Abstract

Establishment of cell polarity—or symmetry breaking—relies on local accumulation of polarity regulators. Although simple positive feedback is sufficient to drive symmetry breaking, it is highly sensitive to stochastic fluctuations typical for living cells. Here, by integrating mathematical modelling with quantitative experimental validations, we show that in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae a combination of actin- and guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor-dependent recycling of the central polarity regulator Cdc42 is needed to establish robust cell polarity at a single site during yeast budding. The guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor pathway consistently generates a single-polarization site, but requires Cdc42 to cycle rapidly between its active and inactive form, and is therefore sensitive to perturbations of the GTPase cycle. Conversely, actin-mediated recycling of Cdc42 induces robust symmetry breaking but cannot restrict polarization to a single site. Our results demonstrate how cells optimize symmetry breaking through coupling between multiple feedback loops.

A positive feedback loop which results in localized accumulation of the small GTPase Cdc42 generates cell polarity in budding yeast; however, such loops are inherently susceptible to noise. Here the authors demonstrate how two pathways that mediate Cdc42 recycling work together to ensure the robustness of symmetry breaking.

A positive feedback loop which results in localized accumulation of the small GTPase Cdc42 generates cell polarity in budding yeast; however, such loops are inherently susceptible to noise. Here the authors demonstrate how two pathways that mediate Cdc42 recycling work together to ensure the robustness of symmetry breaking.

The Rho-type GTPase Cdc42 is a central regulator of cell polarity in animal and fungal cells1,2. At the G1–S transition in the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cdc42 becomes concentrated in a cortical cap that defines the future bud site3,4. Cdc42 binds to various effectors that control essential morphogenetic processes, such as polarized membrane transport5, assembly of a septin ring6 and fusion of exocytic vesicles with the plasma membrane7,8. To fulfill its functions, Cdc42 must constantly cycle between GTP-bound/active and GDP-bound/inactive states. In budding yeast activation of Cdc42 is controlled by a single guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), Cdc24 and Cdc42 hydrolytic activity is promoted by four GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), Bem2, Bem3, Rga1 and Rga2 (ref. 7). In addition, Cdc42 is extracted from membranes by a single Rho-guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI), Rdi1 (refs 9, 10).

Concentration of Cdc42 at the polarization site in yeast cells can occur via feedback amplification of stochastic fluctuations11,12 and either requires focused, actin-mediated transport of vesicle-bound Cdc42 (refs 13, 14) or Bem1-mediated recruitment of soluble Cdc42 (refs 14, 15, 16, 17). Both pathways drive polarization through constant recycling of Cdc42 (refs 14, 17).

Polarized transport of Cdc42-bearing vesicles has been shown to underlie spontaneous polarization of constitutively active and membrane-restricted Cdc42 via a simple positive feedback mechanism13. In addition, polarization of wild-type Cdc42 depends on actin-based secretion, particularly in the absence of Bem1 (ref. 14) or Rdi1 (ref. 17). However, although a role for membrane transport in polarity establishment has been widely established18,19, its relevance for polarization of wild-type yeast cells is still controversial11,16,20,21,22. A negative role for actin in cell polarization has even been proposed based on endocytosis of polarity regulators20,23 or dilution of Cdc42 in the cap region24,25. Although such mechanisms provide explanations for travelling waves23 or oscillating polarization patches24, they cannot account for the positive role of actin during the actual process of symmetry breaking—both in the presence and absence of Bem1-driven feedback13,14.

A second polarization mechanism has been proposed to rely on activation of Cdc42 through a Bem1-Cdc24-Cla4 complex15,16,26,27 and on extraction of Cdc42 from membranes by Rdi1 (ref. 17). The available experimental evidence has been combined in a Turing-type model of yeast polarization28. However, many details of the proposed reactions remain under debate12,21,29. Moreover, the precise relationship between actin- and GDI-dependent mechanisms during establishment of polarization in wild-type cells is unclear.

Here, we built a stochastic model for yeast polarity establishment through actin- and GDI-mediated recycling of Cdc42. We established assumptions and parameter values for this model through genetic analyses, in vitro reconstitution and live cell imaging. Predictions from the model were tested and validated experimentally. We demonstrate that the establishment of a stable and unique polarization axis requires coordination of two pathways. Actin-mediated recycling of Cdc42 is very robust, but does not reliably result in formation of a single-polarization site. In contrast, GDI-dependent recycling is sensitive to changes in the GTPase cycle of Cdc42 but faithfully generates a unique polarization site. Our results suggest that correct polarity establishment is achieved through coupling of multiple feedback loops.

Results

Validation of strains

To build a mechanistic model for yeast polarity establishment we sought to firmly establish the connections between all involved regulators and pathways. Spontaneous cell polarization has been proposed to occur via amplification of stochastic fluctuations through simple positive feedback in the presence of low concentrations of reacting molecules30,31 but this model has been recently challenged24. In an attempt to resolve this issue we varied expression levels of GFP-Cdc42 in control and LatB-treated cells with an inducible GAL promoter30. We indeed found that Cdc42 expression level had no effect on polarization efficiency (Supplementary Fig. S1a).

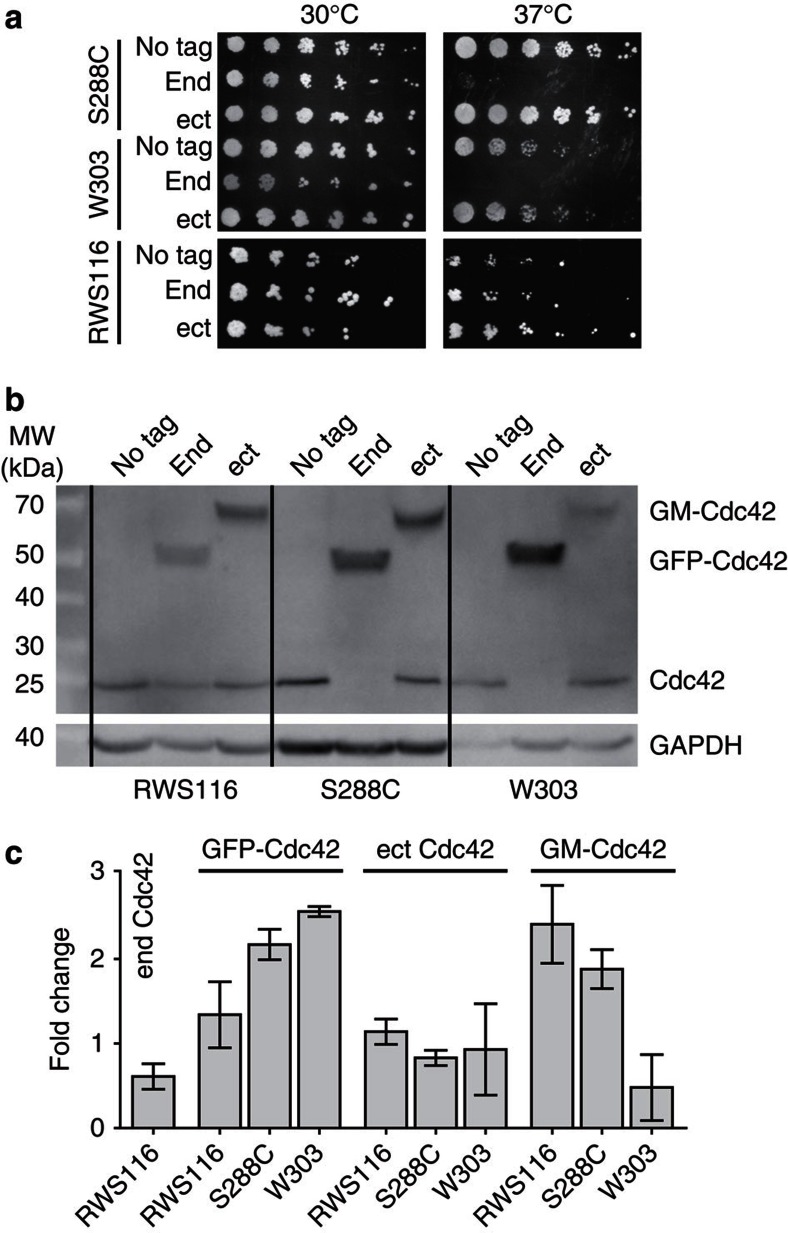

When we tagged the genomic copy of Cdc42 in haploid cells of S288C and W303 backgrounds we confirmed24 that expression of GFP-Cdc42 as the only source of Cdc42 leads to impaired growth of yeast cells at high temperatures (Fig. 1a). We also tagged Cdc42 in the strain RWS116, which could be arrested in the cell cycle through depletion of the G1 cyclins14. The resulting strain retained a duplicated version of the untagged Cdc42 expressed to half the level of the GFP–Cdc42 fusion (Fig. 1b). This strain as well as strains expressing GFP-myc-Cdc42 from ectopic chromosomal loci (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. S1b) exhibited no temperature sensitivity (Fig. 1a). Tagging also did not affect growth and polarization kinetics, either in the presence or absence of actin-dependent transport (Supplementary Fig. S1c–f).

Figure 1. Effects of GFP-tagging of Cdc42 on cell growth and polarization.

(a) Growth of the standard lab strains S288C and W303 and the arrest-strain RWS116 at different temperatures. Shown are the respective control strains (no tag) and strains where Cdc42 has been tagged at its endogenous locus (end) or as additional copy integrated in the ectopic LEU2 locus (ect). (b) Western blot of different Cdc42 fusion proteins in the strains used in (a). Cdc42 was detected with a polyclonal serum against Cdc42. A monoclonal antibody against the constitutively expressed glyceraldehyde-2-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as loading control. Identity of visualized bands is indicated on the right. (c) Quantification of Cdc42 expression levels showing fold change compared with expression of the endogenous copy in the respective strain background. Bars correspond to mean±s.d. from three independent experiments. Labels correspond to untagged Cdc42 in strains expressing GFP-Cdc42 at the endogenous locus (end Cdc42) or the LEU2 locus (ect Cdc42), to GFP tagged Cdc42 at the endogenous locus (GFP-Cdc42) and GFP-myc tagged Cdc42 at the LEU2 locus (GM-Cdc42). Strain backgrounds are indicated on x axis.

Parallel Cdc42 recycling pathways in polarity establishment

Overexpressed Cdc42 might be buffered by its GDI, which is generally found in a 1:1 complex with its substrates in the cytosol32. Actin and Rdi1 have been proposed to act in parallel during polarity maintenance17. To systematically investigate the connection between Rdi1- and actin-mediated recycling of Cdc42, we analysed genetic interactions of Cdc42 and its regulators with synthetic genetic arrays33. Genetic lesions in all examined components had a negative impact on processes linked to actin functions (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, few physical interactions of Cdc42 regulators with actin-associated proteins have been reported (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S2). These results indicate that, in addition to the role of Cdc42 in formation and polarization of actin structures, Cdc42 signalling and actin-mediated transport processes also act in parallel during essential cellular processes.

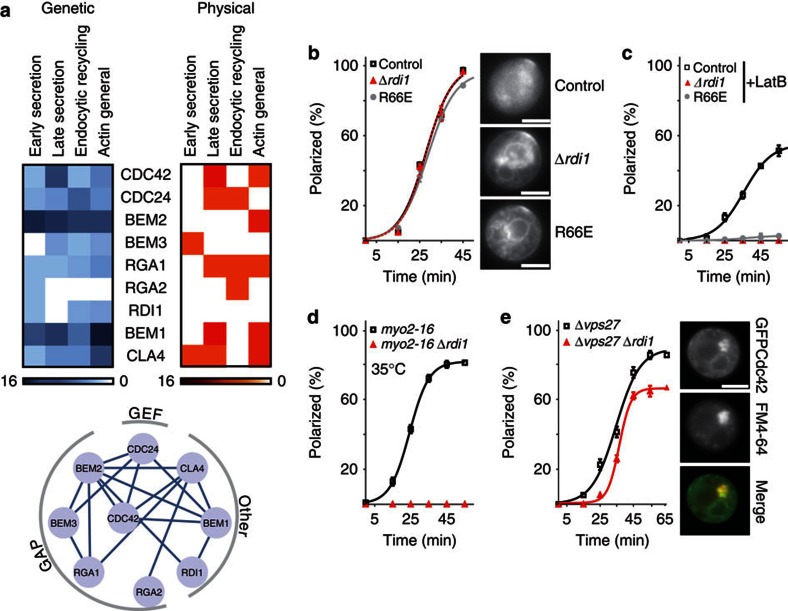

Figure 2. Polarity establishment through GDI- and actin-mediated recycling of Cdc42.

(a) Heat plots of genetic (blue) and physical (red) interactions between Cdc42 regulators and proteins involved in actin-related processes. Colour code: number of interactions. Genetic interactions among Cdc42 regulators are indicated in the lower panel. (b–e) Effects of genetic and pharmacological perturbations on polarization kinetics of Cdc42. Data points represent means of three experiments with n=50 cells each. Error bars indicate mean±s.d. Continuous lines are sigmoidal fits. Individual plots depict the effects of: (b) inhibiting extraction of Cdc42 from the plasma membrane in Δrdi1 cells and cells expressing Cdc42R66E, a mutant that cannot interact with the GDI; (c) disruption of actin polymerization (by LatB) in control, Δrdi1 and cdc42R66E cells; (d) inactivation of the temperature-sensitive myo2–16 allele in control and Δrdi1 cells, and (e) deletion of VPS27 in control and Δrdi1 cells. Colocalization of Cdc42 and the membrane dye FM4-64 in aberrant endosomal compartments of Δvps27 cells is demonstrated in panel e. Scale bar, 4 μm.

Rdi1 exhibited interactions with several components involved in endocytic recycling (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S1), consistent with a role in actin-independent recycling of Cdc42 during polarity establishment. To test this, we studied synchronized yeast cells expressing GFP–Cdc42 fusions (Supplementary Fig. S1b–d), and monitored Cdc42 cap formation14. As expected from a defect in extraction of membrane-bound Cdc42, Δrdi1 cells accumulated Cdc42 on membranes (Fig. 2b). Nevertheless, polarization kinetics were unaffected in Δrdi1 cells and in cells expressing Cdc42R66E, a mutant unable to interact with the GDI34 (Fig. 2b). However, depolymerization of actin with latrunculin B (LatB), which has moderate effects on control cells14 (Fig. 2c), blocked polarization in Δrdi1 and Cdc42R66E-expressing cells (Fig. 2c). A similar synergistic effect was observed when exocytosis was blocked using a temperature-sensitive allele of MYO2 (myo2–16, Fig. 2d). Reduction of endocytosis by deletion of the ESCRTIII component VPS27 (ref. 35) resulted in less efficient polarization of Δrdi1 cells (Fig. 2e). Colocalization of GFP-Cdc42 and FM4-64-stained endocytic membranes in Δvps27 cells revealed Cdc42 accumulation in aberrant endocytic compartments, confirming passage of Cdc42 through the endocytic system (Fig. 2e).

Our results confirm that Rdi1- and actin-based cycling of Cdc42 contribute to polarity establishment via distinct and parallel mechanisms. We therefore proceeded to design a particle-based mathematical model of Cdc42 polarization to study the interplay between the two pathways.

A stochastic model for polarity establishment

To build an experimentally tractable model, we considered the two recycling pathways for Cdc42 separately. Recent studies have stressed the importance of considering individual vesicle carriers instead of simple protein flux21,25. However, many mechanistic details of actin-based membrane recycling are unknown, rendering detailed models highly speculative. Importantly, the proposed dilution effect of vesicle delivery on the Cdc42 cap21 is not supported by our experiments, as Cdc42 cap intensities are significantly higher in control cells compared with cells, in which actin-mediated transport processes are disrupted (Fig. 3a). A recent study has also shown the feasibility of polarity establishment if Cdc42 exhibits non-uniform diffusion36. We therefore opted to simulate actin-mediated recycling of Cdc42 using a coarse-grained approach (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Tables S8, 9). We assumed that membrane-bound Cdc42 molecules are delivered to the plasma membrane from internal membranes along actin cables. Sites of enhanced cable nucleation are generated at a rate that depends on the amount of active Cdc42 at the respective nucleation site. Endocytosis was modelled with a constant extraction rate.

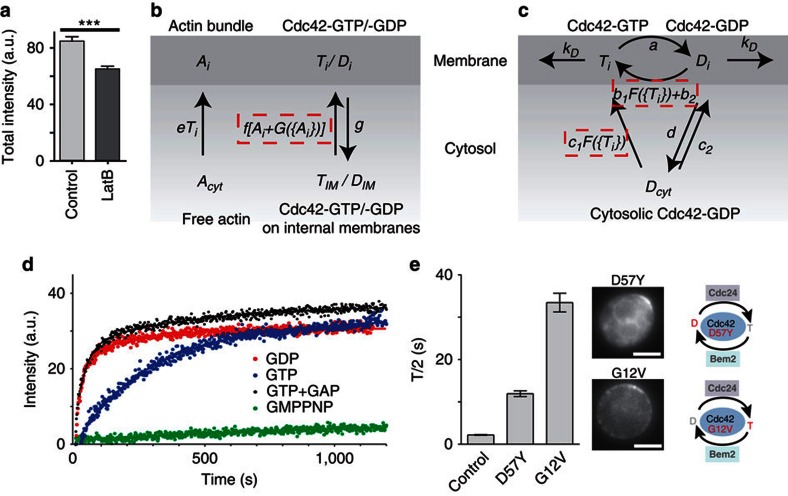

Figure 3. Building a mathematical model of the combined pathways.

(a) Comparison of total intensities of GFPCdc42 caps in controls and LatB-treated cells. Bars indicate means±s.e.m. n>80. ***t-test, P<0.0001. (b,c) Schematic depiction of model reactions for actin- (b) and GDI-mediated (c) recycling pathways. See Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Tables S1,S2 for details of reactions and parameters. Non-linear feedback reactions are indicated by dashed boxes. (d) Extractability of Cdc42 from hexadecanoylaminofluorescein (HAF)-labelled liposomes loaded with the indicated methylanthraniloyl-modified (Mant-) nucleotides. (e) Halftimes (FRAP T/2) for localization of inactive Cdc42D57Y (n=16) and constitutively active Cdc42G12V (n=16). Bars indicate mean±s.e.m. The schematics illustrate changes in the Cdc42 GTPase cycle. Scale bar, 4 μm.

For Rdi1-mediated recycling (Fig. 3c) we assumed a well-mixed pool of Cdc42 in the cytosol and diffusion of Cdc42 in the plasma membrane with D=0.036 μm2 s−1 (ref. 37). Nucleotide exchange can occur spontaneously or catalysed by the GEF Cdc24 via a bounded positive feedback loop involving the Cdc42 effector Bem1 (refs 14, 15). Such bounded feedback is essential to achieve realistic cap shapes (Fig. 4) and corresponds to depletion of limiting components involved in Cdc42 recruitment. GTP hydrolysis is modelled with a constant rate depending on GAP activity.

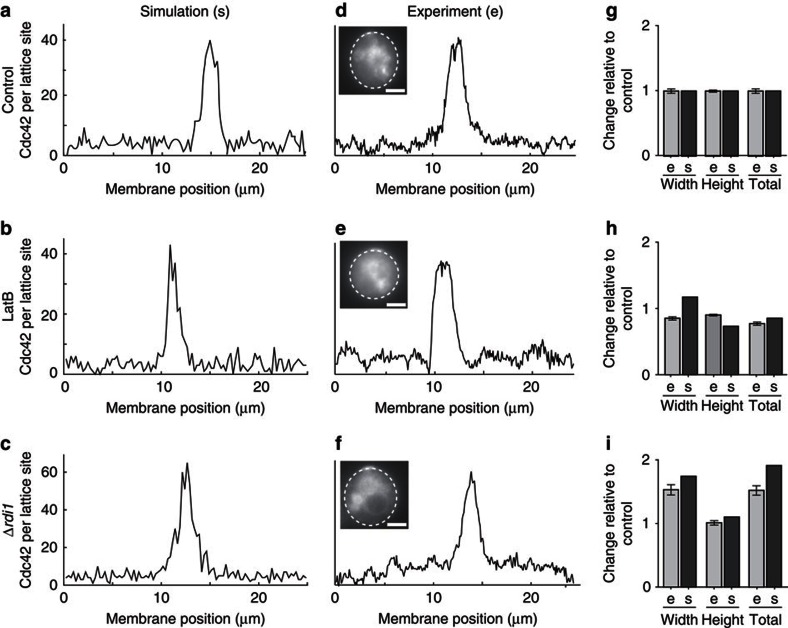

Figure 4. Fitting cap shape parameters.

(a–f) Examples of simulated (a–c) and experimentally determined (d,e) cap profiles in control cells (a,d), LatB-treated cells (b,e) and Δrdi1 cells (c,f). Dashed lines in images indicate fields of view used for line scans. Scale bar, 4 μm. (g–i) Comparisons of cap size (width), average cap intensity (height) and total cap intensity (total,=width × height) in experiments (e) and simulations (s) for control (g), LatB-treated (h) and Δrdi1 cells (i). Bars represent means±s.e.m. of measurements normalized to values for control cells (n>80 for control and LatB cells, and n=35 for Δrdi1 cells). Note that total intensity values for control and LatB cells correspond to the values used in Fig. 3a.

It has been shown that GDIs preferentially extract GDP-bound Rho GTPases38,39. To firmly establish this important aspect in our model, we performed in-vitro extraction experiments with purified Cdc42 and RhoGDI39. We found that the GDI indeed extracted GDP-bound Cdc42 around 10 times faster than GTP-Cdc42 (Fig. 3d). In the presence of catalytic amounts of GAP domain, GTP-Cdc42 was extracted at nearly the same rate as GDP-Cdc42 (Fig. 3d), indicating that GTP hydrolysis is rate-limiting for GDI-mediated Cdc42 extraction. This was supported by the extremely slow extraction of Cdc42 bound to non-hydrolyzable GTP analogue (GMPPNP, Fig. 3d). In living yeast cells, we confirmed previous reports14,17 that constitutively active Cdc42 (Cdc42G12V) is restricted to membranes and the slow actin-mediated recycling pathway (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Table S9). Hence, we incorporated selective extraction of GDP-Cdc42 by the GDI into our model.

Recruitment from the Rdi1-GDP-Cdc42 pool to the membrane was assumed to occur at a background rate and via a second positive feedback loop that enhances attachment of cytosolic Cdc42 to sites of high Cdc42 activity. This feedback represents the previously proposed competition between Rab and Rho GEFs and the respective GDIs40,41,42. To observe whether such competition indeed occurs for Rho GTPases, we investigated the effect of GEF activity on the interaction between GDI and mammalian Rac1, which is similar in mechanism and kinetics to GDI–Cdc42 interaction39. Exposure to the GEF domain of Dock180 (DHR2C) and a non-hydrolyzable GTP analogue was sufficient to dissociate soluble GDI–Rac1 complexes, allowing free GMPPNP-bound Rac1 to bind to liposomes (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Conversely, nucleotide exchange by the GEF was strongly reduced in the presence of GDI (Supplementary Fig. S2b), consistent with competition for binding to the switch II region of the GTPase40. These results cannot be directly transferred to living yeast cells. However, we found that the dominant-negative mutant Cdc42D57Y, which sequesters its GEF43,44, could no longer be extracted by the GDI and was instead slowly recycled via actin-mediated transport14,17 (Fig. 3e). Our results are consistent with competition between GEF and GDI for binding of Cdc42-GDP. We therefore implemented interference of GEF activity with Cdc42–GDI interaction by increasing the rate of Cdc42 membrane association in regions of high Cdc42 activity (equivalent to high GEF concentrations).

GDI-mediated polarization is of considerable theoretical interest28,30,45. Our results indicate that GDI-mediated recycling of Cdc42 depends on the latter’s catalytic cycle, and both GAP and GEF need to be regulated to allow rapid shuttling between membrane and cytosol. In a previous model, positive feedback in Cdc42 activation was based on non-linear recruitment of Cdc24 to Cdc42-GTP28,46. The model predicts slower turnover of Cdc24 if Cdc42 activity is increased. However, we found that the level of GEF expression or actin or Cdc42 activity had no influence on Cdc24 turnover at the polarized site (Supplementary Fig. S3b), indicating that feedback must be implemented in a different manner. Our model assumes linear recruitment of the GEF to Cdc42-GTP, but instead incorporates two GEF-mediated, and experimentally supported, positive feedback loops for activation and physical recruitment of Cdc42 (dashed boxes in Fig. 3c), respectively. A short comparison of features and limitations in various models for yeast cell polarity is shown in Supplementary Table S10. A detailed review on this subject has also been published recently47.

Determination of quantitative model parameters

Having established a general structure for the two Cdc42 recycling pathways we set out to determine realistic values for the parameters involved in their operation. We aimed to base all model reactions (Supplementary Table S8) and parameters (Supplementary Table S9) on experimental evidence. Several parameter values and data concerning the distribution of Cdc42 between cell compartments were taken from the literature (Supplementary Methods). The remaining values were fitted to quantitatively reproduce characteristics of control cells and of the individual recycling pathways observed in LatB-treated or Δrdi1 cells (Figs 4, 5). In all conditions our model was able to recapitulate polarization profiles of Cdc42 with realistic background levels and values for cap width and cap height (Fig. 4). In addition, the polarization response was robust to considerable variations in the individual parameter values (Supplementary Fig. S4).

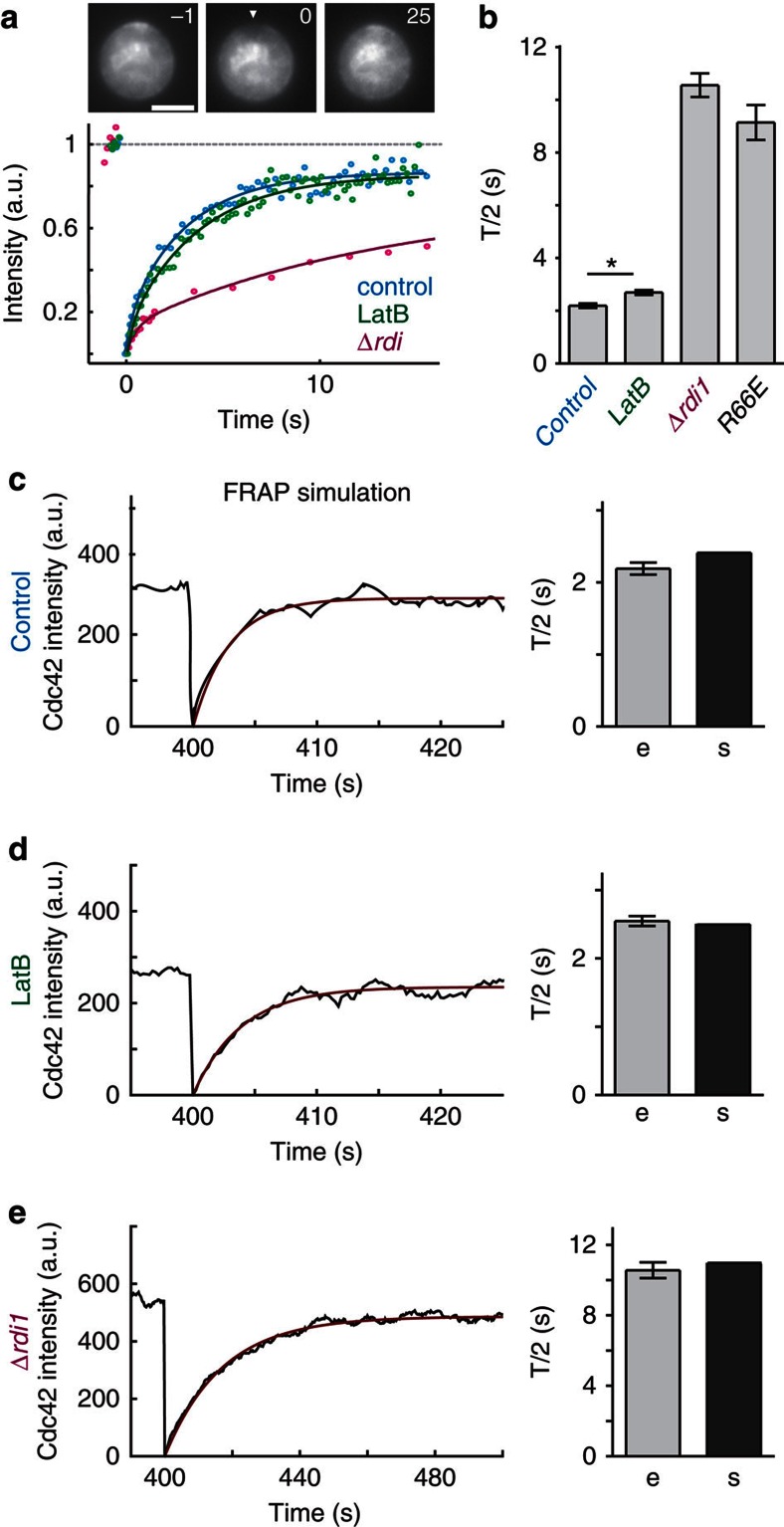

Figure 5. Fitting Cdc42 turnover parameters.

(a,b) Representative FRAP curves (a) and FRAP T/2 values (b) for GFPCdc42 in controls (n=56), Δrdi1 cells (n=20), cells expressing GFPCdc42R66E (n=11) and cells treated with LatB (n=24). The arrowhead in (a) indicates the position targeted for FRAP. Bars in (b) represent means±s.e.m. *: t-test, P<0.05. Time is indicated in s. Scale bar, 4 μm. (c–e) Simulated (black) FRAP curves and exponential fits (red), and comparison of T/2 values for simulated (s) and experimental (e, identical to bars in (b)) recovery. Actual and simulated FRAP data are shown for control (c), LatB-treated (d) and Δrdi1 (e) cells.

The mobility of Cdc42 is a major element in any dynamic polarization model. We performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments to monitor Cdc42 recycling. In agreement with previous measurements14,17, recovery of Cdc42 fluorescence in control cells occurred with an average T/2 of 2.2 s, and was independent of Cdc42 expression level (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. S3a). Disruption of actin structures with LatB led to a slightly increased T/2 of 2.5 s (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. S3a). This slower recovery was proposed to result from greater accumulation of Cdc42 in caps21. However, Cdc42 cap intensities in LatB-treated cells were significantly reduced (Fig. 3a), supporting a positive role for actin in Cdc42 polarization. Perturbation of Cdc42–Rdi1 interactions by deletion of RDI1 or the use of the Cdc42R66E mutant drastically slowed recovery to a T/2 of 10 s (Fig. 5b), confirming previous work on polarity maintenance17. Our results confirm that Rdi1- and actin-dependent Cdc42 recycling act in parallel during polarity establishment and show that the pathways act on different time scales. All values for Cdc42 mobility could be accurately reproduced in our model (Fig. 5c–e, Supplementary Table S3).

Validating the model

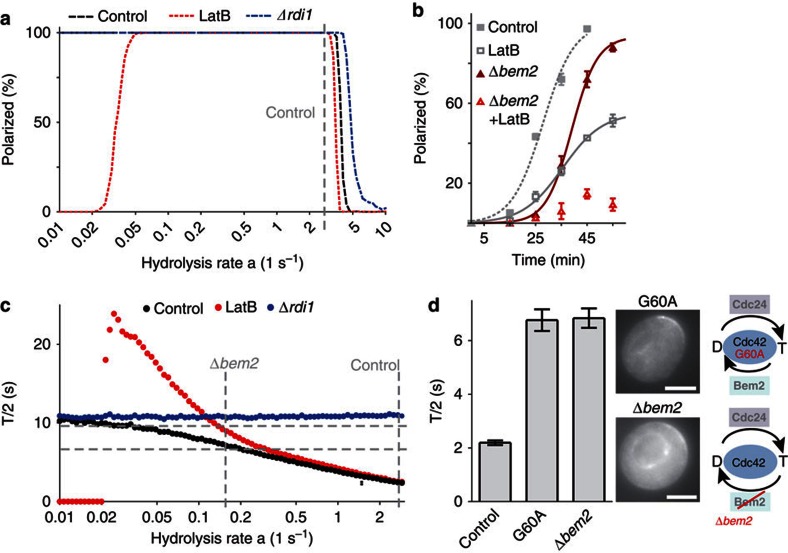

Our model was able to reproduce characteristics of Cdc42 mobility and distribution under various experimental conditions. Next, we searched for model predictions that we could validate experimentally. One critical aspect of the model is the fact that GDI-mediated extraction is restricted to GDP-Cdc42, predicting loss of polarization in LatB-treated cells at very low rates of hydrolysis (Fig. 6a). The hydrolysis rate in control cells, estimated by fitting values for cap height/width and FRAP times, was 2.74 s−1 (grey dashed line Fig. 6a). To check the model-based prediction we reduced GTP hydrolysis on Cdc42 by deleting BEM2, the GAP with the largest number of genetic interactions with actin (Fig. 2a). Cdc42 in Δbem2 cells was able to polarize efficiently, albeit with slightly reduced speed (Fig. 6b). However, when actin was disrupted most Δbem2 cells could no longer polarize (Fig. 6b). Similar results were obtained when monitoring Cdc24 or Bem1 (Supplementary Fig. S3d). In our simulations polarization occurred over a wide range of hydrolysis values, with the control rate being close to the maximum permissible before polarization breaks down (Fig. 6a). To study the impact of changes in hydrolysis rates on a more quantifiable parameter, we tested the effect of deleting BEM2 on Cdc42 mobility. The model predicted a gradual increase in T/2 upon reduction of the GTP hydrolysis rate (Fig. 6c). This slowdown was expected to be more pronounced in LatB-treated cells. In agreement with this prediction, in Δbem2 cells and the slow-acting mutant Cdc42G60A (ref. 48), FRAP halftimes increased to 6.7 and 6.8 s, respectively, (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Table S3). In our model this recovery rate corresponds to a roughly 16-fold decrease in the rate of GTP hydrolysis to (grey dashed lines in Fig. 6c). At this hydrolysis rate, Cdc42 in LatB-treated cells is predicted to recycle with a T/2 of 8.7 s—a value close to the measured 9.6 s for LatB-treated Δbem2 cells (Supplementary Table S3). Hence, our results indicate that the contribution of actin to Cdc42 recycling is increased in Δbem2, likely due to reduced extraction of active Cdc42 by its GDI.

Figure 6. Effects of GTP hydrolysis on polarization efficiency and Cdc42 dynamics.

(a) Predicted dependence of polarization efficiencies in control, LatB-treated and Δrdi1 cells on the rate of GTP hydrolysis. The hydrolysis rate for control cells (a=2.74 s−1) was estimated by fitting model parameters (Figs 4, 5), and is indicated by the vertical dashed grey line. (b) Polarization efficiency of Cdc42 in control and Δbem2 cells in the presence or absence of LatB. Data points represent means of three experiments with 50 cells each. Error bars indicate s.d. The lines are sigmoidal fits. (c) Plot of simulated Cdc42 FRAP T/2 (mean values from 400 runs/data point) against rate of GTP hydrolysis. Fitted and estimated hydrolysis rates in control and Δbem2 cells are indicated as vertical dashed grey lines. T/2 values measured in Δbem2 cells without (6.8 s; n=20) and with LatB (9.6 s, n=12) are indicated as horizontal dashed grey lines. (d) FRAP T/2 and localization of Cdc42 in Δbem2 cells and in cells expressing Cdc42G60A (n=11), a mutant with a lower GTPase activity. Bars represent means±s.e.m. Schematics illustrate changes in the Cdc42 GTPase cycle. Scale bar, 4 μm.

The mechanism of formation of multiple polarization sites

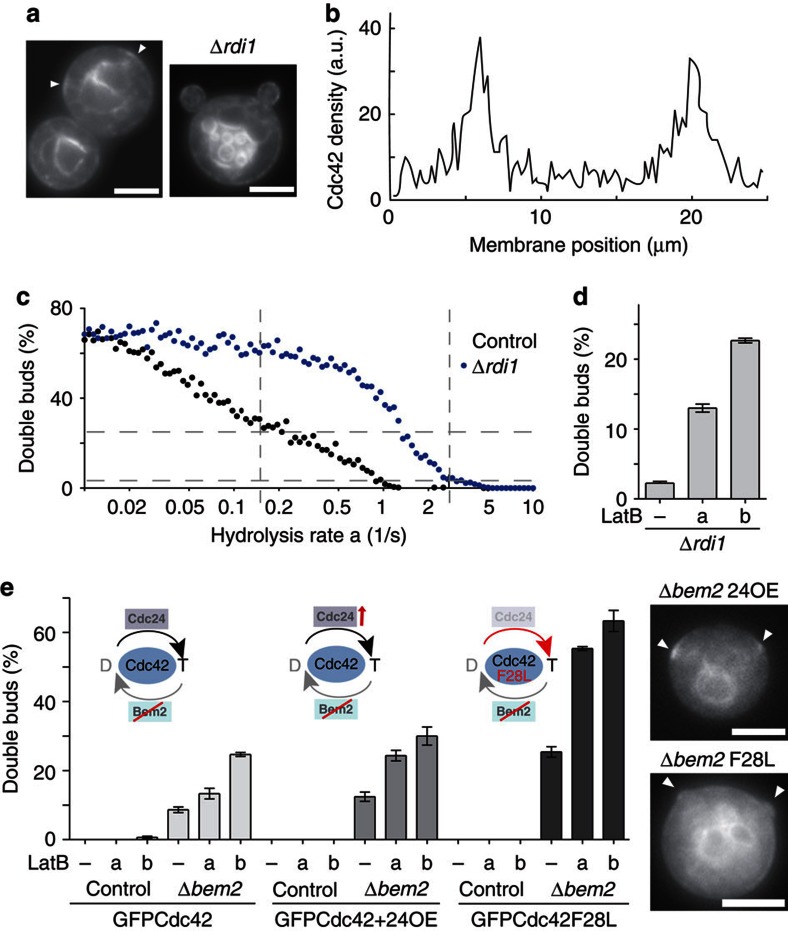

In all our simulations, the GDI pathway alone was never able to generate multiple stable polarization site. However, yeast cells are capable of simultaneously polarizing at two or more sites, for example, after deletion of BEM2 (ref. 49), deletion or overexpression of BEM1 (refs 14, 16) or overexpression of constitutively active Cdc42 (ref. 13). Interestingly, we noticed that 2.3±0.5% (n=4 × 100 cells) of Δrdi1 cells formed two stable polarization sites (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Table S4), a value that could be reproduced in our model after fitting the actin-mediated pathway (Fig. 7b, grey dashed line at a=2.74 s−1). Varying parameters in the model generated two testable predictions. First, increased Cdc42 activation should strongly increase the percentage of Δrdi1 cells that form multiple polarization sites (Fig. 7c, blue curve). Second, even cells with a functional GDI should form multiple caps if rates of GTP hydrolysis are reduced sufficiently (Fig. 7c, black curve). Rdi1-mediated recycling of Cdc42 alone was unable to generate multiple stable caps in our simulations. The formation of multiple caps at lower hydrolysis rates can be explained by the reduction or loss of the ability of GDI-mediated recycling to restrict cap formation to a single-polarization site and the enhanced nucleation of actin at higher levels of Cdc42-GTP. To increase Cdc42 activity in Δrdi1 cells, we exploited the known cell cycle-dependent activation of Cdc42 after the G1/S transition49,50. We released Δrdi1 cells from G1 arrest in the presence of LatB to prevent immediate polarization and washed the drug out at different times to allow polarization with varying initial Cdc42 activity (Supplementary Fig. S5a). As predicted, the number of cells with two polarization sites increased from 2.3–13% and 23% with increasing duration of drug treatment and hence increasing level of Cdc42 activity (Fig. 7d, Supplementary Table S4). Next, we used Δbem2 cells to increase Cdc42 activity in the presence of Rdi1. We found that similar to a previous report49, 8.7% of cells formed two buds (Fig. 7e), and this was independent of the GFP tag, strain background or Cdc42 expression level (Supplementary Fig. S5, Supplementary Table S4). We further increased Cdc42 activity by overexpressing Cdc24 (Supplementary Fig. S5d) or expressing a Cdc42 mutant with high intrinsic GDP release rate (Cdc42F28L (ref. 51)). Neither treatment induced formation of double buds in control cells (Fig. 7e, Supplementary S5c). However, in Δbem2 strains the number of cells forming multiple polarization sites increased significantly (Fig. 7e, Supplementary S5c). Our results indicate that actin-mediated recycling of Cdc42 is prone to creating multiple polarization sites, and that this effect is sensitive to the level of Cdc42 activity. Moreover, our results show that perturbation of GDI-mediated polarization can induce formation of multiple buds in otherwise wild-type cells.

Figure 7. Formation of multiple polarization sites.

(a) Examples of simultaneous formation of two Cdc42 caps (arrows) and buds in Δrdi1 cells. Scale bar, 4 μm. (b) Intensity profile illustrating formation of two caps in a simulated Δrdi1 cell. (c) Predicted effects of varying the rate of GTP hydrolysis on formation of multiple polarization sites in simulations of control and Δrdi1 cells. Fitted and estimated hydrolysis rates in control and Δbem2 cells are indicated as vertical dashed grey lines. Percentage of double buds observed in Δbem2 cells after washing LatB out (25%, n=300) and in Δrdi1 cells (2.3%, n=400) are indicated as horizontal dashed grey lines. See also Supplementary Table S7. (d) Effect of washout of LatB on the percentage of Δrdi1 cells with two buds. Cells were treated with LatB for 20 min (a) or 40 min (b) before washout of the drug or without treatment (−). See Supplementary Methods for experimental details. (e) Effect of Cdc42 activity level on the formation of double buds in control and Δbem2 cells. Cells expressing GFPCdc42, GFPCdc42 and Cdc24RFP or GFPCdc42F28L (a mutant with fast intrinsic GDP exchange) were treated with LatB as in (d). Examples of double cap formation in Δbem2 cells expressing either GFPCdc42 or GFPCdc42F28L are shown on the right. Bars represent means±s.e.m. for three experiments with 100 cells each. Schematics illustrate changes in the Cdc42 GTPase cycle. Scale bar, 4 μm.

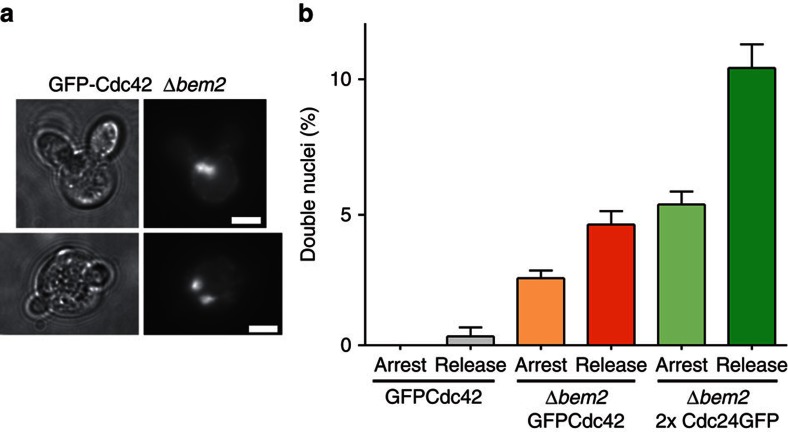

Although formation of two polarization sites in a small percentage of cells in a population might, at first sight, seem tolerable, even slight effects on cell division could translate into a strong evolutionary disadvantage. Indeed, we found that the formation of multiple buds directly correlated with an increased number of mis-segregated nuclei (Fig. 8a) and this effect was dependent on increased activity of Cdc42 (Fig. 8b). On average, more than 20% of cells with double buds also exhibited defects in nuclear segregation (Figs 8b, 7e). Formation of multiple buds therefore likely has direct impact on cell survival.

Figure 8. Multiple polarization sites and DNA segregation.

(a) Examples of Δbem2 cells displaying two nuclei and two buds. Scale bar, 4 μm. (b) Percentage of cells with two nuclei in controls and in Δbem2 cells expressing GFPCdc42 or two copies of Cdc24GFP. Bars represent means±s.e.m. for three experiments with 100 cells each.

Discussion

We have shown that yeast cells can establish polarity by localizing the central polarity regulator Cdc42 through a combination of two recycling pathways with distinct mechanistic features. GDI-dependent recycling of Cdc42 is fast and coupled to the GTPase cycle of Cdc42. Symmetry breaking in this pathway occurs via a combination of positive feedback loops for activation and recruitment of Cdc42, is characterized by efficient formation of a unique polarization axis, but is sensitive to perturbations in the GTPase cycle of Cdc42. In contrast, actin-mediated recycling of Cdc42 is slower and depends solely on Cdc42 activity13. The use of actin cables for delivery of Cdc42 to the plasma membrane leads to formation of very stable polarization sites. However, this stability comes with a significant risk of stochastically generating multiple stable polarization sites—an effect that becomes especially prominent if Cdc42 activity is increased. By combining the two recycling pathways, yeast cells ensure reliable establishment of a unique polarity axis.

To quantitatively analyse the interplay between Cdc42 recycling pathways, we built a particle-based mechanistic model for polarity establishment and performed extensive stochastic simulations. We kept the model complexity at a level that was appropriately supported by experimental evidence. We used measurements from a variety of quantitative in vivo and in vitro experiments to validate and constrain assumptions and parameters. This integrated approach allowed us to make detailed predictions concerning polarization efficiency, protein localization kinetics and number of polarization sites, which were confirmed with remarkable accuracy by our experimental data.

Two key features in our model should be emphasized. First, we found that polarity establishment in yeast did not sensitively depend on the quantity of Cdc42 in the cell. This was also observed in our simulations, where a 10-fold increase in Cdc42 concentration failed to prevent polarization (N(Cdc42)=3,000–30,000 yield 100% polarization). These findings contradict a recent study, in which stochastic polarization of Cdc42 was proposed to depend critically on low expression levels30. Instead, we find that polarization depends on the level of Cdc42 activity. Second, because of separate positive feedback in Cdc42 activation (Cdc42GTP–GEF–Bem1–Cla4 interactions) and Cdc42 recruitment (GEF–GDI competition), our model does not depend on non-linear recruitment of the GEF, which was required for polarization in a previous model28 and was not supported by our experiments.

Our results indicate that yeast cells did not simply evolve two redundant polarization pathways to safeguard an essential process against random error. Instead they combine positive features of both pathways to simultaneously achieve reliability and spatial precision in cell polarization. Such an optimized interplay of pathways requires precise selection of parameter values. Indeed, our results suggest that the GTPase cycle of Cdc42 has a central role in coordinating pathways underlying polarity establishment. In particular, the Cdc42 hydrolysis rate is restricted to a rather narrow range between roughly 1 and 3 s. Faster rates lead to a loss of polarization due to insufficient amounts of active Cdc42 in the cell (Fig. 6a), although slower hydrolysis leads to formation of multiple buds (Fig. 7c). The latter effect is a result of a reduced recycling speed and hence smaller contribution for the GDI pathway (Fig. 6c) and a simultaneous failure of the actin pathway to focus polarization to a single site if Cdc42 activity is increased (Fig. 7c). GDI recycling therefore needs to be faster than the actin pathway to ensure polarization at a single site and in our simulations Cdc42 in control cells seems to indeed hydrolyse GTP with nearly maximal possible speed. At the other extreme, if the GDI pathway is deleted, cells become very prone to form multiple caps (Fig. 7c).

Our results provide a mechanistic link between the fast GTPase cycle and GDI-mediated membrane recycling of Rho GTPases. Similar interactions have also been reported for small GTPases of the Rab family52. The mechanisms we identified for localization of Cdc42 might therefore also be applicable for other processes of spatial cellular organization.

Our proposed model was capable of reproducing all our experimental results and made several accurate and quantitative predictions. However, there are still many open questions concerning the biophysical and biochemical basis for cell polarization. For example, it has recently been demonstrated that lipid composition at the polarized site, in particular negatively charged phospholipids, influence the association of Cdc42 with the plasma membrane and hence impact on cell polarity53,54. Furthermore, although we assumed cell cycle-dependent activation of Cdc24 and inactivation of Bem2 in the LatB washout experiments (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. S5), the detailed biochemistry of these regulatory processes is not fully understood and they were not included in the mathematical model. Finally, we did not consider potential regulation of GDI–Cdc42 interaction or GDI-membrane interaction by phosphorylation55. All these additional aspects provide ample scope for future improvements in both modelling and mechanistic understanding of cell polarization. As nicely summarized in a recent review, the value of a mathematical model should be judged ‘not by how complex and detailed it is, but by what could be learned from it’47. Our current model consequently incorporates the minimum degree of complexity compatible with generation of meaningful forecasts, and was able to reflect and predict basic properties of cellular organization that will hopefully help to rationalize a variety of different biological processes.

Methods

Cell culture and plasmids

All strains are derived from RWS116, in which only one G1 cyclin, CLN2, is expressed under the control of a methionine repressible promoter. Unless otherwise stated, cells were grown at RT in SC-Met medium containing 2% glucose. Cells were arrested in G1 by addition of 3 mM methionine for 4 h and released again by washing twice and resuspension in methionine-free medium. To verify strain growth, three-fold serial dilutions of an equal amount of logarithmically growing cells were spotted as triplicate onto Sc-Met plates and incubated at indicated temperatures for 2 days. Standard genomic manipulation procedures56 were used for GFP integrations or gene deletions. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed as described57. Strains, plasmids and primers are listed in Supplementary Tables S8–S10, respectively.

Immunoblot analyses

Total protein extracts of 1.4 × 107 cells were boiled in SDS-sample buffer and analysed by SDS–PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with a polyclonal Cdc42 serum (1:500; sc-6793; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or with a monoclonal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (1:1500; ab 125247, Abcam). Immunoblots were visualized using a Fuji-Las3000 imager. Quantification of bands was performed in ImageJ.

Interaction screen

We used the following set of query proteins: Cdc42, Cdc24, Bem2, Bem3, Rga1 and Rga2, Rdi1, Bem1 and Cla4. Physical and genetic interaction partners were collected from public databases (BioGRID58, MPACT59). Physical interactions included data from affinity purification, co-crystallization, FRET, PCA, protein–peptide interaction, reconstituted complexes and two-hybrid. Genetic interactions represented synthetic growth defects, haploinsufficiencies and synthetic lethality. We only considered negative interactions from synthetic genetic array screens. Interaction partners involved in actin-related processes were grouped in four categories: actin general (actin patches or cables), early secretion (ER-to-Golgi transport), late secretion (Golgi-to-plasma membrane transport) and endocytic recycling. All identified interactions are listed in Supplementary Tables S1,S2. For each query the number of interactions with members of each category were extracted. The number of unique interactions in each functional group served as a measure of the overall strength of interaction with that group and was colour-coded in a heat map (see Fig. 1a).

Microscopy and imaging

Coverslips were coated with ConA (2 mg ml−1, Sigma). Raw images were used for all quantifications and analyses. Polarization and washout experiments were performed on a Zeiss Axio Imager.A1 upright microscope with 1.4 NA × 100 objective, an X-Cite120 light source (Lumen Dynamics) and an iXON DU-897 EMCCD camera (Andor) coupled to a × 2 magnification ring. Images were acquired with Metamorph 7.0 software.

Images for FRAP experiments were acquired on a custom-built setup from Till Photonics based on an iMic stand with Olympus 1.45 NA × 100 objective and iXON DU-897 EMCCD camera. Four hundred eighty-eight nanometre (Coherent) and 561 nm (Cobolt) lasers were directed through an AOTF and coupled into the iMic. A galvanometer allowed switching between FRAP and epifluorescence modes. Two additional galvanometers were used to adjust laser incidence angles or FRAP positions. For FRAP, caps were selected 10–20 min after release from G1 arrest. Acquisition was controlled by the Live Acquisition software.

Drug treatments and staining

Actin disruption

Cells were released in medium containing 400 μM LatB. In washout experiments, LatB was added for 20 or 40 min, and then removed by washing twice. Polarization was monitored after 40–60 min. FM4-64 staining: cells were incubated in 0.32 μM FM4-64 for 2 min and washed once.

DAPI-staining

One millilitre cells were released for 2–25 h, fixed with 3% formaldehyde for 2 h, washed twice and resuspended in 30 μl PBS+0.1% Triton. Fixed cells were then incubated with 0.1 μg ml−1 DAPI for 10 min and washed twice with PBS.

FRAP analysis

To quantify fluorescence recovery MATLAB (MathWorks, 2010a) routines were implemented. Intensities in the bleached region were corrected for background fluorescence and total cellular fluorescence. The recovery curve was fitted with a double exponential function yfit(t)=a(1-b(exp(-tc))-d(exp(-te)). The fast component corresponded to diffusion of soluble Cdc42 in the cytosol and the slower component ro recovery of membrane-bound Cdc42 pool via a combination of GDI- and actin-mediated mechanisms. The halftime for the slower component, t21/2=−log(0.5)/e was used for further comparison. Time stamps were automatically extracted from the metadata. Data points were only used if reliable fits could be generated (residual sum of squares >0.95). Means and s.e.m. were calculated from >10 independent experiments (Supplementary Table S3).

Calculation of cap width and height

For measurements of cap width and height, GFP-Cdc42 caps were identified from medial cross-sections and a region Rcap was drawn around the perimeter of the cap. A background region Rbg was selected inside the same cell. Background signal I0 from the camera chip was calculated from a region distant from any cell. Cap height H was calculated as H=(I(Rcap)−I0)/ (I(Rbg)−I0). Cap width W corresponded to the size of the cap area Rcap. Total intensitiy Itot was calculated as Itot=H*W.

Protein purification

His6-tagged Cdc42 was purified from baculovirus-infected Sf21 insect cells. All purification steps were performed at 4 °C. Stirred 1l cultures of Sf21 cells were infected for 48 h by Kinnakeet Biotechnology (Midlothian, VA). Cell pellets were resuspended in 40 ml hypotonic buffer (20 mM sodium borate pH 10.2, 5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM PMSF, 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin and leupeptin) and disrupted by Dounce homogenization.

Membrane-containing components of the lysate were spun down at 1,50,000 g in a Ti70 rotor (Beckman Coulter) for 20 min and resuspended in 50 ml TBSM (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2). The procedure was repeated twice and the final pellet was resuspended in TBSM+1% Triton-X100. The lysate was further homogenized and agitated for 30 min on a rotisserie, resulting in solubilization of geranylgeranylated Cdc42. The remaining insoluble fraction was pelleted in a tabletop centrifuge at 9,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C and discarded. The supernatant containing detergent-solubilized, isoprenylated His6-tagged Cdc42 was incubated for 30 min with chelating Sepharose beads (Qiagen) charged with Ni2+. Beads were then washed with 400 ml high salt buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 700 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% CHAPS, 20 mM imidazole) and protein was eluted with 10 ml elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% CHAPS, 500 mM imidazole). The fractions containing Cdc42 were pooled and concentrated to 2 ml. His6-tagged prenylated Rac1 was purified in the same manner as Cdc42.

N-terminal GST fusions to human RhoGDI and to the GAP domain of Cdc42-GAP (human, residues 234-462) as well as N-terminally His6-tagged DHR2C domain of human Dock180 were purified from E. coli cells. Cells were grown at 37 °C to OD 0.8. Protein expression was induced by 1 mM IPTG for 3 h before pelleting at 6,000 g for 10 min. Cell pellets were homogenized in TBSM and lysed by sonication. Extracts were spun at 20,000 g for 30 min. Supernatants with GST-tagged proteins were incubated with glutathione beads and equilibrated with TEDA buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM sodium azide) for 30 min at 4 °C. Beads were washed with several column volumes of TEDA-containing 500 mM NaCl and protein was eluted with 10 mM glutathione in TBSM. His6-tagged DHR2 domain was purified on Sepharose beads charged with Ni2+ as described above. All proteins were concentrated in 10 MWC Amicon Ultra concentrators.

Liposome binding assays

Liposomes were prepared by extrusion using Avanti mini-extruders (1 or 8 μm membranes) followed by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min and resuspension in TBSM. Lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. The standard lipid composition in molar percentages was 35% PE, 25% PS, 5% PI and 35% cholesterol (Nu Chek Preps).

For Cdc42–liposome association assays a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorimeter was used in the counting mode. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 365 and 440 nm, respectively. Samples were stirred continuously at 25 °C in TBSM. To prepare HAF (hexadecanoylaminofluorescein)-labelled lipids for FRET assays, 1.25 nmol of HAF (Molecular Probes) was vortexed with 50 μl of lipids (1 mg ml−1). To monitor release of Cdc42 from liposomes, Cdc42 was preloaded with methylanthraniloyl-modified (Mant) nucleotide and incubated with 30 μl of HAF-containing liposomes at RT for 5 min. The mixture was added to the cuvette, bringing the final Cdc42 concentration to 40 nM. At the indicated time points, 50 nM RhoGDI and 10 nM Cdc42-GAP were added, and fluorescence was recorded for 20 min. Traces monitored the changes in Mant fluorescence due to changes in FRET between Mant-nucleotide-bound Cdc42 and liposomes containing HAF.

Statistics and data analysis

Curve fitting for polarization curves was done with Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla) using a sigmoidal dose-response equation y=bottom+(top–bottom)/(1+10^((LogEC50-X)*Hill Slope)). Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed to validate significance of differences.

Author contributions

T.F., B.K., E.F. and R.W.-S. conceived the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. T.F., G.P. and G.B. performed experiments. B.K. and E.F. built mathematical models and performed simulations. J.J. performed protein purifications and liposome assays with help from R.A.C. M.C. and C.B. provided SGA data and expertise.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Freisinger, T. et al. Establishment of a robust single axis of cell polarity by coupling multiple positive feedback loops. Nat. Commun. 4:1807 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2795 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S5, Supplementary Tables S1-S10, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Li for strains and P. Hardy for editing. This work was supported by the Max Planck society (R.W.-S.) and the DFG (SFB 863: R.W.-S., E.F.; Nano-Initiative Munich (NIM): E.F.).

References

- Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42--the centre of polarity. J. Cell. Sci. 117, 1291–1300 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S. Lipid rafts: elusive or illusive? Cell 115, 377–388 (2003) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman T. J., Sawyer M. M. & Johnson D. I. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc42p localizes to cellular membranes and clusters at sites of polarized growth. Eukaryot. Cell 1, 458–468 (2002) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziman M. & Johnson D. I. Genetic evidence for a functional interaction between Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC24 and CDC42. Yeast 10, 463–474 (1994) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne D., Gao L., Bi E. & Bretscher A. Stable and dynamic axes of polarity use distinct formin isoforms in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4971–4989 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral Y., Mermall V., Mooseker M. S. & Snyder M. Compartmentalization of the cell cortex by septins is required for maintenance of cell polarity in yeast. Mol. Cell 5, 841–851 (2000) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. O. & Bi E. Central roles of small GTPases in the development of cell polarity in yeast and beyond. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71, 48–96 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedlich-Soldner R. & Li R. Closing the loops: new insights into the role and regulation of actin during cell polarization. Exp. Cell Res. 301, 8–15 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G. et al. Association of the Rho family small GTP-binding proteins with Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor (Rho GDI) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Oncogene 15, 417–422 (1997) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedje C., Sakwa I., Just U. & Hofken T. The Rho GDI Rdi1 regulates Rho GTPases by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2885–2896 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. M., Jin M. & Lew D. J. Symmetry breaking and the establishment of cell polarity in budding yeast. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 21, 740–746 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter B. D., Smith S. E. & Li R. Symmetry breaking in the life cycle of the budding yeast. Cold Spring Harbor Pers. Biol. 1, a003384 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedlich-Soldner R., Altschuler S., Wu L. & Li R. Spontaneous cell polarization through actomyosin-based delivery of the Cdc42 GTPase. Science 299, 1231–1235 (2003) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedlich-Soldner R., Wai S. C., Schmidt T. & Li R. Robust cell polarity is a dynamic state established by coupling transport and GTPase signaling. J. Cell Biol. 166, 889–900 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irazoqui J. E., Gladfelter A. S. & Lew D. J. Scaffold-mediated symmetry breaking by Cdc42p. Nat. Cell. Biol. 5, 1062–1070 (2003) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozubowski L. et al. Symmetry-breaking polarization driven by a Cdc42p GEF-PAK complex. Curr. Biol. 18, 1719–1726 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter B. D., Das A., Schwartz J. W., Rubinstein B. & Li R. Dual modes of cdc42 recycling fine-tune polarized morphogenesis. Dev. Cell 17, 823–835 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris K. P. & Tepass U. Cdc42 and vesicle trafficking in polarized cells. Traffic 11, 1272–1279 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmani N., Peglion F., Chavrier P. & Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42 localization and cell polarity depend on membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 191, 1261–1269 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irazoqui J. E., Howell A. S., Theesfeld C. L. & Lew D. J. Opposing roles for actin in Cdc42p polarization. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1296–1304 (2005) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage N. S., Layton A. T. & Lew D. J. Mechanistic mathematical model of polarity in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 1998–2013 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T. et al. Initial polarized bud growth by endocytic recycling in the absence of actin cable-dependent vesicle transport in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1237–1252 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbudak E. M., Becskei A. & van Oudenaarden A. A system of counteracting feedback loops regulates Cdc42p activity during spontaneous cell polarization. Dev. Cell 9, 565–571 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell A. S. et al. Negative feedback enhances robustness in the yeast polarity establishment circuit. Cell 149, 322–333 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton A. T. et al. Modeling vesicle traffic reveals unexpected consequences for Cdc42p-mediated polarity establishment. Curr. Biol. 21, 184–194 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose I. et al. Assembly of scaffold-mediated complexes containing Cdc42p, the exchange factor Cdc24p, and the effector Cla4p required for cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation of Cdc24p. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7176–7186 (2001) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butty A. C. et al. A positive feedback loop stabilizes the guanine-nucleotide exchange factor Cdc24 at sites of polarization. EMBO J. 21, 1565–1576 (2002) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goryachev A. B. & Pokhilko A. V. Dynamics of Cdc42 network embodies a Turing-type mechanism of yeast cell polarity. FEBS Lett. 582, 1437–1443 (2008) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R., Toshima J. Y. & Toshima J. Regulation of clathrin coat assembly by Eps15 homology domain-mediated interactions during endocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 687–700 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler S. J., Angenent S. B., Wang Y. & Wu L. F. On the spontaneous emergence of cell polarity. Nature 454, 886–889 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilkine A., Angenent S. B., Wu L. F. & Altschuler S. J. A density-dependent switch drives stochastic clustering and polarization of signaling molecules. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002271 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter E. et al. Regulation of Rho GTPase crosstalk, degradation and activity by RhoGDI1. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 477–483 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M. et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science 327, 425–431 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson R. M. & Wilson-Delfosse A. L. RhoGDI-binding-defective mutant of Cdc42Hs targets to membranes and activates filopodia formation but does not cycle with the cytosol of mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 359, 285–294 (2001) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann D. J., Stefan C. J., Babst M. & Emr S. D. Vps27 recruits ESCRT machinery to endosomes during MVB sorting. J. Cell Biol. 162, 413–423 (2003) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter B. D. et al. Non-uniform membrane diffusion enables steady-state cell polarization via vesicular trafficking. Nat. Commun. 4, 1380 (2013) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco E., Wedlich-Soldner R., Li R., Altschuler S. J. & Wu L. F. Endocytosis optimizes the dynamic localization of membrane proteins that regulate cortical polarity. Cell 129, 411–422 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R. & Munro S. Sorting of membrane proteins in the secretory pathway. Cell 75, 603–605 (1993) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. L., Erickson J. W. & Cerione R. A. New insights into how the Rho guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor regulates the interaction of Cdc42 with membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23860–23871 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoebel S., Oesterlin L. K., Blankenfeldt W., Goody R. S. & Itzen A. RabGDI displacement by DrrA from Legionella is a consequence of its guanine nucleotide exchange activity. Mol. Cell 36, 1060–1072 (2009) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolev Y., Berdichevsky Y., Weinbaum C. & Pick E. Dissociation of Rac1(GDP).RhoGDI complexes by the cooperative action of anionic liposomes containing phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor, and GTP. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22257–22271 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dransart E., Olofsson B. & Cherfils J. RhoGDIs revisited: novel roles in Rho regulation. Traffic 6, 957–966 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers L., Yelon D., Berg L. J. & Chant J. Regulation of the polarization of T cells toward antigen-presenting cells by Ras-related GTPase CDC42. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5027–5031 (1995) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung V. et al. Two types of RAS mutants that dominantly interfere with activators of RAS. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 3707–3718 (1994) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onsum M. D. & Rao C. V. Calling heads from tails: the role of mathematical modeling in understanding cell polarization. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 74–81 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell A. S. et al. Singularity in polarization: rewiring yeast cells to make two buds. Cell 139, 731–743 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogilner A., Allard J. & Wollman R. Cell polarity: quantitative modeling as a tool in cell biology. Science 336, 175–179 (2012) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviston J. P., Tcheperegine S. E. & Bi E. Singularity in budding: a role for the evolutionarily conserved small GTPase Cdc42p. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12185–12190 (2002) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus M. et al. Phosphorylation of Bem2p and Bem3p may contribute to local activation of Cdc42p at bud emergence. EMBO J. 26, 4501–4513 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nern A. & Arkowitz R. A. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the Cdc42p exchange factor Cdc24p. J. Cell Biol. 148, 1115–1122 (2000) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Fuji R. N., Yang W. & Cerione R. A. RhoGDI is required for Cdc42-mediated cellular transformation. Curr. Biol. 13, 1469–1479 (2003) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. W. et al. Membrane targeting mechanism of Rab GTPases elucidated by semisynthetic protein probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 534–540 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A. et al. Flippase-mediated phospholipid asymmetry promotes fast Cdc42 recycling in dynamic maintenance of cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 304–310 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairn G. D., Hermansson M., Somerharju P. & Grinstein S. Phosphatidylserine is polarized and required for proper Cdc42 localization and for development of cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1424–1430 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerMardirossian C. & Bokoch G. M. GDIs: central regulatory molecules in Rho GTPase activation. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 356–363 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke C. et al. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21, 947–962 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J.a.R., D. W. Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual 3rd Edn Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor: New York, (2001) . [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz B. J. et al. The BioGRID Interaction Database: 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D637–D640 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewes H. W. et al. MIPS: curated databases and comprehensive secondary data resources in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D220–D224 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S5, Supplementary Tables S1-S10, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References