Abstract

In Sri Lanka, women do not have access to legal abortion except under life-saving circumstances. Clandestine abortion services are, however, available and quite accessible.

Although safe specialist services are available to women who can afford them, others access services under unsafe and exploitative conditions. At the time of this writing, a draft bill that will legalize abortion in instances of rape, incest, and fetal abnormalities awaits approval, amid opposition.

In this article, I explore the current push for legal reform as a solution to unsafe abortion. Although a welcome effort, this amendment alone will be insufficient to address the public health consequences of unsafe abortion in Sri Lanka because most women seek abortions for other reasons. Much broader legal and policy reform will be required.

IN DECEMBER 2011, THE abortion debate in Sri Lanka took off once again when the Minister of Child Development and Women’s Affairs, Tissa Karaliyadda, raised the need for abortion law reform in parliament.1 The existing law, a legacy of colonial rule, permits abortion only to save a woman’s life. 2 This archaic piece of legislation has not been revised since 1883.3 The proposed amendment will make abortion legal in instances of rape, incest, and fetal abnormalities.1,4 A draft bill, prepared by the Law Commission in consultation with the Ministry of Child Development and Women’s Affairs and the Ministries of Health and Justice, awaits approval at this writing.4,5 This bill, if passed in parliament, will permit abortion under those circumstances if recommended by a panel of medical experts based at a government hospital (Anonymous, e-mail communication, August 28, 2012). Although the proposed amendment will make abortion law less restrictive and provide some leeway to women in Sri Lanka, much broader legal and policy changes will be required to address unsafe abortion.

A SUCCESS STORY IN MATERNAL HEALTH

Sri Lanka has been commended internationally for achievements in maternal health.6 Maternal mortality has seen a steady decline since the 1950s, a decline that has been attributed to progressive social policy, including universal health care and education, and well-developed health infrastructure.6 Between 2000 and 2010, the maternal mortality ratio decreased from 58 to 35 deaths per 100 000 live births.7 According to the latest Demographic and Health Survey (2006/2007) that did not include the war-afflicted Northern Province, about 98% of births were attended by skilled personnel and took place in hospitals that year.8 Although these achievements are indeed praiseworthy, it is within this backdrop of a functioning and accessible system of health care that the Ministry of Health does little to address unsafe abortion.

There are no national-level statistics on induced abortion.9 The only countrywide survey on abortion, a United Nations Population Fund–sponsored project undertaken in the late 1990s, found a high prevalence of induced abortion. On average, the abortion rate was 45 abortions per 1000 women of reproductive age (95% confidence interval [CI] = 38, 52); abortion rates were highest among married women from rural provinces. It was estimated that close to 650 abortions took place daily that year.10

Although data on abortion-related mortality are collected through an effective maternal death surveillance system,6 the extent of morbidity caused by unsafe abortion is largely unknown. The Ministry of Health estimates that about 7% to 16% of all hospital admissions for women are attributed to complications of abortion,11 but health information systems in place in Sri Lanka are unable to quantify the incidence of unsafe abortion because clandestine services operate outside formalized health care. Neither can the hospital burden of abortion be estimated accurately because women accessing postabortion care do not always disclose their medical history.12

Studies of women seeking abortion in Sri Lanka have consistently found that most women have an abortion either because they have already completed their families or because they get pregnant too soon after the birth of their youngest child.13–16 One of these revealed that of a sample of 356 women, a quarter already had one or more abortions previously, and 10% had three or more.14 Taken together, these studies suggest that abortion is used as a method of family planning. It has also been recognized that abortion has made significant contributions to fertility decline in the country.13

CLANDESTINE ABORTION SERVICES

There is no legal or policy framework endorsed by the government to provide abortion services to women within the restrictions of the law. In practice, the recommendation of two consultant obstetrician–gynecologists is required for a legal abortion to be performed at a government hospital.9

Although maternity services are accessible free of charge through the public sector, the legal status of abortion does not allow women to access this service in government hospitals.12 As in other restrictive contexts, abortion services are quite easily accessible in Sri Lanka where clandestine services are available through the private sector.13,14 These services, including their quality and cost, are unregulated because of their clandestine nature.12,13

Relatively “safe” menstrual regulation services could be obtained until quite recently through Marie Stopes International, a nongovernmental organization providing sexual and reproductive health services globally.14,17 Although successive governments had turned a blind eye to these services, the current regime shut them down, together with other obtrusive services in 2007.17,18

Although “safe” abortion services are still quite accessible, especially in Colombo and other larger towns where specialist services may be obtained, 19 the consequences of the crackdown are likely to be felt more by poorer women who may be compelled to access less expensive alternatives. Because low socioeconomic status, low levels of education, and rural background have been found to be associated with a higher risk for resorting to abortion in Sri Lanka,10,13 it is not surprising that the highest rates of abortion have been recorded in poorer rural provinces.10

Meanwhile, media reports suggest that women do have access to abortion medications. Mifepristone and misoprostol, not yet approved for use by authorities in the country, are evidently available and prescribed by medical practitioners and pharmacists.20,21 An attempt to register misoprostol failed in 2010, when the responsible body was unable to reach a decision on registration. The decision remains pending at this writing (Anonymous, e-mail communication, October 5, 2012). It has been argued that the decision to stall the registration of misoprostol was influenced by its potential use for abortion.22

DIRE PUBLIC HEALTH CONSEQUENCES

With a high political commitment to improving maternal health, Sri Lanka is on track to achieving the reduction in maternal mortality stipulated by the 5th Millennium Development Goal.23 But the Ministry’s failure to address unsafe abortion as a cause of maternal mortality becomes clear in the analysis of recent mortality data from the Family Health Bureau of Sri Lanka.

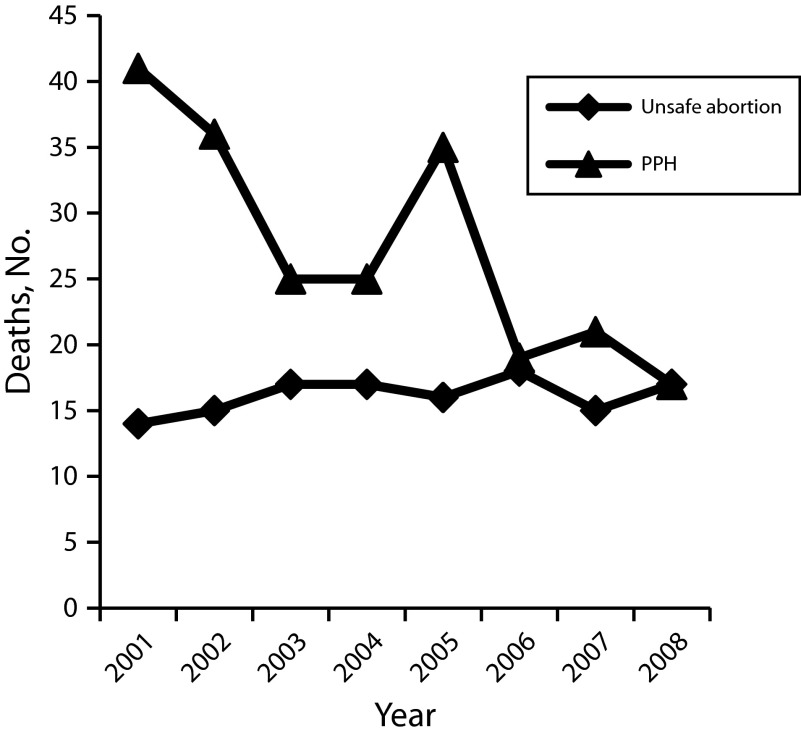

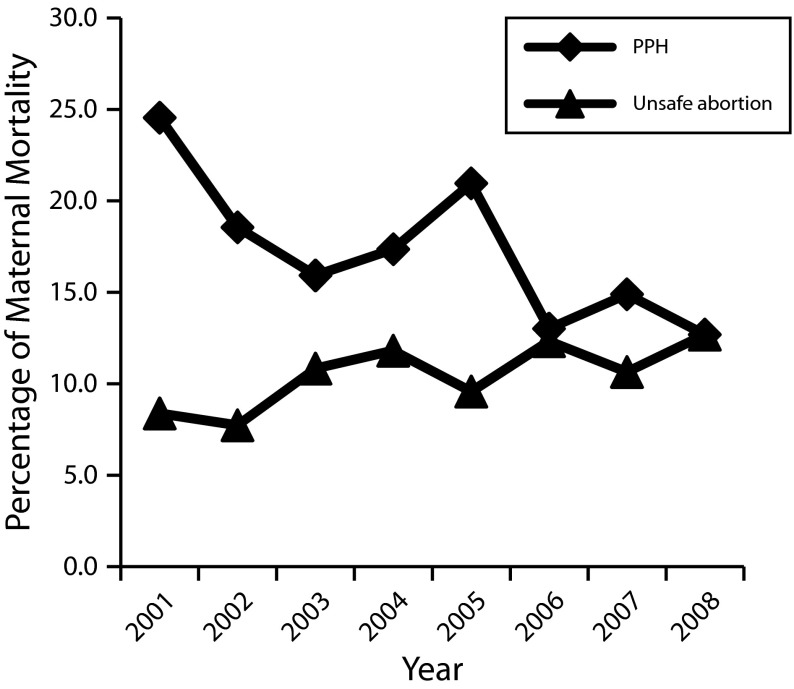

Between 2001 and 2008, the leading causes of maternal mortality have been postpartum hemorrhage, cardiovascular disease, hypertension in pregnancy, and unsafe abortion.24,25 The Ministry’s efforts are evident from the rapid decline in maternal mortality achieved over this period. The total number of maternal deaths fell from 167 in 2001 to 134 in 2008. This decline is mostly attributable to a decline in deaths from postpartum bleeding, which fell from 41 (24%) to 17 (13%) in the period under analysis (Figure 1). Although the number of abortion-related fatalities remained relatively constant at about 15 to 20 deaths annually, the proportion of deaths from unsafe abortion rose from 8% in 2001 to 13% in 2008 (Figure 2).24,25 Although these data do not suggest that mortality from unsafe abortion increased during this period, they do signal that unsafe abortion remains unaddressed in Sri Lanka. Indeed, by 2008, mortality from unsafe abortion equaled that from postpartum hemorrhage,26 the number-one killer in most poor countries.27 Clearly, unsafe abortion will need to be addressed for Sri Lanka to move forward.

FIGURE 1—

Total number of deaths from unsafe abortion and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH): Sri Lanka, 2001–2008.

Source. Data from Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health Sri Lanka.24,25

FIGURE 2—

Deaths from unsafe abortion and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) as a percentage of maternal mortality: Sri Lanka, 2001–2008.

Source. Data from Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health Sri Lanka.24,25

Criminalizing abortion results in substandard services without mechanisms of accountability to protect women. The risk of prosecution also deters women from seeking health care.28 A study of 56 women admitted for postabortion care to five government hospitals in Sri Lanka found that these women delayed seeking care because they feared being reported to the police. They were also reluctant to access services at a government hospital because they felt they would encounter stigma and discrimination from health care providers. Although most women in this study claimed to be satisfied with the medical care they received, all participants complained that they had few opportunities to ask questions about their condition with more than 10% experiencing verbal abuse from hospital staff.12

EXPLOITING WOMEN

Debates on abortion often overlook the context in which women seek and access abortion services. There is little discussion of the lucrative services on offer from physicians and others because abortion is criminalized. Neither is there concern about the ways in which women are humiliated and made vulnerable in the hands of providers. A survey of 665 women who had had an abortion found that about 70% identified their providers to be medical practitioners. In this study, the abortion procedure was explained only to a little more than a quarter of the sample and most providers cautioned their clients to keep the abortion a secret. A qualitative arm of this study was able to capture the inhumane treatment women received in the hands of their providers. For instance, three participants alluded to sexual advances being made by providers, and a participant from the war-ravaged Eastern province was able to obtain the service on the condition that she had sexual intercourse with the provider.13

Where abortion is criminalized, women are more likely to be exploited, both financially and otherwise. They are first traumatized by the experience of accessing an abortion in a criminalized context. Then they are likely to encounter abortion-related stigma in postabortion care. And let us not forgot those women who lose their lives because they get to a hospital too late.

GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

Perhaps the government has been able to maintain its deafening silence on the need for legal reform because of its much eulogized commitment to maternal health. The strategy of the Ministry of Health has been, so far, to work toward preventing deaths from unsafe abortion by providing postabortion care.24,26 Because health care is accessible to most women in Sri Lanka, abortion-related deaths have been few.

Apart from acknowledging that unsafe abortion is a problem, the Ministry of Health provides little substantive guidance on addressing unsafe abortion. For instance, the National Strategic Plan on Maternal and Newborn Health (2012–2016) lists the reduction of abortion-specific mortality from 4.5 to 3 deaths per 100 000 live births as an objective of the National Maternal and Newborn Health Program. Beyond its mantra on improving access to contraceptive services and postabortion care, the Ministry does not offer any novel ideas for achieving this objective.26

The Ministry emphasizes the need to improve access to contraceptive services in its policy documents.24,26 Although the contraceptive prevalence rate is relatively high at about 68% (with 52% using a modern method),8 contraceptive services at grassroots level continue to target married women.6 Research highlights the low levels of contraceptive awareness in Sri Lanka.29 For instance, a Colombo-based study found low levels of awareness of the risk of pregnancy during the postpartum period among women and men. Men were less knowledgeable than women, perhaps because they were not targeted for health education during the antenatal period.30 A recent United Nations Children’s Fund–sponsored study on adolescent issues found shockingly low levels of awareness on reproductive health including contraception.31

The high rate of unintended pregnancy has been attributed to the limited contraceptive information imparted through formal health education programs in schools and in the community.29 But these analyses overlook that contraceptives can never eliminate the need for abortion services owing to their relatively high failure rates with typical use as well as the fact that they are unlikely to be used when sexual intercourse is forced.32

RESISTANCE TO LEGAL REFORM

Although nongovernmental organizations such as the Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka have been supportive of legal reform,33 public statements of support from civil society have been few. With less than 10% of Sri Lanka’s population being Catholic, the current push for reform faces formidable opposition from the Catholic Church. The Catholic Bishops Conference released a statement expressing its collective opposition to any kind of reform earlier this year.34 The Archbishop of Colombo, Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith, even linked the move to Western conspiracies.34 Groups of Catholic professionals, including physicians, have expressed antiabortion sentiments in the media.35,36 Most recently, the Catholic Bishops Conference declared November 11, 2012, “The Sunday of the Unborn Child.”37 An official at the Ministry of Child Development and Women’s Affairs claimed that these attempts to obstruct legal reform have caused some delays in the process.5 Although a number of Buddhist monks have expressed their individual opinions against reform in media interviews,4,38 official statements opposing the amendment are yet to come from other religious quarters.

Abortion is a contentious issue locally and internationally with opposition coming from diverse groups and stakeholders. It could be argued that law reform is unnecessary because Sri Lanka has done well in maternal health with the restrictive abortion laws that are in place. Or one could argue that providing safe abortion services need not be prioritized at present because abortion-related mortality is low. Others may worry that expanding abortion law could result in increasing rates of “promiscuity” and indiscriminate use of abortion services. Perhaps for these reasons, politicians and policymakers in Sri Lanka have been determined to restrict the push for reform to legalize abortion under circumstances in which women are perceived to be “blameless.” Admittedly, such an approach is more likely to garner support, but it fails to recognize that most women resort to abortion for other reasons.

EXAMPLES FROM THE REGION

The only other country in the South Asian region that has as restrictive an abortion law is Afghanistan. Despite restrictive legislation in Bangladesh, a policy that allows for menstrual regulation up to the 10th week of pregnancy provides significant leeway to women there. Both in Pakistan and the Maldives abortion is permitted to preserve physical health—laws less restrictive than in Sri Lanka. In Bhutan, abortion is permitted to save a woman’s life as well as in instances of rape and incest. In addition, this law considers grounds relating to factors such as a woman’s age and capacity to care for a child. In India, the law permits abortion for socioeconomic reasons, to preserve health, when there are fetal abnormalities, and also after rape. The most progressive abortion law comes from Nepal where abortion is permitted in the first trimester without restriction except for a prohibition on sex-selective abortion.39,40

Admittedly these are legal frameworks that say nothing about their implementation or their effectiveness. For instance, one might take the examples of India and Nepal to argue against reform because abortion-related mortality remains quite high in these contexts despite legal reform. However, a host of factors including lacking resources to deliver primary health care have deterred these laws being put into practice in India.28 In a similar way, providing accessible and affordable abortion services in remote areas of Nepal has remained challenging because of deficient infrastructure and health resources.41,42 Given Sri Lanka’s achievements in providing safe maternity services across the country, it would seem unwise to predict the effectiveness of reform in Sri Lanka by the experiences of India and Nepal.

A CALL TO ACTION

The current push for reform in Sri Lanka is indeed important. If this bill is passed, specific groups of women, albeit small, will have access to legal abortion. But significant reductions in maternal morbidity and mortality will not be achieved because the majority of women accessing abortion services in Sri Lanka do so for other reasons. Moreover, it has been established from the experiences of other countries that broader legal reform is essential to address unsafe abortion in a comprehensive way.43 It is possible that advocacy for broader reform is held in restraint by conservative anti-abortion forces operating in the country, but how do we account for the progress achieved in other countries where the very same forces exist? Is it perhaps our silence that strengthens the campaign against abortion in Sri Lanka? As the authorities consider abortion law reform for instances of rape, incest, and fetal abnormalities, the time is critical for those of us who recognize the need for broader reform to come together in Sri Lanka.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

- 1.Kodagoda A. Abortion rules should be relaxed to suit medical needs – Minister Tissa Karaliyadda. Sunday Observer. January 8, 2012. Available at: http://www.sundayobserver.lk/2012/01/08/pol05.asp. Accessed September 11, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Penal Code, Section 303. Available at: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/research/srilanka/statutes/Penal_Code.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2012.

- 3.Walatara S. Abortion: the right to choose. Moot Point. 1998;2(1):24–38 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharmasena A. Abortion debate open. Lakbima News. February 26, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Opposition by church delays change in abortion laws in Sri Lanka. Xinhua. June 26, 2012. Available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/world/2012-06/26/c_131677214.htm. Accessed September 11, 2012.

- 6. Report of the External Review of Maternal and Newborn Health Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: World Health Organization; 2007.

- 7. World Health Organization. MDG 5: Maternal health, maternal mortality ratio. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Available at: http://apps.who.int/ghodata. Accessed September 11, 2012.

- 8. Department of Census and Statistics. Sri Lanka Demographic and Health Survey 2006/07 Preliminary Report (Draft). Colombo, Sri Lanka: Department of Census and Statistics; 2008. Available at: http://www.statistics.gov.lk/social/DHS%20Sri%20Lanka%20Preliminary%20Report.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2012.

- 9. Women of the World: Laws and Policies Affecting Their Reproductive Lives: South Asia. New York, NY: Center for Reproductive Rights; 2004. Available at: http://reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/pdf_wowsa_srilanka.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2012.

- 10.Rajapaksa LC. Estimates of induced abortions in urban and rural Sri Lanka. J Coll Community Physicians Sri Lanka. 2002;7:10–16 [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Induced abortion. Sri Lanka reproductive health profile. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section13/Section36/Section1579_6462.htm. Accessed September 11, 2012.

- 12.Thalagala N. Economic Perspectives on Unsafe Abortions in Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thalagala N. Process, Determinants and Impact of Unsafe Abortions in Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ban DJ, Kim J, de Silva WI. Induced abortion in Sri Lanka: who goes to providers for pregnancy termination? J Biosoc Sci. 2002;34(3):303–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perera J, de Silva T, Gange H. Knowledge, behaviour and attitudes on induced abortion and family planning among Sri Lankan women seeking termination of pregnancy. Ceylon Med J. 2004;49(1):14–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Silva WI, Dayananda RA, Perera N. Contraceptive behaviour of abortion seekers in Sri Lanka. Asian Popul Stud. 2006;2(1):3–18 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Closing down Marie Stopes in Colpetty. Dinamina. August 1, 2007.

- 18.Bastians D. The uterus wars: inside an abortionist’s lair. The Nation. 2007;(December):2. Available at: http://www.nation.lk/2007/12/02/eyefea6.htm. Accessed September 12, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Playing god. Daily Mirror video. Available at: http://video.dailymirror.lk/videos/589/playing-god. July 26, 2010. Accessed September 12, 2012.

- 20.Perera S. Mifepristone and misoprostol sold on the sly: use of banned abortion drugs in Sri Lanka cause concern in medical circles. The Island. October 9, 2010. Available at: http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=8638. Accessed September 12, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohamed R. The world’s first abortion pill gains a new lease of life in Sri Lanka. Sunday Leader. October 31, 2010. Available at: http://www.thesundayleader.lk/2010/10/31/world%E2%80%99s-first-abortion-pill-gains-a-new-lease-of-life-in-sri-lanka. Accessed September 27, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar R. Misoprostol and the politics of abortion in Sri Lanka. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20(40):166–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senanayake H, Goonewardene M, Ranatunga A, Hattotuwa R, Amarasekera S, Amarasinghe I. Achieving Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 in Sri Lanka. BJOG. 2011;118(suppl 2):78–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition. Overview of Maternal Mortality in Sri Lanka 2001–2005. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Family Health Bureau; 2009.

- 25. Family Health Bureau. Annual Report on Family Health Sri Lanka 2008–2009. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition; 2010.

- 26. Family Health Bureau. National Strategic Plan on Maternal and Newborn Health (2012–2016). Colombo, Sri Lanka: Ministry of Health Sri Lanka; 2011.

- 27. WHO Guidelines for the Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage and Retained Placenta. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009:1. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598514_eng.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2012.

- 28.Berer M. Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(5):580–592 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senanayake L, Willatgamuwa S. Reducing the Burden of Unsafe Abortion in Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka; 2009:21–31 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senanayake H, Seneviratne SA, Kariyawasam V. Knowledge, attitudes, practices regarding postpartum contraception among 100 mother–father pairs leaving a Sri Lankan maternity hospital after childbirth. Ceylon Med J. 2006;51(1):41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thalagala N. National Survey on Emerging Issues Among Adolescents in Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2004; Available at: http://www.unicef.org/srilanka/Full_Report.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2nd ed Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012:22–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathaniel C. Government to legalize abortion. Ceylon Today. January 29, 2012:5 Available at: http://www.ceylontoday.lk/e-paper.html. Accessed September 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mudalige D. Catholic bishops on abortion law. Daily News. March 30, 2012. Available at: http://www.dailynews.lk/2012/03/30/news34.asp. Accessed September 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jayasuriya L, Abeywardena M, Fernandopulle M. Don’t relax laws preventing abortion in Sri Lanka. The Island. May 17, 2012. Available at: http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=52111. Accessed September 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mudugamuwa M. What others say about legalizing abortion. The Island. April 2, 2012. Available at: http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=48937. Accessed November 9, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Where the womb becomes the tomb. Daily Mirror. November 9, 2012. Available at: http://www.dailymirror.lk/opinion/172-opinion/23345-where-the-womb-becomes-the-tomb-.html. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- 38.Jayawardana S. Abortion: women’s rights vs. child’s rights. The Nation. 2012;(February):26. Available at http://www.nation.lk/edition/component/k2/item/3127-abortion-women%E2%80%99s-rights-vs-child%E2%80%99s-rights.html. Accessed September 13, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Center for Reproductive Rights. The world’s abortion laws map 2007. Publications: maps and posters. July 2007. Available at: http://reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/Abortion%20Map_FA.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2012.

- 40. Asia Safe Abortion Partnership. Country profiles. Available at: http://www.asap-asia.org/country-profiles.html. Accessed September 14, 2012.

- 41. Guttmacher Institute. Making Abortion Services Accessible in the Wake of Legal Reforms: A Framework and Six Case Studies. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2012. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/abortion-services-laws.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 42.Samandari G, Wolf M, Basnett I, Hyman A, Andersen K. Implementation of legal abortion in Nepal: a model for rapid scale-up of high-quality care. Reprod Health. 2012;9:7 Available at: http://www.reproductive-health-journal.com/content/9/1/7. Accessed November 9, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berer M. National laws and unsafe abortion: the parameters of change. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12(24, suppl):1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]