Abstract

Background

Phosphorus (P) plays important roles in plant growth and development. MicroRNAs involved in P signaling have been identified in Arabidopsis and rice, but P-responsive microRNAs and their targets in soybean leaves and roots are poorly understood.

Results

Using high-throughput sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology, we sequenced four small RNA libraries from leaves and roots grown under phosphate (Pi)-sufficient (+Pi) and Pi-depleted (-Pi) conditions, respectively, and one RNA degradome library from Pi-depleted roots at the genome-wide level. Each library generated ∼21.45−28.63 million short sequences, resulting in ∼20.56−27.08 million clean reads. From those sequences, a total of 126 miRNAs, with 154 gene targets were computationally predicted. This included 92 new miRNA candidates with 20-23 nucleotides that were perfectly matched to the Glycine max genome 1.0, 70 of which belong to 21 miRNA families and the remaining 22 miRNA unassigned into any existing miRNA family in miRBase 18.0. Under both +Pi and -Pi conditions, 112 of 126 total miRNAs (89%) were expressed in both leaves and roots. Under +Pi conditions, 12 leaf- and 2 root-specific miRNAs were detected; while under -Pi conditions, 10 leaf- and 4 root-specific miRNAs were identified. Collectively, 25 miRNAs were induced and 11 miRNAs were repressed by Pi starvation in soybean. Then, stem-loop real-time PCR confirmed expression of four selected P-responsive miRNAs, and RLM-5’ RACE confirmed that a PHO2 and GmPT5, a kelch-domain containing protein, and a Myb transcription factor, respectively are targets of miR399, miR2111, and miR159e-3p. Finally, P-responsive cis-elements in the promoter regions of soybean miRNA genes were analyzed at the genome-wide scale.

Conclusions

Leaf- and root-specific miRNAs, and P-responsive miRNAs in soybean were identified genome-wide. A total of 154 target genes of miRNAs were predicted via degradome sequencing and computational analyses. The targets of miR399, miR2111, and miR159e-3p were confirmed. Taken together, our study implies the important roles of miRNAs in P signaling and provides clues for deciphering the functions for microRNA/target modules in soybean.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Soybean, Phosphorus, Root, Leaf, Genome, Degradome, RLM-5’ RACE, Deep sequencing

Background

Non-coding small RNAs can be grouped into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNA) in plants [1]. SiRNAs consist of trans-acting siRNA(ta-siRNA), natural antisense transcript-derived siRNA(nat-siRNA), and repeat associated siRNA (ra-siRNA) [1]. Increasing evidences verify that 20–24 nucleotide-long miRNAs play important roles in growth, development, and stress adaptations in planta via modulating gene activity [1,2]. In the plant cell, primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) is transcribed by RNA polymerase II (PolII) [3], then cut to precursor of miRNA (pre-miRNA) containing the distinctive stem-loop structure by Dicer-like (DCL), and finally pre-miRNA is processed to form miRNA/miRNA* duplexes, with miRNA* ultimately degraded [1,4]. Hua Enhancer 1 (HEN1) methylates the miRNA/miRNA* duplex on the 3’terminal nucleotide of each strand to protect it from degradation by other small exonucleases. The methylated duplex is transported into the cytoplasm with the help of HASTY (HST) [1] and recruited by ARGONAUTE (AGO) proteins to suppress translation or to cleave the target transcripts mostly in the coding region [1].

Like DCLs, AGOs are highly conserved proteins across plants and animals. In Arabidopsis, ten genes encode AGO, which are grouped into 4 clades [1,5]. AGO1 is involved in most miRNA biogenesis. AGO4 and AGO6 are responsible for ra-siRNA production and control DNA methylation. AGO7 participates in ta-siRNA formation [5]. Recent studies showed that the 5’ terminal nucleotide appears to determine the fate of miRNAs. For instance, AGO1 preferentially binds miRNAs with a 5’ terminal uridine (U), and AGO2 and AGO4 recruit small RNAs with 5’ terminal adenosine (A), AGO5 binds small RNAs that terminate with cytosine (C) at the 5’ terminus [5].

Recently, a number of miRNAs have been documented to be involved in nutrient signaling. Phosphorus (P) deficiency specifically induces miR399 in Arabidopsis and rice [6-8]. MiR827 induced by P limitation negatively regulates the transcript level of NITROGEN LIMITATION ADAPTATION (NLA) in Arabidopsis. Plus, osa-miR827 expression is strongly enhanced by phosphate (Pi) starvation in both roots and leaves. In situ hybridization indicates that osa-miR827 is expressed in mesophyll, epidermis and ground tissues of roots. Moreover osa-miR827 relays P signaling via negatively regulating the target genes of OsSPX-MFS1 and OsSPX-MFS2 [9]. More ambiguous results pertaining to miRNA involvement in P deprivation was obtained with the observation through RNA ligase mediated 5’rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-5’ RACE) that miR2111 cleaves At3g27150, which encodes a kelch domain-containing F-box protein, but Pi starvation induced the levels of both miR2111 and At3g27150[10]. One last set of results in regards to P nutrition shows that miR778, miR398, miR169 and miR408 are also responsive to P limitation [10,11]. In regards to other nutrients, miR167 and miR393 were found to regulate root development in response to nitrogen (N) [12,13]. Sulphur (S) starvation stimulated miR395, which targets plastidic ATP sulfurylase (APS), and the high-affinity sulfate transporter SULTR2;1 [6,12,14]. Copper (Cu) limitation stimulates the level of miR398 and miR402 [6,15,16]. Once expressed, miRNAs can be transported in phloem but not xylem vessels [12]. The levels of miR395, miR398 and miR399 were strongly augmented in response to S, Cu or Pi starvation in phloem. Under iron (Fe) deficiency, while the levels of miR399 and miR2111 were decreased in phloem, and even undetectable in roots and leaves [12,16], indicating that Fe limitation alters P homeostasis.

The first study on soybean miRNAs in 2008 identified 35 novel miRNA families [17], and then sixty-nine miRNAs grouped into 33 families and their targets were determined through computational analysis [18]. After that, eighty-seven novel miRNAs were further isolated from soybean roots, seeds, flowers and nodules [19]. Twenty-six new miRNAs were identified via small RNA and degradome-associated deep sequencing in soybean seeds [20]. In addition, mis-expressions of miR482, miR1512, and miR1515 in soybean increased nodulation [21].

Low P availability resulting from its low mobility in soils is a common limiting factor for soybean yield [22]. Although miR399, the classic P-responsive miRNA, was predicted to exist in soybean [18], no experiments to verify the existence of this or other P-responsive mRNAs have been reported in soybean. To identify P-responsive miRNAs, along with, leaf- and root-specific miRNAs in soybean, in this study we sequenced four small RNA libraries from soybean leaves and roots grown under Pi-sufficient (+Pi) and Pi-depleted (-Pi) conditions, respectively. From those libraries, new conserved, less-conserved, and novel miRNAs as well as P-responsive miRNAs in soybean leaves and roots were identified genome-wide. Furthermore the targets of soybean miRNAs were determined via degradome sequencing from -Pi-roots combined with computational analyses. Finally, the existence of four P-responsive miRNAs (miR399, nov_6, nov_9, and nov_10) were verified via stem-loop real time (RT) PCR, and the targets of miR399, miR2111, and miR159e-3p were confirmed via RLM 5’ RACE. With results in hand, the possible functions of miRNA/target modules are discussed.

Results

Deep sequencing of small RNAs in soybean leaves and roots

Relative to control plants, long-term (7 days or 14 days) Pi starvation increased the ratio of roots to shoots (Additional file 1A), and decreased the concentration of soluble phosphate (SPi) in leaves and roots (Additional file 1B). Pi limitation globally induces the expression of many genes, including AtIPS1 (At3g09922) a well known non-coding Pi-starvation responsive gene, and AtPLDZ2 (At3g05630), which is involved in the conversion of phospholipid to glycolipid and free P [7]. Based on Blast searches of these genes in Phytozome ( http://www.phytozome.org) and TIGR ( http://www.tigr.org), the sequences of GmIPS1 and GmPLDZ2 were retrieved. The transcript levels of GmPLDZ2 (Additional file 1C) and GmIPS1 (Additional file 1D) were induced by long-term Pi deprivation. These data verified that the Pi starvation in soybean was affected at both physiological and molecular levels.

Additional file 1 indicated that soybean was subjected to Pi starvation at 6 h, 12 h, 7 d and 14 d treatments. Accordingly, the 6 h and 12 h Pi starvation were treated as short-term P limitation, and 7 d and 14 d as long-term P stress. To augment the chance of finding more miRNAs in a single sequencing run, total RNA was extracted from leaves and roots of both +Pi and -Pi plants at 6 h, 12 h, 7 d, and 14 d, and then equal amounts of total RNA from each time point and treatment were pooled and used to construct four small RNA libraries labeled as leaf+Pi (HPL), root+Pi (HPR), leaf-Pi (LPL) and root-Pi (LPR).

Overall, more than 20 million raw reads from the four small RNA libraries were obtained. Clean reads were produced by excluding reads smaller than 18 nt and adaptors. The percentage of clean reads to total reads ranged from 96.92% to 99.59% (Table 1). More than 80% and 75% of total RNA reads from the two leaf libraries and two root libraries were mapped to soybean genome, respectively (Table 1). Here, unique small RNAs were defined as small RNA species with unique sequence. For unique small RNAs, more than 80% of reads in HPL and LPL libraries, and more than 55% of reads in HPR and LPR libraries could be mapped to the genome, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics of four small RNA libraries from soybean

| |

Library namea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf+Pi (HPL) | Leaf-Pi (LPL) | Root+Pi (HPR) | Root-Pi (LPR) | |

| Total reads |

22925183 |

26658394 |

21456069 |

28635677 |

| High quality reads |

22643245(100%) |

26377550(100%) |

20957370(100%) |

27944092(100%) |

| Reads smaller than 18nt |

126772(0.56%) |

68893(0.26%) |

347577(1.66%) |

800247(2.86%) |

| Clean reads |

22483373(99.29%) |

26268210(99.59%) |

20564547(98.13%) |

27083979(96.92%) |

| Total small RNA reads mapping to genomeb |

18248364/22483373 (81.16%) |

22176679/26268210 (84.42%) |

20591098/27083979 (76.03%) |

15573680/20564547 (75.73%) |

| Unique small RNA reads mapping to genomeb | 2396442/2901995 (82.58%) | 3301579/3951946 (83.54%) | 2360847/4071174 (57.99%) | 2583592/4641188 (55.67%) |

aFour small RNA libraries were constructed. Total RNA were extracted from soybean leaves and roots grown in +Pi or -Pi nutrient solutions.

Accordingly the small RNA libraries were named leaf+Pi (HPL), leaf-Pi (LPL), root+Pi (HPR), and root-Pi (LPR).

bTotal small RNA reads and unique small RNA reads were mapped to the Glycine max genome v1.0 sequences available in Phytozome ( http://www.phytozome.org).

Additional file 2 summarized the origin profiles of total small RNAs. Fifteen and 14 percent of clean small RNA reads were mapped to known miRNA genes in HPR and LPR, respectively, but over 48% of small RNA reads from HPL and LPL libraries were mapped to miRNA genes. Additional file 3 demonstrated that the percentage of clean small RNAs with 20-24 nt was 85.16%, 89.90%, 52.22%, and 46.05% in HPL, LPL, HPR, and LPR, respectively, indicating good quality for the four small RNA libraries. In addition, more than 20% of the clean small RNA reads were assigned to unannotated regions of the Glycine max 1.0 genome, supporting the notion that most small RNAs originate from intergenic regions.

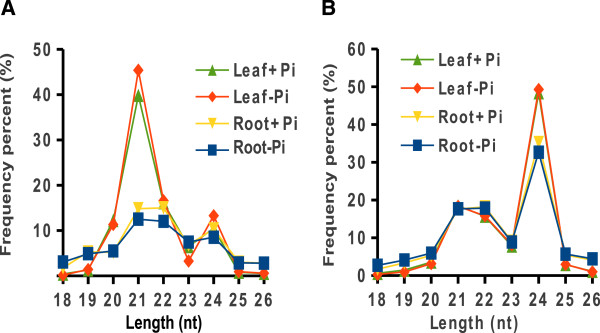

Small RNAs containing 21, 22, or 24 nucleotides had high abundance relative to those of other lengths in all four libraries, while those containing 20 nucleotides were high in leaves (Figure 1A; Additional file 3). The 39-45% abundance of 21 nt small RNAs in HPL and LPL library was dominant over 22 and 24-nt small RNAs (Figure 1A). When only unique reads were considered, 24-nt small RNAs were most abundant, with 21 nt and 22 nt small RNA following in all libraries (Figure 1B). Overall, these data are consistent with previous studies [10,20].

Figure 1.

Size distribution of small RNAs through Solexa sequencing. Small RNA size distribution from the libraries of leaves and roots grown under +Pi (HP) and -Pi (LP) conditions. The size distribution was plotted versus frequency (%) of small RNA read length relative to total small RNA reads (A) or unique small RNA reads (B).

The nucleotide preference of small RNAs

As described above (see Background), AGO proteins preferentially recruit miRNAs based upon the 5’ terminal nucleotide [5]. In the sequences obtained from soybean, the representation of the nucleotides in the 5’ position varied among miRNA lengths (Additional file 4).

Over 90% of the first nucleotide in 18 nt small RNAs in the two root libraries was C. The percentage of guanosine (G) in the first base of 19 nt small RNAs was the highest in the LPR library, whereas that of A was the highest in the HPR library. Interestingly, greater than 50% of U in the first position of 20 nt, 21 nt, and 22 nt-long small RNAs in all four libraries. Over 60% and 90% of 23 nt small RNAs were 5’-terminated with U in the two root libraries, but more than 90% of 23 nt small RNAs were tagged with G in the two leaf libraries. The percentage of A and U in the first position of 24 nt small RNAs were higher than that of the other nucleotides in leaf libraries, and the percentage of G in the first position of 24 nt small RNAs was higher than other nucleotides in the two root small RNA libraries. The 25 nt small RNAs with 5’ U were dominant in HPL, LPL, and HPR libraries (Additional file 4). These results indicate that P availability generally played little roles in the first base bias of small RNAs in soybean.

Identification of conserved and new miRNAs

After excluding the small RNA reads which can be mapped to protein-coding and structural RNA-coding regions, candidate miRNAs were predicted based on published methods [23]. To determine bona fide miRNAs, several strict criteria to scrutinize mature miRNAs were implemented, including: (1) the abundance of putative miRNAs was at least 100 transcripts per million (TPM) in any one of the four libraries; (2) the reads for 5p and 3p strand could be detected and the ratio of 5p/3p or 3p/5p was higher than 0.9; (3) the length of small RNAs was 20 to 24 nt; (4) the minimum folding free energy of the precursor of miRNA was lower than -37 KJ/mol. (5) the minimal free energy index (MFEIs) was higher than 0.85; (6) RNAfold predicted a hairpin secondary structure for pre-miRNA; (7) features of real pre-miRNA, as tested in the online service, plantMIRNAPred [24], verified the candidate as pre-miRNA. Subsequently, candidate mature miRNAs were Blast searched against the soybean miRNAs deposited in miRBase 18.0 ( http://www.mirbase.org) and new conserved, less-conserved (fabaceae-specific) and soybean novel microRNAs (soybean-specific) were determined.

As shown in Table 2, seventeen soybean miRNA families have been found in other plant families, and six have only been noted in fabaceae. Mature miRNAs ranged from 20 to 23 nt, and 11 out of 23 miRNA families were 21 nt-long. Most of the first nucleotide in all soybean miRNAs were U. More C was present in the 19th nucleotide than any other nucleotide (Table 2). This was consistent with earlier studies on soybean and cotton [18]. At the time of conducting this research, more than 240 soybean miRNAs, representing 65 families were curated in miRBase. A total of 126 soybean miRNAs in the current work were identified, 34 of which were annotated in miRBase 18.0. Eighty-nine of the 126 miRNAs, grouped into 21 families were conserved (Table 3), and 25 were less conserved miRNAs that were only be found in legumes, namely legume-specific (Table 4). The remaining 12 were soybean-specific (novel) miRNAs (Table 5).

Table 2.

Conserved and less-conserved miRNAs families detected in four small RNA libraries from soybean

| Family | Size (nt) | Site (5’ to 3’) | Homology in plant species | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

1st |

19th |

A.thaliana |

O.sativa |

Z.mays |

M.truncatula |

P.trichocarpa |

|

Conserveda |

||||||||

| MIR156 |

20-21, 23 |

U (82%) |

A (59%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR159 |

21 |

U (100%) |

C (100%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR160 |

21 |

G (100%) |

A (100%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR162_1 |

21 |

U (100%) |

C (100%) |

+ |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

| MIR164 |

21 |

U (100%) |

G (100%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR166 |

20-22 |

U (80%) |

C (50%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR167_1 |

21-22 |

U (100%) |

C (100%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR168 |

20-21 |

C (67%) |

A (67%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR169_2 |

21 |

A (67%) |

C (100%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR172 |

21 |

U/A/G (33%) |

C (67%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR390 |

21 |

A (100%) |

G (75%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR396 |

21 |

G (60%) |

A (60%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR397 |

21 |

U (100%) |

A (100%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

| MIR399 |

21 |

U (100%) |

C (100%) |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

| MIR2118 |

22 |

U (100%) |

C (100%) |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR408 |

20-21 |

C (67%) |

A (50%) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MIR482 |

21-22 |

U (56%) |

A (33%) |

− |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

|

Less-conservedb |

||||||||

| MIR1507 |

22 |

U (100%) |

C (100%) |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

− |

| MIR1508 |

21-22 |

U/C (50%) |

U/G (50%) |

− |

− |

− |

− |

− |

| MIR1509 |

21-22 |

U (100%) |

G (100%) |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

− |

| MIR1510 |

21-22 |

A (75%) |

U (50%) |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

− |

| MIR2109 |

21 |

U (100%) |

U (100%) |

− |

− |

− |

− |

− |

| MIR3522 | 22 | U (100%) | U (100%) | − | − | − | − | − |

The miRNAs in four soybean small RNA libraries were classified into conserved and less-conserved miRNAs based on the data in miRBase ( http://www.mirbase.org).

aFor conserved miRNAs, the counterpart of which can be found in other reference plants apart from legume.

bFor less-conserved miRNAs, the homology of which can only be found in legume.

+indicates the existence of miRNA in species, and - shows no homology in plant species.

A, adenosine; C, cytosine; G, guanosine; nt, nucleotide; U, uridine.

A.thaliana, Arabidopsis thaliana; O.sativa, Oryza sativa; Z.mays, Zea mays; M.truncatula, Medicao truncatula; P.P.trichocarpa, Poplus trichocarpa.

Table 3.

Conserved soybean miRNAs in four small RNA libraries

|

miRNA |

Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

Size (nt) |

Ch |

Start:end (+/-) |

Arm |

TPM in HPL |

TPM in LPL |

TPM in HPR |

TPM in LPR |

Registered in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRBase or not | ||||||||||

| miR156d |

TTGACAGAAGATAGAGAGCAC |

21 |

8 |

3891352:3891504:+ |

5 |

34857 |

30879 |

18368 |

15715 |

Yes |

| miR156h |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCAC |

20 |

4 |

4990842:4990964: − |

5 |

66744 |

55303 |

22303 |

26339 |

Yes |

| miR156o |

TTGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCAC |

21 |

17 |

37759430:37759553:+ |

5 |

1749 |

1579 |

1271 |

998 |

Yes |

| miR156p |

ACAGAAGATAGAGAGCACAG |

20 |

7 |

9347129:9347272:+ |

5 |

46 |

47 |

94 |

131 |

No |

| miR156q |

TGACAGAAGATAGAGAGCAC |

20 |

19 |

8895390:8895494:+ |

5 |

483 |

526 |

403 |

452 |

No |

| miR156r |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACT |

21 |

13 |

20521462:20521566:+ |

5 |

75 |

57 |

159 |

206 |

No |

| miR156s |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACT |

21 |

17 |

4291649:4291772: − |

5 |

75 |

57 |

159 |

206 |

No |

| miR156t |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACA |

21 |

2 |

41864154:41864278:+ |

5 |

173 |

156 |

99 |

108 |

No |

| miR156u |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACA |

21 |

4 |

4257047:4257175:+ |

5 |

173 |

156 |

99 |

108 |

No |

| miR156v |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACA |

21 |

6 |

4013560:4013688:+ |

5 |

173 |

156 |

99 |

108 |

No |

| miR156w |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACA |

21 |

14 |

9431588:9431718:+ |

5 |

173 |

156 |

99 |

108 |

No |

| miR156x |

TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACA |

21 |

17 |

38431855:38431985: − |

5 |

173 |

156 |

99 |

108 |

No |

| miR156y |

CTGACAGAAGATAGAGAGCAC |

21 |

18 |

61442592:61442691: − |

5 |

28 |

27 |

196 |

106 |

No |

| miR156z |

GCTCACTACTCTTTCTGTCGGTT |

23 |

19 |

40699080:40699213: − |

3 |

503 |

491 |

12 |

17 |

No |

| miR156_c1 |

TTGACAGAAGAAAGGGAGCAC |

21 |

1 |

55282671:55282770:+ |

5 |

291 |

274 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR156_c2 |

TTGACAGAAGAAAGGGAGCAC |

21 |

11 |

453213:453312: − |

5 |

291 |

274 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR156_c3 |

TTGACAGAAGAGAGAGAGCAC |

21 |

2 |

50779230:50779334: − |

5 |

182 |

139 |

45 |

32 |

No |

| miR159e-3p |

TTTGGATTGAAGGGAGCTCTA |

21 |

7 |

9524916:9525128: − |

5 |

191 |

250 |

293 |

109 |

Yes |

| miR160f |

GCGTATGAGGAGCCAAGCATA |

21 |

10 |

43851636:43851757: − |

3 |

56 |

46 |

117 |

128 |

No |

| miR160g |

GCGTATGAGGAGCCAAGCATA |

21 |

20 |

40554887:40554987:+ |

3 |

56 |

46 |

117 |

128 |

No |

| miR162c |

TCGATAAACCTCTGCATCCAG |

21 |

17 |

10181487:10181612:+ |

3 |

97 |

111 |

59 |

54 |

Yes |

| miR164e |

TGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGTGCA |

21 |

2 |

1511590:1511686:+ |

5 |

1621 |

2713 |

969 |

1532 |

No |

| miR164f |

TGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGTGCA |

21 |

3 |

45537767:45537877:+ |

5 |

1621 |

2713 |

969 |

1532 |

No |

| miR164g |

TGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGTGCA |

21 |

3 |

46896220:46896314:+ |

5 |

1621 |

2713 |

969 |

1532 |

No |

| miR164h |

TGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGTGCA |

21 |

19 |

48157202:48157297:+ |

5 |

1621 |

2713 |

969 |

1532 |

No |

| miR164i |

TGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGTGCA |

21 |

20 |

45788090:45788206: − |

5 |

1621 |

2713 |

969 |

1532 |

No |

| miR166a-5p |

GGAATGTTGTCTGGCTCGAGG |

21 |

16 |

1912569:1912713: − |

5 |

171 |

362 |

89 |

110 |

Yes |

| miR166g |

TCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCCC |

21 |

10 |

2905308:2905432: − |

3 |

16705 |

19874 |

20693 |

18766 |

Yes |

| miR166h-3p |

TCTCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCC |

21 |

8 |

14990535:14990743:+ |

3 |

520 |

620 |

5834 |

5908 |

Yes |

| miR166j-3p |

TCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCCG |

21 |

15 |

3688752:3688943: − |

3 |

964 |

1127 |

3563 |

3670 |

Yes |

| miR166k |

TCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCCT |

21 |

6 |

10985730:10985884:+ |

3 |

1128 |

1461 |

2223 |

2182 |

No |

| miR166l |

TCTCGGACCAGGCTTCATTC |

20 |

16 |

3661371:3661614:+ |

3 |

48 |

32 |

649 |

549 |

No |

| miR166m |

TCTCGGACCAGGCTTCATTC |

20 |

19 |

36649690:36649989: − |

3 |

48 |

32 |

649 |

549 |

No |

| miR166n |

TTTCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCC |

21 |

3 |

39519830:39519954: − |

3 |

72 |

68 |

148 |

113 |

No |

| miR166o |

TCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCC |

20 |

6 |

12992803:12992972: − |

3 |

75 |

53 |

118 |

103 |

No |

| miR166p |

TCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCC |

20 |

7 |

10198823:10198944:+ |

3 |

75 |

53 |

118 |

103 |

No |

| miR166q |

TCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCC |

20 |

9 |

37125221:37125362: − |

3 |

75 |

53 |

118 |

103 |

No |

| miR166r |

GGAATGTCGTCTGGTTCGAGA |

21 |

2 |

14340754:14340878:+ |

5 |

120 |

116 |

12 |

15 |

No |

| miR166s |

TTCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCCC |

22 |

5 |

37747448:37747571: − |

3 |

163 |

192 |

106 |

100 |

No |

| miR166t |

TTCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCCC |

22 |

8 |

282637:282760: − |

3 |

163 |

192 |

106 |

100 |

No |

| miR166u |

GGAATGTTGTCTGGCTCGAGG |

21 |

6 |

12992922:12993135: − |

5 |

177 |

370 |

92 |

114 |

No |

| miR167e |

TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCTT |

21 |

20 |

37901894:37902003:+ |

5 |

1866 |

1676 |

2108 |

1984 |

Yes |

| miR167g |

TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCTGA |

22 |

10 |

39044864:39044969:+ |

5 |

160 |

139 |

12 |

11 |

Yes |

| miR167j |

TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCTG |

21 |

20 |

44765083:44765188:+ |

5 |

5198 |

6009 |

381 |

405 |

Yes |

| miR167k |

TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCTA |

21 |

3 |

39319064:39319173:+ |

5 |

236 |

255 |

166 |

61 |

No |

| miR167l |

TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCTTA |

22 |

10 |

46574251:46574360: − |

5 |

1210 |

1096 |

951 |

839 |

No |

| miR168 |

TCGCTTGGTGCAGGTCGGGAA |

21 |

9 |

41353223:41353352: − |

5 |

10469 |

8526 |

7573 |

7864 |

Yes |

| miR168c |

CCCGCCTTGCATCAACTGAAT |

21 |

1 |

48070300:48070429: − |

3 |

195 |

223 |

277 |

327 |

No |

| miR168d |

CCCGCCTTGCATCAACTGAAT |

21 |

9 |

41353223:41353352: − |

3 |

195 |

223 |

277 |

327 |

No |

| miR169c |

AAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCGA |

21 |

9 |

5295079:5295216:+ |

5 |

29 |

12 |

119 |

95 |

Yes |

| miR169f |

CAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCGG |

21 |

10 |

40332781:40332933: − |

5 |

103 |

99 |

29 |

32 |

Yes |

| miR169o |

CAGCCAAGGGTGATTTGCCGG |

21 |

15 |

14150055:14150198:+ |

5 |

72 |

144 |

301 |

326 |

No |

| miR169p |

AAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCGG |

21 |

9 |

5299595:5299718:+ |

5 |

21 |

14 |

118 |

92 |

No |

| miR169q |

AAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCGA |

21 |

15 |

14202454:14202568:+ |

5 |

0.01 |

12 |

125 |

102 |

No |

| miR169r |

AAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCGG |

21 |

17 |

4864165:4864284: − |

5 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

122 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR172b-3p |

AGAATCTTGATGATGCTGCAT |

21 |

13 |

40401672:40401822: − |

3 |

3576 |

4906 |

584 |

689 |

Yes |

| miR172h-5p |

GCAGCAGCATCAAGATTCACA |

21 |

10 |

43474719:43474839:+ |

5 |

103 |

97 |

9 |

11 |

Yes |

| miR172k |

TGAATCTTGATGATGCTGCAT |

21 |

12 |

33560621:33560754:+ |

3 |

89 |

133 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR390b |

AAGCTCAGGAGGGATAGCACC |

21 |

2 |

44954748:44954865:+ |

5 |

32 |

28 |

175 |

199 |

Yes |

| miR390d |

AAGCTCAGGAGGGATAGCGCC |

21 |

11 |

30272752:30272868:+ |

5 |

515 |

328 |

230 |

268 |

No |

| miR390e |

AAGCTCAGGAGGGATAGCGCC |

21 |

18 |

53278026:53278171:+ |

5 |

515 |

328 |

230 |

268 |

No |

| miR390f |

AAGCTCAGGAGGGATAGCGCC |

21 |

18 |

5047758:5047875: − |

5 |

515 |

328 |

230 |

268 |

No |

| miR396a-5p |

TTCCACAGCTTTCTTGAACTG |

21 |

13 |

26338131:26338273: − |

5 |

75 |

110 |

323 |

299 |

Yes |

| miR396b-3p |

GCTCAAGAAAGCTGTGGGAGA |

21 |

13 |

26329939:26330049:+ |

3 |

138 |

220 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

Yes |

| miR396c |

TTCCACAGCTTTCTTGAACTT |

21 |

13 |

43804787:43804882:+ |

5 |

141 |

191 |

93 |

101 |

Yes |

| miR396j |

GTTCAATAAAGCTGTGGGAAG |

21 |

13 |

26338141:26338266: − |

5 |

0.01 |

130 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR396k |

GCTCAAGAAAGCTGTGGGAGA |

21 |

13 |

26329931:26330059:+ |

3 |

91 |

172 |

8 |

21 |

No |

| miR397a |

TCATTGAGTGCAGCGTTGATG |

21 |

8 |

4639045:4639154: − |

5 |

161 |

253 |

0.01 |

17 |

Yes |

| miR399a |

TGCCAAAGGAGATTTGCCCAG |

21 |

5 |

34958613:34958732: − |

3 |

21 |

712 |

8 |

280 |

No |

| miR399b |

TGCCAAAGGAGATTTGCCCAG |

21 |

5 |

34967642:34967778: − |

3 |

21 |

712 |

8 |

280 |

No |

| miR399c |

TGCCAAAGGAGATTTGCCCAG |

21 |

8 |

9118500:9118624: − |

3 |

21 |

712 |

8 |

280 |

No |

| miR399d |

TGCCAAAGGAGATTTGCCCAG |

21 |

8 |

9126508:9126640: − |

3 |

21 |

712 |

8 |

280 |

No |

| miR399e |

TGCCAAAGAAGATTTGCCCAG |

21 |

5 |

34963165:34963300: − |

3 |

0.01 |

394 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR2118a |

TTGCCGATTCCACCCATTCCTA |

22 |

20 |

35349746:35349875:+ |

3 |

2084 |

3812 |

2429 |

2557 |

Yes |

| miR2118b |

TTGCCGATTCCACCCATTCCTA |

22 |

10 |

48574023:48574132: − |

3 |

2084 |

3812 |

2429 |

2557 |

Yes |

| miR408b −5p |

CTGGGAACAGGCAGGGCACG |

20 |

3 |

44626682:44626839: − |

5 |

228 |

362 |

13 |

12 |

Yes |

| miR408c |

ATGCACTGCCTCTTCCCTGGC |

21 |

10 |

36556991:36557143: − |

3 |

516 |

1215 |

70 |

84 |

Yes |

| miR408d |

CTGGGAACAGGCAGGGCACGA |

21 |

3 |

44626682:44626839: − |

5 |

409 |

588 |

81 |

78 |

No |

| miR408e |

CAGGGGAACAGGCAGAGCATG |

21 |

2 |

837410:837560:+ |

5 |

380 |

295 |

12 |

14 |

No |

| miR408f |

CAGGGGAACAGGCAGAGCATG |

21 |

10 |

36556991:36557143: − |

5 |

380 |

295 |

12 |

14 |

No |

| miR408g |

GCTGGGAACAGGCAGGGCACG |

21 |

3 |

44626682:44626839: − |

5 |

100 |

167 |

21 |

22 |

No |

| miR482b-3p |

TCTTCCCTACACCTCCCATACC |

22 |

20 |

35360307:35360413:+ |

3 |

37 |

154 |

218 |

494 |

Yes |

| miR482e |

GGAATGGGCTGATTGGGAAGC |

21 |

2 |

7783811:7783923:+ |

5 |

560 |

711 |

651 |

562 |

No |

| miR482f |

TTCCCAATTCCGCCCATTCCTA |

22 |

2 |

7783811:7783923:+ |

3 |

182 |

696 |

91 |

163 |

No |

| miR482g |

TTCCCAATTCCGCCCATTCCTA |

22 |

18 |

61452897:61453007: − |

3 |

182 |

696 |

91 |

163 |

No |

| miR482h |

TATGGGGGGATTGGGAAGGAA |

21 |

10 |

48569622:48569728: − |

5 |

147 |

110 |

133 |

114 |

No |

| miR482i |

TATGGGGGGATTGGGAAGGAA |

21 |

20 |

35360307:35360413:+ |

5 |

147 |

110 |

133 |

114 |

No |

| miR482j |

TTCCCAATTCCGCCCATTCCTA |

22 |

2 |

7783818:7783913:+ |

5 |

195 |

736 |

0.01 |

186 |

No |

| miR482k | TTCCCAATTCCGCCCATTCCTA | 22 | 18 | 61452907:61453000: − | 5 | 195 | 736 | 0.01 | 186 | No |

Soybean conserved miRNAs were grouped into different miRNA families based on Blast analysis of mature miRNA sequences in miRBase ( http://www.mirbase.org). For conserved miRNAs, homology of which can be found in other plant species apart from legume.

Ch, chromosome; HPL, leaf+Pi; HPR, root+Pi; LPL, leaf-Pi; LPR, root-Pi; nt, nucleotide; TPM, transcript per million reads; +, sense strand; −, antisense strand.

miR156_c1 means new soybean miR156 candidate 1, and so on in other miRNA families.

Table 4.

Less-conserved soybean miRNAs in four small RNA libraries

|

miRNA |

Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

Size (nt) |

Ch |

Start:End (+/-) |

Arm |

TPM in HPL |

TPM in LPL |

TPM in HPR |

TPM in LPR |

Registered in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRBase or not | ||||||||||

|

MIR1507 |

||||||||||

| miR1507a |

TCTCATTCCATACATCGTCTGA |

22 |

13 |

25849776:25849883:+ |

3 |

93418 |

6787 |

2 73567 |

59118 |

Yes |

|

MIR1508 |

||||||||||

| miR1508d |

TAGAAAGGGAAATAGCAGTTG |

21 |

9 |

28530172:28530267:+ |

3 |

6600 |

7129 |

1596 |

1456 |

No |

| miR1508e |

CTAGAAAGGGAAATAGCAGTTG |

22 |

16 |

32903737:32903831:+ |

3 |

1347 |

1516 |

374 |

317 |

No |

|

MIR1509 |

||||||||||

| miR1509a |

TTAATCAAGGAAATCACGGTCG |

22 |

17 |

10099759:10099871:+ |

5 |

7221 |

8003 |

21070 |

17929 |

Yes |

| miR1509c |

TTAATCAAGGAAATCACGGTTG |

22 |

5 |

7774098:7774206: − |

5 |

316 |

531 |

2125 |

2125 |

No |

| miR1509d |

TTAATCAAGGAAATCACGGTC |

21 |

17 |

10099759:10099871:+ |

5 |

45 |

50 |

130 |

117 |

No |

|

MIR1510 |

||||||||||

| miR1510b-3p |

TGTTGTTTTACCTATTCCACC |

21 |

2 |

6599300:6599391:+ |

3 |

75 |

125 |

139 |

162 |

Yes |

| miR1510b-5p |

AGGGATAGGTAAAACAACTACT |

22 |

2 |

6599292:6599401:+ |

5 |

1462 |

3478 |

968 |

1980 |

Yes |

| miR1510c |

AGGGATAGGTAAAACAACTAC |

21 |

2 |

6599292:6599401:+ |

5 |

750 |

851 |

697 |

1377 |

No |

| miR1510d |

AGGGATAGGTAAAACAATGAC |

21 |

16 |

31518900:31519009:+ |

5 |

136 |

266 |

245 |

822 |

No |

|

MIR2109 |

||||||||||

| miR2109a |

TGCGAGTGTCTTCGCCTCTGA |

21 |

4 |

28532444:28532532: − |

5 |

50 |

6 |

181 |

220 |

No |

|

MIR3522 |

||||||||||

| miR3522a |

TGAGACCAAATGAGCAGCTGAC |

22 |

15 |

4318787:4318887:+ |

5 |

139 |

115 |

7 |

0.01 |

No |

|

Family undefined | ||||||||||

| miR1511 |

AACCAGGCTCTGATACCATGG |

21 |

18 |

21161229:21161335:+ |

3 |

1099 |

1034 |

5415 |

8419 |

Yes |

| miR1511a |

AACCAGGCTCTGATACCATGGT |

22 |

18 |

21161229:21161335:+ |

3 |

31 |

28 |

77 |

113 |

No |

| miR1512b |

TAACTGGAAATTCTTAAAGCAT |

22 |

2 |

8618690:8618783: − |

5 |

0.01 |

8 |

72 |

102 |

No |

| miR3508 |

TAGAAGCTCCCCATGTTCTCA |

21 |

15 |

5418778:5418967:+ |

3 |

75 |

355 |

120 |

104 |

No |

| miR4345 |

TAAGACGGAACTTACAAAGATT |

22 |

14 |

49067429:49067781:+ |

5 |

77 |

92 |

151 |

139 |

Yes |

| miR4345a |

TTAAGACGGAACTTACAAAGATT |

23 |

14 |

49067429:49067781:+ |

5 |

131 |

158 |

314 |

260 |

No |

| miR4345b |

CTAAGACGGAACTTACAAAGAT |

22 |

14 |

49069094:49069198:+ |

5 |

127 |

141 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR4376-5p |

TACGCAGGAGAGATGACGCTGT |

22 |

13 |

40845924:40846035:+ |

5 |

250 |

154 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

Yes |

| miR4376a |

ACGCAGGAGAGATGACGCTGT |

21 |

13 |

40845924:40846035:+ |

5 |

352 |

155 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR4376b |

TACGCAGGAGAGATGACGCTG |

21 |

13 |

40845924:40846035:+ |

5 |

358 |

216 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

No |

| miR4413c |

TAAGAGAATTGTAAGTCACTG |

21 |

19 |

1788521:1788616: − |

5 |

46 |

65 |

120 |

119 |

No |

| miR4416a |

ACGGGTCGCTCTCACCTGGAG |

21 |

2 |

30498955:30499126: − |

3 |

0.01 |

11 |

123 |

158 |

No |

| miR4416b | ATACGGGTCGCTCTCACCTAGG | 22 | 19 | 40699080:40699213: − | 3 | 8 | 16 | 95 | 139 | No |

Soybean less-conserved miRNAs were grouped into miRNA families based on Blast analysis of mature miRNA sequences in miRBase 18.0 ( http://www.mirbase.org). For less-conserved miRNAs, homology of which can only be found in legume (legume-specific).

Ch, chromosome; HPL, leaf+Pi; HPR, root+Pi; LPL, leaf-Pi; LPR, root-Pi; nt, nucleotide; TPM, transcript per million reads; +, sense strand; −, antisense strand.

Table 5.

Novel soybean miRNAs in four small RNA libraries

|

miRNA |

Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

Size (nt) |

Ch |

Start:End (+/ −) |

Arm |

TPM in HPL |

TPM in LPL |

TPM in HPR |

TPM in LPR |

Registered in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRBase or not | ||||||||||

| miRnov_1a |

AAAGCCATGACTTACACACGC |

21 |

17 |

1401437:1401518: − |

5 |

160 |

173 |

271 |

249 |

No |

| miRnov_1b |

AAAGCCATGACTTACACACGC |

21 |

20 |

223678:223767: − |

5 |

163 |

179 |

281 |

259 |

NO |

| miRnov_2 |

ATTGGGACAATACTTTAGATA |

21 |

18 |

52797184:52797492:+ |

3 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

153 |

NO |

| miRnov_3 |

GGAGATGGGAGGGTCGGTAAAG |

21 |

20 |

35349749:35349874:+ |

5 |

419 |

371 |

351 |

595 |

NO |

| miRnov_4 |

ATATGGACGAAGAGATAGGTAA |

21 |

20 |

40357028:40357130:+ |

5 |

115 |

120 |

249 |

187 |

NO |

| miRnov_5a |

CAGGGGAACAGGCAGAGCATG |

21 |

2 |

837420:837549:+ |

5 |

394 |

307 |

86 |

15 |

NO |

| miRnov_5b |

CAGGGGAACAGGCAGAGCATG |

21 |

10 |

36557001:36557133: − |

5 |

394 |

307 |

86 |

15 |

NO |

| miRnov_6 |

AGAGGTGTATGGAGTGAGAGA |

21 |

13 |

25849778:25849881:+ |

5 |

256 |

122 |

96 |

98 |

NO |

| miRnov_7 |

AGCTGCTCATCTGTTCTCAGG |

21 |

15 |

4318784:4318876:+ |

3 |

48 |

137 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

NO |

| miRnov_8 |

GCTCACTACTCTTTCTGTCGGTT |

21 |

17 |

37759439:37759543:+ |

3 |

609 |

615 |

18 |

24 |

NO |

| miRnov_9 |

TCAATCCTGGAAGAACCGGCG |

21 |

13 |

35514890:35515064:+ |

3 |

44 |

35 |

106 |

51 |

NO |

| miRnov_10 | AGGAAGCTAAGACGGAACTTA | 21 | 14 | 49069088:49069204:+ | 5 | 44 | 0.01 | 110 | 87 | NO |

Soybean novel miRNAs were identified based on Blast analysis of mature miRNA sequences. For novel miRNAs, which were not previously in miRBase and not assigned into any family were denoted by miRnov (soybean-specific).

Ch, chromosome; HPL, leaf+Pi; HPR, root+Pi; LPL, leaf-Pi; LPR, root-Pi; nt, nucleotide; TPM, transcript per million reads; +, sense strand; −, antisense strand.

Importantly, ninety-two soybean miRNAs have been identified in this study for the first time (Tables 3, 4 and 5). Sixty-two of these are conserved miRNAs and grouped into 14 families (Table 3). Eight are less-conserved and classified into 5 families (Table 4). Ten of the miRNAs identified in this study can be found in other plant species, but have not yet been classified into any miRNA families in miRBase. Finally, 12 miRNAs identified herein are as yet soybean-specific novel miRNAs (Table 5). More importantly, in regards to plant nutrition, miR399a, miR399b, miR399c, miR399d, and miR399e were detected in the present small libraries. Moreover miR399a, miR399b, and miR399e were localized to chromosome 5, while miR399c and miR399d were localized to chromosome 8 (Table 3).

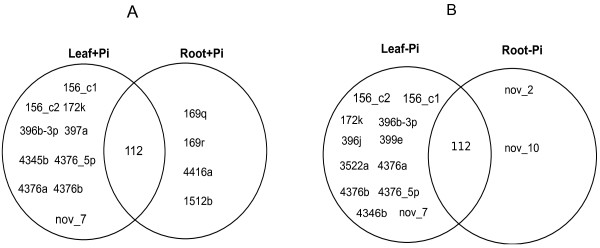

Soybean leaf- and root-specific miRNAs

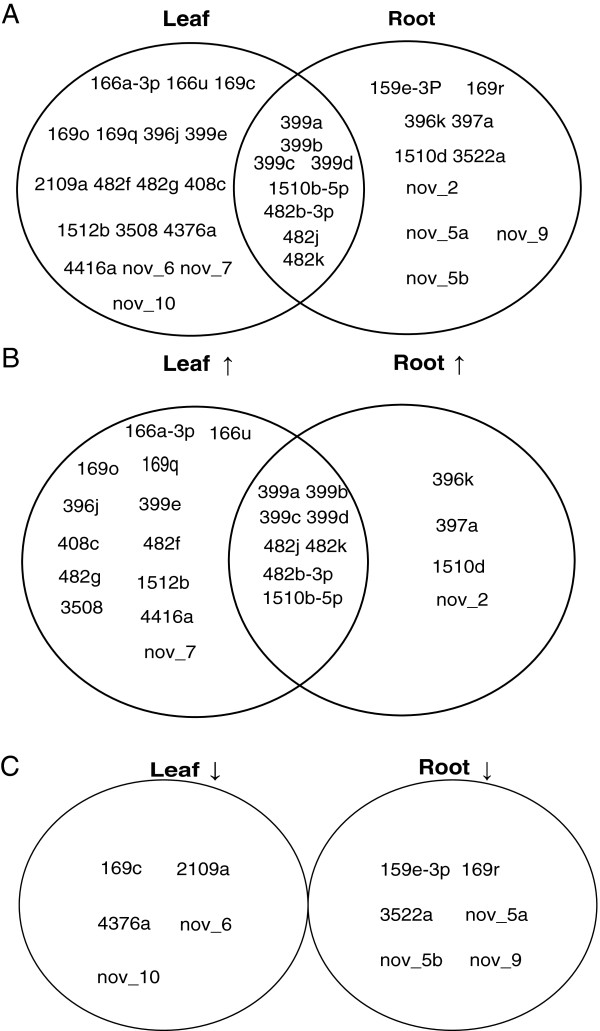

To determine leaf- and root-specific miRNAs, the abundance of each mature miRNA was compared between leaves and roots. If a miRNA was not detectable in leaves or roots, then it was considered as specific to the other tissue. Under control (+Pi) conditions, ten leaf-specific, and four root-specific miRNAs were found (Figure 2A). Under Pi-depleted conditions, there are twelve leaf-specific miRNAs, and two root-specific miRNAs (Figure 2B). The two root-specific miRNAs in Pi-depleted plants are novel to soybean (gma-nov_2 and gma-nov_10).

Figure 2.

Unique and overlapping soybean miRNAs in leaves and roots under +Pi and -Pi conditions.A: leaf-specific and root-specific miRNAs in +Pi conditions; B:leaf-specific and root-specific miRNAs under -Pi conditions.

A number of miRNAs are notable for their expression patterns. This included most members of miR156, 164 and 167 families, along with 12 individual miRNAs (miR168, miR172b-3p, miR2118a, miR2118b, miR408c, miR1507a, miR1508d, miR1508e, miR1509a, miR1510b-5p, miR1510c, and miR1511) that were found in high abundance (>1000 TPM) in one or both of the HPL or LPL treatments (Tables 3, 4 and 5). Others appeared to be constitutively expressed in leaves and roots, including, for example, members of the conserved miR160, miR164, and miR2118 families (Table 3). Within families, expression can vary significantly among family members. For example, expression levels of miR156 family members ranged from 46 to 66744 TPM in leaves, and from 0.01 (actually 0, only for normalization) to 22303 TPM in roots, and expression levels of miR166 family members ranged from from 48 to 16705 TPM in leaves, and from 12 to 20693 TPM in roots (Table 3). Overall, a diverse range of responses was observed among treatments, tissues and family members, but variation between leaves and roots appeared to be more prevalent in less-conserved than in conserved miRNAs (Tables 3, 4 and 5).

Identification of P-responsive miRNAs

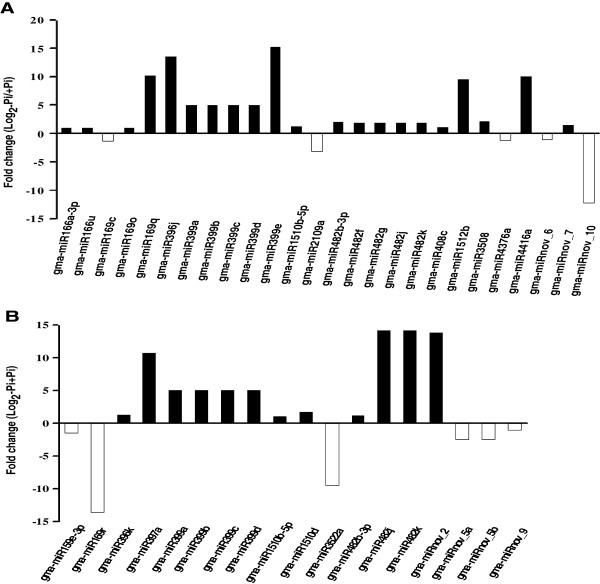

Soybean P-responsive miRNAs were identified by calculating the log fold change in read counts, log 2(-Pi/+Pi). If this value was greater than 1, the miRNAs were considered to be induced by P deficiency. Figure 3A shows that the expression of 21 out of 126 (16.7%) mature miRNAs was stimulated in leaves by Pi starvation with fold changes ranging from 1 to 15.27. Moreover, in contrast to other -Pi-induced miRNAs, miR169q, miR396j, miR399e, and miR4416a were sharply induced in leaves by Pi limitation, with no expression detected in +Pi and expression over 10 in -Pi (Figure 3A; Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Fold change (log2(-Pi/+Pi)) of miRNA expression analysis using transcript per million (TPM) transformed data from P treatment libraries.A: miRNAs from leaves; B: miRNAs from roots. Black and white bar indicates -Pi-induced and -Pi-repressed miRNAs, respectively.

In roots, twelve out of 126 (9.5%) miRNAs were stimulated by Pi starvation with log fold changes ranging from 1.03 to 14.18 (Figure 3B). The levels of miR397a, miR482j, miR482k, and miRnov_2 in roots were induced from no detected expression to considerable expression in +Pi and -Pi (Figure 3B; Tables 3 and 5). On the other hand, miR169r and miR3522a were significantly down-regulated by Pi depletion (Figure 3B; Tables 3 and 4). Figure 4A shows that thirty-six miRNAs were Pi-responsive in soybean genome-wide, with 26 and 18 being responsive in leaves and roots, respectively. Eight miRNAs were induced under -Pi conditions both in leaves and roots and none were repressed (Figure 4B, C; Tables 3, 4 and 5;). Perhaps more intriguingly, 5 miRNAs were tissue specific and had expression altered by P treatment. Those that were induced in -Pi relative to +Pi are the leaf specific miR396j and miRnov_7, and the root-specific miRnov_2 (Figure 4B; Tables 3 and 5). Those that were repressed are the leaf-specific miR4376a and the root-specific miR169r (Figure 4C; Tables 3 and 4). This tissue specificity and P responsiveness implies the tissue-specific roles of miRNAs in P signaling.

Figure 4.

Unique and overlapping soybean P-responsive miRNAs in leaves and roots induced or repressed by -Pi treatment.A: Unique and overlapping soybean P-responsive miRNAs in leaves and roots; B: Unique and overlapping soybean miRNAs in leaves and roots up-regulated by -Pi treatment; C: Unique and overlapping soybean miRNAs in leaves and roots down-regulated by -Pi treatment.

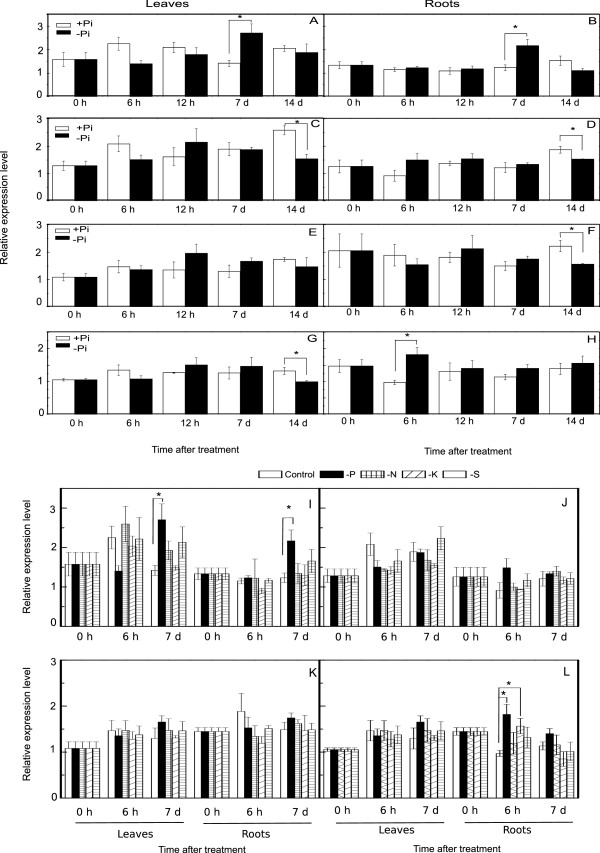

The expression levels of mature miR399, miRnov_6, miRnov_9, and miRnov_10 were determined through stem-loop real-time PCR [25]. Because mature sequences of miR399a, 399b, 399c, and miR399d are 100% identical (Table 3), it is impossible to distinguish the levels of the four mature miR399s with stem-loop PCR. The total abundance of miR399a/b/c/d was significantly induced by Pi starvation in both leaves (Figure 5A) and roots (Figure 5B) after 7 d of Pi starvation, but not at any other tested time point. The expression level of miRnov_6 in leaves (Figure 5C) and roots (Figure 5D) was decreased on day 14 of Pi starvation (P <0.05). The expression of miRnov_9 was repressed by P deficiency on day 14 in roots, but not in leaves (Figure 5E and F). Interestingly, the level of miRnov_10 was repressed in leaves on day 14 (Figure 5G) and induced in roots at 6 h (Figure 5H), which might indicate that miRnov_10 plays an important role in local and systematic P signaling pathways.

Figure 5.

Expression analysis of miRNA399a/b/c/d, miRnov_6, miRnov_9, miRnov_10 under Pi-starvation and others different nutrient deficiency. A-H: expression patterns of miRNA399a/b/c/d/ (A and B), miRnov_6 (C and D), miRnov_9 (E and F), and miRnov_10 (G and H) in leaves and roots in +Pi and -Pi; I-L: expression patterns of miRNA399a/b/c/d (I), miRnov_6 (J), miRnov_9 (K), and miRnov_10 (L) in leaves and roots under different nutrient deficiency conditions. Stars above bar indicate the significant difference.

To determine whether the responses of the above-mentioned miRNAs are specific to Pi stress, the responses to N, potassium (K), and S starvation were explored. Expression alterations of marker genes GmNRT2(Glyma13g39850), GmHAK1(Glyma19g45260), GmSult1 (Glyma06g111500) indicated that the tested soybean seedlings were really subjected to N, K, and S starvation, respectively (data not shown). The miRNA miR399a/b/c/d responded to Pi starvation in leaves and roots, but not to other nutrient deficiencies (Figure 5I). Neither miRnov_6 nor miRnov_9 responded to any nutrient deficiencies at 6 h and 7 day either in leaves or roots (Figure 5J, K), which is consistent with the requirement of 14-day Pi starvation for a response (Figure 5C, D, E, F). Therefore, we could not determine whether miRnov_6 or miRnov_9 was specifically responsive to Pi. The expression of miRnov_10 in roots was induced by Pi starvation and K deficiency at 6 h (Figure 5L), which was consistent with the previous test and indicative of a nonspecific response.

AtIPS1 attenuates miR399s activity via the formation of the three-nucleotide bulge in the highly complementary region where cleavage occurs [26]. Upon searching in soybean transcriptome ( http://www.tigr.org), four GmIPS (GmIPS1-4) members were found. Among them, GmIPS1 nearly perfectly matched miR399a, b, c, d, and e over the center region, thus forming a three-nucleotide bulge (Additional file 5), and thereby implying that soybean miR399 activity might be negatively modulated by GmIPS1 as in Arabidopsis.

Soybean root RNA degradome library sequencing

To determine the targets of soybean miRNAs, an LPR small RNA degradome library was constructed based on described methods [20]. A total of 28, 557,354 high quality reads containing more than 25 million clean reads were obtained from the root degradome library (Additional file 6). In addition, slightly more 21- than 20-nt sequences were obtained (data not shown). After excluding reads smaller than 18 nt and adaptors, approximately 88% of clean reads were analyzed (Additional file 6). Furthermore 83.93% of clean reads (21,185,857 out of 25,241,382) and 67.72% of unique reads (2,406,610 out of 3,553,894) were mapped to the soybean genome (Additional file 6).

Target prediction of Glycinemax conserved, less-conserved, and novel miRNAs

Pairfinder was employed to analyze the dedradome sequencing data as described in Methods. Degradome data showed that 51 genes were the targets of 19 conserved miRNAs (Additional file 7), 10 genes were the targets of 4 less-conserved miRNAs (Additional file 8), and 11 genes were the targets of 8 novel miRNAs (Additional file 9). One gene, Glyma08g21620 was detected to be the target of both miR166g and miRnov_2. Hence, a total of 71 genes were determined to be the targets of 126 miRNAs by degradome sequencing.

Since some miRNA targets were not detected in degradome sequencing, psRNAtarget ( http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) was employed as a complementary approach to predict miRNA target genes. In combination with degradome sequencing, a total of 154 genes were predicted or detected to be the target of 126 miRNAs. Putatively, 98 genes were attacked by 89 conserved miRNAs, 37 genes were the targets of 25 less-conserved miRNAs, and 20 genes were targeted by 12 novel miRNAs. Previous studies indicated that conserved miRNAs attach to targets in the CDS. Consistent with this, for the conserved and less-conserved miRNAs, 94.8% (182 out of 192) and 85.2% (40 out of 47) of cleavage sites were in CDS regions, respectively. For novel miRNAs, the percentage was 100%. Interestingly, the 28 transcripts targeted by the 12 novel soybean miRNAs included 19 transcripts for 7 miRNAs (miRnov_1a, miRnov_1b, miRnov_2, miRnov_3, miRnov_5a, miRnov_5b, miRnov_6, miRnov_7) in the root degradome library, and 9 transcript targets for four miRNAs (miRnov_4, miRnov_8, miRnov_9, miRnov_10) predicted through computational analysis (Additional file 9).

As for the conserved miRNAs, the number of targets for conserved miRNA (2.31 targets per miRNA) was higher than that of less-conserved miRNA (1.53 targets per miRNA) (Additional files 7 and 8). Among the conserved miRNAs, five (miR162c, miR166h-3p, miR166j-3p, miR390b,and miR408b-5p) were identified to have only one target, while the rest have two or more targets, most notably miR156d, miR167e, miR167g, miR167j, miR167k, miR172b-3p, and miR172h-5p (Additional file 7). In contrast, 15 out of 25 less-conserved miRNAs had only one target. However, the previously unreported less-conserved miR1508e and miR3508 each have seven targets (Additional file 8). Glyma08g21610 and Glyma16g34300, which encode a AGO proteinendoing and a HD-ZIP protein respectively, were predicted target of miR166g and miR168 (Additional file 7). A NF-YA gene Glyma10g10240 was the putative target of miR169c (Additional file 7). Importantly, these predicted cleavage sites for the three targets are consistent with previous RLM-5’ RACE results [20,27,28], supporting the reliability of our computational analysis.

In general, miRNAs that are conserved across plants, such as miR156, miR164, miR167 and miR169, target transcription factors (TFs), whereas less-conserved miRNAs target fewer TFs (Additional file 8). Overall, 54% (53 out of 98) of conserved miRNA target genes were TFs (Additional file 7), while only 2.7% (1 out of 37) and 10.0% (2 out of 20) of less-conserved and novel miRNA target genes, respectively, were TFs (Additional files 8 and 9). This is in accordance with previous study [20].

In regards to nutrient stress, the targets of root P-responsive miRNAs and their cleavage sites are highlighted in Table 6. A PHO2, two Pi transporter transcripts (Glyma10g04230 and Glyma14g36650), and an AP2 protein gene (Glyma01g13410) were predicted to be targets of miR399a, b, c, d, and e (Table 6). In fact, miR2111 was detected in small RNA libraries in this study, but the level of it was too low to be filtered out based on the strict criteria. The target of miR2111 was predicted. As in Arabidopsis, a kelch repeat-containing F-box protein, Glyma16g01060, was the putative target of miR2111. The targets of the Pi starvation-induced miR169o, miR397a, miR408c, miR4416a, miRnov_2, and miRnov_7 were detected in the degradome library or computationally predicted, as were the targets of the P limitation-repressed miRNAs miR159e-3p, miR169r, miR2109, miR4376, miRnov_5a, miRnov_5b, and miRnov_6a (Table 6). It must be pointed out that most of the targets listed in Additional files 7, 8 and 9 need to be experimentally confirmed with RLM-5’ RACE or transit expression analysis.

Table 6.

Target genes of P-responsive miRNAs in soybean

|

miRNA |

Target gene |

Target description |

Cleavage site (nt) |

Abundance |

Target site location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (TP10M) | |||||

|

UP-regulated miRNAs by -Pi | |||||

| m |

Glyma20g37690.1 |

No annotationc |

2526 |

|

CDS |

| miR166u |

Glyma05g06070.1 |

Mybb |

1806 |

|

CDS |

| miR169o |

Glyma06g03940.1 |

Peptidase S24-likea |

584 |

38.429 |

CDS |

| miR169q |

Glyma18g07890.1 |

NF-YAb |

949 |

|

CDS |

| miR396j |

Glyma02g45340.1 |

LRR/NB-ARC domain/TIR domainb |

710 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma10g00320.1 |

Protease family S9Bb |

1252 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma12g28570.1 |

Core-2/I-Branching enzymeb |

753 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma16g00260.1 |

Core-2/I-Branching enzymeb |

711 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma17g35500.1 |

Syntaxin 6, N-terminalb |

988 |

|

CDS |

| miR396k |

Glyma12g01390.1 |

Cytokinin dehydrogenasec |

730 |

|

CDS |

| miR397a |

Glyma11g19150.1 |

Male sterility proteina |

1484 |

34.8634 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma12g09270.1 |

Male sterility proteina |

1475 |

34.8634 |

CDS |

| miR399a/b/c/d |

Glyma10g04230.1 |

Phosphate transporterb |

407 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma01g13410.1 |

AP2b |

27 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma14g36650.1 |

Phosphate transporterb |

240 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma13g31290.1 |

PHO2b |

1050 |

|

5’UTR |

| miR399e |

Glyma10g04230.1 |

Phosphate transporterc |

407 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma13g31290.1 |

PHO2c |

1050 |

|

5’UTR |

| miR408c |

Glyma06g12680.1 |

Plastocyanin-like domaina |

207 |

55.8606 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma08g13510.1 |

Plastocyanin-like domaina |

198 |

18.224 |

CDS |

| miR1510b-5p |

Glyma10g16090.1 |

PCI domain/eIF3 subunit 6 N terminal domainc |

1451 |

|

3’UTR |

| miR1510d |

Glyma11g04630.1 |

Domain of unknown function (DUF296)c |

1152 |

|

3’UTR |

| miR482f |

Glyma05g01650.1 |

PPRc |

521 |

|

CDS |

| miR482g |

Glyma05g01650.1 |

PPRc |

521 |

|

CDS |

| miR482j |

Glyma05g06070.1 |

Mybb |

282 |

|

CDS |

| miR482k |

Glyma05g06070.1 |

Mybb |

282 |

|

CDS |

| miR482b-3p |

Glyma09g39410.1 |

LRR/NB-ARC domain/leucine-rich repeat-containing proteinc |

513 |

|

CDS |

| miR1512b |

Glyma08g17790.1 |

D-mannose binding lectin/Domain of unknown function (DUF3403)b |

1209 |

|

CDS |

| miR3508 |

Glyma06g42170.1 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF_B2219)/Polyphenol oxidase middle domainb |

1048 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma07g31290.1 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF_B2220)/Polyphenol oxidase middle domainb |

2569 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma07g31310.1 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF_B2221)/Polyphenol oxidase middle domainb |

1117 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma13g25150.1 |

Polyphenol oxidase middle domain/Common central domain of tyrosinaseb |

1096 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma13g25180.1 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF_B2219)/Polyphenol oxidase middle domainb |

1025 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma13g25260.1 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF_B2220)/Polyphenol oxidase middle domainb |

1199 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma15g07710.1 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF_B2221)/Polyphenol oxidase middle domainb |

1077 |

|

CDS |

| miR4416a |

Glyma10g06650.1 |

Uncharacterized nodulin-like proteinb |

1544 |

|

CDS |

| miRnov_2 |

Glyma08g21620.1 |

START domaina |

2712 |

19.0164 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma08g21620.2 |

START domaina |

1892 |

13.8661 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma18g51750.1 |

LRR/NB-ARC domaina |

1840 |

46.3525 |

CDS |

| miRnov_7 |

Glyma19g37520.1 |

Enolasea |

755 |

904.8633 |

CDS |

|

Down-regulated miRNAs by -Pi | |||||

| miR159e-3p |

Glyma13g25716.1 |

Myba |

1340 |

97.459 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma15g35860.1 |

Myba |

937 |

198.4836 |

CDS |

| miR169c |

Glyma10g10240.1 |

NF-YAc,d |

1174 |

|

3’UTR |

| miR169r |

Glyma18g07890.1 |

NF-YAb |

949 |

|

CDS |

| miR2109 |

Glyma16g29650.1 |

Heavy-metal-associated domaina |

297 |

56.653 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma16g33950.1 |

Leucine-rich repeat-containing proteina |

86 |

25.3552 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma16g33980.1 |

Plant basic secretory proteina |

833 |

51.8989 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma16g34060.1 |

transmembrane receptor activitya |

185 |

28.9208 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma16g34060.2 |

transmembrane receptor activitya |

185 |

28.9208 |

CDS |

| miR3522 |

Glyma07g31270.1 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF_B2219)/Polyphenol oxidase middle domainc |

418 |

|

CDS |

| miR4376a |

Glyma09g36420.1 |

F-box/LRRc |

1297 |

|

|

| miRnov_5a |

Glyma06g08730.1 |

No annotationa |

681 |

60.2186 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma06g08730.2 |

No annotationa |

926 |

60.2186 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma06g08730.4 |

No annotationa |

968 |

318.9207 |

CDS |

| miRnov_5b |

Glyma06g08730.1 |

No annotationa |

681 |

60.2186 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma06g08730.2 |

No annotationa |

926 |

60.2186 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma06g08730.4 |

No annotationa |

968 |

318.9207 |

CDS |

| miRnov_6a |

Glyma05g07780.1 |

DEAD/DEAH box helicasea |

1019 |

19.8087 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma06g23290.1 |

DEAD/DEAH box helicasea |

1036 |

19.8087 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma14g40680.1 |

EamA-like transporter familya |

818 |

72.1038 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma17g13230.1 |

DEAD/DEAH box helicasea |

268 |

47.9372 |

CDS |

| |

Glyma18g22940.1 |

DEAD/DEAH box helicasea |

1005 |

19.8087 |

CDS |

| miRnov_9 |

Glyma05g00880.1 |

Sensor histidine kinase-relatedb |

1165 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma04g39860.1 |

Peroxidaseb |

260 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma06g15030.1 |

Peroxidaseb |

256 |

|

CDS |

| miRnov_10 |

Glyma08g20840.1 |

Dof domain, zinc fingerb |

1001 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma20g26290.1 |

Cyclinb |

895 |

|

CDS |

| |

Glyma10g40990.1 |

Cyclinb |

626 |

|

CDS |

| Glyma13g17410.1 | CAAX amino terminal protease family alpha/beta hydrolase domain containingb | 3678 | CDS | ||

The potential targets of soybean P-responsive miRNAs in leaves and roots were predicted by degradome sequencing and computationally using Pairfinder and psRNAtarget. The Glycine max transcriptome is available in Phytozome ( http://www.phytozome.org). For conserved miRNAs, homology of which can be found in other plant species apart from legume; for less-conserved miRNAs, homology of which can be found in legume (legume-specific); for novel miRNAs, which were not previously in miRBase and not assigned into any family were denoted by miRnov (soybean-specific).

a: predicted from degradome;

b: predicted with Pairfinder developed by BGI ( http://www.bgi.cn);

c: predicted from psRNAtarget ( http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/?function=3);

d: experimentally confirmed target [20,27,28].

AP2, AP2 domain protein; CDS: coding sequence; Cleavage site: nucleotide position in cDNA cleaved by miRNA from 5’ to 3’; Myb, Myb family of transcription factors; NF-Y, NUCLEAR FACTOR Y (also CCAAT, CCAAT-binding transcription factor); TP10M: transcripts per 10 million reads; UTR: untranslated region.

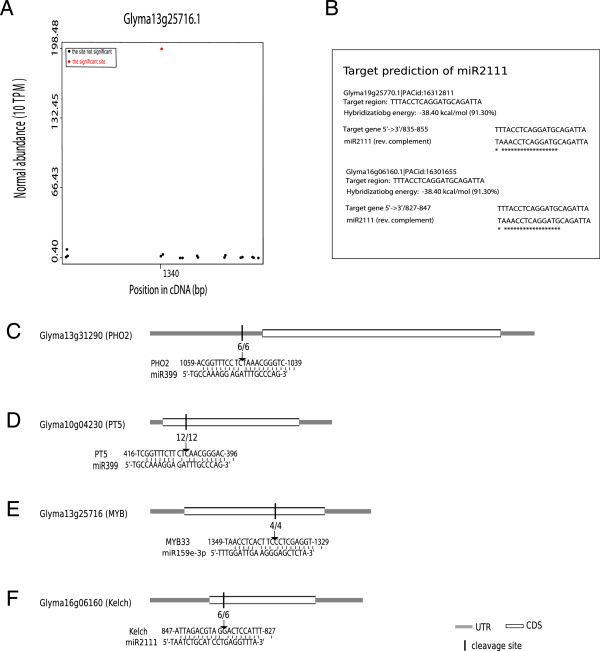

Determination of targets of miR399, miR2111, and miR159e-3p through RLM-5’ RACE

To test the accuracy of target gene cleavage site location results, RLM-5’ RACE was compared with predictions. The cleavage site of miR399 in PHO2 is predicted to occur at position 1050, and in Glyma10g04230 at position 407 (Additional file 7). Figure 6A shows the putative cleavage site of miR159e-3p in the target gene Glyma13g25716 at position 1340 as determined through degradome sequencing. In addition, Figure 6B shows the cleavage sites of miR2111 in two target genes, Glyma19g25770 and Glyma16g06160, as predicted with WMD3 ( http://www.weigelword.com). RLM-5’ RACE has been successfully employed to determine cleavage sites of miRNAs in soybean [20,27]. In this study, RLM-5’RACE using RNA from Pi-depleted roots confirmed the cleaved fragments of GmPHO2 (Glyma13g31290) and GmPT5 (Glyma10g04230) mRNA predicted previously (Figure 6C, D). The experimentally determined cleavage site of miR159e-3p in Glyma13g25716 (Figure 6E) matched the predicted site, and the cleavage site in Glyma16g06160 predicted with WMD3 (Figure 6F). These results indicate that degradome sequencing and computational predictions can reliably predict miRNA interactions with target genes.

Figure 6.

Confirmation of the targets of miR399, miR2111, and miR159e-3p by RLM-5’ RACE. Degradome sequencing analysis indicating a cleavage site at position 1050 from the 5’ end of the transcript of Glyma13g25716.1 is targeted by miR159e-3p (A). Target prediction of miR2111 with WMD3 (http://www.weigelworld.com) showing Glyma19g25770 and Glyma16g06160 as putative targets of miR2111 (B). Cleavage sites from the 5’ end for Glyma13g31290 (PHO2-1) by miR399 (C), GmPT5 by miR399 (D), Glyma13g25716 by miR159e-3p (E), and Glyma16g06160 by miR2111 (F). The arrow indicates the cleavage position in the transcript of target genes, and the number above the arrow shows the sequenced clone numbers of PCR products.

Possible functions of soybean miRNAs’ targets

A total of 154 target genes were identified through degradome sequencing and computational predictions (Additional files 7, 8 and 9). To better understand the biological functions of these genes in soybean, GO analysis [29] was employed to classify target genes based on their involved biological processes.

As shown in Additional file 10, a total of 154 target genes are positively or negatively involved in many biological processes in soybean. For instance, target genes positively regulate the following processes: (1) nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolic process (45/154, GO:0019219); (2) RNA metabolism (35/154, GO:0051252); (3) gene expression (49/154, GO:0010468); (4) macromolecule biosynthetic process (46/154, GO:0010556); (5) meristem development (10/154, GO:0048509). On the other hand, target genes negative regulate these processes: (i) seed development (31/154, GO:0048316); (ii)shoot development (25/154, GO:0048367);(iii) root development (19/154, GO:0048364); (iv) meristem initiation (10/154, GO:0010014). These results indicate the important roles of target genes in soybean in response to Pi starvation.

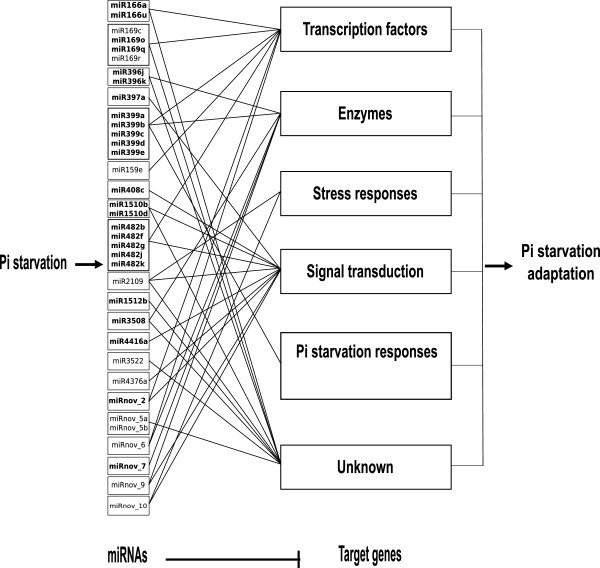

A more narrow focus on the targets of -Pi induced and repressed miRNAs returns functions that can be grouped into several categories based on the involved processes (Table 6). These include: (i) protein synthesis or degradation; (ii) P uptake and transport; (iii) stress-related processes; (iv) cell division; and (v) ROS homeostasis. These results indicate that complex networks of P signaling are present in soybean. Figure 7 outlines the possible functions of P-responsive miRNAs and their target genes.

Figure 7.

Possible functional networks for P-depletion responsive miRNAs in soybean. Relationships between 25 P-depletion induced and 11 P-depletion repressed miRNAs and their target genes shown based upon putative physiological functions. Bold font and normal font indicate -Pi induced or repressed miRNAs, respectively.

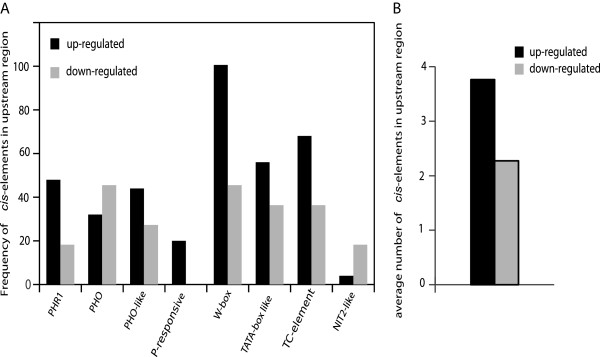

cis-element analysis in the promoter of P-responsive miRNAs

AtPHR1 binds the promoter region of miR399 in Arabidopsis [30], indicating control of miRNA expression by TFs. cis-element analysis shows that TATA-box and TSS elements in the pre-miRNA upstream region can be found in over 90% of miRNA genes (Additional file 11). A total of 270 TSSs and 230 TATA-boxes were found in the promoters of 126 soybean miRNA genes (Additional file 11), with more TSSs and TATA-boxes found within 1.0 kb upstream of pre-miRNA than in the 1.0 to 2.0 kb upstream region (Additional file 12).

Several well-defined Pi-responsive cis-elements were selected as references to identify P-responsive cis-elements potentially regulating the currently studied miRNAs [31]. A total of 377 Pi-responsive elements were detected for 126 miRNA genes, the average number of cis-elements was 3.02 (Additional file 13). Among them, miR156w, miR156x, miR166g, miR168c and miR168d all contained 8 cis-elements, and miR166a-5p harbored nine. Genes for miR399a, miR399b, miR399d and miR399e had PHR1 binding sites, but miR399c only had a W-BOX binding site (Additional file 13), indicating the expression of miR399a, b, d, and e might be regulated by PHR1 in soybean. The average frequency of PHR1, PHO-like, Pi-responsive, W-box, TATA-box, and TC elements in -Pi-induced miRNA promoter regions was higher than that in the -Pi-depressed miRNA promoter region, while the frequency of PHO and NIT2 elements was lower in the Pi-induced miRNA promoter regions than that in the -Pi- depressed miRNA promoter regions (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Frequency of P-responsive cis-elements in the promoter regions of P-responsive miRNAs. Frequency of cis-elements types (A), and average number of cis-elements per upstream region (B) from 25 up-regulated and 11 down-regulated miRNA genes differentially expressed in -Pi relative to +Pi.

Discussion

Deep sequencing of small RNAs and RNA degradome in soybean

Soybean is an important crop that provides oils and proteins to human and animals. Little is known about the involvement of miRNAs in soybean leaf and root development, and P signaling. Although high-throughput sequencing has been employed to reveal soybean miRNAs [20], there are likely many miRNAs to still be found. SBS has been successfully employed to find miRNAs genome-wide in rice [32] and Glycine max[20]. Figure 1 shows a major peak at 21 nt in the total small RNAs from four small RNA libraries. A peak at 19 nt found in Arabidopsis root libraries [10] was not found in the current study. On the other hand, our data identify 24 nt unique small RNA species as dominant over other kinds of small RNAs in four small RNA libraries, which is consistent with previous studies [10,20,23]. One possible reason for the prevalence of 24 nt small RNAs is that most precursors of siRNAs are processed into 24 nt-long siRNAs by DCL3 [1]. In regards to nutrient effects, it has been reported that P availability does not change total small RNA profiles in rice leaf libraries [23]. This is consistent with the results reported here (Figure 1), but it does not address the fact that a number of individual miRNAs are differentially expressed among P treatments (Figures 2, 3 and 4). Hsieh et al. [10] (2009) reported that more than 24% of small RNA reads mapped to tRNA in the Arabidopsis genome in two root libraries, while the percentage in leaf libraries is lower [10]. This high percentage of tRNA in root libraries was not observed in soybean (Additional file 2). In conclusion, the profiles of total small RNA in plants are dependent on plant species, tissue type and environmental conditions.

Since 2008, degradome sequencing has been employed to screen Arabidopsis miRNA targets [33]. A total of 174 genes targeted by 87 unique miRNAs were identified in rice cultivar 93-11 from a young panicles degradome library [32]. Here, degradome sequencing detected 71 genes to be cleaved by conserved, less-conserved, and novel soybean miRNAs. RLM-5’ RACE has confirmed the targets of miR166g, miR168 and miR169c in previous work [20,27,28], as well as the targets of miR399, miR2111 and miR159e-3p in this study. Moreover, the cleavage sites were in accordance with predictions or degradome sequencing (Additional file 7). This indicates that degradome analysis is a powerful tool to find soybean miRNA targets. The limitation of this study is that just one degradome small RNA library was produced from Pi-starved roots. MicroRNA-degraded fragments existing specifically in leaves or other organs above the roots were not sequenced. Nevertheless, using a combination of experimental and computational approaches, 95 new targets for conserved, less-conserved, and novel miRNAs were putatively identified here. Accordingly, identification of more targets of soybean miRNAs will shed fresh light on the functions of soybean miRNAs in the near future.

Discovery of conserved, less-conserved, and novel miRNAs in soybean

Presently, a total of 395 soybean mature miRNAs (362 precursors) were curated in miRBase 18.0. In this study, we adopted very strict criteria to determined candidate miRNAs as outlined above. Interestingly, in contrast to previous studies [20,34,35], 62 of the conserved miRNAs (Table 3), 18 of the less-conserved miRNAs (Table 4), and 12 of the novel soybean-specific miRNAs (Table 5) were new discoveries in soybean. A possible explanation for these discoveries is the sampling of tissues from multiple time points and treatments. RNA was sampled from leaves and roots at different time points and P treatments, which increases the odds of finding previously unreported miRNAs in soybean.

Our results significantly improve our understanding of miRNA families. The first to mention is the miR156 family, which is big and conserved across plants, including 12 miR156 members in both Arabidopsis and rice, 11 members in maize, and 8 in Medicago ( http://www.phytozome.org). Here, the soybean miR156 family members have been expanded from 15 to 29 (Table 3). In addition, 11 miR166s were identified for the first time (Table 3), indicating that miR166 is also a very big miRNA family in soybean. We note that as an ancient polyploidy descendent, the genome of Glycine max was duplicated two times, 59 and 13 million years ago [36]. These events likely led to significant increases in the two miRNA families listed above, as well as, potentially increasing membership in other families. Furthermore, miR1507, miR1509, and miR1510 were identified, and to date, have only been found in Medicago and soybean (Table 2). In short, the known sizes of soybean miRNA families were significantly expanded through this study. However, we did not detect miR157, miR393,miR395, or miR398 as previously reported. Possible explanations are that (i) strict criteria were implemented in this study for identification of mature miRNAs; and (ii) the RNA samples were limited to low P-stressed leaves and roots, along with their control, so -S-induced miR395 and -Cu-induced miR398 were not likely to be detected.

miRNAs in soybean leaves and roots