Abstract

Objectives

To compare the cochlear distribution of low-dose fluorescent gentamicin after intra-tympanic administration in guinea pig (GPs) with clinical data of low dose intra-tympanic gentamicin in patients with intractable vertigo.

Materials and Methods

Purified gentamicin-Texas Red (GTTR) was injected intratympanically into GPs and the cochlear distribution and time course of GTTR fluorescence in outer hair cells (OHCs) was determined using confocal microscopy.

Results

GTTR was rapidly taken up by OHCs, particularly in the subcuticular zone. GTTR was distributed in the cochlea in a decreasing baso-apical gradient, and was retained within OHCs without significant decrease in fluorescence until 4 weeks after injection.

Conclusion

OHCs rapidly take up GTTR after intra-tympanic administration with slow clearance.

Clinical Application

A modified low-dose titration intratympanic approach was applied to patients with intractable Ménière’s Disease (MD) based on our animal data and the clinical outcome was followed. After the modified intratympanic injections for MD patients, vertigo control was achieved in 89% patients, with hearing deterioration identified in 16% patients. The 3-week interval titration injection technique thereby had a relatively high vertigo control rate with a low risk of hearing loss, and is a viable alternative to other intratympanic injection protocols.

Keywords: Gentamicin, Intratympanic injection, Ménière’s disease, Vertigo

Ménière’s disease (MD) is characterized by episodic vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and aural fullness. The symptoms of vertigo in 5% to 10% of patients with MD cannot be controlled through medical treatment. For patients with intractable MD, surgical interventions are frequently recommended. Labyrinthectomy and vestibular neurectomy are highly effective in eliminating vertigo, but they may have severe complications such as profound sensorineural hearing loss, cerebrospinal fluid leak, facial paralysis, meningitis, or even death (1,2).

To control vertigo effectively while minimizing the morbidity of operations and preserving hearing, clinicians are turning to chemical labyrinthectomy using aminoglycoside antibiotics, notably gentamicin. A meta-analysis (3) indicated that complete vertigo control was achieved in 74.7% of patients, with complete and substantial control obtained in 92.7% of patients. The control rate of previous studies ranged from 76%to 96%(4–7). However, hearing loss was reported in 17% to 30% of patients with intratympanic injection (4,5,8–10). Minimizing the incidence of hearing loss is a major challenge for intratympanic gentamicin injection.

Gentamicin is considered to be more vestibulotoxic than cochleotoxic (11,12), and its ototoxicity is dose dependent. Gentamicin can provide relief of vertigo if an appropriate dose is administered, without total destruction of the vestibular and cochlear sensory neuroepithelium (13). The appropriate dose is determined by many factors, the most important of which seems to be the frequency of intratympanic gentamicin injections.

Previous studies tried various treatment protocols such as multiple daily or weekly dosing, low-dose technique, continuous microcatheter delivery, and titration technique, each with good results (14). Despite the efficacy of intratympanic gentamicin injection to control vertigo, controversies regarding the end point, dosage, and frequency of gentamicin injection remain. In addition, further data on clinical outcomes and basic scientific substantiation are required to establish the validity of intratympanic gentamicin therapy. Exploring the distribution and pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in the guinea pig (GP) inner ear after local application will help to determine the optimal frequency of intratympanic gentamicin injection.

Previous studies have described the inner ear distribution of gentamicin (15–18) and its time course, dependent on concentration, within the inner ear after intratympanic injection (19,20). Roehm et al. (17) demonstrated that gentamicin was avidly taken up and retained by various inner ear cells in the treated ear 4 hours after injections, whereas the density of generalized immunolabeling fell to background levels in the injected ear over 14 days. Lyford-Pike et al. (16) observed that Type I hair cells are more susceptible to gentamicin as they avidly take up or retain the drug 1 week after administration. Although most previous studies identified gentamicin by immunohistochemistry or autoradiography, these methods cannot follow the uptake of gentamicin by living cells in real time, whereas pharmacokinetic data require more survival times to obtain the time course of gentamicin concentration, coupled with accurate detection methods. Wang and Steyger (21) demonstrated that the distribution of gentamicin–Texas Red (GTTR) is largely identical to immunolabeled or tritiated gentamicin, showing that GTTR is a valid probe, and that the pharmacokinetics of systemically administered GTTR uptake by cochlear cells is similar, albeit with a slight lag because of its larger size. However, few studies have focused on the time course of gentamicin uptake in the cochlea after intratympanic gentamicin injection. We injected GTTR intratympanically and obtained the time course of GTTR fluorescence intensity in outer hair cells (OHCs). Based on our preliminary data, we then applied low-dose titration gentamicin injection to treat patients with intractable MD. Treatment was terminated if signs of vestibular hypofunction were detected. The purpose of this study was to define a better injection protocol based on our outcomes in GPs and to evaluate the safety and efficacy of this modified intratympanic gentamicin injection scheme on patients with intractable MD.

MATERIALS, METHODS, AND RESULTS OF GP STUDIES

Materials and Methods

Agent Preparation

Purified GTTR was dissolved in 1 ml dimethyl sulfoxide (1 µg/ml), centrifuged at the temperature of 10°C (10 min, 12,000 r/min), and stored in the dark at −20°C. Texas Red (2.5 mg) was dissolved in 1 ml dimethyl sulfoxide, centrifuged, and stored as for purified GTTR. Phallodin-Alexa-488 (1 µl; Molecular Probes, OR, USA) was dissolved in 200 µL 0.02 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and prepared just before the experiment.

Animals

Albino GPs weighing 200 to 250 g with normal Preyer reflexes were used. Animals were divided into 2 major groups. Group I: 50 µl purified GTTR solution was injected intratympanically. GPs were allowed to survive for 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, respectively, with 8 animals processed at each posttreatment recovery time. Group II (negative control): 8 GPs were injected intratympanically with Texas Red (50 µl). Control animals were killed 3 days after injection. All animals were provided by the Animal Care Centre of Eye Ear Nose and Throat Hospital affiliated with Fudan University. This study was approved by the animal care committee of Fudan University.

Surgical Procedures

GPs were anesthetized with intramuscular ketamine 70 mg/kg and xylazine 7 mg/kg (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, St. Joseph, MO, USA). Animals were placed on their left side with their right ears turned toward the operating microscope. A hole in the anterior superior part of the tympanic membrane was punctured for venting. Then, 50 µl solutions (GTTR, Texas Red, or vehicle) were slowly micro-injected into the tympanic cavity through another hole in the posterior part of the tympanic membrane. After injection, the animals remained in the surgical position for at least 30 minutes, and their body temperatures maintained at 37°C with warm blankets.

Tissue Preparation and Confocal Microscopy

At each time point, GPs were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of 2.5 mg/kg intramuscular urethane; the inner ears were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The 3 turns of the cochlea were excised. Specimens were washed 3 times in 0.1 mol/L PBS, immersed in acetone for 1 hour, rinsed 3 times in PBS, and incubated with Alexa-488–conjugated phalloidin for 1 hour. After rinsing with PBS, the specimens were mounted on glass slides, coverslipped, and scanned under a Leica confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). All confocal image acquisition settings were identical and imaged during the same imaging sessions.

Comparisons and Statistics

The distribution and fluorescent intensity of GTTR in cochlear hair cells were obtained. Means and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence intensity among different groups was analyzed using 1-way analysis of variance and multiple comparison with the help of SPSS 11.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Specificity of GTTR Fluorescence

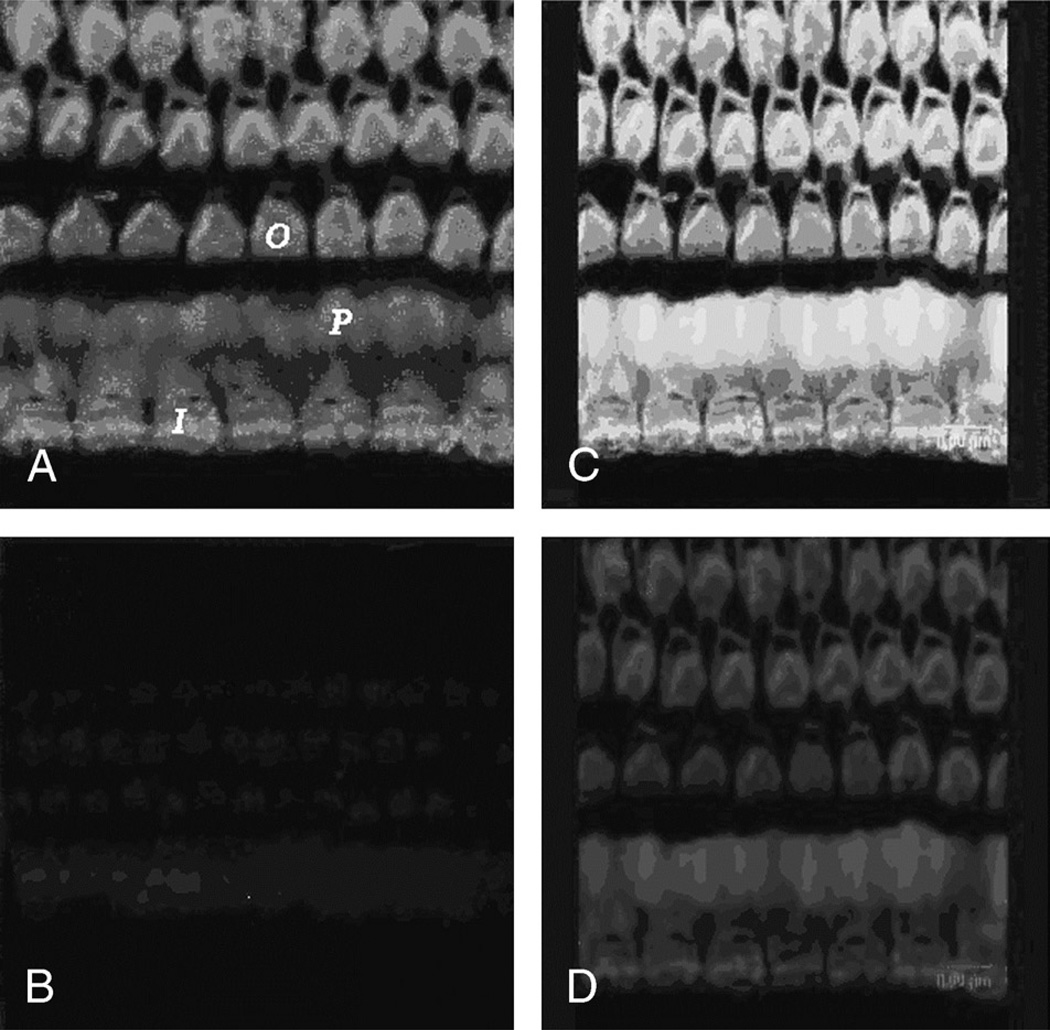

Cochlear surface preparations from control groups were imaged using the same confocal acquisition settings as for surface preparations from the experimental group contemporaneously treated with GTTR. When 50 µl free Texas Red was injected into the tympanic cavity, Alexa-488-phalloidin–labeled OHCs did not display Texas Red fluorescence (Fig. 1,A and B).When 50 µl GTTR was injected, OHCs displayed both GTTR and Alexa-488 fluorescence (Fig. 1, C and D), demonstrating that Texas Red fluorescence in cochleae treated with GTTR is representative of GTTR localization.

FIG. 1.

A, Alexa-488-phalloidin labeling in the stereocilia and cuticular plates of OHCs (O) and IHCs (I) and in the inner pillar cell phalange(P). B, Negligible Texas Red fluorescence in the cochlea. Tissue prepared for Figure 1, A and B, was treated with Texas Red only. C, Surface preparation from an animal treated with intratympanic injection of GTTR. Alexa-488-phalloidin labeling in the stereocilia and cuticular plates of OHCs and IHCs and in the inner pillar cell phalange. D, GTTR fluorescence was observed in the stereocilia and cuticular plates of OHCs and IHCs, and in the inner pillar cell phalange.

Distribution of GTTR in the OHCs of the Organ of Corti

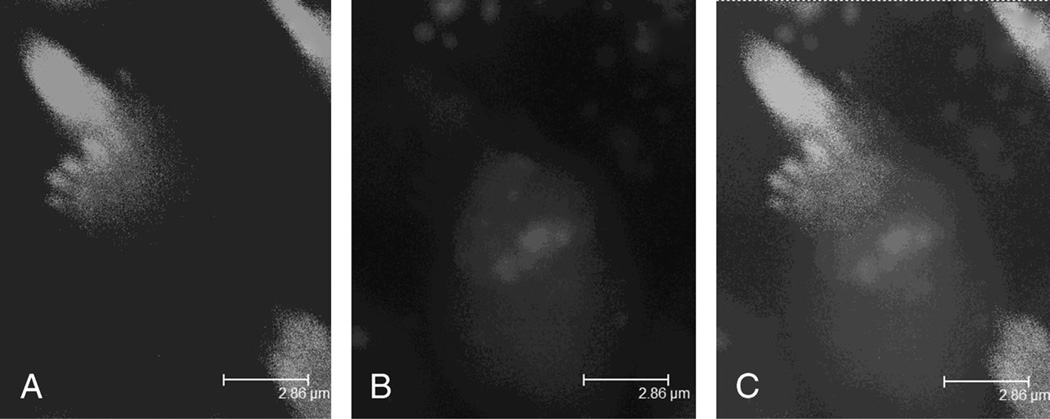

The distribution of GTTR in the OHCs exhibited a decreasing baso-apical gradient. GTTR was distributed in the stereocilia and cuticular plates of OHCs and IHCs and in the inner pillar cell phalange. GTTR fluorescence was prevalent in the cuticular plate, diffuse in the infracuticular cytoplasm, and punctate within the rest of the cytoplasm (Fig. 2, A–C).

FIG. 2.

Gentamicin uptake in anOHC3 days after injection. A, Alexa-488-phalloidin labeling of individual stereocilia can be observed. B, At the same focal plane, GTTR fluorescence was prevalent in the cuticular plate, diffuse in the infracuticular cytoplasm, and punctate within the rest part of the cytoplasm. C, Merged color image of A and B.

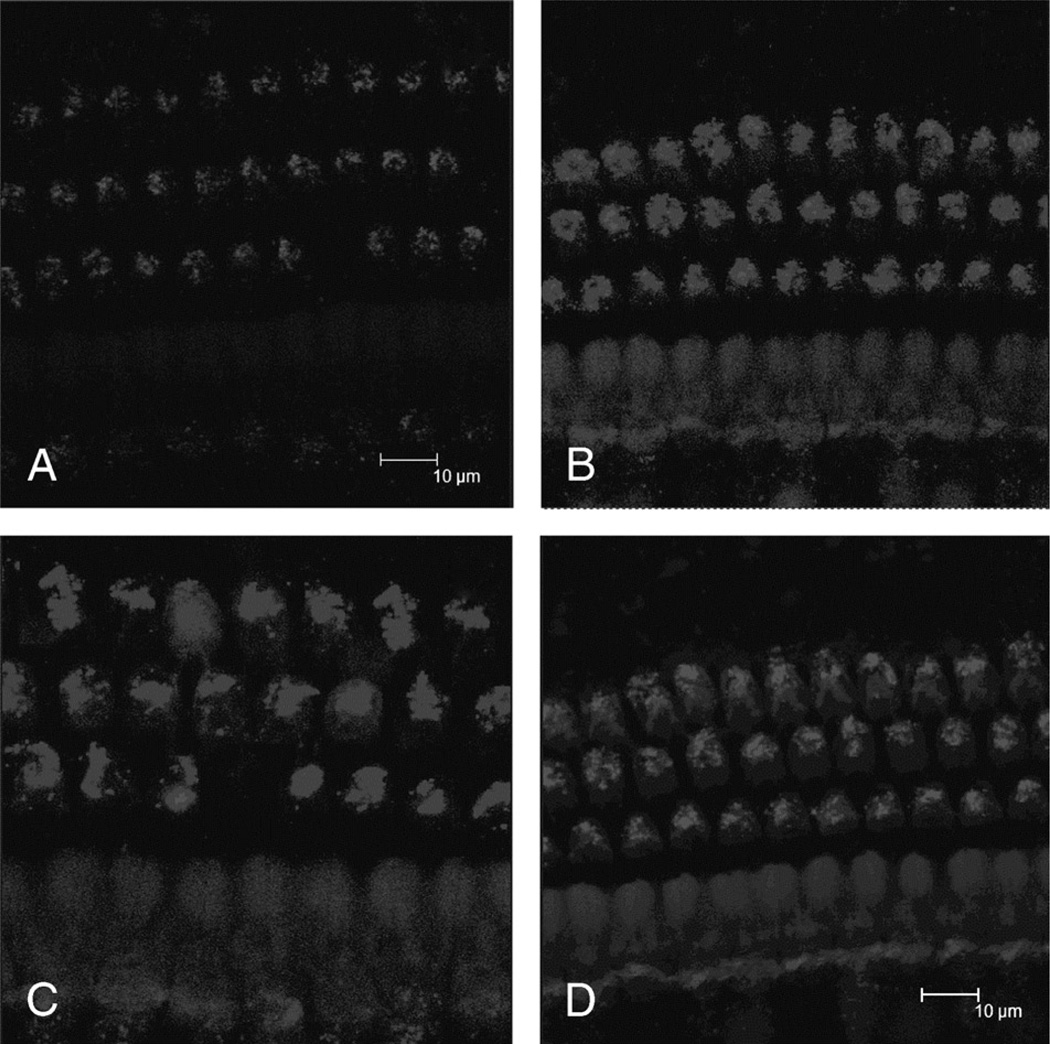

Intensity of GTTR Fluorescence in OHCs Over Time

The intensity of GTTR fluorescence in OHCs at different time points after intratympanic GTTR injection was documented. One day after injection, only weak fluorescence was observed in OHCs (Fig. 3A). One week later, more intense fluorescence was present in OHCs (Fig. 3B). Two and 3 weeks after injection, GTTR fluorescence was still present in OHCs. The intensity of GTTR fluorescence in OHCs did not show statistically significant difference when compared between animals from 1-, 2-, or 3-week survival time points after injection (p > 0.05; Fig. 3, C and D).

FIG. 3.

GTTR fluorescence intensity in OHCS (A) 24 hours, (B) 7 days, (C) 14 days, and (D) 21 days after intratympanic injection. GTTR fluorescence intensity was not significantly different in OHCs 1, 2, and 3 weeks after injection.

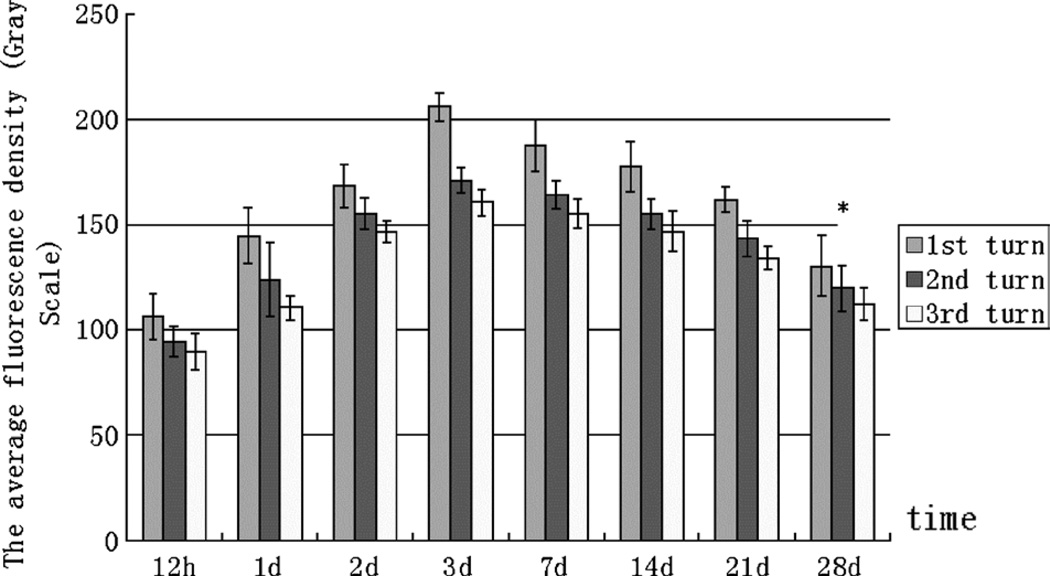

As Figure 4 demonstrates, GTTR fluorescence gradually increased in OHCs from 12 hours to 3 days after injection, which had the most intense fluorescence in OHCs. From 3 days to 3 weeks after injection, the intensity of GTTR fluorescence in OHCs decreased slightly, but this decline was not statistically significant in all the 3 turns (p > 0.05; Fig. 4). Only 4 weeks after injection (marked by an asterisk) did OHCs show an apparently statistically significant decline in fluorescence intensity in all the 3 turns (p > 0.05; Fig. 4). The thickness of the organ of Corti seemed to remain unchanged, which indicated that the dose used exerted minimal, if any, cochleotoxicity (Fig. 3, A–D), unlike that described for vestibular organs (15,16).

FIG. 4.

Average intensity of GTTR fluorescence in OHCs. GTTR fluorescence gradually increased in OHCs until 3 days after injection, when it was at its most intense. From 3 days to 3 weeks after injection, the apparent decline in intensity of GTTR fluorescence in OHCs was not statistically significant. At 28 days after the injection, OHCs had a statistically significant decline in GTTR fluorescence compared with 3 days (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

One method to treat intractable unilateral MD is to minimize the frequency and severity of vertigo spells by ablating vestibular hair cells using intratympanic injection of gentamicin. Gentamicin is considered to have greater vestibulotoxicity compared with cochleotoxicity (22), which may be partially due to the more positive endocochlear potential (+80 mV) within cochlear endolymph providing greater electrorepulsion of the positively charged gentamicin.

The ototoxic damage that gentamicin has on vestibular and cochlear HCs is dose dependent. Okuda et al. (12) concluded in 2004 that the GPs treated with low gentamicin concentrations (4 mg/ml) showed no obvious change in either vestibular or cochlear function. A moderate concentration (12 mg/ml) caused only a partial damage to the inner ear and 40 mg/ml gentamicin severely damaged both the vestibular and the cochlear end organs. These studies indicate that further studies regarding the best concentration of gentamicin to relieve vertigo with minimal damage in the cochlea is still required.

Gentamicin Distribution

In this study, after intratympanic injection, GTTR fluorescence was observed in OHCs in a decreasing basoapical gradient. Plontke et al. (23) demonstrated, in 2007, substantial gradients of gentamicin along the length of the perilymphatic scala tympani, with 4,000-fold greater concentrations of gentamicin at the base 3 hours after local application to the round window niche. They also found that peak concentrations and gradients for gentamicin varied greatly between animals that may result from variations in round window membrane permeability and rates of perilymph flow (23). It is suggested that the variability in perilymphatic gradients might explain the variability in clinical results (especially adverse outcomes) after intratympanic gentamicin therapy.

Within OHCs, GTTR was localized in the cuticular plate and infracuticular regions consistent with previous studies (16,18). Meyer et al. (24) suggested that the infracuticular zone, namely Hensen’s body, was a specialized site in OHCs for membrane degradation and turnover. Aminoglycosides are known to enter hair cells via apical endocytosis or stereociliary transduction channels (25,26). Endocytotic uptake of aminoglycosides likely follows the lysosomal degradation pathway (27). The extremely long retention of aminoglycosides in OHCs (>4 wk) reported before (28,29) suggests that gentamicin may be sequestered here, and perhaps gentamicin-induced ototoxicity might therefore be reduced. Hashino et al. (27), in 1997, have hypothesized that aminoglycosideladen lysosomes may undergo lysis that subsequently induces hair cell death.

Time Course of Gentamicin Within Cochlear Hair Cells

Previous studies vary with regard to the time course of gentamicin uptake after injections intratympanically. Imamura and Adams (18) observed that diffuse staining was present at 12 hours and beyond. Gradually, the cytoplasmic staining diminished with increasing survival times, but apical staining of OHCs was present in animals for as long as 6 months. Hibi et al. (19) observed in 2001 that gentamicin concentrations within the perilymph near the round window reached its maximum within 100 minutes after administration intratympanically and declined at a half-life of 309 ± 95 minutes as determined by a microdialysis technique.

In the present study, we observed the time course of GTTR fluorescence in OHCs after intratympanic GTTR injection. The most intense labeling was observed 3 days after injection, and the intensity of GTTR fluorescence remained almost constant during the next 3 weeks. Only 4 weeks after injection did the OHCs show a significant decline in fluorescence intensity compared with that observed after 3 days. These results, together with former studies, indicate an initial period of gentamicin uptake over 3 days, followed by a long period of elimination by the hair cells (17,18). Gentamicin injected intratympanically enters perilymph in the scala tympani via the round window and is removed by passive diffusion and by active elimination mechanisms such as blood flow and lymphatic flow (19). It is rather easy for positive-charged gentamicin to permeate into perilymph that has a low electrical potential. However, aminoglycoside elimination from perilymph is a long-lasting process for gentamicin as blood and lymphatic flow within cochlea is relatively slow (19). Consequently, a daily or weekly dosing regimen of intratympanic gentamicin injections may result in high risks of cochleotoxicity. Because the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin is more rapid than that for GTTR (21), we assumed that a 3-week interval between each injection might reduce the risk of cochleotoxicity.

CONCLUSION OF ANIMAL STUDY

After intratympanic injection, GTTR was taken up by OHCs in a decreasing baso-apical gradient in the cochlea. GTTR was observed in OHCs at 12 hours after injection and was retained for almost 21 days without apparent decline. In OHCs, GTTR was primarily localized in the infracuticular regions.

CLINICAL APPLICATION

Materials, Methods, and Results of Patient Studies

Patients

Nineteen patients with unilateral intractable vertigo were enrolled form June 2003 to December 2004 at Otolaryngology department of Fudan University. There were 13 male and 6 female subjects with an average age of 45 years (range, 17–65 yr). The diagnosis of MD was made according to the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Diagnostic Criteria (30). The details of vertigo attacks and concomitant symptoms (tinnitus, hearing loss, and ear fullness) of all patients were recorded. Pure-tone audiometry (PTA) results were obtained from the average threshold of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 kHz.Acaloric test was conducted to evaluate the vestibular function. The criteria for patient inclusion into the present study were as follows: 1) Each patient had already received medical treatment with low salt diet, beta-histine, or diuretics for at least 1 year without any improvement. 2) The hearing and vestibular function (caloric test) of the contralateral unaffected ear in all patients were normal. 3) There was no central nervous system abnormality detected. 4) Neurological examination and temporal bone CT scan of patients revealed no distinguishing abnormalities.

The left ear was affected in 11 patients and the right in 8. The patients had experienced symptoms of unilateral MD for an average of 4.5 years. All patients complained of vertigo and hearing loss (PTA results: mean, 70 dB), whereas only 14 patients presented with tinnitus and 10 patients complained of ear fullness. Caloric test demonstrated that 14 patients have normal results, and abnormal results were identified in 5 patients.

Procedures

Gentamicin sulfate (40 mg/ml) was buffered with sodium bicarbonate to pH 6.4 to reach a final concentration of 30 mg/ml. Under the microscope, patients were placed in a supine position with their heads turned 45 degrees to the unaffected ear. Topical anesthesia with 1% Dicaine was administered. Approximately 0.5 ml GT was delivered to the middle cavity with 26-gauge syringe. After the injection, the patients remained in the surgical position for at least 30 minutes. All patients were instructed not to eat or drink or speak for 30 to 45 minutes after injection to prevent solution drainage through the Eustachian tube. Based on the results from our GP study, patients were followed for 3 weeks to determine whether additional injections were needed and to assess ototoxicity to the vestibule and cochlea. Additional injections were judged to be unnecessary if signs of vestibular hypofunction appeared (i.e., spontaneous nystagmus and positive head shake test or head thrust test) or obvious symptom relief was obtained. A second injection was not given if the hearing threshold increased by 10 dB.

All subjects were followed for at least 2 years. The first follow-up occurred within 3 weeks after injection. If vertigo was controlled, patients were asked to return 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after injection. Each follow-up obtained the following information regarding vertigo relapse, nystagmus (spontaneous nystagmus and head shake and head thrust tests), and the PTA results.

Results

Vertigo control was achieved in 16 (84%) of 19 patients. Results revealed complete control of vertigo spells in 12 patients (63%; Class A of American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery criteria), good control in 4 patients (21%; Class B) and moderate control in 1 patient (5%;Class C). Five patients (26%) received 1 injection, 8 patients (42%) received 2 injections (1 patient asked for endolymphatic sac decompression because of ear fullness), and 4 patients (21%) underwent 3 injections. Vertigo recurrence was noted in 4 patients (24%); however, vertigo spells were less frequent and severe.

Posttreatment PTA threshold was 75 dB on average, compared with 70 dB before treatment. Only 3 patients (16%) complained of significant increase in hearing thresholds (>10 dB). Hearing function was stable in 14 patients (74%), and improved hearing thresholds were identified in 2 patients (11%) (>10-dB hearing threshold decrease). Tinnitus was resolved in 1 patient (5%), and 3 patients (16%) reported relief of tinnitus; however, tinnitus remained in 10 patients (53%). One patient (5%) complained of a worsening of ear fullness (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The clinical presentation of the patients treated intratympanically with gentamicin

| Hearing loss | Vertigo | Tinnitus | Ear fullness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | 19 | 19 | 14 (74%) | 10 (53%) |

| Posttreatment | ||||

| Better | 2 (11%) | 17 (89%) | 4 (21%) | |

| Same | 14 (74%) | 2 (11%) | 10 (53%) | 9 (48%) |

| Worse | 3 (16%) | 1 (5%) |

Four patients experienced dizziness in the first month after gentamicin injection. One patient (65 years old) complained of moderate imbalance within 6 months after gentamicin injection, which resulted in limitation of his daily activity.

DISCUSSION

The appropriate concentration of gentamicin in the inner ear may be determined from the frequency, dose, delivery methods, and end point of gentamicin injections. Chia et al. (14), in 2004, divided the dosing regimen into 5 different categories: multiple daily dosing technique (delivery, 3 times per day for more than 4 days), weekly dosing technique (weekly injections for 4 total doses), low-dose technique (1–2 injections with retreatment for recurrent vertigo), and continuous microcatheter delivery and titration technique (daily or weekly doses until onset of vestibular symptoms, change in vertigo, or hearing loss). They made a comprehensive comparison of these techniques by way of meta-analysis and found that the titration technique had the best vertigo control (96.3%) with a moderate rate of hearing loss (24.2%). The weekly technique yielded the lowest hearing loss rate (13.1%), and the low-dose technique also demonstrated a relatively low chance of hearing loss (23.7%). It is widely agreed that longer intervals of injection may turn out to be more effective in minimizing hearing loss, whereas obtaining consistent vertigo control, which seems to be a good trade-off. Sala (5) used an interval of 2 to 4 days. Atlas and Parnes (31) gave 4 intratympanic gentamicin injections by serial titration to the treated ear on a weekly schedule unless the patients met clinical or audiologic criteria. Minor (32) suggested weekly intervals of intratympanic gentamicin until signs of vestibular hypofunction developed. All these studies obtained excellent vertigo control (86%–90%), and relatively low hearing loss rates (8%–19%), which have provided general insights into optimal dosing intervals that may minimize hearing loss. Our GTTR study using GPs further support this view with compelling evidence that intratympanic injection of aminoglycosides results in rapid uptake and slow elimination by cochlear OHCs.

These studies suggested to us that increasing the time interval between ITGent injections to 3 weeks would still control vertigo effectively while decreasing the likelihood of ototoxic damage to hearing. In this study, we used a low-dose and long-interval titration of gentamicin injection to treat patients with intractable MD, that is, 1 injection, with an interval of 3 weeks to determine whether an additional injection was needed. The 3-week interval was determined from our animal study, which indicated that strong GTTR labeling in the OHCs remained for 3 weeks without significant reduction after 1 intratympanic GTTR injection. During that time, if another intratympanic GTTR injection had been given, it was very likely that GTTR fluorescence would have increased significantly in OHCs. Because GTTR has longer pharmacokinetics than gentamicin (21), we postulate that a subsequent clinical intratympanic injection should occur after an interval of 3 weeks to minimize the gentamicin uptake by OHCs. This will reduce the incidence of hearing loss after intratympanic gentamicin injection in clinical practice. In addition, during the 3-week observation period, the treatment should be stopped if signs of vestibular hypofunction (spontaneous nystagmus and positive results of head shake test or head thrust test), hearing loss (>10 dB), and obvious symptom relief occur.

As is shown in Table 1, after 2 years of following up, we have achieved complete vertigo control (Class A) in 63% of our patients and substantial (Class B) in 21%. This result is comparable to previous results of intratympanic gentamicin injection (4). Furthermore, our result is also comparable to vestibular neurectomy in vertigo control (33). This demonstrates that our long-term and low-dose intratympanic gentamicin injection protocol is as efficacious in controlling vertigo as other dosing regimens and vestibular nerve section. However, the vertigo control rate is lower than that of multiple daily (34), weekly dosing (31), and daily or weekly titration techniques (32). We believe that the relatively lower rate is due to the smaller total dose of gentamicin delivered to the inner ear.

Our study reported a low probability of hearing loss (16%), and no patients developed total hearing loss. This result is consistent with previous low-dose or long-interval (weekly or biweekly) injections (5,10,31). We therefore conclude that a long interval of 3 weeks or more can reduce the possibility of hearing loss. However, how long the interval should be to obtain an excellent vertigo control rate and the minimal hearing loss rate still entails further large sample, double-blind, and randomly controlled studies, in addition to further, more fundamental, animal tests.

In the present study, 4 patients experienced dizziness within the first month after gentamicin injection. We thought that this phenomenon was directly associated with vestibular function suppression, and as time went by, the dizziness resolved spontaneously. Another patient (65 years old) complained of moderate imbalance within 6 months after gentamicin injection, which led to limitation of activities in his daily life. Odkvist et al. (35) held the opinion that elderly people were more likely to undergo long-term and incomplete vestibular rehabilitation. If the dosing protocol was not appropriate, they may experience vestibular hypofunction and consequent difficulty in everyday life. Thus, caution is required when treating patients older than 60 years.

Since 1977, chemical labyrinthectomy has always used gentamicin rather than streptomycin, and the end point of treatment was redefined. Symptoms and signs associated with inner ear dysfunction (i.e., disequilibrium, motion intolerance, ataxia, and nystagmus) have become the clinical criteria for determining the end point (30,36). Minor (32) established the method of ending weekly intratympanic gentamicin injections when clinical signs of unilateral vestibular hypofunction appear. Those signs included spontaneous nystagmus, head shaking–induced nystagmus and head thrust–induced nystagmus. Our study has provided 2 other signs: hearing loss and obvious symptom relief. However, determination of the most appropriate end point still needs to be defined.

CONCLUSION

With our modified titration technique, vertigo control was achieved in 89% of patients, with hearing deterioration occurring in only 16% of patients. Low-dose intratympanic gentamicin titration injection was effective in controlling vertigo while minimizing cochleotoxicity and hearing loss. Furthermore, this protocol is more cost effective than traditional surgical procedures, and if it fails, patients can still undergo surgery. Caution should be taken while performing gentamicin injection in patients older than 60 years.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jie Tian and Cuidi Da for technical assistance with the cochlear surface preparation and image collection in this study.

This study was supported by Science and Technology Ministry of China “Tenth Five” Tackling Key Project Fund (No. 2004BA702B04 [C. F. D.]), Educational Ministry of China (NCET-06-0369 [C. F. D.]), National Natural Science Foundation (Nos. 30772398 [C. F. D.] and 30600704 [J. P. L.]), and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC004555 [P. S. S.]).

REFERENCES

- 1.Yazdi AK, Rutka J. Results of labyrinthectomy in the treatment of Ménière’s disease and delayed endolymphatic hydrops. J Otolaryngol. 1996;25:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gacek RR, Gacek MR. Comparison of labyrinthectomy and vestibular neurectomyin the control of vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:225–230. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199602000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen-Kerem R, Kisilevsky V, Einarson TR, Kozer E, Koren G, Rutka JA. Intratympanic gentamicin for Ménière’s disease: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:2085–2091. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000149439.43478.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefano AD, Dispenza F, Donato GD, Caruso A, Taibah A, Sanna M. Intratympanic gentamicin: a 1-day protocol treatment for unilateral Ménière’s disease. Am J Otolaryngol Head Neck Med Surg. 2007;28:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sala T. Transtympanic gentamicin in the treatment of Ménière’s disease. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1997;24:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(97)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer PW, MacDonald CB, Cox LC. Intratympanic gentamicin therapy for vertigo in nonserviceable ears. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:111–115. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2001.22569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casani A, Nuti D, Franceschini SS, Gaudini E, Dallan I. Transtympanic gentamicin and fibrin tissue adhesive for treatment of unilateral Ménière’s disease: effects on vestibular function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driscoll CLW, Kasperbauer JL, Facer GW, et al. Low-dose intratympanic gentamicin and the treatment of Ménière’s disease: preliminary results. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:83–89. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199701000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauch SD, Oas JG. Intratympanic gentamicin for treatment of intractable Ménière’s disease: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:49–55. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199701000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu IC, Minor LB. Long-term hearing outcome in patients receiving intratympanic gentamicin for Ménière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:815–820. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura RS, Lee KS, Nye CL, Trehey JA. Effects of systemic and lateral semicircular canal administration of aminoglycosides on normal and hydropic inner ears. Acta Otolaryngol. 1991;111:1021–1030. doi: 10.3109/00016489109100751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okuda T, Sugahara K, Shimogori H, Yamashita H. Inner ear changes with intracochlear gentamicin administration in guinea pigs. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:694–697. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200404000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harner SG, Driscoll CL, Facer GW, Beatty CW, McDonald TJ. Long-term follow-up of transtympanic gentamicin for Ménière’s syndrome. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:210–214. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200103000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chia SH, Gamst AC, Anderson JP, Harris JP. Intratympanic gentamicin therapy for Ménière’s disease: a meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:544–552. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200407000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steyger PS, Peters SL, Rehling J, Hordichok A, Dai CF. Uptake of gentamicin by bullfrog saccular hair cells in vitro. JARO. 2003;4:565–578. doi: 10.1007/s10162-003-4002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyford-Pike S, Vogelheim C, Chu E, Santina CCD, Carey JP. Gentamicin is primarily localized in vestibular type I hair cells after intratympanic administration. JARO. 2007;8:497–508. doi: 10.1007/s10162-007-0093-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roehm P, Hoffer M, Balaban CD. Gentamicin uptake in the chinchilla inner ear. Hearing Research. 2007;230:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imamura S, Adams JC. Distribution of gentamicin in the guinea pig inner ear after local or systemic application. JARO. 2003;4:176–195. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-2036-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hibi T, Suzuki T, Nakashima T. Perilymphatic concentration of gentamicin administered intratympanically in guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:336–341. doi: 10.1080/000164801300102699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunting EC, Park DL, Durham D, Girod DA. Gentamicin pharmacokinetics in the chicken inner ear. JARO. 2004;5:144–152. doi: 10.1007/s10162-003-4033-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Q, Steyger PS. Trafficking of systemic fluorescent gentamicin into the cochlea and hair cells. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2009;10:205–219. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0160-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura RS, Lee KS, Nye CL, Trehey JA. Effects of systemic and lateral semicircular canal administration of aminoglycosides on normal and hydropic inner ears. Acta Otolaryngol. 1991;111:1021–1030. doi: 10.3109/00016489109100751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plontke SK, Mynatt R, Gill RM, Borgmann S, Salt AN. Concentration gradient along the scala tympani after local application of gentamicin to the round window membrane. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318058a06b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer J, Mack AL, Gummer AW. Pronounced infracuticular endocytosis in mammalian outer hair cells. Hear Res. 2001;161:10–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashino E, Shero M. Endocytosis of aminoglycoside antibiotics in sensory hair cells. Brain Res. 1995;704:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangiardi D, Cotanche DA. Mechanisms of aminoglycoside induced hair cell death. The Volta Review. 2005;105:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashino E, Shero M, Salvi RJ. Lysosomal targeting and accumulation of aminoglycoside antibiotics in sensory hair cells. Brain Res. 1997;777:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00977-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiel H, Bennani H, Erre J, Aurousseau C, Aran J. Kinetics of gentamicin in cochlear hair cells after chronic treatment. Acta Otolaryngol. 1992a;112:272–277. doi: 10.1080/00016489.1992.11665417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dulon D, Hiel H, Aurousseau C, Erre JP, Aran JM. Pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in the sensory hair cells of the organ of Corti: rapid uptake and long term persistence. C R Acad Sci III. 1993;316:682–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium. Guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of Ménière’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Sur. 1995;113:181–185. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atlas JT, Parnes LS. Intratympanic gentamicin titration therapy for intractable Ménière’s disease. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minor LB. Intratympanic gentamicin for control of vertigo in Ménière’s disease: vestibular signs that specify completion of therapy. Am J Otol. 1999;20:209–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid CB, Eisenberg R, Halmagyi GM, Fagan PA. The outcome of vestibular nerve section for intractable vertigo: the patient’s point of view. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1553–1556. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199612000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan DM, Nedzelski JM, Chen JM, Shipp DB. Intratympanic gentamicin for the treatment of unilateral Ménière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 2000;2000:1298–1305. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200008000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Odkvist LM, Bergenius J, Möller C. When and how to use gentamicin in the treatment of Ménière’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1997;526:54–57. doi: 10.3109/00016489709124023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffer ME, Allen K, Kopke RD, Weisskopf P, Gottshall K, Wester D. Transtympanic versus sustained-release administration of gentamicin: kinetics, morphology, and function. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1343–1345. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]