Abstract

The experience of race-based discrimination may place African American youth at risk for substance use initiation and substance use disorders. This article examines the potential of parental racial socialization—a process by which parents convey messages to their children about race—to protect against the impact of racial discrimination on substance use outcomes. Focusing on stress as a major precipitating factor in substance use, the article postulates several possible mechanisms by which racial socialization might reduce stress and the subsequent risk for substance use. It discusses future research directions with the goal of realizing the promise of racial socialization as a resilience factor in African American and ethnic minority youth mental health.

Keywords: racial socialization; racial discrimination; substance use; stress, African American; mental health; resilience

Recent studies suggest a link between the experience of racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents and young adults (Bennett, Wolin, Robinson, Fowler, & Edwards, 2005; Broman, 2007; Gibbons, Gerard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; Guthrie, Young, Williams, Boyd, & Kintner, 2002). Researchers have long suspected that stress is a motivating factor in the initiation of substance abuse (Leventhal & Clary, 1980; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985; Wills & Shiffman, 1985; Shiffman, 1982), and indeed, the additional stress that African American youth experience as a result of their racial and ethnic minority status may place them at increased risk for substance use and substance use disorders.

In recent years, racial socialization—the process by which parents convey messages about race—has emerged as a “hot topic” in the child and adolescent developmental literature with implications for youth development, particularly for children and adolescents who experience racial discrimination (Hughes, 2003; Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes, & Rowley, 2007; Neblett, White, Ford, Philip, Nguyen, & Sellers, 2008). In this article, we consider the possibility that racial socialization might protect against the risk for substance use and substance use disorders. We conclude with a brief discussion of several important limitations in the extant literature on racial socialization, with an eye toward fulfilling its promise as a factor that can promote the mental and physical health of African American and other ethnic minority youth.

Background and Significance

African American youth have typically reported lower rates of substance use than their White and Hispanic peers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007). Such a pattern does not hold into adulthood, however, when African Americans, as a group, begin to approach, and in some cases even surpass Whites in rates of reported drug use (Herd, 1990; Guthrie et al., 2002). Furthermore, the consequences of drug use, even during adolescence, are often more negative and severe for African Americans. Although African American adolescents report less substance use than their classmates, they experience the highest average number of alcohol-related problems (for example, trouble with teachers because of drinking, driving a car after drinking, or trouble with police because of drinking) (Turner & Wallace, 2003; Wallace, 1999; Welte & Barnes, 1987). African American adolescents are also at increased risk for detention, prosecution, and sentencing for drug offenses when compared to White youth with similar levels of drug use (Belenko, Sprott, & Peterson, 2004; Bishop & Frazier, 1996; Snyder & Sickmund, 2000). These disparities extend into adulthood, with implications for rates of criminal involvement and incarceration (Drug Policy Alliance, 2007), as well as overall health problems such as smoking-related cancers (American Lung Association, 2006), cirrhosis of the liver, hypertension, and birth defects (Boyd, Phillips, & Dorsey, 2003). These alarming consequences highlight the need to be concerned about the development of substance use among African American youth during adolescence and into adulthood.

Stress and Substance Abuse

Stress has emerged as a major contributing factor in the risk for substance abuse (Koob & Le Moal, 1997; Leventhal & Cleary, 1980; Shiffman, 1982; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985; Wills & Shiffman, 1985). According to the stress-coping model of addiction, the use of addictive substances reduces stress, elevates mood, and functions as a reward strategy for daily coping (Shiffman, 1982; Wills & Shiffman, 1985). Chestang (1972) suggested that racial discrimination and the resultant stress might contribute to feelings of worthlessness, inadequacy, and impotence, and lead to the rejection of societal mores and institutions and the acquisition of deviant social behaviors. Along similar lines, Sher (1991) suggested that adolescents at high risk for substance use disorders experience high levels of environmental stress, which, in turn, results in negative feelings such as depression and anxiety and the use of substances to decrease these feelings. Although there are still questions about the causal order, underlying mechanisms, and strength of the association between stress and substance use, there is sufficient evidence to support the idea that stress acts as a precipitating factor for substance use in the general population (Kaplan & Johnson, 1992; Laurent, Catanzaro, & Kuenzi, 1997; Newcomb & Harlow, 1986; Sinha, 2001).

In addition to the generic, everyday stressors associated with the various developmental tasks of adolescence, African American adolescents may experience even higher levels of stress because of their ethnic minority status. Race-based discrimination increases as African American adolescents become more autonomous and interact with individuals and institutions that may discriminate against them (Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000; Hughes et al., 2006). Not surprisingly, observational and self-report data suggest that race-based discrimination experiences are not uncommon for a majority of African American adolescents (Fisher et al., 2000; Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006). Adding insult to injury, the impact of life events and daily microstressors is further exacerbated for African American adolescents by chronic factors that increase the risk for substance abuse. For example, Black adolescents are more likely than White and Hispanic youth to live in low-income neighborhoods (Anderson, 1990; Jargowsky, 1997; Wilson, 1987), where adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the initiation of drug use (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2007) and where drug use and drug-related problems are often more prevalent (Galea & Vlahov, 2002; Smart, Adlaf, & Walsh, 1994; Wallace, 1999).

Race-Based Discrimination and Substance Use Outcomes

Consistent with the literature linking stress to substance use, a small but growing number of studies reports a relation between perceived race-based discrimination and substance use outcomes (Bennett et al., 2005; Gibbons et al., 2004; Guthrie et al., 2002). One such study, conducted with 105 Black adolescent girls between the ages of 11 and 19, found that 52% of girls (N = 55) reported experiencing racial discrimination. Their perceptions of discrimination were strongly associated with their smoking habits, and the relation between racial discrimination and smoking was partially mediated by stress (Guthrie et al., 2002). In a sample of African American college students with a mean age of 20 years old, Bennett and colleagues (2005) found that even when adjusting for age, gender, living on campus, grades, occupational status, and age of first tobacco use, participants who reported racial and ethnic harassment were twice as likely to engage in self-reported daily tobacco use (odds ratio = 2.01; 95% confidence interval = 1.94, 2.08). Finally, in a prospective study of 897 families, each with a child between the ages of 10 and 12, Gibbons et al. (2004) reported that children's experiences of discrimination were associated with their current and future substance use, children's friends' use, and children's views on risk-taking at baseline. Together, these studies provide compelling preliminary evidence of the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and substance use. In the following sections, we consider racial socialization's potential to protect against the negative influence of race-based discrimination on substance use outcomes.

Racial Socialization and Positive Youth Outcomes

Racial socialization is the process of teaching children about their race and ethnicity and raising awareness of racism and discrimination, with the ultimate goal of promoting racial identity and preparing ethnic minority youth to succeed in the face of racial bias and adversity (Bowman & Howard, 1985; Boykin & Toms, 1985; Peters, 1985; Phinney & Chavira, 1995; Stevenson, 1994). Although youth receive messages about race and ethnicity from a number of sources, the messages that parents give tend to be the focus of studies and research investigations. Primary racial socialization themes include racial pride/cultural socialization, messages that promote pride in the history and culture of one's race; racial barriers/preparation for bias, messages that highlight the existence of inequalities between African Americans and other groups; egalitarian messages that emphasize equality between the races; and self-development/self-worth, messages that promote feelings of individual worth within the broader context of the child's race (Bowman & Howard, 1985; Hughes et al., 2006). Racial socialization researchers have also suggested that promotion of mistrust, messages that promote wariness in interracial reactions (Hughes et al., 2006); negative messages that reinforce societal stereotypes about African Americans; racial socialization behaviors, race-related activities that convey messages about race (Neblett et al., 2008); and even silence about race (Hughes et al., 2006; Neblett et al, 2008) are other important ways in which parents socialize their children about race. Together, these messages act in concert to convey messages about race with implications for critical adolescent developmental outcomes (Coard & Sellers, 2005; Hughes et al., 2006).

The positive effects of racial socialization have been found to include higher self-esteem (Constantine & Blackmon, 2002; Harris-Britt et al., 2007), grades, and self-efficacy (Bowman & Howard, 1985); increased group knowledge and favorable in-group attitudes (Knight, Cota, & Bernal, 1993); increased academic motivation and performance (Neblett, Philip, Cogburn, & Sellers, 2006; Neblett, Chavous, Nguyên, & Sellers, 2009); decreased fighting (Stevenson, Herrero-Taylor, Cameron, & Davis, 2002); and overall resilience (Brown, 2008), to name a few. Furthermore, a handful of studies provide evidence that racial socialization processes buffer the negative effects of racial discrimination on psychological adjustment (Bynum, Burton, & Best, 2007; Fischer & Shaw, 1999; Neblett et al., 2008) and enhance coping with perceived discriminatory experiences (Scott, 2004). Fischer and Shaw (1999), for example, found that messages about racial barriers buffered the impact of racist events on African American adults' mental health. In a sample of African American adolescents, Neblett and colleagues (2008) found that a pattern of racial socialization characterized by high racial pride, high self-worth, racial barrier messages, and socialization behaviors appeared to buffer the negative impact of racial discrimination on perceived stress and problem behaviors. Finally, in a study to examine the relation of background and race-related factors to coping with racial discrimination, African American adolescents whose parents delivered more frequent messages about racism felt more control over discriminatory experiences, and employed coping strategies such as self-reliance, problem solving, and seeking social support (Scott, 2004). The relations among racial socialization, coping, psychological adjustment, and several of the developmental outcomes we have noted here provide initial clues about how racial socialization might act as a resilience factor against the impact of racial discrimination on substance use outcomes. Accordingly, we now consider possible mechanisms by which racial socialization might confer such an effect.

Racial Socialization as a Protective Factor in the Context of Substance Use Outcomes

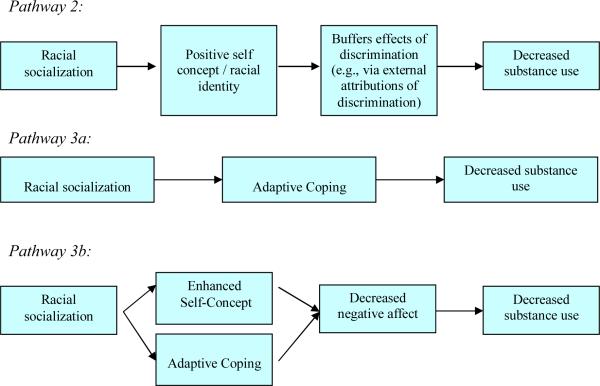

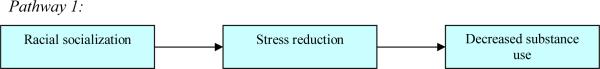

If stress plays a major role in whether people start or continue to abuse substances, there are several ways that racial socialization might help African American adolescents who experience racial discrimination (see Figure 1). For example, racial socialization might directly reduce stress, in effect serving the function of potentially addictive substances and reducing the likelihood that African American adolescents might use them (Pathway 1). Bynum and colleagues (2007) found that cultural pride messages predicted less distress in a sample of African American late adolescents. Similarly, Neblett and colleagues (2008) found that adolescents whose parents emphasized racial pride, self-worth, racial barriers, and egalitarian messages together with racial socialization behaviors reported the lowest levels of perceived stress, whereas adolescents whose parents said little about being African American or emphasized negative messages about race reported the highest levels of perceived stress.

Figure 1.

Plausible Pathways of Protection by Racial Socialization Against the Impact of Discrimination on Substance Use.

Racial socialization might also convey protective effects in this context by enhancing adolescents' self-concept (Pathway 2). If, as Chestang (1972) suggests, race-based stress contributes to decreased self-concept, leading to the acquisition of deviant social behaviors, the positive effects of racial socialization practices emphasizing racial pride, racial barriers, and egalitarian messages about self-efficacy and self-esteem (Bowman & Howard, 1985; Constantine & Blackmon, 2002; Harris-Britt et al., 2007) could help prevent this downward spiral. Messages that emphasize racial pride and self-worth might provide African American adolescents with the personal esteem scaffolding necessary to counteract the disparaging messages (explicit and otherwise) they receive about being African American. Similarly, racial barrier messages might help youth to correctly attribute unfair treatment to external sources, thus cushioning or short-circuiting the blow to self-esteem that might otherwise occur. Racial socialization practices might also enhance African American adolescents' self-concept by increasing their sense of racial identity (Demo & Hughes, 1990; Hughes, Witherspoon, Rivas-Drake, & West-Bey, 2009; Sanders Thompson, 1994; Neblett, Smalls, Ford, Nguyên, & Sellers, 2009; Stevenson & Arrington, 2009). The significance of race to an individual's self concept, in and of itself, is a protective factor against the deleterious effects of racial discrimination on psychological problems such as depression and anxiety in African American late adolescents (e.g., Neblett, Sellers, & Shelton, 2004; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003).

A third way in which racial socialization might reduce stress and subsequent substance use focuses on coping (Pathway 3a). The links among racial socialization messages, perceived control, and approach coping strategies (Scott, 2004) suggest that adolescents whose parents actively engage their children on the topic of race might be more likely to employ strategies such as self-reliance, problem solving, and seeking social support, to the exclusion of more maladaptive coping strategies observed in adolescents who experiment with drugs (Wills et al., 1996). The use of more adaptive coping strategies, particularly in the context of race-based discrimination, might help to modulate both the level and impact of stress that African American youth experience, in turn decreasing the likelihood of regular substance use abuse. Moreover, the enhanced self-concept and adaptive coping strategies that racial socialization conveys might operate together to decrease negative affect such as depression and anxiety, resulting in lower substance use and risk for disorder (Pathway 3b).

Future Directions

Although we have focused on substance use in this article, we believe that racial socialization holds promise as a resilience factor for a broad range of youth mental health issues. In fact, the study of racial socialization processes in the United States is particularly timely given the election of President Obama, the United States' first Black president. Will historical context shape the ways in which parents convey messages about race, and will these messages have implications for substance use and other mental health outcomes? In addition to the study of racial socialization processes in African American youth, we anticipate that some of the hypothesized mechanisms underlying the protective effects of racial socialization might apply to other ethnic and/or immigrant groups in the United States and beyond who experience discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, religious orientation, and/or immigration status. For example, it may be that how parents socialize their children regarding the significance and meaning of being a religious minority or having immigrant status might change how discrimination affects youth developmental outcomes.

The literature on racial socialization continues to grow and takes into account factors such as historical context and the potential benefits of parental socialization for ethnic minorities and all youth who experience discrimination on the basis of social status, but several concerns remain. First, the direction of associations between racial socialization and developmental outcomes is not yet entirely clear. We do not know, for example, whether racial socialization leads to positive psychological adjustment, whether youth psychological health influences how parents communicate with their children about race, or some combination of the two. Second, most racial socialization studies have examined parental racial socialization (primarily from the youth's perspective) to the exclusion of other important sources such as peers, other adults, and media. Future studies will need to include accounts of racial socialization from children, parents, and other socialization agents who play a role in shaping youths' views about race. Peers may be especially important to consider given their increasing importance to development as youth age and go through adolescence. A third consideration is the need for studies to examine racial socialization in the context of other parenting variables, such as parenting style and parental support (e.g., Cooper & Smalls, 2010; Smalls, 2009; Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006). Without testing the additive and joint impacts of racial socialization and other parenting behaviors, it is difficult to ascertain whether the effects of racial socialization are due to the messages themselves or to other aspects of the parent-child relationship. Experimental designs offer one possible solution to addressing this and other interpretational shortcomings; however, such approaches (such as random assignment strategies) would require careful consideration of ethical guidelines and principles in the study design. Finally, a number of person-centered approaches to racial socialization have emerged within the last two years (e.g., Neblett et al., 2008, Neblett et al., 2009; White, Ford, & Sellers, in press). In contrast to studies that focus explicitly on the independent content of specific socialization messages, these studies examine profiles of parental racial socialization messages and behaviors. Such approaches are desirable because they examine racial socialization behaviors as a whole, acknowledge that parents rarely give a single type of racial socialization message, and reflect a more accurate picture of how racial socialization processes operate to influence youth development.

Conclusion

In this brief article, we have argued that racial socialization may prove to be a useful resilience factor against the impact of racial discrimination on adolescents' substance use. Racial socialization processes may directly and indirectly reduce precipitating factors such as stress and mitigate detrimental correlates of substance use such as maladaptive coping and poor self-concept. These processes may counteract the crescendo of racial discrimination youth encounter as they negotiate adolescence, and potentially play a role in disrupting the oft-cited, harmful “catch-up” phase that seems to take place between adolescence and adulthood for African American youth. At present, the proposed mechanisms by which racial socialization may be beneficial are largely untested, and future research will need to explore the benefit of racial socialization against the impact of race-related stress on substance use as well as other important adolescent developmental outcomes. Such work will continue to play an instrumental role not only in African American adolescent mental health interventions but also in mental health and social services delivery for other ethnic minority children and adolescents as well as non-ethnic minority youth who experience discrimination.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported with funding from the Duke Endowment and a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1 P20 DA017589), awarded to the Duke University Transdisciplinary Prevention Research Center.

References

- American Lung Association: Epidemiology and Statistics Unit Research and Program Services Trends in lung cancer morbidity and mortality. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Street wise: Race, class, and change in an urban community. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Sprott JB, Peterson C. Drug and alcohol involvement among minority and female juvenile offenders treatment and policy issues. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2004;15:3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GG, Wolin KY, Robinson EL, Fowler S, Edwards CL. Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:238–240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D, Frazier C. Race effects in juvenile justice decision-making: Findings of a statewide analysis. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 1996;86:392–414. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ, Howard C. Race-related socialization, motivation, and academic achievement: A study of Black youths in three-generation families. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:134–141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd MR, Phillips K, Dorsey CJ. Alcohol and other drug disorders, comorbidity, and violence: comparison of rural African American and Caucasian women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2003;17:249–258. doi: 10.1053/j.apnu.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW, Toms FD. Black child socialization. In: McAdoo HP, McAdoo JL, editors. Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Race, drug use, and risky sexual behavior. College Student Journal. 2007;41:999–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL. African American resiliency: Examining racial socialization and social support as protective factors. Journal of Black Psychology. 2008;34:32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum MS, Burton ET, Best C. Racism experiences and psychological functioning in African American college freshmen: Is racial socialization a moderator? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:64–71. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55:SS–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chestang L. Character development in a hostile environment. University of Chicago, School of Social Service Administration; Chicago: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Coard SI, Sellers RM. African American families as a context for racial socialization. In: McLoyd V, Hill N, Dodge K, editors. Emerging issues in African-American family life: Context, adaptation, and policy. Guildford; New York: 2005. pp. 264–284. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine MG, Blackmon SM. Black adolescents' racial socialization experiences: Their relations to home, school, and peer self-esteem. Journal of Black Studies. 2002;32:322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper SM, Smalls CP. Culturally distinctive and academic socialization: Direct and interactive relationships with African American adolescents' academic adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(2):199–212. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demo DH, Hughes M. Socialization and racial identity among Black Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1990;53:364–374. [Google Scholar]

- Drug Policy Alliance Race and the drug war. 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007, from http://www.drugpolicy.org/communities/race/

- Fischer AR, Shaw CM. African Americans' mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: The moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: Socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Reports. 2002;117:135–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(4):517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie BJ, Young AM, Williams DR, Boyd CJ, Kintner EK. African American girls' smoking habits and day-to-day experiences with racial discrimination. Nursing Research. 2002;51:183–190. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, Rowley SJ. Perceived racial Discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Subgroup differences in drinking patterns among Black and White men: Results from a National Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1990;51:221–232. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents' messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(1/2):15–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson H, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic/racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Witherspoon D, Rivas-Drake D, West-Bey N. Received ethnic-racial socialization messages and youths' academic and behavioral outcomes: Examining the mediating role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(2):112–124. doi: 10.1037/a0015509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jargowsky PA. Ghettos, barrios, and the American city. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2007. 2006. NIH Publication No. 07-6202. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB, Johnson RJ. Relationships between circumstances surrounding initial illicit drug use and escalation of use: Moderating effects of gender and early adolescent experiences. In: Glantz M, Pickens R, editors. Vulnerability to drug abuse. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1992. pp. 299–358. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Cota MK, Bernal ME. The socialization of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic preferences among Mexican American children: The mediating role of ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1993;15:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug Abuse: Hedonic Homeostatic Dysregulation. Science. 1997;278:52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, Kuenzi CM. Stress and alcohol related expectancies and coping preferences: A replication with adolescents of the Cooper et al. (1992) model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:644–651. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Cleary PD. The smoking problem: A review of the research and theory in behavioral risk modification. Psychology Bulletin. 1980;88:370–405. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse Drugs, Brain, and Behavior – The Science of Addiction. 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007, from http://www.National Institute on Drug Abuse.nih.gov/scienceofaddiction/strategy.html.

- Neblett EW, Jr., Chavous TM, Nguyên HX, Sellers RM. Say it loud – I'm Black and I'm proud: Parents' messages about race, racial discrimination, and academic achievement in African American boys. Journal of Negro Education. 2009;78(3):246–259. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr., Philip CL, Cogburn CD, Sellers RM. African American adolescents' discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32(2):199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr., Shelton JN, Sellers RM. The role of racial identity in managing daily hassles. In: Philogene G, editor. Race and identity: The legacy of Kenneth Clark. American Psychological Association Press; Washington, DC: 2004. pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr., Smalls CP, Ford KR, Nguyên HX, Sellers RM. Racial socialization and racial identity: African American parents' messages about race as precursors to identity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(2):189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr., White RW, Ford KR, Philip CL, Nguyen HX, Sellers RM. Patterns of racial socialization and psychological adjustment: Can parental communications about race reduce the impact of racial discrimination? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18(3):477–515. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Harlow LL. Life events and substance use among adolescents: Mediating effects of perceived loss of control and meaninglessness in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:564–577. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF. Racial socialization of young Black children. In: McAdoo HP, McAdoo JL, editors. Black children: Social, educational and parental environments. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Chavira V. Parental ethnic socialization and adolescent coping with problems related to ethnicity. Journal of Research on Adolescents. 1995;5:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Thompson VL. Variables affecting racial-identity salience among African Americans. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;139:748–761. doi: 10.1080/00224549909598254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD. Correlates of coping with perceived discriminatory experiences among African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone K, Zimmerman MA. The role of racial identity and racial discrimination in the mental health of African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. Racial identity, discrimination, and mental health among African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Relapse following smoking cessation: A situational analysis. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:71–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalls C. African American adolescent engagement in the classroom and beyond: The roles of mother's racial socialization and democratic-involved parenting. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:204–213. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart R, Adlaf E, Walsh G. Neighbourhood socio-economic factors in relation to student drug use and programs. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1994;3:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H, Sickmund M. Juvenile offenders and victims: 1999 national report. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC. Racial socialization in African-American families: The art of balancing intolerance and survival. Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families. 1994;2:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC. Racial/Ethnic socialization mediates perceived racism and the racial identity of African American adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(2):125–136. doi: 10.1037/a0015500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Herrero-Taylor T, Cameron R, Davis GY. “Mitigating instigation”: Cultural phenomenological influences of anger and fighting among “Big-Boned” and “Baby-faced” African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31(6):473–485. [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner WL, Wallace B. African American substance use: Epidemiology, Prevention, and Treatment. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:576–589. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM. The social ecology of addiction: Race, risk, and resilience. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1122–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte JW, Barnes GM. Alcohol use among adolescent minority groups. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1987;48:329–336. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RL, Ford KR, Sellers RM. Parental racial socialization profiles: Association with demographic factors, racial discrimination, childhood socialization, and racial identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0016111. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Shiffman S. Coping and substance abuse: A conceptual framework. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA, editors. Coping and substance use. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1987. [Google Scholar]