Abstract

Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) plays a critical role in innate and acquired immunity, but its role in radio-resistance is unknown. We used TLR4 knockout (KO,−/−) mice and gut commensal depletion methods, to test the influence of TLR4 and its' in vivo agonist on basal radio-resistance. We found that mice deficient in TLR4 were more susceptible to IR-induced mortality and morbidity. Mortality of TLR4-deficient mice after IR was associated with a severe and persistent bone marrow cell loss. Injection of lipopolysaccharide into normal mice, which is known to activate TLR4 in vivo, induced radio-resistance. Moreover, TLR4 in vivo ligands are required for basal radio-resistance. We found that exposure to radiation leads to significant endotoxemia that also confers endogenous protection from irradiation. The circulating endotoxins appear to originate from the gut, as sterilization of the gut with antibiotics lead to increased mortality from radiation. Further data indicated that Myd88, but not TRIF, may be the critical adaptor in TLR4-induced radio-resistance. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that TLR4 plays a critical role in basal radio-resistance. Our data suggest, it is important not to give antibiotics that may sterilize the gut before the whole body irradiation. Further, these data also suggest that management of gut flora through antibiotic or possibly probiotic therapy may alter the innate response to the total body irradiation.

Keywords: ionizing radiation, toll-like receptor 4, lipopolysaccharide, commensal microflora, Myd88

Radiotherapy is commonly used as a component of clinical therapy for a wide range of cancer patients.1, 2, 3 It is estimated that about 20–50% of all the patients suffering head and neck cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, endometrial cancer and many other types of cancers will receive radiotherapy during the course of their treatment.3 However, exposure of high-dose ionizing radiation (IR) is associated with induction of acute radiation syndromes involving the hematopoietic system (HP) and gastrointestinal tract, especially the bone marrow cells (BMC) failure in the HP.4, 5 The extreme sensitivity of BMC to genotoxic stress largely determines not only the survival of the body, but also the adverse side effects of anti-cancer radiation therapy.4 Improvements have been realized in the understanding of the mechanism of radiation injuries and in the development of radioprotectants for medical and biodefense applications,4, 5, 6, 7 but knowledge in this area is still very limited. Specifically, the mechanism of many important molecules in radioprotection and basal radio-resistance remains unclear.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are the main sentinels of many types of immune cells and they play critical roles in innate and acquired immunity.8 It has been found that there are 13 types of TLRs in humans and mice.9, 10 Studies showed that TLRs, especially TLR4, have critical roles in host defense against infection by detecting conserved components of invading microbial pathogens.11 However, there are only limited studies examining the role of TLRs, especially TLR4, in radiobiology. In a related study in 2008, Burdelya et al. 4 found that a TLR5 agonist CBLB502 has radio-protective activity in mouse and monkey models by activation of NF-κB. Other studies also showed that the TLR5 ligand CBLB502 serves as a possible link between radio-resistance and epithelium's innate immune response.12, 13 These data indicate some TLRs, especially TLR5, may have a critical role in normal tissue radiation biology, but the detailed mechanism of other TLRs in this area remains not well understood.14 As TLR4 and TLR5 are in the same TLR family and they have many similarities in their signaling pathway,10, 15 TLR4 may also play a similar role to TLR5 in radioprotection. Further, compared to TLR5, where its expression pattern is limited to some tissues and organs,16 TLR4 molecular expression is very broad and the function of TLR4 has been much more studied than TLR5.9, 17 However, the potential role of TLR4 in radio-protection and its role in basal radio-resistance remained poorly known. In addition, the importance of TLR4 signaling in radiation responses has yet to be fully explored.

In the study reported here, we used TLR4 knockout (KO,−/−) mice and gut commensal depletion methods, to test the influence of TLR4 and its' in vivo agonist on basal radio-resistance. We additionally tested TLR4 in vitro agonists, like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), for a TLR4 dependent radio-protective role. Finally, we report the possible mechanisms of action for these radio-resistance effects.

Results

Mice deficient in TLR4 were more susceptible to radiation-induced mortality

To study the role of TLR4 in radiation injury, we first studied the basic nature of TLR4−/− mice used in this study. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, TLR4−/− mice show no developmental abnormalities and they are fertile.

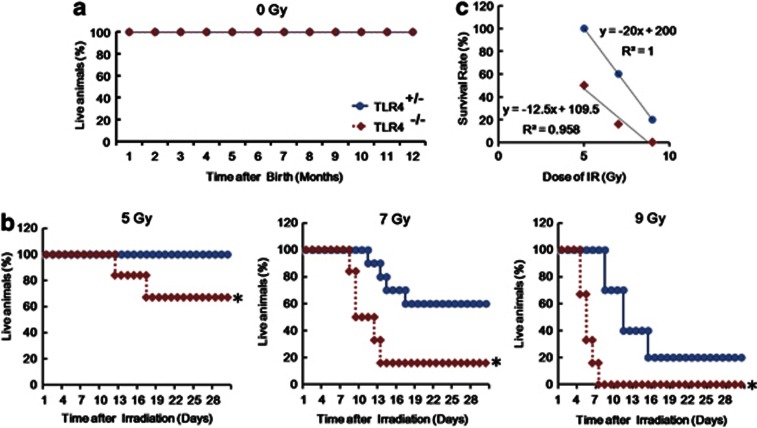

We next studied the radio-sensitivity difference between different mouse genotypes. We exposed age- and sex-matched TLR4−/− mice and TLR4+/− mice to 0, 5, 7 and 9 Gy of γ-radiation. However, as TLR4−/− mice showed normal survival ability without radiation and can survive over a year under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions (Figure 1a), these animals showed severe mortality and morbidity after γ-irradiation (Figure 1b). Although TLR4+/− mice had 100% survival rate at the dose of 5 Gy, but TLR4−/− mice only had a survival rate of 60% (P<0.05). Consistent with the observed differences after 5 Gy, TLR4−/− mice also showed more mortality than TLR4+/− mice after 7 or 9 Gy (Figure 1b). Regression analysis of the radiation survival data produced LD50/LD30 values of 7.5 Gy for the TLR4+/− mice, and 5.7 Gy for the TLR4−/− mice. The calculated dose-reduction factor (DRF) was 1.32 (TLR4+/− mice versus TLR4−/− mice) (Figure 1c). Consistent with the observed differences in survival, TLR4−/− mice showed much more severe morbidity and weight loss with the TLR4+/− controls (Supplementary Figures S2A and S2B). In addition, throughout the duration of the experiment, 5 Gy exposed TLR4−/− animals were observed to be moribund, with a paralyzed posture and defective drinking and eating desire as opposed to 5 Gy exposed TLR4+/− mice, which remained active, mobile and seemingly healthy (Supplementary Figure S2C). To further support a role for TLR4 in radio-protection in vivo, we also performed a TLR4 in vivo knockdown (KD) assay in C57BL/10 mice. We found that mice injected with the TLR4 specific in vivo KD reagents displayed severe motility after 7 Gy compared to mice injected with the non-specific control in vivo KD reagents (Supplementary Figures S3A and S3B). These data, taken together, indicated that mice deficient in TLR4 were more susceptible to radiation-induced mortality and morbidity.

Figure 1.

Increased mortality in TLR4−/− mice exposed to IR. (a) Survival to day 360 of TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice without IR in SPF conditions (N=6). (b) TLR4+/− control (N=30) and TLR4−/− (N=18) mice ((TLR4+/− control (N=10) and TLR4−/− (N=6) in each group)) were each randomly divided into three groups and exposed to 5, 7 or 9 Gy 60Co-γ radiation (dose rate: 1 Gy/min). Survival was monitored until day 30 after IR. (c) Linear regression analysis of the survival rate for TLR4−/− mice and TLR4+/− control mice after IR. The equation and the correlation coefficient for the line are given. The calculated DRF using these equations was 1.5 (TLR4+/− mice versus TLR4−/− mice). Blue circles: TLR4+/− mice and red squares: TLR4−/− mice; *P<0.05.

Mortality of TLR4−/− mice after IR was associated with a severe and persistent BMC loss

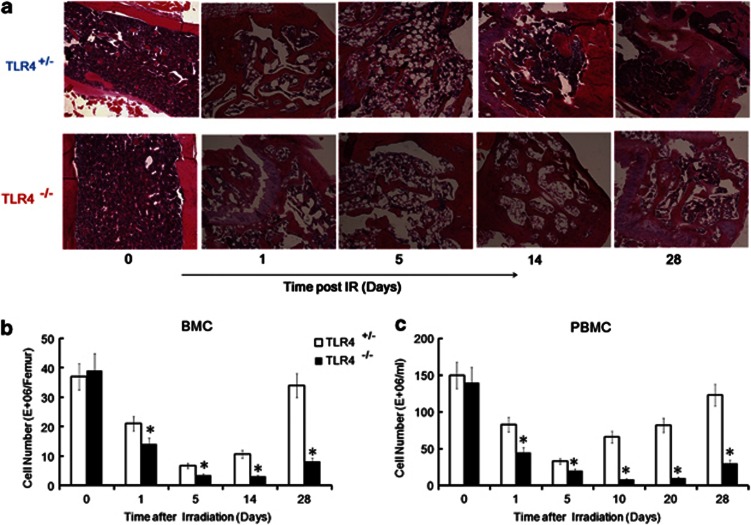

To further analyze the reason for increased mortality of TLR4−/− mice after IR, mass biopsy assays were performed for a histological study of the radiation-induced tissue damage in TLR4+/− and TLR4−/− mice. A 5 Gy total body irradiation (TBI) was shown to induce tissue damage in multiple organs of both TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice, but TLR4−/− mice showed greater injury in bone marrow (BM), colon, kidney, spleen, testis and lung as detected by hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) assays (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure S4). The histological study results also indicated that the main cause of death in TLR4−/− mice may be severe and persistent BMC loss. As shown in Figure 2a, 5 Gy exposure injured BM and decreased the BMC number from TLR4+/− mice. However, the BM showed the greatest damage and cell loss at day 5 post-IR and all mice demonstrated significant BM tissue repair at day 14 post-IR, while by day 28, BM from TLR4+/− mice was well repaired. However, in the TLR4−/− mice, BMC loss were more severe and more persistent. The TLR4−/− BMCs showed only slightly greater damage than TLR4+/− BMCs at day 1 and day 5, but the greatest damage and cell loss occurred at day 14, and was much more severe than day 14 in TLR4+/− BM (P<0.05). The TLR4−/− mice that survived demonstrated only partial BM tissue repair at day 28 post-IR. These data are consistent with the death of nearly half the TLR4−/− mice 9–17 days after 5 Gy (Figure 1b). The BMC and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) numbers in TLR4+/− and TLR4−/− mice were also counted on different days after 5 Gy exposure. The PBMC numbers of both genotypes of mice were decreased after irradiation. However, TLR4−/− mice showed much more PBMC and BMC destruction (Figures 2b and c). These data consistently indicate that the main cause of death in TLR4−/− mice may be a severe and persistent BMC loss after IR, especially after a dose of 5 Gy.

Figure 2.

Increased mortality of TLR4−/− mice after IR associated with a severe and persistent BMC loss. (a) TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice were irradiated with 5 Gy and the femur was collected and subjected to an H and E assay at days 0, 1, 5, 14 and 28 post-IR. All images are × 100. The figure shows a typical H and E image of three independent experiments (N=3). (b, c). Kinetics of the BMC number and PBMC number in TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice after 5 Gy. (b) The BMC number was counted at days 0, 1, 5, 14 and 28 post-IR. (c) The PBMC numbers were measured at days 0, 1, 5, 14, 20 and 28 post-IR. *P<0.05

BMC loss in TLR4−/− mice was associated with enhanced cell apoptosis and reduced BMC cells proliferation

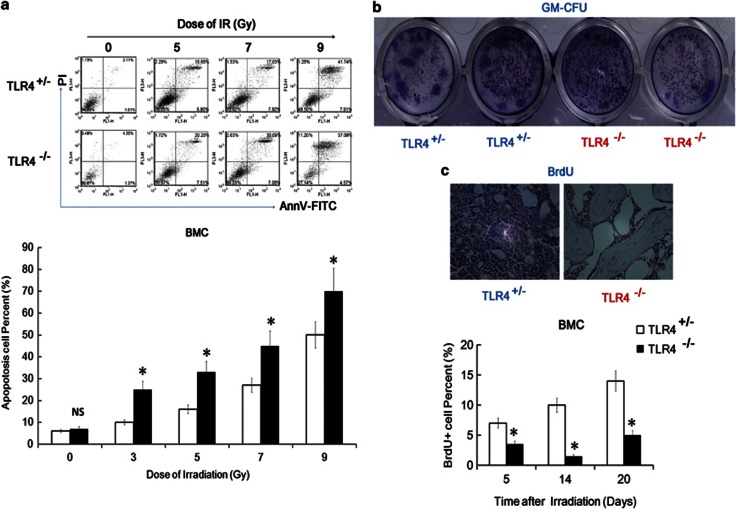

As the number of BMC can be influenced by the balance of cell death and cell proliferation within the BM,4, 5 we investigated the apoptotic and proliferative rates of BMC from TLR4−/− mice and TLR4+/−mice. We performed FACS assays to detect apoptosis levels in the BMC from TLR4−/− mice and TLR4+/− mice 24 h after different doses of IR. The time points used were selected on the basis of previous studies of radio-protection.4 As shown in Figure 3a, radiation-induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in BMC from both TLR4+/− mice and TLR 4−/− mice. However, BMC from TLR4−/− mice displayed a higher apoptosis rate than TLR4+/− mice after the same dose. Both FACS assays and TUNEL assays also indicated an increased apoptosis rate in many tissues, like spleen and thymus, in TLR4−/− mice after IR (Supplementary Figures S5A and S5B). However, the difference among the BMC was much greater between these two genotypes of mice than other tissues (Supplementary Figure S5C). These data indicated that TLR4 was required for basal radio-resistance by suppression of apoptosis in many tissues, and especially the BMC.

Figure 3.

TLR4 protects BMC from apoptosis and enhances their proliferation after IR. (a) TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice were irradiated with 0, 5, 7 or 9 Gy. BMC were prepared 24 h later, stained with AnnV-FITC and PI and apoptosis was detected by FACS assay. Upper figure shows typical data. Lower figure shows the statistical results. (b, c). BMC from TLR4−/− mice show significantly impaired proliferation capacity with or without IR. (b) Granulocyte-macrophage colony forming units were quantified in BMC obtained from TLR4−/− and TLR4+/− mice without IR ( × 100). (c) TLR4+/− and TLR4−/− mice were exposed to 5 Gy, femurs were harvested 5, 14 and 20 days later, and BMC proliferation was detected by the BrdU assay. Upper figure shows a typical BrdU stained section of femur from TLR4−/− mice and TLR4+/− mice 14 days post-IR ( × 100); Lower figure shows the statistical results. *P<0.05; NS: No significant difference detected

TLR4 was not required for BMC homeostasis but was required for optimal BMC proliferation

The above results can explain the severe BMC loss in TLR4−/− mice after IR. However, to explore why the BM loss was more persistent in TLR4−/− mice, granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units (GM-CFU) and 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) assays were performed to detect the proliferation capacity of BMC cells from TLR4−/− mice and TLR4+/− mice. The GM-CFU assay was performed for non-irradiated BMC from TLR4−/− and TLR4+/− mice, and TLR4−/− BMC showed significantly impaired proliferation capacity without IR (Figure 3b). Moreover, as detected by BrdU assay on days 5, 14 and 20 after 5 Gy (Figure 3c), not only the total number of BMC decreased in TLR4−/− mice after IR, but also irradiated BMC from TLR4−/− mice also showed significantly impaired tissue repair capacity in comparison to TLR4+/− mice.

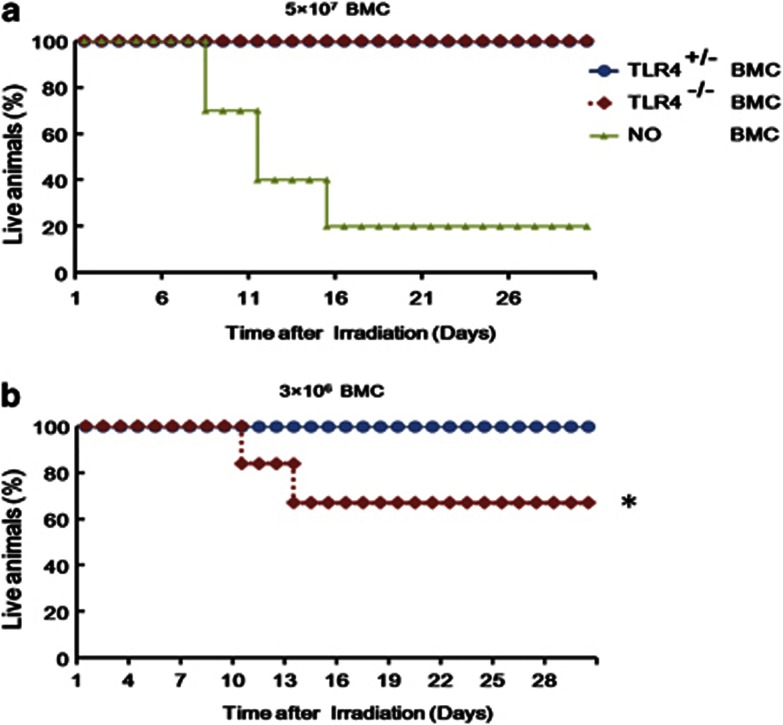

These data indicate that TLR4 may play an important role in the proliferation of BMC. To further study this role of TLR4 we performed BM transplantation assays. Wild-type (WT) C57BL/10 mice were exposed to 9 Gy, followed by reconstitution with 3 × 106 or 5 × 107 BMC from either TLR4−/− or TLR4+/− mice, and survival was recorded. As shown in Figure 4a, 5 × 107 BMC cells from both TLR4+/− and TLR4−/− mice can rescue mice from radiation damage. Together with data that unexposed TLR4−/− mice have a normal survival ability in SPF conditions; these data indicate that TLR4 was not required for BMC homeostasis. However, the data also show that the 3 × 106 BMC cells from TLR4+/− mice can successfully rescue the mice exposed to 9 Gy, whereas 3 × 106 BMC cells from TLR4−/− mice can only partly rescue the 9 Gy exposed mice (Figure 4b). These data indicate that TLR4−/− BMC have reduced proliferation ability and tissue repair capacity, and taken together, indicated that TLR4 was not required for BMC homeostasis but was required for optimal BMC proliferation.

Figure 4.

Difference between BMC cells from TLR4+/− and TLR4−/− mice in BM re-constitution. WTC57BL/10 mice were exposed to 9 Gy of γ-irradiation at 1 Gy/min and then reconstituted with 3 × 106 or 5 × 107 BMC from either TLR4+/− mice or TLR4−/− mice, and survival measured. (a) displays three groups: BM reconstitution with 5 × 107 BMC from TLR4+/− mice; BM reconstitution with 5 × 107 BMC from TLR4−/− mice and the no BM reconstitution group; (b) shows two groups: BM reconstitution with 3 × 106 BMC cells from either TLR4+/− or TLR4−/− mice. *P<0.05

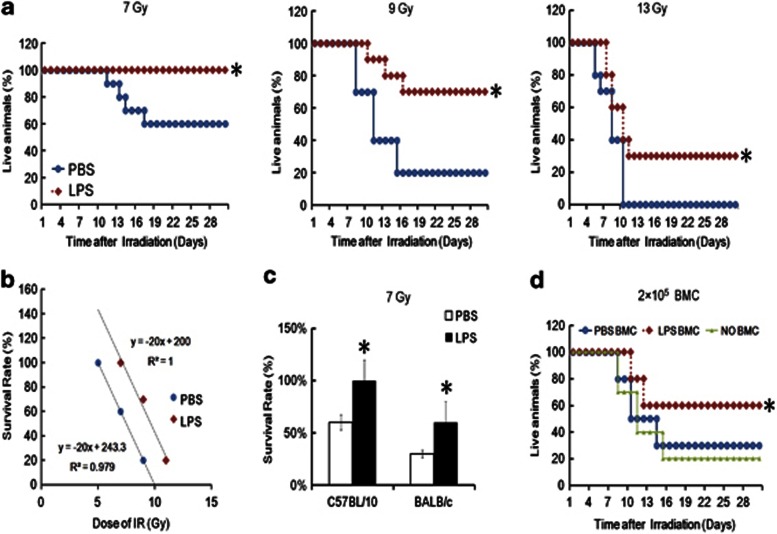

TLR4 in vitro agonist LPS showed a strong radio-protective role in vivo

The role of TLR4 in vivo and in vitro ligands in basal radio-protection was analyzed. LPS at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg body weight, given 24 h before radiation exposure displayed significant radio-protective effects on C57BL/10 mice exposed to doses of 7, 9 or 13 Gy (Figure 5a). The calculated DRF of LPS was 1.29 (LPS versus PBS) (Figure 5b). Furthermore, the TLR4 agonist LPS had a potent radio-protective effect on both C57BL/10 mice and BALB/c mice (Figure 5c). To further show the potential radioprotective role of LPS, BMC from mice given LPS was examined for their ability to rescue mice from lethal radiation. Specifically, BMC were isolated from un-irradiated mice injected with LPS or vehicle (PBS) 24 h previously and then 2 × 105 cells were transferred to 9 Gy irradiated mice. Transfer of this relatively small number of cells isolated from PBS-injected mice did not reduce radiation-induced mortality. On the contrary, transferring BMC from mice treated with LPS partially rescued the mice from radiation-induced mortality (Figure 5d). These data indicate that the TLR4 in vitro ligand LPS acts as a radio-protective agent in different strains of mice in vivo.

Figure 5.

TLR4 in vitro agonist LPS shows a strong radio-protective role in vivo. (a) C57BL/10 mice (20 g in weight, N=20 per group) were injected with LPS at 2.5 mg/kg body weight and then 24 h later subjected to 7, 9 or 13 Gy TBI as indicated. Control mice received PBS. Survival was recorded. (b) Linear regression analysis of the survival rate for mice treated with LPS or PBS after IR. The equation and the correlation coefficient for the line are given. The calculated DRF using these equations was 1.29 (LPS treated mice versus PBS treated mice). (c) LPS protects both C57BL/10 mice and BALB/c mice from radiation injury. (d) WT C57BL/10 mice were exposed to 9 Gy of γ-irradiation at 1 Gy/min and then reconstituted with 2 × 105 of BMC from C57BL/10 mice treated with or without LPS (2.5 mg/kg) 24 h previously. *P<0.05

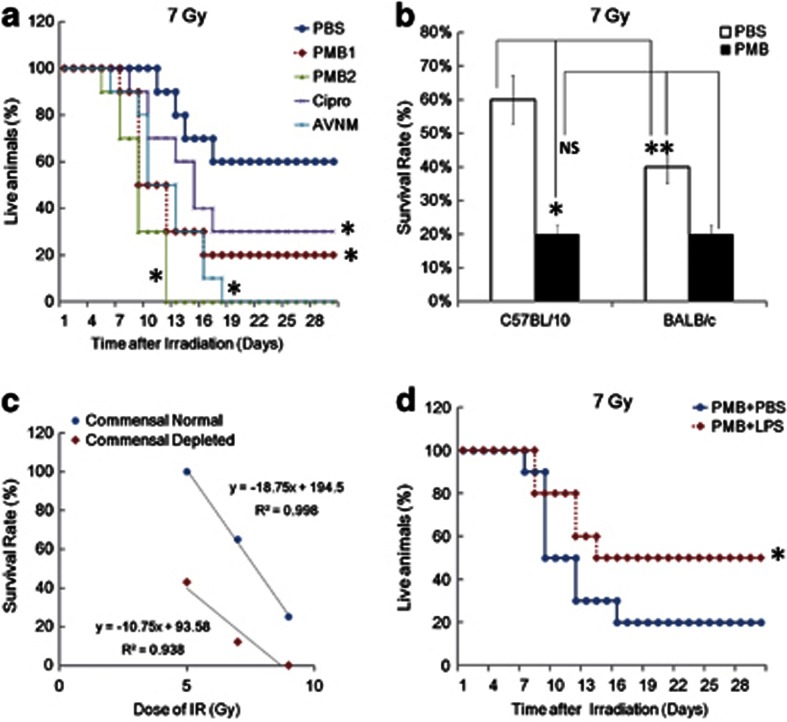

TLR4 in vivo ligands are required for basal radio-resistance

The in vivo ligands of TLR4 are generated by commensal microorganisms.18, 19 To further analyze the role of TLR4 in vivo ligands in basal radio-protection, we used four different, generally accepted commensal microflora depleting methods to deplete the TLR4 in vivo ligands as previously described.18, 19 The commensal microflora depletion was verified by bacterial culture of fecal matter removed from colons using sterile techniques. We found that in vivo depletion of TLR4 ligands, by all four methods, induced severe mortality in irradiated C57BL/10 mice, which mimicked TLR4−/− mice (Figure 6a). Commensal-depleted mice demonstrated more weight loss, less water and food consumption, and lower PBMC counts compared with commensal normal mice (Supplementary Figure S6). Commensal depletion also impaired the survival capacity of both C57BL/10 mice and BALB/c mice after IR (Figure 6b). Although the BALB/c mice strain was more radiosensitive than the C57BL/10 mice strain, the commensal-depleted C57BL/10 mice and BALB/c mice showed similar, high radio-sensitivity (Figure 6b). This data indicated that the TLR4 and its' in vivo ligands may be part of the mediators of radio-sensitivity variations between C57BL/10 mice and BALB/c mice strains. Regression analysis of the radiation survival data indicated that the DRF was 1.54 (commensal normal mice versus commensal-depleted mice), which is higher than the calculated DRF of TLR4 (Figures 6c and 1b). As shown in Figure 6d, reconstitution of commensal-depleted animals with exogenous LPS could partly restore the radio-resistance of commensal-depleted mice exposed to IR. These data indicate that TLR4 and its in vivo ligands are required for optimal basal radio-resistance. Further, these data also suggest that management of gut flora through antibiotic or possibly probiotic therapy may alter the innate response to total body irradiation.

Figure 6.

Depletion of TLR4 in vivo ligands impaired basal radio-resistance. (a). C57BL/10 mice (20 g in weight, N=20 per group) pretreated with or without four different gut flora depletion methods (Materials and Method section) and then subjected to 7 Gy IR. The survival was recorded. (b) Commensal gut flora depletion impaired radio-resistance in both C57BL/10 mice and BALB/c mice and attenuates the radio-sensitivity variation between these two strains of mice. (c) Linear regression analysis of the survival rate for commensal-depleted mice and commensal normal control mice after IR. The equation and the correlation coefficient for the line are given. The calculated DRF using these equations was 1.54 (commensal normal mice versus commensal-depleted mice). (d) Reconstitution of commensal gut flora-depleted animals with LPS could partly rescue the severe mortality of commensal gut flora-depleted mice after IR. *P<0.05; NS: No significant difference detected

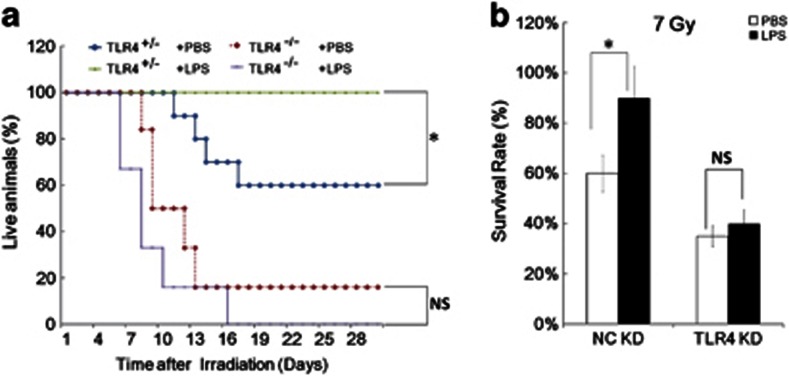

TLR4 is required for LPS-induced radio-protection

In vivo experiments were performed to determine whether the radio-protective role of TLR4 agonist LPS was TLR4 dependent. As shown in Figure 7a, LPS can protect TLR4+/−mice from radiation damage, but TLR4 agonist LPS displayed no radio-protective effect on the survival of TLR4−/−mice. On the contrary, LPS reduced the radio-resistance of TLR4−/−mice (Figure 7a). A similar response was seen in TLR4 in vivo KD experiments using C57BL/10 mice. As shown in Figure 7b, mice injected with the TLR4 specific in vivo KD reagents displayed less ability to be protected by LPS than mice injected with the non-specific control in vivo KD reagents. Thus, we conclude that radio-protection by TLR4 agonist LPS is TLR4 dependent.

Figure 7.

The radio-protective role of TLR4 agonist LPS in a TLR4 dependent manner. (a) LPS can protect TLR4+/− mice, but not TLR4−/− mice, from radiation damage. N=10, three repeats. (b) Male C57BL/10 mice, 6 weeks of age, injected with TLR4 specific in vivo KD reagents or with non-specific control in vivo KD reagents (From ABI, once a day for 2 days, N=12 in each group). Forty-eight hours later mice were treated with or without LPS at 2.5 mg/kg body weight for another 24 h, and then exposed to 7 Gy. The figure shows the survival rate of each group. *P<0.05; NS: No significant difference detected

IR enhanced serum LPS levels in a commensal dependent manner

To further explore the role of TLR4 and its ligands in radio-protection, we studied whether the levels of TLR4 and its ligand LPS can be induced or enhanced by radiation in vivo. We found that the serum LPS level in normal mice were elevated 2–6 days after 5 Gy (Figure 8a). We also found that the serum LPS level in normal mice were elevated 2 days after 3, 5, 7 and 9 Gy (Figure 8b). As LPS acts as a strong radio-protective agent in different strains of mice in vivo, these data indicated that exposure to radiation may lead to significant endotoxemia that also confers endogenous protection from irradiation. Further, we detected the possible mechanism of radiation-induced endotoxemia. We found that the serum LPS was elevated to a similar level 2 days after 5 Gy in both TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice. Commensal-depleted mice demonstrated a very weak LPS elevation in serum, which correlated well with the increased death of these mice after IR (Figures 8c and d). These data indicate that the main but perhaps not only source of serum LPS-induced by IR were the gut commensal microflora. This data is consistent with our finding that the in vivo ligand of TLR4 played a critical role in basal radio-resistance, and indicates that the radiation-induced LPS may also confer endogenous protection from irradiation. In addition, TLR4 ligands can be altered by IR, and FACS and q-PCR assays showed that 5 Gy exposure increased the TLR4 mRNA and TLR4 protein level in spleen and PBMC (Supplementary Figure S7A). However, there was no significant increase in the absolute number of host TLR4+ cells in spleen and PBMC, but, on the contrary, a slight decrease (Supplementary Figure S7B). However, TLR4 negative cells in spleen and PBMC showed a much greater decrease than TLR4+ cells (Supplementary Figure S7B). These data provide novel evidence that the TLR4 and its in vivo ligands played critical roles in basal radio-resistance.

Figure 8.

Radiation leads to significant endotoxemia in a commensal dependent manner. (a) Normal C57BL/10 mice were exposed to 5 Gy and the level of LPS in serum was measured 0, 24, 48, 96 and 144 h after IR. (b) Normal C57BL/10 mice were subjected to 0, 3, 5, 7 and 9 Gy and the level of LPS in serum was measured 48 h after IR. (c) Age and sex matched TLR4+/− and TLR4−/− mice were treated with or without 5 Gy and the level of LPS in serum was detected 48 h after IR. (d) Age and sex matched commensal normal or gut flora-depleted animals were treated with or without 5 Gy and the level of LPS in serum was measured 48 h after IR. Cipro and PMB groups were two models of commensal-depleted animals (Methods section). *P<0.05; NS: No significant difference detected

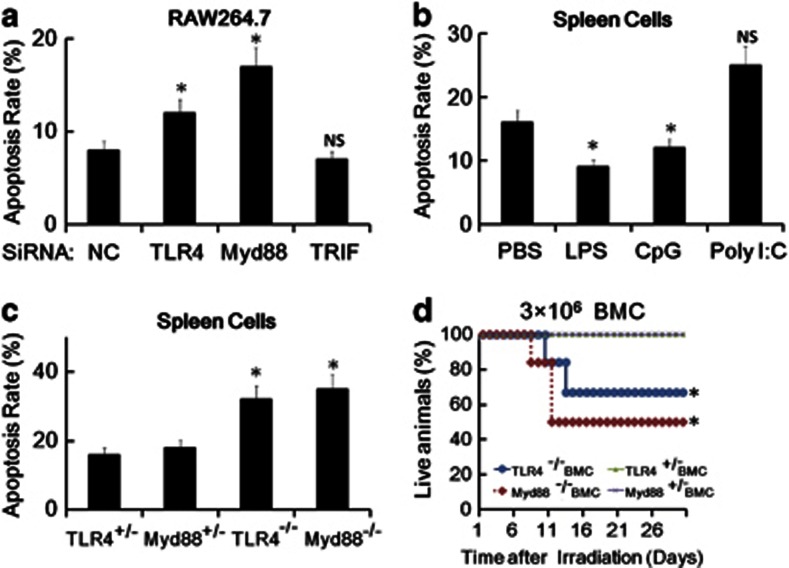

Myd88, but not TRIF, mediated TLR4-induced radio-protection

It is well known that TLR4 has two downstream pathways, the Myd88 dependent pathway and the TRIF dependent pathway, but the signal pathway and molecular mechanisms that mediate TLR4-induced basal radio-resistance are unclear. Therefore, both in vivo and in vitro experiments were conducted to explore whether Myd88 and TRIF participate in TLR4-induced radio-protection. In vitro KD assays in RAW264.7 cells were first used to explore this issue. As shown in Figure 9a, KD of Myd88 and TLR4, but not KD of TRIF, enhanced the apoptosis rate of the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 cells after IR. The potential radio-protective role of TLR9 agonist CpG ODN (which is totally Myd88 dependent and TRIF independent) and TLR3 agonist poly-I: C (which is totally TRIF dependent and Myd88 independent) was studied in mouse primary spleen cells from C57BL/10 mice. TLR9 agonist CpG ODN, but not TLR3 agonist poly-I: C, can significantly protect both mouse primary spleen cells from IR-induced apoptosis (Figure 9b). These data indicate that Myd88 may be an important mediator of TLR4-induced radio-protection, while TRIF, although very important in many pathways and functions of TLR4, may not participate in TLR4-induced radio-protection. To further explore the role of Myd88 in radio-protection, the radio-sensitivity of Myd88−/− mice was studied. Although TLR4−/− mice are fertile, the Myd88−/− mice have reduced reproduction ability, prohibiting the production of sufficient numbers of mice for a direct survival study. Therefore, bone marrow transplantation (BMT) was performed and FACS assays was used to study the radiation response of the primary cells from Myd88−/− mice and Myd88+/− mice. As shown in Figure 9c and Supplementary Figure S9, the AnnV-PI double staining assay and Trypan blue exclusion test indicated that primary spleen cells from Myd88−/− mice and TLR4−/− mice have a higher apoptosis rate and a lower cell viability when compared to primary spleen cells from Myd88+/− mice and TLR4+/− mice after 5 Gy. However, the primary spleen cells from Myd88−/− mice showed the lowest cell viability among the four. Furthermore, BMC cells from TLR4+/− mice and Myd88+/− mice largely rescued the mice from 9 Gy of radiation damage, while BMC from either TLR4−/− mice and Myd88−/− only partly rescued the mice from the same exposure in vivo (Figure 9d). Myd88−/− also demonstrated a much decreased tissue repair ability as compared to TLR4−/− BMC. Thus, our data indicate that Myd88, but not TRIF, mediated TLR4-induced radio-protection.

Figure 9.

Myd88, but not TRIF, mediates TLR4-induced radio-protection. (a–c) Different cells with different treatments were stained with AnnV-FITC and PI and the apoptosis rate was measured by FACS assay, and the apoptosis rate was calculated. (a) RAW264.7 cells were transfected with TLR4, Myd88, TRIF and the NC siRNAs that targeted mouse TLR4, Myd88,TRIF and theNC, respectively, for 48 h and then exposed to 10 Gy. Apoptotic rate was measured by FACS assay after another 24 h. (b) Primary spleen cells from WT mice were treated with 100 ng/ml LPS, 10 μg/ml poly(I:C), 1 μM CpG ODN or PBS control for 24 h and exposed to 5 Gy, Apoptotic rate was measured by FACS assay after another 24 h. (c) TLR4+/−, Myd88+/−, TLR4−/− and Myd88−/− mice were exposed to 5 Gy. Twenty-four hours later the primary spleen cells from these mice were prepared and the apoptotic rate was measured by FACS assay. (d) WT mice were exposed to 9 Gy of γ-radiation at 1 Gy/min, followed by reconstitution with 3 × 106 BMC from either TLR4+/−, Myd88+/−,TLR4−/− and Myd88−/− mice, and the survival rate was measured. *P<0.05; NS: No significant difference detected

Discussion

The results presented in this study reveal a new, non-immune function of TLR4 and its' in vivo ligands in mammalian radiation biology in vivo. In addition to the well-appreciated beneficial effects of commensal gut flora due to their metabolic activity,19 our data indicate that the interaction of commensal bacterial products with host microbial pattern recognition receptors plays a critical role in resistance to radiation-induced damage in different strains of mice in vivo.

We found that mice deficient in TLR4 were more susceptible to IR-induced mortality and morbidity. Mortality in TLR4−/− mice was associated with a severe and persistent BMC loss. Injection of LPS into normal mice, which is known to activate TLR4 in vivo, induced radio-resistance. Moreover, we also found that exposure to radiation leads to significant endotoxemia that also confers endogenous protection from irradiation. The circulating endotoxins appear to originate from the gut, as sterilization of the gut with antibiotics leads to increased mortality from radiation. These data suggest, it is important not to give antibiotics before whole body irradiation as they may sterilize the gut. Further data indicated that Myd88, but not TRIF, may be the critical adaptor in TLR4-induced radio-protection. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that TLR4 and its in vivo agonist are required for basal radio-resistance.

In this study, we compared the parameters between TLR4−/− and TLR4+/− mice, but not TLR4−/− and TLR4+/+ mice, in most of our experiments, a more accurate way to study the TLR4 molecular in radiation biology in vivo. However, we also did many experiment on the radiation response of TLR4+/+ mice. We found that TLR4+/− mice and TLR4+/+ mice displayed similar levels of TLR4 mRNA and TLR4 protein and these two genotypes of mice also displayed similar sensitivity to LPS as well as radiation (data not shown).

It was known that ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is a strong free-radical scavenger and free-radicals are major contributors to the damage/cell death induced by irradiation. Interesting, it is indeed that for mice sublethal endotoxin increases ascorbate recycling in liver and ascorbate concentration in liver, adrenal gland, heart and kidney.20 So, we guess that ascorbic acid may be involved in the effect of TLR4 in radio-resistance. As mice can biosynthesis ascorbic acid, and humans and primates cannot, we inferred that exposure to LPS may increase ascorbic acid biosynthesis in mice and changed behavior in humans and primates (like eating more fruits).

Taken together, these data suggest that TLR4 signaling may play a critical role in basal radio-resistance. Further, these data also suggest that management of gut flora through antibiotic or possibly probiotic therapy may alter the innate response to total body irradiation.

Materials and Methods

Breeding and genotyping of mice

Adult TLR4+/+ mice (C57BL/10 wild type, 6 weeks, 20 g), TLR4−/− mice (C57BL/10ScNJ TLR4 gene deleted type, 6 weeks, 20 g), TLR4+/− mice (F1 of C57BL/10 × C57BL/10ScNJ, 6 weeks, 20 g), Myd88+/+, Myd88− and Myd88+/− mice were generated and provided by the Model Animal Research Centre of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China) as described previously.21, 22 Breeding of Myd88+/−, C57BL/10 mice and C57BL/10ScNJ mice was also performed in the Laboratory Animal Center of the Second Military Medical University. As TLR4−/− mice are fertile, genotyping was done on F1 mice from a Myd88+/− background. These mice were anaesthetized, and a small tail clip was collected for DNA extraction and genotyping by a PCR method. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. C57BL/10 mice and BALB/C mice, 4–6 weeks of age, were also purchased from the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). All mice were housed in a SPF facility for all experiments.

Statement of animal care

All animal experiments were undertaken in accordance with the National Institute of Health ‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals' (NIH Publication No. 85–23, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, revised 1996), with the approval of the Laboratory Animal Center of the Second Military Medical University, Shanghai. The approval ID for this study was 20081020.

Reagents

Flow cytometry staining buffer (eBioscience, San-Diego, CA, USA); Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouseTLR4 (eBioscience, Cat. #:12-9041); Mouse IgG1 K Isotype Control PE (eBioscience, Cat. #: 12-4714-41); Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) double staining apoptosis assay kit were purchased from BIPEC. Trizol and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA); Anti-BrdU antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. # 5292) and rabbit anti-mouse IgG-horse radish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology; Ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin sulfate, metronidazole and ciprofloxacin were from Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, China. Poly I: C, PMB and LPS from Escherichia coli were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), and LPS was re-purified as described.23 DMEM and 1640 medium and fetal calf serum were from PAA, Austria. In vivo TLR4 specific KD reagent and the negative control (NC) KD reagent were from ABI. BrdU and 2′7′-di-chlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Molecular Probes, Biyuntian, China). All the primers used for real-time PCR assay and the TLR4, Myd88 and TRIF KD small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes used in this study were synthesized by Genepharm company (Shanghai, China), and the sequences of all the primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 (Mouse leukemic monocyte macrophage cell line) were obtained from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in 6-well plates at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 with DMEM and 1640 Medium (PAA, Austria) containing 10% fetal calf serum (PAA, Austria). Exponentially growing cells were used for experiments.

BMC and PBMC cell count

BMC were harvested from the femora and PBMC were prepared of euthanized TLR4 +/−mice versus TLR4−/− mice on days 1, 5, 10, 14, 20 and 28 post-irradiation, and cell populations were analyzed as described previously.4 Briefly, the BMC and PBMC cell number was determined by using CASY (Center for Complex Automated Systems) cell counting Technology (Innovatis, Germany). Alternatively, FACS assay and a microscope counting chamber (hemocytometer) method was also used to analysis, the BMC and PBMC cell number in different mice after IR.

Histological study

Tissues from BM, testis, thymus, liver, lung, kidney, spleen and colon of euthanized TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice with different treatments were harvested and subjected to histological assays as described previously. Briefly, tissues were dehydrated in an ascending grade of ethanol, cleared and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial sections of 2–7 microns thick were obtained using a rotatory microtome. The deparaffinized sections were stained routinely using the H and E method. Photomicrographs of the desired sections were obtained using a digital research photographic microscope.

BrdU labeling

Crypt stem cell survival was determined on days 5, 14 and 20 after irradiation by BrdU incorporation into proliferating crypt cells, using a modification of the microcolony assay as described previously, with a minor change of the secondary antibody.4 S-phase cells were labeled in vivo by administering BrdU (i.p., 120 mg/kg) to each mouse 2 h before euthanasia. Mice were sacrificed and the BM and small intestine were rapidly dissected, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections (2–5 μm) were cut perpendicular to the long axis of the intestines. Cells incorporating BrdU were visualized by immunohistochemistry using rat monoclonal anti-BrdU antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; Cat. # ab6326, dilutions 1:100) and secondary HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA).

FACS assay for detection of apoptosis rate

After different treatments, single cell suspensions of BM, spleen, liver and thymus tissues were prepared and labeled with annexin V-FITC and PI (provided by BIPEC), following the manufacturer's instructions as previously described.24, 25, 26 Samples were examined by FACS analysis, and the results were analyzed using Cell-Quest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

Quantitation of GM-CFU

GM-CFU were assayed in semisolid methylcellulose culture as described previously, with minor revisions.4 MononuclearBMC from femora and tibiae of non-irradiated TLR4+/− mice and TLR4−/− mice were pooled. Red blood cells were removed using RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). BMC were suspended in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium containing 30% fetal calf serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, 100 μM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse granulocyte monocyte-colony stimulating factor (mGM-CSF; Biosource Cat.# PMC2016) and 1 ng/ml recombinant IL-3 (mIL-3; ProTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). One-milliliter aliquots of the BMC suspension were plated in triplicate in 35-mm tissue culture dishes and incubated for 7 days in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Colonies were counted under a light microscope.

Bone marrow transplantation

BMT were established by following the method of Mulligan and colleaques27 with modifications. Briefly, adult (6-week-old) WT, C57BL/10 mice received 9 Gy TBI γ-radiation and then received a BMT from WT, TLR4+/−, Myd88+/−, TLR4−/− and Myd88 BMC, depending upon the requirement of the study. BMT was performed according to a standard protocol described previously. Recipient mice were injected with 2 × 105, 3 × 106 or 5 × 107 RBC cell-depleted BMC cells as indicated and mice survival was recorded.

Depletion of gut commensal microflora

The gut commensal microflora depletion method has been described previously by many groups.26, 27, 28 Briefly, C57BL/10 mice and BALB/c mice were subjected to four different drug cocktails of antibiotics, given in drinking water for 4 weeks before IR treatment, on the basis of a variation of the commensal depletion protocol. The first drug cocktail was AVNM, namely, ampicillin (A; 1 g/l), vancomycin (V; 500 mg/l), neomycin sulfate (N; 1 g/l), and metronidazole (M; 1 g/l) as described previously.18 The second drug cocktail was Cipro (ciprofloxacin, 50 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks; Bayer). The third and fourth drug cocktail were PMB1 (PMB dosage 1:PMB, 1 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks) and PMB2 (PMB dosage 2:PMB, 1 mg/kg/day drinking for 4 weeks and 1 mg/kg/day intravenous for the last 2 weeks) as described previously.28 The duration of 4 weeks for AVNM and PMB methods or 2 weeks for ciprofloxacin treatment was chosen on the basis of both empiric bacteriologic analysis of commensal growth in feces and also to ensure that detritus of commensal bacteria, which include TLR ligands, was absent from the mouse colons before the administration of IR. Complete depletion of commensal microflora was verified by bacterial analysis of colonic feces using generally accepted methods, as described previously.28

LPS treatment and detection of LPS

LPS from Escherichia coli was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), and LPS was re-purified as previously described.23 Re-purified LPS was dissolved in pyrogen-free PBS (BaiSai, Shanghai, China) and injected at a dose of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 2.5, 5, 25 or 50 mg/kg i.p. Control mice were injected with pyrogen-free PBS. In gut commensal microflora-depleted mice, LPS was injected at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg i.p. to reconstitute commensal-depleted animals with TLR ligands. A limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Biyuntian; Nanjing, China) was used to analyze the level of serum LPS on days 2, 4 and 6 after IR, as described previously.28

RNA interference

TLR4, Myd88, TRIF and the NC siRNA targeting mouse TLR4, Myd88,TRIF and the NC, respectively, were described previously29 and the sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Alternatively, in vivo TLR4 KD reagent (ABI) was also used for an in vitro TLR4 KD assay and found to have effective KD capacity in vitro. The interfering-RNA was normalized to a control non-specific siRNA sequence. RNA interferance was performed in RAW264.7 cells with the lipofestamine 2000 system as described previously.30

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between experimental groups and relevant controls (but not survival curves) were performed using a Student's t-test. Differences in survival of the various groups of mice were assessed using Kaplan–Meier plus Cox Regression Analysis with the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) software. The SPSS software generated a P-value and χ2-value for each analysis; P<0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Dr. Xuetao Cao from National Key Laboratory of Medical Immunology and Dr. Bing Yu from department of Cell Biology of our university for providing additional helps. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31070762).

Glossary

- ARS

acute radiation syndromes

- BMC

bone marrow cell

- GI

gastrointestinal tract

- HP

hematopoietic system

- IR

ionizing radiation

- KO

knockout

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- Myd88

myeloid differentiation primary response 88

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- PI

propidium iodide

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

- TRIF

TIR-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Stephanou

Supplementary Material

References

- Barcellos-Hoff MH, Park C, Wright EG. Radiation and the microenvironment—tumorigenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:867–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoms J, Goda JS, Zlotta AR, Fleshner NE, van der Kwast TH, Supiot S, et al. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy for locally advanced and high-risk prostate cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:107–113. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eifel PJ. Radiotherapy: intermediate-risk endometrial cancer—adjuvant treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:553–554. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdelya LG, Krivokrysenko VI, Tallant TC, Strom E, Gleiberman AS, Gupta D, et al. An agonist of toll-like receptor 5 has radioprotective activity in mouse and primate models. Science. 2008;320:226–230. doi: 10.1126/science.1154986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch DG, Santiago PM, di Tomaso E, Sullivan JM, Hou WS, Dayton T, et al. p53 controls radiation-induced gastrointestinal syndrome in mice independent of apoptosis. Science. 2010;327:593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1166202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Park JW. A manganese porphyrin complex is a novel radiation protector. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:272–283. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Park JW. Oxalomalate regulates ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–145. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science. 2003;300:1524–1525. doi: 10.1126/science.1085536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:823–835. doi: 10.1038/nri1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janot L, Sirard JC, Secher T, Noulin N, Fick L, Akira S, et al. Radioresistant cells expressing TLR5 control the respiratory epithelium's innate immune responses to flagellin. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1587–1596. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Sanders CJ, Frias A, Sloane VM, Xu J, et al. Flagellin treatment protects against chemicals, bacteria, viruses, and radiation. J Immunol. 2008;180:8280–8285. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaue D, McBride WH. Links between innate immunity and normal tissue radiobiology. Radiat Res Apr. 2010;173:406–417. doi: 10.1667/RR1931.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LA, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmausser B, Andrulis M, Endrich S, Lee SK, Josenhans C, Muller-Hermelink HK, et al. Expression and subcellular distribution of toll-like receptors TLR4, TLR5 and TLR9 on the gastric epithelium in Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:521–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Takeda K. Current views of toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010;2010:240365. doi: 10.1155/2010/240365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagarasan S, Muramatsu M, Suzuki K, Nagaoka H, Hiai H, Honjo T. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science. 2002;298:1424–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.1077336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo SM, Tan CH, Dragan M, Wilson JX. Endotoxin increases ascorbate recycling and concentration in mouse liver. J Nutr. 2005;135:2411–2416. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Zhang F, Wang L, Zhang G, Wang Z, Chen J, et al. Lipopolysaccharide preconditioning enhances the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in a rat model of acute myocardial infarction. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:74. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Gao F, Li B, Mitchel RE, Liu X, Lin J, et al. TLR4 knockout protects mice from radiation-induced thymic lymphoma by downregulation of IL6 and miR-21. Leukemia. 2011;25:1516–1519. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H, Zhao W, Hou J, Zhang Y, Xie Y, Zheng Y, et al. SHP-2 phosphatase negatively regulates the TRIF adaptor protein-dependent type I interferon and proinflammatory cytokine production. Immunity. 2006;25:919–928. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Li B, Cheng Y, Lin J, Hao J, Zhang S, et al. MiR-21 plays an important role in radiation induced carcinogenesis in BALB/c mice by directly targeting the tumor suppressor gene Big-h3. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:347–363. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Zhou C, Gao F, Cai S, Zhang C, Zhao L, et al. MiR-34a in age and tissue related radio-sensitivity and serum miR-34a as a novel indicator of radiation injury. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:221–233. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Lin J, Zhao L, Yang Y, Gao F, Li B, et al. Gamma-ray irradiation impairs dendritic cell migration to CCL19 by down-regulation of CCR7 and induction of cell apoptosis. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:168–179. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gussoni E, Soneoka Y, Strickland CD, Buzney EA, Khan MK, Flint AF, et al. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature. 1999;401:390–394. doi: 10.1038/43919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulos CM, Wrzesinski C, Kaiser A, Hinrichs CS, Chieppa M, Cassard L, et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells via TLR4 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2197–2204. doi: 10.1172/JCI32205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi HY, Shelhamer JH. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling regulates cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation and lipid generation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38969–38975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H, Hou J, Zhou J, Zhao W, Xu H, Zheng Y, et al. Phosphatase SHP-1 promotes TLR- and RIG-I-activated production of type I interferon by inhibiting the kinase IRAK1. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:542–550. doi: 10.1038/ni.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.