Recently, several major cases of fraud in science were exposed in the Netherlands [1–3]. Unfortunately, the case of Don Poldermans from Erasmus University outlined that this scientific misbehaviour has also affected cardiovascular science, [3] after previous shocking cases in medicine, [4] including the Woo-Suk Hwang debacle on cell stem technology published by Science [5] (see ref. [6] for an extensive analysis of the case). During the editorship of Michiel J. Janse (and my associate editorship) of Cardiovascular Research (1995–2002), there were no retractions, although some investigations were initiated. However, there were five retractions over the subsequent 10 years under the co-editorship of Michael H. Piper and David Garcia-Dorado [7].

An increase in retractions suggests that fraud in science is a problem of increasing importance. Of course, editors and reviewers alike have neither been educated to act as data police officers, nor is it their primary goal to search for fraud [6]. Still, they are the only gatekeepers we have for maintaining moral and ethical standards in science when authors fail in this respect. For this reason it is important that editors act responsibly. During the last years several journals were banned from the Journal Citation Reports, a product of Thomson Reuters, which implies that a journal is not assigned an impact factor for several years. The main reason for this was excessive self-citation by journals, which ‘inflates’ the impact factor of a journal compared with its value were it solely based on citations obtained from other journals. The fact that papers in a certain journal are more often cited by that same journal than would be expected from citation by other journals is not a new observation. It has been demonstrated and analysed previously [8, 9]. Of course, both author self-citation and journal self-citations are in themselves useful, relevant and functional when it comes to transfer of knowledge. It becomes a problem when journal self-citation serves a merchandising rather than a scientific goal, i.e. when authors are pushed to include citations with the primary goal of increasing the impact factor of the journal that is going to publish their paper. This could be labelled as ‘coercing citation’.

Coercive citation

Recently, Wilhite and Fong [10] published an alarming report on coercive citation practices of editors. In its most extreme version ‘Coercive citation’ should be understood as a request by editors to add citations to a submitted manuscript of papers published by their own journal with the implicit threat of rejection of the manuscript if the ‘advice’ is not followed. A ‘milder’ version might be the request to include an additional reference at or close to the time of acceptance of a manuscript. Wilhite and Fong [10] analysed 6672 responses to surveys sent to authors working in the Web of Science/Journal Citation Reports categories economics, sociology, psychology and business (marketing, management, finance, information systems and accounting). Furthermore they associated the responses with data on 832 journals in which these authors published. The outcome was quite remarkable. More than 20% (175) of these journals were identified as ‘coercers’. At the same time 20% of the respondents reported to have been victim of coercion themselves. About 85% of the respondents indicated that they considered this practice as inappropriate; still almost 60% declared that they were going to add superfluous references when submitting to a coercive journal, which means that they tend to respond to coercion even before they have been coerced.

Journal self-citation: striking examples

One is easily inclined to think that malpractice is more usual in scientific specialities far away from one’s own. I was therefore surprised by a paper entitled ‘Highlights of the year 2011 in JACC’ published by the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC). The ‘Highlights’ were published on pages 503–537 in issue 5 of volume 59 of the JACC (for reasons that will become obvious, I did not include this paper in the list of references of this brief Editorial). The intention of the Editors of JACC may have been to pay extra attention to what they consider their most important papers. However, if one aims at corroboration of the scientific context of these papers, one would expect attention for a reference framework, including previous papers in other journals and, if possible, also later published papers rather than a mere enumeration of papers already published by the same journal. The ‘Highlights of the year 2011 in JACC’ came with 292 references. Of these 266 referred to a JACC 2011 paper, 6 to a JACC 2010 paper, 4 to papers published by JACC in years earlier than 2010 and only 16 to other journals. The effect is that 266 + 6 = 272 references influence the impact factor of JACC for the year 2012. Because JACC published 881 so-called source papers in the years 2010 plus 2011, this number of extra citations will increase JACC’s 2012 impact factor by 272/881 = 0.309, only based on this single paper. It may be a coincidence, but at the time of publication of the ‘Highlights of the year 2011’ the difference in impact factor 2010 between Circulation (rank 1 in the cardiovascular category) and JACC (rank 2) was 0.139…. In our opinion, Editors should not try to increase the visibility of their journal in this way.

JACC is not the only journal publishing this type of papers. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol [11] and also Neth Heart J [12] also published an article in 2012 in which they highlighted papers published in the previous years. There is, however, nothing wrong with paying attention to best read or cited papers (but see Phil Davis in “The Scholarly Kitchen”, January 2013). Thus, Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol [11] referred to 13 of its own papers and to another 13 papers of the parent journal (Circulation) all published in 2010 and 2011. The Neth Heart J [12] had 24 self-citations. The contribution to the impact factors 2012 by these papers will be 0.069 for Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 0.011 for Circulation and 0.153 for Neth Heart J.

Although not essentially different, 13 or 24 journal self-citations is at another level than the 272 journal self-citations of JACC.

Effect of journal self-citations on the impact factor

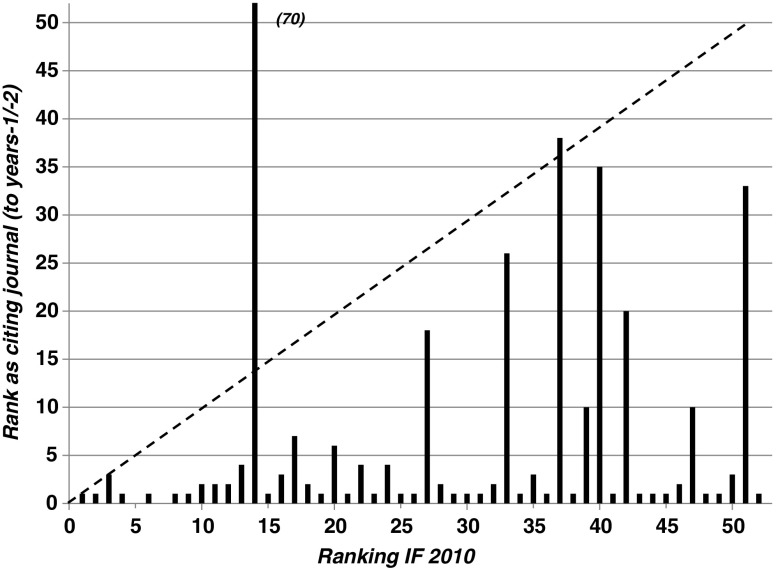

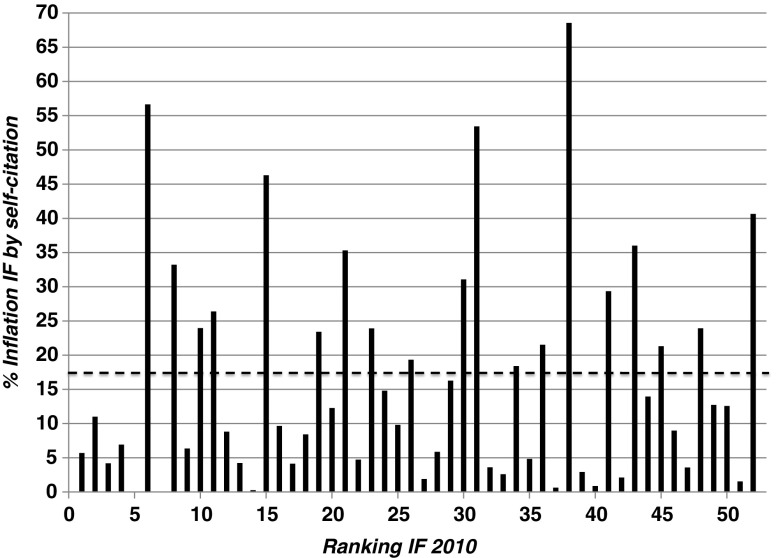

I have quantified the extent to which journal self-citations, of course ‘caused’ by author citations (that can, but need not to be author self-citations as well), increase impact factors of journals belonging to the Web of Science category ‘Cardiac and Cardiovascular Systems’. To this end, I evaluated the impact factor of 2010 as published by Thomson Reuters in its product Journal Citation Reports (2010). It concerns citations obtained during 2010 to papers published in 2008 and 2009. I focused on the top 50 journals (in practice rank numbers 1–4, 6, 8–52 because of incomplete data for two journals ranked at 5 and 7). Figure 1 shows these top 50 journals ranked from 1 to 52 along the abscissa. The ordinate shows the position of the same journal in a listing of all citing journals from which their citations were obtained. If the pattern were to follow the dashed line, this would imply that the journal, at whatever IF 2010 rank, would also be at that position as citing journal to itself. Obviously, this is not the case, many journals are at citing position 1 to themselves, even when their IF ranking is close to 50. The ranking as citing journal (Fig. 1) in itself is not informative concerning the amount of inflation of the impact factor by journal self-citation. Figure 2 shows this percentage of inflation. It was calculated as IF 2010 including self-citations minus IF 2010 without self-citations divided by IF without self-citations times 100. On average, the ‘% inflation’ is 17 ± 16 (mean ± SD, see the dashed line). However, the differences amongst journals are substantial. There are 8 journals with inflation scores above one third (33 %). The amount of inflation does not relate to the position along the abscissa. It is quite surprising that the percentage of inflation of the impact factor 2010 is very high for two of the top-10 journals (57% for the International Journal of Cardiology and 33 % for Basic Research in Cardiology; see Fig. 2) compared with the other journals in the top-10. Without further research one needs to be careful in labelling this self-citation as excessive, let alone as ‘coercive citation’ as described by Wilhite and Fong [10] for journals in other categories of the Web of Science (see above). On the other hand, it is improbable that the large difference with the other journals in the top-10 can be explained by more specialisation of those two journals compared with journals as Circulation or Circulation Research, to mention but two. For Circulation Journal at rank 38 (Fig. 2) the percentage of inflation of the impact factor was highest at 69% [for the Neth Heart Journal, ranked at 70 and therefore not included in Figs. 1 and 2, the rank position as citing journal to Neth Heart J was 6 (compare with Fig. 1), whereas the percentage of inflation was 10% (compare with Fig. 2)].

Fig. 1.

Ranking of cardiovascular journals (abscissa) according to the impact factor (IF) 2010 as published by Thomson Reuters in the Journal Citation Reports 2010 against the position of these journals as citing journals contributing to their IF (ordinate). For each journal the citing journals to the years relevant for the IF 2010 (citations in 2010 to publication years 2008 and 2009; years ‘n-1’ and ‘n-2’) were ranked. The position of each journal as citing journal to itself can be read along the abscissa. (The value ‘70’ is added to the journal at rank 14, because the ordinate was truncated)

Fig. 2.

Ranking of cardiovascular journals (abscissa) according to the impact factor (IF) 2010 as published by Thomson Reuters in the Journal Citation Reports 2010 against the amount of inflation of the IF 2010 by journal self-citation (ordinate; see text for explanation)

In conclusion, it is obvious that journal self-citation amongst cardiovascular journals is substantial. Practices as described in the previous paragraph would certainly contribute to this phenomenon. It is once more emphasised that a high percentage of journal self-citation is quite reasonable when a journal in a category harbours a distinct subspecialisation. Finer tuning of the parameters to measure excessive journal self-citation is desirable, if we want to prevent manipulation of bibliometrical parameters [13].

Acknowledgement

I am grateful for the critical comments of Ruben Coronel, Michiel J. Janse, Loet Leydesdorff and Arthur Wilde.

Post-scriptum

After acceptance of this Editorial Comment, I noticed that JACC also published such ‘Highlights of the year’ in the years 2005–2011 and recently in 2013, each time primarily referring to papers published during the previous year. The total number of references in these ‘Highlights’ gradually increased from 107 in 2005 to 292 in 2012 (see above). The 2013 ‘version’ had 261 references.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Anonymous. www.science20.com/science_20/blog/ statistically_highly_unlikely_social_psychologist_dirk-smeesters_resigns-91449.

- 2.Anonymous. www.nwo.nl/nwohome.nsf/pages/NWOP_92GGC7.

- 3.Anonymous. www.escardio.org/about/press/press-releases/pr-11/pages/dismissal-don-poldermans.aspx

- 4.Farthing MJG. Research misconduct: diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1605–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy D. Editorial retraction. Science. 2006;311:335. doi: 10.1126/science.1124926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Heyden MAG. Derks van de Ven T, Opthof T. Fraud in science: the stem cell seduction. Implications for the peer review process. Neth Heart J. 2009;17:25–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03086211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Web of Science, Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia (data extraction at 14 December 2012).

- 8.De Solla Price D. The Analysis of Square Matrices of Scientometric Transactions. Scientometrics. 1981;3:55–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02021864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noma E. An Improved Method for Analyzing Square Scientometric Transaction Matrices. Scientometrics. 1982;4:297–316. doi: 10.1007/BF02021645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilhite AW, Fong EA. Coercive citation in academic publishing. Science. 2012;335:542–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1212540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Editors Circulation Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology Editor’s picks. Most read articles on arrhythmia devices (defibrillation, pacing, pacemakers, heart arrest, and resuscitation) Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:e69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Wall EE, The NHJ. 2012 in retrospect: which articles are cited most? Neth Heart J. 2012;19:481–2. doi: 10.1007/s12471-012-0336-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opthof T, Wilde AAM. Bibliometrical data in clinical cardiology revisited. The case of 37 Dutch professors. Neth Heart J. 2011;19:246–55. doi: 10.1007/s12471-011-0128-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]