Abstract

Background:

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released revised pregnancy weight gain guidelines. There are limited data regarding the effect of maternal weight gain on newborn adiposity.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to estimate neonatal fat mass, lean body mass, and percentage body fat according to current Institute of Medicine (IOM) pregnancy weight gain guidelines.

Design:

This is a secondary analysis of a prospective observational cohort study of neonates delivered at least 36 wk gestation and evaluated for fat mass, lean body mass, and percentage body fat. Women with abnormal glucose tolerance testing and other known medical disorders or pregnancies with known fetal anomalies were excluded. Pregravid body mass index (BMI) was categorized as normal weight (<25 kg/m2), overweight (25–30 kg/m2), or obese (>30 kg/m2). Maternal weight gain was quantified as less than, equal to, or greater than current IOM guidelines. Newborn body composition measurements were compared according to weight gain and BMI categories.

Results:

A total of 439 maternal-newborn pairs were evaluated; 19.8% (n = 87) of women gained less than IOM guidelines; 31.9% (n = 140), equal to IOM guidelines; and 48.3% (n = 212), greater than IOM guidelines. Significant differences for each component of body composition were found when evaluated by IOM weight gain categories (all ANOVA, P < 0.001). When controlling for pregravid BMI, only weight gain for women who were of normal weight before pregnancy remained significant.

Conclusion:

Maternal weight gain during pregnancy is a significant contributor to newborn body composition, particularly for women who are of normal weight before pregnancy.

In 1990, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) first published guidelines for maternal weight gain according to pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) (1). These recommendations were developed in part regarding concerns about the role of maternal weight gain and low birth weight infants. In 2009, the IOM released revised pregnancy weight gain guidelines that continued to focus on the consequences of maternal weight gain and effect on newborn birth weight. The committee also considered the impact of gestational weight gain on short- and long-term maternal and child heath outcomes as a consequence of the obesity epidemic (2).

Birth weight has been a major outcome of interest to estimate abnormal growth. With the rise in childhood obesity (3, 4) and its potential consequences for childhood and long-term adult health (5–7), it is imperative to understand the contribution of the intrauterine environment to both low and high birth weight newborns and potentially later childhood and adult disease (8, 9). To date, several authors have demonstrated a relationship between abnormal intrauterine growth and childhood obesity, metabolic abnormalities, and adverse short- and long-term outcomes (10–12).

However, birth weight is a relatively nonspecific measure of newborn growth (13, 14). Newborn body composition, comprised of estimations of lean and fat mass, offers an estimate of newborn adiposity that might be a more specific biomarker for long-term metabolic dysfunction. Abnormal maternal weight gain (both excessive and inadequate) has been correlated with aberrant fetal growth as estimated by birth weight (15). High maternal weight before pregnancy has also been associated with increased newborn fat mass (FM) and percentage body fat (%BF) (16). However, the contribution of maternal gestational weight gain to newborn adiposity is less well studied. In its revised guidelines, the IOM highlighted the dearth of information about the relationship between newborn body composition and maternal weight gain. Thus, it is unclear what impact maternal weight gain according to the recent IOM recommendations has on fetal growth, particularly fetal adiposity.

Therefore, the specific aim of the current investigation was to estimate neonatal body composition according to the revised IOM pregnancy weight gain guidelines when controlling for pre-pregnancy BMI. We hypothesize that: 1) encouraging increased weight gain in normal-weight women will increase birth weight at the expense of increased adiposity relative to lean body mass (LBM); and 2) weight gain will have limited effect on accrual of adipose tissue in newborns of obese women.

Subjects and Methods

This is a secondary analysis of a prospective observational cohort study examining the impact of maternal factors upon fetal growth. All women who participated in the study received care at MetroHealth Medical Center, an urban tertiary care institution affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. This study was approved by the hospital institutional review board, and signed informed consent was obtained for all subjects. The primary outcome was newborn body composition, including FM and LBM as estimated by anthropomorphic measurements. Newborn anthropomorphic measurements were obtained by select trained personnel in the Clinical Research Unit of the Clinical and Translational Science Award using Harpenden calipers (British Indicators, Sussex, UK) to determine skinfold measurements, a calibrated scale for birth weight, and a neonatal measuring board for birth length. All newborn measurements were obtained within a mean of 1.2 d of life (±0.9 d). Several repetitive skinfolds and body circumference measurements were taken to ensure accuracy. All measurements were taken on the left side. Skinfold measurements, specifically the flank skinfold, were used in a calculation to determine FM. This method has been previously validated by comparison with total body electrical conductivity with a correlation coefficient R2 = 0.84. The interobserver coefficient of variation of a skinfold measurement is approximately 6% (or 8.4 g in the FM calculation) as previously reported (17). Newborn FM was determined from skinfold measurements, with LBM and %BF calculated as follows: LBM = BW − FM; %BF = FM/BW.

Women were approached for participation in the parent study (1990–2009) if they were healthy with a singleton gestation. For our secondary analysis, only women who delivered at 36 wk or greater estimated gestational age with a normal 1-h glucose screen (defined as a venous plasma glucose level <135 mg/dl 60 min after a 50-g oral glucose load) were included. Pregnancies complicated by medical disorders including hypertension, preeclampsia, and renal disease or those with a known fetal anomaly were excluded. Additionally, pregnancies complicated by preexisting diabetes or gestational diabetes were also excluded. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was determined from individual chart review. Pre-pregnancy weight was defined as a weight in the maternal medical record ± 12 wk from a last menstrual period. In the absence of a documented pre-pregnancy weight, the maternal self-reported pre-pregnancy weight was used. Approximately 25% of the pre-pregnancy maternal weight data were determined only from self-reported information. There was no difference in the use of self-reported pre-pregnancy weight by maternal BMI categories (P = 0.16). Delivery weight was defined as the last documented maternal weight within 14 d of delivery. Gestational weight gain was calculated as the difference of delivery weight and pre-pregnancy weight.

Using the IOM weight gain guidelines (1), maternal subjects were grouped into one of three mutually exclusive categories: those that gained less than the IOM recommendations (<IOM), those that gained equal to IOM recommendations (=IOM), and those that gained greater than IOM recommendations (>IOM). Additionally, maternal subjects were classified according to their pregravid BMI into those that were underweight and normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2: which we refer to as “normal”), overweight (BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2), or obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) before pregnancy.

Newborn body composition measurements were analyzed by maternal BMI and weight gain categories. ANOVA, Fisher protected least significant difference (PLSD), χ2, linear regression, and logistic regression were used where appropriate. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. Stepwise regression was used to estimate the contribution of weight gain, gestational age, race, maternal tobacco use, and newborn gender to each newborn body composition component. All statistical analyses were performed using StatView 5.01 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Because this was a secondary analysis, a power calculation was not performed before the study. However, based on previous reports (16, 18), a power calculation was performed using a neonatal mean lean body weight of 3000 g with a sd value of 400 g, a total of 160 women would be needed to detect a 200-g or 7% difference in LBM, with an α of 0.05 and a power of 80%.

Results

A total of 439 mother-infant pairs were included in the analysis. Table 1 presents the maternal and neonatal characteristics for the cohort according to the IOM weight gain categories. Overall, 44% (n = 193) of maternal subjects were either underweight or of normal weight before pregnancy, with 22.3% (n = 98) of women categorized as overweight and 33.7% (n = 148) as obese. We found no differences in gestational age at delivery or newborn gender by the IOM weight gain categories. Consistent with previous investigations, maternal weight gain was associated with differences in newborn birth weight, with women in the >IOM weight gain group having the heaviest newborns. Additionally, we observed differences in maternal age, race, and pre-pregnancy BMI by weight gain categories. These maternal factors are well-known variables that contribute to differences in pregnancy weight gain (1).

Table 1.

Maternal and pregnancy characteristics by weight gain categories

| Variable | <IOM | =IOM | >IOM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 87 | 140 | 212 | |

| Maternal age (yr) | 26.6 (6.4) | 29.2 (6.0) | 27.7 (5.5) | 0.005 |

| Race | 0.0006 | |||

| African-American | 38.2 | 20.5 | 22.3 | |

| Caucasian | 51.7 | 74.7 | 63.6 | |

| Other | 10.1 | 4.8 | 14.1 | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 29.5 (10.6) | 26.6 (7.6) | 28.8 (7.4) | 0.02 |

| Weight gain (pounds) | 11.3 (11.2) | 24.9 (7.1) | 39.4 (12.7) | <0.0001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3166 (428) | 3271 (489) | 3416 (523) | 0.0002 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 39.0 (0.8) | 38.9 (1.1) | 39.0 (1.0) | 0.47 |

| Male gender | 57.3 | 51.4 | 54.4 | 0.81 |

Data are expressed as mean (sd) or percentage unless otherwise specified.

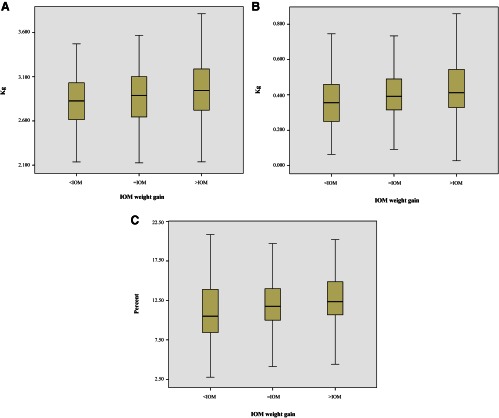

The primary outcome data for LBM, FM, and %BF by IOM weight gain categories are presented (Fig. 1, A–C). ANOVA demonstrated significant differences for each component of newborn body composition by IOM weight gain categories. For all subjects, subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the relationship between weight gain categories and newborn measurements (PLSD). For all newborn body composition measurements, significant differences were noted when comparing women with either =IOM or <IOM weight gain to those with >IOM weight gain. No differences were observed in any subgroup analysis comparing the <IOM group with the =IOM group. As expected, we observed the largest percentage increase for each body composition measurement when comparing those with <IOM weight gain to those with >IOM weight gain. The largest percentage increase was noted for newborn FM (24.2%), followed by %BF (15.6%), and then LBM (5.8%).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of neonatal anthropometric measurements according to the IOM weight gain recommendations. A–C, The primary outcome data for LBM, FM, and %BF by IOM weight gain categories. ANOVA demonstrated significant differences for each component of newborn body composition by IOM weight gain categories. For all subjects, subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the relationship between weight gain categories and newborn measurements (PLSD). Dark bars represent the median value. A, Neonatal LBM according to maternal weight gain categories. ANOVA, P = 0.0004. Subgroup comparisons (PLSD): <IOM vs. =IOM, P = 0.15; =IOM vs. >IOM, P = 0.01; <IOM vs. >IOM, P = 0.0002. B, Neonatal FM according to maternal weight gain categories. ANOVA, P = 0.0002. Subgroup comparisons (PLSD): <IOM vs. =IOM, P = 0.11; =IOM vs. >IOM, P = 0.01; <IOM vs. >IOM, P < 0.0001. C, Neonatal %BF according to maternal weight gain categories. ANOVA, P = 0.0006. Subgroup comparisons (PLSD): <IOM vs. =IOM, P = 0.07; =IOM vs. >IOM, P = 0.03; <IOM vs. >IOM, P = 0.0002.

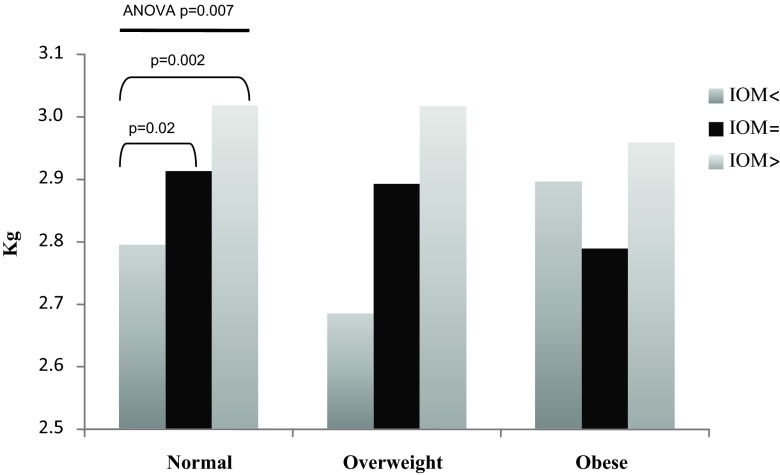

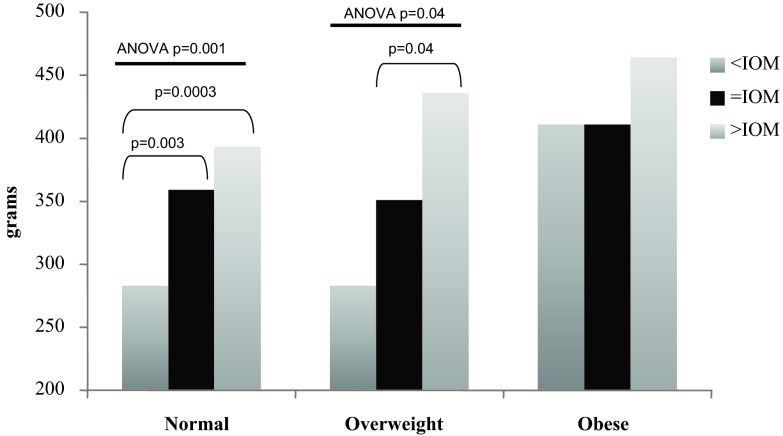

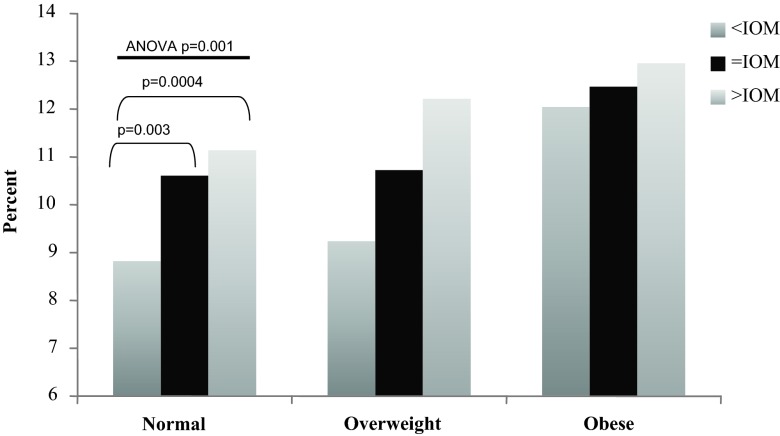

Because pregravid BMI is a significant factor relating to maternal weight gain and newborn birth weight and body composition, we evaluated the contribution of maternal weight gain to newborn body composition, adjusting for pre-pregnancy BMI. To accomplish this, each pregravid BMI group was evaluated independently to estimate newborn body composition data by IOM weight gain categories. These results are presented in Figs. 2–4.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of neonatal LBM by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and weight gain groups. In women who were normal BMI before pregnancy, ANOVA identified significant differences in newborn LBM (P = 0.007) by IOM weight gain groups. Subgroup analysis (PLSD) identified significant differences when comparing normal-weight women with <IOM vs. =IOM weight gain (P = 0.02) and when comparing normal-weight women with <IOM vs. >IOM weight gain (P = 0.002).

Fig. 3.

Estimation of neonatal FM by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and weight gain groups. In women of normal BMI before pregnancy, ANOVA identified significant differences in newborn FM (P = 0.001) by IOM weight gain groups. Subgroup analysis (PLSD) identified significant differences when comparing normal-weight women with <IOM vs. =IOM weight gain (P = 0.003) and when comparing normal-weight women with <IOM vs. >IOM weight gain (P = 0.0003). In women who were overweight before pregnancy, ANOVA identified significant differences in newborn FM (P = 0.04) by IOM weight gain groups. Subgroup analysis (PLSD) identified significant differences when comparing overweight women with =IOM vs. >IOM weight gain (P = 0.04).

Fig. 4.

Estimation of neonatal %BF by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and weight gain groups. In women who were normal BMI before pregnancy, ANOVA identified significant differences in newborn %BF (P = 0.001) by IOM weight gain groups. Subgroup analysis (PLSD) identified significant differences when comparing normal-weight women with <IOM vs. =IOM weight gain (P = 0.003) and when comparing normal-weight women with <IOM vs. >IOM weight gain (P = 0.0004).

In women who were normal BMI before pregnancy, ANOVA identified significant differences in LBM (P = 0.007), FM (P = 0.001), and %BF (P = 0.001) by weight gain categories. In reference to LBM, subgroup analysis in normal-weight women identified significant differences among the <IOM, =IOM, and >IOM, but not among the overweight or obese subjects (Fig. 2). In reference to FM, there were significant differences among the <IOM, =IOM, and >IOM in the normal-weight women and between the =IOM and >IOM in overweight women, but not among the obese women (Fig. 3). Lastly, in reference to %BF, there were significant differences among the <IOM, =IOM, and >IOM in normal BMI women, but not among the overweight or obese women (Fig. 4). Interestingly, there were no significant differences in any body composition measures by IOM weight gain categories for obese women.

Because many factors contribute to fetal growth, we estimated the relative contribution of select maternal and neonatal variables on each newborn body composition component using stepwise regression. For this analysis, we included the following variables: gestational weight gain, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking (yes/no), male gender, maternal age, maternal race, and estimated gestational age at delivery. Our results are presented in Table 2. In this analysis, pregravid BMI was noted to be the largest contributor to both newborn %BF and total FM. Maternal weight gain and gestational age at delivery contributed approximately one half of the variance in %BF as compared with maternal pregravid BMI.

Table 2.

Stepwise regression of factors that are associated with newborn body composition

| Variable | Cumulative R2 | ΔR2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LBM | |||

| Gestational age | 0.106 | <0.0001 | |

| Gender (male) | 0.157 | 0.051 | <0.0001 |

| Race (AA) | 0.198 | 0.041 | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | 0.239 | 0.041 | <0.0001 |

| Pregravid BMI | 0.253 | 0.014 | <0.0001 |

| Weight gain | 0.261 | 0.008 | <0.0001 |

| FM | |||

| Pregravid BMI | 0.051 | <0.0001 | |

| Weight gain | 0.100 | 0.049 | <0.0001 |

| Gestational age | 0.148 | 0.048 | <0.0001 |

| Maternal age | 0.155 | 0.007 | <0.0001 |

| %BF | |||

| Pregravid BMI | 0.063 | <0.0001 | |

| Gestational age | 0.102 | 0.039 | <0.0001 |

| Weight gain | 0.134 | 0.032 | <0.0001 |

For the above analysis, the total R2 value for all variables is reported as the “cumulative R2”. The individual R2 value for any specific variable can be found under the column “ΔR2”. AA, African-American.

Discussion

In this analysis of newborn body composition according to the revised 2009 IOM weight gain guidelines for pregnancy, we found a significant association between maternal weight gain and newborn FM, LBM, and %BF. The largest difference for all body composition components was noted when comparing women with less than recommended IOM weight gain to those with excessive weight gain. Gestational weight gain had the largest impact on newborn FM, with %BF and LBM demonstrating a proportionally smaller increase with increasing weight gain: 24.2, 15.6, and 5.8%, respectively.

However, to further understand the association between weight gain and adiposity, we evaluated the impact of weight gain on outcomes among women of various BMI categories. When controlling for pre-pregnancy BMI, a significant relationship between weight gain and newborn body composition was found primarily in women who were normal weight before pregnancy. There was a limited effect of gestational weight gain on FM in overweight women, and maternal weight gain had no effect on newborn body composition measurements for obese women.

The implications of these findings are important. We have known for a number of years that gestational weight gain has the greatest effect on birth weight in underweight and normal-weight women and the least effect in obese women (19). Our results expand on those seminal findings. For example, when comparing women with <IOM weight gain to those with >IOM weight gain for the entire cohort, a total mean increase in neonatal birth weight of 250 g was found. Eighty-seven grams of this additional neonatal weight gain was secondary to increased FM. However, when examining the effect of gestational weight gain based on pregravid BMI, a very different picture emerges.

For normal-weight women, a total neonatal mean weight increase of 314 g was noted with <IOM compared with >IOM gestational weight gain; approximately 33% or 104 g was composed of increased FM. For obese women, a difference of only 116 g of mean neonatal weight gain was noted between those with <IOM vs. >IOM weight gain, and only 53 g of this observed weight increase was from FM. Therefore increasing gestational weight gain from <IOM to >IOM in normal-weight women resulted in twice the increase of FM compared with obese women. These findings illustrate the significant contribution of FM to any incremental neonatal weight gain associated with increasing gestational weight. These data are consistent with our previous studies reporting that although neonatal FM accounts for approximately 10–12% of birth weight, it accounts for almost 50% of the variance in birth weight (20).

What are the potential underlying physiological changes occurring during pregnancy that might account for the observed changes in fetal growth? We know from long-term studies in Pima Indians that weight gain was inversely proportional to the change in insulin sensitivity (21). Because obese women enter pregnancy very insulin resistant, the decreases in insulin sensitivity are quantitatively smaller, and there is proportionally less gestational weight gain compared with normal-weight women (15). As a consequence, the fetus is already at risk, earlier in gestation, to receive excessive nutrient flux across the placenta due to the severe and early insulin resistance in obese women. In contrast, normal-weight women, because of increased pregravid insulin sensitivity, have greater gestational weight gain to achieve the necessary decreases in insulin resistance compared with obese women. Therefore, gestational weight gain >IOM in normal-weight women could result in further decreases in insulin sensitivity. As a consequence, this would provide excess nutrient availability to the fetus with subsequent increasing adiposity. Therefore, it is of concern that the goal of achieving a “normal” birth weight for all neonates (i.e. between the 10th and 90th percentiles), whether mothers be normal, overweight, or obese, may result in similar overall birth weights but vastly different degrees of adiposity. Additional research is necessary to further explore the short- and long-term effects of gestational weight gain in these populations.

Our study has several limitations. First, pre-pregnancy weight was determined from either chart abstraction (when possible) or from a patient's self-reported pre-pregnancy weight. Although self-reported weights are often used for research purposes, there are significant limitations to this information. However, only 25% of our cohort had a pre-pregnancy weight based solely on self-reported data, with no significant difference in the use of self-reported pre-pregnancy weight by BMI categories. Additionally, our cohort was assembled over a long period of time, which could lead to differences in outcomes due to either changes in practice patterns or a shift in our population. Nevertheless, routine obstetrical care has not changed appreciably over our study period, and we have no reason to believe that weight gain in 1990 would have a differential effect than weight gain in 2009. Additionally, the IOM gestation weight gain criteria did not become available until late 2009, so these recommendations were unlikely to affect the gestational weight gain patterns over time since 1990.

We conclude that increasing maternal weight gain during pregnancy significantly affects newborn FM, LBM, and %BF. Increasing gestational weight gain disproportionately increased newborn FM relative to the observed increases in newborn LBM or %BF. For normal BMI women, gestational weight gain had significant effects on newborn adiposity. Gestational weight gain was not a significant contributor to newborn adiposity for overweight or obese women. Therefore, the goals of appropriate gestational weight gain may need to be individualized, not only based on maternal factors, but also taking into consideration the short- and long-term fetal outcomes. The benefits of recommending increased gestational weight gain to decrease the frequency of growth restriction, particularly in normal-weight women, may be at the expense of increased newborn FM.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant HD-22965 and Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland Grant UL1 RR024989 from the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences component of the NIH, and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

T.P.W. participated in conception of the study design and contributed to critical aspects of the conduct of this research, including patient recruitment, monitoring of study progress, data quality evaluation, and analysis. T.P.W. provided significant intellectual contribution to the drafting and revision of this manuscript with regard to scientific content and form and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

L.H.-P. participated in conception of the study design and contributed to critical aspects of the conduct of this research, including patient recruitment, monitoring of study progress, data quality evaluation, and analysis. L.H.-P. provided significant intellectual contribution to the drafting and revision of this manuscript with regard to scientific content and form and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

P.M.C. participated in conception of the study design and contributed to critical aspects of the conduct of this research, including patient recruitment, monitoring of study progress, data quality evaluation, and analysis. P.M.C. provided significant intellectual contribution to the drafting and revision of this manuscript with regard to scientific content and form and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Each of the listed authors has made substantive contributions to this investigation including the study design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. Each of the authors has approved this submitted version of the manuscript.

These data were presented in abstract form at the 2010 annual clinical meeting of the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

Disclosure Summary: All of the authors state that they have no financial interests that would be viewed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- %BF

- Percentage body fat

- BMI

- body mass index

- FM

- fat mass

- IOM

- Institute of Medicine

- =IOM

- <IOM, >IOM, equal to, less than, and greater than IOM recommendations, respectively

- LBM

- lean body mass

- PLSD

- protected least significant difference.

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine (Subcommittees on Nutritional Status and Weight Gain during Pregnancy and Dietary Intake and Nutrient Supplements during Pregnancy, Committee on Nutritional Status during Pregnancy, and Lactation, Food and Nutrition Board) 1990. Nutrition during pregnancy. Part I, Weight gain. Part II, Nutrient supplements. Washington, DC: National Academy Press [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL. 2009. Institute of Medicine (Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines, Food and Nutrition Board, and Board on Children, Youth, and Families). Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. 2006. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA 295:1549–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dietz WH. 2004. Overweight in childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med 350:855–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. 2004. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev 5(Suppl 1):4–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P, Kleijnen J, Roberts H, Law C. 2005. Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 331:929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. 1997. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med 337:869–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barker DJ, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson JS. 1993. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 341:938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. 1993. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipdaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia 36:62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beltrand J, Nicolescu R, Kaguelidou F, Verkauskiene R, Sibony O, Chevenne D, Claris O, Lévy-Marchal C. 2009. Catch-up growth following fetal growth restriction promotes rapid restoration of fat mass but without metabolic consequences at one year of age. PLoS ONE 4:e5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Labayen I, Ruiz JR, Vicente-Rodríguez G, Turck D, Rodríguez G, Meirhaeghe A, Molnár D, Sjöström M, Castillo MJ, Gottrand F, Moreno LA. 2009. Early life programming of abdominal adiposity in adolescents: the HELENA Study. Diabetes Care 32:2120–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Catalano PM, Farrell K, Thomas A, Huston-Presley L, Mencin P, de Mouzon SH, Amini SB. 2009. Perinatal risk factors for childhood obesity and metabolic dysregulation. Am J Clin Nutr 90:1303–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller AT, Jr, Blyth CS. 1953. Lean body mass as a reference standard. J Appl Physiol 5:311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bernstein IM, Goran MI, Amini SB, Catalano PM. 1997. Differential growth of fetal tissues during the second half of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 176:28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nohr EA, Vaeth M, Baker JL, Sørensen TIa, Olsen J, Rasmussen KM. 2008. Combined associations of pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with the outcome of pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr 87:1750–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sewell MF, Huston-Presley L, Super DM, Catalano P. 2006. Increased neonatal fat mass, not lean body mass, is associated with maternal obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195:1100–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Catalano PM, Thomas AJ, Avallone DA, Amini SB. 1995. Anthropometric estimation of neonatal body composition. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173:1176–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Catalano PM, Thomas A, Huston-Presley L, Amini SB. 2003. Increased fetal adiposity: a very sensitive marker for abnormal in utero development. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:1698–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abrams BF, Laros RK., Jr 1986. Pre-pregnancy weight, weight gain, and birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol 154:503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Catalano PM, Tyzbir ED, Allen SR, McBean JH, McAuliffe TL. 1992. Evaluation of fetal growth by estimation of neonatal body composition. Obstet Gynecol 79:46–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Swinburn BA, Nyomba BL, Saad MF, Zurlo F, Raz I, Knowler WC, Lillioja S, Bogardus C, Ravussin E. 1991. Insulin resistance associated with lower rates of weight gain in Pima Indians. J Clin Invest 88:168–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]