Abstract

Background

In pediatric tumor xenograft models, tumor-derived IGF-2 results in intrinsic resistance to IGF-1R-targeted antibodies, maintaining continued tumor angiogenesis. We evaluated the anti-angiogenic activity of a ligand-binding antibody (MEDI-573) alone or in combination with IGF-1 receptor binding antibodies (MAB391, CP01-B02).

Methods

IGF-stimulated signaling was monitored by increased Akt phosphorylation in sarcoma and human umbilical chord vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). Angiogenesis was determined in vitro using capillary tube formation in HUVECs and in vivo using a VEGF-stimulated Matrigel assay. Tumor growth delay was examined in four sarcoma xenograft models

Results

The IGF-ligand binding antibody MEDI-573 suppressed Akt phosphorylation induced by exogenous IGF-1 and IGF-2 in sarcoma cells. Receptor binding antibodies suppressed IGF-1 stimulation of Akt phosphorylation, but IGF-2 circumvented this effect and maintained HUVEC tube formation. MEDI-573 inhibited HUVEC proliferation and tube formation in vitro, but did not inhibit angiogenesis in vivo, probably because MEDI-573 binds murine IGF-1 with low affinity. However, in vitro the anti-angiogenic activity of MEDI-573 was also circumvented by human recombinant IGF-1. The combination of receptor- and ligand-binding antibodies completely suppressed VEGF-stimulated proliferation of HUVECs in the presence of IGF-1 and IGF-2, prevented ligand-induced phosphorylation of IGF-1R/IR receptors, and suppressed VEGF/IGF-2 driven angiogenesis in vivo. The combination of CP1-BO2 plus MEDI-573 was significantly superior to therapy with either antibody alone against IGF-1 and IGF-2 secreting pediatric sarcoma xenograft models.

Conclusions

These results suggest that combination of antibodies targeting IGF receptor and ligands may be an effective therapeutic strategy to block angiogenesis for IGF-driven tumors.

INTRODUCTION

Many human cancers, including childhood sarcomas, exhibit autocrine or paracrine growth through secretion of insulin-like growth factors 1 and 2 (IGF-1, IGF-2) and signaling through the Type 1 receptor (IGF-1R) (1, 2). IGF-1R is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is widely expressed in multiple human cancers and is activated by its related ligands, IGF-1 and IGF-2. This interaction activates intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, resulting in receptor auto phosphorylation and stimulation of signaling cascades that include the IRS-1/PI-3K/AKT/mTOR, and Grb2/Sos/Ras/MAPK pathways (3). Dysregulation of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) has been associated with the pathogenesis of various pediatric cancers, such as osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma, thereby providing a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of these tumors. (4). In preclinical models of childhood cancers, the prototypical anti-IGF-1R antibody, α-IR3, mediated down regulation of IGF-IR, significantly retarded growth of several cell lines in vitro (5, 6), and inhibited the growth of rhabdomyosarcoma xenografts (7).

IGF-1R and its ligands play roles not only in tumor cell proliferation and survival, but also in tumor angiogenesis (8). Two studies have suggested that IGF-1R antibodies exert a strong effect on tumor angiogenesis (6, 9). Our data showed anti-angiogenic activity of IGF-1R-binding antibody (SCH717454) both in vitro and in vivo but IGF-2 circumvented these effects (10). Many childhood cancers secrete IGF-2, suggesting that tumor-derived IGF-2 can promote angiogenesis in the presence of IGF-1R-targeted antibodies through binding to the insulin receptor (IR) permitting continued tumor growth. Several studies have reported overexpression of IGF2 in sarcoma cell lines as well as in primary tumors (5, 11-13).

Currently there are both small molecule drugs and fully human or humanized antibodies directed at the IGF-1R. Five fully human (CP-751871, AMG 479, R1507, IMC-A12, SCH717454) or humanized antibodies (H7C10/MK0646) have been evaluated in adult phase-I to -III clinical trials. These agents show specificity for IGF-IR although they may inhibit chimeric receptors formed through hetero-dimerization with the insulin receptor (IR). However, in xenograft models of childhood tumors associated with IGF-dysregulation, these antibodies induce only rare tumor regressions (6, 14, 15), consistent with the relatively low response rate of Ewing sarcoma patients to figitumumab (CP751871) (16). Intrinsic resistance may be a consequence of maintained signaling by IGF-2 through the IR (8, 10, 17, 18).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the anti-angiogenic activity of an IGF-ligand binding antibody (MEDI-573) alone, or combined with IGF-1R receptor-binding antibodies. This is the first report showing the anti-angiogenic activity of the ligand-neutralizing antibody MEDI-573, and reversal of activity by exogenous IGF-1. Our results also demonstrate that, both in vitro and in a mouse model, combined inhibition of IGF-1R and its ligands (IGF1/2) abrogates angiogenesis in the presence of exogenous IGF's. Targeting angiogenesis by inhibiting both IGF-1R and IGFs through use of dual antibodies may therefore be an effective anti-angiogenic strategy in pediatric sarcomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Medium 200, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Alamar Blue (AB) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Low serum growth supplement (LSGS) was obtained from Cascade Biologics Inc (Portland Oregon). Endothelial Tube formation assay kits were from Cell Biolabs, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Growth factor–reduced Matrigel for in vivo experiments and precoated Matrigel inserts for invasion assays were purchased from BD Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA). MedImmune generously provided MEDI-573 and CP1-B02 antibodies and MAB391 antibody was purchased from R&D Systems. MEDI-573 binds human IGF-2 with high affinity, while its affinity for human IGF-1 is lower, and affinity for murine IGF-1 is very low (19). CP1-B02 and MAB391 antibodies bind the IGF-1 receptor, preventing ligand binding. Human recombinant IGF-1 and IGF-2 were purchased from PeproTech Inc., NJ. BMS754807 was purchased through Selleckchem.com.

Cell Culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All experiments were done using endothelial cells between passages 3 and 8. HUVECs were maintained in medium M200 (Invitrogen) with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), endothelial cell growth supplements (LSGS Medium, Cascade Biologics), and 2 mM glutamine at 37°C with 5% CO2. All cells were maintained as sub confluent cultures and split 1:3, 24 hr before use. Rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS.

Western blotting

Cell lysis, protein extraction and immunoblotting were as described previously (6, 9). We used primary antibodies to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), AKT, phospho-AKT (Ser473), IGF-1R, and phospho-IGF-1R (Tyr1131), IR and phosphor-IR (Tyr1146) (Cell Signaling). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by using Super Signal Chemiluminiscence substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and Biomax MR and XAR film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY). Immuno-precipitations were performed by adding either 2μg of IGF-1R antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology Inc., Sant Cruz, CA). Fifteen μL of total sample was resolved on a 4-12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and immune-detection was performed with specific primary antibodies.

RT-PCR analysis for IGF-1R and INS receptor in HUVEC cells

HUVEC cells were cultured in M200 media. When cells were 80% confluent cells were washed with PBS and total RNA was harvested with the Qiagen RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). One μg of RNA was reverse transcribed with random primers and Superscript II Rnase H reverse transcriptase. The cDNA was stored in aliquots at –20 °C until use. For semi-quantitative PCR analysis was carried out using Platinum PCR Supermix (Invitrogen, USA) as instructed by the manufacturer. The following primers were used: IGF-I R forward primer: 5’-GAATTGCATGGTAGCCGAAG-3’, IGF-IR reverse primer: 5’-CCTCTTTGATGCTGCTGATG-3’, (389bp) and Insulin receptor forward primer: 5’-CATGGATGGAGGGTATCTGG-3’, Insulin receptor reverse primer: 5’-gTTTTTCTTGCCTCCGTTCA-3’ (364bp). The PCR cycling conditions for the IGF-1R and INS cDNA included pre-incubation for 5 min at 95°C and followed by 32 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 60s at 58°C, 60 s at 72°C and a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were identified using electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide (Et-Br).

Endothelial Cell Tube Formation Assay

For the Endothelial Tube Formation Assay (CBA200, Cell Biolabs Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), ECM gel was thawed at 4°C and mixed to homogeneity using cooled pipette tips. Cell culture plates (96-well) were bottom-coated with a thin layer of ECM gel (50 μl/well), which was left to polymerize at 37°C for 60 min. HUVECs (2-3×104) stimulated with VEGF in 150 μl medium were added to each well on the solidified ECM gel. Culture medium was added to each well in the presence or absence of ligand binding (MEDI-573) or receptor-binding (MAB391 or CP01-B02). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 12-18 hr and the endothelial tubes were observed using a fluorescent microscope after staining with Calcein AM. Three microscope fields were selected at random and photographed. Tube forming ability was quantified by counting the total number of cell clusters and branches under a 4X objective and four different fields per well. The results are expressed as mean fold change of branching compared with the control groups. Each experiment was performed at least three times.

Cell viability/proliferation assay

HUVECs were seeded on 6-well plates at a density of approximately 1×105 cells/well in M200 medium. Cells were treated with 10, 20 and 30 μg/ml of MEDI-573 one day after seeding. After 4 days, Calcein AB (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added directly into culture media at a final concentration of 10% and the plates were incubated at 37°C. Optical density was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 and 630 nm with at 3-4 h after adding Calcein AB. As a negative control, Calcein AB was added to medium without cells.

Vascularization of Matrigel™ Plugs in vivo

To further characterize anti-angiogenetic properties of MEDI-573 in vivo, we performed murine Matrigel plug experiments. An isotype matched control MoAb/PBS was used as a negative control, and VEGF (100ng/mL) as a positive control. Alternatively plugs containing VEGF (100 ng/ml) and IGF-2 (50 ng/ml) were implanted and mice received MEDI-573 alone, CP1-B02 alone or the two antibodies in combination. Matrigel was injected subcutaneously into CB17SC scid -/- female mice, forming semi-solid plugs. Animals received treatment of MEDI-573 (30 mg/kg) (19), the dose for CP1-B02 (20 mg/kg) was based on previous studies with IGF-1R binding antibodies (4, 14). Antibody concentrations were those causing maximal inhibition of angiogenesis. or the combination I.P. immediately after the Matrigel injection and on day 3. On day 7, plugs were excised under anesthesia, fixed in PBS-buffered 10% formalin containing 0.25% glutaraldehyde, and were processed for hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Masson's Trichrome staining. Vascular identity of the infiltrating cells was established with CD34 immunostaining. The regions containing the most intense areas of neovascularization (“hotspots”) were chosen for analysis. Eight hotspots were identified for each Matrigel or tumor section. The ImagePro Plus analysis system was used to quantify the percentage of area occupied by the vessel-like structures in each field. The mean ± SE from each group were compared. The negative control was obtained by tissue staining with secondary antibody only.

Evaluation of antibodies against pediatric tumor xenografts

All experiments were conducted under IACUC approved protocol AR09-00036. Four tumor models were selected. Two Ewings sarcomas (EW5, EW8) that secrete IGF-1, and two rhabdomyosarcoma (Rh18, Rh30) that secrete IGF-2 (6) Tumor lines and methods have been reported previously (20). Treatment was started when tumors exceeded 100 mm3. Mice received MED-573 (30 mg/kg), or CP01-B02 (20 mg/kg) or the combination twice weekly for a planned 6 weeks treatment and observation. Tumors were harvested when they reached 4-times the initial volume at start of therapy. Tumors were fixed and stained for CD34 positive cells to assess microvessel formation and for Ki67 staining for proliferation.

Statistics

Two-sample t-tests were used for the analysis of the experiments with continues outcomes using GraphPad Prism. Data were reported as mean ± SE. Type I error rate was set to 0.05. For in vivo testing against pediatric sarcoma xenograft models, criteria for defining an event (4 times the tumor volume at the start of treatment) was similar to that used by the PPTP (20). Log-rank tests were used to compare the time-to-event curves between groups and Holm's method was used to adjust multiplicity within each xenograft model. SAS 9.3 was used for this analysis (SAS, Inc; Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Effect of antibodies on ligand induced IGF-1R signaling

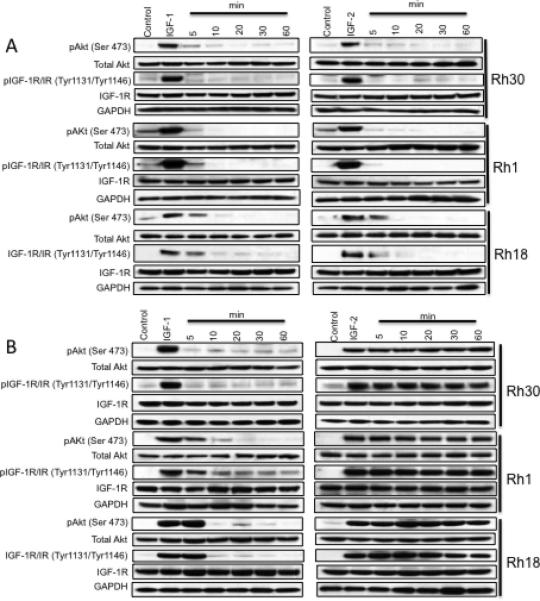

To determine whether MEDI-573 and MAB391 equally inhibited phosphorylation of Akt induced by IGF-1 and IGF-2, three sarcoma cells lines (Rh30, EW8, Rh18) were serum starved overnight, incubated with or without antibody [MEDI-573 (30 μg/ml) and MAB391(15 μg/ml)] for 5-60 min, then stimulated with IGF-1 or IGF-2 for 5 min. As shown in Figure 1A, IGF-1 and IGF-2 induced phosphorylation of Akt (S473) in control (no antibody) cells, but MEDI-573 rapidly suppressed the stimulation in all tumor cell lines, with almost complete abrogation of phospho-Akt within 15 minutes. In contrast, MAB391 did not suppress IGF-2-induced phosphorylation of Akt in any of the sarcoma cell lines, but did suppress IGF-1 induced Akt phosphorylation in the same lines (Figure 1B). This result is consistent with IGF-2 activating Akt via the IR (10). Thus, MAB391 had a similar activity to another IGF-1R-binding antibody, SCH717454, in that it failed to prevent IGF-2 binding and activating the insulin receptor(8).

Figure 1.

A. MEDI-573 inhibits bot IGF-1 and IGF-2 stimulation of Akt phosphorylation. Sarcoma cells were grown for 24 hr under serum-free conditions, then incubated for 5 - 60 min with MEDI-573 (30μg/ml), or 5 min without antibody, and stimulated for 5 min with IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) or IGF-2 (50 ng/ml). B. MAB391 inhibits only IGF-1 not IGF-2 stimulation of Akt phosphorylation. Sarcoma cells were grown for 24 hr under serum-free conditions, then incubated for 5 - 60 min with MAB391 (15μg/ml), or 5 min without antibody, and stimulated for 5 min with IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) or IGF-2 (50 ng/ml). Cells were harvested 5 min after IGF-stimulation at the times shown and phosphorylation of Akt(Ser473) and total Akt determined by immunoblotting.

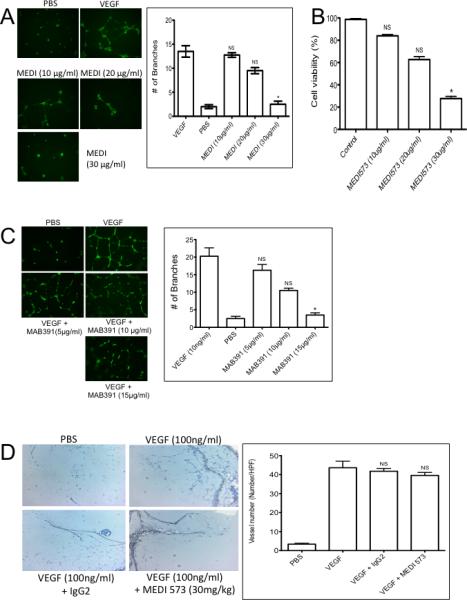

MEDI-573 potently inhibits angiogenesis by blocking HUVEC tube formation and proliferation in vitro

We next examined whether MEDI-573 inhibited VEGF165 induced tube formation of HUVECs, focusing on an antibody concentration range of 10 to 30 μg/ml. HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF165 (10 ng/mL) on Matrigel to form tubes in the absence or presence of MEDI-573 (Figure 2A). Reduction in tube formation by MEDI-573 was concentration-dependent; at 30 μg/ml the antibody significantly inhibited tube formation. For the proliferation assay HUVEC cells were stimulated with VEGF165 in the absence or presence of MEDI-573 and cell number determined by Calcein AB staining after 4 days. As shown in Figure 2B. MEDI-573 inhibited proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner with >70% inhibition at 30 μg/ml. An isotype matched (IgG2λ) control antibody had no effect on either tube formation of cell proliferation (data not shown).

Figure 2.

A. MEDI-573 inhibits HUVEC tube formation and proliferation in vitro. A. HUVECs were grown under serum-deficient conditions and stimulated with PBS or VEGF (10 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of MEDI-573 (10, 20 or 30 μg/ml). Tubes were visualized by staining with Calcein AM dye. Tube formation was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. B. Proliferation/viability was determined after 2 days by alamar blue (AB) staining. C. Mab391 inhibits HUVEC tube formation in vitro. HUVECs were grown under serum-deficient conditions and stimulated with VEGF (10 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of MAB391 (5, 10, 15 μg/ml). Tubes were visualized by staining with Calcein AM dye. D. Effect of MEDI-573 in murine angiogenesis in vivo. Matrigel plugs containing with PBS, or VEGF (100 ng/ml) were implanted subcutaneously in mice that were or were not treated with MEDI-573 (30 mg/kg day 0 and day 3). The Matrigel plugs were excised on day 7, fixed with formalin and 5-μm sections were stained with H&E, Messon Trichrome and CD34 staining. The numbers of CD34 positive vessels per high-power field (magnification, 200X) were counted for each experimental condition. Left panels, photomicrographs showing CD34 staining; Right panel: Results are mean (n =5) ± SE. *P <0.05; **P <0.01 versus VEGF alone. Right panel, quantitation of vessels. Mean ± SE. (Six HP fields counted).

MAB391 potently inhibit angiogenesis in vitro

Previous studies (6, 9, 10) have shown that IGF-1R-targeted antibodies exert anti-angiogenic effects, and that IGF-1R signaling is required for HUVEC proliferation when stimulated by VEGF (10). Results using MAB391 are consistent with these data, and show that MAB391 inhibits VEGF-stimulated tube formation of HUVECs in vitro at 15 μg/ml (Figure 2C).

Anti-angiogenic activity of MEDI-573 in vivo

To directly test the anti-angiogenic activity of MEDI-573 in vivo, mice were implanted subcutaneously with Matrigel plugs infused with PBS or VEGF165. Mice were treated with MEDI-573 (30 mg/kg) administered by intraperitoneal injection immediately after implantation of the plug and again after 3 days. Plugs were excised at day 7 and angiogenesis quantified as described in Materials and Methods. VEGF165 increased the number of vessels detected in Matrigel plugs by >10-fold over that in PBS infused (control) plugs. There was no observed reduction in vessel formation in the treated group as compared with controls (Figure 2D). Thus, MEDI-573 did not have detectable anti-angiogenic effects in the mouse. Similar to results with another IGF-1R-binding antibody (8) inclusion of IGF-2 into the Matrigel plug completely circumvented the anti-angiogenic activity of CP01-B02 treatment, Supplemental Figure 1.

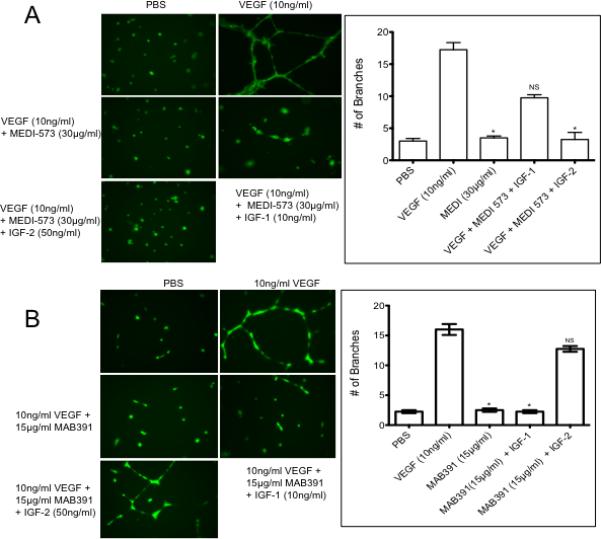

IGF-1 circumvents the anti-angiogenic activity of MEDI-573 in vitro

To ascertain why MEDI-573 failed to inhibit angiogenesis in the Matrigel plugs, we further examined its activity in vitro. While MEDI-573 is a dual IGF-1/IGF-2-neutralizing antibody, it binds IGF-1 with a lower affinity compared to its affinity for IGF2. Furthermore, the affinity of MEDI-573 for murine IGF-1 is far lower than that for human IGF-1 (19). It was thus possible that exogenous murine IGF-1 circumvented the ant-angiogenic effect of MEDI-573 in the mouse model. To test this we determined whether exogenous human IGF-1 or IGF-2 could circumvent the effect of MEDI-573 in blocking VEGF-induced proliferation of HUVECs. Cells were grown under serum-depleted conditions with PBS (control), or VEGF without and with MEDI-573, or with VEGF, antibody and exogenous IGFs. As shown in Figure 3A, VEGF stimulated tube formation was completely inhibited by MEDI-573. Exogenous IGF-2 (50 ng/ml) did not significantly overcome the effect of MEDI-573, whereas IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) partially circumvented the blockade.

Figure 3.

A. IGF-1 circumvents MEDI-573 inhibition. HUVECs were grown as described in Material and methods then stimulated with VEGF165 in the absence or presence of MEDI-573 (30 μg/ml), or antibody plus IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) or IGF-2 (50 ng/ml). Tube formation was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each result is the mean ± SE for 3 independent experiments. B. IGF-2 circumvents MAB391 inhibition. HUVECs were grown Medium 200, then stimulated with VEGF165 in the absence or presence of MAB391 (15 μg/ml), or antibody plus IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) or IGF-2 (50 ng/ml). Tube formation was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each result is the mean ± SE for 3 independent experiments.

IGF-2 circumvents the anti-angiogenic activity of MAB391 in vitro

Our previous results (10) showed that cells secreting IGF-2 could maintain angiogenesis in the presence of IGF-1R-targeted antibodies, whereas those secreting predominantly IGF-1 could not. We therefore tested whether exogenous IGF-1/2 could circumvent the MAB391 induced block of VEGF-induced tube formation of HUVECs. Cells were grown under serum-depleted conditions with PBS (control), or VEGF without and with MAB391, or with VEGF, antibody and exogenous IGFs. As shown in Figure 3B, VEGF stimulated tube formation was completely inhibited by MAB391. Exogenous IGF-1 did not significantly overcome the effect of MAB391, whereas IGF-2 circumvented the blockade.

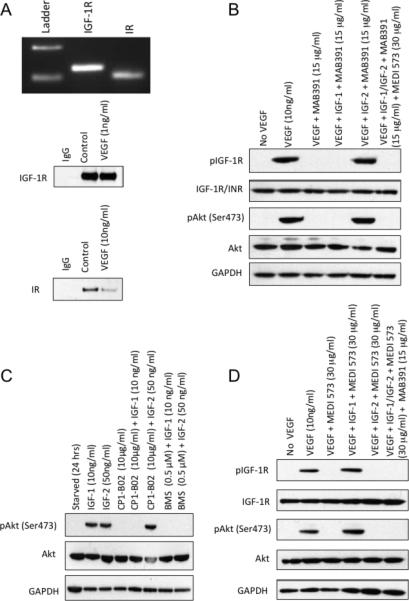

Effect of the combined of receptor binding and ligand binding antibodies on HUVEC tube formation

We next examined the expression of IGF-1 and insulin (IR) receptors on HUVEC cells. As shown in Figure 4A, both receptors were detected by RT-PCR and immunoblotting. Stimulation of HUVECs with VEGF induced a robust phosphorylation of IGF-1R at 24 hr that was blocked by the MAB391 receptor binding antibody. Stimulation of cells by VEGF in combination with IGF-1 was also completely abrogated by MAB391, whereas VEGF combined with IGF-2 circumvented the block on signaling, consistent with IGF-2 signaling through the IR, and continued phosphorylation of Akt, Figure 4B. In contrast a small molecule inhibitor of IGF-1R and IN-R, BMS754807 (21) equally inhibited IGF-1 and -2 induced phosphorylation of Akt in HUVECs (Figure 4C). A similar experiment was undertaken using MEDI-573 as the ligand-neutralizing antibody. In this case MEDI-573 blocked VEGF-induced phosphorylation of IGF-1R/IR. Stimulation of IGF-1R/IR phosphorylation was blocked by MEDI-573 in the presence of VEGF plus IGF-2 but not when cells were stimulated with VEGF combined with IGF-1. Combined treatment of HUVECs with MEDI-573 and MAB391 completely suppressed IGF-stimulated phosphorylation of IGF-1R/IR and suppressed ligand-induced phosphorylation of Akt, Figure 4D.

Figure 4.

A. Upper panel: Analysis of IGF-1R and IR, mRNA levels in HUVEC cells by RT-PCR amplification of IGF-1R (389 bp), INS (364 bp). RT-PCR products were analyzed on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. Lower panel: Immunoblot of HUVEC extracts demonstrating levels of IGF-1R and IR proteins at time of VEGF stimulation and at 24 hr. B. HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF in the absence or presence of IGF-1 receptor-binding antibody (MAB392; 10 μg/ml; 24 hr) without or with exogenous IGF-1 or IGF-2. C. BMS754807 (0.5 μM) inhibits IGF-1 and IGF-2 stimulated phosphorylation of Akt. HUVECs were starved as above, and incubated for 2 hr with CP1-B02 or BMS754807 prior to stimulation with IGF-1 or IGF-2. D. HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF in the absence of MEDI-573 ligand binding antibody (30 μg/ml; 24 hr) without or with exogenous IGF-1 or IGF-2. Right lane shows stimulation with both ligands in the presence of MAB391 and MEDI-573. Phosphorylation of IGF-1R (Tyr1131) or IR (Tyr1146) and Akt (Ser473) was determined at 24 hr.

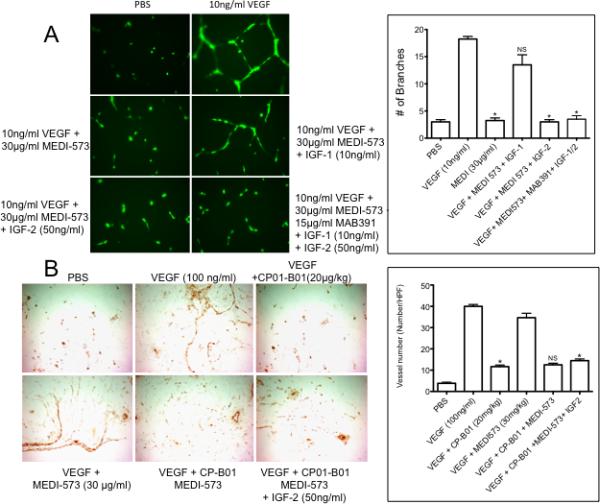

Based on these results we speculated that the combination of IGF-1R-targeted antibody MAB391 with the MEDI-573 antibody that binds IGF-1/2 would suppress VEGF-stimulated tube formation of HUVECs in the presence of IGF ligands. As shown in Figure 5A, VEGF stimulated tube formation was completely inhibited by the combination of MEDI-573 and MAB391 in presence of either exogenous IGF-1 and IGF-2. We have shown previously that including IGF-2 with VEGF in Matrigel plugs circumvents the anti-angiogenic effects of the IGF-1R-targeted antibody SCH717454 (10) and in vitro human IGF-1 circumvents the anti-angiogenic effects of MEDI-573, whereas murine IGF-1 circumvents MEDI-573 in vivo. We next tested whether the combination of MEDI-573 with an IGF-1R targeted antibody would effectively block VEGF or VEGF/IGF-2 driven angiogenesis in vivo. For these in vivo studies, that require large amounts of antibody, we used CP1-B02, an IGF-1R binding antibody provided by Medimmune. Characterization of CP1-B02 showed that it was similar to MAB391 (or SCH717454) in that it blocked IGF-1 stimulation of Akt phosphorylation, but not that induced by IGF-2, and potently blocked HUVEC tube formation and proliferation (Supplemental Figures 2-4). For in vivo evaluation, Matrigel plugs infused with PBS (control), VEGF (100 ng/ml), or VEGF+IGF-2 (50 ng/ml) were implanted subcutaneously. Mice received two administrations of MEDI-573, CP1-B02 or the combination of antibodies, and angiogenesis was determined on day 7, as described above. As shown in Figure 5B, CP1-B02 blocked VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis, whereas MEDI-573 did not. The combination of antibodies blocked VEGF stimulated angiogenesis, as anticipated, but also suppressed angiogenesis into Matrigel plugs containing both VEGF and IGF-2.

Figure 5.

A. Combination of both the antibodies effectively inhibits HUVEC tube formation in presence of ligands. HUVECs were grown Medium 200, then stimulated with VEGF in the absence of antibodies (PBS), or MEDI-573 (30 μg/ml) plus IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) or IGF-2 (50 ng/ml) or MEDI-573 with MAB391 and both IGF-1 and IGF-2. Tube formation was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each result is the mean ± SE for 3 independent experiments .B. Matrigel plugs containing with PBS, VEGF (100 ng/ml) or VEGF (100 ng/ml) plus IGF-2 (50 ng/ml) were implanted subcutaneously in mice. Mice received no treatment, MEDI-573 (30 mg/kg), CP1-B02 (C (20 mg/kg) or both antibodies on day 0 (after Matrigel plug implantation) and day 3. The Matrigel plugs were excised on day 7, and processed as described in the legend to Figure 3 (Mean ± SE from 6 high-power fields).

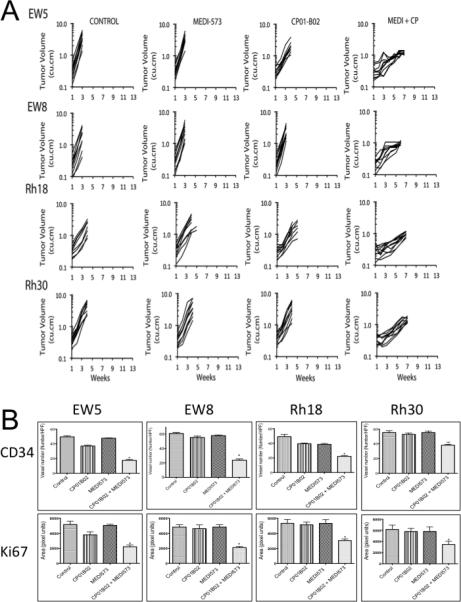

Effect of the combined of receptor binding and ligand binding antibodies on growth of IGF-secreting pediatric sarcoma xenografts

The antitumor activity of CP01-B02, MEDI-573 or the combination was evaluated against four pediatric sarcoma models. Ewing sarcoma lines (EW-5, EW-8) secrete predominantly IGF-1, whereas rhabdomyosarcoma lines (Rh18, Rh30) secrete predominantly IGF-2 (6). MEDI-573 or CP01-B)2 failed to significantly inhibit tumor growth of any model (p=0.784-1.00). In contrast, combined therapy with CP01-B02 plus MEDI-573 was significantly more effective than either single antibody treatment (p= 0.048 - <0.0001), Figure 6A and Supplemental Table 1. Consistent with the tumor growth inhibition results, only the combination of antibodies significantly (p=0.05) suppressed angiogenesis (CD34 positive cells) or proliferation (Ki67 staining), Figure 6B and Supplemental Figure 5.

Figure 6.

A. Antitumor activity of the IGF-ligand binding antibody (MED-573) or IGF-1 receptor-binding antibody (CP01-B02) alone or in combination (MEDI + CP). Antibodies were administered twice weekly at 30 mg/kg (MEDI-573), or 20 mg/kg (CP01-B-02) for a planned treatmen of 6 weeks. Treatment was initiated when tumors exceeded 100 mm3. B. Tumors were harvested at ‘event’ (4-fold tumor volume at treatment initiation), and stained for CD34 to determine tumor microvessels, and Ki67 to assess proliferation.

DISCUSSION

Alterations in the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling axis have been linked to the pathogenesis of various cancers including sarcomas. Consequently, inhibiting IGF-mediated signaling has become an attractive therapeutic approach. Small molecule inhibitors, antibodies directed at the IGF-IR as well as IGF-1/-2 neutralizing antibodies to block IGF-1R mediated signaling have all entered clinical trials. While receptor-targeted antibodies have shown antitumor activity in mouse models of childhood sarcomas (6, 14, 15), in most cases they do not induce actual tumor regression. These preclinical results mirror emerging clinical response rates where IGF-1R-targeted antibodies induce objective responses in only 10-14% of patients with some stabilization of disease in patients with Ewing sarcoma (16). Intrinsic resistance may be a consequence of IGF-2 signaling through the IR, thus bypassing the block on IGF-1R signaling (8, 10, 17, 18). Similarly, IGF-2 appears to circumvent the anti-angiogenic activities of receptor-targeted antibodies both in vitro and in vivo (8). In the mouse, circulating levels of IGF-2 are low or undetectable (22, 23), hence the antitumor and anti-angiogenic activities of IGF-1R-targeted antibodies may be overestimated. However, if tumor cells secreting IGF-2 are circumventing the anti-angiogenic effects of receptor targeted antibodies by signaling through the IR (10), therapies that neutralize IGF-2 may be potentially important. Insulin receptor-A (the high affinity IGF-2 receptor where exon 11 is spliced out) is expressed in most xenografts, and cell lines derived from childhood sarcomas, as well as human vascular endothelial cells ((10),Supplemental Figure 3). Hence blocking potential IGF-2/IR-A signaling may be an important determinant of anti-angiogenic or anti-tumor activity

Several approaches to inhibiting the IGF-I/IGF-1R axis have been proposed including ligand binding antibodies and administration of IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) (19, 24). Here we evaluated the anti-angiogenic activity of the IGF-1/IGF-2 ligand neutralizing antibody, MEDI-573 (19). We also evaluated available receptor binding antibodies for in vitro (MAB391) and in vivo (CP1-B02), in combination with MEDI-573 to block angiogenesis.

Both MAB391 and CP1-B02 behaved similarly to the IGF-1R-targeting antibody SCH717454. Specifically, MAB391 or CP1-B02 potently inhibited IGF-1-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt, but not that induced by IGF-2. Both antibodies inhibited in vitro angiogenesis of HUVECs, and this was circumvented by IGF-2. MEDI-573 is a fully human antibody that neutralizes both IGF-1 and IGF-2 and inhibits IGF signaling through both the IGF-1R and IR-A pathways (19). In contrast to MAB391 and CP1-B02, MEDI-573 blocked both IGF-1 and IGF-2 induced phosphorylation of Akt in several sarcoma cell lines. MEDI-573 inhibited VEGF-stimulated HUVEC tube formation and proliferation in vitro, but surprisingly did not significantly suppress VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis in a mouse model. In part, failure to inhibit angiogenesis in the mouse model may be explained by the relatively low binding affinity of the antibody for mouse IGF-1 (KD ~2000pmol/L) (19). To examine this further, we determined whether human recombinant IGF-1 could circumvent the MEDI-573-mediated block on proliferation and differentiation of HUVECs in vitro. We found that exogenous human recombinant IGF-1 could partially or completely restore normal proliferation and tube formation in the presence of MEDI-573. This may reflect the lower binding affinity of this antibody for IGF1 compared to IGF-2 (KD's 294 pmol/L versus 2 pmol/L) (19). As IGF-2 circumvented the anti-angiogenic effect of MAB391 and IGF-1 circumvented the effect of MEDI-573, we considered combining the antibodies as a potential anti-angiogenic strategy. Indeed, while each antibody alone blocked HUVEC proliferation and differentiation in the absence of exogenous IGFs, the combination of receptor-binding and ligand-neutralizing antibodies completely suppressed in vitro angiogenesis in the presence of exogenous IGFs, prevented ligand-induced phosphorylation of IGF-1R/IR and blocked activation of Akt. Similarly, the combination of CP1-B02 and MEDI-573 completely suppressed angiogenesis into Matrigel plugs containing both VEGF and IGF-2.

Neither MEDI-573 nor CP01-B02 antibodies significantly inhibited growth of any of the four sarcoma xenograft models. In part, it was surprising that the IGF-1R-targeting antibody (CP-01B02) did not demonstrate activity against Ewing sarcoma models as these secrete predominantly IGF-1, although in vitro cell lines also secrete IGF-2. As expected, MEDI-573 did not inhibit growth, in part due to circulating mouse IGF-1 for which it has low binding affinity. However, combining the antibodies had significantly greater activity in each tumor model. In combination these antibodies significantly reduced CD34 staining and Ki67 staining, suggesting a marked anti-angiogenic effect caused decreased tumor cell proliferation.

Our results clearly support the idea that dual targeting of IGF-1R and its ligands (IGF-1/IGF-2) may be an effective anti-angiogenesis strategy. The xenograft studies verified the therapeutic efficacy of such combinations against IGF-1 and IGF-2 secreting tumors, such as Ewing sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma, respectively. Together, these studies provide a sound scientific base for developing this novel strategy for treatment of childhood sarcomas.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Antibodies that bind the Type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R), and prevent ligand association, have been tested in numerous clinical trials. Despite compelling data to indicate the importance of IGF-1R-mediated signaling particularly in sarcoma cells, these antibodies have rarely induced objective tumor regressions either in sarcoma patients or in preclinical xenograft models of sarcoma. Our data suggest that IGF-1R-targeted antibodies are potent antiangiogenic agents. However, tumor-derived IGF-2 circumvents the IGF-1R antibodies, signaling through the insulin receptor (IR). In contrast, antibodies that bind IGF ligands inhibit IGF-2 stimulated proliferation of human vascular endothelial cells, but the effect is reversed by exogenous IGF-1. Consequently, the antiangiogenic activity of a combination of IGF-1R-targeted and IGF-ligand binding antibodies was examined in vitro and in vivo. Results indicate that the combination of antibodies effectively suppresses VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis both in vitro and in a mouse model, and significantly inhibits growth and agiogenesis of IGF-driven pediatric sarcoma xenograft models.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by USPHS grants CA77776, CA23099 and CA165995 from the National Cancer Institute, and the Pelotonia Foundation Fellowship (HKB). MEDI-573 and CP1-B02 antibodies were generously provided by MedImmune.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim SY, Wan X, Helman LJ. Targeting IGF-1R in the treatment of sarcomas: past, present and future. Bull Cancer. 2009;96:E52–60. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2009.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SY, Toretsky JA, Scher D, Helman LJ. The role of IGF-1R in pediatric malignancies. Oncologist. 2009;14:83–91. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chitnis MM, Yuen JS, Protheroe AS, Pollak M, Macaulay VM. The type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6364–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolb EA, Gorlick R. Development of IGF-IR Inhibitors in Pediatric Sarcomas. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009;11:307–13. doi: 10.1007/s11912-009-0043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Badry OM, Minniti C, Kohn EC, Houghton PJ, Daughaday WH, Helman LJ. Insulin-like growth factor II acts as an autocrine growth and motility factor in human rhabdomyosarcoma tumors. Cell Growth Differ. 1990;1:325–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurmasheva RT, Dudkin L, Billups C, Debelenko LV, Morton CL, Houghton PJ. The insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-targeting antibody, CP-751,871, suppresses tumor-derived VEGF and synergizes with rapamycin in models of childhood sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7662–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalebic T, Tsokos M, Helman LJ. In vivo treatment with antibody against IGF-1 receptor suppresses growth of human rhabdomyosarcoma and down-regulates p34cdc2. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5531–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bid HK, Zhan J, Phelps DA, Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ. Potent inhibition of angiogenesis by the IGF-1 receptor-targeting antibody SCH717454 is reversed by IGF-2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:649–59. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Lipari P, Wang X, Hailey J, Liang L, Ramos R, et al. A fully human insulin-like growth factor-I receptor antibody SCH 717454 (Robatumumab) has antitumor activity as a single agent and in combination with cytotoxics in pediatric tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:410–8. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bid HK, Zhan J, Phelps DA, Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ. Potent Inhibition of Angiogenesis by the IGF-1 Receptor-Targeting Antibody SCH717454 is Reversed by IGF-2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minniti CP, Tsokos M, Newton WA, Jr., Helman LJ. Specific expression of insulin-like growth factor-II in rhabdomyosarcoma tumor cells. American journal of clinical pathology. 1994;101:198–203. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:3–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakae J, Kido Y, Accili D. Distinct and overlapping functions of insulin and IGF-I receptors. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:818–35. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.6.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Lock R, Carol H, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) of a monoclonal antibody (SCH 717454) against the IGF-1 receptor by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1190–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Keir ST, Reynolds CP, et al. Initial testing of a monoclonal antibody (IMC-A12) against IGF-1R by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:921–6. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olmos D, Postel-Vinay S, Molife LR, Okuno SH, Schuetze SM, Paccagnella ML, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary activity of the anti-IGF-1R antibody figitumumab (CP-751,871) in patients with sarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma: a phase 1 expansion cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:129–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70354-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beltran PJ, Chung YA, Moody G, Mitchell P, Cajulis E, Vonderfecht S, et al. Efficacy of ganitumab (AMG 479), alone and in combination with rapamycin, in Ewing's and osteogenic sarcoma models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:644–54. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.178400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garofalo C, Manara MC, Nicoletti G, Marino MT, Lollini PL, Astolfi A, et al. Efficacy of and resistance to anti-IGF-1R therapies in Ewing's sarcoma is dependent on insulin receptor signaling. Oncogene. 2011;30:2730–40. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao J, Chesebrough JW, Cartlidge SA, Ricketts SA, Incognito L, Veldman-Jones M, et al. Dual IGF-I/II-neutralizing antibody MEDI-573 potently inhibits IGF signaling and tumor growth. Cancer research. 2011;71:1029–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Tucker C, Payne D, Favours E, Cole C, et al. The pediatric preclinical testing program: description of models and early testing results. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:928–40. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carboni JM, Wittman M, Yang Z, Lee F, Greer A, Hurlburt W, et al. BMS-754807, a small molecule inhibitor of insulin-like growth factor-1R/IR. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3341–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Ercole AJ, Underwood LE. Ontogeny of somatomedin during development in the mouse. Serum concentrations, molecular forms, binding proteins, and tissue receptors. Dev Biol. 1980;79:33–45. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moses AC, Nissley SP, Short PA, Rechler MM, White RM, Knight AB, et al. Increased levels of multiplication-stimulating activity, an insulin-like growth factor, in fetal rat serum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:3649–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallicchio MA, Kneen M, Hall C, Scott AM, Bach LA. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-6 inhibits rhabdomyosarcoma growth in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:645–51. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.