Abstract

Background

In patients with severe aortic stenosis, left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with increased myocardial stiffness and dysfunction linked to cardiac morbidity and mortality. We aimed at systematically investigating the degree of left ventricular mass regression and changes in left ventricular function six months after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) by cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR).

Methods

Left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area (LVMi), end diastolic volume indexed to body surface area (LVEDVi), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and stroke volume (SV) were investigated by CMR before and six months after TAVI in patients with severe aortic stenosis and contraindications for surgical aortic valve replacement.

Results

Twenty-sevent patients had paired CMR at baseline and at 6-month follow-up (N=27), with a mean age of 80.7±5.2 years. LVMi decreased from 84.5±25.2 g/m2 at baseline to 69.4±18.4 g/m2 at six months follow-up (P<0.001). LVEDVi (87.2±30.1 ml /m2vs 86.4±22.3 ml/m2; P=0.84), LVEF (61.5±14.5% vs 65.1±7.2%, P=0.08) and SV (89.2±22 ml vs 94.7±26.5 ml; P=0.25) did not change significantly.

Conclusions

Based on CMR, significant left ventricular reverse remodeling occurs six months after TAVI.

Keywords: Ventricular remodeling, Transcatheter aortic valve implantation, Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Background

In patients with severe aortic stenosis, left ventricular hypertrophy is a frequent pathophysiological adaptation to pressure overload [1]. However, the enlarged myocardial cell mass and interstitial fibrosis result in increased myocardial stiffness and dysfunction [2-5]. Aortic valve replacement reduces afterload in patients with severe aortic stenosis. In recent years, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as a valuable alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement in patients at high surgical risk because of age and/or comorbidities [6-10]. Numerous studies have shown excellent and sustained transvalvular hemodynamics after TAVI, together with a significant improvement in symptoms and quality of life [11-13].

Hemodynamic changes that occur after TAVI have been generally evaluated by echocardiographic methods [14,15]. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is more accurate and reproducible than two-dimensional echocardiography in the three-dimensional volumetric evaluation of left ventricular volumes, function and mass [16]. However, there is a lack of knowledge on the use of CMR in TAVI patients for assessing the above parameters. To fill this gap, we aimed at using CMR to investigate left ventricular reverse remodeling at six-month after TAVI.

Methods

Patients population

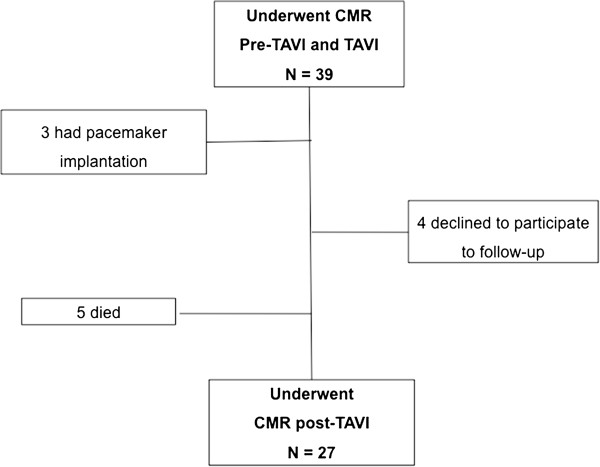

Twenty-seven patients who underwent successful TAVI using the Medtronic CoreValve (Medtronic CoreValve Percutaneous System, Medtronic CV) or Edwards SAPIEN (Edwards Lifesciences Inc, Irvine, CA, USA) bioprostheses were assessed with CMR before the procedure and at six-month follow up (Figure 1). The institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol and all patients gave informed consent. All patients were informed about the potential risks of CMR [17] and gave their written consent. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were previously reported [18].

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Study endpoints

Left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area (LVMi), left ventricular end diastolic volume indexed to body surface area (LVEDVi), stroke volume (SV), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and mass/volume ratio were assessed at baseline and six months. The occurrence of subendocardial fibrosis was assessed in terms of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) at baseline and six months.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

All CMR studies were performed with a 1.5 Tesla Magnetic Resonance Imaging scanner (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Netherlands) with a flexible cardiac five-element phased-array coil and a vector electrocardiogram for R wave triggering using a standard MRI imaging protocol. In brief, multiple short axis (SAX) cine images using a breath-hold steady state free precession sequence with parallel imaging (balanced Fast Field Echo (FFE); Repetition time (TR)/Echo time (TE) = 3.1/1.56 ms; slice thickness 8 mm; matrix 180 x 175 ; flip angle 60°; acquisition voxel-size = 1.78 × 1.82 × 8 mm3 ; reconstructed voxel-size = 1.25 × 1.25 × 8 mm3 acquisition; sensitivity encoding (SENSE)-factor = 2) were acquired after the acquisition of true two- and four- chamber planes for the assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF %).The CMR images were analyzed off-line using a commercial software (Philips Medical Systems Extended MK Word Space Version 2.6.3.1) by a blinded experienced CMR reader unaware of patients’ clinical data. For assessment of left ventricular function, the end-diastolic and end-systolic cine frames were identified for each slice and the endocardial and epicardial borders were manually traced. The end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes were then calculated using the Simpson’s rule (i.e., sum of cavity sizes across all continuous slices) and indexed to body surface area. LVEF was calculated as (end-diastolic volume - end-systolic volume)/end-diastolic volume. LVMi was derived via the Simpson’s method multiplied by the specific gravity of myocardium (1.055 g/ml) and indexed to the body surface area. LVMi was divided by the LVEDVi to obtain the mass/volume ratio. Normal values used in this study for both LV systolic function and mass were those reported by Maceira et al. [19]. Left ventricular reverse remodeling was defined as a significant reduction in LVMi between baseline and 6 months.

To evaluate LGE, an intravenous bolus dose of 0.2 mmol/kg body weight of gadobutrol (Gadovist, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) was administered at a rate of 3 ml/s by a power injector (MedradSpectris Solaris, Medrad, USA). Ten minutes after gadolinium injection, a ‘Look Locker’ sequence was performed to obtain the most appropriate inversion time to null the signal intensity of normal myocardium. LGE images were then acquired using the following parameters: fast gradient echo, repetition time 6.1 ms, echo time 3 ms, flip angle 25°, field of view 320 mm, slices thickness 10 mm, acquired in the left ventricular short axis over 2 RR intervals and no interslice gap. LGE was evaluated by visual assessment in short-axis slices and further characterized by spatial location, pattern, and LGE quantification (1–25%, 25–50%, 50–75%, >75%) [20].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviations and were compared using the Student t paired test. Univariate and multivariate correlates of left ventricular reverse remodeling were analyzed by logistic regression. To explore their significance as baseline predictors, LVMi (< or ≥ 89 g/m2) and LVEF (< or ≥ 55%) were dichotomyzed as previously described [19]. A two-sided p value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All data were processed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

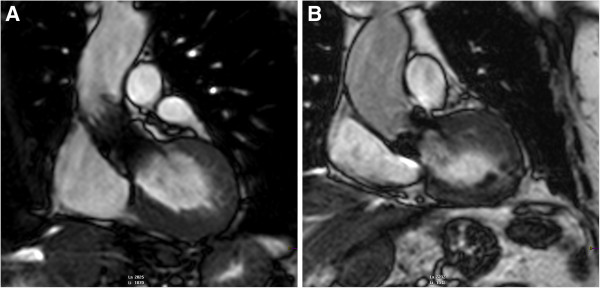

The study cohort had a mean age of 80.7±5.2 years. Detailed reasons for TAVI referral were the following: 16 (59.3%) patients had a proibitive Logistic EuroSCORE, 1 (3.7%) patient had a porcelain aorta, 3 patients (11.1%) had received thoracic radiation therapy for lung cancer, 1 (3.7%) had a severe form of diabetic lipodystrophy, 1 patient (3.7%) had cirrhosis and 5 patients (18.5%) refused surgery. All patients were in New York Heart Association class III-IV and 37% of them were previously hospitalized for congestive heart failure (Table 1). The Medtronic CoreValve and Edwards SAPIEN prostheses were used in 21 (77.8%) and 6 (22.2%) of cases, respectively (Table 1, Figure 2). All patients showed an improvement in symptoms at six-month follow-up (all were in New York Heart Association class I-II).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Variables | N = 27 |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) |

10 (37) |

| Age, (mean ± DS) |

80.7 ± 5.2 |

| Log EuroScore, (mean ± DS) |

14.9 ± 12 |

| BMI, (mean ± DS) |

27.5 ± 5.5 |

|

Symptoms |

|

| Syncope, n (%) |

4 (14.8) |

| Unstable Angina, n (%) |

6 (22.3) |

| Hospitalization for heart failure, n (%) |

10 (37) |

| Dyspnoea, n (%) |

25 (92.6) |

|

RiskFactors |

|

| Hypertension, n (%) |

23 (85.1) |

| Diabetes , n (%) |

4 (14.8) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) |

9 (33.3) |

| Smoker, n (%) |

3 (11.1) |

| Ex smoker, n (%) |

2 (7.4) |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) |

1 (3.7) |

| Renal failure (creatinine > 2 mg/dL), n (%) |

5 (18.5) |

| COPD, n (%) |

7 (25.9) |

| Chronic obstructive arterial disease, n (%) |

2 (7.4) |

| Previous CABG, n (%) |

2 (7.4) |

| Previous PCI, n (%) |

11 (40.7) |

| Untreated obstructive CAD, n (%) |

2 (7.4) |

| Previous MI, n (%) |

7 (25.9) |

| Previous Stroke, n (%) |

3 (11.1) |

| Class NYHA III-IV pre-TAVI, n (%) |

27 (100) |

| Class NYHA III-IV post-TAVI, n (%) |

0 (0) |

|

Implanted valve |

|

| Medtronic CoreValve26 mm, n (%) |

11 (40.7) |

| Medtronic CoreValve 29 mm, n (%) |

10 (37.1) |

| Edwards SAPIEN 23 mm, n (%) |

1 (3.7) |

| Edwards SAPIEN 26 mm, n (%) | 5 (18.5) |

BMI body mass index; CABG coronary artery by-pass graft; CAD coronary artery disease; COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI myocardial infarction; PCI percutaneous coronary intervention.

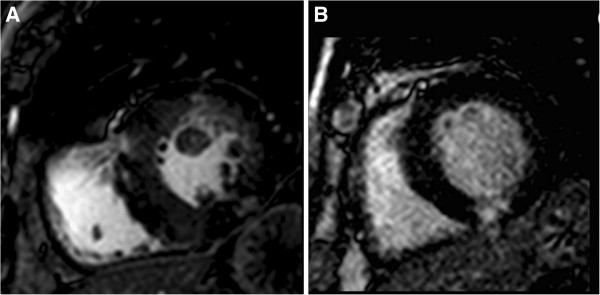

Figure 2.

CMR left ventricular outflow tract cine view after TAVI. Panel A. Core Valve bioprosthesis; Panel B. Edwards SAPIEN valve bioprosthesis.

CMR outcomes

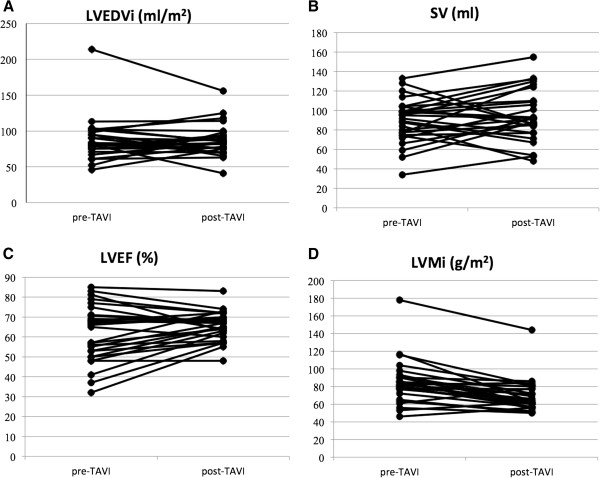

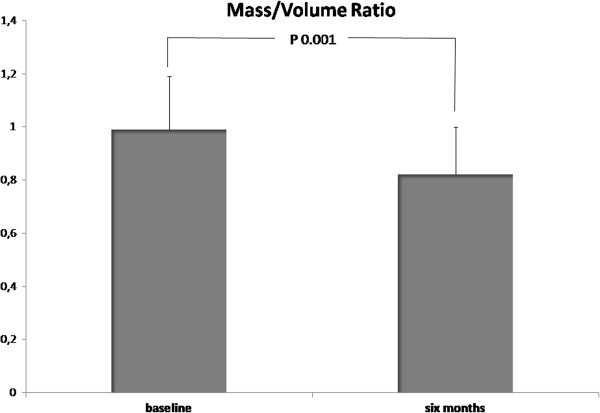

All patients well tolerated CMR and no clinical adverse event was recorded during the examination both at baseline and at 6 months. The images quality was diagnostic in 100% of examinations. The mass/volume ratio decreased significantly from baseline to follow-up (P=0.001) (Table 2, Figure 3). Figure 4 displays changes in CMR endpoints from baseline to follow up. LVMi decreased from 84.5±25.2 g/m2 to 69.4±18.4 g/m2 (P<0.001). Conversely, LVEDVi, SV and LVEF did not change significantly (Table 2, Figure 4). After entering in a multivariable model all potential baseline confounding factors with p<0.20 at univariate analysis, no significant predictors of left ventricular reverse remodeling was identified.

Table 2.

CMR characteristics in the study population

| |

Baseline |

Sixmonths |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 27 | N = 27 | ||

| LVEF (%) |

61.5±14.5 |

65.1±7.2 |

0.08 |

| LVEDV (ml) |

151.4±50.1 |

151.7±38.9 |

0.97 |

| LVEDVi (ml/m2) |

87.2±30.14 |

86.4±22.3 |

0.84 |

| LVESV (ml) |

61.1±44.6 |

53.4±19.2 |

0.16 |

| LVESVi (ml/m2) |

35.29±24.7 |

30.5±11.5 |

0.15 |

| LVM (g) |

148.2±44.6 |

122.5±34.8 |

<0.001 |

| LVMi (g/m2) |

84.5±25.2 |

69.4±18.4 |

<0.001 |

| Stroke volume (ml) |

89.2±22 |

94.7±26.5 |

0.25 |

| CardiacOutput (L/min) |

5.9±1.4 |

5.9±1.3 |

0.98 |

| Mass/Volume ratio | 0.99±2 | 0.82±0.18 | 0.001 |

CMR cardiovascular magnetic resonance; LVEDVi indexed left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESVi indexed left ventricular end systolic volume; LVMi indexed left ventricular mass; LVEDV left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; LVM left ventricular mass; LVESV left ventricular end systolic volume.

Figure 3.

Changes in CMR mass/volume ratio from baseline to follow-up. The mass/volume ratio decreased from 0.99±0.2 at baseline to 0.82±0.18 at six months follow-up (P=0.001).

Figure 4.

Changes in CMR endpoints from baseline to follow up. LVEDVi (87.2±30.1 ml /m2vs 86.4±22.3 ml/m2; p = 0.84), SV (89.2±22 ml vs 94.7 ml ±26.5; p = 0.25) and LVEF (61.5±14.5% vs 65.1±7.2%, p = 0.08), did not change significantly (Panel A, B, C). LVMi decreased from 84.5±25.2 g/m2 at baseline to 69.4±18.4 g/m2 at six months follow-up (p < 0.001) (Panel D).

Because myocardial fibrosis may significantly impact clinical outcomes [21], we repeated the analysis by excluding patients with fibrosis of ischemic or non ischemic nature (N=10) and found a consistent evidence of significant LVMi reduction (83.9 ± 28.9 g/m2vs 69.5± 22.3 g/m2, P <0.001), with no significant changes for other parameters (Table 3).

Table 3.

CMR characteristics of patients without fibrosis at baseline

| |

Baseline |

Sixmonths |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N= 17 | N= 17 | ||

| LVEF (%) |

63.9±14.6 |

67.6±76.5 |

0.15 |

| LVEDV (ml) |

152.7±57.5 |

154.7±44.2 |

0.82 |

| LVEDVi (ml/m2) |

87.1±35 |

87.0±25.2 |

0.99 |

| LVESV (ml) |

60±48.8 |

51.1±22.7 |

0.27 |

| LVESVi (ml/m2) |

34.5±29 |

28.9±13.4 |

0.25 |

| LVM (g) |

148.0±50.4 |

124.7±41.8 |

0.000 |

| LVMi (g/m2) |

83.9±28.9 |

69.5±22.3 |

0.000 |

| Stroke volume (ml) |

90.9±20 |

98.5±28 |

0.57 |

| CardiacOutput (L/min) | 5.9±1.3 | 6.2±1.3 | 0.98 |

CMR cardiovascular magnetic resonance; LVEDVi indexed left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESVi indexed left ventricular end systolic volume; LVMi indexed left ventricular mass; LVEDV left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; LVM left ventricular mass; LVESV left ventricular end systolic volume.

Gadolinium was not administered to 3 patients due to severe renal failure (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min). At baseline, evidence of LGE was present in 10 (41.6%) of 24 cases. Causes for LGE were ischemic in 8 cases, and non-ischemic in 2 cases (Figure 5). At follow up, there were no new cases of LGE related to the intervention although one patient did have a pre-procedural myocardial infarction with new LGE at follow up.

Figure 5.

Different patterns of LGE in TAVI patients. Focal mid-wall fibrosis at mid segment of the inferior wall (Panel A). Focal transmural myocardial necrosis at basal segment of the inferior wall (Panel B).

Discussion

Although limited by the small sample size, our study enables a deeper understanding of left ventricular reverse remodeling occurring after TAVI in a complex clinical cohort, by means of a reliable and accurate technique as CMR. In particular, at six months, we observed a statistically significant reduction of LVMi.

Regression of myocardial hypertrophy due to the decrease of ventricular afterload after surgical aortic valve replacement is a well-recognized phenomenon [5,22,23]. In particular, left ventricular mass decreases mainly within the first six months after surgical valve replacement. This observation has been also proven in studies based on CMR. In a CMR study of 24 patients, Biederman et al. [24] demonstrated that following surgical valve replacement, left ventricular mass markedly decreased at six months (157 ± 42 to 134 ± 32 g/m2, p < 0.005) and continued to further trend downward at 4 years (127 ± 32 g/m2; p =NS). Lamb et al. [25] showed that, early after surgical valve replacement, patients with aortic valve stenosis show a decrease in both LVMi, LVMi/LVEDVi ratio and improvement in diastolic filling.

Studies based on echocardiography seem to confirm that after TAVI the left ventricle undergoes a similar reverse remodeling process [26-30]. In a study by Giannini et al. comparing patients who underwent TAVI with the CoreValve bioprosthesis with those who underwent surgical aortic replacement, left ventricular reverse remodeling was found in all patients in the absence of prosthesis-patient mismatch [29]. Tzikas et al. found a significant regression in left ventricular masses in 63 consecutive patients one year after TAVI. However, regression was incomplete and was not accompanied by an improvement in left ventricular diastolic function [30]. However, it is important to underscore that transthoracic echocardiography has several limitations for the assessment of left ventricular volumes and LVEF, while CMR is currently considered the gold-standard for their assessment, especially in case of heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, poor acoustic window or discrepancies between different methodologies [16]. In fact, the accuracy of left ventricular volumes and LVEF with two-dimensional echocardiography is limited by image position, geometric assumptions, and boundary tracing errors [31]. To date, few studies have been performed with CMR to assess left ventricular remodeling after TAVI [32,33]. Indeed, CMR is a noninvasive technique that allows for accurate measurement of left ventricular mass and volumes with high reproducibility without the use of geometric assumptions, thereby providing potentially more accurate information [34].

The significant reduction of the left ventricular mass observed in our study was not accompanied by a corresponding significant increase in LVEF and SV. Several studies demonstrated improved LVEF after surgical aortic valve replacement, particularly in patients with low preoperative ejection fraction [35]. However, in patients with normal preoperative LVEF, results were variable. In particular, it has been suggested that the improvement in left ventricular function is more pronounced in patients with LVEF < 50% [35]. Parameters that could influence the left ventricular reverse remodeling process include age [36], female sex [37], size of the prosthesis [38], presence of fibrosis [39] and myocardial perfusion reserve [40]. In addition, we have not observed the significant change in left ventricular volume shown in studies of the surgical aortic valve replacement [24,25,39]. This may suggest a different process of reverse remodeling between TAVI and SAVR, but the lack of a comparative control arm in our study does not allow drawing firm conclusions in this regards.

We did not collect CMR data regarding post-TAVI aortic regurgitation that could have influenced left ventricular remodeling. However, based on trans-thoracic echocardiography, no patient had a residual severe aortic insufficiency, while a mild to moderate insufficiency was present in 4 patients, a mild insufficiency in 7 and no hemodynamically significant regurgitation in the remaining population. Moreover, another major limitation of this study is the lack of information on diastolic dysfunction, flow, and changes in gradients and aortic valve areas pre and post TAVI. Finally, our study demonstrated the absence of periprocedural myocardial infarction potentially caused by the deployment of the prosthesis and possible calcium embolization.

Conclusions

This CMR study explored the mid-term hemodynamic effects of TAVI. Our results expands on previous findings from echocardiography studies by means of a more precise and reliable imaging technique. A significant left ventricular reverse remodeling was shown at 6 months from TAVI. The implication of this finding remains unclear and should be explored in large dedicated studies with clinical endpoints.

Abbreviations

CMR: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance; LVEDVi: Left ventricular end diastolic volume indexed to body surface area; LVMi: Left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; SV: Stroke volume; TAVI: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Competing interests

Non-financial competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ALM conceived and designed the study, participated in data analysis, interpretation and manuscript drafting and was responsible for the final manuscript draft. AS participated in study design, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis and manuscript drafting. DC participated in data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis and manuscript drafting. AS, AC, IC, GP, MF and RP performed additional data analysis. CP and CT participated in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Alessio La Manna, Email: lamanna.cardio@gmail.com.

Alessandra Sanfilippo, Email: sanfi.ale@gmail.com.

Davide Capodanno, Email: dcapodanno@gmail.com.

Antonella Salemi, Email: antonellasalemi@ymail.com.

Alessandra Cadoni, Email: alessandra.cadoni10@gmail.com.

Irene Cascone, Email: irenu82@hotmail.it.

Gesualdo Polizzi, Email: gesualdop@yahoo.it.

Michele Figuera, Email: micfiguera@tiscali.it.

Rosetta Pittalà, Email: rosetta.ptt@gmail.com.

Carmelo Privitera, Email: carmeloprivitera@yahoo.it.

Corrado Tamburino, Email: tambucor@unict.it.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circ. 2000;102(4):470–479. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto CM, Bonow RO. In: Braunwald’s heart disease. 8. Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, editor. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008. Aortic stenosis; pp. 1626–1628. [Google Scholar]

- Carabello BA, Paulus WJ. Aorticstenosis. Lancet. 2009;373:956–966. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber IL, Stewart RA, Legget ME, West TM, French RL, Sutton TM, Yandle TG, French JK, Richards AM, White HD. Increased plasma natriuretic peptide levels reflect symptom onset in aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2003;107:1884–1890. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000060533.79248.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto CM. Valvular aortic stenosis: disease severity and timing of intervention. J Am CollCardiol. 2006;47:2141–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajarias A, Cribier AG. Outcome and saphety of percutaneous valve replacement. J Am CollCardiol. 2009;53:1829–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC MM, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Brown DL, Block PC, Guyton RA, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Douglas PS, Petersen JL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock S. PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburino C, Capodanno D, Ramondo A, Petronio AS, Ettori F, Santoro G, Klugmann S, Bedogni F, Maisano F, Marzocchi A, Poli A, Antoniucci D, Napodano M, De Carlo M, Fiorina C, Ussia GP. Incidence and predictors of early and late mortality after transcatheter AorticValve implantation in 663 patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2011;123:299–308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.946533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DR Jr, Mack MJ, Kaul S, Agnihotri A, Alexander KP, Bailey SR, Calhoon JH, Carabello BA, Desai MY, Edwards FH, Francis GS, Gardner TJ, Kappetein AP, Linderbaum JA, Mukherjee C, Mukherjee D, Otto CM, Ruiz CE, Sacco RL, Smith D, Thomas JD. 2012 ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS expert consensus document on transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(13):1200–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, Svensson LG, Webb JG, Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Dewey TM, Thourani VH, Pichard AD, Fischbein M, Szeto WY, Lim S, Greason KL, Teirstein PS, Malaisrie SC, Douglas PS, Hahn RT, Whisenant B, Zajarias A, Wang D, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Leon MB. PARTNER Trial Investigators. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(18):1686–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C, Bauer F, Agatiello C, Sebagh L, Bash A, Nusimovici D, Litzler PY, Bessou JP, Leon MB. Early experience with percutaneous transcatheter implantation of heart valve prosthesis for the treatment of end-stage inoperable patients with calcific aortic stenosis. J Am CollCardiol. 2004;43:698–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube E, Schuler G, Buellesfeld L, Gerckens U, Linke A, Wenaweser P, Sauren B, Mohr FW, Walther T, Zickmann B, Iversen S, Felderhoff T, Cartier R, Bonan R. Percutaneous aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in high-risk patients using the second- and current third-generation self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis: device success and 30-day clinical outcome. J Am CollCardiol. 2007;50:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussia GP, Barbanti M, Cammalleri V, Scarabelli M, Mulè M, Aruta P, Pistritto AM, Immè S, Capodanno D, Sarkar K, Gulino S, Tamburino C. Quality-of-life in elderly patients one year after transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe aortic stenosis. EuroIntervention. 2011;7(5):573–579. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I5A93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherif MA, Abdel-Wahab M, Awad O, Geist V, El-Shahed G, Semmler R, Tawfik M, Khattab AA, Richardt D, Richardt G, Tölg R. Early hemodynamic and neurohormonal response after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am Heart J. 2010;160(5):862–869. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzmann M, Lindstaedt M, Bojara W, Mügge A, Germing A. Hemodynamic results and changes in myocardial function after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am Heart J. 2010;159(5):926–932. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothues F, Smith GC, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Collins P, Klein HU, Pennell DJ. Comparison of interstudy reproducibility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance with two-dimensional echocardiography in normal subjects and in patients with heart failure or left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Shellock FG. Magnetic resonance imaging safety: implications for cardiovascular patients. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;3:171–182. doi: 10.1081/JCMR-100107466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Manna A, Sanfilippo A, Capodanno D, Salemi A, Polizzi G, Deste W, Cincotta G, Cadoni A, Marchese A, Figuera M, Ussia GP, Pittalà R, Privitera C, Tamburino C. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the assessment of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a pilot study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:82. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceira AM, Prasad SK, Khan M, Pennell DJ. Normalized left ventricularsystolic and diastolic function by steady state free precession cardiovascularmagnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8(3):417–426. doi: 10.1080/10976640600572889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod RH, Prakash A, Powell AJ, Geva T. Myocardial fibrosis identified by cardiac magnetic resonance late gadolinium enhancement is associated with adverse ventricular mechanics and ventricular tachycardia late after Fontan operation. J Am CollCardiol. 2010;55:1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidemann F, Herrmann S, Störk S, Niemann M, Frantz S, Lange V, Beer M, Gattenlöhner S, Voelker W, Ertl G, Strotmann JM. Impact of myocardial fibrosis in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2009;120:577–584. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.847772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidis I, Tsoukas A, Parthenakis F, Gournizakis A, Kassimatis A, Rallidis L, Nihoyannopoulos P. Four year follow up of aortic valve replacement for isolated aortic stenosis: a link between reduction in pressure overload, regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, and diastolic function. Heart. 2001;86:309–316. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T, Falk V, Langebartels G, Krüger M, Bernhardt U, Diegeler A, Gummert J, Autschbach R, Mohr FW. Prospectively randomized evaluation of stentless versus conventional biological aortic valves: impact on early regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1999;100(19 Suppl):II6–II10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.suppl_2.ii-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman RWW, Magovern JA, Grant BS, Williams RB, Yamrozik JA, Vido DA, Rathi VK, Rayarao G, Caruppannan K, Doyle M. LV reverse remodeling imparted by aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis; is it durable? A cardiovascular MRI study sponsored by the American Heart Association. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:53. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb HJ, Beyerbacht HP, de Roos A, van der Laarse A, Vliegen HW, Leujes F, Bax JJ, van der Wall EE. Left ventricular remodeling early after aortic valve replacement: differential effects on diastolic function in aortic valve stenosis and aortic regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(12):2182–88. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg LM, Tamás E, Vánky F, Nielsen NE, Engvall J, Nylander E. Left and right ventricular function in aortic stenosis patients 8 weeks post-transcatheter aortic valve implantation or surgical aortic valve replacement. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12(8):603–11. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzmann M, Lindstaedt M, Bojara W, Mügge A, Germing A. Hemodynamic results and changes in myocardial function after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am Heart J. 2010 May;159(5):926–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bello V, Giannini C, De Carlo M, Delle Donne MG, Nardi C, Palagi C, Cucco C, Dini FL, Guarracino F, Marzilli M, Petronio AS. Acute improvement in arterial-ventricular coupling after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (CoreValve) in patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28(1):79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini C, Petronio AS, Talini E, De Carlo M, Guarracino F, Grazia M, Donne D, Nardi C, Conte L, Barletta V, Marzilli M, Di Bello V. Early and late improvement of global and regional left ventricular function after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis: an echocardiographic study. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1(3):264–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzikas A, Geleijnse ML, Van Mieghem NM, Schultz CJ, Nuis RJ, van Dalen BM, Sarno G, van Domburg RT, Serruys PW, de Jaegere PP. Left ventricular mass regression one year after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(3):685–91. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu EO, Barasch E, Mihalatos DG, Katz A, Lachmann J, Han J, Reichek N, Gopal AS. Relative importance of errors in left ventricular quantitation by two-dimensional echocardiography: insights from three-dimensional echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:990–97. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour A, Ismail TF, Moat N, Gulati A, Roussin I, Alpendurada F, Park B, Okoroafor F, Asgar A, Barker S, Davies S, Prasad SK, Rubens M, Mohiaddin RH. Multimodality imaging in transcatheter aortic valve implantation and post-procedural aortic regurgitation: comparison among cardiovascular magnetic resonance, cardiac computed tomography, and echocardiography. J Am CollCardiol. 2011;58(21):2165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherif MA, Abdel-Wahab M, Beurich HW, Stöcker B, Zachow D, Geist V, Tölg R, Richardt G. Haemodynamic evaluation of aortic regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation using cardiovascular magnetic resonance. EuroIntervention. 2011;7(1):57–63. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I8A12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada YJ, Shiota T. A meta-analysis and investigation for the source of bias of left ventricular volumes and function by three-dimensional echocardiography in comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:126–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C, Bauer F, Agatiello C, Nercolini D, Tapiero S, Litzler PY, Bessou JP, Babaliaros V. Treatment of calcific aortic stenosis with the percutaneous heart valve: mid-term follow-up from the initial feasibility studies: the French experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bové T, Van Belleghem Y, François K, Caes F, Van Overbeke H, Van Nooten G. Stentless and stented aortic valve replacement in elderly patients: factors affecting midterm clinical and hemodynamical outcome. Eur J CardiothoracSurg. 2006;30(5):706–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida K, Morice MC, Chevalier B, Hovasse T, Romano M, Garot P, Farge A, Donzeau-Gouge P, Bouvier E, Cormier B, Lefèvre T. Sex-related differences in clinical presentation and outcome of transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe aortic stenosis. J Am CollCardiol. 2012;59(6):566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensky PR, Loubani M, Keal RP, Samani NJ, Sosnowski AW, Galiñanes M. Does the type of prosthesis influence early left ventricular mass regression after aortic valve replacement? Assessment with magnetic resonance imaging. Am Heart J. 2003;146(4):E13. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flett AS, Sado DM, Quarta G, Mirabel M, Pellerin D, Herrey AS, Hausenloy DJ, Ariti C, Yap J, Kolvekar S, Taylor AM, Moon JC. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis in severe aortic stenosis: an equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. EurHeart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13(10):819–26. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steadman CD, Jerosch-Herold M, Grundy B, Rafelt S, Ng LL, Squire IB, Samani NJ, McCann GP. Determinants and functional significance of myocardial perfusion reserve in severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(2):182–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]