Abstract

Protein misfolding and/or aggregation has been implicated in several human diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases and familial amyloid polyneuropathy. These maladies are referred to as amyloid diseases, because they are named after the cross-β-sheet amyloid fibril aggregates or deposits common to these diseases. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), the principal polyphenol present in green tea, has been shown to be effective at preventing aggregation and is able to remodel amyloid fibrils comprising different amyloidogenic proteins, although the mechanistic underpinnings are unclear. Herein, we work towards an understanding of the molecular mechanism(s) by which EGCG remodels mature amyloid fibrils made up of Aβ1–40, IAPP8–24, or Sup35NM7–16. We show that EGCG amyloid remodeling activity in vitro is dependent on auto-oxidation of the EGCG. Oxidized and unoxidized EGCG binds to amyloid fibrils, preventing the binding of thioflavin T. This engagement of the hydrophobic binding sites in Aβ1–40, IAPP8–24, or Sup35NM7–16 amyloid fibrils seems to be sufficient to explain the majority of the amyloid remodeling observed by EGCG treatment, although how EGCG oxidation drives remodeling remains unclear. Oxidized EGCG molecules react with free amines within the amyloid fibril through the formation of Schiff bases, cross-linking the fibrils, which may prevent dissociation and toxicity, but these aberrant post-translational modifications do not appear to be the major driving force for amyloid remodeling by EGCG treatment. These insights into the molecular mechanism of action of EGCG provide boundary conditions for exploring amyloid remodeling in more detail.

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular and/or intracellular protein aggregation affords a spectrum of aggregate structures, including cross-β-sheet-rich amyloid fibril deposits that are characteristic of approximately 25 amyloid diseases1. Only in the case of the transthyretin and light chain amyloidoses are there regulatory agency approved drugs to combat these diseases2,3. The screening of a library of over 5,000 natural compounds identified epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG; Figure 1A) as an inhibitor of mutant huntingtin exon 1 aggregation and toxicity4. EGCG directly binds to intrinsically disordered Aβ and α-synuclein, promoting their assembly into large, non-toxic, spherical oligomers5. EGCG can also remodel mature amyloid fibrils, reducing their thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence and converting them to amorphous protein aggregates that are less toxic to cells6. Even though the molecular mechanism(s) of action of EGCG has yet to be elucidated, four clinical trials are currently underway to determine the benefits of EGCG employing Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and light chain amyloidosis patients (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov). Herein, we describe our efforts to work towards elucidating the molecular mechanism(s) by which EGCG remodels amyloid fibrils. The data outlined herein and from the previous work of Raleigh et al. seem to demonstrate that hydrophobic binding site engagement in the amyloid fibril by EGCG appears to be sufficient for the majority of EGCG amyloid remodeling observed, at least in the Aβ1–40, IAPP8–24, or Sup35NM7–16 amyloids studied in this work. EGCG is able to self-oxidize, affording a complex mixture of monomeric and polymeric EGCG-based quinones. However, it is still unclear whether this oxidation drives amyloid remodeling in the absence of covalent modification, which heavily crosslinks amyloid having primary amino or thiol groups proximal to the hydrophobic binding sites.

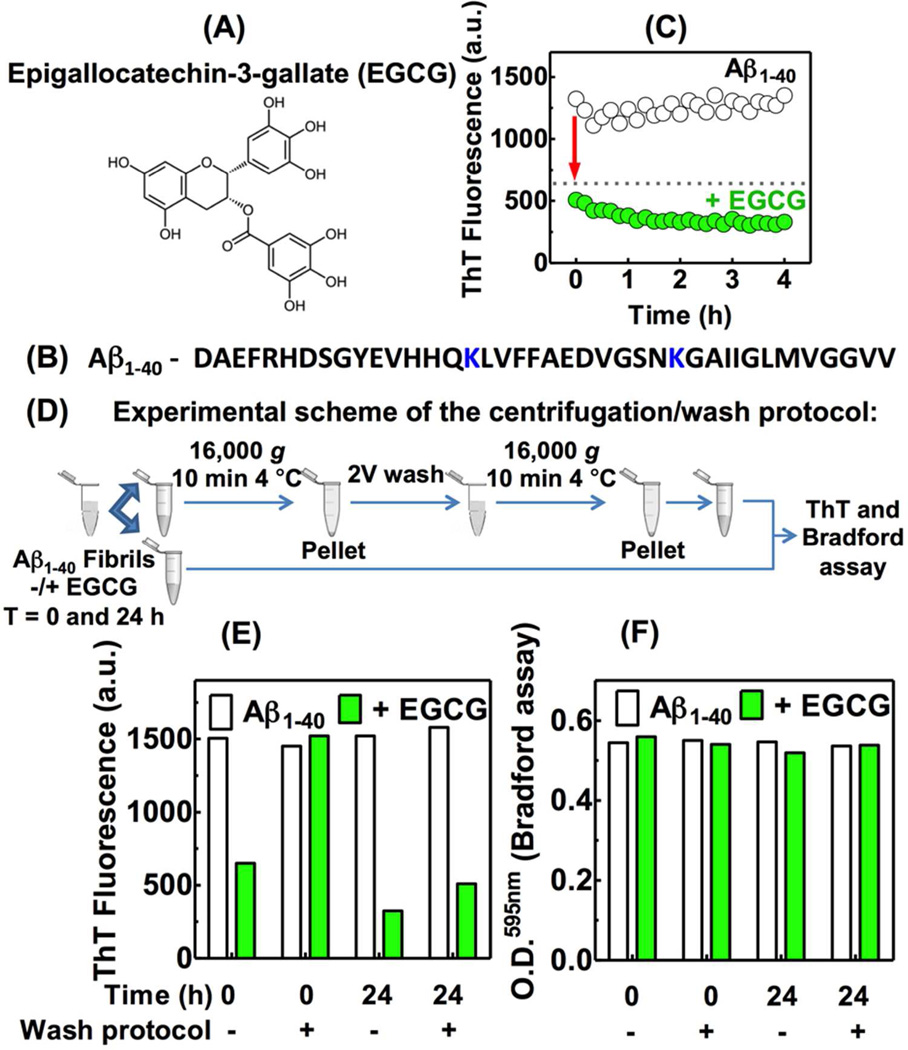

Figure 1.

Effect of EGCG on ThT fluorescence of Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils. (A) Structure of EGCG. (B) Primary sequence of Aβ1–40 peptide, lysines 16 and 28 are highlighted in blue. (C) Kinetics of Aβ1–40 amyloid fibril remodeling monitored by ThT fluorescence incubated in the absence or presence of EGCG. (D) Experimental scheme of the centrifugation/wash protocol. (E) ThT fluorescence or (F) protein quantification by the Bradford assay (O.D.) of samples incubated for 0 or 24 h in the absence or presence of EGCG. The use of the centrifugation/wash protocol is denoted by (+). The buffer used for all assays was 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl (25 °C). [Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils] = 65 µg/mL, [EGCG] = 30 µM. For ThT fluorescence, the ThT concentration used was 20 µM, Ex: 440 nm and Em: 485 nm.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Preparation of Aβ1–40 and AβAc1–40 K16R K28R fibrils

Aβ1–40 and AβAc1–40 K16R K28R fibrils were prepared as previously described7. Aβ1–40 and AβAc1–40 K16R K28R were synthesized using a standard Fmoc chemistry strategy for solid phase peptide synthesis. For AβAc1–40 K16R K28R, the N terminal of the peptide was acetylated by the incubation of the uncleaved resin with 10% acetic anhydride for 30 min at RT. The resulting peptides were purified by reversed phase C18 high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. After 6 d aggregation at 37 °C in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 0.02% NaN3 with agitation (rotation at 24 rpm), the fibrils were centrifuged (16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C), the supernatant was removed and the pellet was stored at −20 °C until used. An aliquot of the fibrillar pellet was resuspended in 8M urea, sonicated for 1 h and the protein concentration was determined using a Pierce BCA assay. All experiments were performed with at least three different Aβ1–40 amyloid fibril preparations.

Preparation of IAPPAc8–24, Sup35NMAc7–16 and Sup35NMAc7–16 Y→F fibrils

All peptides were synthesized with an acetylated N-terminus (Ac) by GenScript. The purity was greater than 95% as analyzed by RP-HPLC and the correct mass was confirmed by electrospray ionization. Peptide stock solutions were prepared by dissolving a weighed amount of peptide in 8M guanidine HCl, 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4 to obtain a final concentration of 20 mg/mL. The peptides were sonicated for 1 h and centrifuged (10 min at 16,000 g at 25 °C) to remove insoluble material. The concentration of the stock solutions was determined by Bradford assay. The peptide stock solutions were diluted (~80 fold) in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 0.02% NaN3 to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL. The samples were incubated with agitation (rotation at 24 rpm) at 25 °C for 6 d. The fibrils were centrifuged (16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C), the supernatant was removed and the pellet was stored at −20 °C until use.

EGCG preparation

EGCG obtained from Sigma-Aldrich was prepared in fresh ultra-pure Milli-q water and aliquots of the stock solution (5 mM) were stored at −80 °C until use. The purity was greater than 95% as analyzed by RP-HPLC and the correct mass was confirmed by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

Centrifugation/wash protocol to remove unbound EGCG

Aliquots (200 µL) of amyloidogenic peptide / amyloid samples in the absence or presence of EGCG were centrifuged (16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C) to obtain a pellet. The pellet was washed with 400 µL of 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and the solution was centrifuged again (16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl with 20 µM thioflavin T (ThT) for the ThT assay. For the filter retardation (FR) assay, the pellet was resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl with 2% SDS and boiled for 7 min. For circular dichroism (CD), the pellet was resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl. For the Bradford assay, the pellet was resuspended in 50% 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 50% Bradford solution. For the experiment described in the Figure 6, 0.3% Tween 20 + 0.05% Oleic acid were added to PBS to obtain a detergent solution.

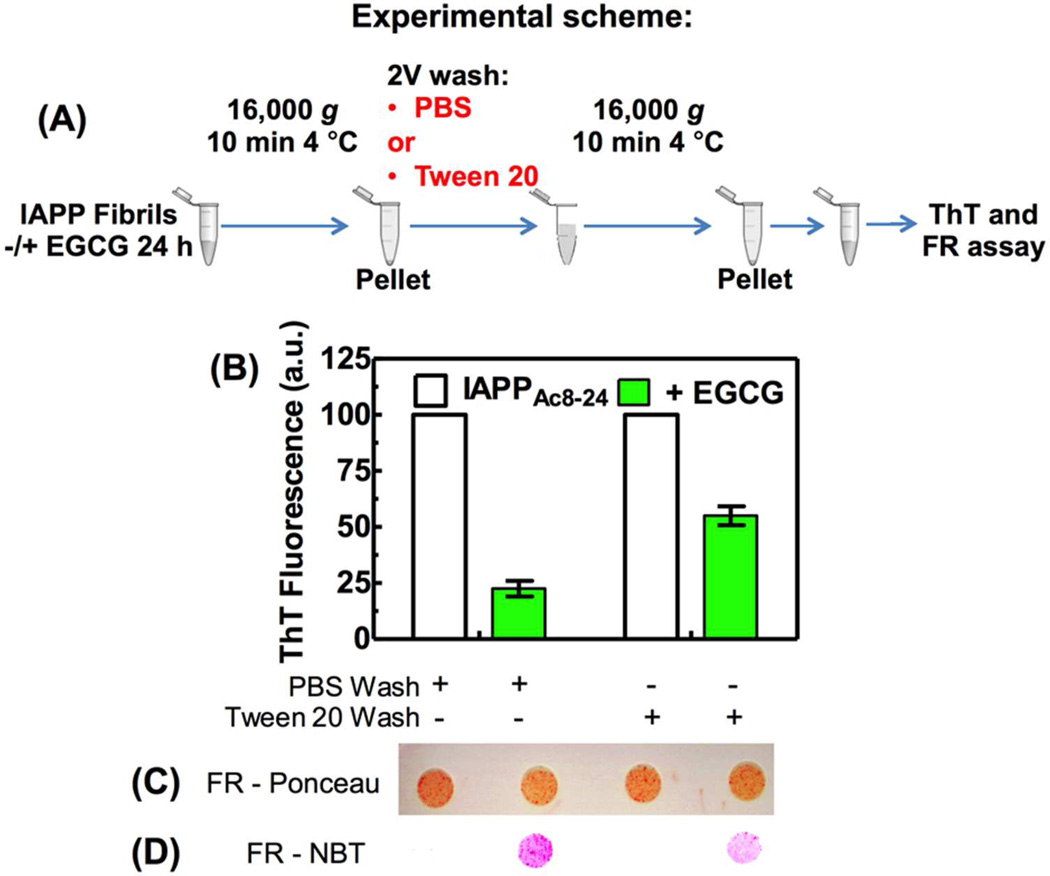

Figure 6.

The amyloid remodeling activity of EGCG is still partially functional in the presence of detergent micelles. (A) Experimental scheme of the centrifugation/wash protocol, highlighting the wash step performed with PBS or PBS containing Tween 20. IAPPAc8–24 mature amyloid fibrils (65 µg/mL) were incubated in the absence or presence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h at 25 °C. After the centrifugation/wash protocol (A), the ThT fluorescence (B) was recorded. An aliquot of these samples (without boiling) was then applied to FR membrane that was stained by Ponceau (C) or NBT (D).

Congo red assay

Samples were incubated with 10 µM Congo red for 10 min in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl. Absorbance was recorded at 540 and 477 nm using a cuvette with a 1 cm path-length and the amount of Congo red binding was determined as described previously8.

Thioflavin T (ThT) assay

For the experiment described in Figure 1C, the samples containing ThT (20 µM) were incubated at 25 °C in a 96-well plate (Costar # 3631). Every 10 min, the plates were shaken for 5 s, and fluorescence (excitation at 440 nm, emission at 485 nm) was monitored using a Spectra Gemini EM fluorescence plate reader. For the experiments using the centrifugation/wash protocol, the ThT fluorescence was recorded as a single point measurement in a 96-well plate using the excitation and emission parameters described above.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD1) experiments

SOD1 was a gift from Dr. J. A. Tainer (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) and was purified as described previously9. The activity of SOD1 was determined using the NADH oxidation protocol10. We used a 100-fold excess of SOD1 (1 µg/mL), necessary to achieve 100% of SOD1 activity. The activity of SOD1 was unaffected after 24 h incubation in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl at 25 °C, the conditions used in the experiment of the Figure 3. However, we were unable to determine the activity of SOD1 in the presence of EGCG, since this compound interferes with the NADH oxidation assay.

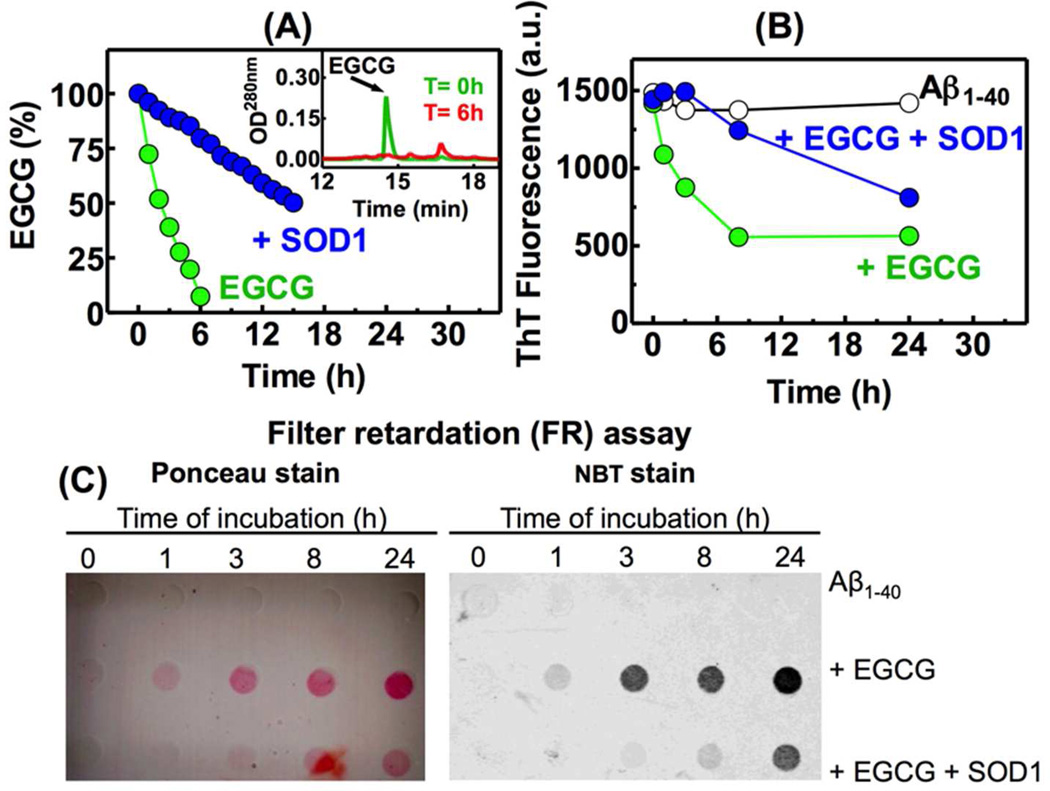

Figure 3.

EGCG amyloid remodeling activity depends on auto-oxidation. (A) The stability of EGCG is enhanced in the presence of 1 µg/mL SOD1. (Inset A) The auto-oxidation of EGCG was monitored by RP-HPLC using a C18 column. (B) A kinetics experiment monitoring the ThT fluorescence using the centrifugation/wash protocol was performed with Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils in the presence of EGCG or EGCG + SOD1. Buffer alone was used as a control. (C) Filter retardation (FR) assay of aliquots of the samples described in Figure 3B stained by Ponceau or NBT, as indicated. For detailed experimental conditions see the legend of Figure 1.

Filter retardation (FR) assay

For the filter retardation assay, samples were applied to cellulose acetate membrane using a DOT blot apparatus (Bio Rad, Bio Dot) and then stained using Ponceau or nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT). The Paz protocol was used for the NBT staining11. Briefly, the membranes were incubated in the dark at 25 °C with agitation in the NBT solution (0.25 mM NBT, 2 M glycine pH 10). After 2 h incubation, the membranes were washed with water and scanned.

Circular dichroism (CD)

Far-UV CD measurements on samples in 50 mM phosphate buffer, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 were made using an AVIV 420SF spectropolarimeter with a 2.0 mm path-length quartz cuvette. Data were averaged for three scans at a speed of 50 nm/min collected in 0.2 nm steps at 25 °C. The baseline (buffer alone) was subtracted from the corresponding spectra. Deconvolution of secondary structure was performed according to the program CDNN2.112.

Acetylation of Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils

Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils (20 µM) in 20 mM borate buffer pH 8.0 were incubated with 1 mM acetic anhydride overnight at 25 °C with agitation (rotation at 20 rpm). The acetylated fibrils were centrifuged (16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C) and washed with 2 volumes of 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl. The solution was centrifuged (16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C) and the pellet quantified as described in the section ‘Preparation of Aβ1–40 fibrils’.

Electron microscopy

Copper grids (carbon- and formvar-coated 400 mesh) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield PA) were glow discharged and inverted on a 5 µL aliquot of sample for 3 min. Excess sample was removed and the grids immediately placed briefly on a droplet of double distilled water, followed by 2 % uranyl acetate solution for 2 min. Excess stain was removed and the grid allowed to dry thoroughly. Grids were then examined on a Philips CM100 electron microscope (FEI, Hillsbrough OR) at 80 kV and images collected using a Megaview III ccd camera (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, Lakewood CO).

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

Samples were placed directly onto freshly cleaved mica for 10 min in a volume of 50 µL. Then, the samples were washed five times with 50 µL of ultra-pure water and air dried overnight. Tapping-mode AFM in air was performed using a Veeco Nanoscope III AFM. Veeco rectangular silicon cantilevers with resonance frequency of 75 kHz and nominal spring constant of 2.8 N/m were used. Samples were imaged at scan rates of 2.0 Hz, and 512 × 512 pixels were collected per image. At least three regions of each surface were investigated to confirm homogeneity of the samples.

Quantification by RP-HPLC

EGCG samples were analyzed at 25 °C by RP-HPLC using a Gemini-NX 5µ C18 column as described previously13 and quantified by UV absorption at 220 nm. Aβ1–40 samples were analyzed by RP-HPLC using a Gemini-NX 5µ C18 column in a water (0.1% NH4OH)/acetonitrile (0.1% NH4OH) gradient and quantified by UV absorption at 220 nm, as previously described14.

Seeding experiments

Amyloid fibrils were incubated in the absence or presence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h at 25 °C. The fibrils were processed using the centrifugation/wash protocol and then sonicated for 30 min in order to produce seeds. A monomeric solution of peptide (65 µg/mL) was incubated in the absence or presence of 5% seeds in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl without agitation. The samples containing ThT (20 µM) were incubated at 25 µ in a 96-well plate and every 10 min the fluorescence (excitation at 440 nm, emission at 485 nm) was monitored.

MTT Metabolic Assay

Protein aggregates were produced by incubation of acetylated or non-acetylated Aβ1–40 (50 µM) amyloid fibrils in the absence or presence of 250 µM EGCG in PBS. PBS without any protein but with or without 250 µM EGCG was used as controls. After 16 h at 25 °C, the samples were applied to HEK293 (Human Embryonic Kidney 293) cells at a 10-fold dilution. HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin in a 5% CO2 humidified environment at 37 °C. Cells were plated at a density of 10,000 cells per well on 96-well plates in 100 µL fresh medium. After 24 h, the protein aggregates were added and the cells were incubated for 2 d at 37 °C. Cytotoxicity was measured utilizing the 3–4,5 dimethylthiazol-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay kit (Promega). Absorbance values of formazan were determined at 570 nm after 1 h of cellular lysis.

Data Processing

The error bars represent the S.D. of three independent measurements.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To start investigating the molecular mechanism(s) by which EGCG remodels mature amyloid fibrils, we produced Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils using rotary agitation (24 rpm) of the Aβ1–40 peptide (15 µM; Figure 1B) for 6 d in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. The resulting amyloid fibrils were characterized by Congo red and ThT binding assays (Figure S1A), by electron microscopy (EM) (Figure S1B), and by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (Figure S1C).

The Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils (65 µg/mL) were then incubated with 2 eq. of EGCG (30 µM) relative to Aβ monomers (15 µM) and ThT fluorescence was monitored as a function of time (Figure 1C). We observed a rapid initial decrease in the fluorescence of ThT in the presence of EGCG, followed by a slower decrease over time, as reported previously by others in analogous studies6 (Figure 1C). The rapid initial decrease in ThT fluorescence suggested that EGCG might be competing with ThT for amyloid binding sites (shown previously for islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) fibrils15) or might be quenching the ThT fluorescence, rather than remodeling the amyloid fibril. To explore these possibilities, we established methodology that allows us to quantify the ThT fluorescence of Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils after performing a series of fibril centrifugations and washes to remove any soluble EGCG before each ThT measurement (Figure 1D). Using this centrifugation/wash protocol, we no longer observed the rapid initial decrease in ThT fluorescence at t=0 upon incubation with EGCG (Figure 1E; t=0 reflects fast manual mixing followed by the measurement; ≈ 10 min). Within this centrifugation/wash period we see no fibril dissociation or Aβ1–40 monomer aggregation (Figure S2A). This suggests that the initial decrease in ThT fluorescence observed in Figure 1C is due to EGCG interference with the ThT measurements. However, after 24 h of EGCG treatment, we observed a substantial decrease in the ThT fluorescence of Aβ1–40 fibrils using the centrifugation/wash protocol (Figure 1E). This decrease in ThT fluorescence after 24 h of EGCG treatment (Figure 1E) cannot be explained by EGCG-mediated solubilization of amyloid fibrils, since insoluble Aβ1–40 quantified by the Bradford assay was the same at 0 and 24 h whether or not the centrifugation/wash protocol was used (Figure 1F). We conclude that EGCG interferes with ThT binding-associated fluorescence, leading to a fast decrease in the ThT fluorescence intensity (t=0). After 24 h of treating Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils with EGCG, the Aβ1–40 remains insoluble and exhibits a low ThT binding capacity (Figure 1), strongly demonstrating that EGCG does not disaggregate amyloid, but instead appears to alter its structure.

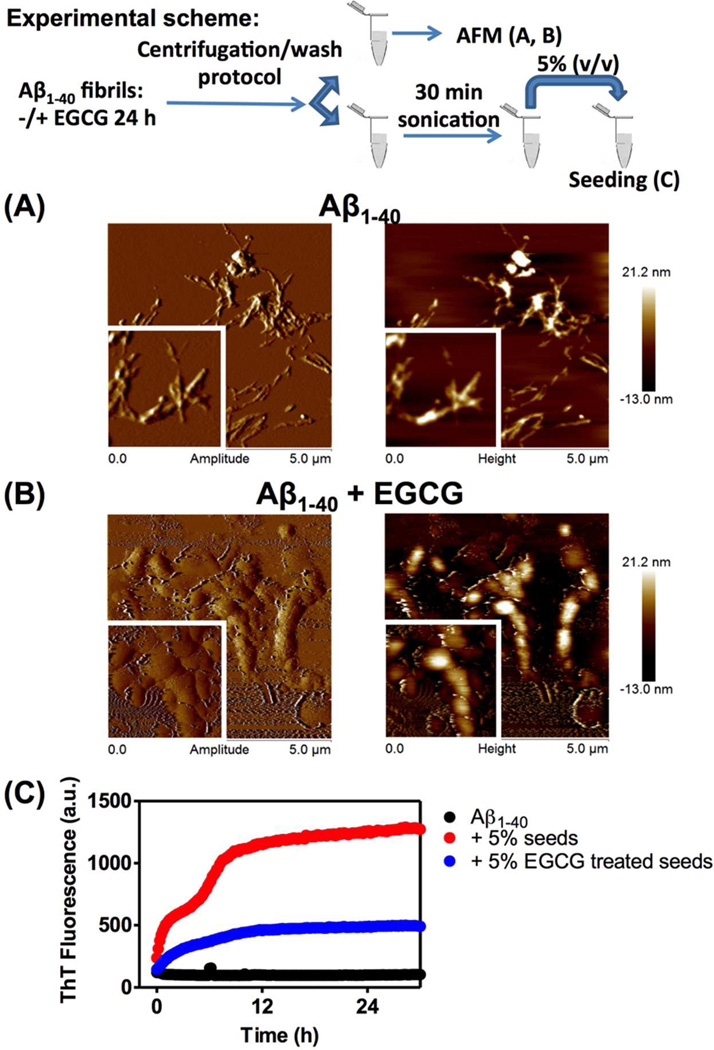

In order to determine the influence of EGCG on the structure of Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils, we characterized the aggregates morphologically by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Figure 2A, B). Compared with untreated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils (Figure 2A), the resulting product of the interaction of EGCG with Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils was amorphous aggregates (Figure 2B). The EGCG-treated Aβ1–40 aggregates were also less able to seed an Aβ1–40 aggregation reaction (Figure 2C), consistent with the Aβ1–40 amyloid fibril remodeling activity of EGCG impeding fibril growth from the ends and possibly elsewhere on the fibrils, which is the basis for seeding.

Figure 2.

Effect of EGCG on the morphology and seeding activity of Aβ1–40. Aβ1–40 (65 µg/mL) fibrils were incubated in the absence or presence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h at 25 °C. The fibrils were processed using the centrifugation/wash protocol and one aliquot was used for AFM analysis (panels A and B) while the other aliquot was sonicated for 30 min in order to produce seeds used in the seeding experiment (panel C). AFM images of Aβ1–40 fibrils incubated in the absence (A) or presence (B) of EGCG. The left images represent the amplitude image while the right images represent the height images. Inset: each image is 2 µm × 2 µm. (C) A monomeric solution of Aβ1–40 peptide (65 µg/mL) was incubated in the absence or presence of 5% seeds in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl without agitation. The seeds were produced by sonication of Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils incubated in the absence or presence of EGCG (30 µM) for 24 h at 25 °C. The samples containing ThT (20 µM) were incubated at 25 °C in 96-well plate and every 10 min the fluorescence (excitation at 440 nm, emission at 485 nm) was monitored.

The solution and the pellet of the Aβ1–40 amyloid fibril samples post-centrifugation changed appearance from transparent to brown when incubated for 24 h with EGCG, suggesting EGCG oxidation. In the presence of metals and oxygen, EGCG undergoes auto-oxidation, generating superoxide and quinones.13 The generation of superoxide further enhances EGCG oxidation. The quinones self-react intermolecularly to form polymeric species and react with the sulfhydryl (SH) or free amino (NH2) groups of proteins to make covalent conjugates16. In fact, some EGCG properties, such as human promyelocytic leukemic cell cytotoxicity is attributable to EGCG auto-oxidation17. In order to analyze the role of EGCG autoxidation in its amyloid remodeling activity, we characterized the oxidation of EGCG under the conditions used in our assays (30 µM EGCG in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 25 °C). Under these conditions, where the equilibrium amount of oxygen is in solution, EGCG was fully oxidized after a 6 h incubation period, as assessed by RP-HPLC (Figure 3A inset), with an estimated half-life of 2.7 h (Figure 3A). The half-life of EGCG was increased about 5.5 fold to 15 h when EGCG was incubated in phosphate buffer in the presence of superoxide dismutase (SOD1) (Figure 3A), as has been shown previously13. We next determined whether the auto-oxidation of EGCG played any role in the remodeling of amyloid fibrils. SOD1 addition delayed the decrease in ThT fluorescence caused by EGCG remodeling of Aβ1–40 fibrils as assessed by the centrifugation/wash protocol (Figure 3B), suggesting that oxidation of EGCG is important for amyloid remodeling.

It has been shown previously that the final product of the reaction between EGCG and mature amyloid fibrils (Aβ1–42 and α-synuclein) are aggregates that are resistant to boiling in the presence of 2% SDS6. To assess the SDS resistance of the Aβ1–40 fibrils in the time course shown in Figure 3B, an aliquot from each time point was boiled in the presence of 2% SDS and applied to cellulose acetate membrane with 0.2 µm pores, which allows the passage of soluble peptides, but traps large aggregate species (Figure 3C). The filter retardation (FR) assay membranes were stained with Ponceau, a general protein staining reagent, or nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) that reacts with quinones to form a deep blue precipitate in the presence of glycine at pH 1011. We observed that Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils were disassembled by boiling in SDS (i.e., Aβ1–40 passes through the membrane) whereas Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils incubated in the presence of EGCG became increasingly resistant to SDS over time (Figure 3C)6. These aggregates also were stained by NBT reagent, suggesting that the oxidized EGCG co-aggregated with Aβ1–40. The presence of SOD1 reduced the amount of SDS-resistant aggregates detected in the FR assay and dramatically reduced the quinone formation (Figure 3C).

Since the decrease in oxidation of EGCG was accompanied by a decrease in its amyloid remodeling activity (Figure 3), we asked if pre-oxidized EGCG could remodel the Aβ1–40 fibrils faster than fresh EGCG. We incubated 30 µM EGCG in phosphate buffer at 25 °C overnight to quantitatively oxidize EGCG (Figure 3A). A pellet of Aβ1–40 fibrils was then resuspended in this EGCG solution to give a final concentration of Aβ1–40 peptide of 65 µg/mL and ThT fluorescence was monitored using the centrifugation/wash protocol. Incubation with the pre-oxidized EGCG immediately (0 h) reduced ThT fluorescence by about 50% (Figure S2B).

It is well established that quinones can react with the SH groups from cysteine and with the free amines comprising the N-terminus or the lysine (K) side chains of proteins16. Aβ1–40 has no cysteine residues, however it has two lysines, K16 and K28 (Figure 1B in blue font). Since K28 is essential for Aβ1–40 fibril formation18, we used acetic anhydride to chemically modify any free amines present in Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils instead of mutating the lysines to alanines or acetylating the lysines prior to fibril formation. Aβ1–40 fibrils were incubated overnight in an excess of acetic anhydride in order to obtain acetylated Aβ1–40 fibrils (Figure S3). The majority of the Aβ1–40 molecules comprising the fibrils were modified by one or two acetyl groups and only a minimal amount of unmodified Aβ1–40 peptide remained after chemical acetylation according to mass spectrometry analysis (Figure S3).

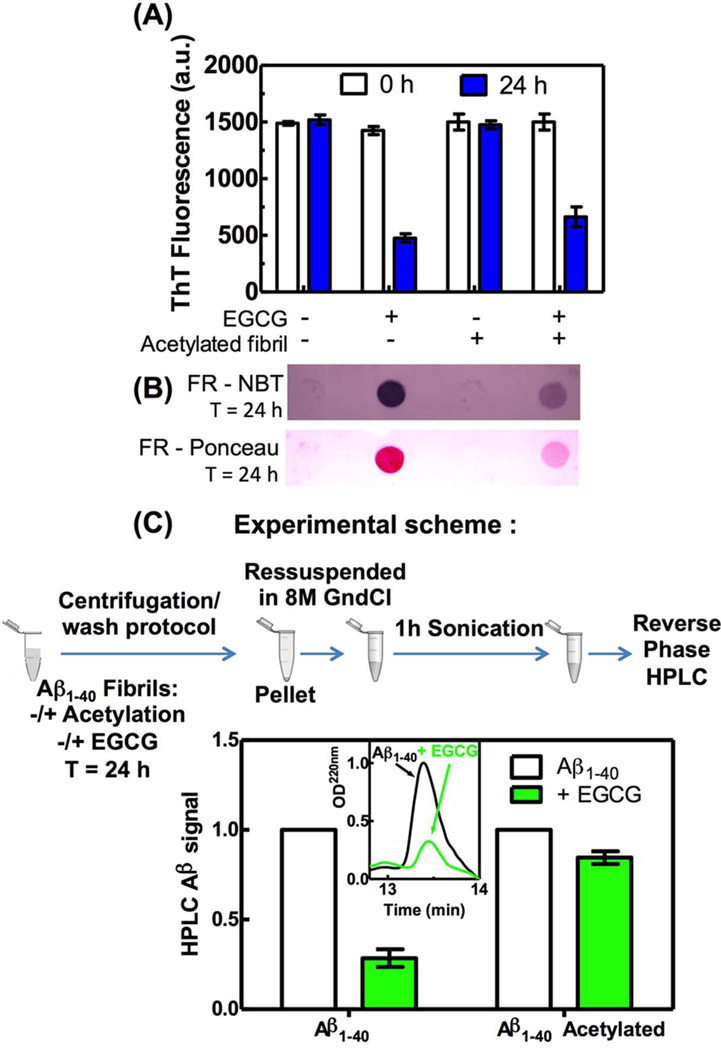

Acetylation had no discernable effect on the ability of the Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils to bind ThT (Figure 4A) or on their quaternary structure, as assessed by CD spectroscopy (not shown). When the acetylated fibrils were incubated with EGCG for 24 h, a decrease in ThT fluorescence was observed that was similar to that observed for the non-acetylated fibrils (Figure 4A). However, acetylation of the free amino groups in the Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils reduced the formation of SDS-resistant aggregates in the FR assay (Figure 4B), as covalent modification of Aβ1–40 by oxidized EGCG is not possible on acetylated amino groups. These results suggest that oxidized EGCG still binds to Aβ1–40 amyloid even in the absence of reactive free amino groups, likely at or near the hydrophobic ThT binding sites. However, in the absence of free amines, EGCG is unable to cross-link the Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils via Schiff base formation. Acetylated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils exhibit a reduced capacity to seed an Aβ1–40 aggregation reaction after EGCG amyloid remodeling (Figure S4), similar to the remodeling-associated diminished seeding exhibited by non-acetylated EGCG-treated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils (Figure 2C). As reported before6, EGCG treatment reduced the cytotoxicity of Aβ amyloid fibrils, but this reduction was independent of whether the Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils were acetylated or not (Figure S5), again suggesting that the remodeling does not require Schiff base formation.

Figure 4.

The amyloid remodeling activity of EGCG does not require free amines. Acetic anhydride was used to acetylate any free amines in the Aβ1–40 fibrils. The acetylated fibrils were incubated in the absence or presence of EGCG for 24 h and the ThT fluorescence using the centrifugation/wash protocol (A), and the FR assay stained with NBT or Ponceau (B) were monitored. Non-acetylated fibrils were used as control. (C) Acetylated and non-acetylated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils were incubated in the absence or presence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h. After the centrifugation/wash protocol, the pellets were resuspended in 8 M guanidine chloride (GndCl) and sonicated for 1 h. The samples were analyzed by RP-HPLC, monitoring the optical density at 220 nm (inset, non-acetylated fibril). The HPLC Aβ signal was calculated from the area under the peak.

In an effort to directly detect covalent adduct formation resulting from the reaction of EGCG with Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils, we incubated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils in the presence or absence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h. We then sonicated the samples for 1h to enhance the fibril fragmentation and analyzed the fragments by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). In the absence of EGCG, we detected the Aβ1–40 peptide as expected (m/z=4329, Figure S6A). However, in the presence of EGCG, we could not detect any signal that corresponded to the monomeric Aβ1–40 peptide or the monomeric Aβ1–40 + oxidized EGCG adduct (m/z ≥ 4787) (Figure S6B). We hypothesized that the product of the reaction between Aβ1–40 fibrils and EGCG is a high molecular weight cross-linked aggregate that is not volatilized upon MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis. In order to quantify the amount of Aβ1–40 that is cross-linked by EGCG treatment, we employed RP-HPLC analysis. For this purpose, we incubated non-acetylated or acetylated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils in the absence or presence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h (Figure 4C). After the centrifugation/wash protocol, the resulting pellet was treated with 8 M guanidine hydrochloride (GndCl) solution and sonicated for 1 h before analysis by RP-HPLC. Under these strongly denaturing conditions, we could detect almost 100% of the acetylated Aβ1–40 peptide comprising the acetylated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils (data not shown). In other words, the sonication for 1 h in the presence of 8 M GndCl was able to monomerize essentially all the Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils. However when the non-acetylated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils were incubated with EGCG, only 25% of the monomeric Aβ1–40 peptide was detectable by RP-HPLC (Figure 4C, green left bar and inset). This recovery increased to about 85% when acetylated Aβ1–40 amyloid fibrils were treated with EGCG (Figure 4C, green right bar). This result suggests that oxidized EGCG induces profound chemical modification of the Aβ1–40 peptide, likely by Schiff base formation, since this modification was much less pronounced when the free amines were blocked by acetylation (Figure 4C).

To further support this hypothesis, we employed an N-terminally acetylated Aβ1–40 peptide in which both lysines (K16 and K28) were mutated to arginines (peptide identity confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis (m/z= 4427, Figure S7A)). As already noted, K28 is important for Aβ1–40 amyloidogenesis, since this residue makes a salt bridge with the aspartic acid at position 23 (D23) in the cross β-sheet18. Replacing the lysines with arginines precludes the formation of a Schiff base with oxidized ECGC, but does not compromise salt bridge formation with D23 in the cross β-sheet. The AβAc1–40 K16R K28R peptide was able to aggregate into fibrils that were characterized as amyloid by fibrils by thioflavin T fluorescence, Congo red binding (Figure S7B) and by electron microscopy (Figure S7C). When AβAc1–40 K16R K28R was incubated in the presence of EGCG, we observed a reduction in thioflavin T binding (Figure S8A) and reduced seeding capacity (Figure S8C) that is very similar to that exhibited by Aβ1–40 and acetylated Aβ1–40 fibrils harboring lysine residues at positions 16 and 28 (Compare Figures 1E and 4A, and S4 with S8A and S8C, respectively). As expected, blocking the formation of a Schiff base with the oxidized EGCG prevented the formation of SDS-resistant aggregates by the ECGC-treated AβAc1–40 K16R K28R fibrils (Figure S8B). AFM images of AβAc1–40 K16R K28R fibrils incubated with 30 µM EGCG were very similar when compared with Aβ1–40 fibrils + EGCG (Compare Figure S8E with Figure 2B). Collectively, these data suggest that Schiff base formation is not required for Aβ1–40 amyloid remodeling.

There are conflicting conclusions regarding the role of Schiff base formation in EGCG-mediated remodeling of amyloid fibrils. Ramamoorthy’s group showed that EGCG forms a Schiff base with monomeric prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP248–286), disaggregating fibrils completely to small EGCG/PAP248–286 complexes by shifting the disassembly equilibrium19. In contrast, Raleigh’s group showed that EGCG remodeling of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) fibrils does not depend on free amino groups, the disulfide, or the tyrosine side chain, suggesting that conjugate formation is not required for amyloid remodeling20. We used our centrifugation/wash protocol to further investigate the interaction between EGCG and the peptide fragment of IAPP (IAPPAc8–24) used in the Raleigh study. This peptide lacks lysine and cysteine in the primary sequence and was synthesized with an acetylated N-terminus, and thus is unable to form a Schiff base with EGCG-derived quinones (Figure 5A).

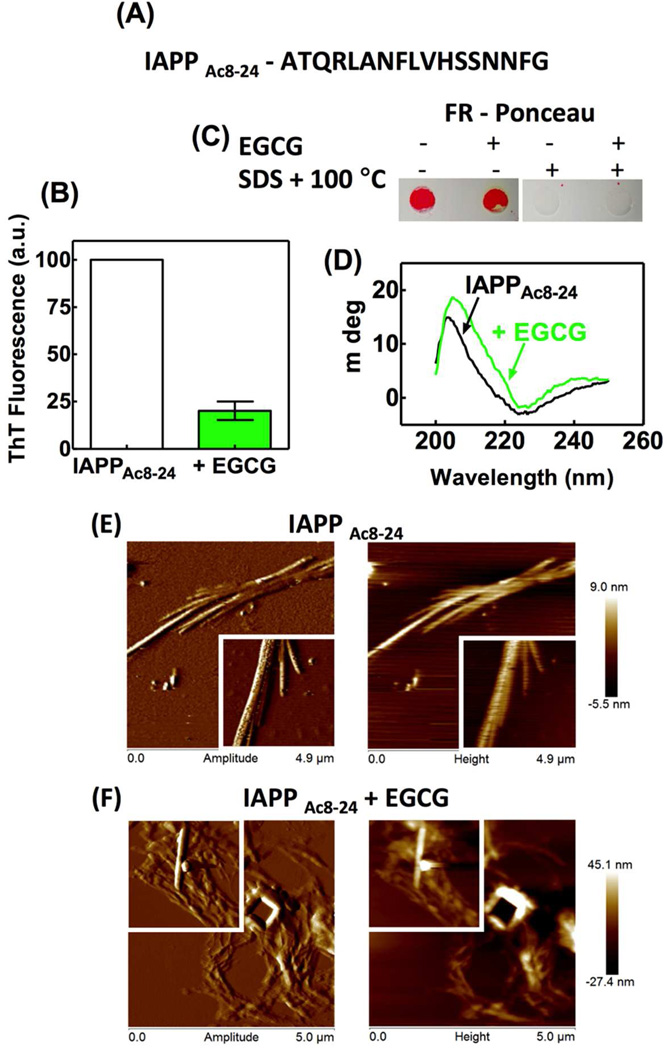

Figure 5.

The amyloid remodeling activity of EGCG on IAPP fibrils. IAPPAc8–24 (A) mature amyloid fibrils (65 mg/mL) were incubated in the absence or presence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h at 25 °C. After the centrifugation/wash protocol, the ThT fluorescence (B), CD (D) and AFM images (E and F) were recorded. Inset of panels E and F: each image is 2 µm × 2 µm. An aliquot of these samples was boiled or not in 2% SDS and then applied to FR membrane that was stained by Ponceau (C).

Aggregates of IAPPAc8–24 formed after 6 d of rotary agitation (24 rpm) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 25 °C were characterized as amyloid fibrils by ThT and Congo red binding, EM, and CD spectroscopy (Figure S9). After EGCG treatment for 24 h, the ThT fluorescence of IAPPAc8–24 fibrils, as measured using the centrifugation/wash protocol, was reduced substantially (Figure 5B), in agreement with data reported previously by Raleigh’s group. Incubation of IAPPAc8–24 amyloid with pre-oxidized EGCG produced results analogous to those observed with Aβ1–40 amyloid (data not shown). The IAPPAc8–24 peptide after 24 h of EGCG treatment was unable to form structures resistant to 2% SDS treatment upon boiling (Figure 5C) and exhibited a far-UV CD spectrum that was slightly different than that of IAPPAc8–24 peptide incubated in the absence of EGCG, consistent with amyloid fibril remodeling (Figure 5D). Deconvolution of the secondary structure presented in Figure 5D revealed that the amount of β-sheet in the IAPPAc8–24 fibrils changed from 53% to 48% upon EGCG treatment. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that some EGCG remained bound to the fibrils after the centrifugation/wash protocol, contributing to the altered far-UV CD spectrum. Analysis of the IAPPAc8–24 fibrils by AFM demonstrated that the amyloid morphology of the IAPPAc8–24 fibrils (Figure 5E) changed to a more amorphous morphology after EGCG treatment (Figure 5F); however, we still observed some intact amyloid fibrils after EGCG treatment (Figure 5F inset). We confirmed the remodeling of IAPPAc8–24 fibrils by EGCG through their reduced seeding capacity (Figure S10). Collectively, these data suggest that oxidized EGCG is able to bind to and remodel amyloid fibrils independent of Schiff base formation, but if free amines are present in the fibrils, EGCG forms Schiff bases and SDS-resistant aggregates. These data when considered in concert suggest that Schiff base formation is not required for Aβ1–40 or IAPP fragment amyloid remodeling.

Recently, Engel and colleagues showed that EGCG remodels IAPP fibrils in buffer, but has no effect at the phospholipid interface21. The authors suggested that EGCG was sequestered by phospholipids, preventing the EGCG interaction with amyloid fibrils. It was shown previously by solution-state NMR that EGCG interacts with Aβ1–40 oligomers mainly through hydrophobic interactions22. In order to probe whether hydrophobic interactions could be responsible for the remodeling activity of EGCG in the absence of Schiff base formation, we modified our centrifugation/wash protocol to include the use of a detergent in the wash step (Figure 6A). We wanted to test the hypothesis that we could recover the amyloid architecture by displacing EGCG or oxidized EGCG from fibrils by the use of a detergent.

Thus, we incubated IAPPAc8–24 fibrils in the absence or presence of EGCG for 24 h and then centrifuged the fibrils. The pellet was washed with PBS or PBS containing 0.3% Tween 20 (Figure 6A). It is important to note that we employed detergent micelles, not the DPPG bilayers used in Engel’s study21, and that these likely will bind EGCG or oxidized EGCG, but likely with a different affinity when compared to bilayers. The samples were centrifuged again and the pellet was resuspended in PBS. When the pelleted fibrils were washed in PBS containing Tween 20 instead of PBS, the effect of EGCG on ThT binding was lessened (Figure 6B) but not eliminated, suggesting at least some of the non-covalent remodeling afforded by EGCG treatment is not reversible by micelle treatment on the timescale explored. We applied these samples to the FR assay without boiling (Figure 6C, D). The Ponceau staining showed that the amount of peptide was very similar for all conditions tested (Figure 6C). However, upon NBT staining (reacts with quinones), we observed a stronger signal for the fibrils incubated with EGCG and washed with PBS when compared with the fibrils washed with PBS containing Tween 20 (Figure 6D), suggesting that the detergent was able to displace a fraction of oxidized EGCG from the fibrils. We performed the same experiment using Aβ1–40 fibrils; however, we observed no difference between the EGCG fibrils washed with PBS or PBS + detergent, because in this case EGCG is covalently attached to the aggregates (data not shown).

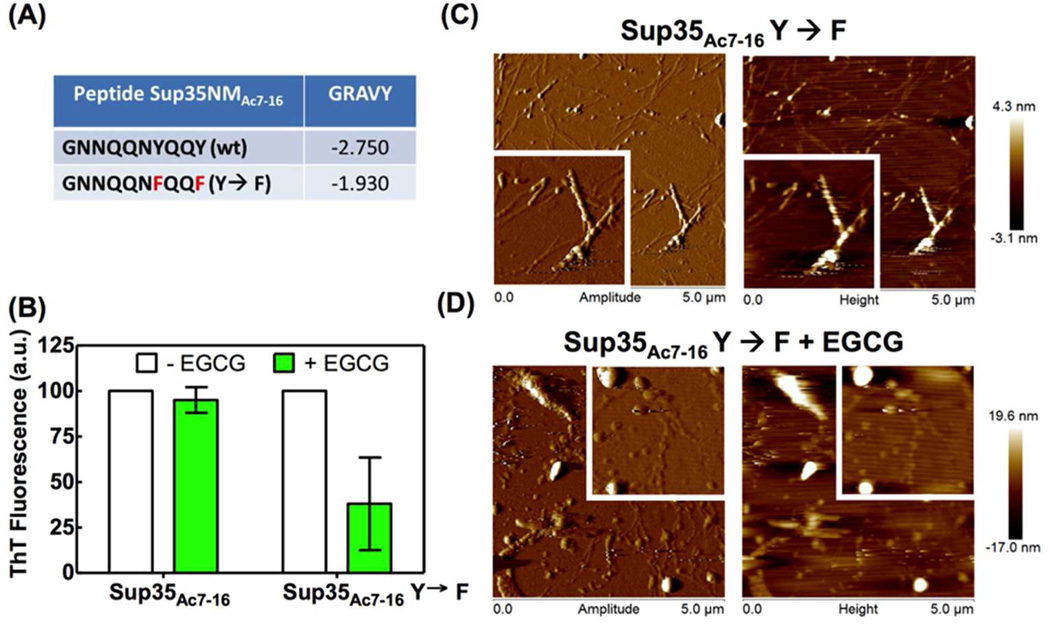

Finally, we explored EGCG amyloid remodeling using more hydrophilic amyloid fibrils derived from the yeast prion Sup35NM (Figure 7A). We rotary agitated (24 rpm) an N-terminal acetylated version of the peptide GNNQQNYQQY (Sup35NMAc7–16)23 in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 6 d to produce amyloid fibrils supported by their ThT and Congo red binding and their EM morphology (Figure S11A, B). Treatment of Sup35NMAc7–16 by EGCG for 24 h had an insignificant effect on the ThT binding suggesting a lack of amyloid remodeling (Figure 7B, left two bars), presumably because hydrophobic EGCG binding was impaired. AFM analysis showed no obvious differences in the morphology of Sup35NMAc7–16 amyloid fibrils treated with EGCG vs. untreated fibrils (Figure S12A, B). We wanted to test the hypothesis that we could affect Sup35NMAc7–16 amyloid remodeling by EGCG treatment if we made the peptide and the corresponding amyloid fibril more hydrophobic by mutation. To increase the hydrophobicity of the Sup35NMAc7–16 peptide, we replaced the two tyrosines (Y) residues with phenylalanines (F), changing the Grand Average of Hydropathicity index (GRAVY) of Sup35NMAc7–16 peptide from −2.75 to −1.93 (Figure 7A). When these fibrils (Figure S11C, D) were incubated with EGCG for 24 h, we observed a decrease in the ThT fluorescence similar to that observed previously for Aβ1–40 and IAPPAc8–24 amyloid fibrils (cf. the rightmost two bars of the Figure 7B with Figures 4A and 5B). Moreover, we observed morphological changes in the Sup35NMAc7–16 double Phe mutant treated with EGCG when compared with the untreated fibrils (Figure 7C, D). The EGCG-treated samples were a heterogeneous mix of amorphous aggregates (compare the height scale in the right of the Figures 7C and 7D) and intact amyloid fibrils (Figure 7D). Hydrophobic binding site engagement in the amyloid fibrils studied herein by EGCG undergoing oxidation appears to be sufficient for amyloid remodeling. It is worth exploring with future experiments the hypothesis that the oxidation of EGCG bound to amyloid fibrils or the further oxidation of partially oxidized EGCG bound to an amyloid fibril is what provides the free energy to conformationally remodel amyloid fibrils.

Figure 7.

EGCG is incapable of remodeling Sup35NMAc7–16 amyloid fibrils. (A) Primary sequence of the peptides comprising Sup35NMAc7–16 (wt) and Sup35NMAc7–16 Y→F amyloid fibrils as well as the Grand Average of Hydropathicity index (GRAVY) of these peptides. (B) Sup35NMAc7–16 or Sup35NMAc7–16 Y→F mature amyloid fibrils (65 µg/mL) were incubated in the absence or presence of 30 µM EGCG for 24 h at 25 °C. After the centrifugation/wash protocol, the ThT fluorescence was recorded. (C and D) AFM images of Sup35NMAc7–16 Y→F mature amyloid fibrils incubated in the absence (C) or presence (D) of EGCG. Inset: each image is 2 µm × 2 µm.

CONCLUSIONS

The data presented herein, and previously by the Raleigh Laboratory, seem to demonstrate that hydrophobic binding site engagement in the amyloid fibril by EGCG or, more likely, its oxidized products appears to be sufficient for the majority of EGCG amyloid remodeling observed in the case of the Aβ1–40, IAPP8–24, or Phe-Phe-Sup35NM7–16 amyloid fibrils studied herein. When free amines or thiols are proximal to the EGCG hydrophobic binding sites, the EGCG-based quinones are then capable of covalently modifying the amyloidogenic proteins through Schiff base formation or the like. Covalent modification of amyloid fibrils by EGCG can cross-link them preventing the fragmentation or dissociation that appears to generate the toxic oligomeric species critical for proteotoxicity24–26. We hypothesize that aberrant post-translational modifications mediated by EGCG treatment appear to occur collaterally with the hydrophobic remodeling process that seems to be the main driver for EGCG amyloid remodeling. The primary hydrophobic binding mechanism described here for amyloid remodeling by EGCG and, more likely, its oxidation products may also explain EGCG’s ability to prevent the fibrillar aggregation of monomeric amyloidogenic proteins, perhaps by binding to and making oligomeric seeds less kinetically competent4,19. How EGCG oxidation drives remodeling by the hydrophobic remodeling process merits further investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Colleen Fearns for critical reading of and assistance with the preparation of this publication. We thank Dr. J. A. Tainer for providing SOD1. We also thank Dr. E. Powers for helpful suggestions and M. Saure and Dr. A. Baranczak for help with the synthesis of the AβAc1–40 K16R K28R peptide. This work was generously supported by the NIH (NS050636). F.L.P was partially supported by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil) postdoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Additional figures S1 to S12. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Ann. Rev.Biochem. 2006;75:333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulawa CE, Connelly S, Devit M, Wang L, Weigel C, Fleming JA, Packman J, Powers ET, Wiseman RL, Foss TR, Wilson IA, Kelly JW, Labaudiniere R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:9629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121005109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palladini G, Merlini G. Haematologica. 2009;94:1044. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.008912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrnhoefer DE, Duennwald M, Markovic P, Wacker JL, Engemann S, Roark M, Legleiter J, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Lindquist S, Muchowski PJ, Wanker EE. Hum.Mol.Genet. 2006;15:2743. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrnhoefer DE, Bieschke J, Boeddrich A, Herbst M, Masino L, Lurz R, Engemann S, Pastore A, Wanker EE. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:558. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, Ehrnhoefer DE, Wobst H, Neugebauer K, Wanker EE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du D, Murray AN, Cohen E, Kim HE, Simkovsky R, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1607. doi: 10.1021/bi1013744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serio TR, Cashikar AG, Moslehi JJ, Kowal AS, Lindquist SL. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:649. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parge HE, Hallewell RA, Tainer JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:6109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paoletti F, Mocali A. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:209. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86110-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paz MA, Fluckiger R, Boak A, Kagan HM, Gallop PM. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohm G, Muhr R, Jaenicke R. Protein engineering. 1992;5:191. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sang S, Lee MJ, Hou Z, Ho CT, Yang CS. J. Agric.Food Chem. 2005;53:9478. doi: 10.1021/jf0519055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray AN, Solomon JP, Wang YJ, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Protein Sci. 2010;19:836. doi: 10.1002/pro.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki Y, Brender JR, Hartman K, Ramamoorthy A, Marsh EN. Biochemistry. 2012;51:8154. doi: 10.1021/bi3012548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii T, Mori T, Tanaka T, Mizuno D, Yamaji R, Kumazawa S, Nakayama T, Akagawa M. Free Rad.Biol.Med. 2008;45:1384. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbling L, Weiss RM, Teufelhofer O, Uhl M, Knasmueller S, Schulte-Hermann R, Berger W, Micksche M. FASEB J. 2005;19:807. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2915fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams AD, Shivaprasad S, Wetzel R. J.Mol.Biol. 2006;357:1283. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popovych N, Brender JR, Soong R, Vivekanandan S, Hartman K, Basrur V, Macdonald PM, Ramamoorthy A. J Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:3650. doi: 10.1021/jp2121577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao P, Raleigh DP. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2670. doi: 10.1021/bi2015162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engel MF, vandenAkker CC, Schleeger M, Velikov KP, Koenderink GH, Bonn M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14781. doi: 10.1021/ja3031664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez del Amo JM, Fink U, Dasari M, Grelle G, Wanker EE, Bieschke J, Reif B. J.Mol. Biol. 2012;421:517. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurer-Stroh S, Debulpaep M, Kuemmerer N, Lopez de la Paz M, Martins IC, Reumers J, Morris KL, Copland A, Serpell L, Serrano L, Schymkowitz JW, Rousseau F. Nature Meth. 2010;7:237. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azevedo EP, Guimaraes-Costa AB, Torezani GS, Braga CA, Palhano FL, Kelly JW, Saraiva EM, Foguel D. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:37206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.369942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carulla N, Caddy GL, Hall DR, Zurdo J, Gairi M, Feliz M, Giralt E, Robinson CV, Dobson CM. Nature. 2005;436:554. doi: 10.1038/nature03986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue WF, Hellewell AL, Gosal WS, Homans SW, Hewitt EW, Radford SE. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.