Abstract

Background

Conditional survival estimates account for time survived since diagnosis to provide prognostic information for long-term cancer survivors. For rectal cancer, stage-related treatment (e.g. neoadjuvant radiotherapy) affects pathologic stage and therefore stage-associated survival estimates.

Objectives

To estimate conditional survival for rectal cancer patients and to develop an interactive calculator to use for individualized patient counseling.

Patients

Patients with rectal adenocarcinoma were identified using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results registry (1988-2002, N=22,610).

Design

Cox regression models were developed to determine adjusted survival estimates (years 1-10) and used to calculate 5-year adjusted conditional survival. Models were built separately for no radiotherapy, preoperative radiotherapy, postoperative radiotherapy and stage IV patients. Covariates included age, gender, race, tumor grade, and type of surgery. An internet-based conditional survival calculator was developed.

Results

Radiotherapy was given to 42.6% of patients (14.1% pre-operative, 28.4% post-operative). Significant improvements in 5-year conditional survival were observed for all stages, except stage I due to initial high survival probability at diagnosis. Patients with advanced stage had the greatest improvements in conditional survival, with 5-year absolute increases of 33% (stage IIIC) and 54% (IV). Other factors associated with conditional survival included sequence of radiotherapy and surgery, age, race, and tumor grade. The internet-based conditional survival calculator can be accessed at www.mdanderson.org/rectalcalculator.

Limitations

Data source used does not include information on chemotherapy treatment, change in staging after neoadjuvant treatment, or patient comorbidities.

Conclusion

Conditional survival estimates improve over 5 years in rectal cancer patients, with the greatest improvements observed among advanced stage patients. The conditional survival calculator is an individualized decision support tool that informs patients, who must make non-treatment-related life decisions, and their clinicians planning follow-up and surveillance.

Keywords: conditional survival, rectal adenocarcinoma, rectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal adenocarcinoma is the third most common cancer, with 143,460 new cases projected in 2012.1 Rectal cancer cases represent approximately one third of these cases. Survival after rectal cancer diagnosis and treatment is dependent upon the stage of disease at presentation. Overall, 5-year survival estimates range from 90% for stage I cancers to 7% for stage IV cancers. However, these traditional survival estimates made at the time of diagnosis of rectal cancer may be less meaningful for long-term survivors. It is becoming increasingly appreciated that for patients who survive for some duration after their diagnosis, survival probabilities change over time. Conditional survival (CS) takes into account the time survived since diagnosis and treatment in predicting future survival. CS may give more accurate survival estimates for cancer patients, particularly for those with advanced disease, and can give clinically relevant information upon which to base future treatment and surveillance. For example, a patient who has survived three years from initial diagnosis for rectal cancer may now have a different 5-year survival than initially predicted at diagnosis. The adjusted 5-year survival can be re-calculated based on her time already survived and additional patient and tumor factors. This adjusted survival estimate can help patients make important life decisions and decrease uncertainty about their future.

The availability of large, population-based tumor registry data has facilitated such analyses, which have thus been reported for several cancer sites.2-10 The technique for estimating CS has recently been refined to incorporate covariate adjustment2 and in order to facilitate access to this information by clinicians, internet-based tools for determining covariate-adjusted CS estimates are now available for selected cancer sites including gallbladder11, melanoma12, and colon2. In a prior study among rectal cancer patients, CS estimates were shown to improve over time.[9] However, the estimation of conditional survival among patients with rectal cancer is complicated by the need for perioperative multidisciplinary treatment, a factor not previously considered.

Although surgical resection is the primary treatment for localized rectal cancer, radiation therapy (XRT), either given preoperatively or postoperatively, and generally with concurrent fluorouracil-based chemotherapy, improves locoregional control.13-16 Preoperative treatment of rectal cancer can influence final pathologic stage. For example, both tumor size and nodal status can be affected by preoperative radiation therapy. Therefore, survival estimates based on pathologic stage information must take in to account the sequence of radiation therapy and surgical treatment. 17, 18

The objective of this study was to determine CS estimates for rectal cancer patients using a population-based cancer registry data set.

Methods

Data Source and Case Identification

Data were retrieved from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER 17) Program, release 2010.19 SEER collects cancer incidence and survival data from 18 regional population-based registries now covering approximately 26% of the U.S. population. During most of the study inclusion period (through 2000), SEER captured incident data from approximately 14% of the US population. The SEER registries routinely collect data on patient demographics, primary tumor site, tumor morphology, pathologic stage at diagnosis, first course of treatment (radiotherapy and surgery), and patient follow-up for vital status. SEER does not collect data on chemotherapy, which was therefore not evaluated in this study.

Patients eligible for this study included those with adenocarcinoma of the rectum (ICD-O-3 codes 8050, 8140-8147, 8160-8162, 8180-8221, 8250-8507, 8520-8551, 8560, 8570-8574, 8576, 8940-8941) who were diagnosed from January 1988 through December 2002. The inclusive study dates were chosen because 1988 was the first year SEER coded data elements that would allow restaging using the American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition staging manual (AJCC 6th)20 and 2002 was the last year of diagnosis with at least 5 years of follow-up. Based on available TNM data elements from pathologic staging, AJCC 6th edition stage assignment was determined for each case.

Exclusion criteria included age younger than 18 or older than 90 years, in situ disease, lack of histologic confirmation or survival time information, and if incomplete data precluded AJCC 6th edition stage assignment. Cases were also excluded if the cancer reporting source was a nursing home, hospice, autopsy, or death certificate as these patients would not have been likely to receive cancer-directed therapy, or if death occurred within 30 days of diagnosis. Additionally, cases were excluded if the incident diagnosis of rectal cancer was not their first and only occurrence of malignant disease.

Statistical Analysis

Cancer-specific survival (CSS) was determined using SEER data through December, 2007; cases were censored if death was from a cause other than colorectal cancer or if the patient was alive at follow-up. CSS was estimated employing the Kaplan-Meier method. The multiplicative law of probability was used to calculate the conditional survival among patients with a minimum of 5-years follow-up as previously described.7 Specifically, CS represents the probability that a cancer patient will survive an additional x years, given that the patient has already survived a given number of years (y). For example, to compute the x-year CS for patients who have survived y years, the (x+y)-year CSS is divided by the y-year CSS thus yielding cancer-specific conditional survival.

To account for the simultaneous effect of multiple variables on survival, including factors associated with secular trends in preoperative vs. postoperative radiation therapy, separate multivariate Cox regression models were built for patients who underwent no XRT, pre-operative XRT, post-operative XRT, or had stage IV disease. Separate models were used to account for potential imbalance in the different treatment groups based on selection bias for adjuvant therapy or pathologic tumor downstaging associated with preoperative radiotherapy. However, the covariates adjusted in the model were the same for the 3 models for patients with localized stage (stage I-III), including age (<50, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, 80+), sex (male, female), race (white, black, other), tumor grade (low [well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated], high [poorly-differentiated or undifferentiated] or unknown), surgery type (local excision and radical surgery) and AJCC 6th edition stage. A fourth model was used for patients with distant metastasis for which the use of any radiotherapy or primary tumor directed surgery were included as binary covariates in the model. Adjusted survival estimates were calculated at year 1 through 10 by category of age, sex, race, tumor grade, stage and these estimates formed the basis to generate 5-year adjusted CS for patients survived 1 through 5 years. The proportional hazards assumption was verified graphically on the basis of Schoenfeld residuals21.

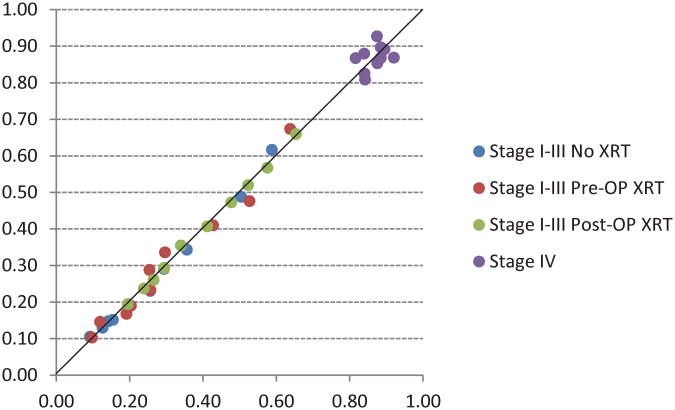

The 4 final models were used to develop an internet browser-based CS calculator to predict individualized CSS and CS. Model performance was internally validated by calibration which was graphically evaluated by the goodness-of-fit test for Cox regression using the stcoxgof module for STATA22. The plot presents the observed and model-predicted expected risk of cancer-specific death in each decile of risk.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata MP Version 10.0 (release 2007, College Station, TX). Because the study used preexisting data with no personal identifiers, this study was exempt from review by our institutional review board.

Results

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the 22,610 patients are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were white men between the ages of 60 and 79 who had low grade tumors (well or moderately differentiated). Stage I and II patients represented 48% of the cohort, 30.4% had stage III disease, and 21.7% had stage IV disease. Radical surgery, consisting of resection of the rectum by either low anterior resection or abdominoperineal resection, was performed in 87.9%. The majority of patients (57.4%) received no radiation (XRT). XRT was given preoperatively to 14.1% of patients and postoperatively to 28.4%.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients treated for rectal adenocarcinoma from 1988 to 2001 stratified by radiation treatment and stage IV disease (N = 22,610).

| No radiation | Preoperative radiation | Postoperative radiation | Stage IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| (N = 8,939) | (N = 2,818) | (N = 5,954) | (N = 4,899) | |||||

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <50 | 752 | 8.4 | 572 | 20.3 | 965 | 16.2 | 704 | 14.4 |

| 50–59 | 1,363 | 15.2 | 754 | 26.8 | 1,422 | 23.9 | 960 | 19.6 |

| 60–69 | 2,235 | 25 | 774 | 27.5 | 1,814 | 30.5 | 1,319 | 26.9 |

| 70–79 | 2,811 | 31.4 | 593 | 21 | 1,412 | 23.7 | 1,253 | 25.6 |

| 80+ | 1,778 | 19.9 | 125 | 4.4 | 341 | 5.7 | 663 | 13.5 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 4,979 | 55.7 | 1,857 | 65.9 | 3,626 | 60.9 | 3,006 | 61.4 |

| Female | 3,960 | 44.3 | 961 | 34.1 | 2,328 | 39.1 | 1,893 | 38.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 7,584 | 84.8 | 2,378 | 84.4 | 4,952 | 83.2 | 4,013 | 81.9 |

| Black | 506 | 5.7 | 174 | 6.2 | 363 | 6.1 | 451 | 9.2 |

| Other | 849 | 9.5 | 266 | 9.4 | 639 | 10.7 | 435 | 8.9 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||||

| Low | 7,318 | 81.9 | 2,068 | 73.4 | 4,462 | 74.9 | 2,999 | 61.2 |

| High | 1,183 | 13.2 | 518 | 18.4 | 1,284 | 21.6 | 1,137 | 23.2 |

| Unknown | 438 | 4.9 | 232 | 8.2 | 208 | 3.5 | 763 | 15.6 |

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Local excision | 105 | 1.2 | 9 | 0.3 | 57 | 1 | 154 | 3.1 |

| Radical surgery | 8,834 | 98.8 | 2,809 | 99.7 | 5,897 | 99 | 2,344 | 47.8 |

| No surgery | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2,401 | 49 |

| AJCC stage | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| I | 4,505 | 50.4 | 683 | 24.2 | 308 | 5.2 | - | - |

|

|

||||||||

| IIA | 2,090 | 23.4 | 972 | 34.5 | 1,703 | 28.6 | - | - |

|

|

||||||||

| IIB | 208 | 2.3 | 157 | 5.6 | 221 | 3.7 | - | - |

|

|

||||||||

| IIIA | 367 | 4.1 | 125 | 4.4 | 618 | 10.4 | - | - |

|

|

||||||||

| IIIB | 999 | 11.2 | 545 | 19.3 | 1,597 | 26.8 | - | - |

|

|

||||||||

| IIIC | 770 | 8.6 | 336 | 11.9 | 1,507 | 25.3 | - | - |

|

|

||||||||

| IV | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4,899 | 100 |

AJCC, American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging Manual (6th ed.).

all χ2 test p-values were less than 0.001.

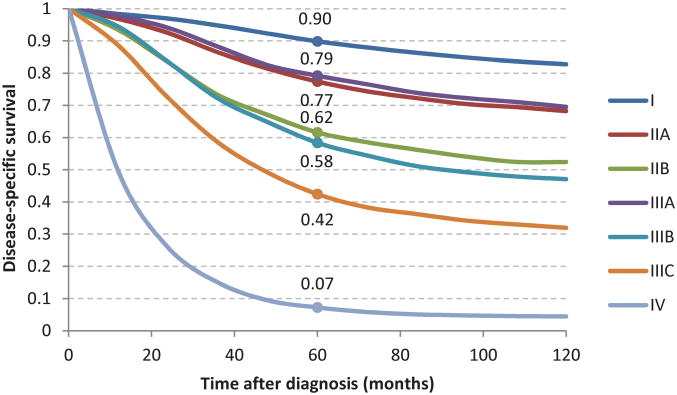

Traditional and crude conditional survival estimates

The traditional 10-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) by AJCC stage is shown in Figure 1. The entire cohort was followed for at least 5 years after diagnosis or until death. The median follow up time was 89 months. The final model used for the adjusted analyses is shown in Table 2. The calibration plot indicated good agreement between the model-predicted and observed risk of cancer-specific death in each decile of risk, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig 1.

Ten-year traditional cancer-specific survival by AJCC stage for rectal adenocarcinoma patients diagnosed between 1988 and 2002.

Table 2. Summary of adjusted conditional survival rates for rectal adenocarcinoma patients at year 0 and year 5 (N = 22,610).

| No XRT (N = 8,939) | Preoperative XRT (N = 2,818) | Postoperative XRT (N = 5,954) | Stage IV (N = 4,899) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Year 0 (%) | Year 5 (%) | Δ | Year 0 (%) | Year 5 (%) | Δ | Year 0 (%) | Year 5 (%) | Δ | Year 0 (%) | Year 5 (%) | Δ | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| <50 | 87.5 | 93.3 | 5.8 | 82.0 | 92.3 | 10.2 | 76.3 | 87.8 | 11.5 | 7.5 | 55.9 | 48.4 |

| 50–59 | 85.0 | 91.9 | 6.8 | 78.7 | 90.7 | 12.0 | 72.4 | 85.6 | 13.2 | 7.3 | 55.6 | 48.3 |

| 60–69 | 82.4 | 90.4 | 8.0 | 76.8 | 89.8 | 13.0 | 68.1 | 83.1 | 15.1 | 4.5 | 49.8 | 45.3 |

| 70–79 | 77.3 | 87.4 | 10.1 | 67.7 | 85.3 | 17.6 | 62.4 | 79.8 | 17.3 | 2.4 | 43.5 | 41.0 |

| 80+ | 68.6 | 82.1 | 13.5 | 64.1 | 83.5 | 19.3 | 52.2 | 73.2 | 21.0 | 1.8 | 40.6 | 38.8 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 78.4 | 88.1 | 9.7 | 76.4 | 89.6 | 13.2 | 67.8 | 83.0 | 15.2 | 4.2 | 49.2 | 45.0 |

| Female | 81.0 | 89.6 | 8.6 | 76.3 | 89.6 | 13.3 | 69.9 | 84.2 | 14.3 | 4.1 | 48.8 | 44.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | 79.8 | 88.9 | 9.1 | 77.4 | 90.1 | 12.7 | 68.8 | 83.6 | 14.8 | 4.3 | 49.3 | 45.0 |

| Black | 73.9 | 85.4 | 11.5 | 64.4 | 83.6 | 19.2 | 61.5 | 79.1 | 17.7 | 2.4 | 43.3 | 40.9 |

| Other | 81.0 | 89.6 | 8.6 | 73.4 | 88.1 | 14.8 | 71.0 | 84.8 | 13.8 | 5.8 | 52.7 | 46.9 |

| Tumor Grade | ||||||||||||

| Low | 80.3 | 89.1 | 8.9 | 78.2 | 90.5 | 12.3 | 70.8 | 84.7 | 13.9 | 5.8 | 52.7 | 46.9 |

| High | 74.9 | 86.0 | 11.1 | 66.0 | 84.4 | 18.4 | 60.9 | 78.8 | 17.9 | 1.4 | 38.2 | 36.8 |

| Unknown | 74.5 | 85.8 | 11.2 | 67.8 | 85.4 | 17.6 | 52.6 | 73.4 | 20.9 | 1.0 | 35.6 | 34.6 |

| AJCC stage | ||||||||||||

| I | 88.5 | 93.8 | 5.3 | 88.8 | 95.3 | 6.5 | 83.7 | 83.7 | 8.1 | - | - | - |

| IIA | 75.6 | 86.4 | 10.8 | 80.3 | 91.5 | 11.1 | 78.8 | 78.8 | 10.4 | - | - | - |

| IIB | 62.4 | 78.2 | 15.8 | 66.9 | 84.9 | 18.0 | 62.7 | 62.7 | 17.2 | - | - | - |

| IIIA | 74.8 | 85.9 | 11.1 | 81.0 | 91.8 | 10.8 | 80.6 | 80.6 | 9.6 | - | - | - |

| IIIB | 53.4 | 72.1 | 18.7 | 60.2 | 81.3 | 21.1 | 63.9 | 63.9 | 16.7 | - | - | - |

| IIIC | 36.2 | 58.8 | 22.6 | 43.5 | 71.2 | 27.8 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 22.4 | - | - | - |

| IV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4.1 | 49.0 | 44.9 |

XRT, radiation therapy; Δ, indicates the absolute survival improvement when patients have survived 5 years; AJCC, American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging Manual (6th ed.).

Fig 2.

Calibration plot of observed and model-predicted risk of cancer-specific death in each decile of risk.

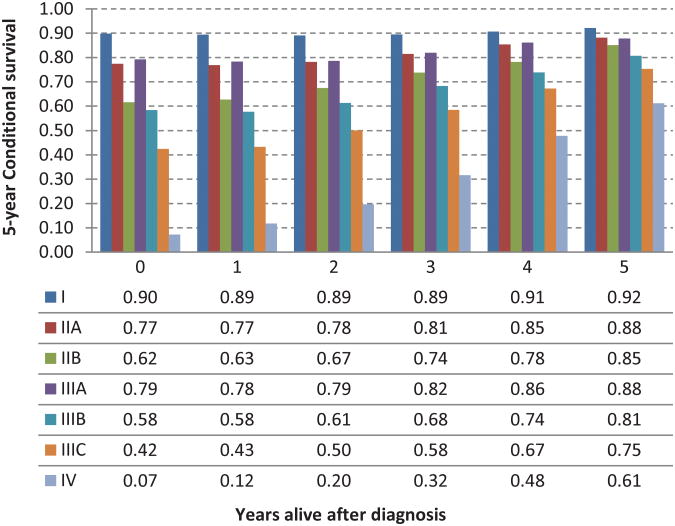

The 5-year crude conditional survival (CS) by stage is shown in Figure 3 and was noted to increase over 5 years among all stages. The change in CS over 5 years was least pronounced in stage I patients who have a high survival probability at diagnosis (90% 5-year CS at diagnosis vs 92% at 5 years from diagnosis). The most significant improvements in CS were observed in patients with advanced stage disease. CS estimates increased from 42% at the time of diagnosis to 75% at 5 years, and from 7% to 61% at 5 years for stage IIIC and IV patients, respectively.

Fig 3.

Five-year crude conditional survival probability by stage for rectal adenocarcinoma patients between 1988 and 2002.

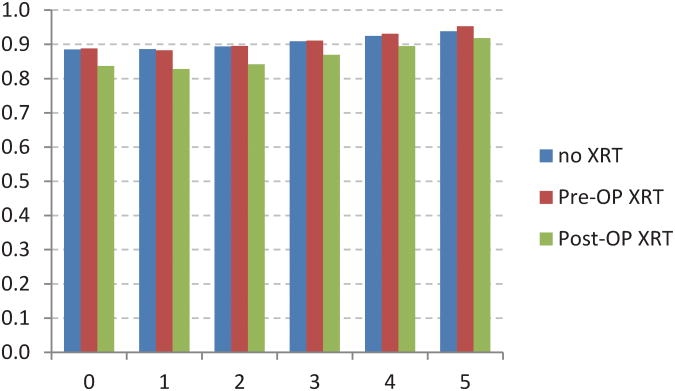

Adjusted conditional survival estimates stratified by sequence of radiation therapy

In order to evaluate the impact of patient, tumor, and treatment factors on CS estimates, survival models adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, tumor grade, and AJCC stage were constructed and stratified into no XRT, preoperative XRT, postoperative XRT or stage IV disease. The adjusted CS estimates at year 0, year 5, and the absolute survival improvement at 5 years for the stratified models are shown in Table 2. Patients who were older, black, and with higher grade tumors experienced the greatest improvements in CS at 5 years compared to their counterparts and the effects were most pronounced in patients receiving radiation therapy, pre- or postoperatively. As was observed in the crude (unadjusted) CS model, the adjusted CS estimates improved over time for all stages and across all three XRT-stratified groups, with the greatest absolute survival improvements observed in patients with stage IIIC disease receiving preoperative XRT and stage IV disease (27.8% and 44.9% improvement in survival at 5 years, respectively).

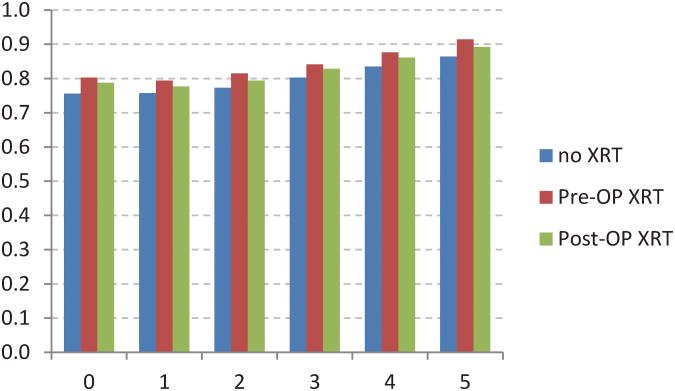

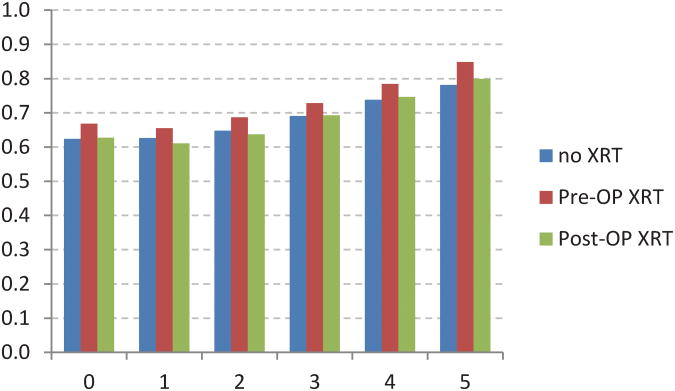

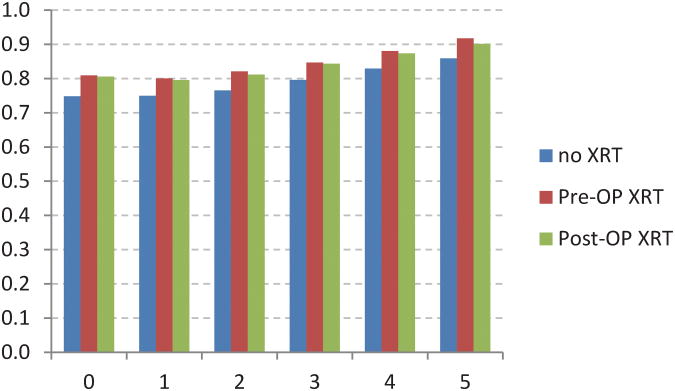

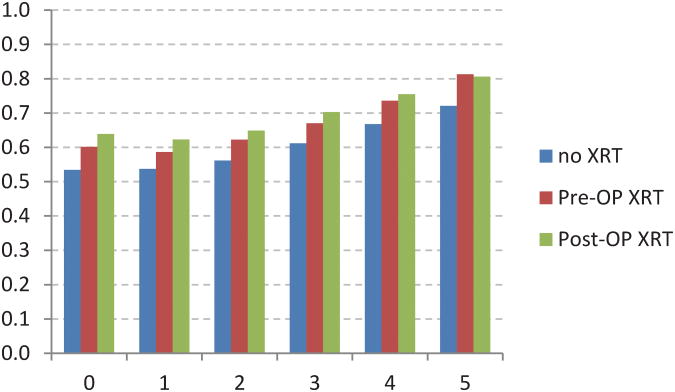

Adjusted conditional survival estimates stratified by stage

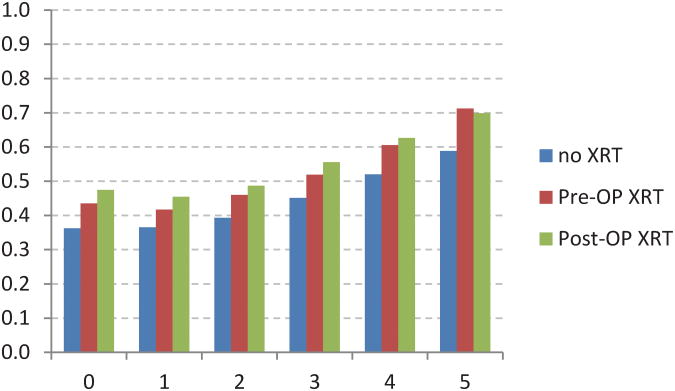

The adjusted CS model revealed additional associations between stage of disease and XRT (Figure 4). For example,stage I patients receiving postoperative XRT had a worse initial survival when compared to no XRT or preoperative XRT (Fig 4A). Stage IIIB and IIIC patients receiving preoperative XRT had worse initial survival when compared to postoperative XRT (Fig 4E, 4F). The no XRT group had lower CS rates over time when compared to pre- and post-operative XRT groups. However, these differences decreased over time.

Fig 4.

Five-year adjusted conditional cancer-specific survival probability stratified by radiation treatment and stage I (A), stage IIA (B), stage IIB (C), stage IIIA (D), stage IIIB (E), stage IIIC (F). X-axis represents patients who have already survived 0 to 5 years. Y-axis represents the 5-year adjusted conditional cancer-specific survival probability.

Cox regression models for adjusted cancer-specific survival

Separate Cox regression models were used to retrieve adjusted cancer-specific survival estimates for four groups of patients: no XRT therapy, preoperative XRT, postoperative XRT, and stage IV disease (Table 3). Age ≥ 60 was a significant adverse prognostic factor in patients receiving no XRT, preoperative XRT and for patients with stage IV disease; age ≥ 50 was a significant adverse prognostic factor for patients in the post-operative XRT group. Black ethnicity, high tumor grade, and AJCC stage were significant adverse prognostic factors among all three groups. Lack of surgical resection was an adverse predictor among stage IV patients (HR=1.66; 95%CI 1.38-1.99) likely reflecting a selection bias for lower disease burden in the cohort of patients with metastatic disease undergoing primary resection. The internet-based CS calculator is available at www.mdanderson.org/rectalcalculator.

Table 3. Cox regression model for rectal adenocarcinoma patients stratified by radiation therapy (N = 22,610). Data indicated as hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals).

| Characteristic | No XRT (N = 8,939) | Preoperative XRT (N = 2,818) | Postoperative XRT (N = 5,954) | Stage IV (N = 4,899) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| <50 (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 50–59 | 1.21(0.99–1.48) | 1.20(0.97–1.49) | 1.19(1.04–1.37) | 1.01(0.91–1.12) |

| 60–69 | 1.45(1.21–1.74) | 1.33(1.08–1.63) | 1.42(1.24–1.62) | 1.20(1.08–1.32) |

| 70–79 | 1.93(1.62–2.30) | 1.96(1.59–2.42) | 1.74(1.52–1.99) | 1.43(1.29–1.58) |

| 80+ | 2.82(2.35–3.39) | 2.24(1.61–3.11) | 2.40(1.98–2.90) | 1.55(1.37–1.74) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.86(0.79–0.93) | 1.00(0.87–1.15) | 0.92(0.84–1.00) | 1.01(0.94–1.07) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White(ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 1.33(1.15–1.55) | 1.72(1.33–2.22) | 1.30(1.10–1.52) | 1.18(1.06–1.31) |

| Other | 0.93(0.81–1.07) | 1.21(0.96–1.52) | 0.91(0.79–1.04) | 0.90(0.81–1.00) |

| Tumor Grade | ||||

| Low (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 1.31(1.18–1.46) | 1.68(1.44–1.97) | 1.43(0.31–1.57) | 1.50(1.39–1.61) |

| Unknown | 1.01(0.82–1.24) | 0.93(0.70–1.23) | 1.29(1.05–1.60) | 1.07(0.98–1.17) |

| Surgery | ||||

| Local excision (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Radical surgery | 1.07(0.64–1.79) | 0.54(0.17–1.70) | 0.78(0.47–1.30) | 0.74(0.62–0.89) |

| No surgery | - | - | - | 1.66(1.38–1.99) |

| AJCC stage | ||||

| I (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| IIA | 2.29(2.04–2.56) | 1.84(1.44–2.35) | 1.34(1.02–1.75) | - |

| IIB | 3.86(3.08–4.83) | 3.38(2.43–4.69) | 2.62(1.90–3.61) | - |

| IIIA | 2.37(1.94–2.91) | 1.77(1.16–2.71) | 1.21(0.90–1.63) | - |

| IIIB | 5.13(4.55–5.79) | 4.26(3.35–5.44) | 2.51(1.93–3.27) | - |

| IIIC | 8.32(7.35–9.40) | 7.00(5.45–8.99) | 4.19(3.22–5.44) | - |

| IV | - | - | - | - |

XRT, radiation therapy;AJCC, American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging Manual (6th ed.).

Discussion

In this population-based study of 22,610 patients with rectal adenocarcinoma, we examined covariate-adjusted conditional survival probabilities stratified by treatment sequence and pathologic stage. We identified improvements in 5-year conditional survival among all stages during the follow-up period after initial diagnosis, with the greatest increases in patients with more advanced stage. We also observed that the use and timing of radiotherapy (XRT) affected CS estimates due to the effects of preoperative therapy on final pathologic stage. In addition, patients who were older, of black race, or who had higher grade tumors all had lower initial survival estimates, but also experienced greater improvements in survival as compared to their counterparts, especially among the preoperative XRT group. Using these data, we developed a unique, interactive web-based calculator to provide individualized decision support for use in counseling patients during the survivorship period.

Traditional survival estimates, which are determined at the time of diagnosis or treatment, may lose meaning over time. Studies of conditional survival provide valuable information to patients and their treating physicians by taking into account the time previously survived in predicting future survival and providing a more clinically relevant estimate of survival for cancer survivors. CS estimates have been determined for several types of cancer, including colon and rectal cancer, however there are additional considerations related to the use of peri-operative radiotherapy for determining conditional survival for rectal cancer. In an analysis of the SEER registry with over 83,000 patients, we demonstrated time-dependent gains in CS for patients with colon cancer; and in the present analysis, similar observations were noted for patients with rectal cancer.[2]

There are a number of issues in cancer survivorship that are related to the expection of future survival and fear of recurrence can be the single largest concern among patients and their caregivers. 23-26 Especially among patients with advanced stage disease, knowledge regarding improvements in conditional survival over time can reduce anxiety and improve quality of life.

A unique feature of our study is the use of covariate-adjusted analysis as well as the development of separate treatment-stratified adjusted regression models to account for the potential unmeasured effects associated with differences in the use and timing of radiotherapy. Perioperative XRT, most commonly given in combination with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in the United States, plays a key role in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer.15, 27, 28 Preoperative XRT results in pathologic tumor regression with a decrease in tumor size, depth of penetration, and nodal stage, which can affect stage at registration and influence stage-dependent outcomes.17, 27, 29-32 Patients with node positive disease receiving no XRT had the worst initial stage-specific survival compared to patients in the no XRT or postoperative XRT groups, with the largest differences observed among stage IIIC patients, for whom the 5-year survival at the time of diagnosis was 43.5%, 36.2%, and 47.5% for preoperative XRT, no XRT, and postoperative XRT, respectively. However, these survival differences decreased over time and in fact reversed in favor of the preoperatively treated patients. At 5 years, patients receiving preoperative XRT had the greatest absolute improvements in CS, analogous to the effects observed for patients with stage IV disease. Interestingly, among patients with stage IIB (T4) disease, the effect of preoperative radiotherapy on improving survival also translated to a persistently improved conditional survival probability as shown in figure 4c. Although the impact of preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer on survival is a subject of trans-Atlantic controversy, our results suggest that a permanent survival benefit may exist in the stage IIB subcohort.14, 33 Thus the declining risk for cancer mortality over time can be individually quantified using our analysis.

It is also important to consider patients who had not undergone pelvic radiotherapy separately, as this group is subject to treatment bias particularly among those patients with stage II or III cancers whose long-term outcomes might have been affected by the use of adjuvant therapy. We also separately modeled CS among patients with stage IV disease because these patients represent a different patient population than those with resected localized disease and for whom the regression models for localized disease cannot be applied.

Thus our use of separate regression models stratified by the use and timing of radiotherapy or presence of stage IV disease accounts for these unmeasured treatment-related effects as demonstrated by the calibration plot. To facilitate the use of this information in daily clinical practice, we have developed an interactive web-based tool for calculating conditional survival that adjusts not only for the covariate effects but also for treatment and outcome differences associated with the stratified treatment groups (www.mdanderson.org/rectalcalculator). The calculator is a decision-support tool personalized to the patient, tumor, and treatment course. In contrast to traditional 5-year survival estimates where predictions are made for diverse groups of patients based on stage alone, the CS calculator can give individualized future survival estimates that also accounts for patient related factors such as age and race which have also been shown to be independently associated with traditional survival estimates.34, 35

Our study has both strengths and limitations inherent to the data source. Data on chemotherapy treatment is not available in SEER and therefore the impact of this treatment on CS estimates cannot be accounted for in the present analysis. However, most patients who undergo radiotherapy for rectal cancer in the U.S. undergo combined modality chemoradiotherapy, both pre-operatively and post-operatively, based on multi-institutional randomized data.15, 27, 36, 37 SEER also does not include data on medical co-morbidities or postoperative complications that may impact survival estimates; however we have utilized cancer-specific survival estimates and have additionally confirmed our findings using relative survival. Furthermore, we have excluded cases with death within 30 days to minimize the confounding effect of early post-operative mortality. There are also limitations in SEER staging information for patients that have received neoadjuvant therapy because SEER staging does not distinguish between clinical and pathologic stage. Therefore, patients who achieve a pathologic complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy may be coded in SEER as unknown T or N stage, representing a small cohort of patients who evaluation is uniquely limited in SEER. As SEER does not have a classifier for pathologic complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, many of these patients will be classified as unstaged (due to lack of available viable tumor) and therefore our calculator cannot be applied to these patients. However, these patients have been shown to have excellent prognosis that is better than that of patients with residual stage I disease.18, 38 It should also be noted that the CS estimates are based on patients alive at each time point without information regarding disease status (i.e. alive with or without evidence of disease), thus for individuals whose disease status is known, a small variance of the actual CS from the CS estimates can be expected. Finally as advances in effective systemic treatment regimens have improved survival outcomes in recent years, our analysis may potentially underestimate the survival outcomes, particularly for patients with localized disease.

In summary we report on covariate adjusted, treatment-stratified, conditional survival outcomes among rectal cancer patients and have created an internet-based electronic tool for real-time information to estimate CS and facilitate patient counseling. In so doing we have accounted for variations in outcome which are related to initial treatment decisions. These estimates may be useful to clinicians in counseling patients on prognosis and in planning future treatment and intensity of surveillance for rectal cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Supported in part by research grants from the American Society of Clinical Oncology Conquer Cancer Foundation (GJC) and the National Institutes of Health, K07-CA133187 (GJC).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, Orlando, Florida, January 22-24, 2010.

Author contributions: Bowles: Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising, and final approval of version to be published.

Hu: Conception and design, acquisition and analysis of data, revising, and final approval of version to be published.

You: Analysis and interpretation of data, revising, and final approval of version to be published.

Skibber: Interpretation of data, revising, and final approval of version to be published.

Rodriguez-Bigas: Interpretation of data, revising, and final approval of version to be published.

Chang: Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising, and final approval of version to be published

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang GJ, Hu CY, Eng C, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. Practical application of a calculator for conditional survival in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5938–5943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR, Jr, Wang SJ. Conditional survival in ovarian cancer: results from the SEER dataset 1988-2001. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis FG, McCarthy BJ, Freels S, Kupelian V, Bondy ML. The conditional probability of survival of patients with primary malignant brain tumors: surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) data. Cancer. 1999;85:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuller CD, Wang SJ, Thomas CR, Jr, Hoffman HT, Weber RS, Rosenthal DI. Conditional survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: results from the SEER dataset 1973-1998. Cancer. 2007;109:1331–1343. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henson DE, Ries LA, Carriaga MT. Conditional survival of 56,268 patients with breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;76:237–242. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950715)76:2<237::aid-cncr2820760213>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SJ, Emery R, Fuller CD, Kim JS, Sittig DF, Thomas CR. Conditional survival in gastric cancer: a SEER database analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:153–158. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xing Y, Chang GJ, Hu CY, et al. Conditional survival estimates improve over time for patients with advanced melanoma: results from a population-based analysis. Cancer. 116:2234–2241. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang SJ, Fuller CD, Emery R, Thomas CR. Conditional Survival in Rectal Cancer: A SEER Database Analysis. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2007;1:84–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merrill RM, Hunter BD. Conditional survival among cancer patients in the United States. Oncologist. 15:873–882. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang SJ, Fuller CD, Kim JS, Sittig DF, Thomas CR, Jr, Ravdin PM. Prediction model for estimating the survival benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy for gallbladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2112–2117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soong SJ, Ding S, Coit D, et al. Predicting survival outcome of localized melanoma: an electronic prediction tool based on the AJCC Melanoma Database. Ann Surg Oncol. 17:2006–2014. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1050-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher B, Wolmark N, Rockette H, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy for rectal cancer: results from NSABP protocol R-01. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:21–29. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer. Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:980–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connell MJ, Martenson JA, Wieand HS, et al. Improving adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer by combining protracted-infusion fluorouracil with radiation therapy after curative surgery. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:502–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Eng C, Skibber JM. Lymph node status after neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer is a biologic predictor of outcome. Cancer. 2009;115:5432–5440. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park IJ, You YN, Agarwal A, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment response as an early response indicator for patients with rectal cancer. J Clinl Onc. 2012;30:1770–1776. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) Limited-Use Data (1973-2004), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2007, based on the November 2006 submission.

- 20.Greene F, Page D, Fleming I, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Sixth. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1982;69:239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 22.May S, Hosmer DW. Handbook of Statistics: Survival Analysis. North-Holland: 2004. Hosmer and Lemeshow Type Goodness-of-Fit Statistics for the Cox Proportional Hazards Model. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Recovery issues in cancer survivorship: a new challenge for supportive care. Cancer J. 2006;12:432–443. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kattlove H, Winn RJ. Ongoing care of patients after primary treatment for their cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:172–196. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.3.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C, et al. Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early-stage patients. Health Psychol. 1999;18:159–168. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellon S, Kershaw TS, Northouse LL, Freeman-Gibb L. A family-based model to predict fear of recurrence for cancer survivors and their caregivers. Psychooncology. 2007;16:214–223. doi: 10.1002/pon.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tepper JE, O'Connell M, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Final Report of INT 0114: Adjuvant Therapy in Rectal Cancer--Analysis by Treatment, Stage and Gender. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;20 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8688–8696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheeler JM, Dodds E, Warren BF, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy and total mesorectal excision surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer: correlation with rectal cancer regression grade. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:2025–2031. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quah HM, Chou JF, Gonen M, et al. Pathologic stage is most prognostic of disease-free survival in locally advanced rectal cancer patients after preoperative chemoradiation. Cancer. 2008;113:57–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 11:835–844. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a systematic overview of 8,507 patients from 22 randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;358:1291–1304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang GJ, Skibber JM, Feig BW, Rodriguez-Bigas M. Are we undertreating rectal cancer in the elderly? An epidemiologic study. Annals of surgery. 2007;246:215–221. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318070838f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Artinyan A, Mailey B, et al. An interaction of race and ethnicity with socioeconomic status in rectal cancer outcomes. Annals of surgery. 2011;253:647–654. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182111102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tepper JE, O'Connell M, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Adjuvant therapy in rectal cancer: analysis of stage, sex, and local control--final report of intergroup 0114. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1744–1750. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roh MS, Colangelo LH, O'Connell MJ, et al. Preoperative multimodality therapy improves disease-free survival in patients with carcinoma of the rectum: NSABP R-03. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5124–5130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collette L, Bosset JF, den Dulk M, et al. Patients with curative resection of cT3-4 rectal cancer after preoperative radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy: does anybody benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy? A trial of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiation Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4379–4386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]