INTRODUCTION

Economic, social and political instability are now widespread throughout the globe, driven in part by what may be a long-term deep recession in living standards, repeated financial crises, and governments’ frequent austerity measures, including efforts to cut back on public spending and social services. This has led to widespread social struggles in many European countries, unrest in Wisconsin and other parts of the US (e.g., “Occupy Wall Street” and Walmart strikes), the “Arab spring,” and much additional political turmoil. Reductions in funding for HIV and related areas of research, prevention and care linked to overall spending cutbacks may lead to “rebound” epidemics or to widespread multidrug resistant strains of HIV. Ominously, recent financially-driven cutbacks in jobs and in social and health services, and their subsequent social turmoil, have been followed by HIV outbreaks among injection drug users (IDUs) in Greece and Romania (1, 2, 3).

“Big events” and economic hard times that resemble this situation to some degree have contributed to epidemics of other infections; economically driven cutbacks in tuberculosis programs in the US and in Central and Eastern Europe have been associated with increases in tuberculosis (4, 5, 6). Recent economic hard times and class struggles in Greece seem to have contributed to increased influenza mortality rates, and West Nile, malaria and HIV outbreaks in that country (7). Political transitions and economic difficulties in the 1990s may have facilitated HIV epidemics in the former Soviet Union, South Africa, Indonesia and other countries (8). However, big events do not always spark infectious disease outbreaks. The economic crisis and political upheavals and transitions in Argentina about a decade ago seem not to have sparked an HIV outbreak, nor did the events in the Philippines in the 1980s.

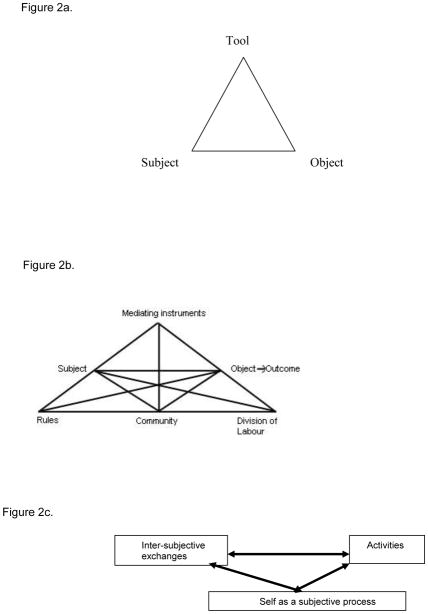

Our earlier efforts to understand these events led us to develop a “pathways model” that summarized what was then known or hypothesized. This model is summarized in Figure 1 (8).

Figure 1.

Historically-situated pathways through which Big Events may sometimes unleash HIV epidemics and other harms*, **

*In some cases, such as with normative regulation and the organization of gender and sexuality, and as with corruption and insecurity (fear for one’s personal safety), variables that fit together in homologous places in the system of arrows (pathways) have been grouped together so the model remains readable.

**This is reprinted from Friedman, Rossi & Braine (2009). We have not updated it but rather treat it as a historical document to be discussed and criticized in the text of this paper.

This pathways model has a number of weaknesses, in particular, the fact that it can easily be interpreted as an analytic rather than a dialectical model. An analytic model, as we are using the term here, sees non-overlapping parts as the building blocks of larger structures, and furthermore sees variables as non-overlapping characteristics of parts or sets of parts. Dialectical models, on the other hand, focus on processes, and see large-scale structures and processes as in many ways constitutive of their parts. Furthermore, dialectical models see change as taking place through contradictions that develop internally within a structure or process and then lead to processes that may themselves conflict, but which may resolve the contradictions. To clarify what we mean here, an analytic interpretation of Figure 1 is not appropriate for understanding processes in which a actions and related discontinuous leaps in belief systems and values by those affected by the big events may shape the processes being studied and thus the historical outcomes, and b. apparently distinct variables are interacting and even mutually co-defining each other as parts of larger processes. Friedman and Rossi (9) have described the value of a dialectical approach to understand HIV and other epidemics, particularly in such dynamic times as these. Such an approach can take into account how large-scale changes affect the immediate environments of individuals and small groups; how these changes are interpreted by individuals and small groups; how the actions of these individuals and small groups affect their immediate and larger-scale social contexts; and how all of these affect HIV risk, infection, and disease development for the individuals and for the epidemic as a whole.

We suggest that efforts to understand these processes may benefit from consideration of Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT). CHAT researchers have focused on human development (10), its implications for education (11, 12) and educational change interventions (13), on workplaces and workplace interventions (clearly relevant to the workplace-based complexities of implementing new kinds of interventions) (14), and social movements (15). Insofar as we are aware, no one has previously applied CHAT approaches to public health, social aspects of sexual and drug-taking behaviours and networks, or epidemics of HIV or related diseases.

CHAT was developed in the years shortly after the Russian Revolution by Vygotsky (16) and Leontiev (17, 18) as a way to understand and transform human life. It was partly a response to behaviorism and psychoanalysis as they interpreted them in the 1920s—i.e., as being based in natural-biological and universal processes—rather than as seeing human psychology and consciousness as historically-variable and as fundamentally involving interaction with what people do and with what other people do and think. Engestrom (19, 20) and Stetsenko (21, 23, 23) have developed CHAT in important ways since.

In CHAT, the relationship between a human agent and her or his environment is dialectically mediated by “tools” and “signs.” One dialectical aspect of such mediation is that the person, the tools, and the signs are not viewed as separate entities but as overlapping ones, such that the person, tools and signs incorporate each other as part of their (changing) natures. For example, the use of word processing tools in writing this article is part of how we think about these issues, and the words that we word process reshape our thinking and perhaps our beliefs in ways different from what we might have experienced a generation ago by writing on a typewriter, and our experience in performing this and prior work has shaped whether we use PCs or Apples as well as the software we use.

There are three core concepts in CHAT that we will emphasize in general and with respect to how these may inform thinking about the HIV epidemic: 1. activities (described in the next paragraph); 2. intersubjective exchange; and 3. self as a subjective process. Intersubjective exchange refers to both normative communication (how individuals communicate with friends and relatives in their direct networks) and conceptual communication (how individuals perceive and communicate about their more macro social contexts). Self as a subjective process refers to how individuals view themselves in macro social contexts and how these perceptions of self change in changing contexts. These concepts will be discussed further below.

In CHAT, “activity” is a key concept. An activity is an ongoing pattern of action like a long-term class project, an HIV prevention program, or a person’s efforts to avoid transmitting HIV to others. Thus, activities encompass specific actions or behaviors as subsets at a lower level of analysis. Depending on the context, the activities being analyzed can be those of an individual, an organization, a social movement, or a State.

Activity is analyzed with respect to its inner dynamic relations and historical change. CHAT is a way to study and intervene in the deep contradictions that give rise to visible lack of coordination (for example, of service delivery systems) and conflict. “Contradictions” can be thought of as system-generated contradictory processes that lead to conflict or to crises for those involved. In the context of the current Greek political and economic crisis, for example, the global economic crisis that came to a head in 2008 and the political-economic contradictions of the Euro Zone have brought the inner dynamics of class and State in Greece into a situation that leads both to major social strife and to lack of coordination in health systems. CHAT sees these contradictions as primary sources of development (good or bad) and progression even though contradictions are often experienced negatively by participants. One way in which this can happen is when participants who are negatively affected demand change. Thus, systems of interaction among the biological and the social, including those related to HIV epidemics, are almost always in the process of working through such contradictions (9).

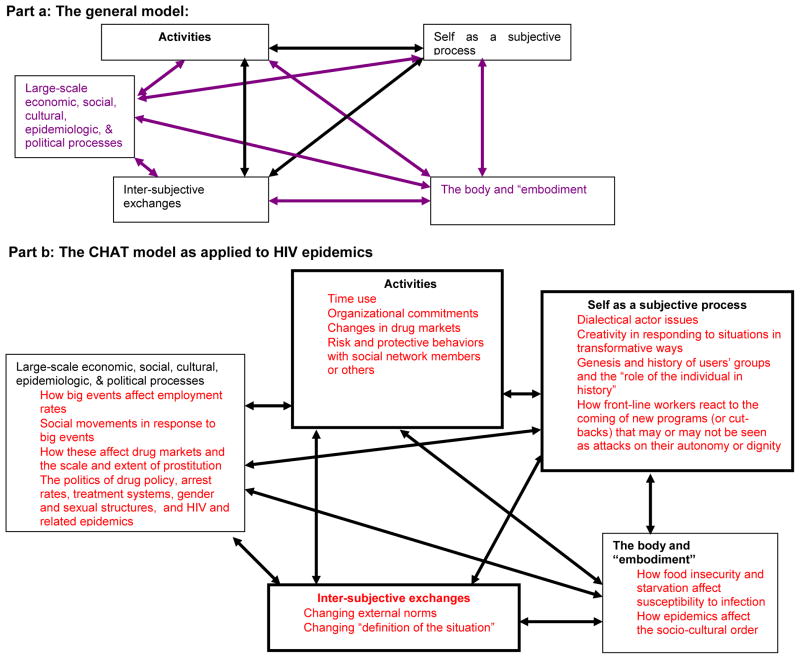

More specifically, CHAT envisions changes in activities as changing large complex systems through a period of contradictions and resolutions of contradictions. In its initial formulation, Vygotsky (16) formulated it as artifact-mediated action in that action consists of a subject (or actor), an object (either an entity or a goal), and mediational tools. In other words, actors engage in activities with “tools,” which can be material (such as screwdrivers or telephones) or conceptual (such as language or the scientific method) as mediators to change material or social objects. (See Figure 2a.)

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Vygotskian model of tool-mediated action

Figure 2b. Engeström’s “Activity System”

Note that the Vygotsky triangle from Figure 2a is the top part of this diagram.

Figure 2c. Stetsenko’s CHAT model of interrelated non-linear, overlapping and often-contradictory processes.

Engestrom (19, 20) expanded this view. (See Figure 2b.) The relation between subject and object is mediated by tools (or instruments), that between subject and community (sometimes framed as the community of significant others) is mediated by rules (norms or constraints), and that between object and community is mediated by the division of labor. Each of the mediating elements is historically formed and open to further development. When a new activity (such as an intervention, or a new way of taking drugs) is formed, the corresponding mediating elements are reconstructed through potentially-conflictual processes driven by contradictions. These can be uneven and discontinuous processes, rather than smooth or linear ones.

The meaning of some terms in CHAT can vary depending on the level of analysis. “Subject,” for example, can mean the “self” at the level of the individual, or it can mean an organization at a higher level of analysis. Similarly, “objects” might mean ”clients” from the perspective of a front-line worker (“subject”), but the “object” of some activities by an HIV prevention or care organization might be the organization’s funder or funding stream. From the perspective of an IDU, “tools” might be social or physical resources that she can use to help get drugs (a key object), subject to rules set by the local community.

Stetsenko frames these concepts in a perspective that is particularly useful for thinking about how macro-level changes interact with local contexts and how individuals and small groups react to this. Central to her perspective—and to much of the way in which we use CHAT later in this paper—is a concept of change as involving the development and contradictions among three interrelated non-linear, overlapping and often-contradictory processes: 1. human activities (ongoing patterns of interaction); 2. how people think about themselves (“self as a subjective process”) and their place in the world (as when being able to take part as volunteers in harm reduction programs leads drug users onto the first steps towards recovery); and 3. changes in norms, local cultures, and interaction among people through communication and exchange (“intersubjective exchange”). In Figure 2c, then, changes at a macro-level can include changes in which large-scale patterns of coordinated activities like the health system or policing institutions as a whole, inter-subjective exchanges like list-serve discussions of what these changes mean for daily life, and organizations’ sense of their missions (“selves”) co-evolve with each other. Alternatively, Figure 2c can model how changes in daily activities, normative communication at the neighborhood or workplace level, and teenagers’ sense of their occupational and sexual futures mutually evolve and affect each other. It is useful to quote Stetsenko (21) here to frame her argument in its own richness of theoretical reference.

One of the central pillars of CHAT is the idea that human development is based on active transformations of existing environments and creation of new ones achieved through collaborative processes of producing and deploying tools. These collaborative processes (involving development and passing on, from generation to generation, the collective experiences of people) ultimately represent a form of exchange with the world that is unique to humans—the social practice of human labor, or human activity. In these social and historically specific processes, people not only constantly transform and create their environment; they also create and constantly transform their very lives, consequently changing themselves in fundamental ways and, in the process, gaining self-knowledge. Therefore, human activity—material, practical, and always, by necessity, social collaborative processes aimed at transforming the world and human beings themselves with the help of collectively created tools—is the basic form of life for people. This practical, social, purposeful activity (or human labor) as the principal and primary form of human life, and the contradictions brought about in its development, lie at the very foundation and are formative of everything that is human in humans. (p. 72)

Pivotal for Vygotsky’s (e.g., 1997) system of ideas was that the social exchanges between people lie at the foundation of all intra-subjective processes, because these processes originate from inter-subjective ones in both history and the individual lives of human beings. (p. 74)

The differences in relative emphasis between Vygotsky and A. N. Leontiev notwithstanding, the common fundamental premise of cultural–historical activity theory can be formulated as follows. Human subjectivity is not some capacity that exists in individual heads; evolves on its own, purely mentalist grounds; and develops according to some inherent laws of nature. Instead, psychological processes emerge from collective practical involvements of humans with each other and the world around them; they are governed by objective laws and are subordinate to the purposes of these practical involvements. In even broader terms, the development of human mind is conceptualized as originating from practical transformative involvements of people with the world, and as a process that can be understood only by tracing its origination in these involvements and practices.)

However, such a broad—and powerfully materialist—formulation is clearly emphasizing a one-sided dependence of human subjectivity on the processes of material production (especially in A. N. Leontiev’s works) and on associated societal forms of exchange between people (especially in Vygotsky’s works). Namely, human subjectivity is conceptualized as originating from, and subordinate to, the collective exchanges and material production. This formulation is lacking one important idea that was implicitly present in Marx’s works—the idea that in human history there exists not only an interdependence and co-evolution of the material production on the one hand, and the societal (i.e., collective, inter-subjective) forms of life, on the other. One other aspect of human life also co-evolves together with these two processes. Namely, the subjective mechanisms allowing for individual participation in collective processes of material production are also implicated in the functioning of what essentially is a unified three-fold system of interactions. That is, the idea that still needs to be spelled out is that all three processes at the very foundation of human life and development—the material production of tools, the social exchanges among people, and the individual mechanisms regulating this production and these exchanges—all co-evolve, interpenetrating and influencing each other, never becoming completely detached or independent from each other. All three types of processes need to be viewed as truly dialectically connected, that is, as dependent upon and at the same time conditioning and influencing each other, with this dialectical relation emerging and becoming more and more complex in human history. (74)

Stetsenko’s interpretation of CHAT thus helps us understand a. how changes in human activities lead to changes in how people think about themselves (“self as a subjective process”) and their place in the world; and b. how changes in activities and in subjective senses of the self lead to changes in norms, local cultures, and interaction among people through communication and exchange (“intersubjective exchange”). These in turn lead to and overlap with changes in what people do and how they do it.

WHAT DOES CHAT HAVE TO DO WITH HIV/AIDS AND RESEARCH ABOUT THE EPIDEMIC?

Let us now consider how the above discussion may help us think about HIV/AIDS epidemics and efforts to combat them in a period of socially and politically tumultuous hard times. Clearly, such a period has many implications for what people do and think. Hard times alter the way in which people spend their time—e.g., they may end up no longer spending their time working at a job and housework, and instead find themselves unemployed, homeless and hustling. Others may find themselves working two jobs to pay their bills and spending a lot of additional effort helping a jobless spouse find things to do. If the political turmoil leads to regime change, as it did two decades ago in Russia and Ukraine, and as has happened recently in several North African countries, then the sociocultural changes attendant on political upheaval and the establishment of a new hegemony (if this occurs) may lead to changes in intersubjective exchanges about the proper roles of men and women, and indeed about one’s subjective sense of self as a man or a woman. Similar changes, perhaps magnified in extent, are likely to accrue in the social contexts and self-concepts of those who become deeply involved in or affected by socio-political struggles. And all of this can change the ways in which they and their friends, relatives and neighbors think about, talk about, and behave in relationship to sexual activities and to alcohol and drugs.

Unfortunately, rather than thinking of the epidemic and interventions in terms of contradictions and multilevel processes, most quantitative and qualitative HIV/AIDS researchers have relied on relatively narrow models like social-cognitive and related theories to guide most NIH prevention and adherence research. These models lack effective ways to connect their individual level (and even some social level) variables with larger structural processes such as the socio-economic and related processes that shape periods of economic crisis and socio-political tumult. Further, at their root, they are based on a philosophical idealism (or mentalism) that has difficulty accounting for the changes in material life that take place in periods of social, economic and/or political instability. Put more directly in terms of the CHAT model, they do not conceptualize activity or activity systems as ongoing processes that shape people’s entire lives, but rather focus in on narrow concepts of risk behaviour. Intersubjective exchange is conceptualized in terms of norms, and usually this is treated as perceived norms, rather than as an ongoing interaction process among various members of various reference groups or communities. The “self” is conceptualized in terms of states and traits that characterize how given individuals react to events rather than as a contradictory process with a moving identity that is bound up in the activities and intersubjective exchanges one is part of.

In terms of intervention development, CHAT helps us think about issues that are not adequately addressed by most theories in the HIV intervention field. For example, one of the authors of this article (Friedman) is leading an effort (Project TRIP, for Transmission Reduction Intervention Project) that will integrate social network approaches, the epidemiology of recent and acute HIV infection, and community intervention techniques to try to reduce HIV transmission in several cities. CHAT has helped Project TRIP to think through how it will affect the daily activities of front-line staff and also of the people and networks in which we intervene. Changes in HIV prevention activities due to TRIP are likely to lead staff and community members to change their interpersonal exchanges (and norms) and to develop new ways of viewing their occupational and behavioral-risk activities. Some of these changes may lead to contradictions. For example, in a pilot project in Ukraine that led up to Project TRIP, some components of the intervention conflicted with community norms and the rules that have guided more conventional forms of outreach. These components included asking drug users or sex workers to name the names of people they use drugs with or have sex with, asking them for contact information so we could reach these people, and asking them to help us recruit participants in venues where they meet others to use drugs or meet sex partners. Outreach workers expressed this in terms of community members refusing to supply information about their contacts and venues. CHAT helped us to conceptualize these processes as in part involving a contradiction between the outreach workers’ need for acceptance in the community and their fear that asking these questions would jeopardize this acceptance (and thus both their social relations and employability). Based on this conceptualization, we were able to find ways in which to re-frame the project so as to reduce the perceived risk both to the outreach workers and to community workers they worked with. This suggests that CHAT may help in developing interventions and in translating and disseminating interventions to public health scale programs by making visible contradictions between past practices, expectations and work routines, on the one hand, and the requirements of the new interventions.

MEASURING CHAT-RELEVANT CONCEPTS

Measures have not been developed or applied in HIV/AIDS research for most of the concepts we have been discussing

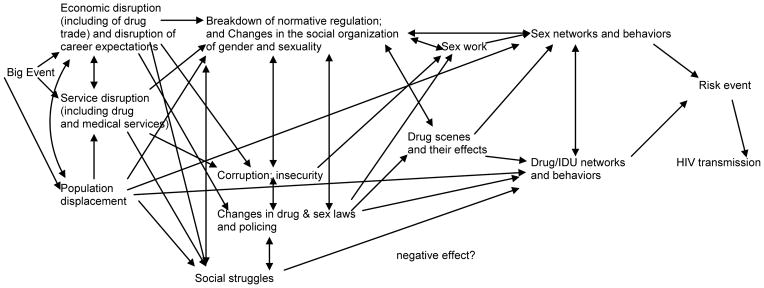

We are working to develop an ethnographically-grounded set of concepts of measures we need, and to develop measures, centered around the core CHAT concepts of 1. activities; 2. intersubjective exchange; or 3. self as a subjective process. We conducted qualitative interviews with IDUs, MSM, and high-risk heterosexuals in order to do this and to write questionnaire items for surveys of these vulnerable groups that began in late 2012. Table 1 presents an overview of the kinds of questions we are trying to develop. Figure 3 puts these in the context of a broad view that brings in both the “big events” and also raises the issue of how the other changes get embodied in ways that affect individuals in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Table 1.

CHAT Concepts and Measures Being Developed

| Concept | Measures |

|---|---|

| Activities |

|

| Intersubjective Exchange |

|

| Self as subjective process |

|

Figure 3.

CHAT in the context of Big Events and in terms of how CHAT processes get embodied in the context of the HIV epidemic

As discussed in the text, our group is developing measures for intersubjective exchanges, activities, and self as a subjective process.

Our emphasis here is on these three sets of concepts and measures

While the other two boxes in Figure 3, dealing with the large-scale processes and with the way in which other parts of the system get embodied, are equally important, they are not focussed on here because concepts and measurements for these are much more available in previous literature. Some, but by no means all, of these other variables are discussed in our previous work (8, 9, 24 – 28) and those of others (29 – 31).

It should be clear that processes of all these kinds interact in specific cases. Thus, big events may lead to increased poverty in a neighborhood. This and the political changes that take place can sometimes lead to changes in how organized criminal groups and impoverished neighborhoods are structured and interact. Poverty and the availability of opportunities facilitated by criminal organizations may lead vulnerable women and children to seek employment as sex workers or in the drug trade. (They may be pressured into these activities by their families or friends, or by gangs.) Such neighborhoods then may also increase in internal solidarity but also develop increased hostility towards outsiders. In such cases, activities, intersubjective exchange and the self as a subjective process interact in ways that can lead to increased vulnerability of women and other less powerful neighborhood members. The measures we discuss below can help us to understand these interacting processes.

We will exemplify these measures very briefly by considering one set of issues from each category from a specific framework: What might we learn if we had measurements of them both before big events like a war or revolution occurred in a locality and two or three years after the events?

1. Activities

Insofar as we are aware, prior to work we are now engaged in, no HIV/AIDS researchers have ever conducted wide-ranging time use surveys of IDUs, MSM, sex workers, or high-risk heterosexuals. Some of our prior work did suggest, however, that these would be important issues to consider:

In our Staying Safe ethnographic study (32, 33) that compared life histories and recent life patterns and behaviors of long-term IDUs who remained uninfected with HIV and HCV with those who were infected, IDUs varied in how their time is structured by regular jobs, by other institutional commitments like methadone clinic visits, or by the heavy time-demands of street hustling to earn money for drugs and other needs. Some IDUs had relatively easy access to money through disability or other payments and thus had considerable unstructured time. Many drug users also structure their time to make sure that they have a “wake-up bag” with which to begin their day, which spares them the need to get drugs at that time under high-risk conditions of incipient withdrawal. In our earlier study of drug-using neighborhoods in Greater Buenos Aires after the economic and political crises of 2001 – 2002, we found that changes in time use due to increased unemployment and other factors were associated with the time drug users and youth in these neighborhoods spent at home, using drugs, or in other venues (34). These varied by gender.

Qualitative interviews conducted as part of our measures development project suggest that the economic downturn in the USA has led to many changes in how at least some MSM, high-risk heterosexuals and drug users who lost their jobs, underwent cutbacks in income maintenance benefits, or lost their housing spend their time—and that this in turn sometimes shapes their sexual partnerships, norms and behaviors. These issues of time also have implications for adherence to HIV related medical care visits and with adherence to antiretroviral therapy (as do instances in which people lost health insurance along with their jobs).

These results suggest that changes in time use may have many effects on HIV risk and protective behaviors. Surveys that showed that time use was changing after big events might thus provide leading indicators of potential HIV problems and allow public health or other actors to head off a potential epidemic.

2. Intersubjective exchange

Intersubjective exchange includes conceptual and normative communication. Many hypothesized pathways by which macrosocial change can affect both risk networks and risk behaviors involve such communication. One such pathway involves the “definition of the situation” (35). Consider Russian children and youth after their country’s transition. Their world had changed greatly from the world they grew up thinking it would be. Instead of a highly-bureaucratic (though often erratic) functioning system, they were faced with economic collapse, widespread alcoholism among adults, and no clear pathway to a stable economic future. As they discussed these problems with each other, these youth came to various definitions of what their world was like and would be like, and of how they might live lives in such a world. For some of them, this meant a world of drugs and sex, including sex for money or other goods or services. And this helped produce an HIV epidemic in the country.

Normative communication involves exchange among friends and relatives (and others) about many issues, including about the number of sex partners one should have, their appropriate personal characteristics, whether one should engage in commercial sex and whether one should attend group sex events. In the Russian case just alluded to, these norms seem to have changed for many small groups, resulting in an abyss between them and others and increasing stigma in Russian society. Looking toward the future, it would be useful to track changes between pre- and post-Big Event periods in normative communication and thus “external norms” (36 – 39) in order to understand why some situations do and others do not precipitate HIV epidemics.

3. Self as a subjective process

These are difficult concepts that go to the heart of dialectics. They deal with how and if people come to take certain actions (including protective or risk behaviors) under changing situations. One aspect of this may involve changes in who they view as being “us” or “them” as macrosocial situations and struggles change—and how this affects how they act. Here, it is not just a question of how they define the situation, but also of how they act in response to it—an area that often may involve considerable individual or small group creativity.

One way we have addressed this in past research involves the notions of altruistic, solidaristic, competitive or hostile orientation towards others—which is one of the sets of concepts for which we are developing measures. We found that HIV+ IDUs had very high levels of consistent condom use in their partnerships with non-IDUs (40). We interpreted this as resulting from altruistic orientations that led them not to want to risk infecting those who were not at high risk otherwise. Subsequent research by our group (41, 42) and others (43, 44) has supported the importance of this phenomenon among drug users and HIV+ MSM. In some cities in the United States, including New York City, solidaristic orientations led to active IDUs and ex-IDUs allying with researchers and some gay activists to set up illegal or quasi-legal syringe exchanges—which was a critical step in reducing HIV transmission (45, 46). Our articles on “intravention” in which IDUs (47 – 49) act to get other people to protect their health show that altruistic/solidaristic orientations to others are widespread among populations likely to be the focus of structural interventions. In a review of data about how altruistic, solidaristic, competitive and hostile orientations to others changed in one community that had seen a parallel decrease in both risk behaviors and in HIV rates over a span of many years, we speculated about how larger-scale events and community interventions affected this process (50). Since our data lacked validated measures of altruistic, solidaristic, competitive and hostile orientations to others, however, we were not able to study either the upstream causes or the behavioral/network correlates of these orientations. Such measures can help us understand how changes in such orientations and response processes affect the HIV epidemic in times of social change.

DISCUSSION

Research and action on the HIV/AIDS epidemic raise many difficult issues. They combine the need for high-quality academic scholarship with the need for effective public action. To a large extent, theory and practice have been framed by relatively narrow (largely individualistic and analytic) perspectives.

This paper, our ongoing theoretical perspectives, and our measurement project, are attempts to broaden these perspectives and to put them within some of the enduring problems of research and action—and in particular, the contradiction between analytic intellectual traditions and tools and a reality that seems to involve moments of non-determined creativity. Such moments of creativity occur in many cases in relation to crises—as when the initial HIV/AIDS epidemic led to grass-roots based responses by oppressed IDUs in New York City before organized science even realized there was a new disease or when gay men and their allies in San Francisco organized STOP AIDS (46, 51, 52). These problems include the fact that statistical methodologies have been developed in terms of deterministic models of prediction. These work well for some physical processes, but have been challenged in relation to their adequacy for some forms of biological, medical and public health research by Levins and Lewontin (53, 54) and by Taylor (5). Agent-based models and network-based discrete event models might help us understand these processes in a less deterministic way.

A related problem is that of measurement—and this is one that we are still wrestling with. Measures like those we are developing are generally meant to work within deterministic statistical and experimental methodologies. They can potentially also be used in agent-based and network-based discrete event models, and in these cases careful analyses of deviant-case outcomes and the processes that led up to them might help us to identify characteristics of actors or patterns of actor characteristics that lead to creativity.

Why are these issues important? In part, it is because the HIV/AIDS epidemic is itself a crisis in some countries and, even within the USA, remains a crisis in some minority impoverished neighborhoods (56).

Furthermore, as science finds new ways to intervene to ameliorate the HIV/AIDS epidemic, this leads to potential contradictions between the needs and worldviews of those managers or researchers at the top who mandate or fund interventions and organizations or individuals who are called upon to carry them out. An example is that ground-level reports from drug user activists in India suggest that the large-scale Avahan intervention may weaken the ability of workers and those at risk to function effectively; and this also poses the issue of how such large-scale interventions can most effectively empower and use the craft skills of front-line workers and community activists. More generally, models with which to think about the interface between an increasingly “biomedicalized” response to the epidemic and its social aspects are a growing concern in the field. CHAT can help us to understand these issues and to improve how both elite and frontline actors respond to them.

In addition, these issues are important because the epidemic takes place within historically changing contexts. These contexts are changing rapidly at the current moment, and are likely to create major socio-political crises in many additional countries in the next 5 to 10 years. Moreover, the crises are already posing risks of major cuts for funding for HIV/AIDS care and prevention—which poses the risk of rebound epidemics and a potential resurgence of AIDS-related mortality in a number of countries and in many neighborhoods within the USA. In a longer-term view, ongoing global warming may both become a big event in its own right and greatly exacerbate AIDS funding cuts by disrupting economies, usurping the political agenda, and drawing youth and others who might have become AIDS activists into working on the climate crisis instead. We would hypothesize, for example, that as global warming gets worse, AIDS funding will decrease. This poses a serious threat to the hopes for an “AIDS-free generation” that were prominently expressed at the 2012 International AIDS Conference in Washington, DC. CHAT, of course, is helpful because it calls our attention to these kinds of phenomena that are out of the sphere of concern for most HIV-related theorizing and planning.

In situations such as those discussed above, the responses to these crises by small groups of those who are at risk socially, economically, epidemiogically and medically may make an enormous difference both to broader historic events and to the future of local and global HIV/AIDS epidemics. At the current moment, we lack the theoretical tools to understand such processes. It is our hope that the ideas in this paper, and the measures we are developing, may help us improve the responses we make to these developing situations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from US National Institute on Drug Abuse projects R01 DA031597 (Developing measures to study how structural interventions may affect HIV) and P30 DA11041 (Center for Drug Use and HIV Research), as well as support from Fogarty International Center/NIH grants through the AIDS International Training and Research Program at Mount Sinai School of Medicine-Argentina Program (Grant # D43 TW001037) and through SUNY-Downstate Medical Center (Grant #D43 TW000233) and by the Buenos Aires University (UBACyT 20020100101021).

References

- 1.Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. Health effects of financial crisis: Omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet. 2011 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pharris A, Wiessing L, Sfetcu O, Hedrich D, Botescu A, Fotiou A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus in injecting drug users in Europe following a reported increase of cases in Greece and Romania, 2011. Euro surveillance. 2011;16(48) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paraskevis D, Nikolopoulos G, Tsiara C, Paraskeva D, Antoniadou A, Lazanas M, et al. HIV-1 outbreak among injecting drug users in Greece, 2011: a preliminary report. Euro surveillance: bulletin europeen sur les maladies transmissibles. European communicable disease bulletin. 2011;16(36) doi: 10.2807/ese.16.36.19962-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brudney K, Dobkin J. Resugent tuberculosis in New York City: Human Immunodeficiency virus, homelessness, and the decline of tuberculosis control programs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:745–747. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuckler D, King LP, Basu S. International Monetary Fund programs and tuberculosis outcomes in post-communist countries. PLoS Medicine / Public Library of Science. 2008 Jul 22;5(7):e143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arinaminpathy N, Dye C. Health in financial crises: economic recession and tuberculosis in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2010 Nov 6;7(52):1559–69. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonovas S, Nikolopoulos G. High-burden epidemics in Greece in the era of economic crisis. Early signs of a public health tragedy. J prev med hyg. 2012;53:169–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman Samuel R, Rossi Diana, Braine Naomi. Theorizing “Big Events” as a potential risk environment for drug use, drug-related harm and HIV epidemic outbreaks. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2009;20:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman Samuel R, Rossi Diana. Dialectical theory and the study of HIV/AIDS and other epidemics. Dialectical Anthropology. 2011;35:403–427. doi: 10.1007/s10624-011-9222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stetsenko A, Arievitch I. The self in cultural-historical activity theory: Reclaiming the unity of social and individual dimensions of human development. Theory and Psychology. 2004;14:475–503. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nleya PTT. Facilitating expansive school transformation using ICT: A Botswana pilot project; GeSCI-PanAf Workshop on Research in ICT Education & Development; Lusaka, Zambia. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth Wolff-Michael, Lee Yew-Jin. Vygotsky’s Neglected Legacy. Cultural-Historical Activity Theory. Review of Educational Research. 2007;77:186–232. doi: 10.3102/0034654306298273. http://rer.sagepub.com/content/77/2/186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellman EM. Doctoral disssertation. University of Birmingham; 2003. The Process and Outcomes of Implementing Peer Mediation Services in Schools: A Cultural-Historical Activity Theory Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards A. Social Policy and Society. 2007;6:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krinsky J, Barker C. Movement strategizing as developmental learning: Perspectives from cultural-historical activity theory. In: Johnson H, editor. Culture, Social Movements, and Protests. Surrey, England: Ashgate; 2009. pp. 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vygotsky LS. In: Mind in society. Cole M, John-Steiner V, Scribner S, Souberman E, editors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leontiev AN. Activity, Consciousness and Personality. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leontiev AN. The problem of activity in psychology. In: Wertsch JV, editor. The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology. Armonk: Sharpe; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engestrom Y. Learning, Working and Imagining: Twelve Studies in Activity Theory. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engeström Yrjö. Learning by Expanding: An Activity/ Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsulit; 1987. (available on the web at http://lchc.ucsd.edu/mca/Paper/Engestrom/expanding/toc.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stetsenko A. Activity as object-related: Resolving the dichotomy of individual and collective types of activity. In: Kaptelinin V, Miettinen R, editors. Mind, Culture, and Activity (Special Issue on the principle of object-relatedness. 1. Vol. 12. 2005. pp. 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stetsenko A. From relational ontology to transformative activist stance: Expanding Vygotsky’s (CHAT) project. Cultural Studies of Science Education. 2008;3:465–485. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stetsenko A, Arievitch I. Cultural-historical activity theory: Foundational worldview and major principles. In: Martin J, Kirschner S, editors. The Sociocultural Turn in Psychology: The Contextual Emergence of Mind and Self. New York: Columbia University Press; 2010. pp. 231–253. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman SR, Kippax SC, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Rossi D, Newman CE. Emerging future issues in HIV/AIDS social research. AIDS. 2006;20:959–960. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000222066.30125.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman SR, Cooper HLF, Osborne A. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African-Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman Samuel R, Rossi Diana, Phaswana-Mafuya Nancy. HIV/AIDS: Global frontiers in prevention/intervention, edited by Cynthia Pope, Renée White, and Robert Malow 2008. New York: Routledge, Inc; 2009. Globalization and interacting large-scale processes and how they may affect the HIV/AIDS epidemic; pp. 491–500. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hacker MA, Leite I, Friedman SR, Carrijo RG, Bastos FI. Poverty, bridging between injecting drug users and the general population, and “interiorization” may explain the spread of HIV in southern Brazil. Health Place. 2009 Jun;15(2):514–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.09.011. Epub 2008 Nov 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts ET, Friedman SR, Brady JE, Pouget ER, Tempalski B, Galea S. Environmental Conditions, Political Economy, and Rates of Injection Drug Use in Large US Metropolitan Areas 1992–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;106(2):142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnett Tony, Whiteside Alan. AIDS in the Twenty-First Century: Disease and Globalization. 2. New York: Palgrave; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson Rachel. From population to HIV: the organizational and structural determinants of HIV outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2011 Sep 27;14(Suppl 2):S6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-S2-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace Deborah, Wallace Rodrick. A Plague on Your Houses: How New York Was Burned Down and National Public Health Crumbled. New York: Verso; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman Samuel R, Sandoval Milagros, Mateu-Gelabert Pedro, Meylakhs Peter, Des Jarlais Don C. Symbiotic Goals and the Prevention of Blood-Borne Viruses among Injection Drug Users. Substance Use and Misuse. 2011;46:307–315. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.523316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mateu-Gelabert P, Sandoval M, Meylakhs P, Wendel T, Friedman SR. Strategies to Avoid Opiate Withdrawal: Implications for HCV and HIV Risks. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2010;21 (3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rossi Diana, Singh Zunino, Dhan, Pawlowicz María Pía, Touzé Graciela, Bolyard Melissa, Mateu-Gelabert Pedro, Sandoval Milagros, Friedman Samuel R. Changes in time-use and drug use by young adults in poor neighbourhoods of Greater Buenos Aires, Argentina, after the political transitions of 2001–2002: Results of a Survey. Harm Reduction Journal. 2011;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumer H. Society as Symbolic Interaction. In: Rose AM, editor. Human Behavior and Social Process: An Interactionist Approach. Houghton-Mifflin; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flom PL, Friedman SR, Jose B, Curtis R. Peer norms regarding drug use and drug selling among household youth in a low income ‘drug supermarket’ urban neighborhood. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2001a;8:219–232. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flom PL, Friedman SR, Kottiri BJ, Neaigus A, Curtis R. Recalled adolescent peer norms towards drug use and drug use in young adulthood in a low-income, minority urban neighborhood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001b;31:425–443. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Brasfield TL, Lemke A, Amidei T, Roffman RE, Hood HV, Smith JE, Kilgore H, McNeill C., Jr Psychological factors that predict AIDS high-risk versus AIDS precautionary behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(1):117–20. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pawlowicz MP, Zunino Singh D, Rossi D, Touzé G, Wolman G, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Flom PL, Mateu-Gelabert P, Friedman SR. Drug use and peer norms among youth in a high-risk drug use neighbourhood in Buenos Aires. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy. 2010 Oct;17(5):544–559. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedman SR, Jose B, Neaigus A, Goldstein M, Curtis R, Ildefonso G, Mota P, Des Jarlais DC. Consistent condom use in relationships between seropositive injecting drug users and sex partners who do not inject drugs. AIDS. 1994;8(3):357–61. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199403000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, et al. Networks, norms, and solidaristic/altruistic action against AIDS among the demonized. Sociological Focus. 1999;32:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Des Jarlais DC, Perlis T, Arasteh K, Hagan H, Milliken J, Braine N, Yancovitz S, Mildvan D, Perlman DC, Maslow C, Friedman SR. Informed altruism” and “partner restriction” in the reduction of HIV infection in injecting drug users entering detoxification treatment in New York City, 1990–2001. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(2):158–66. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200402010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Dell BL, Rosser BR, Miner MH, Jacoby SM. HIV prevention altruism and sexual risk behavior in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2008 Sep;12(5):713–20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9321-9. Epub 2007 Nov 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Convey MR, Julia Dickson-Gomez, Weeks MR, Li J. Altruism and Peer-Led HIV Prevention Targeting Heroin and Cocaine Users. Qual Health Res. doi: 10.1177/1049732310375818. First published on July 16, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Booth Robert E, Des Jarlais Don C, Friedman Samuel R. Reflections on 25 Years of HIV and AIDS Research among Drug Abusers. Journal of Drug Issues. 2009;39:209–222. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman Samuel R, de Jong Wouter, Rossi Diana, Touzé Graciela, Rockwell Russell, Des Jarlais Don C, Elovich Richard. Harm reduction theory: Users culture, micro-social indigenous harm reduction, and the self-organization and outside-organizing of users’ groups. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007b;18:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedman SR, Maslow C, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Mateu-Gelabert P, Neaigus A. Urging others to be healthy: “Intravention” by injection drug users as a community prevention goal. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:250–263. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.250.35439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman SR, Bolyard M, Maslow C, Mateu-Gelabert P, Sandoval M. Harnessing the power of social networks to reduce HIV risk. Focus. 2005;20(1):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mateu-Gelabert P, Bolyard M, Maslow C, Sandoval M, Flom PL, Friedman SR. For the Common Good: A method to measure residents’ efforts to protect their community from drug and sex related harm. SAHARA Journal. 2008;5:144–157. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2008.9724913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedman SR, Mateu-Gelabert P, Curtis R, Maslow C, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Flom PL. Social capital or networks, negotiations and norms? A neighborhood case study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007a;32(6S):S160–S170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.005. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1995560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wohlfeiler D. Structural and environmental HIV prevention for gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2000;14(Supplement 1):S52–S56. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wohlfeiler D. From community to clients: the professionalisation of HIV prevention among gay men and its implications for intervention selection. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(Supplement 1):i176–i182. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levins Richard, Lewontin Richard. The Dialectical Biologist. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewontin Richard, Levins Richard. Biology under the Influence: Dialectical Essays on Ecology, Agriculture, and Health. New York: Monthly Review Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor Peter. Unruly Complexity: Ecology, Interpretation, and Engagement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Sadr Wafaa M, Mayer Kenneth H, Hodder Sally L. AIDS in America--forgotten but not gone. N Engl J Med. 2010 Mar 18;362(11):967–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000069. Published online 2010 February 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]