Abstract

Purpose

Among children diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and given chemotherapy-only treatment, 40-70% of survivors experience neurocognitive impairment. The present study used a preclinical mouse model to investigate the effects of early exposure to common ALL chemotherapeutics methotrexate (MTX) and cytarabine (Ara-C) on learning and memory.

Experimental Design

Pre-weanling mouse pups were treated on postnatal day (PND) 14, 15, and 16 with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a combination of MTX and Ara-C. Nineteen days following treatment (PND 35), behavioral tasks measuring different aspects of learning and memory were administered.

Results

Significant impairment in acquisition and retention over both short (1h) and long (24h) intervals, as measured by autoshaping and novel object recognition tasks, were found following treatment with MTX and Ara-C. Similarly, a novel conditional discrimination task revealed impairment in acquisition for chemotherapy-treated mice. No significant group differences were found following the extensive training component of this task, with impairment following the rapid training component occurring only for the highest MTX and Ara-C combination group.

Conclusions

Findings are consistent with clinical studies suggesting that childhood cancer survivors are slower at learning new information and primarily exhibit deficits in memory years after successful completion of chemotherapy treatment. The occurrence of mild deficits on a novel conditional discrimination task suggests that chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment may be ameliorated through extensive training or practice.

Keywords: Childhood chemotherapy, Learning, Mice, Cognitive late effects, Cognitive remediation

Introduction

Advancements in treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common form of cancer in children and adolescents, have led to a remission rate of more than 90% among patients (1). Furthermore, the substitution of intrathecal chemotherapy for cranial irradiation has reduced adverse late effects resulting from treatment (2,3). However, 40-70% of childhood cancer survivors given chemotherapy-only treatment will experience neurocognitive deficits years later, including impairments in attention, working memory, and processing speed (4-6).

Preclinical models have been used to directly test the effects of chemotherapeutic agents on learning and memory (7 for review). The vast majority of these studies have focused on treatment of adolescent or adult rodents, while a few have assessed the long-term impact of pre-weanling treatment at PND 15 (8) or PND 17 (9-12). As models using adult rodents are not adequate for studying the emergent effects of childhood chemotherapy treatment, additional examination of long-term impairment following early exposure to chemotherapeutics is warranted. Of the chemotherapeutic agents used in ALL treatment, methotrexate (MTX) remains the most studied due to its known neurotoxic effects, which include anti-folate disruption of DNA synthesis, reduction of hippocampal cell proliferation and blood vessel density, as well as degeneration of white matter and white matter necrosis (13-16). Following treatment with MTX alone, behavioral disruptions have been noted on tasks of learning and memory (8,10,15,17 but see 18).

MTX is commonly administered with cytarabine (Ara-C) during intrathecal chemotherapy for ALL. In cell culture, Ara-C alone produces death of oligodendrocytes and glial-restricted precursor cells (19). In vivo, Ara-C alone disrupts cell division in mice (19), and induces retraction of the apical dendrites of the anterior cingulate cortex in rats (20). There are also reports of memory loss and white-matter changes in patients following treatment with Ara-C (21), and evidence in rodents for long-term spatial memory impairment has been found (20). Although MTX and Ara-C are commonly administered simultaneously or sequentially due to their synergistic effects on cancer cells (22), the impact of this combination treatment on cognitive impairment has not been examined.

The present study tested male and female mice using three assays of learning and memory: an autoshaping procedure, a novel object recognition task, and a novel conditional discrimination task. The autoshaping procedure provides a rapid and objective measure of whether a drug affects acquisition or retention of a learned response (23,24). The novel object recognition task involves the spontaneous exploration of objects, and is based on the well-documented fact that rodents tend to explore novel stimuli more than familiar ones. This one-trial learning paradigm uses delay-dependent behavior to model memory in a rodent (25). Conditional discrimination involves the use of conditional information to inform goal-directed performance (26). Choice of one of the simultaneously present stimuli is reinforced only when one of the additional conditional stimuli is present, whereas choice of the other simultaneous stimulus is reinforced only when the second conditional stimulus is present (27). The current procedure used a conditional temporal discrimination, in which response accuracy was contingent on either a short or long stimulus duration. The novel procedure was validated using a well-known amnesic agent, scopolamine (28), prior to conducting this study (Supplementary Fig. S1). The aim of the current study was to characterize emergent learning and memory deficits during adolescence induced by pre-weanling treatment with either MTX or Ara-C, administered alone or in combination. Since the autoshaping procedure and novel object recognition task both involve one-trial rapid learning paradigms, the conditional discrimination procedure was developed to include an extensive training component presented prior to a rapid training component. A second aim of this study was to compare the effect of extensive versus rapid training on response accuracy, thus to examine whether practice would reduce the extent of learning impairments observed following early exposure to chemotherapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

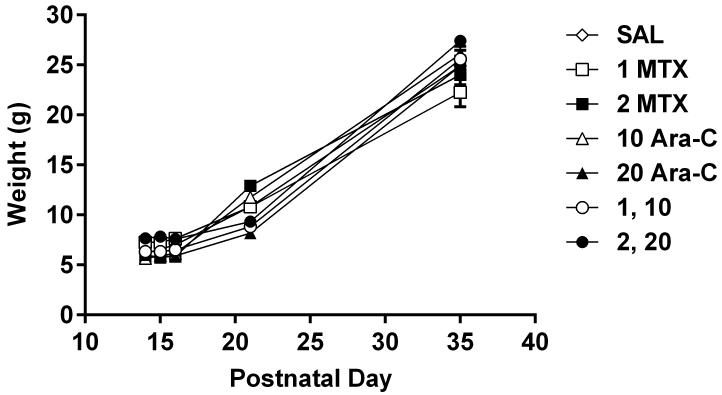

Swiss-Webster pregnant female mice were purchased from SAGE Animals, Inc., (Philadelphia, PA, USA). On average, the pregnant dams delivered their litters 1-3 days after arrival at the central animal facility. Litters were individually-housed with the original dam in plastic cages and were allowed to acclimate to the temperature-and-humidity-controlled facility until the pups were 14 days old. The mice had access to food and water ad libitum during this time. Litters were weaned at PND 21 at which time the pups were group-housed by sex and treatment until behavioral testing began at PND 35 or “periadolescence” (29). At PND 35, 19 days after treatment with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination, a behavioral task was performed. Each mouse was tested in only one of the three behavioral procedures. Prior to behavioral testing at PND 35 there were no significant differences in body weights observed in pups injected with saline or chemotherapeutic agents on PND 14, 15, and 16 (Figure 1). The health of all mice was monitored daily throughout the study, and at no point did chemotherapy-treated mice show evidence of health problems that would have affected performance. All mice were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University and the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Academy Press 1996; NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 2011).

Figure 1.

Effects of MTX and Ara-C on body weight in pups injected on PND 14, 15, and 16. Overall, no significant differences in body weights were observed at PND 35 prior to behavioral testing. Values are Mean ± SEM. Ordinate: Weight in grams. Abscissa: Postnatal day.

Drugs

MTX (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) and Ara-C (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were reconstituted with saline. Injections were administered to pre-weanling mouse pups in a volume of 0.1 mL/10 g, i.p. on PND 14, 15, and 16. Pups were individually weighed prior to the injection. Immediately following the injection, pups were returned to the dam and litter. In this manner, the pups were only removed from the dam for approximately 2 min in order to minimize stress. Each dose of MTX (1 or 2 mg/kg), Ara-C (10 or 20 mg/kg), or MTX and Ara-C combination (1 mg/kg MTX and 10 mg/kg Ara-C or 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C) was administered in a separate group of mice (between-groups design). MTX and Ara-C were stored and handled in accordance with guidelines set forth by the Temple University Department of Environmental Health and Radiation Safety.

To estimate the appropriate treatment doses and regimens for MTX and Ara-C, allometric techniques were used to convert human dosing schedules to comparable adult mouse schedules and temporal comparisons of chronic dosing were made with the pharmacokinetic equation for maximum lifespan potential (30,31). As pharmacokinetic data are not available for pre-weanling mice and adult doses of MTX and Ara-C are approximately 10-fold higher than childhood doses, the pre-weanling pup dose was reduced by 10-fold.

Experiment 1: Autoshaping Task

Apparatus

Twelve experimental chambers as previously described (21.6 cm × 17.8 cm × 12.7 cm, Model ENV-307W, MED Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) were used for the autoshaping procedure (18).

Procedure

The autoshaping procedure was modified from the method previously described for mice by Vanover and Barrett (23) by omitting the non-contingent dipper presentation (32). At PND 34, mice (N=82) were separated into individual cages, weighed, and food-restricted for 24h prior to day 1 acquisition (PND 35). Water remained available ad libitum. On day 1 of the autoshaping procedure, each mouse was weighed and placed inside the experimental chambers for 15 min before its session started. During each session, the house light illuminated the chamber and a tone occurred on a variable-time schedule (mean of 45s, range 4-132s). The tone remained on for 6s or until a nose-poke response occurred. If the mouse made a center-hole nose-poke during the tone, a 0.01-cc dipper filled with a vanilla-flavored liquid nutritional drink Ensure Plus/water (50:50) solution was presented for 3s in the center-hole nose-poke, and the tone was turned off. Nose-poke responses in the absence of the tone were counted but had no programmed consequences. Each session lasted for 2h or until 20 reinforced nose-pokes were recorded. Mice were fed 3g of food and returned to their cages. On day 2, the procedure was repeated.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Each nose-poke into the center nose-poke hole in the presence of the tone resulted in presentation of the dipper of Ensure solution and was recorded as a reinforced response (up to a maximum of 20 in each 2h session). The main measure of acquisition and retention was the mean-adjusted latency. Mean-adjusted latency was the elapsed time, in seconds, to the 10threinforced response minus the latency to the 1st reinforcer (L10-L1). To calculate the rate of dipper-hole nose-poke responding, the total number of dipper nose-pokes made during the session - regardless of the presence or absence of the tone - was recorded and divided by the total session time in seconds for each mouse. This dipper rate measure served as a guide to whether differences in adjusted latency were dependent on overall rate of responding. Nose-pokes in the left and right holes were not reinforced but were counted and divided by total session time as a measure of response discrimination. Data from all mice were included in acquisition measures from the day 1 session. However, mice that failed to achieve at least ten reinforcers on day 1 of testing were excluded from the mean latency measures on day 2. The rationale for this exclusion was that it was not appropriate to evaluate day 2 retention of a response that had been insufficiently reinforced, or not reinforced at all, on day 1 (23,24).

For the autoshaping procedure, the effect of treatment on day 1 mean-adjusted latency was compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison post-hoc tests. To analyze within-group differences between day 1 and day 2 on mean-adjusted latency, dipper response rates, and non-reinforced nose-poke response rates, repeated measures ANOVAs were used. To analyze sex differences within each treatment group on all measures, independent t-tests were used. Significance was set at p<0.05 for all statistical tests.

Experiment 2: Novel Object Recognition

Apparatus

For assessments of novel object recognition the testing cages were identical to those in which mice were housed in the animal facility. The objects used during testing were Lego® figures of equal size and material that differed in design. These were weighted to minimize the movement of objects by mice during trials. Trials were video recorded and later coded by an experimenter blind to treatment groups.

Procedure

The objects to be used were first assessed to ensure that there were neither intrinsic preferences nor aversions and that each object would be explored for similar durations upon initial exposures. Exploration was defined as directing the nose to the object at a distance of no more than 2 cm and/or touching the object with the nose or mouth. Rearing up on the object was counted only if facing toward, but not away from, the object (33,34).

An individual mouse injected on PND 14, 15, and 16 but naïve to behavioral testing (N=84) was placed in a testing cage on PND 35 for a 20 min acclimation period and then returned to its home cage for 30 min. Each mouse was then placed in the same testing cage for Trial 1. The testing cage contained two identical objects placed in the left and right corners at the opposite end of the cage from where the mouse entered. A mouse was always placed in the testing cage facing away from the objects. The amount of time spent exploring each object (defined above) was recorded over a 5 min period. At the end of Trial 1, mice were placed back into the home cage for the duration of the 1h delay period. Following the 1h delay, each mouse was returned to the same testing cage for Trial 2, which contained one of the previous objects (a familiar object) and a novel object, placed in the same locations. The amount of time spent exploring each object was recorded over a 5 min period. Familiar and novel objects, as well as locations of objects, were counterbalanced between subjects.

Data and Statistical Analysis

To assess variability in exploration, total exploration time for both familiar and novel objects was compared between groups. To measure differences in exploration of a familiar versus a novel object after a 1h delay period, exploration time of the novel object was expressed as a percentage of the exploration time of a familiar object as outlined below:

In this measure, 100% indicates an equal amount of time spent exploring the familiar and novel objects, < 100% indicates more time spent exploring the familiar object, and > 100% indicates more time spent exploring the novel object (as described in 15).

For the novel object recognition procedure, the effect of treatment on novel object discrimination and total exploration time was compared using one-way ANOVAs followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison post-hoc tests. To analyze sex differences in novel object discrimination within each treatment group, independent t-tests were used. Significance was set at p<0.05 for all statistical tests.

Experiment 3: Conditional Discrimination

Apparatus

The same 12 experimental chambers described for the autoshaping procedure were used for the conditional discrimination procedure, with the addition of stimulus lights above each poke hole (ENV-321M).

Procedure

The conditional discrimination procedure used a tone/light compound stimulus and temporal duration, and was modified from other conditional discrimination tasks used in rodents (26,35). At PND 34, the mice injected on PND 14, 15, and 16 were separated into individual cages, weighed, and food-restricted for 24h prior to the start of experimental testing. Water remained available ad libitum. On day 1 of training, each mouse was weighed and placed inside an experimental chamber for 15 min before the session started. During each session, the house light illuminated to indicate the availability of a vanilla-flavored liquid nutritional drink, Ensure Plus/water (50:50) solution, which would be presented in a 0.01-cc dipper. These food deliveries were contingent upon correct responding, as defined separately for each phase described below. Each session lasted for 1h, following which mice were fed 3g of food and returned to their cages.

The conditional discrimination procedure involved a series of 8 phases, and specific criteria were completed for each prior to progressing to the next phase. “Extensive training” was defined as completion of Phases 1-5, followed by a test in which a discrimination ratio was measured (Phase 6). “Rapid training” was defined as Phase 7, followed by a test in which a discrimination ratio was measured (Phase 8). Details of each phase are outlined in the supplementary materials. Briefly, during Phases 1 and 2 a nose-poke response into the left or right hole, respectively, was reinforced on a fixed-ratio (FR-1) schedule of reinforcement. During Phases 3 and 4 an audible tone was presented along with an illuminated stimulus light above the left or right poke hole for 2s or 8s, respectively, and a nose-poke response into the correct hole was reinforced. During Phase 5, the duration of the tone/light cue was randomly alternated between short (2s) and long (8s), and a nose-poke response into the correct hole was reinforced. Mice were trained on this set of contingencies to 70% correct responding over two consecutive sessions before the discrimination ratio was assessed during the Phase 6 test session. During Phase 7 the contingencies previously described were reversed and this new set of contingencies was trained for one session before the discrimination ratio was assessed during the Phase 8 test session.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Acquisition was measured by the number of sessions required to reach Phase 1 criteria, defined as 20 reinforced responses in the active nose-poke hole, with the total responses including at least 75% active nose-poke hole responding. To examine the effect of treatment on acquisition, a one-way ANOVA was used, followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison post-hoc tests. The main measure of performance on the conditional discrimination task was the discrimination ratio (26), defined as: [correct responding / (correct + incorrect responding)]*100

The discrimination ratio was calculated for each mouse at Phase 6 and 8 to measure response accuracy following extensive and rapid training, respectively. Only mice that reached the 70% criteria at Phase 5 were included in the following analyses. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess the effect of treatment and training (extensive or rapid) on correct discrimination. Separate one-way ANOVAs with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison post-hoc tests were used to examine treatment effects within each training type (extensive or rapid). Significance for all statistical tests was set at p<0.05.

Results

Experiment 1: Autoshaping Task

Group composition for the autoshaping task is shown in Supplementary Table S1 (N=82). Sex differences within each treatment group revealed a significantly higher dipper response rate (t(10)=2.76, p<0.05) on day 2 for male mice treated with saline compared to female mice treated with saline, although there was no effect on mean-adjusted latency (p>0.05). Among mice treated with 2 mg/kg MTX, there was a significantly shorter mean-adjusted latency (t(10)=2.76, p<0.05) and higher dipper response rate (t(10)=3.02, p<0.05) on day 2 for male mice compared to females. In all other groups no significant differences were found between male and female mice on these measures (p>0.05). Given the small sample size of males and females within each group, data were collapsed for mice given the same saline or chemotherapy treatment.

Saline Control

On day 1, adolescent mice that had been treated with saline as pre-weanlings readily acquired the nose-poke response into the dipper in the presence of the tone. On day 2, the mice were placed back into the experimental chambers and the experimental conditions were identical to day 1. As shown in Figure 2A, mice treated with saline consistently responded in the dipper in the presence of the tone, with a mean-adjusted latency that was significantly shorter than on day 1 (F(1,10)=6.71, p<0.05), as revealed by a repeated measures ANOVA. As shown in Figures 2B and 2C, respectively, the dipper response rate was significantly increased on day 2 compared to day 1 (F(1,11)=25.82, p<0.001), and the non-reinforced response rate was significantly decreased on day 2 compared to day 1 (F(1,11)=10.68, p<0.01). In summary, mice treated with saline responded with a significantly faster latency and dipper response rate, and directed fewer of their responses to the non-reinforced nose-poke holes on day 2, demonstrating that the dipper nose-poke response had been effectively learned on day 1 and retained on day 2.

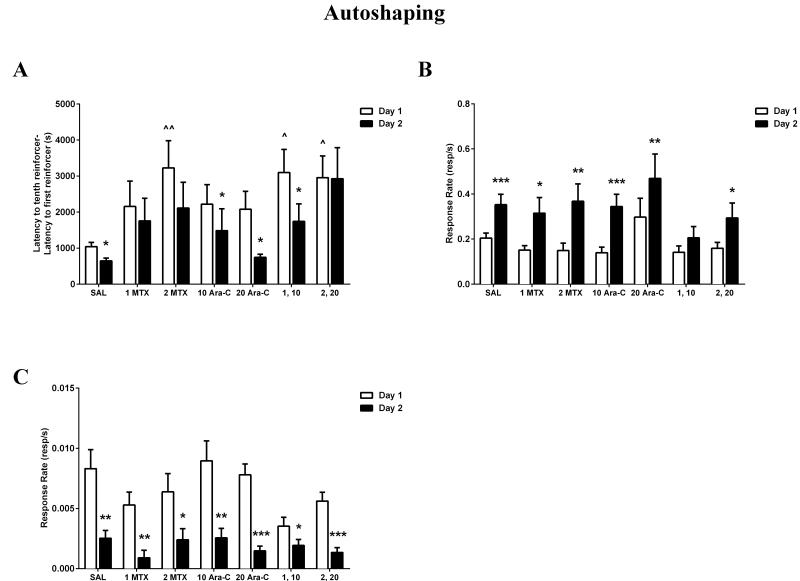

Figure 2.

Effects of early treatment of MTX and Ara-C on mean-adjusted latency (A), reinforced dipper response rate (B), and non-reinforced response rate (C) on day 1 acquisition sessions (open bars) and day 2 retention sessions (filled bars) in an autoshaping task on PND 35. (A) Amount of time to obtain the tenth reinforcer was compared between mice treated with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination on day 1 and day 2. Mice treated with 2 MTX or a combination of MTX and Ara-C displayed a significantly slower acquisition on day 1, compared to saline controls. ^p < 0.01, ^^p < 0.001. Mice treated with MTX or the higher MTX and Ara-C combination showed impaired retention on day 2. *p < 0.05. Ordinate: Latency to the tenth reinforcer minus the latency to the first reinforcer, in seconds. (B) Total reinforced response rates in the dipper nose-poke hole were compared between mice treated with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination on day 1 and day 2. All groups except for the lower MTX and ARA-C combination displayed a significantly increased dipper response rate on day 2 compared to day 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Ordinate: Rate of nose-poke responses per second in the dipper well. (C) Total non-reinforced response rates in the left and right nose-poke holes were compared between mice treated with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination on day 1 and day 2. All groups displayed a significantly decreased non-reinforced response rate on day 2 compared to day 1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Ordinate: Rate of nose-pokes in either the left or right holes per second as a measure of general activity. All Abscissa: Saline or chemotherapy treatment group (dose in milligrams per kilogram, administered i.p.). Values are Mean ± SEM.

Day 1 Acquisition

Compared to saline controls (1179±176s), mice treated with 2 mg/kg MTX (3226±757s), 1 mg/kg MTX and 10 mg/kg Ara-C (3099±639s), or 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C (2957±603s) took significantly longer to obtain the liquid reinforcers on day 1 (Figure 2A), demonstrating an impairment in acquisition of a learned nose-poke response (p<0.01).

Day 2 Retention

Mice treated with 10 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,11)=7.79, p<0.05), with 20 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,10)=7.80, p<0.05), or with 1 mg/kg MTX and 10 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,11)=6.76, p<0.05) responded with significantly faster mean-adjusted latencies on day 2 compared to day 1 (Figure 2A). This demonstrates that the dipper nose-poke response had been effectively learned on day 1 and retained on day 2. However, mice treated with 1 mg/kg MTX, 2 mg/kg MTX, or 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C displayed equal latencies on both days, demonstrating impairment in retention of a learned nose-poke response, specifically that of responding in the dipper well in the presence of the tone (p>0.05).

Only mice treated with the 1 mg/kg MTX and 10 mg/kg Ara-C combination displayed equal dipper response rates on both days (p>0.05). Mice treated with 1 mg/kg MTX (F(1,10)=8.13, p<0.05), with 2 mg/kg MTX (F(1,11)=16.46, p<0.01), with 10 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,11)=26.15, p<0.001), with 20 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,10)=13.40, p<0.01), or with 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,11)=5.94, p<0.05) displayed a significantly increased dipper response rate on day 2 compared to day 1 (Figure 2B). That is, for these mice a greater amount of time was spent poking in the center hole, a response that had been reinforced during the previous session. Therefore, in these groups, it is unlikely that differences in adjusted latency were due to impairments in overall rate of responding.

Mice treated with 1 mg/kg MTX (F(1,10)=14.54, p<0.01), with 2 mg/kg MTX (F(1,11)=6.64, p<0.05), with 10 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,11)=14.49, p<0.01), with 20 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,10)=50.55, p<0.001), with 1 mg/kg MTX and 10 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,11)=5.95, p<0.05), or with 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C (F(1,11)=32.49, p<0.001) displayed significantly decreased non-reinforced response rates on day 2 compared to day 1 (Figure 2C). This demonstrates that all groups of mice directed fewer of their responses to the non-reinforced nose-poke holes on day 2. Therefore, it is unlikely that differences in adjusted latency were due to impairment in response discrimination.

Experiment 2: Novel Object Recognition

Of the mice that completed a novel object recognition task, only those that explored each object for more than 10s during Trial 1 were included in discrimination index and total exploration time analyses (N=81). As a result, three mice from the 20 mg/kg Ara-C group were excluded from these analyses. Group composition for the novel object recognition task is shown in Supplementary Table S1. Given the fact that no significant differences were found between male and female mice within any group, data were collapsed for mice that were given the same saline or chemotherapy treatment.

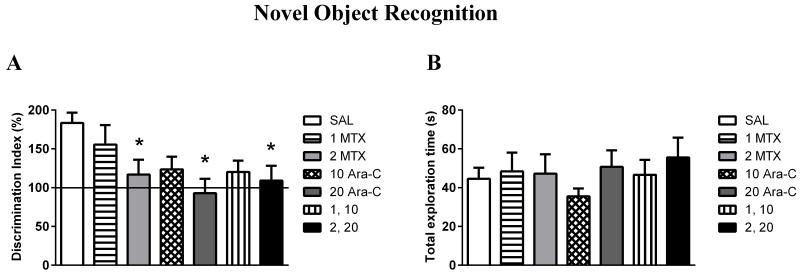

The discrimination index is displayed in Figure 3A. A discrimination index of more than 100% indicates that the mouse spent more time exploring the novel object than the familiar one. Thus, with a discrimination index of 183.34±40.88, saline controls spent significantly more time exploring the novel object compared to the familiar one (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of early treatment of MTX and Ara-C on novel object recognition at PND 35: (A) Discrimination index and (B) Total exploration time. (A) Discrimination of the novel object compared to the familiar object following a 1h delay was compared between mice treated with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination. Mice treated with the higher dose of MTX (2 mg/kg), Ara-C (20 mg/kg), or MTX and Ara-C combination (2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C) spent significantly less time exploring the novel object during the recognition trial, compared to saline controls. *p < 0.05. Ordinate: (Time spent exploring the novel object/time spent exploring the familiar object) × 100. (B) Total exploration time of both objects during the recognition trial was compared between mice treated with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination. There were no significant differences observed between treatment groups. Ordinate: Time spent exploring the novel object + familiar object, in seconds. All Abscissa: Saline or chemotherapy treatment group (dose in milligrams per kilogram, administered i.p.). Values are Mean ± SEM.

A significant effect of pre-weanling treatment on discrimination index (F(6,69)=2.82, p<0.05) was observed, with mice receiving the higher dose of MTX (2 mg/kg), Ara-C (20 mg/kg), or a combination (2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C) spending an equal amount of time exploring both objects and demonstrating a significantly lower discrimination index compared to saline controls (p<0.05). No significant differences were found between the 2 mg/kg MTX, the 20 mg/kg Ara-C, and the 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C groups (p>0.05). Mice receiving the lower dose of MTX (1 mg/kg), Ara-C (10 mg/kg), or a combination (1 mg/kg MTX and 10 mg/kg Ara-C) showed a lower discrimination index compared to saline as well, although these effects did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3A). No significant differences in average total exploration time were observed (Figure 3B) between any of the groups (p>0.05). Therefore, it is unlikely that impairment on the discrimination index is due to an unequal amount of time spent exploring the objects during the test trial.

Experiment 3: Conditional Discrimination

Group composition for the conditional discrimination task is shown in Supplementary Table S1. Of the mice that completed the conditional discrimination task, only mice that reached the 70% criteria at Phase 5 were included in statistical analyses (N=65). No significant differences were found between male and female mice within any group; therefore, the data were collapsed for male and female mice that were given the same treatment.

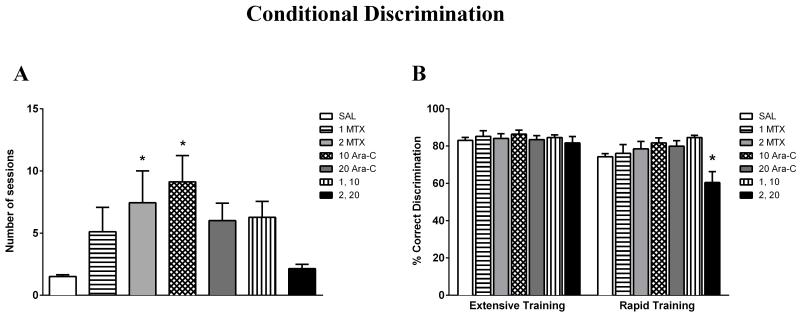

Mice treated with saline or chemotherapeutics were tested at PND 35, 19 days following treatment. As shown in Figure 4A, there was a significant effect of treatment on acquisition (F(6,60)=2.98, p<0.05). In general, chemotherapy-treated mice required a higher number of sessions to reach Phase 1 criteria compared to saline controls, although this effect only reached significance for mice treated with 2 mg/kg MTX or 10 mg/kg Ara-C (p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of early treatment of MTX and Ara-C on conditional discrimination at PND 35: (A) Acquisition and (B) Discrimination ratio following extensive and rapid training. (A) Number of sessions to reach criteria for Phase 1 of the conditional discrimination procedure was compared between mice treated with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination. There was a significant effect of pre-weanling treatment on acquisition, although only mice treated with 2 mg/kg MTX or 10 mg/kg Ara-C required a significantly higher number of sessions to reach criteria compared to saline controls. *p < 0.05. Ordinate: Number of sessions required to reach Phase 1 criteria. Abscissa: Saline or chemotherapy treatment group (dose in milligrams per kilogram, administered i.p.). (B) Accuracy in responding was compared between mice treated with saline, MTX, Ara-C, or a MTX and Ara-C combination following extensive and rapid training. There was no significant difference in discrimination ratio between groups following extensive training. There was a significantly lower discrimination ratio in mice treated with the higher combination (2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C), relative to saline controls, following rapid training. *p < 0.05. Ordinate: [correct responding/(correct + incorrect responding)]*100. Abscissa: Training type. Values are Mean ± SEM.

As revealed by a repeated measures ANOVA and displayed in Figure 4B, the discrimination ratio was lower following rapid training relative to extensive training for all groups (F(1,58)=38.13, p<0.001). There was a significant interaction between treatment and training (F(6,58)=3.82, p<0.01). Separate one-way ANOVAs for each training type revealed no significant difference in discrimination ratio between groups following extensive training (p>0.05), but a significant difference in discrimination ratio between groups following rapid training (F(6,58)=4.78, p<0.001). Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison post-hoc tests revealed a significantly lower discrimination ratio only in mice treated with the higher combination treatment (2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C) relative to saline controls (p<0.05). In addition, several chemotherapy-treated groups earned fewer reinforcer deliveries following rapid training compared to extensive training, such as mice treated with 2 mg/kg MTX (p<0.05), 10 mg/kg Ara-C (p=0.08), and 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C (p<0.05). Saline-treated mice earned a comparable number of reinforcers following both types of training (p>0.05).

Discussion

In the current study, pre-weanling mice were treated on PND 14, 15, and 16 with saline, MTX, or Ara-C, injected alone or in combination. Behavioral tests conducted 19 days following treatment revealed impairment on simple, one-trial learning tasks tested once during the adolescence phase of development. More specifically, MTX alone and in combination with Ara-C appeared to be the most deleterious for producing disruptions of acquisition and retention without altering response rates or response discrimination in the autoshaping procedure. In the novel object recognition task, higher doses of MTX and Ara-C, as well as their combination, disrupted short-term recognition memory without altering total exploration time. Findings from the conditional discrimination procedure revealed impairment in acquisition for chemotherapy-treated mice relative to saline controls, with these groups requiring a higher number of sessions to reach the first set of criteria and move forward with training. Impairment in acquisition and short-term retention are consistent with clinical studies suggesting that childhood cancer survivors are slower at learning new information (36) and primarily show deficits in memory (6,37). Cognitive late effects are emergent in that they usually present three or more years post-diagnosis (38).

The main measure of performance on the conditional discrimination task was the discrimination ratio, which was calculated following both extensive and rapid training. There was no difference found between groups following extensive training. This result is not surprising given that mice were trained to 70% correct discrimination prior to testing, demonstrating that comparable performance can be obtained between saline- and chemotherapy-treated mice even though, initially, it may take longer for the chemotherapy-treated mice to reach this level. Impairment in acquisition was generally found for the chemotherapy-treated mice relative to saline controls, with these groups requiring a higher number of sessions to reach the first set of criteria and move forward with training. Once criteria on Phase 1 were reached it was unusual for mice to display any further delay in progress through the remainder of the phases (data not shown). The original hypothesis that mice treated with MTX and Ara-C would display impairment following rapid training was not fully supported, however. Overall, all groups had a lower discrimination ratio following rapid training compared to their discrimination ratio following extensive training, but only the 2 mg/kg MTX and 20 mg/kg Ara-C combination group showed a difference in response accuracy compared to saline. This combination group did not display an initial delayed acquisition, but later revealed impairment when the original contingencies were reversed. In addition, although only one group displayed significantly lower response accuracy compared to saline controls following rapid training, several chemotherapy-treated groups earned fewer reinforcer deliveries compared to the number earned following extensive training. This finding suggests that chemotherapy-treated mice had a higher number of omitted trials during the rapid training test session compared to the saline group, which earned a comparable number of reinforcer deliveries following both types of training.

To date, there has been a lack of preclinical models to study the development of cognitive late effects after chemotherapeutic treatment in childhood ALL survivors (39). Thus, a notable aspect of the current study is the use of a developmental framework for assessing the emergent effects of early chemotherapeutic treatment. This stands in contrast to the growing literature focused on models in adult rodents (7,40 for review). For example, the autoshaping procedure has been used to study cognitive deficits in adult mice produced by single and repeated administration of several chemotherapeutics (18,41). The fact that methotrexate alone fails to alter acquisition or retention in adult mice while impacting mice treated at a younger age using an identical procedure, emphasizes the importance of a developmental framework when modeling the late effects of childhood ALL treatment. A single administration of MTX in adult rats produced disruption on a novel object recognition task following a 1h delay (15). However, results have been inconsistent in the area of discrimination learning, including both Pavlovian and instrumental procedures. In the small number of studies examining the effects of early MTX treatment in rat pups, deficits on conditioned emotional response and conditioned taste aversion tasks have been noted in some (10) but not all cases (12). Yadin et al., (9) observed deficits at 12-14 weeks old on a simultaneous discrimination task in rats given pre-weanling MTX treatment but only when in combination with cranial radiation therapy. Winocur et al. (42) found no effect on discrimination learning using a black-white discrimination task following treatment of MTX and 5-fluorouracil in adult mice. In contrast, Winocur et al. (43) found impairment on the same discrimination task following identical treatment. The conditional discrimination procedure used in the present study involved an additional requirement by including a hippocampus-sensitive discrimination reversal. Previous studies in the area of developmental toxicology suggest that the reversal component may be more sensitive to disruption following toxicant exposure compared to the initial discrimination learning (44). Impairment exhibited by the higher combination group during the reversal phase is potentially related to the hippocampus-dependent deficits displayed by this treatment group on the novel objection recognition task. Therefore, the current findings fit into the growing literature surrounding chemotherapy-induced cognitive deficits, which suggests that tasks dependent on the hippocampus or frontal lobes are more sensitive to chemotherapeutics compared to tasks dependent on subcortical structures such as the caudate nucleus and related striatal structures (42,43). While the current findings are more consistent with hippocampus-sensitivity, results from this model do not exclude a role for the frontal lobes in chemotherapy-induced deficits; however, additional behavioral tasks would need to be examined to ascertain this relationship. Further research examining differential vulnerability to the neurotoxic effects of chemotherapeutics among brain regions is warranted.

It is important to study chemotherapy treatment in developing rodent brains, since toxins or stress during early development can have more severe long-term effects than identical damage in the mature adult rodent brain (45,46). Li et al. (8) examined the effects of both acute and chronic MTX treatment using male rats, beginning at PND 15. Their findings are in contrast to the current study in that they observed impairment on an object placement test but not on an object recognition task. However, several differences separate these two studies, including differences of species and of dosing regimen. Li et al. (8) treated rats with 1 mg/kg MTX while the current study treated mice with either 1 or 2 mg/kg MTX, and significant deficits were only observed with the higher dose in the current study. It is conceivable that the type of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment is dependent on the timing and length of treatment delivery, which could be further impacted by strain and sex. Additional studies using preclinical models of childhood chemotherapeutic treatment are needed in order to sort through these important variables.

The occurrence of only mild deficits on the conditional discrimination procedure presented here has important clinical implications for rehabilitation of cancer survivors experiencing chemotherapy-induced learning deficits as well, for the present results suggest that impairment may be ameliorated through extensive training or practice. This idea is consistent with findings from Boyette-Davis et al. (47), where rats underwent a paclitaxel treatment regimen that produced mechanical sensitivity but failed to produce impairment on the five-choice serial reaction time task. Similar to the conditional discrimination procedure used here, this assay included an extensive training phase requiring rodents to reach a 70% criterion before beginning the testing phase. Massed practice and repetition are also central components of a cognitive remediation program proposed for childhood cancer survivors experiencing difficulty in school, which includes techniques derived from brain injury rehabilitation, special education, and clinical psychology (48-50). The beneficial outcome of practice effects is comparable to the concept of overlearning presented by Reid (51), in which rats that received 150 overtraining trials past a criterion level required substantially fewer trials to reach criterion on a new discrimination condition compared to rats trained only to criterion on the initial discrimination.

A notable observation for the current study is the lack of data supporting synergistic toxicity in any measure for the two chemotherapeutic agents. However, there is not an a priori reason why MTX and Ara-C should be synergistic or additive for the behavioral endpoints chosen. It is possible that the combinations examined may be sub-additive and the administration of one agent diminishes the toxicity of the other (52). Lower doses of MTX in combination with 5-fluorouracil produced greater cognitive deficits than higher doses of MTX in combination with 5-fluorouracil in adult mice (18,41). Future studies should expand on our assessment through more quantitative methods to further classify these drug interactions. Additional testing of time points (earlier or later) may reveal increased deficits for the combinations compared to single agents.

The experiments described herein represent the foundation for a novel mouse model in the area of cognitive late effects in childhood cancer survivors, and findings support further investigation. One limitation of the present study is that healthy naïve mice were treated with chemotherapeutic agents, as oppose to mice bearing an ALL-related cancer. While this is a logical next step, only a couple of laboratories have been able to inject xenografts from patients with ALL into NOD/SCID mice to attempt to model ALL with any success (53,54 for review of humanized mouse models). However, the validity of using healthy rodents is supported by the finding that tumor presence does not potentiate a MTX-induced decrease of cell proliferation in the hippocampus (16). In addition, although a number of studies have demonstrated CNS toxicity and behavioral deficits for systemic MTX (15) and cytarabine (20) in adult rodents, using intrathecal administration would strengthen clinical relevance. Future studies using the present model should assess later time points to clarify whether the deficits observed represent sub-acute toxicity that would subsequently resolve or yield true persistent deficits, although different learning tasks more amenable to repeated testing than those used in the current study would be required to follow the trajectory of the deficits into adulthood. The present findings do not address mechanisms of neurotoxicity; although such data have been collected in adult rodents (7 for review) future research involving young rodents is warranted.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that early exposure to chemotherapeutics MTX and Ara-C, presented alone or in combination, can disrupt acquisition and retention of a learned response as well as short-term recognition memory tested once 19 days following treatment. The occurrence of decreased response accuracy following a one session rapid training in only one chemotherapy treatment group suggests that extensive training or practice may help to ameliorate learning impairment. This has clinical implications to support the use of cognitive remediation and similar techniques in school-aged children experiencing cognitive late effects from chemotherapy treatment. The preclinical model presented within a developmental framework is unique and its continued use is supported by clinically relevant findings. However, the current study also highlights the need for further expansion in the area of preclinical models for the emergent effects of childhood chemotherapeutic treatment.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common form of cancer in children and adolescence, has a survival rate of over 90%. Clinical studies estimate that among survivors given chemotherapy-only treatment, 40-70% experience neurocognitive impairment. Neurophysiological evidence for these deficits has implicated white matter, hippocampus, and prefrontal abnormalities resulting from the chemotherapeutic agents methotrexate and cytarabine, which are commonly co-administered during CNS prophylaxis. A growing literature examines the effects of cancer chemotherapeutics in preclinical models of learning and memory in adult rodents. These models are not adequate for studying the role of emergent effects of childhood treatment, and studies using young rodents remain limited. The present study reveals impairment on simple, one-trial learning tasks tested once 19 days following treatment during the adolescence phase of development. The occurrence of only mild deficits on an extensive training task suggests that practice may ameliorate deficits, which supports the continued development of cognitive remediation programs for childhood cancer survivors.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Alyssa Myers for her technical assistance with these experiments. These experiments were completed in fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral degree of Emily Bisen-Hersh.

Grant Support

This work was supported by NIH R01 CA129092 to EAW and NIH-NIDA training grant fellowship T32 DA07237 to Temple University Department of Pharmacology.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Pui C, Evans WE. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:166–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegler BJ, Kennedy K, Maze R, Greenberg ML, Weitzman S, Hitzler JK, et al. Comparison of long-term neurocognitive outcomes in young children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with cranial radiation or high-dose or very high-dose intravenous methotrexate. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3858–3864. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waber DP, Turek J, Catania L, Stevenson K, Robaey P, Romero I, et al. Neuropsychological outcomes from a randomized trial of triple intrathecal chemotherapy compared with 18 gy cranial radiation as CNS treatment in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: findings from Dana-Farber cancer institute ALL consortium protocol 95-01. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4914–4921. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krull KR, Okcu MF, Potter B, Jain N, Dreyer Z, Kamdar K, et al. Screening for neurocognitive impairment in pediatric cancer long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4138–4143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buizer AI, de Sonneville LMJ, Veerman AJP. Effects of chemotherapy on neurocognitive function in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a critical review of the literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:447–454. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddick WE, Conklin HM. Impact of acute lymphoblastic leukemia therapy on attention and working memory in children. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:655–659. doi: 10.1586/ehm.10.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seigers R, Fardell JE. Neurobiological basis of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment: a review of rodent research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:729–741. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Vijayanathan V, Gulinello ME, Cole PD. Systemic methotrexate induces spatial memory deficits and depletes cerebrospinal fluid folate in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;94:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadin E, Bruno L, Micalizzi M, Rorke L, D’Angio G. An animal model to detect learning deficits following treatment of the immature brain. Child’s Brain. 1983;10:273–280. doi: 10.1159/000120123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanovski JA, Packer RJ, Levine JD, Davidson TL, Micalizzi M, D’Angio G. An animal model to detect the neuropsychological toxicity of anticancer agents. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1989;17:216–221. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950170309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullenix PJ, Kernan WJ, Schunior A, Howes A, Waber DP, Sallan SE, et al. Interactions of steroid, methotrexate, and radiation determine neurotoxicity in an animal model to study therapy for childhood leukemia. Pediatr Res. 1994;35:171–178. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stock HS, Rosellini RA, Abrahamsen GC, McCaffrey RJ, Ruckdeschel JC. Methotrexate does not interfere with an appetitive pavlovian conditioning task in sprague-dawley rats. Physiol Behav. 1995;58:969–973. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00147-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregorios JB, Gregorios AB, Mora J, Marcillo A, Fojaco RM, Green B. Morphologic alterations in rat brain following systemic and intraventricular methotrexate injection: light and electron microscopic studies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1989;48:33–47. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vezmar S, Becker A, Bode U, Jaehde U. Biochemical and clinical aspects of methotrexate neurotoxicity. Chemotherapy. 2003;49:92–104. doi: 10.1159/000069773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seigers R, Schagen SB, Beerling W, Boogerd W, van Tellingen O, van Dam FS, et al. Long-lasting suppression of hippocampal cell proliferation and impaired cognitive performance by methotrexate in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2008;186:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seigers R, Pourtau L, Schagen SB, van Dam FS, Koolhaas JM, Konsman JP, et al. Inhibition of hippocampal cell proliferation by methotrexate in rats is not potentiated by the presence of a tumor. Brain Res Bull. 2010;81:472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madhyastha S, Somayaji SN, Rao MS, Nalini K, Bairy KL. Hippocampal brain amines in methotrexate-induced learning and memory deficit. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:1076–1084. doi: 10.1139/y02-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foley JJ, Raffa RB, Walker EA. Effects of chemotherapeutic agents 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate alone and combined in a mouse model of learning and memory. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:527–538. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich J, Han R, Yang Y, Mayer-Proschel M, Noble M. CNS progenitor cells and oligodendrocytes are targets of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro and in vivo. J Biol. 2006;5:22.1–22.23. doi: 10.1186/jbiol50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li CQ, Liu D, Huang L, Wang H, Zhang JY, Luo XG. Cytosine arabinoside treatment impairs the remote spatial memory function and induces dendritic retraction in the anterior cingulate cortex of rats. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77:237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filley CM. Toxic leukoencephalopathy. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1999;22:249–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akutsu M, Furukawa Y, Tsunoda S, Izumi T, Ohmine K, Kano Y. Schedule-dependent synergism and antagonism between methotrexate and cytarabine against human leukemia cell lines in vitro. Leukemia. 2002;16:1808–1817. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanover KE, Barrett JE. An automated learning and memory model in mice: pharmacological and behavioral evaluation of an autoshaped response. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:273–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett JE, Vanover KE. Assessment of learning and memory using the autoshaping of operant responding in mice. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2003;25:8.5F.1–8.5F.8. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0805fs25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudchenko PA. An overview of the tasks used to test working memory in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn MJ, Futter D, Bonardi C, Killcross S. Attenuation of d-amphetamine-induced disruption of conditional discrimination performance by α-flupenthixol. Psychopharmacology. 2005;177:296–306. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1954-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrier AM, Thompson CR. Conditional discrimination learning: a critique and amplification. J Exp Anal Behav. 1980;33:291–298. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1980.33-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klinkenberg I, Blokland A. The validity of scopolamine as a pharmacological model for cognitive impairment: a review of animal behavioral studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:1307–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laviola G, Macri S, Morley-Fletcher S, Adriani W. Risk-taking behavior in adolescent mice: psychobiological determinants and early epigenetic influence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boxenbaum H. Interspecies scaling, allometry, physiological time, and the ground plan of pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1982;10(2):201–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01062336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang H, Mayersohn M. A mathematical description of the functionality of correction factors used in allometry for predicting human drug clearance. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;2005;33(9):1294–1296. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.004135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davenport JW. Combined autoshaping-operant (AO) training: CS-UCS interval in rats. Bulletin of the Psychomonic Society. 1974;3:383–385. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sik A, van Nieuwehuyzen P, Prickaerts J, Blokland A. Performance of different mouse strains in an object recognition task. Behav Brain Res. 2003;147:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathiasen JR, Dicamillo A. Novel object recognition in the rat: a facile assay for cognitive function. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2010;49:5.59.1–5.59.15. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0559s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dix S, Gilmour G, Potts S, Smith JW, Tricklebank M. A within-subject cognitive battery in the rat: differential effects of NMDA receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology. 2010;212:227–242. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer SL, Goloubeva O, Reddick WE, Glass JO, Gajjar A, Kun L, et al. Patterns of intellectual development among survivors of pediatric medulloblastoma: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2302–2308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashford J, Schoffstall C, Reddick WE, Leone C, Laningham FH, Glass JO, et al. Attention and working memory abilities in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2010;116:4638–4645. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moleski M. Neuropsychological, neuroanatomical, and neurophysiological consequences of CNS chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Archives of Clin Neuropsych. 2000;15:603–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bisen-Hersh EB, Hineline PN, Walker EA. Disruption of learning processes by chemotherapeutic agents in childhood survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and preclinical models. J Cancer. 2011;2:292–301. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker EA. Animal Models of Chemotherapy-induced Learning and Memory Deficits. In: Raffa RB, Tallarida RJ, editors. ‘Chemofog’: Cognitive Deficits Associated with Cancer Chemotherapy. RG Landes Bioscience, Inc.; Austin, Texas: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker EA, Foley JJ, Clark-Vetri R, Raffa RB. Effects of repeated administration of chemotherapeutic agents tamoxifen, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil on the acquisition and retention of a learned response in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:539–548. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winocur G, Vardy J, Binns MA, Kerr L, Tannock I. The effects of the anti-cancer drugs, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil, on cognitive function in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winocur G, Henkelman M, Wojtowicz JM, Zhang H, Binns MA, Tannock IF. The effects of chemotherapy on cognitive function in a mouse model: a prospective study. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(11):3112–3121. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winneke G, Brockhaus A, Baltissen R. Neurobehavioral and systemic effects of longterm blood lead-elevation in rats. I. Discrimination learning and open field-behavior. Arch Toxicol. 1977;37(4):247–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00330817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Praag H, Mei Qu P, Elliott RC, Wu H, Dreyfus CF, Black IB. Unilateral hippocampal lesions in newborn and adult rats: effects on spatial memory and BDNF gene expression. Behav Brain Res. 1998;92:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rayen I, van den Hove DL, Prickaerts J, Steinbusch HW, Pawluski JL. Fluoxetine during development reverses the effects of prenatal stress on depressive-like behavior and hippocampal neurogenesis in adolescence. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyette-Davis JA, Fuchs PN. Differential effects of paclitaxel treatment on cognitive functioning and mechanical sensitivity. Neurosci Lett. 2009;453:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler RW. Attentional processes and their remediation in childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1998;(Suppl 1):75–78. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(1998)30:1+<75::aid-mpo11>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butler RW, Copeland DR. Attentional processes and their remediation in children treated for cancer: a literature review and the development of a therapeutic approach. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butler RW, Copeland DR, Fairclough DL, Mulhern RK, Katz ER, Kazak AE, et al. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial of a cognitive remediation program for childhood survivors of a pediatric malignancy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:367–378. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reid LS. The development of non-continuity behavior through continuity learning. J Exp Psychol. 1953;46:107–112. doi: 10.1037/h0062488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayer LD, Janoff AS. Optimizing combination chemotherapy by controlling drug ratios. Mol Interv. 2007;7(4):216–223. doi: 10.1124/mi.7.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato I, Niwa A, Heike T, Fujino H, Saito MK, Umeda K, et al. Identification of hepatic niche harboring human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells via the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ito R, Takahashi T, Katano I, Ito M. Current advances in humanized mouse models. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9(3):208–214. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.