Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is associated with higher levels of autoantibodies and IL-17. Here, we investigated if ectopic lymphoid follicles and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from RA patients exhibit increased activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), and if increased AID is correlated with serum levels of autoantibodies and IL-17. The results of immunohistochemical staining showed that organized germinal centers were observed in 6 of the 12 RA synovial samples, and AID+ cells were found almost exclusively in the B-cell areas of these follicles. Aggregated but not organized lymphoid follicles were found in only one OA synovial sample without AID+ cells. Significantly higher levels of AID mRNA (Aicda) detected by RT-PCR were found in the PBMCs from RA patients than PBMCs from normal controls (p<0.01). In the PBMCs from RA patients, AID was expressed predominately by the CD10+IgM+CD20+ B-cell population and the percentage of these cells that expressed AID was significantly higher than in normal controls (p < 0.01). Aicda expression in the PBMCs correlated significantly and positively with the serum levels of rheumatoid factor (RF) (p ≤ 0.0001) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) (p = 0.0005). Serum levels of IFN-γ (p = 0.0005) and IL-17 (p = 0.007), but not IL-4, also exhibited positive correlation with the expression of AID. These results suggest that the higher levels of AID expression in B cells of RA patients correlate with, and may be associated with the higher levels of T helper cell cytokines IFN-γ and IL-17, leading to the development of anti-CCP and RF.

Introduction

Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) is essential for somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class-switch recombination (CSR) during an antibody response to an antigen [1–3]. Nacionales et al [4] reported that proliferating T and B lymphocytes were found within ectopic lymphoid tissue of autoimmune mice, AID was expressed, and class-switched B cells were present. We have shown recently that in the BXD2 mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [5, 6], the increased expression of AID in B cells results in increased SHM and the formation of pathogenic IgG autoantibodies [7]. We also found that increased levels of IL-17 predisposes to the development of spontaneous autoreactive germinal centers (GCs) [8]. These GCs have a unique structure based on increased T cell B cell interaction due to IL-17 induced up regulation of the regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins which desensitize responses to chemokines.

RA is an autoimmune disease associated with autoantibodies and spontaneous ectopic GCs in the synovium [9]. Patients with RA produce several autoantibodies that are thought to contribute to disease onset and severity, including antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) and other citrullinated proteins [10–13]. Cytokines including TNF-α, IFN–γ and IL-4 have been associated with increased production of anti-CCP antibodies [14–16]. Recently, we found that monoclonal autoantibodies produced by hybridomas derived from BXD2 mice can induce an erosive arthritis [7, 17]. Further, we showed that IL-17 plays a central role of induction of these pathogenic cytokines by promoting GC formation [8]. These arthritis-inducing autoantibodies include rheumatoid factor (RF) as well as autoantibodies with specificity for heat-shock proteins and structural proteins [17]. Sequence analysis of the VH and VL genes of these autoantibodies revealed enhanced SHM and CSR that were associated with high expression of AID in the GCs of the spleen [7].

The information available on the expression of AID in patients with RA or other autoimmune disease is limited. It has been reported that a rheumatoid factor-producing lymphoblastoid cell line derived from a patient with RA expresses AID (4). In Sjögren’s syndrome, AID is expressed by follicular dendritic cells in the minor salivary gland [18], although CD19+ CD27+ memory B cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome do not express AID [19]. We therefore analyzed the expression of AID in the synovia and PBMCs of patients with RA and control subjects.

Material and Methods

Subjects

Synovial tissue samples from 12 patients with RA (11 females and 1 male), and 11 patients with OA (9 females and 2 males) were obtained from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Tissue Procurement Center. For analysis of PBMCs, a total of 22 patients with RA (14 females and 8 males) were recruited by sequential selection from the Kirklin Clinic of UAB and the Birmingham Veterans Administration Research Center. The patients’ age has a mean of 58 years with an age-range from 46 to 78 years old. Thirteen subjects were Caucasian and nine subjects were African-American. Subjects have a mean duration of disease of 8.5 years (range 3 years to 32 years). Eighty-two percent (81.8%) of the patients (18 of 22) were treated with Methotrexate and 54.5% (12 of 22) were being treated with a TNF inhibitor (Enbrel or Remicade) at the time of sample acquisition. An additional 5 healthy subjects (3 females and 2 males) were recruited as normal controls. All RA patients met the American College of Rheumatology 1987 revised criteria for rheumatoid arthritis [20]. These studies were conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the institutional review board at UAB. All participants provided informed consent.

Immunohistochemical analysis of tissue sections

The tissues were fixed in 10% formaldehyde/PBS and paraffin-embedded. Sections (5 µm) were incubated with mouse anti-human CD3 (clone UCHT1; Ancell, Bayport, MN), mouse anti-human CD20 (clone L26; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), rat anti-human AID antibody (Ascenion, www.ascenion.de) (rat IgG2b, clone EK2 5G9), or mouse anti-human Ki67 monoclonal antibody (clone MIB-1, BioGenex, San Ramon, CA), followed by either biotinylated goat-anti-mouse immunoglobulin for CD3, CD20 and Ki67, or biotin-goat-anti-rat Ig for AID. The sections were then subjected to a standard streptavidin-peroxidase technique with the reaction being developed using a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate kit (Biogenex Laboratories, Inc., San Ramon, CA). Negative controls included omission of the primary antibodies.

Total RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and PCR

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque (Sigma–Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) and washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) before use. Total RNA was isolated from 2–5 × 106 PBMCs using TRIzol (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) and converted to cDNA using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MA). Using cDNA, PCR was performed with 1.2 µM primers and 1 × GoTag Green Master Mix (#M7122, Promega, Madison, WI). The primary PCR for Aicda included denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR profile for the GAPDH was similar except that annealing was performed at 56°C. The following primers were used: Aicda forward (Fw), 5'-TAGACCCTGGCCGCTGCTACC-3'; Aicda reverse (Rv), 5'-CAAAAGGATGCGCCGAAGCTGTCTGGAG-3'; Gapdh Fw, 5'-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3'; and Gapdh Rv, 5'- TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA.

Phenotypic analysis and intracellular staining of cells using flow cytometry

The phenotype of the AID-positive PBMCs was determined using flow cytometry procedures. The three- or four-color immunofluorescence staining of cell samples was performed using different combinations of FITC-, PE-, APC-, and Cy5-conjugated antibodies, including anti-CD10, anti-CD20, anti-IgM, and anti-AID. Each experiment included cells incubated with isotype controls (data not shown). For staining of AID, the cells were incubated with FACS permeabilization buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The expression of AID in IgM+CD10+ or IgM+CD10− subsets of CD20+ B-cells was determined by gating on viable CD20high B-cells to exclude CD3+ and other cells. A total of 80,000 to 200,000 events for each sample were recorded and analyzed using an FACS® Caliber (Becton–Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The concentration of the anti-CCP autoantibodies in the sera was quantified using the commercially available DIASTAT™ anti-CCP ELISA kit (Axis-Shield Diagnostics, Ltd., Dundee, UK). The absorbance of the reaction mixture was read at 550 nm using an Emax Precision Microplate Reader (Molecular Device). The results are shown as the concentration in U/ml which was calculated by plotting the ELISA absorbance of each sample against a standard curve.

The serum levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 were evaluated using commercially available ELISA kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The concentration of RF in the sera was quantified using a commercially available IgM and IgG RF ELISA kit following the manufacturer’s protocols (Immco Diagnostics, Buffalo, NY). The absorbance of the reaction mixture was read at 405 nm using an Emax Precision Microplate Reader (Molecular Device, Sunnyvale, CA). The results are shown as the concentration of the RF in IU/ml which was calculated using the following formula: Absorbance of test sample/Absorbance of calibrator D × IU/ml of calibrator D.

Correlation and statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). The two-tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. Correlations between variables were determined by using a linear regression analysis. The frequency of sections containing follicles exhibiting T and B cell interactions or AID-positive follicles in synovial sections from patients with RA and OA were compared using χ2 tests. A p -value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

AID expression is increased in follicular B cells in RA synovial tissue

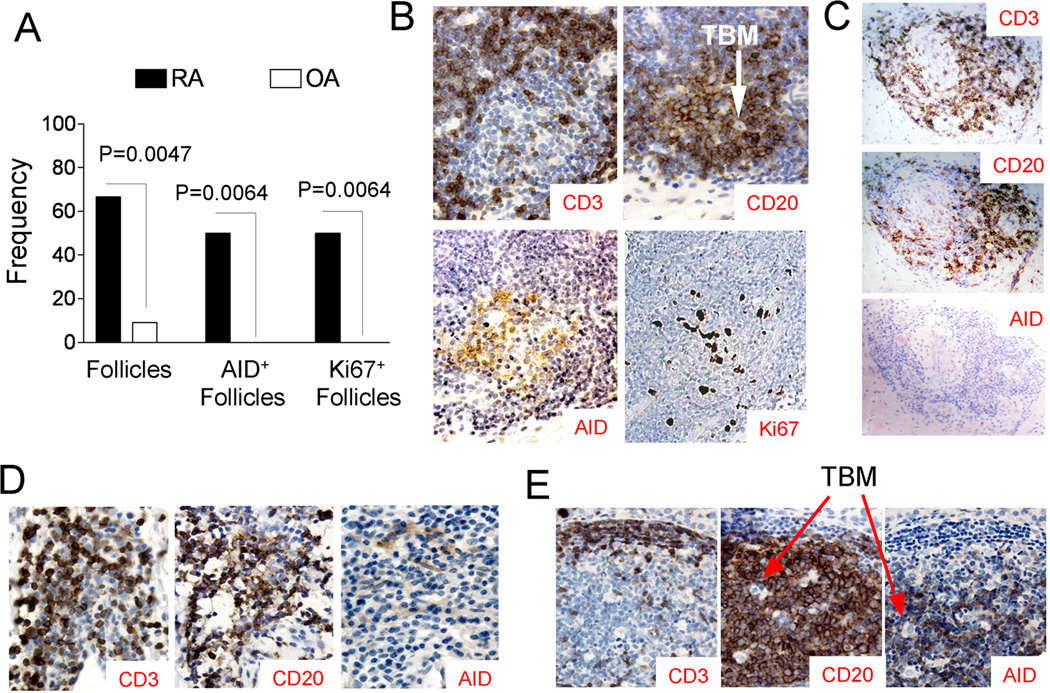

Eight of the 12 synovial samples tested were found to have aggregates of T and B cells that formed lymphoid follicles; whereas, only one out of 11 OA synovial samples contained such structure (Fig. 1A) (p = 0.0047, Chi-square test). A representative, T- and B- interacting follicle in the synovium of a patient with RA is shown in Figure 1B. This follicle, characterized by the presence of tingible body macrophages (TBM), contains a region of Ki67+, CD20+ B cells surrounded by CD3+ T cells. In this follicle, the AID-positive cells are located predominantly in the B-cell region. No staining was observed in the primary antibody deleted control. No AID-positive cells could be seen in the single follicle detected in one of the OA synovial tissue samples (Fig. 1C). Of the 12 synovial samples from patients with RA, six were found to have AID+ and Ki67+ cells in the follicles; whereas none of the eleven OA synovial samples contained any AID+ or Ki67+ follicles (Fig. 1A, p = 0.0064, Chi-square test). Interestingly, positive AID staining in B cells could not be identified in regions of RA synovium rich in T and B cells that did not show a clearly organized follicle of B cells surrounded by T cells (Fig. 1D). As it has been reported that AID is expressed in salivary glands of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome [18], we also analyzed samples of thyroid glands from patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Well-formed follicles with AID+ B-cells were detected and AID+ cells were detected only in the B cells within the GC-like follicles (Fig. 1E) and not in B cells that were not located within these well-organized follicles (data not shown).

Figure 1. AID expression in T- and B- interacting follicles in the synovia of patients with RA.

Paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm thickness) of synovial tissue from patients with RA (N = 12) or OA (N = 11) subjects were incubated with primary antibodies for anti-CD3, anti-CD20, anti-AID, and anti-Ki67, followed by biotinylated goat-anti-mouse Ig or biotinylated goat-anti-rat Ig (for AID) and streptavidin-peroxidase and diaminobenzidine substrate. Sections incubated with the secondary biotinylated antibodies, streptavidin-peroxidase, and substrate were used as negative controls. (A) The frequency of follicles consisting of areas of CD20+ B cells surrounded by CD3+ T cells, the frequency of AID+ follicles, and Ki67+ follicles in the synovial samples from patients with RA or OA. (B) A representative micrograph of a region of RA synovium containing a well-defined lymphoid follicle (original magnification 20×) that is positive for the expression of CD3, CD20, AID, and Ki67. Arrow indicates tingible body macrophages (TBM). (C) Staining of CD3, CD20, and AID in the only synovial sample from an OA patient that contained a follicle with T and B cell aggregation. AID+ cells were not detected in this follicle. (D) A representative region of RA synovium containing CD20+ B cells and CD3+ T cells in close proximity, but with no well-defined organization (original magnification 20×). AID+ B cells were not detected in these regions. (E) A representative thyroid section with a well-formed CD3+ CD20+ and AID+ GC-like structure from a patient with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Arrow indicates tingible body macrophages (TBM).

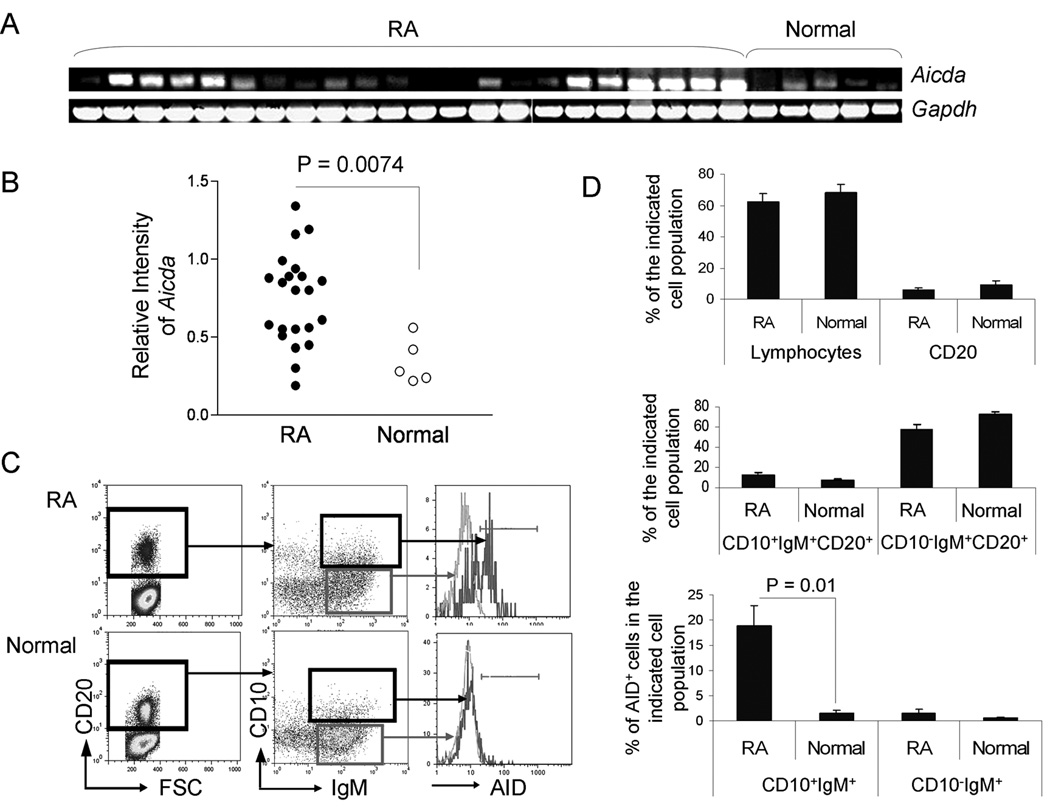

Increased expression of AID in PBMC of patients with RA

The expression of Aicda in PBMCs was determined at the RNA level by RT-PCR (Fig 2A). The intensity of AID relative to GAPDH was calculated and found to be significantly higher in the PBMCs of patients with RA compared to normal controls (Fig 2B), with approximately 55% (12 out of 22) of the patients with RA exhibiting higher levels of Aicda in the unfractionated PBMCs than normal controls. There was no significant association of Aicda expression levels with age, sex, duration of disease, treatment or disease activity as assessed by CRP levels (data not shown). However, the highest levels of Aicda were found in a patient with severe long standing RA. To analyze the phenotype of the AID-positive B cells, PBMCs from patients with RA and normal controls were surface stained with anti-CD20, anti-CD10, and anti-IgM then permeabilized and stained with anti-AID prior to FACS analysis (Fig. 2C). There was no statistical difference in the percentages of lymphocytes or CD20+ B cells (Fig. 2D top), CD10+IgM+CD20+ (newly immigrant), and CD10−IgM+CD20+ mature naïve B cells (Fig. 2D middle) between RA and normal subjects. However, the percentage of CD10+IgM+CD20+ cells that expressed AID was significantly higher in the PBMCs of patients with RA than in the normal controls (18.9 ± 4% compared to 1.6 ± 0.6%, p = 0.01) (Fig. 2D, bottom).

Figure 2. Increased AID expression in PBMCs of patients with RA.

PBMCs were obtained by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque from the peripheral blood of 22 patients with RA and 5 normal individuals. (A) Aicda expression was analyzed by RT-PCR analysis. (B) The intensity of each band was quantitated using the Image J 1.37v software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) and the intensity of the Aicda signal relative to the intensity of Gapdh signal was calculated. (C & D) The PBMCs from the RA patients and normal individuals were stained with antibodies against CD20, CD10, and IgM, then permeabilized and stained with an anti-AID antibody prior to FACS analysis. Cells were gated first on CD20+, and then on CD10+IgM+ or CD10−IgM+ cells. (C) Histograms of the FACS analysis of PBMCs from a representative AID+ RA patient and a representative normal individual are shown. (D) The average percentages of the lymphocytes, CD20+ B cells, CD10+IgM+CD20+, CD10−IgM+CD20+, as well as AID+ cells in CD10+IgM+CD20+ or CD10−IgM+CD20+ B cells in RA and normal subjects are shown (N = 22 for RA and N = 5 for normal).

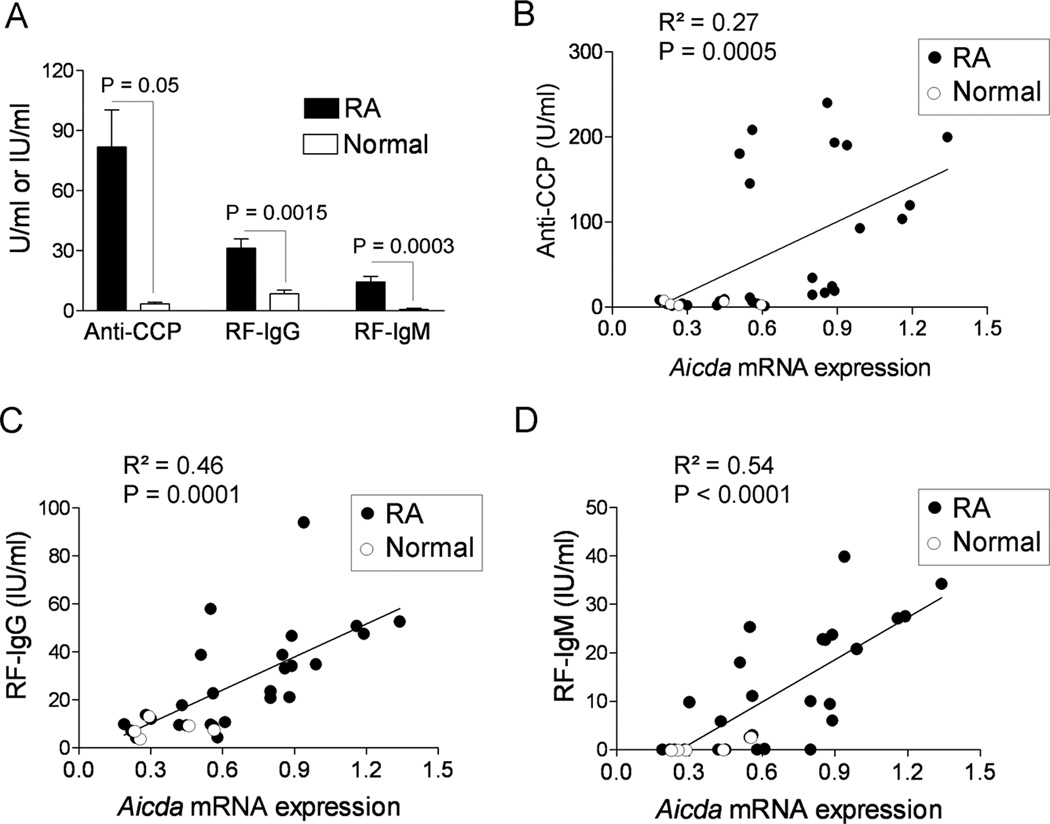

Aicda correlates with autoantibody production

The serum levels of IgG and IgM RF and autoantibodies against CCP were analyzed using commercially available ELISA kits. As would be expected, the levels of IgG and IgM RF and anti-CCP were significantly higher in the sera of patients with RA as compared with the levels in the sera of the normal individuals (Fig. 3A). There was a significant positive correlation between the levels of anti-CCP in the sera and the expression of AID in the PBMCs as determined by analysis of mRNA (p = 0.0005) (Fig. 3B). Similarly, there was a significant positive correlation between the levels of IgG (p = 0.0001) and IgM RF (p < 0.0001) in the sera and the levels of AID mRNA in the PBMCs (Fig. 3C and 3D).

Figure 3. Correlation of Aicda with the levels of autoantibodies in the sera of patients with RA.

The levels of autoantibodies in the sera of patients with RA (N = 22) and normal individuals (N = 5) were analyzed using commercially available ELISA kits. (A) ELISA result for the expression of anti-CCP (U/ml), RF-IgM (IU/ml) and RF-IgG (IU/ml) in all 27 subjects recruited in this study. Relative Aicda mRNA expression in the PBMCs was correlated with the levels of autoantibody (B) Anti-CCP (C) RF-IgG and (D) RF-IgM in the sera of patients with RA (solid circles) and normal (open circles) individuals. The R2 and p values are shown in the figures.

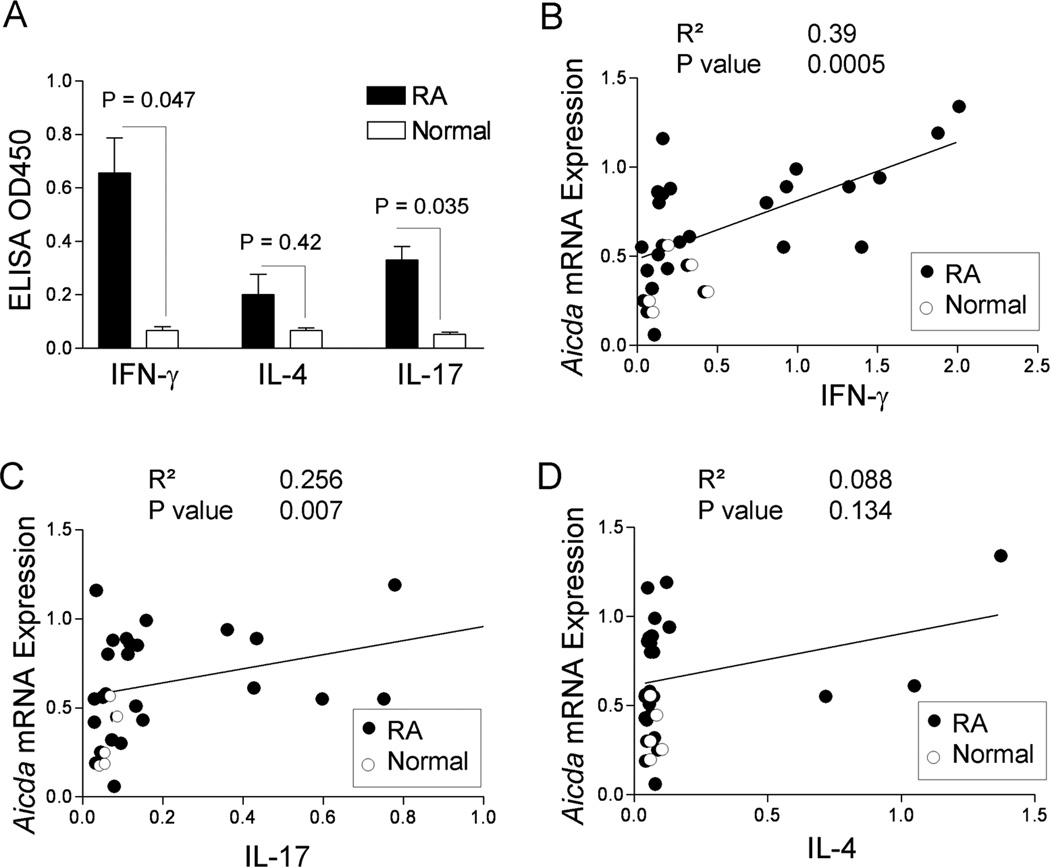

Increased Aicda correlates with sera IFN-γ and IL-17

The induction of AID in T- and B-cell interacting follicles suggested that the induction of AID in B cells requires signals from T helper cells. We therefore measured serum levels of T helper cell cytokines, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17, in RA and normal control subjects. There was a significant increase in IFN-γ and IL-17, but not IL-4 in subjects with RA compared to normal control (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the relative expression of AID mRNA was positively correlated with serum levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 4B) and IL-17 (Fig. 4C) but not with serum levels of IL-4 (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Increased Aicda is correlated with IFN-γ and IL-17.

Serum levels of cytokines were analyzed by ELISA. (A) ELISA result for the expression of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-17 in 22 patients with RA and 5 normal controls (*; p<0.05). Relative Aicda expression was correlated with sera cytokine levels (B) IFN-γ (C) IL-17 and (D) IL-4 in RA patients (solid circles) and 5 normal controls (open circles). The R2 and p values are shown in the figures.

Discussion

AID is a necessary enzyme for SHM and CSR. We have found previously that increased levels of AID are associated with the generation of autoantibodies in BXD2 mice that develop arthritis [7]. Other investigators have reported high levels of AID in a B-cell line derived from a patient with RA [21] and in follicular dendritic cells [18], but not PBMCs, from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome [19]. Here, we report that the frequency of AID+ lymphoid follicles were significantly higher in RA synovial samples than in OA synovial samples. The expression of AID in B cells in the synovia and peripheral blood of patients with RA suggests that SHM and CSR of autoantibodies can be an active ongoing process even in established disease. As we also observed high expression of AID in the PBMCs of a sub-set of patients with RA, it also is possible that the occurrence of GC-like structures and AID-positive B cells reflects the stage of disease or its activity.

In these studies, we observed AID+ and Ki67+ GCs follicles in 50% of the synovial samples tested. We also observed GC-like follicles consisting of aggregates of T and B cells in 66% (eight of 12) of RA synovial samples tested. In contrast, none of the 11 OA subjects developed AID or Ki67 positive aggregates in the synovia. A previous report by Timmer et al has shown that approximately 25% of patients with RA may have GCs in their synovia as determined by multiple synovial needle biopsies [22]. In addition, Canete et al. have detected large organized aggregates with lymphoid features in 25 of 27 patients with psoriatic arthritis [23] and Jonsson and colleagues have reported organized lymphoid aggregates that appear to be germinal center-like structures in 47 of 169 (28%) salivary glands obtained from patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome [24]. More recently, Thurlings et al. [25] reported the presence of large lymphoid structures in 31% of RA synovial samples. The higher frequency of ectopic lymphoid aggregates in autoimmune patients, compared to non-autoimmune subjects, suggests that unique local mechanisms exist to promote the aggregates to development into ectopic GCs.

It is possible that inflammatory factors such as IL-17 [8] and TNF-α [26] which have been shown to foster the formation of spontaneous GCs may lead to the upregulation of AID in autoimmune diseases in humans as well as mice. We have previously reported that pathogenic spontaneous autoimmune peanut agglutinin (PNA, one marker of germinal centers) positive GCs in the spleen of BXD2 mice exhibit close interaction of T cells with B cells [7, 8, 17]. Such GCs may develop due to IL-17 induced RGS13 and RGS16 leading to decreased migration responsiveness to chemokines, thus favoring T cell-B cell contact. IL-17 has also been reported to be higher in PBMCs of RA patients compared to more normal levels in RA synovium [27–29]. Consistent with our findings here, IL-17 levels in the serum of RA patients was significantly higher than in the control group [27]. Thus IL-17 induced GCs may be equally or more prominent in other lymphoid organs of RA patients and not confined to the synovium. The significant positive correlation between the expression of AID and serum titers of anti-CCP and RF suggests that AID expression in PBMCs of patients with RA may be a more reliable indicator of a potential spontaneous autoimmune GC that is engaged in production of autoantibodies.

The question as to whether high AID in B cells of synovial GCs or else where is associated with autoantibodies that play a role in RA is not known. Previous reports of oligoclonal expansion of B cells in RA synovium suggest local antigen presentation with autoantibody production may occur [30, 31]. Cantaert et al also observed oligoclonal expansion in some RA synovium but concluded that this was due to oligoclonal expansion of infiltrating B cells and not do to local clonal development [32]. Our finding of AID in the Ki67+ GCs of RA synovium, but not OA synovium, suggest that SHM and CSR of Ig might occur. It is still unclear if antibody diversification does occur in the synovium of RA subjects, and if so if this is a major or lesser source for autoantibody production. In addition to the increased expression of AID in ectopic GC-like follicles, we found that AID expression was significantly higher in the PBMCs of patients with RA as compared to normal controls, and that its expression occurred mainly in the CD10+IgM+ newly immigrant CD20+ B cells. The association of Aicda with anti-CCP and both IgM and IgG RF, also suggests that increased expression of Aicda may play an important role in the pathogenesis of RA. Interestingly, the highest levels of Aicda were not observed in younger patients or patients with newer onset of disease. In contrast the highest level of Aicda was found in a patient with severe long standing RA. Larger studies will be required to verify if increased AID is associated with chronic longstanding disease.

In conclusion, our results suggest that upregulation of AID in B cells may be associated with the development of arthritis-related autoantibodies in human RA patients. Inhibition of AID through therapeutic targeting may lower production of these autoantibodies, and thus reduce disease severity or progression. Most recently, we have found that an AID-dominant-negative transgenic BXD2 mouse exhibited a lower incidence and severity of spontaneous erosive arthritis (Hsu et al., unpublished observation) with dramatically lower serum levels of autoantibodies and circulating immune complexes. Tetrahydrouridine [33] which exhibits a strong binding with the cytidine deaminase domain of AID has been identified as a potent inhibitor of AID. We propose that inhibitors of AID, such as tetrahydrouridine, may be effective therapies for a substantial sub-set of patients with RA arthritis and other autoimmune diseases in which spontaneous formation of GCs promotes increased SHM and CSR.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. John M. Cuckler and Mr. Danny Tunmire for supplying synovial tissue samples. The authors acknowledge Ms. Enid Keyser, and Mr. Marion L. Spell of the FACS Core Facility, and Mr. We also acknowledge Ms. Carol Humber and Ms. Evelyn Rogers for excellent secretarial assistance. This work is supported by a Birmingham VAMC Merit Review Grant, an ACR-Within-Our Reach grant, an Alliance for Lupus Research – Target Identification in Lupus grant, an NIH RO1 grant (1AI 071110-01A1), and a research grant from Daiichi-Sankyo Co. Ltd (Dr. Mountz). Dr. Xu is a recipient of an Arthritis Foundation Fellowship Award. Dr. Hsu is a recipient of an Arthritis Foundation Investigator Award. Flow cytometry and confocal imaging were carried out at the UAB Comprehensive Flow Cytometry Core (P30 AR048311 and P30 AI027767).

References

- 1.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muramatsu M, Sankaranand VS, Anant S, Sugai M, Kinoshita K, Davidson NO, et al. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muto T, Muramatsu M, Taniwaki M, Kinoshita K, Honjo T. Isolation, tissue distribution, and chromosomal localization of the human activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) gene. Genomics. 2000;68:85–88. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nacionales DC, Weinstein JS, Yan XJ, Albesiano E, Lee PY, Kelly-Scumpia KM, et al. B cell proliferation, somatic hypermutation, class switch recombination, and autoantibody production in ectopic lymphoid tissue in murine lupus. J Immunol. 2009;182:4226–4236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mountz JD, Yang P, Wu Q, Zhou J, Tousson A, Fitzgerald A, et al. Genetic segregation of spontaneous erosive arthritis and generalized autoimmune disease in the BXD2 recombinant inbred strain of mice. Scand J Immunol. 2005;61:128–138. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2005.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, Liu J, Feng X, Yang P, Xu X, Hsu HC, et al. Synovial fibroblasts promote osteoclast formation by RANKL in a novel model of spontaneous erosive arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3257–3268. doi: 10.1002/art.21354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu HC, Wu Y, Yang P, Wu Q, Job G, Chen J, et al. Overexpression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B cells is associated with production of highly pathogenic autoantibodies. J Immunol. 2007;178:5357–5365. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu HC, Yang P, Wang J, Wu Q, Myers R, Chen J, et al. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:166–175. doi: 10.1038/ni1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. The role of T-cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:29–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vossenaar ER, van Venrooij WJ. Citrullinated proteins: sparks that may ignite the fire in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:107–111. doi: 10.1186/ar1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vossenaar ER, Nijenhuis S, Helsen MM, van der Heijden A, Senshu T, van den Berg WB, et al. Citrullination of synovial proteins in murine models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2489–2500. doi: 10.1002/art.11229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mewar D, Wilson AG. Autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Venrooij WJ, Zendman AJ, Pruijn GJ. Autoantibodies to citrullinated antigens in (early) rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;6:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benucci M, Turchini S, Parrochi P, Boccaccini P, Manetti R, Cammelli E, et al. Correlation between different clinical activity and anti CC-P (anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies) titres in rheumatoid arthritis treated with three different tumor necrosis factors TNF-alpha blockers. Recenti Prog Med. 2006;97:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Dell' Acqua D, de Portu S, Cecchini G, Cruini C, et al. Adalimumab clinical efficacy is associated with rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody titer reduction: a one-year prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R3. doi: 10.1186/ar1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hitchon CA, Alex P, Erdile LB, Frank MB, Dozmorov I, Tang Y, et al. A distinct multicytokine profile is associated with anti-cyclical citrullinated peptide antibodies in patients with early untreated inflammatory arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2336–2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu HC, Zhou T, Kim H, Barnes S, Yang P, Wu Q, et al. Production of a novel class of polyreactive pathogenic autoantibodies in BXD2 mice causes glomerulonephritis and arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:343–355. doi: 10.1002/art.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bombardieri M, Barone F, Humby F, Kelly S, McGurk M, Morgan P, et al. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase expression in follicular dendritic cell networks and interfollicular large B cells supports functionality of ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in autoimmune sialoadenitis and MALT lymphoma in Sjogren's syndrome. J Immunol. 2007;179:4929–4938. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen A, Gosemann M, Pruss A, Reiter K, Ruzickova S, Lipsky PE, et al. Abnormalities in peripheral B cell memory of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1897–1908. doi: 10.1002/art.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gil Y, Levy-Nabot S, Steinitz M, Laskov R. Somatic mutations and activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) expression in established rheumatoid factor-producing lymphoblastoid cell line. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:494–505. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Timmer TC, Baltus B, Vondenhoff M, Huizinga TW, Tak PP, Verweij CL, et al. Inflammation and ectopic lymphoid structures in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissues dissected by genomics technology: identification of the interleukin-7 signaling pathway in tissues with lymphoid neogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2492–2502. doi: 10.1002/art.22748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canete JD, Santiago B, Cantaert T, Sanmarti R, Palacin A, Celis R, et al. Ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:720–726. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsson MV, Skarstein K, Jonsson R, Brun JG. Serological implications of germinal center-like structures in primary Sjogren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2044–2049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thurlings RM, Wijbrandts CA, Mebius RE, Cantaert T, Dinant HJ, van der Pouw-Kraan TC, et al. Synovial lymphoid neogenesis does not define a specific clinical rheumatoid arthritis phenotype. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1582–1589. doi: 10.1002/art.23505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anolik JH, Ravikumar R, Barnard J, Owen T, Almudevar A, Milner EC, et al. Cutting edge: anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in rheumatoid arthritis inhibits memory B lymphocytes via effects on lymphoid germinal centers and follicular dendritic cell networks. J Immunol. 2008;180:688–692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohno M, Tsutsumi A, Matsui H, Sugihara M, Suzuki T, Mamura M, et al. Interleukin-17 gene expression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s10165-007-0015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamp LK, Easson A, Lehnigk U, Highton J, Hessian PA. Different T cell subsets in the nodule and synovial membrane: Absence of interleukin-17A in rheumatoid nodules. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1601–1608. doi: 10.1002/art.23455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada H, Nakashima Y, Okazaki K, Mawatari T, Fukushi JI, Kaibara N, et al. Th1 but not Th17 cells predominate in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SK, Bridges SL, Jr, Kirkham PM, Koopman WJ, Schroeder HW., Jr Evidence of antigen receptor-influenced oligoclonal B lymphocyte expansion in the synovium of a patient with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:361–370. doi: 10.1172/JCI116968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voswinkel J, Weisgerber K, Pfreundschuh M, Gause A. The B lymphocyte in rheumatoid arthritis: recirculation of B lymphocytes between different joints and blood. Autoimmunity. 1999;31:25–34. doi: 10.3109/08916939908993856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cantaert T, Kolln J, Timmer T, van der Pouw Kraan TC, Vandooren B, Thurlings RM, et al. B lymphocyte autoimmunity in rheumatoid synovitis is independent of ectopic lymphoid neogenesis. J Immunol. 2008;181:785–794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teh AH, Kimura M, Yamamoto M, Tanaka N, Yamaguchi I, Kumasaka T. The 1.48 A resolution crystal structure of the homotetrameric cytidine deaminase from mouse. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7825–7833. doi: 10.1021/bi060345f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]