Abstract

DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors are a major class of cancer chemotherapeutics, which are thought to eliminate cancer cells by inducing DNA double-strand breaks. Here we identify a novel activity for the anthracycline class of DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors: histone eviction from open chromosomal areas. We show that anthracyclines promote histone eviction irrespective of their ability to induce DNA double-strand breaks. The histone variant H2AX, which is a key component of the DNA damage response, is also evicted by anthracyclines, and H2AX eviction is associated with attenuated DNA repair. Histone eviction deregulates the transcriptome in cancer cells and organs such as the heart, and can drive apoptosis of topoisomerase-negative acute myeloid leukaemia blasts in patients. We define a novel mechanism of action of anthracycline anticancer drugs doxorubicin and daunorubicin on chromatin biology, with important consequences for DNA damage responses, epigenetics, transcription, side effects and cancer therapy.

Anthracycline-based drugs can kill cancer cells by inhibiting topoisomerase II and promoting DNA double-strand breaks. Pang et al. show that anthracyclines also induce eviction of histones from open chromatin regions and, in doing so, modulate DNA repair and apoptosis in human cancer cells.

Anthracycline-based drugs can kill cancer cells by inhibiting topoisomerase II and promoting DNA double-strand breaks. Pang et al. show that anthracyclines also induce eviction of histones from open chromatin regions and, in doing so, modulate DNA repair and apoptosis in human cancer cells.

Many critical signalling pathways driving cancer have been identified and yielded therapeutic agents targeting these pathways with varying success1,2. Although such agents usually have fewer side effects compared with conventional anticancer drugs, tumour resistance is usually swift. Consequently, conventional chemotherapy remains standard practice in cancer treatment, especially for aggressive tumours like acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Furthermore, modern cancer treatment increasingly combines conventional chemotherapeutic drugs with modern targeted anticancer drugs.

Doxorubicin (Doxo; also termed Adriamycin) is one of these ‘older’ conventional drugs3. Doxo is widely used as a first-choice anticancer drug for many tumours and is one of the most effective anticancer drugs developed4,5. Millions of cancer patients have been treated with Doxo, or its variants daunorubicin (Daun) and idarubicin (Ida)6. Currently these drugs are included in 500 reported trials worldwide to explore better combinations (ClinicalTrials.gov. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=%22doxorubicin%22+OR+%22adriamycin%22+OR+%22daunorubicin%22+OR+%22Idarubicin%22&recr=Open. (2013).). Doxo acts by inhibiting topoisomerase II (TopoII) resulting in DNA double-strand breaks7. Cells then activate the DNA damage response (DDR) signalling cascade to guide recruitment of the repair machinery to these breaks8. If this fails, the DNA repair programme initiates apoptosis8. Rapidly replicating cells such as tumour cells are presumed to exhibit greater sensitivity to the resulting DNA damage than normal cells, thus constituting a chemotherapeutic window. Other TopoII inhibitors have also been developed, including Doxo analogues Daun, Ida, epirubicin and aclarubicin (Acla) and structurally unrelated drugs such as etoposide (Etop) (Fig. 1a). Etop also traps TopoII after transient DNA double-strand break formation, while Acla inhibits TopoII before DNA breakage7. Exposure to these drugs releases TopoIIα from nucleoli for accumulation on chromatin (Supplementary Fig. S1). Although these drugs have identical mechanisms of action, Etop has fewer long-term side effects than Doxo and Daun, but also a narrower antitumour spectrum and weaker anticancer efficacy4. The overall properties of Acla remain undefined because of its limited use. Despite its clinical efficacy, application of Doxo/Daun in oncology is limited by side effects, particularly cardiotoxicity, the underlying mechanism of which is not fully understood9. Although the target of both anthracyclines and Etop is TopoII, as identified decades ago10,11, additional mechanisms of action are not excluded as these drugs in fact have different biological and clinical effects. Defining these is important to explain effects and side effects of the drugs and support rational use in (combination) therapies.

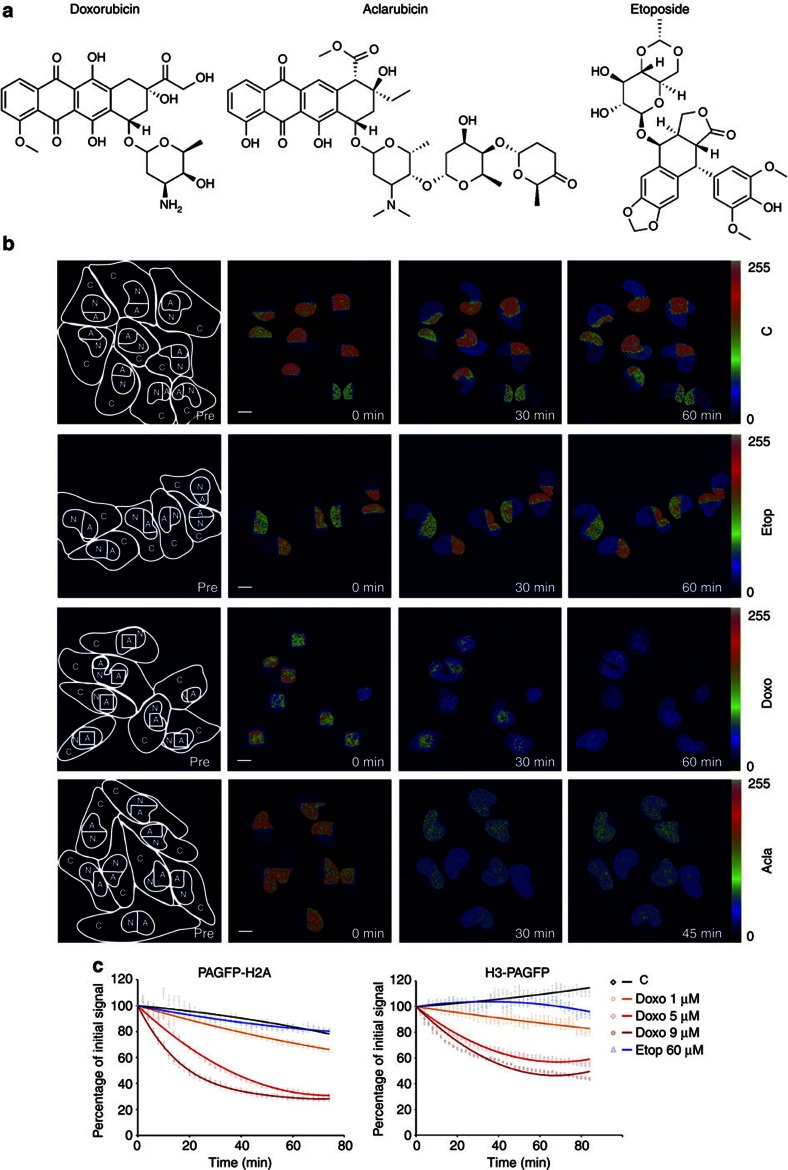

Figure 1. Histone eviction by Doxo.

(a) Chemical structures of three TopoII inhibitors doxorubicin, its variant aclarubicin and the structure of etoposide. (b) Part of the nucleus from MelJuSo cells expressing PAGFP-H2A was photoactivated. The cells were exposed to 9 μM Doxo, 60 μM Etop or 20 μM Acla for the time points indicated and the fate of PAGFP-H2A was monitored by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). The lines in the left panel show the cell boundaries (C), the nucleus (N) and the activated area (A). The fluorescence intensities are shown in false colours as indicated by the ‘Look-Up Table’. C, untreated control. Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) Quantification of the fluorescence in the photoactivated area of MelJuSo cells expressing PAGFP-H2A or H3-PAGFP after exposure to Etop or different concentrations of Doxo. Cells were monitored as in Fig. 1b. Data points are the mean fluorescence. Trend lines are drawn over experimental data (n=30 to 50 cells, error bar indicates s.e.m.).

Here we apply modern technologies on an ‘old’ but broadly used anticancer drug to characterize new activities and consequences for cells and patients. We integrate biophysics, biochemistry and pathology with next generation sequencing and genome-wide analyses in experiments employing different anticancer drugs with partially overlapping effects. We observe a unique feature for the anthracyclines not shared with Etop: histone eviction from open and transcriptionally active chromatin regions. This novel effect has various consequences that explain the relative potency of the Doxo and its variants: the epigenome and thus the transcriptome are altered and DDR is attenuated. Histone eviction occurs in vivo and is highly relevant for apoptosis induction in human AML blasts and patients. Our observations provide new rationale for the use of anthracyclines in monotherapy and combination therapies for cancer treatment.

Results

Doxo induces histone eviction in live cells

We have observed loss of histone ubiquitination by proteasome inhibitors12 and Doxo treatment, without the initiation of apoptosis. Proteasome inhibitors but not Doxo altered the ubiquitin equilibrium. We next tested whether loss of histone ubiquitination may in fact represent loss of histones and examined the effect of Doxo and other TopoII inhibitors on histone stability in living cells.

Importantly, we aimed at mimicking the clinical situation in our experimental conditions. We exposed cells to empirical peak-plasma levels of 9 μM Doxo or 60 μM Etop as in standard therapy13,14,15 (DailyMed:ETOPOSIDE. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=fd574e51-93fd-49df-92bc-481d0023505e (2010).) and analysed samples after 2 or 4 h. Alternatively, cells were further cultured after 2-h drug exposure with extensive washing to approximate the pharmacokinetics of these drugs. The majority of cells endured this treatment when assayed 24 h after drug removal (Supplementary Fig. S2).

To probe the stability of histones, histone variants coupled to photo-activatable green fluorescent protein (PAGFP) were expressed in human melanoma cell line MelJuSo. Defined regions of nuclei were photoactivated by 405 nm laser light and the fate of the fluorescent histone pool was monitored following Doxo, Etop or Acla exposure by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Histone PAGFP-H2A was stably integrated into the chromatin of control or Etop-exposed cells, but was released when exposed to Doxo or Acla (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. S3). The anthracyclines Daun and Ida showed similar results, which suggests that histone release from chromatin represents a general property of anthracyclines (Supplementary Movies 1–6). These results also imply that histone eviction is independent of TopoII inhibition (as Etop does not evict histones; further confirmed by silencing TopoIIα before Doxo exposure, Supplementary Fig. S4), DNA double-strand break formation (Acla does not induce breaks) or apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S5). Histone eviction by anthracycline exposure was confirmed for histone H3- and H4-PAGFP (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. S6a). The eviction of photoactivated histone variants by Doxo was dose- and time-dependent, and ~30% of histones were released from the activated region (Fig. 1c). Of note, the fates of evicted H2A/H2B and H3/H4 differed, as liberated H2A and H2B were relatively stable in the nucleoplasm, while significant portions of H3 and H4 were destroyed (Supplementary Fig. S6). Doxo and Acla also evicted endogenous H2A from chromatin and free histones were detected in the soluble fraction of treated cells (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Doxo evicts histones from reconstituted nucleosomes in vitro

Induced histone eviction has not been previously observed. How do Doxo and Acla evict histones? To address this, we silenced a series of chromatin modifiers (Supplementary Table S1), but failed to quench Doxo-mediated histone eviction. Histone eviction may also result from intercalation of the anthracyclines Doxo (or Acla) into particular chromatin structures independent of active processes. As Doxo uptake and accumulation require ATP (Supplementary Fig. S8), MelJuSo/PAGFP-H2A cells were permeabilized with Triton X-100 to allow direct access of drugs to chromatin. At the same time soluble materials were removed from chromatin, thus stalling ATP-dependent processes. Doxo and Acla still induced histone eviction (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. S9), suggesting that this does not involve ATP-dependent support. Histone eviction is specific to anthracyclines, as Etop and ethidium bromide failed to evict histones (Supplementary Fig. S10). Anthracyclines consist of a common tetracycline ring and one or multiple amino sugars. The structure of Doxo in the DNA double helix shows the amino sugar interacting with DNA bases in the DNA minor groove16. The aglycan form of Doxo, doxorubicinone (Doxo-none) failed to evict histones from permeabilized cells (Fig. 2a), indicating that the amino sugar is critical for histone eviction.

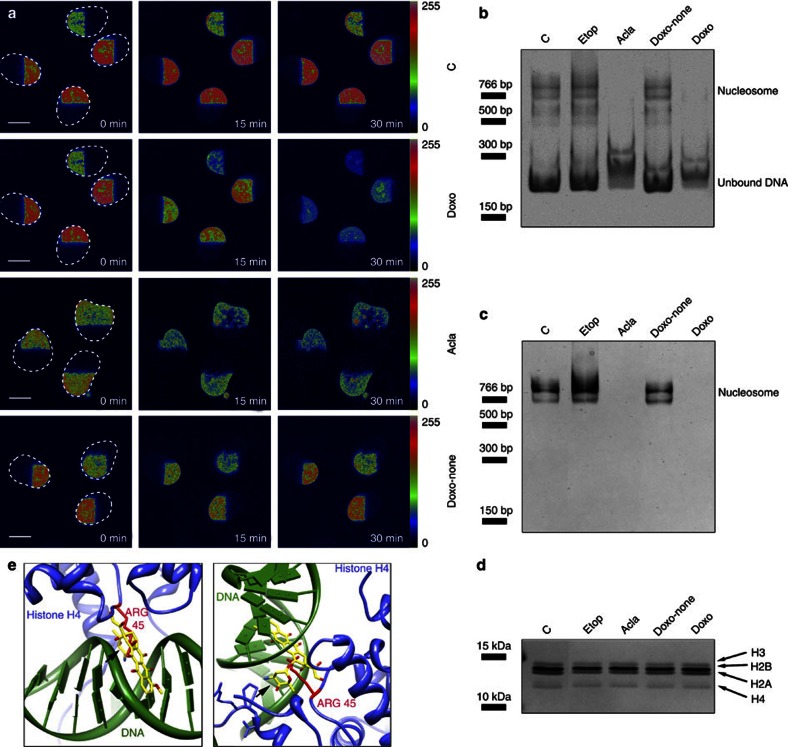

Figure 2. Intercalation of Doxo into DNA suffices to induce histone eviction from nucleosomes.

(a) MelJuSo cells expressing PAGFP-H2A were permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100 before parts of the nucleus were photoactivated by 405 nm light. The photoactivated nuclei were followed in time by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) before or after exposure to 9 μM Doxo, 20 μM Acla or 20 μM Doxorubicinone (Doxo-none), as indicated. Fluorescence intensities shown in false colours and the boundaries of the nuclei are indicated. C, untreated control. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) In vitro assembled single nucleosomes were treated with 60 μM Etop, 20 μM Doxo, 20 μM Acla or 20 μM Doxorubicinone for 4 h as indicated. C, untreated control. Samples were analysed by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr). Position of assembled nucleosomes and free DNA are indicated. (c) The same gel in b was subsequently stained with silver to visualize the histones in the nucleosomes. Position of assembled nucleosomes is indicated. (d) The same samples as in b and c were analysed by SDS–PAGE and silver-stained to show that equal amounts of histones and reconstituted single nucleosomes were present in the different lanes. Positions of histone variants are indicated. (e) A model of Doxo intercalation in chromatin, with the sugar moiety of Doxo competing with H4 amino acids for access to space in the DNA minor groove. Doxo has been cocrystallized with a segment of the DNA double helix (PDB: 1D12). The nucleosome structure has been crystallized (PDB:1AOI) but without Doxo. Doxo, based on the Doxo-DNA structure, was docked into the nucleosome structure (using programme UCSF Chimera). Shown is a snapshot of the relevant area of the Doxo-chromatin model under two angles. DNA is visualized in green, Doxo in yellow, histone H4 in blue and the H4-arginine residue (at position 45) that enters the DNA minor groove is shown in red. The amino sugar of Doxo (shown by arrow) also fills the DNA minor groove and makes various interactions with DNA bases.

Even in permeabilized systems, a contribution of proteins cannot be excluded. We, therefore, reconstituted single nucleosomes from recombinant histones and DNA, before exposure to the various drugs. Reconstituted single nucleosomes migrated slower than free DNA on native gels, as detected either by ethidium bromide staining for DNA (Fig. 2b) or by silver staining for histones (Fig. 2c). Doxo and Acla (unlike Etop or Doxo-none) dissociated nucleosomes in this in vitro setting. The dissociated histones were invisible under native conditions as they are basic and moved from the native gel to the negative pole. Analysis of the same samples under fully denaturing conditions confirmed equal amounts of input nucleosomes/histones (Fig. 2d). This in vitro reconstituted system unambiguously demonstrates that the chemical nature of Doxo or Acla suffice to dissociate nucleosomes for histone release.

We combined the structures of DNA-Doxo (ref. 16) and nucleosomes17 to show how Doxo may affect nucleosome structure (Fig. 2e). The model predicts that the amino sugar group of Doxo competes for space with the H4-arginine residue in the DNA minor groove. This H4-residue-DNA interaction stabilizes the nucleosome structure17. Acla contains three sugars attached to the tetracycline ring and likely shares the same mechanism of histone eviction. As the aglycan form of Doxo does not evict histones, this model suggests that incorporation of the Doxo tetracycline ring into the DNA double helix positions the amino sugar in the DNA minor groove. The sugar group competes for space with residues of histones important for nucleosome stability, resulting in chromatin destabilization.

Doxo-induced histone eviction impairs DDR

An early response to DNA double-strand breaks is the phosphorylation of histone variant H2AX by ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, which is essential for the propagation of DDR signals from damaged sites8. Consequently, phosphorylated H2AX (γ-H2AX) is used as a node for active DDR18. The subsequent spatial and temporal arrangement of DDR complexes at DNA breaks is critical for the damage response and repair8. If Doxo combines local H2AX eviction with DNA damage, the ensuing repair should be attenuated. We tested whether Doxo also evicts H2AX following photoactivated PAGFP-H2AX in MelJuSo cells. The PAGFP modification of H2AX did not affect phosphorylation after Etop exposure (Supplementary Fig. S11), while Doxo evicted PAGFP-H2AX (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. S12). We visualized endogenous γ-H2AX formation in MelJuSo cells exposed to Doxo or Etop. γ-H2AX was strongly induced by Etop but considerably less by Doxo (Fig. 3b), even at concentrations yielding similar levels of DNA double-strand breaks (Fig. 3d). Factors acting downstream of γ-H2AX, such as MDC119, also poorly stained Doxo-treated cells compared with Etop-exposed cells (Supplementary Fig. S13). This attenuation of γ-H2AX formation is not due to general DDR pathway inhibition, but may result from H2AX eviction preventing phosphorylation by ATM at the DNA breaks. Consequently, downstream events such as phosphorylation of ATM substrates, feedback signalling pathways including phosphorylation of MRE11 (ref. 20) (Supplementary Fig. S14) and ultimately overall DDR are attenuated following Doxo exposure.

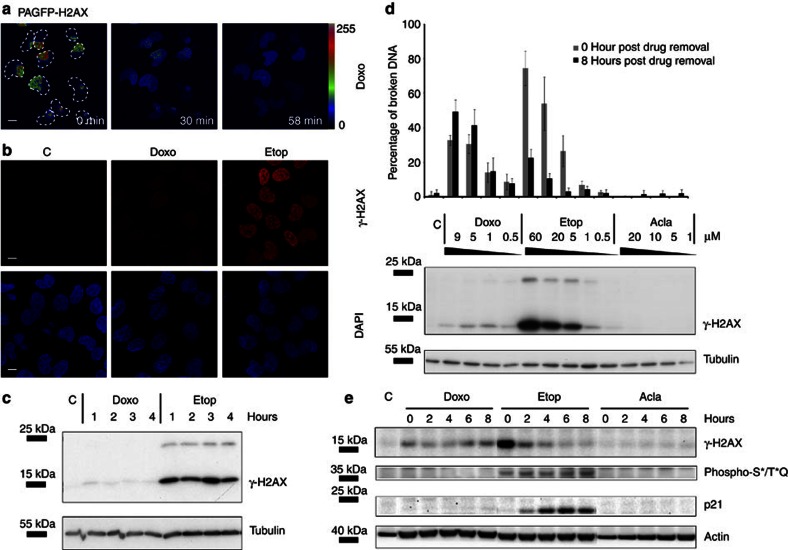

Figure 3. Doxo induces H2AX eviction and attenuates DDR.

(a) Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells expressing PAGFP-H2AX was activated before exposure to Doxo. The boundaries of nuclei are indicated. Fluorescence intensities are shown in false colours. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) MelJuSo cells were treated with 9 μM Doxo or 60 μM Etop for 2 h before fixation and stained for γ-H2AX (top panel in red). Bottom panel in blue indicates DAPI staining of the nuclei of cells. C, untreated control. Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) MelJuSo cells were treated with 9 μM Doxo or 60 μM Etop and lysed at indicated time points before analyses of γ-H2AX by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and western blotting (WB). Tubulin is used as a loading control and the positions of molecular weight markers are indicated. (d) MelJuSo cells were exposed to various concentrations of Doxo, Etop or Acla for 2 h. C, untreated control. Drugs were removed by extensive washing. DNA double-strand breaks, immediately after 2 h drug treatment or 8 h post drug removal were quantified by constant-field gel electrophoresis and expressed as percentage of total DNA (n=3 independent experiments, error bar indicates s.d.). Western blotting indicates the γ-H2AX response after 2 h drug treatment at different concentrations; tubulin is shown as loading control. (e) MelJuSo cells were exposed to 9 μM Doxo, 60 μM Etop or 20 μM Acla for 2 h. Drugs were removed and further cultured for the times indicated. Cells were lysed, separated by SDS–PAGE and WB was probed with the antibodies indicated. Actin is used as loading control and positions of marker are indicated. C, untreated control.

We directly visualized the consequences of Doxo, Etop or Acla on DNA damage induction and repair by constant-field gel electrophoresis allowing detection of DNA double-strand breaks21,22. Broken DNA migrates faster than intact DNA and the percentage of DNA double-strand breaks including >1 Mb fragments can be quantified22 (Fig. 3d). Unlike Acla, Etop effectively induced DNA breaks at 2 h after drug exposure followed by efficient repair by 8 h after drug removal. Conversely, DNA repair was delayed after Doxo removal (Fig. 3d), in line with earlier observations23, as compared with Etop-exposed cells. Proper DDR after Etop removal was also deduced from decreased γ-H2AX staining, whereas γ-H2AX persisted in Doxo-exposed cells (Fig. 3e). The delayed onset of secondary DDR signalling effects following Doxo removal included delayed p21 expression and attenuated ATM/ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) activation (Fig. 3e). Collectively, these observations illustrate that the TopoII inhibitors Doxo and Etop both generate DNA double-strand breaks, yet differ in solving this problem. This might be the consequence of the new effect of Doxo on histone eviction, which could impair the DDR signalling cascade by evicting H2AX thus obstructing normal DNA damage repair.

Doxo alters the transcriptome

Histones carry different epigenetic modifications that can be lost by eviction following Doxo exposure. After drug removal (or clearance from the patient’s circulation), the evicted histones may reintegrate into chromatin (Supplementary Fig. S15) or be replaced by newly synthesized histones. This would affect the epigenetic code associated with these histones and then the transcriptome. To test this, MelJuSo cells were exposed for 2 h to Doxo, Etop or Acla. After drug removal, cells were cultured for 1 day or 6 days before microarray analysis. Doxo and Acla exposure exhibited strong effects on the transcriptome (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. S16a). More than twice the number of differentially expressed genes was observed 1 day after treatment with Doxo or Acla as compared with Etop. This was unrelated to responses to DNA damage and DDR signalling, which were strongest for Etop (Fig. 3d). Similar results were observed for human colon cancer cell line SW620 (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. S16a). To test whether Doxo always affects the same set of genes, microarray experiments were independently repeated. The same set of genes was differentially regulated after Doxo exposure, suggesting specific effects of Doxo on the transcriptome of cells (Supplementary Fig. S16). The genes differentially expressed in MelJuSo cells 1 day after exposure to the drugs were analysed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Etop showed a strong enrichment for genes in the DDR, while other pathways were selectively affected by Doxo and Acla (Supplementary Data 1). Though Doxo and Etop both inhibit TopoII for DNA double-strand break formation, they affect different pathways in cells. This may be due to the novel activity of Doxo on histone eviction. The transcriptional differences between Doxo and Acla may result from additional effects on DNA double-strand breaks following Doxo exposure but this has not been studied further.

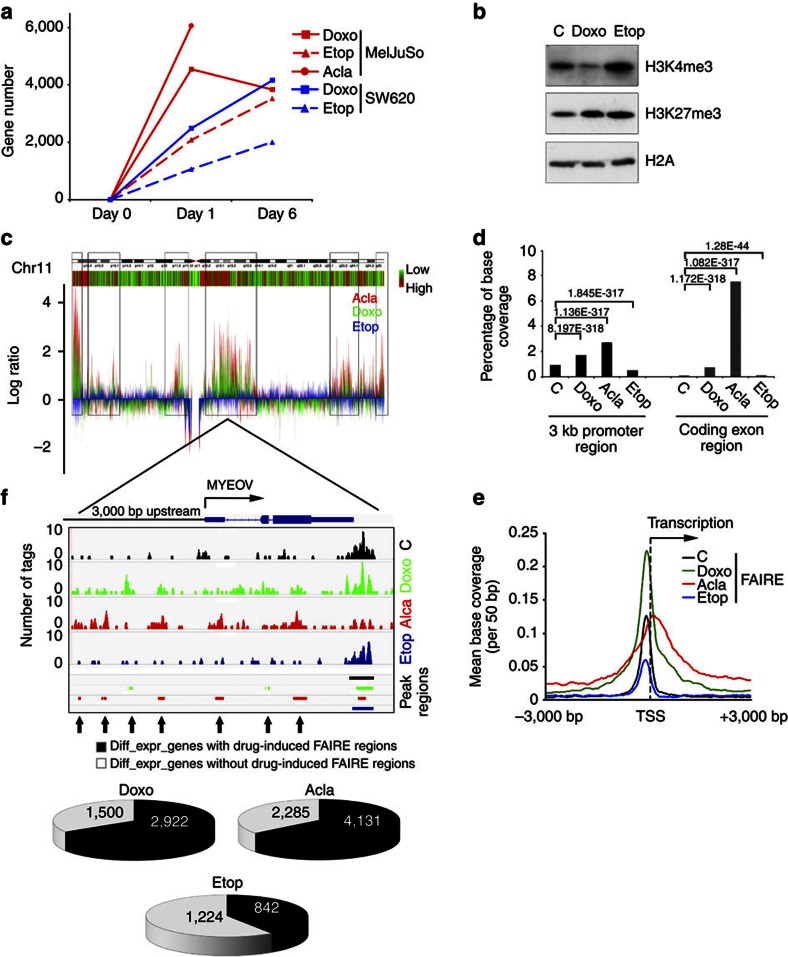

Figure 4. Selective histone eviction and transcriptome changes by Doxo and Acla.

(a) MelJuSo or SW620 cells were exposed to 9 μM Doxo, 10 μM Acla or 60 μM Etop for 2 h. The drugs were removed and cells were cultured for 1 day or 6 days. Line was discontinued day 1 after Acla exposure due to apoptosis later during culture. Microarray analyses were performed for all samples. Plotted are the genes with more than twofold difference in expression compared with non-treated cells. (b) Endogenous histone modification changes by Doxo. MelJuSo cells were treated with 9 μM Doxo or 60 μM Etop for 4 h. Chromatin was isolated, separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and western blotting (WB) probed with antibodies against the histone modifications indicated. Histone H2A is used as loading control. (c) MelJuSo cells were exposed to 9 μM Doxo, 20 μM Acla or 60 μM Etop for 4 h before histone-free DNA fragments were isolated by FAIRE followed by next generation sequencing. Shown is chromosome 11, with a green–red bar showing the corresponding relative gene density. The sequenced reads (Acla, red; Doxo, green; Etop, blue) of the different treatments were normalized and compared with control cells. The boxed areas indicate sites more efficiently isolated by FAIRE and their positions in the gene density bar. (d) Annotation of FAIRE-seq peak regions. The peak-region coverage was enriched in the coding exon and promoter regions compared with control cells, due to anthracycline treatments. P-values were calculated with Fisher’s exact test. (e) Distribution and enrichment of FAIRE regions around TSS. The peak regions from FAIRE-seq were enriched around the TSS for all RefSeq genes. (f) Drug-induced peak regions defined by FAIRE-seq after 4 h Doxo or Acla treatment were compared with the differentially expressed genes in MelJuSo cells 24 h after the respective drug exposure (relative to the control cells). This is illustrated for gene MYEOV located on chromosome 11. The FAIRE-seq reads and peak regions called for the different conditions are indicated. Black area in the pie charts defines differentially expressed genes with drug-induced FAIRE peak regions (relative to control cells) within 3 kb upstream of the TSS or on the gene bodies. The new peak regions induced by Doxo and Acla exposure are indicated by arrows.

Selectivity of histone eviction for open chromatin regions

As chromatin has different conformational states24,25, we wondered whether Doxo would show any selectivity in histone eviction. We analysed multiple histone markers in the chromatin fraction from cells exposed to drugs for 4 h (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Fig. S17). Doxo treatment decreased histones marked by H3K4me3 (found around active promoter regions)25 representing transcriptionally active loose chromatin structures. By contrast, no reduction of H3K27me3 in chromatin was observed (Fig. 4b). H3K27me3 associates with inactive/poised promoters and polycomb-repressed regions representing compact chromatin25. These data suggest that Doxo induces histone eviction from particular chromatin regions.

To define preferred regions of histone eviction by Doxo and Acla in a genome-wide fashion and at higher resolution, we performed formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements coupled to next generation sequencing (FAIRE-seq) on MelJuSo cells treated 4 h with Doxo, Acla or Etop to identify histone-free DNA26,27. After formaldehyde fixation of histone–DNA interactions and mechanical DNA breakage, chromatin was exposed to a classical phenol–chloroform extraction to accumulate histone-free DNA in the aqueous phase and protein-bound DNA fragments in the organic phase26 (Supplementary Fig. S18a,b). The histone-free DNA fragments in the aqueous phase were subjected to next generation sequencing. In control cells, we observed standard enrichment of the FAIRE-seq signals around the promoter regions (Supplementary Fig. S18c), which positively correlated to the expression level of genes26. To globally visualize the histone-evicted regions of drug-treated cells, the sequenced read counts were normalized and compared with control cells (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Fig. S19; Supplementary Data 2 for summary of next generation sequencing runs). Exposing MelJuSo cells to Doxo or Acla markedly enriched histone-free DNA fragments from particular regions of the chromosome unlike Etop exposure. Further annotation of FAIRE-seq peak regions revealed a strong enrichment of histone-free DNA in promoter and exon regions after Doxo or Acla exposure (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. S20a). Doxo and Acla acted not identical yet very similar (50% overlap in enriched promoter regions, Supplementary Fig. S20b,c). This may be due to a different mode of binding to TopoII or differences in the sugar moiety that may position these drugs differently in chromatin structures.

The FAIRE-seq peak regions representing histone-free DNA were often found around transcription starting sites (TSS)26 and further enriched by Doxo or Acla treatment (Fig. 4d). The boundaries of the histone-free zones around the TSS were broadened by Doxo or Acla (Fig. 4e), suggesting that histone eviction extends beyond the open chromatin structure detected in control or Etop-exposed cells that share similar confined peak-region boundaries. There are also new open promoter regions induced by Doxo or Acla (Supplementary Fig. S20d). The Doxo-induced expansion of histone-free regions correlates with a shift of H3K4me3 peak regions by some 100 bp (Supplementary Fig. S21). However, the H3K27me3 mark did not change under these conditions (Supplementary Fig. S22). Further analysis indicates that the shift in H3K4me3 peak regions correlated to gene activity. It suggests that the differences of chromatin structure between active and inactive genes are sensed by Doxo (Supplementary Fig. S21). It also indicates that epigenetic markers can be repositioned by Doxo, both during and post treatment (unrelated to DNA breaks as Acla, but not Etop, exposure also alters this marker). Again, Acla acts not identical to Doxo and has additional effects on H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 marks (Supplementary Figs S21,S22). The histone eviction induced by Doxo or Acla was observed in multiple cell lines including colon cancer cell line SW620 (Supplementary Fig. S23). As most genes are commonly expressed, the anthracyclines affected many shared regions between two cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S23d).

To test the relationship between histone eviction and transcriptome alterations, both data sets from MelJuSo cells were integrated (Fig. 4f). We reasoned that Doxo- or Acla-induced histone eviction in promoter regions (defined as 3 kb upstream of the TSS) and gene body regions would affect transcription of the genes directly. This correlation was detected in 70% of genes differentially expressed by Doxo, Acla but not Etop treatment (Fig. 4f; Supplementary Fig. S24). This suggests that Doxo and Acla locally affect chromatin structure and epigenetic modifications, resulting in altered transcription of neighbouring genes as exemplified by the MYEOV gene (Fig. 4f; more genes and statistics in Supplementary Fig. S24).

Tissue selective effects of Doxo and histone eviction in vivo

A major side effect of Doxo is cardiotoxicity28. Balanced transcription is critical in functioning of many tissues including heart29. We wondered whether Doxo (unlike Etop) would affect histones and the transcriptome in vivo. As Acla is an infrequently used anticancer drug with poorly understood pharmacokinetics in mice, this drug was not included.

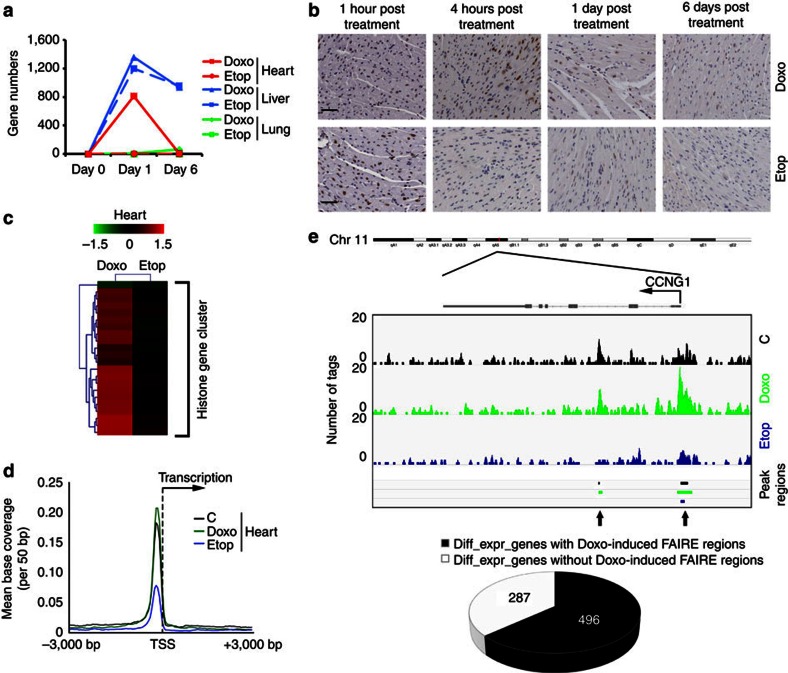

1 day or 6 days post Doxo or Etop administration, various tissues were isolated for gene expression analyses. This was performed in biological duplicate and yielded strongly reproducible sets of altered transcripts (Supplementary Fig. S25a). Three effects were observed in mice. Firstly, Doxo and Etop did not alter the transcriptome of the lung (Fig. 5a). Secondly, both Doxo and Etop deregulated a strongly overlapping set of genes in the liver, even after 6 days (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Fig. S25b). This suggests that the DDR and detoxification pathways may prevail in liver (Supplementary Data 3). Thirdly, Doxo selectively altered the transcriptome of heart (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Fig. S25a). Why different tissues respond differently is unclear but may relate to the extent of open chromatin and the exposure to Doxo. Altered transcription in the heart by Doxo has been correlated to cardiotoxicity and associated to DNA damage by inhibition of TopoIIβ (ref. 30). We observed that the heart transcriptome was altered at 24 h and restored 6 days post application of Doxo. However this cannot be solely attributed to DNA damage, as Etop did not alter heart transcription (Fig. 5a), despite the similar level of initial DDR in tissues (Fig. 5b, γ-H2AX staining). Pathology staining of mouse heart and liver showed a similar trend of DDR signalling as in the tissue culture cells. γ-H2AX staining quickly disappeared when mice were treated with Etop, probably due to proper DDR and DNA damage repair, while Doxo-indced DNA damage marks persisted over a long period, similar to tissue culture cells (comparing Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S26a with Fig. 3e). This may result from DDR delay following Doxo-induced histone eviction. In addition, histology of heart specimens did not show any apoptosis, immune cell infiltration or other abnormalities resulting from drug application (Supplementary Fig. S26b), indicating that the altered transcriptome was a direct consequence of Doxo exposure.

Figure 5. In vivo responses to Doxo or Etop treatments.

(a) Expression data were generated from lungs, livers or hearts of mice 1 day or 6 days after intravenous bolus injection of Doxo or Etop and compared with expression data in respective organs from untreated mice. Significantly changed genes were calculated with linear models for microarray data, based on two mice per data point. (b) Hearts of drug-treated mice were collected at indicated time points for fixation and staining with anti-γ-H2AX antibodies. Time of sampling and drug treatment is indicated. Scale bar, 50 μm. (c) Heat map showing the expression of histone gene cluster in the hearts of Doxo- or Etop-treated mice relative to control mice. Colour indicates the log-fold change compared with control. (d) FAIRE-seq peak regions from the hearts of mice 4 h after Doxo exposure were enriched around TSS of all RefSeq genes in mice. (e) Peak regions of FAIRE-seq from mouse hearts 4 h post Doxo or Etop injection are compared with genes differentially regulated at 1 day after injection. Top: Illustration of FAIRE-seq reads, as well as the peak regions of the gene CCNG1 for the three conditions. TSS is indicated. Black area in the pie charts defines differentially expressed genes with Doxo-induced FAIRE peak regions (relative to control cells) within 3 kb upstream of the TSS or on the gene bodies (P-value=1.914E-26 related to the whole genome, calculated with Fisher’s exact test). The new peak regions induced by Doxo exposure are indicated by arrows.

Of note, Doxo strongly increased histone gene expression in mouse heart and liver (Fig. 5c; Supplementary Fig. S25a,c), which usually occurs only during cell division31. Immuno-histochemistry did not reveal any dividing Ki-67 positive cells in the heart (Supplementary Fig. S26c), suggesting a compensation for loss of histones after eviction by Doxo rather than a response to cell division. In addition, when the genes differentially regulated in heart following Doxo exposure were subjected to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, a strong and significant enrichment of genes acting in tumoricidal function of hepatic natural killer cells and interferon signalling pathways was observed (Table 1; Supplementary Data 3). Interferons are indeed associated to cardiotoxicity32,33, possibly by inducing signalling pathways similar to those induced by Doxo.

Table 1. Pathways enriched in the heart after Doxo treatment.

| Ingenuity canonical pathways | P-value | Ratio | Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumouricidal function of hepatic natural killer cells | 0.000467735 | 2.50E-01 | 6 |

| Interferon signalling | 0.001230269 | 2.31E-01 | 6 |

| 14-3-3-mediated signalling | 0.005370318 | 1.08E-01 | 12 |

| Granzyme A signalling | 0.00616595 | 2.22E-01 | 4 |

| p53 signalling | 0.007585776 | 1.12E-01 | 10 |

| NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response | 0.010471285 | 8.52E-02 | 15 |

Enrichment of pathways from differentially regulated genes in the hearts 24 h post Doxo treatment was determined by Ingenuity Systems Pathway Analysis. Shown are the most significant pathways.

To test whether Doxo evicts histones from chromatin in vivo, mice were injected with Doxo or Etop, and hearts were isolated for FAIRE-seq 4 h later. Similar as in cell lines, FAIRE-seq on heart tissue showed a higher enrichment of FAIRE peak regions (that is, histone-free DNA fragments) around TSS only after Doxo treatment (compare Fig. 5d with Fig. 4e). To correlate Doxo-induced histone eviction to transcriptome changes in the heart, the FAIRE-seq data were integrated into the microarray results. Again presence of Doxo-induced FAIRE-seq peak regions within the promoter regions or the gene bodies was observed for over 70% of transcripts differentially altered in Doxo-treated heart (Fig. 5e; more genes, Supplementary Fig. S27), similar to observations in tissue culture cells. These suggest that Doxo both induces a reproducible set of transcripts 24 h after injection and evicts histones from the same genomic areas.

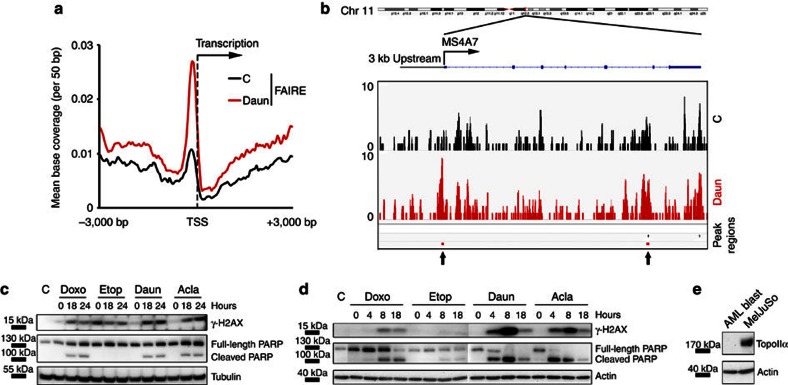

Apoptosis induction of AML blasts by histone eviction

To test the relevance of histone eviction by anthracyclines for human cancer, we selected a tumour type where samples can be obtained before and during treatment with anthracyclines. AML patients have large numbers of circulating malignant cells (blasts) at diagnosis. Standard remission induction regimens consist of anthracyclines such as Daun and Ida followed by cytarabine, resulting in over 70% complete remission34. Daun and Ida are Doxo variants and also induce histone eviction in MelJuSo/PAGFP-H2A cells (Supplementary Movie 5,6). AML blasts were isolated from patients before and 2 h post intravenous bolus injection with Daun only, and immediately processed for FAIRE-seq analysis. A strong enrichment of FAIRE-seq peak regions surrounding the TSS regions was observed after Daun exposure (Fig. 6a), similar as observed for cell lines and mouse tissues. This effect is illustrated for one gene (MS4A7) where histone eviction (more sequence reads) is shown in the promoter region (Fig. 6b; more genes, Supplementary Fig. S28). These results confirm histone eviction activity of anthracyclines in the most relevant clinical setting.

Figure 6. Histone eviction effect of anthracyclines on AML patients and blasts.

(a) FAIRE-seq peak regions from blasts of an AML patient isolated before (black) and 2 h post (red) Daun infusion. Enrichment of peak regions around TSS of all RefSeq genes is shown. (b) Illustration of FAIRE-seq reads, as well as the peak regions of the gene MS4A7 of AML blasts isolated before and 2 h after completion of Daun infusion in an AML patient. The location of TSS and the 3 kb upstream region, as well as the intron and exon regions of the gene are indicated. The new peak regions induced by Daun exposure are indicated by arrows. (c) MelJuSo cells were exposed to 9 μM Doxo, 60 μM Etop, 10 μM Daun or 10 μM Acla for 2 h. Drugs were removed and cells were further cultured for the time points indicated. Cells were lysed, separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and western blotting (WB) was probed with the antibodies indicated. Tubulin is used as a loading control and positions of marker are indicated. The positions of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and the PARP cleavage product are indicated. C, untreated control. (d) Primary blast cells isolated freshly from an AML patient were exposed to 9 μM Doxo, 60 μM Etop, 10 μM Daun or 10 μM Acla for 2 h. Drugs were removed and cells were further cultured for the time points indicated. Cells were lysed, separated by SDS–PAGE and WB was probed with the antibodies indicated. Actin is used as a loading control and positions of PARP, the PARP cleavage product and marker proteins are indicated. C, untreated control. (e) MelJuSo cells and primary blast cells isolated freshly from AML patient were analysed by WB to compare the level of TopoIIα. Actin is used as a loading control and positions of marker proteins are indicated.

Anthracyclines such as Doxo, Daun or Ida have two different activities: DNA break formation and, as shown in this study, histone eviction. To determine their relevance in apoptosis induction of tumours, we compared Doxo and Daun with Acla (that only induces histone eviction) and Etop (that only generates DNA breaks). MelJuSo cells were exposed to these drugs for 2 h followed by drug removal and further culture. Cells were collected 18 or 24 h later and analysed for apoptosis induction, as visualized by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage. Doxo, Acla, as well as Daun strongly induced apoptosis (Fig. 6c), unlike Etop, despite its initial strong DNA damage induction and DDR signals (Fig. 3d). It should be noted that secondary strong induction of γ-H2AX was also observed for Doxo, Acla and Daun (Fig. 6c), which is a response to apoptosis initiation and DNA fragmentation35. AML blasts isolated freshly from a cancer patient (who responded to the Daun treatment) were also exposed ex vivo to the respective drugs and identical results were observed. Anthracyclines but not Etop efficiently induced apoptosis (Fig. 6d). In AML blasts, initial DDR in terms of γ-H2AX was low with all treatments, possibly because of low TopoII expression in AML patients’ blast cells36,37. We then determined the expression of TopoIIα in AML blasts and MelJuSo cells. TopoIIα could not be observed in isolated AML blasts unlike in MelJuSo cells (Fig. 6e). Free histones can induce apoptosis38,39 and drive cell death following histone eviction by the anthracyclines. Acla that does not induce DNA breaks is also used to treat AML40,41, which suggests that induction of histone eviction can be a more dominant factor for cytotoxicity of AML blasts, as Etop is usually ineffective. Collectively, we describe a novel effect of anthracyclines, histone eviction. The anthracyclines are cytotoxic to AML tumours even when not expressing their accepted target TopoIIα. This suggests that histone eviction may suffice to induce apoptosis of tumours in certain cases, yet the additional effects on DDR, epigenetics and the transcriptome may further support antitumour effects with associated side effects in normal tissues.

Discussion

We have compared the activities of four TopoII inhibitors with different antitumour effects in the clinic. The activities of Acla and Etop unite in Doxo and Daun, which not only induce DNA double-strand breaks due to TopoII inhibition (an established mechanism shared with Etop), but also instigate histone eviction from open chromatin structures (shared with Acla). We propose three possible consequences of histone eviction: attenuated DDR, epigenetic alterations and apoptosis induction. Acla also shows marked toxicity that cannot be attributed to DNA damage but may be more selectively due to histone eviction. As free histones induce apoptosis38,39, this effect may be critical for elimination of primary AML blasts.

Doxo, Daun and Etop trap TopoII after the formation of transient DNA double-strand breaks for permanent DNA damage. An essential component in the DDR cascade, histone variant H2AX, is also evicted by Doxo or Daun and cannot be not phosphorylated by ATM/ATR at the DNA damage sites. This may markedly delay DNA repair. This is different from Etop, which fails to evict histones allowing H2AX phosphorylation and swift DNA repair. As a result, Doxo-treated cells or mouse tissues show markedly prolonged DDR signalling after drug clearance when compared to Etop. Signalling for apoptosis is then stretched, which may contribute to the broader and more intense anticancer effects of Doxo in the clinic. Eviction of modified histones could also yield epigenetic changes, either following reintegration of modified histones or reinsertion of newly synthesized histones. Consequently, the transcriptome is altered, but in a surprisingly consistent manner. One possible explanation is that Doxo targets defined areas and genes, specified by open chromatin, for histone eviction.

Cardiotoxicity is the major side effect of anthracyclines, the reason of which is still unclear. In vivo experiments reveal that tissues respond differently to Doxo. We observed that DDR was consistently prolonged in Doxo-treated mice, as shown by persistent γ-H2AX staining in various tissues tested. DNA damage induced by Doxo is also important as deletion of TopoIIβ in the heart reduces Doxo-induced cardiotoxicity in mouse30. However, Etop also targets TopoIIβ (refs 42, 43) and induces DNA damage in the heart as shown here, without altering the transcriptome and inducing cardiotoxicity44. This suggests that additional mechanisms should contribute to cardiotoxicity induced by Doxo, and it may include impaired DDR, persistent DNA damage signalling and transcriptome changes. Doxo also selectively induced interferon-regulated genes in the heart. Such genes are normally suppressed by H3K9me2 (ref. 45), which may be evicted and replaced in response to Doxo, thereby unleashing transcription. Finally, loss of histones and changes in chromatin structure usually correlate with aging46, and this process may be further accelerated in the hearts of Doxo-treated patients that develop heart problems. Doxo has multiple effects on DNA and chromatin, and these multiple mechanisms may collaborate on inducing cardiotoxicity.

The novel effect of anthracycline—histone eviction—and its consequences on DDR signalling, epigenetics and apoptosis induction may have consequences for combination therapies where the timing of the drug application is of great importance47. Sequential treatment with two drugs including an anthracycline may yield new and synergizing effects that could benefit cancer patients, based on the novel properties of anthracyclines described here.

Drugs capable of selectively altering epigenetic codes have been sought for in the past decade48, but it turns out that they have already been in use in the clinic as anticancer therapeutics for more than 40 years without realization.

Methods

Cell culture and constructs

MelJuSo cells were maintained in IMDM with penicillin/streptomycin and 8% FCS. Histone variants were cloned into pEGFP vector (CloneTech) where EGFP was swapped for PAGFP49. Histone H2A, H2B and H2AX were tagged at the N-terminus while H3 and H4 were tagged at the C-terminus with PAGFP, based on the GFP-tagged vectors (kindly provided by Dr Elisabetta Citterio, Division of Molecular Genetics, The Netherlands Cancer Institute). MelJuSo cells stably expressing the modified histones were maintained under G418 selection. The TopoIIα-GFP construct was generously provided by Christensen et al.50. All constructs were sequencing verified.

Reagents

Doxorubicin and etoposide were obtained from Pharmachemie (Haarlem, The Netherlands). Daunorubicin was obtained from sanofi-aventis (The Netherlands). Idarubicin was obtained from Pfizer. Aclarubicin was obtained from Santa Cruz and dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide at 20 mg ml−1 concentrations, aliquoted and stored at −20 oC for further use. For in vivo mouse experiments, Etop was first diluted in saline buffer at a concentration of 7 mg ml−1.

Immunostaining

Cells were cultured on coverslips and treated with the drugs indicated for 2 h. Tissue culture cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol (−20 oC) before staining with γ-H2AX (1/200; Millipore), MDC1 (1/200; Abcam) primary antibodies followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies (1/200; Molecular Probes) for analyses by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica TCS SP2 AOBS). Mouse tissues were formalin-fixed and processed by the animal pathology department for haematoxylin and eosin, γ-H2AX (1/50; Cell Signaling) and Ki-67 (1/600; Monosan) staining.

Microscopy

Cells expressing TopoIIα-GFP or PAGFP-labeled histones were analysed by a Leica-AOBS system equipped with a climate chamber. Cells were kept in Phenol Red-free DMEM medium with penicillin/streptomycin and 8% FCS. Photoactivation was done with 405 nm laser light, and activated GFP-tagged histones were monitored within the spectrum range of 500–530 nm, in the presence or absence of respective drugs. For the quantification of activated-fluorescent histone release, MelJuSo cells stably expressing respective histone variants were cultured in eight-well chambered coverglass (NUNC). Point-activation of PAGFP-tagged histones was performed on multiple cells in the same culture. Cells under different treatments were followed by a confocal microscope system with a multi-position time-lapse module. Loss of fluorescence was quantified using MATLab software, where mobility of the cells can be followed in time. For other live cell imaging quantifications, the whole time series from the figures were quantified using MATLab software at the indicated regions. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments were performed using the module provided in Leica-AOBS system12,51. In order to exclude involvement of active processes in Doxo-induced histone eviction, MelJuSo/PAGFP-H2A cells grown on coverslips were first permeabilized with ice-cold 0.1% Triton X-100 (in PBS) at room temperature for 1 min, followed by extensive washing with PBS. Then cells were kept in PBS and mounted onto the tissue culture device of the AOBS-confocal microscope. Photoactivation and drug treatment were performed identically as for the live cell imaging but was now performed in PBS at 37 oC.

Western blotting

Cells were either lysed directly in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA), or fractionated by a nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Thermo). All buffers were supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Lysates were quantified and equal amounts of total proteins were analysed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for subsequent western blotting analysis. The following primary antibodies were used: γ-H2AX, H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H2A (1/1000; all from Millipore); phospho-p53, phospho-S*/T*Q (phospho-(Ser/Thr) ATM/ATR substrate), poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (1/1000; all from Cell Signaling); MRE11 (1/1000; Abcam); GFP12; Ran (1/1000; kindly provided by Dr Maarten Fornerod) and tubulin (1/2000; Sigma).

In vitro single nucleosomes assembly

EpiMark Nucleosome Assembly Kit was used to assemble single nucleosomes in vitro, according to the dilution assembly protocol from the manufacturer. Assembled single nucleosomes with or without treatments were analysed with gel shift assay.

Constant-field gel electrophoresis

DNA double-strand breaks were quantified by constant-field gel electrophoresis as described21. In short, MelJuSo cells were treated with Doxo, Etop or Acla at indicated doses for 2 h. Then drugs were removed by extensive washing. Cells were collected and processed immediately after drug removal to determine the DNA breaks generated during the drug treatment. Alternatively, cells were further cultured for another 8 h before DNA double-strand breaks were quantified. Images were analysed with ImageJ.

Animals

FVB nude or wild-type mice were used. Mice were injected intravenously with a single dose of 10 mg kg−1 (≈30 mg m−2) of Doxo or 35 mg kg−1 (≈105 mg m−2) of Etop. The pharmacokinetics (clearance, half-life and volume of distribution) of Doxo in mice52 and humans(DailyMed:ADRIAMYCIN. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=5594d16e-72bf-4354-925e-c7591737ff1c (2012).) display remarkable similarities, supporting the translation of our observations. 1 h, 4 h, 1 day or 6 days post drug administration, mice were killed and organs were collected. Part of the organs (lung, heart and liver) was fixed in formalin for pathology analyses (IHC). The remainder of the organs was prepared for microarray and FAIRE-seq analyses. All experimental procedures on animals were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of The Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Microarray data analysis

For microarray analysis, cells were lysed directly in TRIzol (Invitrogen) and 350 ng of extracted total RNA was amplified with the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). Amplified antisense RNA (1.5 μg) was hybridized to MouseWG-6 v2.0, HumanWG-6 v2.0 or v3.0 Expression BeadChips (Illumina) that were processed according to the protocol from Illumina and scanned with a BeadArray Reader (Illumina). MIAME compliant data are available via Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession code GSE33634.

For data acquired from cell lines, genes with at least twofold changes compared with the control cells were considered differentially expressed and selected for subsequent analysis. For the microarray data generated from drug-treated mouse organs, they were first normalized with variation stabilizing. Then significantly deregulated genes were calculated with a Limma package53, where linear models were applied. Differentially expressed genes were determined with the adjusted P-value cutoff <0.05.

FAIRE-seq and ChIP-seq

For FAIRE-seq and ChIP-seq of tissue culture cells, 1 × 108 cells were treated with 9 μM Doxo, 60 μM Etop or 20 μM Acla for 4 h, fixed and processed as described26,54. For ChIP-seq of 24 h post drug removal, 1 × 108 cells were exposed to the same concentrations of drugs for 2 h. Drugs were removed by washing with tissue culture medium before further culturing for 24 h. The cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde and processed as described54. Anti-H3K4me3 (10 μg per ChIP sample; Abcam ab1012) and anti-H3K27me3 (10 μg per ChIP sample; Millipore 07-449) antibodies were used for ChIP. For mouse organs, FVB nude or wild-type mice were injected with 10 mg kg−1 doxorubicin or 35 mg kg−1 Etop. Four hours post drug treatment, mice were killed and organs were collected. Organs were sliced into small tissue blocks before fixation in 1% formaldehyde for 20 min. Identical procedures were applied as for the cell line experiments. All DNA samples were processed and sequenced on Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx or HiSeq 2000 platforms, according to the provider’s kits and protocols for ChIP samples. All the sequencing data are available via GEO under accession code GSE33634.

AML patients

AML blasts were isolated from patients’ blood with a BD Vacutainer CPT Cell Preparation Tube according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mononuclear blast cells were washed once with cold PBS and counted, before directly culture in RPMI media with penicillin/streptomycin and 8% FCS; or fixed and processed according to the FAIRE-seq protocol used for cell lines. 1 × 108 blast cells before and 2 h post Daun administration were used for FAIRE experiments.

AML blast cells used for in vitro experiment were isolated from a 79-year-old male. He received 87 mg of Daun (45 mg m−2) per day for 3 consecutive days during induction. Patient achieved remission after induction therapy but expired from infectious complication of the lung.

AML blast cells used for FAIRE-seq experiments were isolated from a 34-year-old male. He received bolus injection of 90 mg of Daun (45 mg m−2) within 10 min during the first course of treatment, when blast cells were collected for FAIRE-seq experiment. AML blast cells were collected before treatment and 2 h after conclusion of Daun injection. Patient achieved complete remission after induction therapy. All patient samples used in this study were obtained with informed consent.

Next generation sequencing data analysis

For FAIRE-seq samples, the average coverage in 5 kb windows was determined and normalized to the total number of reads. Ratios were calculated by dividing the coverage of the drug-treated samples by the untreated samples. The ratios were log transformed and smoothed using a running median of 11 bins and plotted as transparent vertical bars. Peak regions were called by using F-seq package55. The same parameter was applied in the F-seq to call peak regions within the same cell lines or organs to compare the results of subsequent drug treatment. Distribution of peak regions was further analysed with cis-regulatory element annotation system (CEAS) (ref. 56). The enrichment of peak regions and the corresponding heatmaps around all RefSeq TSS or gene body was calculated with seqMINER57. Drug-induced unique FAIRE-seq peak regions were defined as follows: FAIRE-seq peak regions of control cells were subtracted from FAIRE-seq peak regions of different drug-treated cells. The non-overlapping pieces of intervals from the drug-treated samples were used as unique FAIRE-seq peak regions for further analysis. Then the drug-induced unique FAIRE-seq regions were used to intersect with the promoter and gene body regions of the differentially expressed genes to correlate the results from FAIRE-Seq with the expression arrays. This was done using Cistrome/Galaxy.

Author Contributions

B.P. and J.N. designed and conceived the experiments. B.P. performed the cell biology and biochemical experiments. X.Q. performed the FAIRE-Seq experiments and imaging quantification. L.J. made constructs. T.G. was instructive during initial experiments. B.P., X.Q. and W.Z. performed the ChIP-seq experiments. A.V. and B.P. with input from W.Z. performed bioinformatics analysis. R.K. and M.N. performed sample preparation for next generation sequencing. H.O. synthesized and supplied doxorubicin analogues. O.v.T. and S.R. performed the drug studies in mice. P.H and J.J. provided AML patient materials. B.P. and J.N. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Additional information

Accession code: All microarray data and next generation sequencing data in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE33634.

How to cite this article: Pang, B. et al. Drug-induced histone eviction from open chromatin contributes to the chemotherapeutic effects of doxorubicin. Nat. Commun. 4:1908 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2921 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S28, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Methods, and Supplementary References

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor etoposide. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to etoposide. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Histones remained in the photoactivated area in etoposide-treated cells.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor etoposide. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to etoposide. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Histones remained in the photoactivated area in etoposide-treated cells.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor doxorubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to doxorubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Doxorubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor aclarubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to aclarubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Aclarubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor daunorubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to daunorubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Daunorubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor idarubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to idarubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Idarubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Gene Ontology analysis of genes altered in MelJuSo and SW620 cells 1 or 6 days post drug exposure. The genes differentially expressed in MelJuSo or SW620 cells 24 hrs or 6 days after exposure to Doxo, Acla or Etop were analyzed for pathway enrichment. A two-fold difference by microarray was used as a cut-off to select genes differentially expressed. The pathways with a significance p<0.05 are listed, and their statistical significance and the genes enriched in the respective pathways are indicated. Ingenuity pathway analysis program was used to extract the pathways after the different drug treatments.

Summary of the statistics relating to the next generation sequencing samples.

Gene Ontology analysis of genes changed in hearts and livers of mice exposed to doxorubicin or etoposide treatment. The genes differentially expressed in mice 24 h or 6 days post-Doxo or Etop injection (as indicated) were analyzed for pathway enrichment. Differentially expressed genes were calculated with LIMMA package. The pathways with a significance p<0.05 are listed, and their statistical significance and the genes enriched in the respective pathways are indicated. Ingenuity pathway analysis program was used to extract the pathways after the different drug treatments.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Animal Pathology and NKI Mouse House Facility for helping with the mouse experiments, and the NKI Central Genomics Facility for microarray and deep sequencing. We thank Lauran Oomen and Lenny Brocks from the NKI Digital Microscopy Facility, Anita Pfauth and Frank van Diepen of the NKI Flow Cytometry Facility for the technical support. We thank Jiying Song for the pathology analysis of mouse tissues, Wendy Sol for mouse experiments, Conchita Vens for the CFGE experiment, Coen Kuijl for image analysis software, Elisabetta Citterio and Joep Vissers for various antibodies and vectors, Massimiliano Maletta for structure modelling, Jason S. Carroll and James Hadfield (Cancer Research UK, Cambridge) for help with the H3K4me3 ChIP-seq experiments, Theo Knijnenburg for statistics support and Xiaole Shirley Liu (Harvard) for suggestions. We thank Ilana Berlin, Fred van Leeuwen, Piet Borst, Anton Berns, Sjoerd Rodenhuis, Hein te Reile and Bas van Steensel for support, critical discussions and reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research NWO, Dutch Cancer Society KWF and an ERC Advanced Grant.

References

- Garnett M. J. et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature 483, 570–575 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer H. et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcamone F. et al. Adriamycin, 14-hydroxydaimomycin, a new antitumor antibiotic from S. Peucetius var. caesius. Biotechnol Bioeng. 11, 1101–1110 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hande K. R. Clinical applications of anticancer drugs targeted to topoisomerase II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1400, 173–184 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minotti G., Menna P., Salvatorelli E., Cairo G. & Gianni L. Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol. Rev. 56, 185–229 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcamone F.-M. Fifty years of chemical research at farmitalia. Chemistry 15, 7774–7791 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitiss J. L. Targeting DNA topoisomerase II in cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 338–350 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T. & Soutoglou E. The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 243–254 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni L. et al. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: from bench to bedside. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 3777–3784 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewey K., Rowe T., Yang L., Halligan B. & Liu L. Adriamycin-induced DNA damage mediated by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II. Science 226, 466–468 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. L. et al. Nonintercalative antitumor drugs interfere with the breakage-reunion reaction of mammalian DNA topoisomerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 13560–13566 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantuma N. P., Groothuis T. A. M., Salomons F. A. & Neefjes J. A dynamic ubiquitin equilibrium couples proteasomal activity to chromatin remodeling. J. Cell. Biol. 173, 19–26 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene R. F., Collins J. M., Jenkins J. F., Speyer J. L. & Myers C. E. Plasma pharmacokinetics of adriamycin and adriamycinol: implications for the design of in vitro experiments and treatment protocols. Cancer Res. 43, 3417–3421 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hande K. R. et al. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose etoposide (VP-16-213) administered to cancer patients. Cancer Res. 44, 379–382 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder P. et al. Pharmacokinetics of etoposide in cancer patients treated with high-dose etoposide and with dexrazoxane (ICRF-187) as a rescue agent. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 53, 91–93 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick C. A. et al. Structural comparison of anticancer drug-DNA complexes: adriamycin and daunomycin. Biochemistry 29, 2538–2549 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K., Mader A. W., Richmond R. K., Sargent D. F. & Richmond T. J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 389, 251–260 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeste A. et al. Genomic instability in mice lacking histone H2AX. Science 296, 922–927 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki M. et al. MDC1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 123, 1213–1226 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Zhong Q. & Chen P.-L. The Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein is essential for Mre11 phosphorylation upon DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19513–19516 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neijenhuis S. et al. Mechanism of cell killing after ionizing radiation by a dominant negative DNA polymerase beta. DNA Repair (Amst) 8, 336–346 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodek D., Banath J. & Olive P. L. Comparison between pulsed-field and constant-field gel electrophoresis for measurement of DNA double-strand breaks in irradiated Chinese hamster ovary cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 60, 779–790 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W. E. & Smith M. C. Repair of deoxyribonucleic acid lesions caused by adriamycin and ellipticine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 31, 1931–1935 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filion G. J. et al. Systematic protein location mapping reveals five principal chromatin types in drosophila cells. Cell 143, 212–224 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J. et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature 473, 43–49 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaulton K. J. et al. A map of open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. Nat. Genet. 42, 255–259 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado A., Holmes K. A., Ross-Innes C. S., Schmidt D. & Carroll J. S. FOXA1 is a key determinant of estrogen receptor function and endocrine response. Nat. Genet. 43, 27–33 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan K., Lincoff A. M. & Young J. B. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann. Intern. Med. 125, 47–58 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers E. E., Wilde A. A. & Pinto Y. M. Heart failure: advances through genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 357–362 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 18, 1639–1642 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewen M. E. Where the cell cycle and histones meet. Genes Dev. 14, 2265–2270 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry S. P. & Townsend P. A. in International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology Vol. 284, Jeon Kwang W. ed. 113–179Academic Press (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra J., Grobbee D. E., Remme W. J. & Stricker B. H. C. Drug-induced heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 33, 1152–1162 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J. M. et al. Long-term survival in acute myeloid leukemia: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Cancer 80, 2205–2209 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou E. P., Nieves-Neira W., Boon C., Pommier Y. & Bonner W. M. Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9390–9395 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieseler F. et al. Topoisomerase II activities in AML blasts and their correlation with cellular sensitivity to anthracyclines and epipodophyllotoxines. Leukemia 10, (Suppl 3): S46–S49 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. et al. Topoisomerase II levels and drug sensitivity in adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 83, 517–530 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks-Wagner D. & Hartwell L. H. Normal stoichiometry of histone dimer sets is necessary for high fidelity of mitotic chromosome transmission. Cell 44, 43–52 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morillo-Huesca M. et al. FACT prevents the accumulation of free histones evicted from transcribed chromatin and a subsequent cell cycle delay in G1. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000964 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen O. P. et al. Aclarubicin plus cytosine arabinoside versus daunorubicin plus cytosine arabinoside in previously untreated patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a Danish national phase III trial. The Danish Society of Hematology Study Group on AML, Denmark. Leukemia 5, 510–516 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. B. The anthracyclines: will we ever find a better doxorubicin? Semin. Oncol. 19, 670–686 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-C. et al. Structural basis of type II topoisomerase inhibition by the anticancer drug etoposide. Science 333, 459–462 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmore E., Frank A. J., Padget K., Tilby M. J. & Austin C. A. Etoposide targets topoisomerase IIα and IIβ in leukemic cells: isoform-specific cleavable complexes visualized and quantified in Situ by a novel immunofluorescence technique. Mol. Pharmacol. 54, 78–85 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai V. B. & Nahata M. C. Cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents: incidence, treatment and prevention. Drug Safety 22, 263–302 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang T. C. et al. Histone H3 lysine 9 di-methylation as an epigenetic signature of the interferon response. J. Exp. Med. 209, 661–669 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdoerffer P. An age of fewer histones. Nat. Cell. Biol. 12, 1029–1031 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Michael J. et al. Sequential application of anticancer drugs enhances cell death by rewiring apoptotic signaling networks. Cell 149, 780–794 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin S. B. & Jones P. A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome — biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 726–734 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G. H. & Lippincott-Schwartz J. A photoactivatable GFP for selective photolabeling of proteins and cells. Science 297, 1873–1877 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M. O. et al. Dynamics of human DNA topoisomerases IIα and IIβ in living cells. J. Cell. Biol. 157, 31–44 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reits E. A. J. & Neefjes J. J. From fixed to FRAP: measuring protein mobility and activity in living cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 3, 145–147 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asperen J. v., Tellingen O. v., Tijssen F., Schinkel A. H. & Beijnen J. H. Increased accumulation of doxorubicin and doxorubicinol in cardiac tissue of mice lacking mdr1a P-glycoprotein. Br. J. Cancer. 79, 108–113 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G. K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 1, 3 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D. et al. ChIP-seq: Using high-throughput sequencing to discover protein–DNA interactions. Methods 48, 240–248 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle A. P., Guinney J., Crawford G. E. & Furey T. S. F-Seq: a feature density estimator for high-throughput sequence tags. Bioinformatics 24, 2537–2538 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H., Liu T., Manrai A. K. & Liu X. S. CEAS: cis-regulatory element annotation system. Bioinformatics 25, 2605–2606 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye T. et al. seqMINER: an integrated ChIP-seq data interpretation platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S28, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Methods, and Supplementary References

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor etoposide. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to etoposide. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Histones remained in the photoactivated area in etoposide-treated cells.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor etoposide. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to etoposide. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Histones remained in the photoactivated area in etoposide-treated cells.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor doxorubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to doxorubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Doxorubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor aclarubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to aclarubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Aclarubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor daunorubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to daunorubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Daunorubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Histone dynamics in cells exposed to the TopoII inhibitor idarubicin. Part of the nucleus of MelJuSo cells stably expressing PAGFP-H2A was activated by 405 nm laser light followed by exposure to idarubicin. A time-lapse movie was generated and the corresponding time points are indicated in the different frames. Movies were generated by a Leica AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C climate chamber. A colour lookup table was applied to the various frames in the movie to better visualize the differences in fluorescence intensity. Idarubicin-treated cells showed histone eviction and redistribution of the fluorescent PAGFP-H2A outside the activated area in the nucleoplasm.

Gene Ontology analysis of genes altered in MelJuSo and SW620 cells 1 or 6 days post drug exposure. The genes differentially expressed in MelJuSo or SW620 cells 24 hrs or 6 days after exposure to Doxo, Acla or Etop were analyzed for pathway enrichment. A two-fold difference by microarray was used as a cut-off to select genes differentially expressed. The pathways with a significance p<0.05 are listed, and their statistical significance and the genes enriched in the respective pathways are indicated. Ingenuity pathway analysis program was used to extract the pathways after the different drug treatments.

Summary of the statistics relating to the next generation sequencing samples.

Gene Ontology analysis of genes changed in hearts and livers of mice exposed to doxorubicin or etoposide treatment. The genes differentially expressed in mice 24 h or 6 days post-Doxo or Etop injection (as indicated) were analyzed for pathway enrichment. Differentially expressed genes were calculated with LIMMA package. The pathways with a significance p<0.05 are listed, and their statistical significance and the genes enriched in the respective pathways are indicated. Ingenuity pathway analysis program was used to extract the pathways after the different drug treatments.