Synopsis

Objective

This study was designed to examine whether African American and European American mothers differ in their discipline use when reasoning, denying privileges, yelling, and spanking are considered simultaneously and whether there are ethnic group differences in how these four forms of discipline are associated with child externalizing behavior.

Design

Structural equation models were used to examine relations between children's externalizing behavior in kindergarten (age 5), mothers' discipline in grades 1-3 (ages 6-8), and children's externalizing behavior in grade 4 (age 9) in a sample of 585 mothers and children.

Results

African American and European American mothers showed the same rank order frequency of reported use of each of the four forms of discipline, most frequently using reasoning, followed by yelling, denying privileges, and least frequently spanking. However, European American mothers more frequently reported using three of the four forms of discipline than did African American mothers, with no ethnic differences in the frequency with which mothers reported spanked. For European American children, higher levels of teacher-reported child externalizing in kindergarten predicted mothers' more frequent report of denying privileges, yelling, and spanking in grades 1-3; only spanking was associated with more child externalizing behaviors in grade 4. For African American children, teacher-reported child externalizing in kindergarten was unrelated to mothers' report of discipline in grades 1-3; considering predictions from discipline to grade 4 child externalizing, only denying privileges was predictive.

Conclusions

European American and African American families differ in links between children's teacher-reported externalizing behaviors and subsequent mother-reported discipline as well as links between mother-reported discipline and children's subsequent teacher-reported externalizing.

Introduction

Managing children's behavior is one of the key responsibilities of parents. Proactive strategies such as teaching the child how to get along with others and setting clear expectations regarding good behavior are important in promoting children's behavioral adjustment. Regardless of how successful parents are at preventing misbehavior before it occurs, children will misbehave at times, and parents are faced with decisions regarding how to respond to their children's misdeeds. Over time, parents likely use a variety of strategies, some of which may have the intended effect of decreasing children's subsequent misbehavior. Other strategies may have the unintended consequence of increasing children's subsequent misbehavior. Still other strategies may exert no effect. Simultaneously examining different key discipline strategies offers the advantage of promoting understanding of how they operate in relation to children's problem behavior.

Previous studies suggest the utility of adopting a profile approach in understanding parenting behaviors. Baumrind's (1967, 1991) classic work on parenting types provides an early example of the kind of knowledge that can be gained from examining parenting behavior not as discrete elements but as part of a profile in conjunction with a range of other parenting behaviors. Parents' discipline strategies can be conceptualized along a number of dimensions (Gershoff et al., 2010). One key distinction is whether the discipline is physical or nonphysical. If the discipline is nonphysical, it may involve purely verbal techniques (either positive or negative) or also the manipulation of privileges (e.g., time-outs, removing privileges). Research that has used cluster analyses to identify groups of parents who are differentiated by their attitudes and use of physical and nonphysical discipline has found that physical and nonphysical forms of discipline often cluster together (Thompson et al., 1999). Examining profiles of parenting is especially useful because it can suggest ways in which specific parenting behaviors may have different relations with children's adjustment depending on other parenting behaviors that co-occur.

Ethnic Differences in Discipline

Research to date suggests that African American and European American parents may differ in the frequency with which they use several types of discipline strategies, although corporal punishment has received the most attention. For example, Day, Peterson, and McCracken (1998) examined the number of times during the past week that a parent reported using corporal punishment for the target child. African American mothers said they spanked more frequently than European American mothers for older children, but only single African American mothers said they spanked more frequently for younger children. However, this analysis did not control for other factors (e.g., age, income, education) that may have accounted for the difference between groups. Straus and Stewart (1999) used data from the Gallup Organization to assess a variety of forms of corporal punishment that parents reported using during the previous year. After controlling for socioeconomic status (SES) and other demographic variables, they found that African American parents were more likely than European American parents to use corporal punishment. However, among parents who used corporal punishment, there was no difference in frequency of its use between European American and African American parents. Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, a nationally representative sample that over-sampled poor and minority families, Bradley, Corwyn, McAdoo, and Garcia Coll (2001) found that African American parents reported that they would use spanking more than European American parents for hypothetical situations, but found no differences between African American and European American parents in reported use with their own child or observed use.

With respect to discipline other than corporal punishment, Heffer and Kelley (1987) examined mothers' acceptance of a variety of nonphysical discipline strategies and found that low-income African American mothers were less accepting of positive reinforcement (e.g., praise) for appropriate behavior and time-out for inappropriate behaviors than were more affluent African American mothers or European American mothers. Similarly, Bradley et al. (2001) found that African American parents were less likely than European American parents to use verbal strategies (e.g., discussion or praise), ignoring, or time-out to manage their children's behavior. These conclusions are more consistent across studies for poor African American families than nonpoor African American families, highlighting the necessity of examining variables such as income and education that are correlated with ethnicity in the United States and that may account for differences in parental use of discipline.

Links between Discipline and Child Adjustment

One of the key controversies in the parenting literature is the extent to which a given parenting behavior has the same or different effects on children's adjustment depending on the cultural context in which it is administered (Bornstein & Lansford, 2010). In the case of parents' discipline strategies, one argument has been that the relation between a particular discipline strategy and a child's adjustment will depend, in part, on the normativeness of that discipline strategy in the child's cultural group (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Lansford et al., 2005). It might be that ethnic differences in average levels of the discipline variables are also accompanied by ethnic differences in the relation between discipline and adjustment. It is also possible that one would find no differences between groups in relations between discipline use and children's adjustment. Two hypotheses make different predictions regarding how discipline should operate across different ethnic groups. The “similar processes” hypothesis (e.g., Rowe, 1997) predicts that the relation between parental use of discipline and child externalizing is the same across ethnic groups. The “different processes” hypothesis (e.g., Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996) predicts that the relation between parental use of discipline and child externalizing may be different across ethnic groups, depending on the meaning of the discipline across groups. Clearly, there are many complex issues involved in understanding issues of ethnicity in relation to parenting (McLoyd & Steinberg, 1998). For example, different ethnic groups may show similar mean levels of a given discipline practice and similar correlations between discipline and externalizing, similar mean levels of discipline but different correlations between discipline and externalizing, different mean levels of discipline but similar correlations between discipline and externalizing, or different mean levels of discipline and different correlations between discipline and externalizing (McLoyd & Steinberg, 1998).

Evidence regarding these links has been mixed for corporal punishment and is largely unavailable for other forms of discipline. Some studies suggest that corporal punishment statistically predicts externalizing behavior problems for European American children but not for African American children (e.g., Deater-Deckard et al., 1996). Other studies suggest that corporal punishment predicts externalizing behavior problems for both European American and African American children (e.g., Berlin et al., 2009). In part, differences in findings across studies may be accounted for by sample differences such as children's age or SES, controls included in analyses, specific measures used, and the reporter. For example, youth reports of their parents' corporal punishment are sometimes less strongly associated with aggression than are parents' reports of their corporal punishment, and ethnic differences have been found more frequently when teachers or peers report on externalizing outcomes than when mothers report on the outcomes (e.g., Benjet & Kazdin, 2003; Gunnoe & Mariner, 1997). Furthermore, because low SES (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2006), family stress (McLoyd, 1990), and single parent status (McAdoo, 2002) are more prevalent among African American than European American families and because these sociodemographic risk factors have all been found to relate to more harsh discipline (Dodge, McLoyd, & Lansford, 2005), studies that do not account for these potential confounds might misattribute differences in discipline to ethnicity rather than other aspects of sociodemographic risk. There remains considerable controversy regarding whether there are ethnic differences in links between corporal punishment and child adjustment.

Fewer studies have been devoted to understanding ethnic differences and similarities in links between nonphysical forms of discipline and children's adjustment. In one exception, Snyder, Cramer, Afrank, and Patterson (2005) used direct observation of parent-child interaction tasks to examine the relation between maternal ineffective discipline and child conduct problems in an ethnically diverse sample. They found that child conduct problems longitudinally (i.e., from pre-kindergarten to first grade) predicted increases in parental ineffective discipline and that ineffective discipline longitudinally predicted increases in child conduct problems. However, the interaction between ethnicity and discipline was not specifically examined, and the study used a composite discipline score that included inconsistency, reliance on threats, commands, scoldings, and use of corporal punishment as part of their ineffective discipline construct, so it is unclear to what extent nonphysical versus physical forms of discipline contributed to the findings.

The Present Study

The present study addressed three primary research questions. First, do African American and European American mothers differ in the frequency with which they use reasoning, denying privileges, yelling, and spanking? Second, are ethnic differences in discipline use accounted for by demographic characteristics that often are confounded with ethnicity (SES, stress, and single caregiver status) rather than ethnicity per se? Third, within ethnic group, are differences in the discipline used by mothers associated with differences in subsequent child externalizing, controlling for prior externalizing? We hypothesized that African American and European American mothers would differ in the discipline that they used, that these differences would persist after controlling for potential confounds, and that discipline would be associated differentially with externalizing behavior for African American and European American children.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were recruited in 1987 and 1988 from Nashville and Knoxville, TN, and Bloomington, IN, for the Child Development Project (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990), a multi-site, longitudinal study. Parents were approached and asked to participate at the time of their child's kindergarten preregistration (when the average age of the children was 5 years). Approximately 75% of parents approached agreed to participate in the study, for a total of 585 families. Of these families, 97 were African American and 477 were European American; the remaining 11 families were of other ethnic origin and were not included in the present study.

Mothers, or female heads of household, were interviewed at the initial assessment to determine family demographic characteristics. Across the entire sample of the 574 African American and European American families, 48% of the target children were female, 26% of households were headed by single parents, and the mean age of mothers at the time of the initial assessment was 31.7 years, SD = 5.12. Family SES was determined based on the Hollingshead (1979) Four-Factor Index (i.e., mother's years of education, mother's occupation, father's years of education, and father's occupation). Mothers' data were double-weighted for families in which fathers or adult male partners were not living in the home. All five Hollingshead classifications of SES were represented across the sample, with percentages from the lowest SES to highest SES category as follows: 8.3% in category 5, 18% in category 4, 25.2% in category 3, 32.1% in category 2, and 16.4% in category 1. At the time of the initial assessment, mothers also provided a rating of family stress in each of two eras (child age 1-4 and child age 4-5); these ratings were averaged to provided a measure of family stress in the child's first 5 years of life (1 = minimal stress; 5 = severe, frequent stress). Data were collected annually through fourth grade (when children were 9 years old); fourth-grade data were available for 80% of the original participants. Participants who provided data in fourth grade did not differ from nonparticipants on ethnicity, family composition, or child gender. However, children whose teachers did not report on their fourth-grade externalizing were more likely to be from lower-SES families. Mothers provided written informed consent at each time point, and IRBs at each participating university approved the research protocol.

Measures

Discipline

When children were in first, second, and third grade, their mothers completed a questionnaire rating the frequency with which they used a variety of discipline strategies during the past year (0 = never, 1 = less than once a month, 2 = about once a month, 3 = about once a week, and 4 = about every day). Four discipline scales were constructed by averaging a single item in each scale across the three years to create reliable, cross-age composites and to make use of data available from participants even if they provided discipline data only in one year: (1) “Talk and explain reasons” (α = .71); (2) “Deny privileges (e.g., no TV, no candy, etc.)” (α = .75); (3) “Yell, scold, or raise voice” (α = .80); (4) “Spank with hand” (α = .75).

Externalizing behavior

Teachers completed the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, 1991) during the winter or spring of the target child's kindergarten and fourth-grade school years. The TRF consists of items that are rated by teachers as either 0 (problem statement not true of child), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true of child), or 2 (very true or often true of child). The externalizing scale consisted of 34 items (e.g., argues a lot, demands attention, gets in many fights, lies or cheats). Raw item scores were summed to form teacher-reported scale scores in each year (αs > .90 for both years).

Analytic Approach

Multivariate analysis of covariance was used to examine whether African American and European American mothers differ in the frequency with which they reported they used each of the four forms of discipline. Hierarchical regressions were then conducted to examine whether ethnicity predicts use of these types of discipline, above and beyond prior externalizing and sociodemographic control variables. Finally, we tested multi-group structural equation models to examine associations among kindergarten externalizing, discipline in grades 1-3, and grade 4 externalizing, as well as whether these associations held for both African American and European American children.

Results

Ethnic Differences in Discipline Frequency

We first conducted multivariate analysis of covariance on the four discipline scales (i.e., reason, deny privileges, yell, spank) to determine whether African American and European American mothers differed in the pattern with which they reported using the discipline approaches in grades 1-3, controlling for children's externalizing behaviors in kindergarten. The multivariate test was significant, Pillai's F(4, 506) = 21.90, p < .001. Descriptive statistics, follow-up univariate tests, and effect sizes are presented in Table 1. As shown, European American mothers reported they reasoned, denied privileges, and yelled more frequently than did African American mothers; European American and African American mothers did not differ in the frequency with which they spanked.1 Furthermore, Levene's test for the homogeneity of the variances suggested that the variance was larger for African American than European American mothers' use of three of the four forms of discipline (reasoning, yelling, and spanking, but not denying privileges). However, despite these differences in the frequency and variance, the rank order with which European American and African American mothers used the four forms of discipline was identical, with reasoning used most frequently, followed by yelling, denying privileges, and spanking used least frequently.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Tests of Ethnic Differences in Frequency of Discipline.

| European American | African American | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discipline | M (SD) | M (SD) | F(1, 509) | Cohen's d |

| Reason | 3.30 (.66) | 2.58 (1.00) | 70.80*** | .85 |

| Deny privileges | 1.73 (.87) | 1.50 (.95) | 5.23* | .25 |

| Yell | 2.66 (.89) | 2.01 (1.29) | 33.19*** | .59 |

| Spank | 1.18 (.82) | 1.32 (.96) | 2.44 | .16 |

Note. Analyses control for child externalizing in kindergarten.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Prediction of Discipline by Ethnicity and Other Demographic Variables

Although the previous analyses suggest that African American and European American mothers in this sample differed in the frequency with which they used the four discipline approaches in grades 1-3, other variables associated with ethnicity may better account for these differences. Bivariate correlations between ethnicity, child gender, SES, stress, single caregiver status, child externalizing, and the four discipline approaches were computed (see Table 2). Compared with European American children, African American children were more likely to live in households with lower SES, higher stress, and a single caregiver. Teacher-reported child externalizing in kindergarten and in grade 4 were positively correlated with mothers' denying privileges and spanking in grades 1-3. All forms of discipline were positively correlated with each other.

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ethnicitya | -- | |||||||||

| 2. Genderb | .03 | -- | ||||||||

| 3. SES | −.40* | −.05 | -- | |||||||

| 4. Stress | .13* | .01 | −.22* | -- | ||||||

| 5. Caregiverc | .32* | .06 | −.37* | .32* | -- | |||||

| 6. Ext K: T | .07 | −.14* | −.24* | .12* | .16* | -- | ||||

| 7. Reason | −.34* | −.14* | .27* | .04 | −.13* | .04 | -- | |||

| 8. Deny privileges | −.10* | −.09* | .05 | .12* | −.01 | .16* | .42* | -- | ||

| 9. Yell | −.25* | −.08 | .21* | .07 | −.14* | .05 | .56* | .37* | -- | |

| 10. Spank | .06 | −.02 | −.21* | .15* | .07 | .19* | .18* | .31* | .39* | -- |

| 11. Ext grade 4: T | .15* | −.23* | −.28* | .12* | .20* | .50* | .04 | .13* | .07 | .21* |

Note.

coded 0 = European American, 1 = African American.

coded 0 = male, 1 = female.

coded 0 = more than one caregiver, 1 = single caregiver. Ext = externalizing behavior. K = Kindergarten. T = Teacher report. M = Mother report.

p < .05.

Hierarchical linear regression was used to determine whether ethnicity significantly predicted discipline when these other demographic variables also were considered. Separate regression analyses were conducted for reasoning, denying privileges, yelling, and spanking. As shown in Table 3, after controlling for child externalizing in kindergarten and other sociodemographic variables, child gender was significantly related only with reasoning; mothers reported reasoning more frequently with boys than with girls. Higher SES was related to more frequent reasoning and yelling and less frequent spanking. Higher levels of stress were associated with more frequent reasoning, denying privileges, yelling, and spanking. Whether there was one caregiver or more than one caregiver in the home was unrelated to any of the forms of discipline. Children with higher levels of externalizing behaviors in kindergarten were more likely to experience all forms of discipline in grades 1-3. With all of these variables in the models, ethnicity was still significantly associated with reasoning, denying privileges, and yelling. European American mothers reported more frequently using each of these three forms of discipline than did African American mothers.

Table 3. Hierarchical Regression Results Predicting Discipline.

| Reason | Deny Privileges | Yell | Spank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variable | β | β | β | β |

| Child gendera | −.10* | −.04 | −.05 | −.01 |

| SES | .17** | .05 | .16** | −.17** |

| Stress | .12** | .14** | .14** | .11* |

| Single caregiverb | −.03 | −.05 | −.08 | −.04 |

| Child externalizingc | .09* | .20*** | .10* | .15** |

| Ethnicityd | −.29*** | −.11* | −.18*** | −.02 |

| F(6, 473) | 16.31*** | 6.40*** | 9.56*** | 6.40*** |

| Adjusted R2 | .16 | .06 | .10 | .06 |

Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

coded 0 = male, 1 = female.

coded 0 = more than one caregiver, 1 = single caregiver.

teacher rating in kindergarten.

coded 0 = European American, 1 = African American.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

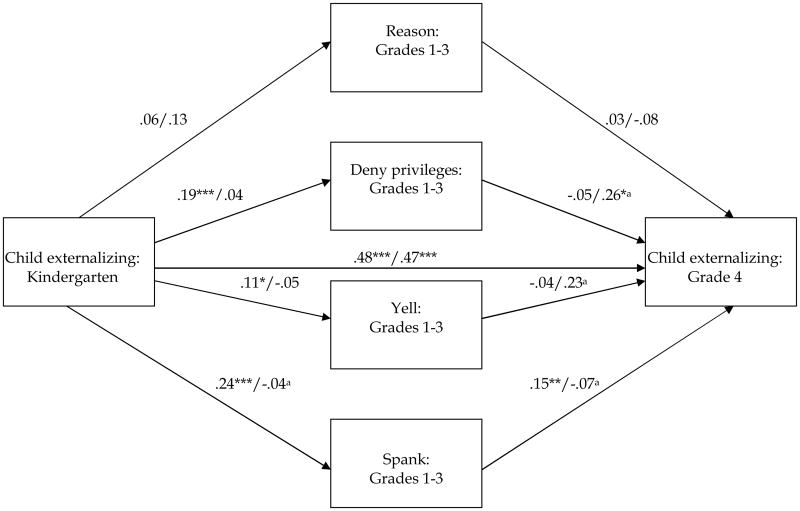

Relations between Discipline and Child Externalizing

Within ethnicity, differences in discipline used by mothers may be associated with differences in rates of child externalizing. To examine this possibility, we conducted multi-group structural equation models using AMOS 17 (Arbuckle, 2008). In each model, child externalizing in kindergarten was examined as a predictor of each of the four types of discipline in grades 1-3, and each of the four types of discipline in grades 1-3 was examined as a predictor of child externalizing in grade 4. The model also included the autoregressive path between kindergarten and grade 4 externalizing, and the error terms of the four types of discipline were allowed to correlate to account for their shared method variance.

We first tested a model in which structural paths among the variables were constrained to be equal for European American and African American families. This model fit significantly worse than did a model in which the structural paths were not constrained to be equal, Δχ2(9) = 23.82, p < .01. Thus, the results that follow are for the models in which paths were not constrained to be equal across ethnic groups.

As shown in Figure 1, teacher reported child externalizing in kindergarten significantly predicted three of the four types of discipline for European American children (denying privileges, yelling, and spanking, but not reasoning). Teacher reported child externalizing in kindergarten did not predict any of the four types of discipline in grades 1-3 for African American children. For European American children, spanking in grades 1-3 was the only form of discipline that significantly predicted more teacher-reported externalizing behaviors in grade 4. For African American children, denying privileges was the only form of discipline in grades 1-3 that significantly predicted more teacher-reported externalizing behaviors in grade 4. Teacher-reported child externalizing was highly stable over time.

Figure 1.

Multi-group structural equation model examining associations among teacher-reported child externalizing in kindergarten, mother-reported discipline in grades 1-3, and teacher-reported externalizing in grade 4. Standardized path coefficients are reported before the slash for European Americans and after the slash for African Americans. The error terms of the four types of discipline were allowed to correlate to account for their shared method variance. aDesignates path coefficients that differ significantly between European Americans and African Americans. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

Analyses examining mothers' use of reasoning, denying privileges, yelling, and spanking generally supported the hypotheses that African American and European American mothers would differ in the frequency with which they reported using different forms of discipline, that these differences would persist after controlling for potential confounds, and that different forms of discipline would be associated with externalizing behavior in different ways for African American and European American children. Although African American and European American mothers showed the same rank order frequency of use of each of the four discipline strategies, they differed in the relative frequency with which they used each strategy. Ethnic differences persisted after controlling for child gender, child externalizing behaviors, SES, family stress, and single caregiver status. For European American children, higher levels of teacher-reported child externalizing in kindergarten predicted mothers' more frequent denying privileges, yelling, and spanking in grades 1-3; only spanking was associated with more child externalizing behaviors in grade 4. For African American children, teacher-reported child externalizing in kindergarten was unrelated to mothers' subsequent discipline; only denying privileges was associated with more child externalizing in grade 4. In McLoyd and Steinberg's (1998) framework, the pattern of findings provided the most support for the hypothesis that African Americans and European Americans would demonstrate different mean levels of discipline and different correlations between discipline and externalizing.

Regardless of ethnicity, mothers used some discipline approaches more frequently than others. Both African American and European American mothers reported using reasoning most frequently, followed by yelling, denying privileges, and spanking. This finding suggests that both African American and European American mothers used a variety of discipline approaches and that spanking was the least frequently used discipline approach for both groups of mothers. It is reassuring that both African American and European American mothers most frequently reported reasoning, an inductive strategy that has been found to promote children's social competence and internalization of parents' values (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). The finding that mothers from both ethnic groups turned most infrequently to spanking is consistent with work reaching this same conclusion using a multinational sample (Gershoff et al., 2010).

Despite consistency in the rank order frequency with which they used the four types of discipline, African American and European American mothers differed in the absolute frequency with which they reported using each type of discipline. European American mothers reported reasoning, denying privileges, and yelling more frequently than did African American mothers. There were not significant ethnic differences in the frequency with which mothers spanked with their hand. Studies that aggregate different forms of discipline into a composite “harsh discipline” score may mask these kinds of differences in the discipline strategies that different mothers adopt. In addition to differing in the frequency with which they used different forms of discipline, there was more variance in African American than European American mothers' use of reasoning, yelling, and spanking, suggesting the need for future research to focus on understanding within-ethnic group differences in use of different forms of discipline in addition to between-group differences.

The popular press has dubbed shouting the new spanking (Stout, 2009). Mothers who regard spanking as socially unacceptable yet are unsuccessful in bringing about desired child behavior by more positive techniques end up yelling. Vissing, Straus, Gelles, and Harrop (1991) found that parents' verbal aggression toward children was associated with worse outcomes than physical aggression. In promoting children's rights, UNICEF (2009) has defined yelling and other harsh verbal discipline as psychologically aggressive toward children. Because harsh verbal discipline may be associated with more child externalizing problems (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992), it is important to bring harsh verbal discipline into public awareness along with corporal punishment as potentially problematic discipline strategies. Although it is generally accepted in the social scientific community that corporal punishment is the most harmful type of discipline, strident attempts to reduce the use of corporal punishment in the general population may have the unintended consequence of increasing compensatory tactics such as harsh verbal responses that may be even more harmful for some children. African American mothers are sometimes implicitly disparaged for their more frequent use of corporal punishment compared to European American mothers, so it is notable that African American mothers looked better than European American mothers in this study with respect to yelling at their children less frequently.

Within European American families, there was more evidence for child effects on a variety of forms of discipline than for parent effects of a variety of forms of discipline on children's externalizing. That is, children's externalizing behavior predicted mothers' use of three of the four subsequent forms of discipline, but only spanking predicted children's subsequent externalizing. However, within African American families, there was no evidence of child effects on mothers' discipline, and only mothers' denying privileges predicted children's subsequent externalizing. By testing for ethnic differences and examining different forms of discipline, our results provide a more nuanced understanding of Snyder et al.'s (2005) findings that child conduct problems predicted increases in parental ineffective discipline, and that ineffective discipline predicted increases in child conduct problems.

What could account for the child effects in European American families and lack of child effects in African American families? One possibility is that children's behavior at home and in school may have been more discordant for African American than European American children. For example, Youngstrom, Loeber, and Stouthamer-Loeber (2000) found that teachers reported that their male students had fewer externalizing problems than reported by the students' caregivers and the students themselves and that teacher-student disagreement was higher for African American than European American students. Given these kinds of discrepancies, then the link between teachers' reports of children's externalizing at school and mothers' use of discipline at home would be expected to be stronger for European American than African American children, as we found. We did not have data on teachers' ethnicity, but a further possibility that could be addressed in future research is that European American children may have behaved similarly at home for their European American mothers and at school for their European American teachers, whereas African American children may have behaved differently at home for their African American mothers and at school for their European American teachers.

Denying privileges is a discipline strategy that often is advocated as a positive behavior management technique in parenting interventions (e.g., Shriver & Allen, 2008). However, in our study, denying privileges was related to higher levels of subsequent externalizing behavior for African American children, after taking into account prior levels of externalizing. We did not have data on what constituted “denying privileges” in the minds of different mothers. The denial of candy or television time might be functionally different from excluding the child from the dinner table or time with parents. In addition, we did not have data on how effectively the denial of privileges was implemented. For example, if a mother told her child that he could not watch television for a week yet did not follow through on enforcing that restriction, one would not expect better child behavior in the future. However, if a mother effectively followed through on enforcing the television restriction, the child may behave better in the future. If there were ethnic differences in what constituted denial of privileges or the effectiveness of implementing the denial, this could account for differences in links between denying privileges and children's future externalizing. We urge caution in interpreting ethnic differences in the link between denying privileges and subsequent child externalizing until further studies replicate and unpack these associations.

Strengths, Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

It has been argued that obtaining information about parents' discipline and children's externalizing from distinct sources is important (e.g., Polaha, Larzelere, Shapiro, & Pettit, 2004) because having distinct reporters reduces concerns about general positivity or negativity biases that may be present if all data are obtained from a single source. Our study benefited from this strength as well as the inclusion of data from five waves spanning kindergarten through grade 4. However, the study also had several limitations.

Although externalizing problems likely elicit more discipline than do internalizing problems, it is possible that particular discipline strategies could contribute to children's internalizing as well as externalizing problems. Future research that models bidirectional associations between discipline and children's internalizing problems over time would advance understanding of developmental transactions in these relations. Child externalizing is likely to be associated with the discipline of both mothers and fathers, but only mothers' discipline was assessed in this study, and mothers were the only source of information about their discipline. Future research should include fathers and a variety of perspectives (e.g., objective observers, child reports) on the discipline to which children are exposed. It is possible that in this sample, African American and European American mothers might have used the frequency of discipline scales in different ways. If one group was more or less likely than the other group to over- or under-report the frequency with which they used a given form of discipline, this could have accounted for ethnic differences found. We focused in this study on African American and European American families, the groups that have generated the most debate regarding how corporal punishment is related to children's externalizing. Other ethnic groups within the United States as well as cultural groups outside the United States are important samples to include in future research. In addition, we focused on four forms of discipline (i.e., reasoning, denying privileges, yelling, and spanking) in relation to children's externalizing behavior problems; these are representative of common ways that U.S. American parents discipline their children, but parents also engage in other types of discipline (e.g., offering rewards for good behavior) that may also have implications for children's externalizing behaviors.

Parents' use of different forms of discipline is situated in larger parent-child and family contexts that include a wide range of factors such as parental warmth, involvement, monitoring, cognitive stimulation, and family cohesion and conflict. For example, McLoyd and Smith (2002) found that only in the context of low maternal support, but not high maternal support, spanking predicted an increase in mother-reported internalizing and externalizing problems over time for European American, African American, and Hispanic children from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Other aspects of parenting such as warmth and involvement also have been found to moderate links between corporal punishment and children's adjustment (e.g., Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Larzelere, Klein, Schumm, & Alibrando, 1989; Simons, Wu, Lin, Gordon, & Conger, 2000). Future research is needed to move beyond corporal punishment to embed the study of different forms of discipline into these larger parent-child and family contexts.

Conclusions

The present study contributes to the literature by examining four forms of discipline simultaneously rather than as discrete strategies. Although corporal punishment has received more research attention than other forms of discipline, both African American and European American mothers reported using reasoning, denying privileges, and yelling more frequently than corporal punishment. The challenge for parents, and those who work with them in preventive and therapeutic contexts, is to develop a set of discipline strategies that will minimize children's behavior problems and thereby reduce the need for frequent discipline.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants MH42498, MH56961, MH57024, and MH57095 from the National Institute of Mental Health, HD30572 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and DA016903 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Kenneth A. Dodge was supported by Senior Scientist award 2K05 DA015226 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Our spanking measure included just spanking with the hand. In supplemental analyses using a measure reflecting spanking with an object, African American mothers were found to report spanking with an object more frequently than European American mothers reported spanking with an object, suggesting that differences in this more severe form of corporal punishment may account for ethnic differences in frequency of corporal punishment use that have been reported previously in the literature (e.g., Straus & Stewart, 1999). The frequency with which mothers reported spanking with an object in grades 1-3 was significantly correlated with teacher-reported child externalizing in kindergarten and grade 4 for European American children but not significantly correlated with externalizing at either time for African American children.

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. Lansford, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University, Box 90545, Durham, NC 27708

Laura B. Wager, Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis, IN

John E. Bates, Indiana University

Kenneth A. Dodge, Duke University

Gregory S. Pettit, Auburn University

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL 14-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 17 user's guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Child-care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1967;75:43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting styles on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Kazdin AE. Spanking children: The controversies, findings, and new directions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:197–224. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Ispa JM, Fine MA, Malone PS, Brooks-Gunn J, Brady-Smith C, et al. Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income White, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development. 2009;80:1403–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Lansford JE. Parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. The handbook of cross-cultural developmental science. Florida: Taylor and Francis, Inc; 2009. pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, McAdoo HP, Garcia Coll C. The home environments of children in the United States Part I: Variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Development. 2001;72:1844–1867. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Day RD, Peterson GW, McCracken C. Predicting spanking of younger and older children by mothers and fathers. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children's externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, McLoyd VC, Lansford JE. The cultural context of physically disciplining children. In: McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA, editors. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- America's children: Key national indicators of well-being 2006. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2006. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A, Lansford JE, Chang L, Zelli A, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Parent discipline practices in an international sample: Associations with child behaviors and moderation by perceived normativeness. Child Development. 2010;81:480–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ. Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe ML, Mariner CL. Toward a developmental-contextual model of the effects of parental spanking on children's aggression. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1997;151:768–775. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170450018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffer RW, Kelley ML. Mothers' acceptance of behavioral interventions for children: The influence of parent race and income. Behavior Therapy. 1987;2:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1979. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Palmérus K, et al. Cultural normativeness as a moderator of the link between physical discipline and children's adjustment: A comparison of China, India, Italy, Kenya, Philippines, and Thailand. Child Development. 2005;76:1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Klein M, Schumm WR, Alibrando SA. Relations of spanking and other parenting characteristics to self-esteem and perceived fairness of parental discipline. Psychological Reports. 1989;64:1140–1142. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1989.64.3c.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H. Child and parent effects in boys' conduct disorder: A reinterpretation. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:683–697. [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP. African American parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting, Vol 4: Social conditions and applied parenting. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Smith J. Physical discipline and behavior problems in African American, European American and Latino children: Emotional support as a moderator. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:40–53. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Polaha J, Larzelere RE, Shapiro SK, Pettit GS. Physical discipline and child behavior problems: A study of ethnic group differences. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC. Group differences in developmental processes: The exception or the rule? Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Shriver MD, Allen KD. Working with parents of noncompliant children: A guide to evidence-based parent training for practitioners and students. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Wu C, Link K, Gordon L, Conger RD. A cross-cultural examination of the link between corporal punishment and adolescent antisocial behavior. Criminology. 2000;38:47–79. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Cramer A, Afrank J, Patterson GR. The contributions of ineffective discipline and parental hostile attributions of child misbehavior to the development of conduct problems at home and school. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:30–41. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout H. For some parents, shouting is the new spanking. The New York Times. 2009 Oct 21; Available http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/22/fashion/22yell.html.

- Straus MA, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Reviews. 1999;2:55–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Christiansen EH, Jackson S, Wyatt JM, Colman RA, Peterson RL, et al. Parent attitudes and discipline practices: Profiles and correlates in a nationally representative sample. Child Maltreatment. 1999;4:316–330. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Progress for children: A report card on child protection. New York: UNICEF; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vissing YM, Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Harrop JW. Verbal aggression by parents and psychosocial problems of children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1991;15:223–238. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90067-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom E, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male adolescent ratings of externalizing and internalizing problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1038–1050. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]