; TAZ binds to Runx2 and to the transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARγ), the relative activation of Runx2 and PPARγ determine MSC osteogenic or adipogenic tendencies and MSCs depleted of TAZ show increased adipogenesis at the expense of osteogenesis [53]. Wnt signalling and β-catenin nuclear translocation regulate MSC proliferation and differentiation [55], interact with TAZ [56] and are increasingly studied in the context of MSC mechanobiology [57–59]. Downregulation of nuclear β-catenin coincides with the induction of the adipogenic transcription factors [60], and β-catenin signalling therefore mediates inhibition of MSC adipogenesis resulting from applied mechanical strain [58]. Furthermore, fluid flow weakens N-cadherin association with β-catenin enabling β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus and initiate gene transcription [34]. MSC lineage specification clearly involves diverse signalling pathways associated with mechanosensing and contractility, cell–cell adhesion and development. The large numbers of potential interactions between components of signalling pathways that govern MSC mechanobiology underscore the advantages of experimental platforms that have a high screening throughput.

3. Emerging experimental platforms for multipotent mesenchymal stem cell mechanobiology

Niche properties that regulate cell fate include soluble biochemical factors, ECM biochemistry, substrate mechanics (e.g. rigidity and topology) and mechanical loading; combinatorial screening is required to determine their isolated and combined effects on MSC fate. Many of these cues are dynamically altered by cells, for example through autocrine and paracrine signalling or by ECM synthesis and remodelling. Limited access to in vivo tissue microenvironments and the large number of interacting cues that are present in living systems motivate the development of physiologically relevant high-throughput screening (HTS) platforms for MSC mechanobiology. HTS platforms that include multi-well culture plates and associated robotic handling equipment are essential tools for genetics, combinatorial chemistry and toxicology (drug screening) [61]. Adapting these platforms for mechanobiology will require increased biomimicry, including fluid flow, three-dimensional culture and dynamic mechanical loading.

Biological tissues are regularly subjected to a variety of dynamic mechanical forces that include hydrostatic compression, fluid shear and mechanical bending, tension and compression, often in combination. A large number of experimental platforms have been developed to study mechanical modulation of cell and tissue fate [62], but the majority of these platforms are limited to serial sample testing and therefore mimic mechanically dynamic physiologies or pathologies at the expense of experimental throughput. Because cells and tissues experience a wide variety of mechanical forces that interact with non-mechanical (e.g. biochemical) factors, low experimental throughput hampers systematic mechanobiology research. To achieve HTS, emerging experimental platforms are typically miniaturized [63–65] and fabricated using soft lithography to handle aqueous solutions in microfluidic channels [66]. Advantages of these microfabricated ‘laboratory-on-a-chip’ platforms include reduced footprint and increased experimental throughput, reduced cost and increased automation. These advantages are clearly important for mechanobiology experiments that aim to decouple the effects of multiple interacting stimulants such as cell sources, ECM properties, soluble factors and mechanical forces.

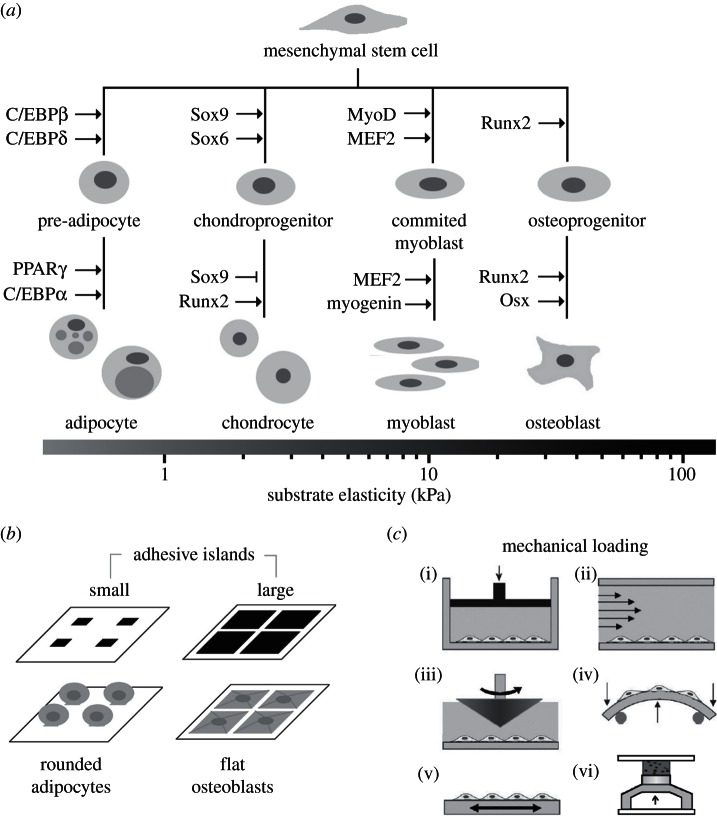

In figure 2a, we show several transcription factors that are required to direct MSC lineage specification and we include a substrate elasticity scale bar to indicate elasticity values that are associated with substrate elasticity-directed MSC lineage specification [11]. Cell culture substrate properties are excellent experimental variables that provide key insights into MSC mechanobiology. Historically, these have been achieved by varying substrate elasticity [69–71] or adhesive properties that direct cell shape (figure 2b) [13,15,72]; both methods are well suited for miniaturized array-based HTS platforms. Dynamic mechanical loading (figure 2c) is often more challenging to implement than mechanically static cultures but is nevertheless increasingly represented in microfabricated platforms [59,73–76].

Figure 2.

Substrate mechanics and dynamic mechanical loading regulate mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) fate. (a) Transcriptional regulation of well-characterized MSC lineages and associated substrate elasticity values that enhance MSC lineage specification. MSC differentiation towards particular lineages is enhanced by substrates with elasticity that are similar to native tissues, adapted from [5] with permission from AAAS and [67] with permission from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; (b) adhesive ligand patterning regulates MSC shape and lineage specification. Differing cell–substrate contact areas are controlled by patterned islands of adhesive proteins to control cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and differentiation; (c) methods used to apply dynamic mechanical forces to cell and tissue cultures: (i) hydrostatic pressure, (ii, iii) flow-induced shear stress, (iv) bending, (v) tension and (vi) compression, adapted from [68] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Here, we describe recent MSC mechanobiology research enabled by emerging experimental platforms (broadly summarized in table 1). We highlight methods that are used to: (i) screen the effects of two-dimensional culture substrate properties on MSC lineage specification; (ii) measure cell-generated traction forces and MSC lineage specification in three-dimensional cultures; (iii) apply dynamic mechanical forces to cultured cells; (iv) increase biomimicry in cell and tissue culture platforms; and (v) address issues of MSC heterogeneity via single cell manipulation and characterization.

Table 1.

Summary of mechanobiology platform capabilities. 2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional.

| methods | applications | advantages | disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D protein patterning | cell–matrix interactions, focal adhesion assembly | ease of use and visualization, high experimental throughput | 2D systems may not accurately represent cell behaviour in 3D |

| 2D substrate elasticity | cell–substrate mechanical interactions, stem cell lineage specification | ease of use and visualization, high experimental throughput | 2D systems may not accurately represent cell behaviour in 3D, additional substrate properties (e.g. biochemistry, porosity) can confound interpretation |

| 2D substrate topography | contact guidance, stem cell lineage specification, maintenance of stem cell quiescence | ease of use and visualization, high experimental throughput | 2D systems may not accurately represent cell behaviour in 3D |

| 3D hydrogel cultures | cell–matrix interactions, ECM remodelling, stem cell lineage specification, tissue engineering | model in vivo tissues with increasing accuracy | need to isolate effects of multiple hydrogel properties (e.g. stiffness, degradability, biochemistry, etc.), limited solute diffusion restricts gel size and porosity |

| mechanically dynamic culture platforms | cell responses to mechanical loading | model in vivo tissues with increasing accuracy | increased platform complexity, decreased visualization |

| organ on chip platforms | co-culture, pharmacological screening, cell responses to fluid shear stresses and mechanical loading | model in vivo tissues with increasing accuracy | increased platform complexity, decreased visualization, reduced experimental throughput, multiple interacting factors directing cell fate |

3.1. Mechanobiology in two dimensions

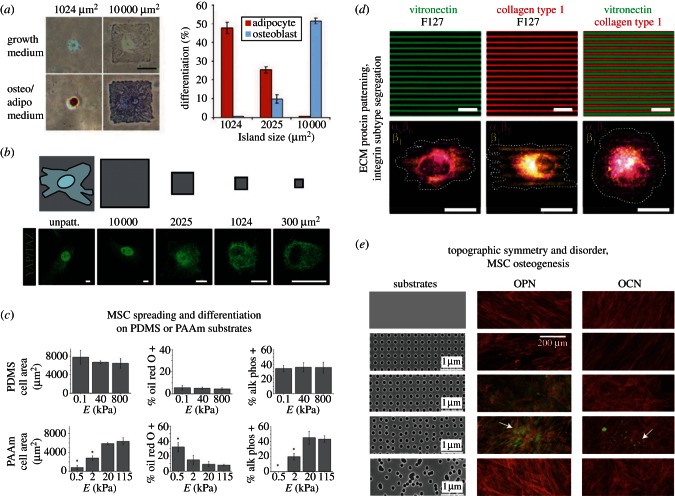

In monolayer (two-dimensional) cultures, MSC adhesion is limited to the cell–substrate contact area, which increases on rigid substrates concomitant with increased focal adhesion density, actin stress fibres and MSC flattening [42]. Flat or rounded MSC morphologies are associated with osteogenesis or adipogenesis, respectively [13], similar to observations resulting from substrate rigidity variation [11]. To increase experimental throughput and permit combinatorial testing of substrate properties, various geometries, rigidities and biochemical compositions are patterned in high-density arrays using methods such as blotting and microcontact- or screen-printing [13,72,77,78]. By patterning individual ECM components on hydrogel substrates, ECM biochemistry and substrate rigidity interact to guide MSC lineage specification [79]. Substrate-directed MSC lineage specification was dramatically demonstrated by patterning substrates with adhesive ‘islands’ that limited cell adhesion areas and therefore governed cell morphology and CSK tension [13,15,80,81]. MSCs that were seeded on large islands became flat and osteogenic, whereas they became rounded and adipogenic on smaller islands (figure 3a) [13].

Figure 3.

Substrate patterning for mechanobiology. (a) Cell shape drives hMSC commitment. Left: bright-field images of hMSCs plated onto small (1024 μm2) or large (10 000 μm2) fibronectin islands after one week in growth or mixed medium. Lipids in adipocytes stain red; alkaline phosphatase in osteoblasts stains blue. Scale bar, 50 μm. Right: percentage differentiation of hMSCs plated onto 1024, 2025 or 10 000 μm2 islands after one week of culture in mixed medium, reproduced from [13] with permission from Elsevier; (b) YAP/TAZ localization is regulated by cell shape, top: grey patterns show the relative size of microprinted fibronectin islands on which cells were plated, and the outline of a cell is shown superimposed to the leftmost unpatterned area (unpatt.), bottom: confocal immunofluorescence images of MSCs plated on fibronectin islands of decreasing sizes (µm2), scale bars, 15 µm, reproduced from [82] with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd (Copyright 2011); (c) influence of substrate elasticity on spreading and differentiation of hMSCs. Quantification of cell spreading and differentiation after 24 h (F-actin) and 7 days (oil red O and alkaline phosphatase) in culture on PDMS and polyacrylamide (PAAm) covalently functionalized with collagen; substrate elastic modulus, E, is indicated; values are mean ± s.d.; *p < 0.05 when compared with 115 kPa gel, reproduced from [83] with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd (Copyright 2012); (d) micrographs of immunolabelled human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) seeded on patterned substrates (top row) of vitronectin, collagen type I, and combined vitronectin/collagen type I, and showing integrin segregation (bottom row: ανβ5, purple; β1, yellow). Black areas are non-adhesive (F127 Pluronics). Scale bars, 20 µm, reproduced from [72] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry; (e) Osteopontin and osteocalcin (OPN/OCN, green) and actin (red) in MSCs after 21 days of culture on substrates with variously ordered nanotopographies, all have 120-nm-diameter pits (100 nm deep, absolute or average 300 nm centre–centre spacing) that are variously ordered. Increased OPN and OCN occurred when pit spacing was disordered (row 4, ± 50 nm from true centre) but not random; arrows indicate bone nodule formation reprinted from [84] with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd (Copyright 2007).

Patterned ECM proteins were also used in recent work to reveal that cells read ECM rigidity, cell shape and cytoskeletal forces as levels of YAP/TAZ activity and that YAP/TAZ function as nuclear relays of ECM mechanics [82]. As shown in figure 3b, YAP/TAZ was localized in the nucleus when MSCs were allowed to spread out and flatten on large fibronectin islands but was predominantly cytoplasmic in rounded MSCs that were cultured on smaller islands. MSC osteogenic induction was inhibited upon depletion of YAP and TAZ, and overexpression of activated 5SA-YAP rescued osteogenesis of MSCs treated with the Rho inhibitor C3 or plated on soft ECM. Rho and the actin cytoskeleton were required to maintain nuclear YAP/TAZ in MSCs and inhibition of ROCK and non-muscle myosin confirmed that cytoskeletal tension was required for YAP/TAZ nuclear localization. In the same work, cells that were cultured on micropatterned fibronectin-coated micropillars were observed to stretch from one micropillar to another and assume a projected cell area comparable to cells plated on large area fibronectin islands although the actual area available for cell–ECM interaction was only about 10 per cent of their projected area; YAP/TAZ remained nuclear on micropillars indicating that YAP/TAZ was primarily regulated by cell spreading rather than by the apparent substrate elasticity. Spreading entails Rho and/or ERK regulated stress fibre assembly and cells on stiff ECM or big islands typically have more prominent stress fibres compared with those plated on soft ECM or small islands. Geometrically defined cell shape therefore leads to specific stress fibre arrangements that modulate MSC lineage specification through mechanisms that include YAP/TAZ-mediated transcriptional regulation.

MSC spreading dynamics and differentiation were recently shown to depend on anchorage site density by Trappmann et al. [83]. They observed differing MSC responses to collagen-coated PDMS or polyacrylamide (PAAm) substrates that ruled out bulk stiffness as the differentiation stimulus. As shown in figure 3c, MSC spreading and differentiation were unaffected by PDMS stiffness but were regulated by the elastic modulus of PAAm. PAAm pore size was inversely correlated with stiffness and led to differences in anchoring densities, suggesting that cells cultured on substrates coated with covalently attached collagen respond to the mechanical feedback of the collagen anchored to the substrate. These studies reinforce the fact that cell–substrate biochemical interactions must be carefully considered in addition to the substrate's bulk material properties. To generate microscale, sparse, multicomponent biochemical surface patterns, Desai et al. [72] developed a technique based on cyclic inking and patterned de-inking of a PDMS stamp. They formed multiple adhesive ligands in spatially organized patterns to investigate the coordinated activity of various integrin subunits that guided cell adhesion and migration. For example, they observed colocalization of αvβ5 integrin to vitronectin and β1 integrin to collagen type I (figure 3d) and determined that ‘cells can assemble a composite picture from distinct ECMs whose ensemble pattern conveys directional information even though the individual patterns do not convey directional information’ (p. 564 of ref. [72]). By probing interactions between specific cell adhesion and ECM molecules, these methods will help dissect pathways mediating cell adhesion and further studies using MSCs will reveal the roles of these pathways in mediating lineage specification.

Cell shape and MSC lineage specification are strongly influenced by their substrate's physical topographies (e.g. via the presence of grooves, steps, pits, etc.) [84–88]. In the 1940s, Weiss [89] introduced the term ‘contact guidance’ to describe substrate topography-directed cell orientation, alignment and migration. Weiss noted, if substrates contained multiple intersecting guide structures, that specific matching between the cells and their guide structures gave rise to ‘selective contact guidance’ (p. 241 of ref. [89]) and postulated that ‘its most plausible explanation would be that temporary linkages are formed between specific molecular groups in the cell surface and complementary groups in the guide structure’ (p. 241 of ref. [89]). Isolating the effects of topographical or chemical cues was a persistent challenge in early contact guidance experiments [90], motivating the development of substrates with precisely controlled features. Microfabrication techniques were subsequently used to make features such as steps [91] and grooves [92], including ultrafine (submicrometre) features [93,94]. For further historical context, the reader is referred to the book chapter by Curtis et al. [95].

As shown in figure 3e, Dalby et al. [84] demonstrated that MSC osteospecific differentiation was possible using nanodisplaced topographies in the absence of soluble osteogenic stimuli. On planar control and ordered nanopatterned materials, MSCs developed a fibroblastic appearance with a highly elongated and aligned morphology, whereas MSCs on substrates with random (disordered) nanotopographies had a more typical, polygonal, osteoblastic morphology, although with negligible osteopontin (OPN) or osteocalcin (OCN). MSCs cultured on substrates with controlled nanotopographical disorder (e.g. the DSQ50 substrate described in Dalby et al. [84]) showed discrete areas of intense cell aggregation and early nodule formation with positive OPN and OCN staining (figure 3e, row 4). Topographical modulation of cell morphology is transferred via the CSK to the nucleus and alters chromosomal positioning and gene regulation [87] and nanotopographies produced a more subtle and specific mode of action than dexamethasone (a commonly used osteoinductive steroid), targeting a small number of canonical pathways (actin, integrin, p38 MAPK and ERK) [96]. In related studies, culture substrates that had nanoscale features with square lattice symmetry (figure 3e, row 2) prolonged retention of MSC markers and multipotency [88]. Inhibition studies for actin/myosin contraction supported the hypothesis that CSK tension is required in MSC retention of multipotency. The authors noted that MSCs have a direct form–function relationship and speculated that a surface needs to influence the adhesion/tension balance to permit self-renewal or targeted differentiation.

3.2. Mechanobiology in three dimensions

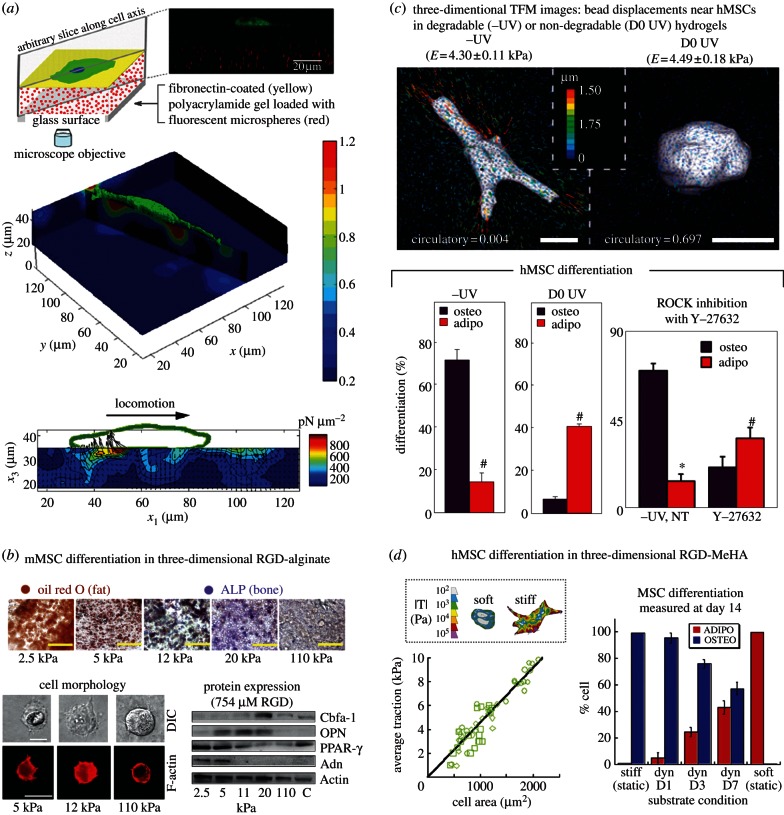

In tissues, cells are embedded in three-dimensional mechanically dynamic environments that are known to support cell morphologies that differ from monolayer cultures [97–99]. Although two-dimensional or quasi-two-dimensional (e.g. micropillars) platforms provide dramatic evidence of mechanically regulated cell fate and key insights into MSC mechanobiology, extending these studies to three-dimensional environments that more accurately recapitulate in vivo conditions is a recognized goal for future work [100]. Cells ‘feel’ in three dimensions [101] and exert dynamic three-dimensional traction forces on compliant substrates during locomotion (figure 4a) [102,103] and invasion [107]. In three-dimensional matrices, integrin–ECM bond densities depend on matrix elasticity [104] and cell-based ECM remodelling alters niche properties that feedback to influence cell fate. ECM mechanical properties that are measured macroscopically (e.g. elasticity) may therefore not accurately represent conditions seen locally by cells.

Figure 4.

Mechanobiology in three dimensions. (a) Measurement of forces exerted by cells on (and in) compliant substrates during locomotion, top: Schematic of a representative gel sample with microscope objective fluorescent microspheres (red) and GFP-transfected cells (green), middle: displacement contour slices along the long axis of the cell, bottom: contour plots show the magnitude of the three-dimensional traction force vector for a single locomoting 3T3 fibroblast in pN µm˗2, top and middle panels are reprinted from Maskarinec et al. [102] (Copyright 2009, National Academy of Sciences, USA); bottom panel is reproduced from Franck et al. [103] with permission from the Public Library of Science; (b) matrix compliance alters MSC fate in three-dimensional matrix culture. Top: in situ staining of encapsulated clonally derived mMSCs (D1) for ALP activity (Fast Blue; osteogenic biomarker, blue) and neutral lipid accumulation (oil red O; adipogenic biomarker, red) after one week of culture in the presence of combined osteogenic and adipogenic chemical supplements within encapsulating matrices consisting of RGD-modified alginate. Bottom left: cross sections of mMSCs 2 h after encapsulation into three-dimensional alginate matrices with varying E and constant (754 μM) RGD density, visualized by differential–interference contrast (DIC) and F-actin staining (Alexa Fluor 568-phalloidin). Bottom right: Western analysis of osteogenic (Cbfa-1, OPN) and adipogenic (PPAR-γ, Adn) protein expression in mMSCs cultured in (754 uM) RGD-alginate hydrogels for one week, reproduced from [104] with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd (Copyright 2010); (c) hydrogel structure-dependent hMSC matrix interactions and fate choice. Top: representative three-dimensional traction force microscopy (TFM) images of hMSCs following 7 days growth-media incubation in hydrogels that were either proteolytically degradable (–UV) or photopolymerized to resist degradation (D0 UV). Bottom: hMSC differentiation following an additional 14 days mixed-medium incubation. Percentage differentiation of hMSCs towards osteogenic or adipogenic lineages in –UV (left) or D0 UV (middle; *p < 0 : 005, t-test). Bottom right: percentage differentiation fate of hMSCs towards osteogenic or adipogenic lineages within –UV gels following 7 days growth-media incubation with or without (no treatment, NT) daily 10 μM Y-27632, and a further 14 days mixed-medium incubation. Reproduced from [105] with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd (Copyright 2013); (d) temporal stiffening in situ regulates hMSC differentiation. Left: average cellular traction plotted against corresponding cell area over a 14 h period, immediately after in situ stiffening. Each dataset represents an individual cell (n = 3). Linear fit is plotted as solid line (slope = 0.046). Inset boxed area shows colour traction maps of representative hMSCs on stiff and soft hydrogels; the pseudocolour bar indicates the spatial traction forces, |T|, in Pascal. Scale bar, 25 µm. Right: mean percentages of hMSCs stained positive for ALP (osteo) and oil red O (adipo) as a function of stiffening time. Error bars indicate the s.d. (n = 3). Substrate condition is defined as static or dynamic (dyn), and for dynamic gels stiffening time (D1, D3, D7 for 1, 3 and 7 days, respectively, of culture in mixed media before stiffening) is reported, reproduced from [106] with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd (Copyright 2012).

Early studies noted that contraction of disc-shaped hydrated collagen lattices by fibroblasts reduced the disc radius by a factor of approximately 5 within one week following cell-seeding, gel contraction rate depended on cell density, and contraction was blocked by addition of CSK inhibitors cytochalasin B and colcemid [108]. Under appropriate culture conditions, MSCs share several properties with fibroblastic cells that include the expression of specific matrix proteins and myofibroblastic markers, notably α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) [109]. These cytoskeletal features enable remodelling and contracture of the ECM, permit adaption of cells to changes in their mechanical microenvironments, and are therefore common to ‘mechanically active’ cell types [110]. ECM contractions represent a type of condensation that results in increased cell density, cell–cell contacts, and inter-cellular paracrine signalling, and is known to occur in development, for example during early chondrogenesis [111]. Synthetic scaffolds that have differing cross-link densities result in differing resistance to cell-mediated contraction and altered MSC chondrogenesis and biosynthesis [112]. Investigations into the relative importance of cell–cell contacts, paracrine signalling and altered cell–matrix interactions during condensation are ongoing [113].

The extent to which MSC morphology depends on scaffold dimensionality independently of the substrate's mechanical and biochemical properties is not fully understood. For example, MSC osteogenesis in three-dimensional alginate polymers occurred predominantly at 11–30 kPa (similar to two dimensions) but MSCs remained roughly spherical in three dimensions, independent of matrix elasticity (figure 4b) [104] in contrast to the two-dimensional case [11]. Instead, cell traction forces were observed to reorganize matrix ligand presentations and therefore alter integrin-matrix binding. Integrin–ECM bonds therefore acted as morphology-independent sensors of matrix elasticity and dimensionality. In the same studies [104], a functional contractile CSK was required for elasticity sensing and cells responded to matrix elasticity within a limited range where contractile forces were functionally relevant: on very compliant substrates, cells did not assemble the CSK-associated adhesion complexes required to exert significant traction forces, whereas on very rigid substrates, the cells did not generate enough force to deform the matrix.

Measurement of forces exerted by cells in three dimensions has been hampered by the relatively limited accessibility of three-dimensional environments to observation compared with planar substrates. Significant progress towards this goal was recently demonstrated by Legant et al. [107], who used bead tracking methods to measure traction forces exerted by individual fibroblasts and MSCs that were embedded in soft three-dimensional hydrogels (Young's moduli, E ∼ 0.6–1.0 kPa) and cultured for 72 h. The cells exerted 0.1–5 kPa tractions with strong forces located predominantly near the tips of long slender extensions that occurred during the invasive process. Stronger traction forces generated by cells that were encapsulated in hydrogels with higher Young's moduli revealed nonlinear reinforcement of cellular contractility in response to substrate rigidity and suggested that such (invasive extensile) regions may be hubs for force-mediated mechanotransduction in three-dimensional settings. The observed MSC branching morphologies seemed to differ from the roughly spherical morphologies of clonally derived murine MSCs observed by Huebsch et al. [104]. These morphological differences likely resulted from differing gel properties. The gels used by Legant et al. [107] were exceedingly soft and proteolytically degradable in contrast to those used by Huebsch et al. [104], which were significantly stiffer (E ∼ 2.5–110 kPa). This hypothesis is supported by recent work by Khetan et al. [105] demonstrating that hMSC differentiation is directed by degradation-mediated cellular traction, independently of cell morphology or matrix mechanics in covalently cross-linked hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogels. When hMSCs were cultured in a bipotential adipogenic/osteogenic media formulation, hydrogels of equivalent elastic moduli that permitted (restricted) cell-mediated degradation exhibited high (low) degrees of cell spreading and high (low) tractions, and favoured osteogenesis (adipogenesis). In the same work, photopolymerized RGD-modified methacrylated hyaluronic acid (MeHA) hydrogels were used to provide similar initial elastic moduli for formulations either permissive (-UV) or inhibitory (D0 UV) to cell-mediated degradation. Switching the permissive hydrogel to a restrictive state through delayed secondary cross-linking reduced further hydrogel degradation, suppressed traction and caused a switch from osteogenesis to adipogenesis in the absence of changes to the extended cellular morphology. As shown in the bottom panels of figure 3c, introduction of non-degradable cross-links mediated a switch from primarily osteogenesis to adipogenesis similar to direct pharmacological inhibition of myosin activity by Y-27632 treatment. In a separate report, Guvendiren & Burdick [106] described an MeHA hydrogel platform that enabled temporal matrix stiffening in the presence of cells to investigate short- (hours) and long-term (days to weeks) cell response to dynamic stiffening. Initial gelation was obtained via an addition reaction and the gel was stiffened by secondary cross-linking through a light-mediated radical polymerization. Their results showed that hMSC spreading and traction forces were correlated and that hMSC differentiation into mixed populations depended on how long they were cultured on a substrate of a specific stiffness (figure 3d). MSC fate is therefore regulated by cell-generated tension that is enabled through cell-mediated degradation of covalently cross-linked matrices. The work summarized earlier emphasizes that the mechanisms by which stem cells respond to biophysical cues are highly dependent on the type of hydrogel used. These and other studies [114–116] demonstrate that photoactive gel systems are effective platforms to study MSC-based matrix degradation and differentiation.

Emerging experimental platforms for stem cell mechanobiology also must account for ECM stiffness gradients [117], nonlinear strain-stiffening [118], soluble growth factors that can be trapped in the ECM and released during controlled scaffold degradation [119], and dynamic mechanical loading. Fluid flow patterns and solute diffusion kinetics differ in three-dimensional hydrogels or ECM scaffolds compared with those seen in two-dimensional (monolayer) geometries and they show a strong dependence on mechanical loading conditions [120]. In these environments, the effects of mechanical loading can appear contradictory owing to the diversity of loading protocols [121], desensitization of cells to long-term strains [122] and incomplete understanding of underlying mechanisms (e.g. relative contributions of mechanical versus fluid-based strains). In microfabricated platforms, cell assemblies and tissue constructs can be patterned in microwell arrays that control the size and shape of three-dimensional samples to study MSC lineage specification [123], improve solute delivery [124] or measure tissue contractility [125]. Continued development of these platforms will help decouple the effects of interacting mechanical and biochemical factors that direct MSC fate.

3.3. Dynamic mechanical loading

Dynamic mechanical strains that are present throughout all stages of development in living tissues modulate a variety of cellular functions that include matrix synthesis by chondrocytes [126–128] and MSCs [129], matrix mineralization by osteogenic MSCs [130] and altered solute transport kinetics [120]. The acknowledged roles that dynamic mechanical forces play in the growth and maintenance of functional connective tissues suggests they are needed for full differentiation and committal of MSCs within mature tissues [121]. Furthermore, Arnsdorf et al. [34] demonstrated that mechanical stimulation (via oscillatory fluid flow) can induce epigenetic changes that control osteogenic cell fate and can be passed to daughter cells, suggesting that ‘downstream’ effects of mechanical loading persist long after forces are applied.

Cyclic mechanical strain applied to cultured MSCs induces endogenous synthesis of potent growth factors that regulate lineage specification [122,131]. For example, MSCs that were seeded on collagen-coated silicone substrates and exposed to cyclic tensile mechanical strain (2.5% strain at a rate of 0.17 Hz) showed approximately fivefold increase in BMP2 levels after 14 days of stimulation, which was mediated by ERK and PI3-kinase pathways and represents an autocrine osteogenic growth factor response to uniaxial strain [122]. Similarly, cyclic compressive loading can promote chondrogenesis of rabbit MSCs by inducing TGF-β1 synthesis [131]. In other studies, cyclic mechanical stretching (3% elongation at 0.1 Hz) promoted osteogenic differentiation of MSCs on substrates coated with various ECM proteins in the absence of osteogenic supplements [132]; this was mediated by FAK phosphorylation, upregulation of the transcription and phosphorylation of Runx2, and subsequent increases of alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralized matrix deposition.

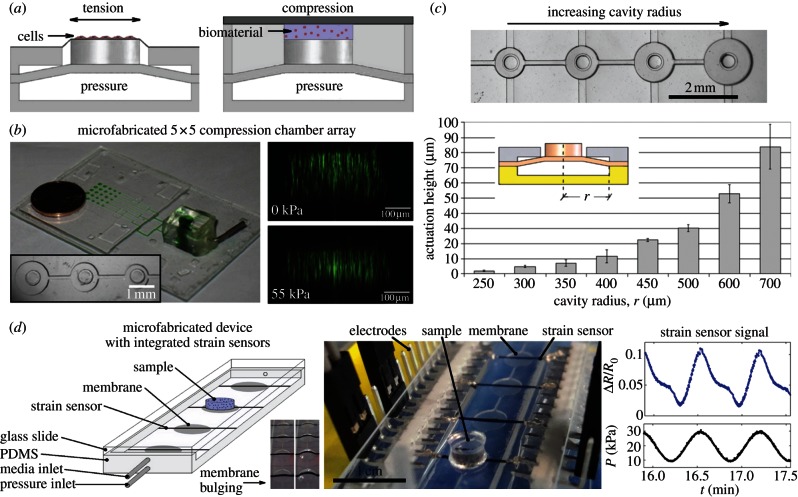

To study the effects of dynamic mechanical loading on MSCs in microfabricated HTS platforms requires mechanical loading methods that are readily microfabricated in arrayed formats. Deformable elastomeric membranes are proving useful for this purpose [59,73,74,133,134] (figure 5). As shown in figure 5a, pressure supplied through dedicated channel networks deforms overlying elastomeric structures and thereby transfers mechanical loads to samples for cell stretching [59,74] or compression of arrayed biomaterials (figure 5b) [73]. Standard soft-lithography methods are used to produce membrane arrays that simultaneously apply a range of strains (figure 5c) that can be measured in situ using integrated elastomeric strain sensors (figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Dynamic mechanical loading of cells, biomaterials, and tissues using deformable elastomeric membranes. (a) Schematized operation of bulging membranes to apply tensile or compressive strains. Pressure is supplied through an underlying channel layer to deform membranes, cylindrical loading posts that are attached to the membranes deform overlying cell culture films (tension) or compress biomaterial samples; (b) left: microfabricated device with a 5 × 5 array of mechanically active three-dimensional culture sites (green dye in the pressurized actuation channels). Increasing actuation cavity size across the array enables a range of mechanical conditions to be created simultaneously. Right: orthogonally resliced confocal image of fluorescent bead markers within a single hydrogel cylinder over a unit on the array at rest (top) and when actuated at 55 kPa (bottom), reproduced from [73] with permission from Elsevier; (c) multiple actuation heights are achieved on a single device using a single driving pressure by microfabricating multiple pressure cavity radii, reproduced from [133] with permission from IOP Publishing; (d) elastomeric strain sensors that are integrated within deformable membranes provide online readouts of membrane actuation height, reproduced from [134] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Moraes et al. [59] developed a microfabricated membrane array capable of simultaneously applying cyclic equibiaxial substrate strains ranging in magnitude from 2 to 15 per cent to small populations of adherent cells. Using this platform, they identified a novel co-dependence between strain magnitude and duration and β-catenin nuclear accumulation. In related work, Moraes et al. [73] developed a platform for compression of arrayed biomaterials in which compressive strains ranging from 6 to 26 per cent were simultaneously applied across the biomaterial array, demonstrating that nuclear and cellular deformation of PEG-encapsulated mouse MSCs (C3H10T1/2) were nonlinearly related. Such platforms undoubtedly have broad applicability to mechanobiology and may provide insights into the largely unknown roles of mechano-chemical cycles in directing cell fate [135].

3.4. Vivo in vitro: model physiologies

Appreciation for the sensitivity of cells to mechanical and biochemical properties of their extracellular microenvironments has clarified the limitations of traditional cell culture platforms and highlighted the need for new platforms with increased physiological relevance [136–138]. Emerging culture platforms combine mechanical loading and fluid flow in three-dimensional microenvironments to produce functional tissue arrays that recapitulate key aspects of physiological and pathological conditions in vitro (figure 6).

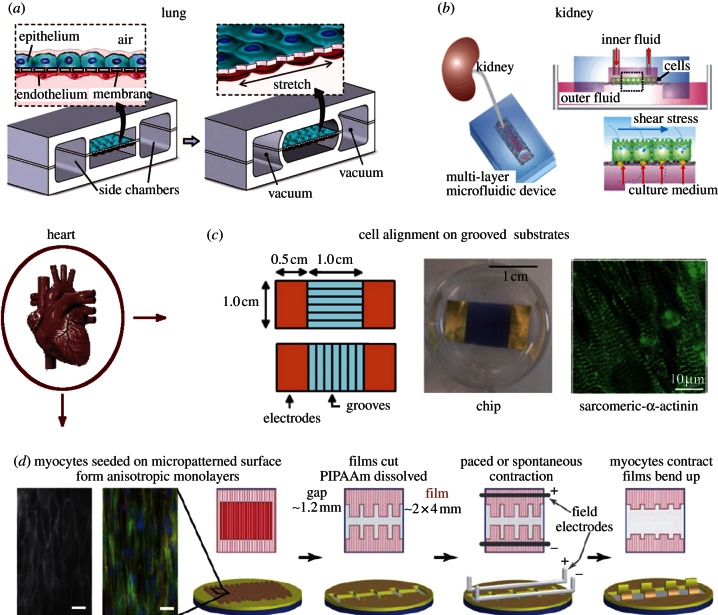

Figure 6.

‘Organ-on-a-chip’ platforms that recapitulate key aspects of in vivo niches. (a) A ‘lung-on-a-chip’ device that uses compartmentalized PDMS microchannels to form an alveolar–capillary barrier on a thin, porous, flexible PDMS membrane coated with ECM and recreates physiological breathing movements by applying vacuum to the side chambers that cause mechanical stretching of the PDMS membrane, reproduced from [75] with permission from AAAS; (b) a multi-layer microfluidic device for efficient culture and analysis of renal tubular cells, reproduced with from [139] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry; (c) schematic and photograph of a cardiomyocyte culture chip with microgrooves oriented either parallel or perpendicular to electrodes, reproduced from [140] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry; (d) ‘heart-on-a-chip’ for contractility assays with anisotropic layers of myocytes, scale bar, 20 µm, reproduced from [76] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Dynamic mechanical loading is essential to study organ-level responses in pulmonary inflammation and infection, for example using a microfabricated ‘lung-on-a-chip’ (figure 6a) [75]; cyclic mechanical strain accentuates toxic and inflammatory responses of the lung and enhances epithelial and endothelial uptake of silica nanoparticles. Physiological breathing movements simulated by cyclic strain (10% at 0.2 Hz) augmented endothelial expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) induced by silica nanoparticles and this effect was sufficient to induce endothelial capture of circulating neutrophils, promote their transmigration across the tissue–tissue interface, and promote their accumulation on the epithelial surface. The lung-on-a-chip illustrates that multiple cell types (co-cultures) interact to produce observed organ-level physiological or pathological responses to biochemical and/or mechanical stimulants. In another study, Jang et al. [139] mimicked the kidney collecting duct system using microfabricated tubular environments for primary rat inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells (figure 6b). They observed that fluidic shear stress of 0.1 Pa for the time period of 5 h enhanced IMCD polarization and CSK and cell junction rearrangement.

Mechanical cues are used in combination with electrical and biochemical stimulation to study cardiovascular constructs in organ-on-a-chip microdevices [76,140]. For example, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes that were cultivated on micro-grooved substrates for 7 days were elongated and aligned along the microgrooves forming a well-developed contractile apparatus, as evidenced by sarcomeric α-actinin staining (figure 6c) [140]. Simultaneous application of biphasic electrical pulses and topographical cues resulted in gap junctions that were confined to the cell–cell end junctions rather than to the punctate distribution found in neonatal cells, and electrical field stimulation further enhanced cardiomyocyte elongation when microgrooves were oriented parallel to the electric field. In another ‘heart-on-a-chip’ platform (figure 6d) [76], biohybrid constructs of an engineered, anisotropic ventricular myocardium were cultured on elastomeric thin films to measure contractility, action potential propagation and cytoskeletal architecture. The authors presented techniques for real-time data collection and analysis during pharmacological intervention and emphasized the platform's use as an efficient means of measuring structure–function relationships in constructs that replicate the hierarchical tissue architectures of laminar cardiac muscle.

Organ-on-a-chip platforms enable experimental mechanobiology with increased physiological and pathological relevance. Ambitious ongoing efforts aim to study interactions between multiple organ constructs in ‘human-on-a-chip’ platforms [141]. These platforms will supplement animal studies, for example in toxicology studies, by providing testing environments that are assembled using a patient's own cells.

3.5. Mesenchymal stem cell heterogeneity and single cell handling

Heterogeneity within cell populations is a confounding problem that has largely been ignored in mechanobiology to date. Emerging tools can be adopted to study heterogeneous cell responses and to distinguish between heterogeneous characteristics that are either intrinsic to a particular cell type or result from various culture conditions (e.g. from extended in vitro culture). In this review, we used ‘MSC’ in reference to bone-marrow-derived progenitors that have well-known osteo-, chondro- and adipogenic (trilineage) potential. However, bone marrow contains other progenitors (e.g. haematopoietic progenitors) and typical MSC populations contain a variety of subtly differing cells that have various growth rates, morphologies and phenotypes [18,23,109]. Furthermore, MSC-like cells are discovered in increasing numbers of tissues and the isolation of a ‘pure’ population of multipotent marrow stromal stem cells remains elusive and is likely a misnomer: indentifying a ‘phenotypic fingerprint’ has been likened to shooting at a moving target [109] owing to the dynamic nature of cells such as MSCs and ‘true’ plasticity is only demonstrated when a single (clonogenic) cell forms a progeny of multiple phenotypes in vivo [142]. Population-scale cell analyses neglect the fact that MSC populations are not homogeneous [143], that MSC gene and protein expression profiles depend on culture conditions [144], and that MSC identification or sorting using adhesion assays or light-scattering properties during flow cytometry provides only a partial enrichment of multipotent cells [145]. MSC responses to substrate elasticity and growth factors is also heterogeneous; for example, switching induction medium after one week of MSC culture on substrates with defined elasticity produced a mixed phenotype [11].

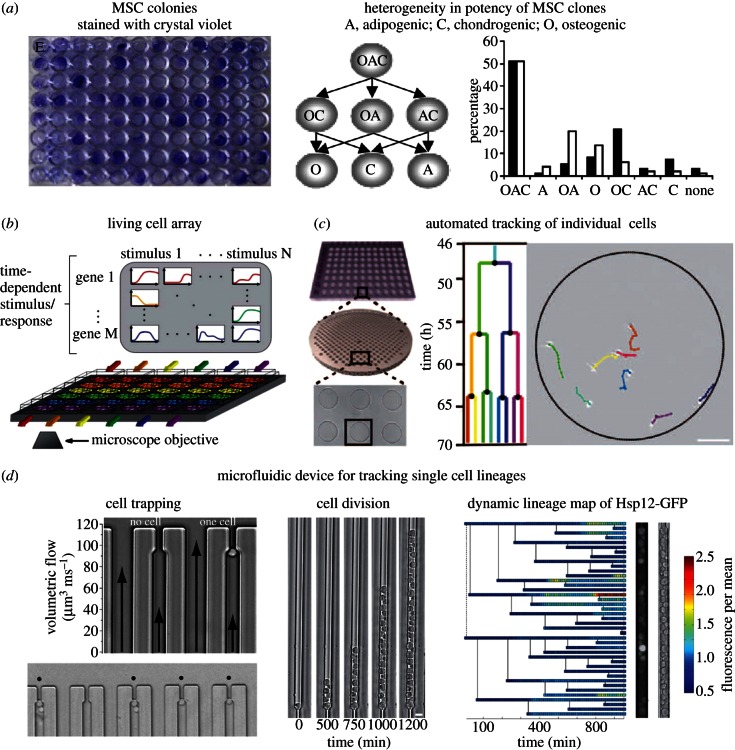

Obstacles associated with MSC heterogeneity can be partially overcome by characterizing them based on their individual (clonal) ability to proliferate and differentiate. Cell division can result in daughter cells with the same or disparate fates (symmetric or asymmetric division, respectively), and analysis of the progeny at each stage provides a more accurate picture of the original cell's potential. Using a high-capacity assay to quantify clonal MSC trilineage potential, Russell et al. [18] found a complex hierarchy of lineage commitment in MSC clones derived from two healthy adult human donors (figure 7a): approximately 50 per cent were tripotent, and the remaining 50 per cent were either bipotent, unipotent or did not differentiate. Significant differences in bipotent osteogenic/adipogenic populations were found between donors (approx. 5% or approx. 20% of the total cells, depending on the donor) and these values were roughly reversed for the case of osteogenic/chondrogenic bipotency; the loss of trilineage potential was associated with diminished proliferation capacity and CD146 expression. These cell source (donor)-dependent heterogeneities within MSC populations that were demonstrated using clonal assays should inspire clonal mechanobiology assays. In population-based assays aimed at measuring mechanical effects on MSC differentiation, altered subpopulation proliferation rates can confound data interpretation. Clonal assays and individual cell tracking are required to distinguish between mechanically directed differentiation versus altered subpopulation proliferation rates.

Figure 7.

Clonogenic assays and single cell tracking. (a) Cell colonies in 96-well microplates stained with Crystal Violet after 21 days in culture (left), and heterogeneity in potency of mesenchymal stem cell clones from two donors (right), abbreviations: A, adipogenic phenotype; C, chondrogenic phenotype; O, osteogenic phenotype, reproduced [18] with permission from Wiley Publishing; (b) schematic of a microfluidic real-time gene expression array. Reporter cell lines for multiple genes and transcription factors are seeded in separate channels and stimulated with soluble stimuli in the orthogonal direction (coloured arrows), reproduced with from [146] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry; (c) schematic of hydrogel arrays with hundreds of microwells containing single muscle stem cells, followed by time-lapse microscopy, scale bar, 100 µm, reproduced from [147] with permission from AAAS; (d) trapping single cells in lineage chambers. Top left: average volumetric flow rates through the bypass and trapping channels are proportional to the length of arrows superimposed on the bright-field image, bottom left: bright-field image showing an array of trapping chambers filled with single cells that are identified by black dots, middle: time course of clonogenic expansion, right: dynamic lineage map of fluorescently tagged heat shock protein-12 (Hsp12-GFP) levels normalized to the mean fluorescence of the population, reproduced from Rowat et al. [148] (Copyright 2009, National Academy of Sciences, USA).

Mechanical properties are reflective of cell phenotype and are therefore another measure of heterogeneity. Experimental platforms that are used to mechanically characterize cells on an individual basis include atomic force microscopy (AFM), electro-deformation, optical tweezers (OT), magnetic pulling or twisting cytometry (MPC or MTC), and other methods that are reviewed in detail elsewhere [149]. AFM is a scanning probe technique that is use for cell, hydrogel and microtissue stiffness measurements [150]. Mechanical stimulation and force spectroscopy of specific cell adhesion molecules is achieved by functionalizing AFM probes with ECM proteins or whole cells [151]. Maloney et al. [19] used AFM to mechanically assess MSC phenotype transitions during extended passage (17 population doublings) on polystyrene culture substrates: they observed passage-dependent CSK coarsening, increased stress fibre radius (from 100 to 500 nm), and increased MSC stiffness (2–8 kPa). The authors noted that osteogenesis of cuboidal MSCs was better correlated with average MSC stiffness than with surface marker presentation. Although individual cells can be mechanically probed using AFM, this method does not share most of the benefits associated with miniaturized platforms.

MSC heterogeneity is efficiently studied using microfluidic platforms that provide controllable medium perfusion [152–154] for long-term culture of individually captured cells [155], high-density arrayed cell cultures (figure 7b) [156] and arrayed cell niches [157,158]. These and similar platforms enabled on-chip gene profiling [156,159,160] and high-throughput single cell bioinformatics [161]. Using automated image acquisition and cell tracking software, individual cells can be tracked during migration and proliferation (figure 7c) [147]. For example, Rowat et al. [148] used a microfluidic platform to trap cells in ‘lineage chambers’ where single progenitor cells were constrained to grow in a line (figure 7d): flow through a bypass channel doubled when a single cell was trapped, increasing the probability for cells to flow through the bypass while still allowing for fluid flow through the trapping channel. Using this platform, they observed fluctuations and patterns in protein expression that propagate in single cells over time and over multiple generations. They noted the platform's utility to study asymmetries at cell division, and correlations between cells caused by their pedigree, replicative age or other physical traits such as volume. Adapting these strategies for mechanobiology assays that screen substrate properties is relatively straightforward given that substrates can be patterned in high-density arrays using methods such as blotting and microcontact- or screen-printing [13,72,77,78].

Dynamic mechanical forces are applied to individual cells in microfluidic devices using acoustic, electrical, magnetic or optical forces [149]. Minimal mechanical contact between cells and device structures enables integration of these methods in microfluidic platforms for automated cell sorting and mechanobiological analysis. Electrical forces are used to deform whole individual mammalian cells [162,163], to correlate cell deformability with CSK features [164] and for molecular force spectroscopy [165]. Functionalized beads that are attached to cells permit force coupling through specific molecular binding proteins (e.g. integrins), for example using OT [166], MPC [167,168] or MTC [169,170]. By applying MPC forces to integrin-bound magnetic beads, nearly instantaneous calcium influx was observed in proportion to mechanical stresses, representing a direct and immediate mechanotransduction response to stresses applied through integrins [168]. MTC was used to measure force-dependent CSK stiffening [169], induced stretch-activated calcium flux in fibroblasts [171] and to show that integrins focus mechanical stresses locally on G proteins within focal adhesions at the site of force application [170]. The demonstrated use of these methods for mechanobiology and their integration in microfluidic platforms suggests their potential utility for high-throughput clonogenic mechanobiology.

4. Open questions and future directions

Mechanistic descriptions of MSC mechanobiology require continued refinement. Molecular mediators between CSK tension and transcriptional regulators such as YAP/TAZ await discoveries [82], and the competition between canonical and non-canonical Wnt signalling in mechanically directed MSC differentiation also requires clarification [121]. Increased experimental throughput of microfabricated platforms will help clarify cytosolic and nuclear interactions between smads, YAP/TAZ, β-catenin, and other transcriptional regulators. Patterned ECM proteins that control cell shape provided valuable insights into these mechanisms and will continue to play key roles in experimental mechanobiology. Future work will integrate high-density patterned substrates within microfluidic devices for prolonged cell culture and combinatorial screening of soluble and mechanical factors.

The ability to maintain MSC multipotency during prolonged culture using nanofabricated topological features [88] is intriguing and worthy of further investigation. These methods are beneficial to regenerative medicine strategies that require ex vivo expansion of MSCs extracted from patients. The potential generality of prolonged multipotency should be tested using a wide variety of cell sources (e.g. MSCs from various donors and tissue sources). Nanoscale-disordered topographies that target a small number of canonical pathways may prove preferable to soluble factors for directed MSC differentiation [84,96]. Topographical features are readily patterned on a variety of substrates and are well suited for high-density arrays in which large numbers of feature properties are used to screen MSC responses. The effects of ordered versus disordered features also raises interesting questions related to potential roles of symmetry and disorder in vivo. As experimental cell biology embraces heuristic approaches to problem solving, the use of multiscale and variously ordered topographies will increasingly be used to study cell fate in complex environments [172]. The trend towards larger sample numbers and combinatorial experiments require increasingly sophisticated data acquisition, statistical analysis [79] and systems biology modelling efforts [173].

Heterogeneity within cell populations is a pervasive problem and a fruitful area for discovery. Despite the acknowledged heterogeneity of MSC populations, biomarkers that correlate with osteogenic outcome of MSC differentiation independent of donor and tissue source have been identified [174] and protein–protein interaction networks shared by pluripotent cells [175] suggest that progenitors do share common properties. Nevertheless, numerous population-based studies should be verified using clonogenic assays to determine the relative importance of intrinsic and extrinsic causes of heterogeneity. The effects of dynamic mechanical stimulation on MSC multilineage potential, for example, have not been tested using clonogenic assays. Deformable membrane arrays [59] are particularly well suited for these studies, but long-term mechanically dynamic culture requires careful consideration of cell attachment [176].

Further studies are needed to investigate differences in cell behaviour that are observed between two- and three-dimensional cultures [97,104,177]. Although cell-based traction forces can be measured in three-dimensional hydrogels [107], measuring the local elasticity that is probed by cells is challenging, particularly when cell-based ECM remodelling alters these properties. Macroscale hydrogel elasticity measurements may therefore not accurately reflect the elasticity sensed by embedded cells. Although this problem is particularly challenging, it may be possible to measure embedded bead displacements resulting from applied contact-free forces (e.g. magnetic) and thereby estimate mechanical properties throughout the hydrogel or matrix volumes.

Regenerative medicine is a key application of MSCs that requires detailed knowledge of MSC mechanobiology. In addition to their multilineage potential, MSCs secrete immunosuppressive molecules that facilitate regeneration of injured tissues [178]. Heterogeneity of MSC immunosuppressive potential is, however, largely unexplored and formidable practical difficulties are associated with differentiating and pre-conditioning MSCs for subsequent survival in physiological environments that often contain high levels of inflammatory mediators and catabolic cytokines [179]. This challenge reaffirms the importance of understanding the MSC niche under normal and pathological conditions [180]. We discussed experimental mechanobiology platforms that used high-throughput screening of niche factors and increased biomimicry to provide increasingly accurate mechanistic descriptions of subcellular components regulating cell fate. Microtechnology platforms are promising for this purpose because they provide multiple context-dependent ‘niches’ that can be used for basic studies or ex vivo expansion of clonogenic MSCs.

In this review, we introduced MSC mechanobiology through the context of contractility-based mechanosensing and mechanically regulated lineage specification. We described MSC responses to static and dynamic mechanical cues in two- and three-dimensional microenvironments. The platforms we described and the results obtained clearly demonstrated that mechanical forces play key roles in MSC biology and that much remains to be learned. Microfabricated array-based platforms will accelerate discoveries in MSC mechanobiology and biomimicry will help translate experimental results to tissue engineering, regenerative medicine and toxicology applications. These challenges present opportunities for multidisciplinary research that will transform the way cells and tissues are cultured in the laboratory.

References

- 1.Moore KA, Lemischka IR. 2006. Stem cells and their niches. Science 311, 1880–1885 10.1126/science.1110542 (doi:10.1126/science.1110542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin T, Li LH. 2006. The stem cell niches in bone. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1195–1201 10.1172/Jci28568 (doi:10.1172/Jci28568) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehninger A, Trumpp A. 2011. The bone marrow stem cell niche grows up: mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages move in. J. Exp. Med. 208, 421–428 10.1084/Jem.20110132 (doi:10.1084/Jem.20110132) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosgrove BD, Sacco A, Gilbert PM, Blau HM. 2009. A home away from home: challenges and opportunities in engineering in vitro muscle satellite cell niches. Differentiation 78, 185–194 10.1016/j.diff.2009.08.004 (doi:10.1016/j.diff.2009.08.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. 2009. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science 324, 1673–1677 10.1126/science.1171643 (doi:10.1126/science.1171643) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frontera WR, Slovik DM, Dawson DM. 2006. Exercise in rehabilitation medicine, 2nd edn Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittenger MF, et al. 1999. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284, 143–147 10.1126/science.284.5411.143 (doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.143) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abedin M, Tintut Y, Demer LL. 2004. Mesenchymal stem cells and the artery wall. Circ. Res. 95, 671–676 10.1161/01.RES.0000143421.27684.12 (doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000143421.27684.12) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JH, Yip CY, Sone ED, Simmons CA. 2009. Identification and characterization of aortic valve mesenchymal progenitor cells with robust osteogenic calcification potential. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 1109–1119 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080750 (doi:10.2353/ajpath.2009.080750) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breitbach M, et al. 2007. Potential risks of bone marrow cell transplantation into infarcted hearts. Blood 110, 1362–1369 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063412 (doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-063412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. 2006. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677–689 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yip CY, Chen JH, Zhao R, Simmons CA. 2009. Calcification by valve interstitial cells is regulated by the stiffness of the extracellular matrix. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 936–942 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182394 (doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182394) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. 2004. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev. Cell 6, 483–495 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00075-9 (doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00075-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang YK, Yu X, Cohen DM, Wozniak MA, Yang MT, Gao L, Eyckmans J, Chen CS. 2011. Bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced signaling and osteogenesis is regulated by cell shape, RhoA/ROCK, and cytoskeletal tension. Stem Cells Dev. 21, 1176–1186 10.1089/scd.2011.0293 (doi:10.1089/scd.2011.0293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilian KA, Bugarija B, Lahn BT, Mrksich M. 2010. Geometric cues for directing the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 4872–4877 10.1073/pnas.0903269107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0903269107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David V, Martin A, Lafage-Proust MH, Malaval L, Peyroche S, Jones DB, Vico L, Guignandon A. 2007. Mechanical loading down-regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in bone marrow stromal cells and favors osteoblastogenesis at the expense of adipogenesis. Endocrinology 148, 2553–2562 10.1210/en.2006-1704 (doi:10.1210/en.2006-1704) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luu YK, Pessin JE, Judex S, Rubin J, Rubin CT. 2009. Mechanical signals as a non-invasive means to influence mesenchymal stem cell fate, promoting bone and suppressing the fat phenotype. Bonekey Osteovision 6, 132–149 10.1138/20090371 (doi:10.1138/20090371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell KC, Phinney DG, Lacey MR, Barrilleaux BL, Meyertholen KE, O'Connor KC. 2010. In vitro high-capacity assay to quantify the clonal heterogeneity in trilineage potential of mesenchymal stem cells reveals a complex hierarchy of lineage commitment. Stem Cells 28, 788–798 10.1002/Stem.312 (doi:10.1002/Stem.312) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maloney JM, Nikova D, Lautenschlager F, Clarke E, Langer R, Guck J, Van Vliet KJ. 2010. Mesenchymal stem cell mechanics from the attached to the suspended state. Biophys. J. 99, 2479–2487 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.052 (doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.052) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nombela-Arrieta C, Ritz J, Silberstein LE. 2011. The elusive nature and function of mesenchymal stem cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 126–131 10.1038/Nrm3049 (doi:10.1038/Nrm3049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingber DE. 2003. Mechanosensation through integrins: cells act locally but think globally. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1472–1474 10.1073/pnas.0530201100 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0530201100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. 2009. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21–33 10.1038/nrm2593 (doi:10.1038/nrm2593) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Docheva D, Popov C, Mutschler W, Schieker M. 2007. Human mesenchymal stem cells in contact with their environment: surface characteristics and the integrin system. J. Cell Mol. Med. 11, 21–38 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00001.x (doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00001.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eyckmans J, Boudou T, Yu X, Chen CS. 2011. A hitchhiker's guide to mechanobiology. Dev. Cell 21, 35–47 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.015 (doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanchanawong P, Shtengel G, Pasapera AM, Ramko EB, Davidson MW, Hess HF, Waterman CM. 2010. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature 468, 580–584 10.1038/nature09621 (doi:10.1038/nature09621) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Provenzano PP, Keely PJ. 2011. Mechanical signaling through the cytoskeleton regulates cell proliferation by coordinated focal adhesion and Rho GTPase signaling. J. Cell Sci. 124, 1195–1205 10.1242/Jcs.067009 (doi:10.1242/Jcs.067009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Y, Chen CS, Fu J. 2012. Forcing stem cells to behave: a biophysical perspective of the cellular microenvironment. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 519–542 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155306 (doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155306) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. 2007. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 619–647 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618 (doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin Z, Buehler MJ, Kreplak L. 2010. A multi-scale approach to understand the mechanobiology of intermediate filaments. J. Biomech. 43, 15–22 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.004 (doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawkins T, Mirigian M, Selcuk Yasar M, Ross JL. 2010. Mechanics of microtubules. J. Biomech. 43, 23–30 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.005 (doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stricker J, Falzone T, Gardel ML. 2010. Mechanics of the F-actin cytoskeleton. J. Biomech. 43, 9–14 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.003 (doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellegrin S, Mellor H. 2007. Actin stress fibres. J. Cell Sci. 120, 3491–3499 10.1242/jcs.018473 (doi:10.1242/jcs.018473) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]