Abstract

We present a resistive network model, protein assay data, and outlook of the giant magnetoresistive (GMR) spin-valve magneto-nanosensor platform ideal for multiplexed detection of protein biomarkers in solutions. The magneto-nanosensors are designed to have optimal performance considering several factors such as sensor dimension, shape anisotropy, and magnetic nanoparticle tags. The resistive network model indicates that thinner spin-valve sensors with narrower width lead to higher signals from magnetic nanoparticle tags. Standard curves and real-time measurements showed a sensitivity of ~10 pM for phosphorylated-structural maintenance of chromosome 1 (phosphor-SMC1), ~53 fM for granulocyte colony stimulation factor (GCSF), and ~460 fM for interleukin-6 (IL6), which are among the representative biomarkers for radiation exposure and cancer.

Keywords: Radiation biomarker, Cancer biomarker, Nanosensor, Magnetic nanoparticles, Immunoassay

1 Introduction

Recent advances in nanotechnology and microdevices have paved the way for many attractive applications in both fundamental science and practical use. (Whitesides 2005; Appell 2002; Farokhzad and Langer 2009; Desai et al. 1999) Especially, nanobiotechnology, which grafts the nanotechnology onto biology, is one of the most important research areas due to its potential to understand biological phenomena at the nanoscale and to create novel tools for dealing with diverse biological issues. Among various fields of nanobiotechnology, ultra-sensitive nanobiosensor platforms (Baselt et al. 1998; Haes et al. 2005) have been pursued for decades, with noble goals ranging from providing diagnostic devices for early detection of diseases to enabling personalized treatments based on accurate therapy efficacy prediction and/or prognosis of complex diseases (Pepe et al. 2001; Wulfkuhle et al. 2003). For example, several biosensors built with nanomaterials have been reported to detect analytes at very low concentrations (Zheng et al. 2005; Pattani et al. 2008) or even at the single-molecule level (Howorka and Siwy 2009), and some of them could detect different analytes at the same time in a multiplex manner (Zheng et al. 2005; Osterfeld et al. 2008; Gaster et al. 2009; Fan et al. 2008). If combined with microfluidic set-up, these nanobiosensors are also capable of diagnosing various physiological and pathological conditions in a tiny volume of a sample (Choi et al. 2001; Fan et al. 2008).

The magneto-nanosensor biochip is a biosensing platform which has several advantages over conventional techniques. First, it has a higher sensitivity. More specifically, the obtained signals in magneto-nanosensors are not interfered with background signals, and thus have higher signal-to-noise ratio. This is possible because the signal generation mechanism is based on the magnetism, and most of the biological species are inherently non-magnetic (Wang and Li 2008). In contrast, signals in fluorescence-based biosensing, for instance, are often convoluted with signals from autofluorescent molecules coexisting in a sample (van de Lest et al. 1995; Gaster et al. 2009). Second, it is relatively easy to integrate with electric read-out system which is quite advantageous for the development of hand-held devices (Gaster et al. 2011b). Magneto-nanosensors, such as GMR or magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) sensors, usually rely on generating electrical signals in themselves. Therefore, data conversion process from optical to electrical signal is not necessary. Third, it is scalable. The GMR and MTJ sensors already have been successfully applied in hard disk drives and magnetic memories for a long time (Daughton 1999; Wang and Li 2008). Therefore, mass production at a low cost is feasible with the aid of the cutting-edge microfabrication technology currently available in the industry.

We have demonstrated the magneto-nanosensor biochips made of arrays of GMR spin-valves for ultra-sensitive, multiplex, and buffer-independent detection of protein biomarkers (Xu et al. 2008; Osterfeld et al. 2008; Gaster et al. 2009; Gaster et al. 2011a). Signals are generated in real-time as a form of resistance changes of the spin-valve sensors induced by the stray magnetic field from subsequently added superparamagnetic nanoparticles. In this paper, we briefly review the structure of the magneto-nanosensor biochip and discuss the possibility of device optimization to improve its sensitivity by using a newly developed analytical resistive network model. Following the review on the requirements of the magnetic nanoparticles for bioassay, we present measurement data for phosphor-SMC1, GCSF, and IL6 which are among the representative biomarkers for radiation exposure and cancer.

2 Modeling of magneto-nanosensors

2.1 Structure of the magneto-nanosensor biochip

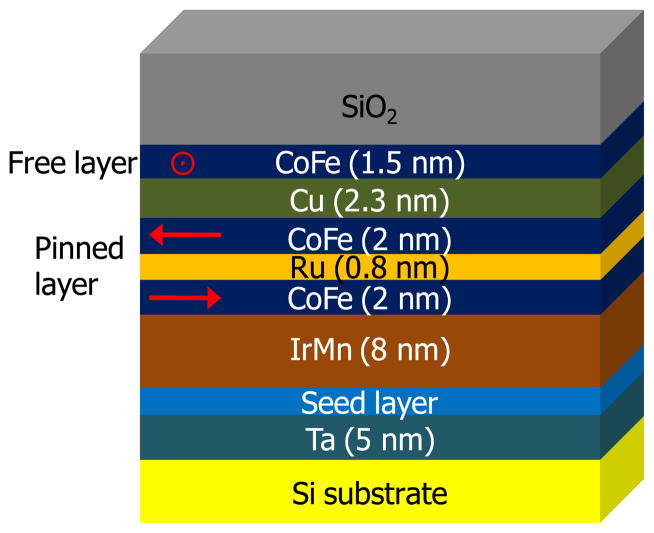

The magneto-nanosensor biochip used here and also reported in recent years typically has a total of 64 sensors which are individually addressable, and each of the sensors is made of an array of 48 spin-valve strips. Figure 1 illustrates a representative multi-layered thin film structure of the spin-valves used in the magneto-nanosensor biochips. The lower two CoFe layers are coupled anti-ferromagnetically by using Ru spacer layer of an appropriate thickness. Shape anisotropy originated from its elongated shape holds the orientation of the magnetic moments to the in-plane direction. Their magnetic moments are fixed (or pinned) by the antiferromagnetic IrMn layer. The magnetic moment orientation of the upper CoFe layer (free layer) is not fixed, and is subject to change from its initial alignment, which is orthogonal to that of the pinned layer, in response to the externally applied magnetic field or the stray magnetic field from added magnetic nanoparticles in solution. The resulting relative difference in the orientation of the magnetic moments between magnetically pinned layer and free layer induces the resistance change across the Cu spacer layer of the spin-valves through the GMR effect, whose discovers were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2007.

Fig 1.

Multilayer thin film structure of the magneto-nanosensor. Red arrows indicate the orientations of magnetic moment in CoFe layers. Magnetic orientations of the pinned layer are coupled antiferromagnetically. Magnetic orientation of the free layer is initially orthogonal to that of the pinned layer and is free to rotate in response to changes in the external magnetic field

2.2 Resistive network model of GMR spin-valve nanosensor

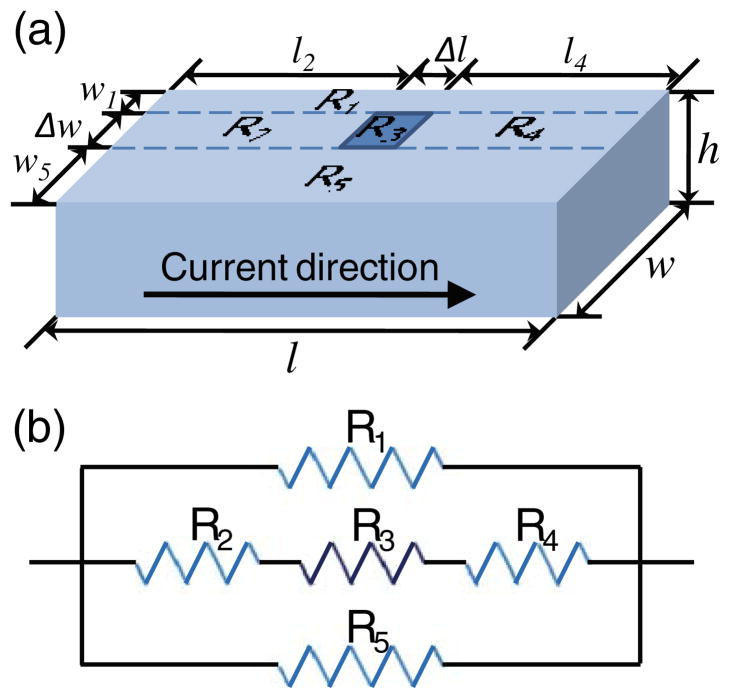

Factors that affect the sensitivity of the spin-valve sensors can be examined by a resistive network model. A schematic is shown in Fig. 2(a). In this model, a spin-valve strip with a dimension of l (length)×w (width)×h (height) is regarded as a combination of five resistors. The spin-valve is fed with a constant current. According to the Ohm’s law, therefore, a voltage change corresponding to the resistance change of the spin-valve accompanies when a magnetic nanoparticle binds to the surface and affects the magnetization state of the spin-valve with its stray magnetic field. If we say the area where a magnetic nanoparticle is bound has a size of Δl×Δw and has a resistivity change of Δρ, then the spin-valve can be described as a circuit which is a parallel connection of two individual resistors (R1 and R5) and three series resistors (R2, R3, and R4) (Fig. 2(b)). The overall resistance of the circuit is:

| (1) |

Fig 2.

(a) An illustration describing the spin-valve strip of the magneto-nanosensor. The strip has a dimension of l (length)×w (width)×h (height). Current flows from left to right. When a magnetic nanoparticle with a size of Δl×Δw is bound to the surface, resistivity of the underlying material is changed. (b) A resistance circuit diagram of the spin-valve strip when a magnetic nanoparticle is bound to the sensor surface. R3 has a changed resistivity affected by the magnetic nanoparticle

Since the electrical resistance is directly proportional to the resistivity and the length of the material while it is also inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area, , where ρ is resistivity, l is length, and A is cross-sectional area (w×h), respectively, we can write:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

By plugging Eqs. (2) to (4) into Eq. (1):

where , which is the initial resistance of the spin-valve. ΔR = Rnew − R0

Using the Taylor series for small x,

| (5) |

As the magnetic nanoparticles used in our assay has a size (Δl and Δw) of around 50 nm, whereas the length (l) and width (w) of the sensor is 90 μm and 0.75 μm, respectively, both and are substantially smaller than 1. Consequently, we can further simplify the Eq. (5).

| (6) |

As can be inferred from the Eq. (6), we can figure out several factors to maximize the resistance change (ΔR) and thus the signal of the spin-valve sensor. First, it is better to have the thickness (h) and width (w) of the sensor as small as possible. Actually, the spin-valve sensors in our biochip also have a thickness of only a few nanometers and a relatively much narrow width compared with the length. Second, given that Δl×Δw is the particle size, large magnetic nanoparticles increase ΔR more than smaller nanoparticles; alternatively, a large surface coverage of identical magnetic nanoparticles increases ΔR more than a smaller coverage. Finally, magnetic nanoparticles and sensors made of materials that maximize the increase in resistivity (large Δρ) are desirable. However, because of several issues related to the magnetic nanoparticles such as dispersibility, kinetics, surface coverage density, and sensor noise, there are restrictions in the choice of particle size, particle material, and sensor material, which have to be optimized by design and experimentation in a systematic manner. The restrictions on magnetic nanoparticles will be presented next.

2.3 Magnetic nanoparticle requirements for magneto-nanosensor

Magnetic nanoparticles have been extensively studied for many interesting biological applications like magnetic separation of cells or biomolecules (Kim et al. 2009; Molday et al. 1977), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast enhancement (Nitin et al. 2004; Smith et al. 2007; Sun et al. 2008), targeted drug delivery system (Sun et al. 2008; Dobson 2006), and hyperthermia (Hsu and Su 2008; Thiesen and Jordan 2008). In magneto-nanosensor biochip applications, the magnetic nanoparticles are used as labeling tags. Although magnetic nanoparticles of large size can generate a higher signal, as mentioned previously, there are several other requirements which limit the maximum size of the particles in practical use.

The first thing to consider is the dispersibility of the nanoparticles. Dispersibility is a concept regarding how well particles can remain stable in a solution without precipatation. Precipitated particles are less useful as labeling tags in an assay due to their greatly reduced accessibility to the binding location. Even worse, they can precipitate to sensor surface and produce non-specific signals unrelated to analyte binding. Since the magnetic nanoparticles are composed of inorganic materials which usually are not colloidally stable in many biological solutions, there have been a lot of studies to improve their dispersibility (Mackay et al. 2006; Cheng et al. 2005). One of the most successful techniques is coating the nanoparticles with hydrophilic polymer (Harris et al. 2003). Thermodynamically, in order to make a stable dispersion, the mixing of nanoparticles to a solution should have a negative Gibb’s free energy of mixing, which can be achieved by increasing the mixing entropy. Therefore, for hydrophilic polymer-coated nanoparticles, a large conformational degree of freedom harnessed by the polymeric segments stretched out in solution enables the enhanced dispersibility.

However, even if it is possible to disperse large-sized nanoparticles stably, the size of the nanoparticles should match that of biomolecules so that the binding of a nanoparticle does not block other available binding sites on the labeled moieties. Moreover, the magneto-nanosensors operates as proximity-based detectors of the dipole fields from the magnetic nanoparticles, so only particles within ~150 nm from the sensor surface are detectable (Gaster et al. 2011c). Another subtlety not appreciated widely is that large sized magnetic nanoparticles tend to have a slow diffusivity, which may be detrimental to the kinetic binding process and lead to a slow assay. Finally, magnetic interactions between themselves also need to be considered. In general, superparamagnetic nanoparticles (usually have to be in tens of nanometer scale or less) are preferred because they do not have fixed magnetic orientation at room temperature, and thus they do not attract other magnetic nanoparticles. Otherwise, they would grow in size by aggregating with each other and eventually precipitate out of solution, which is often observed for ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic nanoparticles (Kim et al. 2009).

Considering all these together, we chose to use streptavidin-coated magnetic nanoparticles (Miltenyi, streptavidin-MicroBeads) which are small cluster of 10 nm-sized iron-oxide nanoparticles incorporated in a dextran polymer matrix and have an overall size of about 50 nm in average (Gaster et al. 2011c). Although the overall size is somewhat larger than the size of antibodies used in the immunoassay, they are still usable because captured analytes (binding sites) are spaced sparsely under low concentrations of interest. By using this cluster form of magnetic nanoparticles, we could take the advantage of the large particle size while keeping the size of individual iron-oxide nanoparticle from exceeding superparamagnetic limit (~20 nm) (Kovalenko et al. 2007; Klokkenburg et al. 2004). Furthermore, the dextran coating is bio-compatible as well as hydrophilic (De Groot et al. 2001). Accordingly, the chosen magnetic nanoparticles are very suitable for the magneto-nanosensor bioassay, which is one of the enabling factors in realizing the ultra-sensitive detection of target analytes.

3 Experiments for diagnostics of radiation exposure and cancer

3.1 Materials

Anti-mouse IL6 antibody, biotinylated anti-mouse IL6 antibody (all from R&D systems, DY406), anti-mouse GCSF antibody, biotinylated anti-mouse GCSF antibody (all from R&D systems, DY414), anti-human phosphor-SMC1 antibody, biotinylated anti-human phosphor-SMC1 antibody, poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (Polyscience), poly(ethylene-alt-maleic anhydride) (Aldrich), 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Invitrogen), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (Thermo scientific), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (Aldrich), 1 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Aldrich), biotinylated bovine serum albumin (biotin-BSA) (Pierce), Tween 20 (Aldrich), and streptavidin-coated MicroBeads (Miltenyi, 130-048-101) were used as received without further purification.

3.2 Magneto-nanosensor biochip assay protocol

The biochip was washed thoroughly with acetone, methanol, and isopropanol. After additional cleaning with oxygen plasma for 3 min, the biochip surface was coated with 1 % aqueous solution of poly(allylamine hydrochloride) for 5 min, and rinsed with deionized water. The biochip was then baked at 120 °C for 1 h. The chip surface was coated again with 2 % aqueous solution of poly(ethylene-alt-maleic anhydride) for 5 min. After rinsing with deionized water, the chip surface was immersed in a mixture solution of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride and N-hydroxysuccinimide for activation. Capture antibody, biotin-BSA, and BSA deposition on the chip surface was performed using a robotic spotter (Scienion, sciFlexarrayer). The sensor chip was then stored in 4 °C humidity chamber overnight. After washing the biochip surface with a washing buffer (0.1 % BSA and 0.05 % Tween 20 in PBS), surface blocking was done using 1 % BSA solution for 1 h. Following the phosphor-SMC1, GCSF, or IL6 solution incubation on the biochip for 2 h, the surface was washed and a detection antibody solution with a concentration of 5 μg/ml was added. The surface was washed again after 1 h, and the biochip was placed in the biochip reader station implemented according to a previously reported method (Hall et al. 2010). Finally, streptavidin-coated magnetic nanoparticles (Miltenyi, streptavidin-Microbeads) were added to generate signals.

3.3 Magneto-nanosensor biochip assay performance

Using the magneto-nanosensor biochips, and after very careful assay development, we measured the standard curves of phosphor-SMC1, IL6, and GCSF. SMC1 is deeply involved in choromosome dynamics in that it is a member of cohesion complexes which play crucial roles for maintaining sister chromatid cohesion after DNA replication (Lam et al. 2005; Ishiguro et al. 2011). As it is known that SMC1 is phosphorylated after exposure to ionizing radiation, the phosphor-SMC1 works as a radiation biomarker (Ivey et al. 2011). IL6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that regulates innate immunity and acute-phase response (Sadagurski et al. 2010). Therefore, elevated levels of IL6 and its accompanying acute-phase protein, such as C-reactive protein, have been observed for active and/or terminal diseases including cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and certain types of cancer (van Zaanen et al. 1996; Cole et al. 2010). GCSF is a colony-stimulating factor hormone. It is a glycoprotein, growth factor, and cytokine produced by a number of different tissues. Its main function is to stimulate the bone marrow to produce granulocytes and stem cells, and then to release them into blood. GCSF expression level is often associated with cancer or cancer treatment, and GCSF has also been used in cancer therapeutics. (Demetri and Griffin 1991; Aritomi et al. 1999)

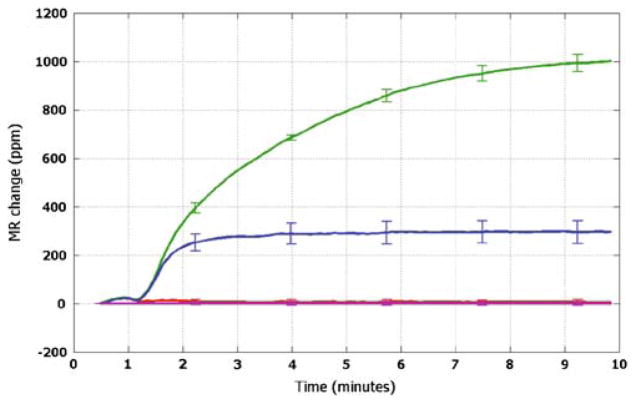

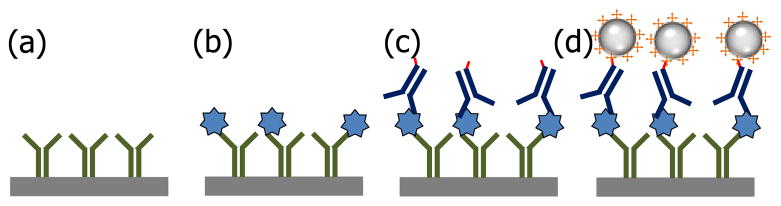

Figure 3 illustrates the detection scheme of the magneto-nanosensor biochip immunoassay. Similar to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the assay relies on a sandwich structure where target analyte is captured in between capture and detection antibodies. The capture antibodies were covalently immobilized on the sensor surface, and the detection antibodies were biotinylated in advance so that they could be labeled by streptavidin-tagged magnetic nanoparticles later. As a result of the GMR effect, signals were generated in real-time by adding magnetic nanoparticles and applying external oscillating magnetic field. A typical binding curve for PBS solution of 500 pM phosphor-SMC is presented in Fig. 4. Signals from capture antibody-coated (blue), biotin-BSA-coated (green), BSA-coated (red), and epoxy-covered (purple) sensors were measured. Biotin-BSA-coated sensors were used as positive control sensors because biotin has an ability to capture streptavidin-tagged magnetic nanoparticles. As expected, they showed large signals unaffected by the analyte concentrations. On the contrary, negative control sensors coated with BSA showed very small signals, clearly indicating that the obtained signals from the capture antibody-coated sensors did not come from the non-specific binding of analytes or magnetic nanoparticles. Epoxy-covered sensors were excluded from all the binding events. Hence, they worked as electrical reference.

Fig 3.

A schematic of magneto-nanosensor biochip immunoassay. (a) Capture antibodies (green) are immobilized on the sensor surface (gray). (b) Target antigens (blue) are captured by the antibodies. (c) Detection antibodies (navy) which is biotinylated (red) are added to form sandwich structure. (d) Binding of streptavidin-coated (orange) magnetic nanoparticles induces the resistance change of the spin-valve magneto-nanosensor and generates signal

Fig 4.

A binding curve measured for a solution of 500 pM phosphor-SMC1. Signals from epoxy-covered (purple), BSA-coated (red), biotin-BSA-coated (green), and phosphor-SMC1 capture antibody-coated (blue) sensors are shown. Error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation

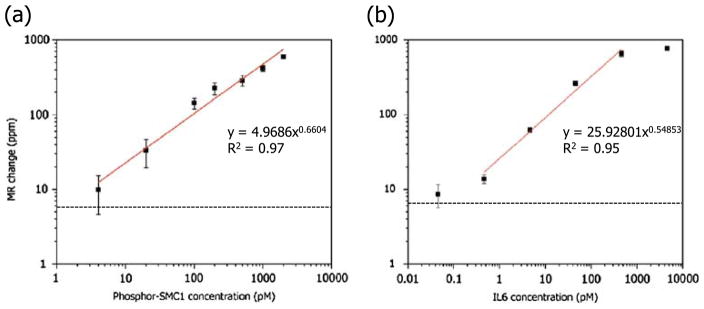

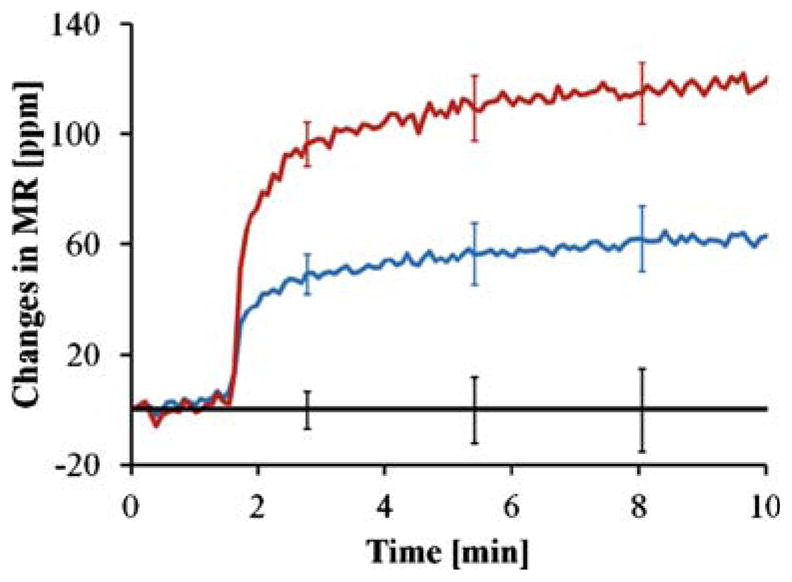

Figure 5(a) shows the standard curve of the phosphor-SMC1 on a double-logarithmic scale together with the best-fit curve and correlation coefficients. It has a linear range of more than two orders of magnitude (10~2,000 pM) with an R2 value of 0.97. On the other hand, the linear range of the IL6 standard curve is larger than three orders of magnitude (0.46~460 pM) with an R2 value of 0.95 (Fig. 5(b)). For GCSF (data not shown), the linear dynamic range is more than four orders of magnitude (53 fM~0.53 nM). The GCSF assay is both sensitive and specific, as shown in Fig. 6. Real-time binding curve (red) of the assay at a concentration of 1 pg/ml (53 fM) indicate the assay is very sensitive and fast (read-out can be done in minutes); the low signal level (blue curve) of BSA coated sensors (negative controls) indicates the assay is specific, and near-zero level of the epoxy-covered sensors (electrical reference) indicate the biochip and reader station function properly. These assay results were obtained from measurements where each biomarker was spiked in various concentrations into PBS. Although there is no commercially available phosphor-SMC1 ELISA kit using the same capture and detection antibodies that were used on our magneto-nanosensor biochip assay to compare, the IL6 standard curve obtained using the magneto-nanosensor showed a lower detection limit (0.46 versus 0.69 pM for magneto-nanosensor and R&D systems DY406 ELISA kit, respectively) and a wider linear range at higher concentrations than that of commercial ELISA kit (460 versus 46 pM for magneto-nanosensor and R&D systems DY406 ELISA kit, respectively). For GCSF assay, R&D DY414 mouse GCSF immunoassay reports a sensitivity of ~20 pg/ml and a dynamic range of 20~2000 pg/ml, so the performance of magneto-nanosensors is very favorable in comparison.

Fig 5.

Standard curves measured on magneto-nanosensor biochip for (a) phosphor-SMC1 and (b) IL6. Each tiny square represents a data point. Error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation. Red lines are best fit power curves. Black dotted lines are zero-analyte signals measured without any target analyte in solution

Fig 6.

Real-time binding curve (red) of GCSF assay at a concentration of 1 pg/ml (53 fM); the blue curve is that of BSA-coated sensors (negative controls), and the black one is that of epoxy-covered sensors (electrical reference). Error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation

4 Conclusion

In summary, we have developed the GMR spin-valve magneto-nanosensor platform that can be used to detect protein biomarkers in an immunoassay. Factors affecting the performance of the magneto-nanosensor and the requirements of magnetic nanoparticles for the biochips are discussed. Assay results for phosphor-SMC1, GCSF, and IL6, which are among the representative biomarkers for radiation exposure and cancer, have been obtained in real-time measurements. Our data indicate that the magneto-nanosensor biochip holds great potential for sensitive detection of protein biomarkers, which may enable early stratification and therapy monitoring of patients with exposure to ionizing radiation and patients harboring cancer or other deadly diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Richard G. Ivey at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle for his generous support of phosphor-SMC1 antibodies and standard. This work was supported, in part, by the United States National Institute of Health (grants U54CA143907, U54CA151459, R21AI085566, and R33CA138330), the United States National Science Foundation (grant ECCS-0801385-000), a Gates Foundation Grand Challenge Exploration Award, and Stanford Bio-X Program.

Abbreviations

- phosphor-SMC1

Phosphorylated-structural maintenance of chromosome 1

- GCSF

Granulocyte colony stimulation factor

- IL6

Interleukin-6

- GMR

Giant magnetoresistance

- MTJ

Magnetic tunnel junction

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Contributor Information

Dokyoon Kim, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Jung-Rok Lee, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Eric Shen, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Shan X. Wang, Email: sxwang@stanford.edu, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA. Department of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA

References

- Appell D. Wired for success. Nature. 2002;419:553–555. doi: 10.1038/419553a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aritomi M, Kunishima N, Okamoto T, Kuroki R, Ota Y, Morikawa K. Atomic structure of the GCSF-receptor complex showing a new cytokine-receptor recognition scheme. Nature. 1999;401:713–717. doi: 10.1038/44394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselt DR, Lee GU, Natesan M, Metzger SW, Sheehan PE, Colton RJ. A biosensor based on magnetoresistance technology. Biosens Bioelectron. 1998;13:731–739. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(98)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F-Y, Su C-H, Yang Y-S, Yeh C-S, Tsai C-Y, Wu C-L, Wu M-T, Shieh D-B. Characterization of aqueous dispersions of Fe3O4 nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J-W, Oh KW, Han A, Okulan N, Wijayawardhana CA, Lannes C, Bhansali S, Schlueter KT, Heineman WR, Halsall HB, Nevin JH, Helmicki AJ, Henderson HT, Ahn CH. Development and characterization of microfluidic devices and systems for magnetic bead-based biochemical detection. Biomed Microdevices. 2001;3(3):191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Arevalo JMG, Takahashi R, Sloan EK, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Sheridan JF, Seeman TE. Computational identification of gene-social environment interaction at the human IL6 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(12):5681–5686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911515107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton JM. GMR applications. J Magn Magn Mater. 1999;192:334–342. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot CJ, Van Luyn MJA, Van Dijk-Wolthuis WNE, Cadée JA, Plantinga JA, Otter WD, Hennink WE. In vitro biocompatibility of biodegradable dextran-based hydrogels tested with human fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetri GD, Griffin JD. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and its receptor. Blood. 1991;78(11):2791–2808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai TA, Hansford DJ, Kulinsky L, Nashat AH, Rasi G, Tu J, Wang Y, Zhang M, Ferrari M. Nanopore technology for biomedical applications. Biomed Microdevices. 1999;2(1):11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J. Magnetic nanoparticles for drug delivery. Drug Develop Res. 2006;67:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fan R, Vermesh O, Srivastava A, Yen BKH, Qin L, Ahmad H, Kwong GA, Liu C-C, Gould J, Hood L, Heath JR. Integrated barcode chips for rapid, muplexed, analysis of proteins in microliter quantities of blood. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(12):1373–1378. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Impact of nanotechnology on drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2009;3(1):16–20. doi: 10.1021/nn900002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaster RS, Hall DA, Nielsen CH, Osterfeld SJ, Yu H, Mach KE, Wilson RJ, Murmann B, Liao JC, Gambhir SS, Wang SX. Matrix-insensitive protein assays push the limits of biosensor in medicine. Nat Med. 2009;15:1327–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm.2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaster RS, Hall DA, Wang SX. Autoassembly protein assays for analyzing antibody cross-reactivity. Nano Lett. 2011a;11(7):2579–2583. doi: 10.1021/nl1026056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaster RS, Hall DA, Wang SX. nanoLAB: an ultraportable, handheld diagnostic laboratory for global health. Lab Chip. 2011b;11:950–956. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaster RS, Xu L, Han S-J, Wilson RJ, Hall DA, Osterfeld SJ, Yu H, Wang SX. Quantification of protein interactions and solution transport using high-density GMR sensor arrays. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011c;6:314–320. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haes AJ, Chang L, Klein WL, Van Duyne RP. Detection of a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease from synthetic and clinical samples using a nanoscale optical biosensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2264–2271. doi: 10.1021/ja044087q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DA, Gaster RS, Lin T, Osterfeld SJ, Han S, Murmann B, Wang SX. GMR biosensor arrays: a system perspective. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;25(9):2051–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LA, Goff JD, Carmichael AY, Riffle JS, Harburn JJ, St Pierre TG, Saunders M. Magnetite nanoparticle dispersions stabilized with triblock copolymers. Chem Mater. 2003;15:1367–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Howorka S, Siwy Z. Nanopore analytics: sensing of single molecules. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2360–2384. doi: 10.1039/b813796j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M-H, Su Y-C. Iron-oxide embedded solid lipid nanoparticles for magnetically controlled heating and drug delivery. Biomed Microdevices. 2008;10:785–793. doi: 10.1007/s10544-008-9192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro K-I, Kim J, Fujiyama-Nakamura S, Kato S, Watanabe Y. A new meiosis-specific cohesin complex implicated in the cohesin code for homologous pairing. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(3):267–275. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey RG, Moore HD, Voytovich UJ, Thienes CP, Lorentzen TD, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Frayo S, Izaguirre VK, Lundberg SJ, Hedin L, Badiozamani KR, hoofnagle AN, Stirewalt DL, Wang P, Georges GE, Gopal AK, Paulovich AG. Blood-based detection of radiation exposure in humans based on novel phospho-Smc1 ELISA. Radiat Res. 2011;175(3):266–281. doi: 10.1667/RR2402.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Lee N, Park M, Kim BH, An K, Hyeon T. Synthesis of uniform ferrimagnetic magnetite nanocubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(2):454–455. doi: 10.1021/ja8086906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klokkenburg M, Vonk C, Claesson EM, Meeldijk JD, Erné BH, Philipse AP. Direct imaging of zero-field dipolar structures in colloidal dispersions of synthetic magnetite. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16706–16707. doi: 10.1021/ja0456252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko MV, Bodnarchuk MI, Lechner RT, Hesser G, Schäffler F, Heiss W. Fatty acid salts as stabilizers in size- and shape-controlled nanocrystal synthesis: the case of inverse spinel iron oxide. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6352–6353. doi: 10.1021/ja0692478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WS, Yang X, Makaroff CA. Characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana SMC1 and SMC3: evidence that AtSMC3 may function beyond chromosome cohesion. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(14):3037–3048. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay ME, Tuteja A, Duxbury PM, Hawker CJ, Van Horn B, Guan Z, Chen G, Krishnan RS. General strategies for nanoparticle dispersion. Science. 2006;311:1740–1743. doi: 10.1126/science.1122225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molday RS, Yen SPS, Rembaum A. Applications of magnetic nanospheres in labelling and separation of cells. Nature. 1977;268(4):437–438. doi: 10.1038/268437a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitin N, LaConte LEW, Zurkiya O, Hu X, Bao G. Functionalization and peptide-based delivery of magnetic nanoparticles as an intracellular MRI contrast agent. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:706–712. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterfeld SJ, Yu H, Gaster RS, Caramuta S, Xu L, Han S-J, Hall DA, Wilson RJ, Sun S, White RL, Davis RW, Pourmand N, Wang SX. Multiplex protein assays based on real-time magnetic nanotag sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(52):20637–20640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810822105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattani VP, Li C, Desai TA, Vu TQ. Microcontact printing of quantum dot bioconjugate arrays for localized capture and detection of biomolecules. Biomed Microdevices. 2008;10:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson ML, Thornquist M, Winget M, Yasui Y. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer I. 2001;93(14):1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadagurski M, Norquay L, Farhang J, D’Aquino K, Copps K, White MF. Human IL6 enhances leptin action in mice. Diabetologia. 2010;53:525–535. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1580-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BR, Heverhagen J, Knopp M, Schmalbrock P, Shapiro J, Shiomi M, Moldovan NI, Ferrari M, Lee SC. Localization to atherosclerotic plaque and biodistribution of biochemically derivatized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) contrast particles for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Biomed Microdevices. 2007;9:719–727. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Lee JSH, Zhang M. Magnetic nanoparticles in MR imaging and drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2008;60:1252–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiesen B, Jordan A. Clinical applications of magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia. Int J Hyperthermia. 2008;24(6):467–474. doi: 10.1080/02656730802104757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Lest CHA, Versteeg EMM, Veerkamp JH, van Kuppevelt TH. Elimination of autofluorescence in immunofluorescence microscopy with digital image processing. J Histochem Cytochem. 1995;43(7):727–730. doi: 10.1177/43.7.7608528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zaanen HCT, Koopmans RP, Aarden LA, Rensink HJAM, Stouthard JML, Warnaar SO, Lokhorst HM, van Oers MHJ. Endogenous interleukin 6 production in multiple myeloma patients treated with chimeric monoclonal anti-IL6 antibodies indicates the existence of a positive feed-back loop. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(6):1441–1448. doi: 10.1172/JCI118932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SX, Li G. Advances in giant magnetoresistance biosensors with magnetic nanoparticle tags: review and outlook. IEEE Trans Magn. 2008;44(7):1687–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Whitesides GM. Nanoscience, nanotechnology, and chemistry. Small. 2005;1(2):172–179. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfkuhle JD, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Proteomic applications for the early detection of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:267–275. doi: 10.1038/nrc1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Yu H, Akhras MS, Han S-J, Osterfeld S, White RL, Pourmand N, Wang SX. Giant magnetoresistive biochip for DNA detection and HPV genotyping. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Patolsky F, Cui Y, Wang WU, Lieber CM. Multiplexed electrical detection of cancer markers with nanowire sensor arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(10):1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/nbt1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]