Abstract

CLP1 is the first discovered mammalian RNA kinase. However, its in vivo function has been entirely elusive. We have generated kinase-dead Clp1 (Clp1K/K) mice which exhibit a progressive loss of spinal motor neurons associated with axonal degeneration in peripheral nerves, denervation of neuromuscular junctions, and results in impaired motor function, muscle weakness, paralysis and fatal respiratory failure. Transgenic rescue experiments show that CLP1 functions in motor neurons. Mechanistically, loss of CLP1 activity results in accumulation of an entirely novel set of small RNA fragments, derived from aberrant processing of tyrosine pre-tRNA. These tRNA fragments sensitize cells to oxidative stress-induced p53 activation and p53-dependent cell death. Genetic inactivation of p53 rescues Clp1K/K mice from the motor neuron loss, muscle denervation and respiratory failure. Our experiments uncover a mechanistic link between tRNA processing, formation of a new RNA species and progressive loss of lower motor neurons regulated by p53.

RNA molecules undergo co- and post-transcriptional processing leading to mature, functional RNAs. Both in mammals and archaeabacteria CLP1 proteins are kinases that phosphorylate 5’ hydroxyl ends of RNA1,2,3. Human CLP1 is a component of the mRNA 3’ end cleavage and polyadenylation machinery4,5 and studies in yeast have postulated a function for CLP1 in coupling mRNA 3’ end processing with RNA Pol II transcriptional termination6,7,8. Unique to mammals is the association of CLP1 with the tRNA splicing endonuclease (TSEN) complex9. TSEN proteins remove the intron present within the anticodon loop of numerous pre-tRNAs generating 5′ and 3′ tRNA exon halves10. Within the TSEN complex, CLP1 phosphorylates 3’ tRNA exons in vitro1, potentially contributing to tRNA splicing in mammals11. Although CLP1 may participate in multiple RNA pathways and was identified as the first mammalian kinase phosphorylating RNA, the in vivo function of CLP1 in mammalian cells has remained elusive.

Here we report the generation and phenotypic analysis of CLP1 kinase-dead mice. Strikingly, these mice develop a progressive loss of lower motor neurons resulting in fatal deterioration of motor function. We also show that inactivation of CLP1 kinase activity results in accumulation of previously unreported tyrosine tRNA fragments that sensitize cells to activation of p53 in response to oxidative stress.

Results

Neonatal lethality of Clp1K/K mice

To assess the in vivo function of CLP1 we first generated global Clp1 knock-out mice. We never obtained any viable Clp1 null offspring, even when analyzed at embryonic day (ED) 6.5, indicating very early embryonic lethality. Consequently, we generated mice carrying a single amino acid change, lysine to alanine at position 127 (K127A), which is located within the Walker A ATP binding motif (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). This mutation abolishes CLP1 kinase activity1. Mice heterozygous for the K127A substitution (Clp1K/+) were intercrossed to generate homozygous offspring (Clp1K/K). Western blotting showed that the CLP1 K127A mutant protein was expressed at normal levels and that the Clp1K/K mutation impaired 5’ phosphorylation of a small duplex RNA substrate (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d). Therefore, we have successfully generated a knock-in mouse expressing kinase-dead CLP1.

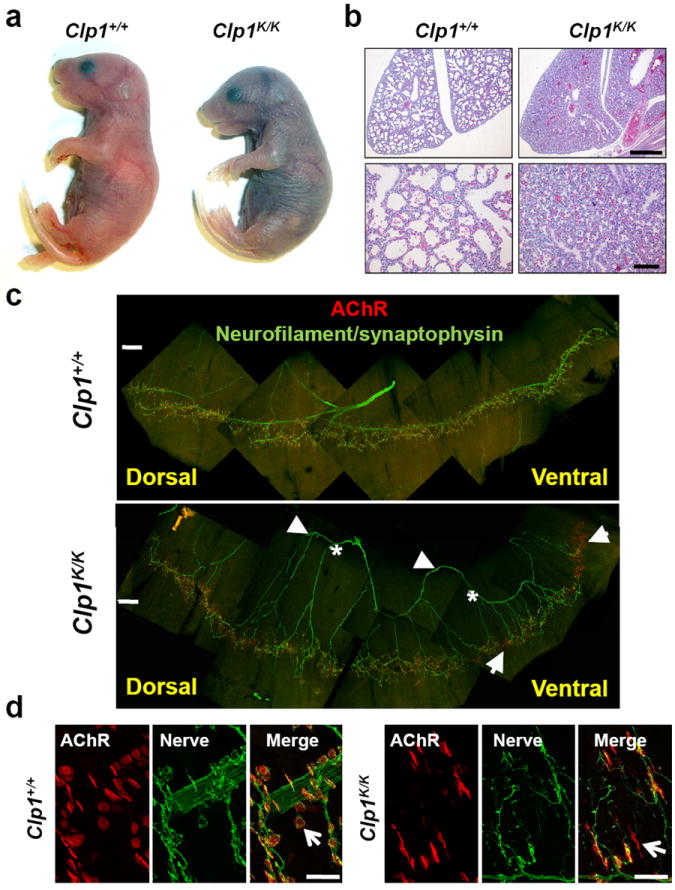

Clp1K/K mice were born at a normal Mendelian ratio. However, on a C57BL/6 background, all Clp1K/K mice died within hours after birth, most likely due to respiratory failure (Fig. 1a,b). This phenotype had complete penetrance (n > 50). Embryos and newborn Clp1K/K mice exhibited overtly normal lung development and morphogenesis, as indicated by Caveolin-1, surfactant A and surfactant C expression (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, all newborn Clp1K/K mice and ED18.5 embryos exhibited a lordotic body posture and dropping forelimbs, indicative of impaired motor functions (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 3a). Newborn Clp1K/K mice also exhibited reduced birth weight and were hyporesponsive to stimuli (Supplementary Fig. 3b); similar phenotypes in Kif1B mutant mice have been ascribed to motorsensory neuronal defects12. We therefore analyzed neuromuscular junctions (NMJ) in the diaphragm.

Figure 1. Respiratory failure and impaired innervation of the diaphragm.

a, Appearance and b, lung histology (H&E) of newborn Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates on a C57BL/6 background. Scale bars upper panels: 500 μm; lower panels: 100 μm. c,d, Whole mount immunostaining of diaphragm muscle of ED18.5 Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates showing postsynaptic AChR clusters (red, α-Bungarotoxin) and innervating motor axons and presynaptic nerve terminals (green, neurofilament/synaptophysin immunostaining). Asterisks: defasciculated main axon mislocalized to the periphery of the muscle; arrowheads: secondary branches coming from the main axon; arrows: areas of denervation. Magnifications in d, indicate severely disturbed NMJs in ED18.5 Clp1K/K embryos (arrow). Scale bars: c, 250μm, d, 25μm.

Control ED18.5 embryos exhibited the characteristic innervation pattern of the phrenic motor nerve bundle and had normal NMJs defined by co-localization of presynaptic terminals with postsynaptic clusters of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) as well as the presence of S100+ Schwann cells in the endplate (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 4). ED18.5 Clp1K/K embryos displayed defasciculation of the main phrenic nerve bundle; primary branches were mislocalized to the periphery and denervation of the ventral and dorsal diaphragm was prominent in all Clp1K/K mutants (Fig. 1c). NMJs were formed, but axon terminals appeared undifferentiated with smaller AChR clusters (Fig. 1d). S100 expression at the NMJ was absent in the Clp1K/K embryos, although Schwann cells appeared functionally intact since surviving peripheral axons were myelinated (Supplementary Fig. 4). Development and morphology of the heart, liver, kidney, colon, bladder, spleen, and thymus appeared normal at ED18.5. Thus, all newborn Clp1K/K mice exhibit impaired innervation of the diaphragm, which appears to cause lethal respiratory failure and neonatal death.

Embryonic loss of motor neurons

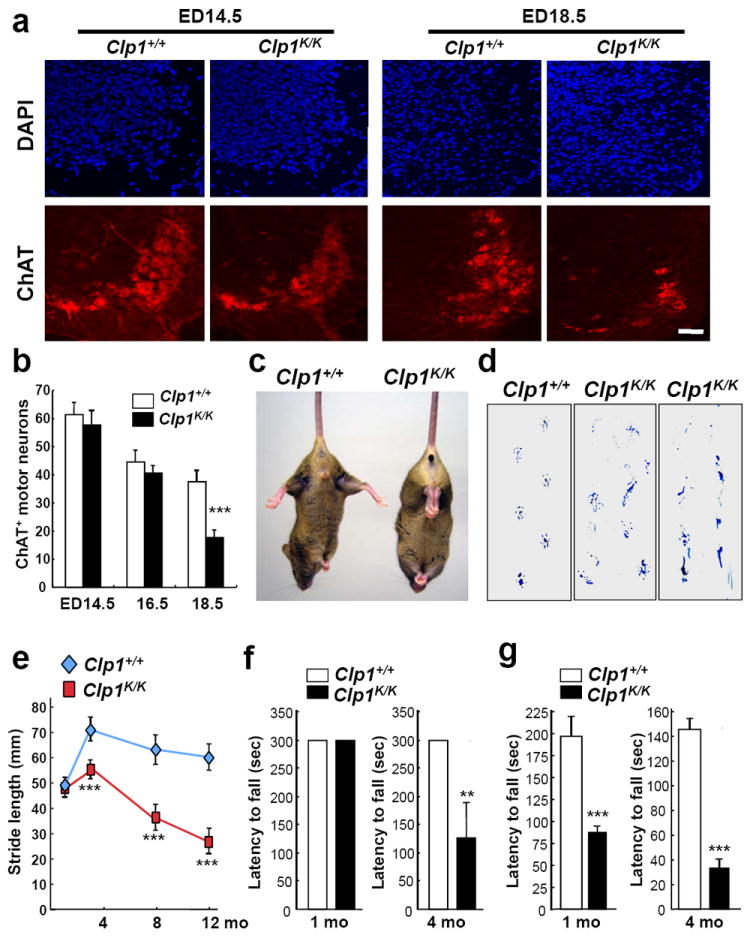

We next assessed NMJs in the diaphragm during embryogenesis. In Clp1K/K embryos, denervation was not found at ED14.5. However, we observed partial denervation and pronounced alteration in NMJ morphology at ED16.5 followed by a severe defect in the innervation of the NMJ of the diaphragm at ED18.5 (Fig. 1c,d; Supplementary Figs. 4-6). Moreover, whereas Clp1K/K embryos had normal numbers of choline acetyl transferase (ChAT)-expressing spinal motor neurons at ED14.5 and ED16.5, the numbers of ChAT+ motor neurons markedly declined in the spinal cord of ED18.5 Clp1K/K embryos (Fig. 2a,b; Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). Motor neuron numbers also declined in wild type embryos due to pruning, which has been linked to oxidative stress exposure13. NeuN staining to detect all neurons showed that the observed reduction in neuronal numbers was due to the loss of ChAT+ motor neurons (Supplementary Fig. 7c).

Figure 2. Viable Clp1K/K embryos develop neuromuscular atrophy.

a, Immunostaining for ChAT+ (red) motor neurons in the cervical (C4-C5) spinal cord of ED14.5 and ED18.5 Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates on a C57BL/6 background. DAPI staining is shown. Scale bar: 50μm. b, Mean numbers ± S.D. of ChAT+ motor neurons in the cervical (C4-C5) spinal cord of ED14.5, ED16.5, and ED18.5 Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates. n=5 mice per group. ***P<0.001 (t-test). c, Muscle weakness (impaired spreading of hind legs) in 3 months old Clp1K/K mice. d,e, Impaired walking strides in 1, 3, 8, and 12 months old Clp1K/K mice compared to Clp1+/+ littermates. Representative images in d, are from 12 months old mice, demonstrating shortened walking strides and paralysis in Clp1K/K mice. Data in e, are mean values ± S.D. n=5 mice per group. ***P<0.001 (t-test). f,g, Progressive impairment of motor functions in viable Clp1K/K mice as assessed by the latency to fall in a fixed (f) and accelerated (g) Rotarod test. Data (mean values ± S.D.) are from 1 month old Clp1+/+ (n=8) and Clp1K/K (n=7) and 4 months old Clp1+/+ (n=16) and Clp1K/K (n=14) mice. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (t-test).

To confirm loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord, we crossed Hb9-GFP transgenic mice onto a Clp1K/K background. Genetic GFP tagging showed that ED14.5 Clp1K/K embryos have similar numbers of Hb9+ cells as age-matched control embryos, but the numbers of Hb9-GFP+ cells declined in ED18.5 Clp1K/K embryos (Supplementary Fig. 7d). In whole mount visualizations of Hb9-GFP+ ED10.5 embryos, both development and segmental motor axon outgrowth were comparable between Clp1K/K and control embryos; 3D reconstructions further demonstrated comparable motor axon outgrowth at the thoracic region (segment T6-T7) in ED12.5 embryos (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). Moreover, the overall morphology of motor terminal branches and pathfinding of motor neurons at the intercostal muscles was comparable (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Thus, genetic inactivation of the RNA kinase function of CLP1 results in progressive loss of motor neurons in the cervical and lumbar spinal cord, with aberrant innervations and formation of NMJs in the diaphragm, and neonatal death.

Progressive loss of motor functions in viable Clp1K/K mice

All our results so far, 100% lethality of Clp1K/K pups at birth, were obtained on a C57BL/6 background. Similarly, we observed 100% lethality on a Balb/c background. However, when crossing the mutation onto a CBA/J mouse background, we obtained viable pups homozygous for the Clp1K/K mutation (Supplementary Fig. 9a). These mice exhibited motor ataxia (Supplementary Fig. 9b), impaired muscle strength, an altered walking stride, and diminished balance as determined by the fixed and accelerated Rotarod test (Fig. 2c-g), all indications of motor defects. The muscle weakness and impaired motor functions in these mice were progressive (Fig. 2e-g). Mice started to die around week 23 after birth and older Clp1K/K mice developed limb paralysis (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 9a,c). Sensory responses to noxious heat, mechanical stimulation and capsaicin-induced pain appeared normal in Clp1K/K littermates (Supplementary Fig. 10).

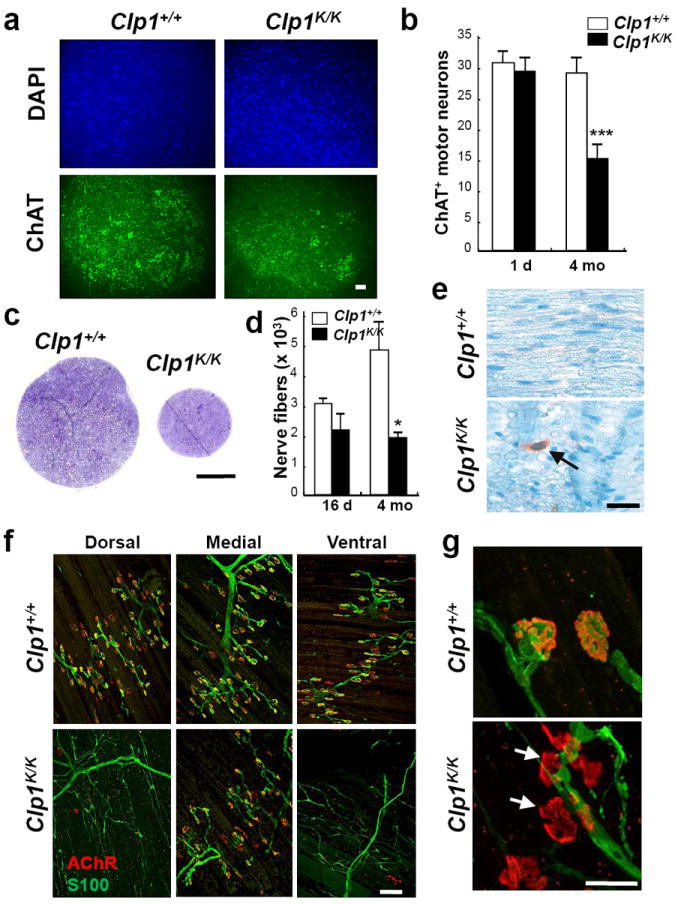

Whereas Clp1K/K neonates on the CBA/J background contained apparently normal numbers of spinal motor neurons, 4 months old Clp1K/K mice displayed both a marked reduction in ChAT+ and, as a second marker, SMI-32+ spinal motor neurons (Fig. 3a,b; Supplementary Fig. 11). The effects of the Clp1 mutation on upper motor neurons need to be assessed. Concordant with lower motor neuron loss, we observed axonopathy of peripheral nerves such as the sciatic nerve (Fig. 3c,d, Supplementary Fig. 12a-c). Immunostaining showed amyloid precursor protein (APP) positive structures, a marker for axonal injury14, in the sciatic nerve of adult Clp1K/K (Fig. 3e). In line with motor neuron loss, we observed a marked reduction in the number of large diameter (type 1A alpha) fibers, whereas the smaller sensory fibers were largely preserved (Supplementary Fig. 12d). Dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory neurons exhibited normal morphology and outgrowth. Whether developmental alterations in myelination also contribute to the phenotype needs to be further assessed. We also observed regional denervation and fragmentation of NMJs in the diaphragm and different limb and head skeletal muscles resulting in skeletal muscle atrophy; slow-twitch muscles (soleus, gluteus) were less affected than the fast-twitch EDL or gastrocnemius muscles (Fig. 3f,g; Supplementary Figs. 13-15). Similar results were obtained in SOD1 transgenic mice15. Thus, Clp1K/K mice develop progressive loss of spinal motor neurons and exhibit defective NMJs, resulting in impaired motor functions, muscular atrophy and limb paralysis.

Figure 3. Progressive loss of lower motor neurons.

a, Immunostaining for ChAT+ (green) motor neurons in the lumbar (L5) spinal cord of 4 months old Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates on a CBA/J background. DAPI counterstaining. b, Mean numbers ± S.D. of ChAT+ motor neurons in the lumbar (L5) spinal cord of 1 day and 4 months old Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates. n=5 mice per group. ***P<0.001 (t-test). c, Semi-thin cross-section of the sciatic nerve of 4 months old Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates. Toluidin blue staining. d, Mean numbers ± S.D. of total nerve fibers in the sciatic nerves of 16 days and 4 months old Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates. n=3 mice per group. *P<0.05 (t-test). e, Immunohistochemical detection of amyloid precursor protein (APP) (arrow) in the sciatic nerve of a 12 months old Clp1K/K mouse. f,g, Whole mount immunostaining depicting NMJs in diaphragms of 5 months old Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K littermates. Postsynaptic AChR clusters are stained with α-Bungarotoxin (red) and Schwann cells labeled with anti-S100 antibodies (green). Arrows in g show NMJ fragmentations. Scale bars: a, 50μm; c, 200μm; e, 100 μm; f, 25μm.

CLP1 is required for efficient tRNA exon generation

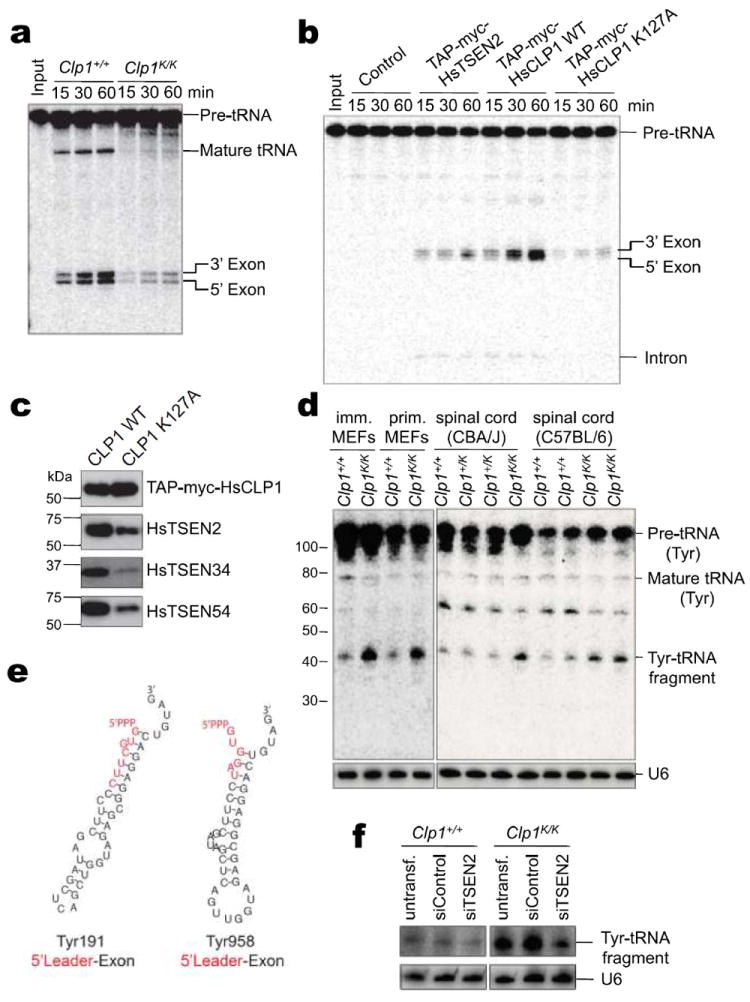

To assess potential roles in RNA metabolic processes, we first evaluated the function of CLP1 in mRNA 3’ end cleavage4. The kinetics of a pre-mRNA cleavage reaction in nuclear extracts from wild-type and Clp1K/K MEFs were similar (Supplementary Fig. 16a), suggesting that ATP binding and/or hydrolysis by CLP1 are dispensable for mRNA 3’ end cleavage. CLP1 has been implicated in RNA interference by its ability to phosphorylate small interfering RNAs in vitro1. We therefore assessed whether cellular microRNA (miRNA) processing or stability were affected by the CLP1 K127A mutation. However, the levels of various pre- and mature miRNAs did not differ between wild-type and Clp1K/K MEFs and tissues nor was there any impact on miRNA function using a luciferase reporter assay (Supplementary Fig. 16b,c). Furthermore, we found no significant differences in pre-mRNA splicing (Supplementary Fig. 17).

It has been reported that CLP1 is part of the human tRNA splicing endonuclease (TSEN) complex9 and is able to phosphorylate tRNA 3’ exons1. We therefore tested whether the Clp1K/K mutation affects tRNA splicing. Strikingly, nuclear extracts from Clp1K/K MEFs generated significantly lower levels of tRNA exons (Fig. 4a). In addition, tRNA 3’ exon halves formed by incubation with nuclear extracts isolated from Clp1K/K MEFs lacked a 5’ phosphate group; 5’ phosphorylation and exon generation were rescued by ectopic expression of wild-type CLP1 in Clp1K/K MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 18a-e). Similarly, pre-tRNA cleavage was partially restored in Clp1K/K MEFs stably expressing wild type CLP1 whereas overexpression of the CLP1 K127A mutant inhibited RNA phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 19a-d). Affinity-purified CLP1 K127A-containing TSEN complexes were deficient in the generation of tRNA exons, most probably due to reduced levels of TSEN2, TSEN34 and TSEN54 subunits (Fig. 4b,c); mRNA levels of TSEN2, TSEN34 and TSEN54 was not affected in Clp1K/K MEFs (not shown). Thus, the RNA kinase activity of CLP1 is important for the integrity of the TSEN complex and efficient generation of tRNA exons (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Figure 4. Identification of a novel tRNA fragment.

a, The RNA kinase activity of CLP1 is required for efficient tRNA exon generation in vitro. An internally labeled intron-containing yeast pre-tRNAPhe was incubated with nuclear extracts from immortalized Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K MEFs. Pre-tRNA processing was monitored by electrophoresis. b, One-step purified human TAP-myc-HsCLP1 (wild-type [WT] or K127A) and TAP-myc-HsTSEN2 complexes were assayed for pre-tRNA cleavage after elution with TEV proteinase (TEV eluate) by incubation with an internally labeled pre-tRNAPhe. Eluates from HeLa cells expressing the vector without insert were used as control. c, The level of TSEN proteins in TAP-myc-HsCLP1 (WT and K127A) TEV eluates was examined by Western blot. Similar CLP1 protein levels were confirmed using anti-myc antibodies. d, ~41-46-nt Tyr-tRNA fragments accumulate in primary and immortalized Clp1K/K MEFs and spinal cords of 4 months old CBA/J Clp1K/K and newborn C57BL/6 Clp1K/K mice. Northern blot analyses of total RNA were performed with a DNA/LNA probe complementary to the 5’exon of Tyr-tRNA. U6 RNA served as loading control. e, Secondary structure of the two most abundant tRNA fragment species, Tyr-tRNA M.musculus_chr14.trna191-TyrGTA and M.musculus_chr13.trna958-TyrGTA, as predicted by RNAfold. f, Detection of Tyr-tRNA fragments from Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K MEFs left untransfected or transfected with control siRNAs or siRNAs against TSEN2.

Accumulation of novel tyrosine tRNA fragments

Whereas most tRNAs are intron-less, all mouse tyrosine (Tyr) tRNA genes contain an intronic sequence. Strikingly, in Clp1K/K MEFs we detected accumulation of ~41-46-nt Tyr-tRNA fragments using a Northern probe against the 5’ exon (Fig. 4d). RNA sequencing revealed that this fragment comprises a 5’ leader followed by 5’ exon Tyr-tRNA sequences (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 21a,b). Enzymatic treatments uncovered a 5’ triphosphate modification (Supplementary Fig. 21c), indicating that this novel tRNA fragment contains a full-length 5’ leader sequence starting with the transcription initiator PPP-nucleotide. RNAi-mediated silencing of TSEN2 in MEFs resulted in decreased levels of tRNA fragments (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 21d). Bioinformatic and Northern blotting analyses revealed minor accumulation of such 5’ fragments from other intron-containing tRNAs, mostly arginine tRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 22).

A similar accumulation of tyrosine tRNA fragments was observed in the spinal cord of C57BL/6 Clp1K/K neonates and 4 months old Clp1K/K mice on a CBA/J background (Fig. 4d). Moreover, we observed elevated levels of these tRNA fragments in total cortex, muscle, heart, kidney, muscle, and liver (Supplementary Fig. 23a). Steady-state levels of mature tRNAs appeared normal in MEFs, the spinal cord of C57BL/6 Clp1K/K neonates and in postnatal CBA/J Clp1K/K mice (Supplementary Fig. 23b). Thus, loss of CLP1 kinase activity results in the accumulation of novel RNA fragments derived from pre-tRNA.

Susceptibility to oxidative stress-induced cell death

Other tRNA fragments, e.g. tiRNAs (tRNA-derived stress-induced fragments) are generated in the cytoplasm by the endonuclease Angiogenin acting on mature tRNAs16,17. Similar to tiRNAs, Tyr-tRNA fragments were also induced by H2O2, but were not generated by Angiogenin. Rather, Tyr-tRNA fragments were present in the nucleus and derive from pre-tRNAs actively transcribed by RNA Polymerase III (Supplementary Fig. 24a-d). Since Tyr-tRNA fragments were strongly induced by H2O2, we hypothesized that CLP1 might play a role in the oxidative stress response. In wild-type MEFs, the Tyr-tRNA fragments also accumulated after exposure to the ROS inducers glucose oxidase, menadione, and paraquat dichloride, but not nefazodone (Supplementary Fig. 25a-d). Treatment with the mitochondrial “poisons” FCCP (Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone) and rotenone, the apoptosis inducer staurosporine, the protein synthesis inhibitor puromycin, and the DNA damaging agent camptothecin did not trigger the accumulation of Tyr-tRNA fragments (Supplementary Fig. 25e,f). Importantly, upon H2O2 and glucose oxidase challenge, we observed increased death of Clp1K/K MEFs; re-expression of wild type CLP1 restored the survival rate to that of control MEFs (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 26a).

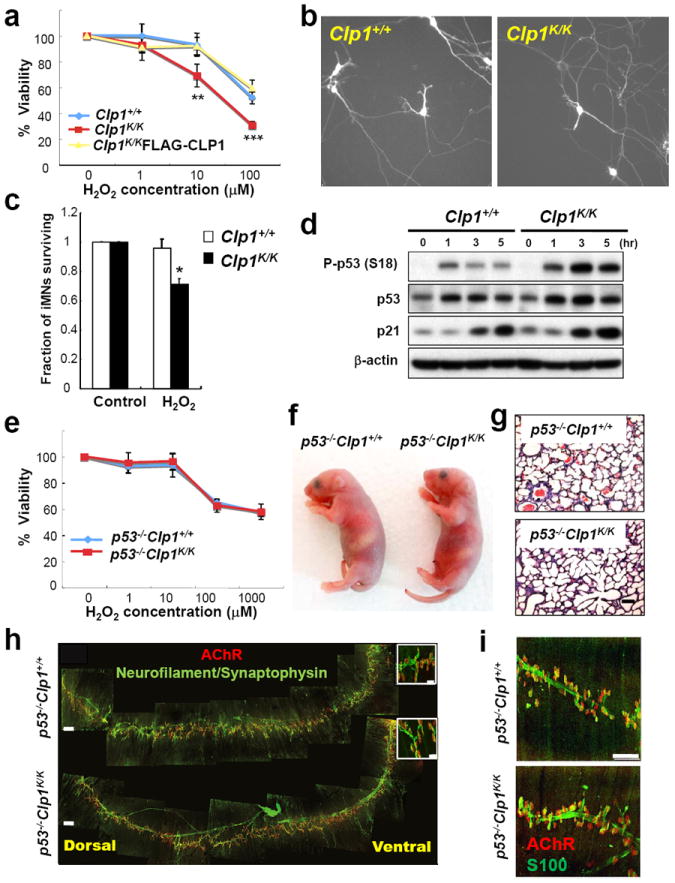

Figure 5. Neonatal lethality and motor neuron loss are mediated via p53.

a, Viability of Clp1+/+,Clp1K/K, and Clp1K/K MEFs rescued with FLAG-tagged wild-type CLP1. Cells were exposed in triplicate to the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 1 hour and mean viability ± S.D. was determined 12 hours later. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (ANOVA). b, Representative images of Hb9-GFP+ trans-differentiated Clp1+/+ and Clp1K/K motor neurons. c, Wild-type and Clp1K/K trans-differentiated motor neurons (iMNs) were treated in duplicate cultures with 100 μM H2O2 or water (control) for 3 hours. Mean survival ± S.D. was scored after 48 hours. *P<0.05 (paired t-test). d, P53 serine-18 phosphorylation in H2O2 treated (100 μM for 1 hour) Clp1K/K and Clp1+/+ primary MEFs. Numbers indicate hours of recovery after stimulation. Timepoint 0 indicates no stimulation. β-actin levels served as loading control. e, Mean viability ± S.D. of p53-/-Clp1+/+ and p53-/-Clp1K/K MEFs challenged in triplicate with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 1 hour. Cell viability was determined 12 hours later. *P<0.05 (t-test). f, General appearance and g, lung structures (H&E) of newborn p53-/-Clp1+/+ and p53-/-Clp1K/K littermates on a C57BL/6 background. Scale bar: 50μm. h, Whole mount immunostaining of the diaphragms of 3 days old p53-/-Clp1+/+ and p53-/-Clp1K/K littermates showing postsynaptic AChR clusters (red, α-Bungarotoxin) and axons and branched presynaptic terminals of the phrenic nerve (green; neurofilament/synaptophysin immunostaining). Scale bar: 250μm; inset: 25μm. i, Whole mount immunostaining of diaphragms of ED18.5 p53-/-Clp1+/+ and p53-/-Clp1K/K littermates showing postsynaptic AChR clusters (red; α-Bungarotoxin) and Schwann cells (green; S100). Scale bar: 75μm.

Extending our studies to neurons, we trans-differentiated wild-type and Clp1K/K MEFs into Hb9-GFP+ motor neurons18 and observed typical sodium and potassium currents, as well as normal action potentials and responses to excitatory and inhibitory transmitters (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 26b-f). However, the resting membrane potential of Clp1K/K motor neurons was depolarized by over 10 mV relative to control motor neurons (-57.0 ± 2.0 mV for n=11 Clp1+/+ and -46.9 ± 3.0 mV for n=10 Clp1K/K motor neurons, t-test < 0.01), suggesting that Clp1K/K motor neurons exhibit ion exchange abnormalities. Cell input resistance was similar between the two groups of neurons (367 ± 94 MΩ for n=11 Clp1+/+ and 511 ± 63 MΩ for n=10 Clp1K/K motor neurons, t-test > 0.2). Importantly, similar to MEFs, trans-differentiated Clp1K/K motor neurons were more sensitive to H2O2-induced cell death than wild type motor neurons (Fig. 5c). Thus, loss of CLP1’s catalytic activity results in enhanced motor neuron death in response to oxidative stress.

Motor neuron loss is mediated via p53

Oxidative stress has been linked to a p53-regulated cell death pathway via serine-18 phosphorylation, shown to regulate p53-dependent transcription19,20,21. In response to H2O2 Clp1K/K MEFs displayed hyperphosphorylation of p53 at serine-18 and increased induction of the p53 target gene p21; re-expression of wild type CLP1 rescued the H2O2-induced serine-18 hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 27a,b). Similarly, we found p53 serine-18 hyperphosphorylation in Clp1K/K MEFs in response to the ROS-inducing agent glucose oxidase but not the DNA-damaging agent camptothecin (Supplementary Fig. 27c,d). Most importantly, genetic inactivation of p53 rescued Clp1K/K MEFs from enhanced death after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 5e). Overexpression of two different tyrosine tRNA fragments in the mouse motor neuron cell line NSC-34 also resulted in enhanced p53 activation in response to H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 28a,b). Thus, kinase-dead CLP1 renders MEFs more susceptible to oxidative stress-induced cell death via a p53-regulated pathway.

Strikingly, we observed a complete rescue of the neonatal lethality in p53-/-Clp1K/K mice on the 100% lethal C57BL/6 background (Fig. 5f). The viable p53-/-Clp1K/K pups exhibited normal extension of the lungs (Fig. 5g), normal innervation of the diaphragm, and rescue of NMJ formation (Fig. 5h,i). The numbers of ChAT (Supplementary Fig. 29a,b) and SMI-32 (not shown) labeled motor neurons in the spinal cord were comparable to that of newborn and one month old control mice. Furthermore, one month old p53-/-Clp1K/K mice did not exhibit muscle weakness (Supplementary Fig. 29c-e). Older p53-/-Clp1K/K mice could not be assessed because they developed tumors due to the loss of p53. To test whether oxidative stress is involved in the phenotype, we treated pregnant Clp1K/+females (crossed to Clp1K/+ males on the lethal C57BL/6 background) with the ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine (NAC). NAC treatment resulted in viable Clp1K/K pups and partially restored innervation of the diaphragm (Supplementary Fig. 30). However, pups from NAC treated mothers died within a week after birth, most likely because in vivo ROS scavenging by NAC might be incomplete and/or other pathways contribute to the phenotype. Thus, ROS and p53 constitute critical in vivo pathways that mediate motor neuronal loss and neonatal death of Clp1K/K mutant mice.

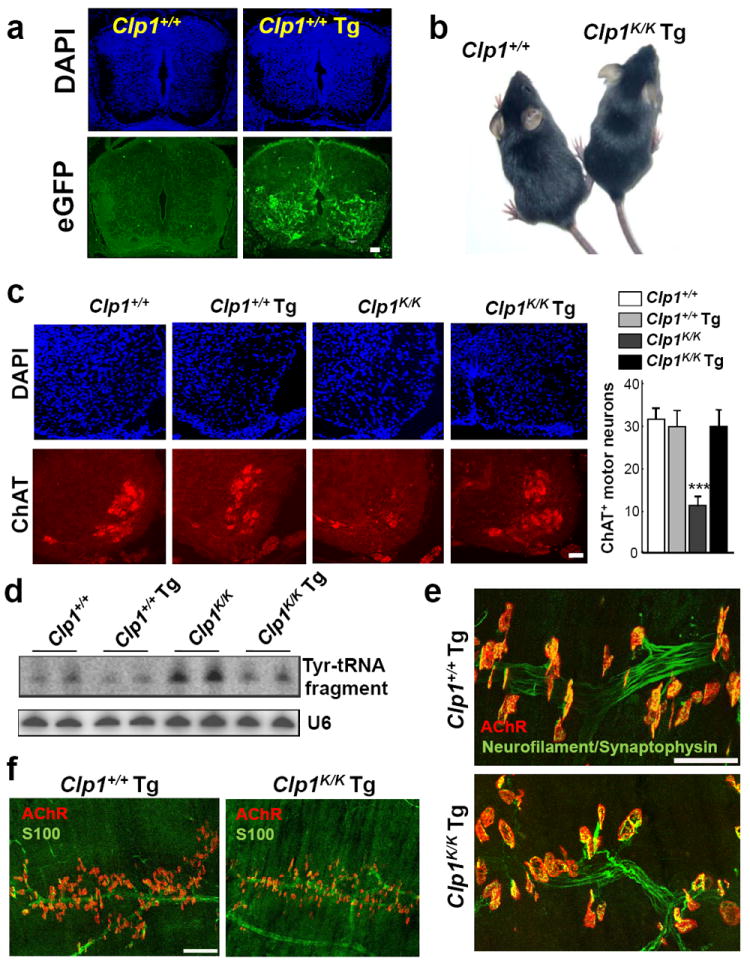

Transgenic rescue of motor neuron defects

To provide definitive proof that the CLP1 kinase-dead mutation indeed acts in motor neurons, we introduced a FLAG-tagged wild type CLP1-IRES-eGFP transgene under the control of the motor neuron promoter Hb922 into control and Clp1K/K mice on a C57BL/6 background (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. 31a,b). Transgenic expression of wild-type CLP1 completely rescued neonatal lethality of Clp1K/K mice and restored normal numbers of ChAT+ motor neurons in the spinal cord of newborns (Fig. 6b,c; Supplementary Fig. 31c). Moreover, Hb9-CLP1 transgenic Clp1K/K mice did not accumulate Tyr-tRNA fragments in the spinal cord (Fig. 6d), providing direct evidence that accumulation of these tRNA fragments is dependent on the loss of CLP1 activity. Phrenic nerve defasciculation and mislocalization, and the defects in NMJ formation and innervations in the diaphragm of Clp1K/K mice were also rescued by transgenic expression of wild type CLP1 in Clp1K/K mice; similar results were obtained for intercostal muscles (Fig. 6e; Supplementary Fig. 32a-c). Moreover, S100+ Schwann cells were restored (Fig. 6f), indicating that the observed absence of terminal Schwann cells is likely due to the impaired function of CLP1 in motor neurons.

Figure 6. CLP1 acts in motor neurons.

a, Cryosections of lumbar (L5) spinal cord from ED14.5 Clp1+/+ and Clp1+/+ Hb9-CLP1 transgenic (Clp1+/+Tg) embryos. Transgene expression was localized by eGFP and anti-GFP antibodies. DAPI counterstaining is shown. b, Appearance of 1 month old Clp1+/+Clp1K/KTg littermates on a C57BL/6 background. c, Immunostaining for ChAT+ (red) motor neurons in the lumbar (L5) spinal cord of newborn Clp1+/+,Clp1+/+Tg, Clp1K/K, and Clp1K/KTg mice on a C57BL/6 background. DAPI staining. Right panel shows mean numbers ± S.D. of ChAT+ motor neurons. n=5 mice per group. ***P < 0.001 (ANOVA). d, Levels of Tyr-tRNA fragments in the spinal cord of Clp1+/+,Clp1+/+Tg, Clp1K/K and Clp1K/KTg mice. Northern blot analyses of total RNA using a probe complementary to the 5’ exon of Tyr-tRNA. U6 RNA served as loading control. e, Whole mount immunostaining depicting NMJs in diaphragms of 3 days old Clp1+/+Tg and Clp1K/KTg littermates. Postsynaptic AChR clusters (red; α-Bungarotoxin) and innervating motor axons and presynaptic nerve terminals (green; neurofilament/synaptophysin immunostaining) are shown. f, Whole mount immunostaining of the diaphragm of 3 days old Clp1+/+Tg, Clp1K/K and Clp1K/KTg littermates showing postsynaptic AChR clusters (red; α-Bungarotoxin) and S100+ Schwann cells (green). Scale bars: a,c,e, 50μm; f, 100μm.

Specific rescue of CLP1 expression in motor neurons but not other cell types led us to test whether kinase-dead CLP1 might affect general metabolism which could then contribute to the observed phenotype. Using calorimetric experiments, Clp1K/KTg mice did not exhibit any apparent alterations in food and water intakes, O2 consumption, CO2 production, respiratory exchange rates, or heat generation as compared to the Clp1+/+Tg littermates; moreover, heat generation upon cold exposure and recovery of body temperature, as a measure for sympathetic nerve activity23, were comparable (Supplementary Fig. 33a-h). These transgenic rescue experiments provide direct evidence that CLP1 acts in lower motor neurons and that mutant CLP1-mediated motor defects are responsible for the neonatal lethality phenotype.

Conclusions

Our results provide the first report on the in vivo function of the RNA kinase CLP1. Strikingly, CLP1 kinase-dead mice develop progressive loss of spinal motor neurons leading to muscle denervation and paralysis. Inactivation of CLP1 kinase activity results at the same time in poor generation of tRNA exon halves and accumulation of novel, hitherto undescribed 5’ leader - exon tRNA fragments. This paradoxical observation could be explained by a defect in tRNA exon ligation in a CLP1 kinase-dead background regulated by oxidative stress. Different tRNA fragments have been previously reported in a variety of organisms24,25. For example, the cytoplasmatic pre-tRNA-derived tRF-1001 fragment, a 3’ trailer molecule, appears to play a role in cell viability26. Stress-induced tiRNAs, derived from the processing of mature tRNAs in the cytoplasm16, inhibit initiation of protein translation by displacing the eIF4F complex from mRNAs17. We did not observe translation inhibition by our novel Tyr-tRNA fragments in metabolic labeling experiments; rather, we found that such fragments sensitize cells to oxidative stress-induced activation of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. The exact molecular mechanism(s) by which these tRNA fragments couple to the p53 pathway need to be determined. Importantly, motor neuron loss was rescued in vivo either by reducing oxidative stress or by genetically inactivating p53.

Our experiments uncover an unexpected mechanistic link between tRNA processing, formation of a new RNA species, and a p53-regulated progressive loss of lower motor neurons. These results provide a conceptual and experimental framework for how alterations in tRNA metabolism can affect spinal motor neurons and might help explain fundamental molecular principles in diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).

Methods Summary

Generation of kinase-dead Clp1K/K and Hb9-CLP1 Tg mice

Complete mutant and knock-in Clp1K/K mice were generated by homologous recombination. The Clp1K/K allele was backcrossed 5 times to C57BL/6 or CBA/J mice. P53-deficient mice and Hb9-GFP transgenic mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Hb9-CLP1 transgenic mice containing the Hb9 promoter driving FLAG-tagged mouse CLP1 and eGFP were generated in-house. All mice were maintained according to institutional guidelines.

Phenotyping

Behavioral phenotyping and assessment of motor functions were performed as described in Supplementary information. Diaphragm and intercostals muscles were stained as described previously27. Anti-neurofilament and anti-synaptophysin antibodies were used to label axons and presynaptic nerve terminals, respectively. Antibodies to S100 were used to visualize Schwann cells. Postsynaptic AChRs were detected with Alexa 594-conjugated α-Bungarotoxin. Spinal Motor neurons were stained with anti-ChAT and anti-SMI-32 antibodies. MEFs and trans-differentiated motor neurons were generated as described18.

Pre-tRNA splicing

Pre-tRNA substrates were generated by in vitro transcription. Labeled yeast pre-tRNAPhe or human pre-tRNATyr were incubated with cell extracts or TEV eluates and formation of mature tRNA and/or tRNA exons monitored by phosphorimaging.

Northern blot analysis

For tRNA detection, total RNA from tissues and cultured cells was isolated, subjected to gel electrophoresis and blotted on Hybond-N+ membranes. Blots were hybridized using [5’ 32P] labeled DNA/LNA probes to detect tyrosine tRNA 5’ and 3’ exons.

Identification of tyrosine tRNA fragments

Total RNA from primary MEFs was separated by gel electrophoresis. The region containing RNA of 37-50 nucleotides in size was excised and sequenced using an Illumina platform. Reads were aligned to the mouse genome (http://gtrnadb.ucsc.edu/Mmusc/Mmusc-by-locus-txt.html) using bedtools (v 2.16.2). The GEO accession number is GSE39275.

Full Methods and associated references are available in Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Meixner, M. Foong, T. Nakashima, H.C. Theussl, J.R. Wojciechowski, A. Bichl, the mouse pathology unit of the UKE, and G.P. Resch for helpful discussions and excellent technical support. We also thank Tilmann Buerckstuemmer for providing the pRV-NTAP vector. J.M.P. is supported by grants from IMBA, the Austrian Ministry of Sciences, the Austrian Academy of Sciences, GEN-AU (AustroMouse), ApoSys, and an EU ERC Advanced Grant. J.M., S.W. and B.M. are supported by IMBA and GEN-AU (AustroMouse). T.H. is supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Astellas foundation. J.K.I. was supported by NIH grant K99NS077435-01A1. M.G. is supported by grants from the DFG (FG885 and GRK 1459), the Landesexzellenzinitiative Hamburg (Neurodapt!). R.H. was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (P19223, P21667). C.J.W. is supported by the NIH (NS038253).

Footnotes

Author contributions. T.H. generated mutant mice, performed mouse phenotyping, and developed cell lines with the help from R.H.. S.W., and B.M. performed all biochemical assays and Northern blots. V. K. performed histological analysis. F.S., H.M., S.C., and A.Y. provided key reagents and technical help for generation of mutant mice. I.T. analyzed tRNA fragment distributions. M.O. performed calorimetric experiments. B.W., J.I., K.E., and C.W. performed and helped with transdifferentiation experiments and patch clamping. R.H. performed immunostainings and assessment of neuromuscular junctions and motor neuron pathfinding. A.M. and A.Y. performed DRG explants cultures and J.R. and R.K. carried out exon arrays. C.B. and M.G. performed histological and immunohistochemical staining of and assessed peripheral nerve and brain structures. J.M. and J.M.P coordinated the project and together wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Information including Supplementary Figures are linked to the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Weitzer S, Martinez J. The human RNA kinase hClp1 is active on 3’ transfer RNA exons and short interfering RNAs. Nature. 2007;447:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nature05777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez A, Shuman S, Schwer B. Human RNA 5’-kinase (hClp1) can function as a tRNA splicing enzyme in vivo. RNA. 2008;14:1737–1745. doi: 10.1261/rna.1142908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain R, Shuman S. Characterization of a thermostable archaeal polynucleotide kinase homologous to human Clp1. RNA. 2009;15:923–931. doi: 10.1261/rna.1492809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries H, et al. Human pre-mRNA cleavage factor II(m) contains homologs of yeast proteins and bridges two other cleavage factors. EMBO J. 2000;19:5895–5904. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minvielle-Sebastia L, Preker PJ, Wiederkehr T, Strahm Y, Keller W. The major yeast poly(A)-binding protein is associated with cleavage factor IA and functions in premessenger RNA 3’-end formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7897–7902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holbein S, et al. The P-loop domain of yeast Clp1 mediates interactions between CF IA and CPF factors in pre-mRNA 3’ end formation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haddad R, et al. An essential role for Clp1 in assembly of polyadenylation complex CF IA and Pol II transcription termination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1226–1239. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghazy MA, et al. The interaction of Pcf11 and Clp1 is needed for mRNA 3’-end formation and is modulated by amino acids in the ATP-binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1214–1225. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paushkin SV, Patel M, Furia BS, Peltz SW, Trotta CR. Identification of a human endonuclease complex reveals a link between tRNA splicing and pre-mRNA 3’ end formation. Cell. 2004;117:311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trotta CR, et al. The yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease: a tetrameric enzyme with two active site subunits homologous to the archaeal tRNA endonucleases. Cell. 1997;89:849–858. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zillmann M, Gorovsky MA, Phizicky EM. Conserved mechanism of tRNA splicing in eukaryotes. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5410–5416. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao C, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A caused by mutation in a microtubule motor KIF1Bβ. Cell. 2001;105:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez-Carbente MR, Castro-Obregon S, Covarrubias L, Narvaez V. Motoneuronal death during spinal cord development is mediated by oxidative stress. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:279–291. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medana IM, Esiri MM. Axonal damage: a key predictor of outcome in human CNS diseases. Brain. 2003;126:515–530. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkin JD, et al. Properties of slow- and fast-twitch muscle fibres in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamasaki S, Ivanov P, Hu GF, Anderson P. Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress-induced translational repression. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:35–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Son EY, et al. Conversion of mouse and human fibroblasts into functional spinal motor neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert PF, Kashanchi F, Radonovich MF, Shiekhattar R, Brady JN. Phosphorylation of p53 serine 15 increases interaction with CBP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33048–33053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.33048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumaz N, Meek DW. Serine15 phosphorylation stimulates p53 transactivation but does not directly influence interaction with HDM2. EMBO J. 1999;18:7002–7010. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao C, et al. Cell type- and promoter-specific roles of Ser18 phosphorylation in regulating p53 responses. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41028–41033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arber S, et al. Requirement for the homeobox gene Hb9 in the consolidation of motor neuron identity. Neuron. 1999;23:659–674. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanada R, et al. Neuromedin U has a novel anorexigenic effect independent of the leptin signaling pathway. Nat Med. 2004;10:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nm1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuck AC, Tollervey D. RNA in pieces. Trends Genet. 2011;27:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurto RL. Unexpected functions of tRNA and tRNA processing enzymes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;722:137–155. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0332-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YS, Shibata Y, Malhotra A, Dutta A. A novel class of small RNAs: tRNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs) Genes Dev. 2009;23:2639–2649. doi: 10.1101/gad.1837609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbst R, Iskratsch T, Unger E, Bittner RE. Aberrant development of neuromuscular junctions in glycosylation-defective Large(myd) mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19:366–378. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.