Abstract

Objective

To determine factors associated with parental consent for their child’s participation in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

7 Children’s Hospitals participating in a randomized trial evaluating management of children with vesicoureteral reflux; July 2008 to May 2011.

Participants

Parents asked to provide consent for their child’s participation in the trial were invited to complete an anonymous online survey about factors influencing their decision. 120 (44%) of the 271 invited, completed the survey: 58 of 125 (46%) had provided and 62 of 144 (43%) had declined consent.

Outcome Measures

60-question survey examining: child, parent, and study characteristics; parental perception of the study; understanding of design; external influences; and decision-making process.

Results

Having graduated from college and private health insurance were associated with lower likelihood of providing consent. Parents who perceived the trial as having low degree of risk, resulting in greater benefit to their child and other children, causing little interference with standard care or exhibiting potential for enhanced care or who perceived the researcher as professional were significantly more likely to consent to participate. Higher levels of understanding of randomization process, blinding, and right to withdraw were significantly associated with consent to participate.

Conclusions

Parents who declined consent had a relatively higher socioeconomic status, had more anxiety about their decision and found it harder to make their decision compared with consenting parents, who had higher levels of trust and altruism, perceived the potential for enhanced care, reflected better understanding of randomization, and exhibited low decisional uncertainty.

Keywords: Consent, randomized clinical trials, participation in pediatric clinical research

INTRODUCTION

Research to date of factors influencing a parent’s decision to provide consent for his or her child to participate in clinical research has been limited to cancer studies and less-than- minimal risk studies. Further, most investigators have collected data only from parents who consented to their child’s involvement;1,2 very few have examined the motives of parents who declined consent.3–5 The aggregate of reported findings suggests that the health of the child, positive perceptions of the research team and consent process, and altruistic motives play a significant role in the decision-making process.

To evaluate decision-making among parents invited to enroll their child in a randomized controlled trial of antimicrobial prophylaxis for vesicoureteral reflux, we developed and administered a survey assessing the role of factors previously reported to influence parental decision making. Our objective was to determine factors associated with parents’ decisions to permit their child to participate or not participate in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial and, accordingly, identify strategies to enhance enrollment in pediatric clinical research.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Parents who were asked to provide consent for their child’s participation in a randomized trial evaluating the management of children with vesicoureteral reflux (Randomized Intervention for Children with VesicoUreteral Reflux, RIVUR, U01DK074053) were eligible to participate in the consent survey. RIVUR is a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of long-term (24 months) antimicrobial prophylaxis in preventing recurrent urinary tract infections and the occurrence of renal scarring in children ages 2 months to 6 years old. Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating institutions (Children’s Hospitals of Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Buffalo, and Chicago; Johns Hopkins University; Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children; and Children’s National Medical Center) determined this survey study to be exempt under 45 CFR 46.101(b)(2); investigators were required to read to parents an IRB-approved script that contained basic elements of informed consent describing the anonymous survey, but no formal written consent was obtained.

The RIVUR study was thoroughly discussed with parents of eligible children over the phone or in person by an investigator, after which consent for their child participation was sought. Regardless of whether they did or did not agree to their child’s participation, parents were asked for permission to e-mail them a link to the survey. Parents were informed the anonymous survey would take approximately 15 minutes to complete and involved questions about age, race, education, family background, and their perceptions about medical research; they were also informed that upon completing the survey, they would receive a $10 gift certificate to an online bookstore retailer in appreciation for their time. At one RIVUR study site (Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh), parents who did not complete the survey within 2 months of being sent the link to the online survey were reminded once; no other sites sent out the link in a second wave, and no further reminders were sent to parents in Pittsburgh.

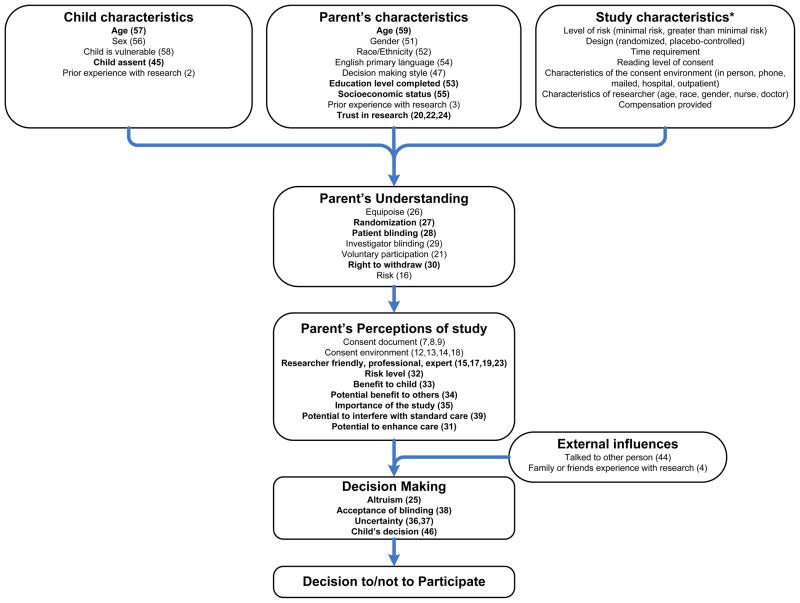

The framework of our 60-question survey to assess factors influencing parental decisions to participate in clinical research was informed by the conceptual model (Figure 1) we developed based on prior studies.3 Parent, child, and study characteristics influence how well parents understand the trial design issues, such as equipoise, randomization, blinding, voluntary participation, and right to withdraw. This understanding, in turn, influences parental perceptions regarding the risks and benefits of the trial. The decision to allow participation is also influenced by parent decision-making style and by external influences. We were interested in learning how factors in each stage of the decision-making process influenced the final decision to provide or withhold consent. Altogether, we sought to examine 7 constructs governing the decision to provide consent: child characteristics, parent characteristics, study characteristics, parental perception of the study, parental understanding of study design, external influences, and the decision-making process.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model (parenthetical numbers correspond with survey question numbers in the Supplemental Information

Survey questions included all those proposed by Tait et al.,3 though we modified the wording of some questions and added 7 questions assessing parental understanding of the trial. Study characteristics include the level of risk involved, study design, time requirement, and characteristics of the consent environment and the researcher. Because we were only assessing participation in a single trial (RIVUR), we did not investigate the influence of study characteristics on the decision-making process. Child characteristics included age, sex, and whether the child was perceived by the parent to be sicker than other children (vulnerable), whether the child provided assent, and whether the child had previously participated in research. Relevant parent characteristics include demographics (age, sex, ethnicity, race), socioeconomic status (education, health insurance), sense of altruism, research experience (previous participation, trust), and style of decision-making.

Responses to most items were scored using a 5-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree); some items were scored on 0–10 visual analog scales (10 = high). A complete copy of the survey and response data can be found in the Supplemental Information.

Faculty and staff from the University of Pittsburgh Clinical Translational Science Institute Design, Biostatistics and Clinical Research Ethics Core, who were not involved in the RIVUR study, were responsible for maintaining the anonymity of survey respondents, implemented the survey, and analyzed the data. Web security met the University of Pittsburgh standards of confidentiality.

Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to describe all variables, comparing survey data from parents who consented to enroll their child in the RIVUR study with those who declined consent. To determine which factors were significantly associated with the decision to enroll their child in the RIVUR study, we used univariate analyses: Mann-Whitney test for comparing continuous variables, and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Small cell size for some dichotomous variables precluded multivariable logistic regression analysis. We tested each construct for internal reliability using Cronbach alpha; in all cases, values obtained were >0.7, suggesting good internal reliability. All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participants in the RIVUR study were enrolled at 19 participating institutions between May 2006 and May 2011; the survey study (an ancillary study to RIVUR) was conducted at only 7 of the 19 RIVUR participating institutions between July 2008 and May 2011. A total of 271 parents who had been contacted for consent to participate in the RIVUR study at one of these 7 sites were e-mailed codes to participate in the online consent survey during the survey study period. Of the 271 parents who were e-mailed codes for the online consent survey, 120 (44%) completed the survey (84% from the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh site): 58 of 125 (46%) parents who provided consent and 62 of 144 (43%) parents who declined consent for their child to participate; the consent status of two participants was unknown. The 271 parents who were e-mailed the consent survey at the 7 sites during the 3-year period represent 21% of the approximately 1300 parents approached for their child’s participation at the 19 RIVUR sites during the 5-year period. The 58 parents who consented and filled the survey at the 7 sites during the 3-year period represent approximately 10% of the 607 children enrolled at the 19 RIVUR sites during the 5-year period.

Parent and child demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Children whose parents consented to their participation in the RIVUR trial were slightly older than those of non-consenters; parents who consented were younger than non-consenters. Because vesicoureteral reflux is three times more common in whites than blacks, the low minority representation is expected.6 Having graduated from college and having private health insurance -- both proxies for higher socioeconomic status -- were associated with a lower likelihood of consenting to their child’s participation in the RIVUR study.

Table 1.

Parent and child demographic characteristics

| Non-consenters N=62 | Consenters N=58 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child’s age (yr) – Median (Min, Max) | 1.00 (0, 5) | 1.50 (0, 7) | 0.048 |

| Parent’s age (yr) – Median (Min, Max) | 33.00 (20, 43) | 31.00 (22, 46) | 0.017 |

|

Number (%)

|

|||

| Child’s sex | |||

| Male | 3 (4.8) | 3 (5.2) | 1.0 |

| Female | 59 (95.2) | 55 (94.8) | |

| Parent relationship to child | |||

| Mother | 58 (93.5) | 52 (89.7) | 0.520 |

| Father | 4 (6.5) | 6 (10.3) | |

| Hispanic | |||

| Yes | 2 (3.2) | 3 (5.2) | 0.672 |

| No | 60 (96.8) | 55 (94.8) | |

| Race | |||

| American Indian | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 1.0 |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Black or African American | 1 (1.6) | 3 (5.2) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| White | 60 (98.4) | 57 (98.3) | |

| Preferred not to answer | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Level of education | |||

| ≤ High school or GED or some college/technical | 7 (11.3) | 29 (50) | <0.001 |

| ≥ College graduate | 55 (88.7) | 29 (50) | |

| Health insurance status | |||

| Private | 56 (90.3) | 36 (62.1) | <0.001 |

| Public | 6 (9.7) | 21 (36.2) | |

| None | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | |

| English as first language | |||

| Yes | 60 (96.8) | 57 (98.3) | 1.0 |

| No | 2 (3.2) | 1 (1.7) | |

| If no, was language a problem for you to understand the study? | |||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 2 | 1 | |

Number indicate survey question;

Influence of benefit to other children on decision to participate;

Chi square, Fisher’s exact test, or Mann-Whitney

Coding was reversed for items 14, 18, 29 and 39 for analysis and presentation of results

In comparison, the RIVUR cohort of 607 children had a similar median age (1 year, range 0.2 – 5.9) and similar proportions of parents who were at least college graduates (48%) or had public health insurance (29%) as the non-consenter survey study group. Compared with each of the two survey study groups (consenters and non-consenters), the RIVUR cohort was similarly composed of female subjects (92%), had a lower proportion of white race subjects (81%), and a higher proportion of subjects with Hispanic ethnicity (13%).

Table 2 summarizes factors that influence the decision to provide consent. Parents were significantly more likely to consent to participate if they perceived the researcher as being friendly and professional and/or the RIVUR study as having a low degree of risk; resulting in a greater benefit to their child and other children (higher altruism); causing little interference with standard care; and/or exhibiting a greater potential for enhanced care. External influences (discussing research with others, previous family or friends’ experience with research) appeared not to influence consent to participate. Higher levels of parental understanding of the randomization process, blinding, right to withdraw, and degree of risk were also significantly associated with consent to participate; paradoxically, the higher educated non-consenters displayed significantly lower understanding of study randomization and blinding. We found a relatively low agreement (kappa 0.2) between parental understanding of randomization and the perception that by participating in the study their child will receive best medical care (therapeutic misconception).

Table 2.

Factors influencing parents’ decision to participate in clinical research

| Non-consenters N=62 | Consenters N=58 | P value§ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent/child characteristics |

Number (%)

|

||

| Child too young to express opinion (45)* | 58 (93.5) | 55 (94.8) | 1.00 |

| Child vulnerable (58) | 3 (4.8) | 6 (10.3) | 0.312 |

| Decision making style (47) | |||

| Self/family | 31 (50) | 32 (55) | 0.571 |

| Shared with MD | 31 (50) | 26 (45) | |

|

Mean score (SD)

|

|||

| Trust in research (20,22,24) - Total score (3–15) | 11.26 (1.88) | 12.83 (1.55) | <0.001 |

| External influences |

Number (%)

|

||

| Talked to other person (44a) | 59 (95.2) | 52 (89.7) | 0.312 |

| This person helped a lot to make your decision (44b) | 40 (67.8) | 33 (63.5) | 0.236 |

| Family or friends who participated in research (4) | 19 (30.6) | 14 (24.1) | 0.425 |

| Parent’s understanding - Total score (1–5) |

Mean score (SD)

|

||

| Equipoise (26) | 3.71 (0.80) | 3.88 (0.73) | 0.338 |

| Randomization (27) | 3.98 (0.76) | 4.38 (0.62) | 0.004 |

| Patient Blinding (28) | 3.94 (0.85) | 4.4 (0.82) | 0.001 |

| Investigators blinding (29†) | 2.90 (1.11) | 3.28 (1.40) | 0.090 |

| Voluntary participation (21) | 4.45 (0.67) | 4.60 (0.53) | 0.196 |

| Right to withdraw (30) | 3.87 (0.74) | 4.48 (0.71) | <0.001 |

| Risk level of the study (16) | 4.05 (0.69) | 4.29 (0.75) | 0.020 |

| Parent’s perceptions | |||

| Consent document characteristics (7,8,9) - Total score (3–15) | 13.2 (1.86) | 12.3 (2.80) | 0.304 |

| Consent environment (12,13,14†,18†) - Total score (4–20) | 16.44 (2.63) | 17.00 (2.64) | 0.188 |

| Researcher characteristics (15, 17, 19, 23) - Total score (4–20) | 17.33 (1.89) | 18.33 (1.90) | 0.003 |

| Risk of the study (32) – Total score (0–10) | 6.05 (2.28) | 3.14 (1.75) | <0.001 |

| Benefit to my child (33) – Total score (0–10) | 3.65 (2.10) | 7.31 (1.98) | <0.001 |

| Benefit to others (34) – Total score (0–10) | 6.48 (2.35) | 8.48 (1.49) | <0.001 |

| Importance of study (35) – Total score (0–10) | 6.77 (1.96) | 9.05 (1.18) | <0.001 |

| Study may interfere with standard care (39†) – Total score (0–10) | 5.27 (3.45) | 2.72 (2.78) | <0.001 |

| Study may enhance standard care (31) – Total score (1–5) | 2.50 (0.90) | 4.36 (0.72) | <0.001 |

| Decision making | |||

| Altruism† (25) – Total score (1–5) | 2.73 (0.81) | 4.10 (0.74) | <0.001 |

| Acceptance of blinding (38) – Total score (0–10) | 7.68 (2.94) | 5.19 (2.89) | <0.001 |

| Uncertainty (36,37) – Total score (0–20) | 13.32 (4.31) | 9.88 (5.62) | <0.001 |

Number indicate survey question;

Influence of benefit to other children on decision to participate;

Chi square, Fisher’s exact test, or Mann-Whitney

Coding was reversed for items 14, 18, 29 and 39 for analysis and presentation of results

Parents who had little decisional uncertainty (low levels of anxiety) were more likely to consent to their child’s participation in the RIVUR study. Conversely, parents who declined participation in the RIVUR study reported higher levels of anxiety and more difficulty making the decision.

DISCUSSION

We found that parents who declined consent to their child’s participation in the RIVUR trial had a relatively higher socioeconomic status, had more anxiety about their decision and found it harder to make a decision about the study compared with consenting parents, who exhibited higher levels of trust, altruism and low decisional uncertainty, perceived the potential for enhanced care, and reflected better understanding of randomization.

The impact of socioeconomic status on research participation has varied. A higher level of education resulted in higher research participation in HIV and cancer adult studies.7,8 In contrast, in a randomized pediatric oncology study, parents with a higher socioeconomic status were more likely to refuse participation,9 and parents with a bachelor’s degree or higher were less likely to endorse research in an emergency setting than were parents with less than a bachelor’s degree.10 In our study, better-educated non-consenters may have felt a need to explain why they did not consent to the RIVUR trial, thus making them more likely to participate in this survey. It is also possible that non-consenters with lower levels of education were more likely to ignore the request to participate in survey. Accordingly, caution should be applied when considering the influence of education on the consent decision based on these data. In general, our findings may also be limited because we solicited participation at just 7 of 19 study sites for only 3 of the 5 years during which the RIVUR study was open for enrollment, and even among this selected sample, less than 50% of parents who were invited completed the survey.

Previous reports have noted the significant influence of the child’s health on parental decisions to provide consent.11–13 A strength of our study is that we surveyed consenting and non-consenting parents whose children were otherwise healthy, apart from vesicoureteral reflux, and who were approached for participation in an actual rather than hypothetical clinical trial.12,14

Three prior studies compared the motivations of consenting and non-consenting parents. Tait et al.3 identified low perceived risk, degree to which the parent read the consent document, characteristics of the consent document, parental understanding, perceived importance of the study, and perceived benefits as predictors of providing consent. In a British study4 of oral versus intravenous treatment for community-acquired pneumonia in previously well children, altruism was the major motivation for parental consent; parents who declined consent were unwilling to undergo randomization as they believed one treatment arm (intravenous treatment) was superior, suggesting lack of understanding about clinical trial design (equipoise). Harth et al.5 reported that the psychological profile of volunteering parents differed from that of non-volunteering parents in the context of a randomized trial of an asthma drug. Volunteering parents valued benevolence, were more introverted, had lower self-esteem, and exhibited greater anxiety than non-volunteering parents, who tended to have higher levels of education, hold professional/administrative jobs, and exhibit greater social confidence and emotional stability. Our parents in both categories did not differ in how they assessed equipoise (“Doctors do not really know which of the two treatments is better”) and voluntary participation (“I felt like the decision to have my child take part in the study was up to me”). In contrast, responses that reflected understanding of study design issues – randomization, blinding, risk level, right to withdraw (e.g., “My child has an equal chance of getting either treatment”), altruism, and potential benefit to others were significantly higher among consenters (Table 2).

In studies conducted only among parents who had provided consent, factors influencing this decision included altruistic motivation15,16 and a desire to learn more about their child’s disease.1 In one study, the availability of a financial stipend or the parent’s educational level were not felt to influence the consent decision, although obtaining free medication became more important as socioeconomic status declined.1 Among educated “research-naïve” parents who had consented to their child’s participation in placebo-controlled gastrointestinal trials, motivation for consent derived from altruism and the setting and manner in which consent had been sought; perceived risks (adverse effects, receipt of placebo) and financial incentives did not play a significant role.2

Finally, in agreement with previous reports,2,3,16 we found that positive parental perception of the researcher was associated with greater likelihood to consent. Specifically, parents were asked if the “person who presented the study” was friendly, was professional, made them feel comfortable, and “did a good job explaining the study.” These researcher characteristics could have contributed to the consenting parents’ greater understanding of and comfort with the clinical trial and its potential to benefit other children. Perez et al.2 note that comfort with the research team was high among all parents who enrolled their children in a placebo-controlled trial but was lower among parents whose children did not complete the study, emphasizing the importance of this initial encounter.

CONCLUSION

Findings from our survey may be used to improve participation in pediatric clinical research. Among our families, important modifiable factors that influenced the consent process included the involvement of a researcher who made them feel comfortable and proper understanding of the study (i.e., low risk, lack of interference with standard of care, and better understanding of randomization and blinding). Our findings emphasize the importance of clearly explaining how risk is minimized, how participation affects standard of care, blinding and randomization, the right to withdraw at any time, and the benefits (if any) to the child and other children. Our finding of high level of decisional anxiety among the more educated and higher socioeconomic status parents provides an opportunity to acknowledge, empathize, and support parents who may struggle with the decision. Careful consideration of the various factors included in the conceptual model should enhance the quality of the informed consent process and improve participation in pediatric clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR024153, and UL1TR000005 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The Randomized Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux trial was supported by cooperative agreements U01 DK074059 (Carpenter), U01 DK074053 (Hoberman), U01 DK074082 (Mathews), U01 DK074064 (Keren), U01 DK074062 (Mattoo), U01 DK074063 (Greenfield) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. The trial was also supported by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR000003) from the National Center for Research Resources, now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. The RIVUR website is located at http://www.cscc.unc.edu/rivur/.

Abbreviations

- RIVUR

Randomized Intervention for children with VesicoUreteral Reflux

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Contributor’s Statement Page

Alejandro Hoberman: Dr. Hoberman conceptualized and designed the study including the data collection instrument, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Nader Shaikh: Dr. Shaikh conceptualized and designed the study including the data collection instrument, critically reviewed the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Sonika Bhatnagar: Dr. Bhatnagar helped design the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Mary Ann Haralam: Ms. Haralam helped design the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Diana H. Kearney: Ms. Kearney helped design the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

D. Kathleen Colborn: Ms Colborn helped design the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Michelle L. Kienholz: Ms. Kienholz helped design the data collection instrument, conducted an extensive literature review, drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Li Wang: Ms. Wang helped design the data collection instrument, conducted all statistical analyses, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Clareann H. Bunker: Dr. Bunker helped design the data collection instrument, conducted all statistical analyses, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ron Keren: Dr. Keren reviewed the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Myra A. Carpenter: Dr. Carpenter reviewed the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Saul P. Greenfield: Dr. Greenfield reviewed the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Hans G. Pohl: Dr. Pohl reviewed the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ranjiv Mathews: Dr. Mathews reviewed the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Marva Moxey-Mims: Dr. Moxey-Mims reviewed the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Russell W. Chesney: Dr. Chesney reviewed the data collection instrument, assisted in gathering data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Contributor Information

Nader Shaikh, Email: nader.shaikh@chp.edu.

Sonika Bhatnagar, Email: sonika.bhatnagar@chp.edu.

Mary Ann Haralam, Email: haralamm@upmc.edu.

Diana H. Kearney, Email: diana.kearney@chp.edu.

D. Kathleen Colborn, Email: kathleen.colborn@chp.edu.

Michelle L. Kienholz, Email: mlk39@pitt.edu.

Li Wang, Email: liw29@pitt.edu.

Clareann H. Bunker, Email: bunkerc@pitt.edu.

Ron Keren, Email: keren@email.chop.edu.

Myra A. Carpenter, Email: myra_carpenter@unc.edu.

Saul P. Greenfield, Email: sgreenfield@kaleidahealth.org.

Hans G. Pohl, Email: hpohl@cnmc.org.

Ranjiv Mathews, Email: rmathew1@jhmi.edu.

Marva Moxey-Mims, Email: mm726k@nih.gov.

Russell W. Chesney, Email: rchesney@uthsc.edu.

References

- 1.Rothmier JD, Lasley MV, Shapiro GG. Factors influencing parental consent in pediatric clinical research. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1037–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez ME, Langseder A, Lazar E, Youssef NN. Parental perceptions of research after completion of placebo-controlled trials in pediatric gastroenterology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:309–13. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181cea4f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Participation of children in clinical research: factors that influence a parent's decision to consent. Anesthesiol. 2003;99:819–25. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sammons HM, Atkinson M, Choonara I, Stephenson T. What motivates British parents to consent for research? A questionnaire study. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harth SC, Johnstone RR, Thong YH. The psychological profile of parents who volunteer their children for clinical research: a controlled study. J Med Ethics. 1992;18:86–93. doi: 10.1136/jme.18.2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chand DH, Rhoades T, Poe SA, Kraus S, Strife CF. Incidence and severity of vesicoureteral reflux in children related to age, gender, race and diagnosis. J Urol. 2003;170:1548–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000084299.55552.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gifford AL, Cunningham WE, Heslin KC, et al. Participation in research and access to experimental treatments by HIV-infected patients. N Eng J Med. 2002;346:1373– 82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2109–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiley FM, Ruccione K, Moore IM, et al. Parents' perceptions of randomization in pediatric clinical trials. Children Cancer Group. Cancer Pract. 1999;7:248–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.75010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris MC, Besner D, Vazquez H, Nelson RM, Fischbach RL. Parental opinions about clinical research. J Pediatr. 2007;151:532–7. 7, e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher HR, McKevitt C, Boaz A. Why do parents enroll their children in research: a narrative synthesis. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:544–51. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.040220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell PH, Hamilton S, Tan A, Craig JC. Strategies for increasing recruitment to randomised controlled trials: systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldwell PH, Butow PN, Craig JC. Parents' attitudes to children's participation in randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr. 2003;142:554–9. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wendler D, Jenkins T. Children's and their parents' views on facing research risks for the benefit of others. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:9–14. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snethen JA, Broome ME, Knafl K, Deatrick JA, Angst DB. Family patterns of decision-making in pediatric clinical trials. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:223–32. doi: 10.1002/nur.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodgate RL, Yanofsky RA. Parents' experiences in decision making with childhood cancer clinical trials. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:11–8. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b43389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]