The notion that humans, animals and the environment are tightly linked and that their respective well-beings are interdependent has been recognized for centuries. However, the sophistication of these interactions has only begun to be revealed. Even by the late nineteenth century, it was established knowledge that human and animal health have many commonalities; an insight that more recently led to the term ‘One Medicine’, coined in 1984 to integrate human and veterinary health and research. In 2003, after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, One Medicine evolved into the concept of ‘One Health’, which expands the idea beyond a focus on the health of animals and humans to include health service delivery, environmental health and ecosystem services (for further reading, see Sidebar A). It defines ‘health’ as a broader concept, whereby humans, animals and the environment are inextricably linked and where each need equal attention to ensure optimal health for all. Although it is an interesting and forward-looking concept, One Health has unfortunately not gained significant attention, particularly in the area of human health.

Sidebar A | Further reading.

One Medicine/One Health

Zinsstag J et al (2012) Ecohealth 9: 107–110. Zinsstag and colleagues describe the evolution of the One Medicine concept, traceable to the late 1800s. It focuses on the realization that both human and veterinary medicine are based on the same broad principles.

Toxoplasma gondii

Dass SA et al (2011) PLoS ONE 6: e27229. Female rats find Toxoplasma gondii-infected males more attractive. This parasite therefore manipulates mate choice so that, contrary to most cases of sexual selection, the host sexual signalling operates to the advantage of the parasite.

Flegr J (2013) J Exp Biol 216: 127–133. The author reviews the evidence for Toxoplasma gondii infection causing changes in human personality, reaction time, immunosuppression and even the initiation of more severe forms of schizophrenia.

Pathogens, population densities, species diversity and ecology

Hilker FM, Schmitz K (2008) J Theor Biol 255: 299–306. One envisages that introduction of a pathogen to a predator can lead to an increase in prey density. However, these authors outline that the system is highly complex, and that pathogen introduction can lead to either extinction at one extreme or population stabilization at another.

Crawford AJ, Lips KR, Bermingham E (2010) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 13777–13782. A fungal pathogen is devastating amphibian populations worldwide. The authors show that in just one area, 30 species were lost, including five undescribed species, representing 41% of total amphibian lineage diversity in El Copé, Panama.

Pongsiri MJ et al (2009) BioScience 59: 945. The authors propose that habitat destruction leads to biodiversity loss and an increase in the incidence of pathogens. They propose that preservation of biodiversity is an effective way to protect human health.

Tuberculosis in humans and cattle

Gumi B et al (2012) Ecohealth 9: 139–149. This paper shows clearly how the main causative agent of bovine tuberculosis Mycobacterium bovis, was transmitted from cattle to humans and how M. tuberculosis, which is the causative agent of human tuberculosis, was transferred from owners to livestock.

Biodiversity loss and inflammatory disease

von Hertzen L, Hanski I, Haahtela T (2011) EMBO Rep 12: 1089–1093. This article extends the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ to outline two main modern trends occurring simultaneously: (i) the decline in biodiversity and lack of exposure of many humans to the broader environment; and (ii) the rapid increase in chronic diseases associated with inflammation. Low exposure to a biodiverse environment leads to immune system dysfunction and disease, as there is poor immune system stimulation.

Origins of the measles virus

Furuse Y, Suzuki A, Oshitani H (2010) Virol J 7: 52. Measles, caused by measles virus (MeV), is a member of the genus Morbillivirus and is most closely related to rinderpest virus (RPV), which is a pathogen of cattle. The authors conclude that divergence between MeV and RPV occurred approximately 900 years ago and that therefore, MeV might have originated from a virus of a non-human species and emerged as a human pathogen during approximately the eleventh to twelfth centuries.

To illustrate the complex, interwoven net of dependencies between humans, animals and the environment, let us consider the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. The common host of this protozoan is the domestic cat (Felidae), in which the sexual part of the parasite's life cycle takes place (Fig 1). However, T. gondii can infect many other warm-blooded species, from humans to birds, and has become endemic in many areas. Estimates put the number of infected humans at about 500 million, with large regional differences. Although toxoplasmosis is not usually a deadly disease, the infection does have some unpleasant side effects for many species, including its ability to modify the behaviour of rats and mice, making them drawn to, rather than fearful of, the scent of cats—probably a survival strategy for a parasite that requires cats to sexually reproduce (Sidebar A). In humans, toxoplasmosis during pregnancy can cause miscarriage and severe health effects if it infects the fetus, and it has been associated with a higher risk of schizophrenia in adults.

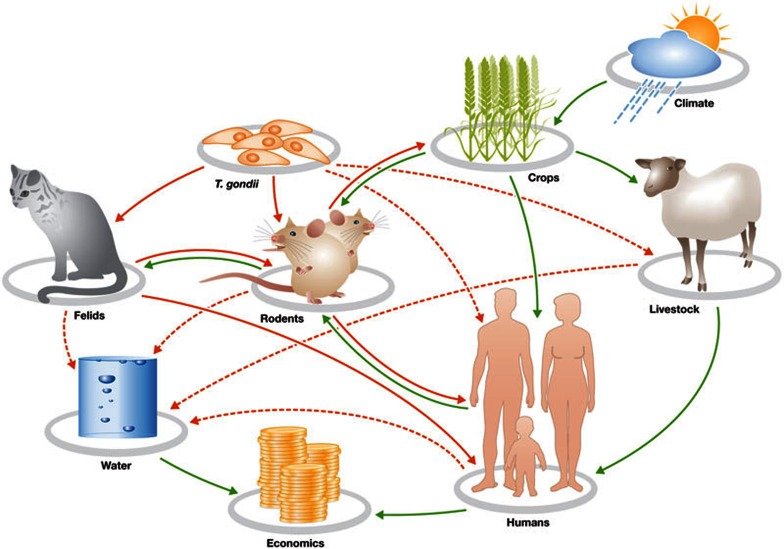

Figure 1.

A simple farm or ‘island scenario’ interaction network or ecosystem to illustrate interactions between the environment, animals, humans and a pathogen, Toxoplasma gondii. The dynamics of such a system can be investigated by using a series of differential equations that use quantitative parameters such as population density and population growth rate, which includes processes of birth, death and migration [3]. The connecting lines imply a possible (dotted lines) or known (solid lines) relationship, which might terminate with a negative (red lines) or positive influence (green lines) on the organism or factor.

Environmental factors determine the spread of toxoplasmosis. Felid hosts shed Toxoplasma oocysts with their faeces into the environment, including into water systems, from which the parasite infects other species. The main routes of infection for humans are thought to be direct contact with cats and eating undercooked meat from infected sheep. However, infection could also occur through water and contaminated vegetable or fruit produce. In California, for instance, increased mortality among sea otters has been linked to the pollution of fresh water systems by T. gondii. The prevalence of T. gondii infections among humans is therefore one result of the fact that most people on the planet do not have access to clean water. However, even in developed countries, a significant number of people are infected. One might ask whether this is a serious issue, because few people infected with T. gondii have to be clinically treated. However, T. gondii and its effects are subtle: the organism might lie dormant in the host and become active many years later, and it can cause a range of clinical problems from ocular degeneration to neurological and behavioural changes (Sidebar A). As there is no reliable drug or therapy that can clear the parasite from the patient, it puts the onus on developing and implementing preventive measures.

…a broader concept, whereby humans, animals and the environment are inextricably linked and where each need equal attention to ensure optimal health for all

This example and others, including avian influenza, Lyme disease and rabies, highlight the need to consider all the human, animal and environmental aspects of our shared One Health. Ignoring most of the components of a system to deal with just one aspect—in this case, toxoplasmosis in humans—is akin to treating the outward symptoms of a disease but not the underlying cause. To design effective interventions to reduce T. gondii prevalence, for example, we need as much information about the parasite, its hosts and environmental factors as possible, as we cannot ascertain which intervention will have the greatest effect or what the consequences of a certain intervention will be for other hosts and vectors.

A simple farmyard model (Fig 1) illustrates how humans, animals, T. gondii and the environment are all linked. Climate and other environmental factors affect grain yield, which in turn affects the rodent population—the most common intermediate host of the parasite. Rodents are preyed on by cats, which then shed the parasite into the environment, from where it infects rodents and humans. The abundance of rodents and felids therefore determines the level and distribution of T. gondii in the environment. We do not have sufficiently reliable data to model accurately this simple scenario or other more complex ecosystems, and can only guess about potential control measures. Moreover, we do not know what the effects of removing the parasite from the environment would be, as it could change population densities (Sidebar A). We also do not know what long-term effects the absence of T. gondii might have on the human immune system, as exposure to microorganisms is important for the maturation of our immune defence.

…we need as much information about the parasite, its hosts and environmental factors as possible, as we cannot ascertain which intervention will have the greatest effect…

The loss of livestock animals due to disease has an economic impact on farmers and communities, whilst human health itself is affected by zoonoses—pathogens that can jump species. Ever since humans began to domesticate and live in close proximity to animals, animal diseases have become a serious problem for human health. One of the oldest pathogens shared between Homo sapiens and cattle is the tuberculosis-causing Mycobacterium, which might have originated in humans. Although different strains of the bacteria affect cattle (M. bovis) and humans (M. tuberculosis), the pathogens are still capable of jumping back and forth. Humans experience zoonotic tuberculosis from infected animals, and animals can be infected by humans (anthropozoonotic tuberculosis; Sidebar A). There must be many common host factors in the case of tuberculosis, as is the case with many other diseases detected in different species.

Intense media coverage of human immunodeficiency virus, SARS, avian flu and other infectious diseases has drawn public awareness to the health risk of zoonoses and other emerging or re-emerging diseases. These threats are often the consequence of humans moving into a previously undisturbed ecosystem and making contact with new pathogens and their vectors, or if human activity disrupts ecosystems and thereby modifies the behaviour, migration and interaction of pathogens and their hosts. As such, humans constitute an invasive species that causes ecosystem change, either directly by destroying pristine areas such as the rainforests, or indirectly by causing global climate change, and through global trade and travel. Analysing how human activity increases health risk requires not only the expertise of veterinarians and physicians, but should include public health experts, ecologists, sociologists and evolutionary biologists.

Disease can be both a driver of and a consequence of biodiversity change. When discussing and applying the concept of One Health, it is therefore important not to limit the focus to humans or infectious diseases. Pathogens are also an important factor for species loss (Sidebar A), although most cases probably involve more than one cause. Conversely, biodiversity loss affects disease ecology (Sidebar A). Disease can change the composition and distribution of species in ecosystems. A good example is rinderpest, which affected the African savannah landscape with consequences that are still felt more than a century later, such as the balance between grassland and bush, and the change in distribution of the tsetse fly and trypanosomiasis. It can also influence land use by humans spatially or temporally—for instance, trypanosomiasis and foot-and-mouth disease have effects on agriculture and its impact on ecosystems in affected areas.

We should not focus only on infectious disease. It is possible that environmental impacts and declines in biodiversity could be related to the increase in chronic diseases (Sidebar A). According to the ‘hygiene hypothesis’, environments with high microbial biodiversity are less likely to have a high prevalence of allergic and autoimmune diseases. If this hypothesis is correct, then it is perhaps not surprising that we see a rapid increase in inflammatory disease with increasing urbanization and ongoing loss of biodiversity. It is anything but simple to prove causality in this case; however, ecosystems research has shown that high biodiversity is associated with tolerance and resilience, which are clearly lacking in the case of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

The economic and health impact of animal pathogens precipitated early attempts to fight these animal diseases. In the eighteenth century, for example, Pope Clement XI issued instructions that rinderpest should be controlled, which eventually led to a common veterinary disease control practice of ‘test and slaughter’. If we take the One Health concept seriously, we would have to expand the focus beyond animal diseases and invest more effort in addressing animal and environmental health, given that both are intricately linked to human health. This raises the problem, however, of how to focus limited resources efficiently.

Ever since humans began to domesticate and live in close proximity to animals, animal diseases have become a serious problem for human health

In our view, the interfaces between each component of the One Health system are the most promising focus. In the case of T. gondii, the most obvious interface is between humans and the domestic cat. Intervening here could go a long way to reducing disease burden. However, it would require more knowledge about how T. gondii is transmitted to humans and sheep for example—a sensitive and specific multi-species diagnostic assay—and better treatment options. The social aspect requires delicate handling in this era of social alienation, in which many humans are emotionally dependent on pets such as cats.

The One Health principles would also be useful for dealing with avian influenza, another example of a disease that thrives at the interfaces of humans and animals, driven by environmental factors. This disease, or rather group of diseases, is caused by a plethora of influenza A viruses, which are classified according to their surface antigens. They are further subdivided into highly pathogenic and low pathogenic strains, referring to their ability to cause disease in domestic chickens. Outbreaks of highly pathogenic and low pathogenic avian influenza have occurred on every continent because wild birds, in particular water-birds, that migrate vast distances and mix together with domestic birds at seasonal breeding and feeding grounds are an important reservoir of the disease. Wild birds are usually asymptomatic carriers of a low pathogenic virus, which on contact with local birds, including domestic poultry, can mutate into a highly pathogenic strain. However, avian influenza strains can cause mass mortalities among wild bird populations, such as in South Africa in 1961, when the virus decimated the local population of common terns in the Cape Province.

The social aspect requires delicate handling in this era of social alienation, in which many humans are emotionally dependent on pets such as cats

Most avian influenza strains are not capable of infecting humans, but if they do they can cause severe disease and high mortality. The main culprit is H5N1, which has killed hundreds of people in Asia and North Africa but, luckily, is not transmissible between humans. However, the ‘Spanish flu’ of 1918 was also caused by an avian influenza virus, so we must assume that H5N1 has the same potential to cause a similar pandemic. In fact, avian influenza viruses can infect all mammalian species, not just humans, which creates new reservoirs for the virus and increases the threat of an epizootic for many species. It is clear that the environment and its interface with wild and domestic animals should be an important factor for designing new control strategies for avian flu.

Given the potential of avian influenza viruses to cause mass mortalities, coupled with the public fear of ‘bird flu’, governments have ordered the culling of all birds in areas affected with a highly pathogenic outbreak. The economic costs—which range from less food and income for the rural poor to the reduction of tourism owing to fear of travel—far outweigh the direct costs of the disease. Poultry trade and consumption drops worldwide when an outbreak of avian influenza is reported anywhere. Thus, we must establish the appropriate trade-off between effective control measures that protect human and animal health and the economic damage they cause, which will cause direct harm to people and indirect harm to the environment. Furthermore, control strategies only work when they are fully supported and implemented by the affected communities. Eradication of flocks or pets might prompt the illegal movement of animals, further spreading the disease. Some farmers might believe that culling wild birds will protect their livestock. Many cultures do not even accept the premise that humans can catch diseases from other species and even among educated laypeople, there is little awareness of how avian influenza is transmitted.

These considerations equally apply to many other diseases. Malaria, haemorrhagic fevers, hantaviruses and rabies are all well-known cases with strong links to animal health and environmental factors. Even a virus such as measles, which was thought to have been specific to humans since prehistoric times, was found to have descended from the rinderpest virus; both are a Morbillivirus. This transition occurred either in the seventh century, or more probably, between the eleventh and twelfth centuries (Sidebar A). This example provides further arguments to those who regard control of animal diseases ultimately as public-health measures to protect people.

So far, we have focused on fighting infectious diseases and pathogens. But the concept of One Health, by including the environment in the broadest sense, goes beyond this. In fact, do we know what other, possibly detrimental consequences the fight against microorganisms might have? We are only beginning to realize the beneficial effects of bacteria or viruses—not just the role of our gut microflora for digestion and health, but also the microbial zoo on our skin and in our environment.

…we must establish the appropriate trade-off between effective control measures that protect human and animal health and the economic damage they cause

In an elegant study of Malawian identical twins who were discordant for kwashiorkor—a severe form of malnutrition primarily characterized by insufficient protein in the diet—the authors demonstrated the crucial role of gut microbiota for our health [1]. They showed that seeding the gut of previously germ-free mice with gut flora from the healthy twins caused no ill effects, whilst using the gut flora from the kwashiorkor twins effectively caused kwashiorkor in the mice, which could be only transiently ameliorated by a therapeutic diet.

An even more subtle example is type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease which has a distinct gender bias. Male hormones confer resistance to diabetes in a non-obese diabetic mouse model; interestingly this gender difference does not manifest under germ-free conditions. However, when the gut microbiota from the caeca of male mice are transferred to female mice before the onset of diabetes, those females have a lower risk of developing diabetes and an increase in testosterone levels, which is the source of said protection. This study demonstrates that the microbial fauna can regulate the sex hormones, resulting in resistance or susceptibility to autoimmune conditions, which is a revolutionary concept.

…it will require greater efforts still, before we can better understand how the environment and biodiversity, through the microbiota, determine and influence human health

Another example concerns psychiatric disorders, some of which seem to be caused by traumatic experiences around puberty, and for which prenatal infection is a known risk factor. These two elements were shown to influence each other: adult mice that were exposed to both prenatal infection and peripubertal stress were more likely to develop psychopathologies than mice that had stress in later adolescence [2]. Environmental microbes therefore influence susceptibility to psychiatric disorders, as described above with T. gondii. These examples come from animal studies, but the insights can be extended to human health. For instance, humans who have had antibiotic treatments in early life have an increased risk of asthma and inflammatory bowel disease. In mice, this is apparently caused by increased susceptibility to environmental triggers, owing to a reduction of natural killer T cells. This in turn is caused by the depletion of the commensal microbiota [3].

We are only making the first steps towards understanding the links between human and animal health and environmental microbes. Metagenomics of microbial diversity has already shown that the biological diversity of ecological niches is far more complex than previously thought. Meta-omics—the study of biological material from any environment on different levels of analyses—provides an even more powerful tool for observing and analysing the bacterial world. This notwithstanding, it will require greater efforts still, before we can better understand how the environment and biodiversity, through the microbiota, determine and influence human health.

Sadly, it seems that so far we have prioritized everything that matters only to our species, whilst animals and the environment have received short shrift. But this single-focus approach is the same approach that investment managers warn against when creating an investment portfolio; they recommend diversification of assets ‘for the long haul’. We have neglected the environment—climate change, invasive species and emerging diseases are just some of the signals—in favour of our own health and comfort. But we humans are not disconnected from the environment, although many city dwellers might forget this obvious truth. Our health and well-being are almost entirely determined by the fauna and flora on Earth; climate change and loss of biodiversity can, therefore, have unforeseeable but ultimately drastic effects on humanity.

In order to better appreciate that we are inextricably linked with the planet, we propose that the concept of One Health should be taught at schools and universities. We need to revisit our training so that all humans are aware that they are but one component of the systems biology of the Earth, and that shifting the balance will almost certainly come back to haunt us in an unexpected manner. Such a shift in thinking also has consequences for how we conduct and organize research, in particular in the life sciences. Traditionally, researchers have taken a reductionist, hypothesis-driven approach to understanding biological systems and worked in small research groups to tackle one problem at a time. It is unlikely that this approach lends itself to the analysis of whole ecosystems and to applying the concept of One Health as outlined in this article. However, as more discoveries are made and more information becomes available, there is a tendency towards specialization. This sends the scientific community in the opposite direction from the One Health movement. A different strategy is needed, whereby interdisciplinary collaboration and communication, more systems studies and ultimately larger projects tackle more complex biological systems and their dynamics, as it is highly unlikely that complex webs can be described by simple relationships between a small set of variables. Viewing any one problem from a One Health perspective reveals the gaps in our knowledge and raises new questions that should be addressed. The challenge notwithstanding, it is what we need to do to achieve a sustainable future for humans, the fauna, flora and environment on Earth.

Paul D van Helden

Eileen G Hoal

Lesley S van Helden

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Smith MI et al. (2013) Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science 339: 548–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanoli S et al. (2013) Stress in puberty unmasks latent neuropathological consequences of prenatal immune activation in mice. Science 339: 1095–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszak T et al. (2012) Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science 336: 489–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond B, McInnes J, Dambacher JM, Way S, Bergstrom DM (2011) Qualitative modelling of invasive species eradication on subantarctic Macquarie Island. J Appl Ecol 48: 181–191 [Google Scholar]