This article examines the pros and cons of using different autologous stem cell sources for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) therapy, the requirements they must fulfill to provide therapeutic benefit, and the current progress toward characterizing the cells' ability to synthesize elastin, assemble elastic matrix structures, and influence the regenerative potential of diseased vascular cell types. The article also provides a detailed perspective on the limitations, uncertainties, and challenges that will need to be overcome or circumvented to translate current strategies for stem cell use into clinically viable AAA therapies.

Summary

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are potentially fatal conditions that are characterized by decreased flexibility of the aortic wall due to proteolytic loss of the structural matrix. This leads to their gradual weakening and ultimate rupture. Drug-based inhibition of proteolytic enzymes may provide a nonsurgical treatment alternative for growing AAAs, although it might at best be sufficient to slow their growth. Regenerative repair of disrupted elastic matrix is required if regression of AAAs to a healthy state is to be achieved. Terminally differentiated adult and diseased vascular cells are poorly capable of affecting such regenerative repair. In this context, stem cells and their smooth muscle cell-like derivatives may represent alternate cell sources for regenerative AAA cell therapies. This article examines the pros and cons of using different autologous stem cell sources for AAA therapy, the requirements they must fulfill to provide therapeutic benefit, and the current progress toward characterizing the cells' ability to synthesize elastin, assemble elastic matrix structures, and influence the regenerative potential of diseased vascular cell types. The article also provides a detailed perspective on the limitations, uncertainties, and challenges that will need to be overcome or circumvented to translate current strategies for stem cell use into clinically viable AAA therapies. These therapies will provide a much needed nonsurgical treatment option for the rapidly growing, high-risk, and vulnerable elderly demographic.

Need for Alternatives to Surgical Management of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are multifactorial conditions involving destructive remodeling of the matrix of the abdominal aortic wall by inflammatory and immune cells recruited in response to genetic or environmental stimuli (e.g., lipid deposits, reactive oxygen species, bacterial infection, hypertensive forces, etc.) [1]. Such slow matrix disruption results in thinning and abnormal expansion of the walls of abdominal aortae, which over time weaken, dissect, and fatally rupture. AAAs afflict 2%–9% of elderly people in the U.S. [1], including 8% of senior males (i.e., approximately 1.3 million men) and especially white smokers, who are now recognized as a high-risk population for the disease. Recognizing that AAAs are frequently asymptomatic until well developed, the U.S. Medicare program approved proactive, one-time screening for these high-risk individuals via high-resolution ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging that has greatly enhanced their early detection. Since >90% of detected AAAs tend to be small (i.e., maximal diameter <5.5 cm) and pose negligible rupture risk (<1% per year) [2], they are periodically monitored until they grow to a critical size (≥5.5 cm) or exhibit growth rates that exceed 0.5 cm/year. AAAs are very rupture-prone when they grow at these faster rates, and thus warrant either open surgical repair or minimally invasive endovascular aneurysm repair involving deployment of a stent graft. Since small AAAs grow very slowly (<10% diameter increase per year) [3], aortae that have just acquired AAA classification (i.e., representing a 50% size increase over healthy size, or a 3-cm diameter) may take ≥5 years to reach a rupture stage [4]. This extended period of passive surveillance of small AAAs offers an ideal, but unused, window of opportunity for drug-based therapy to prolong, arrest, or regress their growth. Such a therapy would most benefit frail elderly patients or those with limited life expectancy for whom AAA surgical repair is not appropriate and for whom there is no alternative to ultimate catastrophic rupture. Since surgery on small AAAs in such patients also does not provide any survival advantage over passive surveillance [5], development of nonsurgical approaches to limit, arrest, or even potentially regress AAA growth is a high priority.

Stages of AAA Pathological Changes to Arterial Extracellular Matrix

Studies of induced AAAs in rodent models [6–8] and human AAAs have shown that elastolytic matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9 are chronically overexpressed in AAA tissue, and production/activity of collagenolytic MMP1 and MMP8 are also temporarily increased [6]. These elastolytic enzymes are produced from several types of cells, including proinflammatory macrophages recruited to the site of the AAA [9, 10]. Unlike occlusive atherosclerosis in small-diameter arteries, these proinflammatory cells are distributed throughout most of the arterial wall with AAAs. In addition to the AAA tissue itself, higher MMP levels have also been detected in circulating blood of AAA patients [11]. These enzymes initiate AAA formation and lead to its slow growth to rupture. Importantly, the pathology of AAAs is very different from that of thoracic aortic aneurysms, which are more commonly associated with genetic syndromes.

AAA formation results from a disruption of collagen and elastic matrix in three sequential stages, as described in more detail elsewhere [1, 12]. Briefly, the breakdown of elastic lamellae in the tunica media of the aortic wall occurs in the first stage. This compromises the mechanics of the vessel and results in elastin degradation products that further propagate the inflammatory reaction. Arterial collagen, despite its early loss, initially recovers in small, growing AAAs [8], although the collagen tends to be disorganized [9]. At this stage, medial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and adventitial fibroblasts exhibit a tissue generation response, resulting in neovascularization and collagen production to balance its degradation by proteases [9]. Such recovery may explain the low propensity of small AAAs to rupture [8]. However, collagen does not possess the elasticity that is required to prevent plastic deformation, and bulging occurs over time with matrix degradation and remodeling. Hence, the AAA continues to expand. Finally, substantial decreases in the SMC population and increases in thrombosis in late-stage aneurysms result in decreased collagen synthesis and increased breakdown of existing collagen. The resulting wall thinning and focal weakening greatly increase the propensity of the AAA wall to rupture. This article focuses on elastic matrix repair since its regeneration by adult vascular cells is inherently limited [13, 14], unlike collagen, and since deterring or compensating for its loss can potentially prevent progressive AAA growth at an early stage.

Regenerative Repair of Aortal Elastic Matrix Is Critical to Stabilize AAAs

The lack of elastic matrix recovery postdisruption has been linked to limited elastic recoil of the vessel, decreased circumferential stiffness, slow wall dilatation and thinning, and local stress concentrations [15]. When the peak stress on the aortic wall exceeds the wall strength, rupture occurs [16]. Wall stress distribution and location, and magnitude of peak stress depend on both AAA size and the curvature of the AAA bulge, which in turn are determined by wall thinning and matrix loss. In small AAAs—where elastin disruption is a slow, ongoing process, except in isolated pockets—overall wall thinning and bulging tend to be far less than in large AAAs [17]. This may account for their higher wall strength and low peak wall stresses, which are ∼10-fold lower than in large AAAs [17]. The low peak stress to wall strength ratio exhibited by small AAAs implies a low rupture risk. As a result, less than 12% of small AAAs tend to rupture [18]. However, it also suggests that by focusing on restoring the aortal elastic matrix, we may be able to delay increases in rupture risk of small AAAs, and even lower the risk by reducing bulge-associated peak stresses and improving wall elasticity.

Both local changes to aortic wall microstructure and hemodynamic factors (e.g., chronic hypertensive forces) are known to contribute to AAA growth. However, there is strong evidence that AAA wall matrix disruption can proceed independently of flow stresses. First, reducing blood pressure with drugs does not appear to have any effect on reducing AAA expansion rates in a clinical trial [19]. Second, inhibiting intracellular signaling molecules (e.g., c-Jun N-terminal kinase [JNK]), necessary for in vivo MMP production by AAA SMCs, has been shown to be sufficient to slow and regress AAA growth in a mouse model [20]. It has also been shown that stent grafting in small (i.e., 4–5 cm) AAAs, which serves to exclude the aortic wall from flow stresses, fails to prevent continued slow wall expansion in a clinical trial [21]. Thus, concurrently reinstating lost elastic matrix within AAAs and limiting proteolytic loss may be sufficient to slow or arrest AAA growth, or even potentially reduce AAA bulge and/or curvature.

Elastogenic Insufficiency of Adult Vascular Cells Necessitates Inductive Therapy

Any drug-based therapy for small AAAs must essentially counter two major growth determinants: elevated and sustained proteolytic activity in AAA tissues, and the lack of self-repair or replacement of disrupted aortal elastic matrix. Although there are currently no established pharmacotherapies for AAAs, recent studies have indicated the promise of MMP inhibitors such as doxycycline (DOX) in attenuating chronic matrix proteolysis within AAAs and slowing AAA growth. This has been demonstrated in subcritically sized AAAs in both animal models [6, 8] and human patients [6, 8]. However, complete growth arrest of AAAs or their regression in terms of bulge reduction mandates regenerative repair of disrupted elastic matrix structures and restoration of healthy aortal elastic matrix levels to an extent that elastogenesis significantly exceeds elastolytic matrix loss, resulting in net accumulation of elastic matrix. Restoration of elastic matrix quality (i.e., fiber composition and structure, integrity, and stability) is also critical to reinstate both healthy vessel mechanics and cell signaling [22]. Additionally, intact, pre-existing elastic fibers within AAA tissues must be preserved since they serve as nucleation sites for new elastic fiber assembly [23]. However, elastin content within AAAs actually shows a progressive decrease because it is insufficiently replaced relative to its loss [8]. This is partially due to both reduced tropoelastin mRNA stability and expression in postneonatal cells [24] and the inability of cell-mediated elastin repair mechanisms in adult tissues to mimic the temporal, spatial, and mechanistic complexity of prenatal elastogenesis [25]. These concerns are even more significant for patients afflicted by proteolytic disease. Thus, slowing AAA growth, or even reducing AAA bulge/curvature, requires a two-pronged therapeutic approach that both stimulates AAA cells to increase de novo elastic matrix assembly and attenuates the production and activity of MMPs that are chronically overexpressed in AAA tissues. Furthermore, disrupted, pre-existing elastic matrix structures can be repaired by new tropoelastin synthesis on existing elastic fibers and by re-formation of disrupted desmosine and isodesmosine cross-links [26].

Limitations of Approaches to Inducing Elastin Regenerative Repair in AAAs

Almost all aneurysm therapies that have been explored to date have sought to counter either poor elastogenesis or enhanced elastolysis, but not both. Controlled growth factor delivery to cells, primarily studied within in vitro tissue engineered constructs, may be usefully adopted to also enhance elastin regeneration within AAA tissues. Resident SMCs would be one of the primary targets for elastogenic and anti-inflammatory factors. Although adult SMCs have limited elastogenic capacity in healthy tissue, they are even more limited in the inflammatory AAA environment. With AAAs, SMCs have been shown to dedifferentiate into a more proliferative and synthetic phenotype [9, 27]. Even though synthesis of collagen is increased in AAAs, synthesis of elastic matrix by aneurysmal SMCs is decreased compared with that synthesized by healthy SMCs [28]. This phenotypic change can lead to telomere shortening and cell “aging” [29]. However, it has been demonstrated that SMC activation is a reversible process and that growth factors/other biomolecules are one type of microenvironmental cue that that can promote a contractile SMC phenotype [30]. Studies in the authors' laboratory have, for example, demonstrated the in vitro benefits of hyaluronan oligomers and transforming growth factor-β for enhancing elastin synthesis and fiber formation in rat and human aortic SMC cultures, both healthy [31] and aneurysmal [28, 32]. Recent approaches have also shown that tissue regenerative agents, such as dextran-based heparin-sulfate mimics, stimulate tissue repair by protecting endogenous transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β, a known elastogenic factor) [33]. These agents may be useful to stabilize AAA against growth. Differently, pharmacologically inducing TGF-β production by aneurysmal SMCs [34] or overexpressing TGF-β production by endovascular gene delivery [35, 36] has also been shown to provide benefits in AAA diameter stabilization. Recent findings suggest that targeted inhibition of microRNAs (e.g., miRNA-29), which is found to be overexpressed in animal models of induced aortic aneurysms [37], results in enhanced elastin mRNA expression and matrix synthesis, both in vitro and in vivo to slow aortic dilatation [38]. As mentioned previously, MMP inhibitors such as DOX have been shown to slow AAA growth in rodent models [6, 8] and in humans [6, 8], although not to arrest or regress this growth, likely because of the lack of elastogenic effects. Some groups have proposed [39], and our own yet unpublished studies have substantiated, that active inhibition of elastic matrix deposition by DOX occurs in a dose-dependent manner. Inhibiting intracellular signaling pathways (JNK) involved in triggering MMP overexpression in AAAs also appears sufficient to slow and regress AAA growth [20]. Although it was acknowledged that JNK inhibition likely enhances regenerative tissue repair as well, a direct link to enhanced elastogenesis has not been established.

Cell therapy is one strategy that has the potential to provide miRNA, produce a range of proelastogenic factors, and reduce MMP expression, with potentially fewer ethical and technical concerns than gene therapy. For example, endovascular delivery of syngeneic vascular SMCs has been shown to reduce MMP activity and promote stabilization of AAAs after 8 weeks in a rat model [40]. However, elastic matrix was not regenerated in this study by these adult vascular cells, and regression of the AAA did not occur. Clinical translation of cell therapies and other AAA therapeutic approaches must necessarily (a) enhance elastogenesis and suppress proteolytic matrix disruption; (b) deliver therapeutics in a localized, controlled, and predictable manner for sustained action; (c) overcome poor ability of AAA SMCs, despite elastogenic induction, to cross-link elastin precursors into matrix structures [28]; and potentially even (d) supplement elastic matrix synthesis by elastogenically induced AAA cells. Cell therapy via introduction of more highly elastogenic, autologous cell types within AAAs may represent an effective and clinically translatable treatment strategy to achieve these outcomes. To date, there is no clinically approved cell therapy for treating AAAs, but the current progress in animal models, as described in the following sections, provides evidence of feasibility of the approach.

Stem Cell-Based Regenerative Repair of AAAs

The poor elastogenicity of terminally differentiated, adult SMCs excludes their use for AAA cell therapy [13]. Stem cells represent an alternate cell source that could be useful for regenerative tissue repair. Vascular elastin is primarily synthesized and matured during fetal and neonatal development in tissue microenvironments rich in stem/progenitor cells. Also, neonatal SMCs are far more elastogenic than adult SMCs [13]. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that stem cells or their recent smooth muscle cell-like derivatives would retain the higher elastin production and matrix assembly that adult aortic cells and AAA SMCs appear to have lost. These cells might also serve to coax AAA SMCs to a more elastogenic state via juxtacrine or paracrine signaling. The identification of a source of highly elastogenic SMCs that may be noninvasively procured and rapidly expanded in culture is critical to the clinical viability of a stem cell-based therapy for AAAs. The use of autologous stem cells provides the benefits of enabling patient-customized therapy, eliminating the need for a compatible donor, proffering no risk of incompatibility, and having low rates of complications and infections relative to allogeneic transplants [41].

Several sources of autologous adult stem cells and progenitor cells, such as bone marrow, peripheral blood, and adipose tissues, are available. These mutipotent cells can potentially be useful for AAA therapy when used either in an undifferentiated state or immediately following differentiation. Although it has been feasible to differentiate such stem/progenitors cells into cells closely resembling vascular cell types (e.g., endothelial cells, SMCs, and fibroblasts) [42, 43], their use for cell therapy may be limited by their low incidence in source tissues and low yields during isolation [44]. This challenges scalable production of undifferentiated stem cells and cells of desired lineages derived from them. The ability of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to be indefinitely proliferated in culture for many population doublings, in an undifferentiated state, is a definite advantage in this context. The pluripotency of ESCs also enhances their differentiation potential relative to mostly multipotent adult stem cells. However, therapeutic use of ESCs or ESC derivatives is limited by ethical concerns and practical limitations of immunogenicity and rejection when allografted [45]. Although several strategies have been investigated to reduce the immunogenicity of the nonautologous ESCs [46], one of the best ways to circumvent the immunogenicity challenge is by using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). With recent advances in the development of innovative iPSC techniques, it might be possible to generate targeted and individualized cell lines by “reprogramming ” somatic cells from a patient's own tissues [47]. iPSCs closely resemble ESCs in their biological properties (e.g., morphology, markers, growth characteristics, gene expression, telomerase activities), pluripotency, and differentiation potential [44, 48]. It is important, from the standpoint of preventing tumorigenecity, that the proliferation rate of these iPSCs not be too high. Recent progress has been made in generating iPSCs from a variety of cell types (e.g., fibroblasts and adipose-derived stem cells) and species (i.e., human [49, 50], murine [49, 51], and rat [52]), and also in demonstrating the feasibility of differentiating murine [51] and human iPSCs (hiPSCs) [50] into functional SMC-like cells. These outcomes show progress toward generating SMC-like cells that can initially be tested in AAA animal models and ultimately used in customized cell-based therapies in humans using hiPSC-derived SMCs.

Several requirements must be met for autologous stem cells to be used for regenerative AAA repair. First, scalable production of cells for therapeutic use must be achievable by rapid propagation of the undifferentiated cells and/or their derivatives in culture, since uncertain cell fate in the diseased tissue microenvironment and limitations to cell delivery/uptake will necessitate inoculation of large-cell numbers [53]. Second, if SMC-like, stem cell-derived cells are to be used for cell therapy, different differentiation and purification strategies must be compared to identify that which generates a highly pure population of cells exhibiting phenotypic and functional characteristics that closely resemble mature SMCs, and yet exhibit high elastogenicity. Third, from the standpoint of safety, generation of pure populations of nontumorigenic derived cell populations would be vital.

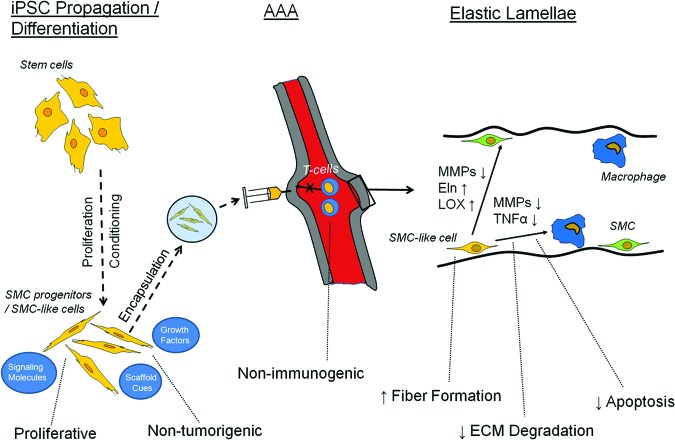

The requirement for high elastogenic capacity of stem cells and/or their SMC-like derivatives is very important for the regenerative repair of AAA tissue matrix, and is the focus of this article. Pluripotent cells would be expected to fulfill several key and indispensable functions, summarized in Figure 1, in a sustained manner in the proteolytically active and dynamic AAA tissue microenvironment. This figure includes a predifferentiation step, since for safety reasons pluripotent stem cells should be predifferentiated into SMC progenitors prior to delivery. The SMC-like cells could also be encapsulated within a protective microenvironment (e.g., microbeads) to initially shield them from the diseased aneurysmal environment. Within the arterial tissue, the stem cells will need to both exhibit a more elastogenic SMC-like phenotype themselves and modulate the expression of SMCs and macrophages already present in the aneurymal tissue. Paracrine signaling would be the initial signaling mechanism if microbeads are used for delivery. For example, it has already been shown that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) within alginate microbeads release fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1), FGF-2, TGF-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor, although the exact profile of growth factor release by encapsulated cells would depend upon the encapsulating material and the incorporation of cell adhesion factors that also critically influence cell phenotype [54]. Separate studies have also shown that MSCs release insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in vitro [55]. Many of these factors are known to either enhance (e.g., TGF-β and IGF-1) or reduce (e.g., FGF-2) elastogenesis. IGF-1 has been linked to tropoelastin gene upregulation through a decrease in binding of the transcription factor Sp3, which represses gene expression [56]. Anti-elastogenic FGF-2 has been linked to increased binding of the Fra-1/c-Jun repressor complex to the tropoelastin promoter sequence [57]. Finally, the increased transcription of tropoelastin by TGF-β has been linked to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt activity [58]. However, it is important to note that the production of tropoelastin is only one of the key challenges to elastic fiber production. Others include the production of a microfibrillar scaffold, the coacervation of tropoelastin, and its cross-linking with lysyl oxidase [59]. These post-translational modifications are greatly impacted by extracellular matrix composition and other microenvironmental cues, as described in detail elsewhere [60]. Although microencapsulated cells delivered to AAA would signal through paracrine mechanisms, juxtacrine signaling is possible later after the microcapsules degrade and the cells within colocalize with resident aneurysmal cells. Juxtacrine signaling would likely occur through cleavage of Notch receptors, a pathway that that has been shown to impact vascular cell phenotype [61]. Overall, the goal of any cell therapy technique is that elastic fiber formation occurs faster than the rate at which the existing elastic matrix is disrupted.

Figure 1.

Ideal characteristics and expected roles of iPSCs and differentiated SMC-like derivatives for treating AAAs. Shown are several of the necessary properties for expansion/differentiation in culture, delivery to the AAA, and elastogenesis within the tunica media microenvironment. Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; ECM, extracellular matrix; Eln, elastin; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; LOX, lysyl oxidase; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; SMC, smooth muscle cell; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Net elastic fiber generation requires (a) generation of elastin precursors (tropoelastin) at levels that greatly exceed that produced by aneurysmal and even healthy aortic SMCs, (b) recruitment and cross-linking of these precursors into matrix structures in a highly efficient manner so as to enhance the typically low (<1%–2%) [28, 32] yield of elastic matrix (i.e., fraction of total secreted elastin in the matrix form), (c) enhancement of the activity or production of the elastin cross-linking enzyme lysyl oxidase (LOX) to improve stability/proteolytic resistance of the deposited matrix, and (d) overcoming inherent deficiencies of elastic matrix assembly in aneurysmal tissue microenvironments. For example, our own yet unpublished studies of elastase-induced rat AAAs have provided evidence that neointimal remodeling within is associated with new elastin deposits. However, mature fiber formation was poor. This lack of maturity is likely due to deficiencies in deposition of fibrillin micofibril prescaffolds vital to elastic fiber assembly, as has been demonstrated by other groups [59]. A primary goal of cell therapy for AAAs is to address the critical concerns within the aneurysmal microenvironment, which we have described above. Since mature and intact elastic fibers critically determine vascular tissue mechanics and maintain healthy SMC phenotype [22], stem cells/stem cell derivatives need to facilitate and enhance elastic fiber assembly to a level that overcomes chronic MMP-mediated proteolysis. The ability of the incorporated cells to signal aneurysmal SMCs (e.g., via the mediation of secreted growth factors) and to coax them to a more elastogenic, and less activated, phenotype is also highly desirable. In this context, a recent study showed that MSCs from both mouse and human sources generate significant levels of TGF-β [62], a growth factor that we have shown earlier to be elastogenic and to improve elastin synthesis, elastic matrix deposition and yield, and elastic fiber assembly by aortic SMCs [63]. The ability to signal aneurysmal SMCs to switch to a less activated phenotype is critical, since both of the two major AAA growth determinants—namely, (a) elevated and sustained proteolytic activity, and (b) deficient/aberrant regenerative repair of elastic matrix—must necessarily be countered to stabilize AAAs against growth and potentially reduce AAA bulge/curvature. If the stem cells do not shift the balance between elastin regeneration and elastolysis to favor net elastic matrix accumulation, alternate strategies, such as supplementation of stem cell therapy with drug-based inhibition of MMPs (e.g., doxycycline), would be required to generate tangible therapeutic outcomes.

Current Progress Toward Stem Cell Therapies for AAAs

Table 1 summarizes the limited body of knowledge pertinent to characterization of stem cells and their derivatives in the context of elastin synthesis, elastic matrix assembly, and AAA therapy. Although a detailed discussion of the pertinent literature is beyond the scope of this article, it might suffice to mention that comprehensive and systematic characterization of the various steps and processes involved in elastogenesis (i.e., elastin precursor synthesis, precursor recruitment and cross-linking, and fiber assembly and organization into superstructures) by different stem cell types and their SMC-like derivatives is lacking. This information would be indispensable toward any tissue regenerative application. The information that is available is limited to evidence that (a) stem cells can be differentiated into cells that phenotypically and functionally resemble mature vascular SMCs, and that the stem cells and their SMC-like derivatives can (b) express elastin mRNA [64], (c) secrete elastin precursors [65, 66], and (d) generate growth factors (e.g., TGF-β) [62] known to regulate elastic matrix synthesis/assembly. Other studies have shown that providing dynamic stretch [67] and increasing substrate compliance [68] enhance stem cell differentiation into SMCs and increase their expression of elastin mRNA and synthesis of elastin protein. Promising outcomes of the first investigations into the utility of stem cells for AAA treatment have only recently been published. Turnbull et al. showed that autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs injected into porcine AAA tissue engraft successfully and are retained in the tissue 1 week later [69]. Seminal work by Hashizume et al. showed murine MSCs to attenuate both elastolytic MMP2 and MMP9 activity and inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α) production by murine macrophages, and to increase elastin synthesis by murine aortic SMC in culture [70]. The same study also demonstrated that MSCs implanted peri-adventitially onto angiotensin II-infusion-induced AAAs in apoE−/− mice attenuated MMP2/9 activity and TNF-α production, and enhanced elastin content within, to stabilize them against growth [70]. More recently, Sharma et al. showed that MSCs introduced into elastase-infused mouse aortae protect against AAA formation via immunomodulation of the inflammatory mediator interleukin-17, which is generated by recruited CD4+ T cells [27]. Despite these positive outcomes in animal models of AAA, any possible benefits to the quantity and quality of matrix regeneration, especially that of elastic matrix, remain an unknown and require elucidation. Furthermore, current AAA studies in animal models have primarily tested the therapeutic effect of stem cells derived from bone marrow [40], and few studies have tested other types of stem cells. Multipotent adult cells derived from adipose tissue were used for AAA cell therapy in one study [71], although elastogenesis was not investigated in this work. The elastogenicity of pluripotent stem cells is yet to be explored.

Table 1.

Summary of the elastogenic capability of stem cells

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; PDGF-BB, platelet-derived growth factor BB; SMC, smooth muscle cell; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β.

Future Outlook, Needs, and Challenges

Although the early studies into the efficacy of stem cell therapies for AAAs have generated promising findings, clinical translation of these strategies in the future is contingent on elucidating several unknowns and circumventing critical impediments. The first challenge is to develop strategies to generate or isolate uniform and pure populations of nontumorigenic, autologous stem cells, and to propagate these or their SMC-like derivatives rapidly in culture without further differentiation. In addition to the inoculation requirements for AAA therapy, it is important that these cells have elastogenic capacity. An in-depth elastogenic characterization of these stem cells either in an undifferentiated state, or in various stages of differentiation toward an SMC-like phenotype would be beneficial. It is also important to identify specific conditions of culture or differentiation protocols that are conducive to the generation of cells that (a) exhibit the greatest relative elastogenic potential, and (b) assemble structural and biological mimics of native vascular elastic matrix with high efficiency and fidelity. A second challenge is to verify that these stem cells also have a positive impact on aneurysmal SMCs and other cells typically present within AAAs. It is important to conduct systematic investigations into whether and how undifferentiated stem cells and differentiated SMC-like cells, derived via varied differentiation protocols, regulate aneurysmal SMC phenotype and their functional ability to regenerate and repair elastic matrix. In these studies, it appears to be important to differentiate between paracrine and juxtacrine signaling effects of the stem cell/derivatives, since our unpublished studies indicate significant differences between the two. It is likely that the relative dominance of paracrine versus juxtracrine signaling is partially determined by the extent of cell-cell contacts, although this requires further investigation in the context of AAAs. Thus, careful control over cell densities and seeding ratios (i.e., stem cell/derivatives to resident aneurysmal SMCs/macrophages) may be important to modulate elastogenic outcomes. These outcomes include enhanced elastin synthesis and matrix assembly, restoration of healthy aortic matrix composition and structure, attenuated proteolysis by vascular SMCs, and reduced cytokine production and MMP production and activity by macrophages.

Developing an understanding of the countereffects of inflammatory cell (e.g., macrophage, immune cell, and aneurysmal SMC) signaling on stem cell behavior is critical to the sustained therapeutic efficacy of stem cells or their derivatives in the AAA microenvironment. These countereffects would be best evaluated systematically in appropriate animal models of AAAs [72]. However, some information could be obtained by in vitro culture, as long as attempts are made to replicate the three-dimensional microenvironment, vascular tissue compliance, and dynamic stretch conditions found in vivo. All three of these factors are important since they are known to modulate cellular elastogenesis [72–74]. Although elastogenic and other behavioral characterization of cells obtained from various nonhuman sources would allow further evaluation of their therapeutic efficacy in corresponding animal models of induced AAAs [72], a parallel study of human stem cells/derivatives is important to establish clinical correlates. Since direct testing of these cells in humans is not feasible, their therapeutic/reparative efficacy must be established instead in surrogate organ culture systems, such as of human AAA tissues at defined stages of progress. Finally, development of clinically translatable strategies for minimally invasive, localized, and highly efficient cell delivery to aneurysmal tissues is also a critical area of research that will facilitate in vivo assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of AAA cell therapies. In this context, both endovascular (e.g., catheter and stent-facilitated) [75] and perivascular (i.e., injection-based) [69] cell delivery strategies have been explored. These strategies have demonstrated some uptake and engrafting within the AAA tissue and at least short-term retention. The latter strategy, although potentially more invasive, may be more relevant and easier to pursue since (a) AAAs represent a disease afflicting the aortic media and adventitia rather than the intima, and (b) tissue uptake of endovascularly delivered cells is likely to be limited by the luminal endothelium and the frequent presence of intramural thrombi at the aneurysm sites. The ongoing development of microbead-based cell delivery vehicles also has the potential to enhance efficiency of stem cell delivery to AAA tissues, restrict their migration, localize their effects, and above all maintain their viability and functionality in the hostile, inflammatory aneurysmal tissue microenvironment [54].

Conclusion

Sustained progress on the multiple challenges identified above in the coming years will critically determine the clinical feasibility of stem cell-based regenerative strategies for stabilization, arrest, or even regression of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Viable strategies will provide a much-needed nonsurgical treatment option for the rapidly growing and high-risk elderly demographic.

Author Contributions

C.A.B., R.R.R., and A.R.: financial support, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Mechanisms of abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2002;4:222–227. doi: 10.1007/s11883-002-0023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaikof EL, Brewster DC, Dalman RL, et al. The care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:S2–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isselbacher EM. Thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2005;111:816–828. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154569.08857.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klink A, Hyafil F, Rudd J, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:338–347. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, et al. Quality of life, impotence, and activity level in a randomized trial of immediate repair versus surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:745–752. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prall AK, Longo GM, Mayhan WG, et al. Doxycycline in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms and in mice: Comparison of serum levels and effect on aneurysm growth in mice. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:923–929. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendeck MP, Conte M, Zhang M, et al. Doxycycline modulates smooth muscle cell growth, migration, and matrix remodeling after arterial injury. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1089–1095. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64929-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huffman MD, Curci JA, Moore G, et al. Functional importance of connective tissue repair during the development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surgery. 2000;128:429–438. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson RW, Geraghty PJ, Lee JK. Abdominal aortic aneurysms: Basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Curr Probl Surg. 2002;39:110–230. doi: 10.1067/msg.2002.121421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki T, Kataoka H, Morimoto M, et al. Macrophage-derived matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 promote the progression of cerebral aneurysms in rats. Stroke. 2007;38:162–169. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000252129.18605.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMillan WD, Pearce WH. Increased plasma levels of metalloproteinase-9 are associated with abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:122–127. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70363-0. discussion 127–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365:1577–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson DJ, Robson P, Hew Y, et al. Decreased elastin synthesis in normal development and in long-term aortic organ and cell cultures is related to rapid and selective destabilization of mRNA for elastin. Circ Res. 1995;77:1107–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon MP, Faris B, Wolfe BL, et al. Aging effects on the elastin composition in the extracellular matrix of cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1985;21:674–680. doi: 10.1007/BF02620921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall AJ, Busse EF, McCarville DJ, et al. Aortic wall tension as a predictive factor for abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture: Improving the selection of patients for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:152–157. doi: 10.1007/s100169910027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorp DA. Biomechanics of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Biomech. 2007;40:1887–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mower WR, Baraff LJ, Sneyd J. Stress distributions in vascular aneurysms: Factors affecting risk of aneurysm rupture. J Surg Res. 1993;55:155–161. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1993.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW, Jr., et al. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms: Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1106–1117. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Propranolol for small abdominal aortic aneurysms: Results of a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:72–79. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.121308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimura K, Aoki H, Ikeda Y, et al. Regression of abdominal aortic aneurysm by inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Nat Med. 2005;11:1330–1338. doi: 10.1038/nm1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prinssen M, Buskens E, Blankensteijn JD. Quality of life endovascular and open AAA repair. Results of a randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robert L, Jacob MP, Fulop T. Elastin in blood vessels. Ciba Found Symp. 1995;192:286–299. doi: 10.1002/9780470514771.ch15. discussion 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bressan GM, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Fornieri C, et al. Relevance of aggregation properties of tropoelastin to the assembly and structure of elastic fibers. J Ultrastruct Mol Struct Res. 1986;94:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(86)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swee MH, Parks WC, Pierce RA. Developmental regulation of elastin production. Expression of tropoelastin pre-mRNA persists after down-regulation of steady-state mRNA levels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14899–14906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parks WC, Pierce RA, Lee KA, et al. Elastin. In: Bittar EE, editor. Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology. Greenwich, CT: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 133–181. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berk JL, Hatch CA, Morris SM, et al. Hypoxia suppresses elastin repair by rat lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L931–L936. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00037.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma AK, Lu G, Jester A, et al. Experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm formation is mediated by IL-17 and attenuated by mesenchymal stem cell treatment. Circulation. 2012;126:S38–S45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.083451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gacchina CE, Deb P, Barth JL, et al. Elastogenic inductability of smooth muscle cells from a rat model of late stage abdominal aortic aneurysms. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1699–1711. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cafueri G, Parodi F, Pistorio A, et al. Endothelial and smooth muscle cells from abdominal aortic aneurysm have increased oxidative stress and telomere attrition. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beamish JA, He P, Kottke-Marchant K, et al. Molecular regulation of contractile smooth muscle cell phenotype: Implications for vascular tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:467–491. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kothapalli CR, Taylor PM, Smolenski RT, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 and hyaluronan oligomers synergistically enhance elastin matrix regeneration by vascular smooth muscle cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:501–511. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gacchina C, Brothers T, Ramamurthi A. Evaluating smooth muscle cells from CaCl2-induced rat aortal expansions as a surrogate culture model for study of elastogenic induction of human aneurysmal cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1945–1958. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mestries P, Alexakis C, Papy-Garcia D, et al. Specific RGTA increases collagen V expression by cultured aortic smooth muscle cells via activation and protection of transforming growth factor-beta1. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai J, Michineau S, Franck G, et al. Long term stabilization of expanding aortic aneurysms by a short course of cyclosporine A through transforming growth factor-beta induction. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai J, Losy F, Guinault AM, et al. Overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta1 stabilizes already-formed aortic aneurysms: A first approach to induction of functional healing by endovascular gene therapy. Circulation. 2005;112:1008–1015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribourtout E, Desfaits AC, Salazkin I, et al. Ex vivo gene therapy with adenovirus-mediated transforming growth factor beta1 expression for endovascular treatment of aneurysm: Results in a canine bilateral aneurysm model. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:576–583. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boon RA, Dimmeler S. MicroRNAs and aneurysm formation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2011;21:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maegdefessel L, Azuma J, Toh R, et al. Inhibition of microRNA-29b reduces murine abdominal aortic aneurysm development. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:497–506. doi: 10.1172/JCI61598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franco C, Ho B, Mulholland D, et al. Doxycycline alters vascular smooth muscle cell adhesion, migration, and reorganization of fibrillar collagen matrices. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1697–1709. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allaire E, Muscatelli-Groux B, Guinault AM, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell endovascular therapy stabilizes already developed aneurysms in a model of aortic injury elicited by inflammation and proteolysis. Ann Surg. 2004;239:417–427. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000114131.79899.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leeper NJ, Hunter AL, Cooke JP. Stem cell therapy for vascular regeneration: Adult, embryonic, and induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2010;122:517–526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.881441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marra KG, Brayfield CA, Rubin JP. Adipose stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;702:261–268. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-960-4_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu JY, Swartz DD, Peng HF, et al. Functional tissue-engineered blood vessels from bone marrow progenitor cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kane NM, Xiao Q, Baker AH, et al. Pluripotent stem cell differentiation into vascular cells: A novel technology with promises for vascular re(generation) Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129:29–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bifari F, Pacelli L, Krampera M. Immunological properties of embryonic and adult stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2010;2:50–60. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v2.i3.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karabekian Z, Posnack NG, Sarvazyan N. Immunological barriers to stem-cell based cardiac repair. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:315–325. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9202-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abraham S, Riggs MJ, Nelson K, et al. Characterization of human fibroblast-derived extracellular matrix components for human pluripotent stem cell propagation. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4622–4633. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugii S, Kida Y, Berggren WT, et al. Feeder-dependent and feeder-independent iPS cell derivation from human and mouse adipose stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:346–358. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee TH, Song SH, Kim KL, et al. Functional recapitulation of smooth muscle cells via induced pluripotent stem cells from human aortic smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2010;106:120–128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie CQ, Huang H, Wei S, et al. A comparison of murine smooth muscle cells generated from embryonic versus induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:741–748. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang MY, Kim D, Kim CH, et al. Direct reprogramming of rat neural precursor cells and fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abraham S, Eroshenko N, Rao RR. Role of bioinspired polymers in determination of pluripotent stem cell fate. Regen Med. 2009;4:561–578. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu J, Du KT, Fang Q, et al. The use of human mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in RGD modified alginate microspheres in the repair of myocardial infarction in the rat. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7012–7020. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L, Tredget EE, Wu PY, et al. Paracrine factors of mesenchymal stem cells recruit macrophages and endothelial lineage cells and enhance wound healing. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conn KJ, Rich CB, Jensen DE, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I regulates transcription of the elastin gene through a putative retinoblastoma control element. A role for Sp3 acting as a repressor of elastin gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28853–28860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rich CB, Fontanilla MR, Nugent M, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor decreases elastin gene transcription through an AP1/cAMP-response element hybrid site in the distal promoter. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33433–33439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuang PP, Zhang XH, Rich CB, et al. Activation of elastin transcription by transforming growth factor-beta in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L944–L952. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00184.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kielty CM. Elastic fibres in health and disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2006;8:1–23. doi: 10.1017/S146239940600007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bashur CA, Venkataraman L, Ramamurthi A. Tissue engineering and regenerative strategies to replicate biocomplexity of vascular elastic matrix assembly. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:203–217. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boucher J, Gridley T, Liaw L. Molecular pathways of notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Front Physiol. 2012;3:81. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salazar KD, Lankford SM, Brody AR. Mesenchymal stem cells produce Wnt isoforms and TGF-beta1 that mediate proliferation and procollagen expression by lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1002–L1011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90347.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wada N, Wang B, Lin NH, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament fibroblasts. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:438–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xie SZ, Fang NT, Liu S, et al. Differentiation of smooth muscle progenitor cells in peripheral blood and its application in tissue engineered blood vessels. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008;9:923–930. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ross JJ, Hong Z, Willenbring B, et al. Cytokine-induced differentiation of multipotent adult progenitor cells into functional smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3139–3149. doi: 10.1172/JCI28184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Popova AP, Bozyk PD, Goldsmith AM, et al. Autocrine production of TGF-beta1 promotes myofibroblastic differentiation of neonatal lung mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L735–L743. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00347.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghazanfari S, Tafazzoli-Shadpour M, Shokrgozar MA. Effects of cyclic stretch on proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation to smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;388:601–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seib FP, Prewitz M, Werner C, et al. Matrix elasticity regulates the secretory profile of human bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389:663–667. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turnbull IC, Hadri L, Rapti K, et al. Aortic implantation of mesenchymal stem cells after aneurysm injury in a porcine model. J Surg Res. 2011;170:e179–e188. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hashizume R, Yamawaki-Ogata A, Ueda Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate angiotensin II-induced aortic aneurysm growth in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1743–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Burks CA, Bundy K, Fotuhi P, et al. Characterization of 75:25 poly(l-lactide-co-epsilon-caprolactone) thin films for the endoluminal delivery of adipose-derived stem cells to abdominal aortic aneurysms. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2591–2600. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dobrin PB. Animal models of aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 1999;13:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s100169900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kang MN, Yoon HH, Seo YK, et al. Effect of mechanical stimulation on the differentiation of cord stem cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2012;53:149–159. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2011.619284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim BS, Nikolovski J, Bonadio J, et al. Engineered smooth muscle tissues: Regulating cell phenotype with the scaffold. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251:318–328. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deux JF, Dai J, Riviere C, et al. Aortic aneurysms in a rat model: In vivo MR imaging of endovascular cell therapy. Radiology. 2008;246:185–192. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461070032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Falanga V, Iwamoto S, Chartier M, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived cultured mesenchymal stem cells delivered in a fibrin spray accelerate healing in murine and human cutaneous wounds. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1299–1312. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin G, Wang G, Banie L, et al. Treatment of stress urinary incontinence with adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:88–95. doi: 10.3109/14653240903350265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]