Abstract

Both endogenous and exogenous factors can induce DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in oocytes, which is a potential risk for human-assisted reproductive technology as well as animal nuclear transfer. Here we used bleomycin (BLM) and laser micro-beam dissection (LMD) to induce DNA DSBs in germinal vesicle (GV) stage oocytes and compared the germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) rates and first polar body extrusion (PBE) rates between DNA DSB oocytes and untreated oocytes. Employing live cell imaging and immunofluorescence labeling, we observed the dynamics of DNA fragments during oocyte maturation. We also determined the cyclin B1 expression pattern in oocytes to analyze spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) activity in DNA DSB oocytes. We used parthenogenetic activation to determine if the DNA DSB oocytes could be activated. As a result, we found that the BLM- or LMD-induced DSB oocytes showed lower GVBD rates and took a longer time to undergo GVBD compared with untreated oocytes. PBE was also delayed in DSB oocytes, but once GVBD had occurred, PBE was not affected, even in oocytes with severe DSBs. Compared with control oocytes, the DSB oocytes showed higher SAC activity, as indicated by less Ccnb1-GFP degradation during metaphase I to anaphase I transition. Parthenogenetic activation could activate the metaphase to interphase transition in the DNA DSB mature oocytes, but many oocytes contained multiple pronuclei or numerous micronuclei. These data suggest that DNA damage inhibits or delays the G2/M transition, but once GVBD occurs, DNA-damaged oocytes can complete chromosome separation and polar body extrusion even under a higher SAC activity, causing the formation of numerous micronuclei in early embryos.

Keywords: double-strand breaks, oocyte, meiosis, spindle assembly checkpoint, Ccnb1, polar body extrusion

Introduction

Cellular DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) can be induced by endogenous metabolites or metabolic intermediates1 as well as by exogenous factors like UV A (UV-A, wavelength: 315–400 nm, included in the solar spectrum), ionizing radiation (including X-rays and γ-rays), chemical drugs (such as the drug for cancer chemotherapy: doxorubicin2) and physical inducers. In mammals, there are two programmed DNA DSBs that occur during meiotic recombination in germline cells or during gene rearrangements in immunocytes.3-6 In addition, DSBs also occur in cleavage stage embryos, which can be repaired and does not change the genome sequence, although we do not yet understand its biological function.7,8 Unlike programmed DNA damage, the abnormal DSBs of cellular DNA, if not repaired immediately, can induce chromatin remodeling,9 cell cycle arrest, cell cycle delay, apoptosis or other forms of cell death.3,10,11 The DSBs in cells are typically sensed and repaired by the DNA damage checkpoint, which can take place during three specific cell cycle stages: G1/S, S and G2/M 3. First, the DSBs are mainly sensed by the ataxia telangiectasia mutated homolog protein (ATM). The ATM then directly or indirectly phosphorylates more than 30 targets such as the checkpoint kinase 2 (Chek2), DNA-PK and Mre11-complex.12,13 The Chek2 pathway is activated to arrest the cell cycle, and the DNA-PK and/or Mre11-complex pathway is activated to repair the damaged DNA.13 When DSBs are repaired, the checkpoint proteins become inactivated and cell cycle progression resumes.14

During mouse oogenesis, the DNA DSBs occur mainly at the pachytene stage oocytes of the 14–20 d post-coitum fetus.15 The DNA DSB lesions in pachytene phase oocytes are repaired by homologous recombination during which homologous chromosomes form synaptonemal complexes.16 After homologous recombination, oocytes are arrested at the diplotene stage until meiosis re-initiation takes place, which is stimulated by gonodotropin hormone at the germinal vesicle (GV) stage. By immunofluorescence labeling, untreated GV stage oocytes showed no or few γH2AX signals (marker of DNA DSB),17,18 indicating that DNA DSBs are uncommon in in vivo oocytes. Very recently, to investigate the DSB effects on oocyte meiotic maturation, the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide and ionizing radiation mimetic neocarzinostatin (NCS) have been used to induce DSBs in mouse GV oocytes. Etoposide-treated oocytes showed lower meiosis resumption with increasing doses.17 The NCS-treated oocytes showed normal maturation rates, but the polar body extrusion rates were decreased. If the NCS dose was increased to a higher level (> 0.3 µg/ml), the oocytes became mostly arrested in meiosis I.18

In our experiments, we employed chemical and physical treatments. We used the chemical bleomycin (BLM, an antineoplastic drug used in clinical applications), and we used laser micro-beam exposure as physical treatment to induce DNA DSBs in GV oocytes. Both germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) rates and first polar body extrusion (PBE) rates were assessed. We also used the live cell imaging system to observe the dynamics of fragmented DNA during oocyte maturation and evaluated the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) activity of DNA DSB oocytes by detecting exogenous cyclin B1 degradation. Finally, we did parthenogenetic actication of the metaphase II (MII)-stage DNA DSB oocytes.

Results

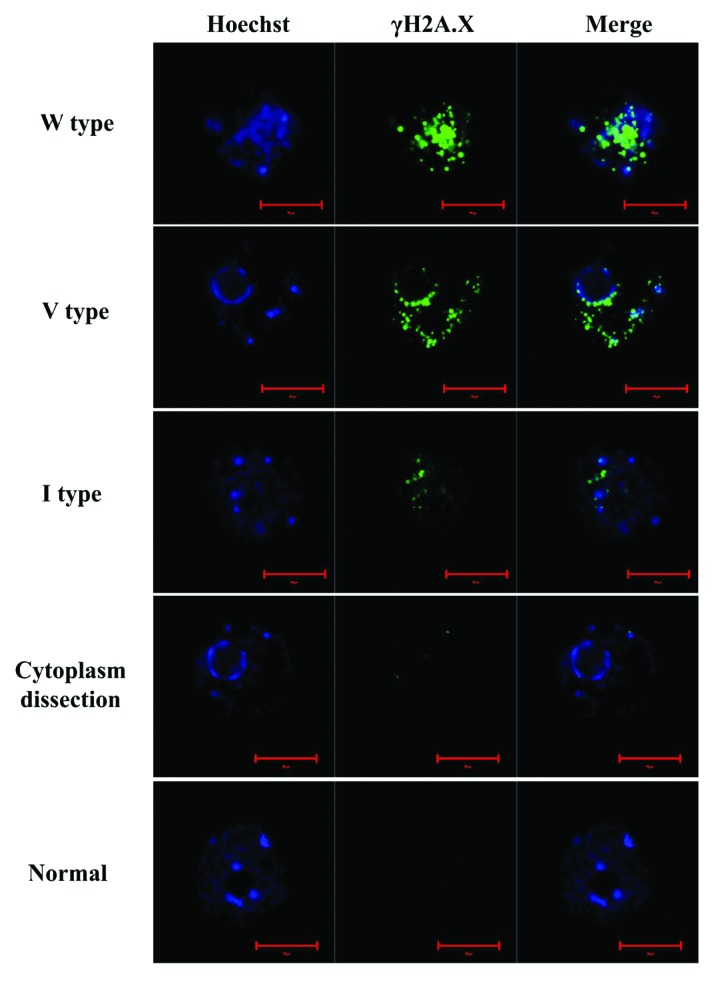

GV oocytes with double-strand broken DNA developed to MII stage

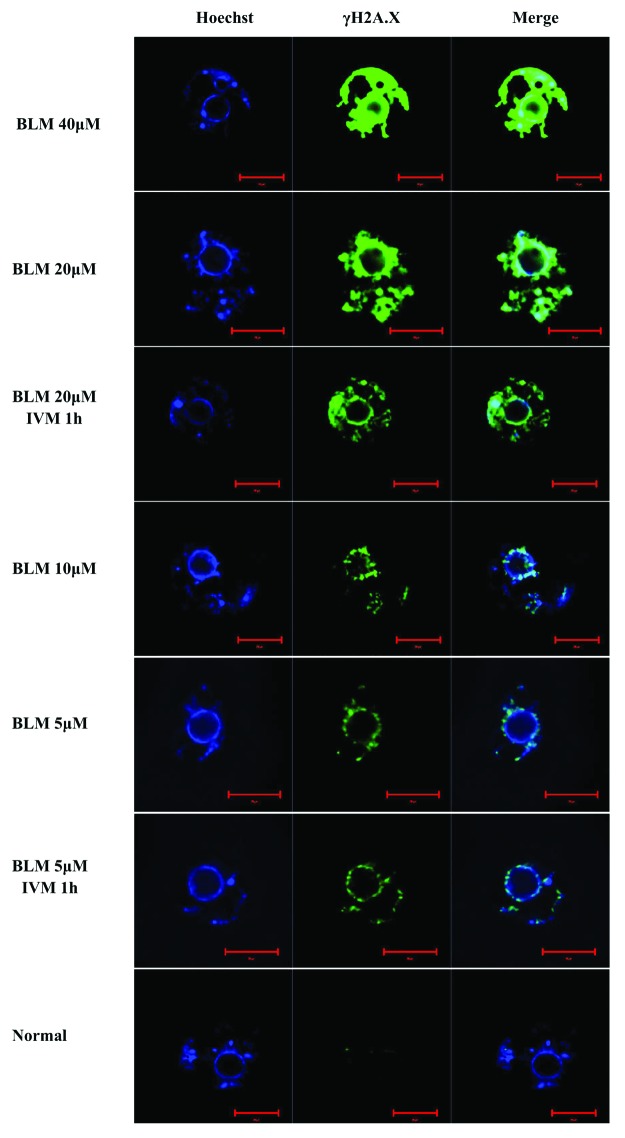

Oocytes were treated with different concentrations of BLM (0, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM) for 1 h to induce DNA DSBs. DNA DSB lesions were detected by immunofluorescence labeling with γH2A.X antibody. We found that the γH2A.X signal levels were only very weak in normal oocytes but became elevated with increased BLM concentrations. We also labeled the γH2A.X in 5 or 20 µm BLM-induced DSB oocytes 1 h of in vitro maturation (IVM), and found that the γH2A.X signals displayed no significant difference after IVM (Fig. 1). Unlike the DNA lesions induced by chemical drugs, the DNA DSBs that were physically induced by laser micro-beam were not of global scale. We used the laser microdissection (LMD) system to create three different lesions lengths: I type, ~20 µm; V type, ~40 µm; and W type, ~80 µm. Untreated oocytes and oocytes whose cytoplasm was microdissected were used as control groups (see “Materials and Methods”). Both DNA DSB oocytes and control group oocytes were labeled with the γH2A.X antibody. We also found that the DNA damage levels of LMD-dissected oocytes increased with increased length of exposure time to the micro beam length (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. DNA double-strand break (DSB) damage in the nucleus (blue) increased with elevated concentration of bleomycin (BLM). BLM mainly induced DSBs on DNA; and γH2A.X (green), the protein marker of DSB. To detect if the DSBs could be repaired during in vitro maturation (IVM), we also labeled γH2A.X in IVM oocytes. As a result, the γH2A.X signals showed no significant difference after IVM (BLM 20 µM IVM 1 h and BLM 5 µM IVM 1 h). **, significant difference. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Figure 2. DNA double-strand break (DSB) damage in the nucleus (blue) increased with elevated length of laser micro-beam dissection (LMD). We used normal oocytes and oocytes with dissected cytoplasm as control groups. The LMD length was ~20 µm (I type), ~40 µm (V type) and ~80 µm (W type), respectively. Green, γH2A.X, the protein marker of DSB; blue, nucleus. Scale bar: 20 μm.

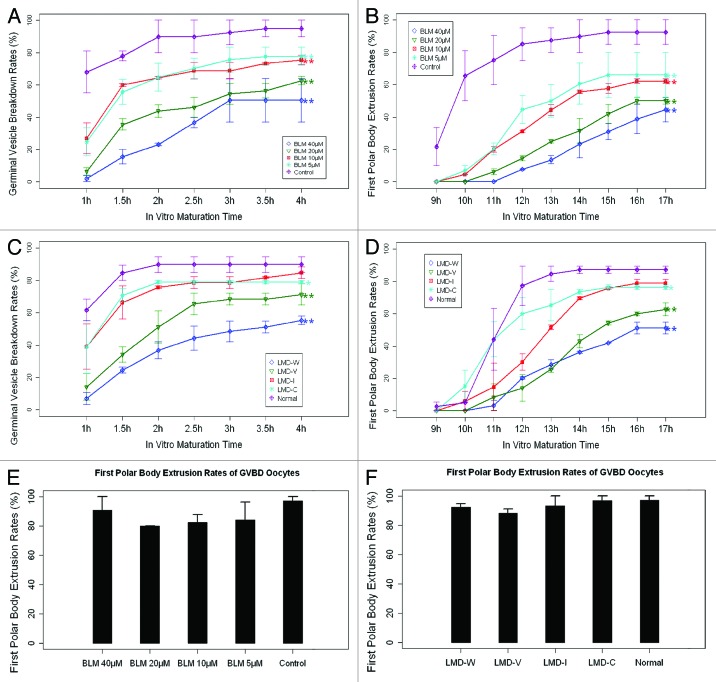

When cultured in vitro, the GVBD rates decreased, while the GVBD time increased with lesions increases in both BLM- and LMD-induced DNA DSB oocytes compared with the control groups (Fig. 3A and C). The time of PBE for the DNA DSB oocytes was also longer compared with control oocytes (Fig. 3B and D). However, the PBE rate of the GVBD oocytes with DNA DSBs did not show a significant difference when compared with the control oocytes (p > 0.05, Fig. 3E and F).

Figure 3. Germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) rates and polar body extrusion (PBE) rates of bleomycin (BLM) and laser micro-beam dissection (LMD) induced DNA double-strand broken (DSB) oocytes. (A) GVBD rates of BLM induced DSB oocytes. (B) PBE rates of BLM induced DSB oocytes. (C) GVBD rates of LMD induced DSB oocytes. (D) PBE rates of LMD induced DSB oocytes. (E) PBE rates of the BLM induced DSB oocytes in which the germinal vesicle had broken down. (F) PBE rates of the LMD-induced DSB oocytes in which the germinal vesicle had broken down. Chi square test was used in (A–D). Fisher exact test was used in (EandF).

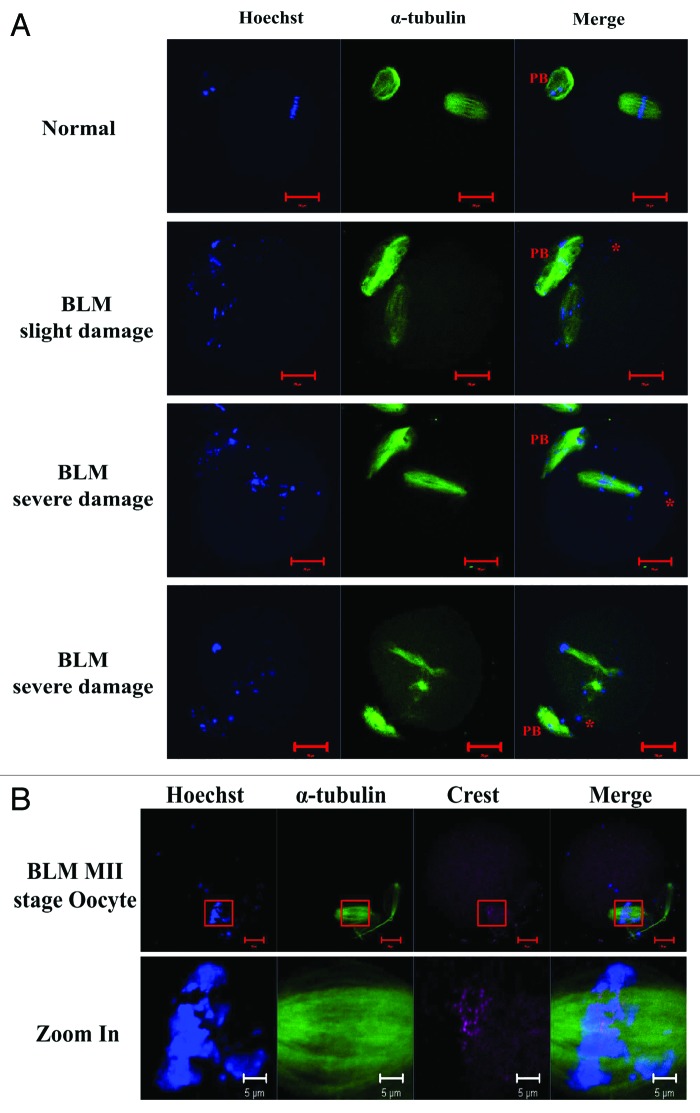

Chromosome fragmentation did not affect polar body extrusion of oocytes

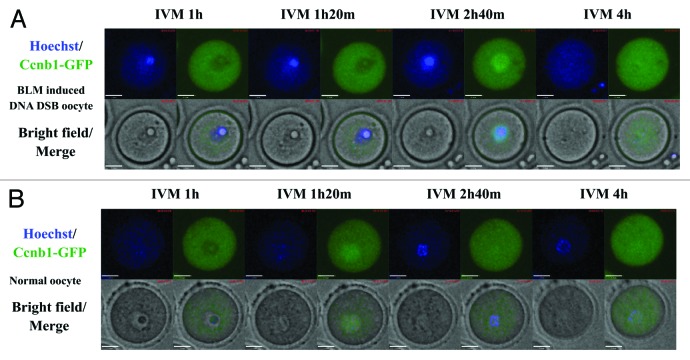

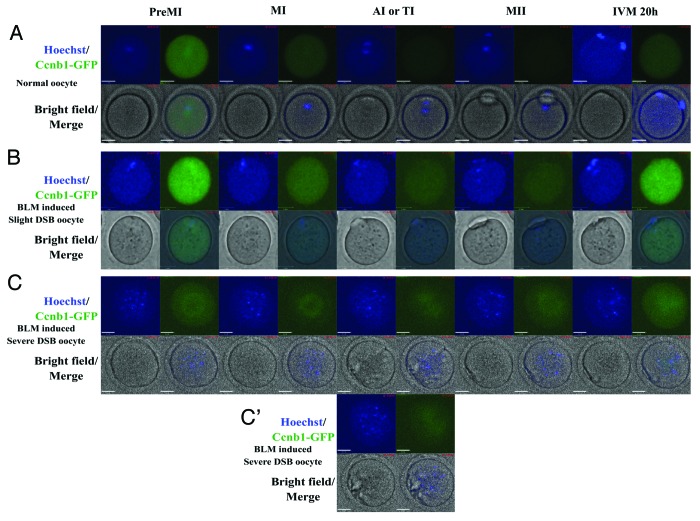

We examined the fates of DSB-induced DNA fragments during oocyte maturation. In live cell observations, we found that the extreme DNA DSBs could induce formation of chromosome fragments dispersed in the ooplasm after GVBD (Fig. 4). The dispersed DNA fragments were able to aggregate, but the aggregation of DNA was not essential for the polar body extrusion (Figs. 3, 5 and 6A). If the DNA was severely damaged, the separated chromosome fragments could even induce multiple spindle formations (Fig. 6A).

Figure 4. Time-lapse imaging of nuclear Ccnb1 expression, GVBD and chromatin organization in oocytes. (A) Bleomycin (20 µM) induced DSB oocytes, the chromatin condensed before GVBD and dispersed after GVBD. (B) Normal oocytes, the chromatin condensed before GVBD but continuously assembled after GVBD. Exogenous Ccnb1-GFP (green) was expressed in GV oocytes to trace the endogenous Cyclin B1 localization. We found that Ccnb1-GFP entry into the nucleus of DSB oocytes occurred later compared with normal oocytes, and the GVBD of DSB oocytes was also delayed.

Figure 5. Time-lapse imaging of Ccnb1 expression during oocyte maturation from pre-metaphase I (MI) to metaphase II (MII) stage. (A) Normal oocyte. Ccnb1 was degraded during MI to anaphase I (AI) transition in normal oocytes. (B) Oocyte with slight DNA double-strand breaks induced by 20 µM BLM. Ccnb1 was degraded at MI stage and resumed to the same level at the MII stage. (C and C’) Oocyte with severe DNA double-strand breaks induced by 20 µM BLM. The chromosome fragments dispersed in the ooplasm. There was no obvious degradation of Ccnb1 in the severe DSB oocytes. TI, telophase; IVM, in vitro maturation.

Figure 6. Metaphase II stage oocytes matured in vitro. (A) The chromosome fragments and spindle in DNA double-strand broken oocytes and normal oocytes. When the DNA was slightly damaged, most chromosome fragments clustered in the spindle apparatus. When DNA was severely damaged, numerous chromosome fragments dispersed into the cytoplasm, which even induced multiple spindle apparatus formation (image below). Both the slight and severe DNA damage were induced by 20 µM BLM. (B) Crest dot (centromere marker) localized at the spindle region. BLM, bleomycin. Red scale bar, 20 µm; white scale bar, 5 µm.

Chromosome fragments with centromeres localized at the spindle region

We then labeled the centromeres on chromosome fragments in DNA DSB oocytes. As a result, we did not find the Crest dot on the chromosome fragments that were dispersed outside the spindle region. We found that the chromosome fragments with centromeres (marked by the Anti-Crest antibody) were distributed at the spindle region (Fig. 6B), which indicated that the formation and function of the spindle apparatus did not require chromosome integrity.

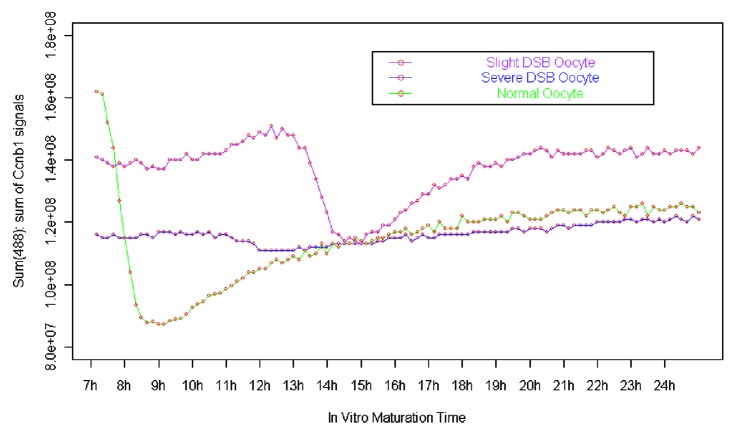

Lower cyclin B1 degradation in DNA DSB oocytes

SAC is mainly controlled by the APC/C complex. When homologous chromosomes neatly arranged at the central plate of the spindle, the protease activity of APC/C was released and securin and cyclin B1 could be degraded by APC/C,19 inducing the separation of homologous chromosomes.20 We used exogenous Ccnb1-GFP to trace the dynamic change of endogenous cyclin B1 and to analyze the activity of APC/C or SAC. In the oocytes whose DNA was severely broken (shown as blue line in Fig. 7), the Ccnb1-GFP signal became weaker before polar body extrusion. But the degradation of Ccnb1 was not as obvious as that of normal oocytes (Figs. 5 and 7). In the slight DSB oocytes whose chromosomes could aggregate, the Ccnb1-GFP signal showed an obvious decrease before chromosome separation, but compared with the normal oocytes, the Ccnb1 degradation was not only delayed but also showed a small decrease rate (25.2% of Ccnb1-GFP signal decrease in slight DNA DSB oocytes and 46.2% of Ccnb1-GFP signal decrease in normal oocytes, Fig. 7). After the MI-to-anaphase transition, the Ccnb1 in normal oocytes increased slowly and stabilized at a level lower than observed for the MI stage. However, in the slight DSB oocytes, the Ccnb1 increased relatively fast to reach the plateau phase (about 4 h for the slight DSB oocytes, about 8 h for the normal oocytes, Fig. 7).

Figure 7. The dynamics of Ccnb1-GFP fluorescence signals of normal oocytes and bleomycin (BLM)-induced DSB oocytes.

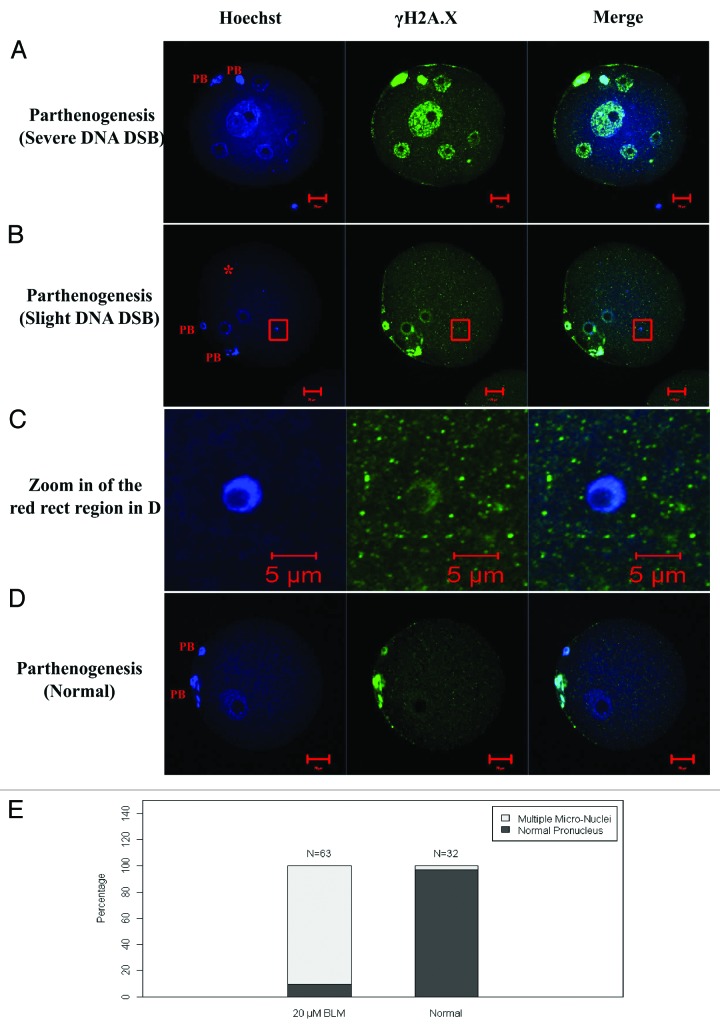

DNA DSB oocytes could be activated by parthenogenetic activation

The parthenogenetic activation rate as indicated by the formation of pronucleus or micronucleus in DNA DSB oocytes showed no difference compared with normal control oocytes. We stained the DNA and labeled γH2A.X in the 1-cell embryos (Fig. 8), and found that the 1-cell embryo containing multiple micronuclei, with some of them displaying micronucleoli. When the DNA was severely damaged, there were more micronuclei in the 1-cell embryos and vice versa (Fig. 8A and B). We also found that the DNA DSBs induced in GV oocytes were inherited and displayed in the 1-cell embryos (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Parthenogenetic activation of DNA double-strand broken (DSB) oocytes. (A and B) Parthenogenetically activated DNA DSB oocyte. There were multiple micronuclei in (A and B). (C) Zoom in of the red square region of (B), showing the micronucleolus in the micronucleus of (B). (D) Parthenogenetically activated control oocyte. (E) the percentage of oocytes containing multiple micronuclei in 20 µM BLM induced DNA DSB oocytes and normal control oocytes. PB, polar body. Scale bars in (A, B and D), 20 µm; scale bars in (C), 5 µm.

Discussion

In this study, we used BLM and LMD (LMD was previously used in somatic cells to induce DSBs)21 to induce DSBs in oocytes and revealed a new perspective regarding DNA damage and oocyte maturation. First, the integrity of oocyte chromosomes is not pivotal for spindle formation and polar body extrusion. Second, we found that the SAC signaling was independent of/uncoupled from the chromosome position/integrity. Third, we also found that the formation of the pronucleus in 1-cell embryos did not depend on the integrity of the genome. Our results also indicate that the antineoplastic drug BLM and UV-A present potential risks for oocytes, which calls for caution regarding ovary exposure when performing therapy or surgery.

In a very recent report, ATM was activated in severe DSB oocytes and the active ATM phosphorylated the checkpoint kinase 1 (Chek1) but not Chek2 in oocytes and blocked the oocytes at the GV stage.17 The Chek1 kinase is mainly responding to single-strand breaks (SSBs), and overexpression of Chek1 in GV oocytes could arrest oocytes at the GV stage.22 Goodarzi et al. proposed that the DSB repair pathway was controlled by the chromatin structure.23 However, we still do not understand SSBs in oocytes and the mechanisms by which ATM may activate Chek1. The data showing that only severe DSB damage could activate the checkpoint kinase indicates that the DSB damage sensor or transducer may be lacking to some extent in oocytes. Currently, assisted reproduction technologies (ART) are being widely used in humans. During 2008 in Europe, there were 350 143 clinical treatment cycles for ART, in which about 14 thousand cycles were associated with oocyte donation, in vitro maturation and frozen oocyte replacements.24 Because it is difficult to monitor DSB damage during oocyte maturation,25 caution is necessary to protect oocytes from endogenous1 or exogenous factors that could induce potential DNA DSBs (like X-rays, sunlight, reactive oxygen species and physical or chemical direct injury) to avoid increasing the failure rates of assisted reproduction and/or disease that may affect the new life. Special attention should be paid regarding the effects of DNA damage during oocyte maturation and manipulations in vitro. In addition, the cancer chemotherapy drug doxorubicin could also induce the ovary and oocyte DNA DSB, which is a problem that needs to be solved.2

The SAC is essential for the oocyte’s transition from MI to anaphase I.20 An active SAC blocks the oocyte at the pre-MI stage until all homologous chromosome pairs are arranged accurately at the equatorial plate, which then silences the activity of SAC.26 The silencing of SAC is mainly associated with the separation of SAC proteins such as Mad2, BubR1 and Bub3 from kinetochores. When overexpressing Mad2, BubR1 or Bub3, oocytes arrest at the pre-MI or MI stage, even if all chromosomes are arranged accurately at the equatorial plate.27-29 When SAC is silenced, the protease APC/C complex is activated, which induces the degradation of cyclin B1 and the separation of homologous chromosomes.30 The delay of cyclin B1 degradation indicated that the arrangement of the chromosome fragments with centromeres took a longer time in the oocyte compared with the arrangement of normal homologous chromosomes. However, broken chromosomes were still able to separate. In addition, the low degradation degree of cyclin B1 indicated that the APC/C had not been fully activated in DSB oocytes. Previous reports showed that although polar chromosomes existed in CENP-E-depleted oocytes, Mad2 could still separate from kinetochores.31 In addition, the erroneous attachments of bivalent kinetochores to microtubules could not promote SAC to prevent APC/C from degrading cyclin B1 and the oocyte transition from metaphase to anaphase with polar chromosomes.32 In our study, we found that the degradation of cyclin B1 was not essential for the MI to anaphase I transition even when the chromosomes were severely damaged. De Souza et al. had described that, when the SAC proteins accumulated at the kinetochores for a prolonged time, the SAC could be inactivated automatically, whereas the APC/C would be activated and degrade the SAC proteins.33 However, in our results, the APC/C showed decreased activity on cyclin B1, indicating the APC/C in DSB oocytes has not been fully activated. In Marangos and Carroll’s results, DSB oocytes could be blocked at the GV stage only if the DNA was damaged severely to activate the activity of the DNA breaks sensor ATM.17 Both Marangos and Carroll’s and our results showed that compared with somatic cells, the oocyte cell cycle is less sensitive to DNA DBSs.

By parthenogenetic activation, we found that very small or only a few chromosomes or chromosome fragments had similar potential to form a pronucleus or micronuclei. We do not yet know whether this characteristic is specific for oocytes. Most DNA breaks in somatic cells, as far as we know, induce growth arrest, apoptosis or cancer.34 It will be of interest to fully determine the difference between germ cells and somatic cells regarding supervision of genome integrity.

In summary, by using BLM and LMD to induce DNA DSBs, we find that DNA damage may inhibit or delay the G2/M transition during oocyte meiotic maturation, depending on the degree of DSBs. Once GVBD occurs, chromosome fragmentation does not affect spindle organization, chromosome fragment separation and polar body extrusion.

Materials and Methods

All animal manipulations were performed according to the guidelines of animal cares and manipulations of the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Oocyte collection and in vitro maturation

Germinal vesicle stage oocytes were isolated from ovaries of 8–10-week-old female mice. Isolated GV stage oocytes were blocked at the GV stage in M2 medium plus 2.5 µM milrinone. For in vitro maturation of oocytes, GV oocytes were cultured in fresh M2 medium for 13 to 17 h.

Immunofluorescence labeling

Antibodies used for immunofluorescence labeling were: γH2A.X, P-Histone H2A.X (S139) (BS4760, Bioworld); Crest, Centromere antiserum (90C-CS1058, fitzgerald); FITC-α-tubulin antibody (F2618, Sigma). To label the γH2A.X or α-tubulin, oocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 40 min followed by permeabilization in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Next, oocytes were blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA for 1 h and then incubated with γH2A.X antibody at 4°C overnight, washed three times and incubated with the second antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Then the oocytes were washed three times and stained with Hoechst 33342. For labeling with Crest antibody, the oocytes were fixed with 3.8% PFA containing 0.024% Triton X-100 for 40 min at room temperature and processed using the same procedure as described above.

DNA DSBs induced by laser microdissection or bleomycin

The GV stage oocyte DNA DSBs were induced by two individual methods: laser microdissection and chemical drug BLM. The Zeiss Laser Capture Microdissection system was used for laser (337 nm) microdissection of the germinal vesicle to induce DNA DSBs. The parameters used for microdissection were: speed percent, 5; microBeam cut energy, 50; LPC energy, 16; Focus, 76; and Focus Delta, 3. Normal oocytes and oocytes microdissected in the cytoplasm were used as control. When DNA DSBs were induced by BLM, the GV oocytes were blocked in M2 medium with 25 µM milrinone and 0, 5, 10, 20 or 40 µM BLM for 1 h. Then, the oocytes were washed and cultured in M2 medium for further analysis.

Cyclin B1-GFP cRNA micro-injection of GV-stage oocytes

The coding region sequence of cyclin B1 (Ccnb1) was linked by restriction enzyme sites of XhoI and BamHI and then linked to the GFP plasmid. The Ccnb1-GFP cRNA was in vitro transcribed by the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T3 kit (Life Technologies, AM1348M). The primers used for Ccnb1 coding region amplification were: forward, 5′-CCGCTCGAGCGGATGGCGCTCAGGGTCACT-3′; and reverse, 5′-CGCGGATCCGCGTGCCTTTGTCACGGCCTT -3′.

The cRNAs of Ccnb1-GFP were purified by RNeazy Micro Kit (Qiagen, 74004). Purified cRNA (~200 ng/µl) were microinjected into GV stage oocytes. The injected oocytes were treated with 20 µM BLM for 1 h to induce DNA DSBs or blocked with milrinone for 1 h as control. These oocytes were released to fresh M2 medium for 1 h or 7 h and used for live cell observation as described below.

Time-lapse live cell observation of in vitro maturation of oocytes

The ZEISS live cell imaging system was used for live cell observation. To observe the GVBD of oocytes, we first cultured the GV oocytes in an incubator for 1 h and then placed them in the live cell incubator on the microscope stage. To observe SAC activity and PBE, we cultured the GV oocytes in an incubator for 7 h and then proceeded with live cell imaging. The culture environment was the same as that in a conventional incubator: 5% CO2, 37°C and saturated humidity. The sum of fluorescence signals was calculated using the live cell imaging system software.

Parthenogenesis of DSB oocytes

For parthenogenesis, in vitro matured MII oocytes were activated with 10 µM calcium ionophore A23187 for 5 min and cultured in KSOM with 10 µg/ml CHX for 6–8 h. The fertilized zygotes were used for immunofluorescence labeling or subsequent culture.

Statistics analysis

Chi square test was used to analyze the significance of the differences of GVBD rates and PBE rates between DSB oocytes and normal oocytes. Fisher exact test was used to test whether the PBE rates of GVBD oocytes were different between DSB oocytes and normal oocytes. p value < 0.01 was considered as significant difference, 0.01 ≤ p-value < 0.05 was considered as difference, and 0.05 ≤ p value was considered as no significant difference.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shi-Wen Li, Hua Qin and Li-Juan Wang for their help with the manipulations of live cell imaging and confocal laser microscopy. We also thank the other members in Dr Sun’s lab for their kind discussions about the experiments. This study was supported by the Major Basic Research Program (2012CB944404, 2011CB944501) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (30930065) to Q.Y.S.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- DSB

double-strand breaks

- GV

germinal vesicle

- GVBD

germinal vesicle breakdown

- PBE

first polar body extrusion

- MI

metaphase of the first meiosis

- MII

metaphase of the second meiosis

- BLM

bleomycin

- LMD

laser micro-beam dissection

- SAC

spindle assembly checkpoint

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/24311

References

- 1.De Bont R, van Larebeke N. Endogenous DNA damage in humans: a review of quantitative data. Mutagenesis. 2004;19:169–85. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soleimani R, Heytens E, Darzynkiewicz Z, Oktay K. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced human ovarian aging: double strand DNA breaks and microvascular compromise. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:782–93. doi: 10.18632/aging.100363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dasika GK, Lin SC, Zhao S, Sung P, Tomkinson A, Lee EY. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoints and DNA strand break repair in development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18:7883–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roig I, Liebe B, Egozcue J, Cabero L, Garcia M, Scherthan H. Female-specific features of recombinational double-stranded DNA repair in relation to synapsis and telomere dynamics in human oocytes. Chromosoma. 2004;113:22–33. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grey C, Baudat F, de Massy B. Genome-wide control of the distribution of meiotic recombination. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng EY, Hunt PA, Naluai-Cecchini TA, Fligner CL, Fujimoto VY, Pasternack TL, et al. Meiotic recombination in human oocytes. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler-Birling C, Helmrich A, Tora L, Torres-Padilla ME. Distribution of p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) and phosphorylated H2A.X during mouse preimplantation development in the absence of DNA damage. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:1003–11. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082707cz. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derijck A, van der Heijden G, Giele M, Philippens M, de Boer P. DNA double-strand break repair in parental chromatin of mouse zygotes, the first cell cycle as an origin of de novo mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1922–37. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandita TK, Richardson C. Chromatin remodeling finds its place in the DNA double-strand break response. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1363–77. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gent DC, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R. Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:196–206. doi: 10.1038/35056049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohgaki T, Bohgaki M, Hakem R. DNA double-strand break signaling and human disorders. Genome Integr. 2010;1:15. doi: 10.1186/2041-9414-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavin MF, Delia D, Chessa L. ATM and the DNA damage response. Workshop on ataxia-telangiectasia and related syndromes. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:154–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiloh Y. The ATM-mediated DNA-damage response: taking shape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:402–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speed RM. Meiosis in the foetal mouse ovary. I. An analysis at the light microscope level using surface-spreading. Chromosoma. 1982;85:427–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00330366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speed RM, Chandley AC. Meiosis in the foetal mouse ovary. II. Oocyte development and age-related aneuploidy. Does a production line exist? Chromosoma. 1983;88:184–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00285618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marangos P, Carroll J. Oocytes progress beyond prophase in the presence of DNA damage. Curr Biol. 2012;22:989–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuen WS, Merriman JA, O’Bryan MK, Jones KT. DNA double strand breaks but not interstrand crosslinks prevent progress through meiosis in fully grown mouse oocytes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pesin JA, Orr-Weaver TL. Regulation of APC/C activators in mitosis and meiosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:475–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.041408.115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt JE, Jones KT. Control of homologous chromosome division in the mammalian oocyte. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15:139–47. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botchway SW, Reynolds P, Parker AW, O’Neill P. Use of near infrared femtosecond lasers as sub-micron radiation microbeam for cell DNA damage and repair studies. Mutat Res. 2010;704:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Chao SB, Wang ZB, Qi ST, Zhu XL, Yang SW, et al. Checkpoint kinase 1 is essential for meiotic cell cycle regulation in mouse oocytes. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:1948–55. doi: 10.4161/cc.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodarzi AA, Jeggo P, Lobrich M. The influence of heterochromatin on DNA double strand break repair: Getting the strong, silent type to relax. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:1273–82. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferraretti AP, Goossens V, de Mouzon J, Bhattacharya S, Castilla JA, Korsak V, et al. European IVF-monitoring (EIM) Consortium for European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2008: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:2571–84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sebestova J, Danylevska A, Novakova L, Kubelka M, Anger M. Lack of response to unaligned chromosomes in mammalian female gametes. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3011–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.21398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun SC, Kim NH. Spindle assembly checkpoint and its regulators in meiosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:60–72. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei L, Liang XW, Zhang QH, Li M, Yuan J, Li S, et al. BubR1 is a spindle assembly checkpoint protein regulating meiotic cell cycle progression of mouse oocyte. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1112–21. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.6.10957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Homer HA. Mad2 and spindle assembly checkpoint function during meiosis I in mammalian oocytes. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:873–86. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M, Li S, Yuan J, Wang ZB, Sun SC, Schatten H, et al. Bub3 is a spindle assembly checkpoint protein regulating chromosome segregation during mouse oocyte meiosis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herbert M, Levasseur M, Homer H, Yallop K, Murdoch A, McDougall A. Homologue disjunction in mouse oocytes requires proteolysis of securin and cyclin B1. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:1023–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gui L, Homer H. Spindle assembly checkpoint signalling is uncoupled from chromosomal position in mouse oocytes. Development. 2012;139:1941–6. doi: 10.1242/dev.078352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lane SI, Yun Y, Jones KT. Timing of anaphase-promoting complex activation in mouse oocytes is predicted by microtubule-kinetochore attachment but not by bivalent alignment or tension. Development. 2012;139:1947–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.077040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Souza CP, Osmani SA. A new level of spindle assembly checkpoint inactivation that functions without mitotic spindles. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3805–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.22.18187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roos WP, Kaina B. DNA damage-induced cell death by apoptosis. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:440–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]