Abstract

Background

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) are designed to deliver shocks or antitachycardia pacing (ATP) in the event of ventricular arrhythmias. During follow-up, some ICD recipients experience the sensation of ICD discharge in the absence of an actual discharge (phantom shock). The aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence and predictors of phantom shocks in ICD recipients.

Methods

Medical records of 629 consecutive patients with ischaemic or dilated cardiomyopathy and prior ICD implantation were studied.

Results

With a median follow-up of 35 months, phantom shocks were reported by 5.1 % of ICD recipients (5.7 % in the primary prevention group and 3.7 % for the secondary prevention group; p=NS). In the combined group of primary and secondary prevention, there were no significant predictors of the occurrence of phantom shocks. However, in the primary prevention group, phantom shocks were related to a history of atrial fibrillation (p=0.03) and NYHA class <III (p=0.05). In the secondary prevention group, there were no significant predictors for phantom shocks.

Conclusion

Phantom shocks occur in approximately 5 % of all ICD recipients. In primary prevention patients, a relation with a history of atrial fibrillation and NYHA class <III were significant predictors for the occurrence of phantom shocks. In the secondary prevention patients, no significant predictors were found.

Keywords: Implantable defibrillator, Primary prevention, Secondary prevention, Phantom shock, Psychological consequences

Introduction

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) are designed to prevent sudden cardiac death (SCD) by converting ventricular arrhythmias into a normal rhythm by the use of antitachycardia pacing (ATP) or shock therapy. After several primary and secondary prevention trials, the ICD has proven efficacy in the prevention of SCD. Following the current guidelines, both patients with ischaemic or dilated cardiomyopathy (CMP) and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35–40 % (primary prevention), and patients who have already survived ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia with haemodynamic instability (secondary prevention) are candidates for ICD implantation. [1–4] Despite improvements in the ICD technology, complications are still common. [5] One of the least known complications is phantom shock. In 1992, Kowey et al. described the first patient to present with the experience of a shock without an actual ICD discharge. [6] The incidence of phantom shocks in ICD recipients has remained relatively unknown, as are the risk factors for its appearance.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence and predictors of phantom shocks in ICD recipients with ischaemic or dilated CMP.

Methods

Patients

All patients with ischaemic or dilated CMP who received an ICD between January 2006 and December 2009 at the Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands were selected from the hospital database. The indications for ICD implantation were ischaemic or dilated cardiomyopathy with an LVEF ≤35–40 % (primary prevention) or prior ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia with haemodynamic instability according to the European guidelines (secondary prevention). [4] Demographic, clinical, and follow-up data were collected by careful review of hospital records. After implantation, regular visits to the ICD outpatient clinic were scheduled every 3–6 months and after every experienced ICD discharge. Phantom shocks were defined as the experience of an ICD discharge reported by the patient, without an actual ICD discharge seen by device interrogation.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (range) as appropriate, and categorical data are summarised as frequencies and percentages. Differences in clinical characteristics between groups were analysed using Student’s T-test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and chi square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The time course was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. To examine the risk factors, each variable was first entered into a univariate model, and those found to be significant at a level of P < 0.20 were then entered into the multivariate Cox regression analysis. Subsequently, non-significant variables were removed, one by one, until the model had significantly deteriorated as indicated by the -2 log likelihood.

Results

Demographics

Data from 629 consecutive ICD recipients (age 64.0 years, LVEF 29.6, 81.4 % male, 68.9 % ischaemic aetiology) were collected. In total, 441 patients (70.1 %) received the ICD for primary prevention reasons. The median follow-up was 35.0±13.6 months.

Influence of clinical variables on occurrence of phantom shocks

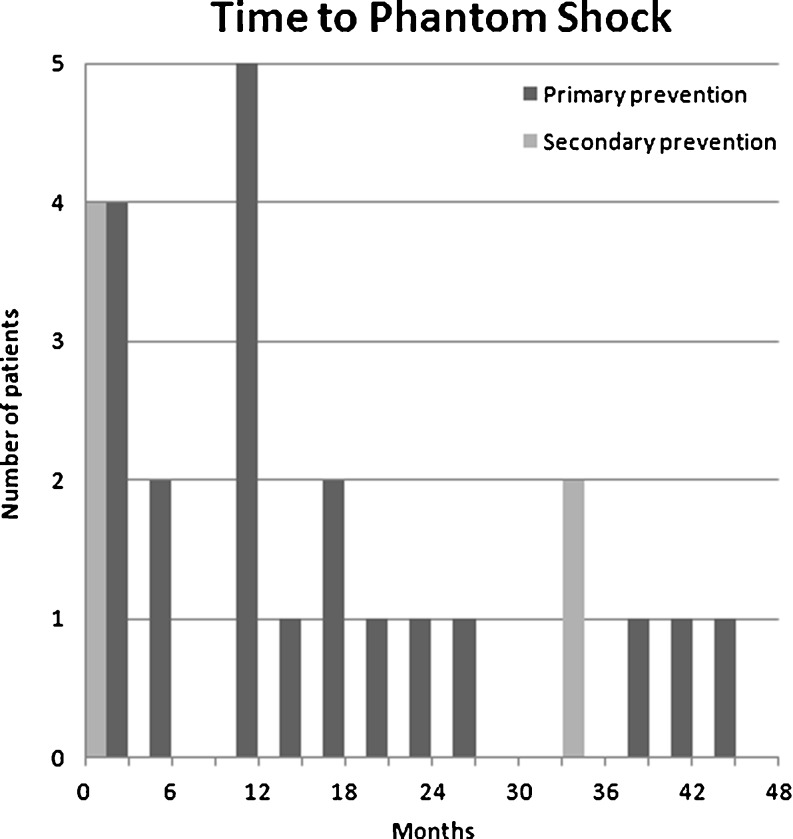

A phantom shock was experienced by 32 patients (5.1 %). The median time to phantom shock was 13 months (range 0–43 months; Fig. 1). There was a trend for phantom shock to occur earlier in patients who received their ICD for secondary prevention (p=0.14). Overall, after univariate and multivariate analysis, there was no significant predictor of the occurrence of phantom shocks. Statistical trends were found for a history of atrial fibrillation (p=0.11), New York Heart Association (NYHA) class <III (p=0.07) and prior appropriate shock therapy (p=0.09). All data can be found in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Time to phantom shock in months, stratified by indication of ICD implantation

Table 1.

Demographic differences stratified by phantom shocks

| Phantom shock (n=32) | No phantom shock (n=597) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years ±SD) | 62.4±13.0 | 64.1±9.8 | 0.36 |

| Male gender | 25 (78.1 %) | 487 (81.6 %) | 0.63 |

| LVEF (% ±SD) | 27.7±3.6 | 27.2±4.5 | 0.57 |

| Aetiology | 0.24 | ||

| Ischaemic | 25 (78.1 %) | 407 (68.3 %) | |

| Non-ischaemic | 7 (21.9 %) | 189 (31.7 %) | |

| Indication | 0.31 | ||

| Primary prevention | 25 (78.1 %) | 416 (69.7 %) | |

| Secondary prevention | 7 (21.9 %) | 181 (30.3 %) | |

| History | |||

| Hypertension | 8 (25.0 %) | 145 (24.4 %) | 0.94 |

| COPD | 3 (9.4 %) | 63 (10.6 %) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (15.6 %) | 132 (22.2 %) | 0.38 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13 (40.6 %) | 165 (27.7 %) | 0.11 |

| NYHA class <III | 5 (15.6 %) | 185 (31.5 %) | 0.07 |

| Prior shock therapy | 10 (31.3 %) | 122 (20.4 %) | 0.23 |

| Appropriate | 8 (25.0 %) | 78 (13.1 %) | 0.09 |

| Inappropriate | 4 (12.5 %) | 49 (8.2 %) | 0.50 |

| Prior ATP therapy | 8 (25.0 %) | 105 (17.6 %) | 0.40 |

All variables are in numbers (percentages) unless otherwise specified. LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA New York Heart Association functional class, ATP antitachycardia pacing

Primary prevention patients

In the primary prevention group (n=441; Table 2), 25 patients (5.7 %) experienced a phantom shock. The median time to shock was 12 months (range 0–45 months). After univariate analysis, there was a significant relation between a history of atrial fibrillation and the occurrence of phantom shocks (p=0.04). Statistical trends were found for NYHA class <III (p=0.07), ischaemic aetiology of cardiomyopathy (p=0.18), and prior shock therapy (p=0.19), especially appropriate shock therapy (p=0.11). After multivariate analysis, a history of atrial fibrillation (p=0.03) and NYHA class <III (p=0.05) remained significant.

Table 2.

Demographic differences in primary prevention ICD recipients, stratified by phantom shocks

| Phantom shock (n=25) | No phantom shock (n=416) | P uni | P multi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years ±SD) | 62.4±12.1 | 63.8±9.5 | 0.49 | NS |

| Male gender | 18 (72.0 %) | 341 (81.4 %) | 0.21 | NS |

| LVEF (% ±SD) | 28.8±13.5 | 25.6±12.6 | 0.22 | NS |

| Aetiology | 0.18 | NS | ||

| Ischaemic | 19 (76.0 %) | 260 (62.5 %) | ||

| Non-ischaemic | 6 (24.0 %) | 156 (37.5 %) | ||

| History | ||||

| Hypertension | 6 (24.0 %) | 91 (21.9 %) | 0.81 | NS |

| COPD | 2 (8.0 %) | 49 (11.8 %) | 0.76 | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (20.0 %) | 99 (23.8 %) | 0.36 | NS |

| Atrial fibrillation | 11 (44.0 %) | 107 (25.8 %) | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| NYHA class <III | 5 (20.0 %) | 158 (38.0 %) | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Prior shock therapy | 7 (28.0 %) | 67 (16.1 %) | 0.19 | NS |

| Appropriate | 5 (20.0 %) | 38 (9.1 %) | 0.11 | NS |

| Inappropriate | 3 (12.0 %) | 34 (8.2 %) | 0.59 | NS |

| Prior ATP therapy | 6 (24.0 %) | 57 (13.7 %) | 0.23 | NS |

All variables are in numbers (percentages) unless otherwise specified. LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NYHA New York Heart Association functional class, ATP antitachycardia pacing

Secondary prevention patients

In the secondary prevention group (n=187; Table 3), 7 patients (3.7 %) experienced a phantom shock. The median time to shock was 1 month (range 0–33 months). There were no significant predictors for the occurrence of phantom shocks.

Table 3.

Demographic differences in secondary prevention ICD recipients, stratified by phantom shocks

| Phantom shock (n=7) | No phantom shock (n=180) | Puni | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years ±SD) | 62.4±17.0 | 64.7±10.5 | 0.74 |

| Male gender | 7 (100 %) | 146 (80.7) | 0.35 |

| LVEF (% ±SD) | 22.2±17.2 | 41.8±25.9 | 0.22 |

| Aetiology | 1.00 | ||

| Ischaemic | 6 (85.7 %) | 147 (81.7 %) | |

| Non-ischaemic | 1 (14.3 %) | 33 (18.3 %) | |

| History | |||

| Hypertension | 2 (28.6 %) | 54 (30.3 %) | 1.00 |

| COPD | 1 (14.3 %) | 14 (7.8 %) | 0.45 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0 %) | 33 (18.4 %) | 0.36 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (28.6 %) | 58 (32.2 %) | 1.00 |

| NYHA <III | 0 (0.0 %) | 27 (14.9 %) | 0.60 |

| Prior shock therapy | 3 (42.9 %) | 55 (30.4 %) | 0.68 |

| Appropriate | 3 (42.9 %) | 40 (22.1 %) | 0.20 |

| Inappropriate | 1 (14.3 %) | 15 (8.3 %) | 0.47 |

| Prior ATP therapy | 2 (28.6 %) | 48 (26.6 %) | 1.00 |

All variables are in numbers (percentages) unless otherwise specified. LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NYHA New York Heart Association functional class, ATP antitachycardia pacing

Discussion

In our cohort, during a mean follow-up of 35 months, 5.1 % of the ICD recipients experienced phantom shocks. In the primary prevention group, phantom shocks occurred in 5.7 % versus 3.7 % in the secondary prevention group. Regarding risk factors, in the primary prevention group there was a significant relation between occurrence of phantom shocks and a history of atrial fibrillation and NYHA class <III. In the secondary prevention group, no significant predictors were found.

Phantom shocks were first reported by Kowey et al. in 1992, [6] yet the incidence of phantom shocks remains unknown. There are only two cohort studies dealing with phantom shocks in ICD patients. In an abstract, Swygman et al. described a cohort of 445 patients with a median follow-up of 28 months where phantom shocks occurred in 30 (6.7 %) patients [7] and in a recent study Wojcicka et al. described 55 young ICD patients in which phantom shocks occurred in 21 % of the patients. [8] In our cohort, phantom shocks were experienced by 5.1 %, which is comparable with Swygman’s cohort, but lower than Wojcicka’s cohort. Our cohort is not comparable with that described by Wojcicka in terms of age and disease aetiology.

In the primary prevention group in our cohort, a history of atrial fibrillation (especially paroxysmal atrial fibrillation) and NYHA class <III were significantly related to the occurrence of phantom shocks. In the literature, no supportive data were found for these relations. A possible explanation for the relation between a history of atrial fibrillation and the experience of phantom shocks is the misinterpretation of the symptoms associated with the occurrence of atrial fibrillation. [9, 10]

It is suggested that anxiety and depression play a role in the occurrence of phantom shocks. In a case–control study by Prudente et al., it was shown that patients with phantom shocks had higher levels of anxiety and depression than the controls. [11] However, since the data were collected after the (phantom) shock occurred, it is difficult to determine whether the higher levels of anxiety and depression triggered the experience of phantom shock or visa versa. Swygman et al. noticed that phantom shocks mainly occurred in the first 6 months after implantation. [7] Similarly, in our study, most phantom shocks occurred early after implantation. A possible explanation for this might be the higher anxiety levels during the first months as a result of the implantation procedure or (in the secondary prevention group) a recently survived cardiac arrest. In our study we did not see a statistically significant difference between the primary and secondary prevention group regarding the median time to the phantom shock; however, this can be due to the small number of patients with phantom shocks in the secondary prevention group.

After appropriate shock therapy, it has been shown that levels of self-reported anxiety rise ; [12] it could therefore be hypothesised that also prior ICD therapy might be associated with the occurrence of phantom shocks. In our study, shock therapy (both appropriate or inappropriate) was more frequent in the group with phantom shocks, but this did not reach statistical significance. Longer follow-up may be wanted, since in most of the included patients ICD therapy occurred in the last phase of the follow-up. In the literature, the relation between appropriate shock therapy and phantom shocks is not clear either. Neither Swygman nor Jacob et al. found a relation with single appropriate shocks. [7, 13] Electrical storms, however, were related to higher anxiety levels and phantom shocks.[13] Prospective studies are needed to answer questions about the influence of shock therapy, the psychological determinants of phantom shocks in the ICD population, consequences for post-implantation care and possible psychological intervention [14] to reduce the number of patients experiencing phantom shocks.

Limitations

Our study is limited by several factors. The most important limitation is the observational design of this study, and therefore the lack of (prospective) psychological data and the possibility of underestimation of the occurrence of phantom shocks. Other limitations are the relatively low number of patients with phantom shocks, especially in the secondary prevention group and the relatively short follow-up.

Conclusion

With a median follow-up of 35 months, phantom shocks occur in 5 % of the ICD recipients. In the primary prevention group, a history of atrial fibrillation and/or NYHA class <III was related to the occurrence of phantom shocks. In the secondary prevention patients, no significant predictors were found.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest & funding

None

References

- 1.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee DS, Green LD, Liu PP, et al. Effectiveness of implantable defibrillators for preventing arrhythmic events and death: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(9):1573–1582. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114(10):e385–e484. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Welsenes GH, Borleffs CJ, van Rees JB, et al. Improvements in 25 years of implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy. Neth Heart J. 2011;19(1):24–30. doi: 10.1007/s12471-010-0047-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kowey PR, Marinchak RA, Rials SJ. Things that go bang in the night. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(26):1884. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212243272614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swygman CA, Link M, Cliff D, et al. Incidence of phantom shocks in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:810. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wojcicka M, Lewandowski M, Smolis-Bak E, et al. Psychological and clinical problems in young adults with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Kardiol Pol. 2008;66(10):1050–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari AK, Anderson JL, Gilbert EM, et al. Correlation of symptoms with occurrence of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia or atrial fibrillation: a transtelephonic monitoring study. The Flecainide Supraventricular Tachycardia Study Group. Am Heart J. 1992;124(2):381–386. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90601-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang Y. Relation of atrial arrhythmia-related symptoms to health-related quality of life in patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation: a community hospital-based cohort. Heart Lung. 2006;35(3):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prudente LA, Reigle J, Bourguignon C, et al. Psychological indices and phantom shocks in patients with ICD. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2006;15(3):185–190. doi: 10.1007/s10840-006-9010-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Broek KC, Nyklicek I, van der Voort PH, et al. Shocks, personality, and anxiety in patients with an implantable defibrillator. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31(7):850–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob S, Panaich SS, Zalawadiya SK, et al. Phantom shocks unmasked: clinical data and proposed mechanism of memory reactivation of past traumatic shocks in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2012;34(2):205–213. doi: 10.1007/s10840-011-9640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erdman RA, Pedersen SS. Clinical and scientific progress related to the interface between cardiology and psychology: lessons learned from 35 years of experience at the Thoraxcenter of the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam. Neth Heart J. 2011;19(11):470–476. doi: 10.1007/s12471-011-0190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]