Abstract

Many probationers and parolees do not receive HIV testing despite being at increased risk for obtaining and transmitting HIV. A two-group randomized controlled trial was conducted between April, 2011 and May, 2012 at probation/parole offices in Baltimore, Maryland and Providence/Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Male and female probationers/parolees were interviewed (N=1263) and then offered HIV testing based on random assignment to one of two conditions: 1) On-site rapid HIV testing conducted at the probation/parole office; or 2) Referral for rapid HIV testing off site at a community HIV testing clinic. Outcomes were: 1) undergoing HIV testing; and 2) receipt of HIV testing results. Participants were significantly more likely to be tested onsite at a probation/parole office versus off-site at a HIV testing clinic (p < .001). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of receiving HIV testing results. Findings indicate that probationers/ parolees are willing to be tested on-site and, independent of testing location, are equally willing to receive their results. Implications for expanding rapid HIV testing to more criminal justice related locations and populations are discussed.

Keywords: Rapid Testing, Probation, Parole, HIV, HIV Risk Behaviors

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, over five million adults were under community supervision by the criminal justice system in 2009 with approximately four million on probation (1). The current economic crisis and adverse fiscal implications of 30 years of rising incarceration rates has prompted many states to decrease costs by attempting to reduce incarceration and expand the role of community corrections (2). Furthermore, because over 95% of all inmates will ultimately re-enter society (3), the large population under community supervision will likely increase (2). Criminal justice populations are at disproportionately high risk for HIV infection from both injection drug use and unprotected sex (4–7). The estimated prevalence of HIV infection among prisoners in the United States has ranged from over two to five times higher than the general population (8–11). Though reported HIV testing rates in federal (77%) and state (69%) prisons are generally high, testing rates in jails are not (19%) (12). Thus, many HIV-positive individuals under correctional supervision are not offered HIV testing (12). Such testing is crucial because when HIV-infected individuals know their status, they are more likely to both reduce their risk behavior and seek medical treatment, which in turn lowers the potential for HIV transmission while simultaneously reducing the risk of HIV-associated morbidity and mortality (13).

In the US, there are two types of correctional facilities-jails, typically administered by city or county governments holding short-term inmates awaiting trials or serving shorter sentences; and prisons, generally holding long-term inmates serving sentences longer than one year. Community corrections involve both probation and parole, which are alternatives to incarceration. Probation is typically in addition to or in lieu of jail/prison time, and is determined by the court at the time of sentencing, whereas parole is early release from prison and determined by the correctional parole board. Community Corrections entails supervision and monitoring of probationers and parolees. Conditions of parole and probation vary from state to state and offense but often include: reporting to the Parole or Probation Officer (PO) regularly as required, fines, not moving out of state, employment, not possessing firearms, not breaking laws, not associating with former prisoners and mandatory counseling. Conditions of parole include the above and are typically stricter. For instance, the PO maintains closer and more frequent contact with parolee, and monitors employment, housing, and parolee associates. Frequency of contact for both probationers and parolees depends of a number of factors such as offence, prior criminal history, housing and employment stability, and record of compliance. Contact can range from a phone call or message to a prolonged meeting. Often there is a fair amount of waiting in community corrections offices.

Community Corrections Populations are at High Risk for HIV

HIV testing and prevention have largely been ignored among community corrections populations (4–7, 14) with even less attention focused on their HIV risks and behaviors. Though viewed as a lower risk group than prisoners, probationers and parolees are actually at higher risk for HIV transmission than prisoners (4). In a study of Delaware probationers, eight percent were HIV positive, a rate almost four times higher than the comparable rate for Delaware prisoners (14). Compared to jail and prison inmates, probationers and parolees have more opportunities to engage in HIV risk behaviors (6, 14), including unprotected sex (4, 15, 16) and injection drug use (15, 16). HIV risk is also increased with probationers and parolees because of poverty (15), unemployment (15), lack of adequate health care (17), homelessness (15), sharing of drug injection equipment and unsafe sex (15, 18), unprotected sex with multiple, high risk sex partners (19–22), sexually transmitted and other infectious diseases (23), and untreated mental illness (24). Many newly released prisoners resume their preincarceration patterns of drug use and risky sexual behavior upon release (4, 5, 25, 26).

Hypothesis

Because of the need for HIV testing of this high risk population, we hypothesized, that individuals recruited from community corrections will be more likely to undergo rapid HIV testing on site at a probation and parole office rather than off-site in the community. While not specifically involving parolees or probationers, barriers associated with increased travel, lack of transportation, and amount of distance have been found to prevent individuals from receiving HIV testing and care in urban (15) and rural (27) areas of the United States. Furthermore, probationers/parolees are required to fulfill criminal justice related obligations (meeting with PP officer, providing urine drug screen, discussing treatment and employment plans). This may provide a public health opportunity – the convenience of taking care of health concerns, such as rapid HIV testing, at an obligated appointment.

METHODS

Study Design

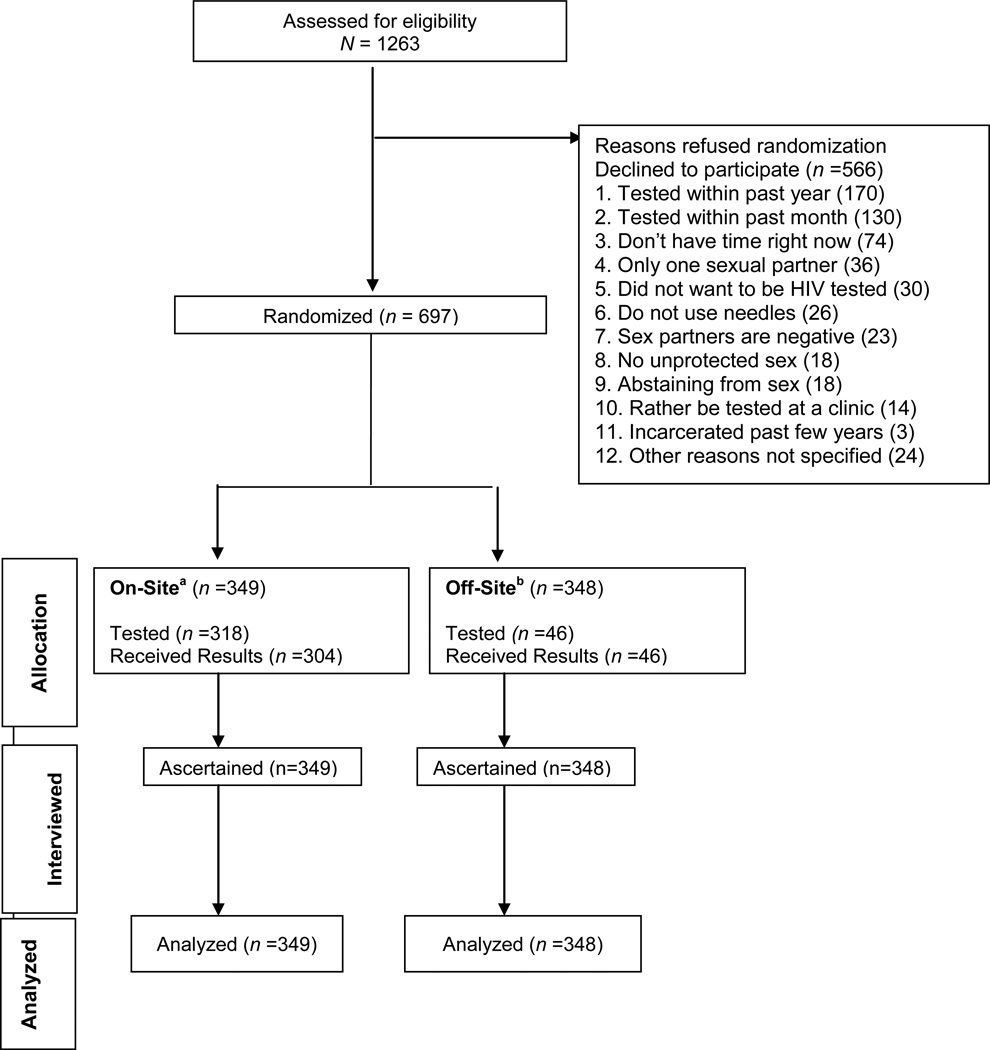

This study is a two-group randomized controlled trial in which male and female probationers and parolees in Baltimore City, Maryland and Providence and Pawtucket, Rhode Island were recruited to complete an assessment then offered optional rapid HIV testing. Those that accepted testing were randomly assigned to one of two treatment conditions [See Figure I. Consort Diagram]: 1) On-site rapid HIV testing conducted by research staff co-located for the purposes of this study at the probation/parole office; or 2) Off-site referral for rapid HIV testing at a community health center or HIV testing clinic. Participants were assigned, within gender, to one of the two treatment conditions, using a random permutation procedure, with an equal chance of being assigned to either condition.

Figure I. Consort Diagram.

a On-Site testing at Probation and Parole Office (31 individuals changed their mind about testing after randomization; 14 individuals did not receive their results because they did not want to wait).

b Off-Site testing at Community HIV clinic.

Human subjects review and confidentiality

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Friends Research Institute and The Miriam Hospital and the trial was monitored by an external Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB). Prisoners are deemed a special population under the Federal Office of Human Research Protection. This research complied with all regulations and was reviewed by an IRB appointed prisoner advocate at both sites. The study investigators obtained a federal Certificate of Confidentiality in order to protect participants from being subpoenaed for the purposes of releasing sensitive information.

HIV rapid testing counselor training

Interviewers were trained in rapid HIV testing and delivering “real” results. In Maryland, interviewers attended a two day training administered by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. In Rhode Island, all staff were trained and certified by the Rhode Island Department of Health as Qualified Professional Test Counselors.

Sites

The two study sites were selected because they have comparatively high populations of adults under correctional supervision and rates of HIV infection. Maryland has over 2,000 probationers per 100,000 residents compared to a national average of 1,873 (28). Rhode Island has over 3,000 probationers per 100,000 adult residents (28). Furthermore, the research centers in Maryland and Rhode Island have forged long standing relationships with their respective state’s Department of Corrections.

Recruitment/Enrollment

Participants were recruited from Baltimore, MD and Providence and Pawtucket, RI between April 18, 2011 and May 1, 2012 from probation and parole offices. Inclusion criteria were: 1) Adult probationer/parolee; and 2) not known to be HIV positive. Individuals unable or unwilling to give informed consent were excluded. Research assistants (RAs) were stationed in the community corrections office during business hours in both the Baltimore and Providence sites, RAs were stationed in the community corrections office during business hours. Posters explaining the study were prominently placed and parole/probation officers (POs) agreed to distribute flyers to probationers and parolees when they met. The RA met with potentially-interested individuals and briefly explained the study to initially assess potential participants’ eligibility and interest in the study. Private offices were available for the potential participant to meet with the RAs. At both sites, recruitment advertisements were displayed in the probation/parole office during the hours that the RAs were not present. The RA emphasized to the potential participant that participation in the study is not mandatory as part of their supervision and that they would not be penalized for not participating.

Testing Conditions

Testing refusal

If the participant refused to be tested, the RA requested that s/he complete a brief, two item questionnaire describing why they refused and provided information regarding community testing sites for future use. Participants received $20 for completing baseline assessments.

On-site rapid HIV testing

Following random assignment to this condition, participants were offered immediate, free rapid oral swab HIV (Oraquick) testing on site. The RA performed the test and provided them with results in approximately 20 minutes. If a participant chose not to wait for results, the RA requested contact information from the participant in order to follow-up in the case of a reactive test result. If the rapid test was positive, participants were counseled, referred directly to a community health center for confirmatory testing and to meet with clinical staff. Participants received $20 for completing baseline assessments.

Off-Site Rapid HIV Testing

All participants received a card with the relevant clinic information and detailed directions to reach the community testing site. For each of the three community off-site testing locations, participants were asked to sign an information release form, which allowed the research team to obtain results from the community referral site. Participants received $20 for completing baseline assessments. At each community clinic staff collected study cards which indicated that the client was a study participant. Study staff and clinic staff maintained regular communications in which the list of participants who completed testing and their results were shared. Baltimore participants were referred primarily to Chase Brexton Health Services (CBHS) Inc., a Federally Qualified Health Center providing medical, psychosocial, and social services on a non-discriminatory basis located approximately 1.6 miles from the Baltimore probation and parole office. In addition, CBHS was quite accessible to public transportation as there is a bus stop that is directly across the street from the clinic. Furthermore, testing days were Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays from 9am–7pm; and Tuesdays and Fridays from 9am–4pm. Providence participants were referred to Community Access - a satellite clinic of The Miriam Hospital that provides drop-in rapid HIV testing Monday through Thursday, 9-noon and 1–5 pm and located 0.6 miles from the Providence probation and parole offices and accessed by multiple bus lines. Pawtucket participants were referred to the Immunology Center at The Miriam Hospital, located 3.4 miles from the Pawtucket probation and parole offices, with direct bus service between community corrections and the Immunology Center. Testing was by appointment on Tuesday and Thursday, 9 am – 4 pm.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were: 1) undergoing HIV testing (yes versus no); and 2) receipt of HIV testing results (yes versus no). Outcome number one was determined by recording if a participant received the rapid oral swab HIV test. Outcome two was recorded if the participant stayed to obtain his/her results on-site and were reported by the clinics for those randomized to off-site testing.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression analysis was used to test our hypotheses, with the two outcome measures: a) undergoing HIV testing (yes v. no) and b) receipt of HIV testing results (yes v. no). The explanatory variables in the model were testing site (on-site v. off-site), and city (Baltimore v. Providence/Pawtucket).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Of the 1263 participants agreeing to provide consent and complete baseline assessments, 697 agreed to be randomized (55.2%). Equal proportions were randomly assigned to on-site and off-site testing. The most common reason for not agreeing to be randomized was because of self-reporting being tested within past year (170; 30%) [See Figure I: Consort Diagram]. The 697 participants had a mean age of 38.7 (SD=11.4); 54.1% were African American, 25.1% were Caucasian, and 20.8% were other ethnicity. About fourteen percent reported Latino/Hispanic as their ethnicity. The sample was predominantly male (81.3%); and 58% never married. Approximately 16% were legitimately employed. Forty-four percent reported having no health insurance; and 14.8% considered themselves homeless. In terms of ever receiving an HIV test, 94.3% reported having received a test, 67.6% reported ever receiving a Hepatitis C (HCV) test; and 49.2% ever receiving a Hepatitis B (HBV) test. In terms of lifetime drug use, 43.3% reported heroin use and 50.8% cocaine use. Of those reporting drug use, 22.4% reported lifetime injection drug use (IDU). Those reporting use of any drugs used on average 11.5 (SD = 22.4) of the past 90 days (See Table I).

Table I.

Community Correction Participant Characteristics by Testing Site

| Total Sample (N=697) |

On-Site (n =349)a |

Off-Site (n=348)b |

Test Statistic |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, m (sd) | 38.7 (11.4) | 39.0 (11.6) | 38.3 (11.1) | .97 | .395 |

| Gender, n (%) | .61 | ||||

| Male | 567 (81.3) | 284 (81.4) | 283 (81.3) | .605 | |

| Female | 130 (18.7) | 65 (18.6) | 65 (18.7) | ||

| Race n (%) | .61 | ||||

| Caucasian | 175 (25.1) | 86 (24.7) | 89 (25.5) | ||

| African American | 377 (54.1) | 184 (52.7) | 193 (55.5) | .489 | |

| Other | 145 (20.8) | 79 (22.6) | 66 (19.0) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino, n (%) | 95 (13.6) | 44 (12.6) | 51 (14.7) | .44 | .438 |

| Marital Status, n (%) | .53 | .525 | |||

| Married/Partner | 145 (20.9) | 73 (20.9) | 72 (20.8) | ||

| Separated/Divorced | 123 (17.7) | 63 (18.1) | 60 (17.3) | .525 | |

| Widowed | 23 (3.3) | 7 (2.0) | 16 (4.6) | ||

| Never Married | 404 (58.1) | 206 (59.0) | 198 (57.2) | ||

| Employed, n (%) | 110 (15.8) | 63 (18.1) | 47 (13.5) | 3.09 | .721 |

| Homeless, n (%) | 103 (14.8) | 53 (15.2) | 50 (14.4) | .05 | .455 |

| Health Insurance n (%) | 388 (55.7) | 199 (57.0) | 189 (54.3) | .36 | .364 |

| Heroin Use, n (%)d | 302 (43.3) | 166 (47.6) | 136 (39.1) | 5.11 | .014 |

| Cocaine Use, n (%)d | 354 (50.8) | 174 (49.8) | 180 (51.7) | .24 | .338 |

| Any Drug Use, m (sd)c | 11.5 (22.4) | 21.0 (34.0) | 14.1 (28.6) | 27.20 | .004 |

| Cocaine Use, m (sd)c | 1.3 (7.1) | .7 (4.2) | 1.9 (9.1) | 9.50 | .122 |

| Heroin Use, m (sd)c | 8.5 (23.2) | 9.2 (24.1) | 7.7 (22.1) | 1.28 | .555 |

| IV Drug use, n (%)d,* | 157 (22.5) | 90 (25.8) | 67 (19.3) | 4.26 | .024 |

| CJ Status, n (%) | 3.29 | .193 | |||

| Probation | 559 (80.2) | 289 (82.8) | 270 (77.6) | . | |

| Parole | 111 (15.9) | 47 (13.5) | 64 (18.4) | ||

| Both | 27 (3.9) | 13 (3.7) | 14 (4.0) | ||

| Crime days, m (sd)c | 4.1 (16.6) | 4.3 (17.1) | 4.0 (16.1) | .12 | .857 |

| Prison/Jail days,m(sd)c, * | 14.7 (27.9) | 12.5 (26.4) | 17.1 (29.2) | 12.41 | .030 |

| Lifetime incarcerations,m(sd)d | 12.7 (64.2) | 11.8 (56.2) | 13.7 (71.3) | .39 | .703 |

| Tested for HIV | 657 (94.3) | 326 (93.4) | 331 (95.1) | 2.28 | .320 |

| Tested for HCV | 471 (67.6) | 231 (66.2) | 240 (68.9) | 1.18 | .555 |

| Tested for HBV | 343 (49.2) | 167 (48.9) | 176 (50.6) | 1.06 | .587 |

| Drug Treatment | 3.5 (11.7) | 3.8 (14.6) | 3.3 (7.7) | .41 | .575 |

| Number people had sex with, m (sd)c | 2.1 (10.2) | 2.3 (12.5) | 1.9 (7.1) | .57 | .690 |

| Times had sex, m (sd) | 31.9 (85.3) | 32.4 (91.6) | 31.4 (78.6 | .00 | .885 |

| Times had sex without a condom, m (sd)c | 26.1 (82.6) | 25.9 (87.3) | 26.3 (77.8) | .06 | .959 |

On-Site (Probation/Parole Office)

Off-site (Community Health Center)

past 90 days

Lifetime

Providence had 2 missing for marital status; χ2 is for categorical variables and F is for count variables.

Note: All variables are self-report measures.

Baseline Differences Between Testing Sites, City, and Not Randomized

We examined differences with respect to baseline characteristics in three ways: 1) testing site comparing on-site vs. off-site (Table I); 2) Baltimore vs. Providence/Pawtucket; and 3) testing site vs. not randomized. Lifetime intravenous drug use (p = .024), days spent in jail/prison during the past 90 days (p = .030), any drug use (p = .004), and lifetime heroin use (p = .014) were the only statistically significant differences by testing site. Those randomized on-site reported a greater proportion of lifetime IDU drug use compared to those tested off-site (26% vs. 19%). In addition, those on-site also reported more mean days of any drug use during the past 90 days (M = 21.0 vs. 14.1) and lifetime heroin use (47.6% vs. 39.1%). However, those randomized off-site reported more mean days of jail/prison during the past 90 days compared to those randomized on-site (M = 12.5 vs. 17.1) [See Table I].

Further examination by city was explored to determine differences between Baltimore and Providence/Pawtucket on a number of baseline characteristics. Baltimore had a higher percentage of African Americans (87.1% vs. 20.7%; p = .0001); were older (M = 40.6 vs. 36.7; p = .001); more likely to be IDU drug users (25.5% vs. 17.5%; p = .017); have more incarceration days during the past 90 days (M = 21.4 vs. 8.1; p = .0001); more crime days in the past 90 days (M = 6.3 vs. 1.9; p = .0001), be on parole (25.3% vs. 3.6%; p<.001); were more likely to have health insurance (63.1% vs. 48.1%; p =.0001); and be homeless (19.1% vs. 10.3%; p = .001). Providence/Pawtucket had a higher percentage of Hispanic/Latino individuals (23.7% vs. 1.7%; p = .0001); reported more days of drug use during the past 90 days (M = 19.9 vs. 15.1); and were more likely to be legitimately employed (20.5% vs. 11.1%; p = .001) [Data not reported in table]. In terms of those randomized versus not randomized, the only difference was those being randomized were more likely to be on parole (16.0% vs. 11%; p =.035) [Data not reported in table].

Primary reasons for refusing randomization

The five primary reasons for individuals refusing randomization were as follows (See Consort Figure I for all reasons): 1) was tested within the past year with negative results (n = 170; 30.0%); 2) was tested within the past month with negative results (n = 130; 23.0%); 3) does not have the time to get HIV tested (n = 74; 13.1%); 4) only has one sexual partner (n = 36; 6.4%); and 5) did not want to be tested for HIV (n = 30; 5.3%).

Primary Outcomes

Undergoing HIV testing

Overall, slightly more than half of the probationers and parolees (55.1%) of enrolled were willing to be randomly assigned for rapid HIV testing either on-site or off-site (Baltimore; n = 350/585; 59.8%; Providence; n = 347/678; 51.2%. Results presented in Table II indicated that participants were significantly more likely to be tested on-site (Baltimore; n =165/174, 94.8 %; Providence/Pawtucket; n = 153/175; 87.4%) at a probation and parole office versus off-site (Baltimore; n = 32/176, 18.2 %; Providence/Pawtucket; n = 14/172; 8.1% Providence; n=9/80; 11.3% and Pawtucket n=5/92; 5.4%) at an HIV testing clinic (Χ2 = 272.47; p< .001) [See Table II]. When controlling for city, there was a difference in terms of being tested off-site as Baltimore participants were more likely to be tested off-site compared to Providence/Pawtucket (Χ2=12.85; p < .001).

Table II.

Results of logistic regression analyses

| Undergoing Rapid HIV Testinga |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Testing Sitec | 272.47 | 80.30 | 47.70, 135.17 | .0001 |

| Cityd | 12.85 | 2.56 | 1.53, 4.28 | .0001 |

|

Receipt of Rapid HIV Testing Resultsb |

||||

| Wald | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Testing Sitec | .00 | .00 | .00, - | .998 |

| Cityd | 3.71 | .28 | .08, .1.0 | .054 |

Overall Model; χ2 = 497.70; df = 2; p = .0001

Overall Model; χ2 = 8.32; d f = 2; p = .016

Reference category is off-site

Reference category is Providence/Pawtucket

Testing Site: On-site (Probation/Parole office); Off-Site (Community Health Center)

City: Baltimore; Providence/Pawtucket

OR= odds ratio.

Receipt of HIV testing results

There was no difference in terms of receiving their rapid results by site Χ2 =.00; p > .05) or by city Χ2 = 3.71; p > .05). Regardless of on-site (Baltimore, 154/165; 93.3%; Providence/Pawtucket, 150/153; 98.0%) or off-site testing (Baltimore, 32/32; 100%; Providence/Pawtucket, 14/14, 100%) almost everyone stayed to receive their rapid results. Furthermore, of those tested, there were two new positives at the Baltimore site. These new positives were immediately referred for confirmatory testing and counseling. Both participants entered community HIV treatment. There were no new positives identified in Providence/Pawtucket.

We did examine covariates in both logistic regression models of undergoing HIV testing (yes versus no) and receipt of HIV testing results (yes versus no) based on post-hoc testing from the significant bivariate analyses variables [See Table 1 for significant variables: heroin use lifetime [any versus none], drug use during the past 90 days [mean days], IV drug use lifetime [ever versus never], and prison/jail during the past 90 days [mean days]. In addition, we included probation/parole status[probation versus parole versus both probation and parole]. The additional covariates were included in the model along with testing site (on-site versus off-site) and city (Baltimore versus Providence/Pawtucket). None of the additional covariates were statistically significant (all ps <.05) in the undergoing HIV testing model [data are not presented in the table]. In the received results model, only Heroin use (lifetime) was statistically significant p = .015) indicating those reporting any lifetime heroin use were twice as likely to not receive their results (85%) compared to those that never reported using heroin (46%). It is difficult to interpret why heroin use lifetime is a significant covariate. However, it could be that heroin users are too busy using and obtaining drugs to deal with other things in their lives. Furthermore, the current variable does not measure frequency of heroin use, which is limited.

DISCUSSION

The results from both Baltimore and Providence/Pawtucket indicate that a majority of probationers and parolees are willing to undergo rapid HIV testing and significantly more likely to undergo HIV testing at a probation/parole office than off-site. Rapid HIV testing programs have been shown to be successful in a number of different settings, including labor and delivery, outpatient clinics, and emergency rooms (29–33). HIV testing in jails is also not a common practice but has been shown to be feasible even though they have low acceptance rates (29, 33).The results were remarkably consistent at two different cities, suggesting that they may be generalizable to other geographic locations. The populations involved in this study were similar demographically to other community corrections populations noted in the literature (15, 2). Given that approximately five million individuals pass through community corrections offices annually in the United States, if other geographic locations show the acceptance rates of testing demonstrated in this study, there appears to be great potential to introduce widespread testing and identification of seropositive individuals in order to link them to care. This could improve not only their own health, and reduce their transmission to others but also identify partners who could be tested and linked to care as well, thus impacting the overall community viral load and HIV transmission rates.

Rapid HIV tests have the advantage of providing immediate results. Non-reactive results can be given to the individual immediately while participants with reactive tests can be provided with immediate linkage and support to obtain confirmatory testing. Our findings are similar to those of Beckwith et al. (29), who offered rapid testing in jail and reported providing all results to inmates (which makes it easier as everyone is confined). Compared with the results of Beckwith and colleagues, the current study is unique in that over 95% received their results (our participants are individuals not currently confined to jail or prison and it is more often difficult for them to receive results as they are in the community and might not want to wait). The reasons for differences in terms of testing off-site by city can not be conclusively determined. However, the proximity and hours of operation likely played a role in accessing off-site testing. The distance between the Immunology Center and Pawtucket community corrections office was the farthest of the three sites. Additionally, the Immunology Center offered less flexible hours for testing. Chase Braxton in Baltimore offered the most flexible schedule for testing, including evening hours. Furthermore, it is possible that in Baltimore, the population of parolees and probationers may be more deviant and prone to criminality than in Providence/Pawtucket. Finally, although this current sample has a high rate of prior testing, it is noteworthy that so many were willing to go undergo testing. Participants were paid whether or not they were tested, as was made clear throughout the consent process. Further, it took at least 20 minutes to conduct the rapid test and receive results. This was in addition to having already visited the probation or parole office and spending 45 minutes to an hour completing the consent process and assessment. Therefore, it seems apparent that they were concerned about their risk.

LIMITATIONS

There are a several limitations to this study. It is possible that some participants may have undergone testing off-site and the results were not captured. However, in all locations, we maintained strong and consistent communication with the staff members of each of the community testing sites. Additionally, more probationers/parolees passed through the community corrections offices in which we worked than were approached by research staff. This introduced the possibility of selection bias. In addition, we offered $20 for interviews only and not testing, so this may have increased the likelihood of testing, although they were not paid for testing. Although probationers and parolees were randomly assigned to corrections office vs. community testing, the overall sample may or may not be representative of the overall community corrections population. Despite these limitations, the study provides evidence that it is feasible to test on-site at community corrections, and that it is preferable to referral to off-site testing.

CONCLUSION

Much has been written about the benefits of HIV testing and linkage to care in prison and jail settings (4, 6, 7, 29). This is the first study to suggest that those benefits could be extended to the community corrections setting. The results from this study suggest that it might be feasible to extend HIV testing to Drug Courts, Day Reporting Centers, and other Community Correction venues. There has been concern that individuals reporting to the probation/parole office may not be in the right frame of mind to undergo testing, and might be too concerned about confidentiality; however, we have shown that in spite of that, individuals currently under community corrections supervision will get tested. Finally, rapid HIV testing is inexpensive and convenient for individuals under community corrections supervision, and parolees and probationers are at greater risk than the general population and even prison and jail inmates. Furthermore, it should be noted that in areas where HIV infection is less prevalent than in Baltimore and Rhode Island, testing in parole/probation offices may not be as relevant to criminal justice administrators and partnering with a community health center for testing might be more relevant. Therefore, the current study may have some implications for implementation science research as it is taking an evidence-based practice (rapid HIV testing) and moving it to greater access and convenience to a relatively high-risk population by two important strategies: 1) implementing rapid testing on site at criminal justice sites as mentioned above; and 2) collaborating with HIV care organizations in the community. Furthermore, by implementing rapid testing within criminal justice agencies it could provide the opportunity for further training for probation and parole staff on HIV and risk related behaviors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Grant R01 DA 16237 (Principal Investigators: Michael S. Gordon, D.P.A, Josiah D. Rich, M.D.). This work was also supported by grants R01DA030771 and K24DA022112 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and P30AI042853 from the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We wish to thank NIDA staff, Drs. Redonna K. Chandler, Shoshana, Kahanna, and Dionne Jones. The authors are also grateful for the strong and continued support of the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services and the Rhode Island Division of Corrections (Probation and Parole). We would also like to thank the staff of the off-site community clinics-- Chase Brexton Health Services, Community Access - a satellite clinic of The Miriam Hospital, and the Immunology Center at The Miriam Hospital. Finally, we appreciate the contributions of the Project staff as well as those of Ms. Melissa Irwin for manuscript preparation and assistance with submission.

References

- 1.West HC, Sabol WJ, Greenman SJ. Prisoners in 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2010. (Publication No. NCJ 23167) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmalleger F. Criminal Justice Today: An Introductory Text for the 21st Century. 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersilia J. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belenko S, Langley S, Crimmins S, Chaple M. HIV risk behaviors, knowledge, and prevention education among offenders under community supervision: a hidden risk group. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(4):367–385. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.367.40394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra A, Billioux VG, Copen CE, Sionean C. National Health Statistics Reports. No. 46. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. HIV risk-related behaviors in the United States household population aged 15–44 years: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 2002 and 2006–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leukefeld CG, Hiller ML, Webster JM, et al. A prospective examination of high-cost health services utilization among drug using prisoners reentering the community. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33(1):73–85. doi: 10.1007/s11414-005-9006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oser CB, Smiley HM, Havens JR, Leukefeld CG, Webster JM, Cosentino-Boehm AL. Lack of HIV seropositivity among a group of rural probationers: explanatory factors. J Rural Health. 2006;22(3):273–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruschak LM, Sabol WJ, Potter RH, Reid LC, Cramer EW. Pandemic influenza and jail facilities and populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S339–S344. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.175174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruschak L. HIV in Prisons: 2000: Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs [NCJ 196023] 2002 Oct

- 10.Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among men released from state prison, 1980–2005. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(12):2278–2284. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA, White BL, Stewart PW, Golin CE. Characteristics and behaviors associated with HIV infection among inmates in the North Carolina prison system. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1123–1130. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed March 24, 2010];HIV Testing Implementation Guidance for Correctional Settings. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/testing/resources/guidelines/correctional-settings. Published January 30, 2009.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed March 24, 2010];HIV Prevention Strategic Plan: Extended Through 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/reports/psp/. Published December 28, 2007.

- 14.Martin SS, O'Connell DJ, Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Beard RA. HIV/AIDS among probationers: an assessment of risk and results from a brief intervention. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:435–443. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inciardi JA. The War on Drugs IV. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inciardi JA, McBride D, Suratt H. In: The heroin street addict: Profiling a national population. Inciardi JA, Harrison L, editors. Heroin in the Age of Crack Cocaine Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1789–1794. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum M. Women: Research and policy, Part I. In: Alliance DP, editor. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Third ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braithwaite RL, Stephens TT, Treadwell HM, Braithwaite K, Conerly R. Short-term impact of an HIV risk reduction intervention for soon-to-be released inmates in Georgia. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4 Suppl B):130–139. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke JG, Stein MD, Hanna L, Sobota M, Rich JD. Active and former injection drug users report of HIV risk behaviors during periods of incarceration. Subst Abus. 2001;22(4):209–216. doi: 10.1080/08897070109511463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Tuthill RW. Self-reported health and prior health behaviors of newly admitted correctional inmates. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1939–1941. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margolis AD, MacGowan RJ, Grinstead O, Sosman J, Kashif I, Flanigan TP. Unprotected sex with multiple partners: implications for HIV prevention among young men with a history of incarceration. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):175–180. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187232.49111.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Maruschak LM. 1996–1997 update: HIV/AIDS, STDs, and TB in correctional facilities. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whetten K, Reif SS, Napravnik S, et al. Substance abuse and symptoms of mental illness among HIV-positive persons in the Southeast. South Med J. 2005;98(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000149371.37294.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seal DW, Eldrige GD, Kacanek D, Binson D, Macgowan RJ Project Start Study Group. A longitudinal, qualitative analysis of the context of substance use and sexual behavior among 18- to 29-year-old men after their release from prison. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(11):2394–2406. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, McKaig R, et al. Sexual behaviours of HIV-seropositive men and women following release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(2):103–108. doi: 10.1258/095646206775455775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutton M, Anthony MN, Vila C, McLellan-Lemal E, Weidle PJ. HIV testing and HIV/AIDS treatment services in rural counties in 10 southern states: service provider perspectives. J Rural Health. 2010;26(3):240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaze LE, Bonzcar TP. Probation and Parole in the U.S. 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beckwith CG, Atunah-Jay S, Cohen J, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of rapid HIV testing in jail. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(1):41–47. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulterys M, Jamieson DJ, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Rapid HIV-1 testing during labor: a multicenter study. JAMA. 2004;292(2):219–223. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Couturier E, Schwoebel V, Michon C, et al. Determinants of delayed diagnosis of HIV infection in France, 1993–1995. AIDS. 1998;12(7):795–800. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forsyth BW, Barringer SR, Walls TA, et al. Rapid HIV testing of women in labor: too long a delay. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(2):151–154. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200402010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kendrick SR, Kroc KA, Couture E, Weinstein RA. Comparison of point-of-care rapid HIV testing in three clinical venues. AIDS. 2004;18(16):2208–2210. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]