Abstract

DNA sequencing studies have established that many cancers contain tens of thousands of clonal mutations throughout their genomes, a fact which is difficult to reconcile with the very low rate of mutation in normal human cells. This observation provides strong evidence for the mutator phenotype hypothesis, which proposes that an elevation in the spontaneous mutation rate is an early step in carcinogenesis. An elevated mutation rate implies that cancers undergo continuous evolution and harbor multiple sub-populations of cells differing from one another in DNA sequence. The extensive heterogeneity in DNA sequence and continual tumor evolution that would occur in the context of a mutator phenotype have important implications for cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: mutator phenotype, cancer genomics, DNA sequencing, mutagenesis, tumor heterogeneity

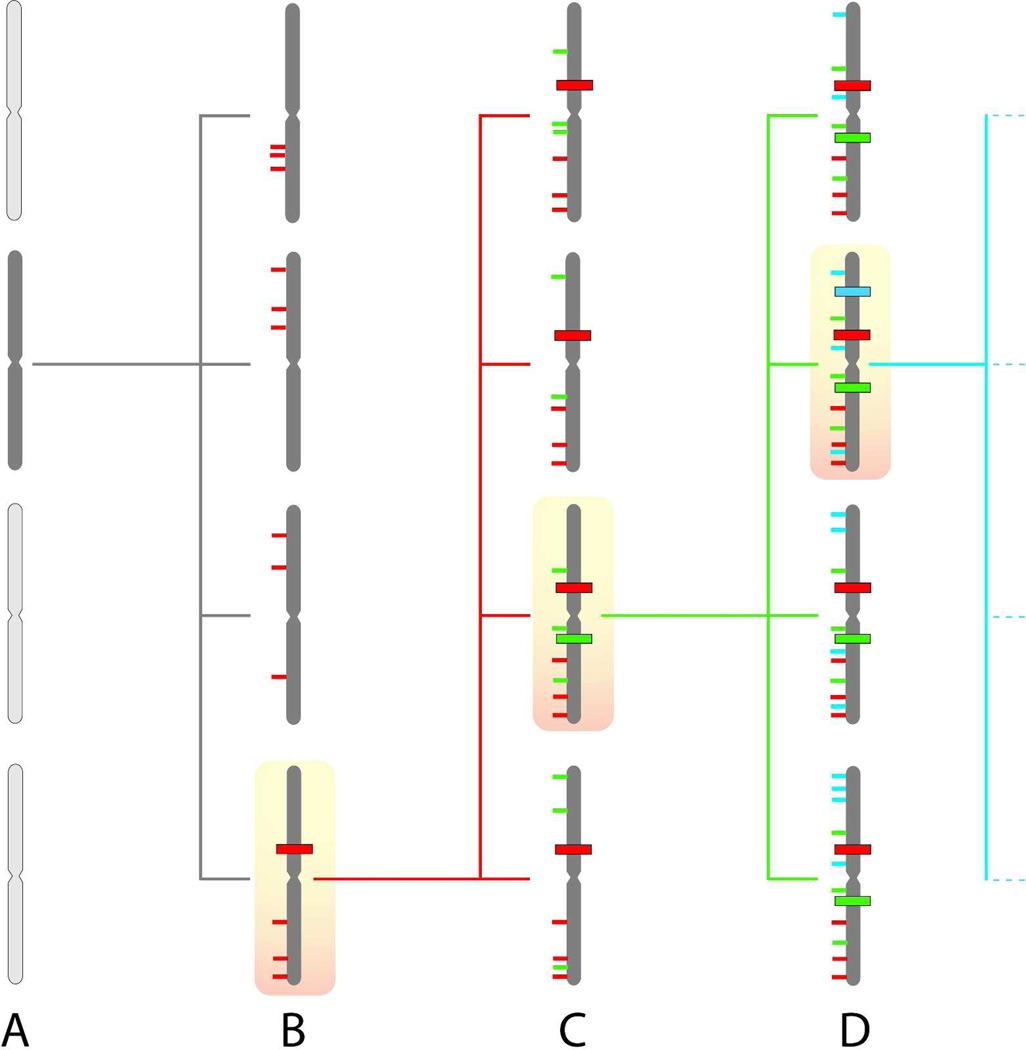

The evolution of a normal cell into a cancerous cell, with the capacity for sustained autonomous replication, implicates mutations in multiple genetic pathways that normally regulate growth.1 The multiple mutations that are required for a cell to gain the capability for uncontrolled replication are in apparent contrast to the high accuracy of DNA replication, which has been estimated to generate fewer than one mutation per 10 billion nucleotides replicated per cell division.2 Due to this discrepancy between the many mutations required for cancer and the extremely low rate at which mutations accumulate in normal human cells, we have long postulated that an early step in cancer evolution is an elevation in the spontaneous mutation rate, a concept known as the mutator phenotype hypothesis.3 We have postulated that random DNA damaging events result in mutations in genes involved in maintaining genetic stability, leading to a cascading increase of random mutations throughout tumor evolution and progression.4 Figure 1 emphasizes the genetic diversity that would arise as a consequence of a mutator phenotype. The mutator phenotype hypothesis predicts that cancer development is essentially a random process driven by an elevated rate of accumulation of mutations throughout the genome. When proposed, this concept was in contrast to the prevailing idea that cancers have only a few recurrent mutations in key genes that would provide a limited number of targets for chemotherapy. It is now well established by DNA sequencing that most human cancers contain many thousands of mutations throughout their genomes.5 There is no single mutation that is invariably present in any specific type of cancer, nor is there a common consensus of mutations. Furthermore, prevailing approaches to DNA sequencing can detect only clonal mutations, that is, mutations that are present in a substantial fraction of the many millions of cells that comprise a clinically relevant human cancer. It is likely that far more mutations present in cancers are random and are present in only one or a few cells within a tumor. The total burden of clonal and random mutations in a tumor represents an enormous extent of genetic diversity, and it is conceivable that many tumors contain such a high mutational load that pre-existing tumor sub-clones are present which are resistant to targeted chemotherapeutics. In consideration of a mutator phenotype in human cancer, we will first consider evidence from model systems that provide rationale for the concept. We will next examine data from human tumors that supply evidence for a mutator phenotype and will consider the apparent contrast between these data and the failure of sequencing studies to identify mutator mutations in human cancer. Finally, we will discuss practical implications of a mutator phenotype in cancer.

Figure 1. Continual mutagenesis results in sub-clonal genetic diversity.

(A) A single cell (dark shading) acquires a mutator phenotype.

(B) The mutator cell generates a series of progeny cells, each of which will possess a distinct set of random mutations (thin red lines). By chance, one of these mutations occurs in a gene that regulates growth (heavy red line), resulting in selective expansion of the cell containing this driver mutation.

(C) The driver mutation, as well as all the random passenger mutations from the first round of mutagenesis, will be clonally present in the progeny cells. Ongoing mutagenesis generates an additional series of random mutations in each cell (thin green lines). Another driver mutation occurs (heavy green line), which will again result in selective expansion of a cell clone.

(D) Ongoing rounds of random mutagenesis and selective expansion continue until sufficient driver mutations are present to result in uncontrolled growth and a clinically significant cancer. The driver and passenger mutations from the final clonal expansion will be present in the majority of the cells in the tumor. The mutant cells from earlier rounds of selection persist as sub-clonal populations, resulting in an enormous pool of genetic diversity within the tumor.

Highly accurate DNA replication is critical for faithful transmission of the genome, however occasional replication errors are also essential for generation of genetic diversity to allow for organisms to adapt to a changing environment. The importance of DNA replication fidelity in cellular fitness has been examined in serial passage experiments performed in E. coli.6 When mutator bacteria are co-cultured with wild-type strains, the mutator strains are better able to evolve for optimal fitness, and soon take over the population. Similarly, mutator variants are seen to arise spontaneously in nature in response to stress.7 Likewise, when a key DNA polymerase in E. coli is randomly mutated to engineer a series of strains which encompass a broad range of mutation rates, cells expressing mutator alleles out-compete the wild-type cells.8 Overall, these experiments establish that an elevated mutation rate facilitates accelerated adaptation and a competitive growth advantage. Cancer cells must overcome multiple mechanisms that normally regulate growth1 and are continually evolving as manifested by the capability to invade and metastasize. This continual refinement of fitness is analogous to that required in competition experiments in E. coli, and suggests that mutator cells would more rapidly overcome limitations to growth than would cells that replicate their DNA with normal accuracy.

The concept of mutator cells possessing a competitive advantage has been further probed by Beckman, who formulated a mathematical model to compare the probability of cancer arising with or without a mutator mutation.9 Assuming that the most efficient mechanisms of generating cancer predominates, and that enhanced mutagenesis may coexist with continuous selection and variable fitness changes, Beckman determined that mutator pathways are far more likely for most parameter values. Key parameters favoring mutator pathways include a larger number of mutations required to produce a cancer, and earlier onset of a cancer. Importantly, these conclusions are independent of absolute baseline mutation rates.

As rapidly mutating cells are predicted to possess a competitive advantage over normal cells, it would be expected that alterations which elevate the basal mutation rate will result in enhanced tumorigenesis. Indeed, many inherited human diseases with mutations that inactivate DNA repair exhibit an increase in the incidence of multiple types of cancer10 and inactivation of DNA repair in mice is likewise frequently associated with a cancer phenotype.11 Specific support for this concept comes from expression in mice of mutated DNA polymerases which replicate DNA with altered accuracy in comparison with the wild-type allele.12,13,14

Recent evidence from study of human cancers provides strong and complementary support for the concept of a mutator phenotype. First, we have established a method to detect and identify random, non-clonal mutations in human cells.15 In normal human tissues the frequency of random mutations is <1 × 10−8. However in the six tumors analyzed, a mean of 210 × 10−8 mutations per base-pair was detected, more than 200-fold greater than paired adjacent normal tissues16. DNA sequencing indicated that most are single base substitutions. This large increase in random, non-clonal mutations suggests that cancer cells replicate their DNA with greatly impaired accuracy relative to normal cells. In addition, exons or entire genomes of human tumors have recently been sequenced.17 The cancer sequence is punctuated with large numbers of single base substitutions that are not present in normal DNA from the same individual. In solid tumors, there are frequently 1000 or more detected mutations in exons, with tens of thousands of total mutations per genome. Moreover, these studies score predominantly for clonal mutations and consequently underestimate the true mutational load of each tumor. The tens of thousands of clonal mutations in tumors, which are likely to be accompanied by far more non-clonal mutations, are difficult to reconcile with the extremely high accuracy of DNA replication. This discrepancy suggests that impaired DNA replication fidelity may be a common feature of tumors.

The emergence of resistance to chemotherapy is a prominent feature of cancer. It is becoming increasingly clear that chemotherapeutic-resistant mutant cells pre-exist in a tumor as a sub-clonal population at the time of diagnosis, and that these mutant cells expand in response to the selective pressure of cancer therapy.18,19 The pre-existence of chemotherapy-resistant sub-clones further supports the concept that tumors encompass extensive genetic diversity far beyond that which can be detected by sequencing studies that primarily catalog clonal alterations.

The enormous burden of both clonal and sub-clonal mutations in human tumors is consistent with an elevated mutation rate as a common feature of cancer. However, DNA sequencing of human tumors has not revealed a substantial number of mutations in genes that normally maintain genetic stability.17 How can this disparity be reconciled? First, while the acquisition of mutations within genes that govern the fidelity of DNA replication and repair would result in an easily detected mutator phenotype, impaired DNA replication accuracy can be attained through other mechanisms. The efficacy and extent of DNA repair can be altered through mechanisms such as DNA methylation, altered chromatin structure, mutation in noncoding regulatory regions, and altered activity of regulatory proteins. Indeed, in multiple types of cancers, altered expression of error-prone trans-lesion polymerases occurs, and this altered expression may contribute to impaired replication of damaged DNA and mutagenesis.20,21 There is also emerging evidence for altered nucleotide pool sizes as a potential source of a mutator phenotype: in E. coli, efficient synthesis across replication-blocking DNA lesions requires elevated concentrations of nucleotides, and elevated nucleotide pools result in an increase in spontaneous mutagenesis in vivo.22 Likewise, in S. cerevisiae, genotoxic stress leads to dNTP pool expansion and an increase in spontaneous mutagenesis.23

In considering the absence of mutator mutations in human cancers, it is also important to note that DNA sequencing of human tumors is best able to detect somatic point mutations. Insertion and deletion events within genes are far more difficult to identify and cataloging this class of mutation requires sequencing to great depth.24 Importantly, insertion or deletion of nucleotides within genes would be more likely to alter protein function than would point mutations, as the majority of point mutations may not result in altered protein function, whereas insertion or deletion of nucleotides within a gene will nearly always be deleterious.25

An alternative explanation for the discrepancy between the many mutations in cancer and the general lack of mutator mutations being seen in sequencing studies is that a mutator phenotype may be an early event in carcinogenesis that is subsequently selected against. In competition experiments performed in bacteria, mutator variants initially out-compete the wild-type variants due to their greater capacity to evolve optimal fitness for their environment. However following extended passage for ~1,000 generations, the mutator variants acquire multiple deleterious substitutions and gradually lose fitness, resulting in a shift in equilibrium back toward bacterial strains with wild-type mutation rates.26 We propose that a similar process occurs in human cancers, such that an early event in carcinogenesis is acquisition of a mutator phenotype, followed by generation of genetic diversity and sequential rounds of selection for cell clones that possess mutations in genes that normally regulate cell growth. As a cancerous clone expands and becomes a clinically significant tumor consisting of 1 × 109 or more cells, it is likely that sustained mutagenesis becomes deleterious, such that a mutator phenotype is then selected against and the mutator mutation is lost (for example, by gene conversion of the mutant allele back to the wild-type allele27 or by secondary somatic mutation28).

If a mutator mutation is indeed an early event in carcinogenesis with subsequent loss of the mutator mutation due to negative selection in a dominant clone that expands to form the final tumor, a sub-clonal mutator population may remain, which has reduced fitness relative to the dominant clone. As conventional DNA sequencing can detect only dominant clones, these sub-clonal mutator populations—which would be rare—could be detected only if tumor DNA is sequenced to exceptional depth. Such an approach has been limited by the high error rate of next-generation DNA sequencing, which has been reported to range between 0.1 – 1%.29 A search for sub-clonal mutator mutants will thus require the development of DNA sequencing methods with greatly increased accuracy.

The mutator phenotype model predicts that cancers have a large pool of sub-clonal mutants, which is a concept with considerable therapeutic importance. Indeed, pre-existing mutants that confer resistance to targeted chemotherapeutic agents have been found to be present prior to the initiation of therapy.18,19 The mutator phenotype hypothesis predicts that any single-agent cancer therapy will frequently fail because pre-existing mutant sub-clones are likely to exist, and combined treatment with a number of effective agents is likely to be required for effective control of cancer. However, if the mutator phenotype is indeed a common feature of human cancer, it may be possible to selectively target cancer cells through their elevated mutational burden. Experiments in model systems have established that an upper bound of genomic mutational burden exists.30 This upper bound has been exploited as a therapeutic target through an approach known as lethal mutagenesis: HIV is an organism known to have a high mutation rate,31 and while this trait is beneficial in that the virus is able to rapidly evolve, further elevation of mutagenesis of HIV by treatment with mutagenic nucleoside analogs results in loss of fitness and extinction of HIV infection in cell culture.32 Rationale for the same concept of lethal mutagenesis has been demonstrated in cancer cells. Inherited mutation in the BRCA1/2 genes results in defective DNA repair, and further inhibition of DNA repair pathways with poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors results in selective extinction of cancer cells.33

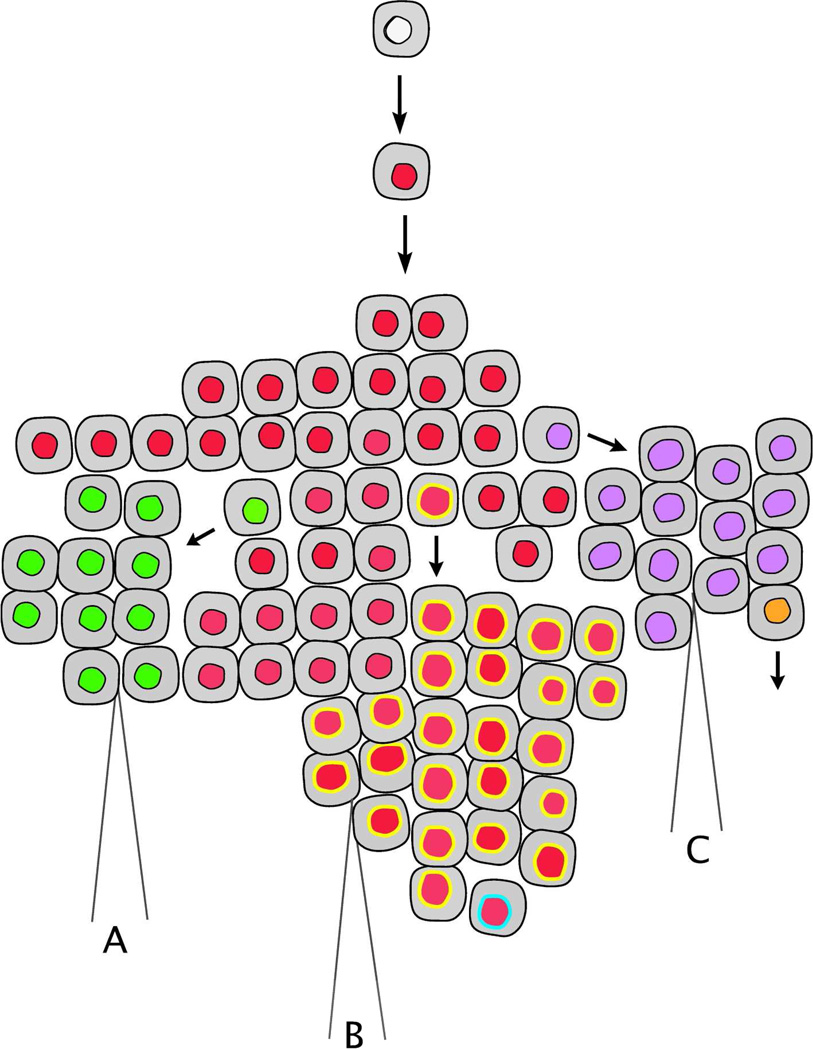

The mutator phenotype hypothesis predicts that tumors harbor a large number of sub-clones, and thus DNA sequencing efforts that result in generation of a single DNA sequence from a heterogeneous population of millions of cells will not be representative of the overall genetic complexity of a tumor (figure 2). Sequencing tumor DNA to great depth and at high accuracy would give a better view of an individual tumor as a constantly evolving population of cells. Indeed, in studies that have sequenced DNA from both a primary tumor and a metastasis, there are mutations in the primary tumor which are not seen in the metastasis, suggesting that metastatic cells arise from tumor sub-clones.34,35 Greater depth of sequencing may allow for early detection of pre-existing clones in a primary tumor suggestive that micro-metastases already are present in the patient, a finding that would have important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Moreover early detection of drug-resistant sub-clones would allow for the choice of chemotherapy to be better targeted to allow for a longer period of response before drug resistance inevitably arises. Ultimately, when cancer is viewed as a heterogeneous population of cells undergoing continual evolution in response to shifting selective pressures in the environment, targeted cancer therapy based upon sequencing of a patient’s tumor may require sequencing of multiple biopsies, with serial re-sequencing to identify the emergence of new dominant clones with differing patterns of chemotherapy sensitivity. Toward this end, new methods are being developed to sequence DNA from human tumors with increased accuracy and to significant depth. These methods will allow us to gain a better understanding of genetic heterogeneity within human tumors, and to identify the contribution of a mutator phenotype to tumorigenesis and malignant progression.

Figure 2. Spatial heterogeneity in cancer.

Following clonal expansion of a cell that has acquired multiple driver mutations (red nucleus), mutagenesis persists resulting in accumulation of additional mutations and ongoing generation of sub-clonal populations within the tumor. Distinct sub-clones are depicted as cells with altered nuclei coloring. Spatial heterogeneity is an inherent property of a continually evolving tumor, and three biopsies of this same tumor (labeled as A, B, and C) will result in identification of three distinct DNA sequences. This topography indicates that multiple biopsies may be required to accurately assess the resistance of tumors to chemotherapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. The fidelity of DNA synthesis by eukaryotic replicative and translesion synthesis polymerases. Cell Res. 2008;18:148–161. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeb LA, Springgate CF, Battula N. Errors in DNA replication as a basis of malignant changes. Cancer Res. 1974;34:2311–2321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salk JJ, Fox EJ, Loeb LA. Mutational Heterogeneity in Human Cancers: Origin and Consequences. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010;5:51–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox EJ, Salk JJ, Loeb LA. Cancer Genome Sequencing--An Interim Analysis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4948–4950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1231. (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson TC, Scheppe ML, Cox EC. Fitness of an Escherichia coli mutator gene. Science. 1970;169:686–688. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3946.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SM. Evolving responsively: adaptive mutation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:504–515. doi: 10.1038/35080556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loh E, Salk JJ, Loeb LA. Optimization of DNA polymerase mutation rates during bacterial evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:1154–1159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912451107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckman RA, Loeb LA. Efficiency of carcinogenesis with and without a mutator mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:14140–14145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606271103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preston BD, Albertson TM, Herr AJ. DNA replication fidelity and cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2010;20:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedberg EC, Meira LB. Database of mouse strains carrying targeted mutations in genes affecting biological responses to DNA damage Version 7. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:189–209. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albertson TM, Ogawa M, Bugni JM, Hays LE, Chen Y, Wang Y, et al. DNA polymerase epsilon and delta proofreading suppress discrete mutator and cancer phenotypes in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:17101–17104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907147106. (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkatesan RN, Treuting PM, Fuller ED, Goldsby RE, Norwood TH, Gooley TA, et al. Mutation at the polymerase active site of mouse DNA polymerase delta increases genomic instability and accelerates tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:7669–7682. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00002-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitt MW, Venkatesan RN, Pillaire MJ, Hoffmann JS, Sidorova JM, Loeb LA. Active site mutations in mammalian DNA polymerase delta alter accuracy and replication fork progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:32264–32272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bielas JH, Loeb LA. Quantification of random genomic mutations. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nmeth751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bielas JH, Loeb KR, Rubin BP, True LD, Loeb LA. Human cancers express a mutator phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:18238–18242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607057103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loeb LA. Human cancers express mutator phenotypes: origin, consequences and targeting. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:1–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molinari F, Felicioni L, Buscarino M, De Dosso S, Buttitta F, Malatesta S, et al. Increased detection sensitivity for KRAS mutations enhances the prediction of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:4901–4914. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roche-Lestienne C, Lai JL, Darre S, Facon T, Preudhomme C. Several types of mutations of the Abl gene can be found in chronic myeloid leukemia patients resistant to STI571, and they can pre-exist to the onset of treatment. Blood. 2002;100:1014–1018. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pillaire MJ, Selves J, Gordien K, Gouraud PA, Gentil C, Danjoux M, et al. A “DNA replication” signature of progression and negative outcome in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2009;29:876–887. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Q, Fang Y, Xu Y, Zhang K, Hu X. Down-regulation of DNA polymerases κ, η, ι, and ζ in human lung, stomach, and colorectal cancers. Cancer Lett. 2005;217:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gon S, Napolitano R, Rocha W, Coulon S, Fuchs RP. Increase in dNTP pool size during the DNA damage response plays a key role in spontaneous and induced-mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:19311–19316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113664108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson MB, Katou Y, Keszthelyi A, Sing TL, Xia T, Ou J, et al. Endogenous DNA replication stress results in expansion of dNTP pools and a mutator phenotype. EMBO J. 2012 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.485. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, Pennil CC, Nord AS, Thornton AM, et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:18032–18037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115052108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo HH, Choe J, Loeb LA. Protein tolerance to random amino acid change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:9205–9210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403255101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funchain P, Yeung A, Stewart JL, Lin R, Slupska MM, Miller JH. The consequences of growth of a mutator strain of Escherichia coli as measured by loss of function among multiple gene targets and loss of fitness. Genetics. 2000;154:959–970. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.3.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen CL, Wiuf C, Kruhoffer M, Korsgaard M, Laurberg S, Orntoft TF. Frequent occurrence of uniparental disomy in colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:38–48. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norquist B, Wurz KA, Pennil CC, Garcia R, Gross J, Sakai W, et al. Secondary somatic mutations restoring BRCA1/2 predict chemotherapy resistance in hereditary ovarian carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:3008–3015. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flaherty P, Natsoulis G, Muralidharan O, Winters M, Buenrostro J, Bell J, et al. Ultrasensitive detection of rare mutations using next-generation targeted resequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:1–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herr AJ, Ogawa M, Lawrence NA, Williams LN, Eggington JM, Singh M, et al. Mutator Suppression and Escape from Replication Error–Induced Extinction in Yeast. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preston BD, Poiesz BJ, Loeb LA. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1988;242:1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.2460924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loeb LA, Essigmann JM, Kazazi F, Zhang J, Rose KD, Mullins JJ. Lethal mutagenesis of HIV with mutagenic nucleoside analogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1999;96:1492–1497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alli E, Sharma VB, Sunderesakumar P, Ford JM. Defective repair of oxidative DNA damage in triple-negative breast cancer confers sensitivity to inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3589–3596. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turajlic S, Furney SJ, Lambros MB, Mitsopoulos C, Kozarewa I, Geyer FC, et al. Whole genome sequencing of matched primary and metastatic acral melanomas. Genome Res. 2011 doi: 10.1101/gr.125591.111. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vermaat JS, Nijman IJ, Koudijs MJ, Gerritse FL, Scherer SJ, Mokry M, et al. Primary colorectal cancers and their subsequent hepatic metastases are genetically different: implications for selection of patients for targeted treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1965. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]