Abstract

Background: Acute ozone (O3) exposure results in greater inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in obese versus lean mice.

Objectives: We examined the hypothesis that these augmented responses to O3 are the result of greater signaling through tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) and/or interleukin (IL)-13.

Methods: We exposed lean wild-type (WT) and TNFR2-deficient (TNFR2–/–) mice, and obese Cpefat and TNFR2-deficient Cpefat mice (Cpefat/TNFR2–/–), to O3 (2 ppm for 3 hr) either with or without treatment with anti–IL-13 or left them unexposed.

Results: O3-induced increases in baseline pulmonary mechanics, airway responsiveness, and cellular inflammation were greater in Cpefat than in WT mice. In lean mice, TNFR2 deficiency ablated O3-induced AHR without affecting pulmonary inflammation; whereas in obese mice, TNFR2 deficiency augmented O3-induced AHR but reduced inflammatory cell recruitment. O3 increased pulmonary expression of IL-13 in Cpefat but not WT mice. Flow cytometry analysis of lung cells indicated greater IL-13–expressing CD4+ cells in Cpefat versus WT mice after O3 exposure. In Cpefat mice, anti–IL-13 treatment attenuated O3-induced increases in pulmonary mechanics and inflammatory cell recruitment, but did not affect AHR. These effects of anti–IL-13 treatment were not observed in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice. There was no effect of anti–IL-13 treatment in WT mice.

Conclusions: Pulmonary responses to O3 are not just greater, but qualitatively different, in obese versus lean mice. In particular, in obese mice, O3 induces IL-13 and IL-13 synergizes with TNF via TNFR2 to exacerbate O3-induced changes in pulmonary mechanics and inflammatory cell recruitment but not AHR.

Keywords: airway responsiveness, bronchoalveolar lavage, IL-5, inflammation, MIP-3α

Ozone (O3), an air pollutant, causes respiratory symptoms and reductions in lung function (Alexis et al. 2000). O3 is also a trigger for asthma: Asthma-related emergency room visits increase on days of high ambient O3 (Fauroux et al. 2000; Gent et al. 2003). O3 activates the innate immune system causing pulmonary infiltration with neutrophils and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), a characteristic feature of asthma (Garantziotis et al. 2009).

Two-thirds of the U.S. population is obese or overweight (National Center for Health Statistics 2012), and obesity is a risk factor for asthma (Shore and Johnston 2006). Nevertheless, our understanding of how obesity impacts pulmonary responses to O3 is still rudimentary. O3-induced decrements in lung function are greater in obese and overweight than lean human subjects (Alexeeff et al. 2007; Bennett et al. 2007). Obese mice also exhibit greater pulmonary inflammation and greater AHR than lean mice after acute O3 exposure (Johnston et al. 2006; Shore et al. 2003). The mechanistic basis for the effect of obesity on responses to O3 is unknown.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) is induced in the lung after O3 exposure and has been implicated in responses to acute O3 exposure (Cho et al. 2001; Matsubara et al. 2009; Shore et al. 2001; Yang et al. 2005). Serum TNFα increases with obesity (Katsuki et al. 1998; Williams et al. 2012). TNFα promoter polymorphisms that augment TNFα expression are associated with an increased obesity-related risk of asthma, especially nonatopic asthma (Castro-Giner et al. 2009), suggesting that TNFα may also be relevant for obesity-related asthma. The role of TNFα in the augmented responses to acute O3 observed in obese mice has not been established.

TNFα binds to two receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2, which differ in their ability to induce inflammation and apoptosis and in their affinity for cleaved versus membrane-associated TNFα (Naude et al. 2011). In lean mice, O3-induced AHR requires TNFR2 (Shore et al. 2001), though TNFR1 may also play a role (Cho et al. 2001). TNFR2 is also required for the innate AHR that is observed in obese mice (Williams et al. 2012), but the role of TNFR2 in the augmented responses to O3 observed in obese mice is not established.

The first purpose of this study was to examine the hypothesis that TNFR2 is required for the augmented response to acute O3 exposure associated with obesity. To examine this hypothesis, we bred Cpefat mice that were genetically deficient in the TNFR2 receptor (Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice). Cpefat mice lack carboxypeptidase E (Cpe), an enzyme involved in appetite regulation and energy expenditure (Leibel et al. 1997). Lack of Cpe leads to obesity (Johnston et al. 2006, 2010). We assessed airway responsiveness and pulmonary injury and inflammation in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice along with wild-type (WT), Cpefat, and TNFR2–/– mice.

Interleukin (IL)-13 also plays an important role in AHR. In mice, exogenous administration of IL-13 to the lungs results in AHR, and IL-13–blocking reagents inhibit allergen-induced AHR (Grunig et al. 1998; Wills-Karp et al. 1998). IL-13 may also play a role in responses to acute O3 exposure: In lean BALB/c mice, IL-13 deficiency reduces O3-induced AHR and inflammation (Pichavant et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2008), but the role of IL-13 in responses to O3 in obese mice is not established. Consequently, to examine the hypothesis that IL-13 contributes to obesity-related differences in the response to O3, we measured IL-13 expression and examined the effects of anti–IL-13 antibodies in obese and lean mice. Because TNF and IL-13 can synergize to promote the expression of chemokines that may contribute to the effects of O3 (Reibman et al. 2003), we examined the effect of anti–IL-13 treatment in both TNFR2-sufficient and -deficient mice.

Methods

Animals. This study was approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals. Animals were treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering. We bred Cpefat/TNFR2–/–, TNFR2–/–, Cpefat, and WT mice as previously described (Williams et al. 2012). Female mice were on a C57BL/6 background, were fed standard mouse chow diets, and were 10–12 weeks old.

Protocol. We exposed mice to 2 ppm O3 for 3 hr. Twenty-four hours after exposure, we measured pulmonary mechanics and airway responsiveness, performed bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), harvested blood by cardiac puncture, and collected lungs for preparation of RNA. Controls for these mice were not exposed to O3 but were otherwise treated identically and studied simultaneously. Pulmonary mechanics and airway responsiveness for these unexposed mice have been previously reported (Williams et al. 2012). We treated other mice with anti–IL-13 antibody (2 μg/g body weight intraperitoneally) 24 hr before O3 exposure. In a final cohort of O3-exposed mice, we harvested lungs at 24 hr, enzymatically digested the lungs, and isolated lung cells for flow cytometry to quantitate IL-13–expressing CD4+ cells.

Measurement of pulmonary mechanics and airway responsiveness. We generated quasi static pressure volume (PV) curves, assessed baseline pulmonary mechanics using the forced oscillation technique, and measured airway responsiveness to aerosolized methacholine as previously described (Williams et al. 2012). We assessed Newtonian resistance (Rn), which largely reflects the resistance of the conducting airways, and the coefficients of lung tissue damping (G) and lung tissue elastance (H), which reflect changes in the small airways and pulmonary parenchyma.

Bronchoalveolar lavage. We lavaged lungs and counted BAL cells as previously described (Williams et al. 2012). We measured BAL cytokines, chemokines, and hyaluronan by ELISA (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN; eBioscience, San Diego, CA; and Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT). We measured BAL protein by Bradford assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

RNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). We used real-time PCR to quantitate IL-13 and IL-17A mRNA expression as described (Shore et al. 2011). We subtracted Ct values for a housekeeping gene, 36B4 (rplp0) (which codes for a ribosomal protein), from Ct values for IL-13 or IL-17A to obtain ΔCt values. We expressed changes in mRNA relative to values from the WT unexposed mice, using the ΔΔCt method.

Flow cytometry. We flushed the lungs to remove blood cells, and then excised, minced, and digested lung tissue as previously described (Kasahara et al. 2012). We cultured lung cells either with or without PMA (phorbol myristate acetate) and ionomycin, in the presence of Golgi Stop (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ), for 5 hr before staining for flow cytometry. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, incubated with anti-Fcγ blocking mAb (clone 93; Biolegend, San Diego, CA), and washed. We stained the cells with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated CD4 mAb (clone GK1.5; Biolegend) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-mouse IL-13 (clone eBio13A; eBioscience). We passed the cells through a BD Canto flow cytometer (BD Bioscience), and analyzed the data with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistics. We used factorial analysis of variance to assess the significance of differences in outcome indicators, as previously described (Williams et al. 2012). We performed analyses using Statistica version 6 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK).

Results

Body mass. There was a significant effect of Cpe (p < 0.001) but not TNFR2 genotype on body mass. Whether or not they were deficient in TNFR2, Cpefat mice weighed about twice as much as lean controls, consistent with previous observations (Williams et al. 2012).

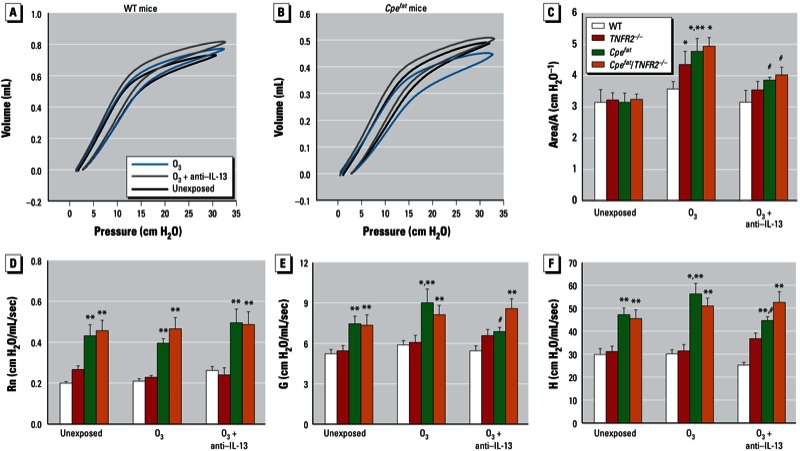

Pulmonary mechanics and airway responsiveness. In WT mice, no significant differences in the PV curve of the lungs were observed in O3-exposed versus unexposed mice (Figure 1A). However, in Cpefat mice, there was a rightward shift and widening of the PV loop indicative of increased hysteresis in O3-exposed versus unexposed mice (Figure 1B). To quantitate these changes, we measured the area of the PV loop, and normalized it by A, the difference in volume between total lung capacity and end expiratory lung volume (height of the PV loops in Figure 1). Area/A is a measure of the thickness of the PV loop. A was lower in obese versus lean mice, as previously reported (Williams et al. 2012), but there was no difference in A in O3-exposed versus unexposed mice (data not shown). Consistent with the increased hysteresis induced by O3 in Cpefat but not WT mice (Figure 1A,B), Area/A was greater in O3-exposed versus unexposed Cpefat mice, whereas O3 had no effect on Area/A in WT mice (Figure 1C). Area/A was also greater in O3-exposed versus unexposed Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

O3-induced changes in pulmonary mechanics of mice 24 hr after O3 exposure. Mice were unexposed, exposed to O3, or treated with anti–IL-13 24 hr before O3 exposure. Pressure volume (PV) curves of WT (A) and Cpefat (B) mice. The areas of the PV curves were normalized for volume A (the differences between total lung capacity and end expiratory volume, i.e., the height of the PV curves) (C), baseline values for airway resistance (Rn) (D), the coefficient of lung tissue damping, G (E), and the coefficient of lung tissue elastance, H (F). Values shown are mean ± SE of data from 6–9 mice in each group. *p < 0.05, compared with unexposed genotype-matched mice. **p < 0.05, compared with TNFR2 genotype-matched lean mice with the same exposure. #p < 0.05, compared with O3-exposed genotype-matched mice not treated with anti–IL-13.

Even in unexposed mice, baseline Rn, G, and H were elevated in the lungs of obese mice (Figure 1D,E,F). O3 exposure had no effect on Rn in mice of any genotype, but O3 exposure increased baseline G and H in Cpefat mice (Figure 1D,E,F). In contrast, no significant changes in baseline G and H were observed in O3-exposed versus unexposed Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice.

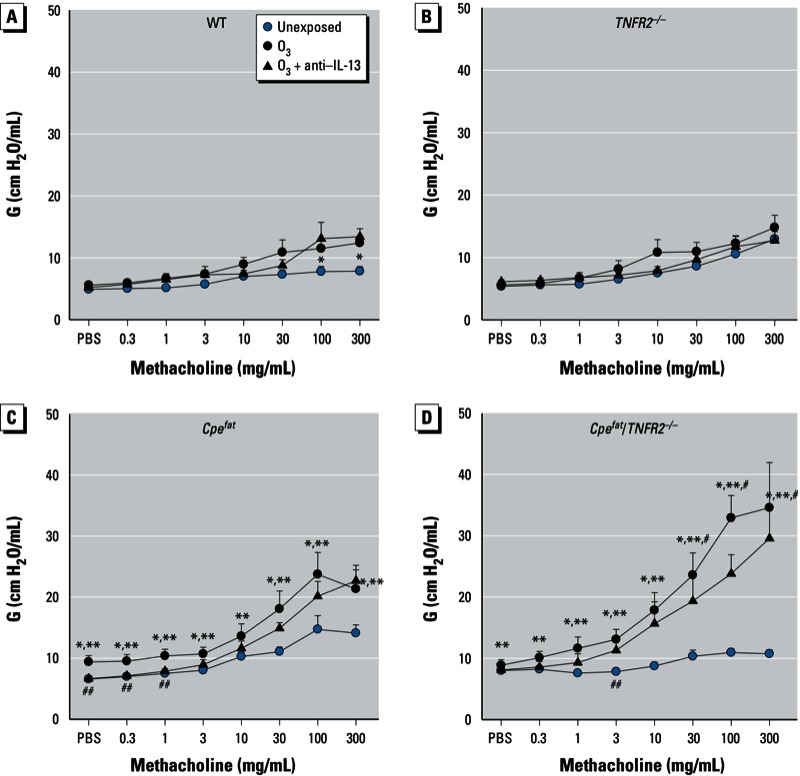

Airway responsiveness was greater in unexposed Cpefat versus WT mice, and this difference was abolished by TNFR2 deficiency (see Williams et al. 2012). In lean WT mice, O3 exposure caused AHR (Figure 2A). This effect of O3 was observed when G, a measure of the lung tissue response, was used as the outcome indicator (Figure 2A). A similar trend was observed for H, but did not reach statistical significance [see Supplemental Material, Figure S1 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205880)]. There was no effect of O3 on methacholine-induced changes in Rn (see Supplemental Material, Figure S1A). O3-induced AHR was absent in TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 2B). O3 did cause AHR in Cpefat mice (Figure 2C), and the magnitude of the O3-induced AHR was significantly greater than in WT mice. O3 also induced AHR in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 2D). Indeed, O3-induced AHR was actually greater in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– than in Cpefat mice, and O3-induced AHR was observed even when changes in Rn were used as the outcome indicator, whereas this was not the case in mice of any other genotype (see Supplemental Material, Figure S1D). O3-induced AHR was also observed in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– and Cpefat mice when H was used as the index of response, and AHR based on changes in H was also greater in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– than in Cpefat mice (see Supplemental Material, Figure S1G,H).

Figure 2.

Airway responsiveness of mice 24 hr after exposure. Mice were unexposed, exposed to O3, or treated with anti–IL-13 24 hr before O3 exposure. Methacholine-induced changes in G, a measure of the lung tissue response in WT (A), TNFR2–/– (B), Cpefat (C), and Cpefat/TNFR2–/– (D) mice. Values shown are mean + SE of data from 6–9 mice per group. *p < 0.05, O3-exposed compared with unexposed genotype-matched mice. **p < 0.05, compared with TNFR2 genotype-matched mice with the same exposure. #p < 0.05, compared with obesity-matched TNFR2-sufficient mice with the same O3 exposure. ##p < 0.05, compared with O3-exposed genotype-matched mice not treated with anti–IL-13.

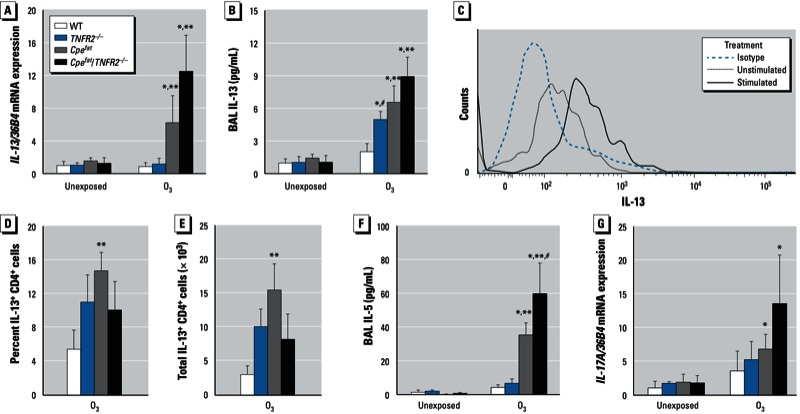

Because IL-13 has been shown to contribute to O3-induced AHR in lean BALB/c mice (Pichavant et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2008), we determined whether there were obesity- and/or TNFR2-dependent differences in IL-13 expression. O3 caused an increase in IL-13 mRNA in obese but not lean mice (Figure 3A). There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased IL-13 mRNA expression in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– versus Cpefat mice. O3 exposure also increased BAL IL-13 in Cpefat but not WT mice (Figure 3B). Furthermore, both the percentage and the total number of IL-13–expressing CD4+ cells were higher in Cpefat than WT mice exposed to O3 (Figure 3D,E). Consequently, we also measured BAL concentrations of another Th2 cytokine, IL-5. O3-induced increases in IL-5 were significantly greater in obese versus lean mice, and TNFR2 deficiency significantly increased BAL IL-5 levels in obese but not lean mice (Figure 3F), consistent with the trend observed for IL-13 (Figure 3B). IL-17A has also been linked to AHR (Kudo et al. 2012). O3 exposure caused a significant increase in IL-17A mRNA in obese but not lean mice (Figure 3G). There was a nonsignificant trend toward greater IL-17A in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– than Cpefat mice.

Figure 3.

IL-13 mRNA expression in lungs (A) and IL-13 concentration in BAL (B) from mice that were either unexposed or exposed to O3. Example of flow cytometry data from one Cpefat mouse (C) showing histograms of CD4+ lung cells stained with isotype control antibody or stained with anti–IL-13 and either unstimulated or stimulated with PMA (10 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL) for 5 hr to induce cytokine expression. Shown also are the percentages (D) and total number (E) of PMA and ionomycin stimulated CD4+ cells isolated from lungs of O3-exposed mice that expressed IL-13. BAL IL-5 concentrations (F) and IL-17A mRNA expression (G) in unexposed and O3-exposed mice. Values shown are mean ± SE of data from 4–8 mice per group. Results for IL-13 and IL-17A mRNA are normalized to 36B4 expression. *p < 0.05, compared with unexposed genotype-matched mice. **p < 0.05, compared with TNFR2 genotype-matched lean mice with the same exposure. #p < 0.05, compared with obesity-matched TNFR2-sufficient mice with the same O3 exposure.

To examine the functional impact of this IL-13 expression, we treated mice with antibodies to IL-13. In WT mice, there was no effect of anti–IL-13 treatment, likely because pulmonary IL-13 was negligible in these mice (Figure 3A,B). In Cpefat mice, anti–IL-13 treatment reversed the effects of O3 exposure on the PV curve (Figure 1B,C), and it prevented the O3-induced increase in baseline G and H (Figure 1 E,F) but did not affect O3-induced AHR (Figure 2C). In Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice, anti–IL-13 treatment also prevented O3-induced changes in the PV curve (Figure 1C) but had no effect on baseline pulmonary mechanics or O3-induced AHR (Figure 2D).

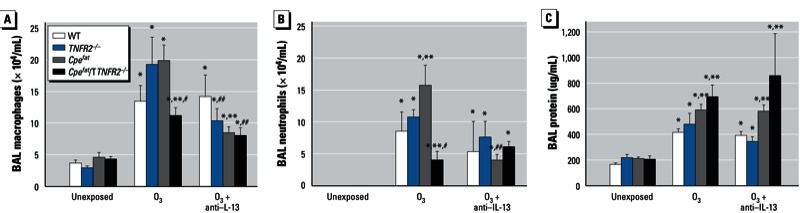

Pulmonary inflammation and injury. O3 exposure significantly increased BAL macrophages, neutrophils, and protein [a marker of O3-induced injury (Bhalla 1999)] (Figure 4). Lymphocytes and eosinophils were not observed in BAL fluid of most mice regardless of exposure, genotype, or obesity status. BAL neutrophils and protein were increased in Cpefat versus WT mice exposed to O3 (Figure 4). In lean mice, TNFR2 deficiency had no effect on these responses to O3. However, in obese mice, BAL neutrophils and macrophages, but not BAL protein, were significantly reduced in TNFR2-deficient versus -sufficient mice (Figure 4). The TNFR2-dependent changes in neutrophil recruitment were not the result of differences in the expression of IL-6, KC (keratinocyte chemoattractant), or G-CSF (granulocyte colony stimulating factor) [Figure 5A; see also Supplemental Material, Figure S2 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205880)], cytokines and chemokines reported to be important for O3-induced neutrophil recruitment to the lungs (Johnston et al. 2005a, 2005b; Kasahara et al. 2012). These chemokines were greater in O3-exposed obese versus lean mice, but they were either not affected (i.e., IL-6 and KC) or actually augmented (i.e., G-CSF) by TNFR2 deficiency in obese mice. Similarly, TNFR2-dependent changes in macrophage recruitment are not the result of changes in MCP-1, a chemokine required for O3-induced macrophage recruitment (Zhao et al. 1998). BAL MCP-1 was greater in obese versus lean mice, but TNFR2 deficiency had no effect on BAL MCP-1 (Figure 5B). Surprisingly, O3-induced increases in BAL TNFα were significantly reduced in obese versus lean mice (Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

Macrophages (A), neutrophils (B), and protein (C) in BAL from mice that were unexposed, exposed to O3, or treated with anti–IL-13 24 hr before O3 exposure. Values shown are mean ± SE of data from 4–9 mice per group. *p < 0.05, compared with unexposed genotype-matched mice. **p < 0.05, compared with TNFR2 genotype-matched lean mice with the same exposure. #p < 0.05, compared with obesity-matched TNFR2-sufficient mice with the same O3 exposure. ##p < 0.05, compared with O3-exposed genotype-matched mice not treated with anti–IL-13.

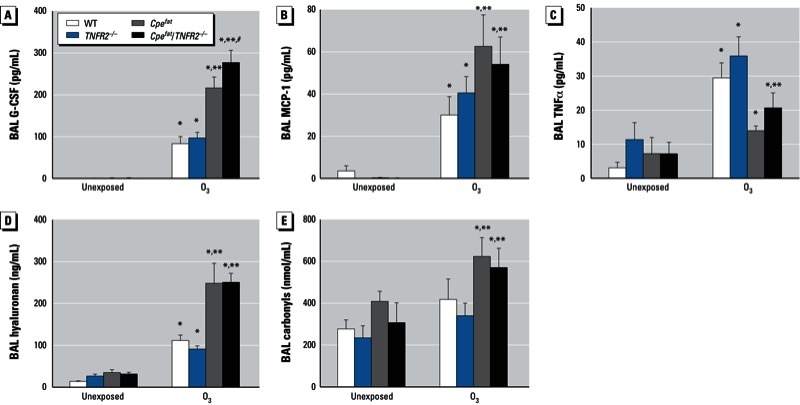

Figure 5.

BAL G-CSF (A), MCP-1 (B), TNFα (C) hyaluronan (D), protein carbonyls (E) from mice that were either unexposed or exposed to O3. Values shown are mean ± SE of data from 4–10 mice per group. *p < 0.05, compared with unexposed genotype-matched mice. **p < 0.05, compared with TNFR2 genotype-matched lean mice with the same exposure. #p < 0.05, compared with obesity-matched TNFR2-sufficient mice with the same O3 exposure.

O3 induces fragmentation of the matrix glycoprotein, hyaluronan, leading to AHR (Garantziotis et al. 2009). Such hyaluronan fragments are thought to be induced via oxidative stress caused by O3. O3 exposure caused an increase in BAL hyaluronan (Figure 5D) as well as protein carbonyls (Figure 5E), a marker of oxidative stress, although protein carbonyls were only increased in obese and not lean mice. Furthermore, O3-induced increases in BAL hyaluronan and protein carbonyls were significantly greater in obese than lean mice (Figure 5D,E), suggesting that elevations in BAL hyaluronan may contribute to greater O3-induced AHR in obese versus lean mice. However, BAL hyaluronan does not appear to account for the greater O3-induced AHR in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– versus Cpefat because BAL hyaluronan was not different in these two strains (Figure 5D).

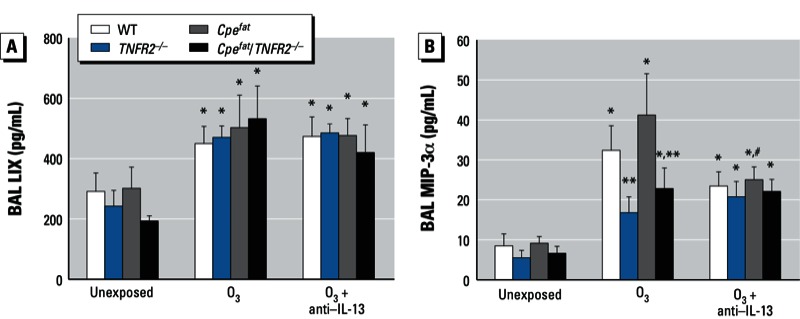

In Cpefat mice, anti–IL-13 treatment reduced O3-induced increases in BAL neutrophils and macrophages (Figure 4A,B), but not BAL protein (Figure 4C), whereas there was no effect of anti–IL-13 treatment in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 4A,B). O3-induced increases in MIP-3α (CCL20; macrophage inflammatory protein 3 α) and LIX (CXCL5; lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine) mRNA are reduced in IL-13–deficient versus WT BALB/c mice, suggesting that changes in these chemokines may contribute to the effects of IL-13 deficiency on inflammatory cell recruitment (Williams et al. 2008). O3-induced increases in BAL LIX, a neutrophil chemotactic factor, were not affected by obesity, TNFR2 deficiency, or anti–IL-13 treatment (Figure 6A) indicating that this chemokine does not account for the observed effects on BAL neutrophils (Figure 4B). However, TNFR2 deficiency did attenuate O3-induced increases in MIP-3α regardless of obesity status (p < 0.001) (Figure 6B). Anti–IL-13 also caused a significant reduction in MIP-3α in TNFR2-sufficient (p < 0.01) but not -deficient mice (Figure 6B), suggesting that IL-13 and TNFα synergize in the induction of MIP-3α after O3 exposure.

Figure 6.

BAL LIX (A) and MIP-3α (B) from mice that were unexposed, exposed to O3, or treated with anti–IL-13 24 hr before O3 exposure. Values shown are mean ± SE of data from 5–8 mice per group. *p < 0.05, compared with unexposed genotype-matched mice. **p < 0.05, compared with obesity-matched TNFR2-sufficient mice with the same O3 exposure. #p < 0.05, compared with O3-exposed genotype-matched mice not treated with anti–IL-13.

Discussion

We observed greater effects of acute O3 exposure in obese versus lean mice consistent with previous observations (Johnston et al. 2006; Shore et al. 2003). Importantly, our results also indicated obesity-related differences in the mechanisms governing the pulmonary effects of O3 (see Table 1 for summary). In lean mice, TNFR2 deficiency reduced O3-induced AHR but had no effect on O3-induced inflammation; whereas in obese mice, TNFR2 deficiency enhanced O3-induced AHR while attenuating O3-induced inflammation (Figures 2,4). In lean mice, IL-13 was not induced by O3, and there was no impact of anti–IL-13 treatment on responses to O3. However, in obese mice, O3 did induce IL-13 expression (Figure 3). Importantly, obesity-related differences in IL-13 expression accounted for the ability of O3 to induce changes in the PV curve of lung and to increase baseline G and H in obese Cpefat but not lean WT mice (Figure 1). IL-13 also contributed to the greater recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lungs of Cpefat versus WT mice (Figure 4). Moreover, in obese mice, IL-13 and TNFR2 appeared to synergize to exacerbate O3-induced inflammation and changes in pulmonary mechanics because anti–IL-13 treatment reduced inflammatory cell recruitment and G and H in TNFR2-sufficient but not -deficient Cpefat mice (Figure 4). MIP-3α expression may have contributed to the TNFR2/IL-13 synergy that promoted inflammatory cell recruitment because TNFR2 deficiency attenuated O3-induced increases in BAL MIP3α in untreated mice but not in mice treated with anti–IL-13 (Figure 6). Thus, obesity-related differences in the induction of IL-13 after O3 exposure not only confer unique and/or augmented responses to O3 on the obese mice, but they also appear to account for some of the obesity-related differences in the impact of TNFR2 deficiency in obese mice because TNFR2 can synergize with IL-13 in obese but not lean mice.

Table 1.

Effect of IL-13 blockade or TNFR2 deficiency on O3-induced increases in airway responsiveness, BAL neutrophil numbers, and pulmonary mechanics in lean and obese mice.

| Intervention | Lean mice | Obese mice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airway responsiveness | BAL neutrophils | Pulmonary mechanics | Airway responsiveness | BAL neutrophils | Pulmonary mechanics | |

| IL-13 blockade | No change | No change | No change | No change | Decrease | Decrease |

| TNFR2 deficiency | Decrease | No change | No change | Increase | Decrease | Decrease |

| Outcomes (no change, increase, decrease) indicate the qualitative change in the response to O3 relative to the absence of IL-13 blockade or TNFR2 deficiency. | ||||||

Our results demonstrating O3-induced AHR in WT but not TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 2) confirm previous reports indicating that TNFR2 is required for O3-induced AHR in lean mice (Cho et al. 2001; Shore et al. 2001). Circulating TNFα is increased in obese versus lean mice and the innate AHR characteristic of obese mice is reduced when these mice are TNFR2 deficient (Williams et al. 2012) (the unexposed mice in Figure 2C,D). Hence, we expected that TNFR2 deficiency might also attenuate O3-induced AHR in obese mice and might even ablate obesity-related differences in the impact of O3 on AHR. We did observe a reduction in O3-induced changes in baseline pulmonary mechanics in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– versus Cpefat mice (Figure 1E,F). However, O3-induced AHR was actually greater in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– versus Cpefat mice (Figure 2). This greater O3-induced AHR was not the result of greater obesity in the Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice: Body mass was the same in the two groups. O3-induced increases in BAL TNFα were lower in Cpefat versus WT mice (Figure 5C). While this reduction might explain a reduced impact of TNFR2 deficiency in obese mice, it cannot explain the observed reversal in the direction of the impact of TNFR2 deficiency on O3-induced AHR.

Because others have reported reduced O3-induced AHR in lean IL-13–/– versus WT BALB/c mice and greater O3-induced AHR in IL-13 transgenic mice (Pichavant et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2008), we examined the role of IL-13 in O3-induced AHR in obese mice. O3 caused a significant increase in pulmonary IL-13 mRNA expression and BAL IL-13 in Cpefat but not WT mice (Figure 3A,B). CD4+ T cells appeared to be the source of this IL-13 (Figure 3C-E), and another CD4+ T-cell–derived cytokine, IL-5, was also induced by O3 exposure in obese mice (Figure 3F).

To determine whether IL-13 contributed to obesity- and/or TNFR2-dependent changes in the response to O3, we treated mice with anti–IL-13 before O3 exposure. Anti–IL-13 attenuated the O3-induced increase in the hysteresis of the PV curve that was induced by O3 exposure in obese mice (Figure 1B,C). Lung surfactant is important in limiting lung hysteresis and IL-13 reduces the pulmonary expression of surfactant protein C (Ito and Mason 2010), which is important for the surface activity of surfactant. Coupled with the observations that O3-induced changes in lung hysteresis were not observed in WT mice (Figure 1A,C), which lacked IL-13 (Figure 3), the results suggest that O3 caused changes in pulmonary surfactant activity in Cpefat mice and that these changes were mediated by IL-13. Changes in lung hysteresis in obese mice may be aggravated by the ability of O3 exposure to cause oxidation of phospholipids important for surfactant activity (Pulfer and Murphy 2004). O3-induced changes in baseline G and H, measures of the lung tissue, were also ablated by anti–IL-13 treatment (Figure 1). Thus obesity-related differences in the ability of O3 to induce IL-13 expression (Figure 3) appear to account for the ability of O3 to induce changes in baseline pulmonary mechanics in Cpefat but not WT mice. TNFR2 deficiency also reduced O3-induced changes in pulmonary mechanics in Cpefat mice, and anti–IL-13 treatment had no effect on mechanics in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 1), suggesting that synergy between IL-13 and TNFR2 contributes to these changes.

In contrast to the effects on baseline pulmonary mechanics (Figure 1), we observed no effect of anti–IL-13 treatment on O3-induced AHR in Cpefat mice (Figure 2C), nor was there any effect on AHR in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 2D), indicating that the enhanced AHR in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice was not the result of increased IL-13 signaling. Thus, other factors must account for obesity-related increases in O3-induced AHR and for the augmented AHR observed in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice. IL-5 can induce AHR even in the absence of eosinophils (Borchers et al. 2001) (eosinophils were not observed in these animals). IL-5 was augmented in O3-exposed Cpefat versus WT mice and further augmented in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice (Figure 3F), consistent with the changes in AHR (Figure 2). IL-17A can also induce AHR (Kudo et al. 2012). IL-17A was expressed after O3 exposure (Figure 3G), especially in the obese mice, and could also contribute to the augmented O3-induced AHR observed in these mice (Figure 2).

In lean mice, TNFR2 deficiency had no effect on O3-induced inflammatory cell recruitment (Figure 4), consistent with previous observations (Cho et al. 2001; Shore et al. 2001). In contrast, in obese mice, TNFR2 deficiency reduced O3-induced neutrophil and macrophage recruitment and ablated obesity-related differences in these outcomes (Figure 4). Anti–IL-13 treatment also had no effect on O3-induced inflammation in lean WT mice, which lacked IL-13 (Figure 3A,B), but anti–IL-13 treatment significantly reduced O3-induced inflammatory cell recruitment in obese Cpefat mice (Figure 4A,B). A similar reduction in O3-induced inflammation occurs in lean IL-13–deficient BALB/c mice (Williams et al. 2008), which are more Th2 prone than the C57BL/6 mice used in the present study. Importantly, in obese mice, TNFR2 and IL-13 appeared to interact to promote inflammatory cell recruitment because anti–IL-13 treatment had no effect on BAL neutrophils or macrophages in Cpefat/TNFR2–/– mice even though these mice had at least as much IL-13 expression as Cpefat mice (Figure 4A,B). This interaction may occur at the level of MIP-3α expression. In obese Cpefat mice, both TNFR2 deficiency and anti–IL-13 treatment resulted in a significant decrease in BAL MIP-3α (Figure 6B), consistent with observations of others that TNFα and IL-13 can both induce the expression of MIP-3α in airway epithelial cells (Reibman et al. 2003). Importantly, anti–IL-13 treatment inhibited MIP-3α expression in TNFR2-sufficient but not -deficient Cpefat mice (Figure 6B). Dendritic cells and T cells typically express CCR6, the receptor for MIP-3α, but neutrophils can be induced to express CCR6 in the presence of TNFα (Yamashiro et al. 2000). In addition, MIP-3α can induce migration of IL-17A expressing cells that may contribute to neutrophil recruitment (Li et al. 2011). IL-17A was induced by O3 (Figure 3G).

O3-induced changes in lung function (i.e., G and H) and cellular inflammation occurred in concert (Table 1). O3-induced increases in BAL neutrophils and in both G and H were greater in Cpefat versus WT mice. Furthermore, both TNFR2 deficiency and anti–IL-13 treatment reduced O3-induced changes in G and H as well as BAL neutrophil numbers in obese mice (Table 1). The results suggest that effects of O3 on lung function and inflammation may be mechanistically related. In contrast, O3-induced AHR and inflammation were dissociated. For example, TNFR2 deficiency and anti–IL-13 treatment either augmented or had no effect on O3-induced mice, but they attenuated O3-induced inflammation in obese mice.

Two technical issues require consideration. First, obese mice have a slightly higher minute ventilation (Shore and Johnston 2006) and consequently a slightly higher inhaled dose of O3. Their lungs are also smaller (Williams et al. 2012), so the dose per gram of lung tissue may be higher. We do not think this issue contributed substantially to the outcome because neither TNFR2 deficiency nor anti–IL-13 treatment had any effect on lung volume (data not shown), but both reduced the augmented effects of O3 on BAL cells and pulmonary mechanics in obese mice. Second, we used the same volume of fluid for lavage in obese and lean mice. Because the lungs of the obese mice were smaller and presumably had correspondingly less lung lining fluid, there should have been greater dilution of substances in that lining fluid and thus lower concentrations of BAL moieties in the obese than the lean mice. In fact, the opposite was true for most BAL cytokines/chemokines examined [Figures 3,5,6; see also Supplemental Material, Figure S2 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205880)]. Thus, issues related to normalization of the BAL procedure are unlikely to explain the observed results.

Conclusions

Our results indicate differences in the mechanisms regulating pulmonary responses to O3 in lean and obese mice. In particular, TNFR2 deficiency had opposing effects on O3-induced AHR in lean and obese mice. In addition, O3 increased the pulmonary expression of IL-13 in obese but not lean mice, and this IL-13 appeared to account for the augmented ability of O3 to induce changes in pulmonary mechanics and inflammation in obese mice via synergistic effects with TNFR2. The majority of the population of the United States is either obese or overweight. Our results emphasize the need for improved understanding of the effects of O3 in this population.

Supplemental Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants ES-013307, HL-084044, and ES-000002.

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

- Alexeeff SE, Litonjua AA, Suh H, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Schwartz J. Ozone exposure and lung function: effect modified by obesity and airways hyperresponsiveness in the VA Normative Aging Study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1890–1897. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexis N, Urch B, Tarlo S, Corey P, Pengelly D, O’Byrne P, et al. Cyclooxygenase metabolites play a different role in ozone-induced pulmonary function decline in asthmatics compared to normals. Inhal Toxicol. 2000;12(12):1205–1224. doi: 10.1080/08958370050198548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett WD, Hazucha MJ, Folinsbee LJ, Bromberg PA, Kissling GE, London SJ. Acute pulmonary function response to ozone in young adults as a function of body mass index. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19(14):1147–1154. doi: 10.1080/08958370701665475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla DK. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and mucosal barrier disruption: toxicology, mechanisms, and implications. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 1999;2(1):31–86. doi: 10.1080/109374099281232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers MT, Crosby J, Justice P, Farmer S, Hines E, Lee JJ, et al. Intrinsic AHR in IL-5 transgenic mice is dependent on CD4+ cells and CD49d-mediated signaling. Am J Physiol. 2001;281(3):L653–L659. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Giner F, Kogevinas M, Imboden M, de Cid R, Jarvis D, Machler M, et al. Joint effect of obesity and TNFA variability on asthma: two international cohort studies. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1003–1009. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00140608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HY, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and hyperreactivity are mediated via tumor necrosis factor-α receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280(3):L537–L546. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.3.L537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauroux B, Sampil M, Quenel P, Lemoullec Y. Ozone: a trigger for hospital pediatric asthma emergency room visits. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;30(1):41–46. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200007)30:1<41::aid-ppul7>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, Kimata K, Zhuo L, Morgan DL, et al. Hyaluronan mediates ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(17):11309–11317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802400200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Gent JF, Triche EW, Holford TR, Belanger K, Bracken MB, Beckett WS, et al. Association of low-level ozone and fine particles with respiratory symptoms in children with asthma. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1859–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, Venkayya R, Brombacher F, Rennick DM, et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998;282(5397):2261–2263. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Mason RJ.2010The effect of interleukin-13 (IL-13) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) on expression of surfactant proteins in adult human alveolar type II cells in vitro. Respir Res 11157; 10.1186/1465-9921-11-157[Online 10 November 2010] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RA, Mizgerd JP, Shore SA. CXCR2 is essential for maximal neutrophil recruitment and methacholine responsiveness after ozone exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005a;288(1):L61–L67. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00101.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RA, Schwartzman IN, Flynt L, Shore SA. Role of interleukin-6 in murine airway responses to ozone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005b;288(2):L390–L397. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00007.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RA, Theman TA, Shore SA. Augmented responses to ozone in obese carboxypeptidase E-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R126–R133. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00306.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RA, Zhu M, Hernandez CB, Williams ES, Shore SA. Onset of obesity in carboxypeptidase E-deficient mice and effect on airway responsiveness and pulmonary responses to ozone. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(6):1812–1819. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00784.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara DI, Kim HY, Williams AS, Verbout NG, Tran J, Si H, et al. Pulmonary inflammation induced by subacute ozone is augmented in adiponectin-deficient mice: role of IL-17A. J Immunol. 2012;188(9):4558–4567. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki A, Sumida Y, Murashima S, Murata K, Takarada Y, Ito K, et al. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α are increased in obese patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(3):859–862. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo M, Melton AC, Chen C, Engler MB, Huang KE, Ren X, et al. IL-17A produced by αβ T cells drives airway hyper-responsiveness in mice and enhances mouse and human airway smooth muscle contraction. Nat Med. 2012;18(4):547–554. doi: 10.1038/nm.2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibel RL, Chung WK, Chua SC., Jr The molecular genetics of rodent single gene obesities. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(51):31937–31940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Burns AR, Miller SB, Smith CW. CCL20, γδ T cells, and IL-22 in corneal epithelial healing. FASEB J. 2011;25(8):2659–2668. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-184804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara S, Takeda K, Jin N, Okamoto M, Matsuda H, Shiraishi Y, et al. Vγ1+ T cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40(4):454–463. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0346OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2010. Final Review. 2012. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hpdata2010/hp2010_final_review.pdf [accessed 13 February 2013]

- Naude PJ, den Boer JA, Luiten PG, Eisel UL. Tumor necrosis factor receptor cross-talk. FEBS J. 2011;278(6):888–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichavant M, Goya S, Meyer EH, Johnston RA, Kim HY, Matangkasombut P, et al. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. J Exp Med. 2008;205(2):385–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulfer MK, Murphy RC. Formation of biologically active oxysterols during ozonolysis of cholesterol present in lung surfactant. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(25):26331–26338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reibman J, Hsu Y, Chen LC, Bleck B, Gordon T. Airway epithelial cells release MIP-3α/CCL20 in response to cytokines and ambient particulate matter. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28(6):648–654. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0095OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SA, Johnston RA. Obesity and asthma. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110(1):83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SA, Rivera-Sanchez YM, Schwartzman IN, Johnston RA. Responses to ozone are increased in obese mice. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(3):938–945. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00336.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SA, Schwartzman IN, Le Blanc B, Murthy GG, Doerschuk CM. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 contributes to ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(4):602–607. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SA, Williams ES, Chen L, Benedito LA, Kasahara DI, Zhu M. Impact of aging on pulmonary responses to acute ozone exposure in mice: role of TNFR1. Inhal Toxicol. 2011;23(14):878–888. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.622316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AS, Chen L, Kasahara DI, Si H, Wurmbrand AP, Shore SA.2012Obesity and airway responsiveness: role of TNFR2. Pulm Pharmacol Ther; doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2012.05.001[Online 11 May 2012] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AS, Nath P, Leung SY, Khorasani N, McKenzie AN, Adcock IM, et al. Modulation of ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation by interleukin-13. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(3):571–578. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00121607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, et al. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282(5397):2258–2261. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro S, Wang JM, Yang D, Gong WH, Kamohara H, Yoshimura T. Expression of CCR6 and CD83 by cytokine-activated human neutrophils. Blood. 2000;96(12):3958–3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang IA, Holz O, Jorres RA, Magnussen H, Barton SJ, Rodriguez S, et al. Association of tumor necrosis factor-α polymorphisms and ozone-induced change in lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):171–176. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-194OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Simpson LG, Driscoll KE, Leikauf GD. Chemokine regulation of ozone-induced neutrophil and monocyte inflammation. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(1 Pt 1):L39–L46. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.1.L39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.