ABSTRACT

Purpose: To explore decision-making processes currently used in allocating occupational and physical therapy services in home care for complex long-stay clients in Ontario. Method: An exploratory study using key-informant interviews and client vignettes was conducted with home-care decision makers (case managers and directors) from four home-care regions in Ontario. The interview data were analyzed using the framework analysis method. Results: The decision-making process for allocating therapy services has four stages: intake, assessment, referral to service provider, and reassessment. There are variations in the management processes deployed at each stage. The major variation is in the process of determining the volume of therapy services across home-care regions, primarily as a result of financial constraints affecting the home-care programme. Government funding methods and methods of information sharing also significantly affect home-care therapy allocation. Conclusion: Financial constraints in home care are the primary contextual factor affecting allocation of therapy services across home-care regions. Given the inflation of health care costs, new models of funding and service delivery need to be developed to ensure that the right person receives the right care before deteriorating and requiring more costly long-term care.

Key Words: decision making, home care, occupational therapy, resource allocation

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Explorer les mécanismes actuels de prise de décision en matière de répartition des services de physiothérapie et d'ergothérapie dans les soins à domicile pour les clients aux besoins complexes nécessitant des soins à domicile à long terme en Ontario. Méthode : Une étude exploratoire à l'aide d'entrevues auprès d'intervenants clés et de vignettes a été réalisée auprès des décideurs en matière de soins à domicile (gestionnaires de cas et personnel de direction) dans quatre régions de soins à domicile de l'Ontario. Les données des entrevues ont été analysées à l'aide d'une méthode dite de « l'analyse des structures ». Résultats : La prise de décision pour la répartition des services de thérapie comporte quatre étapes: admission, évaluation, acheminement vers le fournisseur de services et réévaluation. Certaines disparités dans les processus de gestion ont toutefois été observées à chacune des étapes. La principale variation se situait dans le processus visant à établir la quantité de services de thérapie dans les diverses régions, en raison principalement des contraintes financières touchant les programmes de soins à domicile. La méthode de financement du gouvernement et les modes de partage de l'information ont aussi des effets considérables sur la répartition des soins à domicile. Conclusion : Les contraintes financières des soins à domicile constituent le principal facteur contextuel affectant la répartition des services de thérapie dans les divers secteurs de soins à domicile. Compte tenu de l'inflation dans les coûts des soins de santé, de nouveaux modèles de financement et de prestation des services devront être créés afin de s'assurer que la bonne personne reçoit les bons soins avant que son état ne se détériore et qu'il ne nécessite des soins à long terme encore plus coûteux.

Mots clés : soins à domicile, répartition, ergothérapie, prise de décision

Hospital stays have grown increasingly shorter, with a corresponding increase in the use of post-acute services. The burden of care has shifted to community-based formal (i.e., home care) and informal (i.e., family caregiver) support services.1,2 In 2002, the Commission on the Future of Health Care argued that home care is the “next essential service.”3(p.171) Currently home care plays a key role in strategies for primary care, chronic disease management, and ageing at home across Canada.4 At any given time, approximately 900,000 Canadians are receiving home care, the majority of whom are seniors requiring long-term supportive care.4 Despite recent evidence of the feasibility and effectiveness of rehabilitation for older people in home-based settings,2,5 they do not always receive appropriate rehabilitation services.6–8 For example, Hirdes and colleagues9 found that 71.2% of older home-care clients assessed as having rehabilitation potential did not receive any type of rehabilitation.

In Ontario, 14 regional authorities known as Community Care Access Centres (CCACs) manage local home-care services. The CCACs are funded and legislated by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) and sign accountability agreements with the corresponding Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs). CCACs represent a single point of entry to long-term care (LTC), home care, and other community services. Case managers employed by the CCACs are responsible for assessing and developing service plans for home-care clients but do not provide rehabilitation services themselves;10 rehabilitation provider agencies bid for contracts with each CCAC separately. This model of service delivery, known as “managed competition,”11 allows direct competition between non-profit and for-profit agencies to ensure “the highest quality at the best price.”12(p.125) Some contextual factors hypothesized to negatively affect therapy service allocation in home care are an orientation toward serving medical needs rather than rehabilitation needs, financial constraints, lack of social awareness, knowledge barriers, and inefficient use of client outcomes.5

Hirdes and colleagues13 examined the distribution of physiotherapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) service allocation across Ontario by analyzing Resident Assessment Instrument–Home Care (RAI-HC) data linked with Ontario Home Care Administrative System (OHCAS) claims data and discovered a wide variation in the proportion of clients who received any PT or OT services across different CCACs. The factor most strongly related to receipt of rehabilitation services was recent hospitalization with referral to home care from the acute-care setting. At present, we have a very limited understanding of how rehabilitation services are allocated in home care. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to understand the decision-making process currently used to allocate PT and OT services in home care.

METHODS

Design

This qualitative study of decisions related to PT and OT service provision used key-informant interviews with the people responsible for deciding whether such services should be provided (home care case managers and directors) from a sample of home-care regions in Ontario with relatively low and relatively high provision of PT and OT home-care service. The study was approved by the Health Science Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto (Protocol Reference #25699).

Sampling

In consultation with analysts from the RAI collaborating centre at the University of Waterloo, we chose four CCACs to represent high and low volumes of referrals to rehabilitation service providers in urban and rural settings. Data sources were the 2006–2008 Ontario provincial home-care data holdings, which contain RAI-HC assessments linked to the Home Care Database (HCD) that records admission information, service utilization, and discharge information of home-care clients. Two CCACs below and two above the mean proportion of RAI-HC assessed clients with a PT or OT visit were sampled (one rural and one urban in each category, differentiated on the basis of clients' postal codes, where a 0 in the second position indicates a rural setting).

Research advisory

An advisory committee consisting of home-care decision makers (two case managers and two client service managers) was formed to act as decision-making partners to the researchers throughout the research process. Using their insights, we developed two clinical vignettes (see Appendix 1) representing potential clients who demonstrated high need and lower need for rehabilitation services.

Recruitment

Members of the advisory committee were asked to forward an e-mail invitation to all case managers and administrators working for the sample home-care regions. The invitation introduced the study and explained how to contact the first author to express interest in participating. A total of 10 case managers and 4 administrators participated in the study.

Data collection

Semi-structured telephone interviews with open-ended questions, each lasting approximately 1 hour, were conducted with all participants (see Appendix 2 for interview guide). Participants were first asked about the decision-making process for PT and OT services in general; the then interviewer asked targeted questions using two patient vignettes designed to represent higher-need and lower-need patients (see Appendix 1). Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Framework analysis, which is explicitly focused on generating policy- and practice-oriented findings,14 is best suited for studies centred on specific research questions, pre-selected samples of participants, and organizational imperatives;15 it is used primarily in health services research.16 The primary objective of this analytic approach is to understand the current state of an organization.15 Since our study aimed to explore the current process of therapy services allocation in the context of CCACs (an organizational imperative), using targeted objectives and a sample of home-care decision makers, we used framework analysis to analyze our interview data.

Framework analysis is a type of content analysis that “involves summarizing and classifying data within a thematic framework.”13(p.208) It requires understanding the interview data and applying thematic analysis, indexing (analyzing codes to generate themes), and charting (tabulating thematic codes by interview). Each interview was coded by two investigators, working independently; a third investigator was used to resolve discrepancies. Three qualitative researchers (one interviewer and two investigators) within the investigative team led the analysis of codes, and all investigators participated in the development of themes arising from the data.

RESULTS

Of the 14 participants, 5 were registered nurses, 5 social workers, 3 physiotherapists, and 1 occupational therapist; participants averaged 22.5 years' experience in their professions and 11.2 years' experience in a CCAC. Their responses indicate that the decision-making process follows several stages: intake, assessment by a case manager, and referral to the service provider if needed.

Intake

The intake process has three components: source of referral, eligibility for in-home services, and selection of clients.

Source of referral

Participants reported receiving referrals to their programme from multiple sources including physicians, allied health professionals, hospitals, services providers, families, and clients themselves. As one participant stated,

We might get a physician's referral … they might have identified some need for occupational therapy or physiotherapy. Therefore they will send me what's called a physician's referral and at that time I will contact my client, and/or family, whoever's making the decisions…. Then we'll set up the services, if they're in agreement. The other way is that sometimes I might have a call directly from caregivers or family members who might have identified a need for their loved one, falls, equipment needs, or something to make it easier for them. They would contact me and then I would set it up…. Also sometimes homemaking agencies that are providing service will contact us and say, “We're really struggling with turning Mr X, and maybe we could look at some sort of a lift or …” So we would then explore that option. And I would then put occupational therapy in to assess the appropriate equipment if necessary.

Eligibility for in-home services

According to study participants, not all referred clients are eligible for home-care services. Because Ontario home care is legislated to serve a very specific “homebound” population, clients' outdoor mobility has a significant impact on the allocation of home-care services. For instance, one participant stated,

We're pretty legislated by the Ministry of Health. The clients who we would accept in terms of eligibility, would be the clients that have a real difficulty getting out of their house, or their apartment … or getting out to the community. And we refer to them as “homebound.”

According to participants, the primary purpose of home-care services is to address medical necessities. Rehabilitation services are intended to ensure safety and are provided on a short-term basis. One participant described this vision in the following way:

Historically home care has not been as rehabilitation focused…. I think it is [the] same in hospitals and in other sectors as well. We are primarily health/curative focused, and rehab is seen as an extra. So in times of financial restraint and concern it's even harder…. The concept of helping individuals to be as independent as possible in their home sometimes takes second place to the emergent medical health issues.

Selection of clients

The vision of addressing necessities for homebound clients is apparent in the selection of home-care clients. According to one participant, there is a process for selecting clients:

So first of all we need to look into the criteria, whether or not the client can access the services as an outpatient … because it is one of the criteria for being admitted to home care.

However, everyone referred to home care is assessed. If a client is not eligible, he or she may be referred to other volunteer or fee-for-service community supports:

Everybody who gets referred to us … gets an [intake] assessment … So they're entitled to an assessment, [but] not necessarily [to publicly funded] services.

Case manager's assessment

Once deemed eligible, clients are assessed by the case manager before receiving any services. Case managers use a wide variety of processes in their assessments. Some rely on the decision-support tools embedded in RAI-HC, such as the Clinical Assessment Protocols (CAPs), Activities of Daily Living / Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (ADL/IADL) status, and various scores embedded in the RAI, to justify their decision; others rely on clinical indicators such as mobility, cognition, and balance. All case managers, however, reported that they prefer to evaluate clients at home before making any decisions. In their home assessments, they pay particular attention to the client's outdoor mobility:

If we get somebody calling from the community saying that they want physiotherapy, for example … Obviously one of our first priorities is to ask, “Can you get out?” to have your physiotherapy outside. And if you're not pretty much shut in or there's no other extenuating circumstance why you can't get out to get your physiotherapy, then we're just going to tell you, you have to get your physiotherapy … in an outpatient clinic, like everybody else.

The case managers and administrators we interviewed acknowledged the shortage of outpatient and day programmes for rehabilitation in the community. It is a challenge for them to provide service for clients who have no difficulty in outdoor mobility but do not have access to an outpatient or day programme in their community. In addition, such programmes are guided by strict eligibility criteria. One participant described his frustration:

The other thing that definitely impacts [decision making] is … the lack of accessibility to rehab clinics … or the reduction of outpatient clinics…. We have to get people into day programmes to supplement care or … provide a transitional level of care…. There's a requirement to have a need for two or more types of therapies services at day programmes. I think that impacts on decision making. Because it's harder to get people into those settings.

Referral to service provider

The most common reason for participants to refer a client to rehabilitation services was to ensure safety. For instance, one participant said,

Our goal … is to allow her to remain independent in her own home with supportive services, but I mean again it would have to be first and foremost to ensure [home] safety.

Participants identified numerous other reasons for referring clients to PT or OT services, however: to improve physical function, reduce pain, improve cognition, reduce falls, and recommend equipment. The extent of safety concerns is defined on the basis of these factors. For instance, safety concerns in the home would be greater for clients with multiple difficulties in physical functioning, a history of falls, and impaired cognition:

I mean for myself usually rehab is for someone who has mobility problems, memory issues, falls, equipment needs … strength issues, balance issues … range of motion issues. And all these are [creating] … safety … issues in their home.

Furthermore, participants described their tendency to refer to PT if the client has difficulty in physical mobility and to OT if the client has equipment needs or cognitive issues:

If it's dealing with equipment … e.g., wheelchair or cognition, then it's OT. If it's using your two legs and mobilization … then it's PT.

Volume of services

Participants told us that they determine the volume of therapy services based on either a predetermined or a collaborative approach. In a predetermined approach, a certain number of visits within a certain period are authorized for certain types of therapy goals. One participant described this type of decision making as follows:

The only plan that I come up with is … setting up the service…. We have standards of how many visits we can put in … and then we write down what the intervention is to be [and] whether that's from the physician's referral or from family.

In a collaborative approach, the volume of therapy services is determined based on client input, therapist assessment, and findings from the case manager's home visit. Usually the case manager begins by authorizing two visits by a therapy service for the therapist's assessment. The therapist then provides a report indicating the amount of service needed to accomplish the client's goals. All four home-care regions use this approach to some extent, alone or in combination with the predetermined approach:

Initially when the referral goes out they're given two visits over a 2-week period. And then what happens is that the therapist assesses and calls us to notify what their expectation [is] of the amount of visits needed…. Now I have a little bit of knowledge about what I'm expecting and sort of the amount of time … that I think is reasonable. So if someone's asking for an … unreasonable amount then I would question the request.

While there are variations across CCACs, case managers working within the same CCAC use similar approaches. High users of rehabilitation in both urban and rural areas used a collaborative approach more than a predetermined approach, while low users tended to use a predetermined approach to determine therapy volume.

Increasing therapy services

The process of increasing the number of visits usually involves reporting back to the case manager. If the case manager determines, based on his or her judgment of the situation or by reference to administrative statistics from previous years, that additional service is justified, the provider will be allotted additional visits (usually only approximately two). According to one participant, the process of negotiating more visits usually involves a telephone call from the therapist:

I would be talking to my OT or PT … but they're very good at saying to me that if they had two more visits they could probably … see a progress. But then they would also call me and say, “I've been in there six times to do physio. They refused to do it. They refused to let anybody help them, so we're done.”

For another participant, a case manager for a different CCAC, this process is much more formal and requires a written report:

Basically what you can do if they're on a pathway is that … if they reach the end of the pathway and the therapist feels … that intervention still needs to continue … then they just send you a report stating that they would like to do that. And obviously if it's reasonable, we will just extend that for another period. But I mean our interventions are fairly … short. I mean they're never going to be like ongoing … [for] months at a time, kind of thing. So you might extend them for another two or three visits or something like that, but … it wouldn't be a long extension.

At the time of our study, one of the participating CCACs was facing financial challenges; increasing therapy services required authorization from the client services manager:

Now … we're in … a cost-containment and we have wait lists…. I would have to go through my manager to get approval for any increase in visits. So right now we are to write out a template and justify why someone would need additional visits … and then the manager would be the one authorizing the increase. And then I would in turn tell the therapist if it was authorized or not.

Case manager's reassessment

According to the decision makers we interviewed, all participating regions have guidelines for reassessing clients in their homes, which dictate the time frame for reassessment based on clients' condition (acute vs. chronic) and their service level. For instance, one participant said, “Routinely it [the reassessment] would be about every 6 months. If she's getting a higher level of service it would be every 3 months.” In-home reassessment becomes a priority for case managers if the client is receiving a high volume of services from a personal support worker (PSW). For instance, one participant told us that “as long as somebody's got a PSW, I'm always going to have to reassess them.” Based on the reassessment, the client may continue to receive services, be discharged from home care (with community services as needed), or be placed in an alternative level of care if his or her needs cannot be met at home.

System factors affecting home-care services

After describing the decision-making process, participants were asked to comment on factors other than clients' needs that affect the allocation of PT and OT services from home care. Participants highlighted three system-level factors that influence the allocation of these services: cost containment, government funding, and sharing of client information.

Cost containment

All participants identified cost containment as the single most important factor affecting the use of PT and OT services. The term cost containment describes a situation in which a home care programme is having significant financial difficulty and needs to cut back on the services it provides. In this situation, the programme will usually provide only high-priority services while maintain waiting lists for lower-priority services. One participant described how this situation affects his programme:

[P]art of that reality is operating within our own existing budget. And not being able to run [a] deficit. So at the end of March, we have to make sure that our budget is balanced … otherwise there's a lot of financial implication[s] and ministry implications. So, if we foresee a time where we're not going to be able to continue to provide service to our existing clients and take on new clients, then from time to time we do go into cost containment. And most [home-care regions] operate in this fashion. A lot of them are policy driven. No [home-care regions] are allowed to carry over budget money at the end of the year. So it's difficult to kind of roll over dollars. So from time to time … [we] go into budget constraint. When that happens the entire system kind of clamps down. So we may start wait-listing … therapy clients, for example, or homemaking clients. It depends on … what we need to do. And that then is going to influence a coordinator's task … Because if, if that coordinator knows that the client's not going to get the service, then they may start talking about other resources in the community … you know … volunteer groups …

The government's funding method for home care

Several participants reported that at the time of our study, home-care programmes in Ontario were allocated funding for 1 year at a time, and at the end of the fiscal year unused resources would go back to the provincial government. As a result, there was no incentive to be efficient, since resources saved during the year could not be kept for the next year. Allocation of multi-year funding has been acknowledged as a solution to this inefficiency problem. For instance, one participant suggested

[h]aving organizations have multi-year funding. So allow us to have … 2 or 3 years … of funding. And that way if we were able to contain some cost in year 1 … we could roll that surplus over to year 2.

As she then explained,

that doesn't happen now. Like if we save money … Or if we find efficiencies within our system … all that money at the end of March 31 goes back to the ministry. So you already have a disincentive … built into your system.

Sharing of client information

Participants reported challenges in sharing client profiles with service providers because of a lack of coordination and administrative resources, which means that assessment information already collected by case managers must be collected again by the service provider. Several participants identified improving information sharing and training service providers on the assessment tools used by CCACs as solutions to this problem:

I think we need to look at assessment efficiencies…. What's being duplicated between a case management assessment and a rehab assessment. And get our [service] providers to start using some of the assessment information, so that their first visit isn't being lost in … collecting assessment information that's already been collected. So they have to work much more like teams with case managers and within their own organizations. So better coordination within … organizations for sharing information.

Summary

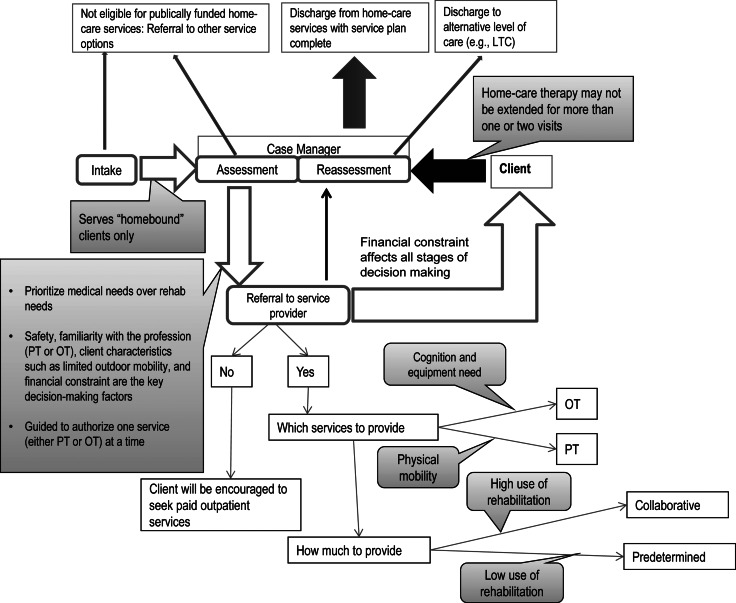

Figure 1 summarizes the overall course of decision making and the corresponding stages, management processes, and contextual factors that influence decisions about rehabilitation referrals in Ontario home care.

Figure 1.

The decision-making process in home care

DISCUSSION

Our primary objective in this study was to explore the decision-making process for allocating PT and OT services in home care in Ontario. Our findings suggest that access to home-care rehabilitation services is coordinated and allocated through a series of four stages, each with unique management processes embedded to guide decision making. In addition, participants identified some of the system-level factors that can be optimized to enhance home-care services, including funding methods and information-sharing processes.

According to Chappell and Hollander,17 a key performance indicator for any health system is a single and highly coordinated point of access to services. Figure 1 shows the overarching framework used in Ontario home care to determine the need for PT or OT services, together with associated management processes. All four stages of this framework are influenced by clients' needs, such as ADL/IADL restrictions and home safety concerns; however, they are also heavily influenced by financial constraints, which seem to decrease both regard for clinical considerations and ability to use preventive rehabilitation.

Our finding that financial concerns are a primary consideration in allocating therapy services reinforces those of several prior studies1,18–22 that described the process of allocating home-care services as a business concept. Furthermore, decisions about the frequency and volume of services, particularly for home-care regions that use predetermined approaches (pathway and benchmark), are more managerial than professional. This suggests that economic factors such as financial constraints are often more influential than client needs in case managers' decision making. As these factors become more influential, case managers will be less able to make decisions based on clinical assessment of their clients. This finding also echoes those of Ceci,20,21 Cott and colleagues,1 and Aronsen,18 who noted that for home-care workers, the primary barrier to providing client-centred care is the pressure of various economic forces in the home-care sector.

In the long term, ironically, the current emphasis on financial considerations is likely to lead to higher costs by limiting the use of preventive approaches (e.g., fall prevention) that could decrease the use of costly emergency services and hospitalization. Case managers are less likely to refer long-stay home-care clients for rehabilitation, even if their need for rehabilitation services is high.9 Further research is needed to demonstrate the long-term impact and cost savings of systemic interventions to allow greater provision of home-care rehabilitation where empirically and clinically indicated. Such empirical knowledge could help drive changes in practice and policy to integrate rehabilitation in the care of medically complex long-stay clients. This philosophy is already established and integrated in acute care, where rehabilitation routinely appears in various care pathways (e.g., for hip fractures). Clinicians and policy makers need take a step forward in integrating such practices for chronic, medically complex long-stay clients in the community.

Our study has several potential limitations, including the absence of member (participant) checking, the small sample size, and the use of telephone interviews. Our sample consisted of case managers and directors from four CCACs; our results show greater variation in decision-making processes between CCACs than among case managers within CCACs. Our findings, therefore, would have been enriched by the use of a larger sample of CCACs. Furthermore, all interviews were conducted by telephone, meaning that the interviewer was blinded to participants' informal communication.23

CONCLUSION

The decision-making process used to allocate therapy services in home care has four stages—intake, assessment, referral to service provider, and reassessment—each with its own guidelines and processes for decision making. Some system-level factors, such as information sharing and government funding methods, can potentially be improved to optimize home-care service delivery. Although we identified differences in how the volume of therapy services is determined, financial constraints are the primary contextual factor in determining referrals to rehabilitation professionals across all agencies. Given rising health care costs, we need to develop new models of funding and service delivery to ensure that home-care clients have access to rehabilitation geared toward preventing deterioration and reducing the need for more costly health care services.

KEY MESSAGES

What is already known on this topic

The benefits of physical and occupational therapy services, variations in service allocation, the effect of financial constraints, and the general lack of access to therapy services have been documented in prior studies. The purpose of this study was to explore the process of therapy service allocation in Ontario home care.

What this study adds

This study maps out the process involved in accessing home-care therapy services in Ontario and identifies issues that influence decisions about the allocation of these services; highlights the potential impact of economically driven policies on clients' access to home-care rehabilitation and points to potential inefficiencies of such policies; and, finally, notes the potential for new efficiencies within the current system, such as multi-year funding agreements that would encourage innovation in service modelling and potentially reduce costs over the long term.

Appendix 1

Vignettes A and B

| Vignette A | Vignette B |

|---|---|

| Mrs. Bond is an 85-year-old female, lives in a two-storey house. She has a long list of medical conditions, but they are all controlled by medications. Currently she is using a rollator for most of her mobility. Recently she started to have difficulty getting in/out of the bed, going down the stairs and walking long distances due to weakness and balance issues. She fell multiple times last month while going down the stairs but did not have any significant injury. She lives with her daughter, who recently started full-time employment. | Mrs. Jones is a 71-year-old female, lives alone in a two-storey house. She has a long list of medical conditions, but they are all controlled by medications. She also suffers from COPD and reports SOB after prolonged ambulation. Currently she is using a rollator for most of her mobility. She tripped on a piece of rug and fell about 3 months ago, with no significant injuries. Since then she started having pain in her left groin area after long-distance walking. About a month ago she was hospitalized for urinary-tract infection and developed significant weakness in her bilateral lower extremities. Currently she has significant difficulty doing the stairs. She also requires supervision for outdoor mobility. She receives personal support services twice a week for bathing. |

| Each vignette was accompanied by a PHP and full RAI-HC 2.0 assessment of the client. | |

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SOB=shortness of breath; PHP=personal health profile; RAI-HC=Resident Assessment Instrument–Home Care.

Appendix 2

Interview guide

| Open-ended questions |

|---|

|

|

Targeted questions using vignettes A and B |

|

PT=physiotherapy; OT=occupational therapy; CCAC=Community Care Access Centre; PSW=personal support worker; SW=social worker.

Physiotherapy Canada 2013; 65(2);125–132; doi:10.3138/ptc.2012-09

REFERENCES

- 1.Cott CA, Falter LB, Gignac M, et al. Helping networks in community home care for the elderly: types of team. Can J Nurs Res. 2008;40(1):19–37. Medline:18459270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, et al. A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006b;54(5):809–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x. Medline:16696748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada [Romanow Commission] Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. Saskatoon: The Commission; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Home Care Association. Portraits of home care in Canada [Internet] Mississauga (ON): The Association; 2008. [cited 2008 Mar]. Available from: http://www.cdnhomecare.ca/content.php?sec=4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Winter L, et al. Effect of an in-home occupational and physical therapy intervention on reducing mortality in functionally vulnerable older people: preliminary findings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006a;54(6):950–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00733.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00733.x. Medline:16776791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crotty M, Whitehead C, Miller M, et al. Patient and caregiver outcomes 12 months after home-based therapy for hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(8):1237–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00141-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(03)00141-2. Medline:12917867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giusti A, Barone A, Oliveri M, et al. An analysis of the feasibility of home rehabilitation among elderly people with proximal femoral fractures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(6):826–31. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.02.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2006.02.018. Medline:16731219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuisma R. A randomized, controlled comparison of home versus institutional rehabilitation of patients with hip fracture. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(5):553–61. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr525oa. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0269215502cr525oa. Medline:12194626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirdes JP, Fries BE, Morris JN, et al. Home care quality indicators (HCQIs) based on the MDS-HC. Gerontologist. 2004;44(5):665–79. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.5.665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.5.665. Medline:15498842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadjistavropoulos H, Bierlein C, Nevill S. Managing continuity of care through case co-ordination. Regina: University of Regina; 2003. [cited 2012 Aug 11]. Available from: http://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=0CFQQFjAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Furegina.ca%2F~hadjista%2FFinal_Report.pdf&ei=lXsmUIC_L4HhiALC_4D4Cw&usg=AFQjCNFi3GYQLaMAU1hajAnsLK0E0ceAbA&sig2=xZSsHZTtlYlRD7xCkMMP3w. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randall GE, Williams AP. Exploring limits to market-based reform: managed competition and rehabilitation home care services in Ontario. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1594–604. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.042. Medline:16198035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams AP, Barnsley J, Leggat S, et al. Long term care goes to market: managed competition and Ontario's reform of community based service. Can J Aging. 1999;18(2):125–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980800009752. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirdes JP, Berg K, Stolee P, et al. Enhancing the use of interRAI instruments in primary health care: the next step toward an integrated health information system / ideas (innovations in data, evidence and applications) for primary care. Final Report to the Primary Health Care Transition Fund. 2006. Grant G03-05690.

- 14.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srivastava A, Thomson SB. Framework analysis: a qualitative methodology for applied policy research. Journal of Administration and Governance. 2009;4(2):72–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerrish K, Chau R, Sobowale A, et al. Bridging the language barrier: the use of interpreters in primary care nursing. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(5):407–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00510.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00510.x. Medline:15373819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chappell NL, Hollander MJ. An evidence-based policy prescription for an aging population. Healthc Pap. 2011;11(1):8–18. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2011.22246. Medline:21464622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aronson J. Silenced complaints, suppressed expectations: the cumulative effects of home care rationing. Int J Health Serv. 2006;36(3):535–56. doi: 10.2190/CGPJ-PRWN-B1H6-YVJB. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/CGPJ-PRWN-B1H6-YVJB. Medline:16981630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronsen J, Neysmith SM. The work of visiting homemakers in the context of cost cutting in long-term care. C J Public Health. 1996;87:422–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceci C. Increasingly distant from life: problem setting in the organization of home care. Nurs Philos. 2008b;9(1):19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2007.00331.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-769X.2007.00331.x. Medline:18154634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ceci C. Impoverishment of practice: analysis of effects of economic discourses in home care case management practice. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2006a;19(1):56–68. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2006.18049. Medline:16610298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denton MA, Zeytinoğlu IU, Davies S. Working in clients' homes: the impact on the mental health and well-being of visiting home care workers. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2002;21(1):1–27. doi: 10.1300/J027v21n01_01. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J027v21n01_01. Medline:12196932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]