Abstract

Effective medical treatment for HIV/AIDS requires patients’ optimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). In resource-constrained settings, lack of adequate standardized counseling for patients on ART remains a significant barrier to adherence. Masivukeni (“Lets Wake Up” in Xhosa) is an innovative multimedia-based intervention designed to help people living with HIV in resource-limited settings achieve and maintain high levels of ART adherence. Adapted from a couples-based intervention tested in the United States (US), Masivukeni was developed through community-based participatory research with US and South African partners and informed by Ewart’s Social Action Theory. Innovative computer-based multimedia strategies were used to translate a labor- and training-intensive intervention into one that could be readily and widely used by lay counselors with relatively little training with low-literacy patients. In this paper, we describe the foundations of this new intervention, the process of its development, and the evidence of its high acceptability and feasibility.

Keywords: HIV, ART adherence, intervention, multimedia, task-shifting

INTRODUCTION

The advent of large-scale ART distribution programs in low- and middle-income countries presents both extraordinary opportunities and significant challenges. In countries such as South Africa, effective HIV treatment can provide millions of people with longer, healthier lives and stem the epidemic in societies beset with severe social, economic, and health problems. However, extensive research in high-income countries has demonstrated that ART availability alone is not sufficient to achieve long-term health benefits [1–3]: patients also must adhere carefully to often-complex medication regimens.

High ART adherence is strongly related to better long-term virologic, immunologic, and clinical outcomes [1–3]. Inadequate viral suppression due to poor adherence can lead to development of drug-resistant HIV, with serious consequences both for the individual – e.g., clinical and immunological decline [4] and future medication resistance [5,6] – and for the public health [7,8] – e.g., further HIV transmission of possibly drug-resistant viral strains [9–11]. In addition, poor adherence is associated with more hospitalizations and higher direct health care costs [12], thus posing a significant burden on health care systems. Yet, in spite of its critical role, few interventions have demonstrated efficacy to promote optimal and long-term adherence, especially in resource-poor settings [13–15].

South Africa has the largest population of people living with HIV (PLWH) in the world, with 5.6 million infected individuals and an estimated 390,000 new infections per year [16]. Since 2004, extensive efforts have provided ART programs for millions of PLWH. In addition, treatment guidelines are moving towards earlier initiation of ART– i.e., at higher CD4+ cell levels – especially for particularly vulnerable groups such as pregnant women and TB patients [17]. Yet, this treatment scale-up faces significant challenges. For instance, with only eight physicians per 10,000 people, the number of HIV-infected patients in South Africa far exceeds the capacity of available HIV health care providers [18]. Moreover, although initial data suggested adherence levels in African populations that were much higher than in the United States (US) and Europe [19], more recent studies indicate that over time adherence rates in Africa are variable and often poor, similar to other countries that have had longstanding access to ART [20,21].

In spite of a large literature demonstrating non-adherence to long-term treatment across health conditions such as asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, and HIV [22], few definitive approaches exist for improving adherence. In a meta-analytic review of 18 randomized controlled trials of ART adherence interventions, only eight demonstrated significant intervention effects, with low to moderate effects at best [15]. The most effective interventions used cognitive-behavioral models and shared a core set of psycho-educational components: 1) educating about HIV and adherence; 2) teaching self-monitoring skills; 3) identifying adherence barriers; 4) improving problem-solving skills; and 5) reframing treatment beliefs and attitudes. In addition, theoretical models have begun to consider contextual influences on adherence. For example, Social Action Theory (SAT) [23] adds a focus on social relationships, health care systems, and environmental stressors that influence self-regulation and health behaviors [24].

Social interactional factors are particularly important determinants of adherence behaviors. Amount of and satisfaction with the support a person receives as well as the extent of his/her social network are related to health status and clinical outcomes in a range of chronic illnesses [25]. In HIV, family and social support are associated with better psychological adjustment, adherence, and slower progression to AIDS [26]. Social network members may enhance adherence by endorsing positive beliefs about ART and motivation for treatment and by reminding, prompting, and supporting the patient [27]. However, the contribution of social support to adherence outcomes varies with the nature of the relationship [28], and it is important to optimize effective social support and prevent counter-productive or detrimental interactions.

Standard of Care for ART Adherence Counseling in South Africa

In response to the shortage of health care workers in the face of expanding ART programs [29–32], many African nations are shifting some health service responsibilities from physicians and nurses to less specialized personnel [33,34]. In the Western Cape of South Africa, adherence counseling has been shifted to lay counselors, who are usually trained and certified by the Western Cape AIDS Training and Information Counseling Centre (ATICC). Although they typically receive approximately one month of such training, once certified, lay counselors are often left on their own to identify and address adherence problems with the patient.

Current treatment guidelines [17] require lay counselors to provide patients with three or four “pre-ART preparatory” adherence counseling sessions prior to ART initiation. During these sessions, the lay counselor is supposed to discuss HIV, explain the benefits of good adherence and consequences of poor adherence, ensure that the patient understands his/her treatment regimen, provide advice for obtaining adherence support, and discuss potential barriers to adherence. Adherence counseling sessions are expected to last from 30 to 50 minutes and are meant to include a treatment support partner; but content, counseling style, inclusion of support partners, and session length are not standardized; nor are there systematic procedures for quality assurance or supervision of counselors. Thus, while adherence counseling by lay staff has become an accepted strategy to manage staggering numbers of HIV-infected patients, variability in content and quality of counseling has prompted urgent calls for an effective adherence intervention that can be delivered with fidelity by trained lay staff to establish and maintain optimal adherence.

South Africa’s treatment guidelines also state that to qualify for ART, the patient must identify a support partner who knows the patient’s HIV status and attends at least one counseling session. In reality, however, support partner participation varies, and anecdotal reports indicate that, in order to qualify for treatment, patients may quickly nominate a partner who is not a significant social network member for that one session only. Thus, while the policy is sound, patients would benefit from a better process for identifying appropriate treatment support partners, as well as for engaging partners in the counseling and educating them on the importance of adherence. A recent study from South Africa suggested that addressing treatment-supporter characteristics and relationship factors may influence patients’ ART adherence [35]. However, few such interventions have been developed and evaluated.

Use of Multimedia for Health Promotion

Multimedia interventions are used increasingly in health/mental health fields to promote engagement, learning, standardization, and delivery [36]. Interactive video enhances transfer of learning [37] and has produced health improvements in asthma [38,39], diabetes [40], smoking [41,42], and alcohol use [43]. Compared to oral or written interventions, multimedia-based programs have better short- and long-term efficacy for health behavior change [44]. Implementation of multimedia in HIV/STI prevention has demonstrated good feasibility across populations [45–47]. Multimedia modalities appear to be liked by users and to be more time-efficient and cost-effective than traditional approaches [48,49]. Finally, given the high rates of illiteracy in South Africa (ranging from 27% in urban areas to 50% in rural areas [50]), the use of videos and pictures to teach patients memorable lessons about HIV treatment and adherence may be critical [51].

Responding to the need for an effective adherence intervention that conforms to South African health policy for adherence counseling and can be delivered with fidelity by trained lay staff, US and South African investigators and clinicians developed “Masivukeni” (Lets Wake Up), a multimedia intervention for patients and their treatment support partners. Masivukeni was adapted from the SMART (Sharing Medical Adherence Responsibilities Together) Couples [52,53] intervention.

SMART Couples was the first couples-based ART adherence intervention with demonstrated efficacy that took into consideration SAT and the importance of social support in maintaining ART adherence. In a randomized controlled trial, SMART Couples improved medication adherence among ethnically diverse, relatively poor patients in an inner-city (New York City) clinic setting by including their uninfected primary partners in adherence counseling and support sessions [53]. Among the eight proven efficacious ART adherence interventions included in the CDC Compendium of Evidenced-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions (see: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/resources/factsheets/smart-couples.htm), SMART Couples is the only one with a specific focus on selecting and engaging treatment support partners in adherence care. Since South Africa has a policy of involving treatment support partners, often referred to as “treatment buddies” in the initiation of ART for eligible patients, SMART Couples was chosen for adaptation to the South African context.

In this paper, we describe the intervention framework; the process of its development for the local context; and a pilot study to determine the feasibility of delivery in a busy clinical setting and acceptability among clinic staff, lay counselors, and patients and their support partners. It is our belief that new ART adherence programs for countries with limited-resource health care systems are more likely to be sustainable if they are relatively inexpensive, can be implemented with minimal training and supervision, and utilize the local procedures and policies for adherence counseling already in place (e.g., use of the lay counselor and treatment buddy system in South Africa).

METHOD

Phase I: Intervention Adaptation Procedures

We adapted Masivukeni from the SMART (Sharing Medical Adherence Responsibilities Together) Couples intervention [52,53]using international collaboration and community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods. Originally developed in the US, SMART Couples comprises four sessions guided by SAT [23] and involves psycho-education and structured discussions as well as problem-solving and couple-communication exercises. Key components target a) importance of adherence in avoiding development of resistant virus and maintaining health; b) identification of non-adherence patterns; c) partner support, communication and problem-solving strategies to overcome adherence barriers; and d) partner’s confidence for achieving and maintaining improved adherence.

Given cultural differences between the US and South Africa – including language, literacy, and concepts of illness and treatment – local community participation was actively sought to guide the adaptation of SMART Couples for Masivukeni. The CBPR adaptation process involved four groups: 1) behavioral and social scientists from the US and South Africa, 2) clinical providers from the US and South Africa, 3) HIV-positive clinic patients in South Africa, and 4) US academic faculty with expertise in multimedia-based curricula development. Initial meetings defined local contextual issues, such as the need for intervention materials that did not rely on the written word, culturally tailored metaphors to communicate treatment and adherence information, and an easy-to-use computer user interface.

Through iterative research, the US and South African teams identified critical themes related to adherence in the South African context, including key barriers (e.g., social stigma, lack of treatment-related knowledge, alcohol use and psychiatric distress) and key facilitators (primarily social support and problem-solving). The teams also examined current South African Department of Health (SADOH) guidelines for ART adherence counseling. This intensive process identified key components of the SMART Couples intervention that needed to be retained, excluded or modified for Masivukeni.

Team members from the US and South Africa met weekly to discuss intervention curricula, imagery and multimedia content. When new ideas for metaphors, images, or ways to explain complex information (e.g., the Island Activity) emerged, the South African team would bring the ideas to the clinic to elicit feedback from counselors, patient advocates, and clinic staff. In this way, the content and curriculum was constantly informed by the local context and community. The same iterative process was used to develop the computer user interface and inform the interaction design to ensure easy navigation within and between intervention sessions for persons with low computer literacy. The adaptation process led to a six-session ART adherence intervention guided by SAT and housed on a laptop computer with multimedia activities to engage and teach patients (see Results for a full intervention description).

Phase II: Acceptability and Feasibility Study Procedures

Setting

We conducted a pilot acceptability study of Masivukeni in a healthcare clinic serving a high HIV-prevalence township on the outskirts of Cape Town. The clinic was operated by the City of Cape Town Department of Health and served the general medical needs of the township that surrounded it. The township is home to approximately 15,000 residents, many of whom work in the fishing industry. The clinic where the current study was conducted is the sole health/medical clinic for this community and reflects the national shortage of healthcare workers – in South Africa there are approximately 1,300 individuals for each physician (compared to 390 individuals for each physician in the US)[18]. The clinic was regularly staffed with one physician, one pharmacist, and two to three nurses, as well as one to two adherence counselors and several patient advocates.

Facilitator recruitment and training

To implement the intervention, we hired two lay adherence counselors who had undergone standard of care training by ATICC and then were trained by our study team on the Masivukeni curriculum, program navigation, and multimedia activities, including the mental health and alcohol use screening (see below) and working with computers and saving data.

Sample recruitment

We recruited 33 patients who had been on ART for at least six months and were identified as non-adherent by pharmacy records and/or clinician assessment. Patients were referred to the study coordinator who described the study and went through the consent process. Once recruited and consented, patients completed Session 1 or were scheduled to come back to complete Session 1 at a later date. Sessions were scheduled at approximately one-week intervals, and patients were able to coordinate intervention sessions with clinic appointments. If patients did not return for scheduled sessions, study counselors called and/or texted patients to reschedule. Participants received compensation for transportation at each session visit (the equivalent of approximately $5).

Process evaluation

Patients

Immediately after each session, the patient participant was interviewed by a study staff member who was not the intervention provider. Participants were asked to rate how helpful and useful each activity was and to provide their general feedback on each activity, as well as how they felt about the session overall. After completing all six sessions, patients were interviewed again about their overall experience in the intervention (e.g., what they liked the best and least about it, feelings about the number of sessions, and what they thought of the multimedia). Finally, at the end of the pilot study, we held a focus group with eight patients and their support partners (treatment buddies) who had gone through the intervention to assess their overall experience of the intervention, what they liked and didn’t like about it, and what effect they think it had on their health behaviors. The focus group was facilitated by two study investigators who were not involved in administering the intervention sessions.

Counselors

After the completion of each session, the counselor who administered the session completed a counselor rating form rating each activity was in terms of ease of program use and helpfulness/usefulness for that patient (e.g., How useful was the Island Activity, and What are your overall feelings about the session?). At the end of the pilot study, research investigators met formally with the counselors to obtain overall feedback on their experience with the intervention.

Providers

After completing the pilot study, six clinic providers (i.e., 1 physician, 3 nurses, 1 pharmacist, 3 patient advocates) were interviewed to assess their perception of the intervention based on their observations and things they heard from patients and other clinic staff At least two investigators conducted each interview.

Research staff organized process evaluations from patients (interview data) and counselors (handwritten responses on counselor rating form) by session and entered responses into spreadsheet for review and analysis. Responses were reviewed and collated by session by study co-investigators. Clinic provider interviews and participant focus group data consisted of hand-written notes taken by the interviewers/facilitator. All notes were compiled and organized by research staff. Study investigators then independently reviewed all feedback data. Meeting as a group, they reached consensus on the salient findings of the patient interviews and focus groups, the counselor ratings, and the clinic provider interviews.

RESULTS

Phase I: Results of Intervention Adaptation

Through the iterative process of CBPR, the SMART Couples curriculum was adapted to be more relevant to the South African context. Collaboration with stakeholders, communities, and service providers having first-hand knowledge of the local cultural and psychosocial context was critical to adapting SMART Couples to this new setting. We found that our partnership fostered local ownership and commitment to the intervention, which is in line with similar research demonstrating that this process can lead to an intervention being more accessible, acceptable, and likely to be translated into practice [54,55].

The curriculum comprises six sessions; each includes innovative interactive multimedia components to support self-regulation (e.g., knowledge and problem-solving skills to increase capabilities and motivation), social interactions (e.g., social support), and contextual barriers to adherence (e.g., relationship to healthcare system)identified by the patient. To keep each session length to 45 minutes or less, the content was divided across six sessions, with some repetition of activities – such as problem-solving barriers to optimal adherence – across several sessions. While Masivukeni was designed to meet the needs of all ART counseling phases (i.e., pre-ART initiation and on-going adherence counseling) and to conform to the standard care ART adherence counseling framework, based on local needs at the time of this study, we piloted the intervention with people who demonstrated adherence problems after having been on ART for at least six months (see sample description below).

Session 1 (Rapport, Assessment of Mental Health and Substance Use, and Social Support)

In the first session, the counselor meets with the patient alone to (1) set ground rules for session attendance and participation, (2) establish rapport, (3) screen for mental health and alcohol use problems (for referral), (3) increase motivation for and commitment to adherence, (4) discuss the patient’s social support network, and (5) help the patient choose a treatment support partner to participate in subsequent sessions.

Alcohol use and other mental health problems are common barriers to optimal adherence in South Africa. While lay adherence counselors are supposed to assess for these problems during counseling, they often lack sufficient training, and assessments are often not done effectively or at all. Therefore, two widely used and validated mental-health and alcohol-use screening tools, the Kessler-10 and AUDIT [54,55], were programmed into Session 1. For both measures, the program provides automatic scoring and referral “scripts” that enable counselors to conduct standardized assessments and make appropriate referrals for evaluation and treatment.

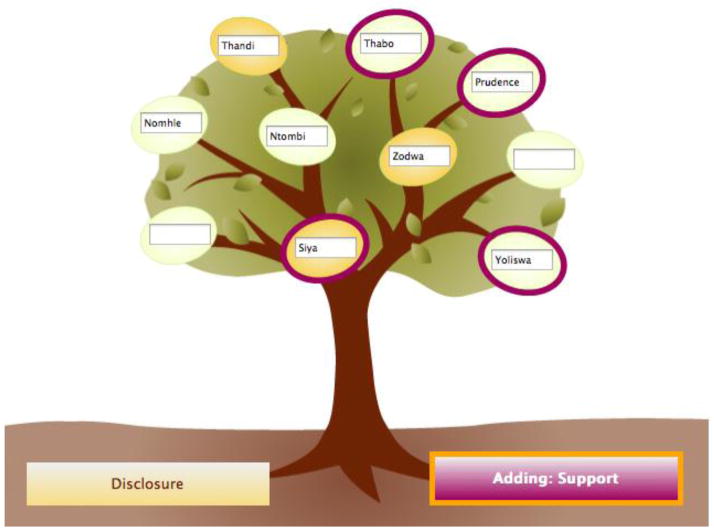

Social support is a key theoretical component addressed in Session 1. An interactive component introduced in this session is the social support network tree (Figure 1), which represents an individual’s social support network and is based on a culturally relevant metaphor used by South African psychologists with patients. In Masivukeni, patients label the “fruits” of the tree with names of people in their social support networks and then identify those who provide practical support (e.g., transportation or child care) and those to whom patients have already disclosed their HIV status. Using the on-screen visual representation of a patient’s social support network, the counselor guides the patient in selecting a suitable treatment support buddy for subsequent intervention sessions. The counselor reinforces the potential benefits of having a support partner in the intervention – a person who can learn about HIV and its treatment and provide the patient with ongoing motivation and emotional and practical support.

Figure 1.

Support Tree Activity

Note: Orange colored tree fruits indicate disclosure status (orange = disclosed to). The purple ring around the fruit indicates that the person is a source of practical support.

The interactive and personalized tree activity provides an engaging way for the counselor and patient to discuss the importance of social networks in the remaining five sessions. The tree is saved in the program, and the counselor and patient can access it at any time. The theme of social support is an overarching one in the Masivukeni intervention, and patients are encouraged to continually review and modify the tree in subsequent sessions.

Session 2 (Knowledge)

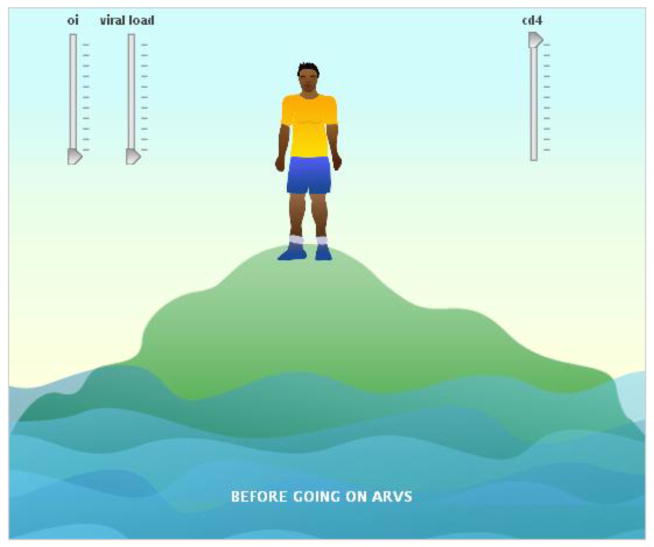

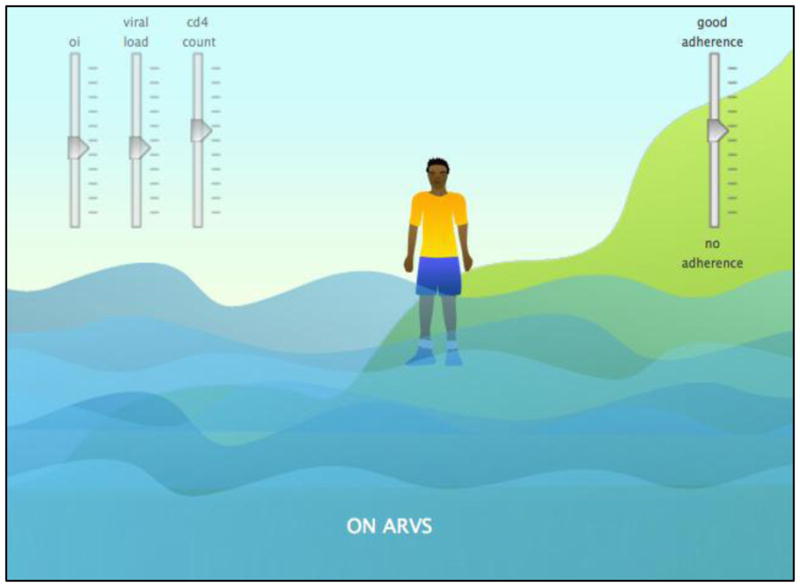

In Session 2, the patient’s social support partner joins the program. Session objectives are to (1) set ground rules for session attendance and participation for both the patient and support partner; (2) establish rapport with the support partner; (3) increase understanding of concepts related to HIV, the patient’s treatment regimen, and adherence to ART and medical care; and (4) increase motivation and commitment for adherence. In Session 2, the counselor introduces the dyad to adherence and uses a culturally relevant, interactive computer-based visual to discuss it in the context of inter-related medical variables, i.e., viral load, CD4 cells, and opportunistic infections (Figure 2). This visual imagery is then extended to depict how medication adherence influences these clinical factors (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

HIV Knowledge (Island) Activity.

Note: Patients and partners can move the sliders up and down. As viral load goes up and cd4 count goes down, the person on the island becomes thinner and the water level rises.

Figure 3.

HIV Knowledge (Island) Activity 2

Note: Patients and partners can move the adherence slider up and down. As adherence goes up, viral load goes down, cd4 count goes up, and the person on the island becomes moves up the mountainside.

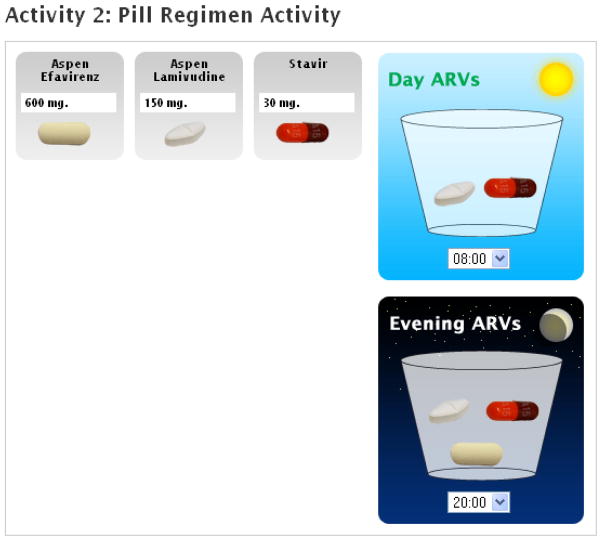

Adherence-related behaviors are clarified by reviewing the patient’s medication regimen, medical appointment schedule, and prescription plan. Through an interactive pill regimen activity (Figure 4), the counselor guides the patient through a series of computer screens in which s/he is asked to identify the pills in her/his regimen and the intended timing and dosing. The activity results in a pictorial chart that allows the patient and the treatment support partner to understand which antiretroviral medications are being taken and the dosing schedule.

Figure 4.

Pill Regimen Activity

Note: Patients and partners can move their regimen pills into the cups. If they make mistakes, the counselor will correct them.

To increase knowledge of HIV and non-adherence consequences, a video developed at Yale University, Stanford University, and the Perinatal HIV Research Unit of the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa [51] was programmed into Session 2 as a dramatic illustration of viral resistance, using snakes to represent HIV and soldiers to represent the immune system.

Session 3 (Problem-Solving)

Objectives of this session are to (1) reinforce the importance of adherence and good health care, (2) promote adherence self-efficacy, and (3) teach problem-solving skills and their application to adherence barriers. The patient and his/her support partner first learn the four basic steps of problem-solving (defining the problem, deciding on a goal, brainstorming and evaluating options for potential solutions, developing a specific action plan), watching an original video that models problem-solving skills in a scenario in which a support partner helps an HIV-positive friend work through the steps of problem-solving. A narrator pauses to highlight each step. The script for the video was developed by the South African clinical team, and the actors and narrator are native South Africans.

The patient and support partner then apply these problem-solving steps to a specific adherence barrier in the patient’s life (e.g., drinking behaviors, mistrust of the doctor, not maintaining a steady supply of medicine), drawing from a visual “menu” of potential barriers as well as other barriers the participants may identify. The resulting action plan is stored in the program, can be printed for the patient to take home, and can be revisited in subsequent sessions.

Session 4 (Secondary Transmission Prevention)

Objectives of Session 4 are to (1) practice problem-solving and (2) review modes of HIV transmission and importance of HIV transmission prevention. Participants review the previous session’s action plan and describe progress between sessions. Based on this review, the patient can create another action plan for the same barrier or work through the problem-solving steps for another barrier. The overarching goal of the problem-solving activity is that participants understand the need to work continually on barriers using a proactive and collaborative approach.

This session also includes a discussion of the modes of HIV transmission through a “Myth/Fact Game” in which the patient is provided with statements about HIV transmission and asked to identify whether each statement is true or false. This game also highlights the link between adherence and viral load in reducing transmission risk. Understanding HIV transmission promotes health behaviors by increasing knowledge and motivation and thereby maintaining individual and public health. Both the patient and support partner are encouraged to explore their understanding of transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections most common in their communities.

Session 5 (Disclosure)

Session 5 has the following objectives: (1) practice problem-solving and (2)discuss how thoughtful disclosure to others can result in increased support and help patients stay healthy. Disclosure is approached through a video developed by the same Yale researchers who created the snakes and soldiers video. The Session 5 video shows two characters currently on ART: Hope, who has disclosed to people in her household, and Joseph, who has not disclosed to anyone. The scenes depict the advantages of disclosure for Hope. For example, when she is rushing out of the house after breakfast, her brother reminds her to take her medication, which she does. In contrast, Joseph runs out of his house saying good-bye to his mother but does not take his medicine; since his mother is unaware, she does not remind him. Over time, Hope takes her medicine on a regular basis and remains healthy and active. Joseph, on the other hand, is inconsistent in taking his medicine and becomes very ill and ultimately unable to leave the house due to advanced illness. After they view the video, the counselor engages the dyad in a conversation about the pros and cons of disclosure, emphasizing the potential benefits of increasing social support for adherence.

Session 6 (Patient-Provider Communication and Review)

The objectives of Session 6 are to (1) build support and confidence to access and communicate with members of the healthcare team and see them as additional support partners; (2) review the social-support tree and other activities from previous sessions; and (3) end the program with the patient and support partner committing to helping each other and staying healthy. The emphasis on patient-provider communication reflects concerns of clinic providers that patients are often inhibited from communicating openly and effectively with them. Because lack of open communication can affect medication adherence as well as attendance at health care appointments and effective use of health care systems, our clinical collaborators (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, adherence counselors, psychologists, and patient advocates) wanted patients to view providers as part of their social networks. Thus, in this final intervention session, the social-support tree that was developed in the initial session is revisited, and participants are encouraged to think about additional people they would like to add, including clinic providers.

Multimedia Framework

Partners with expertise in multimedia-based curricula development were important in addressing literacy concerns and counselor resource issues. Masivukeni’s multimedia foundation enabled lay adherence counselors to deliver the intervention in an engaging and structured way while overcoming challenges associated with their own limited education, training, and supervision and their patients’ low literacy levels. The computer-based tool is used by counselors with patients and their partners and includes enhanced scripted text, imagery, animations, audio, and video to deliver critical information and concepts as well as to model desired behaviors.

The content was programmed in HTML and presented in a webpage format, though an internet connection is not required to administer the intervention. It provides a roadmap for each session, while also enabling the counselor to focus on the particular needs of the patient. Counselors and patients can enter responses to questions, receive feedback, and manipulate virtual objects in order to apply new concepts, explore hypothetical scenarios, practice new skills, test knowledge, and set goals for future sessions. The tool can track data entered by the facilitator or patients, generate a printed packet of information tailored to a particular patient’s sessions, and provide a means of assessing session activities and progress through the intervention. Additionally, the tool facilitates counselor administration of standardized mental health and alcohol use screeners.

Phase II: Acceptability and Feasibility Study Results

Thirty-three participant patients who had been on ART for at least six months and were identified as non-adherent by pharmacy records and/or clinician assessment were recruited; six did not return to attend any sessions. Of the 27 who initiated the intervention, 85% (n=23) completed at least four of the six sessions. Twenty-three (70%) identified a support partner to participate in the intervention, and 20 (87%) of those partners attended at least half of all sessions with the patient; one participant changed support partners at the third session. Among participant patients, 74% were women. The mean age was 37.19 (SD = 8.39); 96% spoke Xhosa at home; 100% had less than a high school education; 82% were unemployed; and 56% had gone without food at least once in the past month. Among support partners, 80% were women. The mean age was 33.96 (SD = 9.43); 100% spoke Xhosa at home; 80% had less than a high school education; 60% were unemployed; and 45% had gone without food at least once in the past month. These demographic characteristics are representative of the communities in South Africa with high HIV prevalence. Thirty-five percent of the support partners self-reported as friends of the patients; 35% reported being a family member (sibling or cousin); 18% reported being a boyfriend; and 12% reported being a spouse.

Because our study counselors were well integrated into clinic operations and had regular contact with the clinic providers and attended weekly clinic team meetings, they were able to closely track participants. Among the six participant patients who did not attend any sessions, two were employed just after enrolling in the study and could not take any time off to attend counseling sessions, although they continued to receive their ART prescriptions at the clinic. Three participant patients never returned to the clinic during the study and were unable to be contacted. The sixth participant provided incorrect contact information, and, in clinic team meetings, the counselors learned that he had a known alcohol problem. While correct contact information was obtained during a home visit, this patient did not return to counseling sessions after repeated scheduling, even though he continued in sporadic care at this clinic.

Feedback from counselors

The two adherence counselors said that the framework and guided activities increased their ability to do their job, ensured that they would not leave out important information when counseling patients (including knowledge of possible and relevant mental health and alcohol use issues), and empowered them to address barriers and facilitators of adherence. For example, one counselor reported, “It guides me through the sessions and helps me cover all the material. This helps me pay closer attention to the patient and buddy and engage with them more easily.” Counselors felt that the videos and activities helped patients engage more with them and with the content of the intervention and that the framework of the intervention enabled them to both support and challenge patients more effectively and get patients to think more thoroughly about their health and treatment.

Counselors’ feedback also identified some problems that can be rectified. For instance, counselors indicated that because the videos were in English, they had to regularly pause the videos and provide live translations to help participants understand, which slowed the session and interrupted the flow of the videos. One counselor reported having to repeatedly help the other counselor with the laptop e.g., with logging in and with navigating to previously viewed screens to review material with patients. Both counselors felt that some sessions, particularly sessions 5 and 6, were too long and too repetitive. They thought 6 sessions might be too many, as it was hard for patients to attend clinic so frequently.

Feedback from patients

In general, most of the patients found the Masivukeni sessions engaging; they also reported a better understanding of difficult concepts related to treatment and health including how ART works, viral resistance, and the dangers of alcohol and smoking. They felt better able to identify and use problem-solving strategies and social support to establish and maintain good adherence. Executed action plans included (1) spending less time with “drinking friends” on the weekends to overcome the problem of alcohol use interfering with medication adherence, (2) disclosing ones HIV status to more people to overcome the problem of not having enough treatment support, and (3) setting a cell phone alarm or using television programs to remember when to take medications. Feedback on individual sessions was as follows:

Session 1 (Rapport, Assessment of Mental Health and Substance Use, and Social Support)

Most patients found the overall content of Session 1 engaging and useful. The Support Tree Activity was found to be particularly useful– “I have learnt a lot of things, like having a buddy is good,” (44-year-old female patient).

Session 2 (Knowledge)

Session 2 content was also considered useful by most patients. Having the opportunity to review and learn the medical terms associated with HIV and ART was deemed particularly helpful. Patients reported, “Now we know some medical terms…. we have learnt a lot, like ARV names,” (from a 37 year-old-female), and “The session was very helpful. Now I can educate others,” (from a 40-year-old male).

Session 3 (Problem-Solving)

Patients found the Island Activity in Session 3 especially engaging and useful (e.g., “[It] was very helpful as it shows what can go wrong if a person is defaulting,” from a 44-year-old female). The Problem-Solving Activity was also viewed mostly positively and even “…fun and practical,” (from a 31-year-old male).

Session 4 (Secondary Transmission Prevention)

Feedback from Session 4 indicated that most patients found the session informative and encouraging. For example, patients said of Session 4, “They are teaching and encouraging you to move on with life,” (from a 44-year-old female), and, “It encourages you to do good” (from a 31-year-old female).

Session 5 (Disclosure)

Feedback from Session 5 was similar to the feedback from Session 4. Most patients found Session 5 educational and inspiring. For example, a 31-year-old male patient said, “The session gave hope and also having a buddy is good, so life can go on.” In particular, the video activity about disclosure (Joseph and Hope) was viewed very positively by most patients, “[the] Joseph and Hope video was wonderful that it encourages that you must disclose to the people who care for you,” (from a 20-year-old female).

Session 6 (Patient-Provider Communication and Review)

Feedback for the final session of Masivukeni was mostly positive. Many patients were reflective of the whole program, saying the “Masivukeni project has played a big role in our lives, so we are very happy about the project,” (from a 44-year-old female), “It was very fruitful and educating, so I have more years to live. It has taught me a lot of things,”(from a 37-year-old female), and, “It shows that all the sessions are very good and has encouraged me to take the prescription regularly,” (from a 43-year-old female).

Feedback from exit interviews conducted after patients had finished the intervention indicated that patients liked the Snakes and Soldiers video, Support Tree Activity, and Island Activity the most. Most patients responded that they found the computers to be very useful and engaging, were able to better understand the importance of adherence and how to overcome barriers to it, and liked having more contact with the counselors. Several patients remarked that they wished that they had learned what they did in Masivukeni when they initiated ART, as they felt they never understood ART and adherence as clearly as they had from Masivukeni. A few patients said that there were too few sessions, and others said that the incentives may have contributed in part to their full participation.

While most of the patient feedback was positive, several patients thought that the sessions were too long and that there were too many sessions. They said that getting to the clinic so frequently was difficult and costly and could interfere with employment or childcare obligations. A few patients also expressed reservations about using the computer due to never having used one; hence, they were hesitant to use the mouse during some of the interactive activities.

Feedback from Focus Groups

The feedback from patients and support partners during the focus group reinforced findings from all other process evaluations. Both constituencies spoke very highly of the intervention, with specific praise for the videos and interactive images. The support partners spontaneously spoke of the personal benefits they got from the intervention– learning about HIV, how the virus works in the body, and how treatment works to fight the disease and improve immune function and health. For some, this was a personal benefit in coping with their own HIV illness. Infected support partners felt that learning about HIV helped them provide support for other infected individuals in their community. All support partners talked about their satisfaction with being able to help the partner with whom they participated in the intervention. Finally, just as in the feedback we got from individual patients, the patients and support partners talked in the focus group about the challenges presented by life circumstances to coming to all of the sessions.

Feedback from clinic providers

Clinic physicians, nurses, and the pharmacist reported positive changes in patients, particularly in consistent clinic attendance. They reported that Masivukeni counselors spent more time with patients than did the counselors who delivered standard adherence counseling in the clinic. Whereas mean length of the Masivukeni sessions was 42 minutes (range=32–54), providers reported that standard care counselors often spend as little as 5–10 minutes with patients. The providers found the metaphors used in Masivukeni to be particularly salient to their patient population and wanted providers throughout the clinic to become familiar with Masivukeni imagery and metaphors so they could be reinforced with patients. They were also very eager to train their adherence counselors in Masivukeni at the study’s conclusion.

Overall, clinic providers thought that the intervention had excellent potential to be integrated into current clinic operations. They liked that the intervention was housed on a laptop and included interactive features, especially the videos. The nurse clinic director reported that she would like to see all ART patients receive Masivukeni – particularly at the time of ART initiation. She also indicated that it would be useful to have computerized features that could generate reports, such as how long counselors spent with patients and how many patients have been seen and are currently being seen by counselors. Negative concerns of the clinic staff were mostly focused on the computer technology, such as the need for computer literacy skills training for all adherence counselors, and the need for computer maintenance support. They also expressed some concern over the high number of sessions.

DISCUSSION

Masivukeni is a multimedia adherence intervention that is based on the theoretical and conceptual constructs of the effective SMART Couples adherence intervention. Key concepts of social support, media-based learning, and CBPR were used to develop an intervention that would be highly relevant, acceptable, and potentially sustainable in low-resource clinical settings as well as consonant with existing local health care policy. Masivukeni offers a systematized, visual, and collaborative approach that can be standardized for delivery by lay counselors to help patients choose a support partner and optimize adherence to ART. At the same time, Masivukeni activities are interactive and can be customized for individual patient-support partner dyads.

The process evaluation of this intervention indicated high acceptance of Masivukeni and feasibility of its use in a South African clinic that is representative of HIV-treatment settings in the country. Regarding feasibility, clinic administrators believed that Masivukeni could be integrated into current ART counseling procedures without much disruption. Interestingly, after this study was completed, the clinic nurses reported that Masivukeni was used at the clinic by all adherence counselors until the laptop we donated had a malfunction, at which point the clinic did not have the resources to fix. Nonetheless, the nurses reported that the counselors incorporated many of the Masivukeni activities into their counseling sessions after the laptop broke, and that the intervention framework was integrated into pre-ART initiation counseling sessions.

Both counselors and patients reported high acceptability of Masivukeni. The media-based intervention sessions were found to be engaging for participants. The emphasis on social support networks, inclusion of treatment support partners, and collaborative approaches to problem-solving was useful in helping patients address adherence barriers.

A potential challenge for widespread application of Masivukeni in resource-constrained settings is its use of computer technology and the associated costs. With this in mind, the intervention was designed to be feasible in the context of low computer literacy among lay counselors with minimal software installations or configurations, and, overall, the intervention design interface was found to be user-friendly and intuitive. In addition, although the intervention was designed to function inside a free open-source Internet browser, it does not require Internet connectivity during sessions. This “offline” capability is important since reliable internet service is not available in many clinics in South Africa.

In summary, Masivukeni is a promising intervention and delivery tool that can enhance the ability of ART adherence lay counselors to deliver standardized adherence education and support. The standardized and visually engaging tool helps counselors explain how HIV works, how medications help control the virus and lead to better health, and the importance of high medication and HIV healthcare adherence. It facilitates a review of patients’ medication regimens and pharmacy refill schedules and enables counselors to correct patients’ misunderstandings about their treatment. The emphasis on treatment support partners and problem-solving maximizes the potential of the intervention to improve patients’ ability to overcome barriers to adherence.

The computerized intervention delivery format can be used to monitor patient progress and personal factors (e.g., treatment regimen, pharmacy refill schedule, social support network, adherence barriers, etc.). Given that mental health and substance use are often barriers to adherence for many people, it also incorporates mental health- and alcohol use-problem screening assessments to facilitate immediate referrals that can be adapted for use in different clinical care settings and cultures. Finally, the tool can be used to monitor delivery of counseling sessions – i.e., which content was delivered and on which dates, the length of time spent on specific activities, and total time spent in the counseling session. Based on the results of this pilot study, the intervention is undergoing additional adaptations in preparation for a randomized controlled trial to establish its impact on adherence to HIV treatment and care in South Africa.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34-MH082654; PI: R. H. Remien, Ph.D.). Drs. Remien, Mellins, Robbins, and Warne are also supported by the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies (P30-MH43520; PI: R. H. Remien, Ph.D.). The authors would like to thank the patients and staff at the Hout Bay Clinic for their support and invaluable feedback on this study. The authors would also like to thank Victoria Mayer for her tireless efforts launching this study, and Alix Simonson for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Hogg RS, Heath K, Bangsberg D, et al. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. AIDS. 2002;16(7):1051–1058. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannheimer S, Friedland G, Matts J, Child C, Chesney M. The consistency of adherence to antiretroviral therapy predicts biologic outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(8):1115–1121. doi: 10.1086/339074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNabb J, Ross JW, Abriola K, Turley C, Nightingale CH, Nicolau DP. Adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy predicts virologic outcome at an inner-city Human Immunodeficiency Virus clinic. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(5):700–705. doi: 10.1086/322590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrigan PR, Hertogs K, Verbiest W, et al. Baseline HIV drug resistance profile predicts response to ritonavir-saquinavir protease inhibitor therapy in a community setting. AIDS. 1999;13(14):1863–1871. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hertogs K, Bloor S, Kemp SD, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of clinical HIV-1 isolates reveals extensive protease inhibitor cross-resistance: a survey of over 6000 samples. AIDS. 2000;14(9):1203–1210. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozal M. Review: Cross-resistance patterns among HIV protease inhibitors. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004;18(4):199–208. doi: 10.1089/108729104323038874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ives KJ, Jacobsen H, Galpin SA, et al. Emergence of resistant variants of HIV in vivo during monotherapy with the proteinase inhibitor saquinavir. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(6):771–779. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayers DL. Drug-Resistant HIV-1. JAMA. 1998;279(24):2000–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.24.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blower SM, Aschenbach AN, Gershengorn HB, Kahn JO. Predicting the unpredictable: Transmission of drug-resistant HIV. Nat Med. 2001;7(9):1016–1020. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blower SM, Aschenbach AN, Kahn JO. Predicting the transmission of drug-resistant HIV: comparing theory with data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(1):10–11. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant RM, Hecht FM, Warmerdam M, et al. Time trends in primary HIV-1 drug resistance among recently infected persons. JAMA. 2002;288(2):181–188. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nachega JB, Leisegang R, Bishai D, et al. Association of antiretroviral therapy adherence and health care costs. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):18–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Chang Y, Lee EJ. A systematic review comparing antiretroviral adherence descriptive and intervention studies conducted in the USA. AIDS Care. 2009;21(8):953–966. doi: 10.1080/09540120802626212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simoni J, Amico K, Smith L, Nelson K. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: Translating research findings to the real world clinic. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2010;7(1):44–51. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks G, Crepaz N. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43 (Suppl 1):S23–35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNAIDS. UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS epidemic. 2010 http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/global_report.htm.

- 17.Natioanl Department of Health. Clinical Guidelines for the Management of HIV & AIDS in Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health; Republic of South Africa: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. World health statistics 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa and North America. JAMA. 2006;296(6):679–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill CJ, Hamer DH, Simon JL, Thea DM, Sabin LL. No room for complacency about adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2005;19(12):1243–1249. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180094.04652.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unge C, Södergård B, Ekström A, et al. Comparing clinic retention between residents and nonresidents of Kibera, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(3):283–284. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b48c84. 210.1097/QAI.1090b1013e3181b1048c1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fogarty L, Roter D, Larson S, Burke J, Gillespie J, Levy R. Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: a review of published and abstract reports. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(2):93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewart CK. Social Action Theory for a public health psychology. Am Psychol. 1991;46(9):931–946. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Traube DE, Holloway IW, Smith L. Theory development for HIV behavioral health: empirical validation of behavior health models specific to HIV risk. AIDS Care. 2011:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.532532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchino B. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lesserman J, Jackson ED, Petitto JM, et al. Progression to AIDS: The effects of stress, depressive symptoms, and social support. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(3):397–406. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ironson G, Hayward HS. Do positive psychosocial factors predict disease progression in HIV-1? A review of the evidence. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):546–554. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177216c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bedelu M, Ford N, Hilderbrand K, Reuter H. Implementing antiretroviral therapy in rural communities: The Lusikisiki model of decentralized HIV/AIDS care. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Supplement 3):S464–468. doi: 10.1086/521114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samb B, Celletti F, Holloway J, Van Damme W, De Cock K, Dybul M. Rapid expansion of the health workforce in response to the HIV epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(24):2510–2514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh A, Ndubani P, Simbaya J, Dicker P, Brugha R. Task sharing in Zambia: HIV service scale-up compounds the human resource crisis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):272. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehmann U, Van Damme W, Barten F, Sanders D. Task shifting: the answer to the human resources crisis in Africa? Hum Resour Health. 2009;7(1):49. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zachariah R, Teck R, Buhendwa L, et al. Community support is associated with better antiretroviral treatment outcomes in a resource-limited rural district in Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nachega JB, Knowlton AR, Deluca A, et al. Treatment supporter to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected South African adults: A qualitative study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:S127–S133. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248349.25630.3d. 110.1097/1001.qai.0000248349.0000225630.0000248343d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosworth K, Espelage D, DuBay T, Daytner G, Karageorge K. Preliminary evaluation of a multimedia violence prevention program for adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24:268–280. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno R, Mayer RE, Spires HA, Lester JC. The case for social agency in computer-based teaching: Do students learn more deeply when they interact with animated pedagogical agents? Cognition and Instruction. 2001;19:177–213. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartholomew LK, Shegog R, Parcel GS, et al. Watch, Discover, Think, and Act: a model for patient education program development. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(2):253–268. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin DH, Leventhal JM, Sadock RT, et al. Educational intervention by computer in childhood asthma: A randomized clinical trial testing the use of a new teaching intervention in childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 1986;77:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown SJ, Lieberman DA, Gemeny BA, Fan YC, Wilson DM, Pasta DJ. Educational video game for juvenile diabetes: Results of a controlled trial. Med Inform (Lond) 1997;22:77–89. doi: 10.3109/14639239709089835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.French D. Influence smoking cessation with computer-assisted instruction. AAOHN. 1986;34:391–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tingen MS, Grimling LF, Bennet G, Gibson EM, Renew MM. A pilot study of preadolescents to evaluate a video game-based smoking prevention strategy. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 1997;9:118–124. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reis J, Riley W, Baer J. Interactive multimedia preventive alcohol education: An evaluation of effectiveness with college students. J Educ Comput Res. 2000;23:41–65. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schinke SP, Schwinn TM, Nola JD, Cole KC. Reducing the risk of alcohol use among urban youth: Three-year effects of a computer-based intervention with and without parent involvement. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:443–449. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellis JM, Grimley DM, Alexander LR. Feasibility of a tailored intervention targeting STD-related behaviors. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:378–385. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown-Peterside P, Redding CA, Ren L, Koblin BA. Acceptability of a stage-matched expert system intervention to increase condom use among women at high risk of HIV infection in New York City. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12:171–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evans AD, Edmundson-Drane EW, Harris KK. Computer-assisted instruction: An effective instructional method for HIV prevention education? J Adolesc Health. 2000;26:244–251. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knebel E. The use and fffect of computer-based training. In: Project QA, editor. Operations Research Issue Paper 1. Vol. 2. Bethesda, MD: USAID; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knebel E. A comparison of computer-based and standard training in the integrated management of childhood illness in Uganda. In: Project QA, editor. Operations Research Results. Bethesda, MD: USAID; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.South Africa Ministry for Welfare and Population Development; Welfare PDo, editor White paper for social welfare: principles, guidelines, recommendations, proposed policies and programmes for developmental social welfare in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong IY, Lawrence NV, Struthers H, McIntyre J, Friedland GH. Development and assessment of an innovative culturally sensitive educational videotape to improve adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in Soweto, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:S142–S148. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248345.02760.03. 110.1097/1001.qai.0000248345.0000202760.0000248303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dognin J, Day E, El-Bassel N, Warne P. Moving from theory to research to practice. Implementing an effective dyadic intervention to improve antiretroviral adherence for clinic patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43 (Suppl 1):S69–78. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248340.20685.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dolezal C, et al. Couple-focused support to improve HIV medication adherence: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 2005;19(8):807–814. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168975.44219.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]