Abstract

This article describes an analytical study of systematic micro-level variability in migration during conflict. The study is based on a multi-dimensional model of individual out-migration that examines the economic, social, and political consequences of conflict and how community organizations condition the experience of these consequences and systematically alter migration patterns. A unique combination of detailed data on violent events and individual behaviours during the Maoist insurrection in Nepal and multi-level event-history models were used to empirically test the model. Results indicate that community organizations dampened the effect of conflict on out-migration by providing resources that helped people to cope with the danger as well as economic, social and political consequences of conflict. This evidence suggests a systematic redistribution of population, partially contingent upon specific resources available in each community, which will likely affect the socio-demographic context of post-conflict Nepal into the future.

Keywords: Migration, Forced migration, Armed conflict, Community organizations, Nepal, Asia

Introduction

This article describes an analytical study of systematic variation in migration patterns during armed conflict. The specific focus of this article is on the role of community organizations as one factor that drives this variation in who does and does not migrate away from conflict. The conceptual model that is presented here is based on a socio-ecological perspective that highlights the social, economic, and political consequences of armed conflict in addition to physical danger. It calls for consideration of the resources that help people to cope with these consequences on their daily lives. As an example, community organizations or resources that support daily living in the community of origin can help to mitigate the consequences of armed conflict and thereby decrease the likelihood of migration. Empirical analysis of this model addresses specific hypotheses about the impact of community organizations, such as markets, health centres, and micro-credit groups, on the relationship between conflict and migration during the recent Maoist insurrection in Nepal.

This is certainly not the first study of migration during conflict. There is a strong and growing body of literature documenting increases in migration during periods of generalized violence, genocide, and human rights abuses (Stanley 1987; Schmeidl 1997; Apodaca 1998; Davenport et al. 2003; Moore and Shellman 2004; Melander and Oberg 2006). This work has been integral to tracking the flow of migrants around the world, developing early warnings of mass population movements, and improving refugee and IDP support programs. Yet, scholars still argue that the literature on forced migration is under-theorized and poorly addresses some important issues, such as the composition of migrant flows (Black 2001; Castles 2003; Bakewell 2007). In seeking to understand composition, or who migrates away from conflict and who does not, theorists suggest that we need to take account of several broad sociological principles (Richmond 1988, 1994; Van Hear 1998; Black 2001; Castles 2003; Turton 2003; Bakewell 2007). The first consideration is that there are rarely cases where migration is truly forced or truly voluntary; most situations lie somewhere in between, where people are faced with both some compulsion and some room for choice at the same time. The second consideration is that people exposed to armed conflict are active agents and their behavioural decisions are complex, requiring complex models of the migration decision.

The main contributions of this study then, are in using these principles and existing migration theory to develop and test a model that advances our understanding of the composition of migration flows during armed conflict. The socio-ecological perspective is an important tool for understanding systematic variation in how people both experience and respond to conflict. In addition to migration, this perspective and the general model are also relevant for understanding patterns of change in other demographic behaviours, such as marriage and fertility, in response to armed conflict and other periods of crisis.

The recent Maoist insurrection in Nepal was used as a case study to empirically test this model of migration decision-making during conflict. A unique combination of data, including records of violent events and a prospective panel survey of individuals and the communities within which they live, made possible the direct empirical documentation of relationships between conflict, community organizations, and migration. The individual surveys from Nepal span the entire period of conflict and provided records of individuals' migrations on a monthly basis, thereby allowing precise comparisons between violent events each month and out-migration. Community surveys provided information on access to resources, including markets, health centres, farmer's cooperatives, and mills.

Theoretical Framework

At the foundation of much of migration theory is the push-pull framework. This conceptualizes migration as a result of potential migrants comparing desirable elements of possible destinations (pull factors) with undesirable elements of their current residence (push factors). When push or pull factors increase, people will be more likely to migrate. Neo-classical economics and new economics theories of migration are loosely based on the push-pull theory and explain how economic factors at the origin and potential destinations affect migration decisions (Sjaastad 1962; Todaro 1969; Stark and Bloom 1985; Taylor 1987; Todaro and Maruszko 1987; Massey et al. 1993). In addition to strong empirical support for these theories during periods of relative peace (Massey et al. 1987; Shrestha 1989; Massey et al. 1993; Massey and Espinosa 1997; Massey et al. 1998), several studies show that economic factors have been important predictors of migration during periods of generalized violence (Schultz 1971; Stanley 1987; Jones 1989; Morrison and May 1994; Lundquist and Massey 2005; Engel and Ibanez 2007; Czaika and Kis-Katos 2009; Bohra-Mishra and Massey 2011).

Theory from forced migration studies follows similar reasoning. The dominant threat-based model explains that during armed conflict, potential migrants base their decision to migrate on perceived threats to their personal security. When the perceived threat increases beyond an acceptable level, they migrate away. In other words, danger is a push factor and thereby increases the motivation to migrate. This model has been supported by strong and consistent evidence as well (Stanley 1987; Schmeidl 1997; Apodaca 1998; Davenport et al. 2003; Moore and Shellman 2004; Melander and Oberg 2006). However, the threat-based model concentrates on physical threat as the principal, if not only, motivation for migration during conflict. It leaves an incomplete picture of the complex decisions people must make in order to safeguard their lives, livelihoods, and future well-being and does not help to understand the composition of migration streams.

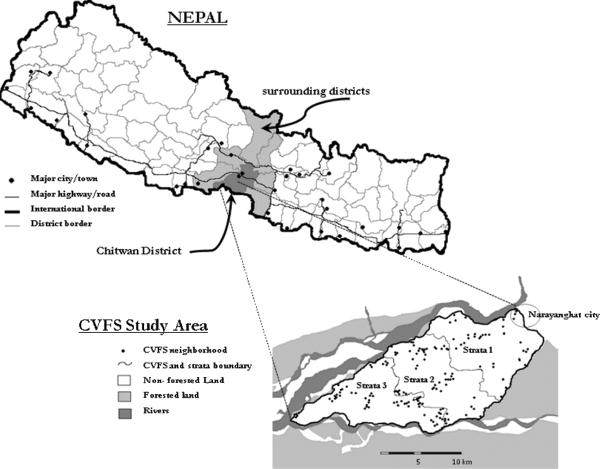

The study presented in this article is based on a multi-dimensional model of the migration decision that adds to the existing threat-based model and incorporates a broader social-ecological understanding of how people are differentially affected by conflict, which leads to variable migration responses. A diagram of this model is shown in Figure 1. The categories along the top of the diagram show the general pathway through which conflict can affect migration decisions. The categories include the conflict, the various consequences of conflict, the different resources that affect vulnerability to the consequences of conflict, and finally responsive behaviours, such as migration. Below the categories, is an example path diagram which shows some possible factors within each step of the pathway and how they influence the relationship between conflict and migration. The main premises of this model are that 1) armed conflict can have economic, social, and political consequences on civilian lives and livelihoods, in addition to physical threat; 2) these economic, social and political consequences can affect the motivation to migrate, independent of physical threat; and 3) access to resources can mitigate a person's vulnerability to these consequences and thereby moderate the relationship between conflict, consequences, and migration. Each of these premises is described in further detail in the sub-sections below.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework incorporating a socio-ecological perspective to examine migration decisions during armed conflict.

This model is not intended to replace existing theories of migration and forced migration. In fact, it is based on classic push-pull reasoning and argues that economic characteristics and social capital are still important to the explanation of migration in the context of conflict and thus should be taken into account. However, given the drastic changes to social and economic context during conflict, this model seeks to address the additional pathways through which economic and social structures affect migration during periods of widespread violence.

The Social, Economic, and Political Consequences of Conflict

Although physical threat is undoubtedly an important motivation to migrate away from conflict, it is only one of the many ways in which conflict affects individuals and families. There are also a variety of deleterious social, economic and political consequences both during and after conflict or violent events. This is shown with pathway “1” in Figure 1. Thus, in seeking to understand how people respond to conflict, we must examine the inclusive effects on people's lives that condition the context within which they make migration decisions.

First, armed conflict can disrupt livelihoods. It can limit people's ability to go to work and to farm. It can disrupt access to markets and increase commodity prices and taxes (Collier 1999; Gebre 2002; Bundervoet and Verwimp 2005; Mack 2005; Verpoorten 2005; Justino 2006). Civilians often face destruction of personal property including homes, farms, and other assets (Justino 2006; Shemyakina 2006). Second, social and political life can be disrupted by conflict. Research has shown that it can affect children's schooling, access to health services, marriage and fertility (Lindstrom and Berhanu 1999; Agadjanian and Prata 2002; Caldwell 2004; Mack 2005; Justino 2006; Shemyakina 2006; Heuveline and Poch 2007; Williams et al. 2010). The vast social upheaval of armed conflict can also change social relationships and leadership hierarchies.

The second premise of this model is that these economic, social and political consequences can affect the motivation to migrate. This is illustrated with pathway “2” in Figure 1. There is strong theoretical support from the neo-classical economics of migration and new economics of migration theories as well as and consistent empirical evidence that social, economic, and political factors affect migration during periods of relative peace (Stark and Bloom 1985; Massey 1990; Stark and Taylor 1991; Massey and Espinosa 1997; Massey et al. 1998; VanWey 2005; Massey et al. 2010). There is also empirical evidence from both ethnographic and statistical studies that economic, social, and political factors can be motivations to migrate during periods of armed conflict in such disparate areas as Somalia, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Indonesia (Lundquist and Massey 2005; Engel and Ibanez 2007; Czaika and Kis-Katos 2009; Lindley 2010). Furthermore, anecdotal evidence from the conflict in Nepal suggests that in many cases violence alone was not a sufficient motivation for migration, but food insecurity, caused by disruptions to farming and trade, actually precipitated migration (Seddon and Adhikari 2003).

Community Organizations that Mitigate the Consequences of Conflict

The third premise of this model is that access to resources can mitigate vulnerability to these consequences and thereby moderate the relationship between conflict, consequences, and migration. In other words, not all people will experience the consequences of conflict in the same way. Those who have access to resources that support daily life at the origin, such as community organizations will experience the danger and social and economic consequences of conflict to a lesser extent. This is shown as pathway 3 in Figure 1. This concept of vulnerability is not new in the sociological literature, and instead has a strong history in the study of natural disasters and other crises (Klinenberg 2002; Wisner 2004; Browning et al. 2006). In fact, in the case of natural disasters, social vulnerability is defined as, “the characteristics of a person or group in terms of their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from the impact of a natural hazard” (Wisner et al. 2004, p.11).

Extending this discussion to migration, if danger, social, and economic consequences form the motivation for migration during armed conflict, then we can expect that vulnerability will moderate the effect of conflict on migration. In other words, those who are more vulnerable and less able to cope with, resist, and recover from armed conflict, will experience the consequences to a greater extent and will therefore be more likely to migrate away as an alternative strategy to cope with conflict. This is path 4 in Figure 1.

In addition to the various individual and household characteristics that can affect vulnerability, community organizations can mitigate the social, economic, and political consequences of conflict. Evidence shows that community organizations that provide social support and a forum for developing strong social relationships can help people to better adapt to and cope with the social and psychological consequences of conflict and crises (Creamer et al. 1993; Norris and Kaniasty 1996; Carr et al. 1997; Hobfoll and Lilly 1993; Jenkins 1997; Kwon et al. 2001; Galea et al. 2002; Tracy et al. 2008). Similarly, organizations that provide economic support can help people to better cope with the economic consequences of conflict. For example, in the event that an individual or family suffers economic set-backs through destruction of their home, farm, or business during armed conflict, community organizations such as farmer's cooperatives can provide small loans or a ready source of reciprocal labour to rebuild that which was destroyed. Finally, organizations that provide health services could also function to moderate the impact of conflict on migration responses. Health services, which can treat injuries sustained from violence, can help people to better recover from the physical consequences of conflict.

Note that the pathways described here relate specifically to community organizations and other resources that mitigate the consequences of armed conflict. There are other mechanisms through which different kinds of resources could influence migration in different or even opposite directions. For example, wealth could provide the means to finance a migration. Thus, we would expect this resource to increase, not decrease, the likelihood of migration. This can be contrasted with the micro-credit facilities, as described above, which provide access to capital, but capital that must be used at the origin.

In summary, through the provision of support for daily living at the origin, community organizations can decrease vulnerability to conflict through fostering resilience and helping people to cope with the significant social and economic consequences of generalized violence. People with access to these organizations likely experience the consequences of conflict to a lesser extent than those without access and thereby will be less likely to adopt migration as a coping strategy to deal with conflict. This model suggests the following hypothesis:

H0: People with access to community organizations that provide support for daily living will be less likely to migrate during armed conflict than people without access to community organizations.

The remainder of this article is devoted to describing empirical tests of this hypothesis as initial assessments of the value of the model presented here.

Context and Setting

The empirical analysis in this study was based in the Chitwan Valley of Nepal during the recent Maoist insurrection from 1996–2006. This provides an excellent case example because it is reasonably comparable to the settings of many of the on-going conflicts around the world today. First, the generally poor living conditions and reliance on subsistence agriculture in rural Nepal are similar to much of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Second, the conflict in Nepal was similar in many ways to the majority of the on-going conflicts around the globe. In 2006 it was categorized as `intrastate' and `minor', the same as 84 per cent of the on-going conflicts that year (Harbom and Wallensteen 2007). More specifically, the general conduct of the conflict in Nepal makes it comparable to many others around the world that include: a government fighting against a non-governmental rebel group; guerrilla tactics and no official frontline which affected civilian daily lives; and severe political and economic instability that accompanied the violence.

The Conflict in Nepal

The conflict in Nepal began in 1996 when the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) declared “People's War” with the aim to unseat the monarchy and install a democratic republic. The earlier stages of the conflict were contained in several mid-western districts and aimed at damage to government installations. From mid-2000 however, the Maoists progressively expanded their campaign nationwide. In 2001, the Nepalese government responded by creating a special armed police force to fight the Maoists, beginning the nationwide conflict. Serious peace talks commenced in June 2006 and in November of that year, the government and Maoists signed a comprehensive peace agreement declaring an end to the conflict. During the conflict, civilians were routinely caught up in fire fights and bomb blasts. They also experienced torture, extra-judicial killings, abductions, arrests without warrant, house raids, forced conscription, billeting, extortion, and general strikes that disrupted economic and social activity across the country (Hutt 2004; Pettigrew 2004; South Asia Terrorism Portal 2006a).

The Chitwan Valley of Nepal

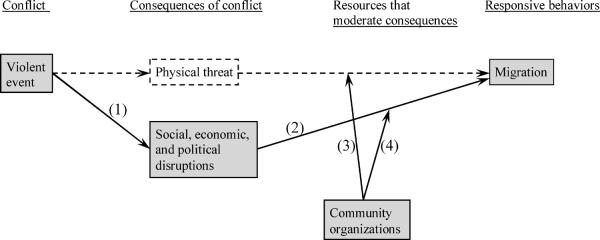

This study was based in the Chitwan Valley of south-central Nepal. A map of the study area, with sample neighbourhoods and geographic features is shown in Figure 2. The valley is flat, fertile, and dominated by agriculture. There is one large city, Narayanghat, and the rest of Chitwan's population, like much of Nepal, lives in small, rural villages. Most villages are connected to other villages and larger roads by paths or dirt roads.

Figure 2.

Map of Nepal and Chitwan Valley Family Study area.

Historically, there has been a large amount of migration from Chitwan to other areas of Nepal and India. Nepal and India share an open border, so there are no restrictions on cross-border travel, making this international migration no more difficult than migration to other areas of Nepal. Before the conflict, much of the migration was seasonal and used as a strategy to supplement regular farm and household incomes (Thieme and Wyss 2005; Kollmair et al. 2006). Because of the short-term nature of migration from Chitwan, most migrants moved alone and remitted large amounts of money, while other family members stayed at home to care for children, land, and livestock (Gill 2003; Thieme and Wyss 2005; Kollmair et al. 2006). It was relatively rare for whole households to move together. These patterns are still common; between 1997 and 2006, 63 per cent of adults in the Chitwan Valley Family Study (described in detail below) migrated at least once, where a much smaller 27 per cent of households migrated.

Migration patterns in Chitwan during the pre-conflict period were heavily structured by sex and age. Historically, men were much more likely to migrate for labour. However, the gender gap in migration is closing with time. In recent decades women have become increasingly more likely to migrate and this change is likely driven by higher female education and increasing numbers of women in the non-family paid workforce (Williams 2009). As in most countries around the world, age is also a key factor in migration. Before and during the conflict there were high rates of migration amongst people between the ages of 20 and 30, and progressively decreasing rates of migration after the age of 30 (Bohra and Massey 2009, 2011; Williams 2009).

Data and Measures

Empirical analyses for this study covered a period of nine years, from June 1997 which was three years before the outbreak of nation-wide violence, and continuing for six more years during the violence until January 2006. As such, this is an unusual opportunity to study migration patterns during armed conflict in comparison with migration patterns during a period of relative peace before the conflict.

Three separate kinds of data were used - survey data about individuals, survey data about communities, and data about violent events involved with the conflict. Data on violent events came from the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), an NGO that compiles records of all violent events in Nepal. Measures of individual and community characteristics came from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS), a large-scale multidisciplinary study of the western part of the Chitwan Valley of Nepal, designed to investigate the impact of macro-level socioeconomic changes on micro-level individual behaviour.

The CVFS provides several data sets, including an individual interview and life history calendar that were collected in 1996. A prospective demographic event registry that was collected monthly beginning in 1997 was the source of migration data. The prospective nature of these data make them ideal for studying migration, by providing information on a representative sample of all people exposed to the possibility of migration. From a demographic perspective, and for addressing questions of composition of migration streams, this is highly preferable to surveys that sample at migrant destinations such as refugee or IDP camps. In fact, the scarcity of representative origin-based samples is likely one of the main reasons that there is little empirical research on composition issues.

Response rates for the CVFS are exceptional. For the individual interview and life history calendar, the CVFS obtained responses from 97 per cent of the original sample. Response rates for the prospective demographic event registry were influenced by attrition, but were still high, at 94 per cent by 2006.

The demographic registry includes 151 neighbourhoods that were selected with an equal probability, systematic sample that used a two-stage sampling procedure. First, the study area was divided into three distinct strata (as marked in Figure 2), based on distance to the one urban area in Chitwan, the city of Narayanghat in the northeast corner of the study area. Each stratum is progressively more rural with lower population density. Second, a random sample of neighbourhoods was selected from each stratum. Within each selected neighbourhood, every household and individual aged 15 to 59 was interviewed. Further detail on the sampling strategy and the CVFS is available in Barber et al. 1997 and Axinn et al. 1999. The sample in this study was restricted to those who were between the ages of 18 and 59 at the beginning of the study in June 1997. This excluded those who are likely too young or old to be living independently and the vast majority of young people who could still be enrolled in school. This results in a sample of 3353 people.

As with any study of armed conflict, there is a potential that excessive conflict-related mortality in the sample could bias results. In this case however, violent deaths were not common. Although there was a high level of violence in Chitwan, the vast majority of violent acts resulted in physical and mental damage and imprisonment, but not death. There were a total of 200 conflict-related deaths in the district during the period of this study (INSEC 2011). However, given that the 3353 respondents in this study are a small proportion of the approximately 472,000 residents of Chitwan District, it is unlikely that many of the CVFS respondents experienced conflict-related deaths.

Measures of Violence

Violence was measured with one kind of specific, easily observable, and threatening violent event—major gun battles. SATP provides records of the date and district of each major gun battle in Nepal starting from November 2001. These records were corroborated by CVFS staff resident in Chitwan throughout the full period of the study. A measure of the number of major gun battles per month in the local area was used in this study. The local area that can influence Chitwan residents' perceptions of threat was defined as Chitwan and the six neighbouring districts (Nawalparasi, Tanahu, Gorkha, Dhading, Makwanpur, and Parsa). These districts are small, more comparable to U.S. counties than states. The combined area of these seven districts is approximately the same as Connecticut, one of the smallest U.S. states.

For the time period that these data do not cover, from the beginning of the study in June 1997 until November 2001, the number of major gun battles was coded as zero. News reports and research show that the conflict was at a very low intensity before 2001 and CVFS staff report that there were few violent events before 2002. Thus this coding strategy for the period before 2002 is likely the closest representation of reality. It is also a conservative approach that is more likely to underestimate than overestimate the effect of gun battles on migration.

Migration

Migration was measured using the CVFS prospective demographic event registry which features residence records for each individual in the sample for every month. Migration was defined as an absence of one month or longer from an individual's original 1996 residence. This precise definition has been used successfully in past research (Williams 2009; Massey et al. 2010) and allows for the inclusion of both temporary and permanent migrants. This is important for the study of conflict, when migration durations can vary significantly. Over the 104 month period of this study, 63 per cent of the sample population migrated at least once using this definition. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for this and all other measures used in this study.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the Chitwan Valley Family Study sample

| Measure | Range | Mean/Median | Std dev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit of measure = month | N=104 | |||

| Conflict | ||||

| Gun battles | (0–4) | 0.19 / 0 | 0.62 | |

|

| ||||

| Unit of measure = community | N=151 | |||

| Community organizations in 1997 | ||||

| Market within 5 minutes walk | (0,1) | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Cooperative within 10 minutes walk | (0,1) | 0.09 | 0.29 | |

| Mill within 5 minutes walk | (0,1) | 0.42 | 0.49 | |

| Health centre within 10 minutes walk | (0,1) | 0.42 | 0.49 | |

| Police post within 10 minutes walk | (0,1) | 0.07 | 0.25 | |

|

| ||||

| Unit of measure = person | N=3353 | |||

| Individual characteristics in 1997 | ||||

| Sex (female) | (0,1) | 0.53 | 0.50 | |

| Age | (18–62) | 35.26 | 11.53 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | (0,1) | 0.12 | 0.32 | |

| Married, living with spouse | (0,1) | 0.68 | 0.47 | |

| Married, not living with spouse | (0,1) | 0.15 | 0.36 | |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | (0,1) | 0.05 | 0.21 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Brahmin/Chhetri | (0,1) | 0.47 | 0.50 | |

| Dalit | (0,1) | 0.10 | 0.30 | |

| Hill Indigenous | (0,1) | 0.15 | 0.36 | |

| Terai Indigenous | (0,1) | 0.21 | 0.41 | |

| Newar | (0,1) | 0.06 | 0.24 | |

| Migration experience | ||||

| Ever migrated during study period | (0,1) | 0.63 | 0.48 | |

| Ever migrated before 1997 | (0,1) | 0.26 | 0.44 | |

| Number of migrations since 1997 | (0–18) | 1.39 | 2.12 | |

| Months away on last migration | (0–107) | 5.33 | 12.16 | |

| Months back since last migration | (0–107) | 65.49 | 44.16 | |

| Number of children | (0–16) | 3.17 | 2.53 | |

| Educational attainment | (0–16) | 4.01 | 4.48 | |

| Wage or salary job | (0,1) | 0.45 | 0.50 | |

| Amount of land owned (acres) | (0–17) | 2.06 | 2.44 | |

| Distance to Narayanghat | (0–18) | 8.68 | 4.05 | |

Theory and empirical evidence indicate that a strong predictor of migration is previous migration experience (Findley 1987; Massey and Espinosa 1997). For this reason, several measures of migration experience were used to control for migration-specific human capital. These include if the respondent had ever migrated before 1997, the number of times they migrated since 1997, the length of time they were away on the most recent migration spell, and the length of time they lived in their Chitwan neighbourhood since returning from the most recent migration spell. Again, the regular prospective collection of data was integral to these exceptionally precise measures of migration specific human capital.

Community Organizations

Measures of community organizations came from the CVFS neighbourhood history calendar which was collected in 2006 using archival, ethnographic, and structured interview methods (Axinn et al. 1997) to record a detailed annual history of key services and organizations in each neighbourhood. Thus all measures of community organizations were time-varying on an annual basis. This is particularly important in a conflict period, when the violence could (and in a few cases did) cause some organizations to close down.

The community organizations used include markets, health centres, farmer's cooperatives, and mills. Police posts were also used as a control in all models. Markets were defined as any place with two or more contiguous shops or stalls that sell goods. As places for people to buy and sell produce and other goods, markets provide economic opportunities. They can also serve as informal community meeting places and foster and maintain strong community relationships. Health centres were defined as any facility that provides health care, including health posts, centres, and hospitals. Along with health care, these centres often provide educational and community outreach programs. Farmer's cooperatives and mills are facilities that enable small farmers to process and market grain, milk, and other farm produce. Many cooperatives also have micro-credit functions and provide small loans to members in times of need. Thus, cooperatives and mills provide economic support as well as a forum for social relationships to develop.

For all of these organizations the CVFS neighbourhood history calendar recorded the distance in walking time from each neighbourhood to the nearest service. These travel times were coded into dichotomous measures for access to each of these organizations. Markets and Mills were coded `1' if a neighbourhood was within 5 minutes walk of a market or mill, and `0' if it was further. For farmer's cooperatives, health centres, and police posts, a distance of ten minutes walk was used. Dichotomous variables using different distances to each of these organizations, such as 5, 10, and 20 minutes walk, were tested. The walking distances used in the study were the strongest operationalizations for these measures. Other research in this study area has shown that dichotomous measurements of five and ten minutes walk to markets are significant predictors of contraception, marriage, and education (Axinn and Yabiku 2001; Beutel and Axinn 2002; Yabiku 2004). In addition to the empirical evidence that these specific distances are important, they also make sense conceptually. Considering how people use each service, markets and mills often require users to transport a large amount of goods (produce and grain respectively) to and from the organization. Health centres, and farmer's cooperatives require smaller loads to transport. Thus it is reasonable that people are willing to travel further for the organizations that require them to transport smaller loads, whereas larger loads effectively decrease the distance that people might consider functionally accessible.

Individual Demographic Characteristics

In order to accurately estimate the effects of violence and community organizations on migration, a variety of individual- and household-level characteristics were included in the models that could confound the relationships of interest. These include age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, children, education, work outside the home, land ownership, and distance to the nearest urban area. Migration theory and empirical evidence have shown that these characteristics are related to migration patterns in Nepal and other countries (Harris and Todaro 1970; Stark and Bloom 1985; Massey 1990; Pedraza 1991; Stark and Taylor 1991; Donato 1993; Shrestha et al. 1993; Massey and Espinosa 1997; Vanwey 2005; Williams 2009; Massey et al. 2010).

Dichotomous variables were used to measure sex and whether a respondent was working outside the home in 1996. A series of dichotomous variables were used to measure the five main ethnic groups in this area, and marital status. Continuous variables were used for age, children (the number of children ever born who are 15 years old or younger), educational attainment, urban proximity (distance to the urban area of Narayanghat), and the amount of land owned. Land ownership is skewed, so the natural log of land ownership was used instead.

Where data are available, time-varying measures were used. Marital status and the number of children came from the demographic event registry and were therefore time-varying. Age was also time-varying. Land ownership was measured with surveys that were undertaken in 1996 and 2001. Thus reported land ownership in 1996 was used for the land measure for the years 1997 through 2000 and reported land ownership in 2001 was used for 2001 through 2006. All other individual characteristics, including sex, work outside the home, ethnicity, and educational attainment were non-time varying and measured in 1996.

In order to control for regular seasonal migration patterns in the Chitwan Valley, a series of eleven dichotomous variables for each month of the year were included in all models. In addition, it was necessary to control for duration effects, or the selectivity of migration over time since the survey started, and any other sources of temporal variation during the study period, including other conflict-related events, economic instability, and changes in cultural norms and attitudes. To do this, a fixed effects approach to measure years was used, with a series of nine dichotomous variables for each year of the study. This is a relatively conservative strategy that controls for any other exogenous changes over time, leaving a greater chance that the effects over time that were observed were due to variations in the number of gun battles.

Analytic Strategy

Discrete-time event history models were used to predict out-migration from the Chitwan Valley. Person-months were the unit of exposure to risk. The models tested the monthly hazard of migration out of the Chitwan Valley neighbourhood after June 1997, contingent upon major gun battles and access to community organizations. Gun battles were lagged by one month in order to assure that the result being measured (migration) occurred chronologically after the event. The moderating effects of community organizations on the conflict-migration relationship were assessed with interactions of each community measure with gun battles.

All models used the logistic regression equation given below:

where p is the probability of migrating out of the Chitwan neighbourhood, is the odds of migrating out, a is a constant term, Bk is the effect of independent variables in the model, and Xk is the value of these independent variables. Multi-level modelling techniques were used to adjust for autocorrelation that might have resulted from the clustering of sample respondents at the neighbourhood level (Barber et al. 2000). This strategy has been successfully used with these data and similar measures (Axinn and Barber 2001; Yabiku 2004; Brauner-Otto et al. 2007).

Notably, the models analyzed any migration, including first and higher order migrations. This was implemented by creating a data set that excluded a migrant for the period of time they were living out of the origin neighbourhood. When a migrant returned to their original neighbourhood, they were again included in the data set. As noted above, an extensive battery of measures to control for migration experience were used. However, these data were potentially subject to selection bias of migrants, created by overrepresentation of migrants who returned quickly, compared to migrants who returned after long periods of time or did not return at all. To address this possible bias, the same models used here were tested with an outcome of first migration. Results indicated no difference between migration patterns in the first migration and the any migration tests.

As with all analyses of neighbourhood-level effects on individual behaviour, these analyses faced a common set of problems that could threaten the validity of the results. The biggest issues in this case were selective migration into specific neighbourhoods and endogenous influences on the neighbourhood characteristics (or non-random placement of neighbourhood organizations). The detail available in the CVFS data allowed for the use of different strategies to address these issues and to assess the extent to which they might have threatened empirical results.

Models were tested using a fixed effects approach for neighbourhoods. This strategy involved using a dichotomous indicator for each neighbourhood to control for neighbourhood-specific effects. It is a relatively conservative strategy that isolates the effects of community organizations by controlling for all other ecological differences between neighbourhoods. Estimates from these fixed effects models produced results that were substantively equivalent to models without fixed effects.

In this setting, some community organizations, such as cooperatives, health centres, and police posts are generally initiated by an outside source while others, such as mills and markets, are more likely to have been created within the community. Model results for both types of organizations were similar, suggesting that there were no significant differences in reactions to violent events and the interactions of violent events and community organizations based on neighbourhood differences or the type of organization.

A final concern with analysis of neighbourhood effects is that the location of gun battles might be spatially correlated with the density of community organizations. If this were the case, location of gun battles would be a spurious factor that could threaten the validity of the empirical results in this study which provided evidence of a relationship between community organizations and migration. An ideal method to address this concern would be to test for spatial correlations between gun battles and density of community organizations. The SATP data that were used in this study are accurate only to the district level and thus do not provide locations of gun battles that were precise enough to make this ideal analysis possible.

However, reports and records from non-governmental human rights organizations and the news media indicate that the locations of gun battles were either at police posts and army barracks (in cases where the Maoists attacked government forces) or were randomly distributed throughout the countryside and neighbourhoods (INSEC 2004, 2006; SATP 2006a, 2006b). There is no indication that gun battles were concentrated in areas that were more or less remote or had more or less community organizations (besides police posts). The non-random placement of many gun battles at police posts could affect the results in this study, if the location of police posts was highly correlated with the location of markets, mills, coops, and health centres. This possibility was tested using CVFS data on access to police posts. The results showed weak correlations between locations of police posts and community organizations. Furthermore, access to police posts was controlled in all models. Models that included an interaction term for gun battles and police posts were also tested. The results from models that did and did not control for police posts and interactions with police posts were almost identical. In addition, police posts did not significantly affect migration in any model. These empirical tests provided reasonably strong evidence that the location of gun battles probably did not threaten the validity of the results in this study.

Results and Discussion

Demographic Characteristics and Migration

As shown in Table 2, several demographic characteristics had strong influences on out-migration. The odds ratio of 0.72 for females indicates that women were about 30 per cent less likely to migrate than men at any time. The odds ratio for age, 0.97, suggests that we can expect an individual to be about three per cent less likely to migrate with each additional year of age. These results are similar to evidence from around the world that young adults and men are the most likely to migrate (Massey and Espinosa 1997; Massey et al. 1998; VanWey 2005).

Table 2.

Logistic regression estimates of discrete-time hazard models of out-migration from Chitwan Valley

| Model 1 | Odds ratio | Z statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Conflict | ||

| Major gun battles | 1.09** | (2.59) |

| Community organizations | ||

| Market | 0.94 | (1.02) |

| Farmer's cooperative | 1.14 | (1.19) |

| Mill | 1.02 | (0.34) |

| Health centre | 1.06^ | (1.32) |

| Police post | 1.13 | (0.88) |

| Individual characteristics | ||

| Sex (female) | 0.72*** | (9.08) |

| Age | 0.97*** | (13.18) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 1.02 | (0.34) |

| Married, living with spouse | Reference | |

| Married, not living with spouse | 1.23*** | (5.20) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 1.63*** | (7.05) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Brahmin/Chhetri | Reference | |

| Dalit | 1.12* | (1.74) |

| Hill Indigenous | 1.11* | (1.92) |

| Terai Indigenous | 0.87* | (2.15) |

| Newar | 0.87* | (2.01) |

| Migration experience | ||

| Ever migrated before 1997 | 1.44*** | (11.16) |

| Number of migrations since 1997 | 1.40*** | (46.29) |

| Months away on last migration | 1.03*** | (7.59) |

| Months back since last migration | 1.00^ | (1.57) |

| Number of children | 0.97*** | (3.21) |

| Educational attainment | 1.04*** | (8.71) |

| Wage or salary job | 1.16*** | (4.88) |

| Amount of land owned | 0.98^ | (1.60) |

| Distance to Narayanghat | 1.01* | (1.65) |

| Months of the year | ||

| January | 0.99 | (0.19) |

| February | 1.00 | (0.02) |

| March | 1.09 | (1.25) |

| April | 0.98 | (0.27) |

| May | 1.06 | (0.83) |

| June | Reference | |

| July | 0.75*** | (4.15) |

| August | 1.18** | (2.63) |

| September | 1.18** | (2.71) |

| October | 0.73*** | (4.53) |

| November | 0.99 | (0.10) |

| December | 0.99 | (0.14) |

| Years | ||

| 1997 | Reference | |

| 1998 | 0.96 | (0.72) |

| 1999 | 0.75*** | (4.20) |

| 2000 | 0.70*** | (4.44) |

| 2001 | 0.67*** | (4.11) |

| 2002 | 0.54*** | (5.29) |

| 2003 | 0.45*** | (6.19) |

| 2004 | 0.23*** | (9.49) |

| 2005-Jan. 2006 | 0.34*** | (6.43) |

| Residual | 0.9612 | |

| Neighbourhood level error variance | 0.1070 | |

| -2 res log likelihood | 1,852,885 | |

Notes:

1. No. of observations (person-months) = 258,333

2. Community organizations are coded as accessible if they were within the following walking distance from the community: markets and mills- 5 minutes; farmer's cooperatives, health centres, and police posts- 10 minutes.

Statistical significance:

p<. 10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 (one-tailed tests).

Results also indicate that migration experience was another strong predictor of out-migration. Respondents who had migrated before 1997 were 1.40 times more likely to migrate during the study period. Each additional migration during the study period increased the likelihood of subsequent migrations another 1.44 times. Finally, each additional month spent away from Chitwan on their last migration, increased the likelihood of a subsequent migration by three per cent. These results are similar to empirical evidence from Mexico and support existing theories of migration which identify migration experience and social connections with others who have migration experience as important determinants of migration (Massey et al. 1987; Massey et al. 1993; Massey and Espinosa 1997).

Violence and Migration

Gun battles had strong effects on out-migration. As shown in Table 2, the odds ratio of 1.09 for major gun battles indicates that in a month following one gun battle, there was a nine per cent higher likelihood of migration than otherwise. In a month following two gun battles there was a 19 per cent higher likelihood of migration, and for four gun battles, a 41 per cent higher likelihood. The positive effects of gun battles were as expected, based on the threat-based model and evidence from other studies of migration during conflict (Schmeidl 1997; Davenport et al. 2003; Moore and Shellman 2004; Lundquist and Massey 2005; Melander and Oberg 2006).

Conflict, Community Organizations, and Migration

Models 2–5 (presented in Table 3) show the moderating effects of community organizations on the relationship between conflict and migration. Each of these models included variables for major gun battles, all community organizations, and one interaction variable. Results indicate that some community organizations had marginally significant main effects on the likelihood of migration, and that all of them moderated the relationship between conflict and migration in this setting.

Table 3.

Major gun battles, community organizations, and migration. Logistic regression estimates of out-migration from Chitwan Valley

| Model 2 Market | Model 3 Farmer's coop | Model 4 Mill | Model 5 Health centre | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactions | ||||

| Gun battles*market | 0.88* (2.19) | |||

| Gun battles*farmer's cooperative | 0.73** (2.36) | |||

| Gun battles*mill | 0.79*** (3.92) | |||

| Gun battles*health centre | 0.89* (2.17) | |||

| Conflict | ||||

| Gun battles (# per month) | 1.16*** (3.50) | 1.11*** (3.16) | 1.20*** (4.66) | 1.16*** (3.49) |

| Organization | ||||

| Market | 0.95 (0.83) | 0.93 (0.98) | 0.93 (1.01) | 0.93 (1.01) |

| Farmer's cooperative | 1.14 (1.19) | 1.17^ (1.31) | 1.14 (1.09) | 1.14 (1.11) |

| Mill | 1.02 (0.39) | 1.02 (0.35) | 1.05 (0.87) | 1.02 (0.40) |

| Health centre | 1.06^ (1.35) | 1.06^ (1.37) | 1.06^ (1.36) | 1.08^ (1.63) |

| Police post | 1.13 (0.87) | 1.13 (0.88) | 1.13 (0.85) | 1.13 (0.86) |

| Residual | 0.9597 | 0.9587 | 0.9584 | 0.9611 |

| Neighbourhood level error variance | 0.1070 | 0.1073 | 0.1070 | 0.1070 |

| -2 res log likelihood | 1,852,695 | 1,852,395 | 1,852,653 | 1,852,933 |

Notes:

1. Estimates are presented as odds ratios. Z statistics are given in parentheses.

2. No. of observations (person-months) = 258,333

3. All control variable used, but results not shown.

4. Community organizations are coded as accessible if they were within the following walking distance from the community: markets and mills- 5 minutes; farmer's cooperatives, health centres, and police posts- 10 minutes.

Statistical significance:

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 (one-tailed tests)

Model 2 includes the interaction term for gun battles and markets. The coefficient for access to a market was not statistically significant. The coefficient for gun battles was positive (and statistically significant), as we would expect. This effectively estimates the effect of gun battles on migration for people without access to markets. The interaction term for gun battles and markets, which shows the moderating effect of markets on the gun battles-migration relationship, was negative and statistically significant, with an odds ratio of 0.88. This means that while the effect of gun battles on migration was positive for people without access to markets, it was less positive for those with access to a market in their neighbourhood.

Figure 3 shows this result graphically. It displays the predicted probability of migration after any number of gun battles, for people with and without access to markets. These predicted probabilities are calculated for `average' men and women, meaning that the calculations were undertaken using the mean values (shown in Table 1) for each independent variable in the logistic regression equation and the arbitrarily chosen date of February 2004. For example, an `average' person would be 35 years old, married, have three children, etc. As shown in Figure 3, for men and women with access to markets, the probability of migration slightly increased for increasing numbers of gun battles per month. For men and women without access to markets, the probability of migration increased much faster. The difference in migration probabilities between those with and without markets, shown by the solid and dotted lines respectively, is the moderating effect of markets. Notice that this is very small (about 0.5 per cent) when there were no gun battles, but increases with the number of gun battles per month. Thus, an `average' woman with access to a market would be almost six per cent more likely to migrate after four gun battles than an `average' woman without access to a market. The difference in migration probabilities after four gun battles for `average' men is about 7.5 per cent.

Figure 3.

Predicted probability of migration after gun battles for `average' men and women, comparing those with and without access to markets.

Source: Regression results from Model 2 (Table 3).

The interactions between the other community organizations (health centres, farmer's cooperatives, dairies, and mills) and gun battles produced a similar pattern, as shown in Models 3–6. Independent of the main effect of these organizations on migration, the interactions between gun battles and these organizations are negative and statistically significant. Thus, we would expect all people to be more likely to migrate after gun battles. But those with access to a health centre, coop, or mill would be less likely to migrate after gun battles than those without access. These results all suggest that access to these community organizations dampened the effect of gun battles on migration. This supports the argument that economic, social, and health support provided by community organizations helps individuals to cope with physical threat and the economic and social consequences of gun battles.

Conclusion

Prior research on forced migration has shown that periods of armed conflict increase migration on an aggregate level. However, this subject is more complex than previous empirical research reveals. Armed conflict is rarely a single event and migration streams are composed of individuals who experience conflict in diverse ways. The main contribution of this study is the presentation and empirical evaluation of a conceptual model that adds to theories of migration and forced migration and aims to provide initial insight into existing micro-level variability in migration during armed conflict. This model uses a socio-ecological approach that requires analysis of the full range of consequences of armed conflict on people's lives and livelihoods and how these consequences interact with the broader context within which people live and make migration decisions.

Using data from the Chitwan Valley of Nepal, the empirical analyses described in this article show that specific resources in communities (such as markets, health centres, coops, and mills) systematically decreased the propensity of individuals in these communities to migrate in response to violent events. Results from these analyses support the proposition that community organizations can increase the ability to cope with the economic and social consequences of conflict. For example, in times of economic insecurity caused by conflict, farmer's cooperatives and mills organizations and can provide small loans and access to food banks as well as continued opportunities to process and sell farm produce. This enables people to rebuild or continue their lives and livelihoods in their current residences. Markets and health centres also provide forums for the development of strong social relationships that can support resiliency and coping during periods of conflict. Thus, community organizations are key factors that reduce vulnerability to the variety of consequences of armed conflict. These results and the underlying theoretical connection between community disadvantage (or comparative advantage) and resiliency and coping during periods of disaster are similar to evidence from recent studies in a number of areas which find that community organizations and support have impacts on mental illness after terrorist events and mortality and migration following natural disasters (Klinenberg 2002; Norris et al. 2002; Ahern et al. 2004; Browning et al. 2006; Myers et al. 2008; Tracy et al. 2008).

The micro-level data about individual and community characteristics within the conflict zone (or origin of migrants) used in this study provide a detailed and nuanced documentation of variations in migration behaviour in response to conflict. To date, the study of the causes of conflict-induced migration has been heavily influenced by the accessibility of data, which in many cases is either aggregate, based at the country-level, or collected at migrant destinations such as refugee or IDP camps which house selective groups of the full out-migrant population. These data limitations have hampered the ability to understand systematic micro-level variation and selection in migration rates. The analyses presented here demonstrate that micro-level documentation at migrant origins can substantially advance the study of both conflict-induced migration and also inquiries into other consequences of conflict on individuals, families, and communities.

While the empirical results in this study pertain specifically to Nepal, the conceptual model and supportive evidence should have substantial relevance to understanding the effects of conflict on individuals' lives and migration behaviours during conflicts in other parts of the world. Living conditions and the role of community-based organizations in providing small-scale support in Nepal are similar to that of much of the world's population in non-industrialized countries. In addition, the conflict in Nepal is comparable to many of the armed conflicts around the world today. Thus while the relationships between specific measures in this study might have few exact parallels with other settings, the broad conclusions relating different levels of violence, social and economic consequences of violence, community-level social and economic support, and migration decisions are highly relevant to understanding human behaviour during armed conflicts around the world.

In more general terms, this study provides evidence that those community organizations which help people to maintain current patterns of daily living function as sources of stability, partially counteracting the effect of armed conflict as a source of change. Similarities between evidence in this study and research on natural disasters highlights the likelihood that community organizations serve this same function during other periods of macro-level upheaval and change such as natural disasters, economic crises, and changes in government. Thus, this study has broad implications for understanding processes of social change and sources of stability during contexts of disaster and upheaval that routinely affect human societies around the world.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grants HD032912 and HD 033551) and the National Science Foundation (grant OISE 0729709). I thank William Axinn, Barbara Anderson, Sandro Galea, and John Delfeld for their comments on earlier versions of this article; Dirgha Ghimire and the Population and Ecology Research Laboratory in Rampur, Chitwan, Nepal for collecting the survey data and in-depth interviews used here; the South Asia Terrorism Portal for collecting records of violent events in Nepal; and Cathy Sun for programming assistance. All errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the author.

References

- Agadjanian Victor, Prata Ndola. War, peace, and fertility in Angola. Demography. 2002;39(2):215–231. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern Jennifer, Galea Sandro, Fernandez William, Koci Bajram, Waldman Ronald, Vlahov David. Gender, social support, and posttraumatic stress in postwar Kosovo. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192(11):762–770. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000144695.02982.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca Claire. Human rights abuses: Precursor to refugee flight? Journal of Refugee Studies. 1998;11(1):80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Barber Jennifer S., Ghimire Dirgha J. The neighborhood history calendar: A data collection method designed for dynamic multilevel modelling. Sociological Methodology. 1997;27(1):355–392. doi: 10.1111/1467-9531.271031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Pearce Lisa D., Ghimire Dirgha. Innovations in life history calendar applications. Social Science Research. 1999;28(3):243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Barber Jennifer S. Mass education and fertility transition. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(4):481–505. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Yabiku Scott T. Social change, the social organization of families, and fertility limitation. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106(5):1219–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell Oliver. Researching refugees: Lessons learned from the past, current challenges and future directions. Refugee Survey Quarterly. 2007;26(3):6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S., Shivakoti Ganesh P., Axinn William G., Gajurel Kishor. Sampling strategies for rural settings: A detailed example from Chitwan Valley Family Study, Nepal. Nepal Population Journal. 1997;6(5):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S., Murphy Susan A., Axinn William G., Maples Jerry. Discrete-time multilevel hazard analysis. Sociological Methodology. 2001;30(1):201–235. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel Ann M., Axinn William G. Gender, social change, and educational attainment. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2002;51(1):109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Black Richard. Fifty years of refugee studies: From theory to policy. International Migration Review. 2001;35(1):57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bohra Pratikshya, Massey Douglas S. Processes of internal and international migration from Chitwan, Nepal. International Migration Review. 2009;43(3):621–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohra-Mishra Pratikshya, Massey Douglas S. Individual decisions to migrate during civil conflict. Demography. 2011;48(2):401–424. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner-Otto Sarah R., Axinn William G., Ghimire Dirgha J. The spread of health services and fertility transition. Demography. 2007;44(4):747–770. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning Christopher R., Wallace Danielle, Feinberg Seth L., Cagney Kathleen A. Neighborhood social processes, physical conditions, and disaster-related mortality: The case of the 1995 Chicago heat wave. American Sociological Review. 2006;71(4):661–678. [Google Scholar]

- Bundervoet Tom, Verwimp Philip. Civil war and economic sanctions: Analysis of anthropometric outcomes in Burundi. Households in Conflict Working Paper No. 11. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John C. Social upheaval and fertility decline. Journal of Family History. 2004;29(4):382–406. [Google Scholar]

- Carr Vaughan, Lewin Terry J., Webster Rosemary A., Hazell Philip L., Kenardy Justin A., Carter Gregory L. Psychological sequelae of the 1989 Newcastle earthquake: III. role of vulnerability factors in post-disaster morbidity. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(1):167–177. doi: 10.1017/s003329179600428x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castles Stephen. Towards a sociology of forced migration and social transformation. Sociology. 2003;37(1):13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Collier Paul. On the economic consequences of civil war. Oxford Economic Papers. 1999;50(4):168–83. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer Mark, Burgess Philip M., Buckingham William J., Pattison Phillipa. Post-trauma reactions following a multiple shooting: A retrospective study and methodological inquiry. In: Wilson J, Raphael B, editors. International Handbook of Traumatic Stress Syndromes. Plenum Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Czaika Mathias, Kis-Katos Krisztina. Civil conflict and displacement: Village-level determinants of forced migration in Aceh. Journal of Peace Research. 2009;46(3):399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport Christina, Moore Will, Poe Steven. Sometimes you just have to leave: Domestic threats and forced migration, 1964–1989. International Interactions. 2003;29(1):27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine. Current trends and patterns of female migration: Evidence from Mexico. International Migration Review. 1993;27(4):748–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel Stefanie, Ibanez Ana María. Displacement due to violence in Colombia: A household level analysis. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2007;55(2):335–65. [Google Scholar]

- Findley Sally E. An interactive contextual model of migration in Ilocos Norte, the Philippines. Demography. 1987;24(2):163–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea Sandro, Ahern Jennifer, Kilpatrick Dean, Bucuvalas Michael, Gold Joel, Vlahov David. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(13):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre Yntiso. Contextual determination of migration behaviours: The Ethiopian resettlement in light of contextual constraints. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2002;15(3):265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gibney Mark, Apodaca Claire, McCann James. Refugee flows, the internally displaced and political violence (1908–1993): An exploratory analysis. In: Schmid A, editor. Whither Refugee? The Refugee Crisis: Problems and Solutions. Ploom; Leiden: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gill Gerard J. Working paper 218. Overseas Development Institute; London: 2003. Seasonal labor migration in rural Nepal: A preliminary overview. [Google Scholar]

- Harbom Lotta, Wallensteen Peter. Armed conflict, 1989–2006. Journal of Peace Research. 2007;44(5):623–634. [Google Scholar]

- Harris John R., Todaro Michael P. Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis. American Economic Review. 1970;60(1):126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline Patrick, Poch Bunnach. The Phoenix population: Demographic crisis and rebound in Cambodia. Demography. 2007;44(2):405–426. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll Stevan E., Lilly Roy S. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21(2):128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hutt Michael. Monarchy, democracy and Maoism in Nepal. In: Michael Hutt., editor. Himalayan People's War: Nepal's Maoist Revolution. Indiana University Press; Bloomington Indiana: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nepal Human Rights Yearbook 2004. INSEC; Kathmandu: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nepal Human Rights Yearbook 2006. INSEC; Kathmandu: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Number of victims killed by state and Maoist in connection with the “People's War”. [accessed 14 June 2011];2011 Available at: http://www.insec.org.np/pics/1247467500.pdf,

- Jenkins Sharon Rae. Coping and social support among emergency dispatchers: Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1997;12(1):201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Richard C. Causes of Salvadoran migration to the United States. Geographical Review. 1989;79(2):183–94. [Google Scholar]

- Justino Patricia. On the links between violent conflict and chronic poverty: How much do we really know? CPRC Working Paper 61. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Klinenberg Eric. Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollmair Michael, Manandhar Siddhi, Subedi Bhim, Thieme Susan. New figures for old stories: Migration and remittances in Nepal. Migration Letters. 2006;3(2):151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Young-Sook, Maruyama Soichiro, Morimoto Kanehisa. Life events and posttraumatic stress in Hanshin-Awaji earthquake victims. Environmental Health and Preventative Medicine. 2001;6(2):97–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02897953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley Anna. Leaving Mogadishu: Towards a sociology of conflict-related mobility. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2010;23(1):2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom David P., Betemariam Berhanu. The impact of war, famine, and economic decline on marital fertility in Ethiopia. Demography. 1999;36(2):247–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist Jennifer H., Massey Douglas S. Politics or economics? International migration during the Nicaraguan Contra war. Journal of Latin American Studies. 2005;37(1):29–53. doi: 10.1017/S0022216X04008594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack Andrew. Human Security Report 2005: War and Peace in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Alarcon Rafael, Durand Jorge, Gonzalez Humberto. Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index. 1990;56(1):3–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Arango Joaquin, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela, Taylor J.Edward. Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review. 1993;19(3):431–66. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Espinosa Kristin E. What's driving Mexico-U.S. migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;102(4):939–999. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Arango Joaquin, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela, Taylor J.Edward. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Williams Nathalie, Axinn William G., Ghimire Dirgha. Community services and out-migration. International Migration. 2010;48(1):1–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melander Erik, Oberg Magnus. Time to go? Duration dependence in forced migration. International Interactions. 2006;32(2):129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Will, Stephen Shellman. Fear of persecution: Forced migration, 1952–1995. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2004;40(5):723–745. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison Anderew R., May Rachel A. Escape from terror: Violence and migration in post-revolutionary Guatemala. Latin American Research Review. 1994;29(2):111–32. [Google Scholar]

- Myers Candice A., Slack Tim, Singelmann Joachim. Social vulnerability and migration in the wake of disaster: The case of hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Population and Environment. 2008;29(6):271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Norris Fran, Kaniasty Krzysztof. Received and perceived social support in times of stress: A test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71(3):498–511. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris Fran H., Friedman Matthew J., Watson Patricia J., Byrne Christopher M., Diaz Eolia, Kaniasty Kryzsztof. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza Silvia. Women and migration: The social consequences of gender. Annual Review of Sociology. 1991;17:303–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.17.080191.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew Judith. Living between the Maoists and the army in rural Nepal. In: Hutt M, editor. Himalayan People's War: Nepal's Maoist Revolution. Indiana University Press; Bloomington Indiana: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond Anthony H. Sociological Theories of International Migration: The Case of Refugees. Current Sociology. 1988;36(7):7–24. doi: 10.1177/001139288036002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond Anthony H. Global Apartheid: Refugees, Racism, and the New World Order. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeidl Susanne. Exploring the causes of forced migration: A pooled time-series analysis, 1971–1990. Social Science Quarterly. 1997;78(2):284–308. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz T. Paul. Rural-urban migration in Colombia. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1971;53(2):157–63. [Google Scholar]

- Seddon David, Adhikari Jagannath. Conflict and Food Security in Nepal: A Preliminary Analysis. Rural Reconstruction Nepal (RRN); Kathmandu: 2003. (RN Report Series). [Google Scholar]

- Shemyakina Olga. The effect of armed conflict on accumulation of schooling: Results from Tajikistan. Households in Conflict Working Paper No. 12. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha Nanda R. Frontier settlement and landlessness among hill migrants in Nepal Tarai. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1989;79(3):370–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha Nanda R., Velu Raja P., Conway Dennis. Frontier migration and upward mobility: The case of Nepal. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1993;41(4):787–816. [Google Scholar]

- Sjaastad Larry A. The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economy. 1962;70(5):80–93. [Google Scholar]

- South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) Major Incidents of Terrorist Violence in Nepal, 1999–2006. South Asia Terrorism Portal; 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) Fatalities in Major Clashes between Security Forces and Maoist Insurgents since November 23, 2001. [Accessed 3 June 2011];2006b Available at: http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/nepal/database/majorattacks.htm.

- Stanley William Deane. Economic migrants or refugees? A time-series analysis of Salvadoran migration to the United States. Latin American Research Review. 1987;22(1):132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Stark Oded, Bloom David E. The new economics of labor migration. American Economic Review. 1985;75(2):173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Stark Oded, Taylor J. Edward. Migration incentives, migration types: The role of relative deprivation. The Economic Journal. 1991;101(408):1163–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. Edward. Undocumented Mexico-U.S. migration and the returns to households in rural Mexico. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 1987;69(3):616–38. [Google Scholar]

- Thieme Susan, Wyss Simone. Migration patterns and remittance transfer in Nepal: A case study of Sainik Basti in western Nepal. International Migration. 2005;43(5):59–96. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro Michael P. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. The American Economic Review. 1969;59(1):138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro Michael P., Maruszko Lydia. Illegal immigration and US immigration reform: A conceptual framework. Population and Development Review. 1987;13(1):101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy Melissa, Hobfoll Stevan E., Canetti-Nisim Daphna, Galea Sandro. Predictors of depressive symptoms among Israeli Jews and Arabs during the Al Aqsa Intifada: A population-based cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18(6):447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turton David. RSC working paper No. 12. Refugee Studies Centre; Oxford: 2003. Conceptualizing forced migration. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hear Nicholas. New Diasporas: the Mass Exodus, Dispersal and Regrouping of Migrant Communities. University of Washington Press; Seattle, WA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- VanWey Leah K. Land ownership as a determinant of international and internal migration in Mexico and internal migration in Thailand. International Migration Review. 2005;39(1):141–172. [Google Scholar]

- Verpoorten Marijke. Self-insurance in Rwandan households: The use of livestock as a buffer stock in times of violent conflict; CESifo Conference; Munich. 2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williams Nathalie. Education, gender, and migration in the context of social change. Social Science Research. 2009;38(4):883–896. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams Nathalie, Ghimire Dirgha, Axinn William, Jennings Elyse, Pradhan Meeta. A micro-level approach to investigating armed conflict and population responses. University of Michigan Population Studies Center Research Report. 2010:10–707. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner Ben, Blaikie Piers, Cannon Terry, Davis Ian. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People's Vulnerability and Disasters. Routledge; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yabiku Scott. Marriage timing in Nepal: Organizational effects and individual mechanisms. Social Forces. 2004;83(2):559–586. [Google Scholar]