Abstract

Objective

To examine trends in children's exposure to food-related advertising on television by age, product category and company.

Design

Nutritional content analysis using television ratings data for the years 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009 for children.

Setting

Annual age-specific television ratings data captured children's exposure to broadcast network, cable network, syndicated and spot television food advertising from all (except Spanish language) programming.

Participants

Children ages 2–5 and 6–11.

Main Exposure

Television ratings.

Main Outcome Measures

Children's exposure to food-related advertising on television with nutritional assessments for food and beverage products for grams of saturated fat, sugar and fiber, and milligrams of sodium.

Results

Children ages 2–5 and 6–11, respectively, saw, on average, 10.9 and 12.7 food-related television advertisements daily, in 2009, down 17.8% and 6.9% from 2003. Exposure to food and beverage products high in saturated fat, sugar or sodium (SAFSUSO) fell 37.9% and 27.7% but fast food advertising exposure increased by 21.1% and 30.8% among 2–5 and 6–11 year olds, respectively, between 2003 and 2009. In 2009, 86% of ads seen by children were for products high in SAFSUSO, down from 94% in 2003.

Conclusions

Exposure to unhealthy food and beverage product advertisements has fallen, whereas exposure to fast food ads increased from 2003 to 2009. By 2009, there was not a substantial improvement in the nutritional content of food and beverage advertisements that continued to be advertised and viewed on television by U.S. children.

Keywords: nutrition, food advertising, media, obesity

Introduction

In 2007–08, 10.4% and 19.6% of children ages 2–5 and 6–11, respectively, were obese1. Children's diets were poorer than recommended and high sugar, fat, saturated fat, sodium and fast food intakes were associated with increased obesity and other health consequences2–9. Children averaged 3.5 hours of television watching daily in 2009, and 23% of households with televisions had a set in a child's bedroom10. Television remained the most common form of media used by children11. Television also remained the primary advertising channel for food and beverage companies who spent an estimated $745 million dollars in this medium of which more than 50% was directed to children under the age of 1212.

Research shows that the majority of food ads seen by children were for unhealthful products13–17. For example, one study using television ratings data found that 97.8% of advertisements seen by children aged 2–11 were for products high in fat, sugar or sodium17. Another study that used television ratings data found that cereal companies mostly marketed their least nutritious cereals to children, and none of the brands marketed to U.S. children met nutritional standards set for advertising to UK children14. A recent examination of the nutritional content of food ads during children's programming found that 72.5% were for high-calorie low-nutrient products, 26.6% were for high-fat or sugar products and just 0.9% were for low-calorie nutrient-rich products18. Further, several studies showed that children's exposure to fast food advertising has recently increased19,20. The public health community and government agencies have emphasized the need to address unhealthful food advertising seen by children11,12,21. Evidence showed that food advertising increases purchase requests and consumption11 and found a positive association with weight outcomes22,23.

In the U.S., in 2006, the Council of Better Business Bureaus (CBBB) launched the Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI)24. To date, the CFBAI includes 17 companies; four (Cadbury, Coca-Cola, Hershey and Mars) pledged not to engage in any advertising of food or beverage products on programming primarily directed to children under age 12 and the remainder pledged to engage in 100% “better-for-you” advertising defined by each company25. Previous work that assessed the nutritional content of children's exposure to food and beverage ads used pre-CFBAI data17 and recent post-CFBAI analyses were limited to specific products such as cereal14 or fast food20 or specific programming18.

This study provided a trend analysis of total food-related (food, beverage and restaurant) advertising exposure among children and a nutritional analysis of all food and beverage product ads seen by children, pre- and post-CFBAI implementation. Nutrient content was assessed for saturated fat, sugar, sodium and fiber. Analyses were undertaken for children ages 2–5 and 6–11, by product category, and by parent company to assess how the CFBAI has changed the nutritional landscape of food advertising seen by children.

Methods

Exposure was assessed using television ratings data from Nielsen Media Research26 for all food-related television advertisements in calendar years 2003, 2005, 2007 and 2009. Ratings were assessed separately for children 2–5 and 6–11 years old. Annual age-specific targeted rating points captured exposure to broadcast network, cable network, syndicated and spot television advertising from all programming (except Spanish language programming). In 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009, respectively, 4,436(1604), 4,928(1665), 5,392(1834), 6602(1804) food-related brands(food and beverage brands only) fell into 163(159), 168(164), 175(171), and 182(178) food-related product(food and beverage product only) categories17,19. The food-related product categories were then categorized into seven broad categories: cereals, sweets, snacks, beverages, other food products, fast food restaurants and full-service restaurants. The most commonly advertised items in the “other” category included yogurt, frozen and prepared entrees, and ready to eat soups. Analyses assessed trends in exposure to food-related advertisements for each category. Saturated fat, sugar, sodium and fiber content were assessed for the five product specific categories. Nutritional content of restaurant ads was not assessed given that many ads did not market a specific product, sources for nutritional information on restaurants are limited, and nutritional content of fast food restaurants was recently assessed in another study20.

Information on grams (g) of saturated fat, sugar and fiber, and milligrams (mg) of sodium and information on total energy calories (Kcal) used in the computation of nutritional indicators were determined in order from the following: (1) the Nutrient Data System for Research; (2) US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Nutrient Data base; (3) nutrition facts panels on the product's label; and, (4) manufacturer's website. Nutritional information on 53.6%, 3.2%, 4.5%, and 32.6% of the products was gathered using these methods, respectively. Nutritional information was unavailable for 6.1% of advertised products because they were either nonspecific (4.5%) (i.e., Dairy Association or general food company advertisement) or the information was not contained in the above sources (1.6%). Using these data, for each age group and by food category, we assessed exposure to food product advertising in terms of mean percentage of Kcal from saturated fat and sugar and mean mg of sodium and g of fiber per 50g serving.

Nutrient content of products was classified as high in saturated fat or sodium using National Academy of Sciences (NAS) standards for foods sold in schools27. A food was “high saturated fat” if it contained >10% of total calories from saturated fat (nuts, nut butter and seeds exempted). Products containing >200mg of sodium per 50g serving were classified as “high sodium”. High sugar products were defined based on recommendations in the NAS dietary reference intakes report28 that no more than 25% of total calories come from added sugars; thus we classified products as “high sugar” if >25% of kcal came from sugar (whole fruits, 100% juice, and plain white milk exempted). The nutrient content data for each advertised product were weighted by age- and year-specific television ratings to provide actual exposure measures to the nutritional content of the food and beverage product advertisements.

Results

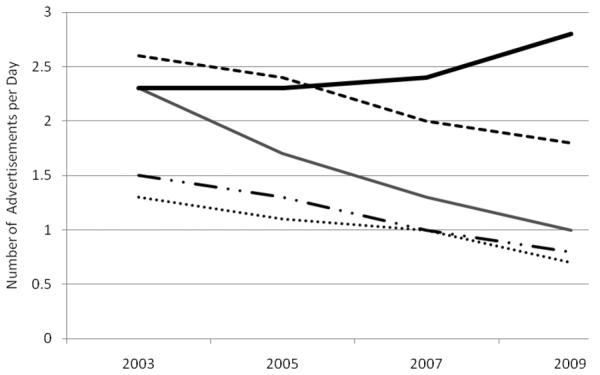

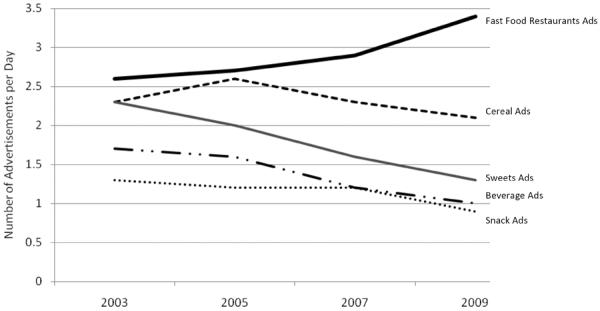

In 2009, children ages 2–5 and 6–11 saw, on average, 10.9 and 12.7 food-related ads per day, respectively (Table 1). There was a consistent downward trend in exposure, with a 17.8% and 6.9% drop, respectively, between 2003 and 2009. The largest percentage reduction was for sweets ads which fell by 55.1% and 44.0% among children ages 2–5 and 6–11, respectively. Exposure to beverage ads fell over 40% among both age groups, as did exposure to snack product ads among younger children. Overall, exposure to food and beverage product advertising fell 32.5%, and 21.7% among 2–5 and 6–11 year olds, respectively. Between 2003 and 2009, exposure to fast food advertising increased among 2–5 and 6–11 year olds by 21.1%, and 30.8%, respectively, with more than half of this increase between 2007 and 2009. By 2009, children 2–5 and 6–11 years old, respectively, saw 2.8 and 3.4 fast food ads, on average, daily (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Children's Exposure to Food-related Television Advertisements and Nutrition Indicators of Food and Beverage Products, by Age, by Product Category, and by Year

| All Children Aged 2–5 Years | All Children Aged 6–11 Years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | %Change 2003–09 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | %Change 2003–09 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Total # Food-related Ads Per Day | 13.3 | 12.1 | 11.5 | 10.9 | −17.8% | 13.7 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 12.7 | −6.9% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Total # Food and Beverage Ads Per Day | 10.1 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 6.8 | −32.5% | 10.1 | 9.7 | 8.9 | 7.9 | −21.7% |

| High saturated fat | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 1.6 | −47.1% | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 1.9 | −38.3% |

| High sugar | 7.3 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 4.2 | −42.2% | 7.2 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 4.9 | −32.1% |

| High sodium | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.0 | −30.0% | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.5 | −15.8% |

| High saturated fat, sugar or sodium | 9.5 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 5.9 | −37.9% | 9.5 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 6.9 | −27.7% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Beverages | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | −43.0% | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.0 | −40.9% |

| High saturated fat | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −75.0% | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −75.0% |

| High sugar | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | −58.6% | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | −55.5% |

| High sodium | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| High saturated fat, sugar or sodium | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | −59.7% | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | −57.2% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Cereal | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 | −30.4% | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | −11.5% |

| High saturated fat | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| High sugar | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.6 | −34.9% | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.8 | −16.8% |

| High sodium | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.6 | −34.2% | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.8 | −16.1% |

| High saturated fat, sugar or sodium | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | −32.9% | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.0 | −14.8% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Snacks | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.7 | −43.5% | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 | −32.0% |

| High saturated fat | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −68.6% | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −64.7% |

| High sugar | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | −56.6% | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | −45.5% |

| High sodium | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | −28.6% | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | −19.6% |

| High saturated fat, sugar or sodium | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.7 | −44.2% | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 | −33.3% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Sweets | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | −55.1% | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | −44.0% |

| High saturated fat | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | −55.6% | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | −45.8% |

| High sugar | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.8 | −60.5% | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | −51.0% |

| High sodium | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −63.2% | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −52.6% |

| High saturated fat, sugar or sodium | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 | −57.2% | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.1 | −46.4% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Other | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.4 | −2.0% | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 | +8.1% |

| High saturated fat | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | −23.5% | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.0 | −13.4% |

| High sugar | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | +2.2% | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | +15.3% |

| High sodium | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | −20.1% | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | −10.1% |

| High saturated fat, sugar or sodium | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.1 | −8.5% | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 | +1.3% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Total # of Restaurant Ads Per Day | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 4.1 | +28.8% | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.8 | +35.3% |

| Fast Food Restaurants | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.8 | +21.1% | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.4 | +30.8% |

| Full Service Restaurants | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | +48.9% | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | +49.5% |

@ The Nielsen Company 2009.

Note: % Change calculations were based on two decimal points.

Figure 1.

Exposure to Food-related Advertisements for Selected Categories for Children 2–5 Years Old, by Year

Figure 2.

Exposure to Food-related Advertisements for Selected Categories for Children 6–11 Years Old, by Year

Table 1 also shows changes in the number of ads for products high in saturated fat, sugar, and sodium or high in any of these, reflecting changes in exposure, the mix of items advertised, and the nutritional content of advertised products. Exposure fell more for high versus low-sugar and saturated fat items across all food categories. Exposure to the number of foods ads seen, on average, each day that were high in saturated fat, sugar or sodium (SAFSUSO) fell by 37.9% and 27.7% among 2–5 and 6–11 year olds, respectively, between 2003 and 2009.

Tables 2 and 3 present nutritional content information over time by product category. In 2009, 86% of food and beverage ads seen by children were high in SAFSUSO, down from about 94% in 2003. While the mean percentage of calories from sugar fell in nearly all product categories, it remained high making up more than a third, on average, of calories in food product ads seen by children. There was some reduction in the sugar content of cereal ads; in 2009, 34% of total calories were from sugar. As a result, 86% of children's cereal ad exposure in 2009 was for high sugar cereals. Despite the continued prevalence of high sugar cereal ads, there were increases in the fiber content in cereal ads seen by children which almost doubled from a mean of 1.6g (ages 2–5) and 1.7g (ages 6–11) per 50g serving, in 2003, to 2.9g per 50g serving for both age groups, in 2009.

Table 2.

Nutritional Content of Food and Beverage Product Advertisements Viewed by Children, by Age, by Product Category, by Year

| Mean %Kcal from Saturated Fat |

Mean % Kcal from Sugar |

Mean mg of Sodium per 50g serving |

Mean g of Fiber per 50g serving |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | % Change 03–09 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | % Chang e 03–09 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | % Change 03–09 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | % Change 03–09 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Children Aged 2 5 Years | ||||||||||||||||||||

| All Foods | 7.3 | 6.1 | 6.9 | 6.8 | −6.6% | 43.4 | 40.9 | 37.3 | 36.7 | −15.4% | 193.8 | 222.3 | 194.4 | 222.1 | +14.6% | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | +61.9% |

| Beverages | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.1 | −20.7% | 84.3 | 69.1 | 69.9 | 70.9 | −15.9% | 11.3 | 21.5 | 54.4 | 13.8 | +22.2% | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +175.0% |

| Cereal | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2.0 | −17.0% | 39.0 | 36.9 | 36.8 | 34.1 | −12.5% | 294.3 | 301.9 | 296.9 | 282.2 | −4.1% | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.9 | +79.4% |

| Snacks | 7.0 | 5.9 | 7.8 | 6.3 | −10.1% | 35.2 | 29.4 | 26.0 | 28.2 | −20.0% | 248.3 | 255.8 | 251.2 | 255.2 | +2.8% | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.9 | +132.5% |

| Sweets | 11.8 | 8.9 | 9.9 | 13.1 | +10.9% | 48.1 | 54.0 | 46.0 | 43.3 | −10.0% | 91.7 | 78.2 | 76.0 | 89.6 | −2.3% | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | +8.6% |

| Other | 11.4 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.9 | −12.8% | 24.8 | 22.8 | 23.8 | 26.1 | +5.5% | 266.1 | 362.5 | 215.5 | 298.9 | +12.3% | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | +18.3% |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Children Aged 6–11 Years | ||||||||||||||||||||

| All Foods | 7.4 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 6.9 | −5.6% | 44.1 | 41.5 | 38.1 | 36.7 | −16.7% | 190.6 | 209.0 | 193.9 | 222.3 | +16.6% | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | +61.0% |

| Beverages | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.0 | −12.9% | 84.8 | 69.7 | 72.9 | 71.3 | −15.8% | 10.9 | 21.0 | 54.2 | 13.3 | +21.7% | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +266.7% |

| Cereal | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 2.0 | −18.0% | 38.6 | 37.1 | 36.9 | 34.0 | −12.1% | 293.3 | 299.1 | 298.6 | 281.6 | −4.0% | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.9 | +75.2% |

| Snacks | 7.3 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 6.3 | −14.5% | 33.6 | 28.5 | 25.9 | 27.7 | −17.6% | 254.9 | 260.8 | 253.1 | 257.8 | +1.1% | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.9 | +124.4% |

| Sweets | 11.6 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 12.6 | +8.5% | 48.2 | 54.1 | 46.7 | 43.4 | −9.9% | 90.3 | 77.7 | 73.2 | 88.8 | −1.6% | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | +7.2% |

| Other | 11.6 | 11.3 | 10.2 | 10.4 | −10.4% | 24.1 | 22.2 | 23.4 | 25.0 | +4.1% | 280.3 | 332.0 | 219.4 | 311.5 | +11.1% | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | −1.4% |

@ The Nielsen Company 2009.

Note: % Change calculations were based on two decimal points.

Table 3.

Nutritional Indicators of Food and Beverage Product Advertisements Viewed by Children, by Age, by Product Category, by Year

| % High Saturated Fat | % High Sugar | % High Sodium | % High Saturated Fat, Sugar, or Sodium | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Children Aged 2–5 Years | ||||||||||||||||

| All Foods | 30.4% | 32.8% | 26.3% | 23.9% | 72.4% | 66.0% | 63.6% | 62.0% | 42.9% | 43.0% | 45.1% | 44.4% | 93.9% | 88.3% | 88.7% | 86.3% |

| Beverages | 8.0% | 6.8% | 11.7% | 3.5% | 85.7% | 66.1% | 74.4% | 62.7% | 0.0% | 3.1% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 93.2% | 69.4% | 77.5% | 65.5% |

| Cereal | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 92.6% | 89.4% | 91.6% | 86.5% | 93.3% | 87.8% | 90.2% | 88.2% | 98.1% | 97.2% | 96.9% | 94.3% |

| Snacks | 38.6% | 23.2% | 29.1% | 21.3% | 63.4% | 54.0% | 49.0% | 48.5% | 37.2% | 44.0% | 52.5% | 46.8% | 98.4% | 97.7% | 97.4% | 97.4% |

| Sweets | 51.4% | 36.2% | 44.5% | 50.7% | 88.3% | 82.3% | 77.9% | 77.9% | 8.5% | 11.4% | 5.6% | 6.9% | 91.6% | 90.7% | 86.6% | 87.6% |

| Other | 47.9% | 38.8% | 41.1% | 37.5% | 36.0% | 32.9% | 35.4% | 38.0% | 54.0% | 44.4% | 46.9% | 44.1% | 90.0% | 83.1% | 84.6% | 84.2% |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Children Aged 6–11 Years | ||||||||||||||||

| All Foods | 30.5% | 32.3% | 25.7% | 24.0% | 71.4% | 66.2% | 64.5% | 61.8% | 41.4% | 42.0% | 45.2% | 44.4% | 93.6% | 88.2% | 89.3% | 86.5% |

| Beverages | 6.9% | 5.5% | 8.6% | 3.3% | 85.6% | 68.3% | 76.0% | 64.1% | 0.0% | 3.1% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 93.2% | 71.5% | 79.1% | 66.9% |

| Cereal | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 91.6% | 89.9% | 92.1% | 85.8% | 92.9% | 87.3% | 90.5% | 87.6% | 97.8% | 97.1% | 97.1% | 93.9% |

| Snacks | 39.6% | 23.4% | 29.0% | 20.6% | 60.4% | 52.6% | 49.1% | 47.8% | 39.7% | 44.9% | 52.3% | 47.1% | 98.0% | 97.3% | 97.8% | 97.2% |

| Sweets | 50.7% | 35.2% | 42.8% | 49.1% | 88.1% | 82.5% | 77.9% | 77.4% | 8.1% | 11.5% | 5.3% | 7.0% | 90.9% | 90.1% | 85.5% | 87.0% |

| Other | 48.1% | 39.4% | 42.3% | 38.4% | 34.3% | 31.5% | 34.5% | 36.6% | 56.0% | 45.3% | 48.8% | 46.6% | 90.6% | 83.5% | 85.9% | 85.0% |

@ The Nielsen Company 2009.

Sweets ads generally remained high in sugar (approximately 77% in 2009, down from 88% in 2003). And, for all product categories but sweets, the mean percentage of calories from saturated fat fell. In particular, exposure to high saturated fat snack product ads fell from 38.6% to 21.3% and from 39.6% to 20.6% among 2–5 and 6–11 year olds, respectively, between 2003 and 2009. The greatest reduction in exposure to high sugar ads also was for snack products; in 2003, 63.4% and 60.4% were high sugar among children 2–5 and 6–11, respectively; by 2009 just under half of snack products were high sugar. As with cereal, there was an increase in the fiber content of snack product ads seen, with fiber content more than doubling between 2003 and 2009 from 0.8g to 1.9g per 50g serving for 2–5 years old and 0.9g to 1.9g per 50g serving for 6–11 year olds. However, children were increasingly exposed to ads for higher sodium products with food products having, on average, more than 200 mg of sodium per 50g serving by 2009. And, this was driven primarily by an increase in sodium among snack product ads seen; the proportion of high sodium snack products increased between 2003 and 2009 from 37.2% to 46.8% and 39.7% to 47.1% among 2–5 and 6–11 year olds, respectively. Thus, although fewer snack product ads were high in saturated fat and sugar, as a result of the increased sodium, 97% of snack ads seen by children in 2009 were high in SAFSUSO.

Across all product categories, the largest improvements were for beverages where 65.5% and 66.9% of beverage ads seen by 2–5 and 6–11 year olds were high in SAFSUSO in 2009, down from 93.2% in 2003. Among advertised beverages, two thirds of the calories came from sugar and over 60% of beverage ads were for high sugar drinks in 2009, down from about 85% in 2003. By beverage type, as shown in Table 4, the largest reduction in exposure was to regular soft drink ads (−67.9% and −67.6%, respectively, for ages 2–5 and 6–11); however, exposure to regular soft drink ads flattened for 2–5 year olds and increased for 6–11 year olds between 2007 and 2009. For both age groups, fruit drink ad exposure trended downward from 2003 to 2007 but then doubled between 2007 and 2009, although overall exposure was lower in 2009 than it was in 2003. Additionally, children have recently been exposed to high-sugar bottled water ads. Exposure to low-sugar beverage ads increased by 63.2.0% and 52.2% among 2–5 and 6–11 year olds. Exposure to diet soft drink ads increased substantially between 2003 and 2007 but exposure has fallen since 2007 resulting in no change among children 2–5 and a 33.3% increase among children 6–11 between 2003 and 2009.

Table 4.

Children's Exposure to Beverage Advertisements, by Age, by Beverage Type, by Year

| 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | % Change 2007–2009 | % Change 2003–2009 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Children Aged 2–5 Years | High Sugar Beverage Ads | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | −30.7% | −55.2% |

| Regular Soft Drinks | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0% | −67.9% | |

| Fruit Drinks | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | +111.1% | −51.3% | |

| Bottled Water (Sugar Added) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −50.0% | +500.0% | |

| Drinks - Isotonic | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −50.0% | −61.5% | |

| Other High Sugar Beverage | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | −62.9% | −63.9% | |

|

| |||||||

| Low Sugar Beverage Ads | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | +19.2% | 63.2% | |

| Diet Soft Drinks | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −40.0% | 0.0% | |

| Fruit Juices (100%) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +10.0% | +10.0% | |

| Bottled Water | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Milk (Unfavored) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | +50.0% | 0.0% | |

| Other Low Sugar Beverage | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +57.1% | +120.0% | |

|

| |||||||

| Children Aged 6–11 Years | High Sugar Beverage Ads | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.6 | −28.4% | −53.0% |

| Regular Soft Drinks | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +9.1% | −67.6% | |

| Fruit Drinks | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | +118.2% | −42.9% | |

| Bottled Water (Sugar Added) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −53.3% | +600.0% | |

| Drinks - Isotonic | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −53.8% | −60.0% | |

| Other High Sugar Beverage | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | −59.5% | −60.5% | |

|

| |||||||

| Low Sugar Beverage Ads | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | +25.0% | +52.2% | |

| Diet Soft Drinks | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −33.3% | +33.3% | |

| Fruit Juices (100%) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +20.0% | 0.0% | |

| Bottled Water | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Milk (Unfavored) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | +100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Other Low Sugar Beverage | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +62.5% | +160.0% | |

@ The Nielsen Company 2009.

Note: % Change calculations were based on two decimal points.

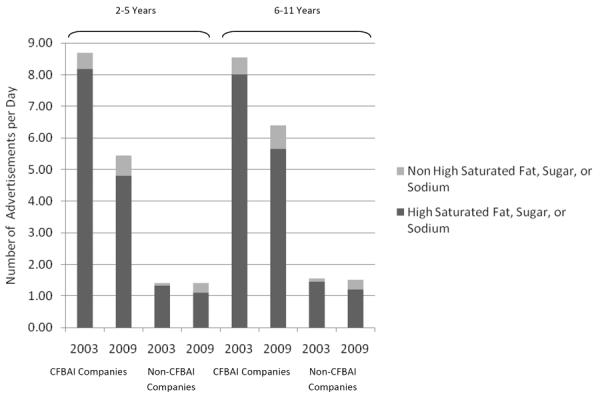

Results tabulated by parent companies and membership in the CFBAI (based on participation as of 2009) are shown in Table 5 and Figure 3. The results show that there was a higher reduction in the number of ads from CFBAI versus non-CFBAI companies seen by 2–5 years olds (−37.5% versus −1.4%) and 6–11 year olds (−25.1% versus −2.6%). However, in terms of nutritional content, there were greater percentage improvements for products from non-CFBAI companies. Between 2003 and 2009, the proportion of CFBAI versus non-CFBAI company ads, respectively, that were high in SAFSUSO fell by 6.2% versus 15.3% among 2–5 year olds and 5.8% versus 15.2% among 6–11 year olds. With regard to changes in the number of fast food ads seen by 2–5 year olds, the increase in exposure from the two CFBAI fast food companies was 4.2% compared to a 39.8% increase in exposure to non-CFBAI fast food ads. However, among 6–11 year olds the increase in exposure to CFBAI fast food ads was 28.0%, almost as high as the non-CFBAI increase of 33.1%.

Table 5.

Children s Exposure to Food-related Advertising and by Nutritional Indicators for Food and Beverage Products by Parent Company, by Age, by Year

| # of Ads per Day | % of Ads High in Saturated Fat, Sugar, or Sodium | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | % Change 2003–09 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | % Change 2003–09 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Children Aged 2–5 Years | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| CFBAI Companies | ||||||||||

| Burger King | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | +5.1% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||

| Cadbury | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | +16.7% | 0.0% | 43.1% | 59.2% | 17.2% | -- |

|

| ||||||||||

| Campbell | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | +3.4% | 88.2% | 69.4% | 82.0% | 70.7% | −19.8% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Coca-Cola | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −57.9% | 93.9% | 54.0% | 54.1% | 41.4% | −56.0% |

|

| ||||||||||

| ConAgra | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | +3.8% | 63.9% | 63.1% | 79.9% | 63.1% | −1.2% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Dannon | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | +22.2% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 99.9% | 99.9% | −0.1% |

|

| ||||||||||

| General Mills | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.0 | −16.0% | 97.2% | 99.3% | 98.2% | 97.4% | +0.2% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hershey | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −34.5% | 81.5% | 89.7% | 70.8% | 100.0% | +22.7% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kellogg | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.7 | −50.7% | 98.8% | 97.0% | 97.5% | 89.2% | −9.8% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kraft | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | −51.6% | 97.7% | 95.9% | 96.0% | 94.3% | −3.5% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mars | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −64.3% | 95.5% | 90.1% | 74.0% | 75.1% | −21.4% |

|

| ||||||||||

| McDonalds | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | +3.7% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||

| Nestle | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −35.7% | 91.0% | 75.3% | 67.3% | 72.3% | −20.5% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pepsi | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | −70.7% | 91.7% | 85.4% | 86.6% | 81.6% | −11.0% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Post | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −46.5% | 95.2% | 99.9% | 98.7% | 96.7% | +1.5% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Unilever | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −65.0% | 95.1% | 85.0% | 92.7% | 92.2% | −3.1% |

|

| ||||||||||

| CFBAI Companies Food and Beverage Products Subtotal | 8.7 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 5.4 | −37.5% | 94.0% | 89.7% | 89.9% | 88.2% | −6.2% |

| Non CFBAI Companies Food and Beverage Products Subtotal | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | −1.4% | 93.3% | 80.6% | 81.7% | 79.1% | −15.3% |

|

| ||||||||||

| CFBAI Fast Food Companies Subtotal | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | +4.2% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Non CFBAI Fast Food Companies Subtotals | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.5 | +39.8% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Non CFBAI Full Service Restaurant Subtotal | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | +48.9% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||

| Total CFBAI Companies | 9.9 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 6.7 | −32.4% | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| TOTAL | 13.3 | 12.1 | 11.5 | 10.9 | −17.8% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||

| Children Aged 6–11 Years | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| CFBAI Companies | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Burger King | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | +25.0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||

| Cadbury | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | +42.9% | 0.0% | 41.8% | 61.5% | 24.3% | -- |

|

| ||||||||||

| Campbell | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | +17.2% | 88.5% | 69.0% | 82.4% | 69.6% | −21.4% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Coca-Cola | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −54.5% | 94.5% | 55.4% | 55.8% | 44.8% | −52.6% |

|

| ||||||||||

| ConAgra | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | +25.0% | 66.3% | 65.7% | 82.1% | 62.8% | −5.2% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Dannon | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | +27.8% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 99.9% | 99.9% | −0.1% |

|

| ||||||||||

| General Mills | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 | +6.5% | 96.6% | 99.1% | 98.3% | 97.3% | +0.7% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hershey | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −20.0% | 79.6% | 89.3% | 72.1% | 100.0% | 25.7% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kellogg | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.9 | −36.8% | 98.7% | 97.1% | 97.6% | 88.7% | −10.1% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kraft | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | −40.8% | 97.6% | 96.2% | 96.4% | 94.9% | −2.7% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mars | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | −56.0% | 95.3% | 90.2% | 72.7% | 74.0% | −22.3% |

|

| ||||||||||

| McDonalds | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | +29.9% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||

| Nestle | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −33.3% | 92.6% | 74.5% | 72.0% | 73.7% | −20.5% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pepsi | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | −67.7% | 90.8% | 84.5% | 87.5% | 82.4% | −9.3% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Post | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −32.6% | 94.7% | 99.9% | 99.0% | 96.9% | +2.4% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Unilever | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −55.6% | 96.8% | 83.0% | 90.6% | 91.8% | −5.2% |

|

| ||||||||||

| CFBAI Companies Food and Beverage Products Subtotal | 8.6 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 6.4 | −25.1% | 93.7% | 89.3% | 90.3% | 88.2% | −5.8% |

| Non CFBAI Companies Food and Beverage Products Subtotal | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 | −2.6% | 93.6% | 82.5% | 82.4% | 79.4% | −15.2% |

|

| ||||||||||

| CFBAI Fast Food Companies Subtotal | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.5 | +28.0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Non CFBAI Fast Food Companies Subtotals | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | +33.1% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Non CFBAI Full Service Restaurant Subtotal | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | +49.5% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||

| Total CFBAI Companies | 9.7 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 7.9 | −18.7% | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| TOTAL | 13.7 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 12.7 | −6.8% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

@ The Nielsen Company 2009.

Note: % Change calculations were based on two decimal points.

Figure 3.

Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertisements by High Saturated Fat, Sugar, or Sodium Status, by CFBAI Membership, by Age, and by Year

Whereas, exposure to CFBAI food and beverage product ads fell by 37.5% and 25.1% for 2–5 and 6–11 children, respectively, the single largest advertiser to children, General Mills, had a smaller 16.0% reduction in ads seen by children 2–5 years old and a 6.5% increase in ads seen by 6–11 year olds. Further, among the General Mills ads that continued to be viewed, there was no improvement in the overall nutritional content of advertised products with 97.4% and 97.3% of ads for the respective age groups being for products high in SAFSUSO in 2009. Among the next largest advertisers, between 2003 and 2009, 2–5 year olds saw approximately 50% fewer ads for Kellogg and Kraft products and 6–11 year olds were exposed to 36.8% and 40.8% fewer Kellogg and Kraft food ads, respectively. However, the vast majority (88.7% to 94.9%) of ad exposures among children in 2009, from these companies were for products high in SAFSUSO. Among other CFBAI companies, there were greater than 50% reductions in children's exposure to ads from Pepsi, Unilever, Mars, and Coca-Cola between 2003 and 2009. However, in 2009, the majority of the ads from all but two (Cadbury and Coca-Cola) of the CFBAI companies seen by children were for products high in SAFSUSO.

Discussion

This study provided the first comprehensive examination of children's total exposure to food-related advertising pre- and post-implementation of the industry's self-regulatory CFBAI. The results showed that exposure to food and beverage products high in SAFSUSO fell 37.9% and 27.7% among children 2–5 and 6–11 years old, respectively. Among advertised products, the largest nutritional improvements were for beverages. Whereas fiber content increased substantially in cereals, 94% of cereal ads seen in 2009 were high in SAFSUSO. Further, although the sugar and saturated fat content fell in snacks product ads, as a result of increases in sodium most of the snack ads remained unhealthy. Increases in sodium content among the advertised products indicated that greater attention needs to be placed on commitments to reducing sodium content, consistent with recent calls for population-wide reductions in sodium intake9. Overall, despite reductions in advertising exposure, in 2009, 86% of the food and beverage ads seen by children were for products high in SAFSUSO, down from 94% in 2003. These study findings are consistent with other recent studies that documented the poor nutritional content of cereal ads and ads on children's programming advertised post-CFBAI14,18.

Reductions in exposure to food and beverage product advertising were greater among CFBAI companies compared to non-CFBAI companies. In particular, there were 50% or greater reductions in exposure to ads from Kellogg, Kraft, Mars, Pepsi, Unilever, and Coca-Cola. CFBAI companies accounted for approximately 80% of children's exposure to food and beverage products. Despite the marked reductions in CFBAI exposure, the vast majority (88%) of CFBAI company ads seen, in 2009, continued to be for high SAFSUSO products. Moreover, there were substantial variations in both changes in the amount of advertising seen by children and the nutritional content of the advertised products across CFBAI companies, highlighting the lack of common standards within the CFBAI. Further, there were differences across age groups, with often limited improvement among 6–11 year olds, suggesting that the pledges do not adequately address the reach of advertising to children.

Fast food advertising exposure increased substantially and by 2009 it was the largest category of food-related advertising exposure for children of both age groups. The increase in exposure was lower for CFBAI versus non-CFBAI member ads, although to a lesser extent among 6–11 year olds. CFBAI company membership accounted for a much lower proportion of fast food compared to food and beverage product exposure; accounting for about 45% of fast food ad exposure among children. These study findings are concerning given the recent research that demonstrated the poor nutritional content of fast food advertising to children20 and studies that have found significant associations between fast food advertising and children's weight outcomes22,23.

In assessing the CFBAI self-regulatory pledges, we note that these apply to children's programming only, albeit with different definitions on what constituted such programming. In this study, we examined exposure to all advertising seen by children, not just advertising on children's programming. Thus, the study results assessed the extent to which self-regulation impacted the landscape of all food-related advertisements seen. Further, our nutritional standards which drew on the nutritional recommendations from the NAS were not necessarily reflected in the CFBAI individual members' self-defined nutritional standards.

In conclusion, examining children's advertising exposure using television ratings data over time, the study results, on the one hand, showed promising reductions in exposure to food and beverage advertisements but on the other hand showed that of the vast majority of the ads that children saw, in 2009, were for products high in SAFSUSO. Further, between 2003 and 2009 children were exposed to an ever increasing number of fast food ads. If self-regulation is to continue as the modus operandi, the results suggest that several substantive changes are needed within the CFBAI in order to further improve the landscape of TV food advertising seen by U.S. children. These include the need to: 1) develop common nutritional standards based on governmental agency guidelines; 2) standardize and broaden the definition of what constitutes children's programming since the reach of unhealthful ads in other programming is high; and, 3) increase the membership of the CFBAI, particularly among fast food companies to stem the growing barrage of fast food ads seen by children.

The CBBB has reported the CFBAI member advertising practices directed at children's programming to be in compliance as per their self-defined pledges29. In this regard, the development and application of formal nutritional standards and definitions of child programming is critical to evaluate self-regulation. Continued monitoring of children's overall exposure and exposure on children's programming is clearly needed. If continued monitoring shows minimal further reductions in food-related advertising exposure and/or little improvement in the nutritional content of food and beverage advertisements seen by children, then formal governmental intervention may be warranted.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge research support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through the Bridging the Gap program for the ImpacTeen project and from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant number 1R01CA138456-01A1. Dr. Powell had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- (1).Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of High Body Mass Index in US Children and Adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in U.S. between 1977 and 1996: Similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res. 2002;10:370–378. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: A guide for practitioners. Pediatrics. 2006;117:544–559. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bray GA, Popkin BM. Dietary fat intake does affect obesity! Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1157–1173. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357:505–508. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bowman SA, Gortmaker SL, Ebbeling CB, Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey. Pediatrics. 2004;113:112–118. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Appel LJ, Frohlich ED, Hall JE, et al. Circulation. CIR; 2011. The Importance of Population-Wide Sodium Reduction as a Means to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: A Call to Action From the American Heart Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).TVB Local Media Marketing Solutions. TV Basics. 2011 www.tvb.org.

- (11).Institute of Medicine . Food marketing to children and youth: Threat or opportunity? The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Federal Trade Commission . Marketing food to children and adolescents: A review of industry expenditures, activities, and self-regulations. FTC; Washington, DC: 2009. http://www.ftc.gov/os/2008/07/P064504foodmktingreport.pdf. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Batada A, Seitz MD, Wootan MG, Story M. Nine out of 10 food advertisements shown during Saturday morning children's television programming are for foods high in fat, sodium, or added sugars, or low in nutrients. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD, Sarda V, Weinberg M, Speers S, Thompson J, Ustjanauskas A, Cheyne A, Bukofzer E, Dorfman L, Byrnes-Enoch H. Cereal FACTS. Evaluating the nutrition quality and marketing of children's cereals. 2009 www.cerealfacts.org.

- (15).Stitt C, Kunkel D. Food Advertising During Children's Television Programming on Broadcast and Cable Channels. Health Communication. 2008;23:573–584. doi: 10.1080/10410230802465258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Schwartz MB, Vartanian LR, Wharton CM, Brownell KD. Examining the nutritional quality of breakfast cereals marketed to children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:702–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120:576–583. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kunkel D, McKinley C, Wright P. The Impact of Industry Self-Regulation on the Nutritional Quality of Foods Advertised on Television to Children. Children Now; Oakland, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ. Trends in Exposure to Television Food Advertisements Among Children and Adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:794–802. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Fast Food F.A.C.T.S.: Evaluating Fast Food Nutrition and Marketing to Youth. Yale University, Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (21).The Henry J.Kaiser Family Foundation . The role of media in childhood obesity. The Henry J.Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chou SY, Rashad I, Grossman M. Fast Food Restaurant Advertising on Television and Its Influence on Childhood Obesity. The Journal of Law and Economics. 2008;51:599–618. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: Associations with children's fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Council of Better Business Bureaus . Changing the Landscape of Food & Beverage Advertising: The Children's Food & Beverage Advertising Initiative In Action A Progress Report on the First Six Months of Implementation: July-December 2007. Council of Better Business Bureaus, Inc.; Arlington, VA: 2008. http://www.bbb.org/us/storage/16/documents/CFBAI/ChildrenF&BInit_Sept21.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Council of Better Business Bureaus BBB Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative:Food and Beverage Products that Meet Participants' Approved Nutrition Standards1. 2009 http://www.bbb.org/us/storage/0/Shared%20Documents/Aug_Product_List_final1.pdf.

- (26).The Nielsen Company Nielsen Media Research. 2007 www.nielsenmedia.com.

- (27).National Academy of Science. Institute of Medicine . Nutrition Standards for Foods in School: Leading the Way Toward Healthier Youth. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (28).National Academy of Science. Institute of Medicine . Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids (macronutrients) The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Council of Better Business Bureaus The children's food & beverage advertising initiative in action: A report on complience and implementation during 2009. 2009 Progress Report. 2010 available at: http://www.bbb.org/us/storage/0/Shared%20Documents/BBBwithlinks.pdf.