Abstract

Children with specific language impairment (SLI) show a protracted period of inconsistent use of tense/agreement morphemes. The purpose of this investigation was to determine whether this inconsistent use could be attributed to the children’s misinterpretations of particular syntactic structures in the input. In Study 1, preschool-aged children with SLI and typically developing peers heard sentences containing novel verbs preceded by auxiliary was or sentences in which the novel verb formed part of a nonfinite subject-verb sequence within a larger syntactic structure (e.g., We saw the dog relling). The children were then tested on their use of the novel verbs in contexts that obligated use of auxiliary is. The children with SLI were less accurate than their peers and more likely to produce the novel verb without is if the verb had been heard in a nonfinite subject-verb sequence. In Study 2, children with SLI and typically developing peers were tested on their comprehension of sentences such as The cow sees the horse eating. The children with SLI were less accurate than their peers and were disproportionately influenced by the nonfinite subject-verb clause at the end of the sentence. We interpret these findings within the framework of construction learning.

Keywords: specific language impairment, constructions, input, extended optional infinitive

1. Introduction

One of the hallmarks of specific language impairment (SLI) in English is a weakness in the use of tense and agreement morphemes. Tense and agreement morphemes (hereafter tense/agreement morphemes) include auxiliary and copula be forms (e.g., is, are, was), third person singular –s, and past tense forms. Preschool-aged children with SLI often use these morphemes only inconsistently. For example, at five years of age, when typically developing children use these morphemes in at least 90 percent of obligatory contexts, children with SLI use them in fewer than 50 percent of obligatory contexts (e.g., Leonard et al. 1992; Leonard et al. 1997; Rice et al. 1995). When these morphemes are produced by children with SLI, they usually appear in appropriate contexts. Substitutions of one tense/agreement morpheme for another (e.g., They is going) or the appearance of a tense/agreement morpheme in a context that requires no overt morpheme (e.g., They likes it) are relatively infrequent. Instead, errors usually represent a failure to use a tense/agreement morpheme where one is required. In some instances, a child may use the appropriate tense/agreement inflection with a verb and then fail to use this same inflection with the same verb moments later within the same speech sample (Miller and Leonard 1998). At a young age, typically developing children, too, show this pattern of inconsistency. However, children with SLI remain in this inconsistent period for a protracted period, often into the early elementary school years (Rice et al. 1998).

There is no question about the importance of examining protracted, inconsistent use of tense/agreement morphology by children with SLI. This pattern of use can serve as a clinical marker for certain types of language impairment by the time children reach five years of age. Indeed, at this age, children can be classified as language-impaired with high levels of sensitivity and specificity on the basis of this type of inconsistent use (Bedore and Leonard 1998; Rice 2003). In fact, Rice and Wexler (2001) have developed a standardized test of tense/agreement morphology that exhibits these positive attributes. It can also be noted that protracted periods of inconsistency with tense/agreement morphology appear to be part of a heritable type of language impairment, genetically distinct from (though sometimes co-occurring with) problems associated with phonological short-term memory (Bishop et al. 2006).

Rice, Wexler, and their colleagues provide a compelling characterization of protracted, inconsistent tense/agreement morpheme use (e.g., Rice 2003; Rice and Wexler 1996, 2001; Rice et al. 1998). According to these scholars, children go through a period during which they fail to grasp that tense/agreement use is obligatory in main clauses. Apart from this optional treatment of tense/agreement, the children have no special problems with this aspect of grammar. This can be seen, for example, in children’s tendency to select the appropriate tense/agreement morpheme when a morpheme is, in fact, produced (e.g., Mommy is eating rather than Mommy am/are eating). In addition, these children are likely to reject sentences with agreement errors (substitutions) on grammaticality judgment tasks. Rice, Wexler, and their colleagues argue that when children fail to use tense/agreement, they instead produce a form that can be regarded as a nonfinite form. Thus, a production such as Mommy eating is not a failed attempt to include auxiliary is in the utterance but rather the selection of an utterance containing a nonfinite verb, eating, with no underlying projection of tense/agreement. It is assumed that children’s treatment of tense/agreement as obligatory in main clauses hinges on the emergence of a biologically based linguistic principle. In typical development, this principle is acquired relatively early; in children with SLI, in contrast, the principle is very slow to appear, resulting in a prolonged period of inconsistent tense/agreement morpheme use.

We endorse the idea that tense/agreement morpheme use is inconsistent for a protracted period in the speech of children with SLI, and agree that most productions that lack such morphemes might well be selections of nonfinite forms by the children. However, in this paper, we explore the feasibility of an alternative source of the children’s apparent confusion about the obligatory nature of tense/agreement. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that the origins of children’s inconsistent use of tense/agreement morphology can be found in the details of the children’s language input.

The rationale behind this view is as follows. Like Tomasello (2003) and others, we can find grammatical structures in the input provided to children that bear a close resemblance to the kinds of nonfinite utterances that the children produce. Child utterances such as Mommy running and Daddy play basketball resemble nonfinite adult clauses as in We saw [Mommy running] and Let’s watch [Daddy play basketball], respectively. They also resemble the nonfinite subject-verb sequence that follows a sentence-initial auxiliary in a question, as in Is [Mommy running]? and Did [Daddy play basketball]? Using computer modeling, Freudenthal and colleagues (2006, 2007) demonstrated that utterances in the input of this type could, in principle, lead to the production of utterances that lack tense/agreement morphemes. These investigators built an utterance-final bias into the model, and, to simulate development, relaxed this bias gradually. During the initial phase, the only utterances with tense/agreement morphemes properly handled by the model were those based on short simple sentences in the input; longer utterances in the input had the effect of promoting nonfinite utterances in the model’s output. When the utterance-final bias was relaxed, the proportion of output utterances containing tense/agreement morphemes increased.

Theakston and colleagues (2003) tested young children directly to examine whether input could influence children’s tendency to use utterances with or without tense/agreement morphemes. These investigators found that typically developing two-year-olds were more likely to use third person singular –s in obligatory contexts with novel verbs that were previously presented to them in inflected form (e.g., Look, [it tams]), than with novel verbs that were previously presented to them in a sequence in which the tense/agreement morpheme was displaced from the novel verb, leaving a nonfinite subject-verb sequence (e.g., Will [it mib]?). Theakston and Lieven (2008) reported similar findings for auxiliary be use, employing a slightly different method.

Findings of this type suggest that young typically developing children may not comprehend the structural ties within the adult utterance and, as a result, may inappropriately extract a nonfinite subject-verb sequence toward the end of the adult sentence and use it as a stand-alone utterance. These findings also suggest that, initially, children’s use of or failure to use tense/agreement morphemes is influenced by the contexts in which they hear particular verbs. Thus, in the Theakston and colleagues (2003) study, tams was more likely to be used than tam in third person singular –s contexts whereas mib was more likely to be used than mibs in such contexts, in accordance with how these verbs were introduced to the children. If the distribution in the input had been different – for example with the same child hearing both Look [it mibs] and Will [it mib]? – the same verb (mib) would be expected to be used both with and without third person singular –s in the child’s speech.

Given that by five years of age, typically developing children are markedly superior to children with SLI in their use of tense/agreement morphemes, it might be easy to assume that these children pass very quickly out of the period of inconsistent use and recognize that nonfinite subject-verb sequences such as Mommy running and Daddy play basketball (and it mib) are not used in isolation. However, recent studies suggest that the progression toward consistent use is more gradual. For example, many young typically developing children first use auxiliary is in contracted form with subject pronouns (as in he’s) and only later show use of is with subject nouns (Wilson 2003). There are also developmental differences between similar morphemes. For example, auxiliary is and auxiliary are do not show the same rate of development, especially in questions (Rowland et al. 2005; Theakston and Lieven 2005).

Some of these differences might be attributable to characteristics of the input. For example, the token frequency of subject pronouns is much higher than that of subject nouns and thus children’s use of auxiliary is with subject pronouns may reflect the learning of a construction that is distinct from their other (still emerging) uses of auxiliary is (Theakston et al. 2005).

It also seems to be the case that when young typically developing children begin to develop broader, more abstract constructions, some of these constructions are based on nonfinite subject-verb sequences that were extracted from larger structures in the input (see Kirjavainen et al. 2009). This creative use of nonfinite utterances continues until young children learn the structural ties in the larger structures that render nonfinite sequences inappropriate as stand-alone utterances. In the meantime, young children will produce both new utterances that contain tense/agreement morphemes (based on appropriate exemplars in the input) as well as new utterances that lack these morphemes (based on inappropriate nonfinite subject-verb sequences).

We propose that the extended period of inconsistent tense/agreement use seen in children with SLI can be attributed to the same asymmetry of skills, with an especially protracted period between the point when these children show an ability to generate new (unattested) utterances and the point when they learn to properly interpret the larger structures.

The result will be an extended period during which utterances can be formed that have two different bases, resulting in alternative patterns that have comparable status in the children’s grammars. The difference between young typically developing children and children with SLI will be in the duration of the period during which new, nonfinite utterances are generated because the children have not yet learned to interpret nonfinite sequences within larger syntactic structures.

The following developmental pattern can illustrate our proposal. For typically developing children and children with SLI alike, an utterance such as The dog’s eating might be derived directly from an adult utterance in the input such as, Look, [the dog’s eating]. Soon, the children will acquire the ability to form an item-based construction by employing new nouns with the verb, as in The cat’s eating. Subsequently, new verbs will be incorporated, as in The cat’s running. At some point, these children will acquire the ability to generate novel subject-verb utterances. At that time, children may still be having difficulty relating nonfinite subject-verb sequences in the input to the larger structures of which they are a part. Because of this, these children might also generate novel subject-verb utterances based on inappropriate extractions from the input, such as The frog jumping derived from an utterance such as I see [the frog jumping]. This utterance might expand to an item-based construction with utterances such as The cat jumping followed, in turn, by the child’s use of The cat running. Thus, two very similar utterances, The cat’s running and The cat running, could co-exist in the children’s speech, each based on a different abstract construction that has its origins in the input. If, as we propose, children with SLI are especially slow to learn the structural ties that restrict nonfinite subject-verb sequences to larger structures only, these children will continue to generate new utterances based on nonfinite constructions for an extended period.

It also appears likely that lexical verbs initially associated with either a sequence containing a tense/agreement morpheme or a sequence containing a nonfinite subject-verb sequence will be more likely to be used in the same manner by the child for some time. The basis for this prediction follows from findings that suggest that language learners seem to simultaneously acquire generalizations at more abstract levels and at lower levels reflecting lexically-based generalizations (Goldberg 2006). As applied to the above example, generalizations from, say, The dog’s eating to The cat’s eating may reflect a relatively narrow lexically-based extension whereas generalization to The dog was eating may represent a more abstract extension, involving tense. An utterance such as The cat was eating might well involve generalizations at both a lexically-based (dog → cat) and more abstract (present tense → past tense) level.

In the present investigation, we conducted two studies designed to explore the feasibility of these assumptions about the inconsistent use of tense/agreement morphemes by children with SLI. In the first study, we test the hypothesis that nonfinite subject-verb sequences in the input will influence children’s tendency to use nonfinite utterances at the same time that the children show evidence of using constructions that reflect generalizations beyond the immediate input. We test this hypothesis in an especially stringent way. Specifically, we ask whether novel verbs presented with one tense/agreement morpheme (e.g., auxiliary was in Just now the cat was channing) can be used by the children with another tense/agreement morpheme (e.g., auxiliary is in Scooby is channing), while novel verbs presented within nonfinite subject-verb sequences (e.g., We saw [the dog relling]) are used by the children in never-before-heard nonfinite utterances (e.g., Big Bird relling). If these expectations are confirmed, the evidence would suggest that children with SLI simultaneously use tense/agreement constructions and nonfinite constructions that are: (1) influenced by the input; (2) relatively abstract by being extended to new lexical items and auxiliary forms; and (3) in the case of nonfinite utterances, derived at least in part by the inappropriate extraction of nonfinite subject-verb sequences from larger structures in the input. A group of typically developing same-age peers also participated in this first study, to demonstrate that when children already use auxiliary forms at near-mastery levels, novel verbs presented in nonfinite subject-verb sequences do not compel them to produce similar sequences in contexts that require an auxiliary in the adult grammar.

In the second study, we test the hypothesis that children with SLI who show inconsistent use of tense/agreement morphemes continue to have difficulty interpreting syntactic structures that contain nonfinite subject-verb sequences that could serve as the source for the children’s nonfinite utterances. The children participated in a comprehension task in which they were asked to point to the drawing that corresponded to target sentences such as The cow sees the horse eating. The alternative drawings used in each item allowed us to determine not only whether the children had difficulty with the syntactic structure, but also whether their responses reflected special sensitivity to the nonfinite subordinate clause. A group of typically developing children who used tense/agreement morphemes to a greater degree than the children with SLI served as a comparison group. These children were expected to exhibit greater understanding of the target sentences.

Together, these two studies were designed to test the view that SLI may be profitably studied within the framework of construction learning. In these studies, we test the idea that instead of reflecting a deficit in tense/agreement morpheme use in particular, these children’s difficulty may be a consequence of the children’s persistence in generating new utterances based on constructions in the input that do not constitute full sentences in the adult grammar.

This proposal has implications for how the path toward consistent use of tense/agreement morphemes might be characterized for both typically developing children and children with SLI. For both groups of children, development might involve not only learning to apply tense/agreement morphemes more consistently in obligatory contexts (the usual characterization of development) but also learning to discard particular constructions as candidates for stand-alone utterances. The latter process will proceed more slowly in children with SLI, but is assumed to occur as well in typical development.

2. Study 1

Method

Participants

Twenty-eight children served as participants in Study 1. Eighteen children with SLI who exhibited inconsistency in the use of tense/agreement morphemes constituted the SLI group. These children, 11 males and seven females, ranged in age from 4;2 (years; months) to 5;9. All of the children scored below the 10th percentile on the Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test – II (SPELT-II; Werner and Kresheck 1983) and were enrolled in language intervention. All children passed a hearing screening and a screening for oral structure and function, showed no behavioral symptoms suggestive of autism and were not under medication for the prevention of seizures. All of the children scored at least 85 on the Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (CMMS; Burgemeister et al. 1972) (M = 112.29, SD = 12.90). Based on a spontaneous speech sample, the children’s finite verb morphology composite score ranged from 16 to 83 percent. This measure, based on the work of Leonard and colleagues (1999), represents the total number of the child’s productions of third person singular –s, past tense – ed, and copula and auxiliary be forms combined divided by the total number of obligatory contexts for these morphemes combined, multiplied by 100. Auxiliary is constituted one of the tense/agreement morphemes that all children produced inconsistently. At the age level studied here, typically developing children show a mean composite score of 95 percent with 1 SD = 5 percent (Leonard et al. 1999).

Although low scores on the SPELT-II and inconsistent use of tense/agreement morphology served as the language criteria for the selection of participants, we also administered to the children the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – III (PPVT-III; Dunn and Dunn 1997) and the receptive scale of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – Preschool 2 (CELF-P2; Wiig et al. 2004) to obtain descriptive clinical information. As a group, the children earned scores in the average range on both receptive measures. Mean standard scores for the PPVT-III and CELF-P2 receptive composite were 103.86 (SD = 12.84) and 97.43 (SD = 11.28), respectively. One child scored 84 on the PPVT-IIII, but scored 101 on the CELF-P2 receptive composite, and two children scored 81 on the CELF-P2 receptive composite but scored 97 and 101 on the PPVT-III. All other scores were higher, with the remaining PPVT-III scores ranging from 87 to 123 and the remaining CELF-P2 receptive composite scores ranging from 89 to 123.

A group of 10 children who exhibited age-appropriate language ability also participated in Study 1. These typically developing children were comparable in age to the children with SLI and are hereafter referred to as the TD-A group. These children (2 males, 8 females) ranged in age from 4;0 to 5;10. All scored above the 17th percentile on the SPELT-II and passed a hearing screening, a screening for oral structure and function, and scored above 85 on the CMMS (M = 118.10; SD = 9.27). The finite verb morphology of each child in the TD-A group was above 90 percent.

Procedure

Ten novel verbs were created, using 10 of the consonant-vowel-consonant non-words of high phonotactic frequency employed by Jusczyk and colleagues (1994). These non-words were:*** /rIn/, /pεs/, /bæl/, /gIs/, /pæg/, /t∫æn/, /dεs/, /kæk/, /rεl/, and /bIs/. Each child heard all 10 novel verbs, presented in 10 separate sessions held on different days. All of the novel verbs referred to unusual actions that toy characters were made to perform (e.g., toy animals rubbing their ears with their tails). Five of the novel verbs were presented in nonfinite form within larger structures (e.g., We saw the dog pagging), and the remaining five novel verbs were presented in sentences with auxiliary was (e.g., Just now the horse was channing). Each novel verb appeared in only one of these forms for any given child, but appeared in nonfinite form for half of the children and with auxiliary was for the remaining children. The 10 different novel verbs were presented in three different orders. The orders were random except for the requirement that the presentation condition (nonfinite or auxiliary was) alternated from one session to the next. This requirement ensured that any given novel verb was presented in a condition that differed from that of the novel verb presented in the previous session and that of the novel verb to be presented in the next session.

Each novel verb was presented within an activity that involved a practice item with a familiar verb, five presentation items involving the novel verb, and three presentation items involving familiar verbs that were inserted after the first, third, and fourth presentation item involving the novel verb. For the practice item and all presentation items, the experimenter made a toy character perform an action for several seconds. Then, after the action ceased, the experimenter described the action and asked the child to repeat the sentence. For novel verbs presented in the nonfinite condition, the sentence and prompt were (using pag as the example): We saw the dog pagging. You say it. We saw…. Although the children could have responded by completing the experimenter’s prompt, children typically repeated the entire presentation sentence (saying, in this case, We saw the dog pagging). For novel verbs presented in the auxiliary was condition, the sentence and prompt were (using chan as the example): Just now the horse was channing. You say it. Just now… Again, the children’s responses were repetitions of the entire presentation sentence (e.g., Just now the horse was channing). The familiar verbs used in the same session were presented in the same condition (nonfinite or auxiliary was) as the novel verb. The character made to perform the action was different for each item. Thus, for the novel verb pag, the five items employing this novel verb had, as subjects performing the action, a toy dog, toy duck, toy horse, toy bird, and toy alligator. The practice items using a familiar verb had a Buzz Lightyear figure as the subject, and the three items with familiar verbs that were interspersed among the items using pag employed a toy bear, a toy girl, and a Minnie Mouse figure as subjects.

Immediately following the presentation items, two probe items were presented, each designed to assess the child’s use of the just-presented novel verb in a sentence that obligated auxiliary is. The first probe item involved one of the same subjects that had been paired with the novel verb during the presentation items (e.g., the toy dog with pag). The second probe item made use of a subject that had not been paired with the novel verb but instead had been paired with one of the familiar verbs during the presentation items (e.g., Minnie Mouse with pag). For both probe items, the experimenter made the character perform the novel action and, while the action was ongoing, the child was asked “Tell me about the show, what’s happening here?” It can be noted that the auxiliary is appeared in the experimenter’s request for the child to describe the ongoing action. Although the appearance of is may have increased the children’s tendency to select a sentence frame that included this morpheme in their response, the same request was issued for both novel verbs that had been presented in nonfinite form as well as novel verbs that had been presented with auxiliary was. Thus, any influence of the request containing is would have narrowed the effect between the two presentation conditions, making a difference between the two conditions less likely.

Scoring

The children’s responses to the probe items were transcribed and scored. Scorable items had to include the novel verb that was targeted in the probe item. Allowances were made for less mature pronunciations of the novel verb, provided that the child’s pronunciation did not correspond to a real verb. If a child produced a real verb (e.g., scratching to refer to a toy animal rubbing its ear with its tail), or produced a novel verb used on a previous day, the item was regarded as unscorable. Other unscorable items were instances in which the child seemed to forget the novel verb and responded with “I don’t know” or “I don’t remember”.

Scorable items were coded for several details. First, we noted whether the children produced auxiliary is with the novel verb. We also made note of whether the subject was produced in noun form or if, instead, a pronoun was used. The latter is important, because frequently occurring forms such as he’s could easily signal the child’s use of a different, competing construction (e.g., He’s ___ing; Tomasello 2003). Thus, a production such as He’s channing might not reflect the same degree of influence from the preceding presentations as a production such as Scooby’s channing. Finally, we noted whether the child’s response to the probe item included auxiliary was (instead of auxiliary is). Such a response would certainly point to an influence of the presentation items. However, at best, it would reflect only a narrow (mis)application of a construction. For example, if the child said Scooby was channing (instead of Scooby is channing) and the Scooby figure was never paired with chan during the presentation items, the child’s response could have reflected an item-based construction extended to a new subject noun only, with a failure to extend to a new auxiliary.

For statistical analysis, we included only those children who produced at least three novel verbs from each condition in obligatory contexts for auxiliary is on the probes. The responses of those children not meeting this criterion were examined descriptively.

Reliability

To assess reliability in transcribing the children’s responses to the probes, audiorecordings of four children were selected at random and transcribed by an independent judge. Agreement was determined on an item-by-item basis. Agreement was considered to have occurred when the original transcription and second transcription showed the same auxiliary form (is or was) being used by the child for the item, or both showed the child’s failure to use an auxiliary for the item. The mean percentage of agreement across the four children was 96.25. No child’s transcriptions showed an agreement lower than 95 percent.

Results

TD-A Group

All children in the TD-A group met our criterion for number of novel verbs produced in each condition. The mean number of scorable responses for the nonfinite and tense/agreement conditions were 9.8 (SD = 0.42) and 9.4 (SD = 0.84), respectively. As expected, the children in the TD-A group performed at ceiling levels and were therefore not influenced by the condition in which the novel verbs were presented. Their mean percentages of use of auxiliary is in the nonfinite condition and in the tense/agreement condition were 99.00 (SD = 3.16) and 98.00 (SD = 6.32), respectively. Only one response from one child took the form of a subject and novel verb without an auxiliary (The turtle baling); this novel verb had been presented in the nonfinite condition but the subject (turtle) had never been heard with the novel verb. Two other errors, from a single child, were productions containing auxiliary was for items assessing a novel verb that had been presented in the tense/agreement condition. (Recall that novel verbs in the tense/agreement condition had been presented with auxiliary was.) One of these items involved a subject previously associated with the novel verb and the other involved a subject not previously heard with the novel verb. As can be seen from these values, the TD-A children’s use of auxiliary is was extensive regardless of whether the subject noun had ever been heard with the novel verb.

Six of the TD-A children responded to probe items with utterances containing he’s. Given that he’s might have had its origins in an item-based construction (such as He’s ___ing) quite separate from those examined in the present study, we re-examined the children’s use of auxiliary is on the probes after excluding all responses with he’s. One of the 10 TD-A children had to be excluded because all of her responses took the form of He’s ____ing. The remaining nine children in this group produced three or more novel verbs with a subject noun in both the nonfinite and tense/agreement conditions. Their mean percentages of auxiliary is use after excluding the items with he’s were 98.89 (SD = 3.33) and 97.78 (SD = 6.67), respectively. Again, accuracy was very high regardless of whether the subject noun had ever been heard with the novel verb. Because the TD-A children performed at ceiling levels in their use of auxiliary is across presentation conditions, their data were not included in the statistical analysis.1

SLI Group

Of the 18 participants with SLI, four children failed to meet the criterion of producing at least three novel verbs from each condition in obligatory contexts for auxiliary is. Of the four children who did not meet our criterion, three children produced only nonfinite responses to probe items that followed novel verbs in the nonfinite condition, and used auxiliary was during testing with either one or two novel verbs that had been presented in the tense/agreement condition. The fourth child produced two examples of auxiliary is with novel verbs that had been presented in the tense/agreement condition but did not attempt any novel verbs that had been presented in the nonfinite condition.

For the 14 children with SLI who met our criterion for minimal use of the novel verbs on the probes, the mean number of scorable responses on items assessing the novel verbs presented in the nonfinite condition was 6.79 (SD = 2.29). The corresponding mean for the items assessing novel verbs presented in the tense/agreement condition was 6.93 (SD = 2.37). Thus, the number of scorable items for the two conditions can be viewed as comparable. Our statistical analyses were designed to address the experimental questions of interest. The first question examined was whether the children’s tendency to use the novel verbs as nonfinite or with auxiliary is varied as a function of the condition in which the novel verbs were presented. The first analysis combined the child’s responses to all probe items in the nonfinite presentation condition and compared these data to the child’s combined responses to all probes items for novel verbs that had been presented in the tense/agreement condition. For each condition, a percentage of auxiliary is use was computed for each child; the percentages were then arc-sine transformed and the two conditions were then compared using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The two conditions were clearly different, F (1, 13) = 8.53, p = 0.012, η2 = 0.396. The mean percentages of use of auxiliary is on the probes for novel verbs presented in the nonfinite condition and for those presented in the tense/agreement condition were 60.00 (SD = 38.11) and 83.71 (SD = 28.18), respectively.

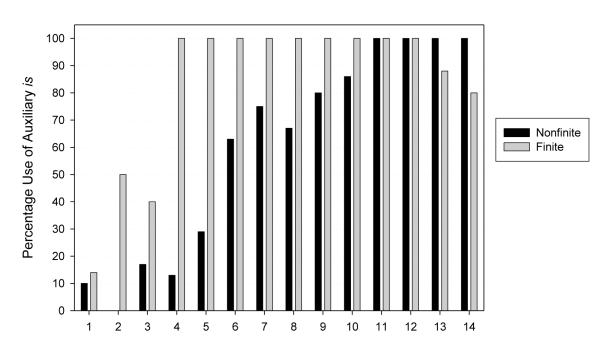

The large SDs reflect the differences among the children in degree of auxiliary is use within each condition. These large SDs do not reflect the strong tendency for the children – regardless of their overall success with auxiliary is – to use auxiliary is less frequently with novel verbs that had been presented in the nonfinite condition than with novel verbs that had been presented in the tense/agreement condition. This strong tendency is apparent in Figure 1. Ten children showed greater use of auxiliary is for novel verbs that were presented in the tense/agreement condition than for novel verbs that were presented in the nonfinite condition, with an average difference favoring the former of 36.40 percent. Two children showed the reverse pattern, with an average difference favoring the nonfinite condition of only 16.00 percent. The remaining two children showed 100 percent use of auxiliary is for both types of novel verbs.

Figure 1.

The percentage of use of auxiliary is on the probes by each of the 14 children with specific language impairment for novel verbs that had been presented to them in nonfinite subject-verb sequences within larger structures (Nonfinite) and for novel verbs that had been presented to them in sentences containing auxiliary was (Finite).

Some of the children responded to probe items with utterances containing he’s. (All responses with he were accompanied by the contracted form of auxiliary is). Because he’s might have had its origins in an item-based construction that differed from those examined in the present study, we also conducted an ANOVA that treated as unscorable all responses that contained he’s. The number of children in this analysis was reduced from 14 to 13 because, for one child, all of the probe response productions of novel verbs from the nonfinite condition contained he’s. Several other children showed some degree of use of he’s in their probe responses. One child produced novel verbs from the nonfinite condition as either nonfinite or with auxiliary is but all examples of the latter were productions of he’s. Two additional children produced novel verbs from the nonfinite condition with a mixture of productions of he’s, productions of a subject noun with is, and productions in nonfinite form. For novel verbs presented in the tense/agreement condition, a few (from the same children) were productions of he’s; however, each of these children also produced auxiliary is with noun subjects. The ANOVA for these data revealed a significant difference between conditions, F (1, 12) = 9.34, p = 0.010, η2 = 0.438. Mean percentages of auxiliary is use for the novel verbs presented in the nonfinite condition and those presented in the tense/agreement condition were, respectively, 51.15 (SD = 40.30) and 82.46 (SD = 28.93). Ten children’s percentages were lower for the nonfinite condition than for the tense/agreement condition, and two children showed percentages in the reverse direction. The remaining child showed 100 percent use of auxiliary is with all novel verbs.

Whereas the first experimental question dealt with the influence of input on the children’s use of the novel verbs, the second question pertained to whether the children’s use showed evidence of constructions of a more abstract nature. To a great extent, this question was answered in the affirmative in the preceding analyses, because children often used auxiliary is with novel verbs on the probes even though the only auxiliary that was employed during the presentation period (in the tense/agreement condition) was auxiliary was. We explored this issue further by determining whether the children’s use of auxiliary is was more likely if the subject required in the item had been paired with the novel verb during the presentation period. The children’s degree of auxiliary is use proved to be highly similar regardless of the type of subject required. For novel verbs presented in the tense/agreement condition, the mean percentage of auxiliary is use on items involving a previously paired subject was 81.64 (SD = 27.90), whereas the mean percentage for items involving a different subject was 84.79 (SD = 33.11). Two children showed higher percentages of auxiliary is use when a previously paired subject was required; three other children showed the reverse pattern, and the remaining nine children used auxiliary is to the same degree with the two types of subjects.

For novel verbs presented in the nonfinite condition, very similar results were observed. The mean percentage of auxiliary is use on items involving a previously paired subject was 64.29 (SD = 38.75); the corresponding percentage on items involving a different subject (never before paired with the novel verb) was 55.71 (SD = 43.14). Five children showed higher percentages of auxiliary is use when a previously paired subject was required, three showed the reverse pattern, and six children used auxiliary is to the same degree with the two types of subjects.

Of course, evidence for the use of constructions does not depend on the children’s inclusion of auxiliary is in their responses. Even responses of a nonfinite form that incorporated a subject never before presented with the novel verb would represent the children generalizing from the input. Accordingly, we compared the number of scorable responses that contained a subject that had been paired with the novel verb in the presentation condition with the number of scorable responses that contained a different subject, one that had never been paired with the novel verb. For this comparison, the children’s inclusion or failure to include auxiliary is in their response was not considered. The mean number of scorable responses for items requiring a previously paired subject was 6.79 (SD = 2.29); the corresponding mean for items requiring a different subject was 6.93 (SD = 2.37). These figures suggest that even though the children were significantly influenced by whether a novel verb was presented in a nonfinite sequence or with a tense/agreement morpheme, they were nevertheless capable of using the novel verb with sentence subjects that had not been previously associated with it.

In a final analysis, we asked whether the degree to which the children were influenced by the nonfinite presentations of the novel verbs was related to the degree to which they manifested the classic symptoms of SLI. For the latter, we examined the children’s finite verb morphology composite scores described earlier. This score is based on the children’s use in spontaneous speech of third person singular –s, past tense –ed, and copula and auxiliary be forms combined. This measure serves as a clinical marker of SLI (Bedore and Leonard 1998; Rice 2003). Furthermore, for each of these morphemes, a corresponding nonfinite subject-verb sequence can be found in adult speech that could, in principle, serve as the source for children’s inconsistent use (e.g., We watch Mommy play tennis every day/ Mommy plays tennis everyday; We saw Daddy climb up a tree yesterday/ Daddy climbed up a tree yesterday). Correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between the children’s tendency to use auxiliary is with novel verbs that had been presented in the nonfinite condition and their finite verb morphology composite scores, r = 0.81, p = 0.001.

3. Study 2

The results of Study 1 suggested that TD children who consistently use auxiliary is in their speech are not influenced by how novel verbs are presented, whereas children with SLI who are inconsistent in their use of auxiliary is are still significantly influenced by the nature of the input. When novel verbs are heard in nonfinite subject-verb sequences within larger structures, they are more likely to produce these novel verbs without an auxiliary. Likewise, when novel verbs are heard with auxiliary forms, they are more likely to include auxiliary forms when they produce the novel verbs. In Study 2, we provide data that support our assumption of input effects by presenting the children with a comprehension task that assesses their ability to comprehend the types of structures used as input in the nonfinite condition of Study 1.

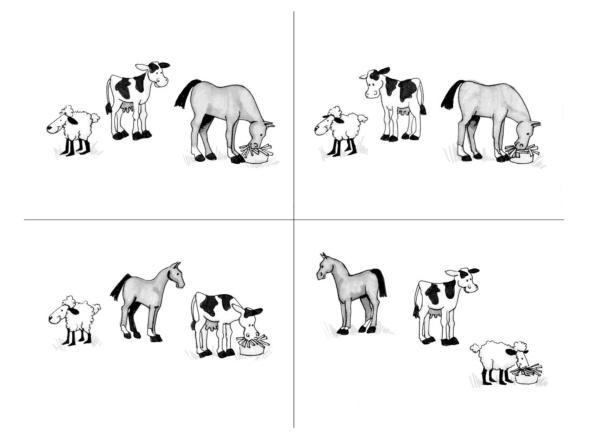

The sentences used in Study 2 take the form seen in The cow sees the horse eating. Upon hearing the target sentence, the children are required to select from an array of four drawings the one that corresponds to the sentence. An example appears in Figure 2. We expect children with SLI who are inconsistent in their use of auxiliary is to score more poorly on this task than a group of children who exhibit significantly greater use of auxiliary is. Crucially, the foils permit us to interpret the nature of children’s difficulty when errors are committed. One of the foils shares with the target the same information that is reflected in the nonfinite subject-verb sequence, but this foil differs from the target in the information that appears in the matrix clause of the target. For example, for the target sentence The cow sees the horse eating, the correct drawing depicts a cow looking at a horse eating while a sheep is standing on the other side of the cow looking in another direction. The crucial foil (referred to as the ‘principal foil’) depicts a horse eating, but the cow and sheep are both looking away from the horse. (The two remaining foils depict the same three characters with either the cow eating or the sheep eating.) If children who have difficulty with this type of syntactic structure attend principally to the sentence-final nonfinite subject-verb clause, they would be more likely to select the principal foil than the other two foils.

Figure 2.

The array of drawings used for the item The cow sees the horse eating. The target picture appears in the upper left whereas the ‘principal foil’ – that also depicts a horse eating – is in the upper right.

Method

Participants

Six of the children with SLI who participated in Study 1 were available to participate in Study 2. They ranged in age from 4;3 to 5;7. At the time of Study 2, these children’s use of auxiliary is averaged 29.5 percent (SD = 32.38) in obligatory contexts in a spontaneous speech sample. In Study 1, these children showed the dominant pattern of greater use of auxiliary is on probes of novel verbs presented in the tense/agreement condition than on probes of novel verbs presented in the nonfinite condition. The children were also administered the Sentence Structure subtest of the CELF-P2. The children’s raw scores on this test were used as the basis for matching these children with a group of typically developing children.

The six typically developing children with whom the children with SLI were matched were younger, ranging in age from 3;3 to 4;0. These children scored above the 17th percentile on the Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test – Preschool (SPELT-P; Werner and Kresheck 1983) and passed a hearing screening and a screening of oral structure and function. The children’s use of auxiliary is in obligatory contexts in spontaneous speech averaged 81 percent (SD = 22.32), which was significantly higher than the use of auxiliary is by the children with SLI, t (10) = 3.207, p = 0.009, effect size d = 1.88). Each of these children’s CELF-P2 Sentence Structure subtest raw scores was matched to a corresponding raw score of a child with SLI to within +/- 1 point. This subtest assesses children’s understanding of syntax, but does not include the particular syntactic structure serving as the focus of Study 1 and Study 2. Nevertheless, by matching the two groups on raw scores on this subtest, we are creating a very stringent test of our prediction. That is, any group difference in the children’s comprehension of the structure of interest must be quite robust to be observable even after the groups have been equated on a more general syntactic comprehension measure.

Procedure

The comprehension task consisted of 30 items. Ten items constituted the items of major interest. Each of these items had the structure seen in the example The cow sees the horse eating, in which the nonfinite subordinate clause was made up of a nonfinite subject-verb sequence. The remaining items served to ensure that the children comprehended the structure of the simple clauses that served as components of the larger structure of interest. Ten of these control items were simple activities in the present progressive (e.g., The horse is eating), and the remaining 10 involved perception verbs in a simple subject-verb-object structure (e.g., The cow sees the horse).

For each of the 30 items, four colored drawings were shown on a computer screen and the child was asked to point to the picture that matched the sentence. For the items with nonfinite subordinate clauses, the same three characters appeared in each of the four drawings. The target picture conveyed the event noted in the target sentence (e.g., a cow looking at a horse eating) while a third character uninvolved in the described event (e.g., a sheep looking in a different direction) also appeared the drawing. One of the three drawings constituting a foil in the nonfinite subordinate clause items depicted the same nonfinite subject-verb sequence as appeared in the target sentence (e.g., a horse eating). However, the other characters did not reflect the events of the matrix clause (e.g., the cow and the sheep were looking away from the horse). The remaining foils also depicted similar events, but these did not correspond to the nonfinite subject-verb sequence used in the target sentence (e.g., a cow looking at a sheep eating while a horse looks in the opposite direction; a horse looking at a cow eating while a sheep looks in the opposite direction). For the simple progressive control items (e.g., The horse is eating), foils included the same subject performing a different action (e.g., a horse running), a different subject performing the named action (e.g., a sheep eating), and a different subject performing a different action (e.g., a sheep running). For the simple subject- perception verb-object control items (e.g., The cow sees the horse), one foil depicted the reverse relationship (e.g., the horse looking at the cow), another showed the same characters clearly not involved in the named activity (e.g., the cow and the horse looking away from each other), and the remaining foil showed the correct subject but a different object (e.g., a cow looking at a sheep). For all 30 items, the locations of the target drawing and foils on the computer screen were systematically varied across items.

Results

All of the children in each group scored 100 percent on the simple progressive control items. The mean percentages of use of the children with SLI and younger children with TD on the simple subject–perception verb–object control items were 87.5 and 84.67, respectively. All children performed well above chance levels on the control items. The value of the control items was to demonstrate that any difficulty with the major items of interest – those with nonfinite subordinate clauses – was not due to a lack of understanding of the simple structures that form the larger structure.

On the subordinate clause items of primary interest, the younger children with TD showed a significantly higher percentage correct (M = 87; SD = 8.99) than the children with SLI (M = 69; SD = 15.91), t (10) = 2.313, p = 0.037, effect size d = 1.45). Note that although chance on the task is 25 percent if a child were to choose randomly from among the four drawings in the array, only two of the drawings portray the particular relationship described in the subordinate clause of the target sentence. Therefore, if a child failed to understand the larger syntactic structure and responded on the basis of the nonfinite subject-verb sequence in the subordinate clause, chance performance would be 50 percent.

Along with expecting lower percentages of accurate responses by the children with SLI than by the younger TD group, we also predicted that the most frequent selection of an incorrect drawing would be the drawing that depicted the relationship matching the relationship represented in the subordinate clause of the target sentence. For example, for the target sentence The cow sees the horse eating, the most frequent error would be the selection of the drawing depicting the horse eating but with the cow and sheep looking away from the horse. In fact, this proved to be the case. With three foils for each item, an incorrect response had a 33 percent chance of being the principal foil. However, for the children with SLI, 69 percent of the errors were selections of the principal foil, a pattern that deviated significantly from chance, t (6) = 16.96, p < 0.001). In contrast, children in the TD group, at 39 percent, did not tend to select the principal foil at levels greater than chance when they made an incorrect choice, t (5) = 0.448, p = 0.677. (Only five of the six TD children’s data could be included, as one child with TD scored 100 percent correct on the subordinate clause task.) These children did not seem to be drawn primarily to the sentence-final subordinate clause, an observation in keeping with their greater understanding of the larger syntactic structure as reflected in their higher accuracy.

4. Discussion

The goal of this investigation was to determine whether children with SLI use both nonfinite utterances and utterances with tense/agreement morphemes that at once reflect the influence of input, the development of constructions that reflect generalizations beyond the input, and (at least for nonfinite utterances) possible misinterpretation of particular structures in the input. In Study 1, the influence of the input was seen in the SLI group’s tendency to use a novel verb in the form in which it was heard (with or without an accompanying auxiliary). The evidence of construction use was also seen in Study 1, because the children with SLI used both nonfinite utterances and tense/agreement utterances with subjects that had not been heard with the novel verb in the input, and utterances with auxiliary is when auxiliary was constituted the only auxiliary form used with the novel verb in the input. Evidence of possible misinterpretation of particular structures in the input was seen when the children with SLI in Study 1 were more likely to produce nonfinite utterances with novel verbs that were heard in nonfinite subject-verb sequences that were part of larger (fully grammatical) structures in the input. Additional evidence of misinterpretation was obtained in Study 2; children with SLI who were inconsistent in their use of auxiliary is had difficulty interpreting sentences such as The cow sees the horse eating. Their errors most often revealed special attention to the nonfinite subject-verb sequence appearing at the end of the target sentence. All of these pieces of evidence were largely absent from the data obtained from the typically developing children who participated in the two studies. These children were relatively proficient in their use of tense/agreement morphemes, leading us to suspect that nonfinite subject-verb sequences in larger structures were no longer influencing their grammar. The findings of Study 2 were compatible with this view, as these children were relatively accurate in their interpretation and were not disproportionately drawn to the sentence-final nonfinite subordinate clause.

Before discussing the implications of these findings, we consider an alternative interpretation of the data. Perhaps the novel verb-specific effects observed in Study 1 were illusory, reflecting instead only transient activation through syntactic priming. Suppose that children with SLI already had available two alternative ways of producing utterances that were compatible with our task, namely, a progressive form that contains an auxiliary be morpheme (as in Mommy is running), and a nonfinite progressive form that lacks an auxiliary (as in Mommy running). The presentation of a novel verb in only one type of pattern might well have served to prime the children – that is, to increase the likelihood that the children would select this pattern for use during the probes for this novel verb because its prior activation made it easier to retrieve. According to this interpretation, our finding did not represent the children’s learning of specific novel verbs in specific syntactic structures, but rather only the temporary activation of particular syntactic structures that were then applied to probe items that only happened to involve novel verbs.

Evidence for a priming effect of this type can be seen in a study of children with SLI by Leonard and colleagues (2002). These investigators employed a syntactic priming paradigm to determine whether prime sentences such as We see the mouse eating the cheese were likely to promote picture descriptions such as The horse kicking the cow (rather than The horse is kissing the cow) in contexts that obligated auxiliary is. This type of prime condition was contrasted with one in which the prime sentences contained auxiliary are, as in The boys are washing the car. The findings were in concert with these predictions; the children with SLI were more likely to supply the auxiliary is in their descriptions of target pictures when preceded by prime sentences such as The boys are washing the car than when the preceding prime sentences were those such as We see the mouse eating the cheese.

Familiar verbs were used in the Leonard and colleagues (2002) study, and the results were viewed as reflecting transient activation. That is, if one assumed that the children with SLI possessed a grammar that allowed either a sentence such as The horse is kicking the cow or one such as The horse kicking the cow, then the prior activation of one of these sentence frames (e.g., Noun Phrase + Verbing + Noun Phrase, without an auxiliary) might make it more likely that the activated frame would be more readily accessible and hence more likely to be selected for the target picture description. In one respect, such a scenario resembles the case of syntactic priming in adults where, for example, the likelihood of a passive structure being produced is increased if passives were used as prime sentences. The difference, of course, is that one of the alternative frames for the children with SLI in the present study is ungrammatical in the adult system.

However, there are two reasons to believe that factors in addition to transient activation may have been responsible for the findings of the present study. First, even in the case of adults, findings of priming effects of considerable duration that persist even with intervening material has led to the view that priming reflects implicit language learning of structure instead of just transient activation (e.g., Bock et al. 2007). Second, recall that in both the Leonard and colleagues (2002) study and in the present investigation, the children with SLI produced nonfinite utterances such as The horse kicking the cow and Big Bird relling after hearing sentences such as We see the mouse eating the cheese and We saw the dog relling, respectively. These input sentences may have been rendered more suitable as primes if the children failed to grasp the structural ties between the matrix clause (We see or We saw) and the nonfinite clause (the mouse eating the cheese or the dog relling). If nonfinite subject-verb sequences can be extracted from their larger structure for transient activation, it seems reasonable to assume that the same (incorrect) extraction process can occur during language learning and thus be the source of these children’s learning of nonfinite patterns.

It can be noted that although the input effect for the children with SLI was quite strong in Study 1, not all children in this group showed the predicted difference between the nonfinite and tense/agreement condition. In part, this seemed due to the fact that some of the children were approaching adult-like levels of auxiliary use at the time of their participation in the study. A central assumption of our proposal is that greater consistency with tense/agreement morpheme use occurs precisely because the children no longer treat nonfinite subject-verb sequences in larger structures as candidates for use as complete utterances in their own speech. There were also a few children who did not meet our criteria for inclusion, due to producing too few of the novel verbs. However, a close inspection of their data revealed that the productions that did occur were compatible with our predictions. Only nonfinite forms were produced for novel verbs that had been presented in the nonfinite condition, and only auxiliary forms were produced with novel verbs that had been presented in the tense/agreement condition. Input effects seemed to be playing a role in these children’s pattern of use, but their limited ability to recall the novel verbs resulted in too few examples to justify inclusion in the statistical analysis.

The present study focused on one type of syntactic structure that could lead to the improper extraction of nonfinite subject-verb sequences and productions such as Mommy running (from We saw [Mommy running]) or Her running (from [We saw her running]). Similar structures might have the same result, such as Let’s watch [Mommy run] and Let’s watch [her run] (see Kirjavainen et al. 2009). Indeed, utterances such as Mommy run and Her run are common in the literature on children with SLI. However, whereas some children with SLI produce accusative case pronouns in subject position, others produce utterances with nominative case pronouns, as in She run. Structures such as Did/Does/Will/Can [she run]? might well prove to be the source of nonfinite utterances with nominative case pronouns. The Theakston and colleagues (2003) study with young typically developing children employed structures of this type (as seen in Will [it mib?]). The same type of improper extraction might also account for the inconsistent use of past tense by children with SLI. For example, input sentences such as We saw [Tim kiss a girl yesterday] and I heard [Gina break the window] as well as Dad kissed Mom yesterday and My sister broke the glass could well lead to alternating use of kiss and kissed, and break and broke in past tense contexts. Future studies of children with SLI should employ these types of structures as input in an effort to determine whether a wider range of nonfinite utterances might be explained by the type of account offered here.

The finding in this study that the children with SLI were attentive to subject-verb propositions that appeared toward the end of an input sentence offers a possible explanation for certain unexpected findings in the SLI literature. For example, in a grammaticality judgment task, Redmond and Rice (2001) found that a group of children with SLI were sensitive to commission errors that occurred within simple sentences. However, these children inexplicably accepted as grammatical sentences such as He made the robot fell into the pool. One possible explanation for this finding is that the children with SLI failed to understand the structural ties in the larger sentence and therefore based their judgment on what otherwise seemed like an appropriate utterance (the robot fell into the pool).

The present findings are also compatible with a surprising outcome of a language treatment study involving children with SLI. Fey and Loeb (2002) examined the effects of auxiliary-fronted yes-no questions (e.g., Is Daddy driving the truck?) on children’s learning of auxiliary forms. However, fewer children showed gains with this method than with a control condition that involved play. Fey and Loeb speculated that this finding could have occurred if the children failed to grasp the structure of the yes-no questions and consequently interpreted the subject-verb-object proposition (e.g., Daddy driving the truck) as the information – and structure – to be learned.

The findings of the present study have implications for interpreting the protracted period of nonfinite use by children with SLI. Specifically, they raise the possibility that an extended period of alternating between nonfinite utterances and utterances with tense/agreement morphemes could be due to the children’s continued failure to interpret larger structures containing nonfinite subject-verb sequences well after they have acquired the ability to use constructions of a relatively abstract nature. These concurrent events would seem to make it more likely that new, previously unheard nonfinite utterances would be generated relatively frequently and be relatively slow to be expunged from the children’s grammar when the children finally reach the point of correctly interpreting the input sentences that house nonfinite subject-verb sequences.

The findings of the present investigation also have implications for the grammatical profiles seen in children with SLI who are acquiring languages such as Swedish and German. Word order errors, as well as productions of overt infinitive forms in place of agreement and/or tense forms are relatively common in these languages (e.g., Hansson et al. 2000; Leonard et al. 2004; Rice et al. 1997; Roberts and Leonard 1997). For example, if Swedish children with SLI fail to use the appropriate present tense inflection –er in dricker “drinks”, they are likely to produce the overt infinitive –a inflection, as in dricka. Thus, Kristina dricka kaffe “Kristina drink coffee” is sometimes seen in contexts requiring Kristina dricker kaffe “Kristina drinks coffee”. Although ungrammatical by itself, the sequence Kristina dricka kaffe does occur within larger structures, as in a question such as Kan [Kristina dricka kaffe]? “Can Kristina drink coffee?” Thus, if Swedish-speaking children with SLI have difficulties interpreting the structural relations in such questions, they might improperly extract a nonfinite subject-verb sequence with an overt infinitive.

In German, an overt infinitive is also used at times instead of tense/agreement forms by children with SLI. However, in this language the nonfinite verb often appears at the end of the sentence. Thus, instead of Kristina trinkt Kaffee “Kristina drinks coffee” a production such as Kristina Kaffee trinken “Kristina coffee drink” is often heard. This is precisely the sequence seen in German questions, as in Kann [Kristina Kaffee trinken]? “Can Kristina coffee drink?” Another type of error by German-speaking children with SLI – and one that has not yet been explained – is the use of a tense/agreement inflection on a verb that appears in sentence-final position, as in Kristina Kaffee trinkt “Kristina coffee drinks”. However, this sequence can be found in the input. Specifically, this sequence appears in dependent clauses of the type seen in Ich weiβ, daβ [Kristina Kaffee trinkt] “I know that Kristina coffee drinks”. Again, if the structural ties between the matrix clause and the subsequent clause are not understood, the observed error of using a tense/agreement-marked verb in the final position of simple sentences could well result.

A somewhat different type of word order error seen in Swedish-speaking children with SLI might also have an explanation in the type of proposal put forth here. These children appear to produce the negative particle (inte “not”) either immediately after the verb marked for tense, as is appropriate (as in Kristina dricker inte kaffe “Kristina drinks not coffee”) or immediately before the verb (as in Kristina inte dricker kaffe) which is ungrammatical. However, the latter word order does appear in the input, in dependent clauses. An example of this word order is seen in the dependent clause of Jag vet att [Kristina inte dricker kaffe] “I know that Kristina not drinks coffee”. Therefore, this word order could be derived through improper extraction of the subordinate clause.

We believe the evidence from this investigation places a clinical hallmark of SLI – a protracted period of tense/agreement use – within the broader context of construction learning. Instead of reflecting a problem with tense/agreement morphemes per se, these children’s problem may rest with the pace at which they expand the repertoire of constructions that serve as the basis for their utterances. These children seem to persist in generating new utterances based on constructions in the input that do not constitute full sentences in the adult grammar. In English, this continued reliance on improper constructions for utterance generation will result in striking limitations in tense/agreement use. In other languages, the same reliance on improper constructions may well result in other types of symptoms, as we have tried to point out. Future research is clearly warranted, for there would be a major advantage in parsimony if the salient, defining characteristics of SLI in different languages could be attributed to a single factor – the retention of inappropriate constructions used for generating new utterances.

The proposal put forth here is not limited to children with SLI. We suggest that in typical development, too, there is a period during which there is asynchrony between children’s ability to understand larger structures and their ability to generate never-before-heard utterances. For typically developing children, this period is quite brief. For example, young typically developing children acquiring English will use tense/agreement morphemes inconsistently but will soon recognize that the nonfinite constructions serving as the basis for some of these utterances are structurally tied to larger sentences and not extractible. At this point, simple sentences derived from this source will decline in frequency.

Because this period of asynchrony is rather brief in typical language development, a longitudinal design might best capture it. Within such a design, verb-specific effects might also be seen, as was the case in this study. For example, lexical verbs that appear most frequently in nonfinite subject-verb sequences (e.g., We saw the girl Xing; Is the boy Xing?) in the input might be among those used most frequently without an accompanying auxiliary form in the children’s simple sentences.

If future research confirms these ideas, the way we characterize aspects of children’s grammatical development may have to be altered. In particular, children’s increase in the use of tense/agreement morphemes might not simply reflect a growing ability to apply these morphemes where they are required; this increase might also reflect a developing ability to confine particular nonfinite constructions to their proper contexts.

Acknowledgments

The work reported in this article was supported in part by research grant R01 DC00458 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health. We thank Marc Fey for his insightful comments in the development of this article, the members of the Child Language Laboratory at Purdue University for their assistance, and the families and children who participated in the project. Contact information: Laurence B. Leonard, Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, 500 Oval Drive, Heavilon Hall, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 USA.

Footnotes

To determine whether results similar to those for the TD-A group would be seen with a younger group of TD children showing considerable use of tense/agreement morphemes, we recruited four typically developing children, ages 3;1 to 3;11 who used finite verb morphemes (including auxiliary forms) in at least 90 percent of obligatory contexts. Each child was presented with two novel verbs in the nonfinite condition and two novel verbs in the tense/agreement condition. Probes requiring use of the novel verbs in contexts requiring auxiliary is were then presented to each child. As described earlier, one probe item required use of the subject noun that had been paired with the novel verb during the exposure period, and the other probe item required use of a subject noun that had not been associated with the novel verb. All four children consistently used auxiliary is for all probe items for novel verbs that had been presented in the nonfinite condition. Two of the children consistently used auxiliary is for the probe items for novel verbs presented in the tense/agreement condition, and the remaining two children produced auxiliary was for these items. However, both of these children used auxiliary was with a subject noun that had not been associated with the novel verb. The results for these younger TD children, then, were very similar to those seen for the older TD-A group.

References

- Bedore Lisa, Laurence Leonard. Specific language impairment and grammatical morphology: A discriminant function analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:1185–1192. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4105.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Dorothy VM, Caroline Adams, Courtenay Norbury. Distinct genetic influences on grammar and phonological short-term memory deficits: Evidence from 6- year-old twins. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2006;5:158–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock Kathryn, Gary Dell, Franklin Chang, Kristine Onishi. Persistent structural priming from language comprehension to language production. Cognition. 2007;104:437–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgemeister Bessie, Lucille Blum, Irving Lorge. Columbia Mental Maturity Scale. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn Lloyd, Leota Dunn. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – III. American Guidance; Circle Pines, MN: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fey Marc, Diane Loeb. An evaluation of the facilitative effects on inverted yes-no questions on the acquisition of auxiliary verbs. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:160–174. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthal Daniel, Julian Pine, Fernand Gobet. Modeling the development of children’s use of optional infinitives in Dutch and English using MOSAIC. Cognitive Science. 2006;30:277–310. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog0000_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthal Daniel, Julian Pine, Javier Aguado-Orea, Fernand Gobet. Modeling the developmental patterning of finiteness marking in English, Dutch, German, and Spanish using MOSAIC. Cognitive Science. 2007;31:311–341. doi: 10.1080/15326900701221454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg Adele E. Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson Kristina, Ulrika Nettelbladt, Laurence Leonard. Specific language impairment in Swedish: The status of verb morphology and word order. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2000;43:848–864. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4304.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusczyk Peter, Paul Luce, Charles-Luce J. Infants’ sensitivity to phonotactic patterns in the native language. Journal of Memory and Language. 1994;33:630–645. [Google Scholar]

- Kirjavainen Minna, Anna Theakston, Elena Lieven. Can input explain children’s me-for-I errors? Journal of Child Language. 2009;36:1091–1114. doi: 10.1017/S0305000909009350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Laurence, Umberta Bortolini, Caselli M. Cristina, Karla McGregor, Letizia Sabbadini. Morphological deficits in children with specific language impairment: The status of features in the underlying grammar. Language Acquisition. 1992;2:151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Laurence, Julia Eyer, Lisa Bedore, Bernard Grela. Three accounts of the grammatical morpheme difficulties of English-speaking children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:741–753. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4004.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Laurence, Kristina Hansson, Ulrika Nettelbladt, Patricia Deevy. Specific language impairment in children: A comparison of English and Swedish. Language Acquisition. 2004;12:219–246. doi: 10.1080/10489223.1995.9671744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Laurence, Carol Miller, Patricia Deevy, Leila Rauf, Erika Gerber, Monique Charest. Production operations and the use of nonfinite verbs by children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:744–758. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/060). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Laurence, Carol Miller, Erika Gerber. Grammatical morphology and the lexicon in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:678–689. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4203.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Carol, Laurence Leonard. Deficits in finite verb morphology: Some assumptions in recent accounts of specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:701–707. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4103.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond Sean, Mabel Rice. Detection of irregular verb violations by children with and without SLI. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:655–669. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/053). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice Mabel. A unified model of specific and general language delay: Grammatical tense as a clinical marker of unexpected variation. In: Levy Yonata, Jeannette Schaeffer., editors. Language Competence Across Populations: Toward a Definition of SLI. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rice Mabel, Karen Noll, Hannelore Grimm. An extended optional infinitive stage in German-speaking children with specific language impairment. Language Acquisition. 1997;6:255–295. [Google Scholar]

- Rice Mabel, Kenneth Wexler. Toward tense as a clinical marker of specific language impairment in English-speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1996;39:1239–1257. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3906.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice Mabel, Kenneth Wexler. Rice/Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rice Mabel, Kenneth Wexler, Patricia Cleave. Specific language impairment as a period of extended optional infinitive. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:1239–1257. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3804.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice Mabel, Kenneth Wexler, Scott Hershberger. Tense over time: The longitudinal course of tense acquisition in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:1412–1431. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4106.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts Stephanie, Laurence Leonard. Grammatical deficits in German and English: A crosslinguistic study of children with specific language impairment. First Language. 1997;17:131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland Caroline, Julian Pine, Elena Lieven, Anna Theakston. The incidence of error in young children’s Wh-questions. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:384–404. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/027). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theakston Anna, Elena Lieven. The acquisition of auxiliaries BE and HAVE: An elicitation study. Journal of Child Language. 2005;32:587–616. doi: 10.1017/s0305000905006872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theakston Anna, Elena Lieven. The influence of discourse context on children’s provision of auxiliary BE. Journal of Child Language. 2008;35:129–158. doi: 10.1017/s0305000907008306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theakston Anna, Elena Lieven, Julian Pine, Caroline Rowland. The acquisition of auxiliary syntax: BE and HAVE. Cognitive Linguistics. 2005;16:247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Theakston Anna, Elena Lieven, Michael Tomasello. The role of input in the acquisition of third person singular verbs in English. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:863–877. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/067). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello Michael. Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Werner Ellen, Janet Kresheck. Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test-Preschool. Janelle; DeKalb, IL: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Werner Ellen, Janet Kresheck. Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test-II. Janelle; DeKalb, IL: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wiig Eleanor, Wayne Secord, Eleanor Semel. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – Preschool 2. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Stephen. Lexically specific constructions in the acquisition of inflection in English. Journal of Child Language. 2003;30:75–115. doi: 10.1017/s0305000902005512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]