Abstract

Objective.

People have a special capacity to live simultaneously in both chronological and biographical time. In this article, we examine reports of life satisfaction that span past, present, and future, considering how perceived changes in certain life domains are associated with overall perceived life trajectories.

Methods.

Analyses use men and women from the Midlife Development in the United States survey. We employ gender-stratified fixed effects regression models to examine the net effect of satisfaction with finances, partnerships/marriage, sex, contribution to others, work, health, and relationship with children on trajectories of overall life satisfaction.

Results.

Among men, partnership and financial satisfaction had the strongest association with life satisfaction. Women displayed a somewhat broader range of domains related to their trajectories of life satisfaction. Partnership was most important, but their sense of evolving life satisfaction was also tied to their relationship with their children, sexuality, work situation, contribution to others’ welfare, and financial situation.

Discussion.

We find several notable differences between men and women, but the most telling differences emerge among women themselves across chronological time. For women, partner satisfaction becomes considerably more important across the age groups, whereas sex, contribution to others, and relationships with children all decrease in their importance for overall life satisfaction.

Key Words: Life satisfaction, Age differences, Life domains, Past, Present, Future.

Life satisfaction is a cognitive, judgmental aspect of well-being based on individuals’ consideration of how life matches expectations derived from some internal standard (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). One of the interesting findings to emerge from this field of research is that people demonstrate the ability to be dissatisfied with their life as a whole, though highly satisfied with particular components of it; and of course the opposite is true—being dissatisfied in certain corners of life is no guarantee of overall misery (Cummins, 1996). As Hsieh (2003) noted, much of this puzzle owes to the simple fact of population heterogeneity. First, people have different domains, which are relevant to their life satisfaction. Second, even if people use the same domains to evaluate life, different people put more or less value on particular domains or roles in their lives. Sociologists have used the term role-identity salience to describe this general phenomenon (Callero, 1985; Stryker & Serpe, 1994). In terms of how different domains or roles relate more specifically to an overall sense of life satisfaction, previous work has referred to domain importance (Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976).

Despite evidence that various life domains differentially contribute to overall life satisfaction (c.f. Campbell et al., 1976; Cummins, 1995, 1996), little research has questioned how this sort of heterogeneity plays out over the course of people’s lives. Do people tend to weight certain domains as more or less important for their overall life satisfaction depending on their life stage? And as people consider their past, examine their present, and anticipate their future, do particular domains predict their subjective trajectory of life satisfaction?

Humans have the unique ability to extend the self beyond the experience of the present to the past and to the future. This diachronic nature of human selves means that people make sense of their world by forming narratives that tie together past events, current context, and anticipations for the future (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998; McAdams, 2001). Therefore, people are classified and segregated by how they stand in relation to an objective time referent (i.e., age), but they also maintain their own internal timelines by which the life course is partitioned into different diachronic segments (i.e., personal biography). We will use the concept of diachronic evaluations of domain importance (DEDI) to develop these issues in relation to life satisfaction.

Temporality, however, is not merely an issue of subjective diachronic evaluation; people live in actual calendar time in which years have meaning for norms, roles, and developmental processes. The extent, then, to which each domain of social life matters for life overall is also likely a function of chronological age. As a central part of social structure, age creates and constrains institutionalized opportunities and material provisions (Riley, 1987; Shanahan, 2000); it also shapes expectations, aspirations, motivations, and the other elements of peoples’ agency (Baltes, Reese, & Lipsitt, 1980). Thus, any attempt to examine DEDI should be sensitive to how various aspects of well-being differ in overall importance according to chronological age. As people age, temporal frontiers shift and adults can re-evaluate the importance of life domains.

Uniting these two aspects of temporality—diachronous and chronological time—in regard to life satisfaction will help enhance our understanding of well-being in multiple ways. The purpose of this study is to examine age differences in DEDI with a national sample of people aged 30–74 who have a romantic partner and at least one child. Differentiating between global life evaluations and domain-specific life evaluations, we examine people’s views of their past, present, and future and ask whether men and women’s overall perceived life trajectories are shaped by their satisfaction in seven different realms. By examining these time points by separate age classifications, we study the relative importance of different life domains at the intersection of two types of time: (a) objective, developmental time (time alive; i.e., age) and (b) subjective, biographical time (a view that spans the specious present, reconstructed past, and anticipated future; i.e., diachronic perspective). We examine whether the sources of life satisfaction shift over these temporal horizons.

Differences in Life Satisfaction Across Chronological Age and Biographical Age

Assessing variation in life satisfaction among people of differing chronological ages has been a hallmark activity of social gerontology since the inception of the field. As of this writing, Neugarten, Havighurst, and Tobin’s (1961) seminal piece on measuring life satisfaction among older people has been cited more than 1,000 times and is arguably one of the most influential works of social scientific aging research to date (Ferraro & Schafer, 2008). Aging research finds that well-being remains largely stable over the life course; observable change tends to be somewhat positive with increasing age, but modest decreases are evident late in the life course as health problems set in (Campbell et al., 1976; Diener, 1984; Herzog & Rodgers, 1981; Kunzmann, Little, & Smith, 2000; Larson, 1978; Mroczek & Spiro, 2005). Some evidence suggests that changes in specific life domains, such as social relationships and material well-being, tend to increase with age (Butt & Beiser, 1987). When surveying the extant body of research, Diener and Suh (1998) suggest that these positive patterns could be due to older adults lowering their aspirations for satisfaction or at least being better in adjusting their expectations in light of their strengths and resources.

The relative importance of particular domains for overall life satisfaction, however, remains unclear. One study of Chicago residents aged 50–87 found that the most important domains were health, family, and religion, but the importance of health declined with advancing age (Hsieh, 2005). Unfortunately, the study’s small sample with unknown external validity and the lack of relevant controls (e.g., no adjustment for sex, work status, and marital status) suggest that conclusions about age differences in domain importance may be premature.

The current study, however, is distinctive in its attention to an additional matter of temporality. Life satisfaction—whether general or domain specific—is typically examined in regard to the present and often with single indicators of the concept (George, 2010). This is despite the fact that the original life satisfaction indexes pioneered by Neugarten et al. (1961) were replete with questions tapping temporal perspectives (e.g., “When I think back over my life” and “I am just as happy as when I was younger”). The present study seeks to restore this emphasis on temporal considerations in the study of life satisfaction. Instead of evaluating a person’s current life satisfaction only, we use reports of past, present, and future life satisfaction to examine the tenses of life satisfaction. Two recent studies are informative in this regard. First, Schafer, Ferraro, & Mustillo (2011) used the three tenses in a study of life satisfaction to create a perceived life trajectory that expresses whether people think things are getting better, worse, or staying about the same. Second, Lachman, Röcke, Rosnick, and Ryff (2008) examined diachronic life satisfaction by comparing a respondent’s 1995 rating of the future with their 2005 rating of the present. Interestingly, younger persons tended to disparage their past but were inaccurately optimistic about their futures, whereas older participants were much more realistic about both the past and the future. The team explained these results in reference to motivation and development—young adults imagine a great deal of life change, whereas older adults tend to have better self-awareness and acceptance of their current position (Ryff, 1991). What remains less clear, however, is how such general views of past, present, and future correspond with diachronic perspectives about key life domains.

Approach of This Article

Whereas this article explores essentially unchartered territory on life satisfaction and the life course, we see the intent of our analyses as principally descriptive. Our aim was to document patterns of diachronic life evaluations and to examine whether general perceived life trajectories are associated with positive evaluations in seven influential life domains: health, work, finances, helping others, partnership, relationship with children, and sexuality. No hypotheses are proposed for whether and why one domain or another is especially important. In the words of Amato and colleagues (2008), we seek to “establish that a phenomenon has a sufficient degree of regularity and coherence before embarking on explanation” (p. 1274).

Our research aims are organized around locating domain importance of life satisfaction (DEDI) at the intersection of chronological and biographical time. When assessing the strength of association between general and domain-specific evaluations of life satisfaction across the past, present, and future, we make comparisons across three age groups of adults who have a partner and at least one child during a survey interview. Also, we follow the consensus of research in this area that “studies of satisfaction with life should be conducted with parallel analyses for each sex” (Medley, 1976, p. 454). Given the importance of gender for shaping both life satisfaction and social roles over the life course, we give attention to whether men and women are distinctive in how they value domains of life satisfaction.

Methods

Sample

The data for this study come from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS; Brim et al., 2000). The MIDUS data are ideal for the questions we ask because they contain a number of variables related to various domains of life satisfaction and at various diachronic time points. The sample also had a relatively inclusive age range (25–74), allowing us to study respondents across a wide spectrum of chronological time.

Data collection for the study was undertaken from 1995 to 1996 by the MacArthur Foundation’s Network on Successful Midlife Development. The survey first used random digit dialing to obtain a sampling frame of all English-speaking noninstitutionalized adults aged 25–74 in the contiguous 48 states. The response rate from these initial telephone interviews was 70%. The final stage included a two-part follow-up questionnaire mailed to those who participated in the telephone interview, yielding an 86.6% response rate. Thus, the overall response rate was 61% (0.70×0.87 = 0.61), producing a total sample of 3,032 participants.

A follow-up wave of the MIDUS was conducted a decade later, reinterviewing surviving respondents and collecting data on many of the same issues assessed during the baseline survey. We considered adding a third temporal element (historical time) to the other two foci of this study—chronological and diachronic time—but concluded that it unnecessarily complicated the analysis for the research questions we articulated. We recognize that this is a departure from often-assumed mantras about the superiority of longitudinal data (more waves > fewer waves) but emphasize that our attention to diachronic time is a legitimate temporal entity that is well captured at a single measurement occasion. A logical next step for future research, however, might be to extend the findings reported here to a longitudinal analysis.

Our analyses for the initial wave are based on respondents aged 30 and older for two reasons. First, a disproportionate number of people in their 20s are less likely to be married or in a marriage-like partnership or to have had children (63% were married or in a marriage-like relationship and 46% had children, compared with 69% and 86%, respectively, among those older than 30 years). Second, as described subsequently in more detail, probing diachronic time relies on asking respondents to look back and forward 10 years. Whereas the vast majority of participants younger than 30 years would not have held essential roles related to various domains of satisfaction (e.g., partnered, a parent), there would be little upon which to base their retrospective evaluations. As a result, the study sample was therefore reduced to 2,742 by eliminating people younger than 30.

Because people differ in the social roles they occupy, not all remaining respondents had valid scores on each of the domains of life satisfaction. In order to maintain consistency in life domain relevance across all the respondents, the baseline study sample was therefore reduced again to 1,748 by eliminating people who were not currently married/partnered and did not have children in 1995. This decision limits our sample and the generalizability of our findings, but we consider it a necessary action. First, examining people’s domains of life satisfaction without accounting for partnerships and parenthood is of questionable validity when most people are engaged in these roles at least some time during middle age; these parts of life are central to many people’s identity (Reitzes & Mutran, 2002). Therefore, we thought it unwise to leave out those domains and analyze only the domains that are relevant for all respondents (e.g., health, financial condition). Second, marriage (or partnered relationships) and parenthood are customary life phases in the sense that most adults will be married and have children at some point in their life. For instance, even with an increasing number of households occupied by single residents, more than 80% of women will be married by age 45, and about 90% of never-married Americans believe they will be partnered at some point in their life (Klinenberg, 2012, p. 60). MIDUS participants excluded for lack of a partner/child tended to be somewhat lower than nonexcluded respondents in overall life satisfaction and satisfaction with work and finances. They tended to be in somewhat better health but had about the same level of socioeconomic position. Excluded respondents were more likely to be men. Finally, the sample was reduced to 1,648 due to nonresponse on one or more domains of satisfaction (<10% of the analytic sample).

Although the average age of our study sample does not differ markedly from that of the main, unrestricted sample (M of 49 vs. 47 years), removed cases were somewhat more likely to come from the tails of the age distribution. Chi-squared tests, however, showed that likelihood of exclusion was not significantly different across the three age groupings used in this study (p = .170). In a purely statistical sense, the social roles of partner and parent are “normal” and expected. Regardless, we undertook sensitivity checks to ensure that our estimates presented subsequently were not an artifact of our decision to restrict the sample (e.g., models were estimated on the full sample). There was no evidence of substantive difference in findings beyond the fact that nonpartnered people could not have an evaluation of their partner and childless individuals could not have an evaluation on satisfaction with their children.

Measures

Life satisfaction.—

Variables for life satisfaction come from an overall indicator and from seven specific domains. For overall life satisfaction, respondents were first asked: “Using a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 means “the worst possible life overall” and 10 means “the best possible life overall,” how would you rate your life overall these days?” Respondents were next asked how they would rate their life overall “looking back 10 years ago,” and finally, to give their rating “looking ahead 10 years into the future.” This same triad of questions was also asked for (a) health, (b) work situation (pertaining to paid or nonpaid job, and/or home varieties of productive activity), (c) financial situation, (d) contribution to the welfare and well-being of other people, (e) relationship with one’s children, (f) marital or close relationship (partner), and (g) sex. We recognize that this set of life domains is far from exhaustive, and we note that it reflects, fundamentally, the areas deemed of interest and/or importance to the initial MIDUS investigators. In the interest of being as domain inclusive as the data allow, we focused the analysis on respondents who were partnered and with children.

Analysis

To address our research question about how diachronic evaluations of various domains of life satisfaction affect changing perceptions of overall life satisfaction from past to present to future, we utilized a fixed effects (FE) regression model. The FE model is a longitudinal within-subject model that controls for measured and unmeasured characteristics of participants by partialing them out of the estimating equation (Allison, 2009). In contrast to the more popular random effects approach, which treats unobserved characteristics as random variables that are assumed to be uncorrelated with the observed explanatory variables, FE models allow the unobservables to correlate with the observed explanatory variables (Wooldridge, 2010). In our case, this means that all time-invariant characteristics of participants, measured and unmeasured, that may be correlated with their diachronic evaluations of domains of life satisfaction are controlled, including race, SES, pre-existing health conditions, and level of optimism. The resulting estimates are consistent and unbiased.

In the FE model, we regress perceived change in overall life satisfaction on three-way interaction terms that include each domain multiplied by gender and age group (<45, 45–59, 60+). (Ultimately, these age groups are arbitrary constructions, but prior studies have similarly used broad categories to differentiate MIDUS respondents of different ages; see Lachman et al., 2008.) Supplementary analyses used alternate age classification schemes, but there proved no substantive rationale for preferring them over the ones used herein.

The resulting coefficients from the FE model can be interpreted as the expected change in diachronic life satisfaction for a 1-unit change in satisfaction with each domain by gender and age group, net of the other domains. Controlling for the other domains allows us to disentangle and isolate the effects of related domains—such as work and finances or partnership and sex. Because all of the domains were measured on the same scale, the coefficients are directly comparable in terms of assessing relative impact on overall life satisfaction. Further, we used post hoc Wald tests to test simple and composite linear hypotheses. Initial analyses examined potential interdomain multicollinearity, but none of the domains overlapped to a problematic degree (the highest level of correlation was between satisfaction with partnership and satisfaction with sex, r around .5 for each of the perceived time points). All analyses were performed using Stata 12.

We realize that using diachronic time as three separate time points is a departure from the standard estimation of a panel model, which typically employs distinct chronological measurement occasions. This, however, is a conceptual matter and not a statistical one; the estimation itself of a FE model is not sensitive to the type of time in question. Our results, then, must be interpreted in light of theoretical, interpretive time within the actor’s temporal perspective (c.f. Schafer et al., 2011).

Results

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 reflect the basic composition of the sample. Table 2 displays M, SDs, and number of survey responses for the diachronic life evaluations for the entire sample. Generally speaking, people report that most aspects of their lives have improved—from past to present—and will get better in the future. This includes overall life evaluation and the evaluation of work, contribution to others, partnership/marriage, relationship with children, and finances. There are, however, two notable exceptions: sexual satisfaction is much lower in the present than it was in the past, but respondents anticipate a future rebound; and health decline is evident across the three biographical time points.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics Among Those Partnered With Children in MIDUS I (N = 1,648)

| Range | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 30–74 | 49.11 (11.46) |

| Female | 0–1 | 0.47 |

| Non-White | 0–1 | 0.09 |

| Working | 0–1 | 0.59 |

| Chronic conditions | 0–27 | 2.52 (2.61) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0–1 | 0.30 |

Table 2.

Life Satisfaction Across Diachronic Time Among Those Partnered With Children in MIDUS I (N = 1,648)

| Past | Present | Future | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall life satisfaction | 7.40 (SD = 1.82, n = 1648) | 7.86 (SD = 1.50, n = 1643) | 8.33 (SD = 1.54, n = 1644) |

| Domains of life satisfaction | |||

| Work | 7.14 (SD = 2.25, n = 1638) | 7.38 (SD = 2.31, n = 1617) | 7.67 (SD = 2.44, n = 1600) |

| Contribution to others | 6.21 (SD = 2.26, n = 1648) | 6.66 (SD = 2.13, n = 1633) | 6.96 (SD = 2.16, n = 1642) |

| Sex | 7.02 (SD = 2.50, n = 1638) | 6.14 (SD = 2.82, n = 1644) | 6.26 (SD = 2.92, n = 1640) |

| Partnership | 7.17 (SD = 2.67, n = 1608) | 8.14 (SD = 2.01, n = 1645) | 8.70 (SD = 1.80, n = 1639) |

| Health | 8.22 (SD = 1.68, n = 1648) | 7.36 (SD = 1.64, n = 1648) | 6.90 (SD = 1.97, n = 1641) |

| Relationship with children | 8.44 (SD = 1.67, n = 1373) | 8.62 (SD = 1.53, n = 1643) | 8.96 (SD = 1.33, n = 1647) |

| Finances | 5.93 (SD = 2.16, n = 1647) | 6.32 (SD = 2.09, n = 1639) | 7.40 (SD = 1.92, n = 1646) |

Notes. Ms are presented with SDs in parentheses. The range of each life satisfaction score is 0–10.

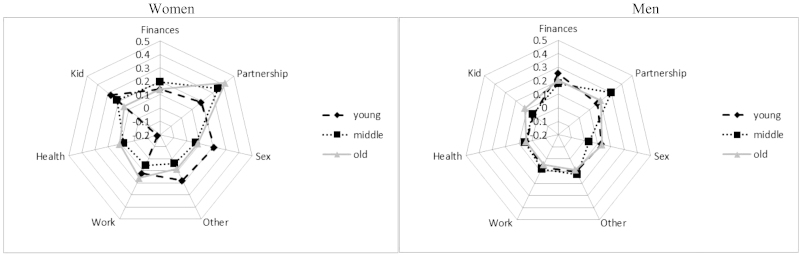

Moving from the description of overall evaluations of life to an analysis of how perceived changes in different life domains are associated with perceived changes in overall life satisfaction, we present results from the FE models in Table 3. Independent variables, which represent a one-unit change in each of the seven domains from past to present to future, are shown in the seven columns. Because the model features three-way interaction terms between each domain, gender, and age category, we present the coefficients in separate rows (for age categories) and in two additional columns per each life domain (for gender). In order to aid interpretation, we present Figure 1 to succinctly capture the multiple parameters assessed by the interactions in our model. The figure plots the coefficient of all seven domains of life satisfaction on overall life satisfaction for both men and women. Each successive strand of the web represents an increase in effect size, spanning −0.2 to 0.5.

Table 3.

Estimates from Fixed Effects Model of Overall Life Satisfaction on Various Domains by Age Group and Gender, MIDUS I

| Health | Work | Finances | Helping others | Partnership | Children | Sex | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Age 30–44 | 0.049 | −0.179 | 0.066 | 0.119* | 0.250*** | 0.142 | 0.105 | 0.177** | 0.169*** | 0.190* | 0.036 | 0.271* | 0.130** | 0.211** | |

| (0.050) | (0.101) | (0.044) | (0.052) | (0.038) | (0.075) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.047) | (0.076) | (0.054) | (0.118) | (0.042) | (0.075) | ||

| Age 45–59 | 0.054 | 0.083** | 0.083** | 0.055 | 0.178*** | 0.194*** | 0.125** | 0.037 | 0.299*** | 0.349*** | 0.039 | 0.214*** | 0.038 | 0.072* | |

| (0.040) | (0.026) | (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.040) | (0.037) | (0.039) | (0.048) | (0.046) | (0.048) | (0.057) | (0.063) | (0.035) | (0.028) | ||

| Age 60+ | 0.042 | 0.110 | 0.046 | 0.160** | 0.204*** | 0.142* | 0.088 | 0.083 | 0.205*** | 0.420*** | 0.116 | 0.144 | 0.135*** | 0.088 | |

| (0.039) | (0.066) | (0.034) | (0.051) | (0.050) | (0.063) | (0.055) | (0.097) | (0.034) | (0.120) | (0.073) | (0.135) | (0.036) | (0.049) | ||

| Constant | 1.095*** | ||||||||||||||

| (0.329) | |||||||||||||||

Note. N = 1,648 respondents.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Figure 1.

Contribution of satisfaction in seven life domains to overall life satisfaction across past, present, and future among men and women. Values reflected in the web are effect sizes of each domain’s coefficient based on their interaction with gender and age (models estimated in Table 3).

Comparing men and women across the seven life domains reveals some interesting contrasts. First, women tend to have larger coefficients for most of the domains, revealing a more robust association between perceived changes in a given area of life and a perceived change in overall life satisfaction. The exception to this general pattern is in the case of finances; for men, a 1-unit change in financial evaluations is associated with a 0.18 (middle age) and a 0.25 (younger age) increase in overall life satisfaction. For women, the association only ranges from 0.14 (older age) to 0.19 (middle age). Overall, it appears that the various domains assessed in the MIDUS study are more consistently related to life satisfaction among women than they are among men. For women, there is a positive and significant relationship with overall life satisfaction for at least one group within all seven domains. For men, only 5 of 7 domains are significantly related to overall life satisfaction (work, finances, helping others, partnership, and sex). This may indicate a greater degree of “balance” for women, in that their conception of life getting better or worse from the past to the present is dispersed among a greater range of life domains. And, because each of the seven domains is measured by the same metric (0–10), it is straightforward to compare the magnitude of the coefficients across the variables (akin to comparing standardized beta coefficients in OLS). These estimated parameters are generally larger for women than for men. Figure 1 demonstrates this pattern with perhaps more clarity than the table of estimates; note the greater level of “stretch” in women’s webs relative to men.

The second major contrast shown in Table 3 and Figure 1 is age category differences. Comparing the three rows reveals several differences between younger-, middle-, and older-aged adults. Specifically, changes in partner satisfaction over diachronic time are far more consequential for perceived changes in overall life satisfaction among the two oldest groups that among the youngest group. This pattern is evident in Figure 1, where the dashed line represents the younger age group, whose coefficient does not extend to that of the two older groups. Although apparent for both genders, the effect is larger among women (p < .05). In contrast to the growing importance of the partnership/marriage life domain across age groups for women, women manifest a receding importance of sex, helping others, and relationship with their children with increasing age. Concerning satisfaction with sex, the coefficient is about 1/3 as large for middle- (.07) and older-aged (.09) women as it is among the youngest women (.21) (p < .05).

For contribution to others, the effect decreases from 0.18 for young women to 0.04 and 0.08 for middle- and older-aged women, respectively (p < .05). Likewise, the association between children relationships and overall life satisfaction is only about half as strong among the oldest respondents (.14) as it is among the youngest ones (.27) (p < .05). Together, these findings suggest that younger women view an increasingly generative, sexually fulfilling, and parentally enjoyable life as fairly consequential to their perceived life satisfaction trajectory, but older women are most inclined to see the course of their partnership as the decisive element in their life satisfaction.

We conducted a number of sensitivity analyses to examine whether the results are stable under different sample restrictions or the inclusion of variables indicating recent changes in the respondents’ lives. When we further restrict the sample to only those who were partnered with children in both 1985 and 1995 (n = 1,211), we find substantively identical results to those presented in Table 3 but with two notable exceptions: financial satisfaction for younger women becomes larger in size and statistically significant as does satisfaction with children for older men. We also re-estimated the Table 3 models for nonpartnered respondents (without partner satisfaction). The only consistent difference was that adults without partners had higher coefficients for satisfaction with kids compared with those with partners. That is, it appears that satisfaction with kids is more important to overall life satisfaction if one does not have a partner. The coefficients in the other domains are largely consistent across the two models. Finally, we examined the time-varying effects of partnership, parental, and employment status on our results. If we limit the model to examining the change in life satisfaction from past to present only, those who changed partner, parent, or employment status from 1985 to 1995 are similar in terms of average life satisfaction to those who do not undergo such changes. Further, covariates for partner, children, and employment are not significant in the model when added as time-varying controls and do not change the conclusions we draw from our model.

Discussion

The aim of this article was to address several exploratory questions related to domains of life satisfaction. Our research objectives emphasized that humans have a special capacity to consider the past, present, and future as a coherent temporal unit, but that their lives are also shaped, in part, by their own chronological position in the life course. Therefore, we considered whether particular life domains tend to uniquely predict the rise or fall of general life satisfaction differently according to age.

The most consistent finding from these analyses was that older people see partnership/marriage as playing a larger role in their overall life satisfaction trajectories than do younger adults. This pattern was observed among both men and women, but it was especially salient among women. Other studies have shown that partnership is an especially pertinent domain for older people’s well-being (Butt & Beiser, 1987; Walker & Luszcz, 2009). What is distinct about these findings, however, is that we are able to look across 20 years of diachronic time—10 years in the past until 10 years in the future—and see how people of different ages (i.e., different chronological time) view the importance of partner relations for their life trajectory.

Another clear age pattern emerged among women: a satisfying sex life, the quality of relationship with one’s children, and contribution to others’ welfare all lost prominence for overall life satisfaction from the younger age groups to the older groups. The overall size of the effects and the magnitude of the shifts across age groups were much more modest for men.

The sexuality finding among women is interesting in light of recent research on sexuality among a representative sample of U.S. older age adults, showing that almost three quarters of Americans aged 57–64 and more than half of people aged 65–74 are sexually active, but that health problems become a significant limitation on sexuality for many older adults (Lindau et al., 2007). Part of the reason that sexuality seems less central for life trajectories among older women perhaps comes from the shifting importance of other domains, namely partnership and health. Sexuality remains important for older women, but its significance for perceived life trajectories fits within the greater context of relational stability, support, and companionship. Prior research supports this assertion. For instance, in a series of in-depth interviews, Gott and Hinchliff (2003) find that older adults in long-term, committed partnerships are able to cope with the difficulties that declining health poses for their sexual expression, and they see the importance of sexuality as encased in the broader satisfaction of their relationship. Likewise, because health status and sexuality become so intertwined among older adults, part of women’s expectations for their sexual life rest within their health functionality. Simply put, people find it very difficult to maintain a satisfying sexual life if their health prohibits it (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010). Among older women, sex per se becomes eclipsed by other life concerns that coincide with and support sexual flourishing. Indeed, the magnitude of the coefficients for partnership becomes much greater among the oldest group than it is for the youngest group of women.

The declining centrality of contribution to others’ welfare and relationship with children may also reveal shifting perspectives or priorities of aging women. For women younger than 45 years, the effect of relationship with children and contribution to others’ welfare is as strong (contribution to others) or stronger (children) than the association of partner satisfaction with overall life satisfaction trajectories. One explanation for this finding is that women of the youngest age range (30–44) devote more time to parenting and caring/contributory activity than do men (see Wilson, 2000, Mattingly & Bianchi, 2003). If these activities demand a relatively high amount of time and attention, it is reasonable that perceived changes in these domains are viewed as tightly connected to changes in life satisfaction. With increased age, however, it seems plausible that other social role relations, namely partnership, rise in importance for shaping overall perceived life trajectories. Despite many women’s sustained interest in civic engagement and their continuing role as “kin keeper”—the maintainer of intergenerational family bonds—across the life course (Moen, 1996), it appears that the rise and fall of life satisfaction are far less tethered to these life domains among older women.

Although women demonstrate the importance of multiple life domains, men’s subjective life trajectories appear to be driven mainly by partner relationships and financial satisfaction. Most other effects were notably smaller among men than were observed among women. This finding could reflect one of several factors. Perhaps men are “less balanced” in what informs their idea of overall satisfaction, looking only to two domains when gauging whether life in general is improving or worsening from the past to the present. On the other hand, perhaps the seven life domains included in the MIDUS survey were skewed toward women’s prevailing concerns and overlooked crucial determinants of male life satisfaction. Thus, we welcome research that includes a wider array of life satisfaction domains to address this question.

Our efforts to understand the shifting contexts of life satisfaction, as with all exploratory studies, are a tradeoff of strengths and weaknesses. No specific hypotheses were tested because we had insufficient a priori knowledge to construct a series of testable propositions; clarifying a set of patterns for future research, however, is more a necessary first scientific step than an actual limitation (Amato et al., 2008). As we mentioned earlier, our attempt to examine the relative importance of life domains across different diachronic time points for different age groups meant that we would necessarily exclude people who had not yet experienced partnership or parenthood (though supplementary analyses conducted on the full sample yielded very similar findings for the other five domains). This study is therefore based only on a sample of married/partnered parents, which makes the group an inherently select entity. For the purposes of our analyses, however, this is reasonable, though somewhat limiting restriction. A more serious concern, however, is that we were only able to assess the seven life domains that were of interest to the MIDUS investigators (finances, partnership, sex, contribution to others, work, health, and relationship with children). By necessity, this leaves out an almost limitless number of life domains that could be crucial for some persons’ sense of life satisfaction—religious life, sport, exercise, leisure, housing and neighborhood quality, relationship with pets, evaluation of the weather, and so on. As we noted earlier, this omission could make the interpretation of male/female differences somewhat problematic (if men and women differentially prioritize neglected domains). This would limit our ability to draw definitive conclusions from intergender comparisons. On the other hand, omitted domains that take on particular importance in later life could complicate our ability to draw conclusions about intragender age differences in diachronic evaluations.

A final potential weakness is that our data are based on recollected evaluations (i.e., judgments about 10 years in the past). This, however, is not a conventional concern because we acknowledge that there is nothing truly “objective” about past life evaluations. Diachronic evaluations are by their very nature rooted in the present but building from a remembered past and looking forward to an anticipated future (Mead, 1932). Therefore, we fully anticipate that recollected life satisfaction would not match actual evaluations from 1985 if we were to have them available.

As for advantages, the specific data we used to study diachronic evaluations in life satisfaction (MIDUS) offers several distinct advantages. Our sample was relatively large and representative of young-, middle-, and older-aged American adults. This is a marked improvement over many of the samples used in prior studies (Hsieh, 2005). MIDUS also contained a number of relevant life domains to study in relation to overall life satisfaction. We were able to observe some variance in domain importance across this variety of life domains, especially between men and women and across age groups in the areas of sex, relationship with children, contribution to others’ welfare, and health. Future work can extend our findings to examine issues of life course agency, such as the factors that motivate choices and goal-oriented behavior at different junctures in the life course (Hitlin & Elder, 2007) or study the consequences for well-being on setting realistic or unrealistic expectations for certain life domains (Lachman et al., 2008).

Funding

Support for this research was provided by a grant to K. F. Ferraro from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG033541).

Acknowledgments

We thank the JGSS Editor and referees for their supportive suggestions and critiques. Don Reitzes also offered helpful comments on an earlier draft. The data were made available by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI. Neither the collector of the original data nor the Consortium bears any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

References

- Allison P. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. New York: Sage; [Google Scholar]

- Amato P. R., Landale N. S., Havasevich T. C., Booth A., Eggebeen D. J., Schoen R., McHale S. M. (2008). Precursors of young women’s family formation pathways. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 70, 1271–1286. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00565.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes P. B., Reese H. W., Lipsitt L. P. (1980). Life-span developmental psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 35, 61–110. 10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.000433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim O. G., Baltes P. B., Bumpass L. L., Cleary P. D., Featherman D. L., Hazard W. R. … Shweder R. A. (2000). National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States MIDUS, 1995–1996. [Computer file]. ICPSR version. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor] [Google Scholar]

- Butt D. S., Beiser M. (1987). Successful aging: A theme for international psychology. Psychology and Aging, 2, 87–94. 10.1037/ 0882-7974.2.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callero P. L. (1985). Role-identity salience. Social Psychology Quarterly, 48, 203–215. 10.2307/3033681 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A., Converse P. E., Rodgers W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfaction. New York: Russel Sage; [Google Scholar]

- Cummins R. A. (1995). On the trail of gold standard for life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 35, 179–200. 10.1007/ BF01079026 [Google Scholar]

- Cummins R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38, 303–328. 10.1007/BF00292050 [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R. A., Larsen R. J., Griffin S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Suh M. E. (1998). Subjective well-being and age: An international analysis. Annual Review of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 17, 304–324 [Google Scholar]

- Emirbayer M., Mische A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103, 962–1023. 10.1086/231294 [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K. F., Schafer M. H. (2008). Gerontology’s greatest hits. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, 3–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George L. K. (2010). Still happy after all these years: Research frontiers on subjective well-being in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65, 331–339. 10.1093/geronb/gbq006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott M., Hinchliff S. (2003). How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 56, 1617–1628. http//dx..org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00180-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog A. R., Rodgers W. L. (1981). Age and satisfaction: Data from several large surveys. Research on Aging, 3, 142–165. 10.1177/016402758132002 [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin S., Elder G. H., Jr (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25, 170–191. 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2007.00303.x [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C. M. (2003). Counting importance: The case of life satisfaction and relative domain importance. Social Indicators Research, 61, 227–240. 10.1023/A1021354132664 [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C. M. (2005). Age and relative importance of major life domains. Journal of Aging Studies, 19, 503–512. 10.1016/ j.jaging.2005.07.001 [Google Scholar]

- Klinenberg E. (2012). Going solo: The extraordinary rise and surprising appeal of living alone. New York: The Penguin Press; [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann U., Little T. D., Smith J. (2000). Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging, 15, 511–526. 10.1037/0882-7974.15.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman M. E., Röcke C., Rosnick C., Ryff C. D. (2008). Realism and illusion in Americans’ temporal views of their life satisfaction: Age differences in reconstructing the past and anticipating the future. Psychological Science, 19, 889–897. 10.1111/j.1467- 9280.2008.02173.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R. (1978). Thirty years of research on the subjective well-being of older americans. Journal of Gerontology, 33, 109–125. 10.1093/geronj/33.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T., Gavrilova N. (2010). Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: Evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 340, c810. 10.1136/ bmj.c810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T., Schumm L. P., Laumann E. O., Levinson W., O’Muircheartaigh C. A., Waite L. J. (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 762–774. 10.1056/ NEJMoa067423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly M. J., Bianchi S. M. (2003). Gender differences in the quantity and quality of free time: The U.S. experience. Social Forces, 81, 999–1030. 10.1353/sof.2003.0036 [Google Scholar]

- McAdams D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5, 100–122 [Google Scholar]

- Mead G. H. (1932). The philosophy of the present. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; [Google Scholar]

- Medley M. L. (1976). Satisfaction with life among persons sixty-five years and older. A causal model. Journal of Gerontology, 31, 448–455. 10.1093/geronj/31.4.448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P. (1996). Gender, age, and the life course. In Binstock R. H., George L. K. (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences, (4th ed., pp. 171). San Diego: Academic Press; [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek D. K., Spiro A., 3rd (2005). Change in life satisfaction during adulthood: Findings from the veterans affairs normative aging study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 189–202. 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten B. L., Havighurst R. J., Tobin S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16, 134–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzes D. C., Mutran E. J. (2002). Self-concept as the organization of roles: Importance, centrality, and balance. The Sociological Quarterly, 43, 647–667. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2002.tb00070.x [Google Scholar]

- Riley M. W. (1987). On the significance of age in sociology. American Sociological Review, 52, 1–14 [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. D. (1991). Possible selves in adulthood and old age: A tale of shifting horizons. Psychology and Aging, 6, 286–295. 10.1037/ 0882-7974.6.2.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer M. H., Ferraro K. F., Mustillo S. A. (2011). Children of misfortune: Early adversity and cumulative inequality in perceived life trajectories. American Journal of Sociology, 116, 1053–1091. 10.1086/655760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan M. J. (2000). Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 667–692. 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.667 [Google Scholar]

- Stryker S., Serpe R. T. (1994). Identity salience and psychological centrality: Equivalent, overlapping, or complementary concepts? Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 16–35. 10.2307/2786972 [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. B., Luszcz M. A. (2009). The health and relationship dynamics of late-life couples: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing and Society, 29, 455–480. 10.1017/S0144686X08007903 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 215–240. 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215 [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge J. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, (2nd ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press; [Google Scholar]