Abstract

We previously synthesized dendrogenin A and hypothesized that it could be a natural metabolite occurring in mammals. Here we explore this hypothesis and report the discovery of dendrogenin A in mammalian tissues and normal cells as an enzymatic product of the conjugation of 5,6α-epoxy-cholesterol and histamine. Dendrogenin A was not detected in cancer cell lines and was fivefold lower in human breast tumours compared with normal tissues, suggesting a deregulation of dendrogenin A metabolism during carcinogenesis. We established that dendrogenin A is a selective inhibitor of cholesterol epoxide hydrolase and it triggered tumour re-differentiation and growth control in mice and improved animal survival. The properties of dendrogenin A and its decreased level in tumours suggest a physiological function in maintaining cell integrity and differentiation. The discovery of dendrogenin A reveals a new metabolic pathway at the crossroads of cholesterol and histamine metabolism and the existence of steroidal alkaloids in mammals.

It has been hypothesized that the steroidal alkaloid dendrogenin A (DDA) is a natural metabolite. de Medina et al. show that DDA is produced in mammalian tissues from 5,6α-epoxy-cholesterol and histamine metabolism, and that the compound displays cell differentiation and anti-tumour activities.

It has been hypothesized that the steroidal alkaloid dendrogenin A (DDA) is a natural metabolite. de Medina et al. show that DDA is produced in mammalian tissues from 5,6α-epoxy-cholesterol and histamine metabolism, and that the compound displays cell differentiation and anti-tumour activities.

Cholesterol epoxide hydrolase (ChEH; EC 3.3.2.11) is a microsomal enzyme that is ubiquitous in mammalian tissues and selectively catalyses the hydrolysis of the cholesterol epoxides, 5,6α-epoxy-cholesterol (5,6α-EC) and 5,6β-epoxy-cholesterol (5,6β-EC), into cholestan-3β,5α,6β-triol (CT)1. The ChEH activity is carried out by the anti-oestrogen binding site (AEBS), a high-affinity binding site for the anti-tumour drug Tamoxifen (Tam) and other selective oestrogen receptor (ER) modulators2,3,4,5,6. ChEH is a heterodimeric complex formed by 3β-hydroxysteroid-Δ8-Δ7-isomerase (D8D7I) and 3β-hydroxysteroid-Δ7-reductase (DHCR7)4. D8D7I and DHCR7 are involved in the biosynthesis of cholesterol4,6,7, organ development8, cell differentiation and cell death5,9,10. All AEBS ligands are inhibitors of ChEH, and this inhibition of ChEH results in an accumulation of 5,6-ECs that contributes to the anti-cancer pharmacology of AEBS ligands, including Tam2,3,7,9,11. Importantly, Tam is a major drug used in the treatment of ER-positive breast cancers, and consequently a great number of patients worldwide are taking Tam, which makes it very relevant to study 5,6-EC metabolism12. One peculiarity of epoxide-bearing substances is their instability due to the high reactivity of the epoxide ring towards nucleophiles including amines, thiols and hydroxyl groups that are found in bio-macromolecules and biological media13,14. Surprisingly, 5,6-ECs were found to be different from other epoxide-bearing substances in that they do not react spontaneously with nucleophiles, including amines, thus making 5,6-ECs extremely stable in biological media11,15.

Interestingly, several lines of evidence point to the existence of active metabolites of 5,6α-EC. Stereo-selective biosynthesis of 5,6α-EC occurs in the adrenal cortex by a currently unidentified cytochrome p45016. 5,6α-EC and its sulfated derivative 5,6α-epoxy-5α-cholestestan-3β-sulphate are modulators of the liver-X-receptor (LXR)9,17,18. 5,6α-EC can also be metabolized into 3β,5α-dihydroxycholestan-6β-yl-S-glutathione19,20. We reported that the aminolysis of 5,6α-EC, but not 5,6β-EC, was possible under strong catalytic conditions and gave alkylaminooxysterols11,15,21. Among these steroidal alkaloids, dendrogenin A (DDA) (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1) was chemically synthesized21 based on the hypothesis that DDA could be a natural metabolite in mammals and could result from the enzymatic conjugation of 5,6α-EC with histamine (His) at the level of the AEBS that binds both 5,6-ECs and His22. In vitro studies showed that DDA induced tumour cell re-differentiation and death in various tumour cells21. For example, we found that DDA triggered in vitro cell-cycle arrest in melanoma and breast cancer cells and activated melanogenesis and lactation, respectively, at lower concentrations than all trans-retinoic acids and Tam21. By contrast, the regioisomer of DDA, compound 17 (C17)21 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1), was inactive in these tests, thus showing a regio-selectivity of action for these compounds21. In the present study, we investigated whether DDA is a naturally occurring metabolite in mammals. More generally, this question was motivated by the fact that no steroidal alkaloid has been discovered in mammals, while some have been isolated from plants, amphibians and ancestral fishes23. These molecules, such as squalamine and other analogues that have been isolated from several tissues of the dogfish shark Squalus acanthias and the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus, show important pharmacological and therapeutic functions. For example, squalamine exhibits host defence, anti-angiogenic and anti-tumour activities against different tumours24,25,26,27.

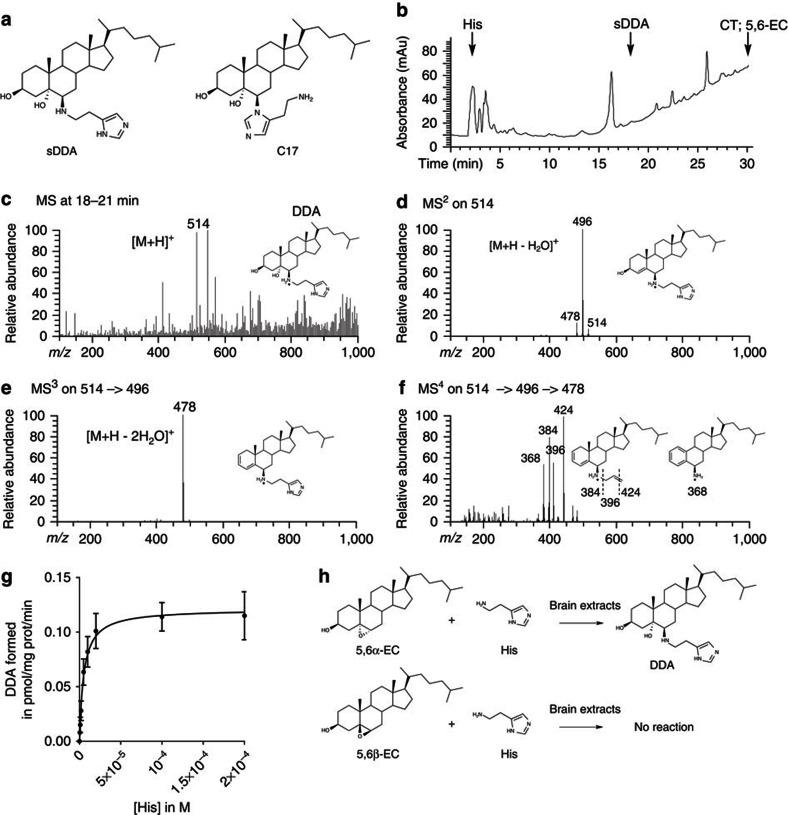

Figure 1. Characterization and formation of DDA in mouse brain homogenates.

(a) Chemical structure of sDDA and synthetic C17. (b) HPLC profile from a total mouse brain extract. The extraction of sterols and HPLC separation were carried out as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Arrows indicate peaks corresponding to the authentic standards: His, sDDA, CT and 5,6-EC. The fractions collected between 18 and 21 min from HPLC purification of the mice brain extract were submitted to nano-electrospray ionization MS fragmentation. DDA (m/z 514) and deuterated d7-DDA (m/z 521) were fragmented simultaneously using the following parameters: parent ion mass, m/z 518; parent ion isolation width, m/z 8; and collision energy, 33%. MS3 analysis of the DDA and d7-DDA fragments at m/z 496 (Supplementary Fig. S2) and 503 (Supplementary Fig. S5) was performed using the following parameters: parent ion mass, m/z 500; parent ion isolation width, m/z 8; and collision energy, 45%. MS4 analysis of the DDA and d7-DDA fragments at m/z 478 and 485 was performed using the following parameters: parent ion mass, m/z 482; parent ion isolation width, 8 m/z; and collision energy, 50%. MS4 quantification of DDA was calculated from the m/z 424/431 ratio obtained by averaging 100 spectra. (c) (MS1) resulted in a molecular ion of [M+H]+ (m/z 514) obtained in MS1. (d) MS2 fragmentation of the [M+H]+ (m/z 514). (e) MS3 fragmentation of the (m/z 496) peak obtained in MS2. (f) MS4 fragmentation of the (m/z 478) peak obtained in MS3. (g) Michaelis–Menten plot of DDA formation. 2 μM of [14C]-5,6α-EC and His (0.5–200 μM) were incubated 10 min at 37 °C in the presence of mouse brain homogenate. Lipids were extracted and analysed by thin-layer chromatography, and DDA was quantified as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Experiments were repeated at least three times in duplicates. The data presented are the means±s.e.m. of all experiments. (h) Schemes describing the transformation of 5,6α-EC and 5,6β-EC in the presence of His and brain extracts.

Here we describe the isolation and characterization of DDA in mammalian tissues and report the identification of its target and its anti-tumour activities in immunocompetent mice. The discovery of DDA reveals the presence of an uncharacterized metabolic pathway at the crossroads between cholesterol and His metabolism. Importantly, we showed that this metabolism could be deregulated during carcinogenesis.

Results

Identification of endogenous DDA in mouse brain

We first investigated whether DDA was detectable in mouse brain, a tissue rich in AEBS28. Homogenates of whole brain with the cerebella were extracted using organic solvent, and the extracts were analysed by liquid chromatography and nano-electrospray mass spectrometry (MS). The mass fragmentation profiles of synthetic DDA (sDDA) (Supplementary Fig. S2a–d and Supplementary Table S1) and its synthetic regioisomer C17 (Supplementary Fig. S3a–d and Supplementary Table S1) were used as references. Mass spectrometric analysis of the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fractions eluted at 18–21 min (Fig. 1b) showed the presence of a peak of m/z=514, which corresponded to the expected mass of DDA (Fig. 1c). The MS/MS fragmentation of the m/z=514 peak (Fig. 1d–f) resulted in profiles that were similar to sDDA (Supplementary Fig. S2a–d) and distinct from synthetic regioisomer C17 by the absence of the m/z=367 fragment in MS (ref. 2) (Supplementary Fig. S3b and Supplementary Table S1). These experiments showed that DDA was endogenously present in mouse brain extracts.

We next tested whether DDA was synthesized through an enzymatic process. [14C]-5,6α-EC or [14C]-5,6β-EC were incubated with increasing concentrations of His and brain homogenate (Fig. 1g). We were able to measure the transformation of 5,6α-EC and His into DDA at 37 °C (apparent Km=5.16±0.8 μM and apparent Vm=0.12±0.04 pmol per mg protein per min for His) (Fig. 1g and Table 1). In contrast, no reaction occurred between 5,6α-EC and His in the absence of brain homogenate or when brain homogenate was boiled or treated with pronase (Table 1). Similarly, no reaction occurred when 5,6β-EC was incubated with His and brain homogenate at 37 °C (Table 1). These data established that DDA was generated through an enzymatic transformation of 5,6α-EC with His, whereas 5,6β-EC was unreactive in similar conditions (Table 1 and Fig. 1h).

Table 1. Determination of the enzymatic parameters for DDA formation.

| 5,6α-EC | 5,6β-EC | His | Treatment of brain extracts | Km(μM)a | Vmax(pmol per mg protein per min)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | 37 °C | 5.16±0.8 | 0.12±0.04 |

| + | − | + | No brain extract | No reaction | |

| + | − | + | Boiled | No reaction | |

| + | − | + | Pronase | No reaction | |

| − | + | + | 37 °C | No reaction |

DDA, dendrogenin A; EC, epoxy-cholesterol; His, histamine.

aMean±s.e.m. values (see Methods).

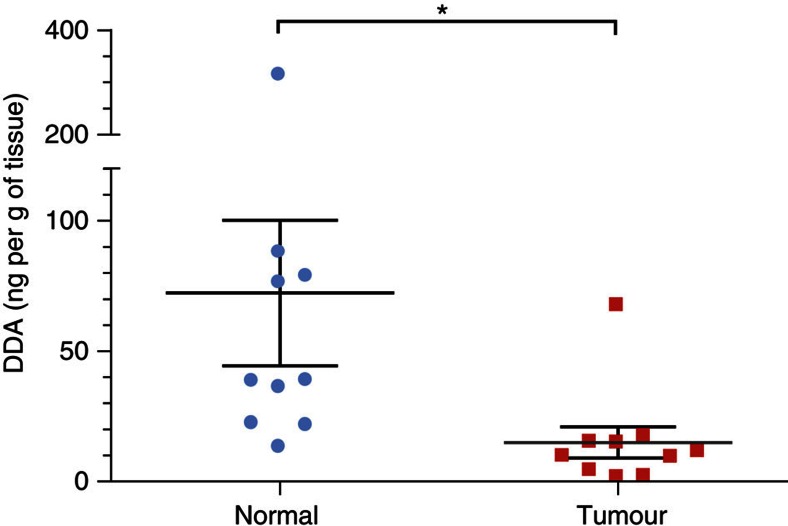

Quantification of DDA in mammalian tissues and tumours

Endogenous DDA was quantified through the establishment of a calibration curve (Supplementary Fig. S4) using deuterated DDA (d7-DDA) as an internal standard (Supplementary Fig. S5). DDA was present in mouse brain at a concentration of 46±7 ng per g of tissue (Table 2). Analysis of other tissues from mice and humans showed that DDA was present at concentrations ranging from 66±9 ng per g of tissue (human spleen) to 263±49 ng per g of tissue (mouse liver) (Table 2). The concentrations of DDA detected in human plasma and FBS were 2.8±1 and 6.2±1.3 nM, respectively (Table 2), indicating that DDA was also present in the circulation. Treatment of FBS with dextran-coated charcoal reduced the DDA content to below the limit of detection (Table 2). Because DDA was active against tumour cell lines at micromolar concentrations21, we quantified DDA in human and mouse cancer cells that were representative of several cancers. We used cell-culture conditions in which DDA was stripped from the serum with dextran-coated charcoal. In all the tumour cells analysed, DDA was below our limit of detection (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S2). In contrast, normal human mammary epithelial cells and normal human epidermal melanocytes produced DDA (Table 3). These data suggested a possible deregulation of DDA metabolism in tumour cells compared with normal cells. We subsequently quantified DDA in human breast tumours and in the adjacent normal tissue from patients. We determined that the mean amount of DDA was fivefold lower in human breast tumours (15±6 ng per g of tissue) compared with matched normal tissue (72±28 ng per g of tissue) (Fig. 2).

Table 2. Quantification of endogenous DDA in mammalian tissues and fluids.

|

DDA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue/fluids | ng per g tissuea | nMa | ng per mg proteina |

| Brain (M) | 46±7 | 87±14 | 1.06±0.17 |

| Liver (M) | 263±49 | 485±92 | 3.16±49 |

| Lung (M) | 36±7 | 65±13 | 0.54±0.11 |

| Spleen (M) | 112±1.7 | 207±31 | 1.51±0.22 |

| Spleen (H) | 66±9 | 126±16 | 0.76±0.10 |

| Fœtal serum (B) | 3.1±0.6 | 6.2±1.3 | 0.07±0.01 |

| Charcoal-treated serum | N.M. | N.M. | N.M. |

| Plasma (H) | 1.4±0.5 | 2.8±1.0 | 0.05±0.04 |

B, bovin; DDA, dendrogenin A; H, human; M, mouse; N.M., not measurable.

aMean±s.e.m. values (see Methods).

Table 3. Quantification of endogenous DDA in normal and tumor cells.

| Cell line | Cell type | DDA (ng per mg proteina) |

|---|---|---|

| HMEC | Normal mammary epithelial, human | 8.2±0.6 |

| MCF-7 | Breast carcinoma, human | N.M. |

| TS/A | Breast carcinoma, mouse | N.M. |

| SKBr3 | Breast carcinoma, human | N.M. |

| ZR75-1 | Breast carcinoma, human | N.M. |

| BT474 | Breast carcinoma, human | N.M. |

| HCC-1937 | Breast carcinoma, human | N.M. |

| MDA-MB-231 | Breast carcinoma, human | N.M. |

| HEM | Normal epithelial melanocyte, human | 5.6±0.4 |

| SK-MEL-28 | Melanoma, human | N.M. |

| B16F10 | Melanoma, mouse | N.M. |

| SK-MEL-2 | Melanoma, human | N.M. |

| A375 | Melanoma, human | N.M |

DDA, dendrogenin A; N.M., not measurable.

aMean±s.e.m. values (see Methods).

Figure 2. Quantification of endogenous DDA in human breast tumours and normal tissues.

Quantification of endogenous DDA from human breast tumours and adjacent normal tissues from 10 patients was carried out as described in Fig. 1 caption. Peaks m/z 496 (sDDA and C17) and 367 (C17) were used to determine the relative amounts of each molecule in samples before quantification. Each symbol represents the mean concentration of DDA determined in each normal or tumour sample that was analysed twice. The black lines indicate the group sample mean±s.e.m., *P<0.05 (Student’s t-test).

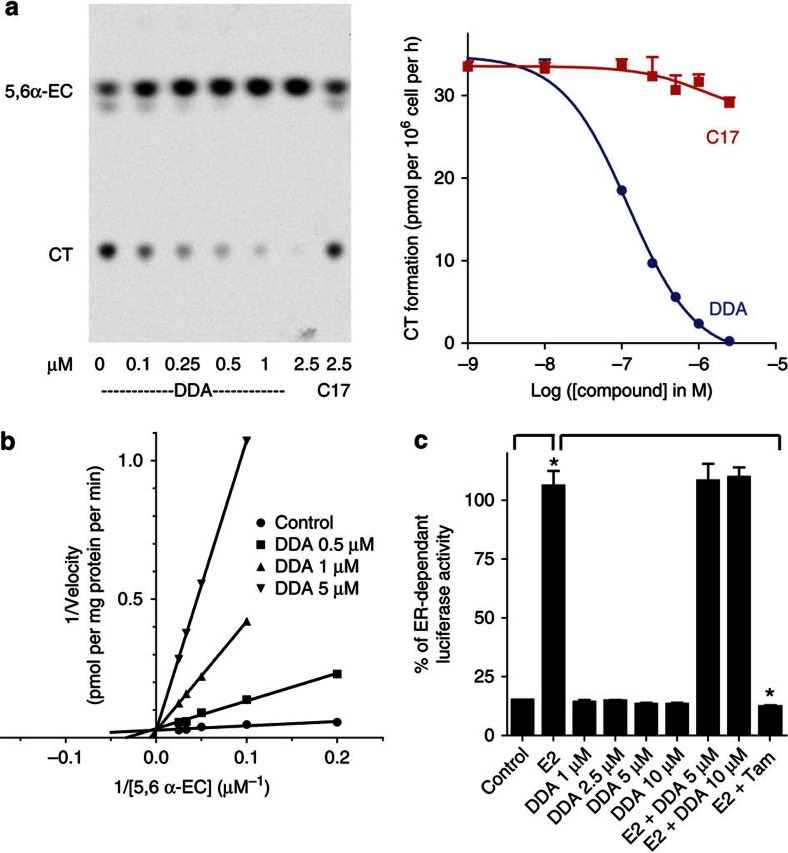

DDA is a selective inhibitor of ChEH

We previously reported that ligands of the AEBS were potent inhibitors of ChEH4, which is associated with their capacity to induce tumour cell differentiation and death5,9,10. We investigated whether DDA could be an inhibitor of ChEH activity because we had previously shown that ring B oxysterols inhibited ChEH4. As shown in the thin-layer chromatography autoradiogram in Fig. 3a, the conversion of 5,6α-EC into CT in human MCF-7 breast cancer cells was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by DDA with an IC50 of 120±20 nM, whereas C17 did not inhibit ChEH activity (Fig. 3a). Experiments on MCF-7 cell extracts4 showed that the inhibition of ChEH by DDA was competitive because Km increased and Vmax remained unchanged (Fig. 3b). The potency of DDA to inhibit ChEH in whole cells was compared with the natural ring B oxysterols, 7α-hydroxycholesterol (7α-OHCh) and 7-ketocholesterol, that inhibited ChEH in microsomes from rat liver4. 25-OHCh that did not inhibit ChEH was used as control4. 7α-OHCh and 7-ketocholesterol inhibited ChEH in MCF-7 cells with IC50 values that were 100-fold (12±2.9 μM) and 42-fold (5.09±1.4 μM) higher than DDA, respectively, whereas 25-OHCh was unable to inhibit ChEH in these conditions. We then determined the ability of DDA to inhibit ChEH in other cancer cell lines that responded to DDA21. DDA inhibited ChEH activity with a high potency in all the cell lines tested, with an IC50 of 284±70 nM in murine mammary TSA cells, an IC50 of 72±15 nM in human melanoma SK-Mel-28 cells and an IC50 of 252±81 nM in murine melanoma B16F10 cells. In contrast, C17 was inactive against ChEH in all these cell lines. These data show that DDA is a direct inhibitor of ChEH and the most potent natural inhibitor of this enzyme to date. To determine if DDA was selective for ChEH compared with other epoxide hydrolases, DDA was tested on soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) and microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH) activities. DDA did not inhibit these enzymes, thus establishing its selectivity for ChEH (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 3. DDA is the most potent natural inhibitor of ChEH.

MCF-7 cells were incubated with 0.6 μmol l−1 [14C]-5,6α-EC at 37 °C for 8 h with or without the indicated concentrations of DDA or C17. ChEH activity was assayed by measuring the conversion of [14C]-5,6α-EC to [14C]-CT by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and quantified by densitometric analysis. (a) On the left panel, a representative autoradiogram of a TLC run from three independent experiments; on the right panel, the dose–response curves of the inhibition of [14C]-CT formation measured by TLC with DDA (circle) or C17 (square) at the indicated concentrations. The curves represent the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments and were used to calculate the IC50. (b) Modality of ChEH inhibition by DDA. The relationship between the conversion rates of 5,6α-EC to CT and DDA concentrations is shown using 0.5, 1 and 5 μM DDA with MCF-7 cell extracts. A double reciprocal plot of velocity versus [14C]-5,6α-EC at the given DDA concentrations is presented. Experiments were repeated at least three times in duplicates. The data presented are the mean±s.e.m. of all experiments. (c) Measurement of ER-dependent transcriptional activity in MELN cells. Cells were incubated with the solvent vehicle (control), 10 nM E2 or increasing concentrations of DDA with or without 10 nM 17β-estradiol (E2) or 1 μM Tam with 10 nM E2. Experiments were repeated at least three times in duplicates. The data presented are the means±s.e.m. of all experiments. P<0.001 compared with control cells.

DDA is not a modulator of the ER

Several AEBS ligands and oxysterols have been shown to modulate ER-dependent transcription29,30,31. We therefore examined whether DDA could function as an ER modulator using MELN cells, which are MCF-7 cells stably transfected with a plasmid that encodes an oestrogen-responsive promoter fused to the luciferase gene32. As shown in Fig. 3c, DDA did not stimulate the expression of luciferase in these cells and did not inhibit luciferase stimulation by 17β-estradiol (E2), whereas Tam, used as a positive control, completely inhibited luciferase expression. Therefore, DDA is not a modulator of the ER transcriptional activity, and its pharmacology is distinct from that of Tam.

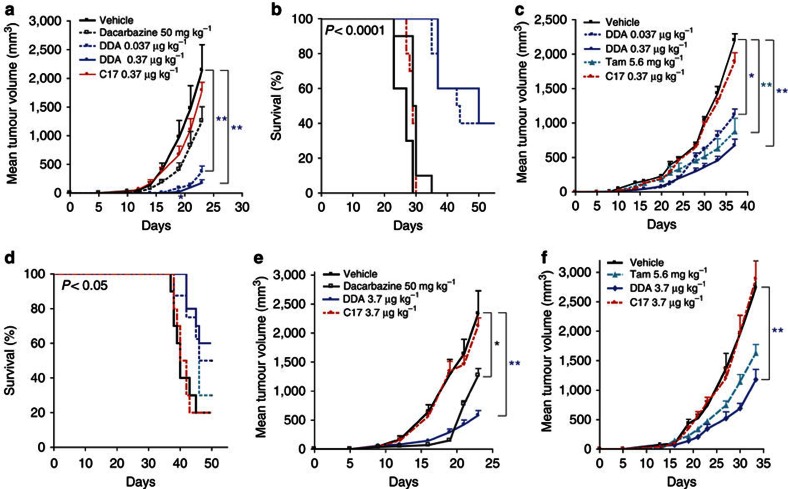

DDA exerts anti-tumour properties in vivo

We previously established that DDA induced tumour cell differentiation and death in vitro in various tumour cell lines of different types of cancers, and in particular, DDA induced lactation characteristics in breast cancer cell lines and melanogenesis in melanoma cell lines21. Because DDA is endogenous in mammals, we assessed its anti-tumour activity against syngeneic tumours grafted onto a natural environment using immunocompetent mice. In a chemotherapeutic setting, mice were grafted subcutaneously (s.c.) with a melanoma (B16F10) or a mammary (TS/A) tumour and treated on the same day and subsequently with DDA, or the indicated compounds or vehicle (control group). In B16F10-grafted mice, DDA at a concentration of 0.37 μg kg−1 significantly inhibited tumour growth compared with the control (Fig. 4a), and prolonged animal survival: 40% survivors at day 50 compared with none in the control group (Fig. 4b). In TS/A-grafted mice, DDA treatment (0.37 μg kg−1) significantly reduced tumour growth (Fig. 4c) and prolonged animal survival up to 60% at day 50 (Fig. 4d) in comparison with the control group, whereas C17 did not significantly reduce tumour growth (Fig. 4c) or improve animal survival (Fig. 4d). A significant reduction in tumour volume was also observed with 5.6 mg kg−1 of Tam compared with the control group (Fig. 4c), however, Tam did not significantly improve animal survival compared with control animals (Fig. 4d). We then investigated the efficacy of DDA against established B16F10 and TS/A tumours (Fig. 4e, respectively). In this setting, immunocompetent mice were treated s.c. once a day with DDA or the indicated compounds or the vehicle (control group). As shown in Fig. 4e, 3.7 μg kg−1 of DDA treatment resulted in a significant decrease in B16F10 tumour growth compared with the control group, whereas a similar dose of C17 had no anti-tumour effect. A significant reduction in tumour volume was also obtained with 50 mg kg−1 of dacarbazine. As shown in Fig. 4f, treatment of TS/A-grafted mice with 3.7 μg kg−1 of DDA resulted in a significant reduction in tumour growth, whereas C17 and Tam did not significantly inhibit tumour growth compared with the control group.

Figure 4. DDA inhibited the growth of B16F10 melanoma and TS/A mammary tumours implanted into immunocompetent mice and enhanced animal survival.

Immunocompetent mice were implanted s.c. with (a) B16F10 cells or (b,c) TS/A cells and animals (n=10 mice per group) were treated every 5 days starting on the day of tumour implantation with the indicated doses of either dacarbazine (intraperitoneally (i.p.)), DDA (s.c.), C17 (s.c.), vehicle (s.c.) or Tam (i.p.). Animals were monitored for tumour growth (a,c), *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (analysis of variance (ANOVA), Dunnett’s post test), and survival (b,d), *P<0.05; ***P<0.0001 (log-rank tests). Immunocompetent mice were implanted s.c. with (e) B16F10 cells or (f) TS/A cells, and when the tumour reached a volume of 50–100 mm3, animals (n=10 mice per group) were treated once per day with the indicated doses of dacarbazine (i.p.), DDA (s.c.), C17 (s.c.), vehicle (s.c.) or Tam (i.p.) and were monitored over time for tumour growth, *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (ANOVA, Dunnett’s post tests). The mean tumour volume±s.e.m is shown. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

DDA induces tumour cell differentiation and immune cell infiltration

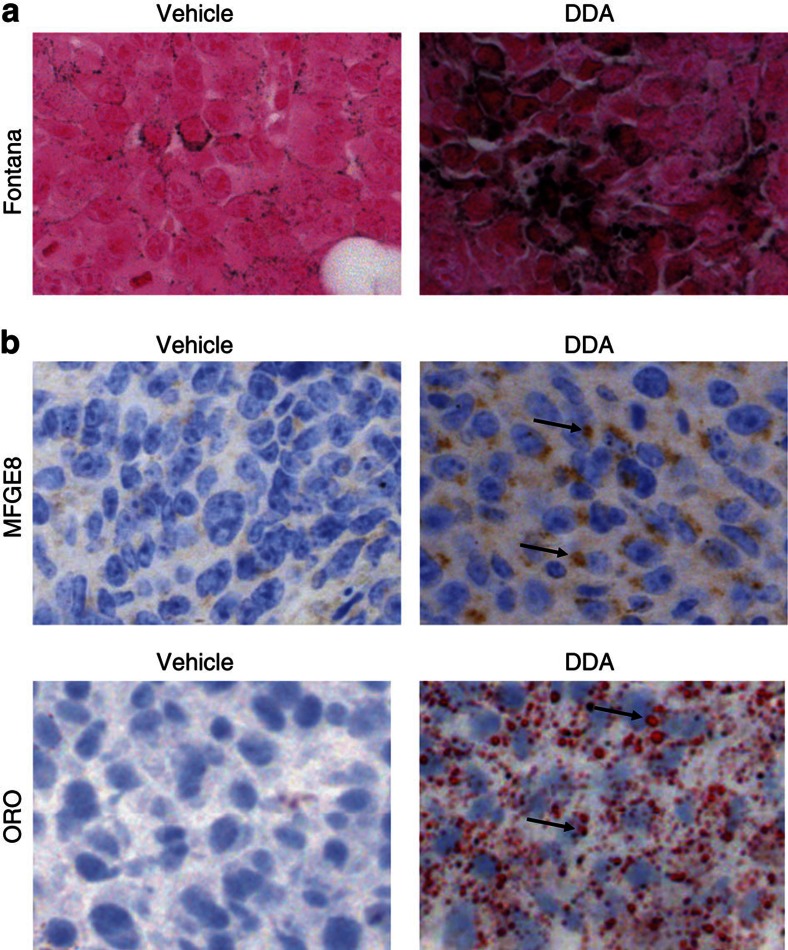

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses of tumours isolated from control and DDA-treated animals showed that the inhibition of tumour growth by DDA was associated with increased tumour differentiation in both tumour models. Masson–Fontana’s staining of B16F10 tumour sections showed there was an increased production of melanin (Fig. 5a), and TS/A tumour sections had an increased expression of milk fat globule (MFGE8)/lactadherin as assessed by immunohistochemistry and an increased accumulation of neutral lipid droplets stained with Oil Red O (ORO) (Fig. 5b). Similarly, cell differentiation was also observed after in vitro treatment of B16F10 and TS/A cells with DDA. In B16F10 cells treated with DDA for 24 h, the melanin content increased in a concentration-dependent manner up to 2.5 μM DDA (Supplementary Fig. S6a,b) and was associated with increased activity of tyrosinase, which is the enzyme that catalyses the initial and rate-limiting step of melanin production (Supplementary Fig. S6c). Moreover, TS/A cells treated for 24 h with 1 and 2.5 μM DDA showed a 2.4- and 3-fold increase in staining of neutral lipid droplets with ORO (Supplementary Fig. S7a,b) and a 7- and 9-fold increase in intracellular triglycerides (Supplementary Fig. S7c), respectively, compared with solvent vehicle-treated cells. In addition, MFGE8/lactadherin was increased after treatment with 2.5 μM DDA, as determined by immunostaining and flow-cytometry analysis (Supplementary Fig. S7d, left and right panels, respectively). Therefore, DDA treatment induces similar biological responses in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, we observed that DDA-mediated tumour differentiation was accompanied by an increased infiltration of CD3+ T lymphocytes and CD11c+ dendritic cells into B16F10 (Supplementary Fig. S8a) and TS/A (Supplementary Fig. S8b) tumours compared with the control groups, which indicated an enhanced recognition of the tumours by the immune system after DDA treatment.

Figure 5. DDA treatment induced in vivo differentiation of B16F10 and TS/A tumours implanted into immunocompetent mice.

Histology of tumours resected from immunocompetent mice treated with vehicle (left panels) or DDA (3.7 μg kg−1) (right panels) and stained for specific markers of cell differentiation. Paraffin sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for histomorphological analyses. (a) B16F10 tumour sections from mice treated for 23 days were analysed for melanin production with Masson–Fontana staining (black labelling). (b) TS/A tumour sections from mice treated for 30 days were analysed for MFGE8 expression with a specific antibody (brown staining, indicated by arrows) and for neutral lipid production by ORO staining (red labelling, indicated by arrows). For lipid staining, frozen sections were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and then stained with ORO and counterstained with haematoxylin. Immunohistochemical staining was done on paraffin-embedded tissue sections, using a specific hamster monoclonal to MFGE8 antibody (4 μg ml−1). Immunostaining of paraffin sections was preceded by an antigen retrieval technique by heating in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6, with a microwave oven twice for 10 min each. After incubation with the antibody for 1 h at room temperature, sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated polyclonal anti-hamster immunoglobulin antibody followed by the streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, CA) and were then counterstained with haematoxylin. Negative controls were incubated in buffered solution without primary antibody. Magnification is × 200.

Discussion

We describe here the isolation and structural characterization of DDA as the first endogenous steroidal alkaloid identified in mammals. Using nano-electrospray MS after HPLC enrichment, we were able to measure DDA in various tissues. DDA was present at various concentrations, ranging from 46 to 263 ng per g of tissue in brain, lung, liver, spleen and breast tissues (between 65 and 485 nM). In comparison, the concentration of 5,6α-EC in mouse liver was reported to be 170 ng per g of tissue33, which indicates that DDA is present in the same concentration range as 5,6α-EC in the liver. In plasma and serum, the concentration of DDA was between 2.8±1.0 and 6.2±1.3 nM. Numerous steroidal alkaloids have been isolated from plants (tomatidine in Solanum lycopersicum), amphibians (batrachotoxins in members of the genus Phyllobates and Dendrobates)23 and fish (squalamine in S. acanthias and petromyzonamine in P. marinus)34,35. The structure of DDA is distinct from these steroidal alkaloids. DDA is a derivative of cholesterol, and the nitrogen source is from His, which is derived from the amino acid histidine. DDA is the first steroidal alkaloid reported to date in which the basic group is attached to ring B of the steroid backbone. We showed through pulse-chase metabolic studies that DDA is enzymatically formed in mammalian tissue extracts. It has to be noted that the reaction occurred only with 5,6α-EC, showing a stereoselectivity in 5,6-EC conjugation. Interestingly, this reaction showed the same selectivity as that we determined for 5,6-EC in chemical medium under catalytic conditions15 (Supplementary Fig. S1). This shows that the presence of the Δ5 double bond enables a stereospecific transformation to take place that leads to the biosynthesis of only one stereoisomer. This Δ5 double bond has been shown to contribute to the specific physicochemical properties of cholesterol that drive its membrane interactions36, to be required for the downregulation of hydroxymethyl glutaryl coenzyme A37 and for cell viability38. In addition, the accumulation of dihydrocholesterol (cholestanol), which lacks the Δ5 double bond, is linked to severe genetic diseases, such as lathosterolosis associated with perinatal death8 and cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis39; both syndromes lead to severe impairment in development. This supports our observation that an active metabolism of the Δ5 double bond can generate products such as DDA with potent cell differentiation properties and that these products may be required for development. Because we reported that other products of aminolysis from 5,6α-EC can be produced and had different biological properties according to the nature of the biogenic amine that has been grafted21, it will be important to determine whether other steroidal alkaloids exist in mammals as well.

Pharmacological assays indicate that DDA is the most potent natural and selective inhibitor of ChEH found to date, with an IC50 between 72 and 284 nM depending on the cell lines tested. This suggests that physiological tissue concentrations of DDA (between 65±13 and 485±92 nM) may control the activity of ChEH and the accumulation of 5,6-ECs. We recently reported that the inhibition of ChEH that leads to 5,6-ECs accumulation is likely to have a role in the chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of drugs that are of high clinical interest, such as Tam4,7,9. ChEH inhibition could represent a possible mechanism involved in the anti-cancer and animal survival action of DDA. Interestingly, the anti-tumour effects of DDA have been associated with an increased tumour infiltration of T lymphocytes and CD11c+ dendritic cells. Oxysterol metabolism has been linked to innate and adaptive immune responses through LXR signalling40,41, and 5,6α-EC was reported to be a direct modulator of LXR17. In addition, 5,6α-EC is the substrate of cholesterol sulphotransferase SULT2B1b42,43, and the resulting 5,6α-EC-3-sulphate is a modulator of LXR9,11,18. A recent study showed that human and mouse tumours produce LXR agonists that inhibit CC chemokine receptor-7 expression on maturing DCs and the ability of DCs to initiate an immune T-cell response against tumours. Engineering the expression of SULT2B1b in these tumours reversed this process through inactivation of LXR agonists and resulted in tumour growth control, increased animal survival and inhibition of tumour immunoescape40. This work shed light on the importance of regulating LXR to mediate an anti-tumour response, immunity and animal survival. This could be achieved with DDA through the direct inhibition of ChEH, which generates LXR modulators9,11,18. Interestingly, we showed that DDA does not modulate the transcriptional activity of the ER compared with Tam. This excludes the risk of endometrial cancer that is increased with Tam treatment through an ER stimulation-dependent mechanism12. Moreover, most immune cells, including myeloid progenitors and dendritic cells, express the ER, and oestrogen is recognized as a growth and/or differentiation factor for these cells44. By antagonizing the ER, Tam may depress immunity by impairing oestrogen-promoted dendritic differentiation and activation45, whereas DDA acts independently of the ER. We showed that DDA was not an inhibitor of mEH, another known target of Tam46, and of sEH, meaning that DDA is selective for ChEH over other known epoxide hydrolases.

Overall, these data suggest that DDA is an endogenous factor that may help to maintain cell integrity and differentiation. Consistent with these properties, DDA was measurable in normal cells but was undetectable in cancer cells of diverse origin. In addition, its level in human breast tumour samples was determined to be fivefold lower than in the adjacent normal tissue, suggesting that deregulation of DDA biosynthesis may occur during carcinogenesis.

We recently reported that 5,6α-EC is unreactive towards nucleophiles and extremely stable11,15,21, and its reaction with His was only possible under strong catalytic conditions to give sDDA21. Here we show that incubation of 5,6α-EC with His and brain homogenate at 37 °C is sufficient to produce DDA. In contrast, boiling or submitting brain homogenate to proteolysis completely abolished the formation of DDA. Together, these data indicate that the biosynthesis of DDA is catalysed by an enzyme that has yet to be identified. Its identification will be a major focus of our future efforts.

Several lines of evidence indicate that cholesterol metabolism is involved in cancer development, aggressiveness and resistance to treatment47. In particular, it was reported that cholesterol metabolites such as cholesteryl fatty acid esters48, cholestane-3β,5α,6β-triol metabolites7, biliary acids49, high and low density lipoproteins50 and sex steroids such as estrogens and androgens can behave as tumour promoters51. The decreased level of DDA in tumours compared with adjacent tissues suggests that a default in DDA metabolism may contribute to tumour development, whereas DDA complementation induces tumour cell differentiation and an anti-tumour response. Thus, DDA appears as the first sterol metabolite with tumour-suppressor properties.

In conclusion, our results shed light on the existence of the first steroidal alkaloid described in higher vertebrates, including humans, with potentially important physiological functions in maintaining cell integrity, differentiation and possibly immune system surveillance. The anti-tumour effects of DDA, and its impact on animal survival, indicate that DDA may have clinical applications in the therapy and the chemoprevention of cancers.

Importantly, the discovery of DDA reveals the existence of a steroidal alkaloid metabolism in mammals at the crossroads of cholesterol and His metabolism, and opens new avenues of research.

Methods

Materials

Chemicals and solvents were from Sigma unless otherwise specified. [14C] cholesterol (58 Ci mol−1) was from GE Healthcare. [25,26,26,26,27,27,27-d7] cholesterol (99% D) was from Sigma-Aldrich. HPLC-MS grade acetonitrile was from Pierce. HPLC purifications were done on a Gilson HPLC or on a LC200 Perkin Elmer apparatus, equipped with a diode array UV or a beta radioactivity detector, using an Ultrasep C18 RP 100 column (Bischoff, Ge). Autoradiography experiments were done with GE Healthcare or Kodak phosphor screens, and images were generated with a STORM 840 Imager (Amersham Biosciences). A FACScalibur, Becton-Dickinson, was used for cytometry flux analyses. sDDA (5α-Hydroxy-6β-[2-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)-ethylamino]-cholestan-3β-ol) and C17 (5α-hydroxy-6β-[5-(2-amino-ethyl)-imidazol-1-yl]-cholestan-3β-ol) were prepared as previously described21 and were 99% pure. Dacarbazine was from the Institute Claudius Regaud (France). 1-Trifluoromethoxyphenyl-3-(1-propionylpiperidin-4-yl)-urea, N-acetyl-S-farnesyl-L-cystein and 2-nonylsulfanylpropionamide were prepared according to previously published procedures52,53. The antibodies used were from the following companies: the anti-MFGE8 used for in vitro studies was from Clinisciences (France) (clone 2422); the anti-MFGE8 used for immunohistology was from MBL International, MA (clone 18A2-G18); the anti-CD3 (ready to use) was from Dako (France); and anti-CD11c (clone N418) was from Tebu-bio (France).

Animals

Female C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (France). All mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions and were included in protocols only following 2 weeks quarantine. All of the animal procedures for the care and use of laboratory animals were conducted according to the ethical guidelines of our institution and followed the general regulations governing animal experimentation.

Cell culture

TS/A cells were provided by Dr P.L. Lollini (Bologna, Italy)54. GL261 brain carcinoma cells were provided by Dr G Safrany (Budapest, Hungary)55. Normal human mammary epithelial cells were from Invitrogen (CA, USA) and were grown in the HuMEC ready medium. Normal human epidermal melanocytes were from the ECACC (Salisbury, UK) and were grown in the melanocyte growth medium provided by the ECACC. Other cells lines were from the American Tissue Culture Collection. All cell lines were grown in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. All culture media contained penicillin and streptomycin (50 U ml−1 each) and 1.2 mM glutamine (3.2 mM glutamine for B16F10). MELN32 and MCF-7 cells were grown in RPMI supplemented with 5% FBS. TS/A, A549, SK-N-SH, SH-SY5Y, SW620, HCT-8, HT29, SK-Mel-2, SK-Mel-28, U937 and NB4 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (FBS was heat-inactivated for SK-Mel-28 cells). SKBr3, MDA-MB-231, HCC-1937, ZR75-1, BT474, A375, B16F10, GL261, Neuro2A and U87 were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. KG1 were grown in IMDM supplemented with 20% FBS. FBS was replaced by steroid-free FBS 1 month before quantification of endogenous DDA.

Preparation of tissues and cell extracts

All human samples were collected with the approval of institutional review board of the Purpan University Hospital and of the Institut Claudius Regaud. Human plasma was recovered from buffy-coat preparations from blood samples obtained at the Etablissement Français du Sang (Toulouse, France) from healthy donors. Organs from Balb/c mice (8 weeks old) were resected and kept at 4 °C to be prepared immediately. Normal and tumour human tissues obtained by surgical resection were stored frozen at −80 °C and thawed in ice before use. Patients’ clinical characteristics and tumour pathological features were obtained from the medical reports and followed the standard procedures in our institution. In the selected tumour or normal tissue samples, the percentage of tumour cells or normal epithelial cells was >50%. Tissues were homogenized at 4 °C in buffer A (50 mM Tris, 0.5% butylated hydroxytoluene (5 mg ml−1), 150 mM KCl, pH 7.4) (5 vol g−1 of tissue) with a Polytron B homogenizer and centrifuged 5 min at 2,500 r.p.m. Homogenates and sera were diluted with buffer A to obtain samples at 10 mg protein per ml. To obtain cell extracts, cells were grown as described above and were washed with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS. Three independent batches of 107 cells were prepared for each cell line. After harvesting, cells were homogenized in buffer A (vol/vol) to obtain samples at 5 mg protein per ml.

Chemical synthesis

[25,26,26,26,27,27,27-d7]-5α-Hydroxy-6β-[2-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)-ethylamino]-cholestan-3β-ol (d7-DDA): d7-DDA was synthesized according to the previously published procedure using [25,26,26,26,27,27,27-d7]-cholesterol instead of cholesterol21. The crude product was purified by column chromatography using triethylamine-deactivated silica and eluted with 0–10% methanol in an EtOAc gradient to give the expected product as a light yellow powder (3.5 mg, 35%). d7-DDA was further purified by HPLC using an acetonitrile gradient (40% B for 8 min, then to 100% B in 20 min; A was 95:5 water/acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA; B was 95:5 acetonitrile/water, 0.1% TFA) with a retention time of 18.5 min, a mass with the expected molecular ion (m/z 521.5 [M+H]+) and a purity >98%.

[4-14C]-5α-Hydroxy-6β-[2-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)-ethylamino]-cholestan-3β-ol ([14C]-DDA): [14C]-5,6α-EC (58 Ci mol−1; 30 μCi; 0.52 μmol) and His (3 eq) in nBuOH (10 μl) were refluxed for 3 days. The mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and resuspended in 40 μl of ethanol and then purified by HPLC to give [14C]-DDA (7.0 μCi; 23%) with a purity >98%.

Extraction, HPLC purification and MS analysis

Tissues and cell homogenates were extracted as described previously6, and 0.1 μCi [14C]-DDAs were added in separate experiments for determination of the yield of DDA extraction. The samples were dried under Argon, dissolved in 200 μl MeOH and passed through a C18 Sep-Pak cartridge (Waters). HPLC purification was carried out as described for sDDA. The 18–21 min fractions were dried in vacuo and stored at −80 °C under argon until use. The percentage recovery of [14C]-DDA was 91±6%. d7-DDA standard was added at a final concentration of 1 μg ml−1. MS was performed using an LCQ ion-trap mass spectrometer (Finnigan MAT, San Jose, CA) as previously described 56. Samples were analysed in the positive ion mode.

DDA neosynthesis assay

The evaluation of DDA biosynthesis was done with mouse brain tissue extracts as described above using [14C]-5,6α-EC and [14C]-5,6β-EC. Homogenates (280 μg of protein per sample) were suspended in 140 μl buffer A and 10 μl acetonitrile (6.7%) containing His (from 0.5 to 200 μM) and 2 μM [14C]-5,6α-EC or [14C]-5,6β-EC and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. In some conditions, mouse brain homogenate was absent or boiled or pronase-treated before incubation with 2 μM [14C]-5,6α-EC and 100 μM His. The reaction was stopped by immersing the samples in ice-water, 0.5 ml of H2O was added and lipids were extracted using 1.5 ml chloroform/methanol (2:1).

ChEH, sEH and mEH activity assays

ChEH, N-terminal-epoxide hydrolase of sEH and mEH activities were carried out as described in de Medina et al.4, Rose et al.52 and Morisseau et al.53, respectively.

Cell assays

Cells were plated on sterile coverslips in complete medium at 50% confluency and the next day treated for 24 h at 37 °C with the vehicle or DDA. Cells were then fixed with a methanol/acetone solution (1:1) for 15 s and nuclei stained with propidium iodide. Immunostaining of MFGE8 was done exactly as described5. The slides were then washed with PBS and mounted with Moviol 4-88 reagent (Calbiochem). Cells were observed using confocal fluorescence microscopy (Leica DMRE). Images were prepared using a Zeiss LSM Image Viewer. For flow-cytometry studies, cells (250,000) were seeded onto 100-mm plates and the next day treated for 24 h with vehicle or DDA at the indicated concentrations. Cells were then washed, fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.05% saponin in PBS containing 1% BSA for 10 min. Cells were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with primary antibodies against MFGE8 (1:500) or control isotypes (1:100) and then with secondary antibodies (1:500). Cells were then washed and analysed using flow cytometry. ORO staining5, lipid5 and melanin57 quantification, tyrosinase activity58 and luciferase assays59 were done exactly according to published procedures.

Analysis of tumours

Exponentially growing B16F10 and TS/A cells were collected, washed twice in PBS and resuspended in PBS (35,000 cells in 150 μl PBS). B16F10 and TS/A tumours were prepared by subcutaneous transplantation into the flanks of C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice, respectively. Animals were examined daily, and body weights were measured twice per week. In all the experiments, the tumour volume was determined by direct measurement with a caliper and was calculated using the formula (width2 × length)/2. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to compare the mice survival. Tumours were resected at the indicated time and either frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Tumour growth curves in animals were analysed for significance by analysis of variance with Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests. Animal survival curves were analysed by log-rank test. In other experiments, significant differences in the quantitative data between the control and the treated group were analysed using the Student’s t-test for unpaired variables. In the figures, *, ** and *** refer to P<0.05, P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively, compared with controls (vehicle) unless otherwise specified. Prism software was used for all the analyses.

Author contributions

M.P. and S.S.-P. developed the concept, designed the study, wrote the paper, and contributed equally to the work. P.D.M. and M.R.P. did the synthesis and the structural characterization of compounds. P.D.M. performed and analysed the measurement of ChEH and the modulation of ER activity. M.R.P., M.V. and F.P. did the purification of DDA and conducted the MS experiments. M.P. did the fragmentation analysis on MS. P.D.M., M.R.P., G.S., L.M. and S.S.-P. did the cell cultures, the in vitro characterizations of DDA effects and analysed data. L.M. and S.S.-P. conducted the in vivo experiments. S.S.-P. Analysed the data. F.D. participated in collecting and analysing the patient samples. M.L.T. participated in performing and interpreting experiments on patient samples and in writing the corresponding text in the manuscript. T.A.S. performed the IHC. T.A.S and S.S.-P. analysed the data. C.M and B.D.H. performed the experiments on mEH and sEH and analysed the data. T.F. did the statistical analysis. All the authors participated in writing the ‘Methods’ section of their corresponding work contribution.

Additional information

How to cite this article: de Medina, P. et al. Dendrogenin A arises from cholesterol and histamine metabolism and shows cell differentiation and anti-tumour properties. Nat. Commun. 4:1840 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2835 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Tables S1-S3

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the ‘Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale’, the ‘Université de Toulouse III’, the ‘Institut Claudius Regaud’, the ‘Ministère Français de la Recherche’ through a 3-year doctoral fellowship (G.S.), the ‘Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer’ though a 1-year doctoral fellowship (G.S.), Partial funding came from the ‘Fondation de France’ grant 20349, the ‘National Institute on Environment Health Sciences’ Grant PA2 ES011269 and R01 ES002710CM. B.D.H. is a George and Judy Marcus Senior Fellow of the American Asthma Foundation. We thank the staff of the tumour bank of Claudius Regaud Institute (Dr P. Rochaix and L. Puydenus) for their technical support and helpful discussions, and F. Capilla for IHC technical support.

Footnotes

P.D.M., M.R.P. and L.M. are employees of the company Affichem of which S.S.-P. and M.P. are founders. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Newman J. W., Morisseau C., Hammock B. D. Epoxide hydrolases: their roles and interactions with lipid metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res. 44, 1–51 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirot M., Silvente-Poirot S., Weichselbaum R. R. Cholesterol metabolism and resistance to tamoxifen. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 12, 683–689 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P. et al. Importance of cholesterol and oxysterols metabolism in the pharmacology of tamoxifen and other AEBS ligands. Chem. Phys. Lipids 164, 432–437 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P., Paillasse M. R., Segala G., Poirot M., Silvente-Poirot S. Identification and pharmacological characterization of cholesterol-5,6-epoxide hydrolase as a target for tamoxifen and AEBS ligands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13520–13525 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payre B. et al. Microsomal antiestrogen-binding site ligands induce growth control and differentiation of human breast cancer cells through the modulation of cholesterol metabolism. Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 3707–3718 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedjouar B. et al. Molecular characterization of the microsomal tamoxifen binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34048–34061 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvente-Poirot S., Poirot M. Cholesterol epoxide hydrolase and cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 12, 696–703 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter F. D., Herman G. E. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 52, 6–34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segala G. et al. 5,6-Epoxy-cholesterols contribute to the anticancer pharmacology of tamoxifen in breast cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol (e-pub ahead of print 7 March 2013; doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.02.031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P. et al. Ligands of the antiestrogen-binding site induce active cell death and autophagy in human breast cancer cells through the modulation of cholesterol metabolism. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1372–1384 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirot M., Silvente-Poirot S. Cholesterol-5,6-epoxides: chemistry, biochemistry, metabolic fate and cancer. Biochimie 95, 622–631 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan V. C. Chemoprevention of breast cancer with selective oestrogen-receptor modulators. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 46–53 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F. P. Cytochrome P450 oxidations in the generation of reactive electrophiles: epoxidation and related reactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 409, 59–71 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. E., Isaacs N. S. Mechanisms of epoxide reactions. Chem. Rev. 59, 737–799 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- Paillasse M. R. et al. Surprising unreactivity of cholesterol-5, 6-epoxides towards nucleophiles. J. Lipid Res. 53, 718–725 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe T., Sawahata T. Biotransformation of cholesterol to cholestane-3beta,5alpha,6beta-triol via cholesterol alpha-epoxide (5alpha,6alpha-epoxycholestan-3beta-ol) in bovine adrenal cortex. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 3854–3860 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrodin T. J. et al. Identification of 5{alpha},6{alpha}-epoxycholesterol as a novel modulator of liver x receptor activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 1046–1058 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Hiipakka R. A., Liao S. Auto-oxidized cholesterol sulfates are antagonistic ligands of liver X receptors: implications for the development and treatment of atherosclerosis. Steroids 66, 473–479 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D. J., Ketterer B. 5 alpha,6 alpha-Epoxy-cholestan-3 beta-ol (cholesterol alpha-oxide): A specific substrate for rat liver glutathione transferase B. FEBS Lett. 150, 499–502 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe T., Sawahata T., Horie J. Evidence for the formation of a steroid S-glutathione conjugate from an epoxysteroid precursor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 87, 469–475 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P., Paillasse M. R., Payre B., Silvente-Poirot S., Poirot M. Synthesis of new alkylaminooxysterols with potent cell differentiating activities: identification of leads for the treatment of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. J. Med. Chem. 52, 7765–7777 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes L. J., Bogdanovic R. P., Cawker M. D., LaBella F. S. Histamine and growth: interaction of antiestrogen binding site ligands with a novel histamine site that may be associated with calcium channels. Cancer Res. 47, 4025–4031 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewick P. M. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: New York, (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Herbst R. S. et al. A phase I/IIA trial of continuous five-day infusion of squalamine lactate (MSI-1256F) plus carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 4108–4115 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Williams J. I., Pietras R. J. Squalamine and cisplatin block angiogenesis and growth of human ovarian cancer cells with or without HER-2 gene overexpression. Oncogene 21, 2805–2814 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. I. et al. Squalamine treatment of human tumors in nu/nu mice enhances platinum-based chemotherapies. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 724–733 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sills A. K. Jr. et al. Squalamine inhibits angiogenesis and solid tumor growth in vivo and perturbs embryonic vasculature. Cancer Res. 58, 2784–2792 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. M., Ziemian L. Antiestrogen binding sites in brain and pituitary of ovariectomized rats. Brain Res. 578, 55–60 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umetani M. et al. 27-Hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous SERM that inhibits the cardiovascular effects of estrogen. Nat. Med. 13, 1185–1192 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H. et al. Oxysterol regulation of estrogen receptor alpha-mediated gene expression in a transcriptional activation assay system using HeLa cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68, 1790–1793 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P., Favre G., Poirot M. Multiple targeting by the antitumor drug tamoxifen: a structure-activity study. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents 4, 491–508 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P. et al. The prototypical inhibitor of cholesterol esterification, Sah 58-035 [3-[decyldimethylsilyl]-n-[2-(4-methylphenyl)-1-phenylethyl]propanamide], is an agonist of estrogen receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319, 139–149 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroepfer G. J. Jr. Oxysterols: modulators of cholesterol metabolism and other processes. Physiol. Rev. 80, 361–554 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen P. W. et al. Mixture of new sulfated steroids functions as a migratory pheromone in the sea lamprey. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 324–328 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. S. et al. Squalamine: an aminosterol antibiotic from the shark. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 1354–1358 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie M. E., Veatch S. L., Stottrup B. L., Keller S. L. Sterol structure determines miscibility versus melting transitions in lipid vesicles. Biophys. J. 89, 1760–1768 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E., Bjoerkhem I. Down-regulation of hepatic HMG-CoA reductase in mice by dietary cholesterol: Importance of the DELTA.5 double bond and evidence that oxidation at C-3, C-5, C-6, or C-7 is not involved. Biochemistry 33, 291–297 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F. et al. Dual roles for cholesterol in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14551–14556 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkhem I., Hansson M. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: An inborn error in bile acid synthesis with defined mutations but still a challenge. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 396, 46–49 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villablanca E. J. et al. Tumor-mediated liver X receptor-alpha activation inhibits CC chemokine receptor-7 expression on dendritic cells and dampens antitumor responses. Nat. Med. 16, 98–105 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensinger S. J. et al. LXR signaling couples sterol metabolism to proliferation in the acquired immune response. Cell 134, 97–111 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuda H., Javitt N. B., Mitamura K., Ikegawa S., Strott C. A. Oxysterols are substrates for cholesterol sulfotransferase. J. Lipid Res. 48, 1343–1352 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Chen G., Head D. L., Mangelsdorf D. J., Russell D. W. Enzymatic reduction of oxysterols impairs LXR signaling in cultured cells and the livers of mice. Cell Metab. 5, 73–79 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbandian G., Kovats S. Understanding sex biases in immunity: effects of estrogen on the differentiation and function of antigen-presenting cells. Immunol. Res. 31, 91–106 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbandian G., Paharkova-Vatchkova V., Mao A., Nale S., Kovats S. The selective estrogen receptor modulators, tamoxifen and raloxifene, impair dendritic cell differentiation and activation. J. Immunol. 175, 2666–2675 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesange F. et al. Microsomal epoxide hydrolase of rat liver is a subunit of theanti-oestrogen-binding site. Biochem. J. 334(Pt 1): 107–112 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvente-Poirot S., Poirot M. Cholesterol metabolism and cancer: the good, the bad and the ugly. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 12, 673–676 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillasse M. R. et al. Signaling through cholesterol esterification: a new pathway for the cholecystokinin 2 receptor involved in cell growth and invasion. J. Lipid Res. 50, 2203–2211 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptissart M. et al. Bile acids: from digestion to cancers. Biochimie 95, 504–517 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilo C., Frank P. G. Cholesterol and breast cancer development. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 12, 677–682 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkerd E. J., Dowsett M. Influence of sex hormones on cancer progression. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4038–4044 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose T. E. et al. 1-Aryl-3-(1-acylpiperidin-4-yl)urea inhibitors of human and murine soluble epoxide hydrolase: structure-activity relationships, pharmacokinetics, and reduction of inflammatory pain. J. Med. Chem. 53, 7067–7075 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisseau C. et al. Development of metabolically stable inhibitors of mammalian microsomal epoxide hydrolase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 951–957 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni P., de Giovanni C., Lollini P. L., Nicoletti G., Prodi G. TS/A: a new metastasizing cell line from a BALB/c spontaneous mammary adenocarcinoma. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 1, 373–380 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari T. et al. Detailed characterization of the mouse glioma 261 tumor model for experimental glioblastoma therapy. Cancer Sci. 97, 546–553 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vantourout P. et al. Specific requirements for Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cell stimulation by a natural adenylated phosphoantigen. J. Immunol. 183, 3848–3857 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. et al. Mechanisms of melanogenesis inhibition by 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone. Br. J. Dermatol. 157, 242–248 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando H. et al. Possible involvement of proteolytic degradation of tyrosinase in the regulatory effect of fatty acids on melanogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 40, 1312–1316 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P. et al. Auraptene is an inhibitor of cholesterol esterification and a modulator of estrogen receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 827–836 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Tables S1-S3