Abstract

Under the auspices of a partnership grant to reduce cancer health disparities, Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) partnered with the Ponce School of Medicine to identify the perceived cultural communication needs of MCC healthcare providers regarding Hispanic patients with limited or no English skills. Oncologists (N=72) at MCC were surveyed to identify the specific areas of cultural communication techniques for which they desired to receive additional training. The majority of participants (66%) endorsed an interest in obtaining training to communicate difficult issues (terminal illness, controversial diagnosis) in a manner respectful to Hispanic culture. A workshop was conducted with providers (N=55) to improve cultural communication between Hispanic patients and families focusing on culture, terminal illness, and communication strategies. Findings from a pre–post test indicate an overall positive response to the workshop. Results from this study can help inform future efforts to enhance cultural competency among health providers.

Keywords: Oncology, Health care, Cancer disparity, Cultural communication

Introduction

An alliance between a patient’s cultural identity and a physician’s cultural competency can improve patient–physician communication and ultimately reduce health disparities [1]. However, communication barriers in the patient–physician relationship contribute to health disparities in the cancer care setting [4]. Providers are often unaware of their communication skill level and biases and may perceive their skills that do not need improvement [4]. Culture, often defined as the set of attitudes, beliefs, and values that people and societies pass down between generations, can have a significant impact on patient’s beliefs and expectations in the health care setting. Furthermore, these beliefs can influence their expectations and responses to information about diagnosis and disease treatment. Health care providers have their own medical culture as well as individual assumptions about cultural mores and values of specific racial and ethnic groups, including those of which they are a member. When patient and provider have separate and distinct cultural beliefs and expectations, cultural mismatch occurs. Cultural mismatch can negatively impact the quality and effectiveness of health care as well as patient satisfaction and the relationship with the health care institution and provider. It has been suggested that “cultural competency” and an initial investment in cultural sensitivity on the part of the provider can help to minimize misunderstanding or conflict later, ultimately resulting in improved patient and provider satisfaction, more effective service delivery, increased capacity, and cost savings [2, 5].

Studies of Hispanic populations indicate that there are unique and distinct perceptions of the value of healthcare, expectations about physicians, and beliefs about cancer. Furthermore, Hispanics seeking healthcare in the US report increased barriers from not only the mismatch between expectations and realities but also language barriers and the receipt of healthcare services brokered through an interpreter.

The Cultural and Linguistically Appropriate Service on Healthcare Standards (CLAS) was developed by the Office of Minority Health of the US Department of Health and Human Services. The CLAS standards focus on cultural competence, language access services, and organizational support for culturally competent healthcare. The American Medical Association and the National Medical Association have consistently called for improvements in the cultural competency of physicians with CLAS standards providing a framework for the development of continuing medical education and medical school curricula. Additionally, the Joint Commission has recently released standards to encourage effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care, which will ultimately impact accreditation [7].

The Ponce School of Medicine and Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) formed an institutional partnership funded by the U56 funding mechanism from the National Cancer Institute. This partnership provided an opportunity to implement outreach and research initiatives to study, understand, and address the unique barriers to cancer care services among Hispanics. The leading component of this joint venture is to identify strategies to reduce cancer health disparities. The current study presented here focused on developing and evaluating a brief intervention for oncology care providers at MCC to improve cultural communication related to Hispanic patients and families.

Methods

At a community outreach event focused on cancer prevention and education for survivors and their families, Spanish-only speaking patients completed a brief survey on their perceptions of the cultural competence of healthcare providers at MCC. Responses showed that 90% (n=91) felt it was “important to be able to communicate in their preferred language with their physician” and 75% felt they were viewed as “knowing less” because they did not speak English. As a result of this patient survey, we identified cultural communication as a key need for physician training and created a survey to identify specific areas of need within that domain. The purpose of the survey was to identify health care provider needs for assistance to improve the cultural communication skills of those caring for Hispanic patients with limited or no English skills. These findings are similar to previously published data where interpersonal skills and effective communication are among the indicators of culturally sensitive health care reported by patients [8].

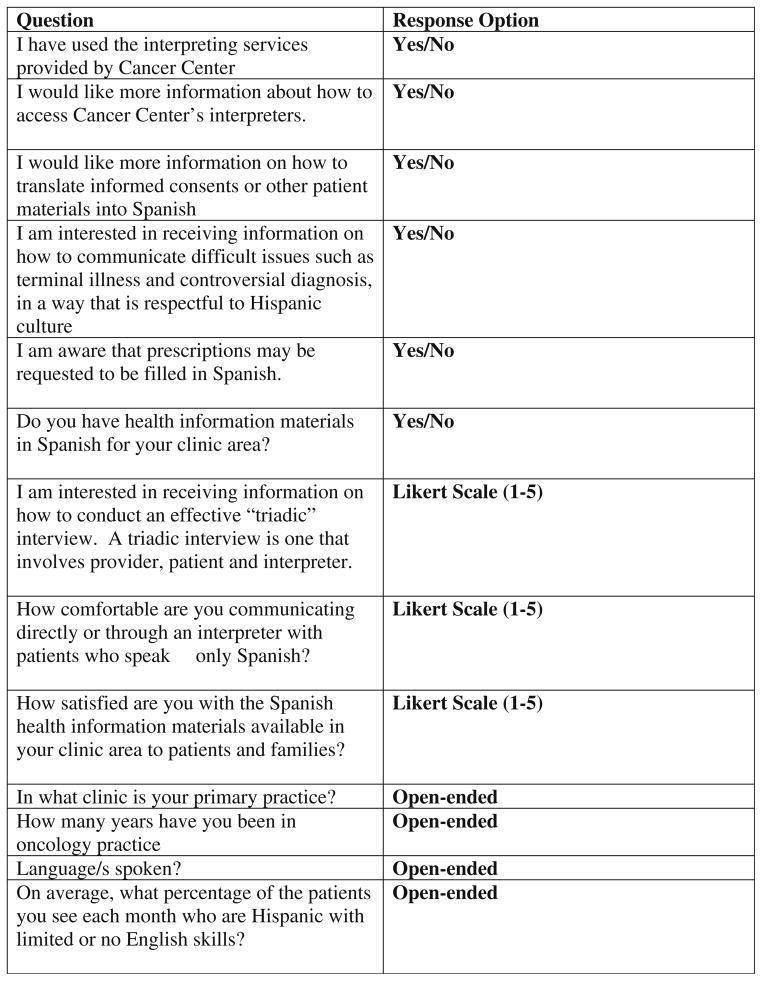

A brief internet survey was administered to the in-house staff of 166 medical oncologists and surgeons at MCC. The survey consisted of questions based on the CLAS standards (Fig. 1). The nine-item survey asked questions about attitudes, preferences, and current use of institutional services.

Fig. 1.

Cultural communication needs assessment

Results

At least two physicians from each of the 11 MCC clinics responded to the survey. A total of 72 respondents completed the survey yielding a response rate of 43% (n=72). As described in Table 1, 66% selected, “I am interested in receiving information on how to communicate difficult issues such as terminal illness and controversial diagnosis, in a way that is respectful to Hispanic culture.” Eighty-five percent had used the interpreting services at MCC and 19% reported desiring more information on how to access the interpreting services. Twenty-five percent selected they would like more information on how to translate informed consents and patient materials into Spanish.

Table 1.

Cultural communication needs assessment results (N=72)

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Use of services at MCC | ||

| Interpreting services | 61 (84.7) | 11 (15.3) |

| Aware prescriptions filled in Spanish | 44 (61.1) | 28 (38.9) |

| Have Spanish language materials in clinic Satisfaction | 52 (72.2) | 8 (11.1)* |

| With Spanish health materials in clinic | 30 (41.7) | 16 (22.3) |

| With your communication skills with Spanish only patients Interest | 59 (81.9) | 11 (17) |

| How to use interpreters | 14 (19.4) | 58 (80.6) |

| How to have materials and consents translated | 18 (25) | 54 (75) |

| How to communicate difficult issues | 48 (66.7) | 24 (33.3) |

| How to conduct triadic interview | 32 (44.4) | 40 (55.6) |

Discussion

Since the most selected topic was for the receipt of information on how to communicate difficult issues, a workshop was developed to address these issues. Four weeks later, an interactive workshop was held for staff consisting of a didactic lecture from a Hispanic provider addressing culture, terminal illness, and communication strategies. A panel of interpreters, translators, and bi-lingual providers answered questions from the audience, and a group discussion was held. Fifty-five health care providers attended the workshop. A seven-item pre-test was administered prior to the workshop, followed by a three-item post-test. Sixty-two percent agreed that the panel discussion was helpful in developing techniques for communicating bad news to Spanish-only speaking patients. At baseline, 20% of participants felt very comfortable with their cultural communication skills; however, only 3% felt very comfortable after attending the intervention. At pre-test, 25% reported having very little knowledge about the cultural context of breaking bad news to Hispanic patients, yet at post-test, 0% reported having very little knowledge. These data suggest the training was successful overall, as well as aiding in identifying providers who previously had a high level of comfort based on misperceptions of good cultural communication. It seems that through the workshop, some providers realized they needed improvement. Our results appear to be unique to other institutional attempts to improve cultural communications.

Conclusion

One study suggested that the traditional notion of competence in training as mastery of a finite body of knowledge may not be appropriate in regards to multicultural education training and suggest as an alternative cultural humility, which incorporates a commitment to self-reflection and lifelong learning [6]. This may be worthwhile to consider in future efforts to improve communication and reduce cancer disparities. Additionally, as the findings from this research suggest a “one size fits all” approach to “cultural competency training” may not be best to meet the varied needs of the diverse population impacted by cancer.

Though this was a relatively small sample size of both patients and providers and the results are not likely generalizable to all diverse patients seen at the Cancer Center, it is certainly a step toward improving sensitivity towards cultural communication and reducing disparities in this setting. Further research may include qualitative data collection (in-depth interviews or focus groups) with patients to ascertain not only perspectives of current care but also their priorities in the experience of illness and treatment [3] and to determine indicators of what they may consider to be culturally sensitive care. In addition, provider’s perspectives regarding barriers to using current services as well as assessment of preferred learning styles (interactive format versus on line tutorial) may be considered before future curriculum is developed or training is planned.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by NIH U56 grant CA118809 and CA157250.

Footnotes

Ethical standards I confirm all human studies have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Gwendolyn P. Quinn, Email: gwen.quinn@moffitt.org, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Julio Jimenez, Ponce School of Medicine, Ponce, Puerto Rico.

Cathy Meade, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Teresita Muñoz-Antonia, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Clement Gwede, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Eida Castro, Ponce School of Medicine, Ponce, Puerto Rico.

Susan Vadaparampil, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Vani Simmons, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Jessica McIntyre, Email: Jessica.McIntyre@moffitt.org, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA.

Theresa Crocker, Health Outcomes and Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC-CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA.

Thomas Brandon, College of Medicine, Department of Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

References

- 1.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graves DL, Like RC, Kelly N, Hohensee A. Legislation as intervention: a survey of cultural competence policy in health care. J Health Care Law Pol. 2007;10:339–361. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1713–1719. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surbone A. Cultural competence in the practice of oncology. Paper presented at the Grand Rounds Moffitt Cancer Center; Tampa. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Joint Commission. The Joint Commission: advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care: a roadmap for hospitals. The Joint Commission; Oakbrook Terrace: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker CM, Herman KC, Pedersen TR, Higley B, Montrichard M, Ivery P. Cultural sensitivity in physician-patient relationships: perspectives of an ethnically diverse sample of low-income primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41:859–870. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]