Abstract

We performed a systematic review of literature on violence and related health concerns among asylum seekers in high-income host countries. We extracted data from 23 peer-reviewed studies.

Prevalence of torture, variably defined, was above 30% across all studies. Torture history in clinic populations correlated with hunger and posttraumatic stress disorder, although in small, nonrepresentative samples. One study observed that previous exposure to interpersonal violence interacted with longer immigration detention periods, resulting in higher depression scores.

Limited evidence suggests that asylum seekers frequently experience violence and health problems, but large-scale studies are needed to inform policies and services for this vulnerable group often at the center of political debate.

AT THE END OF 2010, THE United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that 43.7 million people were displaced by conflict or persecution, including roughly 837 500 asylum seekers awaiting adjudication of refugee claims in host countries.1 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that “everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.”2(Article 14.1) Yet for many individuals, the claim process is an enormous challenge. Host countries may require stringent standards of proof, which can be difficult to obtain in the context of limited legal and forensic services.3 Figures from the UNHCR indicate that just 37% of adjudicated claims succeeded in 2009.1 Highly stressful asylum-seeking processes are thought to produce adverse mental and somatic health effects.4

Asylum seekers by definition are more likely than others to experience violence. According to the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, asylum seekers are persons petitioning for protection outside their country of origin because of a well-founded fear of being persecuted on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.5 Persecution includes abuse, ill treatment, ill usage, maltreatment, oppression, and torture. Most asylum seekers are fleeing conflict situations where rates of collective and sexual violence, torture, and homicide have been well documented.6,7 Asylum seekers may also enter into high-risk transit8 and precarious host country living situations.9,10

As detailed in the World Health Organization’s 2002 World Report on Violence and Health, violence may have serious health impacts and represents a significant public health challenge.11 Studies link gender-based violence to mental health problems such as depression, emotional distress, and suicidality, as well as to physical health problems ranging from injuries and pain syndromes to arthritis and coronary heart disease.12–18 Sexual violence increases risk for health problems, including sexually transmitted infections, vaginal bleeding, urinary tract infection, miscarriage, preterm delivery, and neonatal death.14,19,20 Studies among migrants have linked torture exposure to depression and posttraumatic stress disorder21 and political violence to poorer health-related quality of life.22 Appropriate response to numerous health concerns therefore requires systematic information about violence. Yet little is known about the epidemiology of violence exposure and related health impacts to inform host country efforts to offer screening, prevention, and treatment services to what is likely to be a highly exposed population.

High-income countries received 45% of all asylum applications in 2010. Following South Africa, which registered 180 600 new claims, the remainder of the top 5 states receiving the most applications were high-income countries. These were the United States (54 300), France (48 100), Germany (41 300), and Sweden (31 800). The largest number of claimants came from Zimbabwe (149 400), Somalia (37 500), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (35 600), and Afghanistan (33 500).1 Asylum seekers in high-income host countries may face specific forms of exclusion linked to hostile policy environments.10,23,24 Increased asylum claims in recent decades have led many wealthier countries to adopt deterrence strategies, such as extended detention, restricted health and social service access, threat of deportation, and denial of work permission.25–28 The social stress stemming from such policies is thought to raise asylum seekers' risk of adverse health outcomes over that of refugees, whose asylum claims have been accepted.29,30 Despite similar backgrounds, refugees may experience relatively greater security because of their legal residency status, work permission, and social service access, suggesting possible mediation of health outcomes by immigration status. A 2004 population-based study in the Netherlands, for instance, found that asylum seekers were significantly more likely than legal refugees to experience poor general health status, depression, and anxiety, after adjustment for various demographic characteristics.30 Evidence is required to elucidate the particular needs and vulnerabilities of asylum seekers, particularly evidence on various forms of violence.

We sought to describe evidence on violence exposures among adults seeking asylum in high-income host countries and on associated health problems. We systematically reviewed studies published since 2000 that reported quantitative findings on levels (prevalence, incidence, or mean values or scores on measurement instruments) and health correlates of violence exposure in this heterogeneous population. We departed from the conventional review goals of aggregating findings into summary measures or testing causal theories, aiming instead to characterize the state of current research on violence, asylum, and health and to inform research priorities and methodological development in this emergent field.

Because of the scant systematization of data, we describe findings while also considering and critiquing the methods used to produce them—2 goals that are often in tension. Yet negotiation of such a tension may be necessary. Assessment of what little evidence exists, whether weak or strong, may orient priority research questions, and assessment of quality concerns may elucidate methodological challenges to be overcome in future work.

METHODS

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.31 Searches comprised both exploded Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms on violence exposures, asylum status, and epidemiological study design. We developed terms iteratively by combing MeSH tree headings to reach a maximally comprehensive list of terms relating to violence and refugee status. A full list of terms appears in Appendix A (available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

We ran the search in 5 databases—MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Embase—selected as key health-related sources that together were likely to capture a comprehensive view of the field. The use of exploded MeSH headings meant that a wide range of nested terms were included. For instance, explosion of “epidemiologic methods [MeSH]” led to inclusion of almost all major epidemiological study designs and measures of prevalence or effect.

Definitions

We defined an asylum seeker as someone who has entered a host country to seek protection under the terms of the UN High Commissioner on Refugees 1951 Convention–1967 Protocol whose claim is awaiting preparation, submission, or adjudication; a refugee is a person whose petition for asylum has been accepted. Although policies differ by host countries, refugee status confers leave to remain and certain protections, generally encompassing employment permission and basic civil and social rights and services. Outcomes of asylum applications are generally binary; asylum seekers are either granted refugee status or denied.32 Some states, including the United Kingdom, allow a single round of appeals to higher tribunals on payment of a fee33; the United States requires reapplication, permitted only if circumstances affecting eligibility have changed.34

We based our concept of violence on the definition established in the World Health Organization’s 2002 World Report on Violence and Health, which identifies violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community.”11(p5) We categorized violence subtypes—including sexual violence, child sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, community violence, and collective violence—according to the same report,11 although the definitions and instruments used to specify violence varied across studies. In designing search and selection criteria, we based the concept of torture as an exposure of interest on the UN Convention Against Torture.35 However, we expected definitions of torture to vary across studies. A 2010 review by Green et al. examined more than 200 studies reporting on torture exposure and found definitions to be variable and often poorly specified, leading to differences in how torture was examined, measured, and reported.36 We therefore examined studies with diverse definitions of torture and cautiously accounted for diversity when interpreting results.

We used all definitions specifically to consider violence perpetrated against asylum seekers. Violence perpetrated by asylum seekers was not the focus of our review.

Eligibility Criteria

We reviewed abstracts and full texts of retrieved articles according to inclusion criteria that they

were peer-reviewed reports of an original study;

were published January 1, 2000, to August 30, 2011;

were written in English, French, or Portuguese;

had asylum seekers older than 15 years as the study population or a subpopulation;

were set in high-income host countries; and

reported quantitative findings on population level(s) or health correlates of physical or sexual violence.

Corresponding to inclusion criteria 1 and 6, we excluded articles if they conflated asylum seekers with refugees in study conception, presented only aggregated data for the 2 populations, or measured only forensic findings (e.g., clinical signs of torture) without epidemiological measures of violence levels or effects.

We examined adults separately from children because they experience different policies,37 migration patterns,1 and health outcomes.38,39 We excluded gray literature (not peer reviewed) to mitigate pervasive data quality issues, because social marginalization makes asylum seekers difficult to sample. The date limits reflected variation in violence levels and health correlates over time with changing social and medical contexts and an attempt to isolate recent trends. Language restrictions reflected resource constraints of the review team.

Violence levels could be reported by any appropriate epidemiological measure, including risks, rates, proportions, and mean scores on instruments. Violence–health correlations could use any common measure of association or effect (risk, rate, odds ratios, hypothesis tests of difference, or coefficients from linear regressions). Studies could use any epidemiological design appropriate to reported outcomes.

We included studies that measured violence exposures among participants’ background characteristics while pursuing other primary research questions. Including only studies principally designed to measure violence would have produced higher-quality data, critical if our aim were to produce summary estimates. However, we sought to consider what little is known in a largely neglected research area; preliminary searches indicated that narrower inclusion criteria would limit studies to almost zero. The inclusive approach therefore served to characterize what little is known about experiences of violence among asylum seekers and to assess quality issues arising from reliance on existing data sources, highlighting a need for studies attending to violence exposure as a primary research question.

Data

We extracted data on study population (age and gender distribution, top 3 countries or regions of origin), design (study type and location, notable design characteristics), sampling method, measurement instruments, violence prevalence measures, and violence–health associations.

We conducted a detailed quality appraisal of all included articles with a checklist adapted from Fowkes and Fulton40 identified through a systematic review of appraisal tools.41 We specifically assessed the quality of data on violence prevalence and health effects and not the overall quality of studies. Some studies measured violence among secondary outcomes or background characteristics, and some authors acknowledged that methodological limitations would limit the quality or generalizability of violence-related data.

We appraised the appropriateness of study design to reported outcomes; validity, reliability, and accuracy of outcome measures; analysis of confounding in measures of effect; and other potential sources of error and bias. Despite thorough appraisal of quality, we decided to include data of variable quality and to specify implications for interpretation and generalizability in our report. By offering opportunities to discuss potential biases or incompleteness related to past methods, this quality-screening approach enabled us to meet our dual goal of describing existing knowledge and supporting systematization of methods.

RESULTS

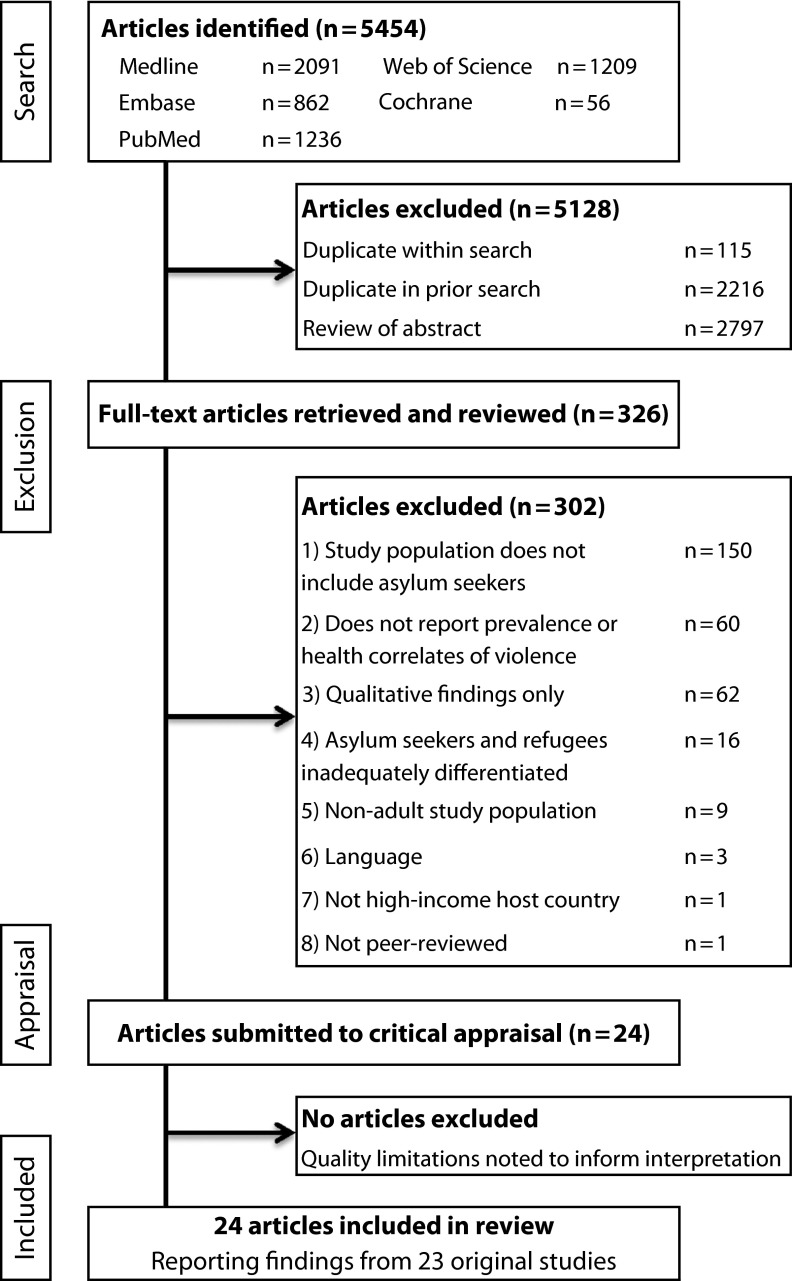

Results of the search, which returned 5454 records, appear in Figure 1. Of the 2797 studies eliminated during abstract review, most failed to meet several inclusion criteria simultaneously, most frequently presenting only qualitative findings (n = 547) or not examining asylum seekers (n = 419). Reasons for exclusion during full-text review appear in Figure 1. After screening, our review comprised 23 studies reported in 24 articles, because 1 study reported findings across 2 articles (Table 1). The most common limitation observed during quality appraisal was risk of bias attributable to convenience sampling (n = 15)42–58 (Table 2).

FIGURE 1—

Article search and screening process for asylum seekers' exposure to violence and its health effects.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of 23 Studies of Asylum Seekers' Exposure to Violence and Its Health Effects

| Characteristic | Studies, No. |

| Host country | |

| United States | 7 |

| United Kingdom | 4 |

| Netherlands | 3 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Switzerland | 2 |

| Denmark | 1 |

| Germany | 1 |

| Japan | 1 |

| Norway | 1 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| Asylum seeker origin | |

| Multiple countries/regions | 16 |

| Afghanistan | 1 |

| Americas | 1 |

| East Timor | 1 |

| Iraq | 1 |

| Kosovo | 1 |

| Turkey | 1 |

| Not reported | 1 |

| Study setting(s) | |

| Any clinic | 12 |

| Forensic clinic | 6 |

| Detention center | 6 |

| Community | 3 |

| Reception center | 2 |

| Study type | |

| Cross-sectional | 14 |

| Cohort | 4 |

| Population-based | 3 |

| Case–control | 1 |

| Randomized controlled trial | 1 |

| Sample method | |

| Convenience | 17 |

| Stratified random | 2 |

| Population study | 3 |

| Other | 1 |

| Sample size | |

| < 50 | 3 |

| 50–100 | 11 |

| 101–200 | 3 |

| 201–300 | 1 |

| > 300 | 5 |

| Asylum seekers in sample, % | |

| 100 | 19 |

| 79 | 1 |

| 68 | 1 |

| 50 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 |

| Types of violence examined | |

| Nonsexual physical | 22 |

| Torture | 16 |

| Sexual | 12 |

| Combat exposure | 4 |

| Suicide/self-harm | 7 |

| Homicide | 1 |

| Any premigration | 19 |

| Any postmigration | 6 |

| Postmigration interpersonal | 2 |

| Health correlates | |

| Any | 5 |

| Somatic health | 3 |

| Mental health | 3 |

TABLE 2—

Results of 23 Studies of Asylum Seekers' Exposure to Violence and Its Health Effects

| Study and Setting | Study Population | Study Design (Sample Design) | Violence Definition or Measure (Health Measure) | Female Gender, % (Age, Y, Mean; Range) | Asylum Seeker Origin | Violence Prevalence | Violence–Health Associations |

| Community | |||||||

| Ichikawa et al.,46 Japan | 55 adult asylum seekers served by legal NGOs | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | HTQ | 3.6 (30.2; 19–50) | Afghanistan | Torture, 67.3%; combat situation,b 80.0%; murder of family/friend, 67.3% | … |

| Laban et al.,59 Netherlandsa | 294 adult asylum seekers in government registry | Cross-sectional (random sample) | HTQ | 35.4 | Iraq | Torture, 30.6% (asylum seekers within 6 mo of arrival, 24.5%; asylum seekers with > 2 y since arrival, 36.4%; crude association, P = .026) | … |

| Laban et al.,60 Netherlandsa | 294 adult asylum seekers in government registry | Cross-sectional (random sample) | HTQ (BDQ) | 35.4 | Iraq | … | Torture not a significant predictor of physical impairment or chronic physical complaints (multiple linear regressionc) |

| Mueller et al.,50 Switzerland | 40 community-dwelling asylum seekers in government registry | Case–control (random sample, age and gender matched with 40 failed asylum seekers) | HTQ | 5.0 (32.4; 18–51) | West Asia, 40.0%; Africa, 27.5%; Europe, 15.0% (countries not specified) | Torture, 47.5% (failed asylum seekers, 30.0%); murder of family/friend, 40.0% (failed asylum seekers, 32.5%) | … |

| Reception centers | |||||||

| Jakobsen et al.,47 Norway | 65 adult asylum seekers from 5 language groups | Cross-sectional (complete sample) | HTQ | 46.9 (33) | Middle East/North Africa,45.3%; Somalia, 46.9%; Balkans, 7.8%b | Rape, 12.5%; torture/witnessed torture, 67.2%; combat situation,b 71.9% | … |

| Masmas et al.,49 Denmark | 142 newly arrived asylum seekers in contact with Amnesty International | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | IP (ICD-10) | 28.9 (32; 16–73) | WHO regions: eastern Mediterranean, 56.3%; West Pacific, 16.9%; Europe, 16.2%; Southeast Asia,14.8% | Torture, 45.1% (women, 22.0%; men, 54.5%); witnessed armed conflict, 58.5% (women, 56.1%; men, 59.4%) | Prevalence in tortured vs nontortured asylum seekers: headache, 75.0% vs 35.9%; back pain, 68.8% vs 28.2%; hearing loss/dizziness, 40.6% vs 20.5%; anxiety, 26.6% vs 3.8%; depression, 42.2% vs 10.3% |

| Goosen et al.,61 Denmark | Asylum seekers aged > 15 y, 2002–2007 (total 199 942 person-years) | Population study (data from government records of all deaths in asylum seeker centers) | … | 37.5 | UNHCR regions: Middle East/Southwest Asia, 31.1%; Central, East and Southern Europe, 26.1%; West, Central, and Southern Africa, 22.4% | Rate/100 000 person-years: suicides, 17.5 (men, 25.6; women, 4.0; age standardized RR = 7.3; 95% CI = 2.2, 23.7 ); asylum seekers vs Dutch citizens, men, RR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.37, 2.83 ; women, RR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.15, 2.07; hospitalized suicide attempts, 145.0 (men, 119.2; women, 188.2; RR = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.50, 0.77 ) | … |

| Immigration detention centers | |||||||

| Cohen,64 UK | All asylum seekers in prisons and removal centers | Population study (Home Office statistical bulletin asylum statistics 2005) | … | Among asylum seeker suicide victims, 5 | WHO regions: eastern Mediterranean, 29%; Africa, 13%; Europe, 12% | Suicides/100 000 among asylum seekers in reception centers and prisons, 1997–2005, 112.5; estimated self-harm risk among asylum seekers in centers, 2005–2006, 12.8% | … |

| Keller et al.48 US | 70 asylum seekers in NY, NJ, and PA | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | HTQ | 20.0 (28; 15–52) | Africa, 77.1%; eastern Europe, 10.0%; Asia, 6.0%b | Torture, 74.3%; murder of family/friend, 58.6%; sexual assault,b 25.7% | … |

| Robjant et al.,54 UK | 67 asylum seekers in immigration removal centers and 49 community-dwelling asylum seekers | Cross-sectional (convenience samples) | PDS (HADS and IES-R) | 32.8 (32; 18–66) | 43 Source countries, not specified | Torture, 30.2%; nonsexual violent assault,b 37.9%; by known assailant, 9.5%; sexual assault,b 15.5%; by known assailant, 5.2%; childhood sexual abuse, 7.8% | Interaction between interpersonal trauma and detention duration on depression, P = .02; mean scores (SD) on measures of anxiety, 14.3 (4.5) vs 12.6 (5.5); PTSD, 71.0 (15.4) vs 63.6 (26.5) for detainees with vs without interpersonal trauma |

| Steel et al.,58 Australia | 14 adult asylum seekers from single ethnic group | Cross-sectiona (complete sample) | Study questionnaire | 64.3 (28–44) | … | Assaultsb by detention staff: physical violence, 85.7%; sexual harassment, 35.7%; violent threats, 92.9%; assaults by other detainees: sexual harassment, 42.9% | … |

| van Oostrum et al.,63 Netherlands | All asylum seekers detained in 2002–2005 (222 217 person-years) | Population-based study (data from death notifications) | … | 39.5 | Among deaths: Africa, 33%; Asia, 34%; Europe, 28%b | Rates/100 000 person-years (SMR vs Dutch citizens): suicide: men, 16.38 (SMR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.02, 2.46); women, 3.41 (0.90; 95% CI = 0.19, 2.63); homicide: men, 3.72 (2.13; 95% CI = 0.95, 5.55); women, 3.41 (4.01; 95% CI = 0.83, 11.69) | … |

| Clinics | |||||||

| Asgary et al.,42 US | 89 asylum seekers torture victims in forensic clinic | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | IP | 13.5 (34; 18–59) | WHO regions: Africa, 39.5%; Europe, 12.1%; Southeast Asia, 24.6% | Sexual torture: rape, 6.7%; genital shocks, 7.9%; fondling, 4.5%; genital cutting, 2.2% | … |

| Boersma,43 US | 21 asylum seekers in forensic clinic for torture documentation | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | IP | … | … | Torture or other physical violence,b 76.2%; by known assailant, 23.8%; sexual violence,b 38.1% | … |

| Bradley and Tawfiq.,44 UK | 97 Kurdish asylum seeker torture victims in forensic clinic | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | MFVT-UK guidelines (DSM-IV) | 3.5 (30; 16–64) | Turkey | Sexual assault, 6.2% (women, 30.0%, men, 2.4%) | Nonsignificant increase in PTSD or depression in female sexual assault victims (P = .07) |

| Edston and Olsson,45 Sweden | 63 female asylum seekers in torture clinic | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | Clinical interview | 100.0 | Africa, 47.6%; Middle East, 23.8%; Americas, 14.3%b | Physical maltreatment,b 95.2%; torture,b 76.2%; rape/sexual abuse,b 76.2% | … |

| Eisenman et al.,22 US | 24 asylum seekers in 3 community clinics in Los Angeles, CA | Retrospective cohort (weighted cluster sample) | Clinical interview | … | Americas | Political violenced: among asylum seekers, 100%; among all immigrants, 53.9% | … |

| Eytan et al.,62 Switzerland | 319 adult asylum seekers at entry medical exam | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | Clinical interview | 27.9 (24e; 15–63) | Kosovo | Personal violence,b 21.6%; violent death of relative, 10.0% | … |

| Neuner et al.,51 Germany | 32 asylum seekers with PTSD and PV history in mental health clinic | Pilot randomized controlled trial (convenience sample) | VCOV | 31.2 (31.4) | Turkey, 78%; Balkans, 13%; Africa, 9%b | Torture, 87.5%; violent assault by stranger, 62.1%; witnessed violence against family/friend, 90.6%; suicide plans/attempts, 40.6% | … |

| Piwowarczyk,52 US | 134 asylum seekers in refugee mental health clinic | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | IP | 65.7 (34; 20–66) | Africa, 82%; Europe, 5%; Asia, 5%; Middle East, 4%; Americas, 4% | Torture, 84.3%; rape/attempted rape, 50.0% | Torture history associated with PTSD (AOR = 4.93; P = .03)f; crudely associated with depression (P = .037) |

| Piwowarczyk et al.,53 US | 65 asylum seekers seen in refugee mental health clinic in Boston, MA and 30 refugees as comparison group | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | Clinical interview (food security survey) | 75.4 (33.7) | Africa, 78.5%; Europe, 10.8%; Americas, 6.1%; Middle East, 4.6% | Torture,b 86.2% (vs 56.7% of refugees; P = .002); family tortured,b 63.1% (vs 53.3% of refugees; P = .25) | Torture history associated with increased odds of postmigration hunger (AOR = 10.44; P = .032)g |

| Rogstad and Dale,55 UK | 43 asylum seekers in genitourinary clinic | Cohort (convenience sample) | Clinical interview | 48.8 (27.9; 15–56) | … | Sexual violence,b 44.2% (women, 76.2%; men, 13.6%; age- and gender-matched White British patients, 0.0%) | … |

| Sanders et al.,56 US | 58 asylum seeker torture victims in forensic clinic to document torture | Cross-sectional (convenience sample) | IP | 29.3 | Sub-Saharan Africa, 67%; southern Europe, 12%; North Africa, 10% | Any beating, 91.4%; any sexual abuse during torture, 24.1% (64.7% of women, 7.3% of men) | … |

| Silove et al.,57 Australia | 33 East Timorese asylum seekers in refugee health clinic | Cross-sectional (convenience sample, retrospective chart review) | HTQ (CIDI) | 48.4 (44; 23–67) | East Timor | Torture, 43.4%; rape/sexual violence, 26.1%; combat, 56.5%h | … |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; BDQ = Brief Disability Questionnaire; CI = confidence interval; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HTQ = Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; ICD-10 = International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; IES-R = Impact of Event Scale–Revised; IP = Istanbul Protocol; MFVT-UK = Medical Foundation for Victims of Torture–UK; NGO = nongovernmental organization; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PV =physical violence ; RR = rate ratio; SMR = age-standardized mortality ratio; UNHCR = United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees; VCOV = Vivo–Checklist of Organized Violence; WHO = World Health Organization. Ellipses indicate data not available.

Same study reported in in 2 articles.

Not defined.

Model included age, gender, psych. diagnoses, and social difficulties.

Interpersonal trauma: sexual violence and nonsexual physical violence or torture; political violence: described as “many types of violence such as war, torture, forced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings.”25(p627)

Median.

Adjusted for education, employment, current medical care, and other traumatic exposures.

Adjusted for age, gender, education, current housing, language ability, self-reported health, employment, and work authorization.

Prevalence reported among 23 of 33 participants; 10 participants not asked about traumatic exposures,

Characteristics of Studies

Studies were conducted in only 10 of the 69 high-income countries. Only 2 studies (9%) used random sampling,22,59,60 of which 1 included only 3.7% asylum seekers.22 Only 5 studies included non–asylum seeker comparison groups.22,53–55,61 Sixteen studies (70%) did not specify the gender composition of their sample or did not disaggregate findings by gender.22,42-44,46-48,50-54,57-59,60,62

Instruments.

Eleven studies (48%) used previously developed instruments to measure violence. Violence exposures were most commonly measured with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, used in 6 studies.46-48,50,57,59,60 Two studies58,60 examined violence with questionnaires adapted from a Post-migratory Living Problem Checklist developed by Silove et al.65 Two explicitly stated that they assessed torture with the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights Istanbul Protocol,42,49 whereas 1 used the Medical Foundation for Victims of Torture–UK guidelines,44 and 1 used the Vivo–Checklist of Organized Violence,51 reflecting the predicted diversity of measurement tools.36 One study developed a novel questionnaire to measure political violence.22

Scope.

Examination of premigration violence, especially torture (n = 16; 70%),42-54,56,57,59,60 predominated. Only 6 studies (26%) considered any postmigration violence.48,58,61,62,–64Of these, only 2 considered postmigration interpersonal violence, limited to violence in detention58 and incidence of homicide against asylum seekers.64 Five studies reported postmigration suicide or self-harm.48,61,62–64No study reported levels of intimate partner, domestic, community, or elder violence either before or after migration. Table 1 provides an overview of study characteristics.

Study Findings

We grouped findings by setting: community, reception center, detention center, or health clinic or hospital (Table 2). We provided separate findings for men and women only where authors reported gender-disaggregated data.

We did not report summary measures of violence exposure, because studies used almost exclusively nonrepresentative, small convenience samples of highly specific subpopulations (e.g., specific nationalities or language groups). It was thus unclear to what population a pooled prevalence estimate could apply. Furthermore, many studies specifically selected for violence victims, for instance, by examining victims of torture42–45,56 or any political violence,22 such that prevalence estimates were partly artifacts of study design. Effect measures were too scarce to pool, because no 2 studies reported on the same exposure–outcome relationship.

Any physical violence.

Six studies screened for history of any physical violence. In a clinic-based study, Eytan et al. found 21.6% exposure to past personal violence in a cross-sectional convenience sample of 319 adult Kosovar asylum seekers (27.9% female; median age = 24 years) undergoing mandatory entry medical screening in Geneva, Switzerland.62 Another 3 clinic-based studies intentionally selected violence-exposed populations (survivors of torture or political violence) such that prevalence estimates are in part artifacts of selection.22,43,45

Among studies not based in clinics, Robjant et al. found 37.9% exposure to past nonsexual violent assault in a convenience sample of 116 asylum seekers in UK communities and detention centers (32.8% female; mean age = 32 years), where 25.1% of victims knew their assailant(s) personally.54

Steel et al. found that 85.7% of a convenience sample of 14 adult asylum seekers in an Australian detention center had experienced physical assault by center officers.58 Although the small sample size and single location make the result nongeneralizable, the finding suggests the troubling possibility of victimization at the hands of agents purporting to protect asylum seekers.

Health correlates of any physical violence.

Robjant et al. found significant differences in depression (P < .001) and anxiety (P = .02) scores on psychometric instruments among asylum seekers with a history of detention versus those without, although they did not control for confounding. The study also observed an interaction effect: those exposed to interpersonal trauma (defined as sexual and nonsexual attacks by a known assailant or a stranger or previous experience of torture) and longer detention had worse depression outcomes than predicted by either exposure separately (F(1,86) = 5.97; P = .017).54

Torture.

Sixteen studies examined torture, although definitions were highly variable and often inexplicit. Only 6 studies cited explicit protocols, norms, or guidelines to define torture; 5 cited the Istanbul Protocol42,43,49,52,56 and 1 the Medical Foundation for Victims of Torture–UK guidelines.44 Seven studies defined torture implicitly through measurement instruments—6 with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire,46-48,50,57,59,60 1 the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale,54 and 1 the Vivo-Checklist of Organized Violence.51 The definition was unclear for 3 studies.44,45,53 As noted by Green et al., variable or inexplicit torture definitions may imply inconsistent measurement across studies, limiting the comparability of findings.36

Piwowarczyk observed the prevalence of torture, with a definition based on the Istanbul Protocol, as 84.3% in a convenience sample of 134 asylum seekers (65.7% female; mean age = 34 years) in a mental health clinic in Boston, Massachusetts.52 In a separate study of patients in the same clinic, Piwowarczyk et al. observed torture prevalence to be 86.2% among 65 asylum seekers (75.4% female; mean age = 33.7 years) compared to 56.7% among 30 refugees (66.7% female; mean age = 46.4 years) sampled by convenience. This prevalence difference was statistically significant (P = .002), although this could in part reflect demographic differences.53 Silove et al. reported that 10 (43.4%) of the 23 asylum seekers interviewed about traumatic experiences reported exposure to past torture, defined by the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, in a sample of 33 East Timorese refugees (48.4% female; mean age = 44 years) in a community health clinic in Australia. Ten participants were not asked about trauma history at the discretion of clinicians, almost always because such questions were deemed “too provocative,” presumably because of concerns about retraumatization.57(p458) Five clinical studies offered no useful prevalence estimates because they purposefully selected victims of torture or political violence as their study sample.22,42,43,45,56

In community-based populations, reported torture prevalence ranged from 30.6% among 294 adult Iraqi asylum seekers (35.4% female; mean age not stated) in the Netherlands59,60 to 67.3% in a convenience sample of 55 adult Afghan asylum seekers (3.6% female; mean age = 30.2 years) receiving nongovernmental organization legal services in Japan.46 Both of these studies defined torture with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire.

Offering the only gender-disaggregated findings, Masmas et al. found that 45.1% reported torture exposure, defined by the Istanbul Protocol, in a cross-sectional convenience sample of 142 detained asylum seekers (28.9% female; mean age = 32 years) in Denmark, with higher exposure among men (54.5%) than women (22.0%).49 Keller et al. reported 74.3% torture exposure among 70 detained asylum seekers (20.0% female; mean age = 28 years) in the United States, although the use of convenience sampling and unspecified definition of torture limited interpretability.48

Health correlates of torture.

Two studies of asylum seekers in a US mental health clinic observed significant adjusted health effects of reported torture. Piwowarczyk et al. observed increased odds of hunger among tortured compared with nontortured asylum seekers (odds ratio [OR] = 10.44; P = .032) after adjustment for age, gender, education, current housing and employment, language ability, self-reported health status, and work authorization.53 In a separate study, Piwowarczyk observed higher odds of posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis among tortured than nontortured asylum seekers (OR = 4.93; P = .03) after adjustment for education, employment, current medical care access, and other violent or traumatic exposures. The study also reported a crude association between torture history and depressive disorder (P = .037).52 Masmas et al. observed differential prevalence in tortured versus nontortured asylum seekers for a wide range of somatic and mental health symptoms (Table 2).49

Other studies failed to observe significant effects of torture. Bradley and Tawfiq found no crude association between violent head trauma during torture and clinician-diagnosed chronic headache (P = .687) among 97 Kurdish asylum seekers in a London, United Kingdom, forensic clinic.44 Laban et al. found that torture history, after control for confounders, was not associated with scores on the Brief Disability Questionnaire, a self-report measure of disability among 294 Iraqi asylum seekers.60

Sexual violence.

Findings on sexual violence were limited. Most studies reporting sexual violence failed to present gender-disaggregated data. We presented results separately by gender whenever available. None of the 3 community-based studies reported on sexual violence. Several studies reported prevalence levels in detention or reception center settings, but used nonrepresentative samples, did not disaggregate exposures by gender, and did not compare with host country levels or another comparison group, making results difficult to interpret.47,48,54 Clinical prevalence estimates were difficult to interpret because of highly nonrepresentative samples.43,52

Nevertheless, a few noteworthy findings emerged. In detention settings, Steel et al. found a 35.7% lifetime prevalence of sexual harassment (not further defined) by a detention officer in a small sample (14 asylum seekers) in a single setting; although by itself this finding remains somewhat anecdotal, its troubling nature suggests a need to examine possible sexual violence within host country institutions charged with protecting asylum seekers.58 Rogstad and Dale observed a 44.2% prevalence of reported sexual violence in a convenience sample of 43 asylum seekers (48.8% female) seen in a UK genitourinary clinic compared to 0.0% in an age- and gender-matched sample of 43 White British patients in the same clinic. Disaggregating findings by gender, they reported a 76.2% prevalence of sexual violence among female asylum seekers and 13.6% among male asylum seekers.55 Although specific prevalence findings from a genitourinary clinic cannot be considered broadly generalizable, the extent of difference in exposure levels may be enough to support a hypothesis that asylum-seeking women experience greater exposure to sexual violence than their male asylum-seeking or female host country counterparts.

Four studies reported prevalence of sexual torture methods—rape, sexual assault, or injury to genitalia—among torture victims, tentatively suggesting higher rates among female than male asylum seekers.42–45 Among 16 torture victims in a US forensic clinic, Boersma found a 77.8% prevalence of sexual torture among women and 14.3% among men.43 In a convenience sample of 97 tortured Turkish asylum seekers (14.4% women; mean age = 30 years) in a London forensic clinic, Bradley and Tawfiq found a 6.2% prevalence of sexual torture, with much higher levels among women (30.0%) than men (2.4%).44 Edston and Olsson reported 76.2% exposure to rape or sexual violence in a convenience sample of 63 adult female torture victims seeking asylum in Stockholm, Sweden.45 These results were limited by small study populations, convenience sampling, nonrepresentative clinic samples, and lack of comparison groups, but may nevertheless suggest widespread exposure and indicate need for further research.

Health correlates of sexual violence.

Bradley and Tawfiq found a greater prevalence of psychological problems among female Kurdish asylum seekers with a history of reported sexual abuse than among those without such history. The study included only 4 women, and the crude association between sexual abuse and psychological problems was not statistically significant (P = .071).44

Suicide or self-harm.

Three population studies reported elevated rates of suicide among some groups of asylum seekers,61,63,64 with 2 studies reporting higher age-standardized suicide rates among male asylum seekers than among female asylum seekers or male host country nationals.61,63 Reviewing 2002 to 2007 death registries from Dutch asylum seeker reception centers, Goosen et al. found a crude suicide death rate of 25.6 per 100 000 person-years among men and 4.0 among women (age-standardized rate ratio [RR] = 7.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.2, 23.7). Suicide rates were higher among male but not female asylum seekers than among Dutch nationals (for males, age-standardized RR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.37, 2.83). Hospital-treated suicide attempts per 100 000 person-years were also higher among male asylum seekers than among men in The Hague population (age-standardized RR = 1.42; 95% CI = 1.20, 1.66).61

Van Oostrum et al. also observed elevated male asylum seeker suicides in Dutch detention centers from 2002 to 2005, with a crude suicide death rate per 100 000 of 16.38 among male asylum seekers and 3.41 among female asylum seekers (age-standardized mortality ratio, in comparison with same-gender Dutch citizens, for men = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.02, 2.46; for women = 0.90; 95% CI = 0.19, 2.63).63 Cohen estimated very high 2-year suicide rates per 100 000 asylum seekers detained in UK immigration removal centers, ranging from 42 (1997–1999) to 211 (2003–2005); the UK national rate was 9 per 100 000 population (1997–2005). However, the author noted irregular death reporting, a small number of cases, and possible inclusion of detainees who were not seeking asylum.64 This study should be interpreted cautiously, but preliminary indication of elevated rates suggests a need for further research and service attention.

DISCUSSION

Despite limitations, the studies we reviewed suggested that asylum seekers have great exposure to myriad forms of violence and their health consequences. Torture—although defined in varying ways—was the most widely researched exposure. Although definitional variations complicated interpretation, prevalence of reported torture was higher than one third across research settings, with indications of higher prevalence among men.49 More comprehensive screening and data collection is warranted to document persecution and identify survivors who might require services. All studies examining suicide found higher risk among asylum-seeking men than among host populations.61,63,64 Women had higher exposure to sexual violence,42–44,55 although most studies reporting sexual violence failed to separate findings by gender.42,43,48,52,54,54,57

In studies of health effects of violence, adjusted associations were observed only for torture, with data from 2 small studies suggesting that torture could be related to increased odds of posttraumatic stress disorder52 and hunger.53 Far from indicating that violence is not associated with health impacts, the limited findings highlight the lack of systematic research on the epidemiology of violence. Longer time in detention was observed to modify (and augment) the effect of past violence on the risk of developing depression symptoms.54

Remaining Gaps in Knowledge

Currently available prevalence estimates are limited in their generalizability by nonrepresentative sampling and intentional selection of torture or political violence survivors. Methodological limitations noted here may not be weaknesses of the study but relate to various studies' aims: for many, collecting a representative sample was not the goal. The challenge for the field is to develop methodologies appropriate to gaining representative data on violence and health among this population.

Studies we reviewed emphasized collective and premigration violence, often excluding postmigration risks and offering no findings on family, intimate partner, or elder violence. Lack of data may reflect inattention to potentially ongoing risks and needs. Reports on health effects were limited and gave mostly crude associations. Little attention was given to primary care challenges—such as ongoing management of hypertension, pain syndromes, or coronary heart disease—linked to violence in existing studies, thus failing to uncover potentially unmet health needs.14,17,18 Perhaps most importantly, we were unable to consider gender as a mediator of risk or associations between violence and health because more than 75% of studies did not disaggregate any prevalence data by gender, limiting the evidence available to inform policies that might be more sensitive to women’s distinctive experiences and vulnerabilities in the asylum process.

A future review might examine both child and adult refugees and asylum seekers, disaggregating findings where possible and comparing to host population norms. In addition, search expansions could include additional databases, more expansive terms, and more publication languages. Despite these limitations, however, our findings provide a systematic, evidence-informed picture of current knowledge.

Building Evidence-Informed Policies and Services

Our findings suggest that policies and services must be designed to address the great probability that asylum seekers have been exposed to violence and often to extreme forms of violence. Data shortages indicate a need for redoubled efforts to detect and measure abuses that may occurr prior to and after an asylum seeker’s arrival in the country of refuge. Critically, information on needs and ongoing risks related to exposure must be factored into life-determining asylum decisions.

Because it is clear that states will continue to return asylum seekers—often the majority4—to their countries of origin, states have an obligation to consider health and security concerns during return procedures for those denied entry—particularly among individuals whose conditions may have been made worse by unsafe or stressful asylum processes in host countries.21,66,67 Findings on violence during immigration detention, although not surprising, are nonetheless disturbing. Studies showing that immigration detention may modify (and augment) adverse health effects of past violence54 while exposing asylum seekers to additional postmigration violence58 point to the urgent need for policy reevaluation. Persistent practices such as extended detention of children in the United States require evidentiary review.68

In services, screening, and treatment, attention must be paid to common exposures to violence, particularly sexual violence against women and torture. Voluntary sexual health screening and care programs for female and male asylum seekers are critical. Similarly, greater attention must be given to the risk of postmigration violence, with specific recognition of community, intimate partner, and family violence.69 Suicide prevention measures should be developed, especially for detained asylum-seeking men.

Conclusions

Sadly, perhaps our most robust finding is the enormous gap in policy-relevant evidence on asylum, violence, and health. Better research is urgently needed and must consider pre- and postmigration violence, better definition and documentation of exposure to torture, and better methods that lead to more generalizable results. Researchers should also go beyond this to study globally prevalent forms of gender-based violence.70

Global population displacements and host state concerns about migrant populations have spurred significant policy rhetoric about asylum seekers. However, our review makes clear that evidence to make informed decisions about this particularly vulnerable group is lacking. Fair and humane policies and services will depend on a greater understanding of the burden of violence among asylum seekers and better responses to individuals’ health needs.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed because we used only previously published data.

References

- 1.UNHCR Global Trends 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: UN High Commissioner on Refugees; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.UN General Assembly Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 1948 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lustig SL, Kureshi S, Delucchi KL, Iacopino V, Morse SC. Asylum grant rates following medical evaluations of maltreatment among political asylum applicants in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(1):7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor K. Asylum seekers, refugees, and the politics of access to health care: a UK perspective. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(567):765–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UN General Assembly Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 1951. UN Treaty Series vol. 189 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnett A, Peel M. The health of survivors of torture and organised violence. BMJ. 2001;322(7286):606–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loutan L, Bollini P, Pampallona S, Bierens de Haan D, Garazzo F. Health of refugees. Impact of trauma and torture on asylum-seekers. Eur J Public Health. 1999;9(2):93–96 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolma S, Singh S, Lohfeld L, Orbinski JJ, Mills EJ. Dangerous journey: documenting the experience of Tibetan refugees. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(11):2061–2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koser K. Asylum policies, trafficking and vulnerability. Int Migr. 2000;38(3):91–111 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart E. Exploring the vulnerability of asylum seekers in the UK. Popul Space Place. 2005;11(6):499–512 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama Met al. Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(1):79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell J, Jones A, Dienemann Jet al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1157–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vives-Cases C, Ruiz-Cantero MT, Escribà-Agüir V, Miralles JJ. The effect of intimate partner violence and other forms of violence against women on health. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(1):15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell JC, Glass N, Sharps PW, Laughon K, Bloom T. Intimate partner homicide: review and implications of research and policy. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(3):246–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plichta SB. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: policy and practice implications. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19(11):1296–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence Against Women Study Team Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;5;371(9619):1165–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johri M, Morales R, Boivin Jet al. Increased risk of miscarriage among women experiencing physical or sexual intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Guatemala City, Guatemala: cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(3):266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, Marnane C, Bryant RA, van Ommeren M. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302(5):537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenman DP, Gelberg L, Liu HH, Shapiro MF. Mental health and health-related quality of life among adult Latino primary care patients living in the United States with previous exposure to political violence. JAMA. 2003;290(5):627–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatton TJ, Williamson JG. Refugees, asylum seekers, and policy in Europe. : Langhammer RJ, Foders F, Labor Mobility and the World Economy. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2006:249–284 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zetter R, Griffiths D, Sigona N. Social capital or social exclusion? The impact of asylum-seeker dispersal on UK refugee community organizations. Community Dev J. 2005;40(2):169–181 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boswell C. European values and the asylum crisis. Int Aff. 2000;76(3):537–557 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silove D, Steel Z, Watters C. Policies of deterrence and the mental health of asylum seekers. JAMA. 2000;284(5):604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holzer T, Schneider G, Widmer T. The impact of legislative deterrence measures on the number of asylum applications in Switzerland (1986–1995). Int Migr Rev. 2000;34(4):1182–1216 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatton TJ. Seeking asylum in Europe. Econ Policy. 2004;19(38):5–62 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burnett A, Peel M. Health needs of asylum seekers and refugees. BMJ. 2001;322(7285):544–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerritsen AAM, Bramsen I, Deville Wet al. Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(1):18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff Jet al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Who We Help: Asylum-Seekers. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asylum: Appeals System. London: United Kingdom Border Agency; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asylum: Types of Asylum Decisions. Washington, DC: US Citizenship and Immigration Services; 2012. United Nations Treaty Series [Google Scholar]

- 35.UN General Assembly Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 1984:85 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green D, Rasmussen A, Rosenfeld B. Defining torture: a review of 40 years of health science research. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(4):528–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhabha J. Minors or aliens? Inconsistent state intervention and separated child asylum-seekers. Eur J Migr Law. 2001;3:283–314 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gracey M. Caring for the health and medical and emotional needs of children of migrants and asylum seekers. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93(11):1423–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bronstein I, Montgomery P. Psychological distress in refugee children: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14(1):44–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ. 1991;302(6785):1136–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JPT. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):666–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asgary RG, Metalios EE, Smith CL, Paccione GA. Evaluating asylum seekers/torture survivors in urban primary care: a collaborative approach at the Bronx Human Rights Clinic. Health Hum Rights. 2006;9(2): 164–179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boersma RR. Forensic nursing practice with asylum seekers in the USA—advocacy and international human rights: a pilot study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2003; 10(5):526–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradley L, Tawfiq N. The physical and psychological effects of torture in Kurds seeking asylum in the United Kingdom. Torture. 2006;16(1):41–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edston E, Olsson C. Female victims of torture. J Forensic Leg Med. 2007;14(6):368–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ichikawa M, Nakahara S, Wakai S. Effect of postmigration detention on mental health among Afghan asylum seekers in Japan. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006; 40(4):341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jakobsen M, Thoresen S, Eide Johansen LE. The validity of screening for post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems among asylum seekers from different countries. J Refug Stud. 2011;24(1): 171–186 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keller AS, Rosenfeld B, Trinh-Shevrin Cet al. Mental health of detained asylum seekers. Lancet. 2003;362(9397):1721–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masmas TN, Moller E, Buhmannr Cet al. Asylum seekers in Denmark—a study of health status and grade of traumatization of newly arrived asylum seekers. Torture. 2008;18(2):77–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mueller J, Schmidt M, Staeheli A, Maier T. Mental health of failed asylum seekers as compared with pending and temporarily accepted asylum seekers. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(2):184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neuner F, Kurreck S, Ruf Met al. Can asylum seekers with posttraumatic stress disorder be successfully treated? A randomized controlled pilot study. Cogn Behav Ther. 2010;39(2):81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piwowarczyk L. Asylum seekers seeking mental health services in the United States: clinical and legal implications. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(9):715–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piwowarczyk L, Keane TM, Lincoln A. Hunger: the silent epidemic among asylum seekers and resettled refugees. Int Migr. 2008;46(1):59–77 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robjant K, Robbins I, Senior V. Psychological distress amongst immigration detainees: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Br J Clin Psychol. 2009;48(pt 3): 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogstad KE, Dale H. What are the needs of asylum seekers attending an STI clinic and are they significantly different from those of British patients? Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(8):515–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanders J, Schuman MW, Marbella AM. The epidemiology of torture: a case series of 58 survivors of torture. Forensic Sci Int. 2009;189(1-3):e1–e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silove D, Coello M, Tang Ket al. Towards a researcher- advocacy model for asylum seekers: a pilot study amongst East Timorese living in Australia. Transcult Psychiatry. 2002;39(4):452–468 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steel Z, Momartin S, Bateman Cet al. Psychiatric status of asylum seeker families held for a protracted period in a remote detention centre in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(6):527–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laban CJ, Gernaat H, Komproe IH, Schreuders BA, De Jong J. Impact of a long asylum procedure on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004; 192(12):843–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laban CJ, Komproe IH, Gernaat H, de Jong J. The impact of a long asylum procedure on quality of life, disability and physical health in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(7):507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goosen S, Kunst AE, Stronks K, van Oostrum IEA, Uitenbroek DG, Kerkhof AJ. Suicide death and hospitaltreated suicidal behaviour in asylum seekers in the Netherlands: a national registry-based study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eytan A, Bischoff A, Rrustemi Iet al. Screening of mental disorders in asylum-seekers from Kosovo. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(4):499–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen J. Safe in our hands?: a study of suicide and self-harm in asylum seekers. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008; 15(4):235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Silove D, Sinnerbrink I, Field A, Manicavasagar V, Steel Z. Anxiety, depression and PTSD in asylum-seekers: assocations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stressors. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170(4):351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Oostrum IEA, Goosen S, Uitenbroek DG, Koppenaal H, Stronks K. Mortality and causes of death among asylum seekers in the Netherlands, 2002-2005. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011; 65(4):376–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hallas P, Hansen AR, Staehr MA, Munk-Andersen E, Jorgensen HL. Length of stay in asylum centres and mental health in asylum seekers: a retrospective study from Denmark. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robjant K, Hassan R, Katona C. Mental health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(4):306–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dyer C. Fast track deportation without access to legal counsel is illegal. BMJ. 2010;341:c4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Charter of Rights for Women Seeking Asylum. London, UK: Asylum Aid; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH, WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women Study Team Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]