Abstract

This paper provides a critical review of two broad categories of social ecological theories of crime, social integration and place-based theories, and their relationships to spatial assessments of crime patterns. Social integration theories emphasize the role of neighborhood disorganization on crime, while place theories stress the social interactions within and between places as a source of crime. We provide an analysis of the extent to which these two types of theorizing describe processes and mechanisms that are truly ecologic (identify specific interactions between individuals and their environments) and truly spatial (identify specific movement and interaction patterns of individuals and groups) as they endeavor to explain crime outcomes. We suggest that social integration theories do not provide spatial signatures of sufficient specificity to justify the application of spatial statistical techniques as quantitative arbiters of the theory. On the other hand, place based theories go some way toward addressing these issues because the emphasis is placed on understanding the exact physical and social characteristics of place and the activities that occur around locations as sources of crime. Routine activities and crime potential theories attempt to explain clustering or “hot spots” of crime in ways that give clear spatial dimension by looking at micro-spatial interactions between offenders and targets of crime. These theories have strong ecological implications as well, since they contain specific statements about how people use the space around them and how these patterns of use are related to patterns of criminal activity. We conclude by identifying a set of requirements for successful empirical tests of geospatial theories, including the development of valid measures of key theoretical constructs and the formulation of critical empirical assessments of geospatial hypotheses derived from motivating theory.

Within the fields of drug and alcohol studies, concern with the spatial relationship between alcohol availability, drugs and crime has focused mainly upon empirical assessments of the role of alcohol outlets and sales on problems at the community level (Stockwell et al., 2005). These studies are mostly cross-sectional, and consistently have shown an association between alcohol outlet densities and violent crime. Importantly, these associations remain once social and demographic characteristics of neighborhoods, such as poverty and residential mobility, are controlled in these analyses (reviewed in Lipton et al., 2003 and Roman et al., 2008). The early focus on empirical assessments of the relationships between alcohol availability and crime was supported by spatial statistical models that were concerned with identification of correlates of health outcomes related to drinking, not crime per se (e.g., Gruenewald et al., 1996; 2000). However, this empirical and methodological literature was not a source of theoretical development or exploration. There was little attempt to identify the specific mechanisms by which the addition of alcohol outlets to communities leads to increased violent crime.

In more recent alcohol studies researchers have begun to draw on ecologic theories from within criminology in an effort to better understand the empirical observation that alcohol outlets are associated with greater rates of neighborhood crime and violence (e.g., Gruenewald, et al., 2006; Scribner et al., 2007). In this paper we identify a study as “ecologic” if its focus is on the interaction between individuals and their environments. This broad definition encompasses a great deal of variability in what researchers and theorists have come to consider relevant to the generation of violent crime. For example, the environment includes physical features such as buildings, roadways and geography, social features such as relations with neighbors, and shared norms and values, and organizational features such as law enforcement and community organizations. The definition leaves some considerable ambiguity with regard to the defining characteristics of ecological theories in the literature. One useful approach made by Anselin et al. (2000) distinguishes between theories that are defined as ecological solely because they focus on data aggregated within geographic units (e.g., census tracts), often somewhat arbitrarily identified as neighborhoods, verses theories that define how individuals are drawn to specific locations, move to and fro between them, and behave within them. They term the former as “social ecology theories” and the latter as “place-based theories”. It appears that this characterization is intended to distinguish between theories that demand different methodological or statistical treatment. Social ecology theories state or suggest correlations between variables measured across aggregate geographic units, demanding little in the way of unique statistical treatment and analytically limited by the nature of the data aggregation. Place-based theories suggest that the spatial arrangements of geographic units, and populations moving within and between those units, are uniquely important, requiring that the spatial arrangements of these units and populations be explicitly addressed using spatial statistics. The methodological significance of this distinction is, no doubt, important and we will return to it below. It should be noted, however, that this terminological distinction can be quite misleading, since some “social ecological theories” have a long tradition of being “place-based” with strong spatial implications (e.g., Goldstein, 1994).

In this paper we employ a distinction that is directed at clarifying important differences in spatial theories of crime. We divide theories into two broad categories, namely social integration theories and place-based theories. Social integration theories emphasize the role of neighborhood social disorganization on crime and place-based theories highlight the role of social interactions within and between places as a source of crime. We are interested in the extent to which these theories describe processes and mechanisms that are truly ecologic (i.e., identifying specific interactions between individuals and their environments) and truly spatial (i.e., identifying specific movement and interaction patterns of individuals and groups that can explain crime outcomes). It is our view that the influence of alcohol availability within the broader context of neighborhood social forces only can be understood through the development of such theories (Gruenewald, 2008). We demonstrate that when the spatial ecological aspects of social theory are poorly specified, there is little to be gained from the application of spatial statistical models. However, when these aspects of social theory are well specified, theoretically important spatial statistical models can be applied to analyses of crime data and inform directly on elements of the underlying theory.

Social Integration Theories: Social Disorganization, Social Capital, and Collective Efficacy

Social integration theories focus on the effects that neighborhood social and demographic characteristics have on crime, particularly the effects of poverty, concentration of ethnic minorities, and residential mobility. These theories differ primarily in terms of what they consider to be the processes that link these characteristics to crime. In the original theory of Shaw and McKay (1942), the mediating process was termed “social disorganization” and referred to the inability of communities to develop and realize a common set of norms and values and to exert social control in order to solve problems that confronted them (Bursik, 1988). Following a period in which there was little interest in the theory, it was re-introduced into the criminology literature in the late- 1980s (Stark, 1987; Bursik, 1988; Sampson & Groves, 1989). Even more recently the terms “social capital” and “collective efficacy” have been used to describe the processes through which neighborhood social and demographic characteristics are related to crime and delinquency (Kubirin & Weitzer, 2003). While no strong arguments have been presented for differentiating social disorganization from social capital theory, proponents of collective efficacy theory claim that it is conceptually distinct and more precisely specifies the societal processes that link social and demographic characteristics to crime. Putting theoretical nuances aside, we show that the larger problem for social integration theories lies in identifying specific social processes that lead from human experiences in disorganized neighborhoods to measurable crime outcomes.

The development and current refinement of social disorganization theory can best be examined through the work of Robert Sampson, one of the key figures involved in re-introducing the concept of social disorganization into criminology in the 1980s (Sampson & Groves, 1989) and an ardent proponent of collective efficacy theory (Sampson, 2006; Sampson, Raudenbush & Earls, 1997). Indeed, prior to the seminal paper of Sampson and Groves (1989), there were no empirical tests of the presumed mediating role of social disorganization in the association between social and demographic characteristics of neighborhoods and crime. The causal model tested by Sampson and Groves (1989) and described by Sampson (1992; 1995) is summarized in Figure 1. Here the key social processes mediating the relationship between community social structure and crime are sparse local friendship networks, inability to supervise teenage peer groups, and low organizational participation (see Sampson & Groves, 1989, Figure 1). The central idea is that in disorganized neighborhoods socio-structural barriers “impede the development of the formal and informal ties that promote social cohesion and the ability to solve common problems” (Sampson, 1992, page 47). This links the concept of social disorganization to social capital, as the latter is said to be greater in neighborhoods where relationships among individuals facilitate actions that result in the achievement of common goals (Sampson, 1995). Hence, social capital can be interpreted as the positive side of a coin of which social disorganization is the negative side (see also Kawachi & Berkman, 2000; Portes, 1998).

Figure 1.

Causal Model of Social Disorganization Tested by Sampson and Groves (1989)

A number of other empirical studies have lent support to the importance of one or more hypothesized variables mediating relationships between neighborhood characteristics and crime (summarized in Sampson, Morenoff & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). In the most detailed of these, Lowenkamp, Cullen & Pratt (2003) replicated Sampson and Groves’ analyses using data from the 1994 British Crime Survey and obtained results consistent with those of the earlier study. Despite this accumulation of support, Sampson has recently rejected social disorganization theory in favor of “collective efficacy” theory (Sampson, 2004; 2005; 2006). The key distinction is a rejection of the central role of supportive social networks (e.g., he argues that the “urban village” view of the inner- city as a system of tightly-knit family and friendship groupings is largely a myth) and its replacement by mutual trust and support in the pursuit of common values in which strong social ties are not necessary (Sampson, 2005). Strong social ties can actually impede efforts at social control and foster certain illegal activities like drug dealing. On the other hand, if individuals support each other in the pursuit of common values, regardless of the strength of personal ties, neighborhoods will be cohesive and exhibit shared expectations regarding normative behaviors; this constitutes collective efficacy (Sampson, 2004, 2006). “The key causal mechanism in collective efficacy theory”, Sampson states, “is social control enacted under conditions of social trust” (Sampson, 2004, page 108). According to the theory, it is the repeated interactions among residents that generate shared norms, not close ties among friends and family. In addition, it is the process of activating these relatively weak ties to address specific tasks that distinguishes collective efficacy theory from social capital theory (Sampson, 2006).

Linking Social Integration Theory to Crime

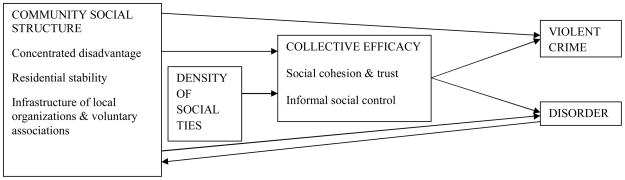

As suggested by this brief outline, the central theoretical problem for all social integration theories is the construction of conceptual links between the characteristics of disorganized neighborhoods and criminal behaviors. The common way to make these links is to view social norms as restraints on criminal behavior; these restraints are relaxed in disorganized neighborhoods. The social mechanisms by which norms propagate through neighborhoods appear to be related to the presence of strong or weak social ties and poorly describe the contact processes through which social cohesion arises or shared expectations appear among community neighbors. It is notable in this regard that observed correlations between measures of social disorganization and crime do not comprise tests of the theory but are simply a restatement of the problem to be explained. However, the demonstration of a mediating role of collective efficacy between measures of social disorganization and crime would appear to be a crucial theoretical test (see Sampson, Raudenbush & Earls, 1997: Morenoff, Sampson & Raudenbush, 2001; Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999). Thus, Morenoff et al. (2001) found that a measure of collective efficacy derived from individual self reports was negatively associated with homicide rates in Chicago and mediated much of the relationship between neighborhood social and demographic variables and violence. Since no other mediating variables, including two indicators of social capital (family and friendship ties and membership in voluntary associations), were associated with homicide they argue that density of social ties has no direct effect on neighborhood violence. This observation leads to the most recent conceptual model of collective efficacy theory described by Sampson (2006), and depicted in Figure 2. In this version, social cohesion, trust and informal social control are considered mediating variables that explain the association between concentrated social disadvantage (i.e., social disorganization) and violence.

Figure 2.

Causal Model of Collective Efficacy Tested by Sampson, Raudenbush & Earls (1997) and Morenoff et al. (2001)

It is now generally agreed that social cohesion and control are conceptually distinct from dense social ties (Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003; Sampson, 2006; Taylor, 2002). But it is unclear whether collective efficacy theory is substantially different from other social influence models, specifically social capital and disorganization theories. Taylor (2002) argues that there is no fundamental difference between collective efficacy theory and social capital theory, because the same basic mechanisms and dynamics are described by each (i.e., social cohesion and trust, shared norms and values, willingness to intervene, and community self-regulation). This view is supported by the fact that most definitions of social capital consider social control, trust and reciprocity as fundamental constructs (Portes, 1998) and the observation that social disorganization theory describes essentially the reverse of the processes posited by self-efficacy theory (i.e., absence of social cohesion and trust, absence of shared norms and values, unwillingness to intervene, and lack of community self-regulation, Taylor, 2002).

How Ecological are Social Integration Theories?

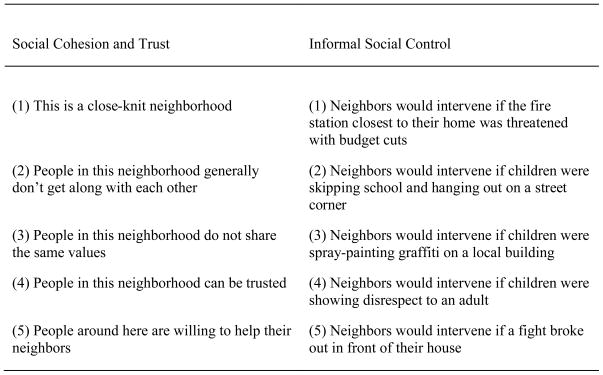

As stated above, the problem for social integration theories lies in identification of specific social processes that lead from human interactions in disorganized environments to crime. In their discussion of the concept of neighborhood disorganization, Sampson and Raudenbush (1999) note that while disorganization has been stated as an ecological construct, it “has been investigated mainly using individual perceptions and individual level research designs” (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999, page 607). Considering suitable research designs, Sampson and colleagues have used multi-level modeling and geospatial statistics in order to capture presumed ecologic and spatial processes implied by collective efficacy theory. However, it is unclear whether social integration theories generally (and collective efficacy theory specifically) provide specific testable ecological hypotheses relating characteristics of disorganized neighborhoods to crime. It is also unclear whether measures of collective efficacy provided by respondents in neighborhoods truly reflect social or social ecological, rather than psychological constructs that represent neighborhood conditions. With regard to the latter, although there is some theoretical emphasis placed on social action in collective efficacy theory, as shown in Figure 3 none of the variables that Sampson and colleagues use to measure collective efficacy actually pertain to action. Rather, they measure perceptions of one’s neighbors’ traits (e.g., trustworthiness and friendliness) and potential behaviors (e.g., willingness to uphold public order). These are perceptions and beliefs about neighbors and neighborhood conditions that may be a result rather than a cause of crime, rather than constructs that imply specific ecological interactions.

Figure 3.

Questionnaire items used to measure social cohesion/trust and informal social control in Sampson et al. (1997), Sampson and Raudenbush (1999) and Morenoff et al. (2001)

Do Tests of Social Integration Theories require Spatial Statistics?

The lack of detail provided by social integration and collective efficacy theories with regard to specific testable ecological hypotheses makes it difficult to understand the specific need for spatial statistical methodologies in theoretical tests of these models. In an effort to address this issue, Sampson (2005) has discussed the spatial implications of collective efficacy theory and used geospatial statistical techniques to ostensibly test some predictions from this model (e.g., Morenoff, Sampson & Raudenbush, 2001). He argues that the spatial dimension of collective efficacy theory arises primarily from the fact that social interactions between individuals in modern cities are not confined to traditional neighborhood boundaries used by researchers. Rather, crime and violence spread across these permeable geographic units. In addition, he notes that since offenders tend to commit crimes near their homes these acts will concentrate in those neighborhoods and that some crimes, notably those involving interpersonal and gang-related violence, are the result of social interactions that generally involve some geographic component. These ideas are not new to ecological studies (see Shaw and McKay, 1942; Brantingham and Brantingham, 1997) but do contrast with traditional work in which neighborhoods are treated as independent units. They are also hardly unique to collective efficacy theory, but rather represent three very general methodological issues of concern in any empirical study of crime across neighborhood areas; (1) travel patterns and human activities and interactions span neighborhoods, (2) specific crimes may be related to victim -perpetrator relationships associated with particular locations, and (3) artificial neighborhood boundaries may gerrymander common problems into different neighborhoods or dilute a very local aspect contained within a larger neighborhood. In essence collective efficacy theory makes no particular spatial predictions that go beyond these very general methodological points. Consequently the tests of spatial predictions from the theory are not specific to the theory itself but rather are statistical assessments of observed spatial patterns rather than their generating processes.

Place-based Theories: Crime Opportunities, Routine Activities and Crime Potentials

A better understanding of the etiology of crime in time and space requires greater theoretical specificity with regard to the types of ecological interactions that affect crime. Place- based theories go some way towards addressing these issues, as they have a much more micro-level focus than social integration theories. More precisely, they are concerned with the specific places or locales in which crime concentrates. These can be either specific types of places (e.g., bus stations and fast-food restaurants), very small geographic areas such as a stretch of a roadway that contains places of a certain type (e.g., bars), or the travel pathways that link places (e.g., the roadway that links an area containing bars to an area containing nightclubs). In each case the emphasis is on understanding the physical and social characteristics of the place and the activities that occur in and around its location.

The starting point for such research is the observation that crime is not uniformly distributed across space but tends to cluster in certain locations. Moreover, crimes of different types (e.g., robbery versus assault) may display different spatial patterns. There exists a considerable literature that has identified crime clusters of different types, which have come to be called “hot-spots”. While the identification of hot-spots has proven useful in informing decision- making in policing and other aspects of crime prevention (Block & Block, 1995; Weisburd & Mazerolle, 2000), the approach is essentially a theoretical (Roncek & Maier, 1991). Hot-spots of different types of criminal activity are identified through empirical techniques of varying sophistication, and the characteristics of these are described (e.g., there areas in which drug dealing occurs, or in which bars and/or convenience stores concentrate, or which are easily accessible from highways) (e.g., Block & Block, 1995; Sherman et al., 1989). However, the processes and mechanisms through which hot spots arise and generate crime are generally not addressed in this largely empirical literature.

Routine Activities and Crime Potential Theories

Two main theories have been developed that attempt to explain why crime clusters at a micro level of analysis, routine activities theory and crime potential theory. Each is concerned with the manner in which individuals interact while going about their everyday activities. In some discussions within the literature they have been grouped together as opportunity theories (Bottoms & Wiles, 1997; Roman et al., 2007), reflecting an intellectual heritage of studies of crime opportunities and their relationship to local social conditions that dates back to the mid 20th century (Cloward and Ohlin, 1960). The two theories differ primarily in the emphasis that they place on the role of mobility in the generation of crime, that is in whether they emphasize the movements of victims or the movements of offenders as they pursue routine daily activities.

Routine activities theory was first developed by Cohen and Felson (1979). While it has undergone some refinements in the intervening 30 years (Clarke & Felson, 1993; Felson, 1987), the basic components of the theory have remained the same. According to routine activities theory, crime occurs when a motivated offender and a suitable target are brought together in the absence of effective guardianship (Felson, 1987; Clarke and Felson, 1993). Places in which these three elements come together will be subject to greater levels of crime. The type of crime that occurs at any specific location will depend on the types of offenders and targets that it brings together. Burglaries, for example have been found to concentrate around schools (Kautt & Roncek, 2007), while violent crime concentrates around bars (Roncek & Maier, 1991). In addition, since it is the pursuit of routine daily activities (especially those of potential victims) that result in certain people being in certain places, the risk of crime will vary by such characteristics as age and gender to the extent that routine activities vary by such characteristics (Tita & Griffith, 2005).

The mechanisms through which places produce crime can also vary, and can be grouped into two basic categories crime generators and crime attractors (Parker, 1993; Roman et al., 2007). In the first instance, the routine activities of some places will produce crime by simply bringing together a large number of people, a proportion of which are likely to be suitable victims and a proportion of which are likely to be potential offenders. In such instances, other than the difficulty of providing guardianship to a very large number of people, there is nothing specific to the place that makes it conducive to crime. Events that occur at a sporting arena or an outdoor concert venue are examples of such activities. In contrast, some places will more actively produce crime through primarily attracting offenders and potential victims. Bars that encourage illegal activities on their premises, such as gambling or prostitution, are examples of such place-specific crime-attracting venues.

Do Tests of Routine Activity and Crime-Potential Theories require Spatial Statistics?

The movement of both the offender and the victim to a specific geographic location gives routine activities theory a clear spatial dimension and it allows for crime to diffuse to the extent that people are moving between locations and interacting with one another as they move. However, while offenders and targets must travel to the future crime location, the third component of the theory is an existing feature of that location (i.e., ineffective guardianship). Thus, the geographic space that routine activities theory is concerned with is essentially limited to a fixed point that displays low guardianship and that brings potential victims into contact with potential offenders (Kautt & Roncek, 2007). Absent these, and the potential offender and potential target could move about and interact within the environment without a crime ever occurring. In addition, in order for crime to diffuse beyond these fixed points, the target and offender would have to relocate to some other place in which there was little or no effective guardianship. There either the target or offender would have to encounter a new offender or target. Moreover, there exists the possibility that the roads and pathways that link places with low guardianship themselves exhibit this deficiency (e.g., sparsely populated areas that are not routinely monitored by the police). If this is the case, criminal activity has the potential to diffuse along these linkages and spread until the interaction of offenders and potential targets meets with the resistance of effective guardianship.

This issue of movement between places is more explicitly addressed in crime potential, or crime pattern, theory. Like routine activities theory, crime potential theory is concerned with the microspatial interactions between offenders and targets that occur in the course of carrying-out routine daily activities and that can be assigned to a specific location in time and space (Ratcliffe, 2006). However, whereas routine activities theory’s emphasis on guardianship leads it to focus on how specific places generate crime, crime pattern theory focuses more generally on situations that “activate” the “readiness potential” of the nascent offender (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1993). Such situations can arise not only in specific places but also along the travel routes (or paths) by which places (or nodes) are joined.

With regard to mobility, the two theories also differ in terms on which of the two parties’ activity patterns they are concerned with (Tita & Griffith, 2005). Whereas routine activities theory tends to emphasize the movement of victims as it arises in the pursuit of daily activities, crime potential theory is primarily concerned with the “travel space” of likely offenders as they go about their routine activities (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1993). These will typically be limited both spatially and temporally, with most individuals visiting relatively few places during the course of a typical day (e.g., home, school, friend’s house) and there being specific times at which each is visited (e.g., school from 8:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.). Moreover, the travel space is also circumscribed by the nature of the paths that link nodes (e.g., geographic distance, physical features such as lighting) and the methods of transportation between these (e.g., presence/absence of public transportation).

As noted by Anselin et al. (2000), routine activities theory is very specific about the mechanisms by which the features of a specific geographic location are translated into individual criminal activity (i.e., interactions that occur as a result of the organization of certain types of activities in certain types of places). The same can also be said of crime potential theory. Both theories also have strong ecological implications since they contain very specific statements about how people use the space around them and relate the patterns of mobility that occur within that space to the patterns of criminal activity that occur within it. And as Tita and Griffith (2005) observe, ultimately it is the joint mobility patterns of offenders and victims that culminate in crime, and therefore both should be of interest. Similarly, both the interactions that occur within places and during the course of movement between places have the potential to produce crime. In these respects, routine activities theory and crime potential theory are best considered as complimentary and overlapping theories of the micro-spatial ecology of crime. Thus, in recent studies of the roles of alcohol outlets and use in violent crime the two theories have been used to explain how violent crime potentials of populations are realized in these particular locations (Gruenewald, et al., 2006) and how over-concentrations of outlets attract and concentrate at-risk populations of offenders and their victims (Gruenewald, 2007, 2008).

Discussion: Geospatial Theory and the Role of Spatial Statistical Analysis

The first requirement for a successful empirical test of a geospatial theory is that the theory provides an explicit guideline to a spatial signature that should appear in data over space and, ideally, over time. As the discussion of social integration and place-based theories suggests, the spatial components of the former theories are somewhat inexplicit and the latter very explicit. For example, it is unclear what constitutes a “neighborhood” in which social disorganization affects collective efficacy and crime. On the other hand, to take an example from crime potential theory, the geographic edges between wealthy and poor areas of cities are predicted to have elevated rates of property crime, a theoretical statement which indicates a highly specific distribution of certain crimes with respect to highly specified community characteristics. This is not to say that social integration theories are incorrect, but that they do not provide spatial signatures of sufficient specificity to justify the application of spatial statistical techniques as quantitative arbiters of the theory. Geospatial theories must be developed with sufficient specificity to provide testable spatial predictions in sufficient detail to guide empirical work. As we suggest here, place-based theories appear to provide the needed level of specificity.

As noted earlier, concern with the spatial relationship between alcohol availability and crime has arisen primarily from a public health perspective. The focus has been upon empirical assessment of the role of alcohol sales in problems such as violent crime at the community level and the development of spatial statistical procedures capable of analyzing this association in an unbiased manner (Stockwell et al., 2005; Gruenewald et al., 1996; 2000). Although there has been some discussion of both social integration and opportunity theories in the alcohol availability literature, for the most part this body of research has not represented a source of theory testing or development. In the case of social integration theories, most empirical studies of the association between alcohol outlet density and violent crime have controlled for variables pertaining to community structure and social demographics in their analyses (e.g., concentrated disadvantage, residential instability, concentration of minority groups)(see, for example, Banjeree et al., 2008; Freisthler, 2004; Gorman et al., 2001). There has been little attempt to test the more sophisticated versions of these theories that involve mediating mechanisms such as social network density and social cohesion.

One exception is the recent work by Scribner and colleagues that posits social and organizational ties as the source of collective efficacy, trust and reciprocity (i.e., social capital) within a community and as the mechanism through which increased alcohol outlet density affects social capital (Scribner et al., 2007; Theall et al., 2009a; 2009b). More specifically, alcohol outlets are said to facilitate the destruction of social networks through increasing both the social and physical incivilities of community life (Theall et al., 2009b, page 331). These studies represent a marked development in the field of alcohol studies; they measure aspects of social capital, specifically in terms of archival data pertaining to neighborhood voting levels (Scribner et al., 2007; Theall et al., 2009a) and questionnaire measures of organizational membership, social cohesion and social control (Theall, et al., 2009b). At the same time, however, they highlight the limitations in the measurement of key variables from social integration theories noted above. What are still lacking are true measures of ecologic processes pertaining to social interactions within specific social contexts.

Future Research Directions

Successful empirical tests of geospatial theories require data that represent valid measures of key theoretical constructs that are mapped onto relevant geographies. These are prerequisite to having the opportunity to test relevant spatial predictions from theoretical models. The examples provided here of social integration and opportunity theories represent the best available geospatial models relating neighborhood characteristics to crime, but, as noted, even these fall short of providing specific theoretical predictions that readily translate to measurable quantities and comparisons. As a result, empirical assessments of relationships between neighborhood characteristics and crime which treat spatial effects as a nuisance to be excluded from statistical models (Sampson and Raudenbush, 1999) and the quantification of spatial patterns (Weisburd and Mazerolle, 2000) do not constitute spatial analysis in a predictive sense. Used in a predictive sense, spatial analysis can move researchers from a focus upon mere spatial associations between variables among analysis units to assessments of spatial interactions of variables between units.

In practice it is often unclear how to measure theoretical constructs (e.g., social disorganization) using available data. However, even when analysts settle for data that are available, they are often satisfied with quantitative assessments of patterns and associations rather than seeking specific spatial predictions that enable direct tests of the theories themselves. While this is a problem in all statistical approaches to large data bases, it is particularly true for geographic data, where geographic information systems allow ready access and linkage of large public data sets such as the US Census, crime, and public health databases. Such data linkages are critical, but should be recognized as best available approximations rather than optimal designs for assessing spatial theory. Spatial analytic tools relating to GIS data can enable quick summaries of spatial-based queries and aid spatial visualization of a wide variety of spatial patterns. But these tools only provide qualitative and quantitative descriptions of associations rather than experimental assessments of hypotheses derived from motivating theory.

The development of spatial statistical tools for assessing patterns as linked to underlying but indirectly observed causal mechanisms appear in both the public health and criminology literature. While addressing similar issues, to-date developments and applications within these fields have occurred independently and with little cross-fertilization. Broadly speaking, while both public health and criminological empirical studies are concerned with quantifying spatial patterns of “rates” of events, the two perspectives often make very different assumptions about the “rate” of interest. In both cases, one compares the observed and predicted number of some event of interest (typically an adverse event such as disease or criminal activity). But in public health a population based rate is often used, identifying the incidence or prevalence of a disease relative to the size of a population (for a fixed time interval) and mirroring the probability of a randomly chosen individual contracting the disease. In criminology, on the other hand, the nature of crime itself has motivated empirical practices that typically relate numbers of crime events to qualities of individuals, groups, or places. In this case there is no obvious answer to the ostensibly obvious question, “What is the suitable population denominator for a crime rate?” For example, violent crime related to alcohol outlets may not be related to the characteristics of populations living in neighborhoods where outlets are located, but only to the characteristics of persons traveling to those places to drink.

These two different notions of “rate” have motivated applications of quite different spatial analytic tools in empirical studies of public health problems and crime. In public health, the focus on case rates per population (per unit time) has lead to the use of logistic and Poisson regression models, spatial versions of which include spatially referenced error terms, often through the use of spatially-correlated random intercepts in “disease mapping” models (Waller and Gotway, 2004, Chapter 9; Lawson 2008). Such models result in spatial “smoothing” of small area rates by generating local estimates that are weighted compromises between the local data and estimates for neighboring areas. These methods offer statistical mechanisms for increasing statistical precision (lowering local variances) without giving up geographic precision, but do so at a cost: explicit assumptions about relevant populations must be established a priori in order to evaluate expectations from these models. In contrast, spatial analyses in criminology are based on “rates” accumulated as geographically local counts of events over time, rates per place (per unit time) that may have no determinable population by which to set expectations. These “rates” may be related to descriptors of these locations (e.g., numbers of alcohol outlets) and/or the populations which pass through them (e.g., commuter flow), but such “rates” no longer fit the assumptions of logistic or Poisson models.

This observation explains why operationalization of variables posited by opportunity theories has been less well-developed in the field of alcohol studies than has been the case with social integration theories. Statistically, it is much easier to treat populations as static in place than mobile between places. Social integration theories do not require detailed predictions about spatial interactions and, conveniently, do not suggest that population based rates may be an inappropriate metric by which to measure crime outcomes. As noted above, interest in the locations of alcohol outlets, and their relationships to particular problems, has been evident in the field for many years (Stockwell, et al., 2005), and criminologists have always included bars and taverns in their lists of potential hot-spots (e.g., Block & Block, 1995; Roncek & Maier, 1991; Sherman et al., 1989). Yet detailed examination of the actual movement of offenders and victims to and from alcohol outlets within communities, as well as the examination of the micro environments in which people drink, remains rare. Rather it is assumed that if crime concentrates at particular drinking venues, these venues must have attracted victims and perpetrators and be deficient in guardianship. As already observed, with their emphasis on the movement of the offender and victim to specific geographic locations, opportunity theories have very clear spatial and ecological qualities to them. However, their effective use by alcohol researchers would require more emphasis on both the different types of effects that outlets can have within a neighborhood (e.g., proximity versus amenity effects; Livingstone, Chikritzhs & Room, 2007) and the mechanisms whereby different types of individuals assort into different types of drinking venues (Gruenewald, 2007).

Acknowledgments

Research and preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by a National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant Number R21 DA024341 to the second author.

Contributor Information

Dennis M. Gorman, Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, School of Rural Public Health, Texas A&M Health Science Center, College, Texas, USA

Paul J. Gruenewald, Prevention Research Center, Berkeley, California, USA

Lance A. Waller, Department of Biostatistics, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

References

- Anselin L, Cohen J, Cook D, Gorr W, Tita G. Spatial analyses of crime. In: Duffee D, editor. Criminal Justice 2000, Volume 4, Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice. National Institute of Justice; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 213–262. [Google Scholar]

- Banjeree A, LaScala E, Gruenewald PJ, Freisthler B, Treno A. Social disorganization, alcohol, and drug markets and violence: A space-time model of community structure. In: Thomas YF, editor. Geography and Drug Addiction. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Block RL, Block CR. Space, place and crime: hot spot areas and hot places of liquor-related crime. In: Eck JE, Weisburd D, editors. Crime and Place. Crimnal Justice Press; Monsey, NY: 1995. pp. 145–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms AE, Wiles P. Environmental criminology. In: Maguire M, Morgan R, Reiner R, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1997. pp. 305–359. [Google Scholar]

- Brantingham PL, Brantingham PJ. Nodes, paths, and edges: considerations on the complexity of crime and the physical environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1993;13:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bursik RJ., Jr Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: problems and prospects. Criminology. 1988;26:519–551. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke RV, Felson M. Routine Activity and Rational Choice. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cloward R, Ohlin L. Delinquency and Opportunity. NY: Free Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LE, Felson M. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:588–608. [Google Scholar]

- Felson M. Routine activities and crime prevention in the developing metropolis. Criminology. 1987;25:911–931. [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B. A spatial analysis of social disorganization, alcohol access and rates of child maltreatment in neighborhoods. Child and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:803–819. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman DM, Speer PW, Gruenewald PG, Labouvie EW. Spatial dynamics of alcohol availability, neighborhood structure and violent crime. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:628–636. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AP. The Ecology of Aggression. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PG. The spatial ecology of alcohol problems: niche theory and assertive drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:870–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PG. Why do alcohol outlets matter anyway? A look into the future. Addiction. 2008;103:1585–1587. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PG, Remer L. Changes in outlet densities affect violence rates. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1184–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Freisthler B, Remer L, LaScala EA, Treno A. Ecological models of alcohol outlets and violent assaults: Crime potentials and geospatial analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:666–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Millar AB, Treno AJ, Yang Z, Ponicki WR, Roeper P. The geography of availability and driving after drinking. Addiction. 1996;91:967–983. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9179674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Millar AB, Ponicki WR, Brinkley G. Physical and economic access to alcohol: The application of geostatistical methods to small area analysis in community settings. In: Wilson R, Dufour M, editors. Small Area Analysis and the Epidemiology of Alcohol Problems, NIAAA Research Monograph. NIAAA; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kautt PM, Roncek DW. Schools as criminal “hot spots”: primary, secondary and beyond. Criminal Justice Review. 2007;32:339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Kawachi I, Berkman L, editors. Social Epidemiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kubirin CE, Weitzer R. New directions in social disorganization theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2003;40:374–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson AB. Bayesian Disease Mappping: Hierarchical Modeling in Spatial Epidemiology. CRC/Chapman & Hall; Boca Raton, FL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton R, Gorman DM, Wieczorek WF, Gruenewald PG. The application of spatial analysis to the public health understanding of alcohol and alcohol-related problems. In: Khan OA, editor. Geographic Information Systems and Health Applications. Idea Group Publishing; Hershey, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M, Chikritxhs T, Room R. Changing the density of alcohol outlets to reduce alcohol-related problems. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2007;26:557–566. doi: 10.1080/09595230701499191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenkamp CT, Cullen FT, Pratt TC. Replicating Sampson and Groves’’s test of social disorganization theory: Revisiting a criminological classic. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2003;40:351–373. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology. 2001;39:517–559. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. Alcohol and theories of homicide. In: Adler F, Laufer WS, editors. New Directions in Criminological Theory: Advances in criminological theory. Vol. 4. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1993. pp. 113–41. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe JH. A temporal constraint theory to explain opportunity-based spatial offending patterns. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2006;43:261–291. [Google Scholar]

- Roman CG, Reid SE, Bhati AS, Tereschchenko B. Alcohol outlets as Attractors of Violence and Disorder: A Closer Look at Neighborhood Environment. Urban Institute; Washington, D.C: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roncek DW, Maier PA. Bars, blocks, and crimes revisited: Linking the theory of routine activities to the empiricism of “hot spots”. Criminology. 1991;29:725–753. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Family management and child development: Insights from social disorganization theory. In: McCord J, editor. Facts, Frames, and Forecasts. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick, NJ: 1992. pp. 63–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. The community. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J, editors. Crime. ICS Press; San Francisco, CA: 1995. pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Neighborhood and community: Collective efficacy and community safety. New Economy. 2004;11:106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Social ecology and collective efficacy theory. In: Henry S, Lanier MM, editors. Essential Criminology Reader. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 2005. pp. 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevens K, editors. Taking Stock: The Status of Criminological Theory. Transaction Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 2006. pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. Criminology. 1989;94:774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush R. Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105:603–651. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Disorder in urban neighborhoods – does it lead to crime? National Institute of Justice Research in Brief. US Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–48. [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R, Theall KP, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Mason K, Cohen D, Simonsen N. Determinants of social capital indicators at the neighborhood level: A longitudinal analysis of loss of off-sale alcohol outlets and voting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2007;68:934–943. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CR, McKay HD. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman LW, Gartin PR, Buerger MR. Hot spots of predatory crime: Routine activities and the criminology of place. Criminology. 1989;27:27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R. Deviant places: A theory of the ecology of crime. Criminology. 1987;25:893–909. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Gruenewald PJ, Toumbourou J, Loxley W. Preventing Harmful Substance Use: The Evidence Base for Policy and Practice. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RB. Fear of crime, local social ties, and collective efficacy: Maybe masquerading measurement, maybe deja vu all over again. Justice Quarterly. 2002;19:773–92. [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Scribner R, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Cohen D, Mason K, Simonsen N. Neighborhood alcohol availability and gonorrhea rates: impact of social capital. Geospatial Health. 2009a;3:241–255. doi: 10.4081/gh.2009.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Scribner R, Cohen D, Bluthenthal RN, Schonlau M, Farley TA. Social capital and neighborhood alcohol environment. Health and Place. 2009b;15:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tita G, Griffith E. Travelling to violence: the case for a mobility-based spatial topology of homicide. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2005;42:275–308. [Google Scholar]

- Waller LA, Gotway CA. Applied Spatial Statistics for Public Health Data. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd D, Mazerolle LG. Crime and disorder in drug hot spots: implications for theory and practice in policing. Police Quarterly. 2000;3:331–349. [Google Scholar]