Abstract

Objective To investigate whether an intervention to improve treatment of depression in older adults in primary care modified the increased risk of death associated with depression.

Design Long term follow-up of multi-site practice randomized controlled trial (PROSPECT—Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial).

Setting 20 primary care practices in New York City, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh, USA, randomized to intervention or usual care.

Participants 1226 participants identified between May 1999 and August 2001 through a two stage, age stratified (60-74; ≥75 years) depression screening of randomly sampled patients; enrollment included patients who screened positive and a random sample of patients who screened negative.

Intervention For two years, a depression care manager worked with primary care physicians in intervention practices to provide algorithm based care for depression, offering psychotherapy, increasing antidepressant dose if indicated, and monitoring symptoms, adverse effects of drugs, and adherence to treatment. This paper reports the long term follow-up.

Main outcome measure Mortality risk based on a median follow-up of 98 (range 0.8-116.4) months through 2008.

Results In baseline clinical interviews, 396 people were classified as having major depression, 203 had clinically significant minor depression, and 627 did not meet criteria for depression. At follow-up, 405 patients had died. Patients with major depression in usual care were more likely to die than were those without depression (hazard ratio 1.90, 95% confidence interval 1.57 to 2.31). In contrast, patients with major depression in intervention practices were at no greater risk than were people without depression (hazard ratio 1.09, 0.83 to 1.44). Patients with major depression in intervention practices, relative to usual care, were 24% less likely to have died (hazard ratio 0.76, 0.57 to 1.00; P=0.05). Preliminary data on cause of death are provided. No significant effect on mortality was found for minor depression.

Conclusions Older adults with major depression in practices provided with additional resources to intensively manage depression had a mortality risk lower than that observed in usual care and similar to older adults without depression.

Trial registration Clinical trials NCT00000367.

Introduction

Prospective studies have consistently shown an association between depression and increased mortality in older adults.1 2 The biological, social, psychological, and behavioral mechanisms that mediate the effect of depression on mortality have only recently begun to be elucidated.3 4 A strong association exists between depression in late life and factors that increase mortality risk, such as poor adherence to medical treatment and self care for diabetes and cardiovascular disease,5 health behaviors such as smoking and lack of physical activity,6 cognitive impairment,7 and disability.8 Investigators seeking to understand the biological mechanisms linking depression and medical conditions have drawn attention to cardiovascular, immunologic, inflammatory, metabolic, and neuroendocrine pathways.3 4

Randomized trials testing models of service delivery have shown that treatment of depression in later life in primary care settings can lead to remission of major depression, reduced symptoms of depression, improved quality of life, and a reduction in functional impairment. For example, Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT), a collaborative care program that involved a nurse or psychologist in the primary care office to support management by the primary care physician, was associated with improvements in depressive symptoms, functioning, and quality of life.9 10 Katon and colleagues reported that patients with depression and poorly controlled diabetes or cardiovascular disease in practices with collaborative care managed by a medically supervised nurse had greater improvement in glycated hemoglobin, lipids, blood pressure, and depression, as well as better quality of life, compared with patients in usual care.11 Despite plausible mechanisms linking depression and excess mortality in the context of medical illness, no randomized trials have reported whether improved management of depression is associated with reduced mortality risk.

In the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT), 20 primary care practices were randomized to an intervention consisting of a depression care manager working with primary care physicians to provide algorithm based care or to usual care. Among older adults with major depression, the intervention was associated with improvement in depressive symptoms, remission, and suicidal ideation.12 Specifically, a significantly larger proportion of intervention patients with major depression responded to treatment, defined as a 50% or greater decrease in symptoms (for example, 42.7% v 29.1% at four months). Remission, defined as achieving reduction of symptoms below a predetermined threshold, was more common among patients with major depression in intervention practices (for example, 40.0% v 22.5% at four months). Rates of suicidal ideation declined faster in intervention patients (from 29.4% to 16.5%) than with usual care (from 20.1% to 17.1%). The beneficial effects on remission of depression persisted at 24 months, with 45.4% of patients with major depression in intervention practices in remission (compared with 31.5% in usual care).13

In this report, we focus on mortality after long term follow-up, and for clinical interest we provide preliminary data on cause of death. Our strategy was to assess whether the increased mortality risk among patients with depression can be reduced to the risk of patients who did not meet criteria for depression. In contrast to a typical randomized clinical trial, we also followed patients who did not meet criteria for depression, providing both a comparison to assess the effect of depression on mortality risk and a benchmark for gauging the influence of unmeasured characteristics of practice such as the interest and skill of the primary care physician, quality of care, and case mix of patients in the practice.

Methods

Study sample

PROSPECT was conducted in 20 primary care practices located in greater New York City, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh from May 1999 to August 2001. After pairing by urban location, academic affiliation, size, and population type, practices were randomized by coin flip to the intervention condition or to usual care (cluster randomization by practice). Patients were recruited from an age stratified (60-74, ≥75 years) random sample of people with upcoming appointments. Research associates confirmed eligibility (age ≥60 years, mini-mental state examination score >17,14 English speaking) of consenting patients and screened them for depression with the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CES-D).15 All patients with a CES-D score above 20 were invited to enroll, as was a 5% sample with lower scores. Research associates met patients at the practice, obtained signed informed consent, and administered a baseline interview.16

Assessment of depression

Major depression was diagnosed on the basis of standard criteria contained in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). Clinically significant minor depression was defined by DSM-IV criteria for minor depression modified by requiring four depressive symptoms, Hamilton depression rating scale score of 10 or more, and duration of at least four weeks. We did a structured clinical interview for axis I DSM-IV disorders (SCID) assessment of all participants.17

Assessment of patients’ characteristics

We obtained baseline information on age, sex, marital status, self reported ethnicity, educational attainment, and smoking based on tobacco use within six months. Patients self reported medical conditions.18 The 24 item Hamilton depression rating scale measured severity of depression,19 and the scale for suicidal ideation indicated the presence of suicidal ideation.20

Usual care and intervention conditions

Practices randomized to usual care received educational sessions for primary care physicians and notification of the depression status of patients. Physicians received no specific recommendations regarding individual patients (except for psychiatric emergencies). Practices randomized to the intervention condition received educational sessions for primary care physicians, education of patients’ families, and a depression care manager who worked within the practice. The care manager worked with the primary care physician to recommend treatment according to standard guidelines. Care managers had psychiatric back-up including on-demand consultation, weekly supervision by psychiatrist investigators, and monthly interpersonal therapy cross site supervision. The 15 care managers included social workers, nurses, and psychologists who interacted with patients in person or by telephone at scheduled intervals and as necessary. Care managers monitored symptoms, adverse effects of drugs, and adherence to treatment.

The PROSPECT algorithm provided guidelines to care managers for target and maximum daily doses of antidepressants.21 After six weeks, the target dosage was maintained if the patient showed a significant improvement (>50% reduction in Hamilton depression rating scale score) but was increased if the improvement was partial (30-50% reduction in score). For patients who had not responded at 12 weeks, the care manager followed guidelines for switching antidepressants.21 Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression could be used alone or as an augmentation strategy depending on whether the patient tolerated the antidepressant and the presence or absence of a partial response. In both study arms, physicians were informed by letter if patients reported any suicidal ideation and were immediately informed when patients were identified to be at high risk of suicide, according to pre-specified guidelines. Other sources detail the PROSPECT treatment algorithm and implementation, including the role of the care manager,22 the strategy for drug treatment,21 management of suicidal ideation,23 24 and types and proportions of treatment received over time by patients in practices randomized to the intervention condition or to usual care.12 25

Ascertainment of vital status

Vital status was based on follow-up of participants through the National Center for Health Statistics national death index (NDI Plus).26 Each participant gave written consent, including permission to obtain information from death certificates.

Analysis strategy

We compared baseline characteristics of patients across baseline depression status (major depression or minor depression versus no depression) stratified by groups defined by practice randomization assignment (intervention condition or usual care), by using linear and logistic regression with random effects to account for clustering of patients by practice. Our primary strategy was to compare people with depression and people without depression within intervention strata, followed by comparison of people with depression across intervention strata. On the basis of the age, sex, and ethnic composition of the PROSPECT sample and using mortality rates for the US population, we estimated that 300 to 500 deaths would occur among the 1226 patients, a number of deaths large enough to detect a clinically meaningful signal accounting for the study design.

We modeled survival time with Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusting standard errors for within practice clustering.27 Final models included terms for characteristics identified by their association (P<0.05) with time to death: baseline age, sex, education, marital status, smoking status, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, cognition, and suicidal ideation. We assessed the proportional hazard assumption by including time dependent terms in the unadjusted model and measuring the global effect.28 We used SAS version 9.1 and Stata version 12.0 for these analyses. We plotted survival time by using the method of Kaplan and Meier.29 We set α at 0.05 to denote statistical significance, recognizing that tests of statistical significance are approximations that serve as aids to interpretation and inference.

Results

Characteristics of sample

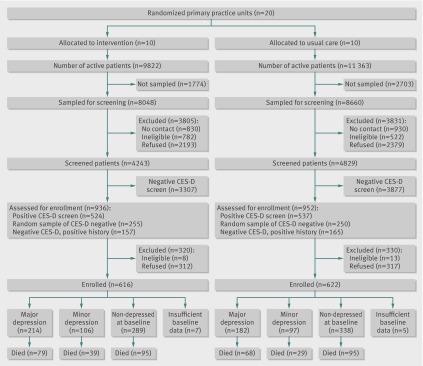

Figure 1 shows the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. Table 1 compares baseline characteristics between patients who met criteria for major depression or minor depression and patients without depression, according to the intervention status of practices. Compared with patients without depression, those in both arms with major depression were more likely to smoke, to report heart disease or gastrointestinal disease at baseline, to have higher depression scores, and to report suicidal ideation. Patients with minor depression were comparable to people without depression, with the exception of higher depression scores and, in the intervention condition, being more likely to report smoking, gastrointestinal disease, and suicidal ideation. At baseline, the 37 smokers with major depression in intervention practices reported smoking an average of 16.9 (SD 12.6; median 18, interquartile range 10-20) cigarettes a day. In usual care, 41 smokers with major depression reported smoking an average of 16.5 (SD 14.4; median 14, interquartile range 7-20) cigarettes a day.

Fig 1 Flow chart for mortality follow-up of PROSPECT patients. CES-D=Centers for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to baseline depression status and practice randomization group assignment. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise. Data from PROSPECT (1999-2008)

| Intervention practices | Usual care practices | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major depression (n=214) | Minor depression (n=106) | No depression (n=289) | Major depression (n=182) | Minor depression (n=97) | No depression (n=338) | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||

| Mean (SD) age, years | 70 (8.0) | 71 (7.5) | 72 (7.8) | 69 (7.5)*** | 72 (8.7) | 72 (7.7) | |

| Women | 149 (70) | 72 (68) | 194 (67) | 136 (75) | 72 (74) | 234 (69) | |

| Ethnic minority† | 63 (29) | 30 (28) | 82 (28) | 71 (39) | 32 (33) | 124 (37) | |

| Mean (SD) education, years | 12 (3.1)** | 13 (3.4) | 13 (3.8) | 13 (3.4) | 13 (3.1) | 13 (3.8) | |

| Married | 77 (36)* | 39 (37) | 124 (43) | 63 (35) | 41 (42) | 127 (38) | |

| Habits | |||||||

| Current smoker | 37 (17)* | 23 (22)** | 32 (11) | 41 (23)** | 12 (12) | 40 (12) | |

| Medical conditions | |||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 110 (51)*** | 40 (38) | 97 (34) | 83 (46)** | 32 (33) | 113 (33) | |

| Stroke | 58 (27)*** | 20 (19) | 33 (11) | 35 (19) | 20 (22) | 46 (14) | |

| Diabetes | 50 (23) | 20 (19) | 58 (20) | 39 (21) | 14 (14) | 79 (23) | |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 58 (27)** | 30 (28)** | 46 (16) | 57 (31)** | 17 (18) | 68 (20) | |

| Cancer | 27 (13) | 14 (13) | 32 (11) | 34 (19) | 14 (14) | 44 (13) | |

| Respiratory diseases | 28 (13) | 14 (13) | 36 (12) | 31 (17)* | 12 (12) | 35 (10) | |

| Cognition and depression‡ | |||||||

| MMSE score, mean (SD) | 27 (3.2) | 28 (2.1) | 27 (3.2) | 27 (2.6) | 28 (2.2) | 27 (3.4) | |

| HDRS score, mean (SD) | 21 (5.7)*** | 14 (3.2)*** | 5 (3.9) | 20 (5.5)*** | 13 (3.7)*** | 5 (4.4) | |

| Suicidal ideation (SSI>0) | 79 (37)*** | 15 (14)* | 19 (7) | 48 (26)*** | 8 (8) | 28 (8) | |

HDRS=Hamilton depression rating scale; MMSE=mini-mental state examination; SSI=scale for suicidal ideation.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 for comparison between patients with major or minor depression and patients with no depression within intervention and usual care practices; all other comparisons with non-depressed group were not significant (P>0.05).

†Minority defined as ethnicities other than non-Hispanic white (total n=404; Hispanic n=46, non-Hispanic black n=333, Asian n=9, other non-Hispanic n=14, and unknown n=2).

‡Major depressive disorder defined as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) major depression in contrast to clinically significant minor depression (defined as four DSM-IV symptom groups, HDRS score ≥10, and four week duration); range of scores for MMSE is 0 to 30 (inclusion criteria limited range to 18-30), with high scores indicating less cognitive impairment; HDRS range is 0 to 76, with high scores indicating greater depressive symptoms; SSI range is 0 to 38, with high scores indicating greater suicidal ideation.

Mortality risk attributable to depression in intervention versus usual care

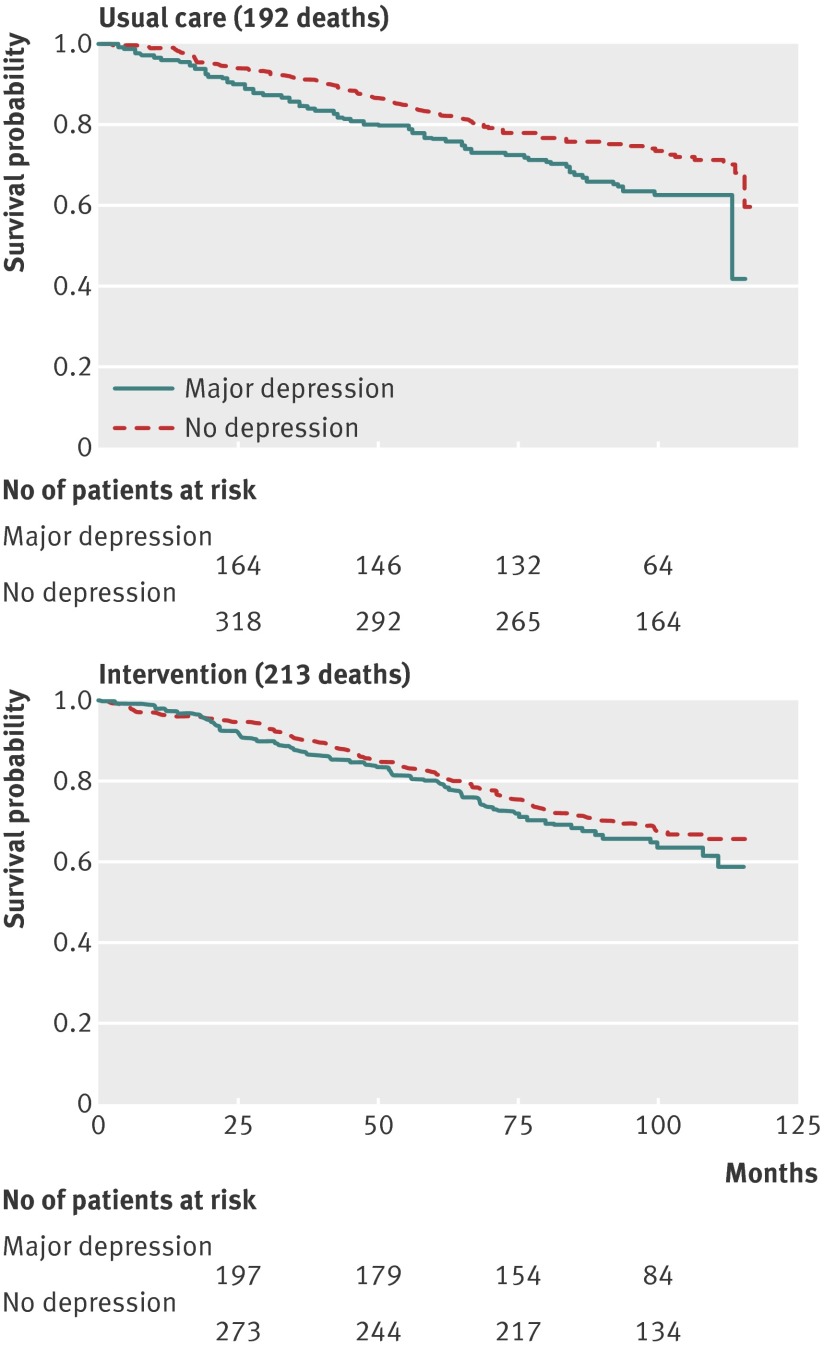

The median length of follow-up in ascertainment of vital status was 98 (range 0.8-116.4) months, during which 405 people died—215 depressed patients and 190 non-depressed patients. Figure 2 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for baseline depression status according to intervention condition. Table 2 reports final Cox proportional hazards models and number of deaths in terms of depression stratified by intervention condition versus usual care. We observed no significant departure from the proportional hazards assumption (P=0.10; χ2=4.57, df=2). The hazard ratio for patients with major depression compared with patients without depression in usual care was 1.90 (95% confidence interval 1.57 to 2.31). In contrast, for patients with major depression compared with non-depressed patients in the intervention condition, the hazard ratio was 1.09 (0.83 to 1.44). We found no similar relation for clinically significant minor depression. Thus, patients with major depression in usual care practices were twice as likely to die as patients without depression, whereas the risk for patients with major depression in intervention practices was similar to that for people without depression.

Fig 2 Survival probability among people with no depression or major depression in practices randomized to usual care (top panel) or to intervention (bottom panel). Data from PROSPECT (1999-2008)

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios and number of deaths according to depression status at baseline stratified by intervention condition. Data from PROSPECT (1999-2008)

| Patients | Intervention practices | Usual care practices | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of deaths | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | No of deaths | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

| All depressed patients | 1.12 (0.88 to 1.42) | 1.67 (1.37 to 2.02) | |||

| Major depressive disorder | 79 | 1.09 (0.83 to 1.44) | 68 | 1.90 (1.57 to 2.31) | |

| Clinically significant minor depression | 39 | 1.19 (0.88 to 1.60) | 29 | 1.32 (0.92 to 1.90) | |

| Non-depressed | 95 | 1.00 | 95 | 1.00 | |

Hazard ratios are from Cox proportional hazards models. Adjusted models include terms for baseline age, sex, education, marital status, smoking, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, cognition, and suicidal ideation.

Mortality risk of major depression in intervention versus usual care

When we compared patients with major depression in the intervention condition with patients with major depression in usual care, the hazard ratio in the adjusted model was 0.76 (0.57 to 1.00), indicating that patients with major depression were 24% less likely to have died over follow-up if they had received the PROSPECT intervention. The corresponding hazard ratio of 1.18 (0.77 to 1.81) for people with minor depression was not statistically significant.

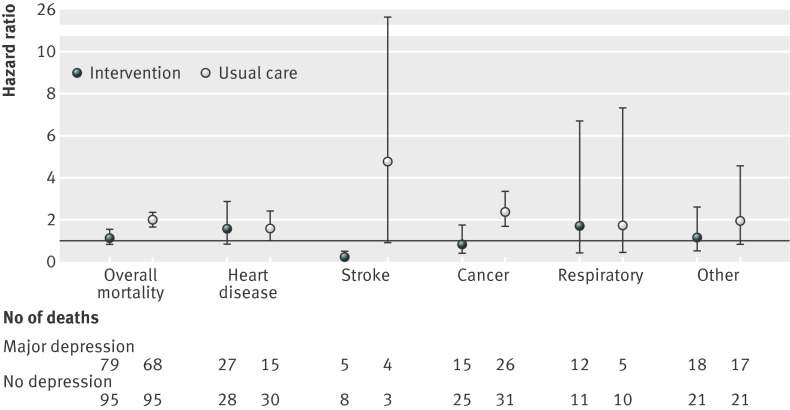

Mortality according to cause of death

Figure 3 illustrates the adjusted hazard ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) for specific causes of death according to practice randomization assignment for patients with major depression. Among people with major depression, compared with people without depression, the risk of death from cancer was significantly higher in usual care. We found no statistically significant hazard ratios for minor depression (data not shown). Cancers causing death among patients with major depression in usual care (n=26) were respiratory in 10 patients, digestive in five, hematopoietic in four, female genital in two, and unspecified in two, with one each of breast, male genital, and urinary tract origin. In intervention practices, cancers causing deaths among patients with major depression (n=15) were respiratory in nine patients and digestive in two, with one each of breast, male genital, hematopoietic, and unspecified origin. Among 37 people with major depression in intervention practices who reported smoking at baseline, seven died of cancer (six were respiratory cancer); among 41 patients with major depression in usual care who reported smoking at baseline, six died of cancer (five were respiratory cancer). Among 32 people in intervention practices who did not meet criteria for major or minor depression and who reported smoking at baseline, seven died of cancer (three were respiratory); among 40 smokers in usual care without depression, nine died of cancer (four were respiratory).

Fig 3 Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for specific causes of death comparing major depression with no depression within intervention or usual care practices. Data from PROSPECT (1999-2008). Hazard ratios are from Cox proportional hazards models. Adjusted models included terms for baseline age, sex, education, marital status, smoking, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, cognition, and suicidal ideation

Discussion

Our study provides the first evidence from a randomized clinical trial that treatment of major depression can extend life. The biological, social, psychological, and behavioral links between depression and mortality provided strong rationale to examine whether improved management of depression can decrease mortality in older adults. Older primary care patients with major depression in practices provided with additional resources for algorithm based management of depression were at no greater risk of death after up to 116 months of follow-up (median 98 months) than were patients with no depression. In contrast, patients with major depression in practices providing usual care were twice as likely to die compared with patients with no depression, consistent with the doubling of risk reported in many studies.1 2 Patients with major depression in intervention practices were 24% less likely to die than were patients with major depression in usual care. We found no similar effect of care management on mortality for clinically significant minor depression.

Possible explanations for findings

The PROSPECT intervention reduced hopelessness and depression, which are known to increase mortality risk.12 Patients in the intervention condition had increased exposure to antidepressants and psychotherapy compared with patients in usual care. For two years, a depression care manager partnered with primary care physicians to provide algorithm based care for depression, offering psychotherapy, increasing antidepressant dose if indicated, and monitoring symptoms, adverse effects of drugs, and adherence to treatment. Alexopoulos and colleagues reported that the beneficial effects of the practice based intervention on remission of depression persisted at 24 months (in contrast to patients in usual care, who did worse over time).13 The provision of resources to carry on the intervention for two years is important because major depression is likely to recur in a considerable proportion of older adults within two years of treatment.30

Wells, Sherbourne, and colleagues provide evidence that an intervention implemented in primary care could establish patterns of practice and expectations of patients and providers, with long term consequences.31 32 In “Partners In Care,” attitudes of minorities changed toward increased acceptance of treatment,31 and fewer negative life events at five years mediated long term improved psychological wellbeing at nine years.32 In PROSPECT, the intervention provided patients and physicians alike with experience in managing depression in a less stigmatizing environment. Clinicians may have become more sensitive to symptoms of depression and more skilled in managing depression, and patients who are successfully treated may be more aware of evolving symptoms of depression and be primed to accept treatment when depression recurs.

Comparison with other studies

PROSPECT and other studies show that treatment of major depression in primary care reduces symptoms of depression, induces remission, improves quality of life, and reduces functional impairment,9 10 11 12 13 33 34 35 36 37 but they have not reported the effect of the intervention on mortality risk. Our study contributes the finding that practice based care management of major depression reduces mortality risk after nine years and six months of follow-up. In a report of 231 community dwelling older adults in Italy with depressive symptoms, self reported use of psychoactive drugs was associated with reduced five year mortality risk,38 but the study is difficult to interpret because the investigation did not include clinical assessments of depression, did not randomize patients to treatment, and relied on self report of use of drugs. Our findings deserve attention because practices were randomized to a practice based intervention, in contrast to observational studies without randomization. Patients without depression were included in the follow-up, providing a strong comparison group exposed to the same practices.

Several intervention studies in specialty medical settings have examined mortality as an outcome, often linked with hospital admission or myocardial infarction into a single combined outcome. ENRICHD (Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease) did not show any benefit on mortality risk over a 40 month follow-up interval.39 40 SADHART (Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial) reported a statistically non-significant beneficial trend for combined cardiovascular outcomes that included death at 24 weeks.41 MIND-IT (Myocardial INfarction and Depression—Intervention Trial) reported only seven deaths after 18 months of follow-up.42 In ENRICHD, taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor was associated with reduction in the risk of all cause mortality,43 as was participation in group plus individual therapy,44 but these secondary analyses ignored randomization. Interventions that do not specifically treat depression (such as preventive medical services,45 exercise for heart failure,46 or reduction of cardiovascular risk factors for diabetes47) do not affect mortality.

Causes of death

For clinical interest, we provided exploratory information about causes of death, recognizing that even among observational studies few have reported specific causes of death among people with depression. Our study was designed to focus on all cause mortality and was the only study from an intervention trial in primary care to report on cause of death in association with depression.48 Among people with major depression, only the mortality rate from cancer was significantly higher in usual care. This pattern must be interpreted with care. Firstly, although ascertainment of vital status may be highly accurate, the potential for misclassification for a single cause of death derived from death certificates is likely to be substantial. Secondly, we cannot disentangle the extent to which the excess mortality risk for cancer is related to the intervention or simply reflects the relation of medical comorbidity to major depression among the patients in particular practices. Thirdly, the examination of causes of death was post hoc. We found no strong differences across relevant patient groups in reported smoking behaviors at baseline or in rates of deaths from cancer in smokers; however, we were limited in our ability to assess smoking status over time. Nevertheless, the effect of the intervention on overall mortality is consistent with the association of depression with poor health outcomes through pathways that cut across several medical conditions.1 2 3 4 The link is plausible through reduction of pro-inflammatory factors and behaviors known to increase risk.49

Strengths and limitations of study

We used several strategies to control for factors that might otherwise have led to erroneous conclusions about the relation of the intervention to reduction in mortality risk. Firstly, before randomization, practices were matched on urban location, academic affiliation, size, and population type. Secondly, estimates of risk and associated confidence bounds were adjusted for clustering by practice and for patient level characteristics associated with mortality. Thirdly, comparing the mortality of patients with depression with that of non-depressed patients from the same sets of practices mitigates the influence of unmeasured characteristics of practices such as the case mix of patients in the practice or the non-specific effects of introducing a person into the practice.

Misclassification of depression or vital status could also mislead. Depression and other mental health problems may be underestimated in older people because many of them minimize reports of sadness or anhedonia or because symptoms of depression are attributed to physical health causes.50 51 An advantage of PROSPECT was the use of sensitive instruments (that is, clinical interview for axis I DSM-IV disorders and Hamilton depression rating scale, which are accepted semi-structured clinical interviews) by trained research associates conducting a thorough evaluation of the diagnosis and severity of depression. Our experience and that of others suggests that misclassification of vital status would be minimal with no loss to follow-up. In the nine year follow-up of the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area study,52 national death index data confirmed 99.4% of known deaths and correctly classified all survivors. Similarly, the overall sensitivity of the national death index for ascertainment of vital status was 98% in the Nurses’ Health Study and has generally been well over 90% in most studies.53 54

Policy implications

Medical comorbidity and depression are so closely linked through biological, social, psychological, and behavioral mediators that treatment of depression probably affects multiple pathways, interrupting the link between depression and excess mortality.3 4 Primary healthcare occupies a strategic position in the evaluation, treatment, and prevention of depression in late life. Our findings underscore the value of providing resources to primary care practices to integrate depression care management into chronic care management. Policy changes in the financing and integration of primary care and mental healthcare being considered worldwide take on new urgency with the demonstration that depression care management saves lives. In an era of healthcare reform and cost consciousness, the global challenge is to develop clinically effective models of service delivery that are acceptable to older patients and their families, culturally relevant, and economically sustainable.

What is already known on this topic

Prospective studies have consistently shown a relation between depression and increased mortality in older adults

No randomized trials have reported that a depression management program can decrease risk

What this study adds

A 24% lower mortality risk was seen after a median of 98 months among patients with major depression in practices provided with resources for depression care management compared with usual care

The decline in mortality was across all causes of death, but with fewer deaths from cancer among people with major depression in intervention practices

A depression care manager working with primary care physicians to provide algorithm based care for depression can mitigate the detrimental effects of depression on mortality

Contributors: JJG, HRB, and PJR did the literature searches. KHM and JZ created the figures. JJG, MLB, and CFR were responsible for the overall design and conduct of the study. KHM and JZ were responsible for data management and did the analyses with input from JJG, MLB, CFR, HRB, and PJR. All authors were involved in interpretation of the findings and in preparation of the manuscript. All approved the final submitted version. JJG, MLB, and CFR are the guarantors.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH065539). JJG, KHM, and HRB were supported by NIMH awards K24 MH070407, K01MH073903, and K23 MH67671. MLB and PJR were supported by P30 MH085943, and CFR was supported by P30 MH090333 from NIMH. JZ was supported by NIMH award T32 MH065218. PROSPECT was a collaborative research study funded by the NIMH. The three groups included the Advanced Centers for Intervention and Services Research of Cornell University (PROSPECT Coordinating Center; principal investigator: George S Alexopoulos; co-principal investigators: MLB and Herbert C Schulberg; R01 MH59366, P30 MH68638); University of Pennsylvania (principal investigator Ira Katz; co-principal investigators Thomas Ten Have and Gregory K Brown; R01 MH59380, P30 MH52129); and University of Pittsburgh (principal investigator CFR; co-principal investigator Benoit H Mulsant; R01 MH59381, P30 MH52247). Additional small grants came from Forest Laboratories and the John D Hartford Foundation. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in data collection or management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. All the authors had full access to all the data.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work other than those listed under funding; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study received approval from the institutional review boards at all collaborating universities and independent review at the National Center for Health Statistics. Each participant gave written consent, including permission to obtain death certificate information.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f2570

References

- 1.Cuijpers P, Smit F. Excess mortality in depression: a meta-analysis of community studies. J Affect Disord 2002;72:227-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz R, Drayer RA, Rollman BL. Depression as a risk factor for non-suicide mortality in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry 2002;52:205-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mezuk B, Gallo JJ. Depression and medical illness in late life: race, resources, and stress. In: Lavretsky H, Sajatovic M, Reynolds CF, eds. Depression in late life. Oxford University Press, 2013:270-94.

- 4.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, Golden RN, Gorman JM, Krishnan KR, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:175-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3278-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Skala JA. Depression and smoking in coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 2005;67(suppl 1):S42-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kalayam B, Kakuma T, Gabrielle, et al. Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:285-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Harvard University Press, 1996.

- 9.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2836-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunkeler E, Katon W, Tang L, Williams JW Jr, Kroenke K, Lin EH, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomized trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ 2006;332:259-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2611-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF 3rd, Katz IR, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1081-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF 3rd, Bruce ML, Bruce ML, Katz IR, Raue PJ, Mulsant B, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:882-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas 1977;1:385-401. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raue PJ, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Klimstra S, Mulsant BH, Gallo JJ. The systematic assessment of depressed elderly primary care patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for axis I DSM-IV disorders (SCID). American Psychiatric Association Press, 1995.

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987;40:373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 1960;23:56-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck A, Brown G, Steer R. Psychometric characteristics of the scale for suicide: ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther 1997;35:1039-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF 3rd, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D, et al. Pharmacological treatment of depression in older primary care patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:585-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulberg HC, Bryce C, Chism K, Mulsant BH, Rollman B, Bruce M, et al. Managing late-life depression in primary care practice: a case study of the health specialist’s role. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:577-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown GK, Bruce ML, Pearson JL. High-risk management guidelines for elderly suicidal patients in primary care settings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:593-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds CF 3rd, Degenholtz H, Parker LS, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Post E, et al. Treatment as usual (TAU) control practices in the PROSPECT Study: managing the interaction and tension between research design and ethics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulberg HC, Post EP, Raue PJ, Have TT, Miller M, Bruce ML. Treating late-life depression with interpersonal psychotherapy in the primary care sector. Int J Geriatr Psych 2007;22:106-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doody MM, Hayes HM, Bilgrad R. Comparability of national death index plus and standard procedures for determining causes of death in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol 2001;11:46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee E, Wei L, Amato D. Cox-type regression analysis for large numbers of small groups of correlated failure time observations. In: Survival analysis: state of the art. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1992.

- 28.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. Chapman & Hall, 1994.

- 29.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958;53:457-81. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds CF 3rd, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Frank E, Miller MD, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells KB, Tang L, Miranda J, Benjamin B, Duan N, Sherbourne CD. The effects of quality improvement for depression in primary care at nine years: results from a randomized, controlled group-level trial. Health Serv Res 2008;43:1952-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherbourne C, Edelen MO, Zhou A, Bird C, Duan N, Wells K. How a therapy-based quality improvement intervention for depression affected life events and psychological well-being over time: a 9-year longitudinal analysis. Med Care 2008;46:78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:28-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Williams JW Jr, Schulberg HC, Bruce ML, Lee PW, et al. Re-engineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2004;329:602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Simon G, Ludman E, Russo J, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:1042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, Ware JH, Miles KM, Areán PA, et al. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1455-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:2086-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozzini R, Trabucchi M. Depressive symptoms, their management, and mortality in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:989-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease patients (ENRICHD) randomized trial. JAMA 2003;289:3106-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, Youngblood M, Veith RC, Burg MM, et al. Depression and late mortality after myocardial infarction in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study. Psychosom Med 2004;66:466-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT Jr, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA 2002;288:701-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Melle JP, de Jonge P, Honig A, Schene AH, Kuyper AM, Crijns HJ, et al. Effects of antidepressant treatment following myocardial infarction. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor CB, Youngblood ME, Catellier D, Veith RC, Carney RM, Burg MM, et al. Effects of antidepressant medication on morbidity and mortality in depressed patients after myocardial infarction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saab PG, Bang H, Williams RB, Powell LH, Schneiderman N, Thoresen C, et al. The impact of cognitive behavioral group training on event-free survival in patients with myocardial infarction: the ENRICHD experience. J Psychosom Res 2009;67:45-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unützer J, Patrick DL, Marmon T, Simon GE, Katon WJ. Depressive symptoms and mortality in a prospective study of 2,558 older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:521-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, O’Connor C, Keteyian S, Landzberg J, Howlett J, et al. Effects of exercise training on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure: the HF-ACTION randomized trial. JAMA 2012;308:465-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan MD, O’Connor P, Feeney P, Hire D, Simmons DL, Raisch DW, et al. Depression predicts all-cause mortality: epidemiological evaluation from the ACCORD HRQL substudy. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1708-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Lin JY, Bruce ML. The effect on mortality of a practice-based depression intervention program for older adults in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:689-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Biobehavioral factors and cancer progression: physiological pathways and mechanisms. Psychosom Med 2011;73:724-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gallo JJ, Anthony JC, Muthén BO. Age differences in the symptoms of depression: a latent trait analysis. J Gerontol B-Psychol 1994;49:P251-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knauper B, Wittchen HU. Diagnosing major depression in the elderly: evidence for response bias in standardized diagnostic interviews? J Psychiatr Res 1994;28:147-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GP, Florio L, Hoff RA. Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:716-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the national death index and Equifax nationwide death search. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:1016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sathiakumar N, Delzell E, Abdalla O. Using the national death index to obtain underlying cause of death codes. J Occup Environ Med 1998;40:808-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]